RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

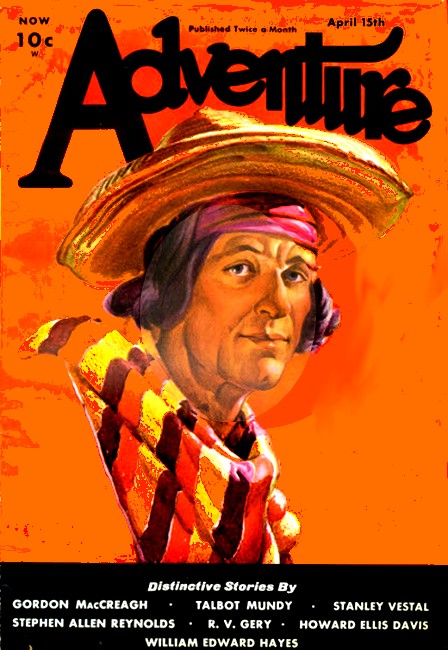

Adventure, April 15, 1933, with first part of "Strangers of the Amulet"

KING stood teetering slowly on his widespread legs, his thumbs hooked in his broad pythonskin belt. He frowned ruminatively down at the man who sat expectantly at the table with a heavy gold banded fountain pen poised over an open checkbook.

The difference between the two men equalled all the disparity between the tropics and the north pole. One was tall, angular, lean with the long drawn toughness of a strenuous life, burned to mahogany brown and dressed in the shirt, breeches and high boots of the African outdoors. The other was slight, anything but strong, gray at the temples, dressed even in Kisumu—less than one degree from the equator—in the meticulous City of London business garb of one to whom correct clothing was synonymous with ordinary decency.

The Londoner waited to sign away money. But King hesitated, looking, narrow eyed, through checkbook, table and floor into the deep hidden possibilities of something he did not know. The abstract frown focused upon a concrete annoyance and deepened to a scowl. As he teetered thoughtfully on his long legs one of his new looking boots creaked ever so faintly. King threw his weight upon it and worked his ankle.

"Durned thing screeches like a Hottentot cartwheel. Anything in the whole wide veld could hear it a mile. And those noises are the devil to locate and oil out."

The squeak of the shoe was of more immediate importance than the checkbook. King's attention came back to the suggestive weave of the fountain pen top. His frown was one of discontent.

"I don't like your proposition, Mr. Smythe. I hate to jump off into what I don't know."

Smythe tried out his pen point on the edge of a check stub, shrugged slightly and smiled as one who knew his ground, saying—

"I have been told different about Kingi Bwana—quite a lot different."

A faint gleam came into King's eyes, and the frown lightened almost to a grin.

Smythe pushed his argument with calculated persuasion:

"I am a business man, Mr. King. My proposition is quite definite. I want you to go to a certain place and fetch me a report of conditions in that place. All I insist upon is secrecy. If your report proves what I hope it will prove, there will be money enough involved for business rivals to go to any lengths in order to get that information. Secrecy is therefore imperative."

The grin that had been struggling against King's frown split his face like a crack in hard wood. He looked down at the other man in slow amusement.

"In Africa, Mr. Hamilton Smythe, there are no secrets."

"This one is." Mr. Hamilton Smythe snapped out his conviction, as if annoyed at the other's obvious innuendo against his lack of business acumen. He continued persuasively, "And I don't mind telling you that if you make good on this thing, your future with my firm is assured." The gold banded fountain pen executed preliminary curlicues over the checkbook."Name your own figure, Mr. King."

King grunted. He had made his decision.

"I'm not looking for a future with anybody's firm, I don't care how assured it is—but I'm broke enough to deal with you. My terms are flat expenses and a fat bonus if I deliver the goods. Nothing if I fail. But I make one condition. I have a little obligation of my own to settle—a long standing promise to a friend. If your affair doesn't interfere with that, I'm your man."

This was a most cavalier manner of accepting a job in which so much money was involved that other people would go to any lengths to find out about it. But the financier was the more anxious of the two. He bit back his annoyance and shrugged agreement.

"All right. Your private affairs can not interfere with my project. I make a condition too—that you leave at once with my sealed instructions; and I take your promise that you will not open them until you are a week out on the Karamojo trail. Now—how soon, and how much?"

King made three long steps to the door.

"If I hustle I can get out of here by tomorrow night. And you don't want all Kisumu to know that I cashed a check of yours. I'll send you a boy, a Hottentot who looks like a dried monkey. His name is Kaffa. Give him a sealed bag containing cash. About five hundred sterling will be enough."

The door closed behind him and only the faint creak of that new boot advertised his every second stride down the passage.

Another door opened silently and a man entered. He and Smythe looked at each other questioningly. The newcomer was pleased.

"Well, you landed him."

The financier voiced exasperation.

"So it seems. But I'll tell you, Jim, if you hadn't been so insistent about recommending him as being about the only man in East Africa who could do it and who wouldn't doublecross us, I would have sent him packing. I never heard such independence; and what kind of arrangement is that! Nothing on paper, no contract; and I'm to give five hundred gold cash to some African boy. All on a loose say-so as he slid out of the door."

The other nodded.

"A square dealer is worth all of that, my business friend."

The financier snorted.

"Well, I suppose we've got to trust him. And in any case he couldn't develop it without finances, and he might as well come to us as to anybody. There's a certain safeguard in that."

The other man nodded again.

"All you've got to worry about now is whether anybody else has got on to your secret."

"Never." The financier was positive."Not a chance of that, I'm certain. This thing is a closed secret; the one man who found the key to it is dead."

The other laughed crookedly.

"There's a saying in Africa—" he began; but the financier cut him short, angrily.

"Yes, yes, I know it already. There are no secrets in Africa. But this one will prove the rule. I tell you nobody has ever been up into that country. It's unknown. The only surveys are aero maps."

The tall man nodded thoughtfully.

"I rather wish you had told him there was a chance of native trouble. Those people up there seem to be quite untrained to any knowledge of machine gun retribution for white man killing."

The financier was positive again.

"Not for a minute. He would have wanted to take a fighting party along; and that would immediately double or treble the chance of one of them selling out on us. If he is the man you say, he'll fight through. And why would I give him so much money if it isn't to pay for taking his chances? If he doesn't get through the secret will still be there, and we can try again with another party, being only five hundred pounds to the bad."

"He'll get through," the tall man said with assurance, "and you'll get your report, or your money back. He's a quixotic fool. He didn't even stipulate the size of his bonus, did he?"

And at that supreme lack of business acumen both men laughed.

THE following day for King had every right to be a considerably busy twelve

hours. Just now his legs and his left arm formed a long tripod over the quite

inadequate table in his stuffy hotel room, and he frowned over a map while he

drew wandering, tentative lines upon its surface in a general northward

direction.

The room was stuffy because Kisumu at that season on the equator was not the coolest place in Africa, and the Jew had insisted upon closing the window that opened on to the wide, screened veranda. King grumbled about the heat. But the Jew, who had been watching the progress of the wavering lines with the intentness of a discontented bird, shrugged his shoulders up to his ears while his heavy eyebrows disappeared into his tangle of hair.

"My good simple Kingi, I tell you again you are a child in matters of business. That Kingi Bwana should want to trek into the far middle of nowhere is nothing; all men know that he is loose footed and harebrained. But if a whisper should go abroad that Kingi Bwana and Yakoub ben Abrahm, the trader, were preparing a safari together—oho, that would be altogether another kind of a talk. Fifty people would prick up their ears; and ten of the worst of them would immediately get ready to trail behind."

"Well, it will be plenty trail," grunted King."A good six weeks of hard going."

The Jew's ears and brows disappeared again.

"Six weeks, yes, if this new silly thing that you have tangled yourself up with doesn't take us another six out of our way."

King was immediately apologetic.

"Gosh, Yakoub, old friend, I know you've been patient. I'm ashamed to take on the job. I've been promising you this trip for a couple of years now. But be reasonable. I told him I'd take up his proposition only if it didn't interfere with my long standing promise to you. And he wants me to go by Karamojo; that's pretty near halfway in our direction. And this thing pays half our safari expenses; and when we're both so flat broke that's more than a little reason, it seems to me."

It was the last item that reconciled Yakoub, though he threw out his hands in querulous complaint.

"Reasons, reasons, you have always reasons for all the profitless things that you do. Even if it is no better than that your friend, the commissioner, asks you to go and smooth over some silly native trouble for which the government pays you no money."

King was immediately serious.

"That's a long and a deep matter, friend Yakoub. It goes all the way into the white man's future in Africa; into the coming time when he can no longer hold the black millions by machine guns but only by the careful and consistent policy of the square deal. The white man's burden, my grouchy cynic. That's not a sentiment; it's a religion."

"Your religion, maybe; not mine." The Jew's brows disappeared and his nose came down over his lips in a smile of unalloyed satire."My religion, my dear Kingi, is business. And now that we are at last partners in a business, you and I, I tell you you will not need to worry about the future of the white man in Africa. If those little ingots are any indication and if your witch doctor can show you how to find this so mysterious place, there will be money enough for you to go home and buy that ranch in your wild and woolly Yankeeland. Money, I tell you—"

A crisp knocking low at the base of the door interrupted. King knew it to be the battered silver toe ring of his Hottentot, and he called—

"Ai!"

The man came in, huddled even in that tropic temperature in a blanket of brilliant red and orange stripes. Swathed in all that cloth, he looked smaller than he really was, shrunken, a veritable ape with all the wisdom of the ages peering out of the bright black eyes in his wizened face.

"The talk was of much money," he said softly."It could be heard without the door."

He made a simple statement, implying nothing, suggesting nothing. But King looked accusingly at the Jew, and the Jew amazedly at the little Hottentot. He combed sensitive fingers through his beard and nodded in thoughtful appreciation.

"Yes, I was talking too loud. But how did that little devil know that we didn't want to be heard?"

"Much money is here," said the Hottentot. He produced a strong canvas bag, like those used by banks, from under his blanket and laid it on the table."Five hundred pieces of Inglesi gold."

King's only movement was that of his eyes, which flashed to the bag and its seal.

"And how, wickedest apeling, did you satisfy your curiosity so surely?" he asked quietly.

Under his master's accurate diagnosis of his motive, the Hottentot squirmed; but he twisted the myriad wrinkles of his face into an expression of sententious virtue.

"Bwana told me only to fetch a bag that would contain money. That other bwana who is rich made so much talk about giving the bag into my keeping that I knew it must be much money. How can a man take proper precaution about carrying much money if he does not know how much? So I took the bag to Abdul Huq, the Banyan money lender, who knows all things about all the moneys; and he, by the sound and feel, said it was gold, and by weighing the bag he knew the pieces would be five hundred."

The Jew nodded in Mephistophelian delight.

"A good lad, a smart lad. And I suppose there is no man in Africa but Kingi Bwana who has a servant who would not run away with all that money and become chief of his tribe. How is that miracle done, my Kingi? I, who handle money—alas, only sometimes—must know that recipe."

"The square deal," said King shortly; then to the Hottentot with severity, "And how, O most foolish apeling, did you think that the Banyan would not contrive to rob you of so much money?"

"Nay, bwana." The Hottentot was confident."Barounggo stood beside me like the father of death anxious to strike, and the Banyan trembled so that he with difficulty weighed the bag."

A grim little smile played about King's mouth. He could visualize that money lender under the shadow of his great Masai spearman.

"It was well done, O wise apeling. There will be tobacco for both. Tell Barounggo that we go out this night—secretly. Let all be ready."

"Nidio, bwana. All will be ready."

King turned again to the Jew, his eyes twinkling.

"The recipe works, my friend, eh? Even in Africa—sometimes. Come along to Koomer Ali's to lay in some trade goods; I guess your just being along won't stir up ten bad amen to follow us."

KING put on a heavy pith helmet and led the way to an oven-hot section of the

town where the streets were narrow and dusty and the house fronts were

whitewashed with lime. An odd mixture of half the races of the East moved

listlessly in this African setting. Natives of India predominated; noisy,

chattering Zanzibar Arabs, negroid of feature and truculent; Chinese, of

course, and halfbreed brats who contrived somehow to survive, hatless, in the

vertical sun rays.

The trade store of Koomer Ali the Banyan was a rambling half block of ground floor filled with a litter of all the gimcrackery that might delight any savage heart. For the discriminating buyer there were stocks of better goods. Like an old fashioned country store, it was a meeting place for half the upcountry outfitters of East Africa. Among the loungers a group of three were looking over trade goods with a carelessness so studious that King whispered to his companion:

"They quit talking the minute we passed under the window. It seems that Yakoub the trader can't go shopping without at least three of the worst men in British East sitting up and taking notice."

One of the men was an old-time Africander who had hunted and traded his way from the Cape to Cairo, doing anything and everything. A big, capable looking fellow he was; his name, Van Vliet, suggested Boer extraction. There was some story about his having skipped from the Rand on account of a shortage in the sluice box returns of one of the gold mines down there. But that story was whispered only when Van Vliet was somewhere else.

He had come up into East Africa and had disappeared after a time under suspicion of selling liquor to the natives. The local police had utterly failed to get any direct evidence, and the district commissioner had employed King to make the suspicion a certainty. It was then that the man had skipped. Now he was back again, cool and confident.

One of his companions was a refugee from Portuguese East Africa. King knew him too. Dago Lopez he was called, and he had a reputation for an ungovernable temper and a lightning skill at throwing a thin, heavy bladed knife—which was why he was not just now in Portuguese East. A fit companion for any desperate venture, if he could be controlled. And Van Vliet was quite competent to do that. The other man was a stranger—a thick, wide shouldered man with a battered face and the shapeless ears of a not very skilful pugilist.

The other loungers in the store conversed in low tones, pretending to be at ease. Not that Van Vliet was a brawler, a senseless trouble seeker; he was much too calm and collected for that. The condition was no more than a certain unease in the air, the sort of tension one might expect around some celebrated gang leader when any startling thing might happen at any moment.

But Van Vliet was in a good humor. His bold eyes roved over the room without any hostility; the corners of his mouth, just visible above a curly brown beard, worn untrimmed in Boer fashion, were turned up in a smile of mild contempt at the discomfort he knew he inspired.

King, immersed in a meticulous testing of trade cloths, paid no attention to the three who were the center of attention. To him it was more important to select a good grade of honest materials rather than the showy, shoddy kind for native trade.

Van Vliet laughed sardonically at a meticulousness so different from his own methods and raided his voice.

"Too much trouble, Yank. Altogether too much trouble. Take it from my experience; instead of so much fuss over quality like an old wife, give 'em lots of cheap color and a flask of square-face to close the deal."

The remark in itself was not particularly offensive; but it drew more than the intended rise from King.

"You know damn well I don't sell liquor to natives," he snapped. The emphasis was all on the I and the inference might be taken as anybody wished.

Van Vliet only laughed and shrugged noncommittally. His good humor, as he conceived it, held good. But his thickset companion took up the innuendo with a heat even more surprising than King's.

"Oho, what is this? A blinkin' missionary, what? A long nose? Mebbe yer'd like ter preach us a bit about niggers an' whisky?"

King gave him no more than a glance. His eyes were directed coldly and narrowly at Van Vliet while he ostensibly answered the other man's challenge:

"I'll preach you this much, my bucko. It's a pretty poor sort of white man who'll swindle a naked African over a piece of cloth; and it's a worse one who'll sell him liquor. And both of those mean a whole lot more than you'll ever understand."

Van Vliet only laughed in easy amusement. But the other man took the whole insult upon himself. He ripped out a short epithet of just two staccato syllables, snarled a broken toothed grin of confident pugnacity and commenced to sidle in, soft footed. Thin flanked and heavy shouldered, his wary poise and the quick, shifting little eyes in his battered face were evidence that he was no amateur at argument.

King moved only his feet; spread them a little farther apart and shuffled them gently to feel the floor under his boot soles. That was all.

The whole altercation was so sudden, arising out of nothing, that the storekeeper and the other men stood appalled.

Van Vliet's voice rose in unhurried warning—

"Look out, Johan, you can't take chances with Yankee King."

The man hesitated. The name conveyed an impression which he misunderstood.

"Oh. Oh, indeed. A Yankee gunfighter, yes?"

King stood very still. Only the elbow that had been leaning on the counter lifted clear; the other hand still held the cloth he had been examining.

The man clung to his delusion. It seemed to him that King was in a most unfavorable position to reach for a weapon. His own advantage was clear.

"Well, crummy—" he grinned wolfishly—"if he fights a gun, I'll oblige 'im."

His hand tugged at his hip pocket. The slowest gun-fighter in the world could have drawn and fired while the man still fumbled. But King never carried a weapon within the purlieus of any law-abiding British colonial town. His eyes gaged the distance between them, his legs gathered under him for a dive at the man's feet. And then in the same moment Van Vliet became an astonishing tornado of action.

"You blasted fool!"

His voice roared its fury while he was still in the midst of his leap. His hand closed over his henchman's fumbling fist. With one great wrench he tore fist and pocket and gun out all together. The same movement carried that arm over his shoulder; he slipped his hip under the man's body and whirled him cartwheeling off his feet to crash on the floor. The impetus of the flying body slid it to the very threshold of the door.

The whole extraordinary episode was over as suddenly as it had begun. Van Vliet stood smiling sardonically at the awestruck onlookers. He slipped the confiscated gun into his pocket and his smile broadened to a grin of pure bravado. He nodded curtly to King.

"I'll be seein' you, Yank," he said and swung out to the door."Come along, Lopez. Lug that fool out."

KING looked after the trio with amazement and a slow, dawning relief; but his

expression was mostly of the former.

"Now what in thunder did all that mean?" he asked aloud. Then his astonishment culminated in a shout. For Yakoub, the peaceful trader, was quickly wrapping up a shiny little black automatic in a silk handkerchief and stowing it in an inside breast pocket.

"Shooting," said the Jew, "in these so lawful British towns is more dangerous than not shooting. Still, the need looked to be desperate."

King dropped a hand momentarily on his shoulder. Then he cackled a short laugh.

"For a would-be gunman, my good Yakoub, your holster arrangements are as bad as friend Johan's. I'll have to show you sometime." His mind went to the mystery of Van Vliet."Why, do you think, didn't he want trouble? I mean, why didn't he want trouble just then?" King cogitated the matter, narrow eyed."He's tried it himself before now. I wonder. He's nobody's fool, is Van Vliet. Used to work for the DeWet outfit down in the Rand. Three hard hombres, those. Wonder if they're peddling liquor back country again?" Eyes and mouth hardened."That'll mean hell breaking loose somewhere. By golly, I ought to crab that beastly game."

But Yakoub threw his arms round King.

"No, you don't. Not this time. You don't push your nose into other people's trouble. You belong to me, my imbecile Kingi. I have your promise. We have a business together. Money is our object, not white man's burdens."

King stood irresolute. Then he grinned down at Yakoub.

"Damn my old promise. But it's been on my chest too long. And—" he laughed a hard little laugh—"me too, I'll do anything for money these lean days. I'll make my promise good to you as straight and as fast as the trails between the water holes will let me—if there are any trails up there, or any water holes. Nobody I've ever met could tell me. You're starting on considerable safari tonight, friend Yakoub. Come along; there's plenty to do before we melt out of this burg."

SUCH a plenty there was to do that it was going to be a miracle of swift

organization if they could get away by nightfall; almost as great a miracle

as "melting out" of a small frontier town where a dozen astute people were

furtively watching for a safari start.

Kaffa the Hottentot came and stood on one leg while he scratched the inside of his knee with the toes of the other foot. King knew by that hesitant attitude that something more than direct statement was on his mind.

"Bwana, there is a boy," began the Hottentot, looking all round the room with the faraway disinterest of a monkey trained to do an act, "a Basuto boy from Pemba's kraal near the Witwaters Rand. He is a big boy and strong and his name is Umfoli."

King knew that this was circumlocution. There was something behind all that preamble; and he knew that it would come out sometime. He only grunted disinterestedly.

"He is a very clever boy, bwana. He understands the Inglesi tongue; and his master, who knows no other tongue, pays him very much money therefore. Twice as much as my pay. If I knew the Inglesi I would be worth—"

King fixed the crafty little imp with a steady stare; and the imp quickly glossed over that line of suggestion with something of real interest.

"That boy is the servant of the evil white man who would have fought with a pistol in the shop of Koomer Ali the Banyan."

King grunted again.

"Hmh, it didn't take that one long to get abroad."

Yakoub nodded sagely.

"No secrets in Africa, my Kingi. Except—" he smiled with smug satisfaction—"the secret of our little business together."

"That boy—" the Hottentot looked directly at King for the first time—"that Umfoli heard his master talking with the other more evil white man. The talk was that the more evil one would come tomorrow to bwana to make an indaba about sharing in the business that bwana has with Yakoub Bwana."

"Adonai!" Yakoub jerked galvanically straight in his chair, his eyes staring, clawing at his beard.

A straight vertical cleft in King's forehead formed a T-square with his brows. His eyes looked through the Hottentot and beyond. He muttered questions half to himself, half for Yakoub to hear.

"Just how much does he know, I wonder? He's got his nerve, all right. I'll bet he's working a bluff on his guess that we're together. Hell, he can't know anything. We're going on the barest hint ourselves."

"Yes, bwana," said the Hottentot innocently, "he can not know anything. Even I do not know bwana's business."

Both King and Yakoub were moved out of their concern at this disclosure to shout with laughter at the cunning little Hottentot's betrayal in one breath of his perfect understanding of English as well as of his inordinate curiosity. Kaffa writhed in abashment and quickly covered up again.

"That boy, bwana, that Umfoli wanted to leave his master who is evil and desired to take service with bwana. And a boy who understands the Inglesi, as has been shown, is very useful."

"Has he any more information?" King wanted to know.

"Nay, bwana." The Hottentot screwed his face into a maze of disdainful wrinkles and clucked a noise of derision."He is but a Basuto. What knowledge he had is now mine. Only, since he knows the Inglesi—"

"Then chase him," snapped King.

"Yes, bwana." The Hottentot screwed his face into another pattern of wrinkles and chittered like a monkey that is being tickled."It was known to me that bwana would so order about a Basuto; so I had Barounggo beat him and hunt him from the door this hour gone. But, as has been shown, bwana, a servant who understands the Inglesi is most useful and—"

So then King knew what had been the basic motive underlying all this long story. Very gravely he reached for a scrap of paper and fished a pencil stub from his pocket.

"Tell Barounggo," he said as he scribbled, "to make ready for immediate departure with his men. And to you I will give a letter of recommendation, a very good letter, to take to that white man who has need of servants who understand the Inglesi."

The Hottentot's eyes became saucerlike as those of a nocturnal lemur, and he wailed the lost-soul noise of one and fled.

King turned back to Yakoub.

"That man had his nerve all right." He meant Van Vliet."We've surely got to melt out tonight."

So that night Kingi Bwana and Yakoub ben Abrahm the trader, the furtively watched pair, performed the miracle of melting out of Kisumu town on safari.

King's little ruse had the virtue of simplicity; and, since nobody had ever done it before, of novelty. No one had ever done it before because no one had ever had African servants who could be trusted to carry out a quite responsible job without the supervision of a white man. King and Yakoub alone, with only shotguns under their arms, strolled out with the sunset in the direction of the big western donga where guinea fowl might be found scratching in the slanting sun rays, or perhaps parrot pigeons in the umbrella acacia tops.

Nobody could go out on safari with shotguns and nothing else. So nobody followed the two pot hunters. King and Yakoub therefore trudged quietly on.

The slanting rays dropped horizontal, shooting mile-long sword blades of fire along the grass. They hung so for shimmering minutes, as if resting on the parched herbage, then they tilted suddenly, pale searchlight beams against the already graying East, and as suddenly were gone. Yellow grass, brown ant-hills and dusty green acacias absorbed the gray sky, drank it up and blended with it. They were all at once black shadows. Stars punched glittering holes in the black blanket above. The astonishing equatorial night was upon the two men.

They trudged quietly on. There would be no lions so close to Kisumu. Jackals and gaunt, striped hyenas were the largest beasts likely to be met. A leopard, possibly; but a leopard would probably be prowling closer to the hut fringe of the town, hoping to lure a frenzied dog just a little bit farther out than its more cautious fellows and snatch it before the rest could join the attack. The open veld was before the lone white men.

Fifteen miles farther on a ghostly tangle of orange glowed in the sky, resolving itself into the under side of acacia branches illumined by a fire as yet hidden in the tall grass.

King whistled the phwee-ee piu-piu-piu of the little banded plover. Immediately dark forms rose up in the glow. A tall shape strode toward them. Red light flickered on the outlines of a great naked figure and glinted from the blade of an immense spear.

"Jambo, bwana," boomed the figure."All is well?"

"Ha, Barounggo. It is well. And here? Everything all right? All the men?"

"Assuredly, bwana. How else would it be?"

The little Hottentot came running, querulous, complaining.

"Awo, bwana, it is late. We thought that a lion—that is to say, a leopard perhaps, or some ill spirit hunting by night had— All is ready, bwana. The tents are set and the coffee is waiting."

AFTER the toilsome night a lazy morning would have been excusable; and under

his usual conditions of lone travel King might have been tempted to linger.

For he had long ago reduced safari needs to the irreducible minimum. But on

this trip he was tied down to the speed of his slowest man. He was up at an

uncomfortably early hour to inspect by daylight his goods and gear and the

men who had started out on safari without his personal supervision.

First the packs. Every one was opened and its contents laid out in a pile beside its canvas wrapping. Nothing was missing, and the mathematical nicety of the weight distribution was a tribute to the organizer. King only nodded, without saying a word. But Kaffa the Hottentot, who had been waiting for that nod like a dog watching for commendation of its trick, grinned all over his shrunken face.

Then the men. Barounggo marshaled them in line—ten of them. He himself stood, a great monument of ebony nakedness, not covered so much as ornamented with a short leopardskin loin-wrapping and with monkey hair garters at his knees and elbows and his single black ostrich plume nodding over his head. His long Masai spear stuck upright on its butt spike in front of him.

He dwarfed the other ten, though they were no collection of thin limbed porters. Shenzies they might have been by heredity and occupation, bearers of burdens upon their heads. But they stood forth now as spearmen—askaris.

They constituted King's careful precaution in jumping off into country he did not know; and in themselves they constituted a minor miracle of manipulation with native habit and tradition. Shenzies existed in plenty for safari portage; and askaris for the purpose of guarding those Shenzies; but it had been Barounggo's labor for weeks to select and train a little troop who, having been graduated to the dignity of shield and spear, would still condescend to carry burdens. The ten were Barounggo's pride and joy of achievement and he growled abuse at them accordingly.

"Baboon, is it thus that you hold spear with toes in place of fingers? And thou, Bushman. Shield in your jungle was doubtless a toy of woven grass; is oxhide too heavy for you? Hey, fellow, fourth in the line, roll not your eyes like the tree galago of the night. This is the bwana sana who inspects. His one word to me is death."

The troop shuffled their feet and tried not to look self-conscious. The big Masai watched King out of the corner of his eye. King nodded. The Masai swelled his great chest.

"It is well, fellows. Today you do not die." To King, with nonchalance, but loud enough for all to hear:

"Cattle they are, bwana. Spearmen all they claim to be from their youth up; yet the ghosts of my fathers have wept that I have the handling of such. Feet have they and no hands. Yet this alone may be said for them: They will not run away."

And at that excoriating analysis of them the ten men swelled their dark chests.

At his tent flap Yakoub stood, unkempt from his exhausted sleep, his hair twisted in horn-like spirals, his beard a tangle; a veritable satyr of the woods in benevolent mood.

"It is a miracle, my Kingi. This recipe of the square deal works wonders. No other white man in Africa has such servants. I am converted to your application of the white man's burden. I shall make it a rule from now on."

King only grunted.

"A means to an end," he lied to cover any show of sentiment."I'm working this way for money. Get a move on. We've got to cover ground today. The faster we get to Karamojo, the sooner we can get through with the Ham Smythe job and away to our own little secret out of which you promise me so much money. And the sooner we get to see the old Wizard of Elgon the better we'll know whether he can give us any dope about that unknown country up there."

Yakoub agreed.

Ground, accordingly, was covered. The porters, under Barounggo's driving and the shrewd implication that they were not merely beasts of burden but fighting men of strength and spirit, made marches that were astonishing for safari travel.

Yet King frowned when, during the second day, topping each low rise of ground, he brought his prism glasses to bear upon a haze of dust that persisted behind.

"There's a safari behind us," he told Yakoub shortly."Forty or fifty men, I should judge."

He had taught Kaffa the—to a native—quite difficult feat of looking through binoculars. The Hottentot screwed his face into agonized contortions behind the eye pieces, looking above the dust and around it rather than at it, then lowered the glasses and scratched his head for a moment.

"Safari," was his verdict."Middle big safari, for the dust is not great. White man safari, for the vultures are not many." He looked up to study King's expression.

King frowned and grunted dissatisfaction.

Another day went by, the miles fell behind; but still that persistent cloud of dust hung over the horizon, the safari just below vision, even from the low, rounded hilltops of the rolling country into which they were coming.

KING swore angrily.

"There's only one white man I know who can drive a safari of that size to keep up with the speed we're making."

He stopped and considered awhile. His face set like rough cement work. He told Yakoub:

"You go ahead as fast as you know how and make for the wizard's boma. Kaffa knows the way. Sit until I come. I'm going back to make sure about those people. I'm taking Barounggo. Kaffa, I expect the men to make as much distance as if Barounggo were behind them."

The Hottentot instantly threw out his chest in ape-like imitation of the great Masai and screamed frightful abuse at the porters. They grinned cavernously at him.

"Buffaloes," he screamed at them, "Cattle of the fields, move! Run with speed! Or, look, I borrow the spear from the Masai. In the spear is a magic. With it any man can drive cattle as does that great one."

At which Barounggo looked with the enormous indifference of a mastiff, and the men guffawed. But the Hottentot knew his own methods of handling porters.

"Listen, goat men, beetle eaters. The friend of bwana is the Old One, the Wise One of Elgon. Let me not have to tell him that bwana's cattle dawdled on the way, or he will make a witch-binding upon you that will be remembered by the grass monkeys who will be your descendants."

And at that the porters covered their mouths with their hands and took up their packs with alacrity.

King swung back on the trail to meet that persistent cloud of dust. He had determined on one very definite thing—this trip with Yakoub. He had promised it for more than a year. It was a secret between himself and the Jew, this thing Yakoub had found out—a hint, rather, of a venture that might develop into vast possibilities. And nobody was going to intrude into the secret for which his friend had lived in anxious and patient expectation for all the months during which King had been called to half a dozen profitless deals.

The Masai strode grimly behind, muttering some rhythmic recitation deep in his throat with a reiterated chorus of sghee, sszee, which in the ideophone of his people represented the stabbing and swishing of flung spears.

"What foolish daydream do you chant, old blood-letter?" King wanted to know.

"I sing my ghost song, bwana. They are fifty and we are two. Yet it will be a good fight while it lasts. Though I think that with my ten whom I have been training we might have made some headway against those Shenzies."

"So talks Kifaru, the rhinoceros who charges blindly at each new scent. Do you think that I am a fool as well as you? There will be no fighting. We come only to look."

"If bwana so orders. Yet that but means that the fighting will be later. I will train my ten with the heavy stabbing spear."

King only grunted and strode on. As the dust of the safari began to come nearer he was careful not to top any skylines over the low hills. And when the confused clamor of African porters on the march began to be heard he looked about him to select a tall anthill well covered with scrub.

The safari came slowly on, three white men in the lead, the porters straggling out for a quarter-mile behind with some twenty spear armed askaris among them.

"See, bwana," the Masai whispered, "that is no honest hunting safari with so many askaris. There will be fighting, as I have said. I smell trouble. Lumbwa dog eaters are they all—twenty men. Yet with my ten who are Wa-Kuafi we could make a slaughter."

"Shut up," King told him, and he trained his glasses on the group.

His guess had been right, of course. The white men were Van Vliet and his two ill favored companions. How they had found out anything was a mystery to King and a blow to his conceit; for he had been desperately careful. Yet there was no room for doubt that they were following his trail. But it was not the knowledge that these men were obviously hoping, as the Hottentot had reported, to share in his secret business that infuriated King. He swore through set teeth and his hand closed hard on his rifle breech as he recognized among the porter loads some twenty very familiar wooden cases.

"Squareface," he gritted."Damn 'em! Twenty cases of trouble for some poor naked fools!"

He would have liked to open fire at long range from his shelter and obliterate these three menaces to black men and white alike; and he cursed the inhibition that restrained him. He growled to Barounggo:

"We have seen enough. Come on. From now on we must travel with speed and secrecy."

The Masai's eyes were eager, and he spoke softly through pinched lips:

"A throwing spear, bwana; a light throwing spear balanced close to the blade will be a good weapon. I will make me such a spear. And those ten, I will train them also to the throwing spear. Only twenty askaris, and Lumbwa men at that; the rest are cattle. Look, bwana, thus shall the battle go."

"Peace, murderer," King told him."Here is not even cause for a fight."

But to Yakoub, when he caught up with him later, he said:

"You were right. Yakoub the trader and Kingi Bwana can't go out together without at least three of the hardest cases in Africa following on their trail. They mean to crash in on our secret, and they've come prepared to fight for it. That's what comes of having a reputation as a shrewd business man."

The Jew's eyebrows disappeared in his tangle of hair; his hands outflung, he nodded sour, smiling agreement almost as if more pleased at the implied tribute to his astuteness than troubled at the complication.

"And," he appended, "of Kingi Bwana's having a reputation for knowing how to discover the secrets of the land—even if he doesn't know how to profit by them. Never mind, let them follow. Who are they? Three bad characters. It is nothing. But Yakoub and Kingi together—the Jew and the Yankee—that is a combination. We shall outwit them."

"By golly, if we don't outwit them," said King, "we'll have to kill them off like the rats they are. Come ahead, let's go. Move. Speed. Get distance."

A THIN haze far away to the left began to assume wavering outlines that came

and went as the mists drifted. Later in the day a pale gray cone hung in the

sky, ghostly, standing upon a chill purple fog of nothing. A cool wind

drifted down from it.

King broke away from the Karamojo trail and headed toward the mountain flank. In a sheltered valley at the foot of a long blue ridge nestled a thorn boma. Like the nucleus of a spider web, this isolated huddle of huts was the center of countless faint paths that came to it from all directions. But the most extraordinary feature of it that immediately arrested attention was its condition of dilapidation. Thorn bomas in the more accessible regions of East Africa are nowadays not intended for defense; their purpose is protection from wild animals. But it seemed here as if even the lions and hyenas knew that the home of Batete the Wise One was something to be treated with awe.

Fat cattle grazed around it. Naked herd boys gazed owlishly. The porter men clustered, wide eyed, at the gate. Barounggo, with immense disdain, but with spear gripped tight, prepared to follow his master within. But King knew the courtesies of calling upon wizards. He told his men to wait, and went in with Yakoub.

Inside the boma were several round, thatched huts; and in the center stood another decrepit thorn fence, hung all round with cattle skulls and colored rags and snake skins—all the regular appurtenances of sorcery.

Three low stools, each carved out of a single trunk, stood in front of the central hut in a patch of sun. Upon one of them sat a shrunken ancient. He might have been sixty years old, or eighty, or a hundred. His face had reached that condition of desiccation in which age could mark it no further. His limbs were wrapped in a monkey-skin cloak.

But he was no senile antique. He was alert, and waiting.

"Hau, jambo, Bwana Kingi," he called in a voice astonishingly strong for his appearance."Jambo sana. It is a long time since my eyes have been glad. See, the stools wait. And let your Shenzies enter. Potio is ready for them in the outer huts."

King had long ago given up wondering just how the old sorcerer gained his apparent foreknowledge of events. It might have been the blackest kind of magic, or it might have been no more than a system of native runners. Bush telegraph was a mystery recognized even by the government.

"Jambo, father of wisdom," King greeted the old man."My good fate has fallen on this day. You are well? Your house is well? Look, I bring a gift. In the nighttime the wind that comes from the ghost mountain is cold. This is a blanket from my own country. It is woven by hand and it will shed rain."

It was no cheap trade goods that King presented to the old man, but a gorgeous, lightning striped, genuine Indian blanket that he had long set aside for just this purpose.

The wizard's face remained an immobile net of furrows. Only the keen old eyes glowed. He dropped his ingrained habit of preternatural knowledge.

"There is no white man in the land but the bwana m'kubwa who would think of that. Sit, bwana; and this man, your friend, let him sit too. It is enough that he is your friend. The women shall bring maize beer and we shall talk."

THE talk wandered throughout all the little unimportances that are of import

to the dwellers in the wilderness. Gossip of the road and of the town: of

people's comings and goings and dyings, of the movements of game and of the

mealie crop and of the next rain. King knew it was necessary and he went

through with it. It was hours before he could bring in his inquiry about the

country up north where he wanted to go.

The wizard became silent and thoughtful. Automatically, as if from habit, he drew an odd assortment of cowry shells and colored pebbles and bones from a pouch and threw them fanwise in the dust. With a lean finger he sorted them and traced lines between. Hesitantly he began to talk.

"So? It is up to the People of the Amulet that bwana would go? So indeed? That is bad. They are a far people and a hidden people. Few people are left hidden in this land. It is a pity that bwana knows about them."

The old man nodded his head stiffly many times, moving his pebbles and bones almost like chessmen as he cogitated. Decision was difficult. He looked up squarely into King's eyes.

"It is a pity. Yet—if it were any other white man in all the land I would weave a net of lies for his feet. But if Kingi Bwana wants to go, who am I to plant the weeds of difficulty in his path? He will rend a way through many mats of weeds and in the end he will get there. I will, therefore, tell him truth and bwana will see those people and will do the thing that he will know to be right."

The old man was talking no mumbo-jumbo of his craft now. This was a confusion of words with a meaning behind them. King sat silent, waiting. Yakoub clawed nervous fingers through his beard.

"This is the truth, bwana. Even I, Batete, whom men call wise, do not know that country. I know only that the people are the People of the Ancient Amulet. This is the magic of that amulet: That whosoever shall see it, it shall tear his heart in twain that he can not take it away with him. This too I know: The people beyond the Toposa, between them and the hidden people, are an evil people, strong and war-like. And this last thing I know. The road to the hidden people goes by the mountain country of the black Christians, very steep and difficult. He who does not know that the mountain is the road goes to the left, which looks as if it should be the road; and at the end of many days he loses himself in the swamps that guard the country on that side. That is all that I know."

The old man relapsed into silence.

In a low tone Yakoub addressed King:

"The black Christians. He must mean Abyssinia. And the Hidden People—that must be the strip of unclaimed territory along the Sudan-Abyssinian border that we hear about. But what is this amulet thing? Have you ever heard, any so queer story?"

King shrugged first a dubious negative and then nodded in slow reminiscence, reluctant to break the spell of hidden romance that had settled on them. He whispered only to Yakoub:

"Something once long ago; a fairy tale that might connect. But the place sounds like where I figured it would be. Those rivers must rise somewhere in that mountain country."

Suddenly the wizard spoke out of his muffling robe:

"Blood is on the trail of bwana. Much blood."

"So said Barounggo," murmured King."Tell me of that blood, wise one. What do you see for me?"

The wizard remained hunched under his blanket and moaned. His voice came painfully:

"I see only blood. White men will die." He twisted his body and appeared to strain himself to effort; then he relaxed."But my snake does not show me the faces of those men. Many black men will also die. There will be much blood."

He relapsed into stertorous breathing. King muttered to Yakoub:

"Cheerful, isn't he?" Then his teeth set hard and his jaw stuck out at an ugly angle and he grunted, "Well, if one of them is going to be me, there's going to be others too."

The wizard spoke again:

"Let bwana now go and let him send his men to me. Because bwana is my friend of old I will make a magic for those men that their hearts may not melt in that blood—the strong magic of the lion dance. Let bwana go and send his men to me."

King knew that this was dismissal; and he knew better than to try to stay and witness the spellbinding that the wizard would make over his men.

"This is a great thing that you do for me, wise one," he said in genuine appreciation; for he knew that such a witchcraft would be infinitely more efficacious than any exhortation or leadership or promise of reward."Wise one, I go. But make speed with the magic; for there is great need."

ANOTHER two days passed. No cloud of dust followed behind. But King was by no

means satisfied. It didn't mean a thing, he grumbled. Van Vliet was nobody's

fool; he was just hanging back a bit; he wasn't so easily scared off. And the

old wizard with his gloomy talk about blood… King didn't believe any

of this pretense at prophecy—or, at least, he said he didn't. But this

was Africa. He had seen things and had heard things that required a lot

better explaining away than just laughing them off as native hokum.

King shrugged savagely at his own gloominess. He could positively feel that something was about to happen after listening to that old man. But there to the left was the trail to Karamojo, and in his pocket the sealed letter which had become such an incubus. He told Yakoub to supervise the making of the boma and chose himself a flat rock where, with an expression of martyrdom, he sat down to break the seal.

And in that same place and position Yakoub found him when he came an hour later to call King into the finished boma for supper. King sat very still, gazing into distant nothingness through the dusk haze, whistling, as was his habit, thin disharmonies through his teeth.

Yakoub knew that sign. His face lost its customary expression of genial cynicism and he came quickly closer.

"Trouble?" he asked.

"Plenty," was King's answer.

"Well—" Yakoub shrugged—"fifty per cent of a partnership is for the purpose of sharing the profits; the other fifty is for sharing the worries. Tell me this so unpleasing secret."

King grinned wryly up at him.

"Yakoub, old friend, I'll tell you a truth that we both know; and we've both been so cocksure of our smartness that we've forgotten it. Listen to it again: There are no secrets in Africa!"

"You mean—our business? It is the same? This Mr. Smythe knows too?"

King nodded.

"All I wonder is how he got on to it. Gosh, I thought I had stumbled on to something new. I thought that this was really a dark one. Consider it again and tell me if I was a fool.

"I came out of Beni Shangul in Abyssinia—and that's full of gold; only old Shogh Ali won't let anybody work it without an army. I worked south amongst a lot of crawling little Atbara tributaries that haven't even got names. I fished a man half dead out of a mountain stream and, stripping him for first aid, I found those little ingots. And all hell and a bluff at torture wouldn't scare a peep out of him about who or where or what. And he had the guts to laugh when my bluff fell through.

"I tried to prospect it up. But that river ended in a hole in the ground; subterranean from somewhere higher up. I tried other streams; but the mountains were fierce, just about perpendicular. And where they fell away into the plain miles away west there was peat bog, morass and, lower down, swamp in the flat, empty desert, just like the witch doctor said. Hellish country. So I pretty near died getting across to the White Nile at Mongalla and I figured there must be a way in from the south."

"My friend," said Yakoub with serious conviction, "I will tell you this about gold. You were not overconfident; you had every right to think this was a new thing. But gold is a queer material. It is devilish and magnetic—but only in large quantities. A few gold pieces can not talk to one another. But where a man has a large accumulation of gold, other gold tells it telepathically: 'Look, I am here, in such and such a place. ' But usually the message comes only to my people. What right has this Mr. Smythe to know?"

King was able to muster a crooked laugh at this queer whimsy that had so much of cynical truth in it.

"Well, he knows all right. Only he doesn't know any more than general location; no more than I did till the old wizard gave us the straight dope."

The Jew quickly reviewed this new angle from his viewpoint of a business man. He grimaced sourly.

"I will tell you this also about gold, my Kingi. When you have none of it, a very little of it makes you its slave. You have taken this Mr. Smythe's money, five hundred paltry pounds of it, and now you are tied with a chain. But—" his alert mind considered the thing from the viewpoint of business; and, like the financier, he quoted the inexorable law of business—"after all, we can not develop our finds without capital; and if this Mr. Smythe has felt that the thing is so great, there will be enough money for us not to worry.

"Only this time, my simple friend, you will let me talk to the capital. You are a child, I think I must have told you, in matters of business. From now on I, who am your partner, look after your negotiations. You have nothing to worry; I will yet make you rich in spite of your foolishness. Your Mr. Financier Smythe knows no more than general location, hunh? Very well, we have a starting place from which to begin the discussion that we shall have, this Mr. Smythe the financier and Yakoub the Jew."

King got up from his dejected position and stretched his big shoulders till the sinews cracked.

"Friend Yakoub," he replied wholeheartedly, "you take a load off my chest. Let you do the negotiating and me do the easy work of just getting there. That's a good partnership. Let's go eat."

AN hour passed. The meal had been finished, the pipes lighted, and King

laughed in carefree enjoyment of nothing at all. The night was warm; the food

had been sufficient. They had reached the water hole before the

evening-drinking game had polluted it. It had been a good day. King leaned

his head back in his folded hands, stretched his legs to the top of a pile of

duffle and blew smoke rings.

Behind in the shadows, their masters having eaten, the natives chattered over their potio of parched corn and fresh antelope meat and with African carelessness stole dry thorn sticks out of the boma for their crackling fire, leaving gaps that a leopard could easily crawl through. Everybody was contented.

Suddenly came the Hottentot's voice:

"Bwana! Men approach!"

King dropped his feet from the duffle pile and reached for his rifle which always stood ready to hand against the tent pole. But these men had approached very carefully indeed; and they knew how to approach—as they had to know—very thoroughly, taking the risk of the outside darkness.

"Just as you were, Yank. Take it easy and make no mistake."

Van Vliet stood framed in the opening of the boma, watching over his rifle. He had timed his arrival exactly, counting on the general relaxation after dinner and knowing that the last thorn bush would not be dragged into the boma gate until bedtime.

The man Johan and Dago Lopez sidled in past him. They were well rehearsed. Johan helped to cover the party with his rifle, and Lopez stepped forward and removed King's rifle out of reach. Then with business-like deliberation he searched both white men for guns.

"Alla right," he reported.

King had no inkling as to what might be the move. So he put a match to his pipe and waited.

Van Vliet came forward.

"We're goin' to talk, Yank," he said with a determination which showed he understood to the full that any talk between them would have to be forced.

King was uninterestedly resigned.

"Well, since you insist on being social, I'm listening. But why all the armed escort?"

Van Vliet grinned at him in enjoyment.

"I know you, don't I? All East Africa knows that your business is your business. An' d'you think I didn't spot those two klipspringer that winded you an' acted up that way? I sent a man over immediate, an' he picked up your trail exact where you'd been watchin' us."

"Oh, pshaw!" King laughed as if caught out in a game.

He put his feet up on the duffle pile before him and put another match to his pipe.

"I'll hand it to you, Van. I'd hoped you wouldn't notice them, or that you'd put it down to hyenas or something. But I might have known you'd be taking no chances. I always told Yakoub you were nobody's fool. What's on your mind?"

Van Vliet nodded in acknowledgment of what he knew to be his own worth.

"We're goin' to talk, Yank. An' you're jolly well goin' to listen."

"All right," said King, as if it were he who condescended."Make it snappy 'cause I don't like your friends."

"Damn your hide—" Johan lurched forward.

At the same time a sharp hiss of intaken breath came from Lopez. But Van Vliet's growl stopped both of them short.

"Easy there, you two. I'm runnin' this. An' you, Yank, you're not winnin' anythin' with insults. We haven't come for trouble; we want to arrange this thing nice an' friendly. So you just sit tight an' listen."

"I'm always friendly on the front side of a rifle," said King, blowing huge puffs of smoke into the night and watching all three men warily from behind its screen."Go ahead and say your piece."

Except for Van Vliet's careful watchfulness, the scene might have been a friendly visit of passing safaris. King at ease in a canvas chair tilted back, throat, nostrils, and cheekbones thrown into yellow relief by the lamp. Yakoub in another chair, passive, humped up like a brooding bird, only his bright black eyes taking in every move. Across the table in the paler outer circle of light, three men framed against the warm velvet blackness.

Only one unusual thing indicated tension. Just as insect noises, warned by a mysterious telepathy, fall silent when there is a jungle killing, the chatter of the natives out of the dark behind the tents had ceased.

Van Vliet put his proposition with commendable brevity.

"Fightin' won't pay any of us. We make you an offer to join up with your outfit an' split even."

"Split what?"

"Ah-h-rgh!" Van Vliet's patience did not hold out well."We know what you're out for. An' you know I'm workin' for the DeWet company."

"Yeah, I know." King was exasperatingly supercilious. He knew that in any argument the one who lost temper first lost opportunity with it."But what interest have the DeWet people with us? They hired you and your two gangsters to peddle gin to the natives."

"Damn you, Yank! Easy there, you two. I'm boss here. Come off actin' innocent, you. I tell you we know. DeWets have been watchin' your boss, Ham Smythe, for weeks. Their London agents have reported every time he breathed an' batted an eye. They've been in this game long enough to know when somethin's movin' on the quiet."

King suddenly threw himself back in his camp chair and astounded everybody by shouting with laughter.

"DeWets! Oh, of course, the DeWet crowd would know. Do you hear that, Yakoub? DeWets have been watching him for weeks. Ho-ho-ho! He thought he had a secret—a secret in Africa, the poor fool. Land sakes, this is funny. And we thought you were interested in us; Yakoub and Kingi together. This is good for our conceit. So DeWet sniffed a rat in all the elaborate precaution and put a watch on Smythe. Ha-ha-ha, what a secret!"

And at that Yakoub, too, saw the irony of the situation and he crowed aloud with acrid laughter.

VAN VLIET regarded them both with dubious anger. Here was something that he

did not understand, and the tension was beginning to wear on his nerves. Even

more so on the others.

"Aw, he's makin' a monkey outer you," snarled Johan.

Lopez shifted suddenly like a black leopard in the dim outer fringe of the lamplight. His hand stole down to his boot top.

"What the hell you got to laugh at?" growled Van Vliet.

"Ho-ho," King chuckled exasperatingly."The joke, my dear Van—but I know you won't believe it—the joke is that Yakoub and I started out on this trip on a deal of our own. We've only just learned that Ham Smythe is in on it."

Van Vliet stood angrily suspicious. He could see no joke in that situation without understanding a great deal more about it. But Dago Lopez was quicker to attribute a foul explanation.

"Ha, you don' work for heem no more. You don' foola me. You doublecross heem an' you go for yourself."

"Why, you filthy—" King pushed his chair away and rose to his feet. It was an interpretation that had never entered his mind as possible, and the insidious foulness of it enraged him.

"Easy there!" Van Vliet's rifle pointed squarely at his chest."An' you drop that, Lopez. I told you there'd be no knife play, you fool."

Lopez glowered till Van Vliet's will dominated him. Then he shrugged and his teeth glinted white out of the darkness. He offered the olive branch to King on a basis of give and take among equals.

"Alla right. Then we onderstan' one the other. We doublacross DeWets an' we go weeth you. So we alla mek planty moch more. Hunh, Van? Joost lika we talk before. Ees good."

King was master of his indignation again. He was very deliberate. His move had brought him closer to his rifle. His words were chosen and distinct.

"Well, I'll tell you, Van Vliet, I might make a dicker with you—if I was drunk or doped. I'm not proud. I'm not ashamed of anything that creeps or crawls or stinks. But your partner, Lopez, there—"

"Morte de Deus!" Lopez screamed in ungovernable rage at the sudden twist of insult. The light glinted on a venomous arc as his hand flung back over his shoulder.

"Drop it!" shouted Van Vliet.

The agony of apprehension in his voice was astonishing. He jumped blindly for Lopez. But he was too late. Lopez's arm was already in the swing of his throw.

"Sszee!" shouted the voice of Barounggo the Masai from the farther darkness.

A thin shaft of yellow light swished past King's shoulder. Lopez's arm twisted spasmodically in its down swing; his knife spun high, turning glittering somersaults in the air and fell somewhere out of the light circle.

In that instant of confusion King made one enormous bound and snatched his rifle; and when in the next instant Van Vliet and Johan recovered their wits King had them covered.

"Ve-ery careful, you two," he warned them."In this bad light I'm apt to be jumpy. Take their guns, Yakoub. So. Now you can look to Lopez, you two."

Lopez's dim form was writhing in the shadow. He was snarling in furious pain and rage.

"There was no order to slay," said the voice of Barounggo, "so I but transfixed his arm. Hau, it was a good cast. A good spear, a light spear; swift as the snake of the night—"

His voice began to break into a rhythmic chant.

"Shut up," snapped King."Still, it was well done. Guard now those two white men. Here, Kaffa, bring the light and let's see how much damage was done to his arm."

Lopez was sitting up, gritting his teeth, his arm awkwardly stiff with a thin shaft protruding from his biceps, the narrow blade ten inches through on the other side.

"Hm, a nice clean hole," commented King coldly."Better than you deserve. A knife, Kaffa." He ripped the shirt sleeve.

"Now clench your teeth, Dago. This is going to hurt you more than it does me."

With a quick jerk he pulled the blade clear. Lopez yelped once. Then King said calmly—

"Water, Kaffa."

The Hottentot was well experienced in the requirements of camp surgery; already he was there with a bowl and the iodine bottle and bandage.

The little operation was completed with methodical dispatch. Lopez stood sullenly muttering and holding his arm. King motioned him over to join the other two. Then very carefully and meticulously he lighted his pipe, making time to think. A half minute was sufficient.

HE turned to the three prisoners. He knew exactly what to do. His eyes

smiling narrowly over the lantern were belied by the hard, incisive

voice:

"The other way round again, eh? Now I'll tell you three crooks what you'll do. You knew enough to come here after dark. So you'll know enough to go. But I'm holding your guns—no sniping out of the night— No, don't yelp yet. I know well enough that taking a white man's gun from him in the African bush is murdering him.

"You'll find them in this place tomorrow, if nothing eats you up tonight. But that's your funeral that you brought on yourselves. My advice is that you climb a tree right quick—a good thorny one—and I hope to holy Pete it hurts you plenty. Or you can make a thorn boma, and that's another sweet job by firelight. Got matches? All right. Git."

He motioned with his rifle. The three men, looking at that thin smile shadowed in hard hewn lines by the lamp, knew that King would not relent, although they were receiving a vastly more generous deal than they would have given. But Van Vliet was a man not often thwarted. He held too hard a grip upon himself to fly into any sort of ungovernable rage; but there was cold venom in his voice as he pointed his last threat at King:

"It's you or me, Yank, from now on, and so I'm tellin' you. You can't leave me out of this deal, whatever it pans out. An' I'm not talking partners any more. You've had your chance. There's just one of us two is goin' to win."

The man was courageous enough, standing there covered by the rifle of the man whom he threatened. But he knew King as well as King knew him. He was perfectly assured that that rifle would not go off unless he were to make a direct physical attack. And he knew King much too well to make any such attempt as that.

King's face in the flickering lamplight was a mask of hard corners and thin slits. A bitterness soured the set grin; a bitterness caused by the knowledge of his own inhibitions which prevented him from removing with one clean shot what he knew to be a menace of treachery and trouble and bloodshed.

"All right, old-timer. You or me. There'll be a whole lot of people, black and white, a whole lot better off when you're through. And that goes for Dago Lopez and your gunman too. And let me tell you this again like I told you before: Yakoub and I, we're going on our deal alone. Now skip. Footsack. And I hope the lions get you before I do."

Sullenly the three men went from the boma. Their footsteps sounded awhile. Then the night swallowed them.

King was full of an exhilaration that was extraordinary in the face of a threat of death left by a man whom he knew to be infinitely cunning and dangerous and whose capabilities he was grudgingly forced to admit. He bustled about the final preparations for the night and his voice glowed with an astonishing satisfaction.

"All right. Get a move on there, everybody. Get that thorn tree pulled into the opening there. See that it's good and high. All fast for the night. Barounggo, let two men watch together by turns."

Yakoub stood thoughtful, troubled, while King went about, whistling in the greatest good humor, attending to the last little precautions and inspections for night in an open boma.

The muffled clatter of the delayed tin plates of supper died down. Uncouth yawning noises came from the natives behind the tents. The snap and crackle of sticks added to the all-night fire. A soft clapping of hands and a rhythmic stamp of feet betokened the Masai getting ready to chant the delayed song of his deed before his troop:

"Hau, it was a good cast. A fair cast, a clean cast. In the dark stood that one. Where is he?Ow, he is gone. A light spear, a swift spear. Whence did it come?Out of the dark it flew. True and straight. As a snake it stung." King knew that that would go on for an hour. All the details, all the action, even the impelling thought, would be given poetic expansion. He grunted to himself.

"Probably keep us all awake. But he deserves it. It was good."

Yakoub still stood thoughtful and troubled. King in his high spirits rallied him on his depression.

"I'm afraid," said Yakoub, "that those are three poisonous snakes allowed to go loose. Yet what could one do?"

"They are," said King cheerfully."And one can't do a thing. That's a rule of the outer places. The poor fool who has inhibitions always loses out against the other fellow who has none. We can't cut their throats, but they'd cut ours the first minute it suited them; and that's all to their advantage. But do you know what advantage we have gained out of this night?"

Yakoub shook his head dolefully.

"I see no advantage that makes you so cheerful. Only that your religion of the square deal applies to three clever and quite unprincipled enemies."

King laughed happily.

"Not so, my mournful friend. Consider. Twice now Van Vliet has interfered to save me from harm; both times to save my life. Is it because he loves me do you think? Or is it—tell me if I'm not right—is it because he doesn't have any hint of where this gold is. The DeWet people who hired him knew only that Smythe was on to some big secret. So they hired a hard, bad gang who knew safari work to follow whoever Smythe might hire, to wipe them out of competition and steal the secret. So that's all to our advantage."

"I see," said Yakoub."Our advantage is that we are followed by three ruffians who have no inhibitions and who have come prepared to steal the secret at any cost."

But King's cheerfulness was proof against misgivings.

"Not so, my doleful Yakoub. Our advantage is that none of them—not the three hard guys nor Smythe nor the DeWet company—know anything about the location of that secret. Only we. And that's a real secret this time. And that is to our very great advantage. You said yourself that we'd outwit them, or we'd have to—" King's face made three hard horizontal lines—"outfight them."

WITH the morning not a sign was to be seen of the night's visitors. Kaffa the

Hottentot was already up and had made a circle of stones and oddments of lion

claw ornaments and bits of skin that he had taken from the Shenzies. Inside

of it he danced and genuflected and chattered with an intense solemnity.

"What, can you tell me, is that completely mad devil doing?" Yakoub asked of King.

But this was a new manifestation of his servant's many queernesses, even to King.

The Hottentot finished his incantation and stepped out of his witches' circle.

"I make invocation to Atto Happa, who in my country is the lord of all lions and leopards and beasts that slay," he explained.

"And what for?" King wanted to know.

"But that is plain, bwana," the Hottentot told him."Surely in order that the beasts, if they have not already slain those three, may yet do so before the sun becomes too hot for hunting."

"Hm, I hope your Atto Happa delivers the goods," King grunted."It would surely save a heap of trouble for a lot of people. Did you hide the rifles as I told you?"

The Hottentot screwed up his shoulders and leered like a distorted black gnome.

"Assuredly, bwana, did I hide them. First having stuffed all oily places with sand, I shoved them down an ant-bear hole as far as Barounggo's spear would reach. A father of the mission told me that the gods help men who help themselves; and thus have I done my share toward earning the favor of Atto Happa."

King considered the matter, frowning.

"Pretty drastic," he muttered."But Van Vliet won't overlook anything so likely as an ant-bear hole. I only hope there are plenty of them and that he'll dig them all before he comes to the right one. It'll win time for us; and time is what we'll need if we're going to shake him."

KING scoured the horizon for dust as the days passed. Dust there was, lots of

it, rising slowly behind or eddying away to one side. But it was intermittent

and traveled this way and that in slow, low-hanging drifts or in tumultuous

spurts—animals grazing peacefully upwind or dashing in wild stampedes

as some taint in the air alarmed them.

Dust there was, too, before them; once a quite heavy cloud. King inspected it anxiously through the glass; they were getting beyond the confines of the Toposa tribes where the natives were, as the witch doctor had said, strong and war-like.

"Wildebeeste," King announced with relief."I can see the tick birds. Probably zebra with them. It'll be good trail smudge."

He hurried the little safari along on a long slant to get in front of that grazing herd, and for half a day he held that position, letting the countless hoofs obliterate all other tracks.

Twice he was able to do that. In spite of grumbling among the porters he insisted upon making the nightly bomas far from water holes, carrying the minimum supply requisite for camp. Cooking fires were screened. No smoke was made by day.

These were days of hard and uncomfortable going. Not for a moment did King relax vigilance or permit himself to underestimate the ability and the persistence of the man who followed. But Yakoub, observing all these precautions that seemed to him sufficient to baffle a bloodhound, found it in himself to be more optimistic. The farther they went, the nearer must be their goal. To him it was irresistible to speculate upon that mysterious country of the Hidden People.

Who might they be? Why did the witch doctor so darkly insist that it was a pity that anybody should know about them?

King, with a certain hardness in his voice, was able to elucidate.

"Huh, that's an easy one. There's never been a savage race in the history of the world which hasn't claimed it was better off before the white man came. Which I'm not defending one way or the other. But that crowd behind us with twenty cases of trade gin is a pretty big argument."

The Jew, with his keen mind trained to balance the hazy profits of future prospects, could no more refrain from the fascinating game of computing from the eagerness of others the possibilities of vast fortune lying waiting for them, than could King from computing, by the movements of birds and game, the location and distance of the next water hole.

But King's guessing was concluded with each successive evening. Yakoub's was interminable. That mysterious amulet which would tear at one's heart strings—what could that queer thing be? What could so rend a heart because it could not be taken away, but some wonderful jewel? Surely a jewel. Sacred, of course, and its origin wrapped in legend and folk lore. That, too, would be fascinating. Yakoub had a hereditary veneration of ancient tradition.

And about doing the thing that was right—what could the old wizard have meant by that? What mysterious power could an amulet, however ancient, have to make practical men of the modern world—a Jew trader and a Yankee adventurer—do some enigmatic right thing?

Again King was able to elucidate. A little self-consciously he explained—

"That's really one of the biggest compliments I've ever had handed to me; and it's a direct intimation that the old principle of the square deal sometimes pays a dividend."

The Jew's eyebrows made an inquiry; his two hands were busy attending to the rifle that he had learned from King's example to carry himself. King elaborated on the details of his African diplomacy.

"The old witch doctor of Elgon earns his name of wise one. He knows that the square deal as the white man, or as the white man's well meaning government, may see it is not always the way the African sees it. My pull with him is that I've often consulted him about the queer native angle. So he didn't attempt to hold me up on information, but said that he'd lie to any other white man, only he'd tell me because he knew I'd do the right thing for those people; and, putting it that way, don't you see, the wise old bird knew he'd have me tied up under an obligation."

Yakoub nodded. He trudged a long distance, nodding in silence. At last he said, as if musing in understanding, oblivious of King's presence:

"Yes, it is so. We too, we know it. A few governments have from time to time tried to do the square deal for my people; but, alas, it has not been as we have seen it."

Those were exciting days, days—since all things are relative—of good going.

A pale purple haze began to show across the horizon to the northeast. King inspected it at long range with interest. Yakoub was immediately full of excitement; but King only shrugged with exasperating apathy.

"May be only mirage. We'll know more by tonight's camp."

With that night's camp the haze was no nearer. It remained a pale discoloration in the immeasurable distance. King got out his maps and, after a brief survey, announced:

"Yep, that's our mountain of wealth all right; look, there's nothing at all marked on the map, and I see that there's swamp country away to the left of the haze."

This was all quite enigmatic; for the map was truly a blank, marked across a large expanse in thin, wide spaced type. The haze was no more than a smudge of pale color, and as far as the eye could see to the west was nothing but parched brown grass and patches of mimosa scrub. Yakoub's shaggy eyebrows and his shoulders together put the question.

King pointed again, high up to the evening sky.

"Water birds going home to roost; look like ibis or spoonbills. And see, here's the Abyssinian plateau marked all along the East. The thing that isn't marked must be some sort of unexpected outcrop. That'll be the 'unclaimed territory' that so exercises the diplomats up in Adis Abbeba; and there will be our Hidden People. That'll put some extra pep into all our shoeleather, eh?"

KING grunted with disgust as a tall, nude figure stood suddenly in hard

silhouette against the sky over a low rise. He had

hoped—almost—to get through to the now visible goal without

running into any of these people to whom the old wizard had given the

reputation of being evil and war-like.

He knew better than to display any sign of hesitation. Ostentatiously he lighted his pipe.

"There'll be more somewhere," he muttered to Yakoub."Probably lying down in the grass. This one is only to distract our attention; he's too durned unsuspicious looking without even a spear in hand. Hold your ten men here, Barounggo. I'm going ahead to make indaba. "