RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

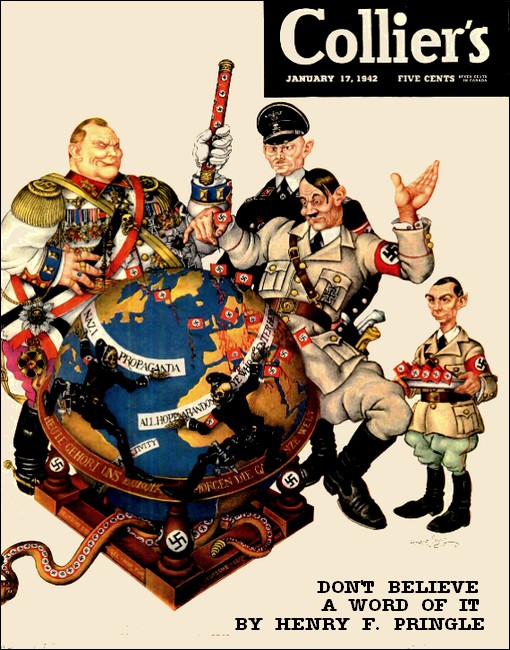

Collier's Weekly, January 17, 1942, with "A Stone in a Sling"

History repeats itself. David and Goliath again face each other, this time with the Suez Canal at stake.

HIS name was Dawud bin Yessieh, which meant David the son of Jesse, and it was as startling a thing for Miss Paige to realize as was everything else in the Sinai Peninsula. He had the soft-fringed eyes of all Bedouin Arabs before they grow up and the troubled business of living makes them hard. Long, curving lashes shielded them from the fierce sun and hid, when he willed, the imp of mischief in them.

Prudence Paige of the mission school at Qantara would stand and look at him.

"Dawud bin Yessieh, your ignorance shames a family as old and honorable as yours."

But Dawud had the unanswerable answer: "Our family are not mullahs who must read and write. We are keepers of the road."

So Prudence could only hold her breath and count many tens before the spirit that was in her might break loose. That was because she was young and pretty and she had an American diploma that said she knew everything about teaching. But she knew nothing about Bedouin character. Prudence was so unnecessarily pretty that all the stream of uniformed men who sweated through and about Qantara these days wondered how anybody so golden and blue-eyed and pink and white ever came to get herself tangled into a mission school in so hell-clinkered a hole as that.

And that was something that Prudence's keen American efficiency didn't very rightly understand itself. It had been a foreign land and therefore romantic; far away and therefore different from a rather uneventful small town in the American Bible Belt; closely linked with the Bible story and therefore thrilling; and how many avenues of safe escape are there, after all, for an alert-minded girl well raised in the Midwest convention?

Qantara was certainly different. It means "The Bridge," though there is no bridge there. It means really the place where the most ancient road in the world passes from Asia into Africa. Nowadays that most ancient of roads is cut by the most important of roads in the world, the waterway of the Suez Canal, and Qantara is the terminus where the Palestine Railway dumps its passengers out onto the staring desert to be ferried across the canal on a little hand-hauled barge and to connect with the Egyptian Railway on the other desert.

IN normal times the passengers, few and far between, are mostly Arabs. But

these days Qantara is a bedlam of uniformed men—lank Anzacs, bearded

Sikhs, thin-shanked Punjabis, hurrying, always hurrying, to strictly censored

objectives. Grim-faced men, they come and they go; very few can ever stop.

Lieutenant Danforth Menzies of the Melbourne detachment could stop because

his share of the business was perhaps as important as any. Left'nant Menzies,

he called himself, because he had inherited a British inhibition about the

pronunciation of names; and his men called him "Dingo," because those

Australians have thrown away all inhibitions about the sacredness of military

rank—and they seem to fight all the better for it.

Left'nant Menzies' job, with his men, was to patrol that bank of the empty desert as far down as Lake Timsah, and he had to keep his eyes as suspiciously wide open against everything that moved in the emptiness as ever any dingo on the sheep ranch where he worked back in the Melbourne hills. For the canal is a liquid tube that carries priceless freight more vulnerable to devious deviltry than the thread of pipeline that carries priceless oil from the Iraqi derricks.

The job, then, was a splendid and grateful reason to keep in close touch with a mission school that kept as close a touch as might be upon the pulse of a restless desert people.

"What ho! What's the day's best report from the Parent-Teachers Association, Miss Paige?"

In matters not military Dingo Menzies had enough of British inhibition to be meticulous about the Miss; and he would so continue, no matter how he felt, until the last supreme moment when he might formally express—well, he didn't know what he might dare to express, or when, or ever. For with his queer convention about names he had inherited another one about a man having some sort of a future to offer a girl before he should speak; and his future just now depended wholly upon his efficient, his faultless, conduct of his patrol. His first command. Dingo dared not make any mistakes. He stood, therefore, a lean and rangy and very worried young man and hid all his emotions under the racial pose of nonchalance.

"What's the best from the P.T.A.?"

And Prudence Paige threw out her hands in pretty despair at this tall soldier's wall of formality and admitted the tragedy of missions in Mohammedan countries.

"All of seven pupils today. Two suspicious parents to make sure we were not undermining their morals by proselytization. No news at all."

THAT was always the tone of their conversation—formally informal while

each ached with the deadly loneliness of teeming Qantara.

"Well, no news is the best. We don't want any change in the old status quo. Not a rumor for me to sleuth down, eh, and prove to the gilded staff that I'm a good man jolly well on the job?"

"Nothing. Only David bin Jesse drifted in like a rumor—that's almost news in school; and he drifted out again just as casually. His uncle from Libya, he said, was going to show him something his goats could eat. We can't hold them, you know."

"A new uncle, eh? Must check him up. No, nothing can hold a Bedouin. I'd like to win that little beggar's loyalty, though. Bright young ape, what? And the traditional sleuth of 'em all, old Sherlock, you remember, had a corps of bright lads keep an eye on doings."

Prudence shivered. "What sort of doings?"

"Oh I don't know. Jerry is dashed clever. What he'd like to do, of course, would be to blow up something, or sink a ship in the canal and block all traffic for weeks." Dingo broke off to stare from the mission's mud veranda at the dingy ribbon of water that meant so much to the world. The girl was close enough so that her shiver passed to him. "Good Lord! I hope nothing like that would happen in my section of patrol."

"It can't. It mustn't." Prudence closed her eyes to the hideous thought. "Or—could it?"

"I don't know. Every foot of it is patrolled; so they couldn't mine—takes time, and considerable bulk to transport; we'd spot it. We'd spot anything we can think of; but—" The officer gave nervous credit to the devilish ingenuity of the enemy for accomplishing the impossible. His shiver twisted his tight lips. "It would be ghastly! A thing like that could decide the whole war."

He blundered to tell the girl something: "You don't know what a thing like that would mean to me. Miss Paige."

She knew perfectly well; and she prompted him. Her eyes misty, her voice throaty, the whole nearness of her reached out to him to tell him that she knew and he just had to say it. It wracked her to shiver again that musty traditions, so far from home, could still so inhibit a girl.

"It would mean—I—" The wretched man struggled with his ingrained traditions of honor; and tradition, as always with the British, won. "It would mean I'd be court-martialed and probably broke." And British control of emotions let him laugh it off. "What I was saying was, a smart lad like that might pick up a worth-while tip of anything shaping up to happen, wandering about like he does."

"I don't believe"—Prudence bit little white teeth on a red lip almost as viciously as a mission schoolteacher dared—"anything worth while has happened in this deadly place ever since the flight into Egypt."

That was how old Qantara was and how changeless in its deadliness. It was old before history; at all events that was what Prudence Paige's school-books said.

Dawud bin Yessieh had a family tradition of his own that was as old, almost, as the road. He was ten—or maybe eight or perhaps twelve. Meticulous dates were not important in a family as timeless as his. His father. Yessieh bin Ibrahim, could sit for an hour and intone a list of begats that started with his patronymic Abraham and repeat all the hallowed names of Scripture.

So Dawud could argue confidently with his teacher: "This place is a fraud. It was never the road. It was just convenient for the Feranghi engineers to bring a railway to this place; so they told the people. 'Lo. this is the crossing.' But we know that they lied."

"Indeed?" said Prudence with the asperity of teachers who are told that their sacrosanct books are wrong. "You know a great deal for a boy who won't even learn to read."

The little irony was much too mild to touch an Arab. "All our family knows these things." said Dawud. "We are keepers of the road." And he gave again the unanswerable argument: "How should a road pass where there are no oases? Only a railroad that does not drink. The road passes from the wells of Birsheba to the well of El Khalassa—"

Dawud closed his eyes to recall the only items of importance in geography and recited the traditional list; "—till it comes to our well of Shalouf; and the crossing, the Qantara between the worlds, is there; and the road passes on to the wells of Salhiya in the land of Misr, and beyond that is not our family's care. But at every well are the people of my family, keepers of the road to care for the needs of wayfarers. They have always been there; they always will be there.. Even though the Feranghi have brought an unclean railroad to lure travelers from the true road."

PRUDENCE from shiny new America was awe-struck by the sheer piling up of

antiquity, by the unfolding of a history that ran so parallel to the Old

Testament as to demand almost reverence. She was unable to reprove her

problem pupil. She said only:

"I'm sure we all hope they will always be there." And she quoted Dingo, associating her hopes with his: "We don't want any change in the old status quo."

Dawud, of course, couldn't understand that, but he was smart young imp enough to know what he had gotten away with; so he added to it a quotation of his own from mature Arab wisdom:

"Women do not know much about anything. How then shall they teach us men of the desert anything that is useful?"

If mission schoolteachers could shake recalcitrant pupils. Prudence would have shaken him. As it was, she bit on her lip and managed once again, because Dingo thought the brat might be useful, to hold down the spirit that was in her. So Dawud got away with it again.

And Prudence, because she was a woman, instead of seeking the Reverend Dr. Paulson's gray-bearded advice, asked Dingo. "What," she said, "am I to do about the young ruffian?"

"What can you do, my dear—" Dingo almost said, my dear girl; but he caught himself in time to change it to Miss Paige. "There are no truant officers in the Sinai Peninsula; so you can't drag an unbroken Arab colt to the waters of learning, much less make him drink. But I still think it might be useful if you'd try to cultivate the young scamp. What I mean, that oasis of his. All the gossip of the desert filters through 'cm around the campfires. Things that our Intelligence would be glad to know."

So Dawud bin Yessieh played hooky as he willed and went with his new uncle to find sparse fodder for his goats.

How could a schoolteacher from America and a ranchman from Australia know that the uncle, of course, wasn't any uncle at all; that, since all good Mohammedans are brothers in Islam, Arab courtesy, imposed upon a boy more strictly than ever teacher imposed a moral precept, designated as uncle any stranger of the faith who sojourned within the tents?

THIS uncle was not even an Ismaelite Arab of the Sinai Peninsula. He was a

Tuareg Berber. Quite circumstantially, as he loftily explained, of the noble

Imajeghan class; so that there was no question about his accent or his blue

eyes. And he was a lithamia too—a veiled man. Throughout the

daylight hours he had to wear the blue litham that hid all of his face

except the eyes and the tip of his nose.

He spread his low camel's-hair tent in the shade of the oasis and explained himself by announcing that he was making the hadj to Mecca. That in itself was enough to bring him respect and it made his stay delightfully indefinite; devout men often spent the latter half of their lives making the hadj on foot from incredible distances, resting as they needed, going on as they willed.

Extraordinarily enough his opinions agreed with Dingo Menzies'. He didn't like any change of the old status quo.

"Consider now." Those pale eyes watered in the acrid smoke of the tiny camel-dung campfire. "This is an ill thing that the Feranghi have done. The road was here from the beginning of all time; and they have willfully brought their railroad to a place two leagues from here and have taken away the trade of this oasis. Kharabesh! May Allah do them an equal ill."

And patriarch Yessieh bin Ibrahim waggled his gray beard to say. "Sutchk' Allah. It is God's truth. This used to be a good oasis with many travelers."

And his grown sons, squatted in solemn circle, awoke to their inherent resentment of white man interference. "Bishmillah! May an ill come to it."

"And consider again." The stirrer of strife had another grievance: "The road stretched true and straight to the well of Salhiya, free for all men; and there the Feranghi have cut it with their accursed canal so that now poor men must pay a price to their ferry."

"An accursed thing that is," was the unanimous agreement.

"Aye and accursed all the ships for which it was built," growled the fanatic.

"May Allah's curse rest on it." Dawud put in his little bit.

Yet he was an accommodating man in his way, this one with the poisoned tongue, and his opinions agreed with Dingo Menzies' in yet another item. He cultivated young Dawud. In his wanderings he had discovered all sorts of little patches of sparse herbage: always near the canal of course, where the evaporation imparted a little moisture to the air. He was accommodating enough to volunteer to show them to Dawud for his goats.

Dawud was probably the worst pupil who ever put in a desultory appearance at any school, but he was quite one of the best goat herders. No good Mohammedan, of course, would ever enlist the aid of a dog to herd his flock; for the Prophet had cursed dogs along with swine as amongst the most unclean of beasts. Nor did Dawud need any dog. He used the hereditary implement: the sling.

Let a goat stray from the path, and Dawud would whirl the thing round his head and whizz a pebble with uncanny accuracy to fling a shower of sand into its face and head it back. He had to be accurate; for if his stone would unhappily hit the goat, it would knock it as suddenly dead as would a heavy caliber bullet. An Arab boy with a sling that fired a stone the size of an egg could do considerably more mischief than an American boy with a .22 rifle.

DAWUD would always pick up his pebbles again, as carefully as an archer his

arrows, and would drop them into his leather pouch; for pebbles, smooth and

nicely rounded, were as difficult to find as arrows in the sandy desert.

Berbers have been classed by some anthropologists as an offshoot of some early white race: and this Berber showed a sporting instinct that surely no Arab ever possessed.

"Look," he would say. "I will give you a piaster if you can hit me that mark."

And Dawud, challenged, would grumble, "That is seventy paces and a small mark." But he nearly always won the coin.

And so they would come over the low, sandy hills to the canal; and the goats would browse on sparse patches of scrubby grass, and man and boy would scoop away the white-hot surface sand to expose the cooler substratum so that they could sit down on the bank side; the boy thoroughly contented, because idle, the man glowering his hate at the great ships that crawled past at the scheduled six and a half miles per hour according to canal regulations.

THE man always had bits of paper that he would produce from under his

burnoose and he would study them as the ships passed and would growl

fanatical things over them.

"What arc those papers?" Dawud's curiosity finally had to know.

"These?" The man seemed to have forgotten that he had a sharp-eyed observer. "These," he laughed grimly, "arc incantations that, if time and place and my calculations would come together, would bring the completion of contentment to my soul."

"They look like the writings," Dawud said, "that the mission lady tries to teach me."

"I cannot read such Feranghi writings." the man growled quickly; and he turned to a subject more in keeping with a boy's innate deviltry. "How easily could you break some of those round windows on that ship?"

"At this distance," said Dawud confidently. "I could break any window that you would name. But they would blow their whistle and if the patrol would be near who then would get the blame?"

"Ah, the accursed patrol!" the Berber grated. "Another Feranghi interference with our peaceful desert."

And sure enough, there a unit of the incessant patrol presently appeared, a corporal's squad of men chugging and steaming along in a tortured open car, lurching over salty hard spots, shuddering to an almost stop in loose sand.

The Berber stood to his full height and scowled his fanatic hate at them.

He stood with his arms folded beneath his burnoose in that so-convenient position from which a man could snatch the Berber dagger from its sheath strapped to the forearm. But Dawud knew that he carried, instead of the dagger, a Feranghi pistol.

The men of the patrol laughed at the man's rage and nursed their car along. What conceivable harm could a man and a boy who herded goats do to the canal or its great ships?

Those were good days for Dawud, his friendship cultivated on the one side by a madman who gave him money for so simple a thing as hitting a mark with a sling, and on the other side by a girl, equally mad, who gave him candy just so he would stick around and talk about the somnolent doings of the desert.

Of the two, the girl was his favorite. For coins, after the man was satisfied that Dawud could expertly hit his mark, were no longer forthcoming, and American candy seemed to be limitless. Almost as much as candy, kind words went to win over the boy's heart. Kindness and a genuine interest that Prudence developed in the preternaturally alert, wayward son of the desert.

There was nothing kind about the man of the desert with the hard, blue, Berber eyes. There were times when he was frightening in his savage impatience over his paper incantations that would not coincide with the hoped for conditions of time and place.

PRUDENCE PAIGE'S impatience with conditions at that time and place that could

not coincide with her hopes was, on the other hand, a case that elicited the

sympathy of any interested observer.

Dawud said to her: "Look. Missy. An honorable man of the desert repays a gift with a gift. I will bring you, therefore, an incantation that, when the time and the place are right will confer the completion of contentment to your heart's desire."

Prudence stared at the boy. "Nobody knows my heart's desire," she told him archly, and her eyes went sadly from him to the sun-drenched emptiness. And then she received a surprise that has flabbergasted more than one confident young person in the Orient who thought she could keep a secret where only Oriental affairs are secret.

Dawud laughed. "All the mission servants know," he told her, "and hence all the bazaar knows that your heart's desire is that tall officer. I shall therefore steal for you such an incantation from my uncle."

Prudence could only gasp while she burned hotter than from any discreet sun bath on the flat mission-house roof. All the voice that finally came to her was: "But, Dawud, you mustn't steal."

Dawud's black eyes went sullen. "In his rages he has called me names. A small penalty is therefore due to satisfy my honor." And he ran away, leaving Prudence to simmer down to confused near normal, murmuring. "Will anybody ever understand them?"

When Dawud came again she was not visible, taking one of the many daily baths that helped to keep people alive in Qantara; and Dawud was in a hurry. So he left his crumpled gift with old Hurrumeeah the gatekeeper.

"My uncle awaits me as soon as he finished a small business in this place. I must go, for he is in a generous mood today. He promises many piasters if I make him good sport."

"For half a piaster." said Hurrumeeah, "I will myself place this paper in Missy's hands."

Dawud only cursed him with the appalling fluency of an Arab boy and ran off.

So old Hurrumeeah debuted whether he would deliver the paper at all, decided that Missy would find out about it anyhow, and so took his own time.

Prudence untwisted the thing with an amused tolerance of the inexplicable East. An incantation filched from a mad Arab. She looked at the thing and the amusement went out to open her eyes in puzzlement.

It was not an Arabic incantation at all. It was a shopkeeper's list of goods. Or, if not exactly a shopkeeper's, it was a précis of some big importer's consignment: Figures, quantities, details of stowage; neatly written in a language that—her breath suddenly made a dry little eek in her throat—she was able to recognize as German! And she could understand enough of it to make out some of its meaning.

It said, in effect: "S. S. Am. Trader. General munitions." It gave in round numbers kind and quantity to each hatch and, underlined, "Hatch number four, explosives, detonators, etc."

Natives who saw her run bareheaded in the sun said: "Another Feranghi has gone mad."

Dingo was, by the grace of God, there. He and a squad of men, coatless, drenched in sweat, were immersed under the hoods of two weatherbeaten cars. Strong words boomed metallically from them. Dingo backed out and lifted a grime-smeared, furious face to the flutter of Prudence's entry.

"We're in a mess of sabotage here, Miss Paige. Some swine has poured sand into the oil sump."

Prudence's hand flew to her lips. Through tight-pressed fingers she faltered the one word: "Look!"

Dingo scowled at the paper.

"What does it all mean?"

Prudence translated, and she returned the question to him: "What does it mean?"

"Good Lord!" Dingo wiped grime across his face. "Sounds like extracts from a bill of lading. American Trader reported through Suez this morning. In the canal now. Where'd you get this?"

"Dawud's Berber. But—?"

Prudence could only look her frightened question; but Dingo answered it:

"God knows. Their spies are everywhere. This'll be a deviltry of some sort. That ship will be coming into my section about now too."

Prudence clutched his arm. She pointed at the sabotaged patrol cars. "If none of them run, we can commandeer Dr. Paulson's car."

Dingo blinked at her. "Does it run?"

"Sometimes. It'll have to."

Dingo came out of his stunned trance of helplessness. He barked orders: "Fix whatever you can! Anything! Grind hell out of 'em so long as they'll run. Follow. Telephone the other end! Telephone Port Said air patrol!"

He ran from the shop. Prudence still clutched his arm.

"But what can he do?" The impossibility of everything mazed her. "What can just one spy do to a ship?"

"God knows. They're devils, and the devil must have shown them something. I'll tell you when I get back."

"You haven't got time," Prudence panted, "to argue me into staying back. This is my business as much as yours."

THE veiled man's little business that he had had to do while he waited for

Dawud in Qantara must have been quite satisfactorily accomplished, for his

eyes shone with a holy light as he strode with Dawud over the desert. He did

not have the shuffling lope of the born desert man: he walked heel and toe.

But he covered ground, unhampered by dawdling goats this time. This little

jaunt was strictly for sport. His furtive route staying in the hollows

between the drifted dunes, suggested that it was to be a mischievous

sport.

He brought Dawud, as always, to the canal, crisscrossing at the last through the gullies between the enormous fanned-out artificial hills of silt left by the incessant suction dredges. His fierce eyes narrowed in what must have been a laugh. He said:

"This day, time and place and my calculations come at last together. Sling me but a stone as I direct and five piasters shall be yours."

He sat himself down in the shelter of a hollow to wait for the exact moment of time.

A ship crawled past. The veiled man scowled his hate at it, as at all ships. He said:

"Not this one. The next—if that last incantation—which by the way, I seem to have lost, was correct. No matter, I know it by heart."

"Was it a good incantation?" Dawud was innocently interested.

"The very best of all incantations," the man said.

THE next ship was crawling on its way, three exact miles behind the tail of

its predecessor, which was the closest safe limit the canal's rules allowed.

A huge thing, deep-laden, it filled the channel. The man could make out its

flag. He ground out a curse, not of rage, of grim satisfaction.

"On that ship," he told Dawud, "is a man who has done me an ill. A good stone or two in the right place will give me the satisfaction of beholding his rage, the greater because he cannot reach me."

Dawud could understand the mad rage of impotence as well as any boy who has ever snowballed a hated and pompous citizen. But, "What of the patrol?" he asked.

"There will be no patrol." The man actually laughed. "Moreover," he said, "we do not break windows. We but fire a stone or two through certain ventilator holes."

"What are ventilator holes?"

"They are tubes—you see them there, flared out. They carry air to rooms below. I will point out the tube to my enemy's room."

"Oho!" Dawud began to rise to the deviltry of this. "Like throwing a stone through a window and running."

"Exactly." The man barked an excited laugh. "Five piasters if you hit me the right hole."

"That will be easy," said Dawud. The great ship's bow was abreast. "Shall I sling it now?"

"Wait. Not these first holes. That one near the other end." He pointed out a ventilator that rose from number-four hatch of the ship. "And look, I have here, by Allah's grace, a splendid stone for the purpose."

He produced from his waistband a smooth, round, grayish mass the size of a goose egg and he laughed outright over it. "This one will make a mess like Shaitan's very eblis in that room."

Dawud weighed it in his hand. "It is heavy. Moreover, it would be a pity to lose forever so perfect a stone. Let me rather—"

The man's humor exploded in a frenzy of rage:

"Machlool! Five piasters, you chattering little fool!"

Dawud scowled at him from under sulky brows. "Moreover again, I think I hear a car of the patrol coming."

The ship was stealing past. Men on its deck idly watched two figures on the bank. The man's voice broke in a choked scream:

"Fail me now, you argumentative little devil, and it will be five lashes. Succeed, and it will be ten piasters! Look, the ship is all but gone. Twenty piasters!"

Sulky under threats but spurred by promised fortune, Dawud fitted the heavy missile to the leather cup of his sling, began to whirl it to get its heft.

And there, over the farther sand dune panted the car that he had heard. Prudence's voice screamed from it:

"Harrm, Dawud! It is forbidden! Whatever it is, don't do it!"

The car slid out of sight in the hollow as if on a switchback.

Dawud's eyes flickered toward the interruption. His sling in its final whirl faltered just a fractional moment. The stone sped; but Dawud, for once, missed. It struck, not the hole, but the shaft of the ventilator that opened into number-four hold and it fell onto the top of the iron hatch cover.

And then a miracle happened before Dawud's eyes. The stone, all of its own accord, burst into flame and burned with a hell's fury!

The car staggered over the nearer rise. Dingo jumped from it before it stopped. He was tugging at his regulation army holster that would have driven any Western gunner to madness.

The veiled man was gibbering incoherent noises through his wet litham. He snatched that Feranghi pistol that he wore in place of the forearm dagger, fired.

Dingo's hand clutched at his right shoulder and he spun around and pitched on his face.

The veiled man, faceless behind his covering, stalked toward Dingo. Prudence, without any prudence at all, flung herself at him, clung to him with all the strength of strong, young arms around his.

"No!" she babbled. "Not that! Please God, don't let him do it!"

The man shouted frenzy at her: "Aus dem Weg, verfluchtes Weib!" He tore an arm free, back-swiped her across the face and knocked her reeling. "I don't kill him now—joost in case I don't make clear my getaway." He turned Dingo over with his foot. Dingo's lips spat sand, muttered indomitably;

"You dirty spy!"

The man possessed himself of Dingo's pistol. "Joost so your devil's woman don't schoot at me yet, I leaf no weapon." He started away at a shuffling run through the loose sand.

DAWUD ran to pick up Prudence. His dark eyes were big with fear and wetter

than any bad young son of the desert had any right to be. Prudence was

bleeding all down the side of her face. She staggered to Dingo.

"Never mind me, Dawud." Her agitation called for the impossible. "Stop that man! Go after him! Don't let him escape!"

Dawud gaped at her; scowled—but not at her. He muttered a grievance of his own: "A fool, he called me. Lashes he promised." He dug his bare toes to climb the shifting sand of the near dune.

Away up the canal there was a confusion of shouting on the ship where water sprayed silver in the sun and a thinning smoke. The veiled man was plowing along the gully between dunes; other gullies opened into it. Escape in such a place was easy.

Dawud, the son of Yessieh put stone to sling, whirled it, let go.

The veiled man fell forward on his face.

Dawud looked back for commendation. He saw, instead, Prudence's arms around Dingo and Dingo's head in her lap and Dingo's arms lifted to her neck and both of them smiling about something that was more important, for their fleeting moment, than anything else.

Dawud told himself with mature wisdom of the desert:

"True, it was a good incantation for Missy. But in the matter of the proper conventions, Feranghi women are completely without shame."