RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

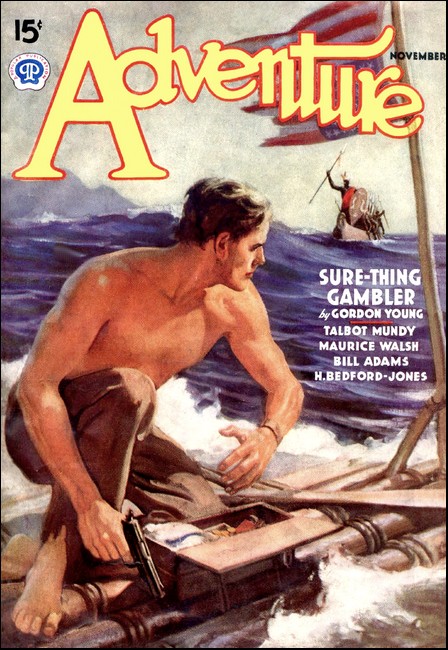

Adventure, November 1937, with "Nobody Kills Don Guzman"

"Out into the open, Americano! Man to man!"

JIM WESTON bulked on wide planted feet between the stone doorposts of the hacienda. The original vandal who had built it out of the debris of an Inca temple had set those posts purposely narrow, and Weston's shoulders just missed filling the space. His face might have been carved from the weathered oak of the iron-bound Spanish door. Only his hair, sun-bleached to the color of his own prairie grass, indicated that he was not native to this land of darker and much mixed bloods. In his hard Texan Spanish and with a grin just hard enough to show he was glad to do it, he handed on his message—a hard message.

"It regrets me, Don Guzman. Miss Filmore does not wish to see you."

Don Guzman's horse, experienced in its master's rages, splattered nervous hoofs under his sudden movement.

"Como dice? What madness is this? Listen, you!" Don Guzman's eyes retreated into dark dens under his scowl. "I am Don Porfirio Guzman. I have done much business with her father before he died. It was I who sold him this very ranch. I have bought his alpaca and his llama wool. I am an old friend of the family."

Weston remained as unmoved as the stone doorposts.

"It is understood. I have been looking into some of the outstanding accounts. The Señor Filmore seems to have been a scholar of the classics, but not of bookkeeping. I have intended to call upon you for some explanation of the system that was so profitable only on the one side."

A hulk of a man, Don Guzman, as big as Weston—bigger round the belt-line. His face was more the color of the ancient gods carved in the stone doorposts. Illappa the Thunderer scowled from one of them under his clouded headgear of Quetzal feathers, vomiting his cascades of stone rain. Weston's eyes tightened warily at the sudden thought that, damned if something in Don Guzman's promiscuous ancestry hadn't pasted on to him a beaked nose and high cheek bones that made him even look like angry Illappa.

Guzman's bull rage bunched his thick neck muscles. His hand let go of his heavy riding quirt to leave the curling fingers only six inches distant from the butt of a much more modern weapon that was holstered at his saddle-horn.

But Don Guzman was alive today because his rage was not so stupidly reckless as a bull's. First his eye flickered to either side to see whether there might be any outside interference.

There was only Olcca Wilkki, the peon doorkeeper who lived in the mud hut outside the wall. Olcca listened with acute animal ears to the hot violence pending between the lordly foreigners, but he never raised his eyes. Whatever their breed or color, they were all foreigners to Olcca Wilkki; blancos,white men; they were the tatancheki capac, lords and masters of the land that had once been his people's.

Squatted on his heels at the door of his hut, wrapped in his woolen poncho, a scarlet and green bundle with a grotesque floppy ear-lapped nightcap on his head, his body swayed in monotonous rhythm as he stropped an already spotless machete over a slab of gray pumice.

The thin, wide blade and his abstraction in his labor were coldly suggestive of waiting menace. This new blanco who bulked in the doorway had given him the machete, told him to use it for cutting the sparse ccaspi shrub of the high plateau for firewood, and told him then with princely carelessness to keep it for his own.

Nobody had ever given Olcca a present in all his life before. Olcca would never be able to understand any reason for the munificent gift—it must have been worth all of a dollar and a half. It was like the gods dropping fortune upon a man.

The blanco would never understand the dark reasonings of Olcca's mind. But Don Guzman's left-handed strain of the same ancestry was not so tenuous that he could not quite surely understand that there would be no danger of interference from Olcca the doorkeeper with his glittering machete.

So Don Guzman let his hand inch forward till it hovered just an inch over the saddle holster. But his caution still held that last inch.

JIM WESTON stood there so chunkily solid. No man would face him, Don Guzman, so coolly unless he were deadly sure of something. Those Western American men had a reputation for carrying guns and being unbelievably fast with them. And tomorrow was always another day. That was why Don Guzman was alive today.

So Don Guzman drew back and took out his rage in smacking his shiny black boot tops with his quirt.

"Dante! I see how it is. You want her for yourself. The new foreman bars all callers from the door so that he may show his zeal and make up to the rich senorita himself."

It was Jim Weston's turn to hunch his shoulders. The big muscles stiffened. Don Guzman's hand let go of his quirt again and hung over his holster. But Jim Weston said only:

"Yes, I'm new in this country, Don Guzman. I do not know the customs. I do not know—yet—whether I ought to kill you for that."

Don Guzman laughed.

"To kill—Me? Machos diablos! Listen, my so foolish friend. I am Don Guzman of Guanada. People do not kill me. When you have lived here a little longer you will know that—if you will live here a little longer."

To which Jim Weston said: "It is true, I do not know what other people do here. But I tell you this, Don Guzman: if you try to force entrance here while Miss Filmore says no, it is I who will kill you."

He put his shoulder to the heavy door—like a postern in a castle wall it was —and slammed it so that Don Guzman's horse started again.

Don Guzman cursed. His horse, familiar with the tone, plunged and shied on apprehensive hoofs. Don Guzman knew how to tame that. He hit the foolish dumb animal between the ears with the heavy end of his quirt.

He bit savage words off at the foolish doorkeeper, who heeded his doings not at all.

"Caipi! Cunallan!

Olcca raised furtive eyes. Not smartly, as ordered, but slowly he got up from under his huddle of poncho and came to the Don, his machete loose in his hand.

"Give me that, fool!" Don Guzman snatched the weapon. Leaning expertly from his saddle, he hacked up a slab of resinous yarreta moss from the ground. With savage strokes he hewed it into a rough oblong. He stabbed viciously through the tough root and with the blade pinned it to the closed door. Then he lashed his horse and rode furiously away.

DUMBLY, his beaten eyes round with apprehension, Olcca stood staring at his blade, still teetering in the hard wood. Anybody could understand yarreta moss nailed to a door. That was pure Indian sign. It meant that somebody would presently be lying stiff under a rough oblong of similar moss. And since Don Guzman had well and amply proven that people did not kill him, it looked like very soon the white girl would be all alone again to try and manage the rancho, and then— But what did any of it matter to a peon?

What mattered in a Quechua Indio's life was a machete.

Olcca's simple soul was focussed on a day a week ahead—perhaps two weeks, or maybe three; the exact time didn't matter. But presently, in the near future, the blancos would all ride their sixty or a hundred miles to the big city of La Paz to attend a ceremony of thanksgiving in commemoration of a day when one of their male gods who had died had risen again from a grave in the earth; and then Olcca and his people, peons all of them, would take advantage of their lords' and masters' absence to extract queer carven masks from their hiding places in the thatch of their huts and would fit together the parts of enormous hats, great sunbursts of egret feathers, and would go through the motions of a solemn dance that their fathers had taught them in thanksgiving for the first shoots of green barley that had died last year and were now rising from their graves in the earth.

Olcca did not know the meaning of the masks nor of the sunburst hats. None of his people knew. Probably nobody today knew.

But the fathers of the Quechua had learned the dances from their fathers. So when the green barley came the peons would gyrate cumbrously in their fancy dress to the mournful notes of huge reed pipes. There would be rejoicing in the subdued manner that is the limit of the Quechua capacity, and they would all get very drunk on raw cane alcohol and would forget for a while that they were peons.

But before they all got quite drunk a sheep would be stolen and would be sacrificed to the old gods with the newest, sharpest machete available in the whole indio community, and its blood would be sprinkled upon mullos. Mullos were very important; they were little slabs of soap-stone carved to represent mud huts and fields of grain and young llamas; and, sprinkled with sacrificial blood, they would be planted in the fields as a reminder to the earth gods that just such huts and fields and live-stock were required of them.

Olcca was convinced—as nearly as anybody could be convinced who had never before known any luck at all—that the gods had picked him for their favor. They had shown it by giving him, out of a blue sky, that princely machete. If he kept it very bright and sharp for the occasion, maybe it might be chosen by the medicine man for the sacrifice, and that would bring much honor as well as fortune to its owner. Perhaps his mullo, receiving the first of the blood, would grow into a sufficient crop of occa tubers in the patch that he cultivated behind the hacienda wall so that he would not have to go hungry during the latter part of the year.

Certainly a machete mattered more than anything else in Olcca*s world. With an inarticulate ache in his throat he dislodged the blade of all his hopes from the door panel. Pebbles imbedded in the moss roots had cruelly nicked the edge. Olcca inspected it with the dumb acceptance of an indio's lot. A fleeting resentment bit his strong animal teeth together. But it was no more than a dull glow of an almost dead spark.

With the dull apathy of a hopeless people he hunched down once more on his heels, to commence all over again his endless strop, strop on the soft pumice that he could pick up anywhere on the barren volcanic plain. He did not even know that within the wall the blanco had a stone wheel that would do the job in five minutes.

WITHIN the wall Jim Weston's heavy footsteps sounded going to his quarters in the rear wing of the Hacienda. From across the patio Janice Filmore's voice came, anxious, half fearful.

"You got rid of him, Jim? Was it all right?"

A drawer rattled open; metal thumped heavily on wood before Weston answered. He came across the patio to her, his fingers busy with the buckle of a cartridge belt.

"Just hangin' a gun onto myself. Miz Filmore. I got me a jitter, bluffin' him empty hand. Nor I don't have to be experienced in this country to figure there's goin' to be trouble with that jasper."

The girl's hand went to her lips; a brown hand on which the darker callouses of reins discoloured the first and second fingers. Above them her gray eyes looked at Weston, troubled, but steadily. Square-hewn, uncompromising, the man was a comfort.

"I'm afraid of him." She was not afraid to confess it. 'Since it's come at last, sit down and let's talk it over. Don Guzman wants—that is, I think he hopes—"

"I know durn well what he wants," Weston interrupted her bluntly. He knew very little about women, but he knew plenty about men. He stood, despite the invitation to sit, and frowned down at her from under his sun-bleached brows.

His fingers automatically counted the cartridges in his belt, as they might have been a rosary—six and a space, six more and a space. Just a little trick of his that made for quick loading. Bluntly he faced the hard facts.

"Miz' Filmore, since its come an' it's too late to duck now, let's talk straight, like you said. I can maybe drive some five—six of our crowd to put up a fight, an' we've got a good high wall. This Don Gorilla can round up how many?"

"I don't know. At short notice, perhaps a dozen who'd stick at nothing. Given time, that many more from around the neighboring ranchos who would ride with him for the promise of loot."

Weston's fingers counted with slow deliberation while he scowled. Six and a space; six more and a space.

"Would any o' the more decent rancheros send help?"

"I don't know. They're all afraid of Guzman."

"What about the intendencia? Does this Don play politics? An' that's a sixty-mile ride anyhow."

"The intendente is honest and he was friendly with my father. He would send police—given time."

"Hmh! A couple days after mañana, I suppose."

Janice Filmore's eyes were hunted things as Weston's dogged directness brought the situation down to its relentless details. But her lips remained as firm as that photograph of her father's on the mantel shelf.

Weston grunted again. "An' you're the one who wanted to stick it out! Well, you're the boss. But I'll tell you this, Miz' Filmore: I'd yank you out o' here in the half of once, only—"

The girl came to her feet, the hunted look in her eyes all gone. "You wouldn't dare! You—" The fire died out of her eyes, to smolder in angry appraisal. "Would you—against orders?"

"Bet yore best hoss I would. Only you're right; I don't dare. This Guzman rattler would like enough cut us off in the open. You're safer here behind a good wall."

Still scowling at her. Weston's fingers took in a hole in his belt. "Miz' Filmore; don't you worry. That's what a foreman's for. I'll go see about fixin' to meet brother Guzman right when he comes."

Vaguely, as he went, Weston was wondering whether that brand of conventional encouragement would fool the girl. And in the next second he was sure that it wouldn't. Those gray eyes of hers were wide open enough to know what they were up against. The eyes had the steadiness of that picture of the old man who had come so far from home to stake out his rancho along new lines woven out of the shreds of the old that were so nearly dead in his home state.

"Real ol' timer." Weston admired. "Got to fix to pull this fool girl outa this some damn how."

There was little enough fixing that could be done. The hacienda wall was a good twelve feet high and the single door was narrow and strong, a veritable fortress, built for the old unsettled days of Indian uprisings. But a fort's strength is a willing garrison. The Filmore personnel consisted of a half a dozen indios, menial hewers of wood and drawers of water. Weston grunted skeptically as he thought of them. Why should they embroil themselves with Don Guzman of Guanada, whom people did not kill?

Then there were the blancos. As brown as an indio, they, but a strain of white blood showed in their names. There was the Señor—and he stood on ceremony about the title—the Señor Alfredo Santa Ana Savedra, the mayordomo, who lorded it over Diego and Domenique and Jorge, three tawny wool-sorters; and Manuel, the more than three-quarters Cholo cook; and a stable-man. But he, too, wore a coat, a ragged one, and pants, not a poncho. That made him. too, a blanco and made all the difference in his outlook on life.

Their response surprised Weston, and their reason for it more so. Not loyalty; not gratitude for kind treatment; a reason that surged spontaneously from the modicum of hot Latin blood that flowed so pitifully proudly in their veins.

Fight for the Señorita! But seguramente: certainly and without hesitation. Gran' carallos! She was beautiful, was she not? As a pampas rose, as a lily that one offered to the Blessed Virgin at the feast of Concepción. Surely they would fight to protect her from that gross bandido, that gorilla. Como no? They were white men, were they not? Pues! Let trouble come, they would be ready.

TROUBLE came no later than the next afternoon, and they were not ready—not for trouble as brute sudden as that. Hoofs pounded outside of the door, and there was Don Guzman, truculent with just enough liquor in him to make him reckless. His horse pranced before the doorkeeper's hut.

"Quichara, alcco!" He ordered. "Open up, dog."

Dumbly in pantomime more than speech. Olcca Wilkki indicated that the stout door was being kept locked from the inside. Don Guzman raised his voice in a bellow.

"Hola, within there! You, Americano, who talk of killing me whom people do not kill. Open up. Come out and let us test this shooting of which your cinemas brag so much. Come and show Guzman of Guanada."

Alfredo the mayordomo ran to the iron grille and peered out. He turned back and shrugged with hands and shoulders up to his ears.

"He rides alone."

Jim Weston's teeth bit on his lower lip. "Cripes! I wouldn't ha' given the gorilla credit for that much." He spun the cylinder of his gun and scowled at it. He spun it again, staring at it as though fascinated by the whir of its little clicks and the blur of six brass disks against the steel. "Him an' me, by God!"

Alfredo put his hand on Weston's arm. "Señor." His fat little eyes were round with apprehension. "Do not do this thing. It is a madness. That is Don Guzman of Guanada. You are our only hope, Señor. If you should be—The good God save us; we shall be lost, looted by his gang. The Señorita—alone!"

"You're telling me?" Weston hissed. "And Guzman is their only hope, isn't he?"

Guzman's bellow came again. "Open up, Americano. Man to man, I offer you!"

Alfredo was tremulous with his reply to Weston's question.

"Assuredly, Señor. He is the horned head and the black heart and the forked tail of all the trouble in all the ranchos. Without him, there would be none here. But it is as he says. Nobody has ever killed him yet. He is too cunning and ruthless as a devil."

Weston's teeth drew away from his lower lip to show a thin, tight grin. He snapped the gun cylinder shut.

"I don't know how good he is, Alfredo. But I'll tell you this: If he downs me, it won't be before he's crippled some himself. So while he's out of business you can rush the Señorita out o' here to La Paz. Understand? You'll get the boys together and kite out pronto, before the gang can organize." He jerked his head towards the door. "Open up, an' keep out o' line."

"But Señor!" Alfredo was opening and shutting his mouth and his fingers at the same time. The other blanco stood behind him in helpless apprehension. "But Señor, if you should—"

"Go on, open up." Weston barked. "Or he'll be hollerin' that I'm scared. I am. But he can't know it."

Mumbling, Alfredo lifted the great wooden latch and gingerly inched the door open a narrow slit.

Weston swung and stood in the opening, his gun shoulder high for a throw-down.

Don Guzman was not in sight. But his voice came from behind the doorkeeper's hut to the right of the door.

"Out! Out into the open, Americano! Man to man!"

Weston stepped warily out. "Give'm credit." His lips were drawn back and he breathed tensely through his mouth. "Smart devil. Right hand shootin' round a right corner gives'm th' bulge on me." He wasn't giving Guzman quite credit enough for a fair stand-out-in-the-open-and-come-a-shootin'. He flattened his body out sideways and edged along the hut wall.

"Dios! Look out!" Alfredo's voice was a choked shriek from behind him.

WESTON never waited to look. He dropped flat, at the same instant that the whang of a big caliber rifle came from the open plain. Out to his left his eye caught a flicker of movement behind a clump of ccaspi shrub. Squeezed flat on his belly, he snapped a shot at it. A man lurched up into view and down again. From a clump of eucalyptus trees that masked the mouth of a farther arroyo another rifle banged. A heavy slug blasted a great chunk of adobe out of the hut corner.

Weston scuttled for the doorway. A rifle banged again, but he was in and kicking the heavy door shut as he rolled.

'The bushwhackin', lowdown—"

"Look out!" somebody shrieked again, and there were two men racing in from behind, another just dropping inside from the wall, racing to get to the door.

Don Guzman's voice roared fury from outside. But it was immediately drowned in the uproar from within.

Alfredo and his compatriot blancos were plucky enough when it came to a fight, and eager to make good the boast of their white blood. They fought as heroically as ineffectually—to the utmost capacity of their voices. They shouted and swore, and they even clawed and kicked.

But Alfredo and his compatriots had been about their peaceful occupations; weapons were not to hand, and no time to get them. The three raiders were armed with gun and knife; and no one of those men needed to be told what grisly things could be done with knives if the holders were once given a chance to use them.

Jim Weston was in it with fist and knee and foot, with everything that he knew—and all of it vicious, driven by desperation. The others would help, yes —but they were peaceful men, and Alfredo was fat and Diego was old. The win or lose of this mad scramble, Weston knew, was up to him.

Like a magnified ball of fighting ants the confused mob rolled and fought and bit. Dust and dried llama dung hid them in acrid billows. Out of the cloud came the thuds of blows and curses—and suddenly the hot smell of blood.

"He is a devil, this Americano! Rip his belly, Juan!"

Whack! Thud! Something hit somebody and he yelled as something broke.

Hands clawed blindly for throats and for each other's weapons.

"Hugh!" Weston's grunt of effort went with his knee. A blurred figure groaned and went down. Somebody grunted, "There's for you." A voice shrieked and somebody yelled triumph.

Furious yells came from outside. The door! Open the door, amigos! Lift but once the latch!"

"Hold them!" Weston gasped. "Anything but the latch." Smash!

He felt a surge of thankfulness for that last good one, for the fact that he was a big man and strong. And then, quite abruptly it was finished. Men lay on the ground. Some held others. There was blood. Everybody seemed to be fearfully smeared with blood. Weston bled from a rip in his khaki shirt arm. It didn't matter.

Blood was cheap against the alternative of perhaps having lost that fight for the door.

"Hold them so!" Weston spat sand and debris from his mouth. He ran to the grille, inched his eye round the corner, his gun ready, cursing vicious prayers for just a chance at any thing that moved.

There was nothing, of course. Only the appalling blasphemy of which the Spanish language is capable crackled and spluttered over the wall. Don Guzman's voice became coherent.

"Hola! Within there! Compatriots! Listen but once to sense. There is no need for you to embroil yourselves with Guzman of Guanada for the sake of a couple of foreigners. Open, therefore, the—"

Weston's hot fury of battle chilled. That was a damnable kind of propaganda that must be stopped at once. He shouted to drown it. A desperate thought, but the first practical one.

"Quick, you fellows! The ladder! Up against this wall! And, Alfredo, the scatter gun! By God, Ill mow them down like running rabbits!"

Don Guzman's oration strangled in throaty fury. True, a head appearing over the top of the wall would offer a fine target. But a shotgun—! He wrenched a crumple of paper from his pocket and smeared it flat on his hat brim.

"Pin this to the door!" He scribbled furiously.

Olcca Willki was standing in dumb inertia beside his hut, staring cowed at the group.

A rider spurred to him, caught him by the scruff of the neck, and with superb ease of balance bent to extract the obvious machete from its wooden sheath.

His machete again! A fleeting instinct of possession impelled Olcca to clutch at it. Between the two men it fell to the ground. The horse trod on it. The thin blade snapped beneath the hoof.

Don Guzman cursed. "Here, wrap it around a stone and throw it over." The paper fluttered over the wall. "Come ahead, amigos! Ligero! before that Americano devil shoots!"

The riders spurred away, scant seconds to spare.

ALFREDO the mayordomo picked up the message and handed it to Weston. He hardly needed to open it. Everybody knew what it would say.

It was for the blancos—the compatriots, not the foreigners. Don Guzman of Guanada, whom people did not kill, had no quarrel with the help of the Hacienda Filamora.

What profit was there in embroiling themselves with him on account of just two no-account foreigners? Let them knock the gringo on the head, open the big door, and turn the girl over to him; and they would all be friends, as compatriots should be; and he would promise them all their same jobs in the hacienda which he would presently legally own. All so simple and logical.

Alfredo was brutally candid. "The invitation comes just a moment late. We have already embroiled ourselves beyond adjustment."

Almost furtively he pointed out of the corners of his eyes, hating to acknowledge the thing.

One of the figures in the dust needed no holding down. It lay with its face dirt-grimed, a knife hilt under its armpit.

"The devil an' all!" Weston whistled through his teeth. "A good job. Which one did that?"

The men looked at it dumbly, the faces of all of them masks of dogged ignorance. The sweat of fear remoistened the sweat of action on their foreheads. Their voices mumbled disavowal.

"It is his own knife. In the excitement —Who knows? That is the one the Señor so terrifically hit. Perhaps the Señor himself, in his rage—Dios! Qui calamidád! That is Estéban Laredo, a cousin of Guzman's and his lieutenant. This will be paid for with blood."

Janice Filmore was unexpectedly behind them. In one hand she held Guzman's scrawled demand; the knuckles of the other were white round the pearl handle of a small-caliber revolver.

Weston's lips pinched over something inaudible. He went to her.

"I'm sorry you read that," he said.

She looked at him steadily. "I have known what he wanted all along."

Weston's scowl was unwavering through a long half minute. Then he grunted: "Good kid," and made no apology for the familiarity. He turned away to Alfredo. "Tie up the other two and put them in the well-house. Bring Diego into the office and stick-tape our cuts. How soon can Guzman recruit other riders?"

"As soon as he can get a message to some of his good-for-nothing friends in some of the other ranchos."

Alfredo's hot blood remained loyal, but he was apologetic. "We will fight, Señor, as we now must. But if there is any money, we might buy off Laredo's killing, and—"

Weston's grunt cut him short. "And there would still remain Guzman—and the Señorita." His scowl went through Alfredo and out beyond. His fingers flitted over his cartridge rosary. Six shots and a space, six more shots—

Without the door Olcca Wilkki huddled in his poncho, miserably fingering the broken pieces of his machete. Why should the quarrels of these blancos always react upon him? What great evil had he done that the gods should take away their favor from him? What great sacrifice had that blanco given the gods, that they should so let him smash all of everybody else's hopes?

Weston pointed with his chin towards outside.

"Has he sense enough," he asked, "to carry a letter to the intendencia of police?

"Assuredly, said Alfredo. "He is a good indio; that is why he was promoted to the office of doorkeeper. Given a direct order, he will carry it out with all the speed and intelligence of a good dog."

"Bring him. He's a mighty thin hope, but the only one we've got. We're bottled, and if we can't get some outside help we're done."

So Olcca was called within the wall, into the aloof precincts of the blanco's patio that he had seldom seen, and was given a direct order. He nodded. Certainly he could run with a letter, and if it might be written on the letter for whom it was, doubtless there would be some educated person in the town who could read and direct him.

"See that thou dally not!" Alfredo told him. "Stop not to rest by the way; for this must be in the hands of the intendente of police this very night."

Olcca nodded dumbly. His only comment on the order was: "A handful of coca leaf would give speed to my legs." He discarded his poncho and stood in a breech-clout, revealing a pair of thick thighs and abnormal chest expansion, the heritage of his forefathers, who had been accustomed to run for the Inca.

The blancos stood bunched at the door and watched the bearer of all their hopes across the plain. Weston's fingers left his cartridge-belt as he noted the long, tireless lope that never faltered, steadily on, well beyond rifle shot.

From beyond the screen of the eucalyptus grove that grew at the arroyo's lip sounded horses' feet. And presently a rider—well beyond rifle-shot—came into distant view, trotting leisurely to overtake the runner. From the grove came Guzman's great bull laugh.

The blancos stood helpless and watched. The rider, without troubling to dismount, leaned from his saddle, cuffed the runner about the ears, took away the note, trotted leisurely back.

"Ye-eah!" Weston growled. "Smart as a devil!"

Olcca, more slowly, trotted back to his place beside his mud hut at the door. One blanco had given a direct order; another had taken it away from him. What did it all matter? It was the affair of the blanco. What mattered was his broken machete that the blanco had quite hopelessly smashed.

"Bottled and corked," Weston said. "Get back in from that door. Wonder they haven't taken a shot at us already. Come and sit, hombre. Let's see if we can dig any good out of talk."

So dejected men sat and talked plans back and forth; the same futile plans around the same old ironbound situation: and all the best of them remained quite as hopeless as Olcca's ruined machete.

"How long," Weston asked, "before Guzman can get a message around to the ranchos to call in a few more gorillas and rush this place?"

"Before morning's light, easily." Alfredo mumbled. Heroics, born of hot blood, could easily simmer down to the cold edge of despair. "Perhaps it is not yet too late to make an arrangement and buy free."

"And there would still remain the Señorita," Weston said.

And that was the end of the war council.

Without the wall Olcca Wilkki hunched on his heels in even greater despair and ground miserably at the remnant of his blade. And as the square, jagged end began to shape down to a point, his despair was absolute. What medicine man would ever choose this misshapen tool for the sacrifice? Broken short, stubby, who could hope to hew a sheep's neck through at one clean stroke, as the gods demanded? The thing was good for nothing at all now; except maybe a foolish throwing knife, like that of Thirrpu Nuñes, the halfbreed. Wretched fool, ever to have thought that the favor of the gods could descend upon an Indio—just because a blanco had carelessly given him a machete. The favor of the gods was for those who could make them a blood sacrifice. It was for the blancos, who had made many blood sacrifices, who had come to the country in the first place as gods. Why couldn't they conduct their lordly quarrels without dragging a poor peon into the whirlwind of their course?"

SO, when the next raid thundered down with the night's blackness, Olcca cowered against the angle of his hut and left them to their affairs.

Horses stamped around the wall and whinnied and plunged. Men jostled and fumbled and swore, secure in the darkness against the shooting of that Americano for which Don Guzman had such a respect. By the sounds alone one could tell that expert horsemen rode their animals close and stood on the saddles to reach up to the coping of the wall.

A head scuffled up over the edge, a round blob of shadow against the scarcely lighter sky. From inside, the shotgun roared. The shadow screamed and disappeared. By the sounds one could tell that a body fell heavily. Devils howled confusion without, and confused voices shouted from within.

Another head appeared over the coping. Its blind shriek of agony answered the gun's second barrel. Again a head looked over the top. The thin crack of Weston's gun was hardly heard above the uproar. Silently that head fell back into the dark.

Black shadows milled and stamped. Furious voices screamed to each other that the night was not black enough, that shadows against a skyline were always at a disadvantage if shooters kept their heads. The voice of Don Guzman cursed in frenzy.

"Llevelos el Viejo! All right, then. Come away there! They have too much advantage this way. We'll take them in the morning, rush the place and get it over with. Some of you will go down; but those who remain, there will be the more loot for them. Come away!"

The sounds of horses' hoofs thundered away to the shelter of the eucalyptus grove. Voices still shouted and cursed out of its darkness. A flicker amongst the high branches indicated a camp-fire.

Within the wall kerosene lamps flared. Men looked at each other, the whites of their eyes big in the uncertain light, flushed with desperate excitement, but not with victory. They mumbled futile plans all over again—the same plans, as hopeless as before.

Jim Weston stood lowering, frowning at Janice Filmore, as though it were her fault. She was able to smile at him, tight-lipped.

"Don't worry about me," she told him. "I have—this." The pearl-butted revolver was steady in her hand. "I'll hold the last shot. I promise." No heroics. Just steady determination.

It came to Weston that just about so her father might have said it, holed up somewhere against whooping Indians—and must have gotten out of the mess somehow by sheer guts.

The voice of Alfredo rose prayerfully in the night, cursing Don Guzman all over again for the beginning and the end of all evil, for the head and the feet and the forked tail of this whole devilish trouble. If the devil, his master, would but blast him from this fair earth, this great hulk of a Don whom people could not kill, this attack would be left without heart or head.

Weston strode to him and took him by the shoulders. There was hard eagerness in his tone.

"Yeh, I've been thinking about just that too. You know the rest of the gang, or you can guess pretty well who's in it. You mean that?"

"But assuredly, Señor. As I have already said. He is the heart and the brains of all the evil in all the ranchos. If the Devil in his own black night would—"

Weston nodded, his teeth hard on his lower lip.

"All right. I'm going after him. Reckon that's her only chance."

"But, Señor! What—"

Weston snarled at him. "I don't know what. Sneak up on him. Kidnap him, or—" He was frankly brutal—"bushwhack him out of the dark. It's him or me, and it's our only chance! As soon as daylight comes they'll pick us off like crows."

He took four long strides to Janice Filmore. Without preamble or ceremony he drew her to him, quickly and close, and kissed her.

Without fuss or false modesty she hung in his arms. Only her eyes closed.

She opened them and looked at him steadily as always.

"I think I have known this all along too," she said.

They held each other so for a moment and then pushed free.

"Don't worry." It came from both of them at the same time. She smiled.

He strode to the door.

"Shut it after me and hold it," he ordered Alfredo. "God knows what for. But hold it."

IN the eucalyptus grove the scantiest of camp-fires flickered. Shadows huddled about it. Grunts of conversation. Dim forms lay prone. Fumbling footsteps and grumbles came from the farther dark.

Jim Weston crept like a scalp-hunting Indian. Which of those dark bulks would be Guzman? There would be no room for a mistake here. But what a forlorn hope it was, now that he was here, to make no mistake about his man in the blackness that was his only hope!

The fire's thin flicker made shadows jump and move with heart-stopping reality. Low bushes swelled and swayed, loomed close and faded again. Blanket-wrapped bulks lay in shapeless outline. Three black shapes squatted close over the fire, muttering muffled gutturals. The one with his back full towards Weston might be Guzman; he bulged big and his shadow made a great wedge of welcome blackness behind him into which a man might crawl. And if it should be Guzman—what?

Weston's teeth, gritting on each other, frightened himself with their noise. God! He must be silent, sure and deadly silent; otherwise death would be the easiest thing that could happen. It must be Guzman and no other. And then—Holding his breath, he crept closer to a shelter of a blacker shadow.

The shadow rolled over his groping hand and bellowed out startled afright!

Other shadows yelled instant response. Dark masses plunged forward. The night was suddenly full of shadows that shouted and swore and fought.

Someone yelled; "It is the Americano!" Someone shrieked in pain. Grunts and oaths and blows filled the darkness.

But that could not last. When the tumult subsided Weston stood in the fire flicker like a bear ringed by wolfish men, held by arms and legs and neck. Don Guzman stood before him and laughed, a throaty laugh of rippling chuckles.

"Amigos," he said. "From a night of weary waiting, the customary good fortune of Guzman has turned into one of great amusement. Go, one of you, to the horses and bring, first, a riata to tie him. He is big and strong and will last long."

At which all the other shapes that loomed like lesser devils laughed.

"Hold him well," one panted. "He is fierce and as strong as the father of all devils."

"Cra." said Don Guzman. "But this is dark. In order properly to enjoy this amusement that Providence has sent to us we must have a good fire. Not only to heat the knife blades, but to see that we do not all at once cut him too deep. Go, another one of you, and bring that fool of an indio to cut us some firewood. In the meanwhile let us sit. There is time."

FEET stumbled away. They came back, and naked feet shuffled beside them. Somebody struck a match. Olcca Wilkki was shoved forward by the scruff of the neck so that he nearly fell. "Firewood," Don Guzman ordered. It was a direct order from a blanco. But Olcca. for the first time in his life, instead of jumping to obey like a good dog when his masters ordered, only stood. Ox-dumb. He had no tool with which to cut fire wood. These very men, in their carelessness over such trifle had ruined it forever for all such purposes.

"Carallos!" Don Guzman himself, in his impatience, wrenched the ruin from its scabbard.

Olcca stood sullenly. His machete again! Always his machete! No machete now, only a stump. Useless for the sacrifice of the mullos—useless even for firewood; a remnant reduced down to nothing better than the feeble knife blade of Thirrpu the halfbreed. Nobody could understand the ways of the gods, who had caused the one blanco carelessly to give it to him and another blanco just as carelessly to smash it. Why should the gods favor an indio who could give them no blood sacrifice?

"Inferno!" The hell!" Don Guzman laughed. "The thing is useless for anything at all." He pitched it into the outer darkness and with careless habit kicked the indio after it. "Come on, hombres. Scout around. We must pick up whatever kindling we can find. Our sport waits. Where is Pablo with that riata?"

In the further night a sobbing, scuffling sound persisted, like the strangled winning of a dog that is mad. A hulking shadow laughed.

"It is the indio, looking for his knife. Fool. In this darkness one could scarcely find a horse."

Don Guzman's face grinned above the lean fire glow. "I will bet anybody a horse he will find it. I know those fellows. He will smell it out like a dog. Go bring him in, somebody. Give him a real blade and make him smell us out some firewood."

Feet moved away, stumbling in the darkness, blundering hopelessly. They came back growling.

"Thousands of devils! How can any man catch that animal of an indio in such a black night?"

From out in the blackness sounded a sobbing little yelp. Inarticulate. Like a dog. A dog frantic with joy—or perhaps frantic with fury. There is not much difference in the tones of dogs in the dark.

Don Guzman, who knew so much about indios. grinned over the fire.

"There! Didn't I tell you? He has found his knife. I'll bet you."

From out in the darkness the knife came to win the bet. The trifling knife that was good for nothing at all—except perhaps a throwing knife, like that of Thirrpu the halfbreed. It flickered over the lean fire and planted itself with a soft meaty chuck in the throat of Don Guzman of Guanada, whom people did not kill!

A gasp hissed from the throat of every other looming shadow. A quick tension of afright at sudden death out of the dark. And then a slow letting go of pent breaths and a loosening of taut limbs.

And in that moment of opportunity Jim Weston was free. A big man, as strong as the father of all the devils and with something back in the hacienda worth fighting the fight of his life for.

Shadows bulked about him, suddenly leaderless, indecisive. Jim Weston smashed all his weight and fury at the nearest. It moaned and dropped to the darker shadows about his feet. Jim smashed at the next. There was no indecision about him or fright. He was strong and full of the fury of all the things for which strong men fight.

From the outer darkness something whined laughter. Not like a dog. Like a man whose faith was reassured that when the gods received their blood sacrifice they always repaid in full.

That lordly blanco who had given him the machete in the first instance was making all that quite clear just now. He was as godlike in his fury as in his munificence. Surely he would give a poor indio another machete.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.