RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

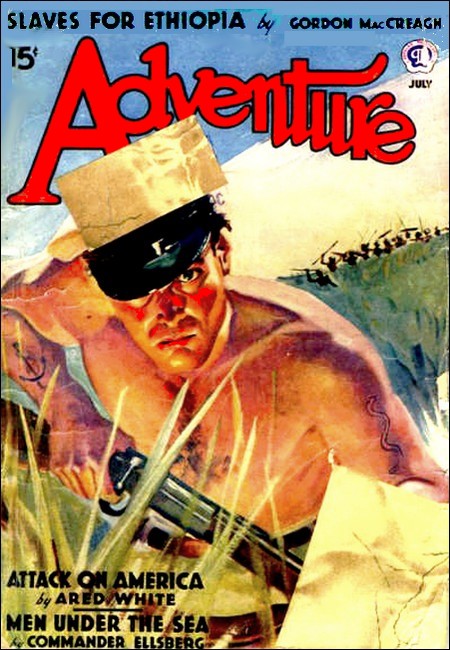

Adventure, July 1939, with "Slaves for Ethiopia"

THE raid was perfectly timed and faultlessly executed. It had to be; otherwise it would never have caught King as completely as it did.

It wasn't King's fault. King was a prisoner—on a basis of parole, it was true, but none the less a prisoner of his British Majesty's East African police, charged with heinous crimes, not the least of which was entering jealous British territory without a passport from over the controversial border of even more jealous new Italian Ethiopia.

Captain Hawkes, with two native constables, all as ragged and battle-worn as King himself, commanded the might of Empire, So King, with his big Masai henchman and the six that were left of his sturdy spearmen, slept the sleep of the careless in safe and well-policed British territory.

It was then that the raid came. The raid was commanded by Ibn Faraq the Fatherless, with some fifty hellion Arabs as hard-bitten as himself. It was one of those things where fools rush in where angels fear to tread and often enough accomplish what wiser angels would not attempt.

Not that Ibn Faraq was anybody's fool. With the stigma of Fatherless upon his youth he had to be as clever as a devil and as ruthless, to rise to the eminence of best hated slave trader in all southern Arabia. It was just that Faraq didn't know about things and people along the Kenya-Ethiop border.

But that didn't deter Faraq for a minute. Slave raiding over the Ethiop border and then juggling the catch back and forth over the line as pursuit threatened, had been a profitable game for men who were bold enough ever since the border had been argued about.

In the good old days of the Ethiopian regime, nobody on that side of the line cared an awful lot, and dusky Ethiopian Rases who had slaves of their own were not averse to a little clandestine connivance, despite the death penalty decreed upon slave trading by their enlightened Haile Selassie.

In those days the game had been easy. But now that Italy was master, things were tightening up, even though the border was still far and roads were not at all. The Hadramaut market offered ever better prices, and every Arab knows that Allah created Africans for the purpose of being slaves.

So Faraq the Fatherless swore by the Prophet's coffin that was suspended in midair in the revered borderline between the empires of men and angels that he would go over and look for himself over this border between the empires of Italy and England, neither one of which he revered at all in these troubled days when men didn't know upon just whom Fate was laying the favorable finger.

When Faraq swore by the coffin he no longer hesitated, for he had much experience about the close connection between vacillation and coffins. So he loaded his fifty good men and fifty good Japanese rifles into his big sailing dhow that was now lying up in one of the creeks behind Port Durnford, and here he was, savage enough at the scarcity of good slave meat to tackle anything—and what matter if a couple of white men slept so carelessly in this wilderness? Faraq had much experience, too, in the technique of night raids. The first thing King knew about it was a muffled yell from a startled police sentry who should have been awake; and before he could swing his legs free of his cot; the tent in which he and Hawkes slept peaceably together collapsed upon them like a net, its ropes cut, and strong arms and legs swarmed all over it, flattening out cots and poles and everything under a smothering blanket of canvas.

King had caught leopards in that kind of trap—strong canvas that fell at a given word upon night creatures nuzzling over bait, and strong men who then rushed out and swarmed all over it. He preferred canvas to a net for the reason that a leopard's claws—or a lion's—might puncture the canvas but couldn't rip it.

Out of the wreck of his smashed camp cot, in pitch blackness and smothered by heavy bodies that swarmed all over the tent, the best that King could do was writhe like a grub in its cocoon till, inch by straining inch, he was able to work a hand down to his hunting knife and stab blindly at lumpy weights that pressed over his face. Somebody yelled in an agonized pitch; hot blood came through the gash in the canvas onto King's face, and then more weights pinned him hopelessly down. Somewhere in the choking blackness of dust close beside him he could hear the angry splutters of outraged imperial dignity.

"By Gad, I—Somebody will smart for—Ugh! Some of these border tribes need a—Oo-oof!—damned good lesson, by Jove."

King saved his breath. He had no illusions about dignity. He knew that people who jumped white men's tents at night were not worrying about anybody's distant retaliation.

His limbs were limp with sheer suffocation before he was dragged from the trap, swathed with ropes, as he had himself many a time dragged a furiously fighting leopard.

FAULTLESSLY executed. With the exception of the man whom King had stabbed

through the canvas, the whole affair had been bloodless. Slave meat was

valuable cargo these days. Not like the extravagant days of Tippoo Tib, whose

Zanzibari Arabs used to come howling with fire and sword and trade musket

into an African village and counted themselves well paid if fifty men out of

a hundred lived and lucky if as many as half of those ever reached the

market. Nowadays a live slave was worth very much more than the free marauder

who might have died capturing him.

Even Barounggo, the big Masai, stood trussed, wrist and foot and knee, and the broken haft of his spear twisted the cords behind his back. An Arab was balancing the great blade of it, smiling happily.

"A guard put to this stub of a haft," he was saying. "And this thing will make a fine sword for me."

Faraq the Fatherless was well pleased. He sat on a pile of the white men's hurriedly collected camp gear as on a throne, his elbow on one knee, his fingers clawing gently through his beard in thoughtful appreciation. A long lance leaned against his shoulder. A horseman in his own country, he retained here, where the tsetse flies killed off all horses, this symbol of desert manhood.

Torches lit the scene. Black shadows, dingy whites of the Arabs' clothing that billowed ghostly in the night wind, red lights on their Japanese rifles, already rust-spotted. At the outer edge of the torch flare lumpy shadows were already captured slaves, crouched in stolid African apathy. A line that glittered in and out amongst them was a chain to which each man's wrist was handcuffed.

Faraq's heavy-lidded eyes glittered like the metal as he nodded. "These be men worth the catching, not like these scrawny villagers of the last two weeks." The metallic eyes stopped their roving on the Masai; white teeth flashed out underneath them. "That one alone, well tamed and delivered safe in Hadramaut, will pay half the cost of the hunt."

Barounggo saw that the chief spoke of him. He glared back. Fierce in his pride, he growled an announcement that ought to correct this foolish mistake.

"I am Barounggo. Elmoran of the Masai. With these six askaris I serve the Bwana Kingi."

Faraq lifted an eyebrow at one of his men, who understood Swahili. At the man's translation his smile was wider. "Yah, Ahmakhat. Tell the fool that the Kaid of Tefalit will bid as high as two hundred English gold pieces for him."

Barounggo's muscles, already swollen over his cords, bunched so that the lights glinted off them as hard as from the guns. The Arabs behind him laughed. They had tied many a strong man before this.

Barounggo swallowed down his personal rage for a later reckoning. First to correct this mistake. He knew what was proper. It was not fitting for a white man to announce himself. Let this mad Arab but know who was who, and the thing would be settled with apologies and surely with gifts to pay for indignity; though for himself blood would be the only apology.

"This white man," he announced, "is the Bwana wa policea of the Britisi serkali."

"And that," Captain Hawkes told King with an angry satisfaction, "will change the fellow's tune in a hurry."

Faraq the Fatherless only rolled his eyes sourly to rest on the bedraggled majesty of the Law. He looked at the officer without expression and without comment. Barounggo's eyes rolled in wonder. The long-reaching might of British law and order was something that even King didn't buck.

"This one." Barounggo intoned it as a good servant should. "This one is the Bwana n'kubwa Kingi, whom all men know. Mwinda ya ndhovu, na wagasimba, na pigana ngagi na mikonake, hunter of elephants, slayer of lions, who fights gorillas with his hands." The extravagant titles rolled sonorously forth. "Who shoots and does not miss. Who burns up his enemies. Who—"

"By Jove!" Hawkes was still confident enough to let go a short laugh. "You'd think the colonial police are nothing here. Is the man reciting your deeds or is he just bragging?"

The recital brought response, though not as overwhelming as the Masai had expected. The Arab who knew Swahili and the East African Who's-Who cried out, "Wah Allah!" And he told Faraq quickly, "Har'm. This one is forbidden. Evil fate comes to those who meddle with him. His name is ill luck."

Faraq, who knew nothing of Africa, said only: "Peace. I am not a fool to hold white men. Nor will anybody buy them in any market. Take the two out and turn them loose. The rest we hold. Away now. Swiftly."

That was the faultless technique of Tippo Tib, whose reputation was that a million slaves had passed through his hands—a well planned raid, well executed, and away before pursuit could be organized.

A CHILL dawn, dripping dew as heavy as light rain, slanted its light on

King and the representative of Empire, crouched under a huge wild fig tree

for its protection. Alone in an empty plain that undulated away to every

point of a dusty yellow horizon; foodless, fireless, weaponless, stripped

down to every last item of any value. The raiders had taken everything and

gone.

Alone as far as human companionship or aid went. Game was plentiful enough and with an instinct of security that must have been instilled by the devil they browsed closer than Hawkes had even seen them. King could have thrown a stone into a herd of Semmering gazelles.

Utterly alone and utterly forlorn. But King was able to grin at the police officer. Hawkes was savagely furious. His ruddy British complexion was blotched white with anger; his fingers kept twisting his once trim military mustache. It was King's grin that brake through his control to flare out:

"I suppose you're grinning, you damned Yank, because you think I won't be able to take you in now. But no fear, my lad, I will." It was anger and pride speaking. King could have taken and broken the man over his knee almost as easily as could the Masai. His hard lips spread a little wider and he settled his big shoulders back, like into an arm chair, amongst the great flaring roots of the tree.

"You don't mean that, copper."

"Oh, don't I? By gad, if it takes the whole British army, I'll—"

"Yes, yes, I know." King's level brows went up, half mockingly. "I've heard it all before. But you've forgotten one thing."

"I'll take you in if it's the last thing I do before I have to resign my job over this disgrace."

"You've forgotten that those filthy pirates have my man Barounggo and six of his men. I can't go with you now—not yet."

Hawkes looked at him as though he had been physically hit, and then his normal redness flushed deeper.

"Sorry, old man. I was talking rattled. A thing like this happening, don't you now. Really awf'ly sorry. Two of my men taken too. But, dash it all, what can we do?"

King's smile hardened.

"Go after 'em," he said simply.

"Of course, old man. Certainly, and all that. But placed as we are—empty-handed, you know—"

"You forgot one more thing."

"What?"

King's eyes narrowed, as though contemplating the not unpleasant prospect of possible action.

"That my other man, the Hottentot, is about due to meet us somewhere along this trail with that new English rifle that you touted so high that I had to send for it."

Hawkes clapped his thigh. "That's true. Splendid! We'll be able to feed ourselves and—" Hawkes' enthusiasm went out cold. "If those bloody bandits don't catch him as he comes along, all unsuspicious."

"Not that one." King's grin went sidewise at Hawkes. "He won't be lying up any place, safe in charge of your British law."

Hawkes took the thrust with a chagrined grimace. "Mea culpa, old chap, and you don't have to rub it in. I suppose I'll have to offer my resignation and all that. But anyway, if he comes through—"

His jaws tightened. "We'll be bound to catch a native runner sooner or later and send him in to Todali outpost with a wire for reinforcements, and I'll at least take my men back with me."

"By the time your official reinforcements are organized," King said with conviction, "those fellows will be to hell and gone with no trail behind 'em. That's plain raiding history. You go tag along with your platoon that won't dare cross an international border. Me, I've got to step right after their trails while they're high and going."

"But dammit, old fellow, what can the two of us do against them? Fifty of 'em, well armed."

King grinned at him, almost fondly. "So you would bull-dog along, eh?"

"Well, er—If you're so blasted bent on being crazy, what the deuce else can I do? Though damme if I like it. That business you dragged me into against those juju devils was shivery enough, even with all our men. But two of us! Alone!"

"Us, and the Hottentot," King said. "And he'll have his own gun, that military .303 that you insist I must have stolen, since they're not for sale, though I can show you where you can pick up a hundred of 'em. Maybe you'll get a chance to use it and show how well a soldier can shoot. Though I'm hardly figuring on that." He stared hard-eyed into the distance, his mouth a thin crooked line. "It'll all hinge on that new rifle. If it's as good as you say—" He shrugged useless speculation from him till the rifle should come. "Come on. We'll build a high smoke for the Hottentot, and if you must eat, I'll show you how to snatch mjumbakaka lizards under the rocks. As good as frogs' legs at time."

IT was afternoon before King jumped up with a glad "Ha!" A black speck like an ant was crawling over the rounded top of a far kloof. "He has made wonderful time; we've that much luck with us."

The Hottentot put on a spurt of sheer bravado and arrived at a trot. A small man, as wizened as a monkey and as wiry, he was dog weary but as cocky as an ape that has performed a good trick. He panted his first complaint.

"This new gun, Bwana—it weighs at least two pounds more than any proper gun should. Carrying it and my own and cartridges has broken my liver. There should have been a camel."

"It was good running, Apeling," King said. "There will be a new blanket with zig-zag stripes, and the extra weight will be equalled in tobacco."

"Whau! Assant, Bwana." The little man wriggled his quite surprised thanks, suddenly abashed at the munificence of the reward that his complaint had craftily played for and that he had never expected to come so easily. "Where is that great oaf Barounggo and his askaris? Can I not be absent a few days but that useless fighting man leaves his master in a plight that one would expect of bushmen savages?"

King's lips bit hard and all the angles of his face stood out like strained muscles. Soberly he told the Hottentot about the raid.

"And therefore," he said grimly, "much depends upon this new gun."

The Hottentot's pose of jealousy of his master's other servant's mere brawn was forgotten in quick concern. All his actions were those of an enraged ape. He jumped up and down grimacing with his mobile lips. He threw clods of earth in the direction where the slavers must have gone.

"Then for what do we wait, Bwana?" he chattered. "Let us away. We can raise the tribes against them. Look, Bwana." The little man's mind raced as alertly as a goblin's. "On the Ethiopian side the Has Woilo; for a promise of aid against the Aitalian conquerors, will lend us a hundred of his spearmen who hide in the hills."

"Even that I may do yet," King said without a qualm. "I wait only for this gun. Observe now, Kaffa." His eyes roved far to pick out a suitable mark. "That broad acacia trunk; five hundred yards I guess it, and full five hundred I shall need. Go and hew me the bark from it at man height, so that the white shows clear for a space the spread of your two small hands and stand then clear to signal. But first eat. There are fat lizards in the hot ashes."

Kaffa spat disdain. "What is food, Bwana, that it should delay vengeance? A man hunting blood eats when he may, or the day after that. I go. A space of one hand spread, Bwana, is better for a sighting. What is five hundred yards to the Bwana Kingi?"

Hawkes looked after the little trotting figure.

"By gad!" he said. "How do you get them that way, my dear chap? We can't."

King laughed shortly.

"You fellows rule them," was all the explanation he gave. He took the new rifle from its canvas case. His eyes sparkled over it like the sun on its fine mechanism. He talked to himself and it rather than to Hawkes.

"Jeffries magnum .300, eh? The best long range big-game gun in the world, are you?—Ten pounds without scope, twelve with. Well, you'll be needing all of that for your power. If you're as good as you look—" He squatted down on a low termite mound and scuffed holes for his heels.

Hawkes ventured criticism. "I say, old man. Hadn't you better take the prone posish to sight at five hundred?"

"Live targets," King grunted at him. "Fifty of 'em, coming yelling at you with guns that are no old trade junk, don't wait for you to take prone positions in between getting up and running."

He snuggled his eye down to the scope and then cocked his eyebrow over it at Hawkes. "Damn if this thing ain't as good as any German scope I ever looked through."

It drew Hawkes like a defensive wasp. "Well, rather, my dear chap."

THE feel and balance of the gun chased King's somber mood from him as

though he might have been fondling a beautiful woman. He grinned at Hawkes'

patriotic stuffiness and adjusted the scope to five hundred and snuggled down

to it again. The slash of white on the acacia stem looked about as big as a

watch. The Hottentot stood appallingly close to it, nonchalantly at ease.

"Damned little fool," King muttered. "He does that just to brag about me. Some day he'll—" But he fired.

The Hottentot took off his loin cloth and stood naked. He waved it in a weird wig-wag system of his own. King grunted and twiddled the micrometer mount.

He fired four times. The Hottentot pranced like a naked imp and wigwagged wildly. King stood up grinning happily.

"You Britishers always did build a good bull gun. So then I guess we're set."

"If you say so. But, er—won't you let me in on a little bit of your mad programme, Yank?"

King's deadly mood came down upon him again.

"Sniping," he told Hawkes grimly. "Ever see the damage and demoralization a good sniper can do? I'll pick 'em off, by God, till they'll talk terms. Harry 'em back and forth over the border; I may even have to enlist with the old rebel Ras Woilo against his new white masters. But I'll get my men back."

Hawkes stared at him.

"I suppose," he mused aloud, "that's how you get 'em to be that way." Then he shrugged. "Well, I'll be having to resign anyway. So—"

They shook hands on it.

King was counting cartridges when Kaffa came back. He whistled tunelessly through his teeth. "Only five packets. Fifty thin rounds! And five of 'em fired on sighting in."

"And fifty raiders with modern rifles." Hawkes gloomily added up the mad prospect.

Kaffa stood on one leg and scratched at his knee with the other, squirming like a monkey on a tight rope. The little man understood English, though he tried never to let on about that.

"What evil is on your mind, Implet?" King demanded.

The Hottentot looked far afield and his little black eyes were inexpressibly mournful.

"Fifty," he said, "was all that that Inglesi shopkeeper would deliver with the gun, saying that he required to keep the balance for other such guns. Therefore, Bwana," He brought his scratching foot down and stood ready to jump. "Knowing that Bwana must have a need, or he would never have sent me for the gun, it came into my mind to steal two packages." He produced from his meager loin cloth two flat packets of shells.

"Whee!" King whooped. "Twenty more shots!" And then he forced his expression down to seriousness. "For that, little devil's spawn, this hidebound policeman will put you in jail; or at least will fine you much money after restitution is made. But, for this once, I will myself pay it."

"By gad!" Hawkes was as ill at ease as the Hottentot. "I suppose I'll have to lag him. Clean up the job and all that before I resign. But the fine is on me. Really, old fellow, I insist."

King cuddled the extra cartridges.

"Maybe," he said, "you won't have to resign. Still an' all, sixty-five shots allows all too little for misses. Guess we'll have to live on lizard meat."

Hawkes twisted his raggy mustache to its best semblance of good form.

"Good enough grub for the last few meals of three crazy men," he said.

THE next day's sun was beginning to throw long shadows before them when

Kaffa pointed silently to the sky. King considered the birds wheeling in high

watchfulness.

"Ha! Not anything dead, or they'd be dropping. Not game, that high. Men."

"And camped," the Hottentot supplemented, "or the birds would not be so many. And who but a slave train would camp this early?"

"Come on," said King through his teeth. "Edge over to that hill."

He said nothing more till they crouched on the hill's top and looked over the plain to a straggle of men under a group of far mimosa trees. Then he said, more as a statement than a question.

"You Britishers got an old law, haven't you, that a slaver can be shot on sight?" The distant men, hard black and white in the direct sun, looked like little penguins.

"Why, er—I don't know. I—"

"You pulled it on the old blackbirders often enough. What d'you figure the distance?"

Hawkes judged it with military precision. "Seven hundred, I'd say. But, dammit man, you're not going to try from here? Out in the open hilltop like this? They'll rush us like howling dervishes. And no defensive works."

"Majuba Hill," King told him laconically.

"By Gad! Were you at Majuba? But you couldn't have been, what?"

"Before my time." King was kicking heel holes for himself. "But from all the telling, there were some Boer Africanders dug no trenches at Majuba; only defense was clean shooting." He was shuffling his buttocks into the stiff grass. "And the best they had was old Mannlichers, nor any scopes, either." He clicked the scope up to the seven hundred. "And the light is perfect, smack on our back, and the wind dropping to nothing for sundown."

The Hottentot stood as motionless as a well trained caddie, awaiting the drive. In a low monotone he said; "That tall fellow, Bwana, who stands clear of the tree there."

Hawkes fidgeted with the rifle that he had taken from Kaffa. He drew the bolt, made sure that he had five in the magazine, pushed one into the chamber, sighted in the direction of the far mob.

"Crazy Yankee blighter," he kept grumbling.

King turned one sardonic eye on him. "Better hold it till they're into two-fifty. Those open army sights are something sinful on shells beyond. And if we can't stop 'em then, I hope you can run just a leetle faster'n them. You know any prayers?"

He brought his eye down to the scope. His teeth clicked together with the soft cluck of the set trigger. His breath held tight and he pressed the last fraction.

The tall fellow who stood out alone just disappeared into the knee-high grass.

"Oh, shooting!" Hawkes breathed. "Shooting indeed!" Just as though commending a grand play at cricket.

There is—and unfortunately so—an astounding callousness that descends upon men after they have once justified to themselves the need of taking human life.

There was no more question in King's or the police officer's mind as to the propriety of their lone-handed war than there was in the Hottentot's.

"Hell!" King grunted. "I've seen even soldiers score a stationary target at a thousand. But it won't be so easy now."

Thin cries floated back to them and men scurried as aimlessly as ants. In the tenseness of waiting even the Hottentot was whispering. "They have not seen yet whence came the death. Look, there stands another one staring."

King fired again. That one disappeared into the grass.

"Spotted us now, by golly!" His tight grin was on his face as though painted on a robot of steel and wires. "Here they come."

MEN streamed out from the camp, yelling, waving guns. There must have been

full thirty of them, every one fiercely bent on achieving the honor of

annihilating the three on the hill. Some stood long enough to fire

aimlessly.

"Dopes!" King fired again. His words formed themselves in his throat rather than on his lips. "They'll learn to run zig-zag before we're through." He fired. "And near half a mile is a lot of running in stiff grass." He fired again. "Ha! Atta gun! Hundred percent so far. Whites o' their eyes, hell. But—" Again. "They got guts."

With merciless method he picked the foremost runners so that those behind could see them drop. But they kept coming, yelling hoarsely. Bullets began to kick dust and to buzz like wind-driven hornets. King was not ashamed to duck after each near one had passed, but he held grimly to his position.

Hawkes cursed him.

"One lucky hundred and eighty grains is all they need, chum." But with obstinate pride he sat stiffly upright alongside of King and made a point of it to expose himself every bit as high.

The Hottentot had no traditions of national pride. He lay as flat as a beetle. King's words, his cheek distorted hard against the butt comb, came as a hissing jumble. "Try your luck, soldier. It's stop 'em now or run like hell." And then, "Whoopee! They're winded and down to a walk."

Hawkes began to shoot. King was too furiously busy to look, but mechanically he kept grunting: "Watch shells. No ammunition train behind us."

Suddenly the Hottentot leaped high and waved his arms. The men below them were dropping to the grass for cover from the murderous accuracy of the fire from the hill. King snatched out a hand to the Hottentot's ankle and jerked him sprawling.

"Monkey head!" A bullet passed. "Whit!"

"By George, we've got 'em!" Hawkes laughed with the cracked exultation of men in the hot surge of battle. "We've got 'em. They've no cover!"

From their eminence they could look down on the shadowed depressions in the tall grass. Hawkes dropped to the regulation prone position and picked out his targets. King grunted and followed suit. Lying down, the Arabs were shooting closer than even a madman could afford to deride. The furious speed of King's movements settled down to cold method.

"Whoever runs now won't be us, by God. Allow to shoot just over the grass tips, and it ought to get 'em in mid-spine."

A few hot seconds ago it had been yelling figures full of furious life that disappeared every now and then into the long grass. Now, every now and then a yelling figure lurched out of its shadowed depression and dropped back to make a new sprawled shape.

It takes hard disciplined troops to stand that sort of thing—troops of the sort that had died in their thousands and stuck to it and finally won the murderous hill of Majuba. These slave raiders were not of that breed.

Somewhere out of the grass a man wailed. "Wah Allah kerim!" for God's mercy and protection, and jumped up in a frenzied dash for the camp.

Hawkes whooped and let go. The man curled like a rabbit and rolled for yards.

That was the break of panic. One after another, and then in a yelling mob, the Arabs jumped and raced for their lives, each frantic not to be the hindmost; and behind them came the devilish bullets, smashing at their backs.

King sat up and fondled his rifle like a lover, only his words were not at all romantic. He said in plain hard American: "That's learned the dogs some."

Hawkes was breathing normally again. He paid King the highest compliment he knew.

"By God, sir! You should have been a soldier. Your selection of position and tactics was masterly."

King turned and peered through his rifle barrel into the low sun before he grinned complete satisfaction at what he saw and said: "God forbid. I may get my tough sledding against your damned officialdom, but I'm my own boss." He looked down over the late skirmish ground, now in the shadow of the hill, and grinned out wide. "I'm a trader. Come on, Kaffa."

"What mad thing now?" Hawkes had to know.

"Rifles." King said curtly. "You soldiers leave 'em on the battlefield. Not me. There's no government buying mine. Should be about twenty scattered around—and cartridge belts. Sun smack in their eyes, we're safe as bugs in a Kavirondo blanket."

The official in Hawkes rose to protest. "You can't trade rifles in British East."

"Copper," King laughed at him, "You'll never know where I trade 'em." And darkly he added: "I may have to trade with rebel Ras Woilo if I can't win my boys back any other way."

"But—Dammit, man." Hawkes' whole credo was violated. "You can't do that—arm natives, you know, against white Italian rule."

"Yeah," King snarled, "and the Arabs are brown and my Masai and his boys are black. But they're my boys! Get it?"

"By gad!" Hawkes breathed. "Yes, I think I see. You still should have been a soldier."

"C'mon," King said roughly. "I got to get those rifles and find a cache for 'em before the lions come around. An' then we'll have to hustle us up a good roost in a tree."

Later, examining those good Japanese guns, he shook his head. "Pity. These cartridges and all. Damn, if it wasn't for lions we could annoy those fellows a whole lot all night."

FARAQ the Fatherless was no fool. Lions, he knew, could be a menace to a

few men at night, but not to a caravan. In the darkness he silently folded up

his tents and slipped away from under rifle range of that accursed hill.

With daylight King didn't even bother to go up and scout. He looked for circling vultures and laughed. "African spotter planes. And there'll be other hills behind 'em, and three good men can always outwalk a caravan. C'mon, let's hunt lizards."

There was an element of the terrifying in that remorseless pursuit. If not for the fear it engendered in the raiders, it would have been ludicrous—a raiding army running before three. Not that those fierce Arabs would ever had admitted they were running. But Ibn Faraq cursed savagely and judged it wise to make for safety with what winnings he had. True, slaves were worth twice as much as free guards, and his slaves had remained immune; but if he should lose many more of his guards, there could still be naked spearmen by the way who would lash themselves with howling and drums to a frenzy of retaliation.

So Faraq lashed his slaves with whips and blows to make the best speed that could be beaten out of them. And King laughed grimly and presently topped a hill behind them.

Moving men with their slender height were of course more difficult to hit than moving game at the same distance, but King's sniping remained deadly. He didn't hesitate to lie down now in the prone position for long range shooting.

"None of 'em fool enough to try rushing us again, is my bet. And even soldiers can target at a thousand feet, shooting this way. Hell, I'll even call the shot."

The Hottentot, like a top grade caddie called it. "That one with the black cloak, Bwana; he will be a chief."

The black cloak lurched forward before its owner ever heard a shot. The three could see a furious scurrying along the length of the black line that was slave meat, could see arms rise and fall, knew that the arms held whips.

The column drew out of range. Men milled behind it in a confusion of distant yelling. King risked a long shot at running game. The Hottentot clucked querulous disapproval. King only laughed in short barks. There would be still other hills in a three weeks journey between here and the coast. A lot could happen in three weeks.

It could happen, of course, to either side. And Faraq the Fatherless had not attained his rank through any fatalist habit of letting Kismet do whatever it would to him. Faraq drew some of his men together and harangued them.

It was the Hottentot whose monkey alertness first spotted Faraq's manipulation of Kismet. When they next caught sight of the caravan it was well out of range; but Kaffa, whose eyes had never been ruined by education, peered at it under his hand and then gave of the education that he knew.

"Bwana, the dust that they made rises not so high. Therefore it is in my mind that they travel not so fast."

"Ha! Getting tired out." Hawkes said.

"And Bwana, they pass close to that hill ahead of us, which a wise man must to do; yet it is in my mind that Arabi surely have learned to be a foolish thing chief is surely not a fool."

"By Jove! I wonder what's ahead. Maybe a war party."

"Not ahead. It is in my mind that the men who walk are fewer in number; yet we have not slain so many."

"Aha!" King stopped dead. "Little wise ape, there will be two blankets and enough tobacco to buy a little ape woman. Not a fool, surely, is our slaver."

Hawkes did not as yet get the Hottentot's devious reasoning. "What's the delay?"

"Ambush," King whispered. "Waitin' for us right along the track we'll take for that perfect sniping hill. So we just won't. We'll circle, and maybe we'll spot something from that kopje. Bet they'll be lying up in that patch of nyika grass."

THEY were. A dozen of them, lying in wait with the crafty vengefulness of

buffalo. When a flanking fire broke on them from the hill that they had never

suspected they fired no shot in return. They bleated and ran like woolly

sheep, their billowing jellabahs marking them out against the yellow

grass for the slaughter.

"Apeling," King told the Hottentot, when he dared waste no more cartridges on the range, "there will be two women and the price of a cow."

The next high ground showed the caravan headed due north and hurrying like haartebeeste harried by lions. King looked from the distant scurrying figures, and his mouth twisted hard with a disappointment that was none the easier to take for all that he knew it had been bound to come.

"Here's where you're through, Britisher," he growled. "They're working the old trick of heading for the holy Italian border line that you dassent cross without your permits and your passports and all your mess of official red tape. Guess it's a lone hand for me from now on."

Hawkes watched the slave train go and his frown echoed, showed the struggle of the ingrained law-abidingness in him. His shoulders jerked in a short shrug.

"I'm through anyhow." His anger flared out. "And damn your eyes, Yank, don't you forget there's two of my own men there whom I dashed well will take back or stay here with 'em."

King reached a long hand to the other's shoulder and shook it.

"There's times," he said, "when I think a soldier is pretty near as good as a free man—even a British soldier."

"Come on," Hawkes said brusquely. "We can get another pot shot or two in before dark."

The Hottentot let it slip once again that he understood, though he pretended that he spoke only out of his observation; and as always, he shrouded his words with the circumlocutions of native thought.

"It is in my mind, Bwana, that the Bwana Mwewe, in his eagerness for slaughter, has forgotten mwewe's wisdom."

Mwewe meant hawk, so the Bwana Mwewe was as inevitable as though so designated by his sponsors at his baptism.

"What now, Little Wise Ape?" King was never so cocksure as to pass up anybody's advice. "And let it not be an impertinence just because a little wisdom has newly earned you a cow."

"Nay, Bwana, no impertinence." The little goblin stared with solemn eyes. "Who in all this land would offer an impertinence to a bwana of the policea, when even the mkubwa Kingi shows him respect—without fail?" He remained carefully just out of King's reach. King, out of the corner of his eye knew it. So the Hottentot went on to expound his observation. "Only it is in my mind that when mwewe is hot in the hunting, the quail hurry to cover beneath the bushes; whereupon mwewe, being wise, hides behind a tree; and when the birds, feeling themselves safe, emerge to fluff their feathers in the dust of security, mwewe swoops to great slaughter."

"By jove!" Hawkes' military mind grasped the simile quicker than did King. "The fellow is right. Bring up the artillery when the enemy thinks he's safe over the line. Biff 'em when they're bivouacked for breakfast. Demoralize 'em no end. By gad, I'll buy the boy another cow!"

THE demoralization that Hawkes predicted was as complete as anybody could have hoped. Bivouacked the slave raiders were. For breakfast, for rest, for surcease from that relentless harrying against which their only retaliation was impotent rage.

At the edge of a water hole they sprawled, under trees. Careless smoke went up from cooking fires. Safe. Over the border—well over it, where there could be no doubt about international lines, where the governing headquarters were a month's journey away and where foreign officialdom dared not follow.

A perfect spot, such as slave raiders had picked throughout the long years.

When the first man suddenly pitched on his face over his own cooking fire and a full second later the far pop of report came, there followed a full five seconds of unbelieving silence. Then men scuttled for cover, throwing dust from their heels like veritable quail. A full second later their screams floated back on the morning breeze.

A bold few, enraged to desperation, started a half-hearted charge towards the hill. They could see nothing with the sun in their eyes; but there was a hill and from it the sniping must come. So they charged, yelling, brandishing guns.

But first one man dropped, and then another, and the charge broke up and streamed back to the water hole, where there were trees with fat trunks behind which to shelter.

"They've learned," King breathed.

Frantic whips rose and fell. The slave column, like a long black snake, writhed into broken movement and staggered away. White draped figures straggled after them, northwards, away from that deadly range. Fires remained burning; pots remained over them; lumpy bundles remained on the ground.

Kaffa scurried over the deserted camp with all the inquisitive ardor of a baboon turning over rocks for grubs. He came to report with as much glee as one that had found a locust colony.

"Loot is here, Bwana; four good daggers and seven cloaks that smell bad and a sack of wheat meal and cooked food in the pots which they will not have had time to poison. Only the meat that scents the air is that man whose face fell into his own fire."

"Pah!" Hawkes grimaced. "I had been thinking of venison." But his instinct was to turn to the strategic values of things. He was exultant. "Victory, by Jove. Victory with captured commissariat."

King remained dourly dissatisfied.

"This is coming too easy," he said. "Africa isn't that kind. That slaver devil will be dealing some hell out of the deck yet." Savagery bit through his voice. "And he still has our men. Let's eat and on."

THE next hill showed how sorely the relentless sniping had taxed the

raiders. A little straggle of men was walking across the plain—plodding

slowly and openly on the back trail.

King jerked his shoulder to throw off his rifle sling with an expert movement that slapped the gun into his hands.

"What fancy trick now?" he wondered.

But Kaffa hopped on one leg in excitement and said: "Bwana, that tall fellow amongst them who walks like a stork, nobody could be so ungainly but our Bukadi; and that other who leads with his head low, that one is surely Ngoma, the trail smeller—and they come unbound, as free men."

"Eight of them." Hawkes' voice broke high in its tenseness. "Capitulation, by gad! Return of prisoners."

King's voice was hoarse. "What of Barounggo, little ape? Do you make him out?"

The Hottentot stopped hopping. He peered under his hand. "Nay, Bwana, that great oaf I do not see." His voice was anxious. "And his form surely would stand out from the rest." He tried to be optimistic about it. "Perhaps he follows with a message."

King walked the hill top with long strides; his scowl was deep cut in his face.

The men plodded to the hill top. Two of them came to attention and saluted Hawkes. The other six said, "Jambo Bwana." But there was no big-toothed grin of greeting on their faces.

"What of Barounggo?" King snapped at them.

Ngoma, the trail leader, reported: "Bwana, that man who has no name, having no father, said: 'In the name of Allah let there be peace'. And he said, 'Tell those white men,'—and he cursed you in the name of many devils—'tell them that no man who has fallen into my hands has ever escaped alive. Yet I do what I have never done. I return eight of those whom I have taken'."

"What of Barounggo?" King snapped again.

"Barounggo, Bwana, is alive, though beaten with many whips; for one who beat him came too close and Barounggo, his hands being chained, smote him with his foot and that man died on the second day in great torment."

"What of Barounggo?" King thundered at them.

"Barounggo he holds, saying that his price alone will pay the cost of his losses. Therefore, he says, let there now be peace, lest a worse thing happens."

"Peace?" It exploded from King. "While he holds Barounggo? I'll—" His shout choked down to a small dry question. "What did he mean, lest a worse thing happen?"

"That we do not know, Bwana. He is an evil man and his rage is like a trapped leopard's."

"By God, if he—" King took a huge breath to hold back futile threats. His men shuffled uneasily before him; it was not their fault, of course, that their great Masai leader was not with them; but they felt as privates must who have accepted liberty while their officers have been held.

The lines of King's scowl remained just as deep, but the shape of them began to change to his thin, hard-lipped grin. He said:

"All right, you men. There will be a running for this day and this night and the next day. Kaffa knows where rifles are hidden. With them you will be men once more."

Kaffa jumped high and screamed his sudden exultation. The men stood and stared like oxen with white rolling eyes till the significance of it broke on their slower minds. Then they shouted their cavernous African laughter.

"Give us but a bellyful of meat, Bwana, and we run for a week of days and nights. Free men we are, but our manhood remains bound in the iron chain of those Arabi dogs who eat women's food. Give us meat as we are accustomed and we run for the slaying."

"By gad!" Hawkes murmured. "If we could put that spirit into a regiment!"

King's grin broke sardonically on him. "You heard what they said? Free men. They don't fight on order from far away politicians. This is their own grudge fight."

Hawkes frowned at that blasphemous philosophy, but he didn't argue.

"With weapons," he said, "you'll have a small army."

"I'll have?" King's cold stare matched Hawkes' frown. "What about you? You've got your two back."

Hawkes turned to his two men, his voice crisp.

"T'shun," he told them. "Take orders. You two will go with these men. What this little Hottentot commands, you will obey."

The two saluted. King laughed at the gaping men.

"All right, Kaffa," he said. "Away. You have a Jaipani rifle. Feed the men well. By tomorrow's falling sun we expect you to catch up with us. We shall leave a well marked trail, so that there may be no delay."

Kaffa laughed. "Nay, Bwana—what need of a trail? Not a man here but will smell his way back to the vengeance."

KING and Hawkes squatted alone on a hilltop that King had warily chosen with the sun at their backs. Hawkes frowned down at the slave raider encampment, a mile away.

"The blighter is getting clever. Plenty of trees for cover and a good water hole. Dashed good defensive position."

King's eyes ranged over the hazy landscape. He cocked one eyebrow at a far herd of galloping zebra.

"Scented lions," he commented without interest. "Probably lying up in that donga waiting for supper time." With a little greater interest he pushed his chin towards a thin plume of smoke above the foothills to the North. "Probably Ras Woilo's rebel guerillas waking up to the doings over the border."

"Ras Woilo!" Hawkes' interest was much greater than King's. "Ha! Then we have 'em. The Ethiops harryin' 'em from that side, and our own fellows ought to be along this evening with those rifles."

King shook his head. While his big Masai remained a prisoner his experience of Africa could conjure up a hundred deviltries.

"Not that easy, soldier; not in Africa. And the Ethiop can't change his habits any more'n his skin. It'll take 'em a week to get organized anyway; and what's more, if Woilo cuts in, there'll be complications—like rifles, and your damned official conscience. It was all you could stretch to come over the border into foreign territory. If I have to make a deal with Woilo, rifles for help, you'll kick like an eight gauge full choked." The grin came sourly though. "Besides, I'm a trader. I don't want to have to lose the good couple dozen rifles I've won to date. We'll play our own hand—yet a while."

But Hawkes remained full of optimism. "There'll be eleven of us. Eleven men with white leadership have won a province in Africa before now." But the precariousness of the empty wilderness injected its note. "If nothing stops our fellows from getting back."

That was one point on which King had no fears. "Not around here, nothing will. Not those boys, with what they've got on their mind."

Nothing did. Though darkness had come and King's pessimism about African mischance was crowding down on Hawkes before King said; "Ha! Hear 'em?"

All that Hawkes could hear was the hoarse snuffling of a brace of hyaenas.

"That'll be them." King said. "The brutes following along their flank, hoping for someone to drop dead." On the farther side of the hill, away from the scattered glows of the encampment, he built a small fire. And in another half hour dark forms emerged into its light.

"We would have been here sooner, Bwana," the Hottentot reported, "only that the lions were unexpectedly many and the game therefore few and far, and these great louts demanded meat for their running like empty baskets that have stood idle till the ants have eaten their bottom out. Six and twenty rifles, Bwana; not a one lost; only a porcupine had found one hiding place and eaten up three good cartridge belts."

Hawkes chuckled. "Twenty-six! I hadn't realized our sniping had got so many of 'em—I should say, your sniping, old man."

"It was a good running," said King. "There will be gifts for each man."

"It was nothing, Bwana," the long-legged Bukadi boasted. "When a man's belly is full, what is a little travel? We be ready to go as far again."

"That's good," King said dryly. "Come then and look the other side of this hill."

The men stumbled after King to where a view of the further plain showed pin points of fire. Angry growls came at the reminder of their shameful captivity.

"So have they always camped in their security. Whau! Let us fall upon them, Bwana, while they are fat with sleep."

King shook his head, slowly, regretfully. "Not that easy. Give 'em a chance, and those men can fight like devils. There's not enough of us to take that kind of a chance. But the crowd of us together can maybe spoil their beauty rest some."

Hawkes saw the immediate military value. "Those johnnies have slept in peace all these nights while we've been roosting in trees. We've never dared to make a thorn boma against beasts for fear they'd send out a scouting party and find it. A little of this night medicine ought to jolly well bring 'em to talk terms."

"Come ahead," King said shortly. "Keep together. Who straggles will be lion meat."

It was when they could distinguish dim forms amongst the fires that King halted his party. "One good thing, we know that the slave chain isn't being coddled by any fires." He gave his simple instructions to his men. "Shoot, drop immediately flat, and crawl two hundred yards. So, if they charge out into the darkness, we be somewhere else." And he grunted with a grim vindictiveness: "Show these jaspers something about night raids."

THE plan was as perfect as Faraq the Fatherless One's original raid and as

faultlessly executed. The fusillade that crashed out of the empty darkness

was answered by seconds of stunned silence; then came yells that were more

startled than fierce, and scattered shots stabbed vindictive tongues in the

vague direction of the darkness that was as empty as it had been before.

Those African askaris knew things about crawling through high grass

that Arabs could never understand. Bullets flew futilely over where the

raiders had been, and the raiders were belly flat and well away from

there.

Well and thoroughly away before King halted them again. Not much could be distinguished of the camp; fires still glowed, but no indolent forms were in their light.

"I don't know that this nets us any score," King said. "Maybe your two policemen can shoot in the dark, but my boys are spearmen; they couldn't hit a hill in broad daylight. But it's morale we're aiming at more than men. Ready, everybody? Shoot when I do, and away again."

Somebody must have hit something, for a shriek came that was more than just rage or fear. King laughed. Bullets came where he had been, but nobody showed a head. It takes a peculiar kind of courage for men to charge out into a blackness where guns might be waiting.

Round at the farther side of the water hole King called another halt for another volley. Hawkes was jubilant. "This is the technique, my boy. Nothing like night sniping to smash morale. I've seen even our own men raw and ragged after a night's persistent attention by Waziri tribesmen up in our Afghan frontier."

"It's too easy." King remained obstinately pessimistic. "You're talking about an organized army that can afford to lose a few hundred men. We can't afford to lose one. We're too blamed vulnerable. Anything happens to me, and what then?"

It was not complimentary, but Hawkes knew well enough that only King's craft and experience had put life into their amazing campaign. He said nothing. King grumbled on: "These Arabs aren't anybody's fool. Give 'em time to think, and they'll hatch out a devilish idea or two for reprisal."

A little later he was able to point to proof of his foreboding. It happened on the farther side of the water hole, out in the direction from where they had first fired into the camp. A chillingly brief and admonitory drama of the African night. Just three short sounds. The harsh, waugh, waugh, of a lion and a single hoarse shriek. That was all.

"What was it?" Hawkes whispered. "What happened there?"

King barked a short laugh. "Somebody hatched an idea that didn't work only because he didn't know Africa." He let the Hottentot translate the tragedy. "And how do you read that, little Apeling?"

Kaffa moaned the crooning noise of a frightened monkey. In itself it had an eerie sound, coming disembodied out of the blackness into which he merged. "I read it, Bwana, that a man crept out to lie in wait where we might return; but the lion found him first."

"A wahabi," Hawkes breathed. "I've seen 'em do it before."

"What's a wahabi?"

"These Mohammedan johnnies. Some fellow's rage will drive him fanatic and he'll take oath on his knife blade to go out and get an enemy or die."

"Well, that one died," King said. "But they'll be hatching other things. Ready, w'askari? Another volley and keep up the merry game. Yet let no fool become careless."

THE game might have gone on all through the deadly night, but that Faraq

the Fatherless, desperately gathering his wits in between the sporadic

volleys, proved King's contention that he was nobody's fool. A voice called

out from the blackness of the camp, where all fires had now been

smothered.

"Give ear, white men," it shouted. "Give ear and consider. We lie behind a barricade of iron and meat. A rope of slaves surrounds us. Chained two deep they sit. Shoot them, if you will. Those that die will still sit, wedged between their fellows." And another voice laughed like a devil assured of many souls.

"So!" It hissed from King. "That's one good one they've hatched. This was too easy to last. Nothing to do but get back to our hill before daylight. Let 'em catch us on the open plain, and we're cooked."

It was on their own safe hill that the next good idea hatched. They were almost at the summit, walking at their ease, when a rifle spat out of the darkness. King heard a smack beside him like mud spattering on a wall, a strangled grunt from Hawkes, whose dark bulk lurched up against him.

"Get him!" King roared. He snatched at Hawkes' sagging form. The other dark shapes were already roaring response and rushing forward. The rifle spat again. The ground thudded under racing naked feet. King lifted Hawkes and plowed on for the top. Beyond him the pack of fierce voices bayed on the quest, casting criss-cross over the hill's dome, till one yelled the find and all the others converged in chorus to be in on the kill. Blows thumped dully; steel-shod rifle butts clacked together in their eagerness; a voice yelled horribly above the roaring of furious men.

The Hottentot loomed close out of the dark. "The man is pulp, Bwana. What of the Bwana Policea?"

"A fire! Quick!" King ordered. "Below the brow, where they can't see it."

Hawkes' voice came, shaky but game. "Another wahabi, by gad. And that one got through."

King was cursing himself in a fury of profane self blame.

"Couldn't expect to—guess this one." Hawkes offered comfort.

"It's out-guessing the other fellow that keeps me alive in Africa," King said savagely. "Quick with that fire, Kaffa. Where are you hit?"

"Left shoulder. But I'll be—all right, old man. I've—stopped 'em before now."

The sputtering fire began to show up a smudge on Hawkes' coat.

"A knife, Kaffa!" King swore again. "Thank Pete we got this much." He sawed at the coat and the shirt beneath it. There was only one hole, and that was bad. An emergent hole on the other side, however torn, would have given King less anxiety. He made a pad of the material he had sawed out, yanked out his own shirt tail and ripped it to strips.

"You've stopped 'em," he said through tight bitten teeth, "where you've had a hospital corps behind you." He set to bandaging the pad in place with his ripped shirt tail.

"If those swine hadn't looted everything in my kit I could do an amateur job on you with the boys holding you down." He cursed the inadequacy of the shirt tail and tore out his shirt front. "Iodine, anyway. This isn't so easy. Not even a canteen of water nor a blasted thing to carry any in." He tied the crude bandage tight. "Stop bleeding, anyhow. There. We'll have to get you down to water. Means open plain in daylight—wide open to have 'em rush us. Hell! What a gaudy mess!"

Hawkes felt that he had to apologize. "Sorry, old man, and all that sort of thing."

King stalked back and forth, swearing. This smashed his every plan. His savage temper at the contumacy of Africa broke from him in explosive bursts. "I knew it. It was coming too easy. Now, by God, we're stymied."

Hawkes felt soldierly embarrassed.

"I'll be all right, old man," he insisted weakly.

King never believed in belittling danger just for the comfort it might offer.

"Don't fool yourself, feller. You'll be a lot worse before you'll be better. This is Africa. Heat, dirt, bugs—and not even a pellet of quinine. You can't fool with that sort of thing. I'll have to rush you in to where you can get some attention."

"Oh, but I say, old man!" Hawkes suddenly understood the reason for King's impotent fury. "You can't do that. Your Masai. They've still got him."

"Think I don't know it?" Helpless, King set to pacing the ground again. It was maddening, how far reaching could be the results of a simple wound where the ordinary aids of civilization were not at hand, how out of all proportion to its intrinsic damage. After a fury of pacing King stopped and looked down at Hawkes' dim form in long silence.

"Really, old fellow," Hawkes assured him, "I'm feeling quite chipper. I'll do all right till you get your man back."

King's voice softened.

"You've got your guts, soldier. But wait till the sun gets up tomorrow. Wait till it begins to inflame. Fever, festering, gangrene. I've seen 'em all happen."

"Perhaps," Hawkes said hopefully, "something will turn up tomorrow."

But his eyes were bleak.

BUT something did turn up in the morning. A man called excitedly from the

lip of the hill: "Men come from the camp, Bwana. Not for war. They

carry a flag of white cloth."

King snatched up his rifle and ran to look. From the top he called back to Hawkes, "Two of 'em. With a burnous tied on a pole."

"By Gad!" Hawkes was still well enough to get up and totter to see for himself. He was there before King, intent on the approaching figures, knew it. King growled at him.

"Pulling the old bulldog stuff, eh? Don't forget, soldier, every move you make will pile a degree onto your temperature."

"Gad!" was Hawkes' only response. "A flag of truce! I jolly well knew that last night would knock an awful hole in their morale. A delegation to talk terms, by Jove."

"Talk something, sure enough. But I see nothing to crow about yet." King's eyes narrowed on the two men; and as they came closer his eyes widened to stare.

It was no mere delegation; it was Ibn Faraq in person. Tall and darkly vindictive, he stood and stared at King, leaning on his long desert lance from which the dingy rag of burnous fluttered. His eyes, bloodshot with barely controlled rage, moved from King to the group of men behind him. Their fierce mutterings affected him not at all. His eyes passed on to rest on Hawkes. Their expression changed no whit from their scowl of hate. His lips moved, but his anger made his sonorous Arabic tremble. His fury at his own lack of control exploded from him in a harsh grunt that his interpreter understood.

"The Djeeb al Rais says," the man translated, "that he has made here the only mistake in all his career; that he has learned now many things about the Bwana Kingi. He believes that your word given is given and stands good."

"Surrender and asking terms," Hawkes said. "Don't grant any."

"Not that easy." King's morose frown of the last two days was giving place to the hard-mouthed grin that faced impending action. To the interpreter he said: "Ataka nini? So what?"

"He has learned that you set great store by the Masai; that you value him more than all these men who were returned free, and that therefore, rather than the peace that was offered, you risk further fight—and wounds." The interpreter's eyes dropped to Hawkes' shoulder.

"Ataka nini?"

"Therefore the chief says, if you will give your word to the bargain, he will fight you for the liberty of that one man against the liberty of all these men. If you win, your man is yours and your word will be to go in peace. If he wins, he takes these and goes in peace. Man to man, hand to hand, the chief offers to fight you for this stake as men fight."

"Oh, I say!" Hawkes ejaculated. "What I mean, that's a bit thick!"

King still grinned. "Why should I fight for what is mine to take?" And he bluffed. He pointed to the thin smoke columns in the far hills. "The Ras Woilo has my messages and is already on his way with at least a hundred men."

Ibn Faraq barked instructions.

"He says, 'I have observed, and therefore I come this early morning to offer this bargain.'"

King grinned and shrugged, and the Arab barked again.

"And he says, 'If the Bwana Kingi is afraid to fight for this stake that I offer as a man, to win or to lose, one thing at least is certain. By the Sacred Coffin I will surely slay that Masai before the Ras Woilo comes."

The grin jerked out of King's face. He stared under knit brows at the Arab. Faraq the Fatherless stared unblinkingly back. There was no doubt that he would carry out his threat. A captured slave meant only a certain money profit to him. King turned slowly and stared at his men behind him. They stared back like oxen, uneasy and silent, their eyes rolling white while they knew that King deliberated their fate. King's eyes dropped from them to Hawkes.

The Arab barked again behind him.

"He says," came the interpreter's voice, "'Only I do not want the white man. He may sit where he is, or he may crawl, or he may fly. His fate will be in the hands of Allah, who is sometimes merciful.'"

"Don't consider me in this thing, old chap," Hawkes said, as though talking about some sporting proposition.

KING scowled on into the ruthless responsibility that was being thrust

upon him. Lives hung on not only what he would decide to do, but how well he

could do it. He swung back to the interpreter, his shoulders hunched forward

as though he were already in a fight.

"Tell him, yes, I'm a whole lot afraid, and for a whole lot of things. And tell him that I can make no bargain for these men. They are free men, not slaves. But for myself, I will make a bargain. I will fight him for my Masai alone. If he wins and if he can thereafter take these men again, their fate is in their own hands."

A barely perceptible smile flicked across Ibn Faraq's face before his quick, growled acceptance.

"He says, 'I agree to that bargain. Provided that the fight is as men fight—man to man, with lance and knife.'"

"Good Lord!" Hawkes pulled himself to his feet. "Don't do it! Man, that's an awful chance to take. His own weapons, and—"

"Have I any other choice?" King snarled a question that needed no answer. "I've got to get you to a doctor, starting now—slung in a hammock on a bamboo pole. What kind of a chance would we have in open ground—with their merry turn to do the sniping?"

He swung back to glower at Ibn Faraq's complacent confidence.

"Tell him I'll call his play. Man to man, like he says. Only tell the devil I have learned nothing about him or his word but evil, and even if I trusted him I wouldn't trust his other devils. Therefore I add this to the bargain. Let him bring the Masai, alive and free, to stand as the stake for which we fight; and let him bring not more than ten of his men to watch the fight is fair; and I'll fight him for that stake, with any tool he likes—lance or knife or empty hands and teeth."

Ibn Faraq's saturnine smile came all the way out.

"Mas-Allah!" he exclaimed.

King knew that common Arabic expression. Praise be to God.

"He says," the interpreter added, "'I will be here within the half hour.'" Ibn Faraq smiled upon King once more and turned to go.

"And tell him," King shouted after them, "to bring a spear—the Masai's spear. I don't trust any weapon of his."

A silence came down on the hill like the silence that had gripped the slavers' camp when bullets came out of the night. Hawkes broke into it.

"Good Lord, man! You've allowed him the choice of his own weapons. The fellow is a lancer by his long training. You should have—"

"Swell chance I had of anything else. D'you know how many shells I got left? Just six!" There was a grim little joker there that King could suddenly laugh at. Now that the thing was done, the heady recklessness of men who are ready to fight settled on him, and with it came the bare-toothed grin of fighting men.

"You said it. He's a lancer, a soldier on a horse. He's got no horse here, and all that his weapon has is length. I've lived on my own two feet and kept out of the way of things for a long time."

"And you pretend you never take a chance." Hawkes could see no humor in any of it. "Crazy Yank!"

WELL within the half hour a cluster of figures emerged out of the shade around the water hole and headed for the hill. There was nothing hesitant about them, nor anything serious; they came, rather, as to an exhibition. The wind brought bursts of laughter that replied to jests.

"Pretty damn sure of things, huh?" King's eyes narrowed, as he saw a burly figure amongst them that was certainly no Arab.

The Hottentot hopped on alternate feet, but his little round eyes were as sad as a chimpanzee's looking out on the world's inexplicable mysteries. He pleaded pathetically, as for the boon of a banana.

"Bwana, the word of white men is a god that we do not understand. Let that god's anger be on me who have no gods. Give me but permission to shoot at him as he comes near. With six shots out of one of his own Jaipani rifles I might surely hit him before he could run out of range. Moreover, Bwana, how can one man give a word for another? I have given no word."

King laughed at him. "A fine casuist school you have studied, Implet." But his laugh turned ruefully to Hawkes. "Not the first time in Africa that silly civilized inhibitions leave the white man out on the limb."

Hawkes shifted his position on the ground and winced. "And that," he said grimly, "is the real white man's burden."

The Hottentot stared mournfully at them.

The gang came to a straggling halt. Boisterous, unruly, their open lips and wild eyes showed excitement, but no anxiety; they jostled each other and laughed at their own jokes.

"The bounder has brought the toughest ten of his gang," Hawkes said gloomily.

King laughed. "Figures to take nine of us back."

Only Faraq the Fatherless stood unsmiling amongst his men. His dark temperament, unlike a white man's, was settling down to surly rage for the vengeance to hand.

King's grin on him was ugly. "The bargain was that the Masai should stand free as the stake for this fight."

Ibn Faraq lifted one satanic eyebrow to his interpreter. The gang opened up. A man cut the ropes that were biting into the Masai's arms.

"The man is a mad bull," the interpreter said.

The Masai dropped to his knees before King and put his great arms round King's thighs; he bent his forehead to touch his master's waist. King could see on his naked back the raised welts, as thick as a finger, of hippo hide whips. The Masai's voice vibrated deep.

"Do not do this thing for me, Bwana. The man is a spearman and has a devil besides; and what does Bwana know of spear play or of devils?"

King put his hand on the big fellow's shoulder. His voice was unnecessarily rough.

"Up, old warrior! Have we not seen blood together before now? And what insult is this? Have I not seen enough of your spear play to have learned something?"

"Aie, Bwana! But it was much blood of other people and little of ours." The Masai straightened up and worked his big shoulders, tentatively, as though uncertain whether they were free. "Hau, Bwana! I breathe the first whole man's breath in many days." His submissiveness became the fiercely eager challenge of an Elmoran who has had the hot bravado to go out alone with shield and spear and slay his lion.

"Bwana, make another bargain with this Fatherless One. Let me but put haft to my spear and let me fight this hunter of men and his ten while Bwana stands free and applauds the slaughter."

The man stood superb in the sun, black as old iron, his great muscles throwing blacker shadows on his naked skin. King shrugged wryly. "Barounggo, old Blood-Letter, I'm afraid this clever Arab thinks he has a better bargain than that."

"Then, Bwana, if he will be afraid of such an offer, let him take me and go in peace to his own country, according to his own offer. I will yet escape and devastate the land."

What King did was a very undignified thing for a white man in Africa. He reached his hand to grip the Masai's shoulder and give it a little shake. But he spoke to him as an African can understand.

"Braggart," he derided. "Must we listen to your boastings all day? Go rather and cut a straight branch to fit your spear—not too long, and heavy in the butt, as who knows better than yourself. Go swiftly, for the Bwana Policea's wound must not sit in the sun."

FARAQ the Fatherless stood and scowled through all this delay. His face

was masked black with hate. King grinned hardily back at him.

It began to be apparent that the white man's cheerful recklessness was more disconcerting than the Arab's ferocious scowl. The boisterous confidence of Faraq's lowers began to ebb from them; their faces darkened and their loud voices fell to low mutterings. On the other hand, King's askaris began to grin sheepishly.

"Kefule!" the lanky Bukadi suddenly guffawed aloud. "What has been this fear of ours? Barounggo is here and the Bwana is here. It is well. Let us sit and watch."

The Hottentot shrilled at them. "And forget not that I, too, am here. Oxen that ye be without the wit of the lice in your heads. Wisdom it is and not brawn that accounts for any of you being here at all."

"When the monkey is contented," Bukadi said, "the leopard must indeed have lost his claws." The men hunkered down, as callously content as for a cock fight.

The Masai came back. His great three feet of spear blade was fitted to a stout pole, peeled white, barely longer than the blade itself. He balanced it critically in his hand. His dark face seemed to be satisfied, but he had a complaint.

"A fair balance, Bwana, and with a good weight to push the stab home. But the steel spike for the butt end was lost by these desert baboons, who know not what makes a good spear."

King took and hefted the thing. It must have weighed all of seven or eight pounds. "The hell with an iron spike." He spoke more to himself than to the Masai. "A good thick butt with honest weight to it would suit me all the better." He turned to grin, hard eyed, at Ibn Faraq.

"All right, guy," he said in English. "Man to man it is."

It came to Hawkes suddenly that he had been thinking that the Masai's savage menace was something stupendous as he shouted his challenge. But he saw King now as physically hard and as grimly competent a fighting man as all his military experience had ever known.

King remembered a last detail. "All men stand back twenty paces, and the agreement is that no man interferes."

"By Jove, I'll see to that—Kaffa, bring me a rifle." Hawkes pushed himself to a sitting position. "I can shoot one-handed at this range. I'll dashed well see that nobody interferes."

Ibn Faraq threw off his burnous. He was every bit as tall as King, a lean, stringy man. With his long lance he could outreach King by a good half length.

The Masai gave soft advice.

"The body sways inside of the foolish point, Bwana, and the Masai blade then slashes up from groin to chin."

Ibn Faraq didn't grin, but his eyes contrived to glitter through his scowl. He held his lance as a horse lancer should, under his right arm.

"Aa-ah!" It rasped from King. "That's what I'd hoped." He held the Masai spear as Barounggo never in his life did—with both hands wide apart, slanted across his body.

Hawkes let out a whoop. "I knew it! The bayonet stance, by Jove! I knew you must have been a soldier!"

IBN FARAQ showed a surprising agility in a sudden leap forward and a

vicious thrust, swift and straight at King's chest. The neck of his lance

clicked against King's haft, between his widespread hands, and slid past.

"Now!" Barounggo roared. "Now to rush in and rip the bowels from him."

But King was not quite familiar enough with the weapon to have been that fast. He circled warily on light feet, suddenly enormously confident in his ability to fend off a savage point by the method evolved by white men, even though the instrument was not precisely a white man's. He grinned out of the corner of his mouth toward Hawkes.

"Wrong, buddy. Never a soldier, but—" He fended another furious thrust, and this time lunged full arm with his point. It fell just short of the Arab's throat. "Hell! Another couple inches and I'd 'a' nailed him." He found time to flash a look at Hawkes.

"—But I've played around with soldiers here and there, and some of 'em pretty near persuaded me that a bayonet was better'n a spear—Ha!" He clicked aside a long thrust. "Overreach that way again, and I get you."

He was out of reach, cat-footing round for an opening. "Met some good men amongst soldiers—even Britishers."

Ibn Faraq's rage at the unexpected resistance to what he had counted a sure thing exploded in incoherent blasts of speech.

The interpreter's voice was shaky with apprehension. "He says, men talk less and fight more."

King deliberately grinned at the man's fury. Ibn Faraq replied with the worst insult he knew. He spat at King's face. Truer than his furious spear thrusts, it got home. King's eyes blinked. Faraq shouted and drove with all his weight and reach for King's body.

By a miracle of luck King was able to sway inside of the point before the lance rattled along his defending haft. King grunted with effort as he swung the butt up and forward. It crunched full onto Faraq's mouth.

Had it been a rifle butt, it would have smashed the man's face in. As it was, Faraq this time spat teeth.

His men clapped their hands to their own mouths in their racial gesture of astound. Howls of delight came from the askaris. Barounggo roared advice. King could distinguish out of the uproar only Hawkes' restrained and distinctive, "Go-oo-od shot, old man."

Ibn Faraq's rage, while it hampered his thinking, did not deprive him of the ingrained technique of spear and knife. King, of course, had given no further thought to the knife provision of the terms of this duel; but Faraq's dagger was in his sash. With his left hand he drew it and held it flat along his palm.

The Hottentot's shrill yelp came. "Similia jumbia, Bwana! He is a thrower!"

AND at that moment Faraq saw his chance and threw, a swift underhand fling

for the belly. King, cat-footed, was able to snatch his stomach aside, but it

left him hideously off balance. Faraq roared triumph and lunged full length.

The lance point flicked through King's leather belt like through wet paper.

King felt a searing fire streak along his ribs; in a fractional second that

lasted a year he felt the point push through his skin again somewhere farther

back and felt wood rasp along bone.

Faraq roared again and lurched forward, his spear in both hands, shoving it on and grunting with the effort of each heave.

King's hands on his spear were all wrong for any kind of a thrust at the oncoming enemy. They had slipped together at the neck of the blade; the haft hung in his hands like a club.

He used it like a club. As Faraq lurched in, he swung it in a desperate arc. It cracked hard over Faraq's ear.

Faraq staggered and went down. But he still held his lance; lying prone as he was on his back, he tugged to free it. Its very length impeded its withdrawal; but the leverage of it, fast through King's clothing and side, twisted King excruciatingly this way and that.

Until suddenly Faraq's own struggles twisted King directly alongside of himself. King heaved up his spear with both hands and drove down at him. The great blade slipped through his chest and back and two feet into the ground beyond.

Faraq's last fury croaked from his throat in great strangled heaves. Impaled like a noxious beetle on a pin, his arms and legs flung out in spasmodic jerks and his back arched mightily to free itself from the earth to which it was nailed. Then blood began slowly to push out around the blade.

"Whau!" The Masai's great shout broke the silence. His askaris leaped forward, solicitous all together to support King. Hawkes, who should have been lying down, was with them, pawing at King with both hands, one of which ought to have been in a sling.

King pushed them testily from him. "What the hell! Stand off, you gorillas! It's only through the skin—I think." He tried to break out of the press, but the lance, grotesquely horizontal in his side, held him as in a yoke. "Get this blasted thing out." He tugged at it himself, but pressure of skin and clothing held it hideously fast.

"Away, cattle! Away!" Barounggo knew much about spears and their handling. "A spear through meat is no new thing. A knife here!" Like sharpening a giant pencil, he cut through the shaft. "Hold fast, Bwana. Just while a man may wink one eye." He gave a jerk. It twisted King agonizingly around. He was not ashamed to yell. But the thing was out.

Barounggo ran the knife through coat and shirt and kneeled to peer through the flap. With expert callousness he poked an unsanitary thumb at the bleeding gash in King's side and followed the ribs around to the other hole eight inches farther back.

"Skin and some meat," he announced. "It is nothing. It bleeds. We have seen blood before, Bwana. It was a good fight, though shamefully inexpert. I must give Bwana some lessons with the spear."

King was aware of Faraq's ten picked ruffians slowly moving away. They went backward, their eyes bulging at the incredible things that were happening. Barounggo's great arm was around King, offering support. King pushed from him. Those men must not see any weakness.