RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

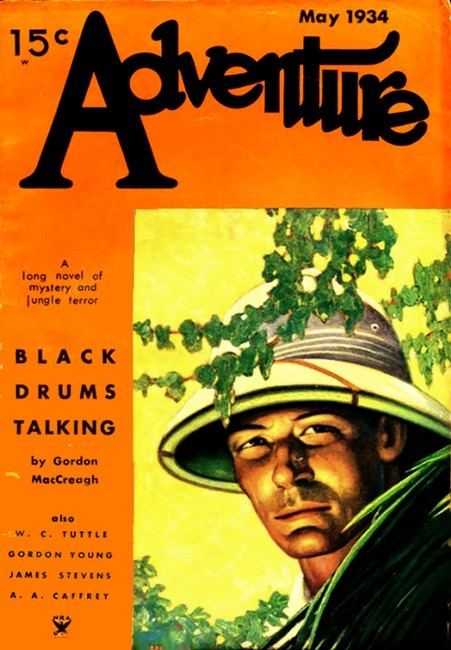

Adventure, March 1934, with "Black Drums Talking"

KINGI BWANA'S safari wound like a monstrous snake through low, rolling hills of parched brown grass and dusty mimosa scrub—like a black snake with a swift, olive-drab head. Over a low rise came King, tall, khaki-clad, tireless, his face tan as his ragged shirt, his quick gray eyes scouting ahead from under his shapeless double terai-hat. At his heels trotted, like a dog—or rather like a well trained monkey—his wizened little Hottentot whose name was longer than all his shrunken body. Kaff'enk wa n'dhlovo, abbreviated even by his own tribe, who loved staccato, monosyllabic stanzas of names, to Kaffa.

Behind them in an undulating line hurried the Shenzie porters under light loads. And last of all a resplendent figure of a black man all decked out in leopardskin moocha and monkeyhair garters at knee and elbow. His great, sword-bladed spear and his nodding black ostrich plume showed him to be an elmoran of the Masai, a single-handed slayer of lions—and of men.

From time to time the Masai would utter a gruff shout of—

"Bado, m'panze, bado!"

Which was quite unnecessary, since the porters were keeping up splendidly with King's fast lead.

Anybody could see that the safari was hurrying on the home trek; and anybody who knew Africa could see why.

Brilliant clouds, as white and as hard edged as if cut out of paper, were piling up on the horizon. Within very few days the clouds would drift up to spread over the sky, and their clear cotton white would turn to gray, from gray to threatening purple-black. Then would come the rain. People who know Africa try to avoid being caught out on trek by the rainy season.

The sun, that had been doing its brazen damnedest, poised in the exact zenith throughout the whole day as tropical suns seem to have the power to do, began to drop. And having so decided, it fell as fast as a hot rivet, dull red in the dust haze.

King, squinting through narrow eyelids to right and left, pointed to one side with his rifle. The big Masai at the far end of the line barked orders. The black line of Shenzies swung over toward the thorn patch that King had indicated.

King and the Hottentot, without looking back, strode on and were quickly lost to view over the next low hill.

The Masai expertly marked out a rough circle with his steel-spiked spear butt where the labor of thorn bush clearing and piling up would be least. Under his growled directions a boma quickly began to grow. This was bad country.

The Shenzies chanted mournfully as they dragged the spiny, stunted mimosa trees to form a tangled wall. This was to be another dry camp. Water would be handed out by the gourd measure, just sufficient to every man's need. But African safari porters grumble when they can not be appallingly wasteful of everything, even of the turbid, befouled water of the ending dry season's water-holes. So with all armies on march.

There was no water-hole. King was not trekking a standard route, zigzagging from one hole to the next in easy stages. He was making a bee-line across country, and he camped wherever the nights caught him.

Presently the sound of a far shot drifted in on the still air; and quickly after it another.

"Hau!" grunted the Masai. "There will be meat. Two bucks. In this country they will be kongoni Let four men go, and swiftly."

When the four returned with King and the Hottentot—and sure enough with two kongoni antelopes—the swift darkness was falling like a blanket. Within the boma, cooking fires smoked and stank under the profuse grease drip. The porters gorged themselves with meat, recklessly wasteful. They forgot about the water shortage and were happy.

Stars blazed overhead, but from the horizon line came low rumbles of thunder. The rain gods growling in their bellies, working up their rage for the fury of the monsoon, said the natives. Deep, moaning rumbles sounded nearby, awesomely close, yet impossible to locate with exactness. The windless air was filled with guttural sound. Somewhere out in the dark reverberated a series of vibrating roars which coughed away to silence.

"Better get the doorway thorns dragged in, Barounggo," said King. "Game was scarce today. They'll be hungry."

"It is done, bwana," boomed the voice of the Masai.

KING lay back with his hands folded under his head. The hard angles of his

face were lighted in red outline by the glow from his pipe. Another far

rumble throbbed across the night. King raised himself on his elbow to

listen.

"What man among you can perhaps read that drum talk?" he asked.

The chattering of the porters ceased. They remained dumb—which is characteristic of African porters when speech is required. Fitfully the sound eddied and faded and surged in again.

"It will be a ngoma—a dance at some village," hazarded the Masai.

But the Hottentot, crouched like a blanketed gnome over the fire at King's feet, screwed up his face and clucked derisively.

"We passed no shambas by the way," he argued. "Nor, by the movements of the scattered game, was any village in that direction. Who then would dance in this empty country, unless it be the devils of the dust?"

King nodded toward him.

"Wisely spoken, apeling. It is no dance, but a talk. Can you of your experience read that talk?"

The Hottentot gathered his blanket closer around his shoulders.

"Nay, bwana. It is a talk that I do not know. But the skin within my belly is cold, by which sign I know that it is an evil talk."

The Masai's figure loomed immensely naked beyond the fire. His voice rumbled like a lion's.

"Evil walks always in the outer dark. But what is that to us? We are men; we are in boma; we have weapons. It is enough."

King knew that the Shenzie porters, huddled in the farther dimness, listened wide-eyed to every word; he knew, too, that panic came to porters more easily even than hunger. He nodded this time towards the Masai.

"Wisely spoken, warrior," he said. "In boma and armed. Let the outer evil walk where it will. It is no affair of ours."

Yet in Africa, where evil things are many, some things can force themselves most unexpectedly upon the affairs of people comfortably secure in a well constructed thorn boma.

With the suddenness of a rising sky rocket a scream cut into the normal noises of the night. Long drawn and wailing, it quavered and faded and rose again to a high shriek.

The Shenzie porters cowered.

"Aie! Awowe!" they moaned. "It is a bush devil that calls one to his death. Let the fires be fed and let no man venture forth."

But the little Hottentot, despite the coldness of his internal skin, was coolly alert.

"A fool," he said. "A fool who tells the lions where he is. Yet the trouble of a fool is none the less trouble." Already he was applying a match to the camp lantern.

King was on his feet, feeling in the chamber of his rifle to assure himself that the load which he knew to be there was intact.

"Quick, Barounggo! Six men with spears. Both lanterns, Kaffa. And you take charge of the boma. Let nothing enter. Haul clear the doorway there. Each man armed? Come along."

Outside the boma the fires from within made a tangled tracery of shadows through the thorn branches; but within a few feet these merged into the darkness. Soon the party was swallowed up in the outer dark of the African night where there lurked bush devils and other things.

Certainly other things. Yellow-green spots of light, always in pairs, looked at them with the unwinking intensity of night creatures. Given time an opportunity for observation, an experienced hunter might attempt the supremely difficult feat of judging distances in the dark and then, from the space between the eyes, guessing whether the owners might be jackal or hyena or lion.

But there was no time for any such calculation now. No chance for anything but to rush straight ahead, making as much display of the lanterns and as much noise as possible, hoping that the creatures that stared so steadily might not be too hungry.

THE six conscripted Shenzies crowded on King's very heels, stepping upon his

boots till he cursed them fiercely over his shoulder. Behind them, as always,

came their herder, the Masai—which was the only reason why all the six

had not shrunk back into the boma the moment that their leader had passed

beyond the doorway. But they made up for their reluctance by the volume and

quality of their yells.

Before the onrushing hullabaloo the staring eyes blinked, then swung away and disappeared. More than likely this diversion drew the attention of prowling beasts away from the human thing that wailed its grief into the open night. The big cats hunt as much by sound and sight as by scent.

Again the shriek split the air, closer now. The rescuers, stumbling through the hot night, chilled at the note of terror. Even King, as the wild screech rose out of the blackness ahead, felt a tingle along his spine, in apprehension of he knew not what.

"That," panted the Masai, "is the voice of a man whom the devils have caught." And a little later, as the sound quavered again into the higher atmosphere, "The voice, too, of a white man."

Yet the word that was distinguishable now was a native word.

"N'gamma!" it wailed. "N'gamma!"

And, n'gamma, whatever it might mean, seemed to be the focus of its fear.

"Hello!" yelled King. "Where away? Hold tight. We're coming."

But only, "N'gamma!" screamed back at them out of the dark.

And then a shape was apparent in the lanternlight. A shadow that ran on all fours like an ape, then rose and tottered forward on its hind legs and lurched and crawled again on hands and knees.

In another second they were up to it, surrounded it. Light from both lanterns in unsteady hands showed it clear.

"Lord!" gasped King. "A white man it is!"

He lifted the groveling creature, the weight hanging on his arms.

"Steady, old man," reassured King. "You're safe now. We'll see you through."

But the man only whimpered and averted his swollen eyes from the light, clawing away with an emaciated hand. And what a sight of a live human thing it was—rag-wrapped; thorn-gashed; knees and palms cut to raw shreds by gravel, sharp chips of which were still embedded in the pulp-like flesh. Every visible surface was a blood streaked mess of caked grime and sweat.

"Lord!" King stared at the man. "What new horror of Africa is this?"

Suddenly a spasm of renewed vitality came to the sagging figure. It jerked upright.

"N'gamma!" it shrieked again, and fought to break away from the hands that held it.

The Shenzies shrank away.

"Awo!" they muttered. "Surely have the devils of the bush laid hands upon this one."

But the effort was soon spent. Panting and whimpering, the man hung in King's arms. King motioned with his head to the two sturdiest Shenzies.

"Make a chair with your joined hands," he snapped. "We must carry him back to camp. Quick."

IN the boma, the Hottentot, wise in the unexpected ways of the bush, already

had a can, one-third full of water, heating over a fire.

"Thirst is for tomorrow," he grunted. "But trouble is here tonight. See, bwana, the bandages are ready and I have taken the medicine box out of the pack."

King grunted a brief appreciation.

"It was well done. There will be a gift. Now lay out a blanket and help with the washing. Barounggo, if those Shenzies hold not the lanterns steady, beat their heads together."

The exhausted man struggled no more. He lay and moaned, now and then a tremor passed over his wasted body. As the encrusted blood and grime soaked away from the derelict's chest, a curious mark emerged and held King's eyes. A queer sort of crude design that had been smeared on with some yellowish ochre stuff: on each breast a circle with a dot in its center, and down over the abdomen a wavy line that divided at the navel and pointed away to each groin, like a crudely drawn inverted letter Y.

King raised his eyes, narrow and perplexed, to look into the round, simian orbs of the Hottentot. The little bush dweller screwed up his face and shook his head.

"I do not know this thing, bwana; yet it is in my belly that it is a mark of evil."

"And this word that he mutters?" asked King. "N'gamma? Is that known to you? Or anything like it?"

Again the Hottentot shook his head. King continued the washing and dressing of the innumerable wounds in frowning silence. When it was finally done the man was a mummy swathed in antiseptic bandage, torn trade cloth, and sticking plaster.

"If those Shenzies have left any meat, put a piece on to stew," ordered King. "Then sleep. I watch. Later I will wake you."

In the silent camp King stood on widespread legs and scowled into the night. Outside, throaty rumblings and snufflings circled the boma. Lambent lights in pairs stared at him out of the dark. Dull thunder grumbled. Fitfully the far drums talked their black secrets to one another.

"What mystery is this?" muttered King. "What hellish mystery of Africa?" And a little later, "Drum talk and a hunted man. Guess we'll know soon enough. They'll surely follow."

IN the morning the man was still alive, which was surprising enough,

considering what he had been through. The let-down after his terrific strain,

of what must have been many days of privation, was upon him. He lay and

moaned. At intervals a spasm contorted his face. Fear. Horror of something

beyond human sanity.

King shrugged.

"Well, we can go no faster than we're going. Two days ought to see us at Archer's Post, and maybe there'll be a medico there. Barounggo, two men at a time in relays for a blanket hammock. Divide loads accordingly. Bado-bado— and trek."

That day was like the preceding one. Whirling dust devils and merciless sun and thorn scrub. Like many previous days, except that the safari edged over to the westward off the straight line to pick up a water-hole somewhere along the Ol-Doinya foothills. Behind them drums still muttered to one another. King frowned into the heat haze.

The next boma was like the last. King personally saw to it that it was a particularly strong one. The drums that had been talking all across the horizon seemed to be converging upon the camp. King whistled tunelessly through his teeth and directed, that half a dozen large piles of dried thorn and debris be gathered in a circle thirty or forty yards outside the little fortress.

The darkness closed down, and, unlike the previous night, the drums seemed to have said all that they had to say and were silent. King smiled thinly. The Masai squatted over a fire that threw red highlights and ebony shadows upon his great muscles as with a small whetstone he stroked the long blade of his spear. Far away the thunder grumbled.

After a long silence King spoke.

"Have the Shenzies each man his shield and spear?"

"It is done, bwana. They will fight, for they are afraid."

At last it came. Jackals howled to one another—the demoniac low and high notes of gray-backed jackals.

"And that," said the Hottentot, "is foolish. For here are no gray-backed jackals."

"By which sign," added King, "we may know that those drum talkers have followed their man far; strangers, otherwise they would know. Douse fires within," he told Barounggo, "and send a man out to set light to those prepared piles of thorn."

But the Shenzies huddled together and chattered, clinging to one another like so many monkeys for protection. No man dared to venture out into the dark where there was a most mysterious kind of menace.

With superb disdain the Masai plucked his standing spear from the ground. Unhurriedly he stooped to pick up a brand and with a magnificent swagger stalked out and made the circuit of the stacked woodpiles. He knew that King with ready rifle covered his march. But so had the Shenzies known it. That was the difference between one man and another.

King grinned through tight lips as the bonfires blazed up. Within his own boma, shadowed by the interlaced thorn, was darkness. In the outskirts of the outer glare he could see figures flitting between the bushes.

Now a queer quirk of King's character, hard and efficient as he was in all his dealings with the difficult problem of the African in reasonless emotions, was that he hated to resort to the white man's ultimate argument of guns.

"They're just dumb fools," he maintained. "Barely descended from the trees. A swift kick in the tail or just the right kind of hokum, according as circumstance and opportunity demand. It will always bring them around grinning."

But here was no opportunity for the persuasive psychology of a stiff boot well placed to the nether loincloth. King was no sentimentalist about his theories. He knew very well that people who came as did these furtive forms in the night came for war, and he knew the persuasive psychology of the first move in a war.

One unwary figure was too slow in dodging between bushes in its advance. King snapped up his rifle and fired. The man flung up his arms and pitched into the thorn bush.

These strangers who had come from some far place behaved as no East African tribe that King knew would have. They did not yell, and gather to adjust their minds to the suddenness of it, to shout encouragement to one another, to work up the necessary rage for attack. They did yell; but with their first shout they charged in to the attack.

"Whau!" grunted the Masai. "These be good people. Shenzies, let no fool throw a silly spear. Thrust through the thorn barrier."

It was by that simple defence that the attack was broken. The horde of dark forms surged up to the boma. But stiff acacia thorns are as effective a barrier against naked savages as ever was barbed wire against khaki clad soldiers. Around the boma dark shapes pranced, howling the typical demoniac accompaniment of African fighting.

Thrown spears flicked over the thorn wall. But they were without aim. Within the enclosure was darkness. The leaping shapes were clearly outlined against the outer circle of bonfires. From the inner darkness spears licked out at them. Blood spurted, shiny as dark oil. Yells of attacking fury were interspersed with yells of sudden pain. King deftly slung his rifle over his shoulder. His Luger pistol spat viciously. Leaping shapes writhed or lay still.

IT was a strong defence. But the attackers, as the Masai had said, were good

people. A group of them snatched off their loincloths, and, stark naked in

the fire glow, wrapping their hands, they set to dragging away a section of

the thorn barrier. Half a dozen interlaced thorn bushes began to tear away in

a series of jerks under the strong tugs. One of the group started a grunting

chant as with a will they heaved together. If that section were torn clear

there would be a breach at which numbers would count. Inside, Shenzies clawed

madly to hold the barrier in place.

King shouted at them. But in their unreasoning fear his voice only added to the dark pandemonium. With arms and legs he fell upon his own men from behind, and kicked and cuffed at them indiscriminately, till they shrank away, jabbering.

"Kaffa," he ordered then, "the shotgun here. Step well back. Let it spread all it can."

The twelve-bore roared out. The bunched group beyond the thorns fell away, shrieking.

The defence—the strong boma with an outer ring of light—had been prepared with an experience that these attacking strangers, good men though they were, found to be beyond all their expectations.

"Bwana." The Masai's eyes showed white; his nostrils were twitching wide. "Bwana, they waver. A charge now with shield and spear will catch them in their fear and will slaughter many."

"So speaks Kifaru the rhinocerous who has little sense," said King. "But another weapon is given to us."

Little blazes, offspring of the bonfires, were beginning to flare among the dry bunch grass. The lesser blazes began to meet in a flickering line. The attackers looked behind them. King watched with hawk eyes.

"Kaffa, give me that shotgun."

A few charges of No. 4, sprayed wherever there seemed to be anything like an organizing group, were a devastating argument. Isolated from one another, the attackers' hot courage waned. Dark forms began to leap back over the spreading line of flames. Shrill whistles of recall sounded. Black shapes raced past, bounding high like frightened bucks, to join the others before the fire should grow too wide.

King grinned mirthlessly.

"Take note, Barounggo, that wit must be added to courage. Had these men had any, they would have gathered on the windward side of our fires instead of senselessly in the direction from which they came. Take men quickly now outside the boma and stamp out fires that creep toward us from the other side."

The soft night wind blew with persistence. In a little while the boma was a dark island with little waves of fire flowing past it on either side. Beyond was a widening sheet of flame and sullen, red, low-hanging smoke.

King peered out at the scene with critical eyes.

"I guess that's that—" he grunted—"though if they are wise they can backtrack and close in as the embers cool. Barounggo, take those Shenzies by the ears and tell them that it was well fought. To each man there will be a blanket. And swift now. Get the wounded who lie outside into our boma for whatever protection it may offer the poor devils. We have won the first fight and a breathing space of time. Up loads then, and a hard all-night trek. It seems, that it is his fate to win free—this white man whom the drums have followed so far."

AT Archer's Post life still remained in the man who had been the object of

that relentless pursuit. His mind still wavered on a borderland of some

horror that had driven it into the outer blankness.

The young medico at the post complimented King on his emergency first aid.

"He'll owe his life to your poisonous trade cloth bandages, if he pulls through. And he may—he must have had incredible stamina. I suppose you have no idea how long he was out, or where from?"

King shook his head.

"Must have been days. A long succession of ghastly days with the drums driving him on. Is he talking any?"

"Only that word, n'gamma, or whatever it is, and he mutters something about those painted symbols. 'Dedicated', he mumbles, and then he escaped."

King scowled into the far nothing.

"Dedicated, eh? Some hellish juju stuff he must have run into. Must have busted right into their secrets or they wouldn't have kept after him so hard." He strode a short turn up and down the room, thumbs hooked in his belt, head forward, frowning. A twisted smile tightened his mouth. "And I suppose I inherit a choice dose of voodoo vengeance for snatching him out of it. Well, that's Africa. Who around here knows anything about cults up north? That drum talk was new to all my people."

"Nobody knows much. North of Uasu Nyiro River is pretty well back of beyond. And I'm afraid—" the doctor shook his head soberly—"I'm very much afraid our patient will never tell us. Whatever it was has been a terrible strain on his reason. The fever is coming on him. I'm wondering whether we'd better put him in a car and rush him down to Nairobi where there'll be ice, or whether the jolting over the veldt trails will be worse for him than staying here. It's a devilish fix for a man as sick as he."

"There are many devilish things in this country," said King darkly. "If you take him down I guess I'll come along. If he ever talks I'd like to know for my own sake."

IN Nairobi a military attaché, immaculately incongruous in the hotel where

traders and white hunters congregated, waited upon King. No less a personage

than the governor desired to have speech with him.

"O-ho, so he's a somebody!" was King's instant conclusion. "What does the governor want to know?"

But the attaché knew nothing, or at all events would say nothing. Whatever was on the governor's mind, his Excellency would communicate if he saw fit.

King grinned at the official formality and went along. The governor dismissed the faultlessly dressed secretary and regarded with quizzical thoughtfulness the tall brown figure in rough shirt and riding breeches. He knew King of old, and King knew him. The attitude between the two men was one of friendly disagreement on almost every subject.

"And what trouble have you picked up now, Kingi Bwana of the wild places?" was the governor's characteristic opening.

King shook his head.

"Hanged if I know, Governor Bwana. It's a dark mystery to me."

"Honest? You don't know anything more than you reported to Archer's?"

King grinned at the implication.

"Not a thing—this time. Cross my heart. I picked the man out of the night, and nothing that he has babbled since has enlightened me."

"Hmh! Well, sit down. I'm going to ask you to take on one of these jobs that you're always refusing."

King's expression became obstinate. He disliked official assignments. His whole soul revolted from their encumbering red tape and the ponderous tedium of their reports.

"Now this is confidential, Kingi."

King nodded in silent agreement. The governor was serious.

"The man is dying. He will never enlighten us—his mind won't recover in time. If you know nothing his case will remain one of the dark mysteries of Africa—unless you can find out."

King made no sign of acquiescence. He waited to hear more.

"The man," said the governor slowly, "is a guide and safari conductor of wide experience. An ex-soldier, in Africa since the War. A first class man. He was one of a confidential mission that we sent out to discover, if possible, evidence about the constantly recurring complaints about Abyssinians raiding slaves across our borders."

"Aa-ah!" King was immediately antagonistic. "The old imperial policy. Anything that happens along the border, blame the Abyssinians for it. Somebody stands up in Parliament and clamors for indemnity."

"Yes, yes." The governor nodded amiably. "I know you think that everything we do is just another move toward the acquisition of more territory. But I'm afraid, I'm very much afraid, my dear Ethiophile, that in this case our men must have found the evidence."

"Listen, Governor Bwana." King was positive. "I've got friends among the Abyssinians; they may be black men, but they've treated me white. Let me assure you that the new Abyssinian law imposes the death penalty for slave raiding. And figure it out for yourself: no Abyssinians could ever have chased this poor devil so many days through British territory; no East African tribe could have chased him through the country of other tribes. There's only one explanation. Your mission ran into some high juju stuff. Only a secret cult gang could pass tribal borders that way."

The governor was one of those officials who had won to his position through long service in Africa, not through the fortune of blue-blood. He understood Africa and African needs—though always from the imperial viewpoint—better than King would have thought possible. He frowned thoughtfully.

"Perhaps you are right. We may be much more deeply involved than for a few black slaves. If it's juju there's hysteria with it. Tribal uprisings have started from less. But we must have information, accurate and reliable information, before we can crush the thing in its inception."

"Aa-ah." King breathed understanding. "So you offer me the sweet job of sticking my nose into whatever deviltry of African imagination it was that overtook your mission and drove this other fellow shrieking crazy through the night—to say nothing about their being a heap of territory along your Abyssinian border, and very presently it's going to rain a whole lot over all of it."

"Kingi Bwana," said the governor seriously, "we've got to follow up this trail while it is hot. You know Africa. You know how quickly the most murderous happening can be buried in native secrecy and remain a dark mystery forever. We must trace this thing to its source; and if there has been murder or treachery there must be swift retribution."

Cynicism hardened King's wide mouth.

"Yeah, retribution. Military police. Machine guns. That's the history of Africa. I don't hold with shooting up the dumb feed African just because he's been an African fool."

"My dear Kingi—" the governor spoke with the conviction of all imperial policy behind him—"British lives must be protected in our farthest borders. British prestige must be upheld. That is our undeviating principle that affects every white man in the country."

"Yeah?" King's own principle was sacrilege to imperial tradition. "I'm strong for the principle of top dog. But in my home state of North Dakota a man's prestige is exactly as good as he can hold up with his own two hands, and if he rides into somebody else's range and gets into trouble that's his personal hard luck. Who all was the rest of this secret mission that's so important to British prestige?"

The governor looked into King's stubborn face with a wintry smile.

"Just one other man," he told him slowly. "Sir Henry Ponsonby. The man you found was his orderly."

"The devil you say!" King's whole expression changed. "Ponsonby was—is too good a man to fool away his time on any wild goose chase after a slave rumor. Governor Bwana, if it was Ponsonby who went up he's quite likely to be marooned in some juju den, holding his end up with a stiff grin and packing more white man's prestige in his own two hands than a whole platoon of military police. And you can't turn the constabulary loose on a case like that. This juju stuff needs to be handled with kid gloves, else there are killings and general hell to pay. You know that."

The governor's smile was almost undignified enough to be a grin.

"Kid gloves, do you say? I have been informed, my Kingi, that your method was a stiff cowhide boot. But since even that is preferable to what you so aptly describe as general hell to pay, I shall make you a concession that will upset the whole system of our colonial government. I shall instruct the comptroller of accounts to pass your expense sheets—scribbled as they will be upon scraps of wrapping paper and what not—and to honor them without question."

King was blasphemous.

"To hell with your system of colonial government! But listen, Governor Bwana—Ponsonby owes me pretty nearly three dollars on a shooting bet. If I should go slopping around in the rain to collect I'd need letters to all outposts to requisition supplies and relay porters to relieve my own when they'd stick in the mud and die. And I'd need a game law waiver—water-holes being flooded and game scattered—to shoot whatever I could get for safari meat whenever I needed it. I'd need a double fly tent and porter tents and half a ton of quinine and tarpaulin covers and slickers and—oh, hell, a twenty-man load of dude outfit."

The governor's smile was now undisguisedly a grin.

"I knew you would need all of that and an armed escort besides. In the circumstances I think your bet is worth collecting. I have already signed a blank requisition for you upon military police stores. When do you start?"

KINGI BWANA'S safari was once again at the place where the cry of gray-backed

jackals had signaled the determined but ill-judged attempt to recapture a man

whose reason had left him, but who still might know too much of things that

white men must never know.

But this was a very different safari. Tents glistened wetly in the light of the sputtering fires. A huddle of narrow, steep-sided shelters fit only for a dog and aptly named pup tents; and a trim green one with a wide double fly under the eaves of which, raised from the ground on logs, were stacked boxes and bales. A tarpaulin covered another pile of lumpy shapes. There was no thorn boma. There were men enough to stand an all-night guard. Fifteen were askaris pure and simple, men who carried no pack loads save rifles of an outmoded military pattern which they could shoot off with a lot of noise and whose united front looked very formidable.

King would just as lief have dispensed with these noisy bravos who always caused envy and discontent among humble Shenzie beasts of burden. But since they were pressed upon him at the expense of his Majesty's imperial government, he shrugged and said to Barounggo, the safari driver—

"At least these be fifteen strong men; and when the strength of our porters fails in the clinging mud—"

The Masai placed a great hand over his mouth to cover a chuckle like the rumble of a lion and completed the thought:

"Out of our own good porters have we made not-so-bad fighting men, thou and I together, bwana. Surely then, when the more obstreperous of these not-so-good fighting men have eaten stick, can we make not-so-bad porters out of them?"

But it was a strong safari. King knew better than anyone in Africa what he was deliberately going into, and he was prepared for it. He knew that he was going into something that nobody knew. Africa at its darkest. Something that had swallowed up one white man because he came too close. Something that had driven another one crazy. And the latter had escaped from the immediate horror only because he had been a man of wide African experience, a first class man—a man perhaps as good as King himself.

There would be first the blank wall of honest ignorance: actual lack of knowledge on the part of the great dumb majority. There would be, when one finally penetrated closer to the mystery, the ox-dull stubbornness of people who knew something but lived in superstitious terror of it themselves and dared not even speak about it. With silence there would be the age-old defences of Africa against the white man—obstruction, underground intimidation, boycott on food supplies, queer sicknesses. And there would be, if one survived and persisted in trying to penetrate yet farther, Africa implacable, savage, diabolically ingenious in keeping hidden the sinister things that are African.

Soberly, and with a very hard expression, King led his safari through country that was new to him, scouting around in the neighborhood where he had picked up the crazed orderly. The caravan squelched through a sticky mud that less than a fortnight before had been the deep dust of the dry season. The procession was not now in a long snaky line, as it had come over that path, for each following man would but tread deeper into the sucking puddle left by the feet of his predecessor. Spread out like a line of skirmishers the men went, each one picking the best ground he could find.

It was the duty of the Masai, helped—for the present—by the askaris, to see that no man resorted to the simple African trick of dropping his load behind a thorn bush and slinking away out of the clammy wet to the shelter of the nearest native village.

Later on, when the safari would come into the really wild country of unfamiliar tribes—wherever that direction might turn out to be in this morass of nonexistent clues and obliterated paths—no persuasion or beating would drive a man of them beyond sight of the bwana whose white prestige protected them.

"From the direction of the sun's left side came the drum talk that pursued that man," said King. "Somewhere in that direction will be a village, and somewhere near the village a witch doctor. Perhaps I have that which will induce him to talk."

It was on the second day of the mire that the Hottentot pointed to the unmistakable signs of Africa in a donga whose steep sides they skirted. And "days" as applied to travel in this weather meant, not the twenty miles or so that King with his customary light safari covered, but a bare eight or ten. The donga, two weeks ago a dry sandy gash that twisted across the plain, was now ten feet deep with turbid water in which floated scraps of thatch and splinters of wood, the debris of a hut, and the carcass of an undernourished cow.

It happened every year. The rain came in its fury, the deluge tore away great slices of overhanging bank and with them huts, cattle byres, everything built too close; and every year Africa, callous, without thought, rebuilt in just the same feckless manner as it had always built.

IT was a big village, the usual sprawling mess of mud-and-thatch huts. The

rain had lasted just long enough to wash away the accumulated smells of

appalling African insanitation. King told the Masai to let the men run free

to indulge in a holiday of the chitter-chatter and gossip of the road that is

dear to the native heart.

In matters requiring wit rather than brawn it was the shrewd little Hottentot who served as a go-between for dealings that were not usual to white men. To him King gave an old brier pipe the bowl of which had been carefully carved with an intricate design.

"Go, little apeling," he told him, "and ferret out the witch doctor. Tell him that the Old One of Elgon cut that pattern. Perhaps this wizard is not so far but that he can read it and will exchange wisdom for a gift of a good blanket of many colored stripes."

The Hottentot returned in due course carrying the pipe wrapped in a banana leaf as an object worthy of reverence.

"It is a great magic in that pattern, Bwana. For the tagati, having seen it, was immediately well disposed. And, moreover, bwana—" the little man stood on one leg and clicked his tongue in awesome excitement—"he owns a lebasha, a finder of lost things, and he will let him turn his eyes into the darkness for you."

"A lebasha, hm? That's a hokum that I've heard of but have never yet seen. This may be interesting."

King was ruminative as he picked out a gaudy blanket from the trade goods. He numbered the ancient Wizard of Elgon among the first of the black men who had treated him white. That old pipe bowl, carved with whatever symbol it was of witch doctory, had won him entry to many things that white men never saw. This was going to be a new one.

The lebasha, he knew, was a clairvoyant, who by magical processes could be endowed with the scent of a bloodhound and could then pick up trails or trace stolen articles to the very door of the robber. What made the hokum interesting was that King knew certain unbelievable stories of such articles having been found. By all means the lebasha might prove to be worthwhile.

The magician lived in a clearing a mile away from the village. The tortuous path to it was hung with witch signs: skulls of animals; pointers; warning marks; grass curtains that nobody would dare to pass across the path. But these were now drawn aside. The symbols on the pipe bowl had opened the road for the white man.

The witch hut was surrounded by a thorn boma festooned with the usual emblems of magic—bones and snake-skins and dried embryos of unborn creatures, all the gruesome claptrap dear to African superstition. At the entrance stood an ebony figure, as stiff and as motionless as a statue carved out of the same wood and as naked as an idol except for a maze of painted designs. Only moving white eyeballs showed that the man was alive.

King looked keenly at the paint-smeared design. No leopard spots or wavy lines there. The cult that he sought was not there. But information that might lead to it perhaps would be.

King passed through the gateway. The Hottentot groveled after him. Within the hut, an enormous megaphonic voice boomed—

"Jambo, bwana m'kubwa, who has the favor of the Old One of Elgon."

King smiled a little grimly. He was too old a hand, he told himself, to be impressed by any skullduggery. Yet the performance that he now witnessed left him wondering.

The hut was illuminated only by such light as came through the low door, and by a tiny fire of cowdung on the bare mud floor that smoked acridly and hurt the eyes. A blanket-muffled figure squatted on a three-legged stool almost in the embers.

King knew the ceremonies of calling upon magicians. He stayed on one side of the fire and passed his gift through the smoke. The wizard took, but did not inspect it. He was shrewd enough to know that a man who knew so much of the proper etiquette would know enough to bring a proper gift.

A stool was in readiness on the near side of the fire. King squatted upon it.

"I come, wise one, seeking knowledge of a word and of the trail from where that word came."

"So much bwana's servant has told me, but the word he has not said. The seer into the dark is ready, the magic drink is ready. What is given to him to smell out shall be smelled."

The wizard grunted an order, and out of the farther gloom of the hut shuffled a youth. A thin, anemic looking creature with a witless look in his eyes and a nervous affliction that twitched one side of his face. The wizard raked a pot from the embers and poured from it into a gourd a liquid that stank of dead things.

King watched with cold criticism.

The boy squatted, gulped down the liquid and shivered. The wizard stroked his face with tense fingers and muttered incantations. The boy began slowly to rock on his heels. King saw that his eyes rolled upward in their sockets till only the yellowish whites were visible.

The Hottentot moaned in awe at the workings of black magic. King, coldly skeptical, commented to himself—

"Hm, a neurotic type, a narcotic drink and some sort of hypnotism."

The boy ceased his rocking motion and sat back stiffly at an impossible angle, breathing stertorously.

The wizard drew away his fingertips as if tenuous threads were attached to each. He whispered:

"He has gone into the place where the dead thoughts of men are stored. His eyes see into the darkness. Let bwana ask now what he will know."

"Ask him," said King, "whether he knows the word—N'gamma."

It was not the entranced boy at whom King looked. He watched the wizard keenly. But if the latter knew anything about the word whose significance had driven a man crazy he kept his composure with an astounding coolness. It was upon the boy that its effect was surprising.

He whimpered like a dog and cowered on all fours. He gave the exact impression that if he had a tail he would have tucked it between his legs.

"Ha!" said the magician. "He has found the word. It is a word of fear. He will smell out the trail to the place of that fear."

The boy breathed deeply; sniffed, in fact. Then suddenly he made a throaty barking noise for all the world like a dog, and scurried out of the hut.

"Come," said the magician. "We must follow fast."

THE boy ran in a queer, dead sort of way, his head lolling forward, his body

limp. King, catching up with him, noted with a distinct shock that his eyes

were still turned up in his head. Like a sleepwalker the boy ran, seeing

nothing, guided by some queer subconscious sense, avoiding obstacles and

trees by inches. At intervals he threw up his head and barked.

In a straight line the extraordinary trail ran, for some two miles, till a donga intersected the path, filled of course with rushing, turbid water. At the donga's edge the bey stopped and howled mournfully.

Still he pointed with his hand in the exact direction of his course. Then he fell down and lay gasping and twitching in a convulsion.

King knew that it was said of a lebasha that in his assumed characteristic of a hound he could not follow a trail across running water; that at a stream the magic power left him.

"It is finished," said the wizard. "He can go no farther. Yet there where he points is the true trail, bwana. That is all. In this matter I can do no more."

King walked back to his camp through the thin drizzle, his head sunk on his chest, wondering.

"And what, wise little apeling, do you make out of all that?" he asked the Hottentot.

The little man shivered.

"It is a great magic, bwana!"

That night a drum tapped rhythmically. Fitfully it throbbed into the dark. It stopped. Then repeated. Then stopped again. Then repeated once more.

"And of that what do you make?" King asked of the little man who shivered in his blanket.

"Nay, bwana, it is a drum talking," said the Hottentot. "Of it I make nothing. Only it is not the same talk that those other drums spoke." Curiously the little bush dweller, so astute in other things, when magic was in the air remained truly African, foolish, frightened, witless.

"I make of it," muttered King, "that this wizard was in so far honest that this word of fear has no significance for him.

"He is not of that dark cult. Yet, true to the brotherhood, he taps information for such as may have interest to know that a white man comes seeking. There will be trouble on that trail."

IT was a credit to King's organization of his safari that with the morning's

start only one man was missing. It was to be expected that on any hard and

unpleasant trek men would desert at an opportunity like this in a comfortable

village.

But the Masai took it as an affront upon his personal honor that even one man should have gotten away. He shouted threats and raged through the village, dragging frightened men out of their huts, shaking his great spear in their faces, and promising death and dismemberment if the fugitive were not delivered.

But to no avail.

"Let him go," said King. "Time is more valuable than one man. Give his load to an askari."

That was another source of shouting and argument. They were fighting men, screamed the askaris; they would not stand by and see one of their number reduced to the low estate of a burden carrier. It was exactly as had been foreseen.

The Masai charged in among them like a raving lion. They shrank from his fury.

"Fighting men?" he growled at them throatly. "Who among you is a fighting man? Let him stand forth and speak. Lo, I will fight him; shield to shield and spear to spear. Or, if he has a brother, let the twain stand forth. Or if a cousin or relative, let the family stand forth together against an elmoran of the Masai and let us see who has knowledge of fighting!"

Magnificent in his wide-flung challenge, tall ostrich plume and monkey-hair elbow-garters flying in the wind, the great fellow glared at them. His eyeballs rolled white; his nostrils twitched; the white scars of a hundred battles showed upon his chest and arms.

Of all fifteen askaris, no man, no family, showed any eagerness to put their claims to so heroic a test.

"So?" snorted the blood-hungry one. "Then we can talk. Thou, loud mouthed one." He took the selected man by the throat and shook him. "Thine is the burden today. Tomorrow it falls to the lot of the next loudest."

King affected not to notice all this.

"Up, up!" he called. "Up loads and away! What is this bickering? Time passes and the way is long before us. Up and trek."

He strode ahead. He knew that the safari would follow. A boy showed him the ford across the donga. He followed down on the other side to a point opposite to where the lebasha had fallen to the ground after his weird performance. From there he set a compass course.

"Since no other trail is known to us," he said to the Hottentot, "this at least is a direction."

So in that direction he led the way. The safari strung out behind him, picking the best ground available.

Hardly a mile had they progressed when King stopped suddenly. A clucking noise of dismay escaped from the Hottentot. What lay on the trail was no sight for panicky porters. King threw up his hand and shouted back:

"Here is quicksand. Let the men make a circle to the right—a wide circle. Let no man approach this bad ground. Barounggo, come here and see."

The safari swung away in a detour. The Masai splashed up through the puddles, wondering what need his master had to show him a quicksand in a country where there were thousands of quicksands.

"Not a quicksand," said King. "But we've found your lost man."

The Masai looked and started. Instinctively he lowered his spear and crouched ready to meet an attack. But there was no hostile force in sight, no lurking figures behind bushes. Only a man, the porter who had been missing that morning. He lay face up in the thin rain, naked, his arms stretched out as if crucified on the sticky ground.

In dry weather the hyenas would have nosed him out before dawn. The steady rain flattened the scent. The body was therefore intact and the yellow clay design stood clear against the sodden black skin. A crude leopard spot on each breast and down the belly a line that divided to point to each thigh.

King's voice was hard.

"This is no thing for the eyes of the Shenzies," he said. "But you two, who have made many safaris with me, my right hand and my left, what counsel have you to offer in this matter?"

He wanted to know right then and there whether superstitious terrors of black magic were undermining the courage of his henchmen, without whose loyal support he might as well turn back from this sinister thing to which he had put his hand.

His right hand and his left. Both men's eyes shone. There were times over late camp-fires when they argued with endless acrimony as to which one was right and which left. Never could they agree, and shrewdly King never told them.

"You, apeling, who have wisdom in the ways of the bush, what say you?"

The Hottentot stood on one foot and scratched his knee with the toes of the other.

"Bwana," he rendered his well considered verdict, "this is no witchcraft here; but the doing, as we know by this mark, of fierce men from a far place. Of men moreover—" he grimaced with the preternatural wisdom of a very old chimpanzee—"of evil men who have that which they wish to hide; otherwise they would not leave a sign such as this to frighten us from the trail. And when a secret is hidden—" monkey inquisitiveness chuckled from his wizened face—"it is honor to him who has the wit to find it out."

There was no suggestion of turning back from this trail that gave its stark warning that this was a phase of Africa not to be meddled with. King ruffled his hand through the little man's woolly hair, at which he, suddenly shy, chittered away like a marmoset.

"And you, warrior?" King turned to the other.

"Nay, bwana," said the great fellow simply. "Shall strange bush pigs do this to an elmoran? Painter folk who smear designs with colors. Shall such people slay one of my Shenzies and go unscathed? Let bwana give his order, and the safari shall proceed."

King stood scowling down at the dead thing that had been laid out in his path. Perplexity furrowed two deep lines in his forehead.

"I have never heard of any leopard society this far east," he mused. "And the leopard cultists don't paint; they use steel claws. What in all black deviltry is the meaning of this mark?"

Questioning the empty air brought no light to the enigma. King shrugged.

"At least it means that that queer hypnotized creature was right, that this is exactly the direction that we want to go. Let's go."

That was the only clew. A direction, no more. But a direction given by black magic and confirmed by a dead man. King held his compass to it.

THERE followed days of dreary tramping through the slush. Progress was

wretchedly slow. Long detours had to be made to find fords across the flooded

dongas. Actual distance gained was sometimes barely a mile in a long day's

hard going.

Porters fell sick. African natives, who are capable of enduring privation and poor food under heavy loads when engaged on their own futile affairs, revel in the luxury of sickness in a white man's safari.

Patiently King dosed them—a long line of complaints every morning. Quinine and cathartics were the stock prescriptions. King made them as nauseating as a Nairobi chemist had taught him. The men engulfed them and liked them. Medicine in all the horrible and revolting brews of native quackery was their heritage and was good for them in strict ratio to the price extorted by the quack. Free medicine at the hands of a white man was a luxury, and the whole staff vied for it accordingly.

Without the dosage their susceptible minds would have magnified their vaguely imagined ills into honest cramps and gripings. Discontent, sullen conviction of persecution and general disorganization would have ensued. So King held daily clinic and fretted for the squandered time.

Villages were few and far between. This was sparsely settled country. In the villages no information was to be picked up. Here was the blank ignorance that King had expected. To the stupid Algain tribesmen the word N'gamma meant nothing. And King hardly hoped to be able to work a witch doctor again. But he persisted on his compass course. That stark warning at the beginning had been evidence that he was aiming right; and no other course, no clew, was available.

There was some small compensation. The rain, after the first fury of the monsoon burst, slackened to intermittent downpour and drizzle. The sun managed to break through now and then to warm chilled bodies; though no day passed without its good six or eight hours of wetness. Clothes, despite slickers, were never dry. Blankets were soggy. Leather goods sprouted green fungus overnight; and worse, so did the loose cereals of the food supply. Maize, rice, beans, the staples of porter diet, ran to mold—which meant fermentation; which meant stomach ache; which meant more medicine.

Conversely to human misery, all nature rejoiced. Man pays for superiority over nature by having become a creature of artificial shelters. Without them he is wretched. Denied them for too long, he sickens. But nature blooms.

The burnt bush country that had been waiting for its first drop of moisture literally burst into exuberant green. Flowers leaped out of what had been barren dust patches without a speck of leaf in sight. Even the mimosa thorn sprouted pink rosettes of bloom that scented the air—and the long thorns grew inches longer.

Birds of gaudy plumage appeared out of the long leagues of nowhere and sang their derision of the rain. Insects hatched in their myriads and nearly all of them seemed to require human food. But game was scarce. It kicked its heels all over many hundred miles of green plain and drank where it willed.

Meat therefore was infrequent. And corn was moldy. And through all that misery nearly two score of African males had to be pushed along, cajoled, coaxed, bullied, carefully herded like beasts of burden. There was potent reason why people did not travel in the rainy season; why Africa, beyond rail and auto road reach, sits down and stagnates, isolated, for six months in every year.

DOGGEDLY King pushed on. The direction was exactly eleven degrees west of

North; and by compass bearing King held to it till his reward came in meeting

with obstruction.

Native villages began to be vaguely helpless about finding fords. Food supplies were curiously unobtainable. There was no corn; there had been a famine; the elephants had trodden down the last season's crop; the villagers were starving themselves.

The restlessness of the porters was evidence that they were being slyly urged to desert. And desert some of them did.

King smiled thinly. This was the second phase of his quest that he had expected. It was proof that, while the common herd knew nothing about the dark mystery, they had been tipped off to impede the white man. A food strike in the wilderness is a weapon a hundred time more potent than in a civilized city. Africa was sullenly defending its secrets.

Against that stolid, unwavering defence many a white man's advance has helplessly wilted and come to an end; and that, incidentally, is one of the administration's strongest reasons for the employment of native police.

Barounggo stormed into the presence of local chieflings and flung down one of two choices.

"The bwana m'kubwa, my master, requires potio for his men. So and so many baskets of this and so many of that. If they be forthcoming swiftly, perhaps we condescend to pay. Otherwise we slay and take."

Of all peoples the African is perhaps more susceptible to lordly bluff than any other. And at that it was precarious guessing for those back country chiefs to determine whether the truculent great fellow were bluffing or not. It was a strong safari; the white man who ran it looked like a hard and determined individual; and the Masai was an awe-inspiring figure. Sulky orders were given, and women brought the required potio to the camp.

THE country began to change. The open thorn scrub with its tall sentinel

acacia trees began to close in. Trees in clumps began to be frequent:

tamarisks, silk cottons, copals. The safari was beginning to come into jungle

country.

King mused upon a phenomenon of his own observation in Africa—that it was the people who lived in the jungles, rather than the open dwellers, who seemed to have evolved the more diabolic forms of dark and fantastic cults.

He was out hunting for meat when he met the first of these forest men. With the Hottentot carrying the extra gun and four pole bearers to carry in whatever he might shoot, he was skirting the jungle fringe, himself in advance, treading like a cat. A man blundered into view before he knew that strangers were near.

Seeing them, the man gave a howl, dropped his pack and bolted back into the bush path. King called after him and set the Hottentot to shouting in the half dozen or so different languages that he knew. After a frightened silence the man hesitantly called back and presently was persuaded to emerge. A stalwart, quite intelligent looking man he was, and it turned out that he understood Swahili very creditably.

There were Boranna tribes in the jungle country, he said. He himself was journeying from his uncle's father's village—he pointed with his chin—two days' journey distant to his own village; he pushed out his lips in the other direction. His pack contained fish that he had netted in a jungle pool and mealie cakes that his uncle's father's second best wife had made as a gift to his own woman who was sister to—

King cut the man short. These African family affairs were always terrifically involved. He wanted to talk about other things. Yes, said the man, there was plenty of game in the jungle; he had passed bush bok only fifteen minutes back; but why worry about bush bok? If bwana were hungry, the man would gladly trade some of his fish and mealie cakes for a brass cartridge or whatever the white man would give him. In fact, he would trade all his fish and mealie cakes; for he could catch more fish and many women could make mealie cakes, while no woman could make a brass cartridge.

Altogether an obliging and ingenuous fellow; an unspoiled son of the wild. King asked him a few more questions about the beyond, of which the man knew nothing, traded in his mealie cakes for two empty shells and sent him grinning on his way.

Strictly enjoining his four men not to monkey with that pack and particularly not to become suddenly panicky and come clamoring on his heels, King with the Hottentot went into the dim jungle path to look for bush bok.

Bush bok were not so plentiful as the man had indicated; but natives always have the most fantastically inaccurate information about game, depending upon what they think the questioner wants to know rather than upon fact.

But meat was badly needed in the camp. Fish and mealie cakes were a delicacy; but after all, one native basket would not extend to any miracle of loaves and fishes for a whole safari. King crept quietly on, a long way farther than the fifteen minutes within which bush bok tracks should have been apparent.

The farther he went, the more perplexed became his expression. A couple of times he consulted his pocket compass. Finally he stopped. A phenomenon was here that required consideration before plunging ahead. It was through a cautious observation of things that did not just click that King was still alive. The Hottentot's cunning round eyes peered up at him.

"Does the pointing machine say what my feet have been thinking?" he asked, chuckling at what he knew would be a confirmation of his own observation.

"It says, little wise imp, that this path follows parallel with the jungle edge; and I'll bet you not fifty yards from it, just to keep out of the sun in hot weather."

"Aho? So that that man, who was not a fool, walking this path, would have known that we hunted along the fringe?"

King nodded, his eyes narrow with suspicion.

"And yet he pretended to be surprised—and I have seen no other path by which he might have come."

"Nor are there any bush bok. In such a path, bwana, there may well be a man trap, or men with spears hidden."

Why, King wondered, would a native pretend not to know that a white man was hunting parallel to his own path? Very cautiously, stepping on noiseless toes, King picked his way back along that suspicious path, pausing to listen, peering into every bush tangle.

It was with relief that he came into the open where the ingenuously obliging jungle dweller had blundered into view.

Nothing had happened. No attack; not a suspicious sound. The sun had broken through a ragged hole in the clouds. Steam rose from the wet grass, warm and pleasant and cheerful.

"So-ss-ss!." The Hottentot, standing frozen on one leg, hissed the warning note of a puff adder and pointed.

The plantain leaf cover of the native pack had been removed. King might have known that four greedy native boys would plot to steal a little—just a taste—of the delicacy and then cover up their little depredation. And of course that was just what they had done. They lay now, all four of them, half hidden in the long grass, twisted into horrible contortions. Death had not come easily to them.

"Aa-ah!"

King's long exhalation of understanding was almost as sharp as the Hottentot's hiss. In three long strides he stood looking down at the four twisted bodies—and seeing nothing but the racing pictures of his own thoughts.

So this was the place. That uncanny boy with all his hokum of smelling out the trail had been right. Right to a compass degree. Somewhere in this jungle happened whatever it was that had happened to Sir Henry Ponsonby and had driven his orderly crazy. The blind search had passed through the baffling belt of blank ignorance, through the outer defence of passive obstruction, and now this was the third stage: active opposition unhampered by a single inhibition of civilization. Africa fighting with every weapon of its dark imagination to prevent the white man from finding out what the white man must not know.

"Somebody who backs this thing is very clever," muttered King. "It just happens by the grace of God that I hike and hunt better on an empty stomach."

"And what," the foresighted little Hottentot wanted to know in advance, "is to be told to the remaining porters who have not already deserted about these four who do not return?"

"Hmph! Tell them just this," said King. "They will now stick closer than bush ticks. In this jungle we find trouble in many forms."

"Truth," clucked the Hottentot. "The skin inside of my belly tells me that here live the father and mother of trouble."

YET both forebodings seemed to have been unnecessarily gloomy. King entered the jungle tense and alert against any treachery. With six askaris he took the lead. The porters, as many as were left of them, huddled behind. The Masai and the remaining askaris formed a rear guard, every man armed, watchful.

King knew the devilish ingenuity of man-traps, springy, bamboo things armed with hardwood spikes and set beside the trail, held by the most innocent looking liana vine triggers. Another kind might be set in the path, covered with leaves. Such a thing, sprung by a passerby, would rake the bowels from a man's belly, or a heavy knob would crash into his face. Another deadly trick was to tie venomous snakes beside the path. And what new devices there might be besides, nobody could guess.

Every forward step therefore was tested; every bush scrutinized. Progress was agonizingly slow. Nor was there any means of knowing which path might lead to the headquarters of the trouble or which might meander for miles to some unimportant hidden village.

"Presently," said King, "we shall hear the drums that tell of our advance; and we shall know at least the direction."

But there were no drums. Giant frogs boomed question and answer with deceptive regularity. A bittern kind of bird thrummed in a marsh with a volume worthy of a war drum. But no signals. Nor, as the party slowly progressed, were any man-traps encountered.

Of course, the obvious remedy for all this uncertainty was to waylay some jungle native, grab him and make him lead the advance. Even though he might refuse to betray the big juju village, he would know where the tribal man-traps would be located.

And it was just such a native that they caught—a tall fellow who came trotting along, singing lustily. Strangely enough, he exhibited no surprise at meeting a white man's safari creeping through the jungle. The surprise was rather on the part of the safari at the man's open-faced honesty.

Surely, he said. There was a big village barely a day's journey distant; and if the bwana were afraid of turning into the wrong path, he himself would be glad to lead the way for a small gift out of the bwana's generosity.

King remembered the cheerful ingenuousness of that other jungle dweller who had happened along with his mealie cakes and fish. Grimly he said:

"All right. Just three paces ahead all the time; no monkey tricks."

The man actually looked hurt. But the tempers of white men are always incomprehensible to natives. This man accepted the condition as the tantrum of just another queer white man and presently he was trotting ahead, chattering along over his shoulder in African good humor.

King thought to surprise something out of him.

"What do you know about the word, n'gamma?" he asked abruptly.

But the man displayed blank ignorance.

"Nay, bwana, I am but a cultivator of yams, and from them I make beer which I sell. I am no wise man who knows strange words. But in the big village is a m'zungu monpéré He knows many strange tongues of many peoples. Without doubt he will enlighten bwana."

Well, that certainly seemed to knock the bottom out of a lot of things. A monpéré was a distortion of nothing less peaceful than mon père, handed down from the days of the early French missions. All missionaries, irrespective of race or creed, were monpérés.

A missionary was established at the big village. And it was there that King had been expecting to find the seat, the very home, of the black cult that was not afraid to lay hands upon white men. This thing was more baffling at the end of the trail than it had been at the beginning. Or was he off the trail altogether? King wondered. But then he remembered, not two hours' run behind, four men twisted into horrible shapes because they had stolen just a taste of mealie cakes and fish.

However, they all arrived at the mission station without mishap. The missionary was a Reverend Dr. Henderson, a Scotch Presbyterian. He was delighted to have a visitor and was, of course, the very soul of hospitality, as missionaries in the far outskirts of nowhere always are. He insisted that King should take up quarters in his own little bungalow. For King's servants he found room in his compound with his own black boys; and the safari he allocated among the huts of his converts, quite a little village among themselves.

"A dry hut and a few days of recuperation after this dreadful weather will set them all up," he said.

When all that was done and everybody comfortable he perked his lean face to one side.

"Let me see, er, Mister King," he inquired. "Is it possible that I have heard of you, Kingi Bwana? Er, might it be the same?"

King nodded.

"I hope the stories haven't been all bad."

The Reverend Henderson's wide blue eyes displayed almost alarm.

"Dear me, dear me. I sincerely hope—you know, Mr. King—er, you must forgive me. But it is said, as I suppose you must know, that where trouble is brewing, there Kingi Bwana is likely to show up. Nobody would travel during this season unless there were something serious. I do hope that nothing is wrong anywhere near here. Everything has been going along so nicely."

KING postponed a discussion until the after-dinner prayers were concluded and

the houseboys had distributed themselves among their huts within the wire

fenced compound. Then over his pipe he told the missionary his story quite

frankly, and concluded:

"I figured I was absolutely hot on the trail. But now I'm hanged if I know whether I'm not away off."

The Reverend Henderson was, of course, shocked at the recital.

"Oh, I hope so," he almost pleaded. "I hope you are wrong. In fact, I am sure you must be wrong. Nothing so dreadful could have happened here. Everything has been so quiet. And as for any juju cult—" He shook his head.

"But hang it all," King insisted, "I know I've been aiming right. There's been proof enough in the murderous interference. And it couldn't be much farther. That orderly of Ponsonby's could not in any circumstances have been running and hiding for more than a week; and it's just about a week's hard going from here in good weather to where I picked him up."

"Indeed? Good heavens, how horrible! They were here, of course. It was barely a month ago. As a matter of fact, Sir Henry was going to send me a runner from Lenia to return some books. But—er, well, somehow he failed to do so."

"Aa-ah! He was at Fort Harrington and he was here—and he disappeared. Hmm! Well, leaving aside my theory about a juju—which I don't yet give up—what about slave raiding?"

"My dear Mr. King—" Dr. Henderson spread out his thin hands deprecatingly—"you know very well that most of this slave raiding is propaganda put out by certain European powers that want to embarrass Abyssinia in order to gain trade concessions. We are just a few miles south of the border here, and if there were any such horrible traffic—"

"So? Just below the border, eh?"

"Yes, Bagawaiyo, this village, is on the old caravan route; and established in British Territory, I have no doubt, for security's sake."

"Aa-ah! An old caravan route? Right handy for running off a few men now and then."

"My dear Mr. King! I should have heard some rumors. Men, of course, disappear. Some fall victims to the jungle; some just go away in the haphazard African manner; and in the borderland district the percentage is always high. But I have been here two years now and I have heard nothing that might lead to suspicion of anything so dreadful as slave traffic. Nor did my predecessor leave any such notes. Oh, let me assure you that nothing that might call for official intervention has been going on here."

King remained silently noncommittal. He liked missionaries on the whole. Skeptically tolerant, he felt that their Christian endeavors at least did no harm and he strongly agreed with their civilizing influence—though that did not mean that he agreed always with the soundness of their individual judgment. And then again, regrettably, there had been, in the history of Africa, renegade preachers who actually made use of their influence and their cloth to cover relationship with the most objectionable kind of back country traders.

King reserved his comment. The Reverend Henderson went on:

"Let me tell you what we shall do. I shall send a note over tomorrow morning to the Reverend Leroy. He knows these people much better than you or I could ever hope to."

"And the Reverend Leroy is—"

"A colored brother. From Jamaica, I believe, or Barbados. I can not altogether agree with some of his dogma, and he can not agree with some of my theories of approach to the native. An educated black man, you know, is always apt to feel a little superior. But he felt the call to minister to his own race and he is doing splendid work. Naturally he is closer to the undercurrents of native doings than any white man can be."

THE Reverend Leroy proved to be a splendid specimen of light negro, broad

shouldered and robust, with a keenly intelligent face. He was meticulously

dressed in proper clerical garb and he spoke educated English with a vaguely

elusive accent.

He smiled broadly at the idea of juju.

"Not among these Boranna tribes. These people are two-thirds Galla blood. The Galla are fighting men, almost as ferocious as that Masai of yours. They are animists. There is some minor witch doctory among them in outlying districts; though none here.

"At worst, their function is rather the interpretation of the forces of nature, predictions of rainfall, birth auguries, luck charms; a mild form of sorcery that no sensible man can object to in Africa where so many more important evils have to be combated. Juju, on the other hand, is the most debased form of idolatry. Anybody who has made a study of Africa knows that the more virile fighting people, the Zulu, the Masai, the Galla, never went in for that sort of thing."

King grasped at once what Dr. Henderson had gently hinted at. Leroy was distinctly superior; didactic, one might even say. King had to admit that he ought to have thought of all those quite patent facts himself. It was true. Juju belonged among the debased Central and West Coast peoples. The men here were an upstanding, open faced folk. He laughed and said to the Reverend Leroy:

"Well, I figured I was hot on the trail. But you know your own people."

"Not my people, Mr. King." The preacher's voice was bitter. "I do not know my own people. My parents were taken away from wherever they belonged—as slaves—by white men. I have no people."

King felt suddenly quite queerly shocked. He had known slaves; he had seen plenty of them in his own day. Savages they had been, dull creatures of no understanding, quite possibly better off in their condition than at large, exposed to the diseases and dangers of their native state. Right in his own country he had known colored men whose parents had been slaves. Humble people they were, far from the country of their origin.

That had seemed different somehow. But to meet an educated man, a man of understanding, in Africa, at home so to speak, who did not know where was his home! That was shocking. King could understand the resentment that such a man could feel against the system that had caused his condition. The preacher was talking again.

"And now his Majesty's government is all in a pother because politicians in Parliament point indignant fingers at black Abyssinia about slave raiding. Let his Majesty's government turn its eyes closer to home to look for slaves, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, for instance. You know as well as I do, Mr. King, that slave raiding today is punishable in Abyssinia by the death penalty. It is possible, despite that law, that some bold petty chief may dash across the border now and then and kidnap a prospective servant or so. And as a matter of fact that possibility must account for some of the occasional disappearances that do occur. But slave raiding on any organized scale? I assure you, Mr. King, there is no such thing in this district."

King could not help but be convinced. Yet doggedly he asked the question:

"So men do disappear, eh? And if not slaves, what did Sir Henry Ponsonby find out before he, too, disappeared?"

That question remained a dark mystery. If Leroy could throw no light on it, then it was indeed one of the hidden things of Africa that would be likely to remain hidden forever. King was impressed by the intelligence and force of the man. The Reverend Henderson, good soul, was the acme of hospitality and helpful solicitude; but he was the type of man of God who would never be able to see his flock other than as errant children. Leroy, however, knew what he was talking about.

The Masai, leaning on his spear, stood scowling after his departing figure.

"A proper man," he growled. "A whole figure of a man. What need has he to be ashamed and hide beneath a copy of white man's clothing?"

The Hottentot impishly strutted in imitation, copying the play of the big hands, the swing of the clerical coat, choking in paroxysms over an imaginary collar.

"Be silent!" ordered King. "And cut that out, ape's offspring. He is a holy man."

"Wagh!" growled the Masai. "I would like to fight that one."

Both men curiously resented the black man's conversion to white man's ways and clothing. Perhaps it was that both sensed the attitude of superiority. King, smiling skeptically, wondered, if that were the general native reaction, what might be the pros and cons of the never ending debate in religious circles in Africa about sending native missionaries to their own people.

But that was an idle and transient cogitation. The dominating thought in King's mind was that here or hereabouts Ponsonby was last seen and from here or hereabouts his orderly had escaped as a shrieking lunatic. Yet two missionaries who lived and worked here both gave the district a clean bill of health. That made a dead end to the whole trail.

King felt as completely defeated as a chess player when checkmated. Yet the muscles of his jaws, bunched as he prowled a long beat up and down the compound. He refused to condemn utterly his own judgment; he had been too careful; he had thrown all his knowledge of Africa into this blind game of chess where dead men marked the dark squares as proof of correct play. Now the whole board seemed to have been snatched from before him. Not very hopefully he turned to the Hottentot who crouched on a tree stump like a gnome on a toadstool.

"What wisdom of the lower pit have you to offer, impling?"

"This," said the grotesque one with certitude, "is an emptiness where one must buy wisdom from a great witch doctor."

"Bah! The monpéré says there is no witch doctor here."

The goblin gave vent to a sepulchral croak of negation.