RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

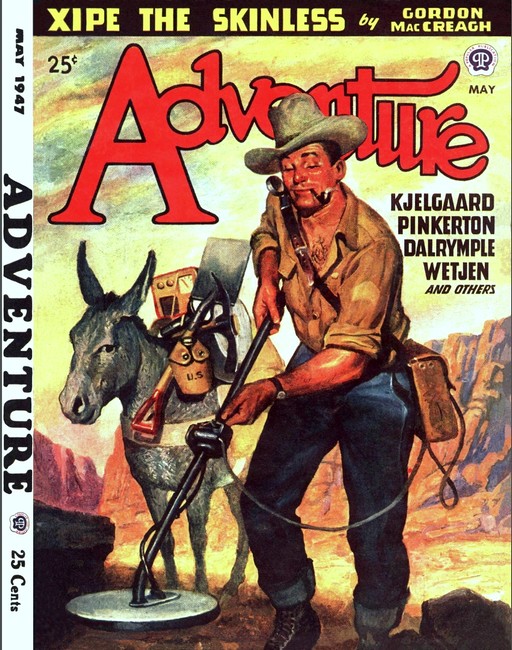

Adventure, May 1947, with "Xipe the Skinless"

A HOT spot isn't just the place where I'd expect to be finding a highbrow, and in a boozy brawl, at that. Especially not in Las Tres Cruces in Mex City, that, in spite of its sanctimonious name, is a joint that peaceful oil drillers like me would just as soon not be found dead in. I had just gotten out of a uniform with a skin pretty well healed over in spots and all I was looking for was some of this peace that they told us we'd won. I went into this cantina muchacharia to see if Hype Agnew might be there and needing aid and comfort against the enemy, like Hype often is. Hype wasn't there; but this Professor Burton was, and certainly a babe in the woods full of wolves.

You know how those things happen. There's no sane people in the world will act as dumb as we Americans when we're a stranger some place and we suddenly hear a familiar North of the Rio Grande accent.

Anybody who's been around at all has seen it happen every second day or so—what was that old song about "It's great to meet a friend from your home town?" Nor it doesn't have to be the old home town either. Just let it be an American voice, and people'll fall on each other's neck.

We're plumb provincial in that way; we've never grown up like—well, look at the British, for example, in foreign countries. Oo-oof! You don't see them going around kissing Cockney accents.

So well, this Prof had happened up with some lads and they were just the wrong gang for him; they spoke American, yes, but not his language; and they had gotten him into this girl-and-tequila trap and I could see that somebody was going to get knifed pretty soon.

That's another trick we have that doesn't get us loved away from home. We take a couple at the bar and that's enough for us to tell the world in a loud voice how superior we do things back home, and we don't remember that half of the rest of the world understands English, even if it's coming pretty thick on the tongue; nor we never at all remember that every country has some words that they write in blood; words South of the Border like "Spiggoty" and "Greaser."

It was none of it any of my business; but these lads were shoving their new pal around and damned if one of them wasn't even frisking him; and the rest of the clientele looking on and I could read it like print on their faces what they were thinking: "Look how the Norteamericanos behave."

And a bunch of British tourists, slumming, bunched at the door, thinking just about the same thing.

So I jerked this poor sap loose and told him, "Brother, you're ready to go home to your hotel—if you can remember its name."

I SHOULD have known better. I did know better, but those things get right under my collar. Because I live here. I mean, I came back out of the Army to see if I couldn't get my old job back with Petroleos.

Sure enough one of the loud gang, the biggest of 'em of course, shoved close and wanted to know where the hell I thought I was butting in. And, well, there's just two ways of handling that situation. One is to argue about it and the other is the way Army taught us—to sock the opposition with all you've got and do it fast. I don't know how come those guys didn't know about it, or whether they'd stayed out of the Army in a safe foreign country—they talked Mex well enough to have done just that last, at that; and, like I said, all I was looking for was peace—but I responded to the G.I. training. I socked the guy with all I had and did it fast.

It blacked him out, but the rest of 'em came right over the top. Why not? I was alone. At least for a while—for long enough to get a few solid ones and see the lights dance—till a couple of the bartenders wanted in and a slummer tourist said, "I say, that's a bit too thick," and he pitched in on my side; and the stripper girls screeched and some of the natives who hadn't liked the word "Spiggoty" took a hand; and the war was pretty even. And then the cops came.

Don't let anybody ever tell you we can lick the Mex police just because we're Americanos. I left the tough gang to find that out. I got my little Prof by the arm and out the side door to the Calle General Maximiliano Villalongin (that's a lot narrower than its name) and I staggered him along—I mean, I was doing the staggering because somebody had crowned me with a three-legged table—along to the wide Calzada, and there came roaring a bus. One of those red things that are always packed like a box of matches and you jump for it and hang onto other people's clothes who are hanging on themselves and they curse you and help you hang.

We hung as far as I guessed was safe out of the fracas and jumped off at the Alameda—without paying any fares, of course; sweet chance a ticket taker has to shove through the mob to the doorway.

I shook my Prof till I could get my own breath back and I told him, "What you owe me, sap, is your roll and likely your life and a new suit of clothes. Now, Mister Damfool Señor, tell me where you live and I'll put you in a taxi and tell him where to go."

Of course, I hadn't known he was any professor up till then; I'd seen him as just a little guy, looking pretty lost and getting a going over from the kind of compatriot of mine that I don't like in a foreign country. But the minute he opened his mouth I knew he was honest-to-God long-hair and Harvard, at that. He said, "I am in your debt, Sir, for extricating me from what seems to have been a hazardous contretemps." Not that he talked that way all the time when I got to know more of him; but he was on the edge of sobering up and he had to be careful about saying things just right.

To cut a lot of palaver short, he told me what I'd guessed—that he was new in Mex and, more, he was actually looking for some Americanos who knew their way about and he had run into this gang; or, curiously enough, they seemed to have made a point of running into him and they had been friendly as all get out and led him to what they said was a nice little place where they could eat together—The Three Crosses, migod! And they gave him something to drink that they said was almost harmless—tequila!—and then he didn't know much more. But he knew he lived at the Reforma Hotel and nothing would suit but that I must come up to his room with him and he was sure we could do some business together.

The Reforma, let me tell you, means money with a hidden cover charge for breathing its air; and, well, I hadn't gotten as far as getting my old job back yet—so I went on up with him to hear him talk business.

I might have known. His story had long gray hair on it. He was an archaeologist and he had a lot of moth-eaten sheets of Aztec maguey paper that told him where there was a cache of treasure; a fabulous treasure, he said—if he'd translated the picture right.

I told him, "Brother, fourteen million people in Mexico have been digging for Aztec treasure ever since Cortez and they've got the land hand-sieved about three feet deep. That's why they raise such good fruit."

But you can't eradicate the bug out of a good treasure hunter any more'n you can malaria. He wasn't offended, he was just superior. He knew what he knew and he went cagey about it; he wouldn't hint where the millions lay, not till we'd get there—he had all the symptoms. But his imposition was acceptable to a man who hadn't as yet got a better job. I was to shepherd him along and fix for mules and grub and all that and generally carry on the good work of being his guardian angel.

So we shook on a deal.

HIS name, he said, was Braden, Alvin G. Braden, with some degree letters after it, and that was sensible enough, even if he was going treasure hunting. He weighed around a hundred twenty and he had weak eyes—and, I found out later, guts too. I'm Diabhuid Donuil Tamms and I've always been sensible, even if my Dad was Scots and wasn't. He meant David—so the driller pals call me Dave, and sometimes D.D.T. I weigh into the hundred-eighty and there's nothing weaker about me than a driller can afford to have, only that I'm scared of getting into trouble—I've had all I need of it and I want peace.

So O.K., I asked the Prof where would he want me to have his expedition jump off and I'd go get organized, because what I've seen of treasure hunts they're always in the worst section of any country you care to name.

He said Papantla would be the jump-off; and I thought, oh-oh. Could just be that this lad had something more'n hallucinations. There's quite a piece of heavy jungle down that way and not so long ago they made a new discovery of an ancient pyramid there and I knew there were more that the scientific prowlers hadn't dug out yet. I know because I'd worked on an oil job by the Necaxa River and I'd hacked a little bit around the jungle edges with a machete and a gun. I tried Alvin G. out. I told him, "D'you know that the Indios down there are Totonacs, and they don't believe such a much of what the Padres tell 'em, preferring their old tlenamacac wizards, and they'd rather everybody would stay away, and some of 'em got blue eyes—which the scientific sharps don't know how come and, come their Xipe fiestas—that's the one for whom the old-timers used to flay their prisoners before ripping their hearts out with a jagged obsidian knife—they won't let strangers come fooling around their villages."

He didn't even hear that last. His eyes popped and he grabbed me by the arm. "Blue eyes!" he yapped. "You've seen them?"

Sure I had; and their color was quite pale, almost red-checked; good lookers, some of the women. The Prof breathed like he was having a revelation. "Evidence again," he said, "of Churchward's theory of Lemurian migration before it sank."

I didn't know what he was talking about. Then he deflated as he had steamed up. "Interesting," he said. "Astounding. But after all, not my subject. I'm alone in this."

And did that leave me flat! For a minute I thought I'd given him a lead to his buried hoard; but those highbrows can get excited about practically anything that has no profit to it as long as it's old.

"Alone," he said. I asked him what did he mean, alone? Wasn't there at least a collegeful of grave robbers who'd studied over those same maguey fibers?

"Oh yes," he said. "Why certainly. It's only that I disagree with De Peña's accepted translation of the glyphs."

And on the strength of that, of a quibble about what a curlicue meant, he was going treasure hunting! But a thought was beginning to itch. "Those good pals," I said, "who were frisking you. What d'you figure made them so all-fired interesting in picking exactly you up and spending their money on high-priced drinks in a muchacharia joint?"

He had no idea; it didn't even bother him. His reading of the curlicues was his own; he hadn't argued his theories with more than a dozen or so professors at any time, and they, of course wouldn't stoop to liquoring a colleague up and having his pockets picked. It must have been because the gang thought he might have some money about him.

I said, "Yeah? And how many students have those colleagues lectured to? No, you don't look to me like any rich playboy to draw the time and cash outlay of experienced tourist-clippers. And what's more, the little I've ever heard about archaeologists, they'd steal the Queen of Sheba's false teeth from their favorite blind kid sister and lock 'em up in a glass case so long as they were old enough to be chipped around the biting edge; and if there was any real buried treasure involved, well, that lets in one or two other people I could think of."

He said stiffly, "Mr. Tamms, I'm afraid your associations in life have left you rather suspicious of your fellow man."

Could be, I was willing to agree; because a man who's knocked around amongst the horny-handed sons of toil doesn't get so he takes them all for holy men. I decided, if I wanted a peaceful treasure hunt, I'd better go back to that creeper joint and spend a peso or two asking questions about the customers.

But I drew a clear blank. The gang was new, they swore; tourists just arrived, and most of them were in jail anyhow for some rough work during the fight.

It must have been pretty rough, I figured, for the Mex cops to go to the trouble of jailing them instead of just knocking them cold and throwing them out. But they must have been new, at that, although they talked Spanish, not to know about that side door. Nothing I could do, though. If the joint didn't know, I was sure those tough birds wouldn't tell me any secrets through the jail bars.

I went on down to Papantla to collect some porter peons; mules would never squeeze a mile through that kind of jungle. And in a couple of days I sent word to the Prof to pack his mosquito net and atabrine and come along.

HE WAS there in a couple more days, and I tried him out again. I took him to an outhouse hotel where if you know about it, the bricks are loose in the side wall so you can softly pick one out and peek what the girl in the next room may be doing. Not that I had much choice about it; the village doesn't rate any Sutler or Ritz. He never batted an eye. All he said as he looked over the mess was, "What is all the armament for?"

I didn't want to ride him; I said I was just a guy who always went treasure hunting with enough moral persuasion to keep the coyotes off nights. He asked, all wide-eyed innocent, whether I expected trouble. I told him flat, no; because I didn't believe there was any hidden loot left in Mexico; but if there was I'd bet a pack of bootleg brass shells trouble would come nosing it out like zopilote buzzards.

He just said, indeed, and would we be ready to start tomorrow? And I said, "Sure, where to?" And you could have blown me down.

He didn't know! He said we'd have to go in and ask around.

I said, "Lordamighty, are you telling me all the plans you've got is to machete a way into those jungles and ask the local peasantry where there's a pile of their sacred gew-gaws that even the Conquistadores couldn't twist out of 'em?"

He said quite simply, yes, that was it. Nobody else knew about this cache; only his reading of the pictures made it out that there was an ancient temple back in the woods.

And on the strength of that much he was going treasure hunting! I thought, hell, a wildcat well drills on better evidence; but who was I to argue against Harvard? So we loaded up the Indio porters and I took him first to El Tajin.

That's the newest pyramid they've found and enough excited científicos have tramped around there so there's a path; and they're still arguing whether it was dedicated to Zotzilaha Chimalman, the bat god of darkness whose job it was to destroy everything, or to Ipalneomohuani, the sun god who gave life. The names those old Mayas thought up! It just goes to show how much the studious boys know about it all. Only thing they agreed about was that it was one of the oldest buildings in all America and that there must be more of the same somewhere back in the jungle. So that was one up for my professor.

This Tajin has four sides, each exactly facing the four compass points, and 91 altar niches in each, adding up to 364, plus 1 for the top; which proves that the builders knew a lot more about astronomy—and I couldn't forget astrology and such wizardries—than ever the Egyptian priests did. To me it made no difference; I'd climbed up to the top and there was the usual old hollow in the rock to collect the blood and a channel to drain some of it off when it got too full. They've got one in the Museo Nacional—a "sacrificial stone" they call it. Those old-timers didn't care to whom they sacrificed their prisoners so long as there was blood. It was a creepy thought up and down my back hairs that nobody knew exactly what the religion of these Totonacs was today nor what they had of left-overs from the way back days.

Prof Alvin G. Braden never seemed to have any squeamish ideas. He prowled all over that pyramid and wasted half a day on it and got nothing. We'd have to go on, he said. So we made about a day's crawl along what might have been a coyote trail to an old mound that must have been older even than the Tajin, for it was just a pile of rubble. And then suddenly we were surrounded by a dozen or so Indios and all of them had machetes a yard long!

Our porteros just grinned and I could bet they'd known all along that this was the end of the road. They grunted the sounds that are Totonac and then they told us, "Prohibido el pasaje"—Passage forbidden!

And then it came to me. One of those weird ceremonies of theirs was coming due. The Fiesta of the Voladores, the Flying Men, and that's another something that the científicos don't know the why about, but the Totonacs swarm in from their inner jungles and pull it off every year slam in front of the church, and the padres have been tipped by the government to lay off or there'd be an Indian uprising.

THE PROF let out a yipe. Not because of the freely-handled machetes, but because one of those ruffians had blue eyes! As way back a savage as any you'd find, and he looked doped, sort of hypnotized like—deadpan, with his eyes wide, and while he looked at you you knew he wasn't seeing you. You know what I mean, like a zombie or something. All he wore was a maguey cloth skirt and his hair was a pure crow's nest, but his hide might almost have been a well-baked Coney Island lifeguard. Of course my theory always was that some strong-blooded old conquistador hadn't given a hoot about the Mann act when Cortez came storming up from Vera Cruz. But my Prof went farther back; he yipped about migration from Lemuria again and he jumped for this near-blond to peer into his eyes and turn him about and generally handle him like a museum piece.

The others set up a yammer like it was sacrilege and one of 'em stood clear and made to take a swing at the Prof that would have split him in two; but I shoved a shotgun up against his belly—I never fool with anything so uncertain as solid ball in close jungle—and the situation froze.

The Prof didn't even know about it. He was gibbering words and pointing at the rubble pile. I don't know what they were; not American, nor Spanish; they were noises like some of those twisted mouthfuls of ancient gods' names. The Indios gawped at him like he was miracles happening and their tough scowls turned to look less like fight; and then you could have rocked me again with a breath. Damned if he wasn't talking Maya!

He didn't know Spanish, this Harvard highbrow, like everybody else—but Maya! What I mean, he wasn't conversing or anything like that; but he knew scraps of some of those words five thousands years old or whatever, and of course I'd heard that some Maya had come through to the Totonac talk.

The Indios gawped and some of them slid into the jungle and in a little while they were back with a man who looked like a hundred and thirty years old and wore a red mask with a jaguar's skull as a head-dress, and my stomach heaved up to where I could taste it. As a driller I'd turned up enough old stones to know that that outfit represented Xipe, the god who had no skin and so he liked to have his prisoners of war flayed alive before he ate their hearts all steaming hot. I didn't know what this old tlenemacac was play-acting, but I swung my shotgun over to let him see sense in being reasonable. But the Prof gibbered his magic words and the medicine man gibbered them back with a better pronunciation and I don't know what all the two of 'em made out of it; but presently the wizard coughed at his strong-arm boys and they edged back into the jungle like dogs, watching us all the time, their lips quivering, and the old man adopted the Prof right there. He took him by the arm and led him around a corner of the rock pile and scrabbled away some dirt and showed him a stone, and the Prof went all the way batty.

Like the stone. It was carved with the figure of a man flying with skins stretched over bamboo spreaders like a bat. If the Tajin was a mere five-thousand-year baby and this was older it meant that some brainy lad had been civilized enough to think about flying long before the Wrights. The Prof wanted to pry the slab loose and he babbled about a priceless find and the Harvard museum must have it.

I told him, "Migod, man! You can't loot antiques that way. Those good old days have gone. Antiguos belong to the Mex Government. But if your museum has any rating and you can pull official strings they may let you find a millionaire angel to buy it for you."

His shirt stiffened right up and he made that crack again about the kind of people I must have associated with, as though folks who worked for a living ought to know what kind of rating his college collection of potsherds had, and he capped it with, "But nobody knows we've found it."

As though that squared everything. I'd already told him what I thought about an archaeologist's conscience and here was just one more proof. Not that I thought it any sacrilege to lift an old carved rock, but I wasn't laying myself open to a Mex jail for thieving the people's antique culture.

But the wizard settled the whole thing. He just covered up his rock again and grunted at our porteros and they told us he said that we'd have to go back, and when this Fiesta of Flying Men was all over we might come again and perhaps he'd let us through, depending whether anybody got killed at the fiesta. I didn't know what that could have to do with it; but I knew damn well, if we did come back, that carved rock wouldn't be there. It meant something to those Totonacs.

The Prof just about cried; but I could hear those machete men rustling around behind the lianas and I took and shoved him along the way we'd come and he babbled about practically having proof now of his interpretation of the old maguey pictures and about Lemurian culture and another old unfound pyramid and what all.

What I knew about lemurs was they were a kind of nocturnal monkeys with big eyes and long fuzzy tails and they wailed in the banana tops like ghosts. But he said, "Don't be stupid. Lemuria, the Pacific continent that sank some ten thousand years ago. Muria, Muya, Maya, don't you see?"

I asked, migod, did he believe in those yarns, like Atlantis and all that? and he wouldn't commit himself; he said, oh he didn't know, but there were quite a few students of history before its beginning who argued that there were traces of some such lost civilization on both sides of the Pacific; and then he shook it from him like it was of no importance. "It is not my subject," he said again. "The important thing is that their stopping us argues there is something farther in the jungle and if it's Maya we know that the flayed god was a son of the bat god of the night and they made splendid offerings of—" and right there, as he was on the edge of spilling some information about what was his own subject that he'd brought me here for, he switched. "And from where do you think the name, lemurs, came to your monkeys anyhow?"

THE devil an' all I should know about such riddles. He went on, half talking to himself. "And if I have impressed that old priest that I'm not just an idle tourist, or a robber, or something and we can go on through—"

What did he mean, priest, I butted in. "That old crow is a sure 'nough tlenemacac, a medicine-man hereditary pyramid warden from away back like the padres like to say there aren't any more; but you've seen him and your bits of ancient lingo have horned us into something that makes my skin creep."

He said in his professorial tone, "Really, Dave, you're positively naive. All priests of ancient times were medicine men, for the simple reason that they had the knowledge of the mysteries. It is only amongst the modern Christian people that they have lost it and don't know any more than you." And he added to that, "Or rather, let me say, even than I."

That's what an ordinary guy gets when he hob-nobs with the higher education. I had to cut him down to my size. I reminded him, "And what do you mean, you're not a robber? Heck, man, what have you come for? Even our Uncle Sam claims that treasure trove is half of it his."

He wouldn't say. I guess we weren't deep enough into the woods so he could be sure I mightn't spill the beans to some other archaeologist. Deep enough for me, though. What I wanted was a peaceful life, and though my skin was pretty crudely patched by a young Army doc who was strictly practicing, I still liked it well enough not to be begging permission from any priest of Xipe to go shoving into the tall timber where there might be another old temple with no police protection.

I told him all that and what did he think Papa Zotzilaha Chimalman and Son Xipe would think about a Christian Harvard man coming to swipe their ancient boodle and was it "splendid offerings" enough to make it worth while

He suddenly blazed with enthusiasm. "If it's what I think," he said, "it's fabulous." And then he dropped out of it "Well, it seems that if anybody gets killed at this fiesta we won't be allowed to go anywhere."

I hoped a fair dozen of somebodies would get killed at the fiesta.

They didn't. Only one did; though the way they pulled off their stunt, I'm surprised it wasn't more. This fiesta thing, to cut a lot of talk, was a repeat act of that old idea of flying. A gang of Indios danced—and right on the front steps of the church. They were dressed up in red and green with macaw feather plumes. Four of them were the pale-skinned kind and absolute deadpan, zombies like the one back in the jungle. They were sacred too; none of the others must touch them. They shuffled around and a masked guy hopped amongst them like a referee and kept whispering at them; not our jungle mummy; this one had a brown mask and he didn't rate so high, he had no jaguar skull. Another man with a drum and a reed pipe was allowed to hop close to them. Out front they had rigged a pole, a whole hundred-foot tree. They were going to "fly" from its top.

The government had sent down a científico to take it all in. He wasn't an archaeologist; he didn't care what people had done five thousand years ago; he was an ethnologist, he was interested in what they did now. He was reeling off movie film by the mile. The gang danced for hours—they always do at all fiestas.

I STROLLED around the crowd a spell, and I saw something I didn't like at all. They were a pair of unmistakable Americanos, dressed in the worst tourist style. I think I've said I'm a man who isn't looking for any fuss, but I had to know. I went up to them and said, "Hello, punks. How did you get out of the hoosegow?"

That's exactly what they were, big town toughies. They started, like caught in the act, and the rattier of them sniped, "What the hell d'you know about any hoosegow?" and then he recognized me. "Oho! You're the smart guy who horned in on our party at the Three Crosses. Well, Buttinski, we were smart enough not to get into the cooler. As smart as you, see. And that's something it won't hurt you to remember."

I said, "I never got to college to train my memory. And what all are you doing at a li'l old native fiesta? Improving the minds you haven't got?"

I could see the other punk's fingers curl, like he'd like to have 'em round the butt of a gun, and I could see the lump under his left armpit. He covered his itch with surliness. He said, "We're tourists. And who the hell're you to come asking free American citizens what they're doing?"

I took the two of 'em by their lapels to pull 'em close and whispered it portentous. I said, "Listen—and it'll be nice for you to remember. I'm Shotgun Dave. Sawed-off Shotgun Davie; and I can shoot a man's teeth out at ten-foot range from behind any jungle bush." So then I slapped 'em a good one apiece over their ears to see if they were remembering and I took care to crowd too close for any monkey-play with that gun. They remembered all right and I left it with them to mull over. I sure as hell did not like any of it. The same crowd that was frisking the Prof. What interest did they have in folklore and such? And I supposed they'd be smart enough to wangle their pals out of Mex City jail presently too.

I went to tell Mr. Alvin G. Braden. He was talking to the ethnologist of the Gobierno. That one was lecturing, "We don't know why they do it, nor just what its significance is. We know they've done it for a long time because Bernal Diaz del Castillo reports it from as far back as the Cortez invasion."

I said, "Heck, mister, it's way older than that. Why, we've seen a—And right there Professor Alvin G. Braden of Harvard ground his heel rasping down my ankle none just like any common bar-room horse tout. He said, "We saw a glyph in the museum that seems to indicate some such ceremony as pre-Colombian."

Yes, the Gobierno man knew about that, but they weren't exactly sure what it meant, and Bernal's was the first written description, and so he went on, "We know it has some sort of astronomical and religious connection, and that the risk they take signifies sacrifice. It is definitely a hang-over from some stubborn pre-Christian cult; otherwise why do they insist on flaunting it at the church door? It is quite obvious that those four bedrugged, or hypnotized, devotees who are going to fly are especially chosen initiates of the ancient cult."

My Prof asked, "Does Banisteria caapi grow in these parts?"

The ethno nodded. "We have not discovered any of those extraordinary telepatina rites here, but it could account for the apparent hypnosis."

It was all over my head, but I could get the next all right.

"And we know that if anything happens to them, if any disaster occurs during the ceremony, as for instance, one of them getting killed, it is a sign that their god is dissatisfied about something and it will be a bad year for them—unless they propitiate him with whatever other sacrifice he needs."

That was cheerful remembering a little later when the disaster did happen. What they did was, the man in the mask suddenly decided they'd danced long enough to call the attention of this man-eating god and he made the high sign and immediately the four dopes and the musician shinned up their mast with long maguey fiber ropes, and mighty thin they looked to me. Up top was a head no bigger than any mast head; I'll swear it wasn't more'n a foot square; and right below it a spidery little perch. The dopes perched on the perch, like birds—the ethnologist said their costumes represented Kinnich Kakmo, the fire bird. Then the musician pulled a stunt that would have turned any pole-sitter green. Damned if he didn't stand up on that square foot of board a hundred feet up in the air and dance! And tootle his flute and bop his drum at the same time! And presently the masked man yipped again and the dopes immediately threw themselves off their perch and started swinging around the pole on their ropes. Flying. Turning and diving like birds—far out and around, like a Coney Island airplane ride that does it with steel cables.

Thirteen turns they'd have to make, the Gobierno man said, and four men by thirteen multiplied out to fifty-two, which was the period of the Maya century and proved something or other. Zopilote buzzards came out of the blue nowhere and planed around to watch hopefully. And they were damnably right. One of the ropes broke, of course, and the flying dope was slung clear over a rooftop to crash on the cobbles in the next street!

The crowd of Totonac Indios who'd been holding their breath like I had mine set up a yowling and groveled and beat their heads on the stones. The rest of the village up and rushed around the block to gawp at the accident just as fast as any Americano crowd. The musician way up there broke his drum and smashed his pipe and threw them down; and as the pieces hit ground all the Totonacs quit their wailing and froze to the floor and the sun boiled down on a sudden graveyard silence. Nothing moved—only from up above came the thin swish of the other three flyers sailing through the air.

The Prof spoke, tight in the throat but determined as a hardrock drill. He said, "That means the Xipe wizard won't let us through at the Tajin. We'll have to find another way around."

I said, "My God! Still?"

The Gobierno ethnologist said, "Why around to where?"

The Prof said nothing.

I said, "Let's get outa here."

WE GOT out. There was nothing to stop us, nobody in the streets. Men, women and kids were all milling around the dead initiate of whatever it was who proved that their god was mad at them and would be wanting more sacrifice.

Back in the sweaty old hotel room I tried to reason with the Prof. But all he would say, as stiff as a drill-rod, was, "You are a free agent, Mr. Tamms. If you are afraid to go through with it I shall have to find somebody else."

I told him, "Yeah, and I know exactly where you can find two hard little potatoes who I'll bet are just as interested as you are to go wherever you are going treasure hunting."

That shook him for just a moment and he had to know what I meant. I told him about the two punks, and the way I sized them up they were as smart as they said, and they knew their way around enough to buy the rest of their gang out of the clink before too long—and then he'd have a real escort to fight through a whole lot of opposition.

He pursed up his lips—I'd never seen before how tight he could make them. He mulled it over, then he stuck by his guns. "I can't believe that any of my colleagues would try to follow me—even if they knew. But if somebody else may have got some sort of an inkling and hired, as you might say, claim jumpers, it just means that I shall have to hurry before they get free. I had hoped I could say, we shall have to hurry, but—" He shrugged disappointment. "Somehow I had judged you differently, Dave."

As clever as an old hand gang boss when the jinx hits the boring gear. I wanted none of it. I wanted peace. But when he put it that way—

I damned him and all I could say was, "Well, I haven't ever quit on a contract yet and I never thought a Harvard professor could be that crazy. But since you're so sure I'm sillier than you, O.K., we'll get up and git now and we'll see if we can cut in back of Tajin by the Necaxa River."

He grinned like he'd won a school debate and said, "Good boy, Dave." and he had to shake hands on it, like a new deal. We told it around that we'd seen the show we came to see and we were going home. We made a big show of hiring an old broken-down car and piled in our gear and we even shook hands with the hotel proprietor—whom we ought better to have killed—and we roared and bucketed off on the home trail.

And at the Necaxa the Prof paid the driver to go on to Mexico City for a vacation and stay drunk for a month and we bought a dugout canoe, as big as a matchbox and about as fragile, from a chicle hunter and went on. "And that," I said, "ought to shake the bloodhounds off of our trail."

I didn't know where to go any more'n he did; only, since the Xipe wizard had stopped us back of Tajin, it was good guessing that the direction would be that way. It took trigonometry to figure out how far to follow the Necaxa windings and then where to head by compass. Even the Prof didn't know any of that; he was an archaeologist, he growled, not a dry and dusty mathematician. I didn't know which of the two was dustier. So we quit our canoe when it quit us; when our skin was crinkled white from sitting hip-deep in water and bailing took so much time we made no progress. We hauled out at a village; what I mean, four chiclero huts on the bank. Chicle hunters don't live long, the kind of jungle they have to live in; so we could strike a bargain with four half-dead ones to carry our gear for us, for enough money so they could retire; nearly ten bucks apiece, and they insisted they'd have to have it in advance.

I asked the Prof, "D'you know what that means?"

He didn't. So I told him. "Means they think it's a fair bet we won't be coming back."

It was my last feeble chance to call it all off, but I couldn't discourage him. He said, "That's because the poor devils don't know about all the new medicines the Army developed for jungle work."

That man could shut his eyes to what he didn't want to know just as tight as any other schoolteacher. Where to head in was anybody's guess. The chicleros didn't know where any pyramids grew that nobody had yet found; but they had their trails that they'd hacked hither and yon, hunting for their trees; and a chiclero trail let me tell you if you don't know it, is no avenue that you stroll through standing up; you do it on your hands and knees and your belly. You make half a dozen kilometers a day and by the end of the first one you know why they are half dead.

THE rainy season was in its full middle, meaning that forenoons the sun made a Turkish steam room below the tree tops that you could never see—and afternoons, when those thick tropic drops pelted down, you swam. Even the monkeys quit that country in the rainy season on account of the mosquitoes that shoved 'em off their trees and ate 'em raw in the underbrush. Yes, we had head nets and cotton gloves and all the rest of the comforts that the Army thought it discovered for jungle work—though why the brass boys in Washington hadn't just asked some old oil explorer and saved a year's time, I don't know; and why the hell anybody would choose that country to build temples in was something else I didn't know.

The Prof said, muffled through the million different bugs that blanketed his head net, "There is considerable ground for the theory that climatic changes were the reason for the otherwise unaccountable disappearance of those old civilizations." And he could find his note of good cheer, "Which is all to our advantage, since that is why nobody has explored these jungles."

"Because they don't know how much treasure is buried in 'em, I suppose," I said. "Only you know, and thats mighty thin encouragement to me."

And he said, "Yes, I'm almost sure now that I know." Which was still a damn sight less encouragement than folks have who go treasure hunting on a phony map drawn on a pirate's shirt tail who never had any shirt.

Nights we slept in hammocks, of course, slung high so mud-fish and whatnot wouldn't nibble at us; what I mean is, we lay in hammocks and when we were so beaten dog-tired from crawling in the wet that we wondered how chicleros ever lived a year we sometimes half slept. So that's how I heard it. I hissed at the Prof and he was full awake in a second and I gave him the good news. I said: "There's a whole lot of something shuffling about ahead of this 'gator run we've been following, and it isn't animals."

He didn't have to guess what I meant.

"So you think, we're headed off again?"

"Damn tootin'." And I didn't care if he heard me chuckle. "And I can find my way back to our luxury canoe blindfolded and one foot tied to a stump. But how the devil an' all they located us here beats me. I know nobody followed us out of Papantla and even bloodhounds couldn't have trailed us downriver."

"I wonder," he said. "I wonder if it could be anything so extraordinary interesting as the telepatina."

And I said, "Yeah, I wonder. You talked about it with the other educated guy and I'm still wondering."

So he lectured. "It's an infernal nuisance, though a first-hand investigation of it would almost be worth while the time we lose finding another way through." You couldn't down that guy's stick-to-it-iveness after his loot; I wondered what Army outfit he'd served with. "You remember," he said, "I asked the ethnologist whether Banisteria caapi was found in these parts Well, it is a plant with some very curious drug properties. It was first discovered in Brazil by an explorer by the name of MacCreagh, who reported some hypnotic and anaesthetic properties. Later Dr. Rafael Bayon investigated it in Colombia and wrote a very learned monograph about it in which he insisted that he had witnessed more than one instance of telepathy under its influence, even to the extent of their curacas, or medicine men, showing evidence of receiving accurate news of distant events in visions."

I said, "And Harvard can swallow that?"

It always got under his collar when I said anything about Harvard. He said, "There is nothing so humorous about it as the ignorant laity might think. A whole library of serious literature attests similar evidence found among primitive peoples, especially among African witch doctors. Hitherto, it has not been reported here. An investigation at first-hand will be most valuable."

Well, maybe he was right. Maybe these uneducated primitive peoples got it like Dunninger—or who's the guy who does it on the radio? Or maybe it was just that; something as simple as little radio sets built into their brains. But we were both good and gruesomely wrong. I mean, about us being headed off.

Come morning there was a crowd of Indios all around us, about fifty of 'em, all with those yard-long machetes—and they weren't politely turning us back, they were taking us along with them!

Oh yes, we had our guns; shotguns, like I said. But it's only in movies that two intrepid white men can fight their way through fifty Indians in close jungle that grows up around your ears. We hadn't seen a movie in months; so we didn't have any wrong ideas about how many foreigners two good Americans could lick. The Indios gabbled at our chicleros and those hard-working boys didn't even ask for a tip. They said what must have amounted to "Thank you, kind sirs," and they skittered back into their jungle trails without a regretful look. A voice of authority coughed some twisty-jawed Totonac out of the bush scenery; some of the Indios hoisted our gear and some more of them told us in machete language that didn't have to be translated, to get going. We went peaceable.

THEY were Totonacs, of course—though all the Totonacs I'd seen up till then were city slickers who came in to make fiesta dressed in white dungarees. But you could tell by their Mayan beaks and their good looks if not by their clothes; for all the clothes this gang wore was breech clouts and their pale hides looked all the paler for a million little scars left by thorns as they shoved through the cat-claw lianas like tapirs. "Pachyderms," the Prof said.

There was one good angle to it, though. We didn't have to hack trail; they did it and we could toddle along practically upright, as good as monkeys anyhow. And they fed us—lye-softened corn tortillas and red hot meat that could have been monkey, and then again could have just as well been dog that's easier to catch; and of course cocoa with sticks of vanilla orchid pods to stir it with. Stuff to stick to your ribs, so I knew there was some hard going ahead and they wanted us to get there alive. I had my qualms wondering why.

The Indios were polite enough; I mean they didn't prod us with knives or knock us silly with clubs, like those scalp-tingling yarns about our own old-time Indian troubles. Authority halooed orders from ahead and we halted or twisted whatever way he said. A few days of that was as much as my nerve could stand—just scrabbling along through dim wet jungle, knowing nothing of where or why. I tried to talk to our nearest machetero guards and I knew damn well from their knowing looks that some of them could understand enough Spanish; but they just put on their owlish expressions and shook their heads. But they passed the word to the one in command up the line and, come afternoon cocoa snack about ten days along, His Nibs dropped around to call. And I got a cold jitter through my sweat.

The guy was masked! In shiny tin this time—and not with a jaguar skull on top—with a pink spoonbill's skin and long beak.

And why, you'll want to know, should a pretty water bird give me a qualm? Because that was Xipe again. Xipe had another hat too, the blue cotinga; I knew they represented Earth, Heaven and Hell, but just when he meant Hell I didn't know. The Prof didn't know either, but he was ready to lecture heathenishly:

"The concept of a Trinity, my dear Dave, is no Christian prerogative. It has been found in all early religions in all countries; a fact that offers some most interesting speculations for those who are interested in the evolution of religions; which; however, is not my subject. This man is obviously a priest again of whatever cult it is that has survived amongst these people."

I'd never had much dealings with priests at any time and the more I learned about those with ancient Mayan cults the less I liked 'em.

This one didn't mind talking; he said we were going to the "Place of the Old Ones" and that was as much as he would say. The Prof quivered like he'd been told we were going home for Christmas.

"He can mean nothing other than that they're taking us to my pyramid. Surely it can be nothing else."

I said, "Yeah. But why are they taking us?" His pyramid, he was calling it already. What I was wondering was, was it his, or Xipe's?

He said, "And do you know, my good pessimist, why his mask doesn't rust? Because it isn't tin, it's silver."

"So what?" I said. "I'm poor at sums, but I know that all the silver one man can dig up and carry away any fine night that he escapes from a gang of machete cultists amounts to about fifteen hundred bucks' worth; which is pretty poor treasure hunting."

He said he wasn't interested in silver. "So then what?" I asked him again. What was this "priceless" loot he was after that couldn't let him think about anything else connected with bloody old Mayan pyramids? And that sent him all dreamy-eyed again. "I'll tell yon," he said, "if they do take us to a pyramid—I mean, to my pyramid of which I think I have deciphered the correct translation from the glyphs."

"I suppose you'll scream it to me," I said, "as a last minute item of good news just before they rip you under the fifth rib with an obsidian knife and drag out your pulsing heart and shout, 'Heil, Papa Zotzilaha Chimalmam and his raw red Son Xipe!'"

Sure I was pessimistic. Mexico is a civilized country—at least, in most of its spots. Indios don't snatch white folks and take them away into the backwoods unless they're pretty damn stubborn and got secrets, and what I know about primitive people's secrets, they're as nasty as Nazi. The Prof had nary a doubt; he had come to dig into a secret loot and here we were in secrets up to our necks; so the way he figured it, he was right on his way to "something fabulous." How he was going to get away with it, he seemed to be leaving up to me that he'd hired as his trouble-shooter. Well, I'd be glad if we'd just get away with our skins and back to a peaceful life.

WE CRAWLED along that way, in mental darkness as dim as the thick woods, doing our good four or five miles a day, for ... I don't know, I lost count. The silver-faced wizard every now and then pulled a queer stunt and he was so sure of things, he didn't care who looked on. What he'd do was pull off a little ways from the camp-fires—I should say, the camp smokes—and he'd drink something out of a gourd, bowing to the four bacabs—that's the little gods of the four compass points. Then he'd settle himself and begin calling on the name of Tezcatlipoca, intoning it sort of like a bell. Tez was the god who rushed around on the four winds of the bacabs and so he knew everything that was going on everywhere. If we had him, he'd be the god of Associated Press.

So the wizard would call Tezcatlipoca and take another slug out of his gourd and then call him again; and presently he'd begin to get glassy-eyed and dopey—which was no more that I'd expect, taking it raw like that. But the Prof got all steamed up about it.

"Good Lord!" he said. "That must be the iage or caapi! We are seeing the fantastic thing happen before our eyes."

I don't know whether it was honest magic or just some of the hocus-pocus those fellows have to do to impress the peasantry. But in a little while the wizard would drink himself cock-eyed and mutter himself plumb hypnotized. Like those dopes who flew, though not so deadpan dumb. His eyes would remain wide and he'd cock his head like listening and then his lips would move like talking hack.

"It is the telepatina," the Prof whispered. "Just as Doctor Bayon described it. He is talking to an attuned mind; or perhaps to the tagepai, the visionary midgets who carry messages."

A funny thing about education up to the eyebrows is that you know so much you can believe anything can happen—or nothing. Not that I don't have an open mind; I can swallow anything anybody'll show me, but no visionary midgets. Anyhow, in about half an hour the wizard would groan out of his binge and he'd have all the news. Some of our machete guards were talking to us now and they'd say, "He has been consulting with the One Who Orders." Which was easy enough for any priest to tell his true believers and so long as he didn't guess wrong too often his stock would hold good. But one time after he'd gone through his act they told us: "He says that the Mexicatl Teohuatzin has ordered another party of nine men to meet us and then we must turn east."

That meant the very boss high priest, and in the good old days he was the lad who threw his trance and had a revelation about the date the gods wanted for the next sacrifice of prisoners and how many hundred of 'em. Maybe a name as powerful as all that had some authority over the iagepai midget telegraph messengers, for damned if it didn't click!

Two days farther on there was a halloo from over to our left and a party of exactly nine men sloshed through the woods to join us, and who was one of them but our mummy of the Tajin with the jaguar hat!

He went through a set of high signs with Spoonbill, which, if I knew anything about it, I'd say they were Masonic; and then he came over to the Prof and said, "I warned you."

I couldn't see his expression, of course. But I sure didn't like that word, warned. It sounded too like we'd stuck our face into something nasty and it was nobody's fault but our own. But it never fazed the Prof, even if it soaked in. Nothing would suit him but he must try out that caapi drink. Spoonbill's voice that we couldn't see through his silver mask chuckled. He said, "It will make you very sick, for the iage requires an apprenticeship of many years. But you arc a student of the ancient mysteries, so you will doubtless consider the experience worth while." Anybody who was interested in their ancient mysteries they considered tops.

They had him sit apart and they gave him a couple of nips, no more; and they were right with some to spare. The Prof was as sick as I've ever seen a poisoned dog. So sick, it left him dizzy—maybe dopey, I don't know. Anyhow he went dreamy-eyed. When he came out of it he said he hadn't heard any news, but he was a whole lot pepped up.

"I am experiencing an extraordinary exhilaration, an uplift beyond all mundane worries. And as a matter of fact, that is what MacCreagh reported of the Amazon Tucana tribes. They called this caapi the 'drink that makes men brave' and they made use of it in a ritual of defying the evil spirits of the jungle. And true enough, I feel that I am afraid of nothing. I am care-free of whatever may befall."

I told him, "Yeah, I've seen it happen to people from something mixed by a wizard of a barkeep."

He laughed at me; he was sure having none of my worries about what we were heading into. Not even as he handed me the exact cause of them. "And don't you see, my obtuse friend, it is probably this caapi that accounts for the intrepidity of those flying men as they went into their dangerous ritual; and also, no doubt"—this was what got me—"for the apparently hypnotized calmness, as Bernal Diaz points out, of victims who went unresisting up the pyramid steps to certain sacrifice."

He was so pepped he didn't even know he'd said a mouthful. I was remembering what the other sabio, the ethnologist, had said about somebody needing some more sacrifice if anybody should get killed at the flying pole fiesta: and I had my own theory about why our jailers were being so all-fired polite to us too. I told the Prof about it later, when he wasn't so hooched up he couldn't think, and, by golly, that gave him the first jolt I'd seen him take.

A FEW days later the wizards went into their caapi trance and gave out a press bulletin that we'd pick up another gang day after tomorrow afternoon. With both of 'em on the beam it ought to click, and it did. Half a dozen men and two women joined in; it looked like a gathering of the clans for Christmas turkey. One of the women would have passed for a beach brunette and had a figure that would have got her into the final judging in any bathing beauty contest; and she dressed the part too—just the lower part, in a maguey cloth apron.

Even the Prof took notice. But what he said was, "You will observe that these women are no subservient slaves to their lord and master men; they seem to be on a basis of equality. There is no doubt in my mind that these people arc some remnant of a superior civilization."

"Sure," I said. "Maya—Muya—Lemuria. Like your Churchward wrote; and if the women have so much say-so maybe one of us could work up a Pocahontas act and have her save our neck."

"Why not?" he said. "Why don't you try?"

Which I didn't mind trying. I sloshed alongside of the prize-winner and started to pour out the fatal charm, and what scared me again was that nobody chased me—they acted like I was a hungry G.I. and the world owed her to me.

So well, we slogged along that way, as determined as mud turtles, till I figured we must be getting into Guatemala at least, if not Panama. And then one day the boys told us, "Tomorrow we arrive."

"Where?" I asked.

"At the Place of the Teocalli," they said.

I told the Prof, "The Place of the Beautiful God," and he showed me his erudition. "Theos, meaning God, and kalos, beautiful. It's practically classic Greek. How did they get it?"

"I know," I told him. "The Greeks got it from them by way of Lemurian migration through Atlantis before it sank."

He didn't take credit for all the baloney he'd taught me; he only grunted, "Getting clever, aren't you?" I told him, yes, and I knew something more too—that some of the científicos, as they argued about their guesswork, twisted the translation round to mean, "The Beautiful Place of the God." And at that he whooped.

"That means a temple, or pyramid. My pyramid!"

And of course it was. But what a letdown! When people talked about a pyramid I thought of something like the Teotihuacan or Uxmal or Chichen Itza—things as big as those in Egypt. This thing we'd come to was just a dump. Oh, big enough, a small hill; but just a great pile of rubble that had weathered off in the course of centuries and rolled down to cover up whatever stairways and such all. It would take a Smithsonian expedition to clear it up and hope to find on ancient carved rock underneath.

Nobody lived there. They'd be batty if they'd ever want to in that oozy jungle. But there were a lot of temporary shelters, lean-tos and rain sheds. You could see that some of them were left-overs from a couple of years back, patched over with fresh palm leaf. Some fifty Indios were camping around, men, women and kids, most of 'em the good-looking light-skinned type.

The Prof whispered like he'd discovered something. "A remnant, obviously, of an old, old race."

So what? All the científicos agree that Mexico is mixed in with old, old races, likely enough the crowd that built the pyramids. What I was worrying about was whether the gang had been collected up to sit in at some nasty old, old rite.

Silver Face did the honors. He told us, "You are welcome, A house will be given to you and food will be brought by young women."

The Prof said, "Well now, that is hospitable enough, surely, to allay your worries."

Maybe, I thought—but why did they bring us under machete guard? The machete boys turned us loose and Silver Face and Jaguar Hat went off together. That was all. We were free.

Swell of them. So now we could go wherever we wanted. We could start hiking back through I didn't know how many miles of jungle and in any direction I couldn't guess. And how far would we get? Go on, you tell me. I didn't even try to figure. The Prof said, "We must examine this pyramid."

NOBODY stopped us. They didn't mind us heathen prowling around their church. So we prowled. It was, like I just said, a great mound of rubble. It could have been any of those old volcano vent hills in the jungle; only that somebody kept it trimmed off of the bigger trees. You could see that nobody used it except for special occasions—like this one.

So then I began to grow a hope that maybe the pyramid didn't have any nasty connection with us after all and I asked the Prof what he thought. He said, "Pyramidology is not my subject. Unless, of course, this would turn out to be my pyramid of the glyphs. Let us go round and see what is on the other side."

We sloshed along a path through solid waist-high cactus, the kind that's so thorny they grow it for hedges to keep the hogs out of the yam patch. And round at the back they'd scratched away enough of the old rubble to show the usual wide crumbly steps going up to the top; and I let out a whoop as the hope I'd been growing sprouted 'way up.

Not for the steps. I grabbed the Prof by the arm and I yelped, "Look! This crowd of cultists, whatever they've forgotten or twisted around, are Christians!"

What I'd whooped for was standing up solid and comforting as a church, even for a guy who didn't patronize them any more'n I did. Two great stone crosses, no less!

About a hundred yards apart they stood; one of 'em man height and the other some four times as high. Hacked out of single great chunks of stone by loving hands, like the old Indio converts used to do in the front yards of every old cathedral started by the Franciscan monks who came with Cortez.

The Prof let out a yelp too; or rather, he sucked it in through his teeth and he whispered it out, "It is! It can be no other. My pyramid!"

I was feeling a whole lot better than I had ever since we'd stuck our necks into this gamble. I said, "All right, you stand well with the masked priests because you're a student of the ancient mysteries; so you get permission and I'll dig this pile away for you single-handed and let's get at the treasure."

He couldn't tell a lie; he took his little hatchet and hewed his first nick out of my sprouting little peach tree of hope.

"They aren't crosses," he said.

He'd laughed at my ignorance often enough, so this was my turn. Heck, I could see them, couldn't I? I walked up and made sure I wasn't pipe-dreaming. I slapped my hand against the littler one. Good solid stone by loving converted hands. I even knew where there was another one exactly like it in front of the oldest old convent near Mex City. And just like that one, this one was different. What I mean, the ends of the arms were carved into three fingers and right in the middle was a face. A bit crude, it was, of course, and pretty weather-worn; but a face with its tongue hanging out; and it had a thorny spiky crown around its forehead too. So I laughed and hooted the Prof.

He couldn't stand being laughed at. He took another slash at my tree. "Look at that face. The round eyes, the flat nose, the hanging tongue. It's the same as the center of the ancient Calendar Stone in the museum of Antiquities in the City. The Sun God. And the crown isn't thorns, they're sun rays."

And, by damnation, it was so! My knees went limp and I had to lean against the thing. "But then, what about the other one?" I blatted. "The one in front of the convent?"

"Carved," he said, "doubtless by some Indian slave under the whip and allowed to stand by ignorant people who did not, at that time, know the symbolic significance."

"Well, what the—" I was beginning to be scared of the thing and I backed off of it.

"It is an acolmite," the Prof said, like that explained everything. I guess my tongue must have been hanging out as long as the pop-eyed foolish faces, so he went into his classroom lecture: "The cross, my dear David, was a marker monument long ages before it became a Christian symbol. In Egypt it was erected along the Nile banks to mark the rise of the yearly flood, and when the water rose as high as the crosspiece it was known that there would be a good crop and there was general rejoicing. In Ur of the Chaldees, before the Mesopotamic silt caused the recession of the Red Sea coast line, there was a cross at what was the Bahr El Iddin, used as a range marker for mariners. In Maya times such markers had an astronomical function, as had also their pyramids—and for that matter, too, the Pyramids of Cheops and Khephren."

FOR a man whose subject was not pyramidology he sure knew a lot about them. I wish I'd had a Harvard education instead of just good common sense. "You mean," I said, "these things are gun sights, to pick out when the sun would be in the third house of Venus and in trine with the moon?"

I had to let him know I wasn't entirely dumb. I'd paid five good bucks to an astrologist once to have my fortune done on a chart and he used all those magic words. I remembered them five bucks' worth.

Damn if he didn't agree with me. "Probably to plot the course of Venus, that had considerable pre-Mayan importance," he said. "And you can see, sighting between the first two fingers of this left hand, over the top of the farther cross, you get a line to what must have been the truncated cone of the pyramid before it crumbled; and beyond that is where Venus should appear in the sky at certain times. Similarly, sighting over the ninety-degree angle of this arm to the top of—"

I couldn't hear him any better than I could understand his heavenly bodies. My head was buzzing. He had chopped my sprouting hope-tree plumb to kindling. I was so worn flat—yes, and mad at all his superior lessons—that I gave him what I'd been holding off these many days so as not to worry him.

"All right then," I said. "I can't argue with you, you've got it all down pat. So now listen while I tell you what I know about Mayas and whoever it was that was pre-Maya, like you say these near-blonds are a left-over from. Listen good:

"They've been polite, haven't they? They've fed us, hacked a path through the thorny lianas for us, and now they're giving us a cozy home and women to rustle the chow, and I'll bet it'll be the best they've got. And d'you want to know why? When the Mayas needed some sacrifices they picked the best of their prisoners and fed 'em and clothed 'em and gave 'em girls to play with; and when the sun, or Venus or whatever it was, hit the right spot over the range-finder they marched the whole troop of 'em up the pyramid and sure 'nough sacrificed 'em. Sun gods and Venus gods and Bat gods with skinless Xipe sons, all got their quota. So I'm wondering which god the range-finders will point to, come the next bright day."

That got under his lecture-room hide all right. It had all been lessons to dummox me up till now; but this was putting us on an even footing, right up our own little alley that we'd busted our way into. I thought he ought to know all about those bloody Maya tricks already; and maybe he did, only he'd never thought it could happen here. He looked at me like half doubting. So I felt mean enough to give him some more.

"And I'll tell you what isn't guessing or believing travelers' tales out of old books. At Chichen Itza, that isn't such a helluva distance from hereabouts, is the Sacred Well. There they'd give the picked boys and girls a grand party and weigh 'em down with jewelry and heave 'em in—and if you want to doubt that, I know the American consul who wangled a permit and got a diver to go down and fish up a truck load of bones with the gold bracelets still on 'em."

Yes, he knew about that, because it was modern history and some of the museums got some of the loot. He didn't have any lecture to give this time. He was swallowing great lumps, digesting it all down. But he had guts; he wasn't ready to quit. He said, "Those victims were bred to believe it was an honor to be sacrificed and so they possibly didn't try to escape. We—" I couldn't grow another hope-tree. Like I said, I had hard common sense. Escape? Hell, they could treat us like princes while they waited for their astronomy to swing around, but they'd be watching us by the second; they'd catch us within the first mile.

And they proved it right now. Silver Face and some of the boys came edging round their rubble pile to see what all we were doing with their crosses that weren't any Faith. Hope, and Charity, but were range-finders to a date in the sky.

The Prof had his guts all right. He said, "We can't let them see we are afraid." And he peered and sighted along the arms and fingers of those cursed acolmite things and made some of the old Maya noises that he'd learned out of books, and durned if Silver Face didn't just coo over him. He had me translate that the Prof was sabio el mas simpático and, what always seemed to impress them most, that he was a student of the ancient cultures, and he'd have to come and see the Mexicatl Teohuatzin himself. That was the One Who Orders.

The Prof took over where I had quit and started his own li'l hope-tree. "If we can impress the high priest," he whispered, "this may be an opportunity for—" But he didn't have any idea for what.

They took us to our new home first; and I didn't like it one bit. It was quite one of the best bamboo and thatch huts in the clearing. And presently the promised women came along with supper, and I didn't like them a hoot either. They were beauties. This was too much like the old tradition of treating us like princes in order to fool the gods they were getting somebody worth while.

AFTER supper Silver Face and Jaguar Hat came together and took us off for the promised chat with the big shot. The Prof had been building high on this interview; but my liver, as the Indios say, turned to water and oozed out at my foot soles.

Mexicatl was masked and it might have been gold, for all I knew or cared. What set my back hair crawling was that his head-gear was the blue cotinga! And that, if you remember, was the third emblem of Xipe! The one who liked his meat flayed before he got it!

This one was old too; you could tell by his hands that looked like somebody else's much bigger, peeled off and used like princes who knew all about astronomy—if there are any of that kind of prince these days; though, what I've heard, the Maya princes had to know all about it to qualify as the elite. It kept me guessing, first, to understand what the old wizard was saying, and then inventing to try and explain it to the Prof.

I didn't do so well, so there had to be a demonstration. They took us out to the crosses—I mean, the cursed range-finders—and there was Venus blazing like an arc light over the shoulder of the pyramid. Only the range-finders didn't range right. Even I could see that when you took sights over the notches that Venus wasn't where she should be. Where he should be, I mean, because his name used to be Tlauizcalpaantecutli, and with that much name to keep up with he was a hungry god and I'd seen him carved in stone as a snake with all of a man disappeared down his gullet but the guy's face that still struggled between the snake's teeth.

But it got the Prof all excited; all pepped up like he'd proved something. He said, "Tell them, why of course: That since the period, obviously very ancient, when these markers were set up, Venus, owing to the precession of the equinoxes, is quite perceptibly no longer where she used to be." And was that a helluva note to ask a guy to translate into Spanish! "But, tell them," the Prof promised like giving them back something they'd lost, "that in about some twenty-three thousand years or so she'll be back exactly where the old astronomers marked her." And he was all hepped up about it. So much that, though I couldn't care a whole lot what happened twenty-three thousand years from now, I had to ask him.

He said, "But don't you see, my dear man, that, even without delicate instruments, we can take the minute variation—" He could see I wasn't understanding, and he went into a schoolteacher's impatient rage. "We can roughly measure, my good fool, the distance between where Venus is now and where she would have been when these markers were set up, and we can then calculate back to their approximate date, whether Maya or pre-Maya or—" He went into a starry-eyed dream about it.

I was making all allowances for both of us being pretty well nerve-strained, but I didn't like being named a fool before company in that stupid-kid tone of voice. I said, "Or Mu. Your Lemuria before it sank, as proved by Alley Oop in the funnies."

For a wonder it didn't rile him this time. He was in his dreams. "At all events," he sort of whispered, "it would be evidence of cultured man on the American continent infinitely antedating Egypt or Chaldea. And then, if I have translated my glyphs correctly—"

He dreamed happily on. Sure I got it, but I couldn't enthuse. He meant, of course, if he'd read his maguey papers right his treasure story held good, and right here was the spot. Helluva lot of good whatever tonnage it might be of treasure would do a couple of prisoners being treated like princes, fattened for the kill till Venus would show up where she ought not to be, but might have been when the marker were set up ten thousand years ago or whatever. Which left our date for doing the last mile up those pyramid steps pretty well up to the close harmony of friends Silver Face and Jaguar Hat and Mexicatl Teohuatzin.

They weren't hurrying about it. They left us to have our good times any way we liked; though how princes had any good time in all that rain that came through the thatch roof was beyond my guessing, and how they lived long enough for the fiesta before the bugs ate 'em up raw was another mystery. But the Prof harped back on his climatic changes and said it couldn't have rained so much in those gay old days. What I wondered was whether they hadn't perhaps softened up some of their jolly old customs in this modern rain. But my hope-tree wouldn't sprout again.

THE women they sent to housemaid and waitress for us were the best on the lot. I could have been interested if I'd had the guts of the Prof, figuring a way out of where there wasn't any way. The chow, too, was a heap better than a lot I've lived through; wild pig and monkey and yams and all—though it did give the Prof a turn to have one of the blue-eyed cuties serve up one day a dish of roasted monkey hands on a banana leaf. Me, I never liked that gristly stuff, like pig knuckles and all.

And they brought us worse—what turned my stomach. Jewelry! What I mean, bead necklaces. Old, old crooked bits of stone that could have been jade, and some of 'em turquoise, that must have taken a month's work to bore a hole in each one with cactus thorns and sand abrasive. "Museum pieces!" the Prof breathed and had the nerve to wear his.

I told him, "All it means isn't that they're not honoring us sufficient; only that they've used up all the old family gold and silver pieces, heaving 'em into wells or burning 'em with loud hurrahs to Ixi-Poxi-Hoochi-Cattle or whatever twisted monicker he had."

He said, "If you are so infernally pessimistic why don't you do something, instead of just sitting waiting?"

As though these was anything a guy could do. Why didn't these other old-timers who were being fattened up like princes do something? Where would they run to, I asked him, and how far, with midget spooklets radioing their progress all the way?

He was getting sort of hot and bothered himself now, what with inaction and knowing nothing. I told him, "Well, for gossakes, let's put in our time digging for your treasure, since they let you do anything you like. We can at least look at it, even if we can't take it with us to where we're going."

But he said, sort of hopeless, "It's nothing that can be dug up."

"What d'you mean, not up?" I said.

"It is something hidden in some small niche somewhere about the pyramid, or perhaps in some hollow in a stone idol. Perhaps one of the priests may make use of it when—" He gulped down the rest of the when.

And if I hadn't already been lower than the belly-scales of a lizard would that have left me flat! Not about the loot not being buried; but about the words, small, little. Migod, it'd have to be diamonds to make it worth while; and nothing I'd ever heard about the Mayas, or Pre-Whoever-they-were, ever said anything about the Mex jungles growing diamonds.

The Prof wouldn't elucidate. All he'd say was that it was one of the most ancient sacred symbols in the world and therefore "priceless," and he clammed up on his personal translations of his blasted old maguey papers like he had something religious that mere laymen mustn't meddle into. I've noticed that about those hard-bitten científicos. Nothing sordid about them; they don't want money; all they want is something nobody else has got; and let 'em get onto a secret, they hug it like their hope of heaven—those that are so stuffed with education, they don't believe in heaven. Me, I'd stuck my neck into this, looking for sordid money, and I wouldn't have stuck it half a mile beyond jungle fringe if this crazy clever fanatic hadn't outsmarted me, talking words like fabulous, and priceless.

But I couldn't believe him all that much of a nut—heck, he was Harvard, wasn't he? I said, "Well, I suppose you've got some millionaire angel who'll buy it for his pet museum."

And he said, "Well, yes." And, "Let us go and talk to the head priest." As though anybody ever got money out of a head priest.

So we went and squatted in the wet with Mexicatl of the blue cotinga hat, who hadn't a hut as good as ours. He was polite; he was cordial; he was our long lost brother—and he could keep secrets as well as the Prof. So we talked astronomy. What I mean, he talked sky-piloting that I couldn't understand and I invented explanations so the Prof would guess what he meant. The Mexicatl was awful interested in Venus. The Prof was just as interested in explaining to him all her straying from the ancient path in the sky.

ALL of the chatter got us nowhere; not to any little niches in idols, nor even to when might be the zero day. But Mexi did say, dodging around my questions, that his people were descended from Fair White Gods.

"Lordamighty!" I had to splutter. "That old Cortez baloney again?"

But the Prof shut me up; he was eating it up. "He means, supermen, of course, you fool," he said.

I couldn't even kick at being a fool any more. And the blond supermen came, old Mexi said, from a great island in the West where they had known all about everything—like flying and all that. But they got too smart, it seemed, and the gods got mad at them and sank the whole kit and kaboodle of them.

So there it was again. Lemuria, Muya, Maya—and, for that matter, the old Bible flood and the Polynesian inundations and the Tower of Babel or whatnot—I'm not up on those things, nor I wasn't giving a faint hoot either. Even the Prof was so low that he couldn't get steamed up about proving anything.

All he could lecture was something out of the Bible that I didn't know he'd ever read. "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy," he mumbled.

I said, "C'mon, let's get back to the girls they've given us. They at least have golden, sunburnt faces and not a gold mask; and I'm taking your advice on 'em too."

"What do you mean?" he said. "I never advised you about women."

But he had too. "Pocahontas," I reminded him. And true too. I wasn't building a whole lot on it; but I was trying my sweaty, unshaven durnedest to make the proper hit with Hedy and with Lana and with Myrna—I couldn't sort out their other names. Not that anybody handicapped like I was, what with trying to say pretties under a dripping tree and my hide wrinkled leper white, could expect to get anywhere fast; but they were sort of cooperative. They didn't know any of the rules of civilized catch-as-catch-can, but they sure didn't mind who looked on from under the next wet eaves, any more'n a Saturday Coney-Islander.

It was the Prof who added some cold water to the warm rain. He said, "If your pessimistic theory is correct, they won't be of any value to us, however successful may be your amours. If we are being fattened, as you say, for the feast, they will come with us."

It sure shook the ardor. But if they knew all about their cursed hang-overs from some beastly old religion, how come they could giggle and slap back?

He said, "They are in the limelight, the cynosure of all the populace, and all women enjoy that." He surely had tumbled off of his own flourishing hope-tree. "And furthermore," he hammered in another nail, "it is possible that they are being given small doses of the caapi drug and are abnormally exhilarated beyond concern for the future."

I went to Silver Face and told him I wanted a daily slug of caapi. He was polite. He said, "The women will bring it." And that was worse than if he'd said no. If I'd be needing something to deaden pure stark fear, Migod!

But, well, the way things turned, I never got it. There was what Army used to call a diversion. Not meaning fun, but the enemy cutting in from another angle. Excitement buzzed around the hut warren. The masked tlenemacacs remained in long huddles. They drank the magic hooch and talked out loud to their invisible midgets; and at last Silver Face came and gave us their wireless long distance. It whooped me up more than a barrelful of any booze.

"White men are coming," he told me.

"White men? Here? How did they ever find their way, and why?"

"Bad men," he said. I didn't believe him. I was ready to count any white men as pure shining angels.

"They have caught some of our people," the old boy said sadly, "and they are torturing them, the same way the first white men did, to show them the way. They come with guns and we cannot at present prevent them."

At present? I found out suddenly that I knew how to say a prayer and I said it out loud, the way our colonel used to: "Dear Lord, let the advance hold its drive."