RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

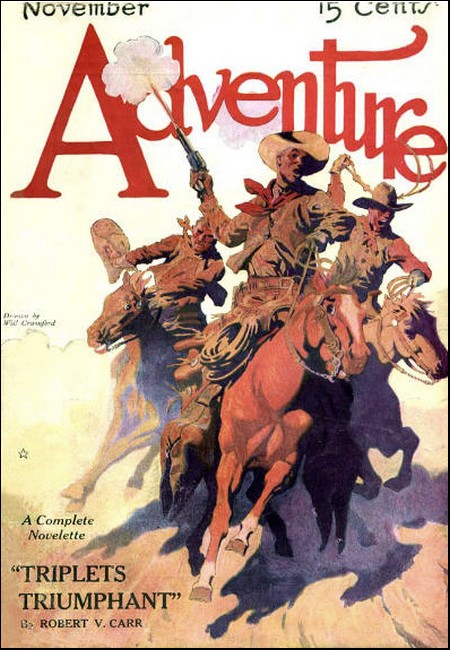

Adventure, November 1914, with "Featuring Morton St. Clair"

CHARLES JAMES STUART dangled his bare feet over the edge of his bed and whistled cheerfully through his teeth. He was without a job again.

The evening before had seen him hurled forth into an unsympathetic world by a champing and slavering real-estate operator, for no other reason than that he had conducted a profitable negotiation on an outlying property on the evidence of specifications and photographs furnished by the aforesaid operator himself. The prospective client had come into the office and a quick sale seemed imminent—only, it happened to have been the wrong photograph.

Only three weeks before that he had been demonstrating the advantages of a vacuum cleaner that "sold itself" on the strength of having "nothing to get out of order;" and had taken it to pieces to convince a Dutch hardware merchant as hard-headed as his own wares. The merchant had remained unconvinced, and Charles James had taken the instrument home in sections.

Before that again But it is sufficiently evident that his present condition of untrammeled freedom was the normal. Had been, in fact, ever since he had packed three shirts and a like number of socks—the extra one as a receptacle for a comb, a razor, and a toothbrush—into a grip and casually informed his uncle that he guessed he would go and invade the big city.

The big city lay at the other end of a sixty-dollar railway journey; but the uncle had merely grunted and insisted that he still clung to the belief that his nephew would arrive some day at years of discretion. The nephew had done this sort of thing before. He was one of those hereditary wanderers who would start for the weirdest places on a whim, and trust to blind luck to see him through.

"Guess so," he had replied unoffended. "I'll write—sometimes. So long!"

The invasion had not been productive of any considerable loot so far. Conditions in the big city were perplexingly different from those in the open places to which he had been accustomed, as, for instance, on his uncle's fruit ranch; and the swift-following successions of the normal were surely sufficient cause for worriment.

He was worrying now, after the manner of his kind. That is to say, he stretched and yawned prodigiously three times.

"Ah, does one good to get up when he feels like it," he mouthed from behind his hand, and proceeded to grope under the bed for his socks.

Then he got a stick and groped some more. Then he said,"——"and lit a match and applied it to the gas-jet.

Not that it was night-time—by no means. It was an early morning in Summer. But the young optimist had elected to live downtown, on a restricted and irregular income. As he himself had put it to the belligerent lady who was conducting him through the inner catacombs—

"That'll be two dollars for the room, I suppose, and fifty cents for the view."

He could take the whole view into his hands by simply leaning out of the window.

He improvised in minor cadences through his teeth some more, the while he filled a kettle of the ten-cent-store species and put a match to the little gas-ring.

Immediately the jet above, nominally a four-foot burner, but emitting only about half the specified quantity of light, sank to a quarter. The whistling stopped, and Charles James climbed on to a chair to prod at the burner with a pin.

He paused and reached out perilously with one naked foot to push open the door and listen to the sounds of an altercation in the dim hallway below.

"Tell him it's Mr. Stafford," came a voice, indistinct through the heavy gloom.

"It's all right, Mrs. Sloosh!" he yelled. (The lady's name was Schluessel.) "Come on up, Staff. Thirteen steps and turn, and then three more—and look out for brooms and stray buckets."

"Say," greeted his friend, "does it ever get dark here at night? — An' hoo's Wee Jeamie the morrn?"

"Wee Jeamie," who weighed one hundred and eighty pounds, trained, replied:

"Fit as a buck, and fired yesterday. You're just in time for coffee, Staff. Grope around outside the door and you'll find some rolls—that is, unless Rehoboam from next door has snaffled them again."

"Fired?" said Stafford tranquilly. "Good! Well, hurry up and dress. I've got a 'phone from Frankie Hanlon for pictures."

"Oh, staff of life!" crowed Jem. "Gr-reat man! Where's it for?"

"Don't know," replied the other. "Ow-w! Leggo, you gorilla! We'll have to find out at the office."

"'LO, BILL," greeted the agent. "Glad you came. Here it is; with the Motiograph people, in New Jersey. You meet at Twenty-ninth Street ferry—dollar-fifty and lunch. Here's a couple of cards; and hurry, so you get in on it. This is likely to last four or five days."

"Muchas gracias, Frankie. Come along, Jem."

"Say!" The agent stopped them as they were at the door. "Do either of you know anything about boxing? I got a call here for a picture-actor who can box."

"Why—" Stafford turned in a flash—"my friend Jem here; he's a half-way professional."

The agent appraised friend Jem with narrowed eyelids.

"Is that straight goods?" he asked suspiciously.

"Why, you know me, Frankie," avowed Stafford warmly. "And I'm telling you that Jem is the star of his club."

"Well, I suppose it's all right then," Hanlon conceded. "You take my card to the Vitascope studio in Brooklyn; and for Mike's sake don't let on that you've only suped before. They wanted an actor, but I simply can't find one to fill the bill."

"Five bones a day for you, Jem," chuckled Stafford in the street. "Ain't I a wiz? This is extra work, my boy, an' puts you where you can break right in to regular posing. Say, d'you know anything about boxing at all?"

The artless innocence of the inquiry was staggering.

"I've had gloves on before," admitted Jem in a dubious tone.

"Bluff 'em!" snapped the other. "Bluff 'em! All you have to do is to tell them the story of how you fought Volinsky in the West before he was known, an' you'll have 'em scared paralytic."

With which wise observation this shrewd snapper-up of opportunities boarded the car for the ferry.

"BREAK right in." Yes, the opportunity was there right enough; but Jem had no hallucinations about its facility. He knew that picture-acting required a combination of peculiar qualities, and that the fascinating picnic-life and steady salary were impelling half the legitimate actors in New York, to say nothing of quite two-thirds of the ordinary public, to try, more or less vaguely, to establish a footing.

The competition was enormous; but the young American-Scot smiled widest and whistled most out of tune when the difficulties were thickest. And his grin, as he now sat in the Brooklyn subway, was far more seraphic than at any time during his recent experiments in business.

Jem found the Director talking earnestly with the camera-man, and presented his card of introduction.

"Oh, from Hanlon?" flashed the former in his quick, jerky style. "What d'you think of him, Billy?"

"He has the appearance all right, Mr. Gresham," rumbled the camera-man, appraising Jem critically to his face with as little restraint as if he were a horse. "An' the build. An' I think he'll take well."

"That's what I think," agreed Gresham. "It remains to be seen whether he can act. Can you box? Well?"

Jem was unable to play the bluff-game like his city-bred friend, and was modestly explaining that he thought he could fill the bill when the Director cut him short with:

"Well, we can rely on Hanlon for that part of it. You'd better run along and make yourself known to the bunch; we'll be starting in a minute now."

The "bunch" received Jem with the courtesy that the family extends to "company." Company is welcome; but it is none the less not of the family circle; and, as the "extra" man is on a pinnacle above the dollar-fifty "supe," so are the members of the permanent stock on the sublime heights of Parnassus.

Meanwhile the camera-man and the Director looked after Jem with critical estimation. Mr. Gresham owed much of his success to an early recognition of the fact that the ultimate film owed as much to the camera-man as to himself, and, unlike many of the autocrats in his profession, worked with the latter accordingly.

The camera-man was an artist with an eye for scenes, and groups, and pictures, and a phenomenal judgment of actinic light. The Director was the actor, with a keen knowledge of the worth of gesture and dramatic effect. Together they formed a team that was making the Vitascope films the feature of the picture-houses; and incidentally, the Vitascope company the aim of every picture-actor in New York.

Had Jem known all these things, his tuneless whistle would perhaps have contained a further underlying motif of discord. Breaking in on the "Flying V" was an exceedingly difficult undertaking.

The camera-man spat a frayed toothpick from his lips and inserted a fresh one in its place.

"Goin' to try him out, Mr. Gresham?" he hazarded.

"Good gosh, no," replied the other, startled. "St. Clair will show off on him, and he'll get cold feet like all the others and quit."

"Don't size up to me like a frozen foot," grunted the camera-man.

"Maybe not; but I can't take any more chances. There's a hurry-call for this film from the office, and I've got to get it out. They've gone and published the release-date already. No, I can't take the risk. We know from Frankie Hanlon that he's a boxer—" the agent must have served him pretty well in the past—"and in the big scene we'll just tell him to stack up the best he knows, and just leave it to St. Clair to let it go about two hundred feet."

Which explains the fly in the directorial honey, and the reason of the unusual call on the agent.

THE scenario, which had been written up to feature Morton St. Clair, turned on the rivalry between two college students—rah-rah boys are always romantic—in which the girl, whose father was of the faculty, was attracted at first by the athletic prowess of the "other man;" while St. Clair, starring as the unostentatious hero, after being subjected to the usual slights at the hands of his rival, and the consequent imputation of cowardice, in spite of a noble rescue of the girl in a boating upset—establishing the element of sympathy—was finally taunted into competing in the annual boxing competition, in which he defeated his confident rival with a melodramatic flourish that thrilled the hearts of the five-centers. This constituted "punch," and the success of the film was assured.

The little difficulty which had held up the Director so far had been one of Morton St. Clair's affectations. The star was typical of his kind. He possessed a figure which a dexterous tailor could mold to heroic proportions. His features showed all the regular beauty and weakness of a Greek god; but contrary to the usual run of his confrères he was really a fine athlete.

The trouble was that he was leading by half a lap in a popularity contest running in a ladies' magazine, and the adulation from Maisie of the men's neckwear and Rosie of the ribbon-counter had been bad for his soul. He had fallen into posing all the time, and he was convinced that it was up to him to show his full worth whenever occasion arose.

The result had been physically disastrous to all the applicants for the "other man's" part, whose pugilistic skill the Director had hitherto rashly insisted on trying out in his determination to impart realism to the climactic scene. Hence the call on Frankie Hanlon for a new and unsuspicious victim.

"No," repeated the wary Director. "I can't take a chance on trying him out beforehand; and I'll have to warn the bunch not to put him wise."

Had Jem known of these inside details he would probably have fallen to whistling the bagpipe tunes of his ancestry. Breaking in on the "Flying V" was not only difficult, but hazardous.

MR. GRESHAM clapped his hands and a call of "Company!" went through the big studio. The loitering members gathered round and the Director read the synopsis over to them.

"Now then, people," he continued briskly, "we're going to rush a short indoor scene in first, and then we'll take advantage of the day and try to clear off all the outsides. I want you to help me on the jump."

"Who's in on the scene?" shrilled a voice.

The Director turned testily.

"My dear girl, don't be in such a hurry; I'm coming to that right now. We'll take scene three, 'Parlor in Professor Harvey's House.' That'll be Crandall, Professor, and Miss DeNeen, Marjorie—you know your make-up. St. Clair and Stuart, the two rivals; you'll want just a touch of sunburn, both of you—you'll hardly need any, Stuart. Hurry now and let's get down to business—quit mushing, you two."

The company laughed, and Miss DeNeen drew away indignantly from the star's side.

The scene showed the star calling on Marjorie and devouring her with his eyes; and the Director put them through a swift rehearsal.

"Now you come in, Davies—" this was to Jem—"and you jump up, Marjorie, and give all your attention to him—so! Show more pleasure, Marjorie! Get close to him; you're supposed to be an enthusiastic, romantic girl. No, that won't do. And Davies, you must look more as if you were used to it and it didn't excite you one bit."

Jem was desperately hiding his trepidation under a mask of exuberance; but it looked like good acting, only a wrong interpretation of the part. However, the Director's new instructions to look accustomed to the attentions of a perfect dream of a girl were much more difficult to carry out.

The girl herself was his salvation. She so positively radiated the cold impersonality of the professional, and added thereto such a strong impression that her real interest lay elsewhere, that Jem's exuberance was chilled to just the correct degree required by the Director.

"So!" he nodded, "That's more like. Now we'll run through it once again, and speed up a bit, all of you—so! Good! That's just about sixty feet. Now we'll pose it—lights!"

The big arc-lamps overhead flared out with a hiss and a splutter. One of the hands tilted forward the vapor-tubes at the side till the radiance literally flowed into them with that peculiar metallic tinkle which nobody can explain. Then he slowly eased them back to an upright position.

"All ready?" sang out the Director. "Camera!"

This was the signal to begin, and the Director called the action as each part came along, all highly strung and nervous.

"Five—ten—fifteen." The operator monotonously called off the seconds and calmly turned the crank at two steady revolutions to each.

"Fine!" acclaimed the Director. "That went good. Now then, pose for a still, Marjorie talking to Davies—St. Clair and Miss DeNeen, this is business now."

"How does he shape, Billy?" inquired the Director of his colleague with the camera, wiping his brow while a small strip of the film was being developed as a test piece. The scene had really been gone through as a trial of Jem's ability, though he had been mercifully unaware of it.

"Shapes good," grunted the other. "An' takes well."

JEM found the outside pictures very much easier. The open air was his home. Here he felt free of all restraint, and here he made love to the fair heroine with all the ardor of a young college student—anybody could make love to Helen DeNeen as if he meant it.

"What are you giggling at, Edna?" demanded a girl with the sauciest of retroussé noses and great innocent eyes.

"I was just thinking how funny it is," gurgled Edna. "How Helen has to make love to the extra in the pictures and give Morton the icy; and off scenes it's just the other way round—she's terribly stuck on him."

"Well, why not?" defended the other composedly. "Most of us love our lovely lead; he's considerable more of a man than most stars I've worked with. But I rather like this extra," she continued with a critical wrinkling of her freckles. "He's got a dare-devil sort of a face—and I like his big shoulders."

From which it may be gathered that the saucy one was a lady of fine discernment.

Scene Nine was the boating-rescue. The camera-man had previously hunted out a superb stretch of river, where the stream fell in a cataract, which, by clever film-faking, showing the upper half first and then the lower, could be made to convey an impression of the roaring falls of the Zambezi.

"Some picture, Mr. Gresham; eh?" he chuckled with a pardonable pride.

The Director was looking at the scene from under puckered eyebrows, swiftly reviewing its dramatic possibilities.

"Good gosh!" he muttered at length. "What a picture! What a picture we could make if we could have her rescued right within a few feet of those falls—just as the fierce current is taking her into its merciless grip!"

His words were unconsciously taking the dramatic expression of his thoughts.

"Mm-m. How could you fix it so they wouldn't go over? The scenario don't call for an ambulance scene."

"Don't know," frowned the Director. "Unless— We might stretch a cable across, under the water-level where it wouldn't be seen— Wonder if—"

He expressed his wonder to the two players directly concerned, and was not left in doubt for long.

"No, sirree!" announced St. Clair with decision. "Set me an easier one. I'm a professional actor; not a professional daredevil."

Jem saw his opportunity to make a good impression with the Director, and seized it with a promptness that would have done credit to the alert Stafford.

"I'd take a chance, Mr. Gresham," he volunteered. "Couldn't you fix it by showing Mr. St. Clair jumping in first and then dragging her out after; and if you let me take the part out there in the distance with the water splashing about, the difference wouldn't be recognized. If—if Miss De Neen would—"

The girl saw the challenge in his eyes, and responded pluckily.

"Yes, I will," she avowed. "If he does, I'm not afraid."

St. Clair wished he had not spoken so hastily. But it was too late to retract now.

He could not very well go back on the attitude he had adopted at the outset and thereby tacitly admit that he had been shamed into the part, and particularly by a stranger from without the family pale. All that was left to him was to try and carry it off with the lofty condescension of the champion who stands aside that others, less skilled, may compete; and to hate accordingly the interloper who had put him to humiliation.

The party sat down to one of those picnic lunches that add so much to the fascination of the picture-actor's life, while one of the scene-hands was whirled off in a big automobile to procure a stout hempen cable, somehow, somewhere—and in the shortest time possible.

A scene-hand, whose duty in outside pictures is to re-create Nature according to the Director's requirements, has to be a person of wits and a brazen front in order to meet the unforeseen exigencies of picture-making, as many an outlying farmer can testify.

"How do you propose to fix it, Mr. Gresham?" inquired one of the girls—she of the fuzzy hair and dimples, whose face is so familiar in a certain dental advertisement.

"Simple," replied the Director; he had already thought out all the details. "Just drive a good stake into each bank a little above the falls and tie the rope across a few inches under water. Say, Billy, you might see about the stakes; will you?

In a remarkably short space of time "Hoimie," the scene-hand, returned with a brand-new cart-rope which he had purchased at an exorbitant price from a "blank-blank Polackish truck-farmer."

While the preparations were being completed a picture was taken of the star heroically hurling his coat aside and jumping into the water, and another of him emerging with the dripping, unconscious girl. Both of which operations he performed with a very bad grace and a by no means heroic expression.

THE boat-scene followed immediately. As the girl rowed gracefully out, Jem could not help wishing that it might be his good fortune to save her from some real danger.

"Got her in the picture, Billy?" asked the Director. Then, "All right!" he yelled. "Upset her."

The girl performed the maneuver gracefully again and began floundering realistically in the water while the boat floated away down the current.

"Go ahead, Stuart! Don't flurry when you get to her; you're the cool, intrepid hero now."

The Director ran his fingers through his hair till he looked like a wet porcupine; his nervous temperament was beginning to show, as always during a picture.

"Where does he come into the picture, Billy?"

"'Bout half way down. 'T'll be just right."

The camera-man adroitly shot his toothpick to the other corner of his mouth like a shuttle and turned steadily, two to the second.

The Director was watching anxiously.

"So!" he yelled to Stuart. "Now you start bringing her in."

Jem took the girl under her arms, and, mindful of the admonition not to flurry, turned on his back and headed shoreward with a long easy stroke after the prescribed procedure of life-saving drill.

"Too tame!" shouted the Director. "You've got to look as if you were in real danger."

"Talking about danger," the camera-man interrupted evenly, looking like a hawk straight in front of him through his viewfinder, "ain't that boat sailin' over your rope a bit too easy, Mr. Gresham?"

And following swiftly on that, with the utmost composure and never a fractional variation in his speed— "Ain't that one o' your stakes, Herman, floatin' down?"

The scene-hand rushed to the spot where the stake had been. The keen-eyed cameraman was right. It was one of his stakes.

Just as a clothes-line will tighten in the rain and tear its pulley-fastenings from the pole in the back yard unless the Hausfrau has taken the precaution to loosen it, so the new rope had contracted with its immersion and softly pulled the stake out of the bank. The camera-man, with his vision trained to observe every possible encroachment into the field of his instrument, had been quick to notice these things out of the corner of his eye.

"Getting tired, Mr. Stuart?" the girl asked evenly from her comfortable position resting on his shoulder. "You don't have to hold my head up so high, you know."

"Not a bit," boasted Jem. "I could go on doing this for a week—with you."

While he was still chuckling at the indignant look on her face, the stake slid smoothly over, and the empty boat, gaining speed as it approached, seemed to hesitate a moment on the brink; then its nose dipped, and the stern went up like a whale diving, and it whirled down out of sight.

Later, the dramatic-witted Director added a breathless thrill to the film by making an insert-scene of a similar boat shooting over the falls and being smashed into splinters on the seething rocks below.

But the immediate realization of the horror that had come so suddenly upon him completely robbed the Director of bis voice, for the time being. Not a thing could be done to save the pair swimming on so easily, all unconscious of the tragedy below them. There was no other boat, and not even a line, supposing for an instant that one could have been thrown so far. Then the dire urgency of the case forced his voice back into his throat in a broken shriek.

"Swim!" he screamed. "For God's sake, swim! The rope's gone! My God! What can we do?"

JEM steadied himself with a swirling backstroke and raised himself out of the water. He understood the situation in an instant, and his quick mind at once grasped the best way to cope with it.

"Swim now, for all you're worth, girl," he muttered grimly. "There's going to be realism to this picture all right—No, not that way. We must head up-stream at a good angle to counteract the force of the current. Easy now, and long."

For an instant the girl hung limp on his arm, verging on panic. But the even voice beside her conveyed an indefinable impression of protection, and she pluckily steadied her nerves. For a few moments they struggled on together. Then Jem began to notice that the girl was slowly swerving away from his side.

"Keep it up," he encouraged. "Here, get ahold of this." He slipped his belt.

"Take it in your teeth so you can still use both hands."

He gripped the other end between his own teeth and set his course at the original angle again.

But they had slipped several yards downstream during the little digression, and the girl's strength, in spite of the assistance offered by the belt, was fast giving out. The heavy drag was beginning to tell on Jem. Gradually he was forced out of the diagonal course till he found himself headed straight for the bank.

He could see the white faces slipping by, ever swifter, and could hear horrified shrieks each time the girl was slapped by a wavelet and went under.

He turned desperately to stem the current once again; and then suddenly the drag on his neck ceased, and he shot forward. The exhausted girl had gone under, deep this time, and the belt had slipped from between her nerveless jaws.

She came up, floating limp, several yards farther down. Immediately Jem was after her with a driving overhand stroke, like a water-polo expert on the ball.

"My God! My God!" shrieked Mr. Gresham on the bank.

"My God! My God!" echoed the cameraman, the sweat standing out on his face in beads, but still turning the crank with mechanical rhythm.

"Hold on, girl!" gasped Jem, as he slipped a limp arm over his neck. "We'll make it yet."

But he knew his encouragement was futile; what had been just barely practicable before was now, with this loss of eight or ten yards, beyond the bounds of human possibility. He could already feel the suck of the powerful current.

Then a last desperate chance came to him.

There was a long knife-edge of rock which split the stream for several yards before the falls, and jutted, moss-grown and slimy, over the turmoil below. If he could only make it—and gain any sort of hold in that swirling current! A few feet farther and he would be directly above it.

"Swim, girl," he panted. "Just a little."

"I can't," she murmured. "I'm done."

Then in some inexplicable manner the diverging current whirled them right on to the rock. Jem's heart leaped with a great feeling of thankfulness, and with quick presence of mind he saw that his only hope would be to bestride the edge as he would a saddle. He swirled on to the stone with a jarring bump. The girl's weight swinging past almost wrenched his arms from their sockets and all but dragged him off his precarious leghold. Then slowly he recovered and pulled the inert body in to him.

The members of the company were shrieking hysterically in a horrified group on the bank right opposite, while Mr. Gresham shouted wild advice and vague encouragement.

Jem gathered the girl close and shuffled on to a more secure position. Then he grinned and whistled panting snatches of "Lochaber No More" through his teeth.

"What a picture! God, what a picture!" the camera-man was muttering with twitching face and glaring eyes, as he hopped on one foot behind the crank, which he had never ceased turning, through all the terrific excitement, at the regulation two revolutions per second. Of such stuff are the princes among movie-camera-men.

THE pair were rescued from their predicament by floating the recovered rope down to them and towing them out of danger with one of the automobiles. Jem was almost sorry as he helped the dream-girl ashore, for she had clung very close to him as they crouched overlooking the sudden death below.

"People," Mr. Gresham said weakly, when everybody was once more clothed and in his right mind, "the drinks are on me. I guess we'll make it a holiday for the rest of the day. Not only drinks; the eats are on me. I'll blow the whole bunch to dinner, if Miss DeNeen feels fit for it."

Miss DeNeen surely did. She was a fine, healthy girl, and beyond the unpleasantness subsequent to inhaling a large quantity of water, felt very little the worse for her adventure.

Everybody was satisfied with the arrangement except the star—for had not somebody else monopolized the whole limelight to his own complete eclipse? He excused himself ungraciously and sought the seclusion of his home, to brood alone over his wrongs.

The camera-man insisted on getting into the same car with Jem, and put him to inhuman discomfort all the way home with outbursts of:

"Man, but that was a great picture you made! Gorgeous! The sensation of the season!"

"Oh, cut it!" begged Jem. "You've said that just seven times now."

"Yes, yes, I know; but it was fine! Great! I'm goin' home an' pray that the film turns out good — there's no reason why it shouldn't. I stopped her down quite some, and turned like a clock. Man, if you can box like you can swim we'll have some film, let me tell you; some film!"

"Well, I can't," said Jem shortly.

"Well now "

A shade crossed the camera-man's face, and he opened his mouth to say something; then he pressed his lips tightly together and looked away, drumming on his beloved box with his fingers.

DURING the ensuing days Jem found himself regarded almost as a distant relative of the family, by all except the star and the girl. The former looked at him poisonously, and it became evident to the discerning that he was possessing his soul in unholy patience. The girl, after thanking him simply for what she called his splendid pluck on her behalf, avoided him strangely. But then, it was noticed that no longer did the Director have to call her and St. Clair to attention when he got to talking business.

In the posing, too, Jem got very little satisfaction, for the scenario now called for the girl to begin showing a preference for the hero after his supposedly noble rescue of her. With the obtuseness of the man of the open places, to whom the ways of women are enigma, Jem pondered ruefully over the irony of these things.

"What are you giggling about now,Edna?" the retroussé girl was constrained to ask.

The observant little philosopher bubbled over.

"Isn't it funny," she rippled, "how things have turned right around? When Helen had to make the goo-goo at Mr. Stuart in the picture, you couldn't separate her from Morton with a derrick; and now that she has to play up to Morton and put Mr. Stuart in cold storage, off scenes you can see her fairly eating him up with her eyes—you watch her when she thinks no one is looking; and if you go near Morton you can hear him cussing horribly all the time."

The saucy one was less observant and more skeptical of the other's deductions, and therefore dying to delve deeper for herself. For what interests a girl more than the meddlings of Cupid—miscalled the beneficent—with the peace of mind of his victims?

Later she found an opportunity to vivisect St. Clair.

"What's the matter with you these days, Morton? Glooms come to live with you?"

Then she added quizzically, "Has Mr. Stuart put your nose out of joint?"

The star snarled at her, and all that he vouchsafed was: "I'll put his out of joint! Just wait; that's all."

Which was not exactly enlightening as to the doings of the malicious god. All that was clear was that the star was not prepossessed in the extra man's favor. But that might well have been because the latter had outshone him, which was quite sufficient with a character of such inflated egoism to account for the ominous reference to the coming slaughter-house scene, which the wily Director was reserving to the very last—when there would be no further necessity for the extra's services.

This was without doubt a cold-blooded plot on the part of the Director; but he was as much an artist as the camera-man, and his whole being was concentrated on the success of his picture.

Concerning all of which Jem was blissfully unconscious as they hurried, urged by insistent demands over the telephone from the office. It was hard work now, and the observant little lady with the sense of humor had not even time to note the perfectly glacial professional impersonality which the heroine put into her love-scenes with St. Clair.

At last there remained only the big scene, the climax in the college gymnasium, for which quite a crowd of dollar-fifties had been requisitioned to impersonate enthusiastic students; among whom Jem was delightedly surprised to see his friend Stafford.

"Hello, Wee Jeamie," greeted the irrepressible one. "An' hoo's a' wi' ye the morrn? Broken in and stuck. Eh? Gee, I hadda hold Frankie up with a gun to let me in on this; but I just hadda see you established."

"Established like—! The foregoing has been play; this is where the real try-out comes; and judging by the line of talk I've heard, he's a man-eater. Frankie'll kill you for steering him up against me if I don't make good in this sparring-match, and he'll never give you another job."

Stafford's face clouded.

"Gee, that'll be savage," he said nervously. "I can't afford to lose the good old stand-by. Jem, you gotta make good! Stamp on'm! Bite him in the leg— Say, there's the boss hollerin' for you."

Mr. Gresham took Jem and the star to one side.

"Now, boys," he exhorted them, "this is the big scene of the play, and I want you to make it realistic. I don't want any of the piking stuff you see in the usual run of pictures, where the most terrific blow stops a foot away and then gently pushes the other man in the face; and I don't want the ferocious swing that misses by inches and knocks him down by the wind of it. This has got to be a real boxing contest, quick and snappy. That's why I haven't rehearsed it over." Guileful man! "Now you'll need no make-up in this, only costumes; hurry up and change."

He held St. Clair back by the arm.

"Now, look here, Morton," he instructed confidentially, "I want you to let this go about two hundred feet. We all know that you can put him to sleep whenever you want to, but just hold him off till I give you the signal—then you can let yourself go and score a dramatic knock-out."

The Director was surely a cold-blooded artist; and a hint of the existing circumstances, which everybody except Jem seemed to be aware of, began to be whispered among the "supes," who settled themselves enthusiastically to enjoy what promised to be quite an exciting little program.

Jem hurried out of his dressing-box with a towel draped professionally over his shoulders, and was surprised to find Miss DeNeen loitering at the head of the passageway, obviously waiting for him.

"Oh, Mr. Stuart!" she began nervously. "Listen. I—I wanted to tell you—I was hoping some of the men would have warned you, but—"

"Warned me about what?" asked Jem, astonished both at her presence and her manner.

"Oh, about Morton," she continued with a flash of indignation. "You know Mr. Gresham wants this to be realistic—and Morton knocked out all the others who came, and they went right home again—that's why Mr. Gresham wouldn't rehearse you, and—and Morton doesn't like you, and—I think Mr. Gresham should have told you about it."

She concluded with a rather incoherent little rush.

Jem's eyes narrowed to grim slits as he whistled an atrocious bar of discords.

"Hm-m! So that's the whole mystery?" he muttered. "How good is this Morton man?"

"I don't know, but he's simply awfully good," the girl informed him with lucid inaccuracy.

"Hm-m! Thank you very much, Miss DeNeen. Now that I know, I fancy I shall be able to keep away from him for two hundred feet."

In the studio Jem became aware of Stafford making frightful faces at him to attract his attention, but he had no time to make inquiries. The Director had him by the arm.

"Now don't forget, Stuart, I want realism. You go in and do the best you can; St. Clair will look after himself."

Jem grunted—

"D'you mean I've got to fight, really?"

"Sure-ly. Remember you're fighting for the girl." Jim had a dim impression that there was more truth in this than even the Director knew. "Now, quick and snappy, Morton. I don't like the expression on your face; remember you're the cool and confident hero now; revenge isn't in your system."

The admonition was necessary. St. Clair was looking like a victorious gladiator waiting for the thumbs to go down.

"NOW then! All ready?—Camera!"

"The best you can"—Jem had learned early in life that the best defense lay in attack. He stepped in like light, feinted, and swung both hands—and was amazed to find them both land clean and heavy. The star was evidently unprepared for such suddenness. He snarled and crouched, planning vengeance.

Jem remembered the advice of a battered old professional, "When the other man thinks, you hit." He leaped in and hit, straight with the left to the face, and followed with a heavy right-left to the body. Again he was astonished to find all three of bis blows land without opposition.

St. Clair's head had snapped back, and a thin smear of red tinged his upper lip.

Jem stepped back and circled, wondering whether this was a "stall," and if so, admiring the sacrifice that the other was prepared to make for the sake of the picture. He was thinking this time; and St. Clair rushed in, swinging furiously, and bore him back to the ropes.

Jem recovered his balance with the rope touching his back, and then stood toe to toe and slugged. The other man was taller and heavier, but this kind of fighting suited Jem, and he found himself coming in with heavy, short smashes that drew sharp grunts from his opponent. Slowly the rope left his back, and he began to win to the center of the ring. Then a flush hit landed on his cheek and he went down.

The "supes" were howling in their seats and jostling one another to get a better view; behaving, in fact, just as interested partisans should do.

"Fine!" shouted Mr. Gresham. "Not too hard yet, St. Clair."

The camera-man hopped on both feet with his eyes blazing, and ate up a whole bunch of toothpicks while he counted, "Eighty-five—ninety—ninety-five," with monotonous regularity.

Jem was grinning now. His breath hissed through his teeth with a vague rhythm. He was beginning to realize that he could make quite a showing.

St. Clair rushed in again to take advantage of his knock-down, entirely oblivious of the Director's instructions about prolonging the film. His despised rival had hit him about almost as he pleased—of course he had been taken by surprise—and he was now bent on savage retaliation.

No ropes against Jem's back this time! He ducked swiftly under the swinging arms, and began the heavy rip! bang! thud! of the natural in-fighter. Presently his opponent stepped back to gasp for breath.

It was just the proper distance. Smash! Full over his left ear. Smash! Again. St. Clair reeled away with a pained, bewildered look on his face.

Some one laughed. Some one who knew and understood. Vaguely St. Clair comprehended that the laugh was against him; and the realization acted on him like strong brandy. Ridicule! Of him!

He bit his teeth together and rushed in, to be met with a heavy crash on the side of the neck which sent him to the boards.

"Oh, splendid! Magnificent indeed!" shouted the Director. He was getting a gorgeous film. "We'll call that, 'Saved by the Bell.' "

The star was assisted dazedly to his feet, and the Director purred over him.

"That's just glorious, my boy! We're getting the picture of the season. Now then, when I give you the signal you can go in and finish it—as soon as you're ready."

In his excitement the Director's mind still clung to his preestablished estimate of the star's prowess.

"I'm ready," grated St. Clair thickly through his choking rage; and rushed in to the contest again, raving, berserk.

Jem weathered the storm, ducking, slipping, and grinning all over; and St. Clair snarled around him with an expression not at all like the prescribed hero of the nickelodeons.

"'Dred 'n' eighty— 'n' eighty-five," droned the camera-man.

"Now then, Morton!" shouted the Director.

Desperately the star responded in a wild attempt to recover his shattered reputation. He bunched himself together and leaped in—straight into a right glove, circling like a yellow arc of light.

ST. CLAIR shuddered back to life with the abomination of desolation ringing insistently in his ears. He struggled to a sitting position and concentrated his dazed faculties on the sound. He recognized it now; it was laughter. Ribald mirth—then something snapped in his brain. He staggered to his feet and lurched like a heroin-victim to his dressing-room, without passing a word to anybody, and with a face like a lost soul.

"Oh, glory be! What a picture!" the camera-man habbled, weeping with joy over his instrument. "Say, boy, I thought you said you couldn't fight?"

"No more I can," maintained Jem. "But I understood St. Clair could. I've sparred with Curly Dixon, and Jem Burke, and some others at the club back home—and they could walk all over me any time."

"Gosh! Why, those are professionals, man!" quavered the camera-man, marveling at the naive modesty of Jem's comparison.

Going to the water-filter Jem passed by the dream girl, whose big eyes were still staring as if in a dream.

"You're wonderful!" she faltered.

"Thanks to your warning," he jested back.

And then St. Clair came from his room, dressed for the street, and almost cringing from view.

The Director just saw him as he was opening the door.

"Hey, St. Clair, you can't go home yet; the picture isn't finished," he called cheerfully.

"To — with the picture!" the other flared with bloodshot eyes and an expression of utter desolation.

The Director recoiled. He didn't understand. Then he ran and caught the actor by the sleeve.

"But say, the picture isn't finished right," he objected solicitously. "We'll have to do that last part over again."

"Over again!"

St. Clair tore his sleeve free, turned and just glowered at the Director, with lips quivering back from the teeth at the corners.

Then the Director understood; and the camera-man understood; and so did many others.

The star's colossal vanity, which was a part of his being, reared and fostered by public adulation, had been wounded, rent, lacerated. He could never face that company again. Argument or entreaty was futile, and the Director knew it. He turned to the camera-man, paralyzed by this catastrophe, which, to him, was a world disaster.

"Good gosh!" he whispered hoarsely. "The picture! They must have it in two more days; and we've spent over two thousand dollars!" and he flopped into a chair.

The camera-man just bowed his head on his machine and moaned. Those wonderful films were to be useless.

Stafford softly drew Jem away.

"Jeamie," he murmured sorrowfully, "in just a couple of minutes you're goin' to be without a job once more; an' that although you've made good—too good. This is where you step right back to your normal an' become a student of literature again—want-ads. Two thousand bones you've cost him; d'you hear it? There's only one consolation; you didn't fall down on Frankie, an' he'll give us a job again."

And the general consensus endorsed Stafford's opinion to the full.

MEANWHILE the Director had taken hold of his shattered senses with the quick energy of mind that had won him his position; and he sat thinking swiftly, turning the situation around and attacking it from every possible angle. Presently he looked up and beckoned to Jem.

"Your walking-ticket," murmured Stafford.

"Well, young man," began the Director grimly, "you've got me into a fine hole."

"You can't blame me, Mr. Gresham," defended Jem. "You know what you told me yourself about wading in. How was I to know that he was so fragile?"

"Yes, yes, I know; I'd fire you all the same if it would help my picture one atom. But we've spent too much on it, and this scene and the river one are too good to lose; so I'm going to take a bold step and save the film by featuring you in it. I can see how the whole story can be changed by putting in some new scenes and changing some of the headlines. We must go over Scene Nine again, just the part where St. Clair jumps into the river and where he pulls her out, and make you the hero all the way through."

And he fell to discussing and rearranging his plans with the camera-man.

Charles James Stuart addressed a postcard to his uncle and printed three words on it in large Roman characters, just as another great invader had done before him:

VENI. VIDI. VICI.

Which, being interpreted, is: "I came. I saw. I conquered."

A little later Mr. Gresham got up with a radiant face —the revised scenario-plot, with those two sensational scenes to back it, had worked out strong—and called for Stuart and Miss DeNeen to give them their ncw instructions.

"They've gone out to lunch together," gurgled a voice through which a delicious giggle rippled.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.