RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

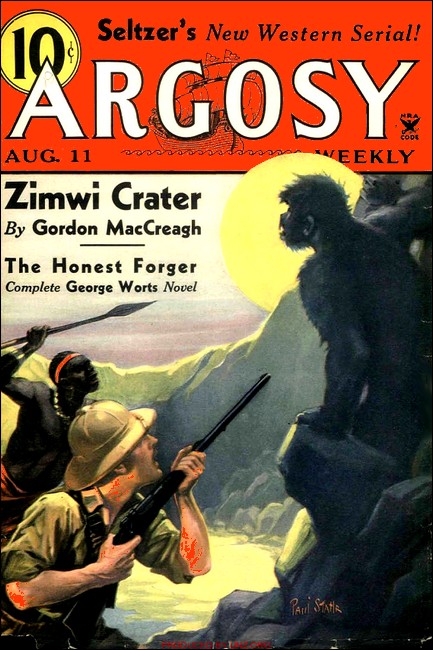

Argosy Weekly, 11 Aug 1934, with "Zimwi Crater"

WHITE hunter Dane was dead set against it; and; it was Dane's business to know Africa.

"You've got one o' those damfool notions," he told Reynolds, the construction engineer. "There's a whole lot o' superior white men like you who laugh at African superstition. I'm telling you to let it alone till we got some daylight to look into it."

Reynolds dangled his legs over the tailboard of the little ton-and-a-half truck, in which the two men had bumped over the roadless plain from Number Seven camp, and laughed as he looked across the peaceful moonlight at a low, steep-sided cone that rose ghostly out of the night mist.

"Ah, pshaw! Ogres! Homicidal ghosts! You don't look like you're nervous about any of that kind of bunk."

Dane looked like anything else but. His was a big-shouldered, sinewy frame, a face hard and sun scorched with alert eyes, and a wide mouth. He took no offense at the implication of being worried.

"Listen, mister," he was not afraid to admit, "I'm here, alive, and with all my own hands an' feet, because I'm scared of anything that I don't know all about in Africa. This is new country to me. All I know of it is that the natives call that hill over there, Jubali ya Zimwi, the Crater of the Ogre; an' I know enough about natives to know that they haven't wit enough to invent something out of nothing at all. They'll embroider a yarn; they'll exaggerate it. But I've seen enough of African weirdness to tell you to let it alone till daylight."

Reynolds still laughed; though shortly, and under his breath. Loud laughter seemed to be a thing curiously inappropriate for two men alone in the immensity of Africa. They seemed like ghosts themselves, these two lone humans. Like eerie half-men who floated on nothing.

The night was one of those sudden, clammily cool ones that sometimes come with the early moon. Like a moist blanket, a white mist hung low over the ground. Above the mist protruded the torsos of the men; half a mile distant, the steep little pale-gray cone of the ghost crater; farther away, other round domes of rising ground. From beneath the mist-pall came the sounds of midnight Africa. Far off, somewhere, a spotted hyena howled its gruesome, whroo-oo-ee-ee, ending in its high pitched, idiot shriek; and closer another answered it, chuckling and giggling insanely.

Reynolds shivered. "Lord! Whoever called that ghastly noise a laughing hyena?"

In the ensuing stillness lesser noises came. Soft feet pattered; something suddenly screamed; stones clicked and clattered; voices of nothing whispered and sighed over the tragedy of life in Africa.

Devils, the natives said. Evil spirits that met and told one another of the deaths that they knew of in the night.

From away in the direction of the ghost crater came a low, rumbling voice of deep volume that vibrated and shuddered in the still air.

Reynolds involuntarily jerked his feet up out of the mist.

"Ha! Lions!" was his immediate guess.

Hunter Dane sat hunched with his arms locked round his knees. His big frame was shaken with a spasm of shivering.

"Yeah," he grunted. "They've got an obsession down in your office in Nairobi about lions an' they hired me to kill 'em off, so you could run your road in peace. But that was no lion."

"How do you know?"

Dane was ungracious, and pain was racking his joints.

"It's my business to know; just like yours, an' young Anson's down to the camp, is to run a road an' know nothing else. There's some lions around, but none right here; an', so you don't think I'm guessing, I'll tell you how I know. As we drove from camp we came out o' thorn bush an' grass country into bare ground an' rock. I couldn't see it under this damned mist, but I could feel it. Game doesn't eat sand an' rocks, an' where there's no game there's no lions."

That was simple enough—for one who knew. But Reynolds was piqued. "Then if you know so much, what was that noise?"

Dane ruminated darkly over his answer, turning over in his mind all the menacing noises that he knew. Then, "Damned if I know," he said. "An' I think I know every beast in Africa. An' I know enough about Africa not to fool with what I don't know in the night."

But Reynolds was feeling that he owed it to his manhood to show some independence; and he was secretly ashamed of having snatched his feet up when that curious roar had come. He slipped from the tailboard of the truck, and immediately only his trunkless head floated above the mist. "Then if there are no lions, there's no reason why I shouldn't scout around a bit. I'm not afraid of ghosts or ogres."

"Listen, Mister Chief Engineer," said Dane. "I've warned you, an' that's all I can do. I'm not your boss, an' I can't hold you. Nor I can't come with you, 'cause I'm due to go under with this damned old malaria any minute now. I've taken forty o' quinine and half a bottle o' Warburg's. I'll kill it all right, maybe by tomorrow. But, right now, I can't go galloping around the night; an' I know you couldn't carry me back."

"Sleep it off," said the floating head. "I'm going to catch your ghost and you'll wake up in camp tomorrow."

Another spasm shook Dane; and with a curious effect of a rolling football, the head drifted away on the mist.

The crunch of boots on gravel died away. The lesser sounds that had stilled re-awoke, curiously sublimated, and difficult to locate under the mist blanket. The little people of the night scratched and scuffled. The evil spirits whispered to one another in glee at impending tragedy. Feet pattered round the truck. Something sniffed windily at the wheels.

Dane did not know what it was; nor was he in a condition just then to care very much.

"Damn fools rush in," he began the familiar quotation; but the chattering of his teeth cut off the rest.

The roaring noise from the direction of the ghost crater rose nearer than before.

Dane could distinguish a sound of murderous menace in it this time. Not lions, he was sure of that; but some queer thing of immense volume in its voice.

"Damn know-it-all fool!" Dane chattered again. He wished he might go out and drag the man in, boss or no boss, by the scruff of his neck. But his limbs were gripped in such shivering spasms that he could not even sit upright.

The thing that sniffed round the wheels snarled angrily at something else. Not lions, Dane knew dazedly. Could that fool look after himself, against even these other lesser things that groped below the enveloping fog?

Then that other unknown thing, of the huge voice, bellowed again. A roar of giant, half-human triumph—and something screamed! Horribly! Hoarse with terror and awful pain. It shrieked again and was suddenly strangled short. Enormous sub-human laughter gurgled out of the mist.

Dane heaved himself onto one elbow, groping for his rifle. But the nerveless arm slid from under him at the effort. The fever surged over him in hot waves and he, as he knew from past experience he would do, went out.

IT was late afternoon when Dane drove the lurching truck over the tussocks of bunch grass into camp Number Seven. Dane, hollow eyed and drawn, but steady on his feet and very steady and hard around his mouth. He stalked into the tent where Anson, the assistant-engineer, sat wondering, fretting in helpless ignorance.

And it was little that Dane could add to it; and that little only added to the unbelievable horror.

Anson was young and his experience of Africa was nil. There was courage in his fresh, good-looking face; but he listened to Dane's meager recital with dilated eyes. His reaction was stereotyped.

"Lions!" he murmured. "It couldn't be anything else!"

Dane was merciless. "Yeah," he said. "I knew you'd say that. So I brought this along."

From a wrapping of bunch grass he shook out onto the camp table a gruesome object. A bone, freshly yellow, picked cleanish, with shreds of sinew and raw flesh clinging to it.

"Do you know what that is?" he asked the staring engineer.

He filled Anson's goggling silence himself.

"It's a thigh bone! Human! An' as you see, broken through the middle! Snapped like a pipe stem!"

Anson drew away from the thing. "Lions!" was the mumbled reiteration on his lips. "Damned hyenas!"

Dane shook his head, sombre-eyed. "Something much more complex an' damnable than just lions an' hyenas."

"How d'you know? How can you say that? What else would?" The jerky questions came from Anson, half fearful, half defiant "You can't believe anything so impossible as ogres."

"Lions," Dane pointed out conclusively, "could crack a bone like that. So could hyenas. But—there's not a tooth mark on it!"

Anson stared at the startling truth. To read the signs of the jungle was not within his scope as an engineer.

Dane elucidated further.

"Whatever killed this, an' had strength enough to smash it that way, was not an eater of meat. And, what's more, having killed, it didn't go away an' leave it. It stood guard through the night; else the hyenas would have got at it. With daylight, it went away, an' the vultures picked the bones clean. So, figure that out, for one of the things that nobody can believe about Africa."

"Good Lord!" All the arrogance was gone from Anson. "Good Lord!

What frightful thing would do that?"

"Yeah," Dane rasped. "Frightful is the right word. An' new to me. D'you know whose leg bone that is—was?"

Anson gaped at him, too fearful of his horrid suspicion to ask. Dane filled in remorselessly.

"Reynolds's! At least," he went on, admitting doubt about what he himself could not understand, "I guess it's Reynolds. That was where the shrieks an' devil-noises came from. An' that's all I know. The ground was too hard for any tracks. So I'll tell you what we're going to do, you an' me."

He threw his sun-helmet aside, and sat down on a camp-cot.

"Now, let's get this straight from the start. I don't like roads. I'd rather they wouldn't come busting through the back bush. I hired out to your crowd in Nairobi for one reason. 'Cause this road will go an' open up way-back into the Latwa country; an' that's where the traffic an' the derned tourists will go, an' so they'll stay out o' some other country that I want to see left alone; where I can take my hunting parties.

"So, I hired out to your crowd under Reynolds as boss. Now—until they send out another big shot to take Reynolds's place—you're the boss. So, listen. We're going out, you an' me, to look over the ground by this crater where you've been trying to establish your advance camp and been having ghost trouble. An' we're going by daylight. An', when we've got the layout, like sensible folks, we're going to hunt down this ogre thing. No devil beast is going to get away with snatching off a man I hired out to look after."

Anson looked at the man, fascinated, dominated by his hard determination to tackle he did not know what, and by the cold logic of his plan of action. Slowly he nodded agreement.

"Good!" said Dane. "You've got sense not to make a fuss about authority. Now, if you've got the nerve to stand by, and a little more sense enough to know that the white man doesn't know everything better than the African in his own country; by the time we're through with this business you'll know enough about Africa to boss the next man your company sends along."

To that Anson also nodded. "I hope," was all that he said.

"Good! There's not enough of today left; so we'll go tomorrow—on foot; so we miss nothing, an' we can take cover. We can't afford to lose any bets against this Thing."

An indication of Dane's respect for whatever the Thing might be that inhabited the old crater, was that he talked very seriously to his chief of safari.

With this staunch companion of many journeys into the far borders of the unknown, he had none of the traditional white man's superiority.

"Old friend of many fights," he told him, speaking in Swahili, which is the common language of exchange over most of Eastern Africa, "you have heard the tales of black magic and of ogres that devour men. What Thing this may be that lives in the bowels of the earth, and issues forth to raven by night, I do not myself understand. Whether man-made deviltry is connected with it, or whether it is all beast, out of a long-ago past, I do not know. What think you of it?"

The headman was a Galla from the Abyssinian border; a ferocious spear-fighting people that never were subdued, and have been called the Zulus of the North. Mozumbu, his name, which meant, in his own language, the One-Horned Rhinoceros. An immense fellow, superbly naked, except for a calf-skin apron. His great black chest and shoulders showed innumerable little white cicatrices and scars of past fights.

"Gofta," he said quite simply—Gofta being his own term for the Swahili "Bwana," or Lord. "What have I to do with thinking? Give but the word, and we go forth together to give battle to this devil-beast."

Dane's hard eyes lit with little gray fires.

"I knew you'd say that*" he laughed shortly. "We go then, to-morrow. Make all ready."

THREE men, therefore, marched out from Number Seven to find out whatever it

might be that came from the crater at night to trouble the advance camp. The

country approaching the advance began to rise. Sudden upheavals of tumbled

rock lifted like islands out of the yellow plain of high grass, above the

waving of which, groups of horns and widespread ears showed here and there,

and other groups of black-and-yellow striped backs barked shrilly and

galloped away.

"Good lion country, all right," said Dane. "Plenty of dens an' plenty of meat. An', over there, in that mimosa thorn patch, a couple of miles ahead, one has made a kill an' is sitting guard over it till supper time."

"How do you know all that?" Anson could not help suspecting the truth of things that, to him, were utter mystery.

Dane only smiled thinly at the unbelieving tone, and pointed to the sky above the thorn patch.

"The buzzards are circling, waiting. If the lion had eaten and gone, they'd be down, feeding."

And, sure enough, an hour later, when the party waded through the hampering grass to the thorn-belt, that reading of the book of the jungle proved correct; though in a manner more gruesome than Dane had anticipated.

Excited natives of the road-gang met them, yammering, white eyeballs rolling, chattering that it was Juma, the brother of Moosa, the lion had taken in the night.

Anson, in his quick relief from incredible beasts of the night minimized the tragedy.

"There, you see? I told you it was lions. You, with your doubts about wizardry and ogres! You've been too long in Africa, Dane."

Dane was serious. "I can make my mistakes, same as other folks—maybe more than some who know Africa. But"—he was doggedly insistent—"that thigh-bone was no lion's job; nor anything else that I know, 'cept that it had the will to kill, an' a tremendous power. However, this is another matter. A lion that will take man, with all these zebras around, an' good cover to hunt it, must be a confirmed man-eater. We'll have to go in an' get him, before he gets another one."

Anson was taken aback. "You mean into that thorn-scrub? Right into his lair?"

Dane nodded coolly. "A lion, poor fool, is a gentleman. He growls first, to let you know he's coming. All you got to do is hold your nerve an' not miss. I wouldn't go after leopard this way. A leopard'll rush you without warning," he slid his rifle bolt, and slipped a cartridge into the chamber. "Come ahead. Better let me lead."

WITH the suddenness of a blow, it came to Anson exactly what was meant by bearding a lion in his den. He knew that there were men in Africa—men who had known Africa too long, perhaps—who did it as one of the stark necessities of the jungle. Legends, those stories had always sounded to be; sagas of the pioneers.

He was courageous enough himself but, to be dragged into a sudden personal participation in so crazy an adventure was blood chilling. Yet, perforce, he had to go. To hang back would have meant utter shame; for that was what the chattering native boys did. Though the Galla, with a vast disdain of the Wa-shenzi, men of an inferior breed, stalked silently after his master.

Dane picked his way cautiously through the stunted thorn trees. Wherever a denser tangle appeared he approached it, with rifle ready for an instant shot, looking for spoor, or blood trail. In the more open places he went ahead more easily.

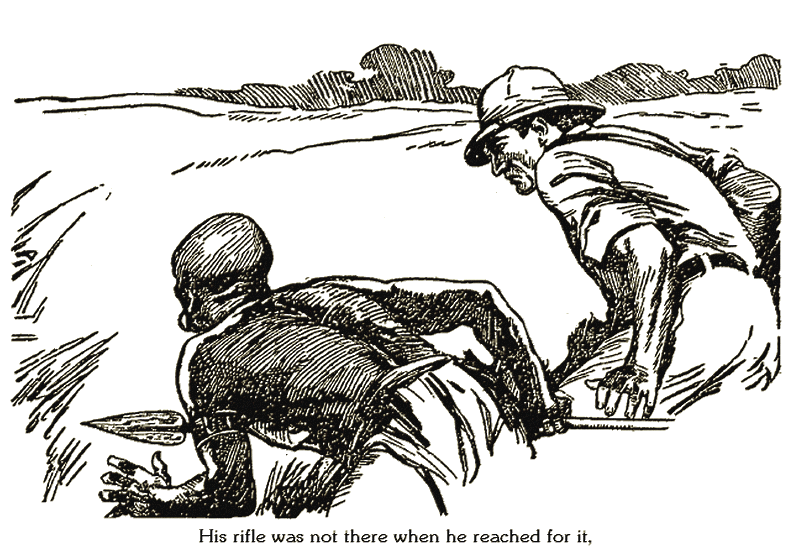

It was in such a place that he made his mistake. A dragging boot-lace bothered him. No man going after lion wants to be hampered by anything that might, with the devilish perversity of inanimate objects, twine itself round some protruding root at a crucial moment, and open the door to death. Dane handed his rifle to Anson to hold, and knelt down to tie the lace.

And it was just that moment that was the crucial one. A lion can hide, behind an unbelievably inadequate shelter. Its coloring, designed by nature to blend with dry grass and sand enables it to merge into its surroundings as an integral part of them. From behind a low clump of almost nothing there crackled out the angry beast's preliminary roar; the ear-splitting series of coughs that herald the immediate charge.

Dane jerked up to his feet to reach for his rifle. Time he had plenty to line his sights and pick his spot. At thirty feet, was his rule, and aim at the white spot on the chin; then all that a man had to do was hold his nerve and press evenly upon the trigger.

But just there was the rub. A man must hold his nerve.

Dane reached for his rifle, sideways, his eyes on the charging beast. And the rifle was not there!

Better and more experienced men than Anson had broken before a lion's charge. And without too much blame. There are few sights more promising of imminent destruction. A lion, its mane flying in the wind of its rush, its snarling gape, enormous at close quarters, its spread claws as wide as dinner plates reaching out, the knowledge of its enormous strength and of the lightning feline rip and tear. Men who have seen that sight without a weapon in hand have swiftly died.

And Dane stood weaponless. Anson had involuntarily, without knowing it himself, started back. He stood now ten feet away, nerve-shocked to immobility.

A lion can cover thirty feet in two seconds. Much less time than it would take Dane to leap to his rifle.

With the amazing clarity of tense moments it came to Dane that this was his finish. He was not the first hunter who had made his mistake, his one little unforgivable error in the jungle, and paid the jungle's price.

And then a swift black form slipped between Dane and the charging beast, crouching low.

"Give place, Gofta!" he shouted, and knelt in stiff steadiness. Now there was a superb display of nerve. The naked man, without even the protection of a tough khaki jacket against the chisel claws, kneeling with his spear to meet five hundred pounds of teeth and claws and rage.

Cannily the Galla dug the spiked butt of his weapon into the ground beside him, with cool precision steadied the point to meet the hurtling chest, and at the moment of impact let go of everything and rolled clear.

It was splendidly done. All in fractions of a second. The charging beast impaled itself upon the point. The great blade stood out behind its shoulders. The momentum of the charge carried the brute to the spot where the spearman had knelt a moment before, and there it rolled, roaring fearsomely and tearing the air to shreds with claws that flashed bright arcs in the sun.

In the same breath Dane gained possession of his rifle and fired. The flailing claws jerked in a spasmodic reach, stiffened, and slowly sank, quivering.

"Lord!" came a strangled breath from Anson. "Good Lord! That was close! Awful close!"

Dane slammed a fresh cartridge into place and stood watching the quivering shape warily. When it moved no more a great inhalation swelled his chest and exhaled slowly through wide nostrils. Then he said quietly:

"That was well done, Mozumbu. For such service there can be no reward, but equal service in return."

The Galla grinned hugely with pleasure, but quickly covered his mouth with his hand to hide his emotion. He affected nonchalance.

"Between men what is such a small matter," he said. "It has happened many times back and forth between us."

Anson was finding words out of his temporary paralysis.

"What a splendid thing! A magnificent thing to have done! And I—"His words stammered away in confusion.

"Splendid!" agreed Dane. "An' I hope, when my turn comes to reciprocate, I'll be able to do it as cleanly an' without fuss. An' don't you worry, fella, about breaking before that charge. More experienced men than either of us have done it before now. Come ahead an' let's go look-see that crater."

THE country began to be broken by sharp edged masses of upended shale. Low

rounded hills like great boils that had failed to burst bulged from the

plain. Beyond was the black cone of the crater that in the long ago had

broken through the crust; a quite small one. In the farther distance were

other smooth cones. In that inhospitable soil the grass grew less thickly.

Going was easier.

A short grunt came from Dane. It indicated confirmation of a condition that he had expected.

"There'll be no lions in that crater," he told Anson.

Anson no longer felt like challenging these cryptic statements of Dane's; but he wanted to know the reason of so prophetic a conclusion.

Dane pointed his rifle muzzle at smudges here and there in the bare dust patches.

"Too many human footprints converging there."

"Well, that would about dispose of any fantastic theory of man-killing ogres, wouldn't it?"

Dane shrugged. "No man knows what fantastic thing can happen in Africa. Your native headman at the advance camp ought to have some ideas—if he'll talk."

And talk the headman did, volubly with much shouting and waving of arms, aided clamorously by his whole gang, glad to find a bwana who understood their talk direct without the headman's painful and inadequate interpretation of native thought into English.

It was an evil place, that crater, bewitched. Devils haunted it; fearsome monsters that rushed forth and rended men who came near when the moon was high. The advance camp at two miles distance was already too near. The line of the survey passed by the very foot of the smooth cone. It must be changed. It must circle far out of the way. Or all the working gangs would immediately desert.

Dane passed the meaning of the clamor on to Anson.

"They all insist on the yarn of Jubali ya Zimwi, the Hill of Ogres. I don't know what it means; but if I know my Africa there's something more there'n just imagination. Imagination doesn't smash men's limbs an' then sit up an' gloat over 'em all night. What is the local tribe around here? What do they say?" he asked the headman again.

The whole company screamed replies at him.

"They are Wa-Kashiri, great men and strong, monkey worshipers. They fight with us and drive us away. Nor will they give us food, and we dare not hunt. It is bad country."

Dane translated. "Perhaps," he suggested to Anson wisely, "it may pay you in time an' trouble an' indemnity to dead men's wives to give the place a wide berth."

But Anson stormed in righteous indignation. "A mile of road in this district averages five thousand dollars. And let me tell you that this construction company isn't going to cut any ten-mile detour to please a hundred African ghosts."

DANE nodded. He understood. "Yeah, that's business. Black men's lives are cheaper 'n detours. So I guess the nasty chore is up to us to rout the murderous thing out, whatever it is. An' soon. You notice they say these killings happen when the moon's high? Your last epidemic of slaughter was during the last moon. Four days o' moon now an' one killing already. An' I'm telling you it's not lions here. Something enormously powerful that doesn't eat its meat but kills for sport."

That reminder sobered Anson. Ogres he might well deny; but those mangled killings remained stark fact. "What do you make out of it all, you who read the jungle?" he asked.

Dane shrugged. "I don't know. But there's beginning to be a motive in sight. These Kashiri people don't want strangers around. That means one o' two things; either they're putting over some hokum—though I'm derned if I can figure out what fearful method they use. Or there's some local nocturnal monster. Don't ask me what; there's more things in heaven and Africa than are dreamed of in white man's philosophy; an' African-like, they consider it sacred high juju an' for that reason don't want any interference. So, after dark, I'm going to crawl out an' lay up somewhere near that crater and see what I can see."

"After dark?" The idea struck Anson as being the height of insanity. "Good Lord, do you take unnecessary risks just for the fun of it?"

Dane seriously shook his head.

"Never at all. But I've got the lay o' the land now, an' this one's necessary. If it's a hokum an' they see us out scouting by day they won't pull it. If it's some weird beast that kills by night it won't be out by day. An' until we find out what it is, it'll keep on killing another of your damfool Shenzies every now and then."

An idea came to Anson; an inspiration, it seemed to him, born of the desperate search for a tangible explanation.

"By golly! Remember what they said: These people were monkey worshipers. D'you think—all the circumstances would fit—not eating meat and so on—D'you think it's big apes? Gorillas or something?"

Dane shook his head. "Two reasons against that. The apes, all of them, need heavily wooded jungle; they couldn't stand the hot sun of this open plain country as well as you or I. And furthermore, no ape ravages around by night. No, this is something that murders by moonlight."

THE night came as fast as do all Central African nights. The sun threw gray shadows of low bulging hills and lone umbrella-topped acacias across the plain, dropped like an enormous hot rivet behind one of them; and there was the five-day moon already in place, bright enough to read by, except for leisurely silver clouds that idled across its face.

Dane slipped his rifle over his shoulder and stepped quietly out. The big Galla, as though he might have been his dark shadow, glided behind him. Anson, his teeth set, strove to keep pace and to emulate their silent stride.

The confused chatter of the camp faded away behind them. The outer night was uncomfortably silent. The usual noises of prowling animals were eerily absent around that ominous cone that rose black against the low stars. Anson, his mouth dry, wondered whether it was normal for men to walk into the dark unknown as coolly as did these two in front of him.

Dane had no special destination in mind, except that this thing, whether its object was to prey upon or merely to frighten the labor gang, would advance from the crater towards the camp. Somewhere along that line he would find a suitable place to lie in wait.

The moon, already high, printed hard black shadows of the cone and the low volcanic mounds against the shimmering radiance of the plain, a replica almost of those familiar telescopic photographs of its own face, and as still and aloof from anything human.

In the shadow amongst great lava bowlders that spread from the crater base, Dane found a place that would have to suffice.

"I'd rather be farther away," he accepted the situation. "But we've got to lay low out of that clear light." He settled his hips comfortably for a long wait, and Anson marveled that he could so casually fish a pipe from his pocket, deliberately disentangle it from odds and ends of string and cleaning rag and methodically fill it. But then Dane paused, sniffed at the direction of the wind, shook his head and put the pipe away again.

He sat silent. The Galla was so motionless that he merged into the gloom and disappeared; only a pale two feet of glow indicated his spear blade. Anson shifted from one uncomfortable position to another, trying desperately to be quiet but creating startling noises.

Other noises, too, began to be apparent. Far shufflings, rattlings of dislodged stones, grunts of low voices.

Dane grunted, too. "Hmh! So it's a man-made hokum. Some smart witch doctor putting something over on us. Well, that makes it a whole lot easier."

Anson breathed with relief. If this whole business were some trickery designated to frighten away his workmen, he had a cheerful confidence that Dane could find out all about it in short order.

But the next noise that came suddenly out of the night jarred the sense of security out of all of them and lifted chill hairs along Anson's spine.

It commenced with a hoarse bellowing, for all the world like a bull roarer whirled by a noisy boy; it boomed on into immense volume and subsided to an insane glug-glug chuckle.

Anson's breath caught at his throat and he could feel Dane stiffen. Then Dane grunted again.

"Hmh! I take it back. That isn't human. What make you of it, Mozumbu?"

"It came from within the hill," said the Galla. "Assuredly so speaks the devil of this place."

Dane slid a cartridge into his rifle chamber. "A devil with a voice that big calls for wariness. You all loaded, Anson? All we can do is sit tight and wait."

Long minutes passed that kept Anson's breath short and high in his chest. Crawling half hours; and then away to the left a tiny cascade of stones slid.

The Galla's knee joints cracked as he lifted himself to crouch. No other sound from him.

Soft swishings of bunch grass sounded nearer in the shadow, and again the rattle of a dislodged stone. Even Anson distinguished heavy footsteps. Dane was puzzled.

"Be damned if that isn't human," he muttered. "Wish he'd move out into the moonlight."

But the heavy steps plodded nearer. A big, powerful looking figure loomed in the shadows, coming directly at the three watchers. Dane rose to one knee. Then the figure stopped, stared out over the shimmering plain, shuffled on its feet for a minute or so, turned and plodded slowly back.

Dane completed his puzzled comment.

"And damned if he isn't doing sentry go. A patrol, that's what he is. Now, what the devil—" he broke off, turning over in his mind what might be the purpose of a guard or a watchman at the base of an ancient African crater.

The footsteps plodded slowly back. Dane strained his eyes to pick out details of the man in the gloom. He had no need. This time the man extended his beat. He tramped slowly nearer. A big, bulky fellow he was, armed with a spear as long as the Galla's, though with the less efficient short oval blade of Nilotic Africa. There was no further hope of concealment. Dane rose to his feet.

"Jambo," he< greeted. "We nani? Who are you?"

The man sprang back like a wild thing, eight feet in one great startled bound. Then, without a word of reply or challenge, he lifted his spear high and charged in on Dane.

And that showed him to be a savage, a crude back-jungle man, no wily spear fencer such as Dane knew amongst the Galla peoples. Dane knew many things about spear fighting, as well as about many kinds of fighting amongst hard men who hit first and asked questions afterwards.

He ducked low under the futile upraised blade, drove his shoulder into the fellow's midriff, gripped him around the buttocks and utilized the momentum of the charge to heave the man, big as he was, clear over his shoulder.

As the assailant thudded to the dust behind, Mozumbu was already leaping to straddle his back. Though there was no need. The breath had been thoroughly knocked from him.

Dane knelt quickly, before the man might recover and put up a fight, and with a piece of ever useful string from his pocket tied the man's thumbs together behind his back and then his big toes together. It was the most efficient and painless method he knew; quite unescapable as long as any one might sit by and watch against the usual methods of cutting bonds.

Dane rose, well pleased. "Maybe this so unfriendly lout will tell us what he guards so ferociously," he thought. But the man, when his breath had come back to him, proved to understand no Swahili; and neither of his captors knew anything of his back-jungle dialect.

Certain it was only that some great un-human thing bellowed fearsomely within the crater and that men patrolled guard round it. Whether to keep it in or to keep inquisitive strangers out remained mystery enough even for the African night.

Then the thing bellowed again. The sound welled over the crater lip, booming, gurgling, chuckling, entirely unlike anything Dane knew. He puzzled over it; till a quick resolve came to him.

"Sit tight over this fellow," he told Anson. "I'm going to climb up an' see if I can see anything over the edge. It's pretty steep, but I think I can make it." To the Galla be said in Swahili: "I leave the young bwana in your care."

He paused a moment to consider his rifle. That would be a stiff climb of some four hundred feet; he would have need of both hands. There are few things so unhandy as a gun in such circumstances; so apt to make unmistakable metallic noises—or so easily damaged; particularly during a scramble in the dark.

To leave his rifle went sore against the grain, but Dane shrugged. There were so many things one hated to do but had to. This that he was about to do now was one of them. He handed the gun to Anson. "And don't drop it so sand will foul the bolt," he growled. He looked to see that his Luger pistol was free in its holster, that the safety catch and slide ramp worked smoothly, and stepped softly out.

An immense weight of sudden responsibility descended upon Anson.

The Galla, of course, was a comfort; squatting on his hams, a dark imperturbable image of strength; an enormous comfort; but Anson, for all that, felt horribly alone.

The ghouls, homicidal ghosts, that he scouted so loudly in Dane's presence became very imminent horrors in the close African night, crouching, as he was, at the very foot of an ancient crater out of which some unknown thing bellowed fearsomely. He dreaded to hear it again. He strained his ears to catch the reassuring noises of Dane's progress. But never a sound came to him. Dane was taking no chances at all of betraying his presence to he did not know what.

Quite without noise, therefore, Dane gained the lip of the crater. Here the moon of course painted a bright silver line. Very carefully Dane edged between jagged bowlders till he could look down into the pit.

And he was woefully disappointed. He had expected, he hardly knew what. Lights, perhaps; signs of human occupancy; a juju house, maybe; or failing these, the thing itself.

But he looked down into an empty, steep sided pit. The slope beneath him was bathed in moonlight. His eyes followed the circular rim a couple of hundred yards across to the farther slope in black shadow. For all the rest he might have been spying into the bottomless void of Revelation out of which any appropriately monstrous shape might come.

Though to one side a great jagged darkness denoted a fissure. He knew there must be a fissure; either where the last lava had overflowed, or where rain water, collecting through the centuries, had found a crack and had inexorably cut its gorge of escape.

And now there seemed to be noises of a commotion from that black fissure. Voices, muffled shouts, confusion of many feet. Mystification engulfed Dane again. Those noises were human. Where and what, then, was the—the thing? That was all he could name it; the thing that bellowed inhumanly and frightfully killed men as no human could.

The vague commotion seemed to be receding down the black fissure. Now it sounded outside of the crater. Confused sounds came to Dane over the lip. He had better get down again, he thought. If men were on the outside, and if as ferocious as their fellow whom he had captured, his place would be down with his friends.

And then he saw something. Down on the moonlight plain. A figure that ran in a lumbering trot. A human sort of figure, it seemed to Dane; and then it came amazingly to him that at distance the figure was too large for a man. Four hundred feet below him in thin moonlight Dane could not make it out; or whether it ran crouching upon hind legs or upon all fours.

The creature stopped in its clumsy gallop to lift a shaggy head to the moon, and its bellowing gurgle boomed out into the night. A savage howl of freedom, it seemed to Dane. Then it lumbered on into the shadow and was lost.

INTO the shadow of the crater where Anson and the Galla waited, it went. They, from their lower vantage point, had seen nothing. But they heard the eerie howl and the shambling footsteps in the dark.

Their prisoner heard them, too, and, wretched man, inescapably bound as he was, terror gripped him. He chattered frantically to the Galla who understood no word and who was too occupied anyhow, peering out into the dark, crouching behind his rock, his spear blade low over its top.

The heavy footsteps pounded nearer; far heavier than the man's who had plodded sentry duty on that same path. A veritable trail it seemed to be that the three spies had stumbled upon in the dark. The creature followed it, lumbering nearer.

Presently its bulk loomed up through the shadow; a huge thing; taller than a man—much taller. Shapeless in the gloom; ponderous, it shambled ahead.

The horror of the thing lay in the darkness that shrouded it, a monstrous creature of the fog, the only knowledge of it being that it could kill.

Anson held Dane's rifle against his shoulder, his own across his knee. His heart pounded in his throat as the awful question came to him whether a rifle bullet could stop this bulk. Could stop it soon enough, that was to say, if not hit in exactly the right spot. And Anson knew suddenly that, shooting in the dark, he could not be sure of hitting it at all.

A noise caught the thing's attention. A clatter of stones up the crater side—Dane scrambling hurriedly to join his friends. The creature turned his head to listen, growling angrily in its throat. It swayed in uncertainty whether to go for that disturbance or to follow its path.

The prisoner decided it. He knew this thing; knew its hunting ferocity, its dreadful capability. Panic of the thing's nearness broke through his reason. A strangled shout broke from him, an incoherent babble of terror. He scrambled to his feet, hobbled as he was, wretched fool, and staggered bounding across the dark plain in a series of great, awkward kangaroo leaps.

The thing looked after the bounding figure, something new to its dull understanding. A long minute it took to make up its mind. Then it roared gustily and rushed after the fugitive.

Ponderously it lurched along. Strength might be its forte, but not speed. The man, unhampered, might have gotten away. But his handicap was hopeless. As it was, he made phenomenal speed in his fear. He passed beyond the crater shadow, and Anson and the Galla could distinguish him in the further moonlight, a grotesque travesty of motion, bounding, stumbling, getting up somehow and leaping agonizedly on.

The beast thing broke into the moonlight, too, shambling enormously after the doomed man.

Then Anson gasped incredulously. Monstrously half human it looked to be; though distance again rendered accurate identification impossible.

SHOUTS came from the distance. Men running round the base of the crater, but

far away. The kangaroo man yelled his quite hopeless call for help. He

stumbled and pitched to the ground again. The beast creature roared insanely

and hurled itself upon him.

The man's shrieks were horrible. The ponderous creature heaved him up and, like a cat flings a mouse, flung the body into the air; then roared delight and batted at the body with fast flailing paws before it could touch the ground. Anson could hear the heavy thuds of the blows from where he stood.

The creature repeated its monstrous game, flinging the corpse about like some hugely abnormal cat might play with a full grown kangaroo, gurgling insane pleasure, rearing up to meet the sprawling body as it fell, clutching at it in mid air, battering it to a boneless pulp.

A game it was. This thing killed for the mad sport of killing; it made no attempt to eat its kill.

The shouts of the men who ran from around the crater disturbed its play. Some fifty of them, all armed with spears and shields, were advancing slowly upon it. Carefully but resolutely. It crouched over its toy and howled fearsomely at them.

Anson jumped high in the air as a hand gripped him out of the dark.

"Down, you chump! Lay low! Don't stand there gaping! Lord knows who or what may spot you!"

It was Dane's voice. Dane, breathing hard and a good deal bruised; and very characteristically decisive.

"Down and lie quiet. We can't do anything for or against that mob. All we know is—judging from that poor devil we tied up—that they'll be against us. It's their hand. Let 'em play it."

The spearmen presented a solid front to the creature—their creature, it obviously was; the thing of their crater, fetish, juju wanga, or whatever it might be. They did not attack it. Warily they hemmed it round. It growled and ravened ferociously at them; but it seemed to understand the force of numbers. This procedure must have happened before. Slowly the men backed the creature away from its plaything. They surrounded it, yelling, shouting, encouraging one another. Like hounds baiting a bear, gradually they herded it away, back to its lair, den, whatever they had for it.

They disappeared out of the moonlight, round the curve of their crater.

"Well," said Dane into the heavy-breathing silence, "what did you see? What hellish thing is it? I was too far to make it out."

"Good God!" Anson found shuddering voice. "It's—it's an immense ape. Like that moving picture, Kong. Not that enormous, of course; but—"

"Impossible," snapped Dane. "And you, Mozumbu. What do you make of it?"

"That," said Mozumbu, "is, without any manner of doubt, the zimwi makali, the ferocious ogre of this crater."

Dane only grunted. "Hmh! I can believe one as easily as the other—by moonlight—in Africa. Come on, let's sneak away to camp and be damn glad we're out of it so easily."

IN the morning Dane was very grimly purposeful. "There's nothing else for it," he announced. "We've got to find out what that thing is. Kong apes and ogre devils may be credible at night, but this is daylight. I've got to get into that crater and look-see."

Anson stared at him as at an equally incredible phenomenon.

"But—Good Lord, man, that's a terrific brute. You saw what it can do to a man."

Dane nodded. "That's just it. I'm here to see that it doesn't do it to any more o' your labor crew—or to you or me. So is an elephant terrific; but a modern rifle is a whole lot of argument."

"But, dammit all, granting all that, there's its men folk to be reckoned with. There were a good two score of them, and you said yourself that they'd be hostile."

"Yeah, I guess so. But that was last night, too. By daylight two white men with rifles can hold two score savages."

This time Anson stared at the man without speech. Dane was taking it for granted, without question, that he would quite naturally accompany him on this foolhardy adventure. So much so that Dane turned away from him to busy himself with his preparations.

Anson had not the faintest inkling of the fact; but it was with a very shrewd deliberation that Dane was taking him for granted. Dane was there, as he had just indicated, not only to protect the black workmen from sudden death, but also to show their young white bwana how to protect them throughout the future building of that road which he wanted to see completed so that clattering automobiles and puttering tourist folk would use it and stay away from other parts of the country that he would like to see preserved as a wilderness paradise for those discriminating ones who would appreciate it.

And so it was that, there being no question about his readiness to share any danger that might come, Anson with set teeth trudged along with Dane and the Galla to go into an adventure that was not so foolhardy as deadly necessary.

Dane headed for where he knew the fissure in the crater side to be. As the farther plain opened out behind the cone, distant huts were distinguishable; the crudest kind of beehive huts in straggling groups here and there; wholesomely far away, it was noticeably evident. And where the fissure debouched into the plain through a confusion of smooth bowlders and a dry, sandy watercourse, a little knot of spearmen lounged.

"Guards," Dane commented. "Last night the place looked to be empty; but men don't stand guard over nothing. Big fellows, too. That poor devil of last night was no exception."

The guards bunched together at the appearance of the white men and stood with lowered heads, spears pointing; a burly, brutish looking herd; for all the world like cattle before a lion.

One of them spoke Swahili. Without preamble or asking what the strangers might want he said truculently: "The way is forbidden. No man passes within."

"And yet," said Dane looking at the well trodden ground, "many men pass this way."

The first speaker was confused by the white man's quick perception. He looked towards a particularly big fellow who stood scowling a little distance apart; but that one made no sign. The speaker repeated stubbornly:

"It is forbidden. It is fetish."

"Fetish," said Dane, "is the black man's affair in his own country. The white serikali does not interfere. But when a fetish slays the white man's servants in the night then it must be made to cease; for the servant is covered by his master's cloak and by the white man's honor."

What Dane was reiterating was the old principle of the white man's prestige which alone enabled the white man to hold Africa. The more primitive one finds people the world over, the more fixed is the idea that the servant is a part of the master's possessions and that a damage to a possession must be avenged by the owner.

The big scowling fellow who stood apart fired forth a stream of words, shooting out his thick red lips angrily.

Dane turned quickly to him.

"You. You understand what I said. Why don't you speak direct?"

The man only spat further words at the first man, who passed them on.

"He is a priest of the fetish. He speaks only through his 'mouth.'"

Dane's own mouth snapped tight. He understood perfectly the insolent inference that an important personage addressed an inferior only through an interpreter who acted as the "mouth" of the great one.

The situation had suddenly become tense. When an African becomes insolent there is no civilized finesse about his meaning. He implies crudely and simply that he can lick the white man and what is the white man going to do about it?

And there is only one thing that the white man can do. He must immediately demonstrate his superiority. Otherwise he may as well pack his goods and get out—if he may still get out alive. Conversely no man more quickly than the primitive African responds to demonstrated superiority and submits to it.

Matters stood on the precarious edge of a single hasty action. This was an arrogant people in an ugly mood; sufficiently far removed from the white man's influence to have to have the lesson of superiority thoroughly taught. Unless it should be taught, either by Dane, or later—after his killing—by a regiment of soldiers, that road would never be built.

There was a dozen of the burly guards. Dane felt sure that, armed with his magazine rifle, Anson to help, and the Galla an eager tempest of slaughter, he could fight his way through. But he always hesitated to resort to the ultimate argument of guns. He tried a bluff first.

Making a great show of his rifle, he walked forward. Anson stayed sturdily at his side.

"It is a pity," said Dane with an affectation of personal unconcern, "that so many men must die. Yet the white man's honor in defense of his servants must be upheld."

THE bluff worked; though in an unexpected way. The big fetish priest broke

suddenly into a fury of words, this time in direct Swahili, scornful,

challenging. The white men came, he shouted, with guns to fight against naked

spearmen. If the white man felt so big about his honor, let him uphold it,

man to man, spear to spear, leader against leader, armed, or naked man

against naked man. He jumped in the air; he postured; he ranted what was

really a superb challenge.

The seriousness of Dane's face changed to a wide smile of relief. He had met this kind of thing before; the old principle of trial by combat, champion against champion. It simplified things very satisfactorily.

"This is your rule?" he asked. "The leaders fight in order that much blood may be spared? A very good rule."

The fetish priest was an enormous fellow; bigger even than the Galla. A good six and a half feet he stood. For all that, Dane knew perfectly well that he could thoroughly trounce this savage; just as any half skilled fighter can in short order lay out a burly lout; and Dane stood a good six feet of hard and much experienced fighting man himself.

Yet the delicate question of prestige must never be lost sight of. A personal brawl was at no time dignified. And there was an insult to be repaid.

"It is a good rule," Dane repeated. "Yet as the fetish priest speaks to strangers only through his mouth, so I fight with minor priestlings only through this, my servant."

"Awah!"shouted the Galla in sudden joyful surprise. "Assanti, bwana, gofta karimu! Thank you, master. You are generous. This is indeed a favor!"

He slapped his thighs and leaped in the air. He twirled his spear like a drum major his staff. He breathed a thin, hissing noise through his teeth and minced forward on his toes.

The big fetish man screamed his rage. He would annihilate this servant. He would rip the bowels from him. He would impale him upon his spear like a grass monkey. And then the white man would have nobody behind whom to hide; he would have to fight.

Dane grinned his complete satisfaction. "It was to be hoped," he chuckled, "that the fool would resort to his spear instead of some outlandish weapon of which we might know nothing. Take him, then, with the spear, Mozumbu. But do not necessarily kill him. He is at least a courageous fool."

The man roared his rage and defiance in a great bull voice and advanced with his spear held high above his head—the only position known to the average savage for a downward stab, crude and ineffective.

The Galla held his weapon in both hands; but low, point slightly elevated. He made of it, in fact, a bayonet. He laughed as an instructor about to give a lesson.

The big fellow rushed and drove his blade down in a tremendous lunge. The Galla stepped a precise four feet to the right, moving only his right foot. The heavy shovel blade plunged past his shoulder a yard away, and his own long sword-edged blade lay cold across the savage's stomach.

"Thus does one rip bowels, oaf," he admonished. "Not from above like a tree' that falls."

The big man leaped back, an expression of ludicrous bewilderment on his heavy features. The Galla stood laughing at him. The big fellow rushed, roaring his rage again. The Galla's mid haft clicked against the stabbing blade, diverted it under his arm, and the steel shod point of his butt rested against the other's groin.

The big savage could no more understand this sort of spear play than could a brawny, cutlass slashing pirate understand the fine art of fence. But, like the cutlass swinger, he had his courage. He roared fury and rushed again, as clumsily as a bull and as stupidly. The Galla danced around him on springy feet, taunting him, scoring "points" on vulnerable portions of his anatomy.

"Upon the throat—so! A stroke to watch, great fool.—And now at thy spine with the point—Why turnest thou the back to me? So fells one an ox.—Thus again, at long arm, upon thy left breast—Tscha! I had not meant to prick thee so hard. Beware that one. A handbreadth deeper lies the heart.—Wah! Look out, fool! Almost didst thou impale thy clownish self."

It was a superb exhibition of spear play. But the Galla tired of it.

"To slay this fool were a child's game," he growled. "Not to slay him is a skillful and a tiresome business. I must make an end."

And as simply as he said it he did so. He stepped under the next rush, passed his spear under the big fellow's legs and, using it as a lever, whirled him off balance, snatched at an out-flung arm and sprawled him flat on his face.

And there he stood, his foot on the fellow's back, his spear point upon his spine, waiting like a gladiator for his master to turn thumbs down.

Dane motioned to Anson to pick up the spear that had flown from the doughty champion's hand. Himself, he was warily watching the man's followers. Resort to ordeal by personal combat was a fine thing; but angry savages, like other child minds, might not always accept the losing judgment.

However, the rest of the burly guards seemed to recognize their champion's defeat. They scowled and muttered, but made no further hostile motions—their eyes were fixed, like uncomprehending oxen, upon the Galla who still stood with the point of his spear delicately pressed against the fetish priest's skin at a point between two of his dorsal vertebras.

Dane deliberately passed through them, pushing them apart with his hands. Anson, with good example, pushed a yet wider path.

"So," said Dane. "It is now understood whose honor is strong. We give that fetish priest a present of his life. The fetish must now be shown that the white man is master and his servants are not to be slain; Come, Mozumbu. Let the fellow live. It was prettily done. There will be a gift of a good blanket."

They left sullen and bewildered men behind them and picked their way amongst the rocks of the little stream that during the rainy seasons of centuries had cut its outlet from the crater.

Dane led with ready rifle, wondering what monstrous thing from the lost centuries might have survived in this hole in the bowels of the earth, half expecting at any moment some pre-man period ape ancestor to charge down upon them.

THE way narrowed rapidly to a precipitous gully that zigzagged upwards into the very heart of the crater; upwards, of course, to the point from which the water overflowed; after that down to—what? Dane wondered and was the more cautious. The sun did not reach down into this deep cut. It was dim and cool; just cool enough, Anson felt, to let the fine hairs crawl up and down his spine.

At a particularly narrow point rocks had been piled with enormous human labor, leaving only a narrow opening.

"Ha! I begin to get the idea!" Even Dane whispered in that road into the unknown. "This is the door to the cage. A dozen husky men could hold an elephant in there. Whatever this fetish brute is, they let it out whenever they want it to do a horror killing to scare the neighborhood; an' we've seen that they know how to herd it back again. An' it's obviously some nocturnal beast; that's why the guard takes it so easy out there by daylight."

From "out there," muffled through the windings of the deep cut, came sounds of hubbub amongst the guard; shouts, angry words, argument. Dane frowned.

"I don't altogether like that. A chivalrous idea of personal combat is fine; but when savages as smart as these fellows are get to thinking it over, they're liable to decide that was just bad luck an' they'd like to try it over again, just like kids tossing a coin to decide a bet. Guess we'd better hurry up an' get a look at the layout in there an' then out an' plan a campaign."

The smooth tunnel sides began to be pitted with holes, blow-outs, little caves—the relics of great air bubbles that had formed as the ancient lava cooled. Dark holes like that might lead into all sorts of subterranean channels. Any weird beast might use them for its lair.

DANE spent no time inspecting them. All he looked at was the ground before

them and went on. He knew that even a leopard could not come and go from its

habitual den without leaving tracks that a practiced eye could read. That

some somnolent monster might be using one of those caverns for a temporary

lie-up was a hazard that he had to take. That hubbub on the outside worried

him more than he liked. Properly cowed natives ought to be silent; not

shouting in argument.

Yet Dane had to know what was in that crater; what monster it might be that emerged from the dark interior of the earth to raven by night. That knowledge was as necessary to him as a general's need to know the disposition of his enemy's forces in order to plan an effective campaign.

But, as a dangerously crafty enemy might hide his disposition, so the crater, when they reached it, revealed nothing. Sunlight slanted into the last bend of the dim passage. They stepped round it, and there they were, suddenly within the circular bowl of the crater.

And that was all! A silent, sunlit, ancient crater! No restless caged monster! No litter of bones or smashed fragments! No fetish house! No humans! Nothing! Not even any deep and mysterious tunnel leading into the bowels of the earth!

Dane was taken aback. Entirely nonplussed. He had expected, he did not know just what. If not actual life, rampant and charging, at least some signs of life; tracks, bones, something to denote the habitation of a nocturnal beast. But here was only a small, empty crater into which the sun shone.

And yet humans, many of them, were wont to use that passage upon occasion. Dane knew it with certainty. He stood at the edge of the quiet pit and inspected it cautiously. The upper lip, as he had already seen during his brief moonlight survey, dropped away in a steep, smooth wall. A couple of hundred feet below was a wide shelf of tumbled bowlders, a regular gallery that circled the whole inner surface, marking evidently the old normal level of the molten lava. Then a short craggy drop as the furnaces below had cooled and sucked the viscous material back to its subterranean boilers.

The bottom, where Dane had expected to find a deep tunnel that might harbor a prehistoric monster, was now filled level with a smooth detritus of eroded lava and sand. A few sparse thorn shrubs straggled on this floor; a few others found lodgement along the higher gallery. Nothing else. The whole inner pit was open to view. Silent; windless; empty; shut off from the outer world.

There was a stupendous wasted effort about this work of Nature in her ancient fury that caught at Anson's imagination.

"By golly!" he cried. "The Yale Bowl, no less! All empty and waiting for the season to open. Put some seats in, and there's a million dollars of building already saved. And"—he laughed loudly—"a ticket chopper's gate at the only entrance."

The Galla's great hand suddenly closed on his upper arm to shut off his laughter in a quick, "Ouch!" He looked to see Dane softly turning over the safety catch of his rifle. With a gulp of his breath he followed Dane's gaze.

There was something after all in this silent crater of the ogre! Dane's eyes were fixed on the dark opening of a big blow hole in the crater side. Something moved sluggishly within the dimness.

Staring across the bright sunlight, one could make nothing of it. A movement; that was all. Something was alive in there.

Dane stood ready for a bellowing charge. He was cool and confident. In open ground like that with a good light and fifty yards to go he could stop an elephant.

But the thing showed no desire to rush out and attack the intruders. Something had disturbed its rest—Anson's laugh, probably. It merely shifted its position in its lair and returned to slumber.

Human noises seemed to be no novelty; only disturbance. More noises floated in from the outside. Angry shouts and shrill whistles. Dane frowned at that reminder of insecurity out there.

The bulk within the cave shifted again, just as might an ill tempered sleeper awakened by noise without the window.

It heaved itself up from its recumbent position, a moving shadow amidst shadows, and so, on all fours, it seemed to stand as high as a horse.

Anson's breath came in a sharp hiss. What sort of a beast, Dane could not make out; the sunlight dazzled his eyes.

More shouts and whistles came winding up the tunnel. Clamor seemed to have a meaning for this beast. It reared up on its hind legs. Huge. Immensely higher than a horse; and it lurched a step closer to the mouth of the cave.

And then even Dane gasped. The view was still like trying to look across a bright court into a dim room. But the thing stood in sufficient illumination to distinguish a bulking shape that might answer to either of the descriptions given of it by last night's moonlight—a quite incredible giant of an ape or a no less incredible ogre.

A huge, half human bulk that stood eight feet high as it hunched its shaggy head forward to listen to the outside uproar.

Dane was fingering his rifle in hesitation whether to shoot or not when it grunted like an overgrown gorilla and retreated once more into the deeper shadows.

A fresh outburst of yelps and fierce shouts came from without. Dane swore fretfully.

"Dammit all, I don't like that racket out there. We'll have to go see what those fellows are up to. This what-is-it will keep. Nothing can ever escape out of here. Come on."

They reached no farther than the narrow passage of piled rocks—Anson's "ticket chopper" gate. Tall black forms clustered beyond and spears protruded through the opening. Those few were all that could be seen; but the clamor beyond them denoted many more than the dozen men whom they had left.

Dane's mouth clamped hard. "Hah! Reinforcements! An' that means trouble! Plenty of it! Sometimes with Africans it's a mistake to be lenient. They take it for weakness and try to go one better. We should have made an example of that fetish priest. He'll be vindictive."

Dane was still speaking when a whoop and a rush of black figures from behind swept him from his feet. From the caves and blow holes where they had cunningly hidden, a mob of yelling men swarmed.

THERE was no time to shoot and little chance to fight. African savages, when their courage has been worked up by rhetoric, can rush to combat in insensate fury; and while their madness lasts they can perform unhuman orgies of cruelty. It requires them either remorseless slaughter or some attention arresting feat quite beyond their own attainment to smash their unstable morale, which, when accomplished, reduces them just as suddenly to cowering, frightened children.

Of Anson and the Galla, Dane could see nothing. All he knew was that in that narrow passage he was the nucleus of a swarm of black bodies that clawed at him in a haze of hot sweat and yelled like so many devils turned loose to mob a new soul.

Dane had seen what was left of white men who had been captured by Africans in their hour of madness. He fought back with desperate fury. The tricks and foul blows that he knew, he used them all. But there were too many of the assailants, big strong fellows. He was engulfed under a wave of them. He felt his face shoved into the dust while half a dozen men knelt all over him. His hands and feet were quickly tied and a screaming gang of men heaved him up and carried him at a run up the zigzag passage.

A horror came over Dane as he conceived a thought of being thrown summarily to the fetish creature, bound hand and foot, as helpless as his last night's wretched prisoner had been.

But that did not seem to be the immediate plan. He was rushed across the crater, pitched into a blow hole cave, and before he could even hobble to his feet, great wooden bars clacked into place before the opening.

The whole thing had happened as fast as any misadventure that had ever come to Dane in Africa. And the situation was more ominous. Anson and the Galla, who had not been able to put up so venomous a fight as had Dane, were already in the cavern.

Dane lay panting from the fury of his struggle, half stunned, half strangled. As his senses began to come to him the first natural thought was weapons; though that thought died in its borning. Guns, pistols, knives, everything had been taken from them. These people were primitive enough, savagely ferocious; but every swift action of theirs, their organization, their whole system of imprisonment of their beast creature showed that they were a long way from being dull witted.

Dane chilled at the realization. When savages are intelligent and when their fury has drowned for the time being all thoughts of consequences, the thoughts of what to do with prisoners are born directly of their own dark devils.

The Galla rolled over to his side. "If Gofta will let me put teeth to his bonds, I may make shift to gnaw through and we may yet win free."

Dane had little hope of that. Those wooden bars were strong and beyond them stood tall spearmen. But he rolled to his stomach and let the Galla get to work. Nor was there much difficulty. The lashings had been hasty and a temporary measure at best. These captors knew as well as did Dane how good was their prison cell.

SOON all the three were free and on their feet. Dane shook himself and went

to peer through the bars. "Best see what we can see," he muttered, not very

hopefully, "an' maybe find out what they aim to do with us."

Plenty there was to see, and like a physical blow was the knowledge, when it came, of what these savages with their intelligence proposed to do.

The ogre creature had been thoroughly awakened by the uproar. It came shambling out of its cave into the full sunlight; and there for the first time the complete abhorrence of the thing could be realized.

A vast human thing it was. A shape of enormous hands and feet. It blinked little eyes out of a great vacant face and from its blubbery lips issued, not words, but a babble of glug-glug sounds. Its horror was magnified by the immense blackness of its bulk and the mop of crinkly hair that hung low over its cretinous face.

"Lord! An ogre it is! A homicidal giant!"

For the moment the shock of the knowledge that they had run such risk to gain, now that its realization stood starkly before them, overlaid consideration of their immediate plight.

"Phe-ew!" whispered Dane, peering through the wooden bars. "It's a freak, that's what it is. These people are an unusually big tribe as it is, and this thing has just outgrown them all; and like most freaks, it's half-witted. An ogre is right!"

The giant creature made no attempt to attack anybody. It just stood drooling and clucking to itself. The general populace stood away from it. Its immediate guards stood around; not guards so much as keepers of a tractable but potentially ferocious beast.

"It seems to be tame enough," said Anson. As yet no inkling had come to him of what might be in store.

Dane had no illusions. "Tame by daylight," he muttered to himself. "Idiots are often queerly affected by the moon. It's during moonlight that it goes raving murderous." he repeated his ominous conclusion in Swahili to the Galla.

A big spearman standing outside of the prison bars understood that. He guffawed hugely.

"Moonlight indeed! Wait, white men, till the moon looks upon the fetish this night."

Others took up the grim joke. They jumped up and down, slapping their buttocks. "Moonlight," they howled. "In the moonlight it will be seen who is master; whose honor is strong!"

So that was the proposal in store for the prisoners; stark and unmistakable. Savage enough to be inhumanly cruel were these people and intelligent enough to add refinement to their cruelty. As the Romans in the days of their degeneracy delighted to throw Christian slaves to lions, so these people were already looking forward to throwing white men to their ogre in his madness of the bright moon.

They danced up and down and shouted laughter at the prospect. They jeered details at the captives. It would be a spectacle; a huge joke on the superior white men.

Dane had no stomach to translate that joke to Anson. An added grimness was that Anson himself had named the natural amphitheater the Yale Bowl. Dane looked at the Galla, the Galla back at him, in tight-lipped silence.

MEN brought food to the ogre. It squatted on its hams in the shade of a rock

and ate enormously, slobbering clumsily. At intervals it moaned and pressed a

thick fingered hand to a bulge as big as a coconut above its paunch.

Where hope is non-existent the most far-fetched gleam of hope looms large. "Looks like it's got an enlarged spleen," Dane told Anson.

And that was all that he would tell him. He sat talking in low tones to the Galla, discussing probabilities and chances. And chances looked very slim.

At one time during the tortured afternoon the big fetish priest came and glowered through the bars; appraisingly, as a keeper of Christian martyrs might have done before a Roman holiday. He growled at his late conqueror:

"This time, thou trickster, no skill of spear play shall avail thee. Hand to hand, strength to strength, it shall be seen whose honor is strong."

He barked as a baboon laughs and went away.

Crawling hours later was another disturbance. Shouting men came carrying a limp something. Jeering, they let down the upper bars sufficiently to pitch their bundle over them into the prison cave.

It was Anson's labor crew headman. The wretched man was pallid gray with terror. He had come, he said, to see what delayed the white bwanas. Nowhere near the crater; only a little way from the camp; and he had been pounced upon by a band of these people and brought along.

"Yeah!" said Dane through his teeth. "White man's prestige for the time being has gone by the board. It'll take a miracle or a regiment of soldiers—afterwards—to win it back. An' I guess it'll have to be the regiment—This is Africa!"

More crawling hours passed. Suddenly the floor of the crater was in shadow. The sun had dropped behind the upper rim. In another hour it would drop behind the outer plain; and by then the moon would already be creeping over the opposite wall.

Men began to file into the crater; women with them, noisy, chattering. They climbed a narrow path and began to range themselves along the craggy gallery of old lava that encircled the pit, quarreling over the best places.

Anson's flippant reference to the Yale Bowl had been hideously prophetic. This thing was going to be a show.

Other men came in. Older men, decked out in necklaces of bones and all the gruesome trappings of African fetishism. They were ushered in with ceremony by the fetish priest and other young stalwarts of the cult. They took places where the more objectionable bowlders had been removed—the grandstand.

Dusk came. Drums began to mutter from the shadows.

The rock gallery merged into the encircling dimness. Black silhouetted forms moved like demons around the rim of a subterranean hell and snarled as they fought for position.

The moon lit a jagged line of silver along the crater's black rim; eerily beautiful; darkly ominous in the shufflings and mutterings of the devils within. In another minute the tip of its arc thrust up into view. With the fascination of a receding eclipse its brilliance ate away a rapidly decreasing melon rind slice out of the blackness of the pit side.

Dane watched it with a chill sinking of the last hope that had never been a hope at all. Presently the whole arena was flooded with cold white light.

The madness of moonlight commenced to grow upon the monster. It bellowed fearsomely in its cave. Its guards, three deep, ringed the opening with spears.

Things were ready for the show to commence.

THE central figure in the grandstand croaked orders. The fighting priest, now acting his turn as "mouth "for a greater than he, shouted them broadcast.

Men came to the prison cage; powerful fellows. They lowered the bars and came in with a rush, a horde of them. There was not a chance to fight. The prisoners were taken, four men to each, their arms twisted excruciatingly behind them, and led out into the open.

The chief made a harangue. It lost its effectiveness by having to be relayed by his speaker; but to the African mind the dignity of that proceeding made up for its second-handedness.

The demon gallery howled applause. The chief devil silenced them with a gesture. They did things quickly, these people. It was going to be a full program—four acts. Time was not to be wasted.

The "mouth" translated the schedule into Swahili for the benefit of the prisoners and for his own vindictive enjoyment.

"The little servant first, in order that the fetish may thoroughly awaken to the sport. The big servant next—snd let us see, thou great white man, how strong may be thy honor in thy servants' defense."

Those of the people who understood Swahili hooted and jeered and translated the taunt to others. The drums grumbled a roulade of guttural applause.

"And then," the speaker continued with the flourish of a showman announcing a special double feature, "the two white men together, in order that all men might see how the black man's fetish will prevail over the pair."

The gallery imps applauded and shouted boasts to one another of what they could personally do to the white men if their own great fetish were not so convenient for the purpose.

The chief croaked another order. The "mouth" passed it on. Then quickly, before Dane could grasp the procedure, the unfortunate headman was pitched forward onto his face where he lay moaning. The others were hustled back to the edge of the arena. The fetish's guards sprang aside, and the maniac thing shambled out into the moonlight. There it stood, monstrously gibbering.

A show indeed! Fit for a Nero or a Beelzebub. A dead pit of ancient hell's fires; the black shapes of demons who danced and howled amongst the shadows of the gallery; the white circle of smooth sand in the center for the performance.

The ogre bellowed its insane challenge to the moon and shuffled on its great flat feet towards the victim in the center, reaching its thick hands out in anticipation, drooling and chuckling. The man screeched terror and fled before its awful advance; madly, this way and that. The ogre laughed its idiot glee and lumbered after him.

BACK and forth and around the arena the grisly chase proceeded. Demoniac

howls and thunder bursts of drum applause cheered each sally. The man was the

fleeter. With frantic agility he dodged and ducked. But he tired first. The

strength and reserve force of the monster that roared and chuckled gleefully

on his trail was immense.

The wretched man dashed frantically to squeeze in behind the guards. With kicks and blows amid yells of delight he was hurled sprawling back into the ring.

Babbling in an insanity of fear himself, he fled away and tried to scramble up the side of the pit. Spear points from the gallery prodded at him and forced him down.

Clawing madly at the rock face, he slid down a sharp incline with a little avalanche of rubble, rasping his naked body cruelly. But what did that matter? For then the monster caught him. And then followed the same grisly performance that the three prisoners had witnessed with their own prisoner during the last night's moon. The thing hurled the body high in the air. Battered at it. Smashed it. Gurgling and chuckling in homicidal fury. Its ink-black shadow in the white moonlight gave a distorted duplication of a devil's orgy. The shadows in the gallery leaped and howled.

A splendid show! But better to come. The chief demon croaked. The "mouth" relayed. Guards ran in and herded the monstrous portent from its kill. The battered corpse was dragged to the edge of the arena and left lying. The monster roared and bellowed its rage at being driven from its plaything; but it slowly gave place. The tremendous exertion of its game was telling upon its lungs. It panted enormously, pressing its hand to its swollen diaphragm.

The drums thundered appreciation of the first act.

The prisoners were hustled to the center again. Next would be the Galla.

"Good Lord!" Dane was murmuring. "He hasn't a chance! He's a spear fighter. He knows nothing about bare hands. No African knows! Not a chance!"

Anson spoke through close bitten teeth. His voice was firm, though his outlook was hopeless.

"For that matter, what chance have even the two of us together? Or, do you think—I used to be something of boxer; and I've seen some big men lose to—" The words trailed away to nothing. The odds were too great even for two men together.

Dane scarcely heard Anson's flash of hope that died before it was born. He was biting on his lip with the anxiety of his own thoughts.

"I wonder if—Lord, I wish I knew! Perhaps if I could duck in and land all I have—Many's the time I've wished I knew more about medical science and anatomy. But never like now!"

The chief was making another harangue. Obviously, from the way his people shouted and cheered, it was about their greatness and their triumph over the white man's supremacy.

The Galla was the least perturbed of the three. Fighting and death was his fatalist creed. He spoke firmly.

"This, Gofta, seems to be the end. Many fights have we seen, thou and I. I had hoped that we might go together when the time came, in hot blood, spear and gun in hand. But the Ngai, the Lord of Ghosts, arranges otherwise. At least will I lay the flat of my hand once across the great beast's mouth; and then—I shall await thee, Gofta. We shall hunt together in the ghost country."

THE chief on the grandstand croaked his order. But before the "mouth" could

relay it, Dane strained forward between the men who pinned his arms. He was