RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

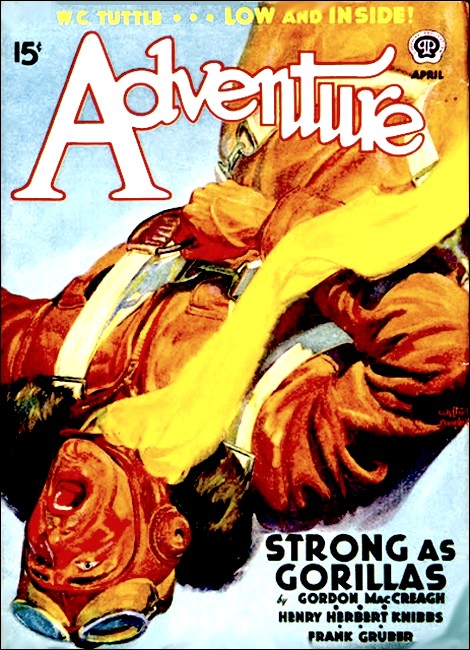

Adventure, April 1940, with "Strong as Gorillas"

CAPTAIN HAWKES of the British East African police pleaded with his prisoner.

"Really, old chap, you must help me out here. You've got to go out and get this brute, whatever it is; catch it, shoot it, or something. Dash it all, the thing is terrorizing the town. Doors locked, children kept indoors and all that sort of thing. The Colonial Government can't allow that."

"Nothing doing." King lounged his length comfortably in his captor's longest cane chair and tinkled a swizzle stick in a tall whisky peg. "I'm a wounded man with a spear hole in my side. I'm scared of mysterious monsters that howl around towns at night where no monsters should be. Besides, I'm under arrest here for not saying my prayers to your sacred Colonial Government."

"You are not." Captain Hawkes' face flushed. "What I mean, old man, I wired it all to the commissioner and he said I'd better turn you loose on your own cognizance."

"Bet you didn't tell him all the truth." King grinned shamelessly. "Did you tell him about ivory poaching, and that passport business, and that crucified man I shot right before your eyes, and all the other hide-bound laws of yours that you say I've busted wide?"

"I did indeed. 'Pon my word I told him everything, and he wired back—his very words: 'I know that Yankee reprobate better than you do. He's too smart to let any charges stick.' And he said to give you his strictly unofficial regards."

King's straight sandy brows arched. "Yes, I suppose with your staunch official integrity you confessed everything.—And your grub here seemed so good after the two of us living on lizards."

The quite unusual condition between captor and prisoner should be explained by the fact that Captain Hawkes, new to the district, had set forth, full of indignant zeal, to arrest Kingi Bwana of the backlands for a long list of heinous offenses against His Imperial Majesty's Colonial Government, and in the ensuing skirmishings King had at least twice pulled the officer out of serious holes.

"Awf'ly sorry, old man." Hawkes was apologetic. "I can't extend hospitality any further—officially, of course. And anyhow—" He turned on King with the righteous peeve of a man being let down by a friend—"you've got to help me out again. Dash it, if I weren't wounded worse than you, if I could move my shoulder at all, I wouldn't ask you. But—"

"Can't." King said positively. "Can't do a thing without Kaffa, my Hottentot. You've still got him on his confession of stealing those cartridges that saved all our lives. Can't wriggle out of your stuffy law by just recanting his confession."

Hawkes' face darkened to the inevitability of British justice. Then it cleared. "I'll release him in your charge. I can do that on my own authority. I'll have to bring his case up, of course, but I'll recommend a fine instead of jail, and I'll pay it myself."

King grinned.

"Yeah, you would bull-dog it. In my country we'd just get some crook to squash the case and save a lotta everybody's time. Well, I'm an invalid, but since you'll agree to turn my man loose, I'll listen. Just what is this mysterious monster?"

"Hanged if we know, old man. Nobody knows. It's just been there the last two nights, howling and crashing along the jungle fringe. The natives come white-eyed and say it's a ghost gorilla."

"Any killings?"

"Not yet. But you know how suddenly killing can come in Africa. And our policy, of course, has always been prevention rather than retribution."

Hawkes spoke with serious conviction. King's grunt was ribald.

"Atta boy! Colonial Empire speaking from its pyramid of bones—All right, Britisher, we'll argue it later. We got a ghost gorilla on our hands right now, due to do some murder any minute. Which doesn't make sense, since there's no gorillas any nearer than your farthest borders this side of Belgian Karisimbi. Another of those African impossibilities that always end up sticky red anyhow. Okay, then. If that's the price on my Hottentot, gimme a deed on him, free and clear, and I'll stagger forth."

Hawkes, having gained his official point, suddenly became human again and showed his private anxiety. "You're sure you're well enough, old chap? What I mean, fast enough to get out of anything's way?"

King shrugged. "Who knows how much is 'enough' in the jungle? Anyway, I can shoot fast if I can't run fast."

WITH the lowering dark, three shadows moved as silently as shadows should

through the deeper shadows that an early moon accentuated along the jungle

fringe. King was unmistakable; tall and lean muscled, dressed in British

shorts and the hot but practical woolen puttees up to his knees as a

precaution against snake bite, topped by a dilapidated shooting coat that

gave easy play to wide shoulders; under his arm a rifle that could shoot, at

close quarters from that position as straight and much faster than most men

from the shoulder.

The shadow that bulked behind him was as tall and even broader, dressed, in the dimness, apparently in nothing at all but monkey garters at knee and elbow and a Masai spear, the blade of which glittered a good three feet long when the moonlight glanced on it.

A pair formidable enough to venture at night into African shadows where a something howled. The third shadow was as grotesquely stunted as the other two were big, a gnome of the gnarled tree root hollows. Despite the heat, a wisp of ragged blanket fluttered from his shoulders as he scuttled behind, before, all around, as alertly as an eager hound, chattering an incessant whisper of comment, advice, caution.

"Pss-sst, Apeling," King told him. "Use your bat ears and nose more and your tongue less. We don't know what this thing may be or how it may attack. That shenzi whom we questioned said it was the shape of a gorilla, only it ran with the speed of an ostrich."

"That shenzi," The Hottentot scoffed, "was more frightened and foolish than a calfless cow. Men of the plains, shenzies, are like these Masai—all things of the jungle are ghosts to them."

"The reason—" The Masai quoted the plainsmen's proverb—"why there are no more Hottentots is because their children are monkeys."

"Of which," King commented dryly. "I wish I could be as certain myself. Less chatter and more attention. What new evil may happen in the jungle not even a Hottentot knows."

Shadows melted in again with shadows, the wavering hands of blind men before their faces, feeling the ground with their feet before setting weight on them, with infinite caution working against the hot night wind.

Until out of a black nothing the Hottentot's voice came. "'Ngalia, Bwana! Look out. A something moves in the wind before us."

Neither King nor the Masai could detect a thing other than the normal sounds of the night jungle around a peaceful white settlement—the rustle of a porcupine in the dry magongo leaves that are impervious to moisture and a curse to hunters, the far cough of a leopard, and the querulous complaint of sleepy monkeys.

The big Masai shook himself so that the quill fringes of his garters rattled.

"So do the ghosts talk to one another," he said uneasily.

King heard a long sniffing noise at his side and he knew that the Hottentot's wide nostrils flared and twitched like a chimpanzee's.

"But the smell on the wind. Bwana, is not the smell of 'ngagi the great ape, whose smell is the smell of an unwashed bushman and carries far."

King ran his coat sleeve over the hand grips of his rifle to wipe slippery sweat from them. "What kind of a smell, then, must we expect?"

"The smell of a meat eater, Bwana. Yet it travels with too much noise for the great cats, and it travels, not like cats, but along the cattle trails."

"Assuredly, then, a ghost," the Masai mumbled.

"Sure fits with nothing else," King growled.

Then both he and the Masai heard the thing. A pad, pad, of heavy trotting feet and the swish of branches that swung back into place. Then the sounds stopped. The whole jungle stopped still. All the night creatures, disturbed by the unfamiliar something, crouched and held their breath until they should judge it safe to resume their various occupations.

"Looking for us." The Hottentot's whisper came from a height already above King's shoulder. "Here is a better place to wait, Bwana, than upon the ground."

THE Masai's pride forbade that he should do anything that his master would

not. Only he admitted, "I like this not, Bwana. Give me daylight and

open ground, and I will meet this thing, foot to foot, spear to spear. But

this hunting of jungle ghosts is no work for a man."

Out of the farther silence a rapid drumming sound began to grow, a hollow beating of fists on a barrel chest, and then a hoarse roar that emptied giant lungs as though steam pressure actuated them, winding away in an eldritch screech.

"Whau! 'Ngagi!" There was enormous relief in the Masai's voice.

But King remained puzzled and wary. "Not so easy as all that, old warrior. Gorillas don't run at night; they sleep like men. Nor can we smell him. Nor does one howl like that."

The Masai reverted to his superstition. "Then surely the ghost of one that runs and slays by night."

One canny rule that King knew for all dealings with natives was, whatever he might be feeling himself, never to show indecision. He took the direct road of action now.

"Come ahead, you two. If this thing travels the cattle trail, the thing to do is find the trail and wait there. Whatever it is, a two-twenty magnum bullet will stop it."

Masai and Hottentot moaned, but with superb loyalty both followed. The Hottentot even scuttled ahead.

"Careful, little one," King whispered. "Better stay to heel."

But the little man only said: "Nay, Bwana, who but I will smell out the cattle path? And who will find the tree that I must swiftly climb when it comes?"

And sure enough, out of the heavy blackness he presently whispered, "Here cattle have passed, as even a Masai may feel with his great toes; the path is wide, as we know by no branches to our hand; and there is a patch of moonlight where the ghost, if it can be seen, must pass. This is a good place from which I, in a tree, can give notice of its coming."

But he did not have to give notice. The monstrous roar shivered in the air again and then the heavy pad, pad of feet, not fifty feet from them, beyond a black tangle of jungle.

The Masai's quills rattled and the smooth hiss of his hands passed along his spear shaft. Only a ghost would see those motionless shadows in the shadow.

The sounds grew closer, slanting towards them. The Hottentot's voice came like a bat's squeak from above.

"A path converges into this one, Bwana." And then, in the lowest possible range of human sound: "There, Bwana! In the trail! At forty paces'"

King sensed, rather than saw a bulk in the farther blackness. He could hear its heavy breathing as it stood and looked up and down the path. He knew that a great formless head swung this way and that by the hoarse hiss of wind between its teeth.

It was a sharp warning to him to hold his own breath, and with that he felt that the thing would not fail to hear the hammering of his heart. His rifle inched forward. Not much to shoot at, a sound, a ghost that bulked indiscernible in the dark.

And then even that sound stopped. The thing must be holding its own breath. It must have sensed, if not seen, something in the blackness. King reached out a hand to find the Masai. By finger pressure alone he tried to convey the impossible message that he wanted the flashlight directed straight ahead, that with the pressing of the button he would shoot.

A leaf that crackled jerked King's hand back to his rifle. With the maddening elusiveness of darkness it was impossible to tell whether the sound was farther away or closer than the convergence of the paths. King's rifle muzzle swung to cover the spot and his left hand reached desperately again to feel for the Masai's waist band in which the light was struck.

Normally the big fellow would have understood the first nudge. Had it been elephants or lions or crawling head hunters, he would have been standing with it ready to hand. But in the presence of ghosts the plain African of him rendered him witless. It was a tribute to his dogged loyalty to his master that he stood beside him at all, instead of with the Hottentot in a tree.

AS King felt for the light his rifle muzzle perforce wavered. It touched

something. Before his reaching hand could snap back to it a startled noise

sounded. A great paw smashed against the gun and whirled it from his

hand.

In the fractional flash of thought before action King experienced a rifleman's anguish at the clunk of its oiled mechanism into debris. In the next flash he ducked low from whatever might be swinging higher up and dived for the sound of the gun.

A yell came from the Masai. "We-weh! Auni, Bwana! Help! It has me!"

That was the first time in all their association together that King had heard that proud fighting man call for help. He sprang from where he was, arms and legs wide to grapple whatever might be. He hoped only that he might not impale himself on the Masai spear, and, tailing that, he hoped he might find it so that he would have a weapon.

The impact of landing on a welter of writhing limbs knocked a grunt from him. His arms grappled partly with a something of immense power and partly with the smooth form of the Masai. A flash of comfort was to feel the man's great muscles alive and strong in defense.

King clawed at the shagginess that whirled him about like a puppet. He himself could have given even the great Masai a tussle. But this thing plunged as enormously as something prehistoric. A great paw at his back hugged his wounded side excruciatingly close. Momentarily he expected the crunch of great teeth or the disemboweling slash of claws. If only he could see something to avoid, to attack! The best he could do in the enveloping blackness was to pound at the bulk with his fists. He smashed at it with all the strength that desperation gave him. Grunts came from the thing. Fending off with one hand, King was feeling for his hunting knife when his feet cartwheeled from under him and he was down.

On the ground he fought instinctively as the primitive things of the jungle fight, on his back, arms high to protect his throat, feet drawn up to guard his stomach. Sounds of fight threshed over him.

A weight lurched down on his feet. As lions do, he kicked mightily with both together. He did not know whose the weight might be, but he heaved with all his loins and back and thighs. The weight was too great for the Masai's, but King could move it. It staggered back and the lumpy thud of its fall sounded.

For the moment free! Both of them!

"The flashlight, fool!" King yelled and he dived again to grope for his rifle.

The Masai's voice brought a surge of thankfulness—only because it showed that he lived. What the voice panted smashed the moment of joy.

"The light, Bwana, is lost."

And then hopefulness surged back. The heavy padding feet—retreating!

"The moonlit patch!" The Hottentot's voice screamed from above. "In three breaths the ghost will pass through it!"

The pad, pad went faster.

"There!" shrilled the Hottentot.

And at the same moment came King's shout as his fingers touched metal.

"Awaie!" the Hottentot wailed. "How fearful a thing to see! My eyes fear to look!"

King's rifle was snapping to his shoulder as he rolled. He saw the thing lurch into the moon patch. A monstrous form, pale in the filtered glow and vaguely outlined in the leaf pattern. A something that moved, that was all. But great arms were discernible writhing upwards, and the thing ran on its hind feet like a man.

King's finger froze on the trigger. He held his fire for just that hesitant second. And then the thing was gone. Only sounds told that it ever had been.

All in the space of a fleeting second. So fleeting that it was lost in the blackness again before the Masai's superstitious anguish broke and the Hottentot's monkey chittering was not up in the tree, but grovelling about King's feet.

King got up slowly. He breathed hugely, looking after the thing's passing. Then, "Let's get out of here," he said shortly, and gave no other word until they were well out of the jungle.

"Eweh!" The Masai shook himself. "Jini wa 'Ngagi, The father spirit of all the great apes. Wah! It shall go down to my children that I, an Elmoran of the Masai, clung to that ghost with all my might until Bwana should find means to slay it."

"Oh?" said King. "You were clinging to it, were you? No wonder. And what did you see, Apeling?"

Kaffa the Hottentot had his own theology. "It was Heitzi Eibib, who created all the trees and growing things and who sometimes walks amongst them on the ground to see how his work prospers."

"Both of which," King said dryly, "are amongst the reasons why white men continue to dominate Africa."

HE said no more until he came to Hawkes' bungalow and hammered on the door.

Hawkes was as profuse with greeting and relief as his breeding would let him

express.

"Awf'ly glad you're back, old man. I've been thinking I shouldn't have let you go. Did you get it?"

"First," King said, "some government hospitality. A cup of your ghastly coffee to settle my ragged nerves, and then I'll talk."

Not till he had grimaced over a cup of acrid pale brown liquid did he satisfy Hawkes' insistent questioning with one word.

"Tarzan."

"You mean, the monster is a—You don't mean to tell me it's a man?"

"A man, and nothing else," King said positively. "But a great brute of a man. And a white man! As naked as a raw tusk, and as batty as a loon. What you got to say to that, Copper, in your district where white men are few and you're supposed to know every one of them and everything that's going on?"

The surprise began to die out of Hawkes' face.

"A district as big as your Texas," he murmured. "But we do have a way of knowing what's going on, old fellow." He went to his desk and found a letter, a portentous thing with a crest on it, "If this chap is a man, he must be Mister Carlo Bentinck's gorilla man. But what he's doing, howling in the woods at night, I don't know, unless he escaped or something."

It was King's turn to stare. "What's Carlo Bentinck's gorilla man?"

"Mr. Carlo Bentinck," Hawkes' smile was very superior, "has a freak of some sort. He has offered a proposition of some sort to Sir Harry Jenks, and Sir Harry has asked me"—Hawkes' smile twisted wryly—"He has, er—ordered me to investigate Carlo before he considers doing business."

King snorted. "Huh, him? Just like a hang-bellied prince of industry to guard his pennies, looking up a man's record before making a deal, instead of just looking at his face and gambling on what he knows of men. And what right has a tourist like him to go handing out orders to the local police?"

Hawkes stiffened. "He's a very important person, old man. Got oodles of oof, you know. And the last birthday honors list made him Sir Harry."

King snorted again. "You chums sure have a knack of keeping the rest of the world guessing. Here's you with your whole system based on a hereditary aristocracy, and you take some lard by-products champion and think to add him to the high hat list by giving him a title. A crest on his letter head. Pah! What is it? A hog on a dinner plate?"

Hawkes was dutifully shocked. "Oh, I say, old chap. That's laying it on a bit thick, don't you think?"

"All right, all right," King grumbled. "Only I heard how he fired Tommy Ansell, as good a guide as you got in the land, for not agreeing with him fast enough. What's this deal that a freak manager has with your birthday aristocrat?"

"I don't really know. Sir Harry didn't condescend to tell me—just ordered me to investigate this Carlo fellow. Had to admit I could find out nothing on short notice, so he asked me to be present at the meeting and look him over."

"And," said King, "you'll take me along. Since I came damn near to shooting his new freak last night I'm interested enough to see your Sir High Hat take over the management and stick him a fat price for going out and bringing his pet back alive."

"Oh it's nothing like that," Hawkes said. "I mean, not a freak show. It's something or other about some medicinal product, as far as I could gather. Dashed mysterious and all. Matter of fact, old chap, I would like you to come along and give me your opinion."

THE little hotel, as every patriotic one should, contained a "royal suite," and in it was Sir Harry Jenks. Sir Harry received Hawkes with a studied dignity and just a little more aloofness than his superior officer might have affected. At King's informal attire he raised bushy, graying eyebrows.

"My deputy, sir," Hawkes explained.

King's eyelids flickered and the side of his face towards Hawkes grinned.

"The Bentinck person," Sir Harry drawled, "is waiting somewhere about the place with his prodigy. I'll 'ave—" He replaced the h with an effort—"I shall have him summoned."

King stiffened to interest. "With his critter, you say?"

Sir Harry's eyes stared at King over their well-fed pouches without reply.

A brisk footstep sounded in the hallway, overlaid by a ponderous shuffling of dragged feet. A brisk knock, and an alert, sparely built man entered. But neither King nor Hawkes looked at him. Their eyes hung on the mountainous thing that shambled after him.

An immense man. By no means the freak that King had expected, no throwback to the anthropoid. His arms and legs under loose drill shirt and pants were in proportion to shoulders that almost filled the doorway. Just one great brute of a man. Only his eyes were dull under lowered lids and his heavy face was blankly without expression.

Sir Harry's only introduction was: "The local police. You will please repeat to them what you told me."

King examined the Bentinck man now. A wiry figure, swarthy and well bronzed, with a nervously intense manner. A man who had obviously been places and knew how to take care of himself. But his nervousness was in no way occasioned by the presence of the police. He smiled confidently at them with strong, even teeth and produced, first, a photograph.

"Observe, please, this picture, gentlemen."

It was a picture of a big boned man, tall and cadaverous; as tall as the huge fellow, a good six foot six. Only in his leanness he looked even taller.

"That was taken six years ago." Bentinck said. "Now look at Hermann here. Hermann," he commanded sharply. "Look this way."

The huge fellow lifted his head and turned lack-luster eyes on the police. Bentinck smiled on them and nodded his anticipation of their agreement.

"The same, is it not? No question about that, is there? Right. Now let me show you. Hermann. Attention! Show strength. Strong, understand? Show." He flexed his own arms to make his meaning clear.

The dull eyes looked slowly away and about the room. Then a long arm reached out with the vast deliberation of a giant sloth and picked up a heavy chair as easily as though it were a pillow.

"Not that!" Bentinck shouted.

But the slow brain impulses had been started. The great hands and shoulders, as slowly as the mind that actuated them, bunched to exert a twisting pressure. The chair cracked like tree limbs in a hurricane and came apart in those tremendous hands.

"Bad, Hermann!" Bentinck scolded. "Sit down! Very bad! I am now compelled to pay for that."

Hermann slowly subsided, a look of hurt incomprehension on his face. Bentinck's smile was triumphant.

"Now, gentlemen, you will be asking how that can happen in six short years, and I shall tell you. But first I shall ask you this: Both of you have observed monkeys, is it not—even the great apes, perhaps. Yes? You know then that a chimpanzee of fifty pounds is stronger than a grown man. You should not care to have to fight one. No. I ask you, then, why? I ask you, what is it that supplies to the apes a vitality and a muscular development so far in excess of human attainment?"

The strong white teeth flashed.

"I will tell you why, gentlemen—because of an element in their diet that civilized humanity lacks."

He let the thought sink in while he took another breath. "There can be no question in the face of patent fact. The cave man could hold his own with his anthropoid cousin. It is civilized man who has lost that vital element. And I, gentlemen, I have rediscovered it!" He flung his hand to point out Hermann. "The proof!" He leaned forward and his voice dropped to punctuated solemnity. "In six years!"

HE stood back to survey his audience. His outflung hand swept the room. "And,

gentlemen, I believe—I hope—that Sir Harry Jenks, with his wide

experience of business, has the vision to see the commercial value of this

vital element, properly exploited and placed upon the market. Not only the

strength of the gorillas can be built up in man—but the vitality, the

tireless energy that civilization has sapped from man, restored. Consider but

for a moment the possibilities." He bowed towards Sir Harry. "To you, sir, I

do not need to point them out. Just the discovery of this vital element, eh,

in a great advertising campaign for a breakfast cereal?"

Sir Harry nodded. It was easy to see that sales points were revolving in his mind. King's face remained angularly wooden.

Hawkes was struggling with an obvious question. Bentinck forestalled it.

"You are going to ask me why, then, do I offer to share so valuable a discovery? I will tell you the truth. I told you that I had rediscovered this element. The truth is that Hermann has discovered it, and I—" He struck his chest—"I have rediscovered Hermann!"

"You ought to take better care of so valuable a critter," King said curtly. "I came damned near to shooting him a couple nights back."

Hermann's overhung brows jerked and his dull eyes lit in a quick sidewise flash; then he slumped again in dull apathy.

Bentinck's hand flew to his lips.

"You nearly shot my Hermann when he was woods running, loose by the full moon? My poor Hermann, who cannot take care of himself?"

Explanation poured from him in a shaken voice. "Six years ago, gentlemen, Hermann and I were partners, prospecting. We lost one another. At that time he was as you see him in the photograph. Then he was—" Bentinck tapped his own head—"the same as you and I. During that period, gentlemen—I do not yet know all the details, but Hermann has lived with the apes in the lost Kafu River country."

"Ha!" It burst from King. "In the country of the One-Eyed Juju."

Bentinck whirled on him. "You know that country?"

"Only the edges." King said. "Never went in, account of hostile natives."

"But then you understand perfectly." Bentinck's teeth flashed. "And you can substantiate my statement. To go in there requires, frankly, a strong party. When I found my poor Hermann again, gentlemen, he led me back to that country. But—" He shrugged. "As you might well know, I was driven out. We got away with barely our skins. But I have seen it, gentlemen." Bentinck's voice rose, "I have even tasted this element that builds such vitality—a leaf, not unlike tea or coffee. It is prolific. It is—" His hands fell to his sides; he swung to face Sir Harry, his voice quiet and appealing. "I do not have to tell you, sir, that such a medicament is worth money. You yourself are better able to judge of its commercial possibilities than am I. And there it lies. It requires, first investigation, then development." Bentinck flung wide his arms in surrender. "It needs the financing of a safari."

Sir Harry nodded in full understanding. He said: "I am inclined to go into the matter with you. Er—on a business basis, of course. I shall give you my answer tomorrow. You may go now. And take your—" He pointed a thick finger at the indescribable Hermann, turned to Hawkes. "And you will also give me your opinions tomorrow. That is all."

"WELL?" Hawkes demanded. "What d'you make of it all? Is there any such bally

stuff?"

King shrugged. "I'd bet ten to one against it. But don't ask me to say what fantastic thing can be in Africa and what can't."

"What do you make of the blighter, then?"

King turned the question back. "You're the sleuth. What do you?"

"Well, the fellow is a foreigner of some sort, in spite of his good English, and I don't trust any of those chappies until I know something more about 'em."

"Old Johnny Bull." King twisted a sour face over the strong tea. "Fellow's a foreigner, not of the good old stock. Hang him."

"Well then, my dear fellow, if you judge people only by their face, what do you think?"

"He's not a fool. And he's got his guts. And he's a good actor and a showman. All of which, if he's cooking snake meat, could mean grief for the guests."

"Humph! Sort of cheering news for the police, what?"

"I'll tell you something less cheering. Did you notice Tarzan wake up when I said I nearly shot him? He understood that fast enough."

"By jove! No! What d'you think that might mean?"

"Nothing—yet. But if it was a publicity stunt to catch our Harry's attention, and if our Hermie should happen to be a good actor too; then that lad with that kind of a face and those gorilla-food muscles, could mean howling murder in some of its messier forms. And I'll tell you something else. Your Sir High-opera-hat Harry is sold up to his neck to go in on this proposition, and his asking your opinion is only so he can blame all the mishaps on the office boy."

Hawkes sat sucking in the ends of his military moustache. "I'm afraid so, old man. And the deuce of it is we can't afford to let him run into danger; he's a frightfully important personage."

"You can't stop those big money boys," King said callously. "Not when they smell a promotion racket with a chance for big sucker dough. I'll bet you right now that our friend Harry is fixing to go on this expedition."

Hawkes shook his head. "Good Lord! We can't afford to let him get hurt." He sat drumming the fingers of his unwounded arm on his chair. "Dash it all. If I wasn't out of commission I'd go along myself. But—"

"No you don't," King shouted. "You don't get me to go pulling any hot chestnuts out of any African fire for your development of colonial industries."

Hawkes, in his staunch conception of service to Empire, could see not a thing preposterous in such an idea. "But damn it all, my dear fellow, don't you see if he gets into that Kafu country he might get himself—" Hawkes wouldn't put the appalling thought into words.

"Sure he will," King said complacently. "Fires a good man like Tommy Ansell, who might have kept him out of trouble. So he'll go with these con artists. And if they know enough to show him a juju sign of monkey skull and snake skin that says, 'Hurry up and stay outa here,' he'll pooh-pooh it and barge on through. Nobody can keep him out; he barges right into prime ministers' offices. So he'll get a spear shoved through his middle, and little loss to the world. I know a lot of honest spear shovers I like better'n him."

Hawkes pointed his finger at King and crooked the thumb beneath it like a gun. "Bango, old chap. You've said it yourself. That's exactly what would happen."

"And so what? I've seen it happen to better men in Africa."

"So—" Hawkes punctuated his points, throwing down his pointing finger as though shooting directly between King's eyes—"we'd have to send in troops. I tell you he rates jolly near as important as visiting royalty. If they should do him in, it would mean a punitive expedition. You've seen 'em, haven't you?"

"You bet I have." King's cheerful complacency vanished in indignation. "A thousand dumb blacks mowed down with machine-guns, because some hang-bellied prince of finance is close enough to a tin god to rate his profits like a national religion. Damn, I've done my share, but I've done it alone; no blasted army to come mopping up after my hard luck."

"And," Hawkes added, "after the army, a ten-year hang-over of hate before a man like you can trade that district again."

King sat scowling over the veranda rail.

"And," Hawkes put in gently, "if this chappie comes to grief while he's in my hands, may career is shot. I may as well fold up and go home."

King transferred his scowl to Hawkes. Hawkes' eyes held his.

"I'll give you," said Hawkes, "two native constables as escort, and Sir Harry already knows you as my deputy."

"Two!" King's derision flared. "Two whole constables to nursemaid a tin godling through a thousand square miles of hostile territory! What d'you think I am—a Texas Ranger?"

"I don't know your Texas Rangers." Hawkes said. "But our South African Constabulary have handled as big a situation."

King's scowl worked all around his face. "They have, huh?" His jaw muscles chewed on that. "But they had official authority."

"You'll have authority. My deputy. Emergency situation and all that. Needs a white man leader."

KING'S jaw muscles bunched. Then it came from him vindictively. "Listen,

Copper. If I'm crazy enough to do this for you, if I ever drag that slob out

alive, I'll expect absolution in advance for a list of crimes against your

silly government it'll take me ten years to catch up with." He nodded a

certain satisfaction at the prospect. "And I won't do it for your blasted

colonial prestige either, nor for your precious plutocrat. I'll do it so a

thousand naked spearmen won't get cut in half by machine-guns. And for just

one other reason."

Hawks suspected an admission of friendly sentiment and he shrank Britishly from it with a face already reddening. "Oh, I say, my dear chap. Don't say you would do it on my account. What I mean, a fellow doesn't talk about—"

"Yeah, on your account," King said grimly. "And for nothing else. Because this district needs a copper just like you—a stiff-necked, duty-ridden dumb one that I can slip things over on easy."

Hawkes reached out the hand that was not strapped to his side. "I'll give you the same two native constables that you rescued from that slave gang. They'd die for you."

"And that's a truth," King growled. "They likely enough will—"

"And I'll give you this." Hawkes pulled open a drawer and shook moth balls from a uniform jacket. "It'll be a bit tight over your shoulders, but—proof of your authority." With a tinge of pride he added, "Something that's known all over Africa."

King only laughed sourly "White man juju, huh? Maybe I'll hang it on a pole for the black boys to come and pray to. Crazy business. Me on your side the fence. Hah!"

"AN escort, eh?" Sir Harry raised his bushy brows at Hawkes. "Is that necessary?"

"Unsettled country, sir." Hawkes said. "And since you insist on going, we thought—"

Sir Harry cleared his throat and his sharp eyes made it quite clear that what Hawkes thought didn't matter. "Under command of your deputy fellow, eh? I suppose he'll take his orders from me."

Hawkes showed his national diplomacy. "Best man in the country, sir. I really ought to take charge myself, but—" He indicated his bandaged shoulder.

"Oh, of course, Captain." Sir Harry inclined his somewhat mottled face in perfect understanding. "Well, I suppose the man and I will get along all right." He said that in the certain tone of an executive with whom everybody in his entourage had always very carefully got along.

At about the same time Mister Carlo Bentinck was saying just about the same thing to King.

"An escort? So the police think it is advisable, yes?"

"That's the orders," King said cryptically. "His Nibs is an important pillar of the home aristocracy."

There was something about it that didn't hit quite the proper angle of respect.

"Regular force?" Bentinck asked shrewdly.

"Nope. Special deputy. Emergency case. His Nibs pays the extra grub wide and handsome."

"Ah!" Bentinck appraised the don't-give-a-damn grin on King's face, his distinctly "informal" uniform of khaki shooting coat and military puttees. "Ah! I think we shall get along."

"I get along with anybody who knows more'n I do," King said. "And with anybody who knows less and admits it. So I'm checking up on your safari equipment."

"Oh, certainly." Bentinck was confident about that.

"You bought a Jeffries .475 for him, I know. At a fancy price. It'll kick him endways if he ever shoots it off, but that's okay by me. And you billed him for two others, new, though they're seconds left over from the Pajet expedition."

Bentinck watched King as warily as a wolf. "You know about that?"

"We have a way," King said loftily, "of knowing what's going on." He was getting a ribald enjoyment out of his unwonted association with the Law. "One rifle is an extra, I suppose, 'cause you've hired no other gunners and Hermie doesn't shoot."

The Hermann creature was sitting, enormously inert, on the tailboard of a truck, admiring with the fondness of a butcher a tool that he fondled in his lap, a shiny new broad axe of the largest size that came.

"No," Bentinck admitted. "Hermann does not shoot."

"And looks like he don't need to," King said dryly. "And you bought two trucks, seconds, from Tommy Ansell at the top price too. That's not my worry. What you stick a financial wizard who knows too much to take advice is none of my business."

Bentinck nodded appreciation of so much understanding. "I am sure we shall get along."

"There's a chance of that too," King said. "But lemme advise you. If you want to get along with our fat friend you'd better pick a good cook and some snappy camp boys. Let's look at your grub list. When I'm on my own I travel lean. But here's the first time in my life the aristocracy feeds me."

SAFARI, that so grandiloquent term insisted upon by rich sports and cynically acquiesced to by guides, is no longer a picturesque affair of a hundred black porters carrying little bundles on their heads, winding like mottled snakes over the vast African plains. It is a practical de luxe affair of trucks with strengthened springs that can leave the roads and lurch away over ant hills and roots as sturdily almost as a caterpillar tractor.

White men jounce on the front seats. African camp boys cling precariously wherever piled tents and food crates permit.

The old hazard of water holes has been eliminated by machinery that can carry water by the hogshead. The only "roughing it" left comes of having to sleep in tents where doors cannot be locked against prowling carnivora.

Yet Sir Harry found room for complaint. He complained because it was not fitting that the Masai and Hottentot, with the efficiency of long practice, had King's personal tent pitched and old kerosene can of water heated, and King was lounging his length on a cot, bath and luxuriating with a pipe, while Sir Harry's own canvas still billowed in the evening wind under the astoundingly inept hands of tourist camp boys.

Fuming, he called to King from where he stood under a mimosa tree. Leisurely King got off his cot and obliged, his pipe still in the corner of his mouth.

"I say, my man," Sir Harry snapped. "Your fellows seem to have more experience in all this."

King smiled benignly. "They're good. About the best in Africa. Though Ansell has some pretty near as good."

"Well, damn it, why don't they help?" he demanded.

King shook his head. "They're just escort. They and the two constables and me, we're just along to see that nobody bops you on the head."

Sir Harry stared at King, while the mottled grayness of his cheeks reddened with the fury of a man whose mere suggestions had always constituted an order. And then—give him credit—he called for no outside help.

"Damn your impudence, you bounder!" he shouted and he aimed a furious swipe at King's head.

Without removing his pipe, King slipped his head under the savage swing, stepped in and pinioned Sir Harry's arms above both elbows. He grinned at him.

"Takes practice," he said. "You don't get it in a director's office." He gripped the elbows with his thumbs excruciatingly in the soft hollows until Sir Harry's futile struggles ceased. Then he let go and stepped back.

Even through his rage Sir Harry recognized the uselessness of repetition. It had never in his life occurred to him that anything so blasphemous as retaliation could happen to him. He swallowed many times before his splutter came through, strangling in his throat.

"I'll have you dismissed from the force for this, you ruffian."

King remained astonishingly cheerful in the face of the tirade.

"True to form," he said. "Only that's one you just can't do."

Sir Harry didn't understand the irony of that situation. He fumed.

"I'll turn back immediately and obtain more efficient servants."

King nodded. "Yeah, you could do that. Only I don't know whether your safari conductor would want to now, four days out an' all."

The thought was a sobering shock to Sir Harry. He swung startled eyes to Bentinck, half expecting to see him already hastening to his help.

Bentinck was bending over some camp gear, studiously avoiding any interference.

That the loyalty of his hirelings could ever be in doubt was another horrid experience to Sir Harry. The first moment of it awed him as though it were a phenomenon reversing all the forces of Nature.

"Would the fellow dare to—would 'e 'ave the bloody himpudence to mutiny?" Sir Harry's carefully acquired aitches reverted, in his agitation, to their original chaos.

"I wouldn't know," King said gravely. "You didn't consult the police when you fixed up your safari arrangements with him."

The police! Law and Order! The things that Sir Harry had almost forgotten in his mighty career as being the forces that backed up his authority, away back in his sheltered civilization. He whirled back on King with a Briton's stout reliance on service.

"You scoundrel. You're supposed to represent the Law."

"Sure do," King grinned at him. "Got my juju right in my blanket roll there. You just appeal to the Law that you want to go home and I'll take you back if I have to shoot up the camp. That's all I'm here for, to bring you back alive; and nobody'd be more pleased than me, mister, that I'd be through with the chore that easy. Only—"

"Only what?" Sir Harry's business instinct remained wary of unforseen contingencies.

"Only there would go all your chances of your monkey food. The Law can't order Hermie to guide you."

Sir Harry digested that thought in sulky silence. Then the driving force of his life, business profits, took its normal ascendancy.

"I shall go on," he said doggedly.

"Okay by me," said King. "I'm only escort."

HE went back to his own tent and did a thing most undignified for the majesty

of the law. He hunkered down beside the little fire with his men. The Masai

took a horn container from the lobe of his ear and out of it tapped a pinch

of snuff upon his great spear blade and reached it across the fire. King took

a few grains and went through the motion of sniffing. It was a sign that this

was an informal fireside chat, off the record.

"If Bwana had but called," the Masai growled, "with a throwing spear I would from here have nailed that disrespectful one to the tree."

"And so would have caused much trouble, Barounggo, old blood-letter," King said. "Here is wit needed. Kaffa, what do you make of this trek after four days? Particularly of your Heitzi Eibib with his great axe?"

The two constables, who had not been through that fear, guffawed their superiority. The Hottentot scuffled his abashment and muttered: "So bellow the cattle, safe under their herd guard. As to that first born of 'Ngagi the great Ape Father, my observation tells me this: All this trail is new to him. He knows nothing of it. He leads us nowhere. But his keeper knows."

"Ah!" said King. "So I have thought. But that is perhaps because that great one's wit is no greater than his brother ape."

"Nay, Bwana. A little, though not much greater, than an ape's." The little imp scuttled around to the other side of the fire. "For he, too, can use speech."

"Ha! That's what I've been trying to find out. How do you know that?"

"In the night, Bwana, I have lain close beside their tent flap, and I have heard him talk softly with his keeper as men talk who have secrets, only in a language that I do not know."

King stared, narrow-eyed, into the fire, "What secret evil those two hatch we must find out. Yet have a care, Apeling. That keeper is no greenhorn. Awake, he might have heard you."

The Hottentot chittered the triumph of a monkey that has escaped the penalty of its inveterate inquisitiveness. "It is the other one who has the ears of an animal. Last night that ox suddenly burst forth and nearly set his great foot on me. But when did the buffalo ever catch the 'ngedere monkey that sees by night? From under his very hooves I fled."

"Oho! So that was that noise. Watch it, Little Wise One, watch it. That axe blade would span your belly in one stroke."

The Hottentot remained careless. "So long as it is not a ghost, Bwana, my belly does not turn to water and loosen my limbs."

"Watch it none the less, Apeling, and the three of you besides. It is up to the policea chief Hawkes' honor that we bring this stubborn man of much money and no knowledge back alive."

WHILE camp boys frittered away the usual two hours or so over getting gear

stowed, King talked with Bentinck, who ought to have had it stowed an hour

ago.

"W'hereabouts d'you aim to hit this Kafu jungle? There's quite a belt of it."

"Wherever Hermann leads to, of course," Bentinck said.

"Looked to me like he wasn't leading any place," King said bluntly. "Seemed like all this territory was new to him."

Bentinck studied King from out the corner of one eye. He said:

"My poor Hermann. No, he does not with deliberation lead. He retraces rather his path by an unreasoning instinct almost of an animal."

"I've seen animals get lost when they're being chased out of a district."

Bentinck's white teeth flashed. "In this case it would not matter so much, for we must at the last come to a Kafu tributary on the south bank called the Inridi. It is not on the map."

"Oho! You got quite a ways into the juju country before they chased you out. Why shove so far into trouble? Is your valuable stuff found only there?"

"Yes." Bentinck's teeth were avid. "It is found only there."

"Then if you know the place, why drag Hermie along?"

That should have been a poser. But Bentinck smiled up at King and King knew that it was a polite refusal to disclose secrets.

"My friend, by the time I get to that Kafu tributary I might have forgotten all about that valuable leaf—I mean, the appearance and the taste of it."

King looked at the man and smiled too, though through thin lips.

"What you mean is it's none of my business."

Bentinck shrugged.

"Why could it not mean, my friend, that you said you could get along with anybody who knew more than you; and so I maintain myself just a little bit ahead." His laugh was almost a challenge.

But not to anything so absurd as physical combat. King knew that. And for the present he preferred to let things rest.

THE Hottentot's sleuthing was not much more successful, though much more

troublesome. It was his ineradicable urge to pit the keenness of his wit

against massive brawn that impelled him to the perilous business of trying to

draw out Hermann.

He busied himself in company with the camp boys. His reasoning was that if Hermann knew any of the African dialects, one might begin to get a line on Hermann. His technique was crude but effectively simple. With one wary eye on Hermann he made derogatory remarks about him in Swahili. He used the commonest words that every white man learns within his first month, because he must call them at blundering servants. Mkombokombu, great lout, and mpumbafu, half-wit—with an acrid tongue he applied the terms to Hermann, who sat with the lowering vacancy of a none too great intellect on his countenance, nursing the great broad-axe.

Hermann's face remained blank to Swahili. But the camp boys laughed hugely at the crude wit. The Hottentot tried in Arabic, in Masai, in Zulu. He drew upon wherever his wanderings with his master had taken him and whatever vituperation he had added to his arsenal of acid speech that did him duty in place of other men's weapons.

Slow-witted Hermann was, but not so foolish as to remain heedless to the covert looks of the camp boys as they guffawed and not so dull as not to know that he was being laughed at, nor yet so without reason as not to guess that this obtrusive little imp might well be the eavesdropper of two nights ago.

Yet close enough to all three was Hermann to be ever suspicious of ridicule and accordingly ungovernable in animal rage.

The first that King knew was Kaffa's shrill screech of fear, and as he whirled in instant defense to the call, there was the Hottentot racing over the plain, and after him Hermann, with his great axe.

Like a frantic baboon the Hottentot ran, hopping from one high grass tussock to the next, dodging round tall ant hills, his wisp of blanket trailing in the wind, shrieking in his extremity. Hermann like a vengeful buffalo lunged behind him, making enormous swipes with his axe.

King's rifle was at his back, hung from his left shoulder by its sling. He jerked his shoulder with an expert movement and the rifle made a neat, close half circle around the shoulder and smacked into his left hand; his right in the same smooth movement snatched the bolt out and back. He stood so, watchful, set like a tempered spring to act.

Bentinck, standing beside him, was almost as fast. His right hand slid under his shirt and he held it so, watching not the impending murder on the plain, but King's every move.

King's eyes remained grimly on the runners, his rifle half raised, like a ready skeet shooter. But out of the corner of his mouth he said to Bentinck:

"Just try drawing it, feller, and see if, among all the other things, you know more about guns than I do."

Bentinck's eyes flicked from King's granite profile to his taut shoulders, to his hands, fully occupied with his rifle, too close to swing the muzzle round. He tried it.

King's eyes never left the racing men, nor his rifle muzzle their direction. But he snatched a second to slam the butt back under his right arm. It thudded into Bentinck's chest and knocked him rolling. King couldn't see the full effect of it; but for all the possibility that the man might still be deadly, he dared not take his eyes off the death behind his racing Hottentot.

Protection to his servants was a creed that won for King a loyalty that many another Africander wondered at and envied; and King gambled now on the reciprocal service that he expected. His voice said to Bentinck, out of his sight:

"Before you try anything else, better look around and see if my Masai isn't in on the play somewhere."

The sheer cool confidence of it impelled Bentinck to do just as he was advised. He looked, and he lay very still.

A SCANT twenty feet from him the Masai poised, a splendid naked statue of a

javelin thrower in black marble. Legs wide, torso inclined, arm flung back,

his spear on a level with his ear. The morning sun threw silky high lights

from his great muscles and glinted silvery from the long blade.

The whole camp remained frozen in action as though a cog in a motion picture projector had jammed; the principal actors tense on the point of a single tooth, ready to go as soon as the gears might mesh, the supers staring white-eyed. Motionless, everybody.

The only objects that moved were the Hottentot and his pursuer, dwindling into the distance. And it was distance that released the action, distance and stamina. The little Hottentot drew away from the lumbering Goliath. Goliath slowed down, came to a stop. The Hottentot pranced on a tall ant hill and screeched vituperation at him.

King lowered his rifle and his smile broke tightly round his mouth.

"Whau!" The Masai intoned his deep exclamation that signified satisfaction over any happening, whether a good meal or a killing, and he came to life.

Bentinck got up slowly. He said to King, "I admit it—you know more about guns than I do."

"Meaning you want to get along?"

Bentinck nodded. "You and I, if we could but once come to an understanding, could make a profit out of this. No hard feelings, yes?"

"Nary one—yet," said King. "Not over a thing like this. It's just Africa."

"Then tell me." Bentinck asked. "So that I may understand. Would you have shot Hermann?"

There was not a flicker of evasion on King's face.

"Sure thing," he said. "My Hottentot looks like a monkey but he's a whole little heap of man; and your Hermie looks like a man but—" He looked at Bentinck without any hint of a smile. "You said yourself he was pretty close to an animal."

Bentinck stared at him, perplexed. "You are very difficult to understand, my friend,"

King grinned cheerfully at his perplexity. "Stick with your game, guy, and you may find out sometime." He turned from him and went to the Masai.

"That was well and readily done, old warrior," he said. "There will be a gift of a cow for your father's kraal. And our Apeling will thank you for saving him from his ghost, from whom he hoped to make his honor clean by entrapping it into speech."

"Whau!" the Masai said. "It was a little thing, Bwana, to have open eyes in the daylight and to be ready. As for that great ghost—" He stopped to scratch thoughtfully at the side of his neck with his yard of spear blade—"I, too, have an honor to make clean with him."

Bentinck came up. He said: "One more thing I admit. You have more experience than I in picking a way through the easiest ground. Do you, then, lead with your truck and Sir Jenks. I will tell you which way to go."

"You won't have to," King said. "I know the best way to your Inridi tributary of the Kafu."

Sir Harry stood looking on at these doings, for the first time in his life a silent bystander. His mottled shadings stood out against the whiteness of his cheeks likes daubs of gray paint. The closeness of sudden death and the casualness of it left him, for the first time too, with no orders to give. But—grant him always his meager credit—he did not say that he wanted to go home.

KING accordingly drove the lead truck, picking out ground by guess and by

that observation of shrubbery growths a mile ahead that makes a sixth sense

for the traveler of the veldt, until out of the wilderness there appeared a

trail.

King swung into it and headed north. A mile behind him Bentinck's truck hooted and tooted frantic signals until King stopped. Bentinck was red-eyed with angry suspicion. Beside him Hermann sat, brows drawn heavy over his little eyes in a scowl that was a murderous threat.

King grinned at the obvious betrayal of intelligence.

"Looks like Hermie's animal instinct feels we're headed wrong."

Hermann's insensate rage very nearly overcame his acting. His mouth opened to blaze forth words. But Bentinck clapped his hand over the big man's mouth.

"What the hell game are you playing here?" he snarled. "The Kafu jungle is due west and you know it."

"Sure," King agreed. "A hundred miles of it. We'd have to leave the trucks and crawl afoot. But you don't want just jungle. Your funny tea leaves happen in just one spot, and getting there is something else I know better'n you. Here's a government road; it'll cross the Kafu at a ford. I'll turn east along the north bank where the map shows no jungle and I'll ferry you across at the Inridi in a canoe, slam into your juju country."

Bentinck said, "You can't. The natives are hostile; they keep their canoes hidden, sunk with rocks. That is one thing I know if you do not. I have been there."

"And I never have," King said. "But somebody will loan me a canoe." He grinned. "'Cause I'll get me a letter of introduction." He grinned wider, pointed his thumb to Sir Harry beside him. "But this isn't my safari; I'm not running it into any juju sacrifices to make a business profit. I'm only escort to see that the boss here gets out of it alive. Ask him what way he wants to go."

Sir Harry rose to his own life-long habit of decision. He said to King: "You are the most insolent man I have ever met. But I believe you can do what you say."

King flipped his hand in a derisive salute to Bentinck and meshed his gears.

Sir Harry sat in a stiff silence, too lofty to inquire what might be this extravagant mystery of so civilized a thing as a letter of introduction in the savage back land of Africa. But Kaffa, crouching behind on the angle of a chop box, chattered his eager intuition.

"Bwana goes to visit the witch doctor of the Kafu ford?"

King nodded into the heat haze ahead of him. "If there is one there, as I have heard."

"I too have so heard. A little one. Not like our Great One of Elgon. But to a friend of the Great One this one will disclose the hidden things."

"And hidden things are here that need disclosing. Those two are playing some monkey business about this juju country that doesn't mean any good to anybody else but themselves." He drove on, and the farther he went the harder the lines of his frown.

THE wizard of the Kafu ford lived on a hill; the transparent reason for which was that he might observe all comers and prepare his hocus-pocus for their bewilderment.

King took the Hottentot with him. They marched without subterfuge to the sign that said, "No admittance except on business." It said so by means of seven snake skins and an antelope skull attached to a tree with the horns pointed toward the oncomer's breast.

King knew enough of witch doctor etiquette not to push through. He sent the Hottentot ahead.

"Give him this blanket and the tobacco," he directed. "And pay him what compliments your wit may devise—and show him the carving that the Great One put on my pipe."

He sat down to wait while the Hottentot commenced the tedious business of crawling forward on all fours, beating his head on the ground and shouting the bonga ritual of praise.

Normally a witch doctor's dignity demands that his visitors be kept waiting over a period of time graded very carefully according to their rank, which is judged by the number of their followers. A man arriving with one scrawny Hottentot rated about two days of delay. But within five minutes the wizard appeared at the door of his hut. He made no hocus-pocus. He shouted as man to human man words that he had never spoken before.

"Karib, Mzungu. Be welcome, white man."

The witch doctor was not togged out in his professional paraphernalia of bones and dried reptiles and charms. He appeared as an ordinary human with keenly intelligent eyes in a shrewd old face.

With his own hands he set a three-legged stool for his guest in the shade of his hut and squatted simply beside it.

"My women will bring mealie beer," he said. "Honor has fallen upon me that the Great One of Elgon knows even my name."

King wondered just what fantastic inventions the Hottentot had woven into his complimentary message.

"To a friend of that Great One's," the wizard said naively, "since he sends me so good a blanket by the hand of his friend, I will tell the truth."

"A truth is what I need," King said. "About that juju country of the Inridi mouth."

"Ow!" said the wizard. "Mzungu would visit the country of the One-Eyed Juju?"

"A fool," said King, "led by a knave goes there. I go as guardian to the fool."

"Wo-we! That will be a difficult guarding. For the people of the juju have a feud against white men."

"So I have heard. Since a year ago, before which they were not unfriendly. Why then a feud?"

"Because a white man stole the juju. It was said that he was a doctor of white men's knowledge and he wanted to display it in a house where white men keep many strange things for their students to look at."

King muttered his disgust to himself. Same old story. Scientists, missionaries, what not, good Christians all, think because it's a naked savage's god it's something to swipe and stick in a museum. And then they yell for soldiers when the savage retaliates and sticks a white man's head on a bamboo juju pole.

The wizard understood none of it, but his trade was to read men's thoughts. He said: "Yes, the people of the juju were very angry; because it was a very good juju made of a black stone and it could talk."

King raised an eyebrow at that.

"Or at least," the wizard chuckled, "its head priest could talk from his stomach."

"Have there been killings yet?" King asked. "I mean, white men?"

But that was one thing no black man would tell a white man. The wizard said, "I do not know." And King knew perfectly well what he meant. He said:

"Tell me then another thing. Is there a leaf in that country that the great apes eat to make them strong?"

The wizard laughed. "It is a tale told by mothers to their children to make them eat foods that are tasteless. 'Look,' they say, 'the medicine is in the food and you will grow strong.' And the children, being inexperienced, do not know that it is the talent of women to gain their ends through lies. But foolish men believe the tale and come looking for that medicine. Yet, if there were such a medicine, I would surely have it and I would be greater than the Great One of Elgon."

"My fool believes the tale and comes looking, hoping to be greater than the great ones of his land."

The wizard spoke another truth out of his observation of men. "What a fool believes, he believes with all of a fool's stubbornness, and if there be a profit in the belief, even wise men become fools. Yet a knave cannot be a fool. What does the knave come looking for that is worth the risk of that juju country?"

"That is the truth that I hoped to find here," King growled.

"Aie, Mzungu! To read the evil in the mind of a man I have never seen is beyond my poor magic. The Great One of Elgon, perhaps. Not I. Ask easier things of me."

King stood up and shook himself, not entirely disappointed. "You have at least given me some information out of which truth may yet emerge. For the rest, since the knave has persuaded the fool there will be a profit, I'm afraid no talk of mine will stop us from going ahead and needing a canoe."

"I will send my silent voice out to those who can hear," the witch doctor said. "There will be a canoe. Kua heri, friend of the Great One of Elgon. My word is, go with care. My better word would be, slay the knave quickly before knavery brings death. But I know that white men have little wisdom in such a matter."

"Yeah," King said. "White man rules sure are a handicap when the other fellow hasn't any. Kua heri, Wizard. Send a good voice out for me."

THERE was a canoe. Whatever the wizard's methods of bush telegraph, the voice

traveled faster than the trucks. Native villages en route remained peaceable;

they even offered fowls and eggs for sale. King grinned at Bentinck's surly

surprise.

"Something you ought to cultivate, my friend—a good reputation to leave behind you."

And when the safari arrived at the spot opposite to the Inridi River's inflow, there floated a big dugout with two natives in it. They said:

"A word came that white men would pay a just price for a boat. The price is five sticks of tobacco."

King stood with his feet planted wide and his thumbs in his belt, facing Sir Harry. He said, "Well, here's the last call. Across a hundred yards of river is whatever you're going to get, and I'll tell you this: it won't be monkey food and it will be grief. Take it or leave it. My advice is to leave it."

Bentinck cut in angrily to forestall Sir Harry. "You know a lot suddenly, my too clever friend, do you not?"

"Yep, a whole lot," King said steadily. "But not quite everything—yet."

Sir Harry had been learning that King was not a man of false alarms or loose statement. He said, "I am inclined to listen to your judgment, if—"

Bentinck's darting eyes had already showed him that the Masai was fifty yards away, superintending the unloading of his master's baggage. The four white men stood along with just the two canoe men gawping at Hermann and his giant axe. In a frenzy of anxiety to forestall damning disclosures Bentinck flung the ultimate taunt, and his hand was ready under his shirt.

"So our bold escort is suddenly now afraid, now that we are on the brink of success."

King had lived his years through desperate situations by never doing the expected. He disappointed Bentinck by grinning coolly.

"Sure I'm afraid," he admitted, "Did you ever see a juju sacrifice?"

That was a turn of talk nearly as bad as disclosures. Bentinck appealed to the urge that had persuaded Sir Harry in the first instance.

"Do no let him fool you, sir. He is a man who draws just his day's pay whether he comes or goes. There is no profit in this for him. But for us, we are now here—we have a strong party. We—"

Sir Harry held up an authoritative hand. "Do not interrupt me again, either of you." He turned to King. "I was about to say I would be inclined to consider your objection if you would tell me where you obtained your information."

"The witch doctor two days back there told me."

Sir Harry first stared, and then smiled his disdain. "My good man! Really! The advice of a savage charlatan is hardly a sufficient reason to abandon a profitable business venture. We shall of course go on."

King shrugged. "Okay, mister. This isn't my safari. I'm only—" But he didn't finish that; he had said it often enough.

A DOZEN trips of the canoe ferried men and necessary baggage. Camp boys

grumbled at having to divide the gear into small head packs and become

porters. A weed-grown path, long disused, twisted from the sand spit into the

jungle, following the general trend of the Inridi bank.

Kaffa loitered close to King and scratched aimless patterns on the sand with his toe. Only all the patterns aimed in the same direction—toward the jungle fringe across the river.

"Yes. I've seen 'em," King whispered. He moved away a short distance to where he could talk without the camp boys hearing and stampeding like bleating sheep. "How many, do you think?"

"Half a hundred, Bwana, and with spears."

"Huh. They don't waste time. Keep watch, Apeling, and tell Barounggo."

The two canoe men must have seen them too: they decided they wanted no connection with this white man party. With ape cunning they said no word, but slanted their canoe down the river; once on the other side, they brought no more baggage, but ducked around a bend and were gone.

For the first time on that safari King began to give orders. "Come along, you boys. Move your limbs there. Lift 'em; they aren't lead."

He herded them into the jungle path and then without question took the lead.

"Better set your gorilla to tail 'em and see there's no desertions," he told Bentinck.

Within a bare quarter mile the path, as could be expected, opened into a wide clearing. Dilapidated huts leaned drunkenly in its center. Deserted yam patches were overgrown with the yellow flowers of the mzabibu vine.

King took complete charge. "We camp right here,"

Bentinck said nothing. But Sir Harry resented the sudden assumption of authority.

"Why suddenly here?"

King was keyed up to alertness, in no mood to argue. He gave only acid reasons.

"Because I'm nobody's hired man. Because I've got a job with Captain Hawkes to get you out of here alive. Because we're here where your safari conductor said he had to come. So go ahead and ask him to show you his tea leaves. I'm going to be busy."

He plunged in amongst the camp boys, drove them to the clearing center, set them to clearing rubbish out of the most suitable huts, called Barrounggo to direct others in dismantling the outlying ones and piling the wreckage to make a stockade.

Whatever was Sir Harry's conference with Bentinck, he remained sufficiently dissatisfied to prefer King's advice. He came, almost friendly, at all events not condescending.

"Do you think there's danger?"

King remained grimly uncompromising. "There can always be danger in Africa. We came prepared for it, didn't we? We're strong enough—I think—to look after ourselves if we don't pull any fool boners."

"You think this is a good place?"

"The best. This is a ghost village."

"What is a ghost village? Why is it safe?"

"I never said it was safe. It's just the best we've got. Epidemic, catastrophe, something or other convinced the natives it was haunted by evil spirits. So they pulled out. Africa is full of ghost villages. Good thing about 'em is, nobody will come jumping us at night."

"They might by day?"

Sir Harry, King noted, was not cringing with nervous fear; he was asking sensible questions.

King shrugged. "They might. We'll have to make no mistakes."

"Well," Sir Harry said. "I'm not altogether a bad shot."

King fired a quickly commanding finger at him. "We don't want any fuss here if we can help it. Start shooting and that could be the boner that'd get us cleaned up. When I'm alone my hard luck is my own, but with you on my hands my hard luck would kick back on Hawkes. I don't know just what would happen to him; but I know damn well your army would come hopping down on these dumb savages with air bombs."

Sir Harry looked at King, puzzled.

"You are a very strange man," he said.

"Not strange." King's eyes were hot. "Just a plain guy of plain folks stock, and I never got so high, mister, that I could look down on the rest of 'em, whether white or black or yellow. These naked black boys have done nothing to us yet, and we—or some white man—has done plenty to them. White men have gone fighting crusades for no bigger a principle."

Perhaps back in his sumptuous offices in London, King's homely philosophy would have slid off the hard veneer of Sir Harry's back; but here in the jungle clearing, with death waiting possibly just beyond the tree fringe, he was many flights closer to earth. He stared at the hard angularity of King's face, and walked slowly away, his eyes thoughtful.

AND then there was dusk falling as though it had been poured out of a tar

barrel, the moon too late just now to break the solid shadows.

King made all the disposals of camp, set watchmen over little fires, told off his Masai and Hottentot to watch the watchmen, and showed the seriousness of it all by announcing that he would sit up and keep an eye on all of it.

In the camp's quietness Bentinck sat down beside King on a great flat topped log that had once been a dining table and siesta couch for its owners. He said:

"So we have arrived, yes. I do not yet understand you, but I am convinced that you and I should get along."

King grunted noncommittally.

"You and I are men much alike. We make our living by what we know of Africa and by what we dare."

"Hmh!"

"With what I know we could make a nice quick profit here."

King yawned, but his eyes narrowed. "Thought you'd picked Hermie for your strong-arm guy."

"Oh, Hermann has his use. But you also, my friend, are a very powerful man, and your intelligence makes the perfect combination for me that Hermann does not."

King filled his pipe very deliberately before he spoke. "A partnership, huh? What about your Sir Harry and your monkey food?"

"What if I told you there is no monkey food?"

King blew luxurious smoke from his pipe. "No news to me. You told me that when you said you might forget what it looked like, once you got here. And you told me something else right then, only you didn't know it—that you had a buried treasure here and you knew damn well if you came looking for financing for a treasure hunt you'd get the bum's rush. So you framed up this semi-scientific yarn that was new enough to catch your sucker. I'll hand it to you for a smart one."

"Oho! So you guessed that. You are smarter than I realized, my friend."

"Aw, not so much." King could not abide compliments. "I guessed at it pretty close and the witch doctor confirmed it."

"Ah! Just what did that witch doctor tell you?"

King pulled his nearly dead pipe to a thick mosquito smudge and said very coolly.

"Told me you swiped the juju."

Bentnick started visibly. "How could he tell you that?"

"Easy. Swiped a year ago. You were here a year ago. No white men here since. And this village, that has juju poles still standing, was deserted, from the looks of the growth, just about a year ago."

Bentnick was awed to a long silence. At last he said tightly:

"You know much indeed. Almost too much."

"Sure," King agreed cheerfully. "Almost everything. Only thing I don't know is where you buried it."

"Ah! So then I still have something to offer for a deal."

"On what basis?"

"Fifties. You and I."

"What's it worth?"

"I do not know. But—the One-Eyed Juju, you understand?"

King grunted. "So it was a case of plain loot, eh? The usual thing, I suppose? What was it? Diamond?"

"I think so." Bentinck's voice dropped at the drama of it. "As big as a pigeon egg! Only cemented in so hard, I had no time to get it out. The spears were close on my heels. We can get it—now—and get away in the canoe. We two."

"And Sir Harry? And your Hermie?"

The moon had come high enough to reveal the dim form by King's side. He could see it shrug.

"My dear friend! Dead weight. They can find their own way out of the mess. And if they are too stupid—" King could see the shoulders shrug beside him.

KING was not angry. Nobody could knock around Africa for long and not know

that the world was full of all kinds of people with all kinds of ideas.

"Pally," he said calmly, "you just can't understands I got a job here to deliver His Nibs safe, and another job to keep your head off a juju pole just so an army won't come to avenge worthless white man blood. And besides that, there's my Masai and Hottentot here, and—Aw, hell. It's outside of your range."

Bentinck was encouraged by King's calmness into further argument.

"Do not worry about me, my friend, I have been here before and came out with my skin."

"When you got here they were friends. Dumb clucks thought a white man was white."

Bentinck snarled to offense. "Do not practice your talent for insult on me, my so tough friend. I am not Sir Jenks. But I still offer you opportunity for your help. What do all these others and your two black men weigh against the stake—the fortune—of two smart men in Africa?"

King drew it out to emphasis. "Black men. But my men! Shucks, it'd take too long to explain so you'd see any of it. You'll even hate to give up your loot, won't you? But I'm telling you, fella, you'll have to. Because that's going to be the only way out a lot of killings."

"Give up my—" Bentinck jumped from the log and faced King, hunched forward, ready. "But do not talk like a fool, you who pretend to dislike so much some killing. Before I give up I will—"

King billowed smoke. "You won't. Not even a pot shot out of the dark. Because you need me to get you alive out of this mess that is so much worse than even you can realize."

Bentinck's right hand froze on his gun under his shirt; his left unconsciously went to feel the turn of his neck at the shoulder.

"Feeling kinda loose?" King could grin a sour satisfaction at that. "Well, just to ease your conscience so you can sleep, listen to those drums. Smart men in Africa ought to learn to read drums. I'm not that smart, but I know a war talk when I hear one. My bet is, by morning this place will be surrounded by a couple of thousand spearmen."

THE first glint of dawn showed that King was horribly right, for it glinted on bright metal all along the jungle fringe, waiting only for the ghosts to leave the haunted area.

"Guns!" King snapped. "Every gun in camp! You constables—catch any camp boys who have sense enough to hold one so it doesn't look like a broom and pass out the spares. Parade 'em around. Make a showing. And listen—" He directed his scowl particularly at the white men. "Blood spilled means retaliation, so get this very straight. Any fool who shoots before we have to—before I do—I'll put a bullet into him without batting an eye."

They could be seen now—dark forms behind every tree, some of them boldly in the open, not quite bold enough to be the first to start a rush against so many guns.

"As ugly a crowd as I've seen." King squinted narrow-eyed round the irregular tree wall, and scowled at Bentinck. "And they got a right to be. You know any prayers, just peel some off so they don't recognize you."

But Bentinck knew no prayers with that much power. They saw him, and the angry war cry lifted around the circle in the multi-toned baying of a pack that has run its long-sought quarry to earth. Some jumped up and down and howled their rage to the sky; the bolder ones made short little leaping rushes that needed only the support of a few to develop into a massed charge.

Bentinck's dry tongue ran across bloodless lips.

"You asked for it," King growled. "What d'you think these people are? Monkeys like your Hermie, to forget? Watch it, everybody! If they rush we'll just have to shoot it out."

The Masai knew his African psychology of personal challenge that holds with all primitive people. With superb arrogance he strode out and stalked in all his menacing nakedness within easy spear throw of the circle, stiff legged, like a lion daring the yapping lesser beasts, growling from his deep belly. Where a bold one leaped and yelled the loudest he poised, half crouched on wide splayed toes, and shook his great spear high.