RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

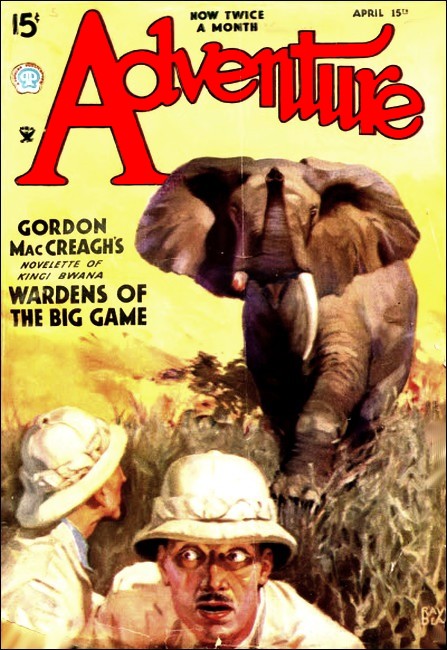

Adventure, April 15, 1935, with "Wardens of the Big Game"

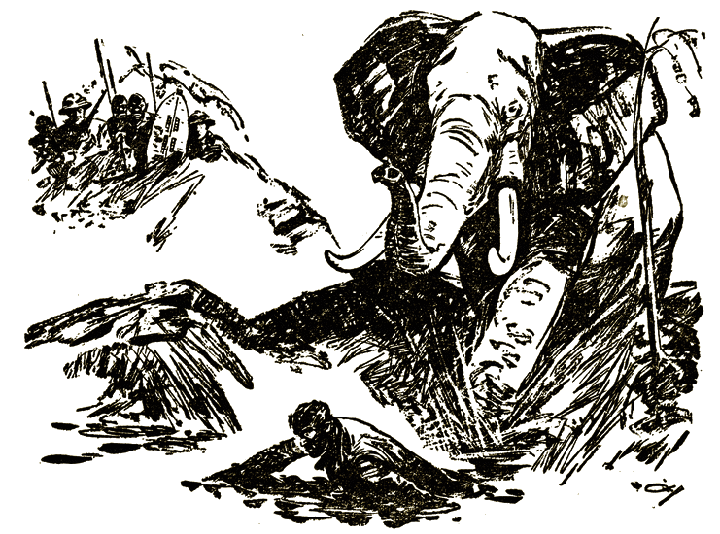

THE big elephant danced in his rage. He charged in thunderous short rushes, wheeled and thundered back. He flung his trunk high and screamed brazen blasts of fury. He stamped the dust to a yellow smokescreen. He tore up tussocks of dry grass and thorn bush and lashed them to shreds against his own horny knees in a giant frenzy of destruction.

Two white men and two black stood frozen in their tracks and watched him. Nothing separated them but two hundred yards of open veldt scrub.

King, big-boned and lean, frowned at the awesome spectacle through dust-rimmed eyes. With an adroit motion he juggled a stem of grass across to the other corner of his mouth and grunted:

"Plenty mad, isn't he?"

"Terrific." The district commissioner whispered. "I hope to heaven he doesn't wind us."

King nibbled his grass, tight-lipped. "He may not wind us in this heavy air. But he'll sure as hell wind that native village we left dead behind us."

The district commissioner moved his head in slow inches, desperately careful to attract no attention to their precarious position, cautiously surveying the immediate landscape for its scanty trees.

A fleeting grin cracked the caked dust from around King's wide mouth.

"Elephant eyesight isn't that good," he said.

"I think," the commissioner hazarded, "we might make that mimosa tree in a mad altogether rush."

King flashed one quick eye at it.

"Easy," he agreed. "But the native village will still be right back of us. And this big boy is mad enough to be considerable catastrophe to the heathen."

"Terrific!" The commissioner murmured again. "I wonder what so infuriated him?"

The grin passed from King's face. Only the lean, brown hardness remained. Angry disgust was in his voice.

"I can see from right here what's made him mad. Wait till he swings around and I'll show you."

The commissioner hissed a sudden intake of breath. "By Jove, he's got it! Watch him! He'll be down on us. Good Lord!"

It was true. A wave of sultry air, pregnant with refuse, crept up behind them and rippled the grass tops away out toward the angry beast's orbit of rampage. Instantly it stood tense, its ears flared immensely forward, its trunk high in the upper stratum of odors above the dust.

"Good God!" the commissioner repeated. "Run for the tree!"

King swung his rifle sling from his shoulder. Quite coolly he looked down to his feet and shuffled his boot soles to see that he stood on no loose rubble. His eyes began to narrow down in cold alertness and he eased a cartridge from the magaaine into the chamber of his big Jeffries .475.

One of the black men, a huge fellow, decked out with knee and elbow garters of monkey hair in all the superb nakedness of a Masai Elmoran, took a horn receptacle from the lobe of his ear, tapped snuff from it upon his great spear blade and sniffed it in a splendid gesture of confidence in his master.

The elephant was striding in enormous uncertainty, ears like fans, trunk stiff before it, questing the vagrant airs with massively vengeful purpose. Even at that distance its snorts of expelled air came like a steam exhaust.

The commissioner became suddenly official.

"Kingi Bwana, there's no need to shoot that elephant. We can still make the tree in safety."

King sighted for a moment along his barrel to gauge the sun glimmer on his sights. He lowered the weapon.

"Go ahead, if you want to," he said. "And better jump. 'Cause when he comes he'll make it in fifteen seconds flat."

"Mister King!" The commissioner was officially formal. "I forbid you. You deliberately refused an elephant license when we started out. If you unnecessarily shoot this beast I shall be compelled to fine you the government penalty of a hundred pounds."

King grinned, his eyes warily fixed upon the gray mountain of rage.

"I believe you damn tape-bound officials would do just that thing," he said cheerfully. "All the same I'm going to shoot it. For two reasons. One is that stinking native village behind us."

"Good God!" That realization broke through the commissioner's agitation. "The women will all be in their huts at this hour too. Shoot it from the tree then."

As before, the grin soured on King's face.

"You know damn well nobody can shoot a charging elephant from up in a tree. Not dead. Head on is the only possible shot. This poor beast has suffered enough already. That's the second reason. I'm not going to let it carry away a lot of useless lead."

The other black man, a Hottentot as small and wizened as the Masai was huge, clucked a quick warning.

"Angalia, Bwana. He has picked the scent. He is coming."

The gray mountain screamed its rage once more and charged down straight for the little group of puny humans. King shuffled his feet again and stood, his mouth and eyes thin, parallel lines.

Fifteen seconds! But to the commissioner they hammered in the agonizing rhythm of his slow, crawling pulse. Incredible man, this King, taking a blood-chilling chance like this. All on account of some inexplicable sentiment about that murderously charging beast having suffered something or other.

The thunder of its feet vibrated on the ground. An avalanche of hurtling flesh and billowing dust, it rushed enormously nearer. All ears and reaching trunk and wicked little red eyes.

But the commissioner held his ground alongside of King.

"Shoot! For God's sake, why don't you shoot?" he heard a cracked voice reiterating; and vaguely he realized it was his own. And coolly King's voice:

"Fifty feet is plenty good."

The mountain loomed immensely above them. A scream like a locomotive warning blasted the air.

KING lifted his rifle to his shoulder, held it a second,

and fired. Its roar cut the scream appallingly short. The

elephant's fore legs stiffened to the full ton impact of the .475

bullet. The barrel feet plowed parallel deep furrows in the

ground. Slowly, like huge brakes applied, they came to a stop.

The gray bulk swayed, fell over on its side as a mountain

falls.

Through the choking dust King was grinning tight-lipped at the commissioner. The commissioner was aware of his own voice again, high pitched and dry.

"Good God! Why didn't you shoot sooner? Lord, the thing was almost upon us! Is it out of sheer bravado that you do these things, Kingi Bwana?"

"Fifty feet," King repeated the rule. "There's a space no bigger than your open hand between the frontal bones to aim for."

He led the commissioner forward. "Look now." His voice was dark with anger. "See why he was so mad? Tearing around that way? He'd never have bothered us else. Poor brute."

At first the commissioner could notice nothing amiss. Then it came to him that the fallen beast had only one tusk. The other—where the other had been—was a mess of splintered ivory and a pulp of raw flesh.

"Good heavens! What a ghastly mess! How could a thing like that happen?" the commissioner wondered.

"It could happen," said King grimly, "only from a rifle bullet. From a bullet fired by a man who has skill enough and nerve enough to creep up close enough for a side head shot—and who could then be drunk enough to miss. So think that over. That's why I brought you all the way to this place when you said you wanted a big-game hunt. I wanted you to see what kind of thing was going on in the far ends of your district."

"But—but, dash it all, my dear fellow—" The district commissioner was bewildered—"how—who would be so lunatic as all that? Besides, no elephant licenses have been granted in this district. This is all under strict conservation."

King laughed harshly.

"Sure, it's under conservation; marked off on your maps and listed so in your office by an ex-Tommy clerk. You'd fine me a hundred pounds if I shot an elephant without a special permit or in defense of human life. A good ruling. The game needs it, and every decent white man is all for it. A nice piece of legislation—but do you know how many, many loads of first-grade scrivelloes and prime hard Mohammed Ali the Banyan trader shipped out of here last season? All new ivory too; no old buried stuff from some back-jungle chief's hoard."

District commissioners of East Africa are lords paramount over territories as large as many an American State and control the destinies of several hundred scattered white men and a few million blacks. They represent the might and majesty of empire. But the D.C. took the thrust at official routine functioning meekly. His half mutterings were defensive.

"Huge district—not very accessible outpost—some confusion since Patterson's death. And the new game warden was—"

King's incisive interruption shocked him out of his excuses for the unwieldiness of imperial administration.

"And what did Patterson die of? What did your office record say about that? Dysentery, they wrote it down, I suppose. And I'll bet they commented in a neat, round hand, 'inaccessibility to competent medical attention', and 'much to be regretted,' et cetera and what not."

King shoved his hands deep into his breeches pockets and stood wide-legged, frowning moodily into the far heat haze. His voice darkened with his face.

"Well, maybe it was. Dysentery is easy enough to get, God knows. Only that Patterson knew as much about dysentery as most of the medicos around here; knew it at first hand, like I do. And in the 'confusion' after his dying, two tons of ivory went out of here."

"Good God!" The D.C. stared at him, wide-eyed. "What frightful thing are you hinting at, Kingi Bwana? What do you know about Patterson's death? If any crime has been covered up you must—"

King flared out at him.

"Aa-ah! I'm not one of your damned policemen. None of all this is any of my business. I'm not even one of your people. Just a 'bally Yankee safari conductor', as more than one of your snooty colonists has tried to rub it in on me. I don't know a durn thing about it. I've never seen any of the crowd running this racket; they're too smart. I know only what you white rulers of the land laugh at—native talk, gossip around my camp-fires, chatter that comes to me just because I'm not one of you, because I don't high-hat my men. I've shown you what's going on. Now sic your new game-warden onto it."

The D.C.'s face clouded to match King's.

"Ah, the new game-warden—Young Ponsonby." He shook his head helplessly. "I wasn't at all keen on his appointment. But his people are very influential at home. A younger son, you know, something of a scapegrace. So they shipped him out; and—I'm afraid he has never known what a real job means."

He shook his head again over the difficulties and entanglements of official expediency.

"Well—" King had no trace of sympathy with anything official—"that's your hard luck—and his. Or maybe it's all yours. Anyway, he isn't camping out along the lone water-holes, running his chance of getting 'dysentery'. He's playing polo at his headquarters station and dancing attendance on your civil surgeon's newly imported flapper niece. Aa-ah, blaa! What's the use?"

King blew his indignation from him windily through his high-bridged nose. Then he shrugged and grinned.

"That's more native gossip. You don't have to believe any of it. It's none of my affair. But I've shown you this much; and it's up to you to halloo your young scion of Milord Whoozis on to attending to the job his influential folks sent him out for. And you can tell him, as my best tip-off, that he's up against one wise and tough hombre that's the leader of this crowd. You don't know it yet, Commish Bwana, but I'm telling you, gang methods have arrived in your colony. This is a crowd that's out to scoop the cream of its filthy racket, and it's not only defenseless game they'll shoot on sight."

"Good Lord, Kingi Bwana, you talk in the most casual manner of the most desperate things! Why, if anything were to happen to young Ponsonby, relatives would rise upon their hind legs in the House of Lords and would demand an investigation into the whole process of government in this colony."

King remained callously unimpressed. For things to happen to foolish white men was their fate in Africa. Other white men would replace them.

"Probably be a good thing for us common herd in the colony if something would happen to him. Maybe you could put in a warden who'd protect the game. You'll need a man who knows the country, who's as clever as a leopard, and who has half the nerve in all Africa to buck this crowd."

The district commissioner took King by the arm.

"Kingi Bwana," he told him with rueful conviction, "you are a masterless man and a blasphemer of sacrosanct things. You talk to me in a way that some of my subordinates would give a month's pay to hear. Take me back to camp, and keep on talking. I need some help. But easy with your mechanical robot legs; my knees are still limp from watching that terrific brute charge down on us."

King fell into a long stride that doubled the commissioner's labored ones through the stiff bunch grass.

"Sure, I'll help you. I'll tell you all I know. Two tons of ivory the Banyan trader smuggled out in his last load. At a pound sterling per pound, London market, that stacks up into money enough to attract some brains into the racket. There's plenty of your ex-soldier land-bounty settlers who have brains and don't figure to ever make that money out of honest farming in their lifetimes. And maybe your office clerks have notes on some of them who they think won't stick at anything. Sort 'em over. Stick your shiny new game-warden on to sleuthing them down."

"I'll need more help than that, Kingi."

"I can give you some more, at that. From camp-fire gossip I figure there's some half-dozen of them in the game; and from tracks that I've seen I can tell you that this particular guy who's shooting around here treads his right foot pigeon-toed. But you don't have to worry about him. No man can go fooling around elephants with a bottle on his hip. An elephant will get him all right. No guessing about that. You don't have to worry about any of them; they're just shooters—maybe man-killers too, if they're interfered with. But you must concentrate on the big shot who's organized them. He's the man to get before your warden gets 'dysentery'."

The D.C. stared at King as at a man who speaks of horrific things without turning a hair. Which, as a matter of fact was exactly so. Like all white hunters, the griefs of government officials were no affair of King's; they drew fat salaries to compensate them against the hazards of pioneer living that the lone hunter man had to accept as a part of the mere matter of keeping alive.

"You talk casually, my Kingi, of apprehending miscreants whom it would be dangerous to approach and against whom it would be extremely difficult to prove anything."

"You make it difficult," King snorted in his disgust. "You minions of the law and order want proof that'll stand in one of your courts. Baloney! These guys are rustlers pure and simple. You've got to send your man out to round 'em up and treat 'em like rustlers."

The D.C. walked half a mile in silence. Then he said:

"Kingi Bwana, you've told me the kind of man I need for this job. I know just one such man. I appoint you chief game-warden of this district with all the salary and emoluments that go with the position."

KING stopped dead in his long stride.

"Me?" he crowed his derision. "You want me to shove my face into this gang racket? And write reports and keep mileage records and fill two pages of your office file with a long story every time somebody takes a shot at me? No sir-ree! Not me! I'm a free man. I'm contracted to you for another two weeks, and then I'm my own boss, and I don't have to write letters to anybody's office clerks and have 'em write back and ask why I didn't mention how come I fired away twenty-three cartridges 'stead of my allowance of twenty."

King spread his shoulders and breathed deeply, crinkling his nose to the sultry air.

"Nossir, Mister Commissioner. You can't appoint me any bloated government plutocrat with a dinky office in Malende. I'm a conductor of safari. 'To conduct Mr. G. Williamson and—or—his party,' my contract reads... 'to lead him to hunting grounds as detailed in permit... to protect him at all times from danger contingent to, or arising in connection with, sport,'... and so on and so on. I know your government contract form for white hunters by heart, if you don't. It's hard and tough enough on hunters; but you can't buy me into government servitude."

The D.C. trudged another quarter-mile, immersed in thought. Then:

"Two more weeks is it?" He smiled wickedly. "During which you must conduct me wherever I want to go; and, 'should client be unable, for any reason, to conclude the term of his contract, balance of term must be paid, as agreed; but the hunter shall hold himself at the disposal of client'—or words to that effect, You see, my insurgent Kingi, I happen to have read some of our official forms. Therefore—" the smile became diabolic—"you will conduct me to my headquarters and leave me there. You will then repair to Malende and take the new game-warden out in my place. And you will exert every care to protect him, etc. etc."

All the cocksure independence vanished from King's demeanor. He looked almost frightened.

"Aw now, Commish Bwana," he pleaded. "I don't want to sheep-herd this milk-and-white dude of yours around the thorn scrub. Why, gosh durn it, he hasn't even had time to get sunburned yet; and, from what I hear, he's steadier holding a tea cup than a rifle, and his blood is so blue there can't be any room left for red."

The D.C. was inexorable—and serious.

"You, my Kingi, are a masterless man who will never understand, nor appreciate, the needs—nor duties of colonial administration. The youngster must be broken in."

"But I'm telling you, Commish, this is a mighty unhealthy district for game-wardens during the next couple months. You'll be sending your son of your best old families to get well slaughtered."

"You, my Kingi, will exercise every precaution to protect him at all times, et cetera, et cetera, as your contract reads—and to the best of your ability too. I think it says."

"The hell with the needs of your colonial government," growled King. "You're out to get me murdered, keeping my contract."

"Yes, Kingi Bwana. My office is full of complaints against you from angry officials who clamor that you flout all constituted authority. But you keep your agreements. Two weeks with you will be very good for young Ponsonby. I shall write him a confidential order by runner."

MALENDE, therefore, saw a disgruntled Kingi Bwana and his

wizened little Hottentot servant looking for Ponsonby while the

compact safari camp waited in charge of the great Masai a mile or

so outside of the settlement.

Ponsonby, if not in his quarters, would likely be in the club. It has been said that where as many as three Englishmen are there will be a club. In these outlying district stations in East Africa, which have perhaps not more than half a dozen official residents, but are nevertheless centers of a far-flung white settler population, there is always a club; a frame building consisting at least of a billiard room, a mixed bridge room and maybe one or two others, but principally of a wide veranda in which cold fizzy drinks can be served to tired white men in long cane chairs.

Ponsonby was there, a tall young man, impeccable in a tussore silk suit. He had a petulantly aristocratic face; not weak, but distinctly spoiled. King, dressed in a faded khaki shooting coat and shorts, efficient bush clothing, eyed him with distaste.

But Ponsonby was traditionally hospitable.

"Oh, Mister King, is it? What will you drink? I've been expecting you. The D.C. wrote me."

With a certain resentment he took a letter from his breast pocket and handed it to King. Couched in the farcial formality of colonial officialdom, it "had the honour to inform him" that he would consider himself under the orders of Mister King until further notice; and it "remained his obedient servant," the district commissioner.

King's thin grin came out. Good old D.C., making things easy that way. And, in a time of stress it seemed that he was not so afraid of influential relatives.

But King slowly tore the letter into little pieces and dropped them into an empty glass. He looked very steadily at Ponsonby.

"I don't work that way," he told him. "I don't like to take orders from any man; and I don't expect anybody else to like them. If a man can't work with me I'd just as soon not have him along."

Ponsonby's angry eyes lifted over his glass rim in a dawning surprise. This, coming from this hard-looking man, required time to assimilate. Embarrassed by a national incoherence under emotion, he mumbled vague sounds that resolved themselves into. "Umm, er, awf'ly decent. Ah—have a drink, what? And sit."

But King drove uncompromisingly to the point for which he had come.

"How soon d'you figure you could be ready to start?"

"Well, er—I was hoping to play against the Planters next week; but—"

"Yeh, I guessed somp'n like that. But how soon would you figure on getting down to your job?"

"Why, er—" Ponsonby's pink-and-white English complexion, untouched as yet by African sun, flushed. His petulant mouth bit down on his speech. "Damnitall, since you put it that way, I'd say any time you're ready."

King shook his head.

"I'm ready now. But I'll say tomorrow at dawn for you."

He was not making it any too easy. But he explained: "The D.C. tells me you'll be needing to cover as much ground as you can. So I've cut out porters and I'm figuring to travel by light truck. Cramped, but we can make it all right in this dry season, and I'll he able to show you at least a couple of the water-holes in two weeks' time. After that, if you're going to tackle the job, you'll have just six weeks to work.

"If you want to throw in with me you'll need your oldest clothes; and I'll have no room for an extra camp boy. You'll find mine more efficient in the bush anyhow. We'll not be picnicking."

White men in Africa become accustomed to their own servants. Some—the more sartorially inclined—grow to be quite helpless without the dark familiar spirit to whom they relegate their intimate personal needs, down even to the matter of pulling off their boots and stockings and finding their toothbrushes. And in the confusion of a safari camp—Good Lord!

It was unfortunate that at this strained moment another white man lurched up the shallow veranda steps. A broadly built, untidy looking man, scrubby-chinned; the very antithesis of Ponsonby's perfection. A hardy type of outlying settler. Dust, and a pistol strapped to his belt, showed that he had just come in from the bush, and his brusque shoving past King was evidence that the road had been long and conducive of liquid stimulant.

A rough and uncouth denizen for a club that sheltered a Ponsonby. But in little district clubs where white men are few membership rules must of necessity be broad. Ponsonby had a hot answer ready for King. But his British trait of keeping his personal affairs strictly personal choked it down to a short, "How do," to the stranger.

But the settler man seemed to have an alcoholic chip on his shoulder. Ponsonby's cool dressiness, in contrast with his own dusty workaday costume, aroused a latent class resentment. He stared red-eyed at the young man.

"Ho!" he said, and there was a nasty edge of insinuation in his Cockney twang. "The nice new gaime-warden a-settin' cushy to 'is tea with nothin' ter do."

Ponsonby remained seated, aristocratically calm.

"Attending strictly to my own business, thank you."

"Ow indeed. It's many o' the likes o' us would wish we 'ad such a heasy business."

The man's rudeness was quite uncalled for. But King could understand the antagonism of a hard-working planter, or whatever the man might be, to the easy security of an official. He stood impartially aside. This was none of his business; and it was an unexpected opportunity to observe how this foppish young man would react to insult.

Kaffa, the little Hottentot, who had been squatting, blanket-swathed in the broiling sun, stood, up and began to scratch himself with the sudden vehemence of an infested ape—with quite unnecessary vehemence. King knew that the cunning monkey's eyes missed nothing and he knew his habits well enough to understand that the little man wanted to attract attention to himself. He moved to the veranda rail to watch him.

The Hottentot postured and scratched grotesquely. Always down toward his right foot. His bright round eyes, instead of watching his own activities, flitted to his master's and then to the belligerent stranger.

King under lowered lids looked the man over. And then he got what he had missed in his absorption in the argument.

The man's right foot turned pigeon-toed.

King's eyelids flickered and went narrow. That track that he had seen around by the water-holes where the elephants drank had been pigeon-toed. Nothing very unusual in that; but that, too, had been the right foot. Still nothing very unusual. Any man who knew tracks knew that many people had that idiosyncrasy in one foot or the other.

Nothing very definite to go on—not by any means "evidence" of anything at all. But—

King watched the man. He still remained aloof. Coldly aloof. He was no nursemaid of pink-cheeked officials—not yet. The man was rough and powerfully built—maybe dangerous. If he should perhaps beat this game-warden so that he might not be able to travel with tomorrow's dawn it was still none of King's affair—might save him a great deal of bother.

But all his faculties were focused on the man, on his every action. Alcoholically quarrelsome—that would fit in with the unknown hunter. Unprovokedly belligerent against a youngster who, far from giving offense, had merely been polite—could it be for no other reason than that this was a game-warden, as had been Patterson, who died of—whatever it was?

So absorbed was King that he did not hear what the man said. But Ponsonby was slowly getting up. With nice care he set his glass down. Half turned from the man, he said in a politely conversational tone:

"You wouldn't want to repeat that, would you?"

Instantly the man did. A foolish word of little meaning; but one which the convention of the English public schools has ruled to be a fighting word.

Ponsonby walked up to the man, quite slowly, buttoned the lowest button of his silk jacket, and hit him squarely over the mouth.

Inexpertly, but with the well-bred heartiness of one going through a necessary ceremony, as much as to say:

"Now, come what may, we must fight."

The blow rocked the man back on his heels; more on account of its surprise than by its force. But it was sufficient to gash his lip.

It brought no ceremonious response from him; no gentlemanly squaring off for formal fisticuffs according to amateur rules. The likes of him had not been brought up in that school. Moreover he was just on the edge of being drunk, and in that condition he seemed to be a man of a demoniac temper.

WITH the first spurt of blood from his lip he screamed an

incoherent noise and tugged at the pistol at his belt. Ponsonby

stood paralyzed at so startling a reversal of everything

proper.

But there was nothing new and unexpected in this sort of thing to King. He jumped like a great tawny cat, reaching for the man's pistol hand. His grip closed on it; and the maniac instantly turned, snarling, upon his interference.

He was burly and thick-muscled. But his own surprise was coming to him. He swung ferocious blows with his free left hand at King. The pistol, shoved high, fired through the veranda ceiling. The man, gibbering rage, pushed in breast to breast and tried to match his strength against King's to force the gun down. King let the man struggle, till, presently finding his opportunity, he dragged the imprisoned arm over his shoulder, slipping his hip under the other's body and heaving him cartwheeling over the low veranda rail. The gun remained in King's hand.

The man fell on his head in the dusty marigold bed that bordered the building front, where he rolled and sprawled ruinously.

Instantly in a gorilloid rush the Hottentot crouched over him.

"Do I slay him, Bwana?"

King shook his head. "We are in the presence of the serkali that rules such things by law; not in the bush."

The man struggled to his feet and wobbled round the angle of the house.

"A man," King commented after him "not hampered by any inhibitions Looks like he fills the bill. But we can't prove a thing on him. Nor he isn't smart enough to be the big shot. Anyway I'm glad I know what he looks like."

He swung round to Ponsonby.

"What," he asked him bluntly, "are you going to do about him?"

Ponsonby faced King as though rebutting in advance an accusation.

"I could turn him over to the sergeant constable for attempted felonious assault with a deadly weapon. But I won't. This is my private affair."

A thin gleam of approval came into King's eyes. Slowly he began to nod.

"Maybe," he ruminated half aloud. "Maybe, dammitall, you have the makin's."

Of which Ponsonby could understand much less than nothing.

"So then," King continued. "Let's get back to what we were talking about. My guess is that you were in half a mind to tell me to go to hell. And to help you make it up I'll tell you that, if my next guess isn't away off, this club member of yours is only a sample of what your job means."

Ponsonby's brows went up in well-bred disgust. To affect nonchalance was his hereditary creed.

"If my blighted relatives insist that I must live in a land where my club fellows are like this, I suppose I shall have to bally well learn to save my life for myself. And really—looking at your methods—I'm sure I couldn't find a better teacher. So let's let it stand for dawn tomorrow—and er—thanks, old man."

"It's funny stuff," said King, "but sometimes it has the makin's."

"What is? What has?" asked Ponsonby, mystified and wholly serious.

"Blue blood," said King. "But you won't understand. Like your chief says, I'll never understand the duties of colonial administration—something mixed up with a holy thing you Britishers have, called the service of empire. But I'll take your drink now, and sit. There's a plenty of more important things for you to understand about this business—like, for instance, keeping alive during your next few weeks. Patterson was a good man; but they got him."

It was a modest little safari that King had arranged for the breaking in of dude Ponsonby. Almost meager—and purposely so. This was no pleasure trip for millionaire sports who bought with their lavish money all the luxury of tent boys and cook boys and personal boys and canned delicacies and a moving-picture man.

King had clients like that too. They came and they got their trophies—or King got them for them—and they went home and told their tales of hardship and danger. Good people; gold mines necessary to the existence of licensed white hunters.

But this was a serious business of finding out whether a man might be fit for the job of protecting the game. King was at no time a nursemaid for incompetents. If his own time and effort must go into the thing, make or break must be the result.

So the outfit consisted of a simple ton-and-a-half truck. Most of the space was devoted to five gallon drums of gasoline and to necessary spare parts and supplies. The big Masai and the Hottentot clung where they could on top of the pile. With them, aloof and very superior, huddled a Nairobi native who rated himself as an auto mechanic and considered therefore that he should do no other work. But the other two knew better than that.

Ponsonby rode on the driver's seat beside King. King, a stubby pipe stuck into the corner of his mouth, maneuvered the car in and out between the spiny mimosa trees and around—or through—the dongas, steep-sided gullies left by the fury of last season's rain. His eyes scouted far ahead and, with a certitude quite incomprehensible to Ponsonby, picked out a route that never caught him in a blind alley of impassable thorn.

With a quick motion of his lips, he shifted his pipe, as if it might have been a cigar, to the other side of his mouth so as to speak to Ponsonby on his left.

"Your chief stuck me with this job because I showed him something. I'm going to show you something worse."

"Yes? What is it?" Ponsonby gasped between spasms of jolting as the truck climbed stiff grass tussocks and slammed down into the dusty hollows.

"You'll see." King bit angrily on his pipe. "We'll set up camp presently and then we'll have to walk a while. That polo outfit your oldest clothes?"

"Oh, quite. That is to say, my oldest sports clothes."

King smiled his anticipation. They left the car in the shade of an acacia grove. The mechanic's function was to act as watchman and to see to it that there would be sufficient dry fire-wood collected by the time the others came back.

The four of them set out on foot. The Masai, magnificently naked, led. Low thorn bush rasped against his legs, leaving dusty white scratches upon their rough hide. Then came King, in pigskin leggings and shorts, his own bare knees as horny as the Masai's. Behind him were Ponsonby and the Hottentot.

Fine dust swirled from the thorn scrub as the men's legs brushed through. It caked with the sweat that drenched their clothes. Down steep gully sides; along sandy bottoms where leopard tracks preceded them for aimless miles; up gravelly banks; more thorn scrub.

King's ears told him of Ponsonby's progress behind him. Not looking back, he remarked:

"Kinder tough on those shiny riding boots, isn't it?"

"Why, yes," Ponsonby panted. "But it's worse on my riding breeches."

"Uh-huh," grunted King. "Figured so."

Not till half a mile further did he look back. Ponsonby's shiny boots were furry with tiny nicks; the closely tailored breeches had shredded clear away; the knees were raw and bleeding.

"Holy gosh!" King surveyed the spectacle. "Hell, I didn't know those valuable things were that fragile. You should have yelped before this."

Ponsonby was grateful to stop. "I—er—well, the rest of you seemed to be getting along all right; and so—er, so I—"

King's grunted commendation was enigmatic to Ponsonby. "The blood comes redder'n I thought." From his frayed shooting-coat pocket he produced a pair of long strips of closely woven cloth. "I've seen this happen before," he said caustically, as expertly he wound them, puttee-wise, round Ponsonby's lacerated knees. "But durned if I've ever seen such frail and fancy pants. This'll slow you up some; but it's not far now."

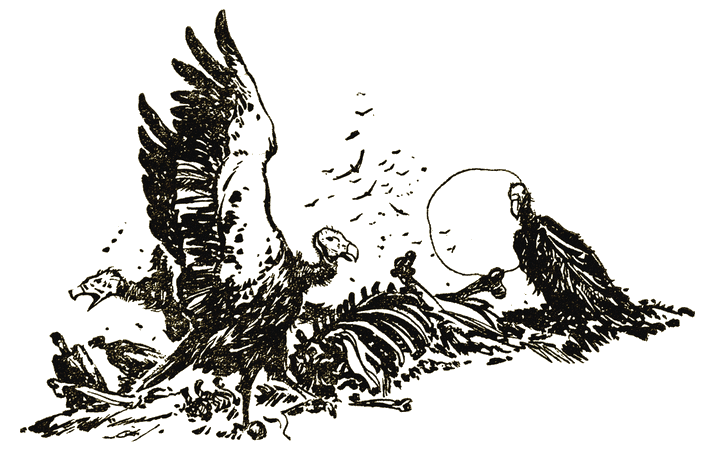

A few minutes brought them to a litter of scattered bones; only the heavier ones intact, the rest—and amazingly thick ones at that—marred and cracked by the tremendous teeth of hyenas.

"ELEPHANT," said King shortly to Ponsonby's stare. "And

worse than what I showed the D.C."

He pointed with his toe to a great flat plate of bone.

"Shoulder blade. D'you notice anything damnable about it?"

"Why, er—I suppose these are bullet holes."

"Yep." King's voice was throaty with anger. "And could you guess what kind of bullets would make a neat row of holes like that all in a line?"

"I should almost say—good God, you don't mean to tell me that was a machine-gun!"

"Right! You're damn right. And that shows you the filthy kind of crowd this is."

"Why, good Lord!" Ponsonby was genuinely shocked. "How foully unsportsmanlike! That's—By Jove, that's as bad as shooting a fox."

King flashed a look at him; but the man was staring in repugnance. King agreed with him dryly:

"Yeh, as bad as shooting a fox in your country. And the way I understand you view-halloo people look at it, that comes pretty near worse than shooting a man. Which it is, 'cause a man can shoot back. You've got the right idea, fella. Damned if I don't believe you've got the makin's."

He scowled moodily at the splintered bone.

"It takes guts and it takes skill to drop an elephant clean with a rifle. One of them, we know, has at least the guts. But the rest of the filthy gang cut loose with artillery. And—" he swung round to look squarely at Ponsonby—"it's a whole game-warden's job to stop 'em."

Ponsonby stared at him, pale and wide-eyed. He sucked in his lower lip and bit on it so that it went white. Then he nodded.

"If you'll help me."

King's grin broke slowly over his face.

"Well, I'm stuck with the chore for two weeks," he agreed. "Come on back to camp and I'll tell you what we're up against. I'm guessing a good deal; but here's how I lay it out."

With unsparing detail as they went along he outlined his theory.

"This gang, the way I figure it, aren't hunters, all but one of 'em. Not even farmers. Town riff-raff that survived the war and took their bonus in land grants—Colonial Empire that your government preached 'em. Well, they came out and went up against drought and locusts and tsetse fly, and they hadn't the experience nor the backbone to pull through."

"Yes. A lot of them came back, soured and sore, and went Red."

"Some of 'em stayed. Back-alley rats; misfits in the big open country. Then the game conservation department down at Nairobi decreed a rest period for this district. Complete prohibition except for certain over-stocked species. A durn good thing. Every decent white man conformed. Till now some smart gent has figured there's a quick clean-up in ivory and hides. He organized a gang, and they've already got some. But the next few weeks will be the cream."

"Why more than any other time?"

King scowled across the heat haze as at a mirage picture that curled his nostrils in disgust.

"The tail-end of the dry season. The smaller water-holes are drying up. Game will be concentrating around those that are left—places like Unduli Pan and Magimagi. Everything—elephants, rhino, antelope, everything there is in Africa all in one place; all thirsty; and, even when they're scared away, all bound to come back. With the first break of the rains, they'll scatter all over the landscape; but until then, the last six weeks, they're like tied hand and foot. That isn't hunting any more; it's murder. These swine aren't hunters. But the war taught 'em how to use a machine-gun. They'll clean the district like a stock-yard. Ivory, horns, hide, anything that has a commercial value."

King's picture was starkly repellent. The prospect of his share of the "duties of colonial administration" opened up more grimly before Ponsonby with each new thing that he learned about it. Still the tradition of his caste to make light of danger was uppermost. He contrived a wry smile.

"By Jove, that reminds me I've never been so dead for a drink. And d'you know, my people pulled strings and sent me out to this job because they said I was doing no good at home, and here would be nothing to do and plenty of sport."

King added the last inexorable detail.

"And there's nothing to stop 'em—except the game-warden."

Ponsonby walked on in silence. "And Kingi Bwana," he amended.

King's answering grin was twisted.

"Yeh—for two weeks. And a sweet chore I'm stuck with. Poor old Patterson is proof that this crowd isn't sticking over anything in their way. And there's a good half-dozen of 'em; maybe more." He strode on, scowling. "There's just one hope we've got. These are town crooks; cunning rats, but they don't know the bush. It'll be bush lore against machine-guns."

Ponsonby's question was a despairing cry for help.

"If you feel the way you do about the game why can't you stay for more than two weeks? The D.C. would pay—"

King's hand suddenly on his shoulder stopped him. The camp was in view, the truck showed through the trees, all quiet and undisturbed. But King was peering at it with alert suspicion. With silent pressure he guided Ponsonby behind a tree.

THE game-warden, with his new sense of the danger that

surrounded his office, tingled to a sense of caution. His voice

dropped to a whisper.

"What is it?"

"Funny," King muttered. "Something queer there."

"What is? I don't see anything."

"Look just to the left of the truck. That tall bird."

"That stork sort of a thing? What is funny about it?"

"That's a greater bustard. The best eating on the plains; but much too wily a bird to be so near the camp if there was anybody around. Camp is plumb deserted."

Ponsonby felt his pulse begin to pound.

"You think— What do you think might be the matter?"

King's deft shrug threw his rifle-sling from his shoulder as the weapon smacked neatly into his hands.

"Durned if I know. But I'm taking no chances in this game. You stay right here."

King's quick look called the great Masai and the Hottentot to follow him.

"We're going look see."

"But my dear chap. I can't hide away like this. This is my business and it's my duty to—"

"Duty be damned," King hissed at him, his eyes never off the distant camp. "You stay right here. My contract calls for me to protect you to the best of my ability and so on and thus next. It's your people made the rules. My reputation as a safari conductor can't afford to take risks."

Yet he was already on his cautious way forward, skirmishing from tree to grass tussock to further thorn shrub, the natives like dark shadows behind him. Abruptly they disappeared from view. Ponsonby was left enormously alone with the hot silence of the empty African veldt. A silence empty of all visible, yet full of things that moved, prowled, slunk, unseen.

Danger? Tragedy? Death? What? A silence that dragged on to slow aeons.

Then the far snap of a pistol shot. Ponsonby's tense nerves twanged like taut wire. He looked for an instant eruption of struggling figures, of more shots. But only the bird leaped convulsively high in the air with a flutter of wide wings. Then King's tall form moved beyond the car; shouts rang out. He saw the flash of the Masai's spear as he moved through a patch of sun.

Then presently a dark form came scurrying back through the bushes—the mechanic. All the forms merged into a group. The mechanic gesticulated excitedly.

When Ponsonby panted up King was tersely questioning the boy. He gibbered and gesticulated with white rolling eyes and outthrust liver-red lips.

"What did this white man look like? What did he say?"

"He was tall. Yet Bwana, not so tall. He was bearded. That is to say, bearded not more than four of five days. He was dressed like—like a white man. He demanded drink. He beat me near to death, Bwana. But I escaped and fled into the bush."

That was the only thing that was definite. A white man had come in a quarrelsome mood and, African-like, the boy had bolted into the bush.

King shrugged his helplessness. "There's Africa for you. Dumb, blind, panicky. Damnation! I wish it had been one of my own men. Kaffa would have outwitted him and Barounggo would have speared him."

"What—who do you think he was? What did he come for—and not stay?"

King barked a short laugh. "This is Africa. No white man's movements are secret. Particularly not yours just now—and mine. Still, if one of them had the nerve to come, why wouldn't he stay to make his play? A friendly visitor would have stayed." His eyes flickered suspiciously into the surrounding bush. "That crowd wouldn't hesitate to bushwhack us."

The Hottentot who had been scurrying around, questing like a dog, yelped his sudden find.

"Ha, Kaffa. Good apeling. What hast thou?" King hurried to him.

The little man was squatting over a patch of ground free of grass. With a skinny finger he pointed. Among the boot tracks in the dust were two within striding distance of each other—and one of them turned pigeon-toed!

King swore softly. On hands and knees he groveled with the Hottentot to find confirmatory trail. He went back to Ponsonby whistling tunelessly through his teeth, his eyes very narrow and hard.

"Trailed." He gave him the cold news. "Trailed from the moment we left Malende." And with grim meaning: "The game-warden is out on the job and the gang is losing no time. Still, what the devil was this play?"

The color ebbed from Ponsonby's heated face, but he said: "Quite complimentary, I'd call so much attention, what?"

"Your friend," King told him. "Pigeon Toe. He demanded drink. That about identifies him—though, damnitall, any man would do that after a hike through the bush."

That suggestion reminded Ponsonby of his own need that the excitement had temporarily driven from him. He reached to the rickety camp table upon which stood a sparklet syphon and a half full bottle of whisky.

"Aa-ah!" The ejaculation rasped from King's throat and he snatched the bottle. "Perhaps that's the answer."

Ponsonby raised his eyebrows. "What is? Dash it all, I never met anybody so full of surprises."

"You'll get your plenty," said King "before you get home—if you ever do. What I just said: to reach for a drink would be the first thing any man would do, coming in from a hike; and he wouldn't stop to investigate much." His own narrow eyes bored cold gray into Ponsonby's wide blue ones. "Maybe that's how Game Warden Patterson got his—dysentery."

"Good God!" This came close enough to home at last to jolt the nonchalance out of Ponsonby. His affectation of languid interest was charged with white-eyed horror. "Good God, you don't mean—"

King nodded slowly.

"Patterson never got whatever it was that he died of by accident. He knew too much about Africa to take chances with impure water or anything like that. I guess that was his whole trouble. He was on the job and he knew too much."

GENERATIONS of tradition ebbed back out of Ponsonby's

past to steady him. He swallowed a few times and licked dry lips;

but his voice, when it came was natural—not drawlingly

humorous, but sober.

"That's a frightful suspicion to have against any man. They may be poaching and all that—beastly unsportsmanlike and so on. But this—Good Lord, this would be murder."

"Maybe, brother, maybe. But I'm taking no chances. I never take chances." King up-ended the bottle and let the liquor gurgle onto the thirsty ground.

"Don't do that!" Ponsonby reached for the bottle; but too late. "Ah, pshaw! Now we'll have no evidence. We may know who the man is—might even identify him with the tracks, with the native boy's identification in a court. But we have no proof of anything on which to convict him."

"Yeah?" King rasped his impatience. "You'd want to drag a man like that into a court, would you? Just like your chief. You people are so bred to law and order that you can't understand you're up against a crowd that'll stop at nothing. You're not safe in your tight little island now. You're in big country; hard country; and let me tell you there's some hard men in the outlying corners of it."

Ponsonby was willing to concede much to this man who seemed to know so exactly what he was about. But his tradition of lawfulness was as difficult to disturb as any other. He mumbled something to that effect.

"Listen." King seated himself on a camp chair and filled his pipe to help him reason patiently with tradition. "This is none of my affair. I'm in it for two weeks, and then there'll be nobody gladder than me to get out in a hurry. But if you want to live you've got to get this straight."

He flipped a grub-box key to the Hottentot and ordered him to bring a fresh bottle of whisky with an unbroken seal and some of the bottled soda that he carried against the contingency of finding a water-hole too befouled by animals for use. He lit his pipe and growled through the smoke.

"Listen. Take this much flat, without argument. Like I told the D.C., gang methods have arrived in your colony. Town rats with machine-guns organized to a racket for some quick money. The only one who seems to know the bush is this Pigeon Toe; for which you be good and mighty thankful."

Ponsonby was all agreement.

"Granted, my dear chap. I believe everything you say. So I must—we must arrest them and—"

"We must?" King blew derisive smoke. "You can't drag me into any official heroics. Listen some more. In my country we used to try to arrest our gangsters and bring them to the law. Our officers were shot down in their scores by gunmen whom they didn't know but knew them by their uniforms—just like this crowd whom we don't know, knows you—and me, durn it. Our gangs had a swell time; they came to pretty near run the country. You Europeans jeered at us about it. But we've learned. We're figuring at last our officers are more valuable than our gangsters, and at last we're giving 'em a free hand to take no chances. So we're getting the gangs. You want to arrest these rats and haul 'em to a law court. O.K., that's maybe your 'duty of colonial administration'. Me, I figure I'm more valuable than an ivory poacher. That's one reason why I'm getting out of this mess when my two weeks are up. So if you want to quit and go home, now that you know what it's all about, that'll release my contract; and nobody gladder."

The exposition of the situation was cold-blooded and

unsparing. King watched Ponsonby shrewdly. Make or break. King's

interest was in a warden competent to guard the game. Either this

youngster would come through or break.

Ponsonby's eyes were hunted. They looked at King—not at the man; at the picture of his words; a hopeless picture of lone-handed inexperience against he could not quite visualize what, but something ruthless. He fingered his rifle nervously. His eyes wandered over the landscape, the vast trackless bush, miles upon miles of thorny shrubs—under any one of which a man's bones might lie and dessicate and never be found. His eyes came back to King. His lip was white under his teeth. His voice dry.

"Perhaps we—we would get something done before your two weeks are up."

King's slow smile crept up behind his eyes and slowly he nodded.

"Perhaps we could," he agreed this time. "If you don't plumb throw away your life on fool chances. And here's something that'll maybe help your conscience."

He pointed with his toe. His eyes that had followed Ponsonby's roving gaze had focused themselves warily on a far point in the bush. Narrow again; and alert as a leopard's, they watched something. His toe pointed to the smudge of moisture where he had emptied the bottle. An insect lay on its back amongst the sparse grass roots at its edge. Specks that were ants remained unwontedly still. Eyes less observant than King's would never have noticed them.

"Would you consider that sound evidence that somebody had been interested in doping the new game-warden's drink?"

Ponsonby stared, white-faced, as what had been suspicion became cold certainty.

"And if a man came skulking around the bush after that, would you consider it lawful evidence that he was the man, come to see how it worked?"

Ponsonby nodded, puzzled. "Any court would consider it highly circumstantial."

"And if he had a gun would you count it a good bet that he had no inhibitions about finishing what he started?" King's hand was stealing round behind his chair to where his rifle leaned.

"Why yes, I certainly—. King, what is this you're driving at?"

King rose softly to his feet and edged behind a tree, his rifle ready.

"Then you better take cover; 'cause there's somebody who fills the bill snooping round back of that tambuki grass belt."

PONSONBY found himself behind a tree—not through

any conscious volition of his own. His pulse pounded in his head.

The stark conditions of his job were piling home on him with a

vengeance. He knew all the desperate emotions of the hunted.

"Have we permission, bwana?" The Masai, lying flat on the ground with the other natives below the bush screen, rolled fierce, eager eyes to his master.

King nodded. The Masai laughed softly and, bending low, ducked into the scrub. In a moment his great form was lost to view. Not a motion of bush tops showed his passage.

The Hottentot threw off his blanket. Beneath it was revealed his extraordinary shape, as naked and as muscular as a chimpanzee, armed with an immense Somali knife. He scuttled off in another direction, spreading out to get the marauder between them.

They were amazing to Ponsonby, these men, pitting their steel and sheer jungle craft against a firearm that lurked cautiously somewhere out in that grass belt.

He stared out at it from behind his tree with a tight prickly feeling of tragedy hanging imminent and inevitable. Whichever way it went, somebody would die. He had never seen violent death before.

The distant grass moved. Cautiously a rifle barrel emerged; then a head and shoulder. Tragedy was unfolding itself before his fascinated gaze. Which of those stalking men would it pick? He wanted to yell a warning.

And then his heart came up into his mouth. The rifle was pointing, not at some unseen thing in the bush, but in his own direction. Good God, at himself!

The primal instinct of self-preservation was older than any tradition of lawful process. He threw up his rifle and fired. Out in the tall grass a khaki-clad arm flung into view. The rifle flew from it. Both disappeared. A thin yellow haze of dust floated up.

Ponsonby's rifle remained at his shoulder, stiff and rigid. He stared out at the slowly settling dust, hypnotized by the suddenness of what he had done.

King's voice broke through the dizziness that buzzed in his head.

"Damned if he hasn't got the good makin's." Like a faraway picture, out of focus, there was King walking toward him.

"You've been learning somewhere or other to shoot off a rifle, feller."

"Why yes, I, er—I've done some—Have I killed him, d'you think?"

King was radiating good will. "If you haven't, the Masai will—unless Kaffa rounds him up first. But I think you've got one dumb bushwhacker out of the gang. Let's go see. But careful; he may be smart enough to play possum; though, by his clumsiness, I doubt it."

They found both the natives squatting over a huddled shape in a faded khaki uniform.

"It is not the crooked-footed one," the Hottentot announced. "But his gun is of the best kind and he had nine cartridges and a hunting-knife, not so good; but some good tobacco, and—"

King cut short the itemized list. "Yeh, I guessed it wouldn't be Pigeon Toe. He'd be too smart to be got so easy. This is some dumb gorilla who didn't know so much about the bush; just mean enough to be a killer. It's our luck the rest are like him. It's Pigeon Toe that's really dangerous; though even he isn't the big shot."

He turned to his two henchmen.

"Take up the trail and read the story of it swiftly before dark." To Ponsonby he said: "If we don't have to up and run for it, we'll let our good mechanic bury this. If we do have to, the hyenas will attend to the evidence of your lawlessness as efficiently as they did to Patterson."

Ponsonby stared at him. He was constantly finding cause to stare at King.

"You wouldn't run away from them?"

"If some half a dozen more like this gunman would be around somewhere? Would I durn well not! I've got no duty of administering your colony. I'm guiding you through the hoops; and I've never had a client killed on me yet."

He led the silent Ponsonby back to the camp. His heart was warming to this youngster whose aristocratic relatives thought he was coming to no good at home.

"Don't pull such a long face about it," he told him. "That was a nice piece of shooting you did there: fast and clean. That leaves one less gunman to get."

Ponsonby reverted to his despairing cry of a while earlier.

"Two weeks is a desperately short time. I'll be lost like a babe in the woods when you go. Dash it all, why can't you carry on if you're so keen about saving the game?"

King was more disposed to explanation of his actions than he had been.

"I told you one reason; I'm not hiring out as a policeman to buck this mob according to your law-book of rules. I'm too plain scared of them."

"Don't spoof." Ponsonby said. "This is serious."

"Well, I am too." King insisted doggedly. "But there's another reason. I'm tied up. Contracted to take Major Devanter of Malende on safari as soon as I'm through with this D.C. deal."

"I might have supposed you jolly well would be," said Ponsonby miserably. "I've heard it said that Kingi Bwana is a valuable man. But I didn't know that this Major Devanter was a sportsman."

In the emphasis upon the title there was a subtle censure of those ex-wartime officers who clung to their rank in civil life.

"He isn't," said King. "He's a rank tyro. But it seems he's wanted to for a long time; and he contracted me early this spring. I'd have preferred to take him some other time; but no other time would suit him."

"Con-demnit! Must he have you? He's an old-timer here. He ought to bally well know you wouldn't let him go round shooting the water-holes at this season."

"Guess perhaps he does know. But he doesn't want to shoot here. He wants to go way out Tadyeni way after sable antelope. A damnfool trip I think; but I can't let him down." King grinned mirthlessly. "It's one of your good governmental regulations that a white hunter breaking contract can have his license revoked and can be 'fined or otherwise disciplined at the discretion of the local administrative officer'. That would be you."

"He might release you." Ponsonby did not sound very hopeful.

"I can't ask him. He's made all his preparations months ahead, fixed his business for a holiday, got his licenses, bought outfit and all. That's the reason for your breach of contract ruling. Maybe you could persuade him—or maybe the D.C."

Ponsonby in turn grinned without mirth. Here was this King man, despite his stout insistence of not letting himself be dragged into an official conflict, actually suggesting possible ways and means.

"I wonder," he said. "Maybe the D.C. could. This beastly thing seems to be of sufficient importance for any decent white man to forego even a long-planned trip."

"Wire the D.C.," King decided quickly. "Send a runner with the message to Lembu. That's the nearest line. If he can't twist the sacred regulations to get around Devanter, you'll just have to bow to 'em humble and buck the racket on your own."

Ponsonby looked at King with the dull hopelessness of one upon whom judgment has been passed and whose hope of reprieve is slight. But he made his voice say:

"Be a jolly little party, I expect, while it lasts."

"That," King nodded sententiously, "is the compensation you must pay for the privilege of belonging in a great empire and having duties to impose the white man's peace upon the empty back bush. The gods of Africa don't make it easy for the white man. But I've managed to last. Keep your nerve, and maybe you will too. But you'll have to have help. You can apply to headquarters to have some constabulary assigned; and by the time the six weeks' slaughter is over the order will maybe go through. I'll have Barounggo round up some men for you—not servants; fighting men. Ha! Here come the two of 'em now. I bet you Kaffa has all the news like it'd been written in a picture book."

THE Hottentot screwed up his face and shut his eyes

tight. In a singing monotone he began to recite the story,

actually as though repeating the pictured word from memory.

"Bwana, there were two men, the crooked foot who came first to the camp and put the muavi root juice into the whisky bottle—"

"What's muavi? How does he know?"

"Sh-sh!" King hushed Ponsonby. "You mustn't break the reel of his moving picture."

"They came, Bwana, in a moto wagon with rubber wheels like Bwana's, but much lighter. Crooked Foot, having put the poison root in the drink, went back to the moto wagon and stood talking with that other one who was a fool. Then that other one took his gun and came back alone, as Bwana knows. But the crooked foot was too wise to come—for this other fool, the mechanic, has admitted that he told him this was the camp of the Bwana Kingi.

"So then the crooked foot, hearing the shot, came a little distance to learn what might be. But he feared to come close. At a little distance he stood in doubt for many minutes, resting his gun on the ground. Then fear overtook him and he went back to the moto wagon, running, and drove away; fast and far; for we followed a ways and came not up with him. That is all the story, Bwana."

"Hmh!" King grunted. "Just about as I figured him. Clever as a devil. But lacking just the guts to be an out and out gunman. We'll take after him in the morning with the car. If we have luck he may lead us to the gang's hangout; and then, with some good spearmen, bush fighters— But that brings us right back to your own crew. What sort of people have you available?"

"Outside of the office staff, who seem to be queer sort of babu blighters, I believe there are some six or seven native walinzi game-keeper johnnies whose real function is to watch out for petty native poaching and who bring in reports. But to tell you the truth, I—" Ponsonby reddened with an embarrassment that he had never known before—"I don't really know an awful lot about the thing."

"Fire them," said King. "I'll get you some fighters."

"But my dear fellow—" This much Ponsonby knew, as did every government employe from the moment of his arrival—"They are government servants, duly approved and appointed under the civil service regulations. They can't be dismissed without proper cause, charges drawn up and substantiated. They can put up a terrific howl; appeal right up to the governor of the colony, and what not."

"Fire 'em," King snapped. "The hell with regulations. Let 'em howl. Get your job done, and point to that while the clerks haggle over red tape."

Ponsonby was inspired to rebellion—he who would not conform to the straitly ruled conventions at home. King's impatience with governmental maneuverings was damningly logical.

"All right, dammit!" he said, "I will. I'll take on your men and let the rest howl at the governor's very gates."

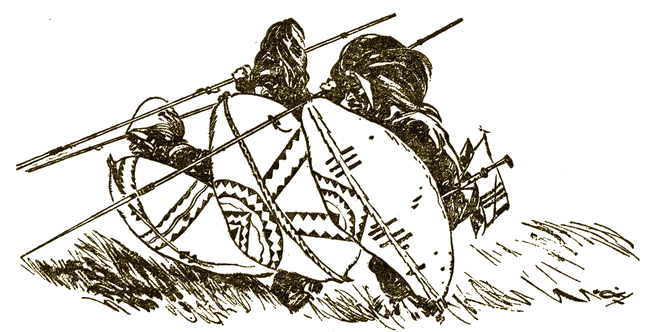

King beamed upon him. An apt pupil. Distinctly a lad with the makin's. "Good for you. I'll have Barounggo pick up some of his own Elmorani, lion slayers." He called the big Masai to him.

"Listen well, Barounggo," he told him. "There is need to exercise thy little wit besides thy brawn. We must select quietly some eight or ten askaris, fighting men who are more than fools; for they must pretend to be walinzi, servants of the serkali, with no loud bragging and shaking of spears. Their pretence I shall judge when I see them. Their valor I leave to thy choosing."

The Masai swelled his great chest. "Bwana," he promised, "Myself I will put them to the test; and they that I shall bring—those who survive—will be warriors."

"Good. Tomorrow, as we travel, circulate amongst the villages."

King found time at last to fish out his pipe and blow luxurious smoke into the still evening air. He cupped his hands behind his head and grinned in review a good day's work well done.

"If we have any real luck tomorrow," he told Ponsonby, "the trail may lead us to the Big Shot who's organized the mob. He's low and smart enough to keep out of the shooting. If we can bring him in as clean as you got that bushwacking thug the rest'll be like running down jackals."

It seemed to Ponsonby that, for a man who consistently refused to embroil himself with this gang, King was taking an extraordinary amount of trouble. But he was learning to understand that this Kingi Bwana of the African bush country was a man quite extraordinarily different from the "set" that he knew. Somehow, he had never altogether admired that set; never whole-heartedly conformed to their narrow, caste-bound conventions. So they, outraged, had shipped him out to the colonies. Things were different in the colonies. Men were different—some of them. White men.

The morrow, however, brought one of the baffling disappointments of Africa. Pigeon Toe's car tracks wound through the tortuous scrub toward open plain country.

"Heading toward Magimagi," said King. "Likely they're operating around that water-hole."

'The plain unrolled itself endlessly westward. In the shimmery distances low clouds of dust hung. King frowned at them.

"Herds of various beasts moving toward the water. Damnation!"

"But we may be lucky," hazarded Ponsonby.

"Not today," King growled, "That's wildebeeste ahead of us. He'll have been smart enough to get ahead of them."

The queer-looking creatures stretched across the whole front, thousands of them, straggled out in an endless panorama of slow motion, feeding as they went. Their grunting barks merged into a dull drumming of sound. King drove his truck among them. The nearest barked hoarsely and stampeded madly for a few hundred yards; then stood and stared in bovine stupidity.

"The luck is theirs that they're just lion fodder," said King. "Worth nothing. Else imagine what a machine-gun would do amongst 'em. And it's they, poor dumb brutes, that save him."

Then Ponsonby understood. The car tracks that they followed came to the edge of the line of march; and there disappeared—trampled hopelessly into the dust by the myriad shuffling hoofs.

King spat in thoughtful disgust.

"Pah! As safe as covering his trail in water. He may be twenty miles ahead of 'em still; or he may have cut out any place and let yet other herds cover him. That man knows his bush. Thank Pete the rest are just killers."

AND that day's disappointment stretched out into the

next, and the next. With the disappearing of that trail all

trails disappeared. All the wild things of the open plain were

closing on the remaining water-holes. Their tracks covered each

other and other tracks covered those.

King made the long trek to the Magimagi slough—circuitous on account of the deep, unbridged dongas that centered there. With the Hottentot he prowled the surrounding terrain, looking for signs of an encampment, listening for shooting. The Hottentot lifted his snub nose and sniffed the air for the faintest odor of lingering smoke. But only animal trails converged upon the pool.

They journeyed to other outlying water-holes. There they found the same peaceful conditions; virgin wilderness unsullied by sound or scent of man.

Ponsonby peered at scatterings of fresh bones.

"D'you think," a gruesome suspicion came to him, "they're using poison?"

King shook his head. "They'd be capable. But these are lion kills. Broken neck is a sure sign."

Three days to Unduli Pan, jungle country, spiny acacias, euphorbias, giant buttress-rooted figs; elephant country.

A wide belt around the pan, where sub-surface moisture lingered, was thick with scrub. Through the tangle, like dark tunnels, animal trails ran. A fringe of dense dead reed and a two hundred yard zone of cracked mud surrounded the slowly receding pool. A perfect open rifle range.

King hid the truck in a far-away bamboo grass and with Ponsonby cautiously sneaked up to the fringe to watch.

With the late afternoon drinking time the beasts came. Zebra first, as usual, impatient, kicking, biting, squealing; impala, leaping amazingly over each other, pretending they were not interested in the water; all the beeste and bok of Africa, cautious, on high-stepping feet, stampeding in wild flurries about nothing.

Later, with approaching dusk, came a general stampede in all directions: and then lithe, tawny forms, barely distinguishable against the baked brown clay.

Later again, with the beginning of darkness, there were vast shapes, incredibly silent, drifting like black shadows out of the shadow, the last of the light gleaming palely from their tusks.

The silence remained. Nothing disturbed them. No shattering fusilade. The African night closed sticky-warm and peaceful. Insects in solid masses drove the watchers from their hideout.

"Aren't we giddy lunatics," Ponsonby wanted to know, "to be going home through this jungle after dusk?"

"A leetle bit too early for lions to be hunting," King told him. "And they'll give plenty of warning, roaring the roof off of the landscape. That's part of their scheme—to scare the meat critters into blind stampede. You'll learn as we go."

And that was about the benefit that came out of their efforts. Ponsonby was learning Africa; learning how to travel, how to camp; to avoid the dangers of veldt and jungle. But to learn anything about the activities of the gang seemed to be impossible. And the anxious days were speeding alarmingly by.

"Durn funny," King growled. "They're hatching something particularly hellish. If we didn't know at first hand that a gun and poison squad was out for our hides, I'd swear this was all peaceful African back bush. The head that's running this is one smart and slimy hombre."

Barounggo, the Masai began to bring in his recruits. Brawny, straight-looking spearmen. King explained to them that great honor was being shown them; they were selected by the serkali, the government, on account of their bravery. The young bwana was the duly appointed lord of all the game in all this wide district, and he had come many days' journey to look for just such men. He invented a solemn ceremony for Ponsonby to accept them into service.

Full of pride and zeal, they scoured a wide range of country, scouted every water-hole, hunting for news of evildoers who slaughtered the game. But they drew only a baffling blank.

"Could it be," Ponsonby hoped wildly, "that they've decided the business doesn't pay after all, and have given it up?"

"It pays all right," growled King. "You saw how much ivory came to just one pool in one night. Elephants often don't drink for three or four days at a stretch when they have far to go. There'll be other herds for that pool alone. Nossir, they're laying low for some reason."

"Perhaps they're afraid of us—you, I mean. And if they're as well informed as you think, they know you are booked up to go away to this Tadyeni place in a few days."

"And they figure then you'll fold up and quit?"

King put the theory in the form of a double question. He pretended to be scowling reflectively into the far heat haze; but from the thin corners of his eyes he was watching.

Ponsonby's face was set. Only the flush of his growing sunburn hid the whiteness that lay below. His jaw muscles swelled as he bit on his teeth and got up to stalk back and forth. Two weeks of the perplexing chase were nearly over; and the picture before him loomed dark and desperately alone. King noted the hard bulges in what was left of his breeches pockets and knew that the fists, thrust deep in, were convulsively balled.

"I—I—" Ponsonby swallowed. "Dash it all!" he cried in a choked voice, "I can't. I can't throw up the sponge and quit. Not now. You've shown me the beastly thing that's going on and—and—Damn it!" He flared petulantly against the merciless exigencies of Fate. "Your blasted gods of Africa do make it awf'ly hard for a man who'd like to think of himself as white!"

King got up and laid his hand on Ponsonby's shoulder. That was all the comfort he had to offer.

"Yes, they're hard gods," he rumbled ruminatively. "But somehow they sometimes stand by the white men who learn their book of rules. The rules are difficult to understand sometimes. But the first one of them is nerve. Stick to your nerve, feller— You've got it. And they may give us a break yet."

He thumped Ponsonby heavily on the back.

"Buck up, youngster. I believe in luck, and you can buy luck from the gods with your nerve. I've pulled out of worse holes. Hell, maybe the D.C. has squared Devanter already. We'll trek and go see."

But luck remained stubbornly aloof. From Lembu, Ponsonby wired to the D.C., a last forlorn hope, to inquire what progress might have been made about obtaining a release from Major Devanter. But after a delay—obviously for a further effort—the reply came.

With a set resignation in his face, Ponsonby handed the yellow paper to King.

"The man is obdurate. I can do no more. Officially I can exert no pressure."

King's hard fist crushed the paper into a tight ball and he flung it into a corner. The major fellow must be a stiff egoist as well as no sportsman. Enforced association with him over a protracted safari into a far and barren district would not be pleasant.

But worse than his own unpleasantness: this Ponsonby; he was a good lad. A ne'er-do-well at home? King snorted. Pah! A no-good, his hidebound old relatives at home might well think him to be; but he was the right material for the big, open, new country. All he required was showing. And he deserved showing—he had all the makin's.

King grunted his disgust:

"Hell, the D.C. might have forced his hand. The durn book of rules set up by your fussy colonial government is harder to understand than the African gods. But, damn, I don't give up yet. If nothing else breaks first, I'll rush this Devanter down to Tadyeni, get him his durned sable, and come back before you know it. You stall around for a while, worry the gang all you can, keep 'em moving; and maybe I'll be back in time to give you a hand with 'em."

Ponsonby was astoundedly overjoyed.

"Really, old man? Would you do that? Why, I thought you wanted nothing to do with this business that you didn't have to. By Jove, that'd be awf'ly decent."

"Aw!" King was embarrassed by the sudden surge of hope and confidence in Ponsonby's face. "As a hunter I do my share in shooting some of the dumb beasts; so I guess it's kinder up to me to do something to give the rest a fair break."

King's willingness to cooperate was sufficient to arouse Ponsonby to a flash of his studied nonchalance.

"Righto, old top. All I'll have to do is stay alive for a few weeks more."

Disgruntled and morose, King trekked back to Malende to present himself before this flamboyant Major whom he already despised for an unsportsmanlike boor.

Boor? Boer, he should rather say. By his accent he placed the man as a South-African and by his name as of old Dutch Africander stock.

MAJOR DEVANTER was a big, broad man, not unhandsome. A

short, fair beard failed to completely hide a steely mouth and

strong chin. Intelligent eyes looked keenly from under straight

brows. A man who knew his mind and had the courage of his own

opinions. He was all cordiality. Like many a colonial of

uncertain social position, he tried to cover his accent with an

affection of Oxford.

"Ha, Mr. King. Awf'ly glad you showed up. I was almost thinkin' I'd have to relinquish you to the commissioner. He was frightfully persistent. Appealed to my sportsmanship and so on. But dash it all, old man, I may be an arrant duffer in the field, but when a fellow's been makin' ready all summer, that's comin' it a bit thick, what?"

King eyed him sourly. "Did he tell you why?"

"Why he wanted you? Oh—er, yes. Yes, of course. He wanted you take young Ponsonby out to—er, sort of show him the ropes. Some trouble or other with poachers, he said."

"And you couldn't see it, I suppose?" said King crisply.

"Of course I couldn't quite see giving up my trip," the major harped upon his defense, "just because a young government man needed breaking in. So I did the next best thing. I popped over to invite him to come along with us. But it seems he was pottering around somewhere. So left him a note."

"Aa-ah!"

There it was at last. The luck that he had been expecting. His grin that had been absent for so long seamed King's face. He thought quickly. This wouldn't be so bad at all. Three white men together, and those quite excellent native spearmen that Barounggo had collected; they ought to be able to make a very successful little campaign against this slimy gang, machine-guns and all. And this Major Devanter. Not such a bad sort after all. He made out a very good case for himself.

"So I think we ought to have quite a decent trip, what?" The major voiced King's own thought. "That is to say if you won't find two of us—tenderfeet, you call us, isn't it?—Two such rank tyros too much of a strain on your patience for such a long trip as Tadyeni."

King's grin vanished. Tadyeni was ten days' journey away from the elephant country.

"Oh! You still want to go to the Tadyeni plain?"

"Positively, my dear fellow. There and nowhere else. I must have giant sable antelope; and you yourself told me that Tadyeni is the only place you know. You see—" the major was confidential—"it's this way. My fiancee's father is curator of mammals in the museum down at Capetown; and I've promised him a habitat group of giant sable. In fact—" the Major laughed a little sheepishly—"the old man's consent is in a way contingent upon my supplyin' him with the specimens. That's why I'm undertakin' a thing of this sort for which I have really no aptitude. Quite out of my line. I'm anything but a hunter. I'm strictly a business man."

"Aa-ah!" The exclamation rasped from King; and that was his only comment. This was not so good. The other, that flash of hope, had been too good to be true. Luck didn't come that easily, not for him. He had always been one of those Fate-bedogged men who had to go out and make his luck.

This time it looked as though Fate were deliberately conspiring against him. Everything was going too perfectly wrong—tied up months ago for just this season by a man who could make no other time; who was willing, it seemed, to go well over half-way to concede a favor to the D.C.; but was bound by very legitimate personal considerations to go to a far outlying place to get certain specimens that could be found nowhere closer.

That was more than just bad luck. That was a deliberate plot of malignant Fate. The sort of thing that stern gods of a hard land sent along to test a man down to the very fiber of him.