RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

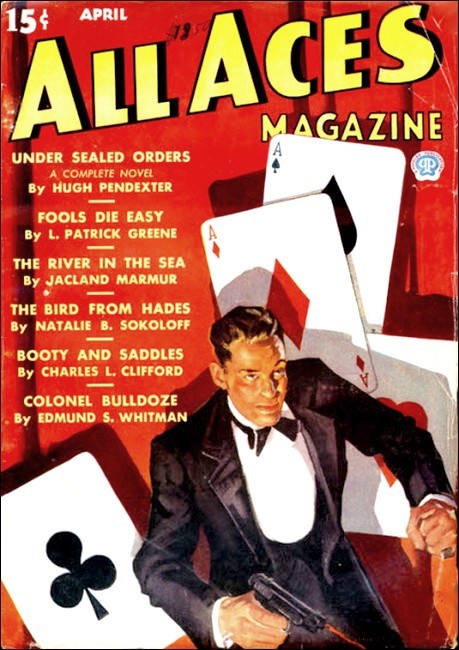

All-Aces Magazine, April 1936, with "Raiders of Abyssinia"

"BETTER hop over, Dickson," said the inspector, "and look into this. Something dashed queer up there. First Warren, not ten days ago, reported dragged right out of his house and eaten by something. And now this weird thing. Take the Moth. Flying time should not be more than four hours."

"Yessir." The corporal saluted. "Any special instructions, sir?"

"No, nothing special. Lord, I don't know what to say. This heliograph message is so incoherent. The new consul seems to be frightened silly. Babbles about black magic and what not—Er, you will be careful, of course, not to land across the border line. Those bally Abyssinians are so touchy."

"Yessir. If I can spot the break in the telephone line, I'll helio location, sir."

And so, owing to the modern magic of wings, the police corporal arrived at the consular station of Ewah before dusk; a distance that would have required three weeks of hard safari.

Consul Innis came forward with an eagerly outstretched hand that betokened his anxiety.

"I'm awf'ly glad you could come, old man. When they cut the telephone line—"

The police corporal raised one bushy eyebrow.

"Cut? How'd you know, cut?"

Innis looked up at him with intense eyes.

"I—er, I don't know. The things must have human hands."

Dickson stared down at the consul from his burly height.

"Probably just elephants, sir. White ant gets at the poles, or branches fall go that the wire sags; an' then along comes the blinkin' elephants an' barge right on through. Where is this new killing?"

Innis led the way to a gateman's lodge at the entrance to the consular compound; a wattle and adobe hut, but solid. From behind village huts naked forms peered with white, frightened eyes.

On the mud floor of the hut, sprawled as it had been left the previous night—nobody had wanted to touch it—lay the body of the gate orderly, a dark, mangled thing. Whatever it was that had killed it had the hardihood to eat of it right there without dragging away its kill.

Dickson had seen death in most of its horrible forms but the blood drained from his face at this nauseous thing. Not honestly eaten, but gnawed, slobbered over, nuzzled. It was an effort to stoop and examine it.

"Damn queer!" he straightened up. "That was never a leopard nor any of the cats. Nor no dog creature either. So then, what's left?" He drew away from the sickening thing, swallowing and grimacing. "Dashed singular. No one of the regular animals, an' so what else is there in Africa?"

A shiver shook the consul's slender frame.

"Just what—what I said in my S.O.S."

"Witchcraft? Bah! This is Christian Abyssinia, ain't it? This man was eaten by—by a—" The practical-minded corporal was at a loss to say by what strange creature.

Innis, wide-eyed, showed him the door of the hut. Its lock was the usual clumsy wooden affair, but strong and intact.

"Cat animals and dog animals," argued the consul inexorably, "can't open a lock like this. That needs—hands. And what thing with hands would—would gnaw at a dead man like that—except—" The consul whispered it in that dim hut heavy with the odor of lacerated flesh. "Some half-human creation of black magic?"

The corporal stared at him. The idea was fantastic. Yet something with at least rudimentary hands had opened that door and something with teeth like no known African carnivore had eaten at the corpse. What new monstrosity of Africa was this?

THE quick tropic dusk was beginning to throw the grotesque shadows of an

African village across the plain. Wide banana leaves spread wavering bands of

blackness over the gray dust. Squat huts made ink pools that overlapped and

merged with other blots of concealment. The first breeze of the night

coolness made its ghost talk in the trees. The corporal shook himself out of

the dusk spell to get down to practical business.

"Well, I'll get a couple o' these gapin' blacks an' get this—this mess—buried; then we can go into the layout of this place an' maybe get some reason into this mystery."

But at the corporal's first move every furtively peering figure dashed madly from him. "Uchawi!" was the terrified yelp; and the hurried scrape of heavy plank doors over mud sills and the clack of thick wooden locks indicated that the whole village was leaving the white men to whatever evil Uchawi might bring.

Uchawi. Witchcraft. The dread word that rules the lives of one full hundred per cent of black Africa!

Dickson had seen Uchawi scares before, but this one was a panic. He swore in perplexity. But he was a policeman, and certain jobs, however distasteful, had to be done. He set his teeth.

"Very well, gimme a couple your own men an' show me where; an' by hokey, I'll see that it's buried; an' buried right, too, so no filthy hyenas will dig it up."

"Yes yes," agreed the consul with a feverish anxiety. "So that no—hyenas—can dig it up."

The ex-soldier had buried men before, his own mates more than once. But never a thing like this.

There was something unmanly, insane in the terror of the wretched men whom he drove to the sickly task by lantern light.

To cover his own discomfort he demanded irritably of the men who toiled under his vigilance: "What is this witchcraft that so frightens this village?"

But at the first hint of Uchawi the African retreats behind a mask of stubborn dumbness. All that bullyragging and threats of the power of the police could get out of them was that this was the witchcraft of Those Who Devour the Dead. And further than that gruesomely suggestive title they would not—or could not—go.

"Pah!" The corporal came from that chore shivering. He swore angrily at himself. "It's this damned night chill," he growled. And to convince himself he repeated the white man's stock formula. "Dam silly nonsense! Hrrmph! Tommy-rot!"

But conviction did not come easily. And then into his perplexity broke the sudden hoarse howl of a hyena. Startlingly close.

"BLIMEY!" The exclamation broke from him. "Rummy coincidence! Dashed rum!"

Hyeneas were the filthy beasts that devoured dead things. This one must be

snuffling around the gatekeeper's lodge, where death had been so shortly

before. Dickson came warily through the gate, and suddenly he was almost upon

it.

He flashed his pocket light upon it and shooed. An immense brute it was. Right at the door it had been nosing. Instead of scampering away, it stood its ground and snarled, not ten feet away. Its wicked eyes shone green; its tremendously powerful jaws, that could crack a buffalo's leg bone, were in the full spot of the light. In the outer circle of glow the stiff hairs bristled on its low-hung neck; its spotted hide was, as all its disgusting kind, mangy from carrion diet. Quite the biggest that Dickson remembered having seen. And there it stood and showed discolored teeth, while a grating rumble came from its throat.

Corporal Dickson was brave enough. And just now he was angry. Furiously angry with himself for the jangled condition of his nerves, that had been so startled by the nearness of the brute. His gun ready to fire at instant sight, he dashed after it.

And then his heart surged up into his mouth and he jerked to a standstill. There was no hyena! Instead, in the spot where he had expected to find it, a man! Or at all events a human sort of naked form that grovelled on hands and knees in the shadows. It lurched to its feet; an uncouth, heavy-shouldered creature with prognathous, brute features. Then the thing, bending low, galloped away into the darkness, whimpering. Whining—good Lord—like a hyena!

Dickson was too shocked to follow him. He stood staring at the spot for a moment. Then he raced into the house. His first action was to cross over to the rickety table and turn up the oil lamp, where he stood breathing hard. Then he shook himself. With a long reach he scooped up decanter and glass and poured himself a stiff drink. Then he shook himself again, like a man emerging from a knockout daze.

"Crikey!" he gasped. "This thing's givin' me the willies. If I wasn't cold sober I'd swear—s'help me Gawd, I'd swear I just seen a hyena turn into a man."

"Where? How?" Innis was on his feet, his eyes blazing. He clutched at Dickson's arm. "I told you there was witchcraft in this thing!"

Dickson shook him off. The man's crazy conviction was affecting his own judgment. He sat down heavily and with the back of his pistol hand wiped the moisture from his forehead.

"Crikey!" he muttered again. "Beasts that opens doors with hands an' eat dead men! S'help me Gawd, I'm half believin' you. This is gettin' to be beyond a police job." He stared at the lamp that flickered under the weight of his hand on the table. "There's one man in these parts I'd like to talk to," he murmured. "He's well up on African deviltries. If we could only get a hold of him—"

"I know," Innis broke in eagerly. "I've heard of him. Kingi Bwana. I heard he was somewhere in Northern Province and I sent out a drum talk to try and find him as soon as this—this last horror—happened."

"Ho, you did, eh?" That patent lack of confidence in police ability to handle the case nettled the corporal. It helped to bring him back to a practical realization of his job. Methodically he produced official notebook and pencil.

"Very well, sir. Let's get this thing down to common sense. There's been two o' these—er, mysterious attacks. Here, against the British consulate. Now, the first thing to find is motive. Who might have a reason? Who lives here besides these dopey lookin' blacks? What's the lay-out o' the place?"

But there was little enlightenment in that. Ewah was no more than a caravanserai village. There were the few huts of the villagers who catered to the caravans, and that was about all. The leading citizen and trader of the place was an Afro-Arab halfbreed from Zanzibar, Moussa bin Ullah, who was astute enough to claim British citizenship and protection therefore by the consul against confiscatory Abyssinian taxation.

"A blank enough lay-out," grumbled Dickson. "You say there's no witch doctor; no devil cult? Then, what have these people? What have these so-called Christian Abyssinians on the border to do with black magic?"

"Whooo-oo-oo!" The grating howl of a hyena rose into the night to answer him, and after it shrieked a quavering, maniac chuckle.

Innis clutched his chair seat.

"Gawd!" breathed Dickson. "Who the devil ever thought to call that thing a laughing hyena?"

And, "Whroo-oo-oo-uh," it came again. Another one. And others. Howling, snarling, chuckling. Out by the graveyard.

The corporal listened tight-lipped.

"Tell me," he wanted to know, "was there any other death in the village today? I mean, anybody else planted out there?"

Innis shook his head.

"No. I'm positive. I would have known."

"Well," said Dickson with grim emphasis, "they're fightin' over meat an' nothin' else. And"—the words came through set teeth—"no hyena that lives could dig up the man I buried. We rolled heavy rocks over him."

The two men stared at each other as the uproar of a ghoul's sabbath continued in the outer dark.

DICKSON rose heavily. His rugged face twitched as he tightened his

belt.

"S'help me Gawd, I got to go an' see. Else I'll get to believin' ghosts same as you. It ain't possible; an' I got to go prove it ain't."

Innis' whole frame shook as he gripped the table edge and heaved himself up out of his chair. "I'll have to come too. I must. If it's what I—what we both think—I must come and see."

Dickson shrugged. That sort of courage was beyond his understanding. It was the urge for exact knowledge driving the student beyond the limits of his nerve. But he would be glad enough to have a companion—any sort of companion in those eerie circumstances.

The cemetery ground was pitched in the nearest convenient spot, a scant stone's throw from the village huts. The night was ink blade, the air nauseous. Impossible as Dickson felt it to be for animals to have disturbed his recent work, snarls, howls, whimperings came from the site. Whatever they were, there were several of them. If brutes, and if as big and bold as the gaunt beast that Dickson had disturbed at the gatehouse door, caution was necessary.

At a distance of a hundred feet he pressed his flashlight button. A feeble and inadequate thing it was at that range; and Innis, clinging to his left arm, disturbed the steadiness of the beam. The two men could distinguish only dark shapes that milled and fought over something. Low shapes on four feet. Eyes reflected lambent green in the ray.

"Beasts' eyes," said Dickson with an immense relief. "No ruddy ghosts there."

"Beasts without hands couldn't move your rocks." Innis refused to be diverted from his fearful theory of sorcery. And then: "Look out! My God!—They're coming!"

The dark forms, with concerted agreement, had left off their fighting and were advancing slowly, growling in their throats.

A half dozen things of that size in their own night were as deadly a danger as lions by day. Dickson fired quickly into the mass. The pack roared fury and rushed in a bunch. The flash beam wavered drunkenly in the air under Innis' clutch. Dickson shook him loose furiously and fired again.

"Run!" screamed Innis' voice from behind him. "My God! You can't stop them!" And himself he raced in mad panic for the house.

Behind him he heard more shots. Something yelled in physical pain. Innis stopped. His impulse was to rush back. But he was alone amongst gravestones in the inky blackness, and he had no sort of a weapon.

"Come on!" he screamed again and stumbled frantically on for shelter.

At his door another wave of panic met him. It yawned blackly open—they must have left it so in the anxiety of their exit. The draught from outside had blown out the light. Innis lurched over the threshold, fell, lurched to his feet again, moaning incoherent cries to Dickson. Roars, howls, a flurry of shots, piercing yells came. But no Dickson.

In an insanity of panic Innis fumbled for matches, fumbled madly—for agonized hours, it seemed. When he found them they sputtered against the wick in his trembling fingers and went out. Cursing in a frenzy, he lit more, in bunches. When he finally got the lamp alight, only bestial roars, brute snarls came from the fearful dark—and maniacal laughter.

Innis screamed for his servants. He might as well have screamed for a guardian angel with a fiery sword. Servants cowered in their huts behind safely-barricaded doors. Innis had no sort of weapon in the house; he was a student, not a hunter or a fighting man.

Cursing helplessly, shamed by his own ineffectually, he shut his door and, like his servants, who knew the practicality of black magic, he barricaded it from within.

DAYLIGHT brought a measure of sanity; and—he thanked heaven—Kingi Bwana.

Tall, sun-browned, coolly observant, his narrowed eyes squinting deceptively

in the sun, but taking in every detail as he walked forward. With him his

wizened Hottentot servant, who scurried about like a blanket-wrapped monkey

and asked questions and took notice of everything; and his Masai, immensely

naked, who leaned on a great spear and waited only to be shown something

which he must fight.

There was an enormous comfort in those three hard men of the African black lands, whose reputation had come even to a newcomer like Innis.

"Thank God!" he bubbled over. "Thank God you could come; all three of you. You'll all be needed in this frightful business."

"Yeah," said King. "I picked up a drum talk that sounded pretty frantic, and the drums said a police plane had flown over. So I made a night trek and came along. Plane still here; no policeman. More trouble, eh?"

"Worse than that. Oh, my God! I'm ashamed! But I couldn't do anything! In the night I just couldn't!"

"Hey, hey!" King laid a steadying hand on the consul's shoulder. "Take it easy, hombre. Come along into your house. Give me a drink and a wash and then get it off your chest."

In short, hysterical bursts, broken by shudders, the consul told his story. But his overwrought state gradually subsided, and he became more coherent as King listened, commenting neither one way or the other, shooting in only an abrupt question at intervals.

When it was all over King grunted.

"Has anybody been down to this cemetery place since Dickson disappeared?"

Innis shook his hanging head. "No native would dare; and I—I—"

"That's quite all right, too," said King. "I'd hate to walk into a pack of hyenas—or ghosts for that matter—at night without a gun, either. How about coming now and looking things over?"

Innis shuddered again but answered:

"Yes, very well—With you, yes."

King nodded. The man was not altogether a craven. He had been through some sort of a shocking experience. But he was getting hold of his nerve.

"Circulate about," King told his two blacks. "Talk with these people of foolish countenance and find out what you can—Come along, Innis."

In the graveyard they soon came upon the body of Corporal Dickson, or what was left of it. A sickening mess of shredded clothing and clotted blood and ragged flesh. Innis averted his head and trembled. King dropped a strong hand on his shoulder again. His own nostrils curled as he looked at the gnawed-over thing.

"All right, amigo. Steady. You couldn't have prevented it," he told the shivering consul. "Now come on. I want to see that grave."

The heavy stones that the corporal had placed as a protection were scattered, flung aside; the earth lay in heaps. That exhumed corpse had been almost wholly eaten. Its remains lay sprawled hideously.

King's eyes flashed to every little detail of the repulsive scene while he stood in silence and pondered.

"You see," quavered Innis. "That needed hands."

After a further silence King slowly nodded.

"Yes," he agreed. "That needed hands. Dickson knew well enough how to bury a man in Africa." He whistled tunelessly through his teeth. "Those Who Devour the Dead, eh? A singularly horrid conception, even for Africa; and it's beyond my guessing. Hyena teeth have been here; and yet, what are these other beastly marks? These slobbery gnawings?"

"Yes, yes; That's what I told you." Innis whispered in tremulous excitement. And then, after a moment of silence, "Mr. King, what if there are wounded men in the village today? Pistol wounds—Dickson shot something. And by daylight they must revert to human form."

King regarded him through narrow slits.

"You sound crazy to me," he said. "But come on in again and palaver this." Within the house he motioned Innis to a chair, while he himself stalked the floor, his thumbs hooked in his belt. "Now tell me, Mister Consul, what is this that you are ready to believe about black magic that kills and eats men and about which I know nothing?"

Innis shifted uneasily and refused to meet King's eyes.

"Go ahead," said King. "I've seen enough unbelievable things not to laugh."

Innis sensed an immense encouragement and sympathy.

"Well," he blurted at last, "I couldn't tell Corporal Dickson. But you—perhaps you'll understand. It's—I'm sure it's lycanthropy."

King stopped in his stride to stare at the man.

"That's the highbrow word for werewolves, isn't it? But good Lord, man, that's European. That's mediaeval superstition. And we're in Africa of today."

INNIS hitched his chair forward and leaned towards King to expound.

"Do you know that occult societies exist today—even in your own America—such as the brotherhood of Pow Doctors—who believe that not all mediaeval magic was just superstition; that some of them practice magic today? And listen again. Even you know that all Christian mediaeval Europe believed in the absolute practicality of a ritual which enabled certain adepts to transmute their bodies into the form of wolves. And you know"—he spoke with significant emphasis—"that Abyssinia was considerably under the influence of mediaeval Christianity."

In that primitive room, with its sparse, hand-made furniture and its mud floor strewn with reeds, the man's feverish sincerity sounded not nearly so wild as King might have expected. All that he could say, rather lamely, was:

"Well, but that's wolves. There aren't any wolves in Africa."

"Listen." Innis pointed a professorial finger at him. "In Europe the form of the transmutation was, very naturally, some local carnivorous animal. In Iceland, for instance, it was black bears. In Abyssinia—and these outlying borders have remained utterly mediaeval—it is—hyenas!"

A short laugh broke from King, though it was no loud snort of derision. It was just that he did not know what to say; the thing sounded so damnably plausible. His only logical objection was: "All the same, a mediaeval Christian superstition is a far cry from three material killings in an Abyssinian border village of today."

"Listen some more," Innis insisted. "The writings of the mediaeval magicians, Hermes Trismegistus, give a detailed formula and ritual—gruesomely awful, as all such black rituals are—for effecting the transmutation of a human into a beast that must then raven after the flesh of other humans. I know that copies exist in this country. Africans—of mediaeval sensibilities, or less—can subject themselves to such revolting rituals—as witness voodoo and its inexplicable performances."

King prowled the room, scowling at the floor. Then he shook his head.

"I think you're altogether wrong," he said at length. "I'm the last man to say that things beyond all sane belief don't happen in Africa. But this—I can't swallow your theory—yet. Though I'll admit I've said such a thing before and had to swallow it. But even if you should be right—the Lord knows, anything may happen in Africa—Poor old Dickson was right, too. There's still not enough motive in sight. Come, show me your village—the people, houses, everything. Let's see whether we can't dig up something, just as your devil beasts do."

So tour the village King did; but from that he gained nothing. It was a quiet and very ordinary African village. There was no witch house; no skull-and-bone-festooned shrine of necromancy; no resident sorcerer; nothing. Just a village, hot and ill-smelling in the sun.

The villagers looked furtively at the two white men. They were by no means hostile; they looked as mediaeval Christians might have done upon a pair of excommunicates. The white men's house had been marked for Uchawi.

The utter absence of any sort of a background for the abnormal happenings of after dark baffled King. Although he growled:

"I agree with Dickson. They're a mangy looking lot. But hell, I don't connect any ideas out of that. Let's go talk to this British subjects of yours."

THE man Moussa showed the Arab half of his heritage by demanding more

personal privacy for himself and family than the happy-go-lucky pure African.

His house, more pretentious than the native huts, was surrounded by a bamboo

fence. The Negro half of him was evinced by the slipshod condition of that

fence. Through its gaps, as the visitor approached the house, a woman could

be seen.

"Ha!" King stopped to stare. "Where's she from? Down coast? Yemen? She's no African."

But Innis did not know her. "I've never seen her close. Mohammedan fashion, he keeps her purda-nasheen."

Mohammedan fashion, too, Moussa bin Ullah was all hospitality. In feature he was more Negro than Arab, but his manners were the perfection of Arab hospitality. Personally he met his guests at the door.

"Subakh Allah bilkheir," he called upon Allah to give them health. He conducted them in, placed cushions for them, clapped his hands and a Negro boy brought thick, sweet coffee.

King was too immersed in the mystery of all these happenings to have any manners. Instead of the customary long preamble about trivial nothings as demanded by etiquette, he came bluntly to the point. What did Moussa know of conditions, of people, of any man, witch doctors, devil priests, who might, would or could engineer witchcraft against the British consulate?

But Moussa spread his hands deprecatingly. Who would be interested in instigating any such thing against the consul effendi? Did not all men know that the consul interfered with no man, that he exercised jurisdiction and collected a just duty only upon caravan imports into British territory? And was he not particularly Moussa's friend and protector from aggressive Abyssinian taxation? As for witchcraft—he shrugged—these borderland Abyssinians were, after all, primitive Africans. Any untoward happening was immediately set down by them as witchcraft. Why should Innis Effendi let himself be troubled?

But, persisted King, hadn't the trader heard at least the hell's chorus of the last night's darkness and the shooting?

Moussa crossed his legs and exhaled smoke. Hyenas were everywhere—may Allah curse them. As for himself, his house was far from any such disturbance. Would a good Moslem build his house near a cemetery? And particularly near a Christian one?

Well, there was no information there. Or if there was, it was not forthcoming. Unless there might be any value in the trader's veiled suggestion that some Abyssinian caravaneer might resent the customs duty, and so—but more than that Moussa would not say.

King stalked from the house. With long strides he crossed the compound, head forward, frowning, his thumbs hooked in his belt. But suddenly he stooped.

A child was playing by the gateway; a lemon-brown little boy, richly dressed in absurdly grown-up pink satin coat, tight white pants, and embroidered cap and slippers.

Inquisitively King lifted the child's chin. It had the round, owlish little face with the soft eyes and extraordinarily beautiful eyelashes of halfbreed Arab descent. King lifted its hand and looked at its finger nails.

"Ha!" he grunted then and strode on. Outside the gate he remarked. "Just what I thought. That was a white woman. Wonder where he got hold of her? No bearing on this case; but what a hell of a life!"

Innis made no comment. He was staring at a man, a thick-bodied, blanket-draped native who, unlike the rest of the unhostile villagers, scowled sullenly at them. Innis gripped King's arm.

"Look!" he stammered. "That's a new face in the village—And see his shoulder. He has a wound. Maybe a bullet?"

Quickly King looked the man over. A dull, brute-faced fellow he was; and he certainly scowled at the white men.

"Rubbish!" he said testily. "You've gone crazy with your mediaeval superstitions. Here, I'll show you in a minute that whatever his hurt is, it's no pistol wound."

But at King's approach the man sprang away and fled from him as a wild thing might, wailing and crying into the bush. King was too utterly astonished to follow until too late.

"And I've seen other new faces in the village," said Innis with dark meaning.

"Hell!" snorted King, "you'll have me crazy along with you." He frowned into the troubled distance. "The fellow's teeth!" he muttered. "Like a gorilla's. But even idiot apes don't eat dead men. Let's be sane—Now then, what is there in this hint about caravaneers having it is for the consulate as a customs collector? How would that be for a motive for sicking something onto you?"

"It might be. But caravans aren't due for two weeks. Still—some importer might have instigated a magic—might have sent a pack of beast-men on to clean out the consulate before his arrival with some prohibited goods or other. It could happen."

"Good Lord! A whole pack, you'd have it now." King growled in his throat. After a thoughtful silence:

"An instigator two weeks distant doesn't help. This thing is upon us here and now. Oh, I agree there's a physical danger aplenty. No one can laugh away three men killed and devoured by—by—" His voice trailed away in scowling perplexity. Like corporal Dickson, the night before, he was unable to say, killed and eaten by what.

He strode in silence till a thought came to him and the worry was removed from his face by a thin and very hard smile.

"Innis," he said. "Your ghost stories are getting me too. So before I go completely loco I'll tell you what I'll do. By golly, I'll lay for these ghost-beast things of yours. This very night. And I'll catch one of them—alive! I've caught wild beasts before. And we'll clear up this madness."

"That," said Innis slowly, "sounds plausible—when you speak of it—by daylight."

KING only laughed. His worry was gone; action lay before him. He went off to confer with his henchmen. Native gossip, and particularly in matters pertaining to witchcraft, came of course to them as to no white man.

Yes, new faces were in the village, they agreed. At least they did not live in the village; they had arrived recently and had taken possession of some huts that had been deserted on account of cholera a year ago; down by the dry water course that led to the sunset.

"Ha! So?" It was a weird coincidence. Callously these brute-faced strangers lived in a place of pestilence. And not only that, but in that same direction lay a heavy belt of thorn scrub in which hyenas, too, must lay up during the daylight hours. The donga, with its sandy bed, was the obvious path.

King blew sibilant discords through his teeth. Every new angle to this thing but bolstered up Innis' horrific contention of a man-beast sorcery. But—King grinned tightly—this night would show.

But a whole pack of creatures as ferocious as these—whatever they might be—could not be tackled alone. King must have the unflinching support of his black men. And that was a negotiation that called for diplomacy. He said to the two of them:

"Now the matter of this witchcraft that threatens us here. It must be fought."

He addressed himself particularly to the Masai, whose creed it was that life for a full-bodied man existed only for the purpose of combat. The big man shuffled on his feet. Not to stand by his master in a fight went sore against his manhood. But witchcraft!—

"Look!" said King. "I go into this fight to face whatever may come. Do I go alone?"

"Indeed, Bwana," the Masai's fierce face worked with emotion, "shame lies heavy upon my feet; yet it is known that white men in their wisdom are proof—or, at least, very nearly so—against magic that eats us black men up."

"Agreed," King quickly said. "Witchcraft made by a black wizard does not easily attack a white man—though we three together have seen it happen. But this, as all the village knows, is a magic out of the white men's religion. Therefore it is clear that not you, but I, must be vulnerable."

That indeed was an unanswerable logic. After a full minute of assimilation the Hottentot clucked his tongue against his palate.

"Association," said he, "with this great spear-wielder who exercises only his muscles has made me dull-witted, else would I have seen that myself."

A great grin began to spread itself over the Masai's face, though he still looked sheepish.

"My shame remains, Bwana," he said. "That I hesitated to go where Bwana went. Let me now but have opportunity to win back my manhood."

"Good!" said King. "We go then to set a trap, a pitfall in the donga path by which these witch creatures come. No man can set a trap like Kaffa. Man or devil, something will be caught this very night."

And the trap that little Kaffa then set was a trap. The simple old pitfall principle, but prepared with all the jungle lore that the Hottentot possessed. He chose a narrow spot in the donga. Stiff clay banks, scoured twenty feet deep by the torrents of a thousand rainy seasons hemmed it in. Lower down, sandy soil permitted a widening and a growth of straggly brush. At the edge of the brush the Hottentot dug his hole. The earth was carried back and scattered. A frame of thin bamboo strips was woven over the pit. Surface soil of the same surrounding kind was scattered over it. Even the little shrubs were reset in their original positions. Finally the faintly depressed animal run that meandered along the donga floor was cunningly continued as it had been.

The Hottentot stood back and surveyed his work as might an art critic. But he lifted his stub nose and sniffed the air with dissatisfaction.

"I yet smell man," said he. And with that he crept past the thin edge of his pit and went scouring down the lower brush. He returned with the body of a zoril, a skunklike creature with strong scent glands. He dissected the glands and with a stick smeared the unpleasant musk about the immediate bushes. At least he was satisfied.

"That," he pronounced, "is a trap."

"A good trap," said King. "Nothing less than human intelligence will avoid that; it's beyond any beast cunning."

"Perhaps," Innis interposed his obsession, "a combination of both—man-beast might—"

"Anything might be," said King. "But at all events tonight we'll know."

DUSK crawled in on horridly laggard minutes. Even King felt a tension grow

upon him and swore at himself for a fool. With the dying of the dusty red sun

a thin slice of new moon showed in the sky.

"The wizard's moon of black magic," Innis croaked out of his occult lore.

King swore at him also for a fool.

"And I'll prove it to you before this night is up," he growled. "Or at any rate we'll settle something—one impossible way or the other. And so I'm going out with my boys and watch. Whatever falls into our trap mustn't be given a chance to get out."

"No—no indeed!—or be helped out by other hands." Innis harped on his fixation. He rose from his seat, closed his eyes tight and shivered. "I too, I must come with you."

King understood what the police corporal had been unable to do—the student's urge for exact knowledge. He did not argue.

"Better put on all the heavy clothing you have. Woolen shirts, sweaters—Not because you shivered. Look at me." He himself bulged under his khaki shooting coat. "Padding." He explained. "A tip I learned from a bear hunter. I'm alive now because of it. And what have you that would do for a weapon? A good knife, machete or something? A gun won't be so good if it should come to a mixup in the dark."

On the upper lip of the donga the little party found a place. Hidden in a brush patch they could look down—or rather, they could listen down to the place of the trap. The thin moon showed only shadows darker than the other shadows, and below them, a wide trench of solid black.

Waiting was as waiting always is—tense and full of tiny noises. Tight with the pulsing vibrations of a thin wire. King was alertly silent. The others he could not see, ensconced as they were in whatever little openings the brush afforded. But he could hear to one side of him a soft whsh! whsh! It was the Masai stroking the long blade of his spear with a little stone that he always carried in his knee garter of monkey hair. Then the grunted whisper of the Hottentot asking for the stone. There was comfort in those noises.

Then the abnormal ears of the Hottentot picked up something.

"Things move below, Bwana."

Their own voices would not carry down into the gully nearly as well as sounds would come up. King could hear them now. The quiet pad of feet, too faint to guess whether of men or beasts. Right up to the edge of the brash patch they sounded. Now was the imminent crisis of the whole venture. Another step and something would crash through the artificial floor.

But there at the brush edge was a pause. Faint shufflings, cautious whisperings—or was it the swishing of leaves?

Innis' hand groped out and found King. His whisper was an odd mixture of elation and awe.

"Nothing less than human intelligence, you said, would suspect."

King only gripped the arm that had found him till Innis' choked remonstrance gave him a realization of his nervous strain.

Then up from below came the whimpering, maniac giggle of a hyena!

King's pent breath drew in yet another gasp. Whatever was down there could not be! Something must fall into that perfect trap!

"Listen!" came Innis' whisper. "They are going back!"

Shufflings and scrabblings sounded. Retreating. But not far. Stones slipped. Earth fell in tiny cascades.

"They're climbing up!" said King grimly. "And on this side!"

DOWN the donga, where the bank was not so steep, scuffles and little

landslides were plainly audible. The things—as though they understood fully

that they had been expected—seemed now to be careless about concealment. The

last earth clod rattled from the ravine lip. Then a long, black silence.

"If you can find a tree," King called to Innis. "Get up it, fast!" Himself, he rose from his prone position and drew his heavy hunting knife.

"They come, Bwana!" croaked the voice of the Hottentot. And the immediate crashing in the bushes told the rush of heavy bodies.

For the next demoniac five minutes King knew only that he fought with blurred shapes. The blackness was just pale enough to show that shadows detached themselves from the bush shadows and howled as they rushed in. He heard the shout of the Masai, a high pitched squeal from Innis, and then a low charging form hurtled against his legs and he went down. Something clamped viciously upon his arm and worried. Thank God it was well padded, but it was his knife arm.

King rolled desperately. His legs found and twined themselves half round a heavy body, half round a bush. He fought to change that entanglement; with a scissors grip he might have cracked ribs. The straining grunts from his own throat equalled the muffled brute growls of the thing that held his arm and heaved at it in great twisting tugs. His left hand found a fistful of skin and coarse hair. He twisted at it, rather ineffectually punched at it. In their joint plungings the body fell over his face. His nostrils were filled with a feral stench. Furiously he heaved his knife arm up and down against the grip that numbed it; this way and that, hoping somehow, anyhow, to stab into flesh.

Either he succeeded—he could not tell—or somebody else in the black mêlée connected with something. For the thing yelled and let go. King lurched to his feet.

"Innis!" he shouted. "Innis! Where are you?"

But he could not hear himself. He was in the indescribable uproar of an enormous dog fight with an undercurrent of the confused shouts of men. Then another shadow hurled itself at him; and down he went again, clawing and clutching at anything, everything, in the first desperate need to keep teeth from his throat. He had just succeeded—he thought—when the ground fell away from beneath him. He felt himself rolling, the beast with him. In a whirling scramble they went down together, gashed by stones, impeded momentarily by bushes that in the next instant tore loose, accompanied by rubble; till with a grunting thud they reached the pit blackness of the donga bottom.

Here King could not distinguish even shapes, only something that growled and fought with him. Grimly he had held on to his hunting knife. He stabbed out into the dark, and stabbed again. Heavy resistance gave him a spasm of triumph. But that was only sticky clay. Furiously he stabbed again, and yet again. Suddenly the thing yelled piercingly and rolled clear. King staggered to his feet, widespread, knife held forward for another attack. Then his heart surged as he heard feet go galloping away along the donga bottom.

Frantically he groped his way to the bank. In the pitch darkness that was a wild scramble, gaining a yard, slipping back two. But somehow, eventually, he made it—to find that there, too, the fight was finished. Howls of rage and pain streamed away in the direction of the village.

"Bwana! Bwana! Is that you?" came the Masai's voice. "Is the little light in a stick unbroken? I have slain me something."

"Where's Innis? Kaffa?" was King's first question.

"Here, Bwana. Bitten by many devils."

And Innis' voice, too, panting, half hysterical. "Here. But I think I have a broken arm."

King fished for his flashlight. By extraordinary luck it was unbroken.

"Here, Bwana! Just behind this bush! My spear still pins it to—Awah! What sorcery is this?"

From King, too, came a hissing breath. The thing that lay pinned to the ground by the great spear through his chest was a man!

"I fought—I swear I fought—" King's voice came hushed, as from far away. "Damn it, I fought with a hyena! I felt it; I smelled it; I got a mouthful of its filthy hide!"

Innis' face came into the circle of light, dead white, blood-smeared, but excitedly jubilant.

"It is the rule, the absolute rule. When they die they must revert to human form."

King's mind was reeling in an insane world beyond the power of coherent speech.

"Good Lord!" he breathed at last, "we're all crazy. Come away home—the house—where there's light and a stiff shot of hooch!"

WITH lights and four more or less stout walls came a certain return to

rationalism—or, at least, a respite for thinking. Innis' arm proved not to

be broken; but badly enough bruised and twisted, at that. His

hurriedly-donned sweaters and shirts were shreds, ripped from him in

streamers. King's, better protected by his tough shooting-coat and breeches,

were in slightly better shape. But both men were a sorry mess of blood and

grime and rags.

"Though at that," said King through his teeth as he winced under the smart of iodine, "it does seem that hyena teeth would have done more damage. Innis, my crazy friend, I'm half believing in your ghost creatures. This is Africa. And if not hyenas, with what infernal things did we fight? Listen to the brutes."

The devil's chorus of howling, and the even more awesome idiot laughing, sounded up-village. In the direction—King pointed it out darkly in between holding strips of bandage in his teeth—of the half-breed Arab's house.

"Curses go home to roost, they say. Does it seem to you, Mister Consul, that they're maybe looking for a lodging around the home of our smooth friend Moussa?"

"Moussa!" King prowled the room, frowning, connecting threads of circumstance.

"Moussa! An ill-omened name in East Africa. In the old slave days Ibn Moussa was one of the most unspeakable lieutenants of the infamous Tippoo Tib. He left a trail of half-breed sons like a poison toad's spawn. Now, what reason might our half-breed Moussa have for not liking a British consul?"

Innis was too exhausted to think.

"I don't know. He has always been so friendly. Still—as a trader—I don't know."

King's mind was racing away on a trail of possibilities, vague and tenuous, but any thread was as valuable as a rope in that mystery.

"These villagers. Why are they all so dopey? What—Wake up, man!—What d'you know about any trade in drugs? Do they have opium here?"

Innis shook his head wearily. "No opium. Nothing here. Up in the Abyssinian highlands they grow k'at. It's a sort of hashish thing, only worse; sends people half-witted. And, by Jove!"—he sat suddenly upright—"Come to think of it, the French excise has trouble with it in Djibouti!"

"Aa-ah! A dope that sends people berserk. Your government wouldn't like that sort of thing, would it?"

For the first time since he had come into this so baffling affair King was able to laugh without care.

"Tomorrow, Mister Consul, I'll come and stand by while you have a long talk with British Subject Moussa. Let me put a finger on a motive and, believe me, I'll twist out of some one just what all this man-beast magic is—and tonight maybe we can sleep. Listen to those—things—up there."

But that proposal, like so many other plans in this uncanny affair, was suddenly diverted by another demonstration of sheer horror. With the morning came running feet, waking the weary white men from sleep, and the Hottentot's excited voice.

"Bwana! Bwana! The men-beasts have devoured the Arabi trader's child!"

King tumbled from his cot. "Home to roost!" were the words that framed themselves in his half sleep. "Come on, Innis! Wake up! Hustle!"

THE whole village seemed to be in hiding. The mud road between the huts

was empty. Doors remained close-locked. As King circled the trader's fence,

sounds of struggle and feminine shrieks could be heard.

"Beating her up," King growled. "As though she could have prevented it. Come ahead."

He swung round the corner of the gate post—and there he stopped in his tracks. His nostrils crinkled with nausea. There the thing lay! Dragged barely as far as the gateway! Its bright-colored clothing in shreds! Half eaten, gnawed by inadequate teeth! Ghastly. Nobody had dared to touch it—Uchawi of the blackest!

King charged on up to the house. Confused voices shouted. The door was locked. King thundered upon it. Voices babbled from within. King cursed furiously, took a run back and smashed the door clear of its hinges. In the room was Moussa. He cowered away as though King pointed a gun at him—as though the white men came with an expected accusation.

"Talk!" King barked at him. "What happened?"

The man only chattered, mumbling, his fingers at his lips. Gone was the Arab veneer of urbanity. Just now the man was pure Negro. Uchawi had reached out to him and he was mortally afraid.

From some far back place muffled moans came and a dull hammering upon a door. King's eyes went questioning in that direction. The man found his voice to drool an explanation.

"Grief, Bwana!"—He even reverted to African idiom. "And fear! They have rendered her hysterical, Bwana. She would have run forth and showed her face before strange men."

That sounded plausible enough. King let it go. The other thing was more important.

"Well, your women are your affair. But that—that thing that was your son. Pick it up and do with it whatever you do with your dead. You can't leave it lying there like a dog."

"Indeed, Bwana, I—Yes, Bwana."

"Now!" snapped King. "Or by golly I'll take you by the neck and shove you to it."

"Yes, Bwana. Immediately, Bwana."

From the doorway King watched the wretched man—alone—he could compel no servant to help him. Eyes averted, with a cloth he covered the body and hurried to some outbuilding.

"Come on home." King took Innis by the arm and led him from the compound. "I give in to you. The things that did that were man-beasts. Not clean, wholesome hyenas normally hunting their meat. There is black sorcery here."

Innis shuddered. "Thank merciful heaven they have left us. I am sure they've turned back on their instigator."

"Perhaps you're right. I'm ready to believe anything. Tomorrow we'll find out what it all means. We can hardly bullyrag Moussa in the face of his own tragedy. He will keep till tomorrow."

BUT that proposal, too, was diverted by Uchawi that was stronger than the

disposition of men. Diverted as soon as came the darkness in which magic

could operate.

With the night the devil chorus yelled and howled again around the trader's compound. At intervals came the shrieks and cries of human voices in mortal fear. Louder and more menacing than ever before was the uproar.

King looked at Innis. Innis stared back at him. Stiffly King reached for his weapon.

"Guess it's up to us. Not on Moussa's account. But that wretched white woman. We must get the boys and give a hand—and, personally, I'm almost anxious to take another shot at the men-beasts who do—what they do."

In a compact body the four men went warily up the deserted village road, this time carrying lanterns. But the chorus that made a witches' sabbath about the trader's house drew away around the fence at their approach, as though cognizant of their conquerors.

As the men came into the compound, the door burst open of its own accord and a frantic figure rushed towards them. It was the woman. She clutched at them indiscriminately. She was hysterical with fear, crazed with grief. Her broken voice shrieked high falsetto and hoarse baritone.

"My child! They devoured my child! They are devils!"

She spoke in English with a strong foreign accent. On the farther side of the fence a demoniac howl rose to drown her shrieks. But she screamed yet higher:

"They are vrikulakas! My child! They must be killed!"

"Vrikulak!" Innis seized avidly upon the word. "That's a Balkan country word for were-wolf! The country of Dracula! Tell me, woman, where are you from? How did you get here? What do you mean?"

"Ah, what matter who I am—how I came to this brute? A beast he is! A beast, I tell you! It is he who sent for these wolf-men. He gave them the k'at. My child! They have devoured my child! And how they raven for him!"

Innis motioned to King. Together they took the shrieking woman into the house, assured her of protection, partially calmed her down.

"Tell us about these—vrikulakas," said King. "If we are to fight them, tell us what you know."

Between bursts of hysteria and screaming the woman unfolded details of a grisly cult that was more revolting than anything that King had yet met in Africa.

Vrikulakas. In her country everybody knew about them. And here in Africa they were the same, only worse. They were men. They were not sane. They lived apart in packs and they had a secret beast cult of stupefying drugs and gruesome rites that made them quite mad. When they embarked upon their insane orgies they believed that they became—here in Abyssinia—hyenas. They ran on all fours like hyenas; they lived with tame hyenas; they acted like hyenas, howled like them. The maddest of them dressed in hyena skins, hunted with their foul pets, and even ate the loathsome things that hyenas ate. To all intents and purposes and their own belief they are hyenas—man-beasts. Those who dared to speak of them knew them as "Those Who Devour the Dead."

And now—the woman screamed hysterically—like hyenas they had devoured her son! And it was all the fault of that man, that brute, who called himself her husband—He knew about the man-beasts. He had sent for them because the next caravan was bringing down a big consignment of k'at.

Innis, for the time being, was more excited over this astounding revelation than about any illicit traffic in drugs. King felt that he could digest that fantastic phase of sorcery later; dig into it; find out all about it and add it to his knowledge of unbelievable things in Africa. For the present there was something else. Very quietly he asked:

"Where is Moussa now?"

"Hiding!" screamed the woman. "Hiding in the back rooms in terror; for the man-beasts now howl around the house for him!"

And howl they did. Fearsomely, in ravening chorus. Into the very compound they seemed to have come.

GRIMLY King left the woman to Innis' ministrations and eager questions. He

beckoned to the Masai and stepped with him into the dark labyrinth of a

Moslem dwelling's back rooms.

Only dim Moorish lamps burned. They groped their way, poked into closets, peered under beds. The house seemed to be empty. Servants had long ago fled.

But the Masai, probing under a pile of rugs with his spear, suddenly flushed a disheveled figure, crazed with fear and yammering. With the agility of a rat it eluded them and scurried from the room. The Masai whooped a great shout and bounded after it. Screeching, it scuttled into another room and slammed the door.

King rushed up, to find the Masai bellowing laughter and kicking at its panels with naked feet. He pushed the man aside and hurled his weight against it. It held fast. Both men crashed their shoulders against it. It creaked and a panel split. From beyond came a despairing wail and the shutters of a window rattling madly.

"The crazy idiot!" panted King. "If he gets out there amongst those—Moussa! Moussa, don't be a damned fool!"

But Moussa was beyond all reasoning or listening. Mad he was with fears that beset him on all sides. The window shutters swung open with a crash against the outer wall. There came a final incoherent cry. A scramble. A thump. And silence.

"The fool!" shouted King. "The damned fool! He'd have been better off with us!"

He rushed from the door. In a dim passage he stumbled, the Masai over him. In other windowless passages they lost their way. Only a confused uproar from without came to them.

They burst into the main room to find Innis standing awestruck; the woman with wild eyes, exultant. Here sounds could penetrate from outside. An infernal cacophony of bestial howls, satanic whimperings, triumphant yells. From farther out rose shrieks of insane terror that receded fast.

The sounds trailed away into the night. Shrieks and joyous howls and farther shrieks. At long last, silence. Only the African night outside. The insects of the night took up their trills and chirrupings that the greater clamor had disturbed.

That beast should hunt down and devour beast was the African rule.