RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

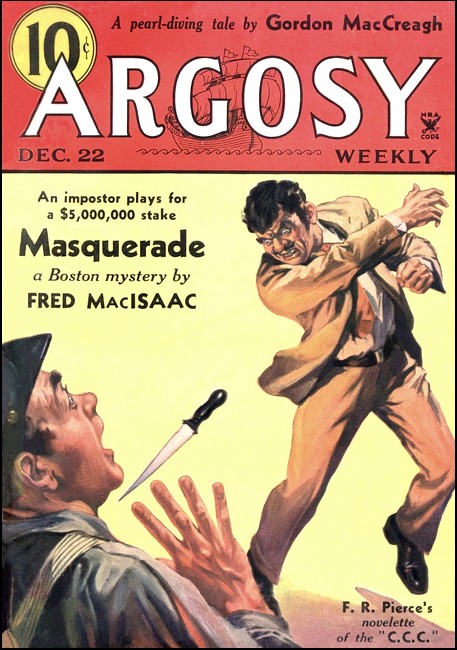

Argosy, 22 December 1934, with "Diver's Chances"

Fourteen fathoms down, Jim Healy fights

treachery to solve a mystery East of Suez.

I'M a peaceful man. I never go around looking for trouble, particularly in foreign ports. But trouble surely has a slinky way of following me around and hitting me in unexpected places. Less than two months ago I was a rich and a respected citizen—and here was I now in Djibouti, of all forgotten sand piles. And in jail.

Two months ago I had all of three thousand dollars in a fistful of pearls and a girl about ready to marry me. Though I don't know about that. Maybe I just thought I was going to marry her. And maybe I'm just as well out of that. Girls and my business don't mix.

Batting around the way I do, picking up deep-sea salvage jobs in one cutthroat Oriental port or another, girls always seem to end up in goodbyes and trouble. A diver ought to steer wide of 'em both.

Like, for instance, this one said she liked me fine; but she couldn't see me ever filling out a full answer to a romantic maiden's prayer. So when Monsieur Raoul Fallon, the hotel-keeper—who must have been snooping around keyholes to know it—thought he should give me the loud ha-ha about it I said ha-ha, too, and I chucked him under the chin to let him see how funny it was. And by the time they threw me out on the side of my face, it seemed I'd used up close on three thousand dollars' worth of pianos and beveled French mirrors. And those French colonial laws, let me tell you, they just have no sense of humor.

Though that wasn't what landed me in jail; they just assessed me for that—on the landlord's own valuation. But when my money was gone, me being an innocent foreigner, they plain railroaded me into this filthy den on account of a perfumed pansy of a corseted Frog nobleman.

Djibouti is a furnace of square, whitewashed ovens built on a foundation of sand in French Somaliland. There are one hundred and twenty-three Frenchmen in it and a few thousand Arabs, Somalis, and what not. The only reason the French don't go away and leave it to burn up in its own blistering sun is that they were smart enough to build a railroad from there into Abyssinia while the British and the Italians, who have grabbed off all the rest of that Red Sea frontage, were arguing about how to divide up that country.

So Djibouti became the rail-head and port And that's how my hard luck took me there. Though I do say it myself, there's more than one salvage contractor in those parts will admit that Jem Healy knows his job. I'm no Frank Crilley, to spend a comfortable afternoon in forty fathom and come up smiling. But I've worked as deep as any of the top-notchers and in more nasty places than most of them.

So here was I in Djibouti on the Rochefoucauld job. She was a Messageries liner that managed somehow to get into the shallows a couple of miles off shore. Quicksand it was; and before they could kedge off the hellish tide in that place took and rolled her.

A crummy piece of seamanship, if you ask me. And a slipshod, higgledy-piggledy job they were making of the salvage. The Dunois Company out of Marseilles was working on her. On her side she lay in bare fourteen fathom. At low tide you could see all of her starboard rail and a black bulge of side, like a dead whale.

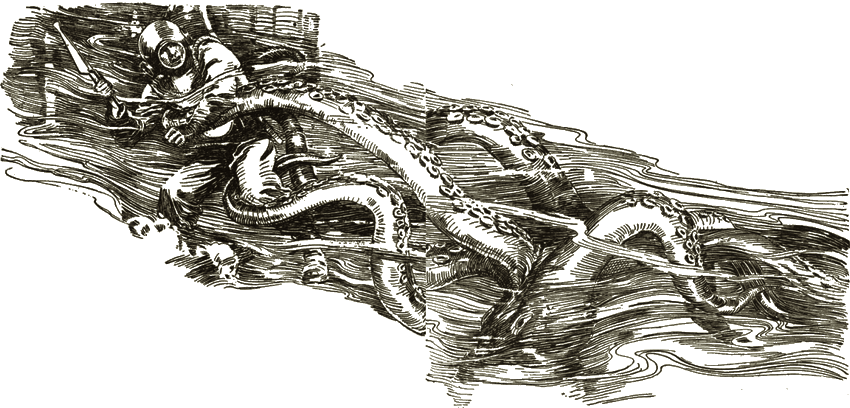

The quicksand, they said, held her fast and they couldn't move her. But my guess was that the real trouble was octopuses. As big as track horses, they scuttled around the lee of smokestacks and deck-houses hoping to fling half a dozen loving arms around anything that came along, and a couple more around a solid stanchion so you couldn't tear them loose.

But that's diver's chances. That's why we get our pay. Through these weren't so bad. It's on the Great Barrier Reef that you meet real he-man octopuses. I'd had my experience of those pretty babies and I had my ideas about handling this situation.

So I was telling Dunois. Not arguing, just friendly like, what I'd do if the contract was mine.

This was the son of the company. Jean Dunois Fils, he called himself. A big bull of a man he was, and young enough not to like criticism. He stuck his arms akimbo and waggled his jowls at me.

"So, Monsieur le Yankee," he said, "you sink you know evairysing about my business?"

I didn't like his tone; but I wasn't looking for trouble. So I told him, without any heat, that I'd never seen a Frog outfit yet that I couldn't teach something about under water.

And from that it went on to an exchange of international compliments, he jumping up and down like a purple monkey, while I wasn't even mad. Even when he called me a red Irish orang-utan I didn't slough him. I just put my open hand over his face and shoved him so he barged across the deck into a pump set-up and smashed a dipsy telephone.

And within the half hour I was ashore with his promise that not one cent of my pay would I get, and there was a law in the land, and I would be sued and fined for damages and for assault and what not.

WELL, I should be worrying if this Dunois didn't like me. I figured that Hazrouk, the Syrian, might be thinking well enough of me to hand me as much as would see me away from this Djibouti hole to the next port.

This Hazrouk is a pearl trader; and I'd happened on a piece of information that a certain Arab had chanced on a bonanza bed; and there he was sitting in his dhow out in the bay, scared sick for fear of hijackers on the one hand, and on the other hand, if he should come in with his haul, of the stiff government tax.

None of it was any of my affair. I don't go looking to shove into other people's trouble. In fact I've found a pearl or two myself sometimes; and I've never paid a tax to anybody's government. So I tipped Hazrouk off; and, he being as smooth as any eel that ever came out of a Beyrout sewer, I figured he'd probably made a profitable deal and would maybe say thank-you with something more solid than a smile.

To get to this Hazrouk is like having a date with a bank president. A brace of hard-eyed Arabs guard the door, and half a dozen more scowl in every passage. From the way they move you know they're stiff with cutlery under their shawls. He himself sits in an arsenal of hardware with three of his relatives; and every one of them jittery enough to be dangerous.

An eel this Hazrouk is, and just now he's spotty gray like a moray and just about as savage.

A moray, maybe you know, is a deep-water eel that runs as thick as a man's leg, with a mouthful of teeth like a python; and it's the only under water thing that thinks a rubber diving suit is good food.

Well, Hazrouk swells his blue gills at me and hisses like I'd done him a harm:

"What talk is this about a business commission? I have trouble and expense enough already with trying to guard this wretched business that you have brought me."

That kind of fazes me for a while. Cause I'm broke right down to bilge plates and, what with Dunois promising to have the law on me, I was counting on some little rake-off on this pearl deal for getaway money. But I haven't come here to start anything—not with four of those pirates all at once. So I just tell him:

"You slimy salamander, if you've snapped at more than you can swallow, why don't you just drop it; and I'll steer the deal to someone who can pretend to act like he's almost a white man."

He just sits and glowers, and the four of them show about five hundred teeth at me. I should have known better. A moray never lets go of anything. And then I have an idea.

"O.K.," I tell him. "If you're so scared of your small-town hijackers, I'll take a job, standing guard. Give me one of these riot guns and I'll sit on your tin-box safe, and it'll take the Somali Coast army to get at your clutch of contraband pearls."

I threw in that hint about contraband just to remind him that he couldn't count on any police protection unless he registered the deal and paid up his tax.

HE sits and glowers at me some more, sizing me up. "I believe you would," he says. "By Petrus, I believe you would. I would pay you—" He hesitates and screws his face like it hurts. "I would pay you three hundred francs a day for night guard."

That's real money, and I ought to have been suspicious. But, "Done," I tell him quick, before he changes his mind.

His spectacled eyes go cunning and, "I have witnesses that you accept," he almost challenges me.

The hell with his witnesses. I'm not backing out.

"Very well," he says. "Done. Your word on it." And then he laughs.

He looks round at his brother bandits, and they laugh too, like a load is off their chests.

"I will now tell you something, my so bold friend," he chuckles. "Why do you think we sit here, armed? On account of some few local Arabs or such? But you are foolish. Who do you think has arrived on the mail steamer but yesterday?"

I don't give a hoot who may have arrived by mail steamer. Till he tells me, his eyes bulging: "No less a person than Jaquernin le Loup! And what business, do you guess, would bring le Loup to this, what you call, small-town place?"

Well, I don't mind telling you that made me jump. This Jaquernin is an Apache of the first grade, leader of the Wolf gang of the Vieux Port waterfront at Marseilles. And they're named dead right They stick at nothing and they spare nothing. Murder of a mere watchman is just an incident on their way to cleaning a whole cargo of silk out of a warehouse. They don't operate on any piking pick-up money.

I can see right away what's in this slick Hazrouk's mind about le Loup's sudden arrival into the picture. And that's where he has me nailed down hard. I don't want any midnight argument with this Jaquernin mob for three hundred francs per soirée; nor for three thousand.

But that's where Hazrouk was so set on his witnesses. You see, in a foreign port like that, with browns and yellows and cross-breeds all ready to climb onto the stranger's neck, a man has just got to keep up his end as a white man. If I'd ever let it get blown about the bazaar that Jem Healy had backed water out of a proposition I'd be having a fight on my hands every day; and, as I tell you, I'm a peaceful man.

THIS Jaquernin set-up has me scared cold; but I've got to carry my bluff. So I tell Hazrouk: "In my country your Jaquernin would rate the boys' brigade. Give me a sawed-off shot-gun and a sackful of shells, and I'll hold your safe down to its moorings. When do I come on?"

My bluff works; for Hazrouk looks at me admiring like and, "I believe you would," be mumbles again. "You are crazy enough. Very well. From ten o'clock then, when the street lights are shut off."

"O.K.," I tell htm, off-hand. "Gimme an advance for a little ice-cream money; and ten o'clock I'll be here."

He looks at me goggle-eyed. "Ice-cream?" he breathes. "In the face of this! The man is altogether crazy."

I suppose it does sound sort of loony—ice-cream for a man of my size who's just been talking tough. But I'm figuring that with money in my pocket I'm going up to the Governor's palace.

Le Chevalier Gérard de Montfaucon de something or other—I could never get the rest of it. But he's a big shot from back home. 'Cause, although there's barely over a hundred white folks in the place, this is a French colony and it ranks plenty important in international politics.

The Governor lives in a big fortress of a place surrounded by a high wall overhanging the sea-front. All this is good for prestige in a riff-raffy port; and it's a comfortable precaution, too, 'cause there's always a chance that these fuzzy-headed Somalis may make up their minds overnight that they don't want to be governed by anybody. So he remains exclusive.

But it's not the Governor I'm aiming to call on with ice cream. There's a girl up there.

She's English; but I've got no prejudices. She talks my language, and she has a job teaching it to the young Chevaliers.

Of course, the way trouble was crowding me just then I'd ought to have had more sense than to go tangling up with a girl, inviting the lightning to strike.

But what the heck, Djibouti is the last tank town on earth, without even a tank, and nothing at all ever happens there.

So I held out for an advance; and Hazrouk made as much fuss about it as though I'd asked for the whole pearl clutch. But with all that loot in his safe be had a durn sight more reason to be scared of a visit from the Jaquernin boys than I had, and I'll bet he didn't know where he could lay his hands on another night.watchman. So he came across, and I swaggered out with as stiff a front as my palpitation would let me.

DJIBOUTI is close enough to the equator to go dark with a bang just around six o'clock. But I could be easy in my mind till ten at least. So I walked along, and maybe I whistled a tune or two, 'cause I didn't hear trouble following on my tracks till it was right up to my heels on a lonesome road.

The first thing I knew was a voice, thin like a knife-cut.

"Monsieur Jem Healy, is it not?"

I whirled; and there was a man, near enough so he could have stabbed me. A tall gent as thin and as straight as a sword. He was dressed all in dark clothes, which was queer, 'cause everybody in Djibouti wears white, and little enough of that.

I couldn't make out much of his face; only his eyes that glittered sort of green and set slantwise like—like a wolf's.

Of course I knew in a second that he could be nobody else but Jaquernin le Loup himself; and it was all I could do to bluster out: "That's right And so what?"

I must have bellowed pretty loud, 'cause he drew back a step.

"Ah," he said. "It is, as I have been informed, that this Monsieur Healy is of a belligerence the most ferocious."

"And so what?" I asked him again, trying to keep up the bluff.

"So much the better," said he. "I have a proposal to make to monsieur, of a small employment."

It didn't take me an hour to guess in what connection he wanted me to throw in with him. But I didn't want any part of this Jaquernin. I knew enough about his tactics to know that he wouldn't think twice about using a man and then dumping him just to keep his mouth shut. The embroidered motto over his bed was, "Dead men tell no tales."

Not that I was giving credit to my sweet Syrian employer for being any amount more moral; but he had none of the wolf ferocity of this Apache gang. So I told him nothing doing, I was already hired on the other side.

"Aa-ah!" he said again, and it sounded like a snake. "There have been those who have opposed le Loup and have regretted it"

Just the way he hissed it out was enough to set the short hairs to crawling up and down a man's back. But I figured that at least he stood alone here, and if trouble was bound to find me I might as well meet it right now before the gang would be together. So I told him as tough as I knew.

"Yeah, is that so? Where I come from our word for le loup is coyote. Beat it hombre. I got a date here."

It's always been a wonder to me how far a bluff will sometimes carry. This Jaquernin le Loup, instead of jumping for me, like I figured he'd have to do on that call, just stood back and snarled his promise that surely would I regret—and it was easy to see why he'd been called the wolf. But he backed away, leaving me with a cold qualm about how mad he'd be when the showdown came, and his mob behind him.

But that wouldn't be for a few hours yet; or maybe a few days, depending on how I got the breaks. So I went on to my date. I skimmed the wall and passed my signals; and presently the girl slid out of the big white house, and I spread myself to be nice and forget my worries for a while.

BUT that surely was my night for trouble to come sneaking up on me. We'd barely been together ten minutes, it seemed to me though it turned out later it was a couple of hours. We were all nice and cozy when suddenly there started a yelping and a hullaballoo up at the house.

Lights went on everywhere. People spewed out of it like ants and ran about just as crazily. Senegalese guards. White men in uniforms. Flash-beams stabbed out into the dark. Everybody yelled and bumped into everybody else. And out of it all I could catch the halloo of, "Thieves! Burglars!"

I might have bet money that trouble would come out of this girl tangle. Just my luck that some sneak thief would choose just this night to grab some of the silver. Of course I should have nipped over the wall and away like anybody but a sap would.

But there was the fool girl, hanging around my neck and whimpering that she'd lose her job if they caught her out philandering. And nobody had to tell me what it meant for a white man —to say nothing of a girl—to be jobless and stranded in a bole like Djibouti.

So I told her to shut off her squealing and duck into the ornamental shrubbery and make for home as best she could; and I went down the wall a ways and started up a racket like I was trying to get over and couldn't make it

That drew them like a hornet's nest Down they swooped on me and buzzed around looking for a soft place to sting. One big Senegal buck made a reach for me. But in those countries, manhandling by a black is something a white man can't allow. So I smeared his nose all over the rest of his face, and be went down howling, and the rest held off.

But then a white officer came, and he had nerve. He rushed in and grabbed hold of my shoulders and shook himself.

"Voleur!", he screamed at me. "Assassin!" You know how excited those Europeans can get.

"Ah, cut it out," I told him. "I'm no burglar, and that's easy enough to prove."

But he was beyond listening to reason. It seems be was responsible for the loot and he had to show his zeal. I might have known he was some high muckaroo, 'cause each time be tried to shake me all his medals jangled, and the perfume he used must have cost all of ten dollars a quart I could smell it on his hands as he pommeled at my chest.

But I'd had a pretty hectic day of it straight along, and I suppose I was a little bit rattled and not so careful about my words as I usually am. So, "Listen, Frog," I told him. "I'm in no mood to joke with you, and I don't tike your smell anyway. Lay off of me or I'll bust your brassiere."

I guess he didn't understand English so well, and he must have misunderstood something. For he went clear raving and he started to pound my face.

WELL. I wasn't looking for trouble. But before all those black Africans, and some of the Arab servants now, there was a limit to what a white man could take.

At that I didn't hit the man. I just slapped him open-handed over his ear, and be fetched up against the wall and skinned the whole side of his face. And then the whole mob jumped me.

I did my best; but I wasn't able to keep my end up for very long. Hell, the whole garrison must have piled on top of me, and they rubbed my nose in the dirt good and plenty. But I guess there's more than one or two of them that carried away a memory of me before they shoved me into the hoosegow—And anyway in all the rumpus the girl got clear.

Well, I've been in French jails before—There was that war we went over to win for them; and after we'd done it I stayed on a while on salvage work, and what with their queer laws and all, and some of their funny arguments about debts, it was more than once that I was on the inside, looking out.

All which doesn't matter here. But let me tell you, their ideas of running a jail are a whole lot less wholesome than ours. No radios in the cells nor ball games of a Saturday afternoon. They think a prison is a place to make a man sorry he's there. And this one in Djibouti had hardly been figured for white men at all.

Of course that whitewashed sand-pile in the desert doesn't rate a full American consul. But we have an Armenian trader by name Koumjian who ranks as vice-consul.

It's three days before they let him see me; the while the police are working on me, trying to third degree me into admitting something, or anything—And there's two of those lads whose faces I'm remembering for another day. It's from them that I learn the sneak thief got away with some of Mrs. Chevalier's diamonds, and they think it's blasphemy when I wish him luck.

After three days of some pretty tough going, Koumjian is let into my dungeon like a merry little ray of darkness.

"I'm afraid. Mister Healy," he offers me of his best "that your release is going to be a very difficult matter."

Hell, I tell him, he knows damn well I'm no burglar; and they can't frame anything on me like that, 'cause they caught me in the grounds and they certainly didn't find any diamonds on me.

But he comes back with the same thing the police have been nagging me with—Why don't I explain how come I was trespassing in the sacred palace grounds?

Of course that has me in a jam. After all the handling I've been through to let that girl get clear I'm not going to give these johnny-darmes the satisfaction of thinking they can twist that story from me.

But that isn't the worst by a long ways, as Koumjian makes clear. We could maybe get over the matter of trespass and they couldn't hold me for very long on nothing better than a suspicion of burglary.

"But," he says with a long face like I'd assaulted a nunnery, "you have struck and grievously wounded the Count Armand, who is an officer of the Governor's staff; and the Latin peoples, my dear Mr. Healy, have not the same light-hearted disregard for authority as have your countrymen."

And he reminds me that not so long ago a party of five Americans on a binge somewhere in Spain punched a policeman, and it took our whole state department five months to get them out of the calaboose.

Five months! And that crowd had friends and influence at home; and their little argument had been with a mere policeman. And here was me with a gold-embroidered count on my conscience!

IT looked like a life term for me; and I did six weeks of it, losing about three pounds a day, which same was gained by the rats and cockroaches. About the only thing that kept me alive was the satisfaction that at least I'd gotten out the tangle with the Wolf mob and I was snug and safe.

Six dingy weeks of it. Till one day who do they let in to see me but Hazrouk, the Syrian. And am I surprised, 'cause I thought that Jaquernin must have wiped him out long ago.

The turnkey locks him into the cell with me, growls: "You have just ten minutes, monsieur," and leaves us.

Hazrouk smiles at me like he might be St. Peter's porter who opens the pearly gates. "My good friend," he tells me, "I have not forgotten you in your adversity, as have all these others, your consul and such. I have been working to get you out of here." He washes his hands in pure banana oil and adds: "In return for which you will do me a small service."

I could have said prayers to the man and I'd do anything for him. But it wouldn't do to let that smooth hombre know I was too anxious. He'd pin me down to raise the S.S. Empress for him with three million in gold on board or something like that

"What service?" I want to know.

He shrugs and spreads his hands, like it's nothing.

"A small job of diving," he says.

If that shiny Easter egg is going to risk a jail delivery, I'm suspicious, and I remind him that I'm not that dumb; any one of the Dunois lads would take time off and do a small job of diving if he'd pay an honest wage.

But he gives me news of the outside world. The Dunois crowd has pulled out. The job is too tough for them, what with the octopuses and the quicksand, and they've all gone home. He'd have arranged to get me out before, but he dassent make a move while there's a diver in sight He puts his fingers over his lips and whispers it.

"The pearls."

Well that begins to sound reasonable. Smart lad, Hazrouk. Of course sinking 'em in a good spot is a whole lot safer than any safe that was ever built. So I'm ready to talk details.

It's easy to understand that where there's half-breed guards and turnkeys a little backsheesh spread in the right place will turn them deaf, dumb and blind.

"But" I tell him. "The superintendent. He's a Frenchman and he takes his job seriously. Morning and evening he walks down the corridor personally and sees that every cell has its occupant."

Hazrouk just grins. Leave all that to him, he tells me. He can't give me details 'cause his time is up and he must go. But by to-morrow I'll be out. I can rely on it I must be out 'cause we have need of haste.

He hammers on the bars, and the turnkey tramps down the passage and unlocks the door to let him out, and I'm left to chew my fingernails and dry bread while I wonder how the devil and whether there'll be any shooting over the walls.

Not that I wasn't ready to take my chance of that 'Cause that jail sure had been a hot anteroom.of hell.

But I might have known that Hazrouk was much too slick an eel to take any risk like that. And a slick, smooth job he made of the getaway. So smooth that I wonder whether he had to hand out any graft even to the turnkey.

HE came in the next evening just before the superintendent's look-over time, and with him another man; white, or pretty nearly so; a big fellow, about my own size.

The whole thing went so fast that it had me gasping.

"Quick," whispered Hazrouk. "You change clothes with him."

That wasn't giving me any time to think, but I figured that if this guy was willing to sit in and serve the rest of my term there must be a whole lot more money in this pearl deal than ever I had guessed; and, moreover, it must be a pretty tough "small job of diving" that was in store for me, 'cause, what the heck, he could have imported a diver for any ordinary work.

But, "Shush-sh," Hazrouk shuts me up. "Quick! Quick! We have need of haste. Only ten minutes."

The big guy makes no bones, but quickly sheds. And I, well, I swap with him. And while we trade, Hazrouk shows how smoothly he reasons.

"The lights in this horrible tunnel are bad at best. The superintendent satisfies himself only that a man is in each cell. As for those others, if they find out anything later, they will keep their mouths shut for their own sakes. Hurry now, hurry."

And it was just as easy as all that. Maybe the turnkey was in on it; I don't know. As for the outer guards, well, I was no personal acquaintance of theirs. It was just a Syrian and a white man going out, pretty much the same couple that had come in.

So I was free; and even the bazaar stinks of the night-festering garbage smelled good; they weren't so much worse than the jail at that.

Hazrouk hurries me to a native house. "We have need of haste," he keeps yammering. "To-morrow night you shall go down. Until to-morrow night you must keep your face hidden, and then we shall be all right"

We, would be all right? Maybe he'd have his pearls all right; but what about after to-morrow night, I wondered. I'd still be in Djibouti, wouldn't I, with plenty chances of their finding out and me being lagged for some terrible term for jail escape? Out of a hundred and twenty-three white men it's not so easy to hide. It sounded like smooth friend Hazrouk hadn't been figuring on any afterwards as far as I was concerned.

"I suppose you've booked a first-class passage on the next mail steamer for my getaway?" I asked him, sarcastic-like.

For just about half a split second that had him scuppered. Just long enough to start a snarl; but he changed it to a quick grin.

"My dear friend," he hurried up to answer me. "I am going to arrange—in fact, I am already arranging for a fast dhow to run you across to the British port of Aden, where who cares what sort of a French count you punched."

That didn't sound like very good lying. But I had to take it. At any rate, I was out; and then it would be up to me to stay out.

"But to-morrow night is easy talking," I told him. "What about outfit overhaul and test. That takes time."

YOU see, I always carry my own outfit. I'll take my chances down under, even at night—Of course I knew all along we wouldn't be able to go at the job wide open in broad daylight—I'd be earning my freedom all right. Diver's chances are plenty enough without adding to them with faulty outfit. So I carry my own. The best that's built; but even the best needs looking after and keeping so. Just one little valve that may gum up is all that's needed to turn a man into fish bait

"It is here," Hazrouk bubbled at me in a frenzy. "In this house. Your own outfit I have secured it. You have all to-night and to-morrow to overhaul it. But no more; we have need of baste."

He was prancing with anxiety; and then he let me in on the hurry. "Jaquernin," he told me like a mouthful of agony. Jaquernin had found out about the cache and had gone to Marseilles to bring back a diver with him. They might be back any day now; maybe on the next steamer. So there was no time to lose.

Jaquernin again. And I'd been hoping I was free of that complication. But I might have known that le Loup wouldn't let go so easy.

I could see Hazrouk's grief. Here he was, with his loot beautifully sunk out of everybody's reach; and there was Jaquernin, hot-footing to beat him to the collection. I had to laugh.

"How'd he ever get onto your slick secret?" I was, interested to know.

Hazrouk bit his yellow teeth together while he hesitated whether to lie about it or not. But, "A man of mine sold out to him," he confessed. And he chomped on this next information like he could still taste it. "But that one is now dead."

Yep, I could well suppose that. If one motto was, "Dead men tell no tales," the other was, "Those who tell tales die." And I supposed further that Hazrouk knew about Jaquernin now because one of the other's men had sold out to him I wondered whether that one was still alive. A swell system of information these bright lads had between them. I'd hate even to be knowing any too much of their secrets.

Well, I could get everything in shape and oiled up in time. But what about a line-tender, I had to know. Hazrouk himself might be all right for attending to my telephone and watching the men on the pump, but he knew nothing about tending line; and, what with working in the dark and all, it would take a good man to keep air-hose and life-line from fouling.

"It is arranged," he assured me. "Everything is arranged. I have Ibn Moussa in waiting on the launch from which we shall operate. You know Moussa. He was with Dunois Fils."

Sure I knew Moussa. A prize winning cutthroat. Dunois had fired him for getting into a knife fight

HAZROUK didn't seem to have missed a bet anywhere. The job seemed to be shaping up workable enough; and I found my outfit all there; nothing missing. So I said, O.K., I'd be ready by to-morrow night; and I asked whereabouts the thing would be and in what depth.

As slick as oil was Hazrouk; but he hadn't got all the answers ready the way he wanted me to know them. He had to make thinking-time while he talked. So, "My friend, I will tell you the whole truth," he said, and he dry-washed his hands and smiled unction at me till he had it straight; and he fired it like a bomb.

"They are in the sunken ship," he said. "In the Rochefoucauld out in the bay."

The Rochefoucauld! So that's where I had to go. Down amongst the octopuses and things that were too tough for the Dunois crowd, working in pairs. And me alone and in the dark! You bet I'd be earning my release.

Though I wasn't backing out. This shrewd egg had whisked me out of that damnation jail, and I knew all along he wasn't doing it for nothing. Only the payment was a meaner job than I'd ever guessed; even though my outfit had all the electric light gadgets on the list

He went on to explain the mystery. "A valuable package like that, you understand, one would not just drop into the water, not knowing what currents or what bottom. Nor would one dare to leave a buoy. So—" He oozed pure oil in his cleverness. "I bribed a Dunois diver to take it down and conceal it for me until this Jaquernin beast should grow tired and go away. And then—" He threw up his hands like a firecracker going up in the air. "The accursed company suddenly withdraws and is gone!"

So then I understood the lay-out, and I was mad. I finished the story for him. "And," I said, "you slimy sea-slug, if they hadn't up and gone you'd have left me to rot in that jail till the rats gnawed the bars through, for all you cared that I'd steered you onto that so valuable package in the first place."

He showed his mouthful of teeth like he was going to bite me, and his nerves were all so jangled up over the close time-call on the deal that he had the gall to almost threaten.

"Your devil's tongue will make more trouble for you, Mister Jem Healy. Remember you are not so far from the jail yet"

But I had outfit to overhaul. I wasn't there to hunt for any argument. So, "Listen, you trepang," I told him. Sitting in that jail is a damsite safer than what you want me to do. But I'm letting no spotted bêche-de-mer go-around and say I'm scared of an underwater job. So I'll carry it through. I'll get you your valuable package. But this time, my beppo, I'm getting enough out of it for getaway money; and the hell with your fast dhow to Aden that you just invented. I'll make my own arrangements."

And at that it stood. He went out, chewing cuss words, and I got to my gear.

HIS plans carried right along without a hitch. I had never a worry about him missing a thing. Along about late afternoon he came with a bullock-cart and stowed my various cases, covering them up with sacks of rice. He was nervous as a cat; but he grinned a sickish gray.

"Ibn Moussa will have them all set up and ready on my launch by nightfall," he said.

"Moussa will keep his filthy paws off of them," I hollered after him. "I set up my own gear. I'm taking chances enough as it is."

But he was gone, and I didn't dare chase after him. Along about dark he was back, and the two of us sneaked out like the sure-'nough burglar I was supposed to be. Hazrouk slunk along the gutter-edges like a muskrat and cursed me 'cause my bulk wouldn't fit into the shadows.

But we reached the waterfront before I knew it—I couldn't smell it in advance because it was high tide. There was a dinghy waiting with a muffled-up pirate in it, and we stole out into the scummy bay.

Just as well that the Rochefoucauld lay two miles out, 'cause even the best oiled pumps make some noise. But two miles was plenty safe.

The pirate rowed with barely a sound. But Hazrouk gibbered at him. "Silence, in the name of Allah! We must be silent! If anybody should find out about this we would be lost! By Sathanas, too many people know already."

There he was; he hadn't got his hands on the loot yet, and he was moaning about how much he'd have to pay for silence.

We reached the launch all right, just a dim, forty-foot shadow on the dark water; and when I climbed on board, damned if that Moussa baboon hadn't unpacked everything and set it up. I was mad enough to nearly swing on him. But a diver who's just about to go down doesn't swing on the line-tender who's his only thin connection with up top.

"The master ordered me," Moussa mumbled. And Hazrouk came between us.

"Yes, of course," he said. "So that everything would be ready. Hurry, now. For the sake of God do not stand there and argue. We have no time to lose."

"Aw, what the devil. We have all night" I told him. "I'm not going to be down half an hour—barring maybe an octopus fight if it's where you say it is."

But damned if the man wasn't more scared than I was, and it wasn't him that was going down. He babbled at me:

"Yes, yes. Exactly where I told you. In the steward's pantry, just off the dining saloon. In the bottom drawer in the corner. A small box I have told you a hundred times. Hurry, now." He pranced up and down, wringing his hands. "If he should find out about this thing! Oh, my God, if he should find out!"

I could see that the Jaquernin mob was on his nerves; and I don't know that I was blaming him. When that smart lad would arrive back from Marseilles with his expensive diver and find he'd been outfoxed he'd surely be one mad wolf.

"Aw, quit dancing," I told him to quiet down. "How's he going to find out any more than that maybe the first story about you planting 'em here was a phony one? How's he going to be sure you ever planted anything? How's he going to find out you ever fished anything up? Unless maybe somebody else sells out on you?"

At that his breath came in a hiss and he jumped back like I'd stabbed at him, and he glared at me. And then I knew what was really eating him.

That snake couldn't trust anybody. Not a one of them in his own gang. And too many knew already, as he'd been yammering. Those mottoes about tales and dead men came to my mind kind of cold. A diver going down is hanging an awful lot on the faith of the men up on deck.

I LEFT him and got to fussing with my gear. And I had to admire. Slick that guy had been. A four-foot screen of canvas had been rigged all along the rail so no lights would show ashore. Not a bet had he missed.

He kept shoving in under my elbow and clamoring for God's sake to hurry, hurry. But I stalled along, fiddling with this and that. I was doing some tall thinking for myself about these mottoes. A length of three-quarter-inch hose line is a mighty shivery connection between fourteen fathom under and a bunch of worry up on deck.

I knew as much, too much, about this deal as any of them. Suppose I'd find some fault with the gear and pretended I couldn't go down, I wondered. I looked around at the deck crew. Pirates all. Seven of 'em. Too many for me. They'd never let me get away with what I knew.

On the other hand, I was necessary; more necessary than any man there—until I'd fished up the loot and put it into Hazrouk's hands And then I'd still be knowing too much, and there'd still be seven of 'em. And two miles of water between there and shore!

I sure was away out on the end of a thin spar.

Hazrouk went pretty near crazy while I let the time slide, pretending to make final adjustments of lamp cables and pump valves and such. I couldn't stall any longer.

But I'd gained something. Tide was dropping and the long curve of the Rochefoucauld rail was heaving up above the greasy swell when I said at last O.K., I was ready to go down; and I hope I didn't look as green as I felt about it

Hazrouk just about shoved me into my suit and I'd like to have bitten his greasy fingers as he tightened up my harness bolts. I hung various tools to my belt-hooks, pry-bar, pliers, a hand-lamp, and so on; and, "Go ahead," I said. "Start up your engine and throw in my dynamo switch."

That was for my big three-thousand-candle flood-lamp that hung at my belly. That was working fine. So I put on my helmet, the new Siebe-Gorman, a quarter turn like a gun breech and a snap-lock. I reached for my own patent octopus-tongs and went down the ladder.

Just clear of the surface I signalled for pumps, and in a second came their soft clack-clack and the swish of air through my escape-valve. Everything O.K. I let go and dropped fast down a descent-line.

And there I was, fourteen fathom below and God knew what hellery brewing on deck.

But I had nothing to bother about—yet. I shoved my chin against the telephone spindle. "O.K." I reported. "On the bottom and all clear. Pay out easy as I go, and tell that baboon to watch out for fouling."

But I didn't expect any fouling of lines. We had cut away wreckage and cordage while I was still on the job and I knew that the way to the main companion was all clear.

My big lamp threw a wide-angle flood ahead of me. Startled fish-eyes suddenly appeared in it and as suddenly flicked away and disappeared. A damn school of killies like a million moths suddenly swarmed into the light and fogged my vision a foot ahead.

But when I reached the steep slant of the ship's deck they whisked off. That meant octopuses; and I was wary. But I didn't have any trouble till I reached the companion. Only a couple of small ones; but I jabbed them with my tongs, and they inked and shot away like tracer-shells.

It was at the companion that a couple of thick arms snaked out of a dark corner and took hold over my shoulder and one leg. A big devil, by the feel of them.

THERE'S people will tell you a lot of crawly-creepies about octopuses. But that's mostly hooey handed down from the old days of skin divers. Of course to a skin they're sure death. Even a little fellow of no more than a four or five-foot span can hold a man. And at that I'm not saying that a real big one can't be hell and damnation, even to a man with modern equipment You've got to keep your head when those devils take hold.

I twisted around so I'd get my light to bear on this fellow; and there he was, snuggled under the companion steps. A brute as big as a mule with the leprosy. I waited for him without moving. You see, if you struggle, they'll shoot out half a dozen sucker cables all at once and maybe pinion a man's arms; and I had to keep mine free to use my tongs.

My own patent. A sort of cross between an orchard pruner's shears and a clam-digger's tongs. So I waited for this baby.

Presently another arm came feeling out and slithered up from my leg. I lifted my arms and let it take hold round my waist good and solid. The thing tugged at me, feeling me out. I didn't move. I just edged my shears forward.

And then the brute stuck out its big parrot head to see what it had gotten hold of. And that's what I was waiting for. I got him dead right. Snipped his leather-pipe neck as clean as a whistle.

The next second everything was blotted out in quarts of solid ink and all arms let go to thresh around. I felt my way out of the mess, on to the main saloon.

Nothing more to worry about—not down there. A big fellow right in the doorway like that is a pretty good indication that there won't be another, for the simple reason that the first isn't likely to let any food get by.

I found my way to the steward's pantry without any trouble—I'd been over that ground before. And sure enough, down in the corner, way back in the pot-chest was a box, just like Hazrouk said.

His voice kept chattering down the telephone: "Is it there? Was my information correct? Have you got it?" I could hardly make him out, he sputtered so in his excitement

"Aw, shut up," I called back." Hold your horses. Give me some time. How fast d'you think a man can move in all this tangle of wreckage?"

I could afford to be snappy. I was as safe as visiting royalty until he had that box. And time was what I wanted.

Whatever else might be going to happen after safe delivery on deck, if I'd ever get out of that jam. I wanted to be sure of some getaway money. And I knew damn well he'd never give me any. So I was going to take out my honest commission in a few pearls before brother Hazrouk got his tentacles onto the loot That's why I'd brought the pry-bar.

Hazrouk kept gibbering down: "Have you found anything? Did the man lie to me? For the name of God, tell me something, won't you?"

I COULD just about see him sweating oily drops as he hopped. I didn't even answer him. I put my pry to work—on the hinge side of the lid. I didn't want to start things with an argument the minute I got on deck. It was no strong-box at any time, just soft wood. The screws pulled out at the first poke.

Inside the box was a canvas bag. I was careful not to cut its draw-string. I took time to haggle out the wet knot And then I had a qualm. My breath choked and my knees quit on me. Like someone had hit me with a section of hose, I sagged down into a pile of broken dishes and stuff on the bulkhead—that being the floor now, of course, on account of the cant of the deck.

That bag didn't contain any clutch of fancy pearls! Nary a one! And that's what knocked me.

Diamonds! That's what it had! Rings! Bracelets! Shimmery necklaces! Some of them in soggy jewel-cases with initials. G. de M. and a coronet! And who is G. de M. with a coronet but the Governor himself!

So then I got it all. The whole smooth story that that sleek Syrian had slipped over on me—and me drinking it in like a baby baa-lamb.

Now I could see it. His panic about being found out. His questions about whether his information had been correct. If he wasn't the cunningest devil I'd ever run into! How sweetly he'd twisted the thing right around!

The more I saw of it, the madder I got at what a monkey he'd made out of me. His pearls, and Jaquernin after them? Hell! Why, damn the slimy toad, Jaquernin had never heard of his pearls—I might have guessed he happened on the scene on mighty short notice. It was Mr. Chevalier's diamonds that had drawn Jaquernin all the way from Marseilles. That's what he was after when I met him up by the palace. And of course he got them. And of course he was the smart head to think of finding a diver to hide them till the fuss should die down.

Though hanged if Hazrouk wasn't smarter, to find out about it. Plenty smart enough to make a goat out of me, hijacking the cache while the Wolf was away.

I jammed my chin again st the phone connection spindle.

"You filthy, slimy, spotted sea hare," I started in to tell him.

"Wha-what's that?" came his spitting snarl " What are you saying?"

Then my wits came back to me. I was in no place to start a fuss.

"Shut up!" I snarled back at him. "I'm talking to a slimy devil of an octopus. I'm in a mess down here."

AND they were both true. I was in plenty of a mess. It was damn sure that I knew too much now. They'd never let me get away with that knowledge. And if I'd have a miracle and did there'd be the Jaquernin mob like bowling werewolves on the trail of the only diver who could have done the job. No alibi for me, whoever else might wriggle clear.

I was thinking faster than my wits had ever worked before. I'd never been in so hellish a hole. But a thought or two buzzed around in the helmet

I tore me a piece of curtain from a saloon port-light and wrapped the diamonds in it. Dynamite, I'd call them, rather than diamonds. Then I filled some broken crockery into the canvas bag and put it back in its box and knocked the lunge screws back into place. Nobody'd know it had been opened. Then I called up the wire:

"O.K., friend Hazrouk. I've got your box."

I could bear him whoop, and a jabber of voices besides.

"Send it up!" he screamed into the phone so it hurt my ears. "Send it right up! Immediately!"

Sure. Send it up. And then where'd I be? Down in fourteen fathom, and him with the box up on deck, and a length of rubber air hose between us.

Of course the answer would be I should bring it up in my own bands. And then my choice was whether I'd be safer down under with my air-hose cut or up on deck with my throat cut.

"How can I send it right up from here?" I growled to my murderer. "Drop a hoist-line over the side, and as soon as I can work my way out to it I'll make fast and call you."

And I'll bet he grinned like a ghoul at that.

I crawled out of there, and I gathered in my slack lines as I went so I'd have some maneuvering room without the line tender suspecting my comings and goings. Out on deck I scuttled along 'way aft to the second-class cabins, and there I found me a safe hidey-hole into which I stuffed the roll of milady's diamonds. I thanked God it was dark, so they couldn't follow my route by my exhaust-bubbles, and the water so murky that they couldn't see the glow of my lamp unless I'd shine it direct upwards, and you can bet I was careful not to.

Then I came back and picked up the hoist-line that was waiting for me. Hazrouk's voice kept coming yawping at me to hurry.

"All right all right," I told him. "Coming. Your damned Moussa has let my lines foul. I'm in a tangle here." I could almost laugh. If he'd only ha' known I was right under him!

Then I went back and picked me a good place on the boat deck and climbed onto it. I tied the box into a bight of the hoist-line and called:

"O.K. All fast! Hoist away!"

Sounds crazy, don't it? Taking a chance like that. But I'd been figuring it all out. The way I sized it up, up on deck there I'd have no chance at all with those pirates. While down below a slim chance remained.

The box was snatched from me so fast the hoist-line near parted. I could hear confused jabbering through my phone. I reached up and shut off my air escape valve. Air began to seep down and swell my rubber suit. If my guessing wasn't all wrong, I'd be needing it

With the hiss of the valve shut off I could hear the vague noises on deck better. I knew when the box reached top, 'cause there was a babble of voices. Then a shout. And then it came. Just what I'd been expecting.

A sudden suck, and the clack of the pumps stopped dead. The phone-wires crackled to a momentary short circuit. My light went out, pop!

And here was I in fourteen fathom with my air-hose and all lines cut!

The slimy, murdering sea serpent!

I SHUT off my intake valve and tried not to go panicky. I still had that other slim chance. I unhooked my breastplate from its knobs. I couldn't reach the back plates; but the front relieved me of forty pounds. My boot weights were the new type. I slipped the lead plates; and that took off another twenty-five apiece.

I had some four or five minutes' worth of air in my rubber suit and if nothing tangled me I guessed I could make it. But let me tell you that's when I had the chills about octopuses lurking behind something in the dark—even baby ones.

Fourteen fathom to climb. Not all of fourteen, 'cause I was already astride of a boat davit and the tide had been going down while I was under, and the port rail was already awash when I came.

My hand flashlight helped; and there was plenty of foot- and hand-holds all along the boat deck. So I made it

I was pretty dizzy and buzzing in my ears by the time my helmet broke through the surface. But just good enough is plenty to be thankful for when a man's racing against Davy Jones.

I twisted my helmet from me and straddled the rail. And there was the dim shadow of the launch purring away into the night not fifty yards distant.

I could afford to laugh. Brother Hazrouk was due for a surprise. For a whole lot of surprises, a couple of which I could promise him myself.

My only worry now was whether daylight would arrive before the tide came back on me. A hell of a finish that would be, after my miracle.

But my luck held. Daylight came and I was still high and dry on the rail. A couple of Arab fishing dhows were in sight, and I hailed them. They came in and then stood off gabbling like I might be a spook out of the deeps and they just that many rock-apes. And damned if they didn't hold off gawping till I was neck deep before I could cuss one of them in to come and take me off.

I MARCHED through the streets of Djibouti wide open. I didn't care who saw me; not so long as I got to brother Hazrouk first.

I busted into his office, and I tell you the man was haggard. The box lay on the table before him and the bagful of broken crockery spilled all over. He sat looking at it in a mottled torpor, like it was he who'd been buried and dug up, not me.

One of his Arab cutthroats was with him, and he jumped up yelping: "Allah, have mercy! It is the spirit of that dead one! Yellah!

Him I smeared up against the wall, just to show him how he lied. But then sink me deep if Hazrouk, goggling and jibbery as he was, didn't have the gall to accuse me. He pointed a shivery finger at me and:

"You—you stole the—my—" he started to chatter.

I leaned across the desk and took him by the ears, and I shook him till his teeth rattled and his head lolled limp like a banker's belly. And when I let up on him for fear his breath would never come back, his tongue thick in his mouth, he still mumbled his fixed ideas.

"Me, you can rob. But Jaquernin! When Jaquernin le Loup comes and finds out what you have done—"

The sheer idiot gall of the man had me so staggered that I didn't mash him. But I cuffed him quiet and I told him:

"Listen, wullygrub. I came here aiming to pull your arms and legs off and leave you hopping like a maggot. But I got a better idea. Sure, Jaquernin is coming. The mail steamer's due today, and from your panic hurry of last night I'm guessing he'll be on it. And sure he'll find out He'll find out every detail You've got no loot to split so your own gang will sell you out.

"So I'm leaving you alive for him! It's all your tea-party and his. As for me, I'm going back to the jail, safe and comfy."

And I did. Wide open. I banged on the door and ordered the pop-eyed guards to lead me to the superintendent. He boggled at me, and I told him:

"Howdy, Mossoo. I've been out for a stroll an' I've come back. Pick me now a nice safe cell with good strong bars, and on an inside corridor. When I'm ready to go out again I'll go."

And here I am now. Sitting close and keeping out of trouble. When the Jaquernin mob has finished with all its throat-cutting and has gone home, I'm going to make me a dicker with the Governor. He'll have to play and it'll be me calling the cards, 'cause nobody but me knows how they lay.

Free pardon and a bonus, and I'll go fish up his diamonds for him. Nothing piking. An honest bonus so I can get me a full new diving outfit and something in the way of compensation for this filthy Frog hole—and maybe I'll insist on an apology from the perfumed officer too.

It's my play and I'm dealing 'em high, wide, and handsome. And, the first thing I'm out of here I'll go take that girl out for ice-cream slam under their noses too.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.