RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

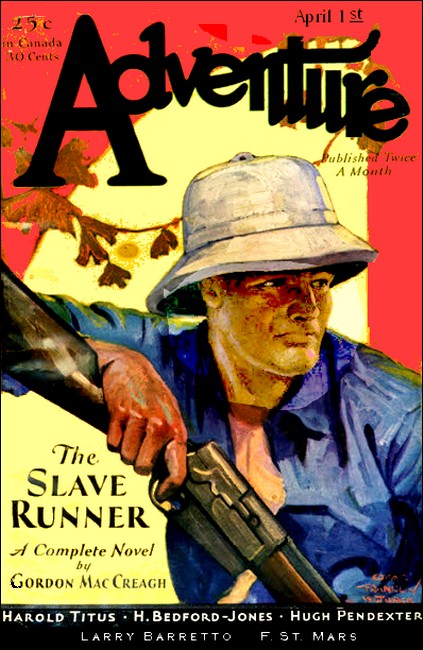

Adventure, April 1, 1930, with "The Slave Runner"

"THE news is that Kingi Bwana is dead."

The speaker burst into the Williams Hotel in Nairobi and exploded his news like a bomb, and with all the wide spreading and diversified effects of which a bomb is capable.

The Williams is the hangout in Nairobi during the off season of all the safari conductors of East Africa. Sun-browned, heat withered old-timers, whose reminiscences are of the good old days before licenses, when ivory was lucrative spoil of any man who had cold steel nerve and a vast double barreled rifle that fired about ten grains of black powder and a bullet weighing a quarter of a pound.

Younger men in their forties, equally sun scorched and wiry, who helped the old-timers swear at the effete modernism that imposed a license upon each individual bok and beeste and allowed but a paltry couple or so of each per season. A few youngsters as brown, though not as yet so hard drawn, who envied the older ones their experience and dreamed still the dream that all of them had known of finding, perhaps, by some stroke of improbable fortune, some hidden stretch of new ground where the best heads had not been picked over by past safaris.

Men of many ages and many nationalities; but every one of them marked with the indelible stamp that distinguishes all their kind—the narrow eyes with the deep corner puckers that reflect long days of gazing into shimmery distances, dancing yellow veld and blue haze under the sun.

And all in the same business. A business which they called—strictly among themselves—lamb herding. Which meant that, since East Africa had become a fashionable picnic ground for wealthy sportsmen from Europe and America, these hard bitten Africanders put their experience to the practical purpose of conducting these tenderfeet out on safari, and showing them how to shoot.

Among the gathering in the hotel when the bomb fell were a few officials of the colonial government, whose duties took them into the outlying borders, and who therefore found something in common with these men of the wide veld.

The bomb's diversified effect was not apparent till after the first shock.

"Kingi Bwana dead? How? Where? Who's got the news?"

"Couple of his boys are in. A lion got him, they say, up along the Abyssinian border."

"A lion at last! Good gosh! Well, he always took the most awful chances."

Klein, a small wiry man, who was known throughout East Africa to have killed some hundred and fifty lions or so—he didn't know exactly how many, he had lost count—shook his head and announced in his querulous voice:

"I'll have to see those boys an' get an awful lot more evidence before I can swallow all o' that. Kingi Bwana got by a lion? That don't hold water."

"And he didn't take chances, either," another grizzled hunter put in. "You're wrong there, Jacobs. He gave the impression he took chances 'cause he'd smoke a pipe an' hold his fire till his game was right on top of him. But that was 'cause he knew jest 'bout exactly what his beast was goin' to do. Why, Kingi Bwana knows how a lion thinks."

"And he can shoot, boys, and don't let anybody forget it. Could shoot, perhaps I should say, if this yarn is anyway true. Let's hope it's all just another of those nigger rumors. What are these two boys? Kavirondo? They'll surely have it balled up."

The other side of the bomb's effect came from Sanford, a deputy district commissioner, who seemed to harbor a grievance.

"Well, all I can say is—" he laid down the law thickly—"if this fellow King is dead, it's a very good thing for the border district, and for a lot of other poor devils besides."

Immediate indignation was loudly in evidence; but the loudest voice was Klein's, and Sanford's official standing was no check to the tough little hunter's anger.

"You shut right up, Mr. District Commissioner Sanford. I know what you're driving at, an' I say you've got no proof."

Sanford flushed. He was a big man and powerful, though running a little bit to flesh. His heavy eyebrows meeting above a strong nose denoted temper and wilfulness; and the dignity of his position sat heavily upon him. He might have resented Klein's peremptoriness more definitely; but he had been looking upon more whisky pegs than he could very well carry. So he contented himself with words.

"I know I have no proof. He's always been too bally sly. If I had had evidence on the half of my convictions he'd have been doing his time on the Breakwater two years ago. But nothing will ever persuade me that he's anything but a damned Yankee slave runner; and if he weren't dead, as I sincerely trust for the sake of his wretched cargoes, he is, I'd catch him red handed at it sooner or later."

A laugh came from the corner.

"You're a damned liar, Sanford," drawled the voice behind the laugh. "And if you weren't, you'd never catch Kingi Bwana at anything."

"Who says I'm a liar?"

The commissioner pushed himself not oversteadily to his feet, while the veins in his temples swelled purple against the flushed red of his face—with the effort, as much as with his Jove-like anger—and he made as though to plunge at the insulting corner.

"We all do!" came an immediate chorus of a dozen voices.

The black eyebrows scowled their rage about the room. But hesitantly. Where, in the face of such universal opposition, could one begin?

"Well, I can't thrash twenty of you," the outnumbered man muttered, and slowly sank to his seat again.

The drawling voice from the corner took up the tale again.

"There's an example of the official mind. Somebody runs slaves along the Abyssinian border. He's too smart to be caught. King is the only white man operating around there. King's a smart man; moreover, he goes his own way and gets things done without either official help or permission, which is blasphemy and lèse-majesté. Therefore King's the culprit."

There was a general laugh. The lazy-voice had neatly hit off just about what most of these free men of the veld thought about most of those whose duty it was to impose official restrictions upon them. Sanford, fuzzy headed as he was, saw that sentiment was overwhelmingly against him. He heaved himself up and strode with heavy, unsteady dignity from the room, leaving only the Parthian shot:

"Some of you smart gentlemen will perhaps remember our little conversation when next you come before me for overshooting your licenses. Come along, Peterson; let's get out of this den of know-it-alls."

A youngster whose fresh English complexion denoted his newness to the country got up and followed him, and a voice followed them both—

"You'll have to have evidence of half your convictions, old man; don't forget that."

Various murmurs of approbation, of belated indignation, and calls for pegs swelled in the room. Above them Klein's nervous voice—

"And now I've got to get hold o' those two Kavirondo boys and see how much truth I can beat out of them about poor old Kingi Bwana.

DEPUTY COMMISSIONER SANFORD and young Peterson were en route across

the trackless veld. As a matter of fact, Sanford had come down to

Nairobi to meet Peterson and to take him up and install him in his job, which

was the rather ghastly one of British consul at Moyale, on the Abyssinian

border, where the caravan trail came through to Kenya Colony. Peterson's

predecessor had died of dysentery with the appalling suddenness of Africa,

and Sanford, between gasps for breath and grunts as the Ford car bounded from

hollow to grass clump where the road was no more than a general direction,

was laying down the law of conduct.

"There are just two rules, young man; and they are absolute, without exception. Never step outside of your door without your solar topee on your head. That one is easy. The other one sounds easy, but it isn't. Always boil everything you drink. It isn't easy because you've got to see to it yourself. Leave it to your house boys just once, and they'll dip you up the nearest filth to save themselves trouble and will all swear themselves blind dumb that it boiled for half an hour.

"That's what happened to young Smith. He got careless. You watch those two rules and you'll pull through all right. Your job won't trouble you much. It's a loaf up there, really. All you've got to do is to hold up the caravans, which are few nowadays, and collect customs on them. Not more than a day's work in the week; and you'll get some of the best shooting that's left in Africa."

Peterson was immediately interested. Sport, of course, appealed to him much more than work. He fell to asking innumerable questions about hunting and about the beasts he might meet and about their ways. And Sanford supplied him with the usual miscellany of fact and misinformation with which colonial officials are so copiously supplied.

Sanford was doing all of his necessary talking now, in spite of the discomfort of the jolting car, because presently they would come to where deep gullies intersected the plain and the car would have to be abandoned for safari. Safari meant foot slogging over Africa; for the tsetse fly pest killed off all horses, and even mules, in three days. And on safari the bulky assistant commissioner needed all his breath for the deadly business of putting one foot before the other.

There was one important matter to be settled before that trial arrived. More important even than sport. Peterson introduced it.

"What about this slave business?"

Sanford's thick brows came together in immediate anger and weariness. The slave business was the particular cross that he had to bear, and he swore at the very mention of it.

"That's my blasted shauri. You don't have to worry much about that; except, of course, to help me with any information that you may get hold of. Though, at that, it'll trouble you enough. But your job is simple. It is British law that as soon as a slave sets foot on British territory he is a free man. You'll be having slaves skip across the border to escape from bestial treatment; and then a host of Abyssinian officials will come yelping to bluff you into giving them back what they call their property. They're the most insolent people on earth—nigger men boss in their own country. They think they're as good, or better, than a white man, and they'll shout and stamp and scream in front of you with no more respect than if you were a shenzi; and they'll try to bulldoze you into giving up their runaways. Your job is to tell them all to get to hell out of British territory unless they have passports—which they never have—and give up nothing; not even a dog or a stray cow."

Sanford was voicing no more than the universal opinion of every border official in Kenya Colony; and, while there was a good deal of truth in what he said, his statement was not free from official inaccuracy. He went on to furnish further misstatement according to the best of his light.

"My end of it will hardly affect you as far west as Moyale. The game farther east is to raid the runaway slaves and run them out of the country for sale elsewhere."

So startling a statement sounded like the horrors of fifty years ago. Slaves were bad enough; but traffic, organized business, in slaves, was incredible. Where could one buy or sell slaves in this modern day of grace? Peterson required enlightenment. Sanford supplied it with weary disgust; and this time his information was true.

"This is how it happens. Slaves escape across the border all the time. There exists one or two gangs of raiders, Arabs mostly, who round them up; either bluff them, lie to them, pretend they are British officials sent to protect them—the slaves are animal fools, anyhow—or they just recapture them by plain force. Then they jockey them along the border line. If we get after them, they skip into Abyssinia. If some Abyssinian chief thinks he'd like to grab up a good collection of slaves for himself, they slip over to our side. So they jockey them along eastward and finally run them across the corner of Italian Somaliland to the coast from where they ship them in native dhows to southern Arabia. And if anybody tells you you can't sell slaves in Hadramaut today, you can just have a good laugh at him. The Sultan of Es Shehr will snap them up as fast as you can deliver them, and the Sultan of Chishin will outbid him."

Young Peterson gasped at the recital.

"But, good Lord, that's frightful, don't you know! That sort of thing ought to be jolly well stopped."

Sanford grunted with grim disgust.

"That's my shauri to stop it. If the damned Abyssinian officials would cooperate we could do something. But they're useless. We have treaties with their central government about mutual help; but these border gorillas are too far away to care. Each little monkey chief is a law unto himself, and our complaints get nowhere."

"But—but hang it all then, sir, can't the Italians stop them going through their end of Somaliland?"

Sanford barked a harsh laugh.

"Pah! The Italians! Imprimis, they don't care. Secundo, it would cost a lot of money and men to keep up a constant patrol of their desert. And finally, if a patrol did attempt to interfere with a slave runner, it would get a good licking and the cargo would go through anyhow. We know perfectly well where they get through. Just north of Illigh there's a maze of little rivers and creeks called Baia del Negro, where, as its very name implies, they've shipped slaves through for hundreds of years. If we had that territory we'd stop the business in a week. But those damned dagos either don't care, or they're afraid to tackle the slave gangs, who are a pretty hard and cunning and desperate crew, let me assure you; and I know because I've dealt with them for two years."

Sanford was that type of stanch Englishman to whom every foreigner was a person inherently inferior by the automatic reason of his alien birth. Such a person might, if he conformed with religious strictness to the conventions of the Sanfords and their ilk, be accepted upon terms of gracious familiarity. But if he did not so conform, he was to be anathema, utterly without the pale, and was to be mentioned only with a properly qualifying epithet. Sanford's favorite epithet which adequately, to his mind, expressed the noxious foreigner, was "damned."

"That's pretty dashed thick," was all that Peterson could say.

Sanford continued with gusto. It was seldom that he got a chance to air his pet grievance.

"The worst of them and the best organized is a scoundrelly Arab-Italian halfbreed called Matteo bin Ibrahim. He is—he was—in partnership with this damned Yankee, this King fellow, and they were as cunning as they were conscienceless. But I'll trip him up now, by Jove; King was the brains of the combination."

"Was, you say, sir? Is that true about the lion then? And he seemed to have a lot of defenders of his character."

The stanch defense of the hunters in the Williams Hotel had evidently had its effect upon young Peterson. But the older man grunted forth his creed; and it was, without doubt, based upon his personal experience; though just whose was the fault for such experience it would not be quite easy to say. Pompous officialdom clashing with independent spirits might have explained much. However, Deputy Commissioner Sanford's opinion was his opinion; and, as such, he was ineradicably convinced it was right; and he voiced it accordingly.

"Hm! Those fellows will always side with anybody against a government official; and you may as well remember that in your future dealings with them. And the lion story is true, thank heaven. I had those boys brought before me and questioned them. It's a providential deliverance for the whole district; and I feel that now I shall be able to break up this horrible traffic."

All of which, as the drawling voice of the Williams Hotel would have said, was typical vaporings of the official mind; and of all officials, typically Sanfordian.

YOUNG Peterson was out for sport. Intently and eagerly out. For two reasons. One was that a native had come in and reported a pair of roan antelope in the neighborhood, and had sworn that he could lead the consul bwana directly to them.

Roan antelope was a prize extraordinary; one for which many rich sportsmen would make a safari especially to get. One of the curious habits of this splendid beast is that it appears in a district suddenly from nowhere, and then disappears as suddenly without trace into nowhere. So no time was to be lost.

Another reason was that Peterson's servant had announced enigmatically—

"One bwana coming from Abesha side."

"Huh! A white man from Abyssinia?" This was unusual.

Native caravans came through; but white men at this farthest extremity of Abyssinia were as few and far between as roan antelope.

"From where do you know this news, M'boko?"

"One shenzi tells. One bwana m'kubwa comes; he got plenty men, plenty tent, plenty gun; he got even horse. One bwana Amlikani. Two days' time he get here."

Peterson had already given up trying to find out how the natives got their news. He had spent fruitless hours in questioning, just as had hundreds of other white men, who had also given up and accepted the thing as a mystery which they named "bush telegraph," the surpassing mystery of which was its so often astounding accuracy.

An Amlikani—an American—Peterson could believe. Any crazy thing was to be expected from them. One had come through last year. Peterson had heard a great deal about that one. An enormous fellow, traveling for some museum or other; loud mouthed and braggart, who tried to convey the impression that he alone, on account of his size and vast experience in organization and expedition equipment, could make such a trip. The hunters in Nairobi still laughed over his pretensions. The more so since an indigent family of Czecho-Slovakians, including a woman and a child, had made the same trek from Abyssinia to Nairobi with nothing more than they carried on their own backs. Yes, anything was to be expected of Americans. But a horse—and in that tsetse infested country? The old futile question shot from Peterson's lips—

"How do you know?"

The servant retired behind his mask of African obtuseness.

"One shenzi tells. Two days' time he gets here. You wait see."

Peterson had heard too many stories about bush telegraph to disregard this information in its entirety. Another American might well be collecting for another museum. Museums in America were insatiable, he knew, and were positively choked with money for expeditions into Africa. Roan antelope would be an achievement for such a museum to hurrah about. So Peterson silently consigned all bally Americans to perdition—he was young enough to follow in Sanford's school of scorn for foreigners—and he girded himself swiftly to go out and get those roan antelope for himself.

Of course, they were not where the little Kavirondo had said they were. That is one of the peculiarities of roan. A long day was spent in vain tramping over a burning veld, trudging up to the tops of the low rolling hills and blinking at the far heat haze through the field glasses, wondering fretfully whether the game might not be lying down in the long grass just round the shoulder of the next hump of ground.

Impalla were to be picked out here and there in the open plain, of course. Impalla are always to be seen sporting and leaping in the middle of no shelter, relying, apparently, upon their knowledge of their phenomenal speed to save themselves from prowling enemies.

A few stray kongoni, too, in the shade of distant flat topped acacias; and in the far distance, what might be zebra.

BUT Peterson was not after any such common stuff. Those he could go out and

get any day. He wanted roan antelope and nothing but roan; and he knew that

an ill advised shot at something else might startle the very beasts he wanted

out of the nearest clump of tall grass; and then they would run for miles. So

Peterson tramped over the veld for the whole of a scorching day and

got nothing.

But hope springs eternal in the hunter's breast, perhaps more so than in that of any other human. The next day Peterson was out betimes again, and in a sweat of excitement, for the little Kavirondo pointed at shapeless blurs in patches of sand and said that they were the tracks of the coveted roan. His M'boko, unaccustomed to the job of gun bearer, added to his master's fever by pointing in the general direction of north and announcing stolidly—

"Amlikani bwana safari come that side."

Peterson was too busy to ask the useless question of how he knew. The little Kavirondo was giving vent to ape-like duckings and smacking of the lips. He was spreading his squat nostrils to the warm wind and rolling his eyes. All of which denoted a simian excitement at the nearness of game.

Many white men have wondered how some native hunters can detect the nearness of game where nothing is in sight. The little monkey Kavirondos scratch themselves vaguely when questioned and say they can feel it in their skin; and they often add—

"The same way a lion feels it."

Many white hunters with plenty of experience behind them maintain that the whole performance is hokum designed to impress the foolish bwana in the hope of getting a bigger backsheeshout of him; that one will come upon game sooner or later anyhow. Many other white hunters, with longer years of experience, just look away into the distance and say they don't know; it's damn' queer.

At all events Peterson's Kavirondo led him off in a new direction and began to scramble through a country dotted with low mimosa scrub and outflung clumps of rocks, and intersected by narrow, deep little gullies. Good lion country, had Peterson experience enough to know it.

After some two hours of this frightfully tiresome going the Kavirondo suddenly flattened himself into the grass at the crest of a rise and beckoned with nervous fingers behind him. M'boko quickly pulled his master down to his knees and made him understand that caution was necessary.

The Kavirondo was pointing a skinny, copper bangled arm across the empty nowhere. Peterson, of course, could see nothing. But following the pointed direction through his field glasses, he presently discerned, marvelously blended with the heat shimmering yellow grass, a pair of magnificent reddish brown beasts with long curving horns. They were too far away to distinguish, even through the glasses, the black and white face markings which would identify them as roan antelope; but he "felt it in his skin" that the little hunter's excitement was not over any lesser game; and the excitement immediately transferred itself to him. Accordingly he acted with less judgment than even his inexperience excused.

It was a long stalk. Not altogether difficult, on account of the excellent cover afforded by the gullies and mimosa brush; yet formidable enough for a novice. Young Peterson felt that he would have difficulty enough in hiding himself alone, without the added encumbrance of two tagging along behind. He ordered them, therefore, to stay where they were, and he set off with infinite, and as yet unnecessary, caution alone.

Had his boy, M'boko, been a trained gun bearer, he would have remonstrated. A gun bearer knows that he has but one duty on earth; and that is to stick closer than glue to his master's heels. To advance when he advances; to stop when he stops; to lie prone when he lies prone; and to run away when—and only when—his master runs. There are gun bearers, few and rare, who have been known to observe that last rule. Their usual procedure is to be well and safely up a tree when the second gun is required at the urgency of life and death.

A gun bearer, moreover, would have told young Peterson that it was the sign of a very foolish novice to go off alone, with all faculties intent upon stalking game, in a lion country. But M'boko was a house boy. What did he know about such things?

As for the Kavirondo, he immediately curled himself up in the grass like a dog to snatch some moments of instant sleep. What business was it of his to question the will of white bwanaswho went hunting? They were strange, inexplicable people, were bwanas, who would talk meaningless words which they thought to exist in the Swahili language, and who would thereupon fly into exasperated rages and would beat natives for no reason. The white men were the lords of the earth. It was always better to let them do exactly as they pleased. So the Kavirondo curled up in the grass and chattered contentedly at M'boko.

PETERSON crawled off alone. He had traversed with infinite caution an open

stretch and had climbed in and out of the welcome shelter of a gully; he had

made a hundred yards, when he heard an insistent chattering behind him coming

from where he had left the servants. In an immediate frenzy at the brute

idiocy of natives, he turned to curse the fools, although they crouched

yards, hundreds of yards, too far away for the beasts to hear. And at the

same instant a sudden tightening of the breath caught at his chest as the

belated thought came that the men were trying to attract his attention to

some danger. But it was not the kind of danger that he had, for a moment,

half feared. Both men were pointing excitedly beyond him and away to his half

left. He looked, and his heart fell to the very soles of his veld boots.

Coming over the distant ridge was a long line of black figures with bundles on their heads.

Peterson diverted his curse to the crawling line. The thing was true then. This must be the safari of this pestilential American. Why in hell must the thing come just in this direction out of all Africa? And exactly at this moment, too? Why couldn't it come tomorrow, or yesterday, or just half an hour later? And why must it be just this bally American who would be keen, with all the energy of his race, to get roan antelope above all other things?

Thus did Peterson curse the unwelcome interlopers and his own luck, too. Then he began to see that the safari would pass to his left anyhow, in the direction of Moyale; and with a muttered "Thank God for that," he set himself once more to his long stalk.

But it was his fate that day that annoyances should interfere with his sport. He had made another three or four hundred cautious yards, when a distant shouting began to impinge upon his consciousness. In a blaze of impotent fury he turned his head to see a khaki shirted figure, still some four hundred yards away, racing toward him, mounted upon a miraculous horse, waving his arms like a maniac and shouting as though there were no game within a hundred miles. Something or other, clearly, the fellow was trying to bring to his urgent attention.

Peterson cursed him in silent rage for a fool as well as a poor sportsman. Some idiot idea the man must have to deter him from his game till he could come up and get in on the stalk. Well, he'd be eternally damned if he'd allow that. With gritted teeth he set himself to cover just a few more yards of bush to where he could get a clear, though long shot, before the other should arrive on the scene.

Then the maniac began shooting. Peterson through a red haze of fury saw that the lunatic was using a pistol—and at four hundred yards.

"Rotten, blasted Yankee sportsmanship!" raged Peterson.

And murderous thoughts of turning his rifle upon the maniac coursed through his mind as he saw his precious roan antelope throw up their heads, jump high once as a spent bullet patted somewhere near them, and then race off, skimming the grass like brown thistledown. In desperation he essayed a futile shot; missed, of course, and turned in black fury to shake his fist at the careering madman.

The idiot was screaming at him and pointing at something. Somewhere back of Peterson. He was near enough now for snatches of words to arrive on the wind.

"Look out!" they sounded like. And, "In the long grass!"

Once more Peterson's heart skipped a beat. The urgency of the maniac's actions seemed to imply—was it possible that something— The dormant sense of danger that stays with every man in the lone African bush leaped to startled life. Peterson concentrated on the long yellow grass forty yards behind him as much as his thumping pulse would let him. It seemed to him almost that it moved. But it was impossible that anything should be there. He had crawled through that very patch just a few seconds ago.

The thundering of hoofs was in his ears; and above them the urgent voice again;

"Look out! He's going to charge! Hold your ground and take it easy!"

Then Peterson was sure of movement in the grass. Something that swished from side to side. Something like a yellow rope frayed out to a tuft, or tassel, at the end. And then just in front of the swishing thing a face took form in the yellow grass. A yellow face, huge and menacing; yellow eyes fixed with frightful intent upon his own, and with a great fringe of yellow hair that trailed raggedly off and blended with the grass.

THAT was when Peterson should have shot. That was his perfect chance. But he

stood and did nothing. He was not exactly afraid. His mind registered the

perfectly clear fact that he was face to face with a lion for the first time

in his life; which would be quite as clearly the last time if he did not

immediately shoot, and that, with cool accuracy. Yet his limbs refused to

respond to his mental impulses. He did nothing. He just stood.

The phenomenon is common enough. Every Maine guide knows it as buck fever. They have all seen novices, brought face to face with a harmless deer, just paralyzed into inaction by their own excitement.

And just so did Peterson stand, motionless.

He was aware of a great gray horse, almost upon him; frantic with fear and utterly unmanageable, as are all horses when they scent a lion. He was acutely conscious of a khaki clad figure that slipped from off the horse with a great pistol in its hand; as it slipped, the other hand dived into a saddle bag and appeared with another pistol.

The yellow face in the grass gave forth a short coughing roar and suddenly began to grow rapidly larger as the beast advanced in the scrambling rush that is a lion's charge.

Crash! The pistol in the right hand roared in front of his eyes.

The glaring yellow face charged ahead with appalling speed.

Crash! The pistol in the left hand.

Still the yellow face came on with frightful determination.

Crash! Crash! Crash! Right, left, right.

The hurtling face hung lower in the grass now. Plowed through the scrubby tufts. Slid forward in the dust. And then at last stopped, not ten feet distant. A great claw reached forward with its last ounce of strength and dug five deep furrows in the ground in its unquenchable determination to achieve its end. Then the yellow bulk was still.

Peterson heard the khaki person's voice at his side.

"Hm. That's as near as I care to have them come. And what you've gotta do, friend, is up and give your gun bearer a stiff dozen cuts of kiboko. He should have been behind you and should have fired when you quit functioning. You're new, I guess. You'll be the new consul, won't you?"

Peterson began to come back to life; but words came haltingly as yet.

"Why yes, I—I'm posted at Moyale. I—by Jove, I owe you—I have to thank you for my life. I—my name's Peterson."

The other grinned tolerantly at his confusion, though he made no move to respond to Peterson's self-introduction. But Peterson expanded under the kindly grin. He began to notice things. He saw a man tall and wiry and brown, exactly as had been those turbulent hunters of the Williams Hotel in Nairobi. This one had, perhaps, a wider and harder mouth than some, and looked at the world through amused, unwavering gray eyes. Words came to Peterson with a rush.

"I'm really most awf'ly obliged to you. I don't know how to say it; but—frightfully sporting of you. Just with a revolver. If you hadn't barged in like you did I suppose I'd have been pretty sick by now. Jolly plucky thing, I call it."

The other still grinned amusedly, and there was easy banter in his mimicry of the youngster's idioms.

"Not so frightfully awfully, don't you know?"

Peterson's speech was as his national, religion—established. That was the way people talked, of course. Everybody talked like that; that is to say, all sahibs. It could not occur to him that it might sound curious to a mere foreigner. And anyway, he was still too confused to notice any trace of amusement in the other's voice, which was going on in, easy explanation.

"I saw this fellow slide down off a rock kloof and take after you. But you were so blamed intent on your stalk that you never looked around. That's a rule of the bush, my boy: never stalk more'n a hundred yards without looking to see that you're not being stalked yourself."

"But I—I never thought—" stammered Peterson.

"Yeah; so I could see. So I lit out after you. I wasn't out for meat—just covering distance—so my gun boy was trailing along somewhere with the shenzis; else I might mebbe have scared this beggar off with a couple long shots. I was aiming to scare your pair of buck away at long range so you'd sit up an' take notice. But you sure were sot."

Peterson thought guiltily of the unworthy motives which he had mentally ascribed to this shooting maniac, and he murmured something again about its being jolly sporting.

The gray eyes twinkled at the persistent Anglicism.

"Mm-hm. A coupla Colt .45 guns throw a pretty heavy punch at close range. Heavy enough for Mr. Simba—if you don't miss. But all the same, another rule of the bush is: never to go out in lion country with less than a .145 rifle; and if you've got one of your first class British .157's, so much the better."

A powerfully built native with a rifle slung over his shoulder came up leading the runaway horse. The man looked at the dead lion without emotion, taking it as a matter of course, but the horse plunged and snorted with white staring eyes at the body. The man declaimed something in the sonorous Galla tongue, which the khaki person answered quickly. Then he said to Peterson:

"You'll excuse me, I'm sure. I've let my safari out of my sight for longer than I like. I must be after them, or God knows what monkey foolishness they'll likely pull off. That's another rule. Always watch your own safari. I'll leave my gun boy with you. He can skin your lion. I guess you'd like to keep the pelt as a souvenir of your first meeting with one."

He climbed into the saddle as he spoke; and Peterson noticed for the first time that it was what he would call a "Mexican," which, to his inherited insular prejudices, seemed a curious and clumsy thing; although it is the most comfortable saddle in the world for hard work. He felt that this parting, after what had happened, was astonishingly, almost scandalously, informal; and his mind, struggling to do the right thing, fell back upon the standard convention of his kind throughout all Africa and the East.

"I say—er—won't you come and have dinner at my bungalow tonight?"

The other called over his shoulder:

"Thanks much. I'd like to. I'll be overnighting in your town and it'll be right nice."

And Peterson realized that he did not yet know his deliverer's name.

THAT dinner was a memorable one to Peterson. It was crammed full of

information; about natives, about beasts and their ways; about safari

travel; about that mysterious independent country, Abyssinia, to the north.

And somehow the information carried a different impression to Peterson than

that handed out by Sanford. It was not laid down as gospel as was Sanford's;

it was easy, rather, and anecdotal; yet it carried unquestioning

conviction.

But Peterson was forced pointedly to ask his guest his name.

"I tried to get it from your gun boy," he explained, "but he didn't seem to understand my boy's language."

The other laughed.

"Oh, my name? Didn't I tell you? Smith—" and the unwavering eyes looked into their host's with such steady effrontery that they almost carried complete conviction. "But you'll get nothing out of my Gallas. They're top hole people, the Zulus of the North. They darn' nearly cleaned up Abyssinia once; and the Abyssinians are fighters, let me tell you. They licked the tar out of the Italians in 1906 and took a war indemnity out of them, as I suppose you know. But the Gallas may clean them up yet. All my boys are Gallas, though I use Woitos for porters. Gallas are too proud to port."

Peterson was just then too intent upon other absorbing topics to notice incidental details. Smith was all that he needed to address his guest. His experience of the afternoon was fresh in his mind. He wanted to know about lions, how to shoot them, where to aim; everything, in fact, to avoid a repetition of his so nearly disastrous experience.

Mr. Smith was immediately serious. Lions were always a serious matter. Nobody knew what they might or might not do. They might run like whipped dogs for no reason at all; or they might crouch in lordly indifference to everything; or they might charge with terrible ferocity for no reason at all. One had to be ever alert and ready for every eventuality.

"There's only one way to shoot lion," said Mr. Smith. "On foot; a good heavy gun; a good gun bearer with another gun; and a good nerve. Heart or head shot if you have time; and if he charges, hold your ground and slam him on the white spot on his chin, and keep on slamming him as long as he keeps coming. That'll smash the jaw and plow up the chest and vitals. And if you don't stop him with all that, say your prayers."

The twinkle began to grow again in the quiet eyes.

"There's another way, though I don't suggest it to you. That's the way of a lot of your lordlings and our fat millionaires who come here on picnic parties to get photographs of their big game trophies into the home rotogravures. Shoot them right out of automobiles with the engine running for a quick getaway. There was a well advertised American Amazon who came out and slaughtered five lions that way. I believe she had a barbed wire fence round her car too. Vreeden took her out from Nairobi and he told me about it."

Peterson remembered something about that story and the disgust it had left behind. There was much more that he wanted to know about lions before he turned to another subject of mystery. That great gray horse, the miraculous presence of which in this tsetse fly country had undoubtedly been the vehicle for saving his life. Mr. Smith's ready grin was full of pleased reminiscence.

"Ah, that's a whole story in itself. You've heard about this new German dope, haven't you? Invented by the same wizard who discovered that plasmochin stuff that the German drug people are boosting to knock the spots out of quinine for malaria?"

Peterson had not heard.

"No? Why, it was tried out right here in Kenya. This big medico prof produced it and claimed that it was the absolute goods for sleeping sickness and horse pest. So of course all the other medicos who hadn't discovered it said they were from Missouri. So the old prof showed them. He came out here and let them infect a hundred horses and mules and round up a hundred sleepy niggers; and he injected them with his bugs, and the whole darn' bunch recovered. Then the other medicos just about kissed him and said that this was an epochal discovery for the whole of Africa and, in fact, for the whole world. And the prof said, 'Yes, and we'll give it to the world when the world gives us back our colonies.' And since then they've guarded the stuff like radium. Nobody can get it for any price."

Peterson was absorbed. What a world of romance there was in that simple little tale. He recollected now having heard something about it. It was true. Highly placed personages, saddled with the burden of making safari arrangements for even higher placed personages, had tried officially to obtain some of the precious stuff in order that the mighty ones might ride rather than wear out the august shoe leather upon the burning plain. But the fiercely patriotic scientists had remained grimly deaf to their wiles. How, then, had this coolly smiling person managed to—Peterson blurted the question. Mr. Smith shook his head.

"Mm-mm. No, that's a secret deep and dark. Suffice it to say that the prof who demonstrated brought more of his dope than needed; and that there have been mixed into the subsequent story two Armenians and a Greek trader and a Portugee; and the Portugee won't even tell his father confessor. Enough that I've got enough of it to have a horse in tsetse country."

IT was a long and intensely interesting evening. Midnight pointed from the

round tin alarm clock on the mantel shelf before the raconteur of stark

adventure in the first person got up and knocked his pipe out at the open

window. Peterson's heart welled over with friendliness toward his guest, so

that he felt constrained to offer him that rare privilege—official

assistance in so far as might be possible.

In East Africa safari porters have been so spoiled by extravagantly conducted parties, and their own needs of life are so small, that they can afford to be more than merely independent. A friendly government official can do much with local chiefs to fill out a crew depleted by desertion and the simple native disease of, "Me sick. Ow-how pain im gut, no can go." Which sickness always occurs near a large and comfortable village.

But Mr. Smith was easily independent.

"Thanks much; but I guess that I can scratch along all right. None of your overpaid one-shilling-one-day shenzis for me, with a paternally dumb government ready to back them up in skipping out of a contract as soon as they set up a howl of forced labor. No, sir; I use Woitos. He no work, bimeby I tell him he chief, he catch kiboko. And in my opinion that's the only way in which the African can be made to understand that he's taken up a contract to do a certain job for a certain length of time. Thanks all the same. I guess that I'll be away with my outfit before you're up tomorrow. Going eastward along the border. Guess I'll be running into your big chief, the deputy commish, somewhere along the line. So this'll be goodby, till our trails maybe cross again sometime."

Peterson lay awake far into the morning. His mind was too full of jumbled events to permit sleep. The startling day, the fascinating talk of the evening, the things he had learned—all these went racing through his brain in a confusion of vivid pictures.

And as they raced, thoughts began to take form. Idle guessings; vague surmises. This man Smith. What a colorful personality! What an impression of quiet force that laughed at the world and—with rueful admission—at most people in it; or rather, to be more accurate, at some of the people in it; prominent people! That innocent allusion to the "big chief." Surely there had been a hint of raillery in the gray eyes at the unnecessary adjective that qualified the word chief. Still, this man was an American; and you never knew just what their queer speech meant. But then again, that abbreviation, the commish. That was hardly a respectful way to speak of so important an official of the Colonial Government. But this man was very clearly no respecter of persons.

The unformed ideas, as they raced along the tide of thought, began to cluster themselves round this strong snag of outthrust personality and to take form. Mere shapes at first; but presently connecting incidents drifted in and began to mold the whole. Where had he heard a description that seemed to fit just this Mr. Smith?

Peterson struggled with that vague memory for awhile, and then suddenly the picture flashed through to him. The big room in the Williams Hotel. Sanford, flushed and furious in his importance. And a voice that spoke of a man who knew much about lions; who knew, in fact, what a lion would think. A man who got things done without making a fuss. A man who scorned official favor. All these things fitted this Mr. Smith most marvelously. Peterson felt pleased that he had connected up this identity.

And then suddenly the drifting thoughts bunched together into a monstrous shape, a thing of horror.

Peterson was suddenly wholly awake. Good gosh! This man about whom the argument had waxed so hot in the hotel had been that infamous slave runner fellow. This Smith couldn't be that fellow. It was too absurd. This was a splendid chap; one of the very best. And that other fellow—King, the name was—he was dead, of course. Sanford had verified that story himself.

Peterson was pleased that there could not be any sort of connection between this top hole chap and that other frightful character, that fellow who was, of course, quite dead.

But then again the insidious reflection that this man was obviously what Sanford had called a damned Yankee forced itself. And he had come down, on his own showing, from Abyssinia and—was his name really Smith? It had seemed almost as though—

There was no hope of sleep for Peterson that night. He tossed in his bed, torn with doubts; in a quandary of conflicting emotions; divided against himself in a maze of thoughts through all of which the word duty loomed.

With the morning Peterson was pale and ringed under the eyes. But his lips were set. He went straight into his little office and did a very curious thing, difficult to understand; for he was really a young man of the best of ethics. He wrote a laborious letter, full of explanations and fears and apologies; and then, summoning his East Indian office clerk, he instructed him to turn the letter over to the official messenger with orders to convey it as fast as he knew to the camp of the deputy commissioner, a full week's journey distant to the east.

Difficult it is to understand this conduct in a man of normally decent tendencies; yet understanding is possible. For the service of his country in his own little sphere in that far flung corner of the world, Peterson felt that his superior should know of the monstrous suspicion that had occurred to him, and of all the facts relating thereto.

The man Smith had undoubtedly saved his life and had otherwise impressed him as being a splendid type of man. But duty, as he saw it, demanded that he report his suspicion to his superior. And so his laborious letter, tied into the crotch of a split stick, went off by a runner with instructions that it be delivered swiftly and with all the blundering secrecy of officialdom.

THE man Smith sat in the shade of a giant fig tree whose broad, flat roots

arched down a shelving ravine bank to a muddy little stream. Packs strewed

the ground. Porters lounged in the uncouth attitudes of the African; some

with ox stolidity chewing a few grains of their day's potio, some

lying flat on their stomachs in the blazing sun, as heat proof as

lizards.

Many hundreds of little white whiskered gray monkeys chattered in the higher branches of the great tree, feeding on the dusty, rather tasteless fruit and performing all the half human antics that make monkeys so fascinating to watch.

Mr. Smith lay back to smoke his after lunch pipe and watch the monkeys with a lazy smile. He was conscious of his head gun bearer standing waiting for permission to speak. He knew that something urgent was on the boy's mind, but he knew his African well enough to know that his own dignity demanded that he let the boy wait awhile before he said with stupefying omniscience:

"Well, Baroungo, it is in your mind to speak of that messenger who runs from the consul bwana, to the dipty c'mish bwana; yes?"

"Hau tamwaku! How does Bwana know one messenger fella run with letter?"

Smith's eyes twinkled. It was always good, whenever possible, to impress one's African boys with a sense of one's hidden knowledge. As a matter of fact his bluff was based on a shrewd guess. He knew his official as well as he knew his African, and he was just about sure that young Peterson's tortured conscience would send a letter; and it was for just that reason that he had made an excuse to leave one of his boys behind at the last village with orders to bring on some native tobacco which would take a few hours to prepare. All this was a simple subtlety that went far beyond Baroungo's perceptions. The boy proceeded with his eager information.

"Danakwa he come long bring tobac; he tell one messenger come quick-quick, got letter go for east. That man run sof'ly-sof'ly now 'long that side."

He pointed with his chin beyond the next low parallel swell of the plain.

"Hm," the white man commented half to himself. "That letter must be stopped."

"Yes, Bwana. Two spear man stand ready for run; stop um one time."

"Mm-mm. Your enthusiasm is commendable, Baroungo; but it carries you too far. He mustn't be killed. He must lose that letter—without force—or he will have a story to tell. He must lose it through his own carelessness. Then he will sit in some village for a week or so and will go back and say that the letter is delivered and that there is no answer; and the consul bwana does not as yet know how to get truth out of him."

Baroungo was once more impressed with his master's wisdom. As an African himself, he knew that that was exactly what the messenger would do.

Danakwa was a good man for that thing, he agreed, though with reluctance; and added almost in soliloquy—

"All same one messenger if he die through own careless, he no tell lie, no tell true."

"You render a good paraphrase of a trite axiom, my good Baroungo," said his Master. "Many wise men have so thought before you; and white men at that. All the same you let Danakwa understand that if that messenger dies through anybody's careless, there will be kiboko. Send Danakwa to me anyhow. But first, what talk have you gathered from the villages about Matteo bin Ibrahim?

"Talk is, Bwana, that Ibrahim go by way Dawa River; he got plenty people his chain, mebbe one hunda, two hunda fella."

"Dawa River, hm? That's faster than we thought. Double trek from now, Baroungo, else we won't meet up with him. Tell the men plenty work four, five day, one piece cloth backsheesh.Bustle. Send Danakwa here."

DEPUTY Commissioner Sanford was in camp near the Dawa River. In the most

secret camp that he knew how to devise. The Dawa River formed the border line

of that angular point of Kenya Northern Territory that wedged itself in

between Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland. It was a curious river of tumbling

rapids and sluggish, miniature lakes; full of great barbeled catfish and fat,

pinky-gray hippopotami, which by their pig-like tameness indicated that this

last wedge of British territory was a very isolated place indeed.

Across the river to the north lay Abyssinia; a good six weeks' journey from the capital Addis Abeba, and therefore as isolated as the neighboring British wedge. To the south was another sluggish river, full of mud and crocodiles, called the Dukula, or Bushbok River. Beyond it the country sloped away to the deserts of Italian Somaliland.

The British wedge between the two consisted of country cut up by deep dongas with perpendicular sides; dry, sandy bottom just now, forming long, winding concealed tunnels along which one might travel for days without exposing oneself on the plain. Good country in which to hide.

Farther to the east the Dukula River converged upon the Dawa at a mud village called Mandera. Important to Sanford, because it marked the extreme tip of the Kenya Northern Territory wedge, and stationed there was an outpost guard of a quarter company of King's African Rifles. Good men, recruited from the best of the fighting tribes of Africa and splendidly trained by the hard boiled type of individual whom Kipling has named Sergeant Whatshisname.

Deputy Commissioner Sanford's safari was encamped in the bed of a deep donga. It had traveled along the beds of ravines for many days. The few natives who had shown their fuzzy black heads over the donga edges during the march had been immediately seized and compelled to stay with the cautious expedition. This was drastic and opposed to the regular colonial policy of pacification. But it had been vitally necessary; for, had these nomads been permitted to go, they would have jabbered the news of the secret safari all over the countryside.

The need for all this secrecy was that Deputy Commissioner Sanford had received news that somewhere on the other side of the Dawa River, in Abyssinian territory, lurked that arch-scoundrel, Matteo bin Ibrahim, working his way east with a big train of slaves. If the deputy commissioner could contrive to lure Matteo across the river into British territory before he passed Mandera, he would have him on the hip, red handed with the goods; and the menace of Matteo would then be safely disposed of in a good colonial jail for a few years.

If Matteo were once to pass Mandera before he ventured out of Abyssinian territory, he would be safe; because then his jockeying back and forth would be into Italian Somaliland; and Sanford's opinion about the Italian colonial administration would have given shame to a good ape.

Sanford's hope, therefore, his anxious dream, was to lure the slave runner across the river before it would be too late. The lure consisted of some forty runaway slaves whom Sanford had rounded up and was holding as bait.

A K.A.R. man, a thick lipped Shankala with crisp woolly hair, had been carefully coached to go across the river posing as a dull witted runaway, to let himself get captured by Matteo's men, and then to tell the tale of the two-score other slaves who huddled in a bewildered heap on the British side.

It was a good trick, and it ought surely to work—if no news of the careful ambush should have leaked across the river. Sanford had taken every precaution. He had traveled only in ravine bottoms; he had sternly suppressed all loud speech—which, with an African safari, is close to a miracle. He had done more; he had even prevented the howling of interminable wordless songs at night, which proclaimed Sanford, in his way, a great man.

EVERYTHING had been done to preserve secrecy, and Sanford was almost

sanguine, this time, of the results. With Matteo stowed away, the principal

menace of the border land would be removed, and all those slaves could be

released to their own devices, free and unhampered—which would be, in

ninety per cent, of the cases, to drift about aimlessly near the border,

yearning with animal instinct for the pasturage they knew, till they would be

gathered in again by some swift raid of some alert scamp who followed in

Matteo bin Ibrahim's footsteps.

The other ten per cent, would return of their own accord into Abyssinia, nurturing some dull idea that this time they would be able to hide away in some isolated village among people who talked their own language and who lived in the same unworried state of insanitation to which they themselves, by long years of heredity and personal inclination, were so lovingly addicted.

The much harassed deputy commissioner thought that he saw success; therefore he was startlingly and disagreeably surprised when a frightened boy stood before his tent and chattered that abwana isana was coming to visit him.

"What's that? An important white man? Who the— Do you know this man, N'goma?"

The boy had been with Sanford for a long time and he knew most of the white men in the Northern Territory by sight.

"Bwana," he chattered. "I do not know this man; but it looks like the ghost of that Kingi Bwana who was eaten by a lion."

"What the blazing devil!"

Sanford was out of his cot as fast as a lightweight, and at the flap of his tent. And there his incredulous eyes saw a sight that dropped his heart like lead down to his veld boots—the man Smith strolling unconcernedly toward him through the middle of his carefully hidden and guarded camp. The man grinned at him with cheerful effrontery.

"Hello, Dip'ty C'mish. Howya? I'll bet your boy told you I was a ghost; he scuttled from me like a jackal."

Sanford's gorge rose; that is to say, his heart climbed slowly up from his boots until it stuffed his throat. This beastly apparition meant, he was sure, the end of everything. All his careful plans; all his precautions upon which he had so plumed himself; his whole long and arduous trip—all gone by the board.

The shattering of his hopes was too complete and sudden to be realized all at once. He was conscious only of a leaden hopelessness that crushed overwhelmingly all further action. On top of it all mounted slowly a growing rage; and directed, with that curious dominance of trivialities that asserts itself in times of crisis, not at the upsetting of all his plans, but at the comparatively unimportant matter of the man's easy familiarity toward him.

The dignity of his official position demanded a respectful address from all but his intimate friends—who were very few; and required a "sir" from all subordinate officials. And here was this unspeakable foreigner addressing him with cool insolence by what he knew in his secret heart was the term which the natives used in speaking of him.

Many men in Africa, most men in fact, have been content to accept their native titles and to let themselves be so addressed with a laugh, hoping only that the shrewd characterizations thus implied might not be too insulting to their amour propre. But the deputy commissioner was that type of aloof official that never unbends. Personal respect is their religion. And here this particular bugbear of his addressed him as "dip'ty c'mish." Yet all that he could voice just then was his poignant disappointment in the blurted words—

"I thought you had been killed by a lion."

The man grinned with wrinkled nose in enjoyment of a successful coup.

"Yeah. It was necessary for my purposes that certain people should think Kingi Bwana was safely dead. I drilled those two Kavirondos in their talk for a good week before I sent them out. Did you think that they sounded fishy at all?"

THE ruddy choler began to rise to Sanford's face and the veins in his thick

neck swelled. So he had been made a fool of by a brace of Kavirondo savages?

He, the deputy commissioner of the district, who had gone to the trouble in

his eagerness to question them himself, and had convinced himself to his own

official satisfaction that the circumstantial tale was true. And there stood

the very man who had engineered the hoax, lean and hard and disgustingly

healthy, grinning widely over his scheme.

But the fellow did worse; he heaped insult upon the already grave injury to Sanford's pride in his own acumen. He fished a crumpled oiled silk wrapper from the breast pocket of his khaki coat and unrolled it with little clucks and sighs of complaint.

"I just dropped in to bring you a letter that your consul bwana at Moyale was sending; his messenger very carelessly lost it. I fancy he got suspicious about me. Shows perspicacity. You got the makin's of a good youngster there, Dip'ty Bwana. 'Fraid it's kind of wet, 'cause I had to swim that filthy river—must have been raining somewhere back in the hills there. And you just can't keep these darn' pouches leak proof, for all the lies they advertise. Dammit, my cigars are all damp too—have to pull like a vacuum cleaner. Don't mind if I sit down in your nice shiny new camp stool, eh, and powwow? Pah! My matches are just about melted. Boy, bring fire for light cigaroo!"

Deputy Commissioner Sanford choked and red swam before his eyes. And there was where he made a great mistake. There was no real reason for so much anger. Kingi Bwana—had been scrupulously polite. No fault could be found with him on that score. In fact even Sanford, if he had taken time to think, would have found it difficult to say for just what reason he was finding fault. But he did not think.

It was sufficiently galling that this man who, he was assured, had been a thorn in his side throughout nearly two years of endeavor, should be standing there, safe and alive and so damnably sure of himself; that he should have known, as he apparently had known, all about the carefully concealed safari all the time; that he should have strolled so easily into the very center of the camp in spite of all the precautions of armed sentries; and to cap it all, that he should have been so exasperatingly familiar, so utterly wanting in respect.

That last was a charge which might with justice have been brought against King. And he, for his part, would instantly have admitted it. His perfectly unaffected question would have been: just what was there to respect? An official position? A large man who could not control his temper? He was willing to treat anybody as a free citizen and an equal; but was he to come and kowtow? That was far from King's way. He was blood brother to those sturdy hunters in the Williams Hotel who kowtowed to nobody.

"Let's sit and have an indaba, Dip'ty Bwana. I've got a proposition to make to you."

The serene effrontery of the suggestion gave words to Sanford. What the proposition might be, he never stopped to consider; he was assured in advance that nothing but infamy could come from this man who, he was convinced, was a partner in the foul business of the halfbreed whom he had been hoping to catch. Burning words gushed from his throat.

"I want to hear no propositions from you, Mr. King. I want to have no dealings with you. I can have no sort of connection or compromise with any beastly thing that you may ever do without befouling myself. The bestial trade that you ply makes you unfit to talk to a decent human being—"

Such, and many more, were the scorching words that tumbled from Sanford. His face swelled and he sweated as he poured out his denunciation.

And it was therein that he made his great mistake. Kingi Bwana had come in peace to make him a certain proposition which the official might very well have accepted. He had come unarmed, having left his weapons somewhere on account of having to swim the river. That in itself should have been sufficient evidence that he had not come with any wanton thought of making trouble. But Sanford's hysterical hostility quite naturally repelled him. What the deputy commissioner's official acumen had convinced him of or had not convinced himself of was no business of King's to inquire, or to explain away.

He was—thank God, he thought—free, white and twenty-one. Above all, free; no bought and paid for official, sworn under oath for all the rest of his life to let unseen superiors in distant places do all his thinking for him and shape all his future deeds according to rules in a book. He was no enslaved subordinate to Sanford, to have to pander to the man's pompous ego, to explain his comings and his goings and to justify his doings.

The deputy commissioner's attitude had suddenly made the relationship between them acutely personal. Not the most reckless of the hunters at Nairobi would have spoken to Kingi Bwana in that manner without being ready to back up his words with something very much more substantial than talk. King remained sitting in the camp chair and sucked prodigious puffs from his damp cigar. He still grinned, though now only with his lips; but his long legs lazily drew up and tucked themselves under the stool, and his feet shuffled away the loose pebbles and sand from under them.

"Mm-hm," he mouthed over his cigar. "Seems like you don't' like me so much. Well, Mr. Deputy Commissioner Sanford, what d'you figure you dare to do about it?"

Let credit be given to Sanford. His neck veins distended more purple than ever. His shoulders hunched—and King braced his feet for a quick spring.

BUT no fight was to take place just then. The K.A.R. sergeant came up on a

run, saluted quickly and, so important was his communication, that he plunged

instantly into a whispered gabble. Sanford's first impulse, in deference to

his official dignity, was to push the man from him, curse him for his

impudence and make his rush at King. But a phrase of the whispered message

caught his ear. It arrested all other action. Without word or look to King,

Sanford caught the sergeant by the arm and strode several paces away. King

remained sitting, pulling at his cigar with an affectation of exaggerated

enjoyment. Sanford demanded fiercely of the sergeant:

"Now what is this story? Tell me straight and quick."

The sergeant replied in urgent undertones:

"Sar, this thing true. One scout come, he say Ibrahim come cross river by Malolo boma; sof'ly ask news 'bout this side slave. This scout my man. He see Ibrahim self; got three, four man with. He run one time bring news."

Sanford's heart jumped. Fate, it seemed, in spite of this King fellow, was playing for once into his hand. It looked as though, deprived temporarily of King's clever brain, the other arch scoundrel had made a blunder. It was Sanford's chance to leap upon this misplay. If Ibrahim were indeed on the British side, as seemed to be miraculously true, the thing to do was to march immediately with every available man and to cut off his retreat. Sanford hardly hoped to surprise the crafty old villain in a native thorn fenced village where some chattering fool would surely give a warning. But, the man's retreat once cut off, the chances were good of rounding him up before he could get back.

Sanford commenced to give quick orders to the sergeant to get all his men ready for immediate trek.

And then cold lead suddenly dragged his flushed hopes down to dead bottom. His eyes fell upon King, sitting coolly there, puffing at his cigar patiently. That pestiferous thorn in his side hampered his every move, even here! What to do with that menace? If he were to go off suddenly he felt a chill certainty that the man would contrive in some way to outwit him and to convey a warning to his partner. Sanford's mind raced over the pros and cons of the situation.

What the devil and all could he do? Arrest him, the thought came. But on what grounds? He had no evidence. As the voice in the Williams Hotel had jeered, he would need a lot more evidence than this mere personal conviction. It was against all precedent of law to arrest a man without a single grain of evidence; and Sanford was stanch British official enough to respect the sacrosanct law. Yet the need was desperate. The man must be disposed of.

Suppose he were to manage to arrest King, and to quarrel through the legality of the action later in the Nairobi courts—what a howl would be raised about that by every turbulent free citizen in the whole colony! But suppose, in the furtherance of his duty, he were to do the thing. What would he do with his prisoner?

Bind him hand and foot? The thought lingered hopefully, but found little encouragement. Sanford had an uneasy respect for the capabilities of that coolly efficient person whose reputation was that he got things done the way he wanted. People had been tied up before by experts; and sometimes, somehow, some of them had contrived to escape. This man looked uncomfortably like one of those who would contrive.

Desperately, then, he asked the sergeant—

"How many of your men are necessary to guard that man?"

The sergeant covered his mouth with his hand as he gasped at the thought.

"Awa! To guard that Kingi Bwana? M'beku! That man like devil, sar. He know witch magic. Ten, fifteen men for guard that fella."

So that was the sergeant's opinion of it. Sanford plucked at a button of his shooting coat in his quandary. His nerves, already ragged, were beginning to get the better of him. Instant action was necessary if he hoped to catch Ibrahim; and that man sitting stolidly there, as hard and unconcerned as a stone, was driving him into a frenzy. But the sergeant had an idea to propound; an idea born of Africa; one that had, upon occasion, stood the test of practise.

"You want know what do with that fella, sar? I tell. Batta boma, two hour fum heah, Malolo road. Got plenty trouble with lion. Batta fellas got one lion trap. Puttum this Kingi Bwana lion trap inside. He sit comf'ble shuah till you fetch."

SANFORD walked back to where King sat, still enjoying his cigar. The deputy

commissioner's lips were set and the blood had ebbed away from his face. He

was going to do an unexpected thing. In fact, a quite brave thing. The more

one sized up the man King, the more uncompromisingly hard and physically

efficient he looked; and Sanford was ruefully conscious of his own

unnecessary weight, though he had lost much during the course of his

strenuous expedition.

But the thing was necessary The effectiveness of the little K.A.R. force would have to be conserved as much as possible. He could not afford to have a sick and disabled list. It was up to him—it was his duty—to keep King in play and to hold all of his attention for as long as might be possible. Sanford therefore walked up to King with his lips set and commenced the play.

"Well, Mr. King, you were going to say something I think, when I was interrupted."

King's eyebrows lifted. He had not given Sanford credit for this. His feet gathered under him again and he said:

"Your move, Dip'ty Bwana. I asked what you figured you dared to do about things."

Sanford moistened his lips. King was so coldly direct. There was to be no time gained holding him in play with words. The actual physical play would have to last longer than Sanford had hoped. But he faced his trial.

"I dare, Mr. King, if you dare to stand up to me, to put into practise what I think of you."

King suddenly grinned widely.

"Good for you, Mr. Commissioner. I'll hand it to you. As for me, I take back some of the things I thought. If you like, I'll shake hands before we start in to argue."

But Sanford was not going to descend to that familiarity. He detested everything he had ever known about this man, and he felt that he degraded himself by this personal conflict which he had forced himself to undertake only on account of its desperate necessity.

"That is not necessary," he said shortly, and took off his coat.

King, unhurried, looked him over appraisingly. He saw big shoulders and broad chest, massive looking legs, sturdy calves beneath the puttees; and under the shirt, below the broad chest, more of a protuberance than an altogether healthy stomach needed.

"Humph," he commented impersonally. "You've lost quite some weight, haven't you? All the same, you won't be aiming to drag this out to an endurance test. Guess your game will be rush and slug for a quick finish. Got about thirty pounds weight on me, eh? What d'you run to? 'Bout two hundred and ten? I ought to scale around one eighty-five. That's not too much weight to give away, 'cause I'll bet I'm a lot faster on my feet. Tell you what. I'll bet you fifty dollars on the side I'll outlast you. What d'you say? Just to make it interesting."

Sanford's anger began to rise again. This unspeakable person harbored the persistent conviction that he could meet a high government official on a basis of equality. The very idea of the proposed bet was an insult. Besides, Sanford was not going into this thing with any reasonable hope of winning; he knew, better than the other could guess, how short he was of wind. His plan was no more than to keep King's attention fully occupied for as long as possible. He would gladly have strung out a little time in preliminary talk. But King slipped out of his coat with a sinuous movement of his shoulders and began to glide, to prowl rather, round him with the alert intentness of one of the greater felines.

"Don't care to bet?" he purred regretfully. "Well, all right. Up to you to start. My game'll be to tire you out."

BUT Sanford did not know where to start. He had little confidence of being

able to land on that gliding body anywhere. It was King who commenced. Like a

leopard leaping at an opening it has seen, King came in. There was a swift

sound of two short steps, and—smack-thud-smack! Face, body and

neck, Sanford felt light but stinging blows. He drove a heavy right at the

face in front of him, and hit only an open hand; and then, smash! The

hardest fist he had ever met slugged in under his ear.

Sanford's head buzzed and water welled into his eyes. Through the haze he discerned the face again, head thrust forward, peering at him through searching eyes. The impersonal voice came once more.

"Shucks. Just a little too far back. I sure wished you that one on the end of the jaw. But you're slower than I thought, brother. I'll give you odds on that bet if you like."

The water in Sanford's eyes became oddly streaked with running flashes of red. That last blow had stung and—curse the fellow, he fought apparently without the least animus; as if he were engaged in a boxing bout with a friend, damn him! And the way he dissected one's capabilities was an insult. Brother!

The swimming eyes saw something beyond King's back—the sergeant and some ten of his men gathering for the rear attack. They had come sooner than he expected. Here was where he had to engage all of King's attention. He drew a deep breath and rushed, slugging with both hands. The heavy fists met flesh; hard flesh of arms and elbows that thrust the blows aside. Something hit him with sickening force in the throat, though not hard enough to stop him; and then he clung in a clinch. Quick hands covered his arms and the hated voice breathed upon his neck.

"How d'you want to do this? Hitting in clinches, or a clean break?"

Sanford answered nothing. For one thing, his throat muscles were numbed by the blow; and for another, the need for speech was past. He clung desperately in his clinch, all his energies devoted to just holding his opponent harmless.

And then clutching black arms and a hell's uproar enveloped them both.

From King came a sharp hiss of intaken breath, a gasped, "You filthy crook!" And then he fought in earnest. Like a monstrously magnified attack of ants upon a hard shelled beetle that fight was. Except that the heaving black mass howled. To the African, as to the ape, fight and noise are coincident. The one can not exist without great volume of the other. And in this case the Africans had to bolster up with noise their courage to attack a man of whom they were mortally afraid.

Every now and then above the din rose a high pitched shriek of anguish as the overwhelmed victim found opportunity to apply some especially venomous means of hurt. The strong odor of unwashed Africa hung in the still air of the donga. But gradually the heaving mass of flesh began to struggle with less and less violence. The end, with such odds, was as inevitable as when the driver ants make their battles.

Slowly the fight subsided. Already rope was in evidence. Presently Sanford backed out of the mêlée, disheveled, clothes torn, but elated. One after another the natives stood back, rolling white eyeballs and champing protruding lips. The atavistic impulse to rend with strong teeth was barely suppressed. One squatted, hugging a twisted knee and moaning as only a native can moan; another, with screwed face, nursed a wrenched shoulder. Minor injuries were many; but the end that had been gained amply repaid the cost.

King, the redoubtable Kingi Bwana, lay exhausted. Swathed positively with ropes; foul smelling, greasy cords that had been used for heaven knew what filthy purposes. His shirt had been ripped from him; his skin clawed and scratched; his mouth full of grit and dirt. A sorry figure.

He spoke no word. He looked with the one eye that was not closed with sand, as though impressing the faces of his captors in his mind. The men covered their mouths to prevent the entry of evil eye and moved out of range. Sanford's voice broke on the spell.

"Hurry up there now, Sergeant. Get your men together. You, Umgate, stay in boma with porters. All other camp boys come."

The start was surprisingly quick. Everything had been ready for days for just such a swift raid. Within fifteen minutes the little force was on trek. King, lashed to a pole like a captured reptile, was carried by four brawny soldiers in relays. He spoke only at intervals—with each new relay. To each unwilling four he said the same thing.

"Four men. To each one, four jackals, four hyenas, four vultures, four months."

It was gibberish. But the men groaned; and, as each one repeated King's story, horror and superstition grew. Each relay began to be more difficult to supply, till Sanford himself had to select the men and order them to their gruesome job.

King had no idea as yet just what use he could make of the fear thus engendered. He did the thing on principle. He knew that a frightened African was very close to a creature without reason; and he fired his shafts of suggestion at a venture, gambling in futures. In any case he felt not averse to making those Africans as uncomfortable as he could.

BUT no immediate fruit was born of his craft. The time was too short. Two

hours from the camp was the lion trap that the people from the neighboring

Batta village had built against the marauding beasts. King was still a

prisoner when they arrived. He knew, of course, from the babble of the

marching men, what the plan with regard to himself was; so his incarceration

was no surprise to him.

Sanford quickly inspected the trap himself in the fast falling dusk. It was in good condition. It would hold even Kingi Bwana in security. This matter had been worrying him throughout the march. But this trap was in such good shape that no time need be lost in making repairs. With a great thankfulness he turned to his sergeant.

"Good. Throw that goat out and put the prisoner in. On the ground will do—Good heavens! He's tough enough not to die of lying on a mud floor."