RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

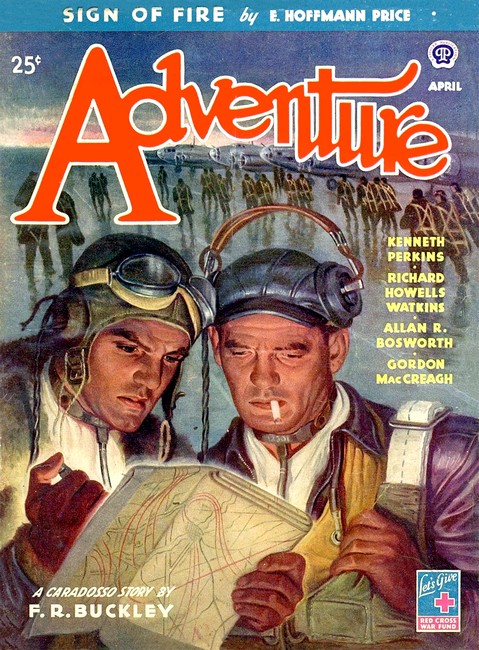

Adventure, April 1946, with "At Long Range"

THE civilian was unarmed. He wore blue coveralls. In a war area, he had no snappy uniform to designate an official authority to shoot at other men—or at anything. He was only the driver of the command car. He was a civilian because he was an "essential employee" of an aircraft company in Africa and he had been told off as driver because he knew the road where there was no road, between two of the far-apart mushroom airdromes where American planes, hurrying to the North African bases, had to come down for gas and service.

Now the car was hopelessly stalled in a wilderness of stiff bunch grass and acacia scrub. It was stalled because the gasoline tank was empty, Somebody who knew things which were supposed to be secret had shown some unsuspected black boy, who knew nothing, how to loosen the nut in the fifty-gallon spare gas drum. That kind of thing happened much too often in occupied enemy territory. An "accident" is always bad enough in the middle of African nowhere. This one was particularly bad just now because a big brute of a rhinoceros that weighed nearly as much as the car—as short-sighted as any pig, but with the compensating nose of a bird-dog—was deliberately quartering the ground down-wind, trying to locate the source of the infuriating scent of man.

The officers in the car didn't like to be told things by a mere civilian. But this one was telling them, with a priestly unction in his voice and a sardonic twist on a face as hard and burned as an acacia knot. He was telling them rules of conduct that even people of their high caste, who made the rules for all of Africa, would have to obey.

"You can't stop a rhino head on by blazing loose and wild at him with a 30.06 —not with the new light load."

The captain said, "But, good God! That brute is going to charge, isn't it?" ;

The civilian agreed heartily. "YoU bet. Soon as he's sure he's on the beam, he'll come straight outa hell." And he added critically, "That'n will weigh close to two ton, as I figure him."

The captain, entirely out of his familiar element, sent a hurried look around the shelterless expanse of rolling plain. He breathed "Good God!" again. "So what do we do now?"

THE big brute was trotting on short, oblique dashes across the hot scent on a vagrant wind. You could hear, almost feel, the reverberation of its feet on the sun-baked ground, coming nearer with each little questing rush. Two tons of destructive energy, as implacable and as stupid as some of those enemy platoons.

The civilian said, still critically, "They usually charge down blind, and if they miss everything they keep on going. But when an experienced old devil like this'n hunts you down, he's going to get that two-foot horn of his into something." And helpfully he added, "Of course, we could scatter like quail in the long grass. We'd have as good a chance as quail under a bird dog."

Again the captain called on God. He was in charge of the outfit and the rules of his caste made him responsible. "But there's fifty thousand dollars worth of irreplaceable radio equipment in the car! Quite irreplaceable! And it's got to get to Mtawa Camp by tonight." A futile rage at the all-too-prevalent sabotage overshadowed the more immediate danger. "How in hell do they find out these things?"

With a desperate and determined expression, the lieutenant was making sure that his rifle magazine was full. Sabotage wasn't the civilian's headache. He said to the lieutenant, "You'll only make him madder and show him where we are. If you can't abandon the car, there's only one chance left—and that's to hold your ground till he charges in to about thirty feet. Then he'll lower his head for the toss, and your mark is right over the tip of his horn. The brain shot. Sure and sudden."

The other lieutenant whispered on an indrawn breath, "Sure?"

The captain knew more about men than about African fauna. He cut in angrily, "See here, you! You're taking this too damned coolly. There's some other out, something else we can do?"

The civilian remained exasperatingly cool. "Ye-eh," he said softly. "There's just one other thing—if you can do it. If you can hit the tip of his horn, it'll jar him groggy—just like one on a tough guy's button—and he'll likely stagger off in any direction." He looked from one to the other of the officers.

The rhino broke the blank silence by suddenly squealing like an angry pig. It stood with its great hairy ears twitched forward, close enough for the men to see its little watery eyes blinking at the mass of the car, its prehensile nostrils flared out to the wind.

The civilian suddenly dropped his sport of officer-baiting. His sardonic eyes hardened to alertness, his voice to urgent authority.

"Give me it!"

Without ceremony he snatched the rifle from the first lieutenant, aimed quickly and fired.

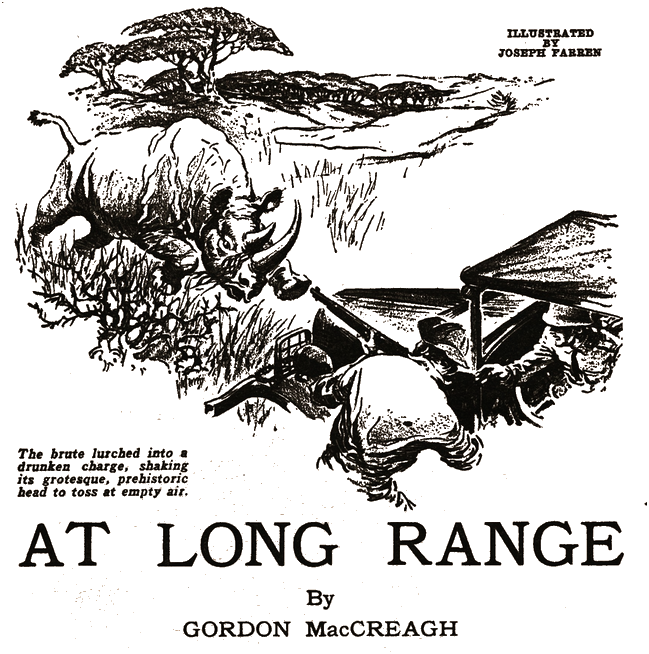

The whole bulk of the rhino staggered. Its front feet lifted from the ground to slew the body halfway around. It came down loose at the knees. The brute lurched into a drunken charge; it hurtled past the car like a derailed engine on a wavering course, shaking its grotesque, prehistoric head to toss at empty air. You could see great gray ticks clinging in the folds of its hide. The crackle and split of stunted acacia growth came back long after its aborted charge was lost to view.

The captain let go a long breath. He said, "If you could do that, why didn't you wait for that sure brain shot?"

The civilian answered him soberly, "Nobody can just 'do' that. That one was luck." And he suddenly showed an unexpected inside to his hard exterior. "Besides, its damn poor sport to smash a poor dumb beast on a sure thing. With modern weapons, if you don't get buck fever, they haven't a chance to get back at you."

The captain grunted, "Hmph!" and after a while, "Hmph!" again. "I think you will be hearing more about this."

THE civilian did hear more—from another captain. This captain said, "Mr. 'Tembo' Neale —we have been making some enquiries about you. We find that you've been over a lot of this territory before; that you know it inside out; that you speak the native dialect; that you got out of here because the local government had a warrant out against you for poaching ivory."

Tembo Neale remained woodenly noncommittal. "Since you found out so much, you found out, too, that they had no proof of anything."

"That might have been because you were very smart. What is the meaning of this 'Tembo' appellation?"

The sardonic curl came to Neale's lips. "I guess your enquiries about me were all from 'official' sources. The first native could have told you it means elephant," and he grinned. "I don't know why."

The assurance faded from the officer's voice. "You are a big game hunter, I believe."

"I was," Tembo corrected him. "I quit—because I got me a modern gun."

"Aa-ah! That rather unusual definition of yours about sport, eh? Because they couldn't hit back?" The officer was unexpectedly friendly. "Well, Mr. Tembo Neale, we believe that you are very smart."

Tembo remained wary.

"We believe that you could be a very useful man to us in this theater of operations—if you would cooperate with us rather than, er, stand off on an aggressive defensive."

"'Cooperate' makes me laugh," Tembo told the officer; and sourly, he did. "I wrote Washington for six months, telling every bureau I ever heard of that I'd been around here before; and then I told my draft board for six more months. So they went ahead and inducted me along with all the rest of mama's boys who'd never left their home towns. Till this commercial outfit thought they could put me to a little better use."

"The, er, confusions in Washington have somewhat hampered us too," the officer admitted. "But that is there and here is here. I propose to put you to better use still—to have you assigned to us for special duty. To—hunt for us."

Tembo's lip curled. "Thanks, and the hell with your job. The Quartermaster Corps has its meat hunters—renegade butchers and slaughterhouse men. I don't rate."

"Big game." The officer emphasized the first word.

"There's all too much big game been shot off by the butchers before the all-too-late conservation orders went through."

"Bigger than any you've hunted yet"— the officer pieced out his words—"and this game will be able to hit back."

Tembo stared at him from under frowning brows, sun-bleached against his burned skin. "I'll listen."

"Good. I must explain first—but you can talk to the natives so you must know it, of course. Well, there are these men—enemy—who've escaped our mopping up. Escaped because they know the country, some of them much better than you—colonists who've lived here for years. They know where to get arms. They know the language. They know how to handle natives. They have money. So every now and then a hidden gasoline dump catches fire; a plane makes a forced landing and its guards disappear; an emergency landing field is plowed across. So all right, we catch a few black men and shoot 'em. But we know damn well the black men didn't think of it or organize it."

The officer leaned forward earnestly. He stabbed a finger at Tembo's chest. "The biggest kind of game. They must be mopped up!"

Tembo's frowning stare screwed deeper, went through the officer and past him into unseen emptinesses of plain and rock and ravine. His breath hissed softly between his teeth.

"Ye-eh. You said it. Bigger than any I've ever hunted. They'd be able to hit back all right—plenty!... But I'm a civilian—and I've got a soft job now."

"You're an American."

Tembo's far stare went farther; beyond the hot rock and scrub, all the way across oceans. He began to nod and his frown began to twist around to a hard, wry grin.

"Ye-eh, an American. And like a lot of us who're still home, I don't know when I'm sitting pretty and well off."

SO it was that Tembo Neale, civilian, was squatted on a three-legged stool before a native chief's hut. With him was a lieutenant who knew nothing about natives but who knew all about the official rules of A.M.G. He was also without a uniform, however, for the African native has learned to look at all uniforms as a badge of the white-man pestilence that interferes with his own way of life.

The chief was over-fed and prosperous in a land where war had been not so long ago. He was hospitable. His pendulous-breasted woman brought sweet tedj beer and he talked for an hour of this and that. Till, the formalities satisfied, he asked, "And what does the frangi want in my village?"

Hospitable, but not respectful. It was customary to say Thilik Baba, My Great Father.

Tembo said, "I am looking for another frangi like myself. One who is generous with goods, such as this enameled beer cup, to people who do little jobs for him."

The chief's face took on a mask of stupidity. He said, "There is no such frangi in my poor village. As for this beer mug, it came in trade from a goat herder of my people who got it from a—" and he went into a circumstantial history of the implement. "Perhaps there is such a frangi in the big village on the other side of the mountain. Look, there you can see the path."

So Tembo took his lieutenant away. "We'd have to spend a month there and win his confidence against reprisals. These behind-the-line agents are doing a pretty thorough job of keeping the ex-subjects convinced this is only a temporary setback—that they're sure as hell coming and take over again. So we won't take that nice path the chief gave us. We'll follow it only as far as he can see us; and then we'll explore that likely-looking donga."

"What's a donga?" the lieutenant had to know.

"That erosion ravine. All kinds of varmint hide out in dongas. They're bad places to go snooping in. Come ahead."

But that donga drew only lesser game—a leopard which looked for a moment as though it might charge and then changed its mind and streaked away snarling and skittering ahead of a barrage of gravel up the ravine's steep side.

The young lieutenant whooped. "Golly! You could nave got it, couldn't you? At least, so I've been given to understand."

"It's always luck," Tembo told him, "if you make a fast shot like that. Besides, we're not collecting trophies. And it's bad medicine to holler like that, because somebody else might be collecting them. But by the same token, there's no man-beast bedding down in this gully. Are your legs holding out to draw another cover?—Well, tomorrow then. It'll be sundown by the time we get back to camp anyhow."

WHEN they got back to camp, expecting the kerosene tin of hot water that is the African bath, and supper, they found that their tent had been burned, their two pack-camels were gone and their three native boys had disappeared.

"Huh! I've been smelling it for a mile back and wondering." Tembo toed the warm ashes with his boot. "And there was me figuring not so long ago sabotage was none of my headache. A fast working son of a gun, this 'n." He scouted around in the dusk. "Well, he concluded, "he didn't kill 'em anyway. But I bet he scared 'em out of working for any frangi Amrikani in a hurry. And what's maybe worse, he's gotten him a nice little haul of new ammunish."

"Our ammunition! Will it fit his gun?"

"Brother," Tembo assured him, "those fellows have collected enough guns off of dead Yankees so they can take their choice—Hey, don't blow up those ashes to make a light and advertise for grief! And tuck up the old sore legs. We've got a sweaty three days ahead of us. Mtawa Camp for fresh supplies—and let 'em laugh at us for a couple o' tenderfeet."

Hours later in the night Tembo said, "Some day when we get time we'll have to go twist that fat chief's tail."

DAYS later, in a deep scrub- and euphorbia-filled, box-ended ravine, where the heat simmered as in a pot, Tembo's frowning eyes lit up. "This," he told his lieutenant with conviction, "is the place. Here's where our big game hides."

"How do you know? This damned thing is exactly like a hundred others we've been through, only bigger."

Tembo toed a hyena-gnawed bone. "A bullet broke that. And I've seen others. He's living off the fat of the land." He surveyed the steep gash in the rising esparpment. "Ye-eh. But how to hunt him out?"

"If you're sure he's here, don't we just hunt him? Tracks, or something? Can't you—er, well, you know."

Tembo shook his head. "This fellow knows his stuff. That's why he's right here. It's half a mile wide and a quarter deep and ten long, with all the cover in the world." Then suddenly, fiercely, "And I've been walking us around in it like any damn fool!"

AS though to prove it on the spot a z-zwitt of wind passed between them and shattered rock stung their short-clad bare knees. Tembo was already jumping, dragging the lieutenant with him, before the sound of the far shot came. They brought up together with an avalanche of gravel in a lower hollow full of boulders and thorn scrub. The shot was racketing its echoes back and forth across the steep cliffs above them. Tembo's lips were moving venomously, but the lieutenant couldn't hear him. He was holding a sweat-grimed handkerchief to a thorn gash across his forehead.

Tembo found a place from which to peer warily up ravine. He grumbled disgust at himself. "Just like any tenderfoot fool! So there's your answer. This'n can do some fancy shooting at long range. It's just sheer, dumb Yankee luck that he didn't collect one of us. Fool I am, but not fool enough to hope to trail up a guy like that in this cover. No, sir. Not any more'n I'd expect him to trail me."

"We've got to retrieve our rifles," the lieutenant said. "There they are, right out in the open."

"Let's rather guess," said Tembo grimly, "that our luck's good enough yet that he won't be able to make 'em out that far. And it's just our Yankee luck again that he's up the boxed-in end of this gully—so we can get out the lower end, the way we came in."

"It's damn good luck, too," the lieutenant whole-heartedly agreed. "This blasted hollow is one solid ant-nest!"

"Come nightfall," Tembo assured him, "we'll get our chance. We dassn't move while that kind of a shooter's got daylight. Tomorrow—if we get out—we'll scout around the upper rim and see what may be what. Sit tight and I'll tell you a story about a man I know who had a gorilla staked out and the ants got to it —and the man couldn't get near enough to turn the monk loose."

"Go ahead, and make it cheerful," the

lieutenant said. "I'm sweating enough to drown 'em off of me."

The morrow's scouting along the edges of the upper plateau showed the ravine to be just about what they had expected: a box canyon with precipitous sides and heavy cover, deep enough for a trickle of water to persist through the dry season—which again would mean ample game. A man could defend himself there indefinitely. It would take a company to mop up the place.

Tembo, in moody contemplation, kicked stray pebbles over the cliff edge. "The man knows his stuff, every move of it. So how to smoke him out?"

"Why not just that? Fire the woods?"

"We might up here, but it's too green down there. Let's scout some more before the sun drives us to shade along with the other more sensible critters.

More scouting brought another discovery—and more trouble. Bones!

Africa, of course, is paved with bones. But these bones, gnawed by hyena and jackal, had shreds of khaki cloth about them, and here and there an unmistakable American boot. And under the umbrella-topped acacias were all the parts of a plane.

"So," Tembo put the questiotn grimly to a pupil, "what do you read from all this?"

"Why—er, I suppose," said the lieutenant in a lowered voice, "there was a crash and— But why didn't they all die in the plane?"

"They didn't die in the plane," said Tembo slowly, "because it wasn't a crash. Look, the landing-gear isn't smashed. It was a forced landing. And they died because they were shot! Look here. And the plane was broken up and shoved under these trees so the scouting observers would spot nothing. Ye-eh, this man of ours—I mean, this certified devil—knows all his stuff."

"I suppose," the lieutenant said after a tight-throated silence, "this would be that DC-4 with a crew of eight that—disappeared."

He was still looking, big-eyed, at the scattered evidence of ruthlessness when Tembo gave a cracked crow of satisfaction. His nerves jerked him out of his contemplation.

"What beastly thing are you gloating over?"

Tembo was holding a grisly foot and shin bone that still held a native's brass anklet.

"This means that he had native help to round our boys up. It may mean that our boys put up a fight—let's hope. It may mean—and this is a more likely guess —that this clever devil of ours pulled the old precaution of liquidating his help so nobody would tell tales in court if he were ever caught. So that was his mistake and now we've got him."

"How d'you mean, 'got him'?"

Tembo grinned a very hard and tight grin. "You catch devils with deviltry. We'll take my guess and swear it's the truth. All we've got to do is find in what village he recruited his help."

SO Tembo and his lieutenant once again went through the formality of drinking nauseous beer with another native chief. Tembo knew how to do his stuff. He told the chief, "That air-machine that came down up there. Certain men of your village went with the foreign frangi to take prisoners. They did not come back."

"Since you know it," the chief admitted, "it was so. Mundu, the son of Dolo, went and Lutha went and N'goro and Diddi and Pwala and others."

Tembo unrolled his bundle of gruesome relics in his undershirt.

"This, then, is probably the leg of Mundu. His women will recognize his anklet. And here is Lutha and these must be Pwala and others. In order that he might not pay what was promised, that frangi killed them."

The chief stared like a dazed ox, slowly assimilating the thought.

"So what does your village do about such a matter?"

The chief still stared and made incoherent noises.

And then, since the African native responds easily to the stimulus of vengeance, Tembo gave the orders.

"You will gather all your spearmen and will be at this ravine to hunt, as for any other beast. Now, what places are there where a man-beast might climb out?"

"There are two places," said the chief, "where the rock baboons go down for water. A strong man might climb out by those ape roads."

"Good!" Tembo said. "Let the drums call your men in. Vengeance is overdue."

Then Tembo led his lieutenant up to the ravine's lip again. The lieutenant said, "But I understood you to say that both those monkey trails scale the cliffs on the other side. If they're climbable he could get away."

"Sure thing," said Tembo. "But if we watch at one trail, he might be taking the other. Prom this side of the ravine we can spot 'em both. And the sun is behind us."

"But what good does that do us—to watch him escape?"

Tembo's whole face stiffened to a fixed hardness, his head thrust forward alertly on hunched shoulders.

"He won't escape. You watch. It won't be long now. You can hear the spearmen yelling down ravine—and our devil will know what that means."

It was not long. The sun lit little ribbons of smooth-trodden trail that angled up between patches of scrub clinging to the cliff sides. Presently Tembo ejaculated, "Ha!" and pointed. "I told you he wouldn't stop to argue with natives yelling on that drum-beat! See him way down there? He's taking the other road. We'll have to move along half a mile. We got time; and this'll call for easy breathing and no heart-thumping."

Tembo squatted on the ravine lip opposite the other monkey path. "Near the top," he said. "That thread of open track across the rocks.... Dammit, shooting over empty space is always tricky—but the sun is just right."

"But, good Lord!" the lieutenant said. "You can't—I mean, at that distance! It's all of—"

"All of six hundred yards, I make it." Tembo hissed it through tight lips. "And if you know any prayers, say 'em. I may frighten him so he'll let go—ha! There he comes!"

Tembo stood up. "Never could shoot from any of those fancy military target positions. My experience has always been" —he held his breath while he fired—"snap shooting at game on the run."

With the last word the far figure moving across the rockface stood still. The lieutenant couldn't see its hands, but he could see the figure slowly begin to lean away from the rock—farther and farther, like a bow bent backwards, till, like an acrobat, it pushed itself from its foothold. It turned a first slow somersault, suddenly sprawled all arms and legs, then hurtled with increasing speed, bouncing horribly, brokenly from a ledge far out, and disappeared among tree-tops.

"Je-ee-eeze!" The lieutenant whistled. "I never thought anybody could do it!"

"Nobody can just 'do' it," Tembo said gravely. "That kind of shooting is always luck—Yankee luck." And after a long, somber frown into the ravine, came the tight grin.

"Pity we aren't collecting trophies. That devil will have horns."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.