RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

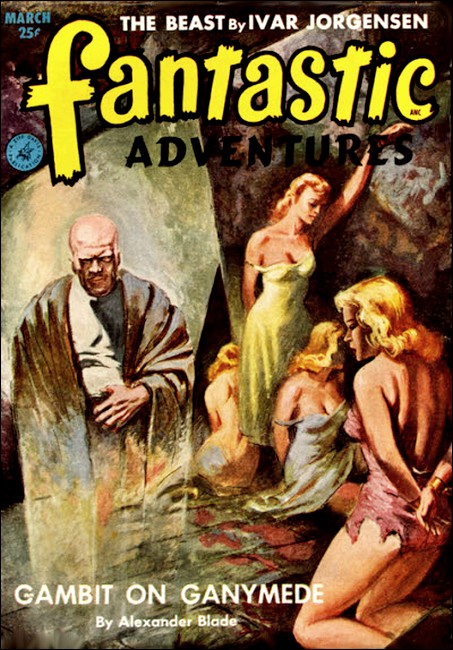

Fantastic Adventures, March 1953, with "Projection from Epsilon"

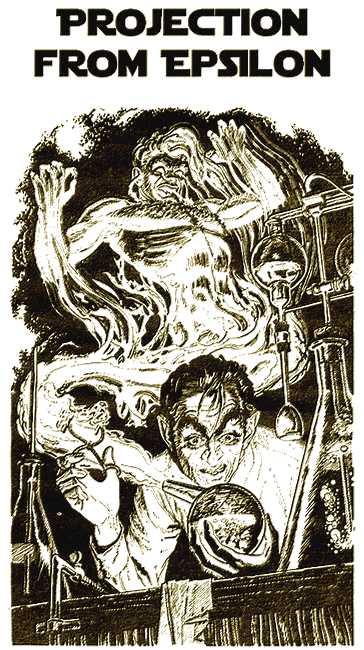

Unwittingly, Dr.Weiler had opened a door for the monster.

No greater peril ever confronted mankind. Earth was in deadly peril from these bold invaders. No one stood in their way except a studious professor who couldn't see them!

DR. KENDAL W. WEILER didn't look like a man who would premeditatedly murder anybody. Or who even could. His shoulders were frail and stooped studiously within their too shiny, once-black jacket, as though unable to bear the weight of the bulging forehead that loomed over tired eyes peering through bifocal lenses. He scribbled some more untidy calculations on the blotting paper of his desk pad and muttered to himself in peevish frustration.

"It must lie somewhere beyond decimal eight zeros and something but before cosmic ray. Hm-mm-mm. Possibly within danger of dissolution vibrations."

Dr. Weiler looked, in fact, so much like the cartoon of a professor that it was difficult to believe he wasn't trying to fool you into thinking he was one, and actually a very brilliant one.

Dr. Weiler never fooled anybody. But he knew that the human mind, howsoever honest, could fool itself. And, as a corollary, that if you could see through its vast ramifications of subterfuge and not let it fool itself, its capacities were, he liked to think, limitless.

Therefore with a merciless scientific ardor he pursued the facts of mental possibilities, although he well knew that they could go beyond the fringes of madness into worse and farther flung dangers. He had been through all those fascinating experiments In extrasensory perception. He accepted the proven facts of telepathy, and having accepted, had no further interest in those and went on to explore telekinesis. Those experiments of Dr. Rhine's into the mental control of the rolling of dice or the turning of a card seemed to open up once again the long lost theories of a mind, without any physical contact, moving inert material objects. Lost, the doctor repeated in his own mind. Not unknown. And he quoted to himself out of a righteous upbringing: "If ye have faith ye can move mountains." Well, what did that mean? That certainly had not been spoken in jest. But despite that upbringing Dr. Weiler had no faith in anything. Facts, he wanted.

And why not? The answer to telekinesis, he was sure, would be found in the field of the invisible vibrations. Sound vibrations, of course, could shatter glass. Beyond the wave lengths of sound, light could affect and set in motion a thing so inert as a selenium plate. Beyond the ultra-violet then, at I.0.000014", there were bands of—He was disturbed, as he concentrated on his calculations, by an out-of-the-eye-corner fuzziness of a man easing himself into the chair beside his study door. He had heard no knock and he had not invited anybody to come in—at least, be didn't remember having done so. He turned his head, chin low to bring his upper lenses to bear and to peer through. And of course there was nobody there.

"Imagining things," he told himself peevishly. And then he angrily shook himself. That was how minds fooled themselves. He took off his glasses and wiped them, blinking the tiredness from his eyes.

BEYOND the ultra-violet, then, there were other bands of light vibrations,

invisible to the human eye, though proven by photography. And beyond these

again, but capable of affecting the material of brain cells must lie the wave

lengths of the mind; and why should they, too, not be able to—

The theory seemed so reasonable that the doctor leaned back to rest while he speculated upon it. So reasonable that one might almost accept telekinesis as a fact and might go on into the still more fascinating field of telekdelosis—the old and very old miracle of setting up vibrations that could dematerialize an inert object and reassemble it again at will.

Miracle! The doctor caught himself up again. He didn't believe in miracles. In those old days of his scriptural upbringing it was called a miracle when somebody suddenly appeared in the midst of a gathering where doors were locked. And it seemed that certain of the Hindu Yogi were able to do it right today. Those people were just ahead of the modern skeptic world in mental science. Produce the proper vibration and—

And then there was that man again! Dr. Weiler turned quickly, his forehead wrinkled over the bifocals, and this time the fuzziness didn't disappear. The doctor blinked his eyes tight and shook his head before looking again. The thing persisted. Distinctly a man—or a ghost. But Dr. Weiler didn't believe in ghosts. He had no facts about them as yet. Although he could see the back of the chair right through this one. It wasn't exactly sitting. It seemed to be sort of hovering in a sitting posture just above the chair as though trying to force itself into it.

The doctor took off his glasses again to wipe them—during which blindness the shadow might have been a buffalo or a fiery dragon. When he was able to look again there was now distinctly a head; an oversized head a good deal like his own; and a face, its brow screwed in intense concentration. The effort seemed to solidify the shadow and give it weight enough to settle into the chair. A vague and quite unscientific impulse of fear dissipated as the doctor could see that it was a frail thing under its big head, no more of an athlete than himself. It wore a sort of toga garment, a draped sheet sort of thing that a mahatma might carry with dignity. The doctor's unspoken thought was a compliment.

"Hmm! A type of superior evolution."

The shape, quite solid now, nodded as though it had immediately understood, and it smiled. It held itself down into the chair with its hands. With slow hesitancy it formed words, pointing with its finger to clarify.

"You—talk. I hear." The accent was that of a studious foreigner who had seen something in a book—or in a brain—but had never heard it pronounced.

The doctor talked less scientifically than he had been thinking.

"So who the hell are you then?"

The man nodded delightedly. "Talk. I must hear—sounds of—your mind."

Sounds of his mind! It made sense to the doctor immediately. It was exactly along the lines that he had been thinking. He talked, slowly and distinctly:

"I gather that you can telepathically sense the meanings of what is in my mind."

The man nodded.

"But you are unfamiliar with English. Therefore you must hear the sounds of the words that convey my thought in order that you may in turn formulate sounds with which to reply."

The man nodded eagerly again. He was already able to say, 'Talk more. I adapt to your speech."

TALK was one of the things that Dr. Weiler could do well. He talked at

great length. Lectured, as to one of his classes; though never in his classes

had he found a pupil so receptive to his talk. But he could hardly say,

receptive, for this man was far ahead of him in this groping science of the

mind—and, it seemed, in every other science. What delighted the doctor

was the astounding mnemonic capacity to catch and remember the sounds that

made English words to convey the thoughts they represented. Before an hour

was past the man was able to pronounce an answer to the doctor's as yet

unspoken question.

"I caught your—vibration and so I was able to project myself to your radial focus." He spoke hesitantly on the less familiar terminology.

"Project yourself?" The doctor repeated it. "From where?"

"From what you would call— Let me think now. You would call it planet Epsilon in our solar system of Seknocwath. You do not see us because we are behind the dark cloud in the constellation that you call Ophiuchus."

"But then how could you— Have you instruments to pierce the obscurant dust?"

"No, no, no." The man shook head and hands. "We do not see you either. But your thought, of course, can instantly traverse any obstacle. Myself, catching your vibration, was able to transpose my own cell material into cohesive thought and follow your beam, here to reassemble myself in material form—though, as you saw, with some difficulty owing to gravitational difference."

"You mean dematerialize and then re— But then you've got it! Telekdelosis! As I have been trying to rediscover it!"

"Oh yes. Long ago. We accept it as the only possible method of interstellar communication. I am one of several from our planet who has been assigned to explore other habitable planets with a view to colonization." He cocked his big head to one side almost as though listening. "But I perceive immediately that you have jealous, and it seems rather stupid, laws to restrict immigration amongst yourselves, causing, no doubt, dissension." He smiled scientifically tolerantly over such foolish racial emotions. "It may be then, if our other explorers do not find some more favourable satellite, and since there are some nine million of us who must move, that we may have to—" His smile was one of cold science that has transcended emotions. "—to clear off some desirable section of this one and take it over."

The doctor missed for the moment the implications of that cold, clear off and take over by just nine million would-be immigrants, spoken as though there could be no doubt about capability as well as callous disregard for established people's rights or wishes. He was jubilant, rather, over the prospect of this man's so far advanced scientific knowledge at hand.

"Then you will be able to instruct me—all of us—in your scientific advancements."

The man remained calm over the prospect. "We might instruct such of you as are emotionally advanced enough to accept scientific thought in its purity. IF you, or some less prejudiced portion of this earth of yours may be willing to recognize our urgent need of entry."

At any other time the doctor would have been interested to recognize happily this man's carefully enunciated speech reflected his own rather didactic professorialism. Just now there was vastly more important information to learn.

"Why must your nine million people so urgently emigrate from your planet?"

"There are many reasons." The man closed his eyes and frowned in concentration. "I find I must explore somewhat beyond your familiar orbit of thought to acquire the necessary words—into other minds, you understand. And, by the way, my name in your sounds is Sek-o-mil-ten. We, too, have a habit of shortening down to Sekten. Permit me a few moments, will you?"

IN those few moments Dr. Weiler thought of a thousand other eager

questions. Sekten came out of his concentration. He was as willing to lecture

as was the doctor.

"Very well now. Our life conditions are controlled, as are yours, by atmosphere. We are somewhat smaller than your earth. Our mass is relatively about .80; therefore our velocity of escape is approximately 6.4 as opposed to your 7.1. It follows, then, that as we cooled we lost more of our atmosphere than you did. Also we have three satellites, all somewhat closer than your moon. Their gravitational pull, too, has been a factor."

This was quite a way beyond the familiar orbit of thought of one who was no geophysicist; but the doctor was informed enough to follow.

"We are also," Sekten lectured on, "somewhat older than you. Therefore, as our science has advanced farther, so has our process of drying out. Our waters are receding, as of course are yours also."

The doctor knew about that. "Yes, but it is going to be a long time before our dehydration causes any urgent need of retreat to some other world."

"Ah, but what you are failing to realize, my dear doctor, is the appalling correlation between dehydration and—" He said it weightily. "—de-oxygenation!"

That item, the doctor did not follow. Sekten elucidated.

"You of Earth have not felt the effects as yet; but you very surely will. For, as surface water recedes, more and more of the igneous and basic rock becomes exposed to this so unstable element of oxygen that we, as you, must have to breathe, and the combination naturally forms the ferrous and ferric oxides that are as useless as any other iron rust; and the process, of course, is cumulative according to the square of the area exposed."

"Why, er—yes. But—" The doctor was searching back into his school days for the familiar formula. "—what about the catalytic action of chlorophyll in the vegetation absorbing the carbon out of CO-2 and releasing free oxygen again into the atmosphere?"

"True. Quite true. But—" Sekten pointed a finger at the doctor almost like a threat. "Do not forget. The less water, the less vegetation! And—" His pinched face became grim. "—there is where we, even with our advanced science, made our fatal mistake—the same mistake for which you are so blithely headed. In our war against insect pests we long ago developed efficient insecticides. Harmless, we plumed ourselves, to our form of human life." He cackled a twisted laugh. "So efficient that we completely eliminated nearly all forms of insect life." He looked at the doctor as though he had established his obvious conclusion.

"Well, er, that would seem to be rather a triumph of science, wouldn't it? We humans are prone to ask in our exasperation why God ever created insects?"

"Aa-ah!" Sekten rasped it savagely out. "So we conceited ourselves. We had made our summer evenings fit to enjoy. We had rid our crops of the thousand pests that took their toll. We patted our triumphant backs." His pinched face under its domed brow contorted. "What we lost sight of was that, with the exception of a few self-pollinating plants, some ninety percent of our plant life is—I should say, was—pollinated by flying insects. We eliminated them, and with them the ninety percent of our vegetation that reproduced itself through the pollinated flower! So—!"

THIS time the dreadful conclusion appalled the doctor. "You mean, no green

plants, no chlorophyll." He turned it around in his mind dizzily. "Therefore

no replaced oxygen? Good Lord!"

"Of course," Sekten shot the finger at him again. "All those in our administration who were responsible for this criminal mistake, as it was hideously borne in upon us, were immediately disintegrated. But that punishment does not now restore a ruined world. We who are left, subsisting upon oxygen artificially extracted from our depleted atmosphere, must emigrate to a new planet."

Dr. Weiler shivered. "Disintegrated? Rather drastic, wasn't it?"

"But my dear Doctor!" Sekten shrugged his thin shoulders and smiled. "You, as a scientist yourself, know that, in a question of racial survival, mistakes so deadly cannot be tolerated."

Dr. Weiler's face twisted in wry rumination. "If we were to apply that penalty to the administrators of just our national survival, I'm afraid there would be a decimation of—"

"Of course." Sekten got up from his chair and walked about the room, clumpingly in his sandal-shod feet but with an ever increasing energy. "Ah, I have to accustom myself to your slightly heavier gravity. But with the exhilaration of your so good oxygen here— As I was about to say, of course when we take over we shall immediately eliminate dangerous blunderers and shall establish a scientific regime very careful to profit by our own mistakes. We shall not again endanger our survival by any unscientific sentiment over inexcusable error."

The manifold advantages of advanced science seemed to have developed some concurrent disadvantages. The Epsilon scientist's face screwed up again in receptive concentration. "As I am saying this thought impinges upon my focal point that there exists on your planet here a race that is emotionally advanced enough to regard, er—'liquidation', they seem to call it—as an acceptable process for the elimination of misfits. It might be, then, that those people might be glad to open their immigration doors and to profit by our advancement."

Dr. Weiler's first exhilaration over the prospect of advanced scientific instruction chilled away to an emptiness in his diaphragm. Good Lord, if those other people should be offered an opportunity to take up this creature's merciless scientific knowledge theirs was not the kind of administration that would hesitate—not about anything. Dr. Weiler shuddered the thought away from himself. He was realizing for the first time that those petulant scientists of nuclear fission who had their tantrums about governmental restrictions were akin to children in a nursery, pouting because their plaything must not be distributed according to their own little uncontrolled whims. He felt he was guilty of a blasphemy against the whole hitherto sacrosanct theory of the freedom of Science, spelled with a capital S, when he admitted he thought that knowledge uncontrolled could be a deadly epidemic. He tried to reassure himself that all this was still possibly in a theoretical stage, just as he himself had been working on his theories.

"Well, er, have your scientists been able to get their theories accepted by practical engineers? I mean, to work out all the details of interstellar transportation for a mass emigration of nine million people?"

THE Sekten face smiled as a superman in condescension. "But my dear

Doctor! As I told you, we have long ago abandoned futile research into space

navigation. Consider it for yourself. Weare relatively close. In terms

of your reckoning we are some seven light years distant. Your nearest, as the

thought impinges upon me from somewhere, is about four, isn't it? Very well

then, assuming that we could construct some fantastic space ship that could

travel with the speed of light, that is to say, one hundred and eighty-six

thousand miles per second!" He laughed as he emphasized that and

watched the doctor to observe if it might soak in.

For Dr. Weiler it was too stupendous a thought to form any practical picture of impossibility. Sekten went on almost pityingly:

"Your people, I hardly like to remind you, are still fumbling with their hopes of achieving mere escape at seven point one. Meteorites that enter your atmosphere at speeds one thousandth part that of light are incandesced by friction and disappear; otherwise you would be bombarded by a barrage of artillery as is your moon that has no atmosphere. You would have to live underground— Ah! I receive a thought here that you are already contemplating doing so for fear of nuclear fission bombardment."

Dr. Weiler was just staring at the man—the humanoid creature, he was calling him now; and he suddenly eeked at the hideous realization that the creature could telepathically receive the uncomplimentary thought. But Sekten was apparently tuning in on other beams to receive the vibrations of outer information. He expounded further:

"But let us for a moment disregard those very practical difficulties. Assuming that physical transportation might be feasible at so fantastic a speed, we would have to construct indestructible vessels somehow large enough to carry our nine million with supplies enough to last through a voyage of seven years duration!"

That one at last was getting down to figures that could be pictured. IF all the other difficulties could be overcome; and they loomed so formidably that Dr. Weiler nodded almost cheerfully over the probability that any mass immigration would be remote. Sekten demolished his cheer, agreeing with the impossibilities.

"No, no, my dear Doctor. These things are fantasies, fairy tales for the amusement of child minds. We, as serious men of science, have long ago discarded them. Our method of travel is what you yourself have already conceived and have explored under the term derived, I perceive, into your so curiously inefficient speech from a dead language of the Greek people of some three thousand years ago. 'Telekdelosis'. We establish a mental vibration that dematerializes the material body, retaining the individual thought nucleus. With no more effort, then, than thought projection we convey our nucleus to any desired location and there reassemble ourselves. The only requirement is that we find in the chosen location the same chemical elements that we left behind. Your earth fortunately possesses them in abundance."

"Good God!" said Dr. Weiler. "And, er, how long does this process take?"

"Depending upon the individual's learning and capacity for concentration, from a few moments to possibly several attempts. We can, however, assist our less literate population in achieving a reasonable percentage of success. We expect of course to lose some fifteen or twenty percent of the more stupid ones who are incapable of absorbing assistance. Those, we would leave behind; frankly without too much regret. I assure you we shall not encumber your earth with our moronic undesirables."

HE spoke as though he found Earth conditions so favourable that he was already convinced his planet's elders would direct their emigration here.

"Ten or fifteen percent?" Dr. Weiler was shocked at the two extremes of emotion and practicability. "You would leave them to your dying planet? But there'd still be some seven million of you! And frankly, Mister Sekten— Or I suppose I should say, Professor— I am sure there is no place on our Earth where you would not meet with considerable resistance to so great an influx. Why, that would completely disrupt the economic stability of any people we have."

''My dear Doctor!" Sekten threw out his hands and shrugged almost humanly. "We would deplore the use of coercion; for we have evolved to a peace-loving people since we eliminated war for the very practical reason that the last one we had extinguished some two and a half billion of us. But we still know how to do it if we must, and, as I have told you, our need, owing to our stupid depletion of oxygen, is imperative. We must find a new planet to colonize, willy-nilly."

"Two and—a half—billion?" Dr. Weiler sat back aghast in his chair. "Heavens! What fearful thing was it?"

"Oh, a quite simple ultra-sonic device that we discovered how to fan out over a broad area. It raised the normal blood temperature from our ninety-nine to above a hundred and ten. We found it very effective and clean within a range of approximately a hundred and fifty miles—ample to stop any antiquated bomber pilots as well as long range guided missile installations. Unfortunately both sides had it. We can, of course, dematerialize equipment and reassemble as needed."

It was then that Dr. Weiler, law abiding man of science, decided that he must murder this super scientist; that this cold product of knowledge untrammeled must not be permitted to escape back to his own merciless planet with his report of Earth as an immigration colony. Nine million of them— Or seven or whatever number might be left after they had callously lost their ten or fifteen percent of the unfit! Good God!

Dr. Weiler did not as yet know how he might avert this catastrophe. He didn't dare to think how a man might be killed who could instantly read the thought in its very forming. His blood ran cold down to his feet in a panic lest the man had already sensed the fleeting impulse that he was trying to push back into the dimmer recesses of his mind. He must not let himself think about it. He must fill his mind with other overwhelming thoughts.

He had enough of them whirling through his mind, crashing down the walls of his temples. Science, spelled as he had been wont all in capital letters, was not the supreme aim of human endeavor. The god of Science that he had worshipped, that the vast dumb peoples of the earth had been taught to revere without question, was a monster in devilish disguise. It had already shown its diabolism with nuclear fission and now came this man, this humanoid thing without a soul, to show how the idolators of his world had nurtured the Devil to rule from a cold pedestal so high that no warmth of human feeling could reach it.

How did one go about killing an omniscient devil?

How could a mere human scientist of Earth be sure that no thought nucleus would remain after a body had been killed to go back and report upon the desirability and the helplessness of Earth?

THE creature's infernal receptivity must be kept busy with other thoughts.

His total effort resulted in something no less banal than,

"Of course, Mister—er, Professor, I would be honored to have you stay with me as my guest and mentor. I live here alone and—" Of course the frightful creature must stay. In order to kill anything you must have it to hand. "Er, that is to say, I suppose you do stay somewhere? Or—?"

Sekten sensed that question at once. "Yes, certainly. The effort of disintegration expends a good deal of energy and, where not necessary, it is to be conserved. I shall be delighted to accept your invitation."

Good God! So now he had done it! He had condemned himself to live with a scientist—one worse than himself—for some indefinite period.

"Well then, it would be nice to have a light snack of—I suppose you, in rematerialized form, do eat? I, ah—would like to invite you out. Unfortunately at the moment I—"

Sekten smiled like a friendly Lucifer ready to buy a soul. "You have no money in the house? It used to be a recurrent problem with our scientific men too. I am delighted to assure you that the little problem need never worry you again. Ah, I perceive that you use paper as a medium of exchange and that a depository is nearby—a bank, you call it? Very well— Oh, I ought, I suppose, to make for myself some clothing less startling to the stupid herd." He frowned in concentration, his large head and little features looking like an ageing apple beginning to wrinkle underneath. As he did so his toga, dissolved away as in a movie trick and resolved again in the shape of an ill fitting suit almost an exact copy of the Doctor's. "I shall be back in just a few minutes."

The man, frail thing that he was, talked about getting money from a bank as casually as a gunman contemplating a hold-up with a tommy gun. Dr. Weiler devoted the whole of those few minutes to a frantic effort to think about murder, astoundingly blaming himself that his tastes in literature had hitherto scorned the lurid publications that told how murders were done. Heavens, how inadequate was Science in matters of practical need!

Sirens were already whining when Sekten came calmly back. He emptied his shapeless bulgy pockets of bundles of money, all neatly stacked in rubber bands. "I very nearly took larger denominations for their ease of stowage," he chided the doctor. "You should have warned me they placed marks of identification upon them. Fortunately I caught the thought in the mind of a would-be too clever clerk. These are tens and twenties. Enough, I trust, to last for some of our immediate needs."

"The—sirens?" was all that Dr. Weiler was able to think. "What happened?"

"They were quite stubborn about letting me have any of this material; and of course they refused to accept any threats not backed by a visible weapon. It was necessary to immobilize them."

"To—immobilize?" Dr. Weiler felt a certain measure of relief. Doubtless some super-scientific process of hypnosis or something that could strike a man suddenly dumb and submissive. "But then—those police whistles and things? How—?"

PROFESSOR SEKTEN of Epsilon was nonchalantly friendly about it. "I am sure

we shall be able to teach some of the further advanced of you when we

establish our new regime. The process is projection of a vibration that at

close range temporarily paralyzes the brain cortex. It seems, though, that I

have not realized just how fragile you Earth people are. So—"

Dr. Weiler's relief shivered back to quivering tenseness. "Fragile? You mean—?" Both men spoke with the doctor's habit of agitatedly unfinished sentences.

"I am afraid so. With those four or five whom I contacted it might be permanent. Were I given time I might revive them; but your police, it seems, are extraordinarily well organized in their cruder methods and of course would never accept any explanations that I might offer."

For a hopeful second, until he could crowd the thought out of sight, Dr. Weiler thought that the police might be the people to take care of this monster of Science. But, as Sekten so casually said, in order to understand even the elements of the case they would first have to recognize their whole crude method of thought.

"In view of their hysteria," Sekten smiled, "it would perhaps be better that you—er, may I say, my colleague; or perhaps better, my pupil?—should go out alone and bring in some supplies. Since Science is above all things practical, we cannot perform fairy tale miracles. I am unable to reassemble myself in some other unrecognizable body containing different proportions of the epithelial cells."

Dr. Weiler was sweatingly glad to get away from there; to try to compel himself to think in terms of cold cuts and delicatessen salads. If this dreadful machine should pursue him with its thought— But no, it would be exploring far afield, tuning in on other waves created by people strongly vibrant enough to set up foci of attraction. "Good God!"—it shocked the doctor to a standstill. Perhaps on the foci of those other people emotionally fitted to snatch at every cold advancement of Science and to use it as mercilessly as this one toward the advancement of their own fanatic ideology.

Down at the end of the cross street he could see the mob milling before the bank. Its murmur and the sharp commands of the police rose like a sublimated blatting of sheep. "The stupid herd"! Any one of them, Dr. Weiler felt, educated in current herd "comic" literature, would be able to give him a dozen ideas about how to kill a man. How useless in an emergency was all his puny learning and his study of the potentialities of the human mind!

He harbored the mad thought of going up to one of the policemen and asking him how one might set about the murder of a telepathist who could immobilize a roomful of people by projected thought vibration? And then he snorted to himself, picturing the vacuous grunt of complete non-comprehension that would answer him. Even were he to go to headquarters and explain patiently and slowly to some slightly superior intelligence, he knew that he would be met with soothing words and, would be quietly restrained until muscular attendants from a psychopathic ward might arrive.

Even if the very happiest circumstance might be his good fortune and some super F.B.I. might have a glimmer of understanding and would set about investigating this menace to the world—or at least to American national survival in case that other race might snatch to accept this devilish cult of reason unchecked—this Sekten creature would presently inevitably tune in on their joint thought wave and would either coolly paralyze their cortices or would simply disintegrate himself and wish himself back to his accursed Epsilon to report that Earth was a succulent and well oxygenated planet full of helplessly disorganized racial herds waiting to be taken over at will. The doctor shuddered. Taken and herded by superior intelligence as men herded sheep.

WHAT was so heart-stopping and blood-chilling about this triumph of super

science was that, despite its physical frailty, it was impregnable to all

humanly devised means of assault.

Dr. Weiler left the bleating clamor of the herd behind and went into a delicatessen. He was more than ever convinced that he dared not turn this problem over to crude police methods. A dreadful reward of his own studies was that he had achieved some superiority over the general intelligence and that he would therefore have to pit his own puny mind against his omniscient creature who deigned in such friendly fashion to call him colleague and to devise some-means of murdering it before it might return to its atmosphere-starved homeland and project thence its nine million soulless immigrants to Earth. He shuddered to recall that Epsilon was the fifth letter of the Greek, the enkh of the Egyptians, key to all their pentagrammatic magics.

When he came back to his apartment Sekten was sitting as in a trance, oblivious for a moment to his entry. At that moment any one of the "stupid herd" who knew about guns could have done the deed and then— And then the doctor's heart heaved up to choke off his breath. Good heavens! IF one could accomplish the thing, what then? What, did one do with a corpse? What would a respectable psychology professor of a college tell the police about a body in a bedroom? Bitterly again he realized that any one of his pupils with their so deplorable literary tastes could give him lessons in the disposal of dead bodies.

Sekten shook himself out of his far-flung receptivity and tuned in on the nearer beam. He smiled with a genial satisfaction. "Refreshing," he said. ''Very refreshing. I have been listening in on some of those other racial groups whom I briefly contacted before. Receptive, I find them. Most receptive to advanced thought. And it seems that they have some considerable areas of undeveloped country where they could accommodate our mass immigration. Somewhat on the cold side apparently; but we have, of course, no difficulty in adjusting our metabolism to temperature."

Dr. Weiler did not have to ask what racial thought Sekten had been listening in on; and all the rest of the world knew how receptive they were to anything at all that would help their expansion.

But a thought was beating at his brain like a hammer blow. He cringed away from it in terror lest this inhuman receiver should hear it. It was in tense little gasps that his breath ventured back into his lungs as he saw that Sekten was sitting again with his eyes closed, attuned to those distant kilocycles more pleasing than the standard American waves. It seemed logical enough that when this machine was tuned on one wave it was not receptive to another. There were possibilities in that. Possibilities that might be worked out. Probably deadly life-giving possibilities.

Sekten came back from the far short waves to the immediate present. "Ah, I perceive you have brought sustenance. It will be interesting to explore into some of your Earth's flavors. We of course have practically no vegetable material and we have long ago eliminated oxygen breathing animals."

He ate nibblingly with a little bird appetite. His sparse frame required little fuel. What brain food, Dr. Weiler wondered did that oversize head need. "Chemical pills," Sekten answered the thought. "Though we do have fish of course."

DR. WEILER kept him talking, plying him with questions, forcing his own

dangerous thought about the wave lengths into the background. Sekten lectured

pontifically.

Fascinating flights they would have been in any other circumstances into the ultra evolution of Science. Sekten spoke about their efficient machinery for the extraction of diminishing oxygen from their atmosphere; about their control of their sparse rain, limited to one night a week between specified hours so that all outdoor arrangements could be made accordingly; about selection of their national leaders, not through popular votes of the herd but through rigid examination to prove fitness— "Thereby eliminating the curse of politics, you understand, and stimulating impetus to study." About state control of eugenic mating between the sexes, also through written and psychiatric examinations to determine compatibility— "Thereby eliminating divorce." And Sekten smiled amiably. "We shall teach the selected few of you all this when we come and reorganize what seems to be quite a stupid chaos here."

It seemed a pity, almost a sacrilege, to contemplate the murder of so friendly a bringer of scientific gifts. But then Sekten went on to lecture about medical advances; about the elimination of disease and consequent longevity— His own age he did not exactly know. Some couple of hundred years or so. It was unimportant. About, despite their careful selective breeding, the baffling persistence of recalcitrant genes that jumped over a generation or two and suddenly struck to produce cripples and unstable mentalities, "Which, of course, we in our desperate atmospheric deficiency cannot afford to maintain and must, ah, 'liquidate'" He loved his new word, and he quickly cocked his head at the doctor. "Which, as I say it, I perceive from you that the proportion of these non-producers in this country of yours is a most efficient drain upon your national economy. Most unscientifically unsound."

So then of course Dr. Weiler had to cram his surging thought back into the dark recesses of his mind and to ask more questions about anything at, all.

"And, er, when you sleep, does your receptivity function without your direct volition?"

"No, not actively. The tissues would exhaust themselves just as do your radio tubes; but there remains a subconscious alertness to danger or to any impulse, as we learned from the animals before we were compelled to disintegrate them. Which brings up the realization that I have had a—ha-ha—quite a long journey today and— Ah, your hospitable understanding, my dear Doctor, is admirable."

He had as ponderous a sense of humor as any other professor of science.

The product of coldly efficient scientific evolution accordingly slept securely in the spare bedroom, impregnable still, unapproachable, guarded by an alertness stolen from dumb animals. The while Dr. Weiler fearfully pondered whether he might permit his own mind now to continue its furtive excursion into some means of saving his way of life from efficiency's menace.

The super mind functioned, it was apparent, on the principle of a mechanical radio. Tuned to a certain beam, it did not receive the next, even though only a few vibration's apart. If then Dr. Weiler could contain his murder plans within some other wave length? He explored the possibility, shrinking up in his bed as he heart-stoppingly wondered whether that animal alertness in the next room might pick up a danger signal and he would be suddenly blasted by a retaliatory wave that would paralyze him, or immobilize him, or just disintegrate him away to a formless thought nucleus—make a homeless ghost of him. There seemed suddenly here an acceptable theory for the existence of ghosts. But the doctor resolutely shook the intriguing digression from himself; he had other more desperately important possibilities to consider.

THE trouble with planning a murder along lines of some different wave

length was that, after all, it would all be within his own beam; and if the

receiving brain were talking to him, listening in on him— "Damnation!"

Dr. Weiler's tenseness flared up to what he had always loftily derided as the

futility of swearing. There must be some way through this impregnable armor.

Perhaps Dr. Rhine with whom he had worked on extra-sensory perception might

be able to—but no. He could not dare to risk delay while he might

contact Dr. Rhine. This guest of his was too unpredictably dangerous. He

might at any moment decide to just wish himself out of here and into the

realm of those other minds whom he was already favourably looking upon as

better emotionally fitted to accept his scientific advancement than was the

current American mode of thought. By every means, then, the thing would, have

to be done now! Or at least tomorrow morning, before the danger might

with nonchalant ease escape.

If he could but think of some means of diverting the receptive vibrations—of distracting them—jamming the wave. Thank God his study had been what he had admired as the infinite processes of the mind. If this super-mind should have happened to swoop down on somebody else—some mere official, perhaps, of the national defense who could think only along lines of material explosives— But then there it was. Had it not been for his own teachings into the science of telekdelosis this monstrous peril would never have contacted Earth at all. Good God, what a fumbling thing was his mind science!

Dr. Weiler accordingly planned and plotted through the night. At intervals his whole being shrank itself down to hide, listening for a wakeful movement in the other room, expecting to feel himself dissolving away into nothingness. He hoped it would at least be painless.

Nothing happened. No paralysis, immobility. Morning came. Dr. Weiler had hatched a meager plan. By no means a fool-proof one; no more than a desperate hope that his theory of jamming the wave might distract that dreadful receptivity for long enough to— The man had told him that it took a few moments of concentrated thought to disintegrate a body. If he could not complete his murder within those few moments it would probably be his own body.

Not only in a few moments, but in the next few moments. Dr. Weiler in his ordered contemplative life had never been called upon to come to a decision and to act upon it so fast. He gulped dryly. He wished he had any one of his students here. In the matter of translating thought into action their reflexes excelled his by priceless seconds. Anyone of them could take gun or knife and kill him while his scientific mind was yet thinking about it. How fast could super science retaliate?

Sekten came to breakfast in a most genial mood and immediately confirmed the doctor's worst surmises. He sat down, sniffed exploratively at coffee, fingered the loaf of bread, his mind already occupied with the frightening thought.

"You know, my dear Doctor, I have been thinking quite a good deal about that other race of your Earth's. Their thought processes seem to run along lines more cooperative with our own than do yours. I am planning accordingly to go and—"

SO then it would have to be now! This monster might decide even before

tasting breakfast to disintegrate its frail body and giant brain and project

them with the speed of thought half-way round the world.

Dr. Weiler forced his thought into his mind. The plan of distracting the receptive mechanism. He had prepared it almost into a speech through the night. He could visualize the words.

The information you have, he compelled himself to think, is too valuable to be permitted to be given to any possible racial enemy. It will be necessary to put you into the hands of the security police for detention.

It was futile of course. Dr. Weiler knew well enough that science so advanced as this man's could shock the police into immobility, or at the man's callous pleasure into death. But it did impinge upon the receptive vibrations as a distraction. Sekten's great head perked up to look at the doctor, for a moment surprised, then derisively pitying.

"But my dear Doctor. Surely, after this even brief acquaintance, you do not underestimate my—"

Dr. Weiler forced himself to act on his deeper thought. To act without

thinking about it. He had schooled himself to the fearful thing all through the night. To perform a reflex action in response to a given stimuli.

He snatched up the bread knife and stabbed blindly at his guest. It was a weak stroke, ill delivered by an unmuscular arm, not even scientifically aimed. But it struck flesh and penetrated. A muscular man would have cursed it off and immediately slammed the assailant to the ground. But Sekten was even more scientifically frail than was Doctor Weiler. He jerked to a spasmodic scream.

"Why, you treacherous— I shall—"

Dr. Weiler stabbed madly again. He found himself brutally exulting to a realization that he was not suddenly shrinking away to nothing. It seemed possible that his puny mind had outwitted his semi-god of super mentality. He was conscious of blood red upon his white table cloth. Again he desperately poked the knife at the sagging little shape. No super-fantastic thing happened. No explosion. No crippling wave of mind force. The shape just sagged and moaned and sagged on down to the floor. Blood, not much of it, oozed from more holes in the body than Dr. Weiler knew he made.

Then he sagged himself. He flumped dizzily into a chair. Swallowing his heart down. Shuddering. Desperately clinging onto his mind to keep it from slipping into screaming hysteria. Even more desperately watching the frail little body for further movement, for any sign yet of life. No force that he knew of could make him go nearer and investigate to make sure. It was enough, and he gratefully thanked God for it, that he had had force of will enough to kill a man. He knew his moment of primitive man triumph. And why not? It was his muddling meddling into this telekdelosis theory that had opened the door for this monster. It was his responsibility to get rid of it and he had risen to the ordeal and done it.

And now there it was! His murder! It lay there. He looked at it and was fearfully glad. Only the killing of the thing could save the fumbling planet Earth from the emotionless domination that planet Epsilon would have brought. And nobody but himself, Dr. Weiler, student of mental projection, could have done it. He turned away, weak, trembling, eyes closed.

He went back wearily—it queerly shocked him—as he had heard that murderers did to the scene of their crime.

And there was no crumpled body there!

Dr. Weiler's breath rasped like a pneumonia in his throat. "God save us!" He stared at the place on the floor. There was nothing. Though yes, there was still the blood. On the table cloth too. The doctor looked around with a sudden apprehension. But no. No vengeful frail shape menaced him from behind. A worse fear assailed him. Had he entirely failed? Was the thing physically invulnerable too? But no again. Had it been, it would not have bled. Had there been just life enough, left to will the dematerialization vibrations and project itself back to its hideously scientific home and report that— But a third time no. That one would surely not report that Earth was a nice planet to colonize. Dr. Weiler permitted himself to suck in a long breath of hopeful relief.