RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Adventure, 10 January 1926, with "He Shall Have Who Best Can Keep"

"PERMIT me, senhor, since you are a stranger in the city of Manaos, to introduce myself. I am Theophilo Da Costa of the upper rivers and I have to offer you—Ha, you know already? Graqas, senhor, you are very complimentary to my name, which I trust, is not unearned.

These ivory nuts, then—I have some three thousand tons of them to offer you and I guarantee the quality to be of the very finest. I know that I might obtain a slightly better price from the German house of Braunschweig; but my friend and partner, the Peloroxo, is a patriotic imbecile, and he insists that the first choice be given to an American export house.

All Manaos City is talking about us? Senhor, all Manaos City has talked about Theophilo Da Costa before; but that the name of that "Red-Head" compatriot of yours should be coupled with mine is a new thing in Amazonas. Yet not entirely to be unexpected of that wild blade, when once he had learned our ways and had ceased to ram down our throats the surpassing superiority of that pothole village of his in some back jungle of the central United States which he used to extol so nauseatingly as his "home town in God's country."

The senhor would like to hear the tale of all that bickering over these nuts? Heh-heh, you Americans are all alike. You would rather hear the exploits of some compatriot of yours than the history of the world's greatest heroes. Well, it is a tale not without worth. How much do you know of the beginning of it?

You know that this Dom Sylvestra came up to Santa Isabel with a chartered steamboat and stole our tagua; and that the Peloroxo then cut the cable with rifle bullets and let the steamer drift on to the sandbank of the Island of Peccaries, and that he sat then on the opposite shore with his rifle and prevented those robbers from working the boat off the sand-bank while I hurried down to Manaos to gather a party of our friends and go up to recapture our property.

You know all that? Well then, to cut short a long telling, I found here three of my friends, stout fellows who might be leaned upon in time of trouble; sufficient—with myself and that Red-Head maniac—to make a very good war against the dozen or so of water front sweepings who were stranded with Dom Sylvestra upon the spit of Peccaries Island. I hired also another flat-bottomed river boat of similar tonnage to the robbers, so that not a nut should escape us for want of space. At two and a half milreis per kilo—which is the price you must pay us, senhor; or the Fire-Head notwithstanding, I go to the German house. Or perhaps even those English people may pay me more, and their money is of the best. At the price of two and a half milreis then, to say nothing of a life or two, one does not squander ivory nuts of the highest grade.

Within two days of my coming I was ready to return; when whom should I meet, careering wildly through the city and shouting my name, but the father of that Peloroxo who had come, as he said, all the way from America of the north to rescue his son from the manifold dangers of our savage up-river country and to take him home to the shelter of his voluminous family.

A portly man he was, getting on into a well-preserved middle age, with a cold gray eye and a line of determination at his mouth corners which showed me where the son got his pig- headedness.

"Miravel," I wondered, "how do you come to know of all this, senhor? For it is but a week since I left that so much imperiled youth crouching coolly behind a tree and enjoying himself sniping at long range at those who tried to carry an anchor out in a dinghy and plant it upstream so that they might kedge the boat off the sand-bank?"

But of this last situation he had known nothing. The family council had sent him post haste, he said, when the son wrote some months before that he had some little trouble with a brace of bravos who thought to trespass upon his territory. This final danger was tie culmination of a frightful condition of life from which the lad must be saved at once. But I told him:

"Have no fear. There is no danger. Your son is sitting in the shelter of the jungle fringe with a rifle of Winchester .45 over his knee. With him are eight naked Indians, blow-gun men bound to him by all the ties of fair treatment backed by the authority of their witch-doctor, who is your son's good friend. When he must sleep, they keep watch. And since the only way that those robbers can escape is to kedge the boat off the sand bank, let your mind rest easy. Twice already before I came away has he shown them that his rifle does not miss. No, there is no danger that they will get away. They will be there when we arrive. Come with us and witness the triumph of your son."

But at that the senhor made a terrible outcry. He would see the intendente; he would call upon the jefe politico; he would invoke the law and the guarda civil and the police; and finally he would go to his consul and demand the protection of the American flag.

Well, senhor, you have been here long enough to know how much power your consul has. Politeness forbade that he should see me smile. But I tried to explain to him.

"Senhor," I said, "at this place, Santa. Isabel, where your son holds down that gang, there has never been a policeman in all the history of Amazonas. The law there is that he who can hold shall have. For the rest, there sits the Peloroxo my friend, and here am I, Theophilo, of the upper rivers. What need have we of a whole platoon of police?"

But that man was as set in his ideas as was the son when he first came. For all that I could tell him, he must needs go to his much-harassed consul and worry that unfortunate still further to invoke a power which his school books had told him reached as far even as our country of Amazonas. Having duly absorbed his disillusionment, and looking very bewildered, he consented at last to come with us and to take his boy out of this horrible environment as soon as he should see him.

Thereupon I could no longer hide my smile. I had no means of knowing how strong might have been the dominion of the family upon that lad before he came away from that home town of his. But this I did know—that a year of our jungles had stiffened to hard iron the character that remained soft metal in the sheltered home life, and that the son whom this all-deciding father sought to drag home had grown into a whole man, well able to make his own decisions.

BUT what use to argue with a man grown old in the narrow views of a little townlet lost in the centre of your great country? We took him along with us. And for me, who like to talk of men and places, he served to beguile the six days of our furious race against the currents of the Rio Negro with his talk of the methods of life and business as conducted in this curious home town of his.

Consider the anomaly: He was first and last a business man, he said. Yet the custom of business in that place was an affair of a family sentiment rather than one of the greatest efficiency. The family owned a factory which manufactured some commodity or other; and into this factory they thrust all the brothers and uncles and sons-in-law of the family to work at a wage no greater than that earned by any outside employee—"to learn the business from the ground up," maintained the man stoutly.

"But, nom diabo," said I, "what happens when a youth of the family proves to be unfitted for that particular business? Or when he can command a better wage in some other business? Will he not change his employ?"

"That," said the senhor, almost with horror, "would be disloyal to the family. In union is strength; and the family will never discharge one of its members nor, if the combined family influence can prevent, will it let one go to another business."

"Mira entas," I marveled, "and with such methods how do you hope to compete in foreign markets with these German houses and English, who select the men most suited to the work in hand that they can find, regardless of family traditions?"

To which, of course, there was no reply except a repetition of the time-worn adage that in union lay strength, which this good senhor translated to mean family union. So the uncles and brothers-in-law and the patriarchs of the family had sat together in solemn conclave and had decided that this wild young scion of theirs had been granted a full year, time enough to have had his fling; and that now he was to come back to his legitimate place in the factory and hold his nose to the grindstone until such time as he, too, should have proven his worth and might be promoted by the solemn conclave to a position of petty partnership, where, if he continued to toil unceasingly, he might some day, when all the others should be dead or retired, rise to a position of management.

"And to this bondage," said I, "you hope to lure that young blade whom we of the upper rivers call Peloroxo, the Fire- Head?"

"Why not?" said the senhor, mystified. "All his relatives are doing the same thing, and he shall have as his share one and three-tenths per cent, of the stock."

Well, what use? How can one show to a man who has cramped his whole life to fit the requirements of a small-town business the freedom which is necessary to a man who has earned his place amongst us of the upper rivers? All that I could say to him was:

"Very well, senhor, in another day we shall reach this sand spit of the Island of Peccaries below Santa Isabel and when we shall have taken your son's cargo away from those robbers you can take him back to your factory—perhaps. And I shall be glad to buy his share of this tagua business that he has built up out of nothing—if the price, in view of the manifest dangers which encompass the business, be not too high."

Whereat he insisted that this was not a business but a competition in banditry, and I could have it for no price at all, so he might only carry his son back to the ordered security of the family factory. Which was satisfactory enough to me. For, as you know yourself, senhor, tagua at two and a half milreis is no business to be sneered at, even if we do have to hold what we have with a rifle occasionally. So I told him:

"Bom. Tomorrow, when we come within rifle range of that stranded steamer, you shall see how hazardous is this business and you shall regulate the price accordingly on behalf of your son—perhaps."

But, maldiça Deus, my confident prophecy turned out to be the most complete failure of my life and a surprise that bereft me of speech as well as of sense.

As we steamed and snorted up below the lower edge of the Island of Peccaries I scanned the opposite shore on the right- hand side with pleasant anticipation, expecting every moment to hear the hail of the Peloroxo and to see him leaping up and down and waving his greeting to our approach. But we drew near and ever nearer, and no signal came to us. I told the pilot to pass between the island and the right-hand shore, on which side I had left my friend with a rifle over his knee. But still there was no sign and I began to feel a certain anxiety. Yet in the next moment I said to myself:

"Pshaw, what a fool thou art, Theophilo! Of course he will not leap up and show himself; for, caralhos, will not those bandits on the boat have been waiting for two weeks for just such a chance to get a shot at him?"

And I called to the pilot, too, to slow down; and to the senhor I advised that he take shelter in his cabin. For abreast of the next little jutting fringe of trees we would draw into full view of the stranded steamer with its dozen of desperate and angry-pirates, and bullets were to be expected— unless indeed the Peloroxo had so tamed them in the interval that they would be ready to submit to our reinforcements.

But the senhor, who had prated so about lawlessness and danger produced the first surprise by calling upon the name of the devil after the manner of your gringos and demanding of God that his soul be condemned to perdition if he would stir a foot. As for me, I had no time to enter into argument with that belligerent caballero. Dientro, did I not know the obstinacy of the son? So I called to my three to take such cover as they might and to be prepared for whatever might befall. But, mil diabos, the surprise was stunning in its sudden completeness. Slowly we drew abreast of the tree fringe. Even more slowly with our nerves all tense and our rifles ready, we forged ahead; and—nothing befell at all. There at the sand spit where we had expected to find our stranded boat with our cargo of ivory nuts and our dozen of ruffians, or at all events such number of them as the Peloroxo had not killed at long range—we found nothing at all.

WHERE we had expected a steamboat and the clamor of men was only the smooth clean sand spit with never a mark of a keel upon it. Beyond was the empty surface of the great river, sinning like a black mirror in the sun. For five miles it stretched into the far heat haze with only the evil snout of an occasional caiman floating like a dead log to mar the clean expanse.

Sanctissimas! That was like a blow in the stomach to me, leaving me with a sick feeling of emptiness as blank as the river itself. I ask you, what was I to do? So taken aback was I that I could think neither of explanation for the phenomenon nor of action to meet the situation. All that I could do was to call upon the names of the saints; and they, of course, helped me no more than they had ever done in the past. To add to my confusion of thought the senhor came running and kept tugging at my sleeve.

"Where?" he kept demanding, "where is this ship with a stolen cargo, and where is my son? Where is this place Santa Isabel where there is to be a fight?"

I cursed him with what breath the blow had left to me. Yet there was a thought in his chatter. Diagonally across the river, at a distance of half a mile and just around a point, was Santa Isabel which was the monthly meeting-place of all the gatherers of castanhas at Santa Isabel at this time. But there was a solitary adobe hut which was the hotel, and the owner and conductor of the hotel resided there permanently with sundry wives and dogs. He would surely have news.

So we slanted hurriedly over to the bare mud bank that was Santa Isabel.

But all the information that fool could give me was as meager as his hotel accommodations. The boat had been there until some two or three days ago, he said—or at least he thought it had been; he had grown weary of walking out to the point to look. The Peloroxo had been on guard somewhere in the jungle fringe of the shore side. Of that he was sure because at intervals he had heard a shot or two. Just how long or until how many days ago he could not say. Nor could he remember when he heard the last of the shots.

Que diabo, his manioc patch needed cultivation, and he had to superintend his wives at work or they would sit in the shade and chatter and would accomplish nothing. What time did he have to go running to see each time that people shot at one another? This was not his war.

The various nut-gatherers, too, who had been present when this war began, seeing that it had settled down to a question of a siege rather than an active battle, had grown tired and had gone about their business. So that there was nobody who knew anything.

That the stranded boat was no longer there was news to him. I could have beaten the fool for his apathy, living as he did within five minutes' walk of the point from where he could command a full view of all that went on. Yet, as he said, what the could he sit on a point of rock all day and watch a long- range duel that was lasting into two weeks when manioc had to be cultivated? Doubtless, he ventured the opinion, one of the brigands on the steamer must have landed a lucky shot and killed the Peloroxo; and then, of course, they would have lost no time in taking out an anchor and kedging off and proceeding down river with the stolen cargo to Manaos. Had we not met them as we came up?

Deus defende. That was an evil thought. But the truth of it could doubtless be ascertained.

"Fool of a fathead," I said to the hotel-keeper. "Send immediately a brace of your wives to hunt the jungle fringe on this shore for half a mile up and down and to bring word of bodies or of bones or of anything they may find."

And on that tedious word we had to wait till those women returned. Dull-witted creatures they were, as all the women of the Baniwa tribes; but they knew enough of their native jungle to make a search along the river bank. In an hour or so they returned and reported that they had found nothing except the places where the white man had cooked his food. No bodies lay in the mold, nor any ant-cleaned bones. So the mystery remained full of anxiety. That one of those waterfront rats should have contrived to hit a jungle man such as the Peloroxo had grown to be was almost unthinkable. And yet—who can tell? An unlucky shot might—

"Name of the ——," I took oath, "if that should prove to have been the case I would hunt those miserable wharf- weevils up and down all the rivers of Amazonas and I would make me a sail for my batelão out of their skins. They would not escape me."

Somewhere farther up the river was that other steamer. Of course we had not met it as we came up. Those men knew well enough that I, Theophilo, of the upper rivers, would be coming up with a reinforcement. So, however they had contrived to get off the sand spit, one thing was very sure; and that was that they would not be attempting to come down river to Manaos. Not yet at all events. Doubtless their plan was to hide up somewhere among the million creeks and islands of the Rio Negro until I should have given up the hunt and then to steal down with their stolen cargo. Fools! As though that would save them from the ultimate vengeance of Theophilo Da Costa!

Yet in the meanwhile— Sangcristu, vengeance did not solve the immediate problem nor answer the immediate question. What had become of the Peloroxo? It was a frenzy that apparently the only means of finding out was either to capture that steamboat or to go on up into the igarape Marauia, the tributary creek three days further up where the Peloroxo had established himself as padrão of a score of back jungle villages which he had trained to gather his tagua. There those eight men who had been with him must surely have returned; and they would have news.

Good then. Both pirates and Indians were farther up river. Yet I must proceed with caution. For just above Santa Isabel the Rio Negro is broken up by hundreds of islands with channels between, any one of which is wide enough and deep enough for the passing of such a steamboat. For the present, then, I could see nothing to do but to go up to the narrowest part of the river before it opens up—which even there, more than a thousand miles from the sea, is a good two miles wide—and there in that narrow spot to anchor in the middle of it so that whatever was above could not pass. Once there, said I to myself, we should have leisure to sit in conference and would doubtless produce between us some plan of action.

SO there we proceeded and dropped our anchor right in the middle of the channel, and at last I was able to draw breath with some satisfaction again. How was I to know of the second instalment of the horrid surprise that fate was weaving for us? So we settled ourselves in reasonable comfort and held a council to decide upon our next action.

That was in the early afternoon that we dropped anchor; and from then on till nightfall I heard more foolish suggestions than could have been evolved by an equal number of legislators. The senhor particularly proved himself to be the very father of his son by telling us how the situation would be handled in his own home town. Truly, it was beginning to be observed that this local patriotism was a disease with all people who live in the central part of the United States. I was anxious to hear what copy-book wisdom would come from the little home state, so instead of laughing at him I told him to expound his creed.

"First of all," he said. "This is not businesslike. You, as men of business, can not spare the time to hunt these robbers. Furthermore, this steamer that you have chartered costs you every day that you keep it whatever it costs. Now, in my home town a business man would find it cheaper to turn this matter over to men whose business it is to hunt robbers. I understand that in Manaos you must pay the agents of the law to enforce law. It would be cheaper for you, then, to pay the police to follow up this matter, and to return to the conduct of your own businesses."

Well, carramba, it had to be admitted that from the point of view of civilized business the man spoke sense. But he was even as his son had been. What that lad had shoved down our throats from the teachings of his home town had always been sense. What he had to learn was that our country of Amazonas was considerably different from his home town. So I explained to the senhor with condescension instead of derision.

"Senhor," I said, "of the three points that you make on the basis of the practise of business men in your home town, three do not fit in these upper rivers. For first of all, as men conducting businesses six days' journey farther than the law reaches, it is our permanent necessity to spare the time at all times to keep what business we have made. Furthermore, the cost of charter of this boat will well and surely be added to what I shall exact from this Dom Sylvestra who has hired these robbers. And lastly, the police, senhor, are men of the cities, while the robbers are hard men of the rivers. I know them all by name, castanha-gatherers mostly, who know the river conditions. They would play a game with the police, and when they were tired of it they would knock them on the head and they would be the richer by so many rifles. No, senhor, the best people to defend our business in the upper rivers is ourselves, and only those who can defend their business can keep it."

Whereat he snorted his disgust and his horror of such business conditions and repeated with conviction that he was more thankful than he could express that he had come to take his son out of them.

But all this talk upon the theories of business advanced us nowhere. Night came upon us before any useful suggestion had been forthcoming. Nor could I blame the others, for I was no wiser than they. Tomorrow, however, was another day, and it must be admitted that we in our country are ever prone to postpone unfinished things to "amanka."

And it was in penalty for that disposition that my great shame came upon me. And yet I have asked myself. How was I to blame? In my own batelão I take pride that no man has ever caught Theophilo Da Costa napping. No matter where I may be or how secure I may consider the situation, I remain continuously on the alert, and when I sleep I see to it that an Indian whom I can rely upon keeps watch. And, had I not so completely despised that bandit gang, I would have done so even here, on my own account, in spite of the fact that it was not my ship.

Yet, meu Mae, how was I to post a watch on that steamer anchored out in the middle of the river channel? I was not in charge of that boat. I had chartered it; and the conduct of it was in the hands of certain mud-witted officers who had had the effrontery already to argue with me about the navigation of fast water in the upper rivers.

But it is my observation that all ship men are alike. Because some person in a bureau of navigation has endowed them with a cap and with a line or two of gold braid, they must know everything, forsooth, about all matters connected with water of whatever nature and boats of whatever build or size. Canastos, I have even known such fellows to hold their opinion against me about what manner of Indians and birds and beasts lived in the jungles which they but saw from the deck of their ship as they passed.

Well, was it not the duty of the officers of the ship to set a watch? And yet—tcha-tcha, I take great shame to myself. For above Santa Isabel is the country of the upper rivers, and I, Theophilo of the upper rivers, should have left no precaution to any man.

But what use? The omission was mine, and I have duly paid my penalty of shame. The night fell, and I with the rest of our little party swung over hammocks from the ship's stanchions across the upper deck and left the disposition of lights and of a watch to the ship's officers, or to the cook or whoever it might be whose duty it is in a steamboat to attend to such things.

Apparently, between the lot of them they did nothing. Anchored in midstream where there was no other navigation they felt as safe as in the hotel in Manaos city. So it seems that the whole ship took holiday and slept and so fell a victim just as easily as might have been expected of those ship men if we four river men had not been on board.

The first intimation that I received of it was a shot in the night, evidently as a signal, and even as I reached for my rifle which hung by its sling from my hammock rope a great weight fell upon me. A half a dozen weights, breaking the hammock rope and bearing me under them to the deck.

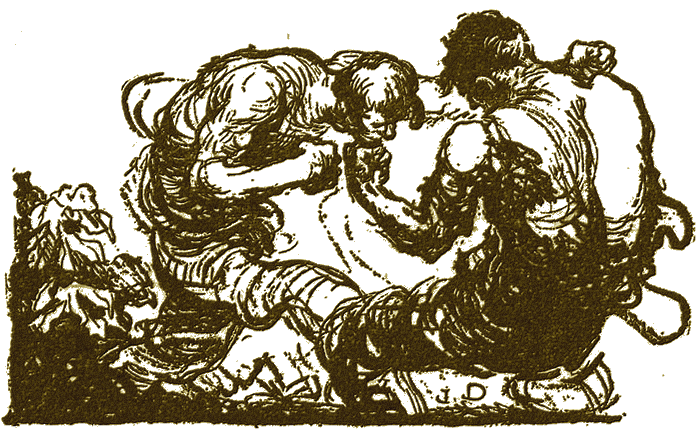

Well, senhor, I am Theophilo. A night attack was no new thing to me; nor am I without a certain experience in rough and ready combat. Two or three or more of the dim forms that clutched at me I hurled from me. Yet, caralhos, I could see by the light of the ship's lanterns that the place where each hammock had hung was marked by a writhing swarm of dark figures which heaved and surged from under, as some creature that is overrun by ants.

I COULD see, too, that these were naked Indians who attacked us; and I fought the more desperately; for let me tell you, senhor, I who have seen and know, it is no pleasant anticipation to be captured by Indians of Amazonas. Sturdy fellows these were, who fought like panthers, making no noise other than the snarling and the hissing of their breaths as they strained in the fight.

Clamor enough there was from various parts of the ship. From the iron deck below came the sound of thumps as hammocks fell, and the ensuing shouts of dismay and quickly smothered calls for help from the ship's crew. From the upper or passenger deck where my friends had slept, while there came no calls for help, there issued from each struggling heap oaths, not triumphant, but hard- pressed, and by their indications it was clear to me that there was little hope of help coming to me.

Everybody on the ship, it seemed, was well taken care of at once. The attackers must have been told off, so many to each man; and, caramba, if one naked savage had swarmed aboard of that ship in the dark there must have been a hundred. And my courage ebbed with my strength as I caught glimpses through the sweating figures that clawed at me of the dim shapes of knows how many dug-out canoes surrounding the ship. Never had I seen an attack so well planned or so swiftly carried out. In the shortest imaginable space of time the sounds of struggle began to quiet down and I knew that the ship's company were all either dead' or bound. Finally my own strength gave out and I could no longer resist the hands that grasped me and the weights that smothered me. I was borne to the floor for the tenth time, and what had never happened to me before was my ignominious fate. I was compelled to give in, to be gasping.

And then I heard a voice giving swift directions. A white man's voice. Of course the thing had been under white man's direction. Indians alone could never have organized so successful a night raid.

"Enough," it cried. "If any man still struggles knock him on the head."

It spoke in the Bahuana dialect, of which I could understand a little. But I knew that voice. A man's naked belly lay across my face. But with desperate effort I contrived to open my mouth and bite deep into the muscle wall. With a yell the man bounded from me; and I lifted my voice and shouted with all my strength.

"Ohe, Peloroxo. Fool of a friend. By the holy shoes, what goat's judgment is this, that you make a night attack upon us? Call off your men before we do them a damage."

Upon my words there fell a sudden silence. Such little struggling as still continued ceased, and even those wild Indians relaxed a little, almost as if they had understood. Then, out of the night, from over the side of the ship, arose a great swearing in English, the name of the Almighty being coupled indiscriminately with that of the Evil One and his abode, after the maimer of you gringos. Then a great laugh and the sound of a man making his way hurriedly to the upper deck. I took advantage of the diversion to throw my captors from me, so that at least I met my friend standing on my own feet. And as he came pushing through the dark masses of swarming Indians, I abused him with thoroughness and indignation, saying that we had been hard put to it to refrain from killing some of his men.

But he believed my subterfuge not at all; and he strode forward and gripped my hand chuckling and taking oath by the name of Saint Mike and by the affection that he bore for Saint Pete that this was the greatest jest of his life; that Theophilo of the upper rivers should have been captured asleep by his own pupil of barely a year. Por Deus, what a tale that would make for the cafés when we should next see Manaos. But I cut him short with coldness and told him—

"Cease your ribald jesting, my overweening friend; for I have here one who will properly discipline you with all the authority of all your whole home town behind him."

Instantly he became grave, almost apprehensive, and:

"Who, then?" he demanded.

"Come," I said, "I will present you." And I led him past several dim piles of men to a farther pile which marked the place where his father's hammock had hung. To the grunting beneath that pile I spoke:

"Senhor Featherstone, here at Santa Isabel I bring to you, according to my promise, your son."

The Indians still sprawled like ants over their game, for they had received no word yet to release their captives, and they made no move without the Peloroxo's direction.

"Father of God!" he exclaimed. "What is this?" And he barked an order to them.

Slowly then the piles disintegrated and men rose from beneath them, all cursing at once. The senhor, though he scarce had breath to speak, murmured first with unabated belligerence:

"I think I put two of them out of business, by golly." And then, instead of embracing his son and kissing him on both cheeks, as was to be expected, he took him only by the hand and pumped it up and down severely while he kept repeating:

"Why, Jim, old boy, how's tricks? 'S good to see you, son. How's things coming, eh?"

And the Peloroxo, great oaf, could do nothing but repeat the same formula. How long this extraordinary form of greeting might have continued I cannot say. But now muffled cries began to arise from the crew from the lower part of the ship, calling to know what all this was about and clamoring to be released.

"Gee," exclaimed the Peloroxo in sudden remembrance, "I must tell my men to—say, I hope we haven't hurt any of them."

"As for me," I said, "I hope most devoutly that they have slain several of them. Bid your men throw them overboard, as also certain officers whom I shall point out to you. Ourselves, we shah conduct this ship and so shall avoid further disaster."

BUT he laughed and shouted to the Indians, and they, too, laughed like children at a great joke and slapped their thighs and laughed yet more as they began to make their way back to their canoes. And the lights were turned up, and presently in the place of Indians the lower deck began to spew up the members of the ship's company, all waving their arms and all jabbering at once. I advanced upon them fiercely.

"Back," I ordered them, "back to your quarters, mud-heads, and stay there till I give leave. Let only the cook and his mocos make speed and serve a small black coffee, and let the clamor cease."

There was some little murmuring and much questioning. But I was in no mood to answer questions or to brook delay. So presently order was restored and, with the first coming of daylight the coffee was served on the upper deck, and we sat down to exchange news. The explanation was simple.

"Amigo Theophilo," said the Red-Head, "we have both made the same mistake. We have neither of us given credit to those robbers for sufficient cleverness. Upon me, as I sat comfortable on my guard there, they turned a good trick. First they made another attempt one night before the rising of the moon to carry their anchor out. But pshaw, that was nothing. I could see the dark blot of their boat against the surface shine of the water, and with a couple of shots I sent it scurrying back to the shelter of the ship. After that, what with my eight Indians watching while I slept, I felt secure.

"But those fellows were nobody's fools. Seeing that they could do nothing so long as I remained on guard, they set about to create a diversion. Some of them under cover of the ship's hull, went across to the farther shore and there organized a war party of the Baniwas, telling them that a small party of Bahuana, my men from up river, were encroaching upon their territory. And one night they came across lower down and advanced up jungle upon us. I don't know how many there were in that war party; but they must have been quite a crowd, and they were cleverly directed. That skirmishing in the dark occasioned more noise than damage.

"But the long and the short of it was that when it was all over three of my men lay somewhere out in the jungle, and I had been kept sufficiently employed to give those bandits a chance to carry their anchor out and drop it well upstream. Which was all that they wanted. For the attack melted away, and when I was able to return to my post on the shore I was in time to see the steamer haul off the sand bank with its winch. And then, while the men remained carefully under cover, I could hear their yells of derision while the boat snorted merrily off under its own steam. So, amigo Theophilo, you must admit that this Dom Sylvestra is a lot cleverer than we gave him credit for." But I said:

"No. That was never the thought of Sylvestra, who is no more than a crafty business man of the city. That would have been Diego of the dog ears, or that arch ruffian, Esteban. River men both, who know this water like the bottom of a drinking cup. They will give us trouble yet. What plan had you in mind, my friend, when you so cunningly attacked us this night?"

"What plan?" he repeated. "Everything is now altered. What could I do when I saw them sail away up river, but go as fast as I could to make preparations for a great war? So I went up to my igarape of Marauia and gathered all the Indians who work for me and every possible canoe and came down to meet you. Only I didn't expect you so soon; and when I saw this steamer of identical size anchored like a refuse barge in midstream I said to myself, 'This can never be Theophilo'—and those pirates give me credit for as little sense as I had to give them. So I came, as you know, and found—ho-ho—I found Theophilo of the upper rivers asleep like a turtle on a mud bank."

But I silenced his ribald laughter by adding to that:

"Almost as though I might have been Theophilo of your home town in the central wilderness of the United States."

He had the effrontery to laugh; and—

"Well," he said, "if I was a hick once, I have given proof that I have grown to be an up-river man in that I have captured Theophilo of the upper rivers in his own water."

But at that the senhor, his father, cut in with a shocked expression as at a blasphemy. It was apparent to me from his manner that this term, "hick," was the most mortal affront that could be applied to those central States.

"Oh, come now," he made remonstrance. "That isn't right. I don't like to hear you speak of your little old home town in that way. You should always remember that you owe all that you are, mentally, physically and morally to the good American upbringing you received there."

Alas for the credit of the associations of youth! The Peloroxo was in no wise abashed. Yet he sought to mollify his father by making concession.

"Good groundwork, Dad; and I wouldn't want to be without it. But it must be admitted, as I found to my cost when I began to meet the rest of the world, that my outlook was a bit, er—provincial."

At that my three friends who had come with me on the rescue party shouted their mirth aloud; for they all remembered, as did I, what an obsession it had been with the lad, when he first came among us, that the only right way to think or to do or to live was the way of his little home town. Whereat he was this time very properly abashed, and covered his confusion by making a con- session to our side.

"As to mentality, let my friends judge. But as to physique it must be admitted, Dad, that I'm a lot stronger and healthier since I've been out in the open river, and it's here that I've learned to stand on my own feet."

Which was true. He had come out, with the makings of a man indeed; but was at best a youth as soft as he was opinionated. Now he stood, sun-browned and as hard of muscle as he was of feature. A whole man of the upper rivers.

The father looked at him with a certain satisfaction which almost overlaid his sense of shock at previous heresy. Yet his very words showed that the satisfaction was that of a builder of business at the prospect of a strong new plank to be built into the structure of the family factory.

"There's nobody gladder than your old dad to see it, son," he said. "But now, before you talk any further of plans for going on a wild goose chase after this last cargo of yours, let me tell you that your partner here has offered to buy out your share of this precarious business; and I think I can assure you that, in view of the experience you have gained, the board of directors back home will agree with me in placing you amongst the officers of our company with a corresponding salary of as much as fifty or sixty dollars a week."

I MUST confess to a feeling of anxiety; for while to my thinking I could conceive of no fate more horrible to an active man who has learned the taste of our river jungles and the ever present expectation of some new thing happening at any moment round the next corner than to be immured in an office of a factory in a subordinate position. While my blood chilled at the very contemplation of such a life, defende me Deus, I knew what a matter of religious faith to these home-towners was that tradition of family unity; and who can tell how an early religious training may hang over the most unexpected of men.

But the Peloroxo was one of those in whom family tradition had not stamped out a still earlier family tradition. His bold spirit had come to him from his father's father and from that father's father, who had been of those hardy pioneers who had built the foundations of that great America of the north. Just such men as we need here in Amazonas to develop the equally great possibilities of this country.

Yet my heart ceased to beat as I saw him hesitate. It was clear that he was swayed between obedience to the call of his father or to the call of his grandfather. But for only a minute. His spirit clung true to the demand for freedom and action that was his heritage. After that his hesitation was only over the manner of his refusal. And the manner of it was, of course, typical of all the disrespect that you gringos show toward your parents. Instead of kissing his father's hand and begging to be forgiven for venturing to hold a different opinion, he said bruskly:

"Gee, Dad, I hate to have you think I'm throwing down the family. But goshalmighty, I'd like to have you put it up to that board of directors to consider what they offer me—a job in the office at fifty a week! While here I'm my own boss in my own business. I'm a free agent in God's good open air and I can knock out, as soon as I get that cargo back and get things going— why I ought to be making an easy five hundred a week in another year or two. And then I'll be able to knock off for a spell and take a run up and jeer at those poor slaves in the factory. Dad, it don't balance at all."

Which was exactly what I had told the senhor. Only I, grown man that I am, would never have dared to speak to my father with so little deference. But I leapt up and slapped the lad on the back and congratulated him before his stand might be shaken by argument.

"Now you are truly emancipated," said I. "A full-fledged river runner. And that point being properly settled, let us without further talk come to a decision about how to get that cargo back, bearing in mind the while whether it might not be cheaper, as the senhor your father suggests, to let the cargo go and to exact such reparation as we may from that gang as later opportunity offers."

But here the Peloroxo was wise in his obstinacy.

"No," he said, "por Deus, amigo, I will never let that cargo go. For one reason, I think we can so manage that it will not be so very expensive; and for another, if we once let those pirates escape with one single nut of ours we will have to spend the next five seasons in teaching all the rest of the river that what we have once gained is ours and that we can hold it."

He was abundantly right, of course. This was a case that all the river was watching, and the lesson of a severe retribution was necessary. So without argument I called upon him to say his plan by which means the cost of that retribution would not be too great.

"Well," he said, "they're somewhere above here, aren't they? So we've got them bottled."

"Bom," I agreed, "but you must remember, my young friend, that this Black Water of ours is considerable of a river. 'Somewhere above here' means navigable water through any of a thousand channels; and when you add to that innumerable tributaries and back creeks into which a shallow draught vessel may penetrate for a hundred miles or more, you will see that there is opportunity for hiding for five years. It was upon that problem that we were engaged when we decided to sleep upon it in the hope of clearer reasoning in the morning."

But this Peloroxo had a faculty for putting his finger on the spot.

"The only problem," he said, "is to keep them from doubling back and escaping."

But I disagreed with him.

"Not so, my sanguine young friend," I pointed out. "With our rifles on this boat anchored in midstream it is true we can hold them. It is barely a mile to either shore, and we shall not be caught asleep again. But that will not bring them into our arms to surrender. There remains the problem of pursuit and of the cost of maintaining this accursed steam barge on guard."

He threw back his head and grinned at me with a wrinkled nose, and I knew that he was pleased to be able to refute me.

"For just that matter, amigo, I have made provision," he chuckled. "Look, I have brought all the men from all the villages of my igarape of Marauia. Four hundred and seventeen strong canoe men and four sub-chiefs. An army worthy of Theophilo himself, no? And to you, my friend, I give credit for my teaching; for it was by your advice that I became the supporter of the chief ipage. Wherefore now in my hour of need I sent him a present of a small bag of salt and laid my case before him; and he immediately proclaimed a big witch-dancing and told the people that the omens were strong and that they should follow me.

"One hundred and thirty-eight big canoes I was able to round up. About thirty belonging in the villages, and the rest those that I have been building for the transportation of my tagua to Santa Isabel. So that we have here both an army and a fleet; and we can proceed up river, combing every channel and nosing into every inlet as we go. How far up or where those pirates may be hiding we can not guess. But this is certain: That they can't slip by us, and sooner or later we must find them." And then—the grin of that shameless young ruffian broke out with renewed malice—"a crew of naked Indians that has captured Theophilo of the upper rivers will surely find no difficulty in capturing a shipload of bandits."

Well, so it is with you gringos. What respect could I expect from one who addressed his own father with slang? I said only to him:

"Picaro, it is well that you have profited by Theophilo's advice. But there still remains, my very clever young friend, the problem of the expense of this steamboat that we have chartered to come to your rescue."

BUT he only grinned the wider. I might have known that he was waiting for just some such chance to entrap me in my speech.

"Nay," said he. "There will be no expense. In fact, there may even be a profit. For would I come down with a hundred and thirty-eight good canoes empty? That would be unworthy of a graduate of my home town business college. Look over the side, now that the daylight has come, and you will see that each canoe carries a full load of tagua. And while I sat below there on guard, were my men idle? Why should they be? I sent my capitão back in my batelão with a crew made up of some of the men folks of the hotel-keeper's wives. Shiftless fellows enough, and poor paddle men; but good enough to reach the Marauia; and two full loads he now in the old rubber shed beside the hotel. Sufficient, with this load, to fill perhaps half this steamer; and the castanheiros have left enough of their Brazil nuts to fill the other half. So what reason is there why we should not send the boat back to Manaos with a full freight?"

Por Diabo, well and truly did that scapegrace heap confusion upon me. Which happily was covered by the sudden acclamation of his father. The senhor leapt from his seat and went, as I thought, to embrace his son. But instead of embracing him, he did no more than shake hands with him and pat him on the back, saying:

"That was well done, son. That was a good business move. Very good. In fact, I doubt if your brothers, with their home training, could have done any better."

The Peloroxo had the grace to turn as red almost as his hair. And I, fearful lest this should lead up once again to the renewal of the attempt to incorporate such promising material into the family factory, made haste to cause a diversion by introducing the discussion of plans for procedure without any further delay.

For the five of us, up river men all, there was no trouble. This little expedition would be a jaunt not so unpleasant with the pleasing prospect of regaining our own and visiting a just retribution upon our robbers. The Peloroxo had a batelão as good as my own, a thirty-foot boat built of stout planks with a palm-thatch roof over the after half and with space for six or eight paddle men in front. In such craft I have spent months of a full rainy season with comfort. Our anxiety was for the senhor. For after all, up river travel is not without its dangers and its hardships, to say nothing of the insect pests which would meet us if the pursuit should continue as far up as Umarituba. The climate, too, was a matter to be considered. For while this was not the rainy season, we were within half a degree of the Equator. So the heat was something not to be forgotten. In the steamboat, well and good; the speed of the boat made breeze enough to render our temperature of a hundred and fifteen degrees pleasant enough. But the slow progress in the cramped quarters of a batelão was something different again. A travel, then, which would be easy enough for an up river man would be no easy experience for a well nurtured man of business from the little town in "God's Country." So my suggestion was that the senhor should return to Manaos upon the steamer; and I offered as a sop to his dignity the proposal that he might well handle the disposal of our cargo in the city.

But, carramba, what an outcry the man raised at that! He made oath with the same paucity of expression that had hampered his son upon his first arrival, before he had learned a mouthful or two of good mouth-filling Portuguese. Would he go back on that steamer? Not for a minute, condemned by God; and might God condemn him too if he would now quit. He had come to take his son back to the family factory; and if the boy was too pig-headed to obey him now, by the name of the Saviour he would come right along with him until further vicissitude should have brought about to the boy a saner realization of where his best interest lay, and should have instilled some sound judgment into his head.

Verily I could see here the awful determination that was already sprouting in the son. A good enough quality for an up river man if tempered by just that thing—judgment. But what could I do? Could I, in the presence of the son insist that he should go back? Could the son order the father back? The matter was finally settled by the Peloroxo saying:

"Very well, Dad, come along then. It will be hideously uncomfortable for you. But, who knows? These upper rivers have taught me to realize that maybe the other fellow is right sometimes, even if he doesn't come from home. Maybe they'll show you that I'm not altogether wrong in sticking to my own business."

So at that it stood. We dropped down the four miles to the landing place of Santa Isabel and loaded up the steamer with the collection of nuts, giving receipts to the hotel keeper for the various deposits of castanha that we took; and we despatched it with a letter to the house of Araujo to take charge of our cargo until we should return. Then we started on our punitive expedition like a very fleet of Vasco da Gama.

Half a day up was the first of the side channels. A long island thick with cane jungle split the stream for a good four miles, and at about half its length two other islands cropped out on the left side and a third farther up on the right. Any one of the channels between these was wide enough and deep enough to shelter a boat while another might pass up on the other side, less than half a mile away and be unaware of its presence.

But with our fleet of canoes it was another matter. We divided them and sent a portion to scour each channel and to meet again at the upper end with the arrangement that any party that might chance upon the pirate steamer should immediately blow a signal upon a hollow palm trunk mambi, which instrument can be heard for a good five miles over the water. This method of progression was necessarily slow, but it was sure, and we well knew that not a canoe or a lone fisherman could escape those Indians without being reported.

The senhor asked a question—

"What is to prevent, son, suppose that a canoe party among whom there is no rifleman—or even our party with rifles—should discover this boat; what is to prevent it from just steaming away at twice our speed?"

I waited to see whether his river-craft would cope with this conundrum. And he laughed and told his father that one of the things that the upper rivers had taught him was observation; and that the answer to his question was just that—steam. For if he should come upon the boat lying up somewhere, it would not have steam up; while if it had steam up, since all those boats were wood burners, its smoke would betray it. But I asked him another question myself. What if the boat were to be hiding up some one of the tributary rivers which might extend for God knew how far into the jungle?

But he only laughed again and said to me with mocking—

"The same thing that you would do, my dear teacher."

And at that I was content to let it rest, taking a pride in my pupil before my other friends, yet standing by with my twenty years of experience to see that he might not slip up on some unexpected condition and so provide more ammunition for his father. Not a single chance was I taking that our quarry might escape us or that our Peloroxo might be dragged away out of our up-river country which needed him.

SO when we came to the igarape of Marié which flows in at the right bank I said no word but stood silent and looked at him questioningly. This Marié, while we called it no more than a creek, was a river of a good half kilometer's width and it stretched back into the jungle farther even than I knew. The Peloroxo pointed with his chin at the group of molocas on the shore.

"Where there are people living it is easy," he said. "Here we go ashore and ask. Do we take my stick or yours, amigo?"

"Let it be yours," I said, "and let us see its efficacy."

So we went, he and I and his father, in his batelão; and we sent his carved stick up to the council-house and awaited its reception. And, carramba, the deference with which it was treated was as great almost as I might have expected of my own. He laughed again like an overgrown boy.

"I told you, didn't I?" he chuckled, "that I am almost a neophyte of my witch-doctor; and he has carved me a very good stick."

And he explained to his father that these sticks were something like calling cards, or rather, letters of recommendation among the river tribes; that without them no white man would meet with a friendly reception and that no Indian would give him any information. It was, therefore, the ambition of every river man to possess himself of a stick; but only upon a basis of fair dealing would a witch-doctor provide a white man with a good stick, and according to their future dealings would a witch-doctor here and there add a rune or two to a stick. It was something of a conceit to me that my own stick was carved down the half of its length; and while I was never able to find out what it said about me, I presented it like an unopened letter of introduction and was satisfied that its effect was of the best.

And what do you think was the senhor's response? Instead of being glad that his son had such a good recommendation, he shook his head and groaned in his belly and said:

"My son, my son, I'm afraid you've slipped far in this lawless land from the careful training which good Dr. Poynter gave you back home. I don't know that I like all this pandering to heathen priests; and I'm sure that your Uncle Malachi and Aunt Sarah would not approve."

Well, Sancta mae, what use to argue with a man of so restricted a view? Suffice it that we were received in the council-house with all honor and that the ceremony of breaking the cassava bread and smoking the cigar was performed between us and the assembled chiefs and armed men. And, ho-ho, the senhor almost choked to death over the red-hot pepper sauce into which the ceremony demanded that he dip his bread. The chiefs told us then that the great smoke batelão had not passed up their river, but that hunters of the village had reported that they had seen it going on up river on the farther side of one of the islands.

THAT was four days ago.

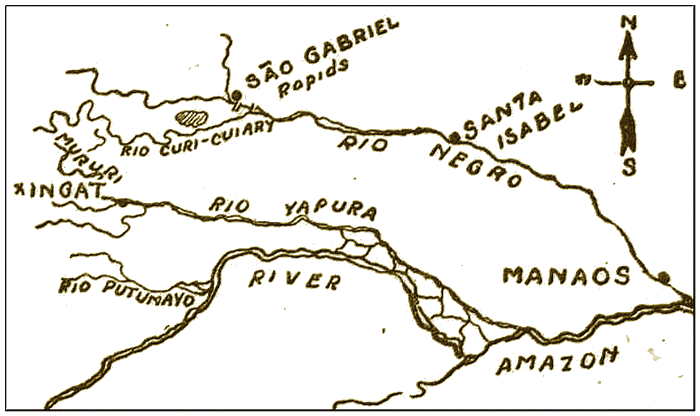

"Diabocito," said I. "Four days ago and going hard? Are they hoping perhaps to traverse the rapids of the Sao Gabriel and to pass through the natural canal of Casiquiari and so to come out in the Orinoco in Venezuela? Celestes, some of those fellows are desperate enough to try it."

"Valgame Deus! Would that be possible?" demanded the Peloroxo quickly.

But I shrugged. What could I say? Who knows what wild thing might not be done by crazy men in these rivers? Water enough there was; and if they could pass the rapids in so large a boat, who could tell what they might do? I have long since given up saying, "This thing or that thing is impossible." Yet I had no real anxiety. No man had ever made the passage in anything larger than a batelão; though the great American explorer, Dr. Rice, very nearly succeeded in a launch. But I had little fear that these rogues would have that much courage or initiative; and as I judged the water this far down, it was my opinion that there would surely not be depth at the Sao Gabriel to let so large a boat pass, however desperate and crazy they might be.

So we passed on up the great river, combing every channel and nosing into every side creek where even a canoe might hide. Clean channels where the water ran swift and carried a cooling breeze on the surface currents; sluggish channels where the high trees blocked all passage of wind and the air was fetid and heavy with the smell of orchids; twisted igarapes where the trailing lianas hung down on either side like a wall and the heavy orchid scent was overlaid by the stench of things ages long dead.

A pity, thought I, that no scientifico such as I have guided sometimes is not with us to take advantage of all this exploration. For never had that river been so thoroughly searched. Sometimes a full day would pass before all the canoes would meet at the upper end of some network of channels and make their reports.

Nothing. Always nothing. Tales enough they brought. Adventures and mishaps and accidents. Stories of giant serpents and queer beasts of the jungle and mysterious denizens of the black water. But no sign of a flat-bottomed stern-wheel boat.

The thing was beginning to be a mystery. One day a brace of canoes failed to turn up at the meeting place. Nor did they ever catch up with the rest. What mischance of the river had overtaken them, what beast or monster of the foul water, we never knew. Their fate remained a mystery and added to our anxiety about our quarry.

Had they, searching together chanced upon the steamer and been swiftly annihilated; and had the boat thus doubled back and escaped? But inquiry showed that the channel where those canoes had gone was too narrow to admit such a steamer; they had gone only because the order was to leave no channel unexplored. And then again, we had heard no shots. So we agreed that our enemies were still ahead. But the Peloroxo laid those canoes against their account.

"They were good lads," he said. "Nine of my own men. I shall exact indemnity from those pirates to pay to their families."

So we went on as before, combing our river from shore to shore and learning much that even I never knew of before. The question was put to me. Where could that boat possibly be headed for? Was it reasonable to suppose that those bandits, two of whom at least knew the upper water, would just keep running into the blind alley blocked by the Sao Gabriel? Yet what could I say? Who could guess what new thing might not be thought out by that gang between them. I myself have invented ways out of difficulties which had never been thought of before; and I had to give credit to Esteban the Heretic and to Diego of the Dog-Ears for cleverness. For ten years or more they had constantly affronted me in one way and another, and they still lived. So my only opinion remained that they could not pass beyond the Sao Gabriel and that they were surely hoping to hide somewhere in the odd thousand miles of channels until they could elude us and return down river.

THE senhor added a shrewd question, speaking hollowly through the wrappings that he wound round his face against the mosquitoes as soon as we made our nightly camp.

"It is poor business policy," he mumbled with his customary attitude of a teacher instructing lesser intelligence, "to assume without sufficient proof that your rival may be doing this or that. Why do you all of you assume that those men are desperately hiding all the time? There are about a dozen of them, you say. Lawless men and fighters, with the clever business head of this Sylvestra man to lead them. Why should they run away from the two of you whom they have succeeded in robbing once already? They know nothing about this fleet-load of your savage friends."

A question not without acumen. Yet to one who understood, was it not perfectly clear?

"Senhor," I told him, "you fail for once to give credit to the product of your home town. It is true that those fellows do not know just how efficient a pursuit has been organized. But they do know that behind them is the Peloroxo, this Fire-Head from that God's Country of yours, who has already made some small stir in our rivers; and that with him am I, Theophilo. Is it not enough?"

But the senhor was in an irritable mood, as was not to be marveled at, and we did not blame him. To sit cramped in a batelão all day is not like reclining in an office chair of mahogany, and to live upon dried pirarucu fish and rice is not like the menu of a grillroom, and to sleep in a hammock slung from the branches of a tree where the vampire bats hung is not like a feather bed. For us river men it was all very well. But for a gentleman of business who could find no extenuating allurement in the free life of the open trail, it was a sore trial for his temper. Wherefore he snapped back at me—

"If you're all so clever, it is a wonder that you don't send a few fast canoes ahead to scout and keep you informed."

A shrewd enough observation; and one to which there was no answer except a long exposition of the practical difficulties involved. But the Peloroxo came to my aid.

"No need, Dad," he said. "I telegraphed ahead from that last big moloca at which we stopped."

The senhor only grunted and remained silent. To him it was no impossible thing that his son should be sufficiently lacking in respect to jest with him. But the rest of us exclaimed in acclaim. We had heard it at intervals throughout the day as we had conducted our separate parties in our search; but no one of us had thought to attach its significance to ourselves. I turned to the Peloroxo and demanded of him what secret he was hiding up his sleeve now; and he said simply:

"I was able to persuade my ipage to send along a trocanawa with me. So, now that we are getting into inhabited country, we may expect to hear at any moment."

And said we in chorus that, sanctissimas, he must indeed stand well with his ipage. And so it turned out to be. Toward the end of the very next afternoon a light uba with one man in it came speeding down the river to meet us. His chief had sent him, he said, to tell the Kariwa Genipa—which means the Red-White Man—-that the smoke batelão had passed up the channel two islands outside of the main bank, going slowly, and that the time of the passing had been when the sun was low on the day before; that this matter was known because several canoes followed the boat in order to pick up the bottles which every now and then floated in its wake and which were very valuable for many purposes.

Without exchange of words the same thought came to all of us river men. One day ahead, and going slow meant, of course, that they had no inkling of pursuit so close behind. It meant also one day's canoe journey, going fast. The steamer would tie up to the bank for the night. Well then?

Here was where my knowledge of twenty years on the upper rivers was useful.

"Look," I said, "they have taken that passage that curves to the north of those two islands and of a mess of smaller ones, because it is the main channel and is free from obstructions. The southern main shore, where the moloca is, is straight, and the channel was made for us by Saint Gabriel himself—to whom I shall donate a silver bar. It is narrow and sluggish. Too narrow for the steamer in some places; but ample for us, and the current against us will be slight. If we travel all night then—"

I looked around for confirmation at the faces of my friends. The three of them nodded slowly and with satisfaction.

"Por graq' Deus," said one. "We shall perhaps catch them with banked fires at their tie-up."

And the other two felicitated me on my knowledge. But as for the Peloroxo, he was spending no time in conversation. With the brusk disregard for the conventional pleasantries which you Americanos always exhibit in times of stress, he was giving swift orders.

The long drone of a mambi sounded as a signal to all the canoes, wherever they might be, to assemble as quickly as possible at the first point above, where the channels came together; and while we were still congratulating each other at our good fortune, the paddle men raised their chant of "mm-hm mm- ha" and dipped deep and strong.

At the meeting place even less time, if that were possible, was lost. Orders were passed to the assembled fleet to prepare their meal at once and to eat well, for a hard all night travel was before them.

To us bateleros, who knew what a fuss and pother was invariably made by our Indians when anything came up to disturb the routine which was their custom, it was a cheering sight to witness how readily these four hundred or so of canoe men responded to their instructions. As for preparing a meal, there was no foolish delay about that; no going ashore and gathering of wood and fighting of fires. These men simply took a measure of farina meal in a gourd, swilled it round with water dipped from the river and gulped it down. The hungrier ones tore up a slab of pirarucu fish and ate it as it was, raw; and then all waved their paddles in the air to signify-that they were ready. In less than fifteen minutes we were surrounded by a sea of waving paddles. Of course, I, too, have trained my own crew to do likewise when occasion demands. But four hundred odd—

"Picaro," I said to the Peloroxo, "your ipage must have given you a most excellent magic over these people."

And he:

"Sure. Como não? Did I not save his reputation once as a witch-doctor by giving him quinine against a fever epidemic? And besides, I gave him a most excellent bag of salt."

WHEREAT we were all able to laugh; for it is through a proper dealing with the witch-doctors that we wise ones among the river men are able to control our Indians. All but the senhor, who murmured again his disapproval of all this working hand in glove with heathen devil-devil men.

But the Peloroxo had the temerity to laugh at him and told him:

"Don't be provincial, Dad. As a business man and an employer of labor, you'll have to admit that there's something to a system which can get four hundred men to work from sunrise to sunset and then to jump when you tell them and work from sunset to sunrise."

Whereupon the senhor for once was silent. Here was an argument along business lines which could not but appeal to him.

No need to weary you with the details of that forced march—or how shall I say? —forced paddle by night. We took the narrow channel of the southern shore and proceeded like a battle fleet. Four abreast and paddles thumping on the gunwales at the outward twist like the roll of a drum. Never had such a fleet traversed the great river. As a matter of custom it is a very difficult thing to get the Indians of the upper rivers to travel at all by night, for fear of evil spirits of the water which lay in wait for night-farers. But it was clear to any Indian that spirits could not prevail against a fleet of a hundred and thirty-six big canoes with three or four men to each and with our two batelãos to lead and to bear the brunt of any ghostly attack. Though there was a tendency among those in the rear to crowd in on those in front; till we called a halt and the three of my friends went back and took places in the rear guard to lend the strength of the white men who are proof against evil spirits.

After that we progressed like launches with engines. Those were good Indians of the Peloroxo's from the Marauia. Fifty-three miles we made in that night's travel, which is something for a river man to understand. Through that southern channel and into the main channel again; and such progress did we make that the Peloroxo edged his batelão close and called across to me:

"Por Deus, Theophilo, if we keep this up we shall come upon them in the dark; and then we shall indeed have a bloodless victory, since it is the rule, it seems, for up-river men to sleep all night without a watch."

To which I could reply nothing except that, if I knew Diego and Esteban, to say nothing of some of the others on that boat, we would do well if we made a victory at all.

And just so it turned out. By the ill luck of the devil—or was it by the astuteness of our enemies—we did not catch up with the boat under cover of the dark, in which case who can tell what might have happened. Daybreak was well over the tree tops when we rounded a curve, and there, snuggled against the bank less than three miles ahead lay the steamer. Almost invisible under the tree shadows in the morning mist which hangs over the water from the heavy dew in this dry season; but the jungle eyes of those Indians could see like a vulture's. They pointed with their paddles and raised a shout, and without orders bent to put in a final spurt. The Peloroxo shouted with them and called across to me:

"Allegrate amigo, she is ours! Look at the funnel. They sleep on banked fires. It will take them an hour to raise steam; and by that time we shall have them well surrounded."

But I, straining my eyes, which are better than his by reason of less book study, was not so sanguine.

"Look closely, my friend," I called back to him. "I do not know yet; but from here this little river steamer looks like a fort."

And it was indeed so. Those were cunning scoundrels on that boat; and it now began to be clear to me why they had progressed so slowly. They had been stopping, of course, to cut firewood. But, sanctissimas, what a store of firewood! And where do you think they had stored it?

On the lower deck in front of the boiler? Some of it, yes. Stacked in a parapet that stood all round, so that neither boiler nor engine could I see. And on the upper deck too. The forward part, where the wheel and steering apparatus stood ordinarily open to full view, was surrounded now by a veritable turret of firewood. The bow, both upper and lower, from where the cable passed to a tree on the shore was similarly protected; and at the after end, for no reason at all, except perhaps to offer a shelter from which to jeer at us, stood another fortification.

"Name of a thousand Beelzebubs!" I said to the Peloroxo. "That would be the work of that pock-marked bat of a João who boasts that he has deserted from three navies. This is a matter to be approached with artillery."

"Duck and rush in," was an advice which that Fire-Head had vaunted as a good rule of combat. But for once he hesitated. Nor did he laugh as was his wont in time of stress.

"Curse of the Father," he muttered. "If only we could have come upon them in the night! They might have been asleep."

And this time he didn't jest. But whatever might have been the case at night, it was clear that they didn't sleep now. Shouts came from the boat as the rest of our fleet rounded the curve and followed us in a straggling line, the speedier taking the lead. Calls and yells and clangings of furnace doors sounded from within that fortress of firewood. Yet we could see not a thing until presently the thin blue smoke that had been issuing from the funnel changed to a furious heavy black. And presently again, as we drew closer, a shot sounded from somewhere—we couldn't even see the flash —and a ball fell a hundred yards or so before us.

"We've got the range of them with rifles," muttered the Peloroxo. But that was all.

This was true, being a trick of my own inventing which I had imparted to him. For, though all the river carries the American rifles of Winchester .405, I have always taken the precaution to provide myself with a cartridge containing a one-third heavier load made by a German firm which is not so particular about the factor of safety as are your American regulations. A precaution which has tended to be my saving and the astonishment of my enemies on more than one hard occasion. But, pshaw, of what avail was a couple of hundred yards of extra range against a fortification?

OUR fleet bunched now like a flock of wary ducks, dipping paddles just sufficiently to stem the current out of range. At this hesitation on our part yells of ribald laughter came to us across the water. Too far to distinguish words; but I could well guess what those fellows were saying to me who had always exacted a stern respect from them. My gorge rose, and it was with difficulty that I was able to restrain myself from making some foolish demonstration. The Peloroxo was surveying his fleet of canoes and frowning ferociously. I knew what was in his mind.

"Would they follow if you were to give the order?" I asked him. He nodded.

"I think so," he said. "For the ipagi made a strong magic for me. Yes, they would follow; and we could surely rush them and capture the boat—at a cost."

"How many would you lose?" I asked again.

But he shook his head and returned the question to me.

"How many do you think, amigo, against that fort?"

"Some fifty," said I, "including perhaps some of ourselves. As for me, I have stood their insults. I am ready. But the men are yours. You are their general. It is for you to weigh naked Indians against tagua nuts and to decide."

But he shuddered.

"God preserve me," he said. "I am no military person to arrogate to myself the authority of the Almighty to weigh the lives of men against a fort in order that somebody's honor and somebody else's profit may be preserved. No, my friend. We can not rush them."

"Well, what then?" said I, "while we stand here they are getting up steam."

His eyes were searching the shore as he muttered to himself:

"Perhaps from the jungle fringe—I have held that boat for nearly two weeks from behind a tree— And you and I together, amigo, have cut that cable with rifle balls."

And with the same breath he called an order, and paddles dipped in a fury of splashing to land us on the shore just below rifle range. As we sped, a thought came to him and he shouted over his shoulder again; and half of the canoes fell off to make a wide circuit and land on the upper side of the steamer with our friends who had rifles. At the last moment, just as we landed, he had the temerity to bark another order—to his father.

"You stay right here in the boat, Dad," he commanded; and together we rushed off through the undergrowth. Truly that youth had an audacity that was amazing in the face of his parent. With a hundred Indians to swing machetes before us it took us no time to come abreast of the boat; and as we did so we took advantage of all the cover afforded by the tree trunks. In that heavy growth we could approach close enough. There, not sixty feet away, the boat strained against its cable. Sounds of men furiously at work came to us; yet not a living soul could we see behind that breastwork of stacked firewood. The thing was a veritable armored battleship.

A hopeless looking situation; and we cursed in our helplessness. The Peloroxo, peering from behind his tree, growled that we might organize a sudden rush of machete men and almost jump on board, so closely did the boat snuggle against the bank and so thick were the trees right down to the water's edge. But at the same moment, as if reading the thought, some unseen person on board shouted a sudden warning. Followed a rattle of machinery and a clanking of chains, and the great rudder swung over and so set itself that the force of the current drew the boat away from the bank. Not far. Not more than twenty feet. Yet enough. To attempt to climb the side of an iron steamer from swimming in the water, even though it was no more than four feet to the lower deck, would have been more foolish than to charge upon it with canoes in the open. The Peloroxo was leaping behind his tree with excitement and baffled anger. And, as always in such circumstances, he swore with the inadequate oaths of the American. By the evil one and by the inferno he shouted; if he could only see a loophole!

Loopholes those fellows must have left, of course. But who can distinguish a loophole between the round logs of tree trunks?

Yet, knowing what was in his mind, and having witnessed his speed with a pistol, I fired at random, hoping to draw fire in return. Which is just what happened. Two shots answered mine. One from the fortification, which was about the engine directly opposite to us, and one from the after turret. On the instant the Peloroxo's pistol crashed, and yells arose from both places.

"Thanks, amigo," he called to me, "that was well thought. That fellow at the end, I think, got no more than splinters from this angle. But I believe I got this fellow opposite here."

That was some small satisfaction. But, carramba, one cannot annihilate a ship's company through loopholes. Yet in connection with that word I had a thought and put it to the immediate test.

"Ohe," I called. "You of the ship's company. We have no quarrel with you. We know that you are coerced. If then you will—"

But yells of derision and laughter drowned out my words; followed by the immediate sounds of blows and a furious cursing; and a voice said—

"Listen to that Theophilo, the braggart of the upper rivers, trying to make an alliance with firemen and trimmers." And it was acclaimed with enthusiastic and ribald jeers.

That was Esteban, I knew; and I called:

"Listen, Esteban, you dung, I make you my promise now. It is simple. When you next see me you die." And in the silence I added, "And that goes for the next man whose voice I hear."

Whether any would have taken up the challenge, I can not say; for at that instant the Peloroxo's pistol crashed again and drew its yelp from some over-incautious peerer.

And firing broke out now from the upstream side where our friends were coming down. Some sort of opening must have been left in the front of the turret for the navigator to see through, and they were taking advantage of it. But it was long shooting and little could be hoped from it.

And in the midst of all the excitement I felt a tugging at my sleeve; and there was the Peloroxo's father, taking no cover at all and panting:

"Gimme a gun. By golly, somebody gimme a gun and show me how to shoot it."

I dragged him in behind a tree and shouted to his son to order him into shelter. But he, instead of coming to my aid, abetted his crazy parent and shouted encouragement to him.

"Whoop it up, Dad," he yelled. "Take Theophilo's pistol and blaze away at anything you see. Keep him behind a tree, Theophilo. I'm going to try for that cable again."

WHO knows what might have As the boat swung into mid-channel some of our canoes from

above, without anybody's direction, bravely put out with some

foolish notion of intercepting it. Those on board did not even

trouble to waste a cartridge upon them. They simply rode them

down and passed on leaving a trail of overturned canoes and