RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

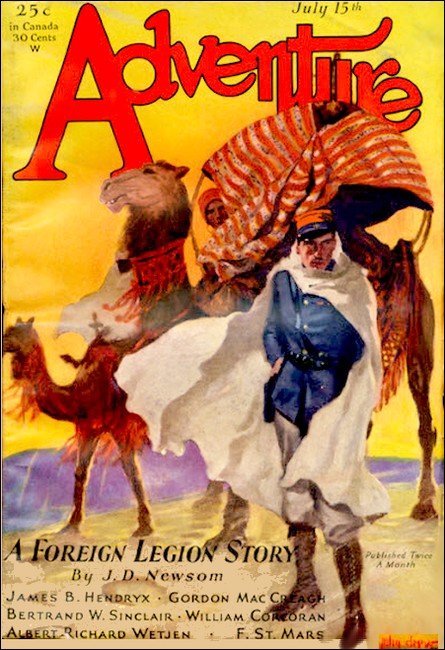

Adventure, April 1, 1930, with "The Ebony Ju-Ju"

THE tall brown man walked—prowled, rather—like one of the greater felidae, up and down the length of the sumptuous room. Brown from sun, he was; lean and hard from inquisitive interest in everything outdoors in all of Africa; and his eyes were narrow and puckered from long gazing over heat shimmery veld. One sinewy hand hung by its thumb from the belt of his riding breeches; the other swung a hippo hide whip from a thong. The soft soled bush boots made no sound as he stalked the polished floor, stepping over the strips of rich carpet as over obstacles.

This was King—hunter, trader, guide, prospector; anything that came along and remained out of doors. He was announcing as he prowled—

"I just can't take up your proposition."

The elderly, grizzled man watched him with head on one side, a wry smile under his clipped gray mustache. One hand drummed on the mahogany desk while the other toyed with a thin gold watch chain. He was dressed in the full formality of morning attire, which sat him with uncomfortable dignity.

This was Sir Harry Mountjoy Weldon, Governor of Kenya Colony, British East Africa. The sumptuous room was his office in Nairobi. He turned from watching the tall man and raised an eyebrow at a rather scandalized secretary. The immaculate young man immediately withdrew. The governor exhaled a breath, and with it let dignity out as from a balloon.

"Now look here, Kingi bwana," he said. "Think this thing over. There's some deviltry hatching up there and we've got to find out what it's all about and stop it before it comes to a killing."

King, too, relaxed from his nervous prowl.

"Governor bwana, I can't do it. Not but what it's a whole man's job that I'd like to look back on and feel that I'd pulled off. But, gosh almighty, I'd have to write a hundred page report about it and I'd have to make out an expense account down to the last cent and a daily mileage list and—Who's your man up there? Why can't he handle it?"

The governor smiled wryly again.

"Man called Fawcett. Assistant commissioner. A good youngster—maybe a couple of years behind you. But he's had only six years of Africa."

"Six years!" King exploded. "All I've had in the country is eight."

The governor smiled—wisely this time.

"Yes, but—you've had a different training. It takes some time to adapt Oxford to Africa."

King's grin cut two hard lines from his nose, past his mouth, to mark out a chin designed by a cubist sculptor.

"Sure is some handicap. Gosh, when that lad was writing Greek verse I was skinning mule back in the Dakotas and getting regularly swindled by an old Sioux medicine man on pony deals."

"That's exactly what we need," said the governor. "A man who has been swindled by crafty Indians in pony deals and has learned his experience out of it to adapt it to crafty African spellbinders. A man who knows natives like you know them; almost like I know them."

"Lord, Governor bwana—"

King stalked the room again. Not that he was hesitating, but that he did not know how to temper his refusal.

The governor tried again.

"If you would take government employ as a special temporary agent I could wire to Entebbe and my colleague there would make some allowances for you. But—"

"Yes, but— That's just it," King shot back at him, pointing with a long forefinger. "I'd still have to wrap myself in a gaudy silken cocoon with sacred red tape. Gosh, I'd suffocate."

The governor sighed. He could understand this restless man. He was not one who had been born to the splendor of colonial administration; he had won his way along the line from the long ago days of the Boer War.

"That's the damned American of you," he growled. "If you wouldn't be so bally scornful of necessary authority you'd find some of our youngsters to be jolly decent chaps and this driveling red tape wouldn't bother you. But you're too dashed much like a leopard to change your spots. Well, if you won't, I suppose you won't. I'll have to see if I can find one of our more experienced officers to fill the job. But remember, not a word outside. This thing is an official secret as yet."

King grinned.

"Governor bwana, how many years have you been in Africa, that you talk of secrets?"

The governor smiled whimsically.

"Oh, well, of course there's nothing hidden in Africa for those that have ears to hear. I suppose you'll pick up a lot of underground talk. If you hear anything real I would be glad to know about it."

King chuckled.

"Anything that your blawsted British officials are too high up to hear, yeah? Sure thing. I'm going upcountry after some ivory that I've heard about, and if I happen on any bush telegraph I'll pass the word pronto."

The bush loper left; the secretary returned; and dignity fell over the office once more. The governor sat long and made holes with a pencil in his spotless blotting pad. A worried frown puckered his forehead; then the wise smile spread slowly.

"Ivory?" he mused. "I wonder just where— By Jove, I wonder whether maybe we won't have to detail anybody up there?"

FROM Nairobi a lumpy railroad track straggles northwestward to vast Lake Victoria, which only sixty years ago was Livingstone's Heart of the Dark Continent. Two weeks after his interview with the governor in Nairobi King sat in this train and damned its dreary rattle, bang, crash.

It is about two hundred and fifty miles from Nairobi to Kisumu, the port on the great Kavirondo Gulf of the inland sea. A day and night run if one is lucky, but to weary travelers it seems like a week. Mile after crawling mile of burned brown veld and sparse, flat topped acacia and countless dry dongas—the bridges over which make African railroad building so expensive; and every now and then antelope or zebra in the distance; and dust. Over everything dust. Fine white dust; over the lumpy coach cushions, in the food, sticky around one's collar, smarting in one's eyes.

Quite one of the most unpleasant railroad journeys in the world. Yet since it can cover in two days a distance that a safari could hardly accomplish in twenty, one travels perforce by the train and curses it as one doctors one's eyes against infection from the pestilence of flies.

From this train King alighted at Kisumu and cursed it with mechanical finality. A big, strongly built native grinned all over his face at him. He was dressed in an old khaki shooting coat and the scantiest possible loin cloth. Below each sinewy knee and above the right elbow was a garter plaited of monkey hair leaving a flash of white tuft. He carried a long, beautifully polished stick, which was really a spear with the head removed, since the regulations of well policed Kisumu town did not permit natives to go armed.

But King knew very well that the two-foot long, razor sharp blade of that spear was somewhere not far from the shaft, for a Masai and his weapon do not part company. King was too judicious to inquire.

"N'kos bwana," the man greeted. "Maleff? Train this time good?"

"Ha, Barounggo. Never good. Dak bungalow. And after bath time come and tell me what the talk is in Kisumu."

King gave the man a baggage check and was away while the rest of the tired passengers still fussed with bundles and gun cases and extra hats and all the cumbrous mess that collects in an African railroad coach.

One of the first men King met in the screened veranda of the bungalow was Raynes, Africander and trader. Raynes bellowed a joyous greeting.

"Hello, Kingi bwana! Hel-lo—boy, one long chair and a whisky peg— Heard you had a job with the government. Howzat?"

King grinned wearily.

"Yeah, most of Nairobi heard that one. What's talk on the lake?"

"Nothing at all. Locusts at Jinja; navigation company boat aground on Lolui Island; some yarn about gold in Western Province somewhere; lions bad at M'bale—eating up a couple villages; and trouble brewing up by Rudolf. Usual stuff—new leader with mysterious powers going to put the white man out of Africa. It's a big government secret. Nothing new at all; country's as dead's a convent and only half as wicked. What you doing upcountry?"

King grinned again. This trouble brewing had been the important and very private matter about which the governor had wished to speak to him. But he knew and Raynes knew that there were no secrets in Africa which didn't leak throughout the country faster very often than the white man's telegraph.

"Me—" he told Raynes his business frankly—"I've got hold of a talk about some buried ivory up Elgon way and I'm going look-see." Then, musingly, "Trouble about these little bush troubles is that they usually bump off a couple of white men before the colored gent gets walloped out of his rampage."

"Well," Raynes said, "that's a chance the white man takes when he comes here; and he comes for his own profit, so he's got nothing to complain about— That tall fellow your boy? He looks 's if he wants to make plenty indaba. My bath time, too. Come to my table for chop when you're clean."

King nodded to his man Barounggo to approach.

"After bath time, Barounggo, I said."

The Masai raised his stick in the sign that was salute as well as deprecation.

"Yes, bwana, talk is for after bath. But there is a gift and—maybe some talk goes with the gift."

He opened a grass basket and showed two beautiful melons, luscious luxuries in that parched season just before the rains.

"Ho, good! What friend sends this gift, Barounggo? And what talk should there be about a gift of two melons?"

"Bwana—" the man hesitated and looked up and down the long veranda and uneasily about the compound planted with laboriously cultivated shrubbery.

King's eyebrows flickered and he, too, shot a glance along the veranda. It was deserted; all guests had gone to their baths in leisurely preparation for their dinners. King stepped down to the veranda stoop and seated himself on the edge. He knew his man. The Masai, besides being the most warlike, are some of the most intelligent of the African peoples. Barounggo had been with King for many years and King knew that he was no wild goose chaser.

"Tell me this talk that belongs to two melons. All the talk."

The Masai glanced about the compound once more, poked with his stick into a couple of nearby clumps of palms and bamboos, and came nearer.

"Bwana, there is talk, first, that trouble is growing up among the jungle men of the North."

So the great official secret was all over the bazaar? Of course it would be. But what had trouble in the Rudolf province to do with melons, King wanted to know.

"Bwana, the trouble is a young tree as yet; but it has a strong rain in the words of a new witch doctor. This amatagati has a strong witchcraft. A new juju has come to the land."

The Masai, like the Zulus, love to orate. If given a chance they will declaim all round and about a story in order, as they say, to wrap it with meat before they come to the bone. King stopped him.

"Melons," he said simply.

Barounggo resigned himself. He had a most gorgeous story to wrap with rich meat; but he knew that King was wise, so he came to the point as directly as his innate sense of drama would permit him.

"The talk is, bwana, that we have taken service with the government to go up and stop that trouble."

"The hell!"

This time King was startled. Though not accurate, this was the fastest bush telegraph that he had known. Barounggo, with the air of one who has distinctly scored a point, pulled a wooden plug from the end of his spear shaft and tapped a pinch of snuff on to his thumb nail.

"Melons," King reminded him.

"Yes, as to the melons," Barounggo agreed. "A Kavirondo savage came to me in the bazaar and said he was the servant of that Banyan trader Khoda Bux who has the garden and who remembered you with a full heart and sent these melons as a salaam."

That seemed innocent enough. King had indeed done some service to the East Indian, and a delicate compliment of a small gift was an Oriental custom. But he knew that more lay behind that innocence.

"But," continued Barounggo, piling in his swift climax, "that Banyan has been dead a month and that savage lost himself in the throng of the bazaar."

"O-ho! And so?" King was interested more than on the surface now.

"And so, when talk is of trouble," said Barounggo sententiously, "the wise man looks for trouble. Therefore—" he cast a fierce glance round the compound once more, came nearer and lowered his voice—"observe that melon, bwana. This one; here. And consider that this is the limbwa melon which the white men say is spoiled by the taste of a knife, so they but score the skin and break it open in their hands."

King looked closely and saw that a clean round hole had been punched in the fruit just over the stalk indentation and that the plug had been neatly replaced. He whistled a thin, tuneless rhythm through his teeth.

"O-ho! It is possible, Barounggo, that you have been very wise. Now what trouble, think you, can come into a melon through a round hole?"

"Many troubles, bwana." Barounggo was whispering. "A good witch doctor, such as that one where the trouble is, who might wish that we should not go into his country, could put a strong devil into it. A fool could put a poison into it."

"Or," King supplemented softly, "if he were a white man, some kind of a contact bomb. It won't be a bomb; still, precaution would suggest cutting this interesting melon with a longish knife." He looked at the imperturbable Masai.

"If we had a knife now, Barounggo—a long blade, say, on the end of a long stick—that would be safe, wouldn't it?"

He looked at his man fixedly. The Masai tried to appear not very interested; but King's gaze bored him through. Finally, with another of his fiercely cautious looks around, Barounggo reached his hand behind his neck and, apparently from out his spinal column, he produced two feet of shining steel. The great blade fitted sweetly on to the end of his stick and he handed the weapon to King.

"If a man of the poh-lis should come, this thing is a toy that I have brought for bwana to purchase."

"Quite so," agreed King seriously. "A toy for a small child. Now lay that melon over there; make a hollow so it won't roll. Stand clear now and we shall see what we shall see."

Carefully, gingerly, for who could tell what might be the meaning of a plugged hole in a melon pretending to be sent by a man who happened to be dead, at full spear's length King sawed at the fruit with the keen blade. The denouement came with sudden swiftness. The fruit split softly open and fell apart disclosing its pale yellow inside which ought to have been speckled with large, dirk purple seeds. Not a seed was there. Instead an incredibly swift watch spring thing, colored bright red with a thin black stripe down either side, wriggled free and coiled in compact but deadly menace.

"God!"

Almost as swift as the brilliant coiled death, King lunged the great blade at it. The steel buried itself in the ground a bare inch from the vibrant thing, and it, like a watch spring again, flashed once in the sun and was gone.

"Whau!" from Barounggo. "A limpo'-olu! The snake whose evil is as great as his belly is small. But, tck-tck, a pity. Bwana lacks practise with the spear. Had I held my—the toy that I brought for bwana to see, its one wicked tooth would even now be cleft from the other."

King was breathing hard through his nose, still looking at the spot where the beautiful death had coiled. Mechanically he tugged at the spear shaft, thinking, muttering to himself:

"Hm. There must be a heap more to that fuss brewing up there than even the governor's outfit thinks. Still, none of my funeral—as soon as they quit connecting me up with it." Then, aloud:

"Barounggo, you have shown wisdom. I am pleased. There will be a blanket with stripes as brilliant as that snake. Make no talk with any man. This trouble is not our shauri. We make safari to the Elgon Mountain. We go fast before all the water holes dry up and we come out fast before the big rain. Six shenzis are enough for the going. For the return the number depends upon luck."

WITH the morning of the third day King was striding out of Kisumu at the head of six porters who carried bundles on their heads, Barounggo, who carried only his ever present stick, and a wizened, monkey-like Hottentot who carried an extra gun and the splendid name of Kaffac'-enq'uamdhlovu, which in his queer, staccato language had something to do with the slaying of elephants.

Old-timers who knew King cocked their eyes and wondered what big venture he was set upon with all that equipment. Others, accustomed to seeing the mountainous impedimenta of rich sportsmen, wondered how far this rangy looking fellow thought he could go into the interior with that insufficiency of food, and how long he hoped to keep up that speed.

As a matter of fact King proposed to keep up that speed until eleven-thirty, when he would camp under an umbrella acacia to let the heat of the sun pass over. There was nothing surprising in the proposal; but there was surprise in its accomplishment—to those six shenzis. Four miles per hour had been the pace set; and the porters had swung along easily enough. Experienced sportsmen's porters they were, all of them.

Presently, they knew, this white man would wander off into the veld and would tramp a few miles in order to shoot some buck or other; and in the meanwhile they would lie on their backs and smoke and wiggle their toes in the good dust; and when the white man got back he would be tired and would not go much farther and they would make early camp and there would be meat for them. It was a good, easy business, this portering for white hunters, and the government saw to it that their pay was twenty-five cents a day with potio.

But this white man did not wander off to shoot anything. At a steady four miles an hour he stalked ever toward the horizon of brown, burned plain. The porters gabbled among themselves. It was just as well to establish their rights at the very beginning. It was not that they were tired or that they couldn't keep up that pace. When upon their own business they would carry heavier loads and would keep it up from dawn till dark.

But white men, they knew, were beyond reason; if a foolish man should once show that he could do a certain stint of labor the white bwana would imagine that he could do it again. So they began to blow long moaning whistles between tongue and teeth and to sigh high pitched sighs, and to straggle out till half a mile separated the last of them from the tireless white man.

King wasted no breath in futile admonition, or even the energy to turn round. When he came to a shady mimosa he sat quietly under it, lighted his pipe and fanned himself with his sun helmet. The porters judged this to be the time to come up with lagging footsteps and with great heaving groans of relief. When the last of them had arrived, King rose. He spoke only to Barounggo—reflectively, almost impersonally.

"Does it not seem to you, Barounggo, that some of these shenzis think we have arrived in this land but yesterday?"

The Masai grinned.

"All shenzis are the offspring of porcupines," he said. With deliberate enjoyment he reached his great hand behind his neck and drew forth the rest of his polished walking staff. Lovingly he fitted the blade into position and fixed it with an iron pin. "In my country," he murmured, "we fatten our dogs upon shenzis before we sell them to the bushmen for their corn planting feast."

Kaffa, the little Hottentot, rolled on his back and cackled like a chimpanzee whose feet are tickled. This was a recurrent joke with him and the humor of it never lost its savor.

"Hee-hee-hee-ee! The father of all the shenzis was Mek the turtle. Not till the half hour before noon does the safari stop, O porter men."

And so it was. At eleven-thirty King found a suitable umbrella tree, and the caravan, right at his heels, was within its shade almost as soon as he was.

"Three hours rest. Let any man sleep who will. But first, in that load are mealies, already parched. Each man gets a half portion of potio."

The surly looks of the porters altered with African light heartedness to grins. This wasn't so bad after all. This white man was not one to be made a fool of; but on the other hand, he knew what other safaris never seemed to understand—that food was good at any time.

PROMPTLY at two-thirty King rose.

"Three hours trek," he announced briefly.

The porters took up their loads. There was no murmuring. Three hours of steady going saw the party on rising land twenty-eight miles from Kisumu town. Good going; nearly twice as far as the cumbersome sporting safaris made in a day's trek.

To the northward, miles and miles away, a pale cone of ghost gray without any tangible base stood up out of the dust haze. Almost transparent it looked at that distance. It might almost have been a freak of cloud; but the cool wind that blew from it even at this distance established it as the snow mass of Mount Elgon; and the water beside which King proposed to camp was snow water on its way to feed the Lake of Victoria.

There was a little more than an hour of sunlight left. Just time enough to make camp in comfort. Four of the shenzis under the direction of Barounggo King told off to cut thorn bush and build the customary boma against lions. An hour allowed just time enough to build an impregnable circle of some fifteen feet across and eight high and to stock it with sufficient firewood to last the night through. Kaffa, without bidding, scratched together a few sticks and commenced cooking; the circle would grow around him. The other two shenzis King astounded by saying—

"Go and fetch in that bushbok; the young one under that small tree."

The men stared at him with the ape expression of their kind. The little herd of red-brown antelope were feeding between four and five hundred yards away. How were they, not hunters but porter people, to carry out this peremptory order? They stood therefore and stared dumbly.

This was another never failing joke for the Hottentot. Over his half started fire he chuckled and clucked till he blew bubbles instead of breath at his feeble members.

"Heh-heh-ho-ho-ho—ahuu-uu! Go, turtle footed ones, go when my bwana says it. Else the elmoran, the Masai, will show you how the sun glints upon his great spear when it strikes. Go. Perchance that buck will wait for you. Indeed it will wait for you if the bwana says it."

So the men went. Theirs not to reason why or what foolish things the white men said; particularly this white man. They set off, looking back at every few paces expecting they did not know what.

"And," King called after them, "bring it back whole; without disemboweling it."

This was another foolishness that was beyond understanding. One always cleaned game where it fell. Why carry useless weight? The men with quick African superstition began to be uneasy about all this mystery—which was just what King wanted.

He smiled thinly to himself as he watched them go. Then leisurely he walked to a little knoll, sat and kicked himself comfortable heel holes for a steady position. Carefully he wiped the day's dust from his rifle and blew sharply through the peep sight. He used the precise Lyman .48 and the little sums that went with its use came to him automatically. One point subtended one inch at one hundred yards, was the basic rule. Two inches at two hundred, and so on. For open veld shooting he kept his gun sighted in for point blank at three hundred; he knew his ammunition trajectory to drop three and a half inches between three and four hundred and four inches between four and five hundred.

Very well, four-fifty; six points would just about do it; and the little breeze that persisted was not of sufficient strength to figure. No old fashioned guesswork about this. All that was required was the ability to hold steady. Good eyesight, unshakable nerves, and taut muscles. King had all the requirements.

Taking it easy and without hurry, he fired. The young buck leaped high in the air and fell, and the rest stood staring stupidly at the distant report. Not till the shenzis began to approach did they up-tail and race off.

The little Hottentot, who noted everything with a monkey-like curiosity, pretended to be engrossed with his fire. Squatting as no white man can, with his knees up behind his ears and between violent blowings of the flame, he ventured the question:

"Bwana, for what purpose must those shenzis bring the entrails? There will be meat enough without."

King smiled grimly.

"For magic," he uttered momentously. "There will be a witch smelling this night."

"Aho! Wo-we!"

The Hottentot tended his fire in silence. His master, he knew, had many mysterious powers.

And since King had not expressly ordered to the contrary, this news communicated itself to the little camp before ever the boma was finished. The men, as they worked, looked at him with uneasiness. The gloom deepened. The boma was completed; all but the entry way, before which lay a thorny sapling ready to be shoved into place.

Meat was broiled on sticks and eaten in gloomy discomfort. King sat wrapped in black silence. The shenzis squatted apart and whispered to one another. The last of the day disappeared and the tropic night swept over the land. The atmosphere was full of apprehension. King sat without motion and let it all soak well in.

SUDDENLY he lifted his head and glared across the fire at the huddled shenzis. Upon his forehead they could discern, marked in white, an oval with a spot in its center.

"Aho, look! It is the eye! The eye that sees within!"

They muttered to one another and huddled closer. This was witchcraft such as their own witch doctors practised.

"Bring those intestines!" King's voice exploded into the uneasy gloom.

Kaffa scuttled forward with the mass. Not without a certain disgust King pored over the offal.

"A young buck," he mumbled. "Without horns, without guile, one that had not yet learned the way of lies. The truth unwraps itself."

With his forefinger he made a vast pretence of tracing out the windings of the intestines. With meticulous care he followed the thin tracery of the fatty tissues that surrounded the paunch, bending forward with eagerness, starting with ahs of surprise and ohs of conviction, breaking off to glare across the fire at the wretched shenzis who watched with the fearful fascination of the African for gruesome mystery. This was divination of the surest sort. Only the best of their witch doctors could work this magic. And that this white man should know it too! Whoora-alu! This was fearsomely horrible.

The slow moving forefinger traced the fatty nodules and thin windings of veins.

"This is the house of the evil one," intoned the magician. "This the road that he follows. Here is the fate that awaits him. I smell him out. I see the evil in his heart. Nothing is hidden. Ha, it is finished. I make the test—the test of truth. His death sits in his shadow and is ready."

With that he sprang up and stalked before the wretched shenzis who rocked themselves on their hams and gave vent to moaning misery. In King's hand appeared six white pellets—aspirin tablets.

"Up!" he shouted. "Stand up and take the test of the magic that does not lie! The guiltless ones will grow strong from it; the one with evil in his heart—his belly will swell with his own poison that he carries and he will surely die. Up and open your mouths and let the guiltless have no fear."

With something like relief the men stood up. They knew all about this kind of ordeal. Their own magicians always smelled out wrongdoers that way. And it was true, the innocent ones never suffered; and if one did, why, there was proof of his guilt. The thing was infallible.

The first man opened his mouth obediently. King muttered mumbo-jumbo and popped an aspirin into it. The man gulped and waited, half uneasy in his conscience for past wrong doings, though innocent enough in the present instance. Feeling no sudden cramp in his vitals, he began slowly to grin his relief.

"Good! The first man is clean of evil and he will be strong. But the evil one knows that his ghost grins behind him. Let the second man show his innocence."

The second shenzi took the test with flying colors. The third. But the fourth man in the row was gray with terror. His eyes rolled white and the sinews of his neck distending dragged down the corners of his mouth in a horrible grimace. Suddenly, while the third man was still awaiting the verdict of his stomach, the fellow gave an inarticulate howl and bolted out into the night through the opening in the boma—which King had not closed with thorns for that very purpose.

"Whau!" from the men.

Even Barounggo and Kaffa were impressed. It was a real magic. This had been a true witch smelling and the evil one had fled rather than take the test which would have swelled his belly and killed him in agony.

"So," said King portentously. "His wickedness turned his heart to water. Let him go. Let the ghosts of the night eat him up."

To himself he ruminated:

"Hm. That was a good hunch and the bluff worked. I figured damn sure that that Rudolf crowd, if they thought I was important enough to stop with that melon trick, would have sense enough to work a man in with my porters. Must be a slick bird running that rumpus up there. Glad it's none of my worry. Wonder just what this goof's plan was? Arsenic, I suppose. Wish I could have searched him. Just as well he ran, though. I'd have had to do something pretty horrid to make my bluff good about swelling him up. Well, if the lions don't get him a tough night in a thorny tree will be right good for him."

And then his ruminations were broken in upon by the remaining two shenzis who came diffidently, yet as with a right, and wanted their share of the magic pills which would make them strong because they were innocent. King, laughing at the eternal childishness of the African and which was ever cropping up in some new phase, gave each one a five-grain tablet of aspirin.

THREE days found the little safari on the northern slope of Mount Elgon.

From there King had to pick up old trails. The information that he had gathered about this cache of ivory was sure and accurate; there remained only the exact locale to trace. The story that had come to him about the ivory was an alluring leftover from the days of the great scramble for Africa. Great Britain, Belgium, France, were all playing the vast game of intrigue for control of Central Africa. Nominally they were great trading companies who were just trying to open up business. But the trading companies were supported by troops of employees who knew how to salute smartly to young clerks who openly carried the titles of lieutenant and captain. Besides the business of stealing marches upon each other, these "business men" were faced with the always treacherous opposition of the Zanzibari Arabs who had got into the country before them.

The most infamous, perhaps, of all these traders, was Tippoo Tib who, nonetheless, under the urge of business policy, was appointed governor of Stanley Falls by no less a personage than Stanley himself, who, though an American citizen, was acting nominally for the Khedive of Egypt, but with funds supplied by the president of the British-India Steam Navigation Company.

The whole situation was a scrambled mess of intrigue and counter-intrigue, with vast interests jockeying for control. It can be imagined what a glorious time was had by such a man as Tippoo Tib. A clever organizer unhampered by any inhibitions at all, he sent his raiding parties north and south and east and west. The trail of slaughter and pillage that they left in their wake has been written into the annals of African history.

Their methods were simple and effective: to rush upon sleeping villages, shoot down all opposition, torture the survivors into confessing the local store of hidden gold and ivory, and then carry them all off, men, women, and children, as porters for the loot, and eventually to serve as slaves. Livingstone reports such a caravan of more than five hundred shackled men, each carrying an ivory tusk, and some two hundred women with wrapped bundles of other loot.

Sometimes one of these raiding parties never came back. Fate or weather or desperate natives overcame them. The Buganda, a tribe of a surprisingly advanced state of civilization, who lived along the shores of Lake Victoria, put up an organized resistance to these raiders. The story that had come to King was of a large party who had ravaged the country for a year and had amassed an incredible amount of loot. And then the Buganda hordes came upon them. The raiders swiftly buried their loot, murdered the workmen in approved fashion, and moved out into the best fighting position they could find—and were there very properly wiped out by the Buganda.

Only about fifty years ago, this had happened. Old men lived who had seen that fight. The locale was known. King had checked up descriptions of it from more than one source. What he hoped to find now was some old man who had survived the slave chain and who could perhaps give him some clue as to where all that ivory had been buried before the battle.

When King required information he always went to one of two basic sources: missionaries or witch doctors. Both, he maintained, were excellent people and had many points in common, the most useful of which was that both had more downright accurate knowledge of their people than the most scientific observer could ever acquire.

He made inquiries, therefore, for the oldest witch doctor in the north Elgon district and put himself out to make friends with him. Nothing clumsy or patronizing about his method; he knew the jealousies and vanities of all people who controlled their less intelligent fellows through superstition.

He had met his hundreds of white men whose religion and conviction it was that the African must be dealt with only from the position of lofty dominance. It was a good rule, and he knew all of the arguments and citations with which it was so uncompromisingly supported. But King knew, too, where to make the isolated exception. So he sent Kaffa to the old rain maker's hut with a present of tobacco.

KAFFA knew his ambassadorial duties as well as any diplomat. First he told the old man how good he was; then how good his own master was—a brother of the craft, no less; and that he sent a gift to express his admiration of the other's powers. Thus properly appreciated, the old magician, instead of secretly opposing the superior white man's every move, sent him back a goat, and the way was open for social amenities. So King paid a call and sat on the three-legged stool of honor before the doorway of the hut festooned with bones and dried snake skins and claptrap, and took snuff with the old faker while the uninitiated common herd of the village squatted in a wide circle out of earshot to let the two wise ones discuss the inner mysteries.

The mysteries consisted of the local gossip and the previous rainfall and the movements of game and the chances of a good mealie crop—all around the block and back again for an hour before King broached the question that was uppermost in his mind. He had drawn a lucky number at his first venture. This old man knew all about that battle of Elgon and all about the ivory, too. But there was disappointment in the very definiteness of that knowledge.

Oh, yes, the ancient said, it was all true. He had not seen the fight himself because he had been serving his novitiate in the village of another witch doctor far away; but the ivory had been buried, all right, and the Buganda, having foolishly speared every last Arab, had not been able to find it and had gone away. But some information had somehow remained alive; for after some seasons had passed—he could not remember how many seasons—a strong war party of the Tappuza, who were a branch of the great Elgume tribe, had come down from the north and had dug it all up and taken it away. He had seen it himself; a vast treasure; many hundreds of tusks—thousands, in fact. The warriors of the Tappuza covered the plain and each man carried a tusk; and there were many loads of gold besides.

Aha, what a looting that had been! And the Tappuza were now the strongest of the Elgume peoples because—this was a secret—they had for some time past been carefully trading ivory for rifles which the Armenian and Greek traders smuggled down from the Sudan. Still, there must be an immense treasure left, because it was difficult to get guns; the Inglesi were so stringent about such things. But all the same, the Tappuza were a strong people. And thus and so on for a garrulous hour.

King came away from that interview and was thoughtful. Not because that buried ivory had been removed; as far as that went, one hole in the ground was as good as another. Not because the Tappuza tribe who now had it were a "strong people",—he had dwelt with many a strong tribe before now. Not because these people had it and recognized its value; that merely made a trade proposition of the deal rather than a treasure hunt.

No; King was thoughtful because he believed in luck or fate or whatever it was. In Africa, every now and then, things happened. Without one's own volition; outside of one's knowledge; against one's direct precaution. They just went ahead and happened and one was drawn willy-nilly into the vortex of that happening.

This was one of those happenings. These Tappuza lived up north of the Elgon Mountains. They lived, as a matter of fact, along the western shore of another of the huge lakes of the Great African Rift. None other than Lake Rudolf. That was where King did not want to go; had refused to go. For it was just these Tappuza people about whom the governor of Nairobi had spoken.

Fate; that's what it was. It was too circumstantial to be coincidence. It was just one of those happenings of Africa beyond the molding of mere man. Man proposes and Africa disposes. King felt that he was being pushed up to the scene of smoldering trouble. And that was what gave him thought. Caution never hurt anybody, was one of his rules; another one was: figure it all out in advance and then jump with both feet. That was why he was so seldom hurt.

To be or not to be? There might be profit; there might be danger; for those people who were smart enough to make two attempts to waylay him—

So that settled that little question right there.

"Try to pull their funny stuff on me, would they?" was King's growl.

Well, then, should he go back south to Kisumu, steamer across to Entebbe, see the chief executive there, and go officially with the lavish pay and expenses that the Nairobi governor had offered? He thought of the old Aesop fable about the dog who invited a wolf to dinner; and the wolf marveled at the other's ease of life—comfortable kennel, good food, protection from the constant fear of being hunted, plenty of leisure—until a whistle sounded and the dog jumped up and said he had to go instantly because his master was calling. So the wolf preferred to remain a free lone wolf. King called Barounggo.

"Barounggo," he told him, "from tomorrow we must catch guides to show us the water holes, for that country to the north is bad country and the road is not known to me."

The Masai remained impassive.

"Good, bwana. It is moreover a happening of fate that in this village is a Turcana bush dweller who would return to his country. For his potio and a present at the end of the journey he will show the good places; so I have engaged him." King flicked an eyebrow at such prescience. The great elmoran continued, "It is already known to me that we go north. For three days I have smelled blood on my spear blade."

To which King grunted:

"Humph! Helluva cheerful prophet you are."

THERE is just one advantage to travel over "bad country" in Africa. The quality of badness is contingent by no means upon the roughness of a country; where roads are non-existent, rocks and ups and downs and dongas, or steep walled dry water courses make little difference to the man on foot. Badness in arid country is qualified by the distance between water holes and by the degree of foulness of these holes. Animals drinking at water holes wade in very often up to their bellies. A pool, therefore, with rocky or hard pan sides, is a good hole; for it is tainted only by the animals. A bad hole with sloping muddy shores is thick with ooze and trampled dirt as well as dung. Such water must be strained through a cloth before it is fit to drink.

It would seem, then, that there could hardly be any recompensing circumstance in bad country. Yet there is a very outstanding compensation to the traveler. Where water is poor and scarce, game is correspondingly so; and where game is scarce, lions know better than to waste their time. There need be no thorn boma built every night; no constant watch against prowling danger.

It was a long trek through bad country to the region occupied by the strong tribe of the Tappuza. In point of distance no more than a good day's run in an automobile; but to a safari traveling on foot, a journey of many parched and thirsty days; so desperately thirsty that one drank gratefully the water of the water holes. But that burned out plain began to give place to rolling higher ground, the beginning of the escarpment of Lake Rudolf; trees other than thorn bush began to appear; seepage of water showed among sheltered rocks; green herbage grew. The country began to be fit for human habitation. Another stiff march and one would come to rain forest.

At the edge of the forest, on the highest available ground overlooking the great lake fifty miles away, to take advantage of whatever breezes might blow; yet no closer, for that again meant descending ground and more heat, was the little outpost station of Lo Bur.

At Lo Bur, for his sins—which he did not know—was domiciled Mr. Sydney Fawcett, assistant commissioner of the colonial administration, and Lo Bur was his headquarters station from which his duty was to rule and keep in order a district as large as Massachusetts, studded with scattered villages of the unrestful Tappuza.

To assist him in this hopeful little chore he had a slim, sallow Eurasian, three babu clerks and a black sergeant and six men of the King's African Rifles. Total pay roll seven hundred and thirty dollars; total expenses, traveling allowances and so on—all regularly disputed by the comptroller of accounts at Entebbe—three hundred dollars. All of which accumulated money was sent up every three months under escort and lay in the office safe until disbursed, a temptation to the whole surrounding district.

The official residence was a large, low roofed bungalow with latticed veranda and a corrugated iron roof, perched high on ten-foot posts. At a discreet distance was a row of adobe cubicles, servants quarters. On the opposite side at a yet more discreet distance, a similar row and a stout, square, iron grilled block of masonry—the barracks and guardhouse. There were a well, a vegetable garden and some scrawny banana trees. The whole was surrounded by a strong barbed wire fence. For a hundred yards in all directions every tree had been felled and all brush cleared. An austere, cheerless place that dazzled in the merciless sun. Good for defense but ghastly for residence.

AT LO BUR, also for his sins—which he humbly admitted—lived one Father Aloysius van Dahl. He was a member of the Jesuit Belgian Mission and here he had built a mission house from which his hope was to make as many as perhaps fifteen converts in the course of a year, and to win them to his mission settlement by teaching them to grow better yams and mealies and bananas than they knew how to grow before.

To assist him in this almost hopeless task he had Lay Brother Leffaerts and—a new acquisition—D'mitrius Stephanopoulos, zealous convert from the Greek church in Alexandria, who had shortened his name to the form more in keeping with his present affiliations, Stephen. Total payroll of this establishment, nil. Total expenses, about thirty dollars a month. All of which accumulated wealth was stored in a wooden box under the good father's bed; and which, incidentally, was turned out of a small profit made on carved wooden beads and plaited baskets made by the converts and exported for sale in Belgium.

The mission station was a long, low barrack built of split bamboo daubed with a mixture of clay and lime, and white-washed. It had a thatched roof and stamped clay floors covered with bamboo matting. It nestled in the shade of great flat leaved euphorbia trees, and was protected from the hostile world by tall fences of string beans and a miraculous grove of papaya and guava trees. A blazing grenadilla vine straggled over most of it, usurping its windows and toning down the glare of its whitewash with a delicate pattern of blue shadows. It was an impossibility for defense, but a place of rest for overheated man as well as for countless flashing birds and scorpions and flat toed gecko lizards and brown wood ticks.

It is etiquette in African colonialdom for a traveler to call upon the local government authority; a pleasing convention which disguises the harsh necessity of reporting arrival. For where natives are many and turbulent, and white men are desperately few, with, among the few, the inevitable percentage of those who would sell their own treacherous souls for gain, it is a wise administrative precaution to know the who and the why and the where of each newcomer.

In some of the fussier European colonies in Africa the process is brutally direct. One presents oneself at the local police station, is severely inquisitioned, and is registered—and sometimes even fingerprinted—in a huge tome in which all future movements are marked up. In British Africa one pays a polite call and discloses one's business in the process of conversation.

King, therefore, presented a rather crumpled card to the barefoot sentry at the barbed wire gate and followed him in to the shade of the veranda. Dilapidated brothers of that card were known in many parts of Africa. Some men—like the governor in Nairobi, who knew men—were glad to see them. Some others who had heard stories about this strenuous man from the moving-picturesquely wild and woolly West of that uncouth and inexplicable country, America, viewed them with misgiving.

Assistant Commissioner Sydney Fawcett received the card with a feeling of dismay that was akin to panic, which turned to smoldering irritation.

"Good heavens!" He sank back in his chair and frowned while he fidgeted with a carefully clipped blond mustache. "That man here! As if we haven't trouble enough already. There's always trouble where that fellow is. What the deuce brings him up here, I'd like to know?"

The assistant commissioner's statement, on the face of it, was true; though fault could be found with the nicety of his wording. It was not exactly that trouble was where King was, so much as that that restless man was so often to be found where trouble was. Mr. Fawcett pushed his chair back and called sulkily to a boy to bring two whisky pegs out to the veranda and went to meet his caller.

King had been received by district officials before; he had a quite accurate comprehension of what many of them thought of him; he knew that they thought it because he came and went his own way, that he did whatever he did without explaining means and motives, and that he went away again without making clear exactly what he had done. Or, to paraphrase his words to the governor, because he would not write a hundred page report about his doings. Such procedure was disturbing to the peace of mind of district officials whose business it was to read hundred page reports upon what was going on in their districts.

Yet King just could not bring himself to be the tame dog of the Aesop fable. So there remained the inevitable clash between the regulation bound official and the free citizen who had a strong conviction of his inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Mr. Fawcett Received his caller with formal courtesy and made the formal

Anglo-Saxon gesture of good will by offering alcoholic stimulant. To

which:

"No peg, thanks very much," said King. "Not so early in the day. I'm a confirmed sundowner."

And right there, in the perfectly courteous offer and refusal of a drink, was a source of irritation to a mind already predisposed to antagonism. A little thing in itself; yet a universal cause of hostility throughout the tropics. To any man whose system feels that a stimulant during the sluggish heat of the day is advisable and perhaps necessary, it is a subtle reproof, a never admitted sense of inferiority, to meet a man whose more robust system does not need that stimulant.

Mr. Fawcett was unconscious of resentment; yet this impalpable barrier had been raised. Courtesy could continue to govern all dealings with this foreigner, but there could be no cordiality. Neither could King, for his part, confine himself to the banal preliminaries of polite conversation. He proceeded directly to give the information required by law.

"I report two rifles, Mr. Fawcett; a .457 and .300, and a sixteen shotgun. About three hundred cartridges all told, and two dozen sticks of dynamite."

Mr. Fawcett's jaw dropped to disclose large even teeth and he fussed with his mustache. It was his duty to know, yet he shrank from the barbarous necessity of the direct question. Things just weren't done that way. These matters should always come out in the process of conversation; or, at least, after a decent period of persiflage.

"You, ah—er—are you thinking of prospecting for gold here, Mr. King?"

King felt easier. The stiff preliminaries done with, he felt that he could talk.

"Shucks, no. There's no gold around here—not in the ground, that is; I don't know how much the high muck-a-mucks have got hidden away somewhere—not as yet. I carry the dynamite 'cause I never know where I may be going; just part of my regular kit. I came up here on a yarn about some ivory."

Mr. Fawcett's jaw dropped still farther. He had heard some disquieting rumors about that ivory himself; but if this—quite clearly trader person should come stirring up ancient legends and if he should discover anything, there would immediately be confusion and argument and dissension about property rights and heaven only knew what else. So he set out to explain to King with great patience all about the difficulties and the secrecy of the people, and the almost prohibitive transport problem—and even a hint about the "little temporary unrest."

King nodded appreciatively.

"Uh-huh, you seem to have quite a bit of underground something on your hands. And I picked up a talk about getting guns in. Sounded pretty authentic, too."

Mr. Fawcett shot a quick look at King. From where did this uncompromising fellow get so much information that was private news known only to the official elect? However, he commented only polite surprise.

"Yeah," King supplemented. "Some sixty, seventy guns, I'm told. Martini-Henry carbines mostly, with plenty ammunition. If as many as fifty per cent of them don't blow up there's still enough to make heap big trouble."

Mr. Fawcett was suspicious. This was damnably explicit. More even than he knew. Was this man trying to pump him? Mr. Fawcett was the unfortunate victim of a tradition which the governor in Nairobi could understand. He had been reared in the knowledge that in every outlying colony might be found a certain class of white man who would smuggle guns and liquor to the natives. No white man of his own class would ever descend to such a despicable business. Here was a white man distinctly not of his own class; therefore potentially he might belong to the other class; and this white man seemed to possess much suspicious knowledge.

As official lord paramount of an immense district, with all its lives in his keeping, it was his duty to protect those lives—even at the risk of his own. This King man, therefore, a man of another caste whose reputation anyhow was one of turbulence, must be—until proven—regarded with official suspicion. Mr. Fawcett set about officially to question the not proven alien.

"Why, er—you make a very definite statement there about the number of guns which you say have been smuggled in. What basis, permit me to ask—"

King sensed the thing immediately, of course, and responded accordingly. There it was again, the same old clash between intrenched authority acting according to prescribed rule and its honest convictions, and the individual with an indomitable sense of personal liberty. King's reaction was always that of the boy who dares to tease the policeman. His expression was one of innocent mysteriousness.

"Gossip, Mr. Fawcett, just gossip. Native village chatter. You know natives, of course; and you must know how many guns have come into your district; I'm just retailing scandal."

Mr. Fawcett was not at all sure how genuine was this perfectly true statement. King fired a metaphorical sling shot at a wicked chance.

"And I'll tell you another bit of gossip that'll give you a laugh. Your reenforcements from Karamojo are having trouble with the monthly mail truck and it's pretty sure betting that they'll have to make it on foot; twenty days of foot slog over Africa if they're fast."

That shook the assistant commissioner from his precise reserve. He gagged. Words stuttered in his throat. This man was a devil. How could he know about an urgent appeal for twenty more men—and what did he mean by his certitude of car trouble? If it were all true it would be a condition of desperate seriousness. But he thrust that thought from him. It couldn't be. This unofficial fellow could not know.

As a matter of fact King didn't. He had picked up a story about a runner having been dispatched two weeks ago with a letter going toward the headquarters of the next district. He knew that regular mail communication was by monthly auto trucks, with an escort of two rifles. From this his simple deduction was that news that could not wait for the monthly mail must be very urgent. What urgent need might there be in the existing situation other than a call for help? And the bet about car trouble, then, was no more than a logical sequence. Having his own little experiences about the cleverness of the man, whoever might be organizing this unrest, in trying to keep him out of the game, he felt confident that, if reenforcements had been sent for, the same alert mind would surely plan to delay them; and since their leader would be no more than another native sergeant, he would quite probably succeed.

King left the assistant commissioner wondering darkly just what was his purpose in coming here, and what might be his connection with the smuggled guns about which he seemed to know so much. He chuckled as he went. It was so seldom that the bad boy could put anything over on the policeman. Authority always held all the cards—all the might of government; all the sources of information; all the mutual assistance; and limitless funds. The lone hunter had nothing but his wits and such knowledge as he could dig out by diplomacy. That was what made the game so interesting a contest of skill.

FROM the formal report to intrenched officialdom King went to make a social call of one white man to another at the mission. There was no card of announcement. Father van Dahl was standing under the long fringe of thatch eave over the door. A slight, pale figure with deep brown eyes, visible above a flowing brown beard and mustache, robed in the prescribed habit of the order, which had once been black but which many suns and many washings had faded to a rusty brown, the priest blended into his surroundings. There was no alien note of color or of newness or of harsh superiority; the quiet low house and the quiet little man belonged in that far African setting.

"Mr. King?" The priest held out his hand. "They told me you had not long arrived. I have heard much of—Kingi bwana. You will come in, yes; and the boy will prepare the bath. Very shortly we eat our little tiffin. You will partake with us, no?"

King took the proffered hand that he could have broken easily in his own brown fist and marveled, as he always did, at the spirit that could keep so frail a man in so thankless a place. The cool dimness of the house called to him.

"Yes to all of them, Padre, and heaps thanks. Exactly what my system needs. I hope that all that you've heard about me hasn't been as bad as some other people have heard."

The priest smiled wisely.

"We who live in Africa," he said, "after we have lived a long time, we understand what to hear and how to hear, is it not?"

He pulled, almost as a bird, at King's sleeve; and the dimness of the house swallowed them.

A native boy who had been squatting under a listless banana tree—the kind of boy who is always to be seen squatting about in mission compounds doing nothing—got up, picked up his shield and light throwing spears, scratched his knee with the toes of his other foot, and trotted off along the well trodden trail that led to the native town.

It was a simple little lunch, simply served by Lay Brother Leffaerts, a tall silent man, and convert Stephen, a rotund little person, sallow skinned, with a pair of keen black eyes, and full of laughter about everything. The meal over and the sonorous Latin blessing pronounced, Father van Dahl rose with the self-conscious smile of a child about to perform a trick, fetched a black box and pushed it toward King. In his eyes was pride of achievement. The box contained no less exotic a marvel than Belgian stogies; long, shapeless, speckled, with a straw built into the thinner end.

"Of our own manufacture," the priest beamed. "One accomplishes little in Africa, yet so much we have reached. Our maker is without skill of hand but our tobacco is much better than of the monopoly in Belgium. With the good smoke we can talk. Much news we expect you to give us."

"News, Padre? There is nothing new in Nairobi except the government secret of an uprising fermenting amongst these Tappuza. It's up to you to give me all the gossip that hasn't got as far as the official secret service yet. What's the lowdown about this new juju that the natives are hanging their courage on to?"

The priest looked troubled.

"So? It is uprising that they in Nairobi talk? I still hope it will not come so far. If only this Mr. Fawcett—But tell me first, my friend, are you—" the hands lifted in a pleading gesture—"there was a story that you had taken contract with the government to come and put down this rebellion."

The ready grin reduced King's eyes to slits.

"Hm, that's a nice flattering one. And the story shows a healthy growth, even for Africa. That would be some contract, wouldn't it? Well, it isn't so, Padre. There was a thin basis for the yarn, but that's all. I came up here on the trail of some old Tippoo Tib loot. Things being as they are, I don't know whether I can negotiate a deal. I'm not going to run guns for them, and I don't know whether they'll trade on any other basis till that madness has been walloped out of them."

The priest nodded.

"Yes, yes, the ivory, is it not? Somewhere there is some. I do not know, but our Brother Stephen will be able to tell you. He was, before he came to us, a merchant of the Nile."

Brother Stephen was all eager to oblige, but King checked him.

"Ivory can wait. The little question of transport will keep that weight comfortably right where it is. What about this juju magic? That's more important."

The priest was immediately grave. His eyes were those of a pleading spaniel.

"Yes, yes, that is the most important. They are children, these people; they run to follow a show. This idol, it makes some tricks. The man is clever, and my people leave me. Look, more than a hundred of them I had gathered so slowly with so much care. How many are left? Perhaps twenty, perhaps ten. They have left their good houses, their little plantations that we made with the scientific method; and every day two more, three more, leave off their white clothes and take their spears and go to howl in the night before that devil made of wood. It is the story of Africa. Let Brother Stephen tell it. I will leave you. I still have some small duties left."

Brother Stephen was well informed about the idol. An alert mind with no hallucinations, he dissected the situation with clarity and in fluent English.

THE JUJU was an unusually large one carved out of some black wood, apparently ebony; it was probably not new but quite antique, and had been produced from some witch house by its present high priest who was a cunning old high-binder. It stood upon a roofed platform some thirty feet up in a solitary "ghost tree"; it was hung about with the usual collection of bones and offerings; and it did tricks.

What kind of tricks, King wanted to know.

Well, it's most spectacular trick was that it's arms and jaws moved and it ate offerings—some simple system of strings or levers, no doubt, manipulated probably from the tree against the trunk of which it stood. And at certain times, proclaimed in advance with all its attendant hokum, it talked and gave messages to the people. Stage effects, no more, put across by a smart knave; but quite spectacular enough to capture the infant imaginations of the Tappuza savages and to bend them to whatever purpose the high-binder had in view.

King sat with narrowed eyes. A deep straight line ran from his nose up into his forehead.

"There's just two questions come out of that," was all his comment. "The man or men, whoever they are, are playing up to starting a fuss. Why? And the organized intelligence back of it all is more than the common witch doctor has. Who? If Mr. Fawcett knows enough to find those two answers he'll know how to put the skids under the trouble."

Brother Stephen thrust out his hands, palms uppermost, and his round dark face twisted into a grimace that was not complimentary.

"Ah, yes, if he knew but enough. But Mr. Fawcett is of the 'heaven born.' By reason of the very difficult examinations which he passed in London in order to gain his appointment into the government service in Africa, he knows too much about everything native. He thinks that the way to stop this trouble is to confiscate the ivory so that it can not be traded for guns; and he is hoping to find it."

"That," said King with certitude, "would cause an immediate riot."

"Yes. Immediate, at once. But he will never find it. I could—" he checked himself—"If he were not so high and mighty toward a Greek trader I could perhaps help him. He had even planned to confiscate the juju."

"And that," said King, "would have meant that you would all have been wiped out. These people have too many guns against his little force."

"Yes, but I—but Father van Dahl agreed with my opinion and persuaded him to do nothing so hastily before he had many more soldiers. So, you see, we stand upon a gunpowder mine. My advice to anybody would be to go away before the mine blows up."

King tapped the ash off his cigar with meticulous neatness. His tone was impersonal.

"Yeah, that would be the wise thing for a man to do. But I came up to look into this ivory yarn."

Brother Stephen's hands were eloquent.

"My friend, let me give you my opinion on that matter as a trader of experience. Consider. This ivory is no longer a buried treasure; it must be bought from these people—under government supervision, remember, and the government tax must be paid. If there is not so much of it as you hope—let us say maybe a hundred tusks—the small profit is not worth the distance involved. If there is enough of it to make it really pay, you would need a whole tribe to transport it. Slow travel with the weight; one month's journey to the railway at Kisumu.

"This is not the good old days when you could dash a chief a few gaudy gimcracks and have him order his men out. You would have to pay the rate prescribed by a grandmother government; seven hundred men at one shilling a day apiece with potio and half pay coming back; and you can figure that out—if the government would ever permit so many men to leave their fields at once.

"The gold in quills—that is to say, if there is any—would be taken in by the government as specie and the face value would be disbursed by the benevolent administration for the benefit of the tribe. No, my friend, I assure you, as a business man, this is not a trade proposition."

King remained in silent cogitation, absorbed in intent examination of the end of his second stogie and in the great rings he blew to enormous distances in that still, warm air. At last he said:

"I think you're dead right in everything you say. And I think I'll go and see if this Fawcett gent is possibly as good an egg beneath his cast iron shell of caste as the old governor at Nairobi."

Brother Stephen's shoulders showed his disapproval.

"I would not advise you to do that, my friend. I assure you he will listen to nothing; he will take no advice—" rising passion darkened the sallow face—"he will but treat you with condescension; he will insult you to your face with his politeness; he will—What do you want to go to him for? You are not interested in this thing, you say; not officially. As a trade it is not possible, I tell you. Then leave the official to take care of his own troubles. Go away before trouble comes to you. It is not your affair."

He ceased abruptly and blinked his round eyes, swallowing to control his emotions. King blew some more smoke rings in silence, then:

"You're right again in everything you say. Dead right. All the same, I think I ought to have a pleasant chat with him. And there's the hundred men to be remembered; it would be a pity to have them led astray by a trick juju, the good hundred who have learned to wear white clothes and to grow bigger and better yams."

That apparently forgotten consideration was beginning to dawn in Brother Stephen's fate as King left him.

SO THERE was the whole truth about affairs. Witch doctors and missionaries. Those were the people who always understood the rest of the people and who had the information. King came from the missionary interview even more thoughtful than he had come away from the ancient witch doctor at the Elgon Mountain. He smiled thinly to himself as he walked.

"So that's the answer to the first of the two questions. Clever lad, that; knows quite accurately about everything—" the thin smile stretched to a grin. "Friend Fawcett must have upstaged our Stephanopoulos pretty stiffly at that. Guess I'll take mine tonight after he's had his dinner; he'll be all dolled up and at his best then. I wonder why the Greek doesn't want me to go up?"

At the mission outskirts one of King's shenzis met him. He had been sent, he said, by Barounggo, to lead the way through a jungly path to the camp. They had moved from the hasty halt of arrival and had taken possession of a deserted boma with a couple of huts in it which they had repaired. It was a strong place.

"Good," was all that King said; and he wondered what his two boys had heard that had induced them to move into a strong place, for there were, so close to human habitation, no animal menaces other than the ubiquitous hyenas.

Arrived at the camp, he asked no questions. That would come in its own good time; it was better for the present to betray no anxiety. He washed up, rested, shaved, ate leisurely; which brought him to the time for his after-dinner visit to the assistant commissioner. He signed to Barounggo to accompany him. The Masai was ready; all that he needed was to pluck his great spear from the ground where it stood upright at the entrance to the boma and to stalk behind his master. A thin moon cut black and white silhouettes out of the jungle path. They walked awhile in silence. Then King asked—

"What talk has been this day that you moved the camp into a strong place?"

"A small talk, bwana; yet such as I have heard before a letting of blood. Talk was that the Black One of the ghost tree will talk this night."

"Hmh. That is a talk that must be heard by you or by Kaffa, and I must know what is said by this witch doctor."

"Nay bwana—" the Masai was positive—"the witch doctor does only the bonga, he calls the names and the titles in advance; it is the Black One himself who speaks."

"Hmh!" grunted King again and walked on in silence. Then, softly, "How many men, think you, are following behind us?"

The Masai showed no surprise.

"It has been in my mind that three men come running softly."

"Good," said King. "Now therefore at that bend in the trail where the moon strikes do you step swiftly to the left and I to the right, and we shall see what manner of men come behind us in the night."

Some thirty paces farther the trail took a sharp curve. No sooner round it than both men ducked into the bush and crouched. In a few seconds padding footsteps sounded and the followers trotted into view.

King's eyes narrowed in the dark and he took a quick breath. He had seen this kind of night runner before. Three strongly built savages, naked except for their gee-strings; each carried a short, heavy stabbing spear; their heads thrust forward, the moonlight glinted white upon their eyeballs, distended with excitement, and upon strong white teeth showing between curled lips that panted wide, though not with the exertion of their stealthy running. Killers they were, and the lust of hot blood gleamed from each dark face.

"Well, of all the damned nerve!" King muttered, and hurled himself out of his hiding place in a flying tackle at the foremost runner.

The man crashed down with a startled yelp and King instantly rolled with him into the black shadow of the underbrush.

At the same moment a coughing "whaugh," the war shout of the Masai, told him that Barounggo had not hesitated. His own man was a burly fellow who, after his first surprise, fought in ferocious silence. In the darkness King, clinging to his spear hand, found some difficulty in locating the fellow's head, holding it down with his free hand and smashing his knee hard under the ear. The squirming figure went limp.

King leaped from that place, ten feet in one great bound, to another patch of shadow beside the path and crouched for whatever might come. Running feet receded farther up the trail. A tall dark figure stood with his back to a tree, head forward, great spear poised. King was at a disadvantage. He tore his automatic from his belt holster, though under the very shadow of the established law, as it were, he hesitated to get himself involved in any premature blood spilling.

But the dark figure in the half-shadow of the tree did not move. The head hung in the same forward strained position. The threatening spear pointed not at King but curiously horizontal. In the same second King knew. He whistled thinly and pushed his pistol slowly back into its holster. He stepped close softly. The spear was not one of the short stabbing spears of the killers, but the great weapon of the Masai. Four inches of the blade's butt, a hand's-breath wide, showed darkly red before the man's chest. The remaining twenty inches of steel were through him and fast in the tree trunk behind.

KING was levering the blade loose when running steps sounded again. Single footsteps. It was the Masai, eager, face gleaming with excitement. He stood and regarded his handiwork critically.

"Hau, that was a good stroke." He began to stamp his feet in a savage rhythm and to declaim his exploit in an impromptu sort of chant.

"A good stroke; a fair stroke. In the dark I smote, yet my blade has eyes to see in the night. A nose it has, a keen nose to smell out the heart of my enemy. Who is the dead dog who lifted spear to me? To me, an elmoran of the Masai. His point scratched my breast and I smote. Ha! Where is he? Hau! He is gone—"

"Shut up!" King told him tensely. "Cease this bragging. This is a bad business. What of the third man?"

The slayer stopped, balanced on one foot, the other ready to beat the next rhythm. King noted a thin gash in the breast of his khaki coat, the edges of which were tinged with blood. But his wound would be the last thing that the Masai would pay attention to. His reply was in an injured tone.

"That one's ghost sits beside him and moans. My hands were empty and he came at me with his spear. With his little spear like a fool he came, as one who hunts an ape. I have seen many spears. I moved my body—so; and with his own toy I let the cold night enter his breast." Triumph began to possess him again. "Aho, it was a good fight. Swift but merry. Scarce the space of three good breaths that a man may take and three men lie dead. Surely a good little fight."

"Please, great slaughterer," King checked him. "It was not good. And three are not dead. This one in the shadow we must take and bind. It is a bad business. We sit under the very mantle of the Inglesi serkale, and much trouble will be made over spilled blood. Sure justice will come in the length of days; but there will be talk and bother and interference at this time when I want no interference with my doings."

The Masai put his balanced foot to the ground and scratched his buttock. The excitement of battle was giving place to penitence.

"That is indeed so," he agreed. "I have seen the serkale do its work. Men will come together with many papers; they will sit as do the rock baboons and will make a great indaba; they will weigh useless talk as the monkeys weigh rotten sticks and they will throw words to all the four winds for many days. In the end one will pay blood money and go free. Yes, I have known this thing."

King stood frowning at the body of the killer who was still pinned to the tree. A trickle of blood crawled the length of the spear shaft and fell with a plop on to a dry leaf. This was a nasty dilemma. The three men had quite obviously followed them with murderous intent in the third attempt to keep him out of the fermenting trouble. Everything could no doubt be proven and cleared up; but the one certainty of the whole affair was restrictive delay.

The Masai spoke from the shadow where he was tying the unconscious man's hands with a quickly twisted rope of grass:

"Bwana, there is a word in my mind. I have many times listened to the talk of the m'zungu mon-pères, the white priests who say that their great white spirit who rules all things has put all things into the world for a good purpose. This is a hard talk to understand, but a little is clear to me. For this good purpose has he put these many hyenas into the land. Let me throw these twain dead dogs into the first donga and in one hour it shall not be known how they died. And if bwana will permit likewise that this third dog who would have murdered us from behind—"

King grunted a short laugh and came to a decision.

"You'd make a swell convert for the good padre; you have the faculty of acceptance of fundamentals. Listen now, Barounggo. Thus it shall be. Give these two to the hyenas; this third one take back to the boma; bind and watch him well. He must be questioned and we may learn something. I go to talk with the bwana Inglesi."

THE ASSISTANT commissioner sat in his veranda in solitary after-dinner state. King could see the pale glow of his shirt front, a white splash in the deep shadow, long before he reached the steps.

Like any other man, he had grown up with certain traditions, himself. One of these was that to wear anything white was a foolish invitation when trouble was abroad. The formal greeting concluded, the formal drink accepted, King ventured a well meant warning.

"Mr. Fawcett, you ought to be able to step out there and look at yourself once. You've no idea what a target a boiled shirt makes for any sportively inclined coon who's got one of those Martini-Henry's."

Mr. Fawcett's reply was stereotyped, as one expounding a creed.

"Oh, I suppose it is visible at quite a distance. But then, Mr. King, one can not drop all the conventions of decent civilization just because one happens to be posted in a savage country."

King, dressed in breeches and shooting coat, and with frayed cuffs at that, grinned to himself in the darkness. He had met this same thing all over Africa. It was the proper thing to do and it was therefore done. Tradition again; and unswerving faith to it.

But he had come to talk, not to quarrel with another man's religion. He approached his subject placatingly.

"Will you let me ask you a few questions, Mr. Fawcett—and let us look at question and answer quite impersonally?"

Mr. Fawcett inclined his head.

"Well, then," began King, "have you formed any idea of what is the real bedrock reason for this unrest here?"

Mr. Fawcett weighed his answer.

"I don't mind answering that question, Mr. King. And I say, no, I do not know. I believe it to be the work of a crazy witch doctor inflated with a sense of his sudden power over his superstitious people. And in turn, I would ask you why you are interested in this unrest?"

King weighed his answer in turn.

"I'm interested only, as I told you, Mr. Fawcett—that is to say, I was interested—only in so far as it affected this ivory story. But—" the eyes narrowed to the same hard thinness as the mouth—"some nervy gent connected with this fuss is so interested in me that he's begun to warp my judgment. But let's continue to be impersonal for awhile yet. Let's suppose, for a moment, that everything was quiet here and a man should locate this hoard and deal for it legitimately, would you sanction his hiring porters here?"

"That would depend," said Mr. Fawcett judiciously, "upon how much ivory he wanted to take away."

"Well, suppose that man should tell you that there were seven hundred tusks; what would you say?"