RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror, March 1932,

with "The Case of the Sinister Shape"

DR. MUNCING stepped out of an early morning train in the chill, salty dawn of Ocean City and shivered with an ill premonition. He did not know why he had come. He had been planning to take a vacation somewhere else; but something had impelled him to change his plans and come to Ocean City instead. It was an uncomfortable urge of something pressing. Dr. Muncing shook himself and looked around him.

Solicitous hotel runners in gold-lettered caps recited the scenic and culinary merits of their respective hostelries. The doctor looked at them without the least interest, undecided.

A name caught his eye. Hotel Bathurst. The broad gold letters were just the slightest bit tarnished and the man the vaguest trifle less spruce than his rivals. But something made Dr. Muncing feel that Bathurst was the hotel he wanted.

Some thing again. The letters were all wrong. That "BA" combination, and the fourth letter "H," the eighth in the alphabet. He didn't like it. He didn't particularly like the strong impulse that attracted him to it.

It was not a comfortable impulse; not just a vague hunch. It was a distinct urge that impelled him, an insistent influence against his will that drew him on. A feeling wholly unpleasant. He might have resisted it of course. But much of Dr. Muncing's success in his work of battle against the more evil things of the borderland was of necessity a result of acting upon impulses. With quick decision he gave his bag to the man and followed him to the car.

Short questions during the drive elicited the information that the Bathurst was a hotel patronized mostly by the theatrical profession. None of that offered any clue to the impulse. Dr. Muncing wondered darkly.

THE premonition of unpleasantness received quick impetus

upon his arrival at the hotel. In spite of the early hour a

scurrying and a confusion was in the lobby. Bellhops hurried

aimlessly, doing nothing. A few wide-eyed guests, showing

evidences of having dressed hastily, whispered in groups.

Words such as "horrible ... fearsome ... the most frightful sound I ever heard in my life ..." passed in shuddering agreement.

A large, very blond lady behind the desk wrung her plump white hands distractedly and moaned:

"That it should happen in my house! My God, why must it happen to me?"

A car roared up to the door and a burly man with a brusque and officious manner entered.

"Where is it?" he asked importantly.

A dozen voices told him eagerly:

"Fourth floor. Room forty-eight."

Four and eight again. Dr. Muncing was always quick in decision. He stepped up to the man and handed him his card on which was inscribed, "Dr. Muncing, Exorcist."

The man glanced at it. The title, doctor, caught his eye. The last word was unfamiliar in his business of extracting the solid facts out of material mysteries; but this was no time to bother. He grunted satisfaction.

"Good. Better come along, Doc. I couldn't connect with our own man this early; had to leave a call for him. All right, boy; shoot her up."

ON the fourth floor frightened faces peered from

doorways. A woman huddled in a chair at the floor desk, rocking

with her head buried in her arms while her body shook in great

hysterical sobs. The elevator boy pointed dumbly in the direction

of room forty-eight.

The plainclothes man strode briskly down the corridor. Over his shoulder he said:

"Phone call said the whole floor was awakened by a frightful scream and the floor clerk rushed to the room and found a guy laid out all twisted on the bed. Something about a tall thin feller and the window too. Sounded foolish; but we'll get the woman in as soon as we've had a look around,"

While scared faces stared at him in horrid fascination he pushed open the door with professional callousness and entered, Dr. Muncing on his heels.

THE window shade kept the room unpleasantly gloomy; but

there was plenty enough light to see an emaciated figure in

pajamas on the bed, twisted, as the floor clerk said, in a

hideous contortion.

The detective grunted.

"Huh. Don't need a physician to tell me that this one is out. But look at him anyhow, Doc."

While Dr. Muncing made quick tests for any possible lingering life, the other with trained eyes took in all details of the room. He shot the window shade up with a whir and let in the early daylight. The window sash was open. The man leaned out and made critical note of the outside distances. He came back to the bed and looked at the body.

"What's the verdict, Doc?"

Dr. Muncing's face was darkly serious.

"Quite dead of course. There's not an external mark on him, but every bone in his body seems to be broken; smashed small from the inside."

THE detective scowled and his eyes swept the room rapidly

once more.

"Huh—that's a funny one. Not a mark on him; nothing upset; no furniture broken; no signs of a fight; nothing. A body tied in a knot like it had been done with a derrick, and an open window. But, what the heck, there's nothing human could get out there. Let's call that woman in."

Dr. Muncing nodded; but mechanically. He stood with head high, his strong black brows drawn together in a frown, nostrils wide and twitching, as though sniffing. He was feeling, sensing, trying desperately to catch some vague aura or impression that remained in the room. The impression was uncomfortable; more than that, evil and menacing.

He went to the window, as the detective had done, and looked out. The wall was sheer. No projections, no ledges or roofs. He measured with his eye the distances to adjoining windows. He drew his head in again, nodding darkly with thin lips sucked in a tight line.

Outside the door was the detective's voice, not unkind but determined.

"Come along, my girl. Nothing's going to hurt you. I don't want to make it hard; but, we've got to have your description. Hey, Doc; cover it up, will you? This dame's got the horrors."

He pushed the floor clerk before him.

"Now about this man you say you saw. Tell me exactly where and how he stood."

THE woman came in, twining convulsed fingers round a

moist handkerchief and biting her lip to control hysteria. She

cast a shuddering glance towards the bed; and, finding to her

relief that the twisted form upon it was decently covered, she

controlled herself sufficiently to stammer her tale.

"I—I was reading at the desk there—I wasn't asleep. Suddenly I heard the scream. It was—God have mercy, it was the most horrible noise I've ever dreamed in a nightmare. I ran to the door and knocked. There was no answer. I—the knob turned to my hand and I looked in, and—"

Shudders choked her words and she covered her face with her hands. Dr. Muncing quickly put his arm about her shoulders and spoke soothingly.

"Don't tell us about the man on the bed. Don't think of that. Just tell us about the other one."

The woman sensed protection in the muscular arm, and understanding in the voice. She got a grip on her nerves.

"He was—it wasn't quite daylight yet; the room was dim. All I could see was a very tall man—not his face. Only his shape—my God, his frightful shape. It was that that frightened me more than—than that other. I don't know why; but it was somehow horrible. Just the shape. Dark and thin and frightfully tall. He—it seemed to reach the window in one stride and it pulled aside the shade and stepped out. Just like that. All elbows and knees and then it was gone. Then I—I screamed and other people came from their rooms."

"Let's get this straight," snapped the detective. "Other people came. Did they come at once? They'd be witnesses that nobody came out of this room. That's important, because no human person could go out of that window. It would take an eight-foot man with a ten-foot reach to touch the next window sill. I tell you nothing human could get out of that window."

Dr. Muncing nodded.

"You are right, Officer. Nothing human. Still—" He pointed with his eyes at the shrouded huddle on the bed.

"I've got to look into rope-ladder possibilities; though I'd say that's out from the start. A rope against three floors of lower windows would make quite a racket. Still, that tied-up knot isn't normal. Something must have killed him."

Dr. Muncing nodded agreement again. Very softly and full of dark meaning, he said:

"You are very right again, Officer. Some thing quite surely killed him."

The detective looked at him, his eyes dilating.

"What d'you mean? What weird stuff are you driving at, Doc?"

Dr. Muncing shook his head.

"I don't know, Officer. I don't know—yet. There are more horrible things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in your police records. You go ahead on your own methods. I'd like to verify from your coroner's autopsy my opinion that there was nothing organically wrong with this man. Still, I'll bet that he has been sick for some days and I'll bet that his doctor has never found the trouble in all his medical books. I must go and see that man if I can possibly get his address from the office."

The detective scowled reflectively and lit a cigarette to conceal an uneasiness that came over him.

"You're a cheerful one, Doc, to have on a murder case. You give me the willies with your unholy talk. If this guy has had a doctor, like you say, I guess I'll come along with you and talk to him. I want to know what kind of sickness ties a man up into that kind of a knot."

THE physician who had been attending the sick man, a Dr.

Perkins, turned out to be an alert-eyed little man with the

inquiring manner and quick movements of a bird. He was

momentarily shocked to hear of his patient's horrible and sudden

death. Then he shrugged.

"I suppose one should call it a tragedy; but it was, after all, only a hastening of what seemed to be inevitable. Whatever was the matter with him was more than my poor skill could fathom."

"So I thought," said Dr. Muncing. "You found nothing organically wrong?"

"Nothing. Nothing at all. It was the most perplexing case of all my experience as a general practitioner. There was nothing wrong with the man; I'll stake my reputation on that. He was just wasting away and he responded to no treatment. Something was sapping his vitality."

Dr. Muncing assented soberly.

"Quite right, Doctor. Without any manner of doubt, some thing."

The detective exploded.

"There you go again, hinting at deviltries of some kind. Come across, Doc. What have you got up your sleeve? I'm not one of those know-it-all sleuths of the story magazines; I'm not above taking a hint from anybody. Let me in on your dope."

Doctor Muncing held up his hand. His compelling eyes held the detective.

"One minute, Sergeant. The doctor here has verified just what I guessed. Take the phone and verify one more guess, will you, while I ask the doctor a few more questions ; and then I'll tell you all I know. Call up the hotel and ask if there aren't some more sick people."

THE detective stepped into the hall where the telephone

was and the mumbling of his voice into the mouthpiece came to the

two men while Dr. Muncing asked questions. Suddenly the voice

came loud in a startled exclamation.

"By Cripes!" and then, "The hell you say!"

The man came back to stare at Dr. Muncing with dilated eyes. Thickly he said:

"You're a wizard, Doc. And there's hellishness afoot somewhere. There's two other sick ones; and neither do their doctors know what they've got. And there's a maid on the top floor out of her mind and moaning about a horrible tall dark thing."

Dr. Muncing sprang to his feet. Flinging a quick thanks to Dr. Perkins, he caught the detective by the arm and hurried him to the street. There he hailed a taxi and pushed the detective in. The latter obeyed without resistance; he was following a knowledge greater than his own. In the taxi Dr. Muncing rapidly explained to the bewildered detective the outlines of what he guessed and the rudiments of the darker mysteries of life. He found no difficulty in reducing many years of occult study in many countries down to a few lucid details. Muncing's work was so unusual and so few people knew anything about it, that he was constantly called upon to explain his science.

"WE have no time to go into history or abstruse

arguments," said Dr. Muncing. "You accept the findings of expert

criminologists as probable truth. You will take the word of

another detective on things that you may not be familiar with

yourself. Well, I am a ghost detective.

"No, don't interrupt. Let me tell you what I know; and later, perhaps—if we get out of this alive—we can argue.

"I don't have to tell you that what you call ghosts do exist. Most people—though they like to pooh-pooh such things—have an inherent feeling that they might meet a ghost some time in a dark place. You probably have your own superstitions.

"Well, they are not superstitions. They are hereditary memories. Our forefathers knew a great deal about spirit life that we have drowned in modern materialsm. Oriental people still know a great deal.

"What most people do not know is that there exist many distinct forms of spirit life and that they function each according to their attributes. Some forms are well-disposed to human life; some are harmless; some are malignant.

"We have to deal here with a malignant form. From its action I judge it to be an elemental. Elementals are primal earth forces—formless, eyeless, faceless. You will understand them perhaps by applying the great truth of evolution to all things. Elementals are spirit forms that have just not evolved at all. They exist, where shall I say? For want of a better word; they exist along with various other spirit forms on the other side of the veil that divides spirit from man.

"Sometimes it becomes possible for a spirit form to break through the veil and to manifest itself on the human plane. Never mind how they break through. They are attracted in various ways. In order to break through they must first be attracted by humans, consciously or unconsciously. The vibration theory may account for some. When they do break through we, in popular language, see a ghost.

"All elementals, possibly on account of their inferiority, hate humans who have progressed further in the scale of evolution. Having broken through into the human plane, an elemental must continue to draw sustenance from humans in order to continue to manifest. It can establish contact with some human who is sick, weak, whose power of resistance is at a low ebb. Thereafter it continues to draw vitality from its victim just as the vampire draws its sustenance in blood—till there is no vitality left.

"That in itself is bad enough. But the human victim, robbed of all vitality, does not quietly die, as do vampire victims. For the elemental, finding its victim useless, vents all its hate upon him by rending the last life from him with a vicious force, and then casts the twisted shell of what once was a man aside and turns to find another victim in a favorable condition of low resistance."

THE detective had listened with wide eyes, knuckles

showing white where his hands gripped his knee. These things

sounded fantastically impossible; but Dr. Muncing's cold

enunciation of them forced a reluctant belief in their gruesome

possibility. And there was the evidence of the broken, twisted

body and the telephone addenda from the hotel. All of them,

things normally inexplicable.

The detective drew a long, tremulous breath and then fired what he thought was a poser.

"If this thing is a spook—which I don't admit yet—what brought it here? I thought that spooks hung around in old houses; monasteries and such like places where there'd been murders."

Dr. Muncing was able to laugh happily.

"There you are. Your own established superstitions. Why do you believe that? Because your forefathers knew it; because it is history; because people still know it. But make no mistake. While some forms of spirit life are attracted to their associations in old houses, others — elementals — are attracted directly to humans; they can fasten on to them wherever they may live."

The doctor had a desperately logical answer to every doubt. The detective propounded another—not a doubt this time; a question looking for information.

"And this spook thing, can it hurt other people, too; people who aren't sick? Us?"

Dr. Muncing nodded seriously.

"Under the right conditions, yes. Conditions in the Bathurst are right. If it has established contact with three victims its power may be immense."

"What do you figure brought it to the Bathurst?"

"I don't know," replied the doctor. "Maybe the number combinations of its name opened the way. There are deeps in numerology that no man has fathomed. Maybe its victim did or thought or possessed some luckless thing, to attract it. Maybe just the fact that there were three prospects whose physical vibrations provided the right sort of non-resistance was sufficient.

"These are things that I do not know. I can do no more than guess in the dark. I do not know how this malignant entity was able to exert some queer force that impelled me, personally, to come here. But from that I deduce that I have had contact with this elemental evil before. It has reason to hate me more than all other humans; and it has drawn me to this place because it feels it has contacted with something or other, with some new power, that will enable it to destroy me. I don't know yet what this power may be or just how the thing has been able to exert it from a distance. But I feel positive that the whole plan of campaign is aimed at me."

THE doctor stated his case with cold conviction. No

exaggeration, no assumption of knowledge that he did not possess,

no heroics. Here was something at last that the detective could

understand. A force for evil directed deliberately against an

individual who stood for law and order. It was a condition that

he himself had faced many a time. And the doctor faced the

condition calmly, without hint of hesitation just as any officer

of the law might.

There was inspiration in that attitude. The detective braced himself. It had been the dark unknown that had seemed so horrible. Now he felt that he knew quite a good deal about the ways of spooks. He shrugged

"Well, it sounds like a lot of hooey to me, Doc. But you got your nerve all right. And I'm assigned to clear up this murder. So I'll throw in with you. Let me just phone headquarters to send a man to look up marks around the window and fingerprints; and then we'll take a look at this maid that's gone queer on the top floor."

UPON arrival at the hotel they found a physician already

in attendance upon the maid. She had been moved to a bed in a

vacant room, and there she lay in a state of collapse, moaning

incoherent things and rolling staring eyes that saw nothing.

The physician was quite at a loss. "There's not a thing the matter with the girl," he told them. "No hurt of any kind. But there seems to be some awful fright. All she does is mutter something about a horrible shape."

Dr. Muncing nodded. "Do what you can. We'll be back."

He drew the detective away.

"There'll be attics above this top floor; trap-door entrances. That's where we must look. And listen— get this very straight because you'll need to know just what you are up against. This is no empty shadow that groans and rattles chains. It has drawn human vitality sufficient to materialize in exaggerated resemblance to the human form from which it has taken that vitality. By the process of multiplication of energy known to all spirit forms it has built up that energy to a force sufficient to tear you and me apart. Few spirit forms can face bright light. Therefore this thing will be lurking through the day in dark places--attics."

The detective heaved up his shoulders in a great shrug.

"If I believed the half of what you told me, Doc, I'd be taking cover faster than from a crook gang with machine guns. But I'm with you; so you know just about what I think."

AT the end of that long hallway, rungs let into the wall

led to a square trap above. Dr. Muncing, with a grim little

smile, waited. The detective was quick to catch on to his motive.

He grinned at him.

"You haven't got me scared yet, buddy," he grunted; and he slowly climbed the ladder. With a thrust of his burly shoulders he flung the trap door back and disappeared into the gloomy hole.

Dr. Muncing deliberately waited below. He heard the man's heavy footsteps move in a small circle above. Still he waited. It was being alone in the dark that tried a man's unbelief in ghosts. Suddenly the detective's voice came.

"Doc. Hey Doc."

Within the second it came again; urgent, anxious.

"Hey Doc. Come on up!"

In a flash Dr. Muncing was up the ladder and beside the man. It was he who was grinning now, though rather thinly and without mirth.

The detective drew a shaky breath. His face was sheepish and had by this time lost all of its gruff assurance.

"By golly I—I guess I'm a fool. For a minute there I was getting rattled. But—there's something up here, Doc."

Dr. Muncing laughed shortly.

"So? You felt it, did you?"

"Felt what?" The detective was boldly positive again. "If I'd felt anything I'd have taken a crack at it. What d'you think I felt?"

Dr. Muncing was grimly uncompromising.

"Fear," he said. "Just the first swift stab of it—and you haven't seen the thing yet. I told you fear was one of its attributes. You'll have to hold your nerve with an iron grip because this thing knows how to wrench out the very roots of fear."

The detective's voice came very soberly.

"By golly, Doc, you've almost got me believing you. There was something getting my goat. But—I'm with you."

"Good man," said Dr. Muncing. "Let's take a look around."

The attic space in which they stood was a long, wide barrack of a place. Dim light filtered through a cobwebby louver opening. Ghostly gray BX electric cable wandered snakily over the open ceiling beams. The peaked roof shingles were lost in the gloom above. Only a track of three planks made walking space down the middle of the empty area. A false step on either side and one's foot would plunge through the ceiling of the room below.

At the far end another dim ventilation louver showed that the attic extended on both sides. Apparently it was all like that, a dusty, musty, emptiness of king-posts and cross-beams that covered the whole building, which was constructed with wings and a center, like a letter E.

"Helluva place to go spook hunting!" grumbled the detective with an attempt at jocularity to keep up his spirit.

Dr. Muncing said nothing, but advanced slowly, the detective as close to his side as the narrow plank track would allow. In the gloomier central portion barely lit from the dim ends the doctor was very cautious. A faint metallic clink in his pocket told that he had handled something. If overwrought imaginations were not building figments out of nothing, soft echoes and vague scuffling noises indicated that something was moving somewhere.

"We've got to be sure," said the doctor, "that it is up here and that it is It."

They advanced together cautiously. Arrived at the end, the detective fastened a spasmodic grip on the doctor's arm.

"There! By God, I'll swear I saw something duck round the far corner."

"Come on," said the doctor shortly.

BOTH men felt a tingling of their skin as they started

forward. The detective pressed on. Having seen something, all his

training as a man-hunter came to the fore. He reached that corner

ahead of the doctor. With a sudden shout he snatched his pistol

and fired into the further darkness.

Nothing happened. Then in a few seconds—almost as though it were a foul odor given off by some beast of the skunk family—a hot wave of hate swept back and eddied round them. It was a sensation almost solid. They could feel the furious malice of the thing. A chill ran along the detective's spine.

"That was foolish," said Dr. Muncing quietly. "You can't shoot a ghost. But I knew you had your gun; otherwise I would never have brought you up here."

"God of Heaven!" breathed the detective. "I take it all back, Doc. I don't know what I saw, but it was a long and a fearful shape of something. And what use is a gun then, if you can't shoot a thing like that?"

Dr. Muncing nodded. He spoke with ominous seriousness.

"The sinister shape that frightened the women to hysteria. You're beginning to believe, yes? But listen now again. You've got to know this. It is a law of the universe that to every natural ill Nature has provided an antidote. We don't know all the antidotes; but science is continually finding more of them.

"There are repellants as well as attractions for all spirit forms. The old-timers practised a mumbo-jumbo and called it magic. Rubbish. There is no such thing as magic. They knew some of the rules, that's all.

"The repellant for an elemental is—cold iron. I don't know why. But it has been known for all the ages. The amulets of all oriental peoples—who know a lot more than we do—are made of cold iron. Your lucky horse shoe is cold iron. The material of which your gun is made is a thousand times better safeguard here than all your bullets. Better still is natural iron; the antidote to the primal earth spirit as Nature primally made it. Best of all, because of its purest natural form, is meteorite iron. An elemental can approach cold iron only in circumstances of extraordinary power. Now come ahead."

QUICKLY they traversed that passage and came to what

would correspond to the lower arm of the E. A blind passage. If

the thing were here at all they had it cornered.

"It can't go through that ventilation louver," whispered Dr. Muncing. "I mean, it could squeeze through the slats, but it can't face daylight. Come on."

It was a foolish, in fact a quite stupid, advance to make, as Dr. Muncing perfectly well recognized afterwards. That louver was particularly cobwebby and dim. The corner was dark. The elemental malignance had been drawing power from no less than three sick persons. And lastly—a law which the doctor well knew—anything cornered instantly builds up a psychological increase of power.

With perfectly insane recklessness, however, he advanced along the narrow plank track, over the open ceiling beams, the detective, sublime in his ignorance, with him.

Like an offensive odor again heavy hate assailed them. Tangible, almost stifling. The gloom in the far corner became gloomier. Long, black shadows of beams threw patterns. If the thing were there it was indistinguishable amongst the other shadows.

Under ordinary circumstances Dr. Muncing would have taken warning right there. The sheer overwhelming force of the hate projection was evidence of the power that the thing had been able to gather to itself. But in some amazing manner he seemed to have lost all caution. Not only caution but simple common sense was lacking. The detective, bold in his ignorance, followed the lead of the expert. But he felt the menace of the thing.

"By God," he muttered hoarsely. "I'll swear it's getting darker."

And it was. A blackness in the corner thickened and seemed to bulge out at them. Malignance, almost triumphal, swirled about them. Then fear in a sudden rush clutched at their senses. Like an animate intelligence tearing to break down their resistance.

AT that at last Dr. Muncing felt that he had come too

far; that he had pitted himself against a condition of power far

greater than he had realized. He knew that he had come just where

the thing wanted him.

A desperate thought of retreat came to him. But it was a long passage back over the narrow and insecure planks. Then fear in an overwhelming surge tore his grip of himself to shreds of frazzled, screaming nerves. A choked cry of hideous panic came from the detective. And with it the horror broke upon them.

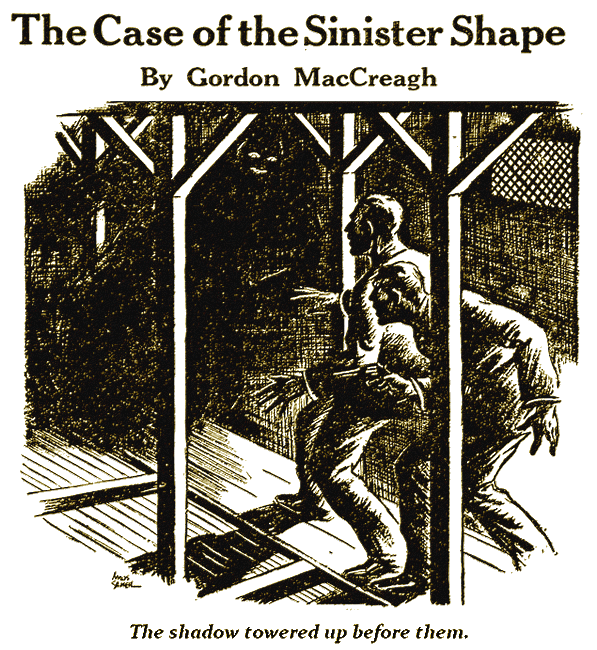

The shadow towered up before them. A palpable, monstrous, deformed thing. An inhuman noise issued from it; a ululation of hell's triumph. The unleashed malignance of all the ages enveloped them.

And the thing launched itself at them.

Both men agreed afterwards that at that moment they saw their own spirits apart from themselves, torn from them and whirled in a strong wind.

The detective's shout was a strangled groan. With desperate effort he hurled himself aside—any side, anywhere. His heavy body struck violently against the doctor.

Together the two bodies came down. There was a smashing sound. Wood splintered. Plaster cracked. The bright light of God's good day broke blindingly upon them. A short, swift descent, and a thud. They had smashed through the lath and plaster ceiling into the room below.

Above them, through the jagged hole, sounded a noise like beasts snarling in rage. Angular concentrates of darkness moved furiously in the gloom, as though long arms struggled to reach them; the more furious because they could not face the bright light. Like a stench again, consuming hate settled down upon them. Then slowly the malignance ebbed from the opening.

BOTH men were badly shaken. Death had been terrifyingly

close to them. They were bruised and the breath had been knocked

out of them. But their shock was mental much more than physical.

The terror of that primal evil in the thick dark still shook

them.

The room through the ceiling of which they had mercifully broken happened to be untenanted. Dr. Muncing pulled himself together with a strong effort. He dragged himself to the plaster-littered bed and sat with his head in his hands. With the sudden fall and the plunge into bright daylight, common sense had come back to him. The thread of some queer influence had snapped. His mind grappled with the phenomenon of his so nearly fatal stupidity.

"How could it do it?" he kept asking. "I should have known—I did know, that it had a tremendous store of power. I knew that conditions were just right for it. What lunacy made me walk right into its trap? How did it influence me to come here in the first place? An elemental in itself is of too low an order of intelligence to influence the human mind. That rule is absolute. What new and deadly trick is this?"

The detective was concerned with a more practical aspect of the case. His heavy, ruddy face was white and great drops of perspiration clung to his forehead.

"Blessed saints!" he kept muttering. "Holy Mother! I don't know what I've seen nor what black section of hell has broken out and come to this house. But God help us, what's to do? What can mortal man do against a thing like that? Fifty cops couldn't fight that thing. Save us, is it safe anyway to sit under that hole where it can look at us?"

DR. MUNCING shook himself out of his uneasy consideration

upon the new menace of mental influence. The detective was right.

Practical considerations were paramount. Precautions had to be

taken.

"It can't come at us in the light," he assured the detective. "All the police in the world wouldn't be any good. They might be able to chase it out of here. But it would be loose somewhere else in the world and would find another victim. We can't destroy it. It is a spirit form and so cannot be killed."

"Holy Mother!" The awf ulness of that thought shook the detective. "Is it a piece of everlasting hell itself? What can we do?"

"The only thing we can do is to starve it. By a merciful dispensation of Providence the thing has its limitations. It has made its contacts and has materialized. In order to continue to manifest on this material plane it must continue to draw energy from its victims. It must eat.

"We must cut off its supply. We must protect its two remaining victims from further drain upon their vitality—by cold iron on their persons; and their rooms must be kept brilliantly lit throughout the night. We must bar all exits to the attic with cold iron; the louver openings; everything. That won't be difficult. Stove lids, gas piping, anything will do.

"Fortunately the thing cannot easily break through the natural resistance of people who are not sick, whose vitality is strong. In fact it seems that there are only certain people whose vital vibrations are right for it; with whom it can establish contact. Every day—or rather night—that it cannot renew its supply of human vitality it grows weaker. Till shortly it will not have power enough to materialize at all. It will be forced back to spirit form, to the limbo from which it came.

"That is the only way we can deal with it. We must so deal with it. Otherwise it will remain a curse at large in the world."

WITH a material job in hand the detective was full of

energy. Full, too, of an almost religious obsession as to the

need of driving this unholy thing back to the nether pit.

"I'll fix that end of it, Doc," he declared with a crusader's spirit. "Leave it to me. I'll have those trap-doors and things fixed up in no time. No need to tell the hotel folks what it's all about. I'll just say the police are in charge."

"By no means tell anybody," said the doctor. "Fear engenders vibrations favorable to occult forces. I shall go and see these two sick people and try to make them understand what we want to do without scaring them."

At the hotel desk the doctor inquired for particulars about the two sick people who were so mysteriously ill. The large blond lady gave garrulous details.

There was Mr. Beckett in room sixty-two who had the snappiest monologue act in vaudeville. A fine, generous gentleman he was too; and it was a shame and a disgrace that the doctors who took his good money couldn't even tell him what was wrong with him.

And there was Mr. Lubine in nineteen who used to play the two-a-day; but there was not much call for his specialty these days, and he was reduced to a come-on booth at the beach. A hypnotist he was and one of the best in—

"What? What's that?"

Dr. Muncing's sudden shout startled the lady back to her tremulous condition of the early morning. Her nerves were in no condition to bear another shock.

"A hypnotist, you say? God of everlasting wonders! What cunning guile is this?"

HE hurried from the desk muttering, leaving the lady to

gaze tearfully after him. A hypnotist? So that was how it was

done? The malignant thing, absorbing with the man's vitality a

portion of his attributes, had been able to project a hypnotic

suggestion to its enemy. Dr. Muncing was sure now that this was

the same elemental evil that he had combatted before. On that

occasion owing to the stupidity of others, the elemental had won;

the doctor had failed to starve it out. Now it knew the danger of

the doctor's profound knowledge, just as a criminal knows and

fears the danger of a clever detective.

Dr. Muncing smiled a tight and very crooked smile. So that was how the thing had been able to influence his mind and had lured him here where it had no less than three coincidental sources of power. That was how it had fooled him into advancing into its lair in the face of conditions that all his knowledge told him were in its favor.

Dr. Muncing whistled and wiped his brow. What an insidious and deadly danger that was! His lips set in a hard line. He would not be caught with that trick again. And he must immediately warn the detective against that sly menace.

Together they made the rounds of the top-floor halls. The various trap-doors had been guarded with immense quantities of iron. Hardware of all kinds had been nailed, screwed, or attached by cords, as conditions permitted, to every possible outlet. From outside, festoons of gas pipe hung over the ventilation louver.

"And we've shoved nails and stove bolts into the mouse-holes," said the detective with an official pride in his thoroughness.

DR. MUNCING told him that an elemental was no such

attenuated thing that it could ooze through a mouse-hole. It was

a material body capable of doing material harm. They went to the

patients' rooms and immunized those.

Inventing a story about a prowling gang of burglars, Dr. Muncing instructed them about keeping doors and windows closed and lights burning bright. Over the brass hardware of the doors he hung packets of meteoric iron.

"To-morrow," he said to the detective, "we shall know whether we have missed anything. If the patients look better it will be proof that we are being successful. If they are worse—"

"Don't worry that I've overlooked anything," the detective interrupted. "If that devil spawn is anything bigger than an ant we've got him bottled in the attic."

In spite of which boast, a furious knocking woke the doctor with the first streaks of dawn, and a white-faced boy brought a story that a watchman had seen a long, dark figure skulking up a staircase.

Muncing immediately investigated in company with the detective and discovered that the ironware about one of the trap-doors had been removed and stacked neatly in a corner.

"What the hell!" swore the detective. "I thought you said it couldn't touch iron."

But Dr. Muncing with a very serious expression continued his inquiries. They elicited the information that a hotel employee on one of the upper floors had moved them. He appeared to be hazy in his recollection of just why he had done so. He supposed that probably they must have looked unnecessary, as well as untidy.

The furious detective would have struck the bewildered employee. But Dr. Muncing held his hand.

"Remember," he told him meaningly. "It hypnotized us to follow it right into its den."

The detective's hand dropped. Amazement and awe were in his expression.

"Holy Saints! If it can do that against our precautions— Do you think it got at the sick ones again?"

"Come on," snapped the doctor, A hurried call at number sixty- two disclosed that everything was intact and that Mr. Becket had slept well and looked refreshed.

But the report from number nineteen was not so reassuring.

Mr. Lubine lay in his bed, completely exhausted. And his window that had been so carefully protected was wide open.

Tactful, painstaking inquiry disclosed that he had been unable to sleep, it had been hot. So he had opened the window for fresh air and had turned out the glaring lights.

Dr. Muncing drew the detective out of the room. His manner was very troubled.

"There are times," he murmured, "when I almost believe in a personal devil. What a diabolic jest upon life! Hypnotizing the hypnotist with his own medicine!"

"God of Mercy," groaned the detective. "What can we ever do against that damnable trick?"

"Nothing," said Dr. Muncing with flat conviction. "Nothing at all. I had hoped to starve this thing out. But as long as that man lives it will always be able to influence somebody to leave a loop-hole somewhere. His hypnotic art is his own death sentence. We can only hope that he does not live too long."

The detective stared at him with big eyes as he assimilated the helplessness of that thought.

THREE days of watching and futile precautions passed.

Always somebody somewhere was insidiously impelled to remove some

carefully-built barrier of cold iron. The doomed hypnotist grew

horribly weaker. And then, one day just before the dawn that

frightful, soul-searing scream rang throught the hotel once

more.

The detective and Dr. Muncing almost collided with each other at the door of number nineteen. Together they tore it open and dashed in. But only to verify what they already knew.

The body of the wretched hypnotist lay distorted in a gruesome contortion.

The detective, in spite of his anticipation of the tragedy, was stunned by the hideous inevitability of it. But Dr. Muncing was full of grim energy. His strong nostrils quivered with the prospect of encounter and a tight smile pinched his lips.

"S-ss-so," he hissed very softly. "The thing has been foolish enough to kill its source of supply. It has perhaps learned enough to circumvent our barriers. But"—he nodded very purposefully—"perhaps now we can trap it."

The detective stared at him.

"What do you mean, trap it? You're not going to try and catch that thing? And you can't kill it, you told me."

GRIMLY Dr. Muncing expounded the law.

"Every spirit form can be exorcised—if you know how. Every ghost, as you would put it, can disappear. A spirit form may disintegrate itself voluntarily. Or—if one has the knowledge and the necessary courage—conditions may be made so unpleasant for it that it disintegrates itself back to the fourth dimension. If we can catch our elemental and force it to dematerialize, it is right back where it came from—beyond the veil once more. A completely new set of conditions must be found in order to let it break through again."

"How?" was all that the detective said through set teeth.

Dr. Muncing was deadly deliberate.

"Have you got plenty of plain guts? I mean, nerve enough to meet this thing in a locked room? But I know you have. You'll see it through with me? Live or die?"

The detective's eyes were held by the doctor's compelling stare.

Slowly he nodded. Dr. Muncing held out his hand.

"Good man. Listen then. This thing has a low grade of intelligence. To-night it will try to get into the other sick man's room. Well, we'll leave the road open—and you, my nervy friend, and I, we shall be waiting for it!"

Like steam slowly escaping the breath came heavily through the detective's nose. But his eyes remained fixed on Dr. Muncing's. His jaw muscles swelled over gritted teeth. He nodded.

"Good man," said Dr. Muncing tersely again. "Go ahead and arrange about having the patient moved into another room, and hang all the iron in the house around it. I've got some preparations to make yet. I've been getting ready for this for the last three days. I've got a long session now with a carpenter and an electrician. Probably a blacksmith, too. See you at ten o'clock to-night."

FOR the detective it was an awful day of foreboding and

gloomy conjecture. A day that dragged its minutes into

interminable hours. Fearsome though the thought was of facing the

elemental thing, he welcomed each new hour that led on to the

evening as being one hour the less to wait in suspense.

Not a minute before ten P.M. did Dr. Muncing show up. He was tense.

"Come on," he said shortly. "They turn off the main lights here at ten. We want to be in position right away."

The sick man's room was stuffy with recent occupancy and want of air. Dr. Muncing's first act was to throw the window up to its fullest extent. The detective breathed like a nervous horse, but said nothing. Laconically, Dr. Muncing outlined his plans.

"I've been having a surprise built here for the thing. That will give us an advantage—and let me tell you, we'll need it. We must just sit tight in the dark till it comes. Chairs in the corner farthest from window and bed. Not a peep, not a sound to warn it. And then, if it comes, it'll be it or us."

THE detective never knew whether minutes or hours or days

passed. Time was an interminable ache of apprehension.

Comfortable human noises in the hotel ceased. Unfamiliar noises

shuffled and whispered down passages. Probably humans

too—or mice. But the detective quivered at each one. Faint

clicks came from without the window. Insects or summer bats. The

detective groped for Dr. Muncing's arm in the dark.

The doctor leaned softly over to whisper reassurance.

"Don't bother about noises. It will be as silent as a ghost when it comes; and then whatever happens will happen fast. Hold your nerve for that minute; and then, whatever happens, don't let the iron amulet out of your hands."

BLACK eternity passed again. Suddenly both men drew a

sharp breath at the same time. There had been no sound; but a

roundish object the size of a grapefruit was dimly outlined above

the window-sill. For minutes it stayed as motionless as a lurking

animal. A formless, indistinguishable shape; a blur in the outer

darkness.

At last it moved. It rose above the sill. An extraordinarily long angle of a raggy elbow heaved up from below. A gaunt shoulder followed; and then another fantastic elbow. There the thing hung in grotesque silhouette. The grapefruit thing was obviously its deformed head. It turned as though listening.

The detective experienced the same cold fear that he had at his first meeting with the thing in the attic; and again, almost as an animal odor, the sense of hate wafted into the room.

His grip closed hard on Dr. Muncing's arm. Its rocklike steadiness reassured him.

Slowly, with infinite caution the shadow drew itself over the sill; all long raggedy arms and abnormally attenuated legs. Now it stood wholly within the room; a shadow against the outer dimness, deformed, grotesque, immense.

Then things happened fast. Dr. Muncing stretched out a cautious arm and pressed a button. With a rasp and a heavy metallic clang a sliding shutter slammed down into its groove, cutting off even the dim square of outside night. The room was in black darkness.

A snarling squealy noise sounded by the bed. A choked "My God" from the detective. Then a click; a familiar sputter; and a blaze of light from a powerful theater arc lamp.

Crouching in sudden afright the sinister shape loomed enormous in all its exaggerated deformity; menacing in spite of its startled surprise. But it was to the face of the thing that the eyes of both men were attracted. A faceless face. A smudge. A smear of moldy, doughy substance. Shapeless, shrunken, incredibly evil. Yet there were eyes; dead slaty gray with darker diagonal slits of irises; and a frothy gash of a mouth. A formless face of fear and of unbelievable fury.

A SOUND of rage issued from the mouth and the Thing

hurled itself at the window through which it had come. In the

same movement, like an animal arresting its leap in mid-air, it

shrank from the iron sheet that had clanged into place. With

inhuman speed, snarling as it twisted, it changed its leap into a

plunge across the room and lunged an abnormally attenuated arm at

the arc lamp.

There was a crash, a tinkle of smashed carbon rods, and the room was blotted into black darkness once more.

Out of the dark came a roaring noise, an incoherent howl of triumph. The detective felt himself whirled off his feet into the air by an irresistible force. He commended his soul to God.

Then, mercifully, there was a sputtering noise and a spurt of blue flame. Another arc blazed bright. A sputter, once more. Another. Again another. The room was flooded with light that hurt the eyes.

The detective found himself on the floor. Vaguely he was conscious of Dr. Muncing shielding his eyes from the glare and advancing with incredible courage against a shapeless blackness that condensed in a corner, holding in his hands a queer, five- sided emblem of iron.

From it and from the blinding lights the black shadow shrank. Farther into the corner and yet farther. The lights seemed to penetrate it, to eat it up. Its solid blackness paled. It thinned out. The baseboard was visible through it; the pattern of the wall paper.

Presently there was no shadow. Nothing. Only a stifling odor of baffled hate.

Dr. Muncing advanced resolutely into the corner. He pressed his pentagon of iron into the farthest nook. There he left it and he came to lift the detective to his feet. Great beads of perspiration stood on his forehead. His strong hands were trembling. He hid his own agitation under a cover of brusqueness.

"What in thunder did you do with the iron amulet I told you not to let out of your hand? Dropped it to reach for your gun, huh? You poor fool, you've been nearer to horrible death than you'll ever be able to understand."

The detective was not resentful at this.

"Is—is it gone?" was all he wanted to know.

Very slowly and very soberly Dr. Muncing nodded.

"By the grace of God, yes. And by the grace of God again, the conditions that allow a thing like that to break through into the human world come, very fortunately, seldom. This elemental evil is exorcised. Or, as you will tell the tale to your unbelieving fellows, this ghost is laid."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.