RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

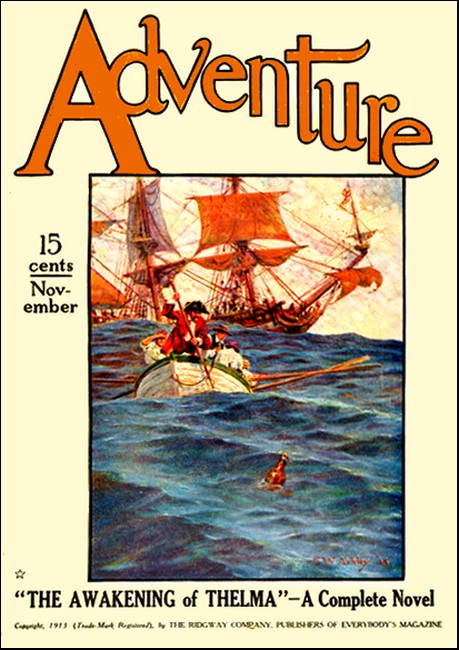

Adventure, November 1913, with "The Taking of Boh Na-Ghee"

THE Commissioner of Tuktoo Division sat in his office frowning over a letter bearing the lion and unicorn crest in red relief. He read it over again. There was no doubt of it; censure was clearly implied in the ponderous verbiage of the Burma Government. It ran:

To the Commissioner, Tuktoo Division.

Sir:—

I am desired to acknowledge the receipt of your report on the death of Mr. E.W. Baker, Superintendent of Police in your Division. His Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor desires me to call your special attention to the fact that this constitutes the second European murder attributed to Boh Na-Ghee in your district during the short space of two months, and to say that be confidently looks to you to see that it shall be the last.

To this end Mr. T. O'Neil has been provisionally gazetted to the vacancy. This officer is rather young to bold such an appointment, but His Excellency bas confidence in his ability; nevertheless he wishes you to understand that he is strictly on probation, and that his confirmation in the appointment will depend entirely on your report as to his fitness.

Your most obedient servant, E. Chalmers,

Secretary to H.E. the L.-G.

The Commissioner muttered an impatient exclamation.

"Hang it all, does he think that I can charm my people against rifle bullets?" he grumbled.

Then, feeling the need of sympathy, he went into the room where his assistant sat.

"Read that," he grunted, throwing the letter on the table.

The assistant skimmed through it.

"Who is this O'Neil?" he asked. "What does he do?"

This was the first and invariable inquiry of a newcomer. To these men exiled in the outposts of civilization the vitally interesting point about a stranger was the extent to which he could contribute to the social life of the little community.

"Do!" returned the Commissioner. "He does nothing. He is the man who said that life in a district station consists of work and the three B's, and that the two can't go together."

"Sounds pretty epigrammatic," said the younger man. "What does he mean?"

"Bridge, Booze, and Billiards. But if he brings those ideas up here I shall have to report unfavorably; we can't afford to have a deadhead in a small station like this, even if he is a smart officer. Well, I hope he'll enjoy hunting the Boh."

The assistant smiled grimly.

"The Boh doesn't usually wait to be hunted—he hunts."

"Well, the L.-G. has confidence in his ability," quoted the Commissioner. "Hope he deserves it. By the way, you might file the letter personally, as it's confidential; though what use a confidential letter can be in an office full of native clerks is beyond me."

The Commissioner spoke from long experience. Though the letter arrived sealed and ostensibly unopened, he was quite sure that its contents were even then being whispered about his office.

BY early sunrise Boh Na-Ghee was listening to a message to the effect that one O'Neil, who had had much experience in the Chindwin District with dacoits had been ordered to Tuktoo for the special purpose of running him down with his whole gang.

The Boh laughed uproariously and with genuine glee. Then, "Listen," said he. "Let it be reported to me without fail when this hunter of men arrives, and I will send him a messenger with a message of greeting."

THREE days later a card was brought in to the Commissioner— "T. O'Neil."

"The sahib waits without," said the orderly.

"Give him my salaam," ordered the Commissioner, and turned again to his occupation of hurriedly scribbling orders on the margins of a pile of correspondence before him. On finishing, he rang the bell on the table impatiently.

"Well, didn't you tell the sahib I was ready to see him?" he demanded without looking up.

"I'm sorry," said a deep voice behind him. "Perhaps I should have knocked."

The Commissioner wheeled in quick astonishment and beheld a broad-built, bronzed figure of medium height, with an expressionless face which looked as if it had been carved out of tough wood by some skilled craftsman.

"I beg your pardon," he apologized. "I don't know how you ever came in without my hearing you."

The ghost of a smile flickered behind the steely gray eyes for a moment and went out again without a muscle in the rest of the face moving.

"Take a seat," continued the Commissioner. "I hadn't expected you for two or three days yet. How on earth did you get here so soon? It's three days from Kindat down the river and another two by rail."

"Oh, I came in over the mountains with my orderly," explained O'Neil. "Of course, I sent my baggage by the ordinary way. You see," he continued, "I thought it would be a good opportunity to get acquainted with the country, especially as my duties will lie chiefly there."

"But, man alive," protested the Commissioner, "the mountains simply swarm with the Boh's friends. Nobody goes there without an escort."

"Yes, so I was told," said O'Neil simply. "But we weren't seen. My orderly's a Gurkha from Nepal, and a good woodsman."

The Commissioner just gazed at him in wonder. His heart had sunk at the grim appearance of his new Police Superintendent, but there was something about this keen-eyed young man that brought a feeling of deep comfort as he thought of the lieutenant-governor's letter, and recollected that the power behind the throne, on whom his own position depended, "confidently looked to him" to see that the Boh's latest depredation should be his last.

Then the sacred laws of hospitality, which are held in high reverence by white men who live in the far corners of the earth, claimed his attention; and, putting aside his personal feelings, he turned to the other with a smile of well-simulated cordiality.

"Well, look here," he invited. "If your baggage hasn't arrived, I'm sure my wife will be very pleased to put you up for a couple of days till you can-settle down."

"You're really very kind," murmured O'Neil; "and I can only accept your offer with the deepest gratitude. It will save me a great deal of trouble."

"Don't mention it, my boy, don't mention it; I could do no less. And I'll have Travers over to dinner this evening—he's your assistant, you know. I'll have him come early, and we can tell you something about your duties. By the way, I suppose you've brought a dress suit?"

"Of course," replied O'Neil. He knew that according to the snobbish conventions of district official life a dress suit was far more important than a knowledge of one's duties.

DINNER was over. The Commissioner's wife had retired to the "drawing-room," leaving the three men to their whisky-pegs and cigars. This was the period for relaxation from the stiff formality of the meal. The men assumed comfortable attitudes, and the talk turned, of course, on shop.

There are only two subjects for conversation in the jungles; work, and the doings of one's neighbors. It was rather too early for scandal yet, so the Commissioner was describing his new district to O'Neil, while Travers interpolated useful scraps of information about the people and their peculiarities. O'Neil listened silently, turning his keen eyes from one to the other.

Of course, the Boh loomed large in the foreground.

"You'll find your work cut out for you, O'Neil," the Commissioner was saying. "This Na-Ghee isn't an ordinary market-cart robber; he's a daring leader with a considerable gang. And he has pulled off some very cunning coups. I suppose you heard how poor Baker went out?"

O'Neil shook his head.

"Well, Na-Ghee planned to rob a native jeweler in a little village about eight miles from here, and arranged that Baker should get the information a couple of hours in advance. Baker raced off with a few of his men, and ran slap into an ambush. He was dropped dead with four of his fellows, and, of course, the rest bolted; after which the Boh went calmly ahead and looted the jeweler as arranged.

"Travers went out and chased him all round the country, but what the devil could he do, with half the villagers in Na-Ghee's pay carrying him information? Tell him about it, Travers."

Travers had tilted his chair back and was blowing contemplative smoke-rings at the ceiling, nodding his head from time to time in confirmation of the Commissioner's words.

"Yes," he agreed. "That's the trouble with the Boh. Every move a fellow makes is report "

A sharp crack from without the stockade, a thin tinkle of glass, and the front legs of Travers' chair came down with a bang, almost simultaneously.

The Commissioner and O'Neil hurled themselves away from the direct line in front of the window and stood looking at the jagged round hole in the glass with its long, radiating cracks. Only Travers sat where he was, his elbows resting on the arms of his chair, and his head bowed on his chest as if in deep thought, while his cigar burned a smoking hole in the tablecloth.

The Commissioner looked round and saw him.

"Jump, you fool!" he shouted. Then, "My God, he's hit!" he cried, as he saw a thin trickle of crimson steal down the white shirt-front. He rushed up to drag him out of the way; but Travers was a heavy man, and the Commissioner was short and fat.

"Give a hand, O'Neil," he panted, and swore aloud in his excitement as he received no response. O'Neil had dived out of the doorway.

The Commissioner cursed him for a white-livered craven and yelled for the servants. After a considerable delay a scared attendant helped him to remove Travers to the couch.

"Tell the memsahib to remain in the drawing-room," was the Commissioner's first order. The next was, "Run for the doctor sahib at once, ekdum."

The doctor's bungalow was some little distance off. The distracted Commissioner paced the floor for fifteen minutes before the doctor could arrive. A very brief examination was sufficient. The physician looked up and shook his head.

"The ball penetrated below his chin, and the whole top of his head is loose," he said with a shudder. "Death must have been instantaneous."

"I thought so from the way he fell," said the deep voice of O'Neil behind them, causing both men, in the jangled state of their nerves, to turn with a start. He had come in silently as a cat, and stood holding a rifle with a silver-inlaid stock and a highly ornamented cartridge-belt in his hands.

"Got him about two hundred yards out," he announced briefly, as he jerked an empty shell from his revolver and squinted down the barrel. "If you give me a couple of men, I'll fetch the body in."

"Who is that extraordinary man?" asked the doctor when he had gone.

But the Commissioner did not seem to hear him. He was again agitatedly pacing the floor muttering, "My God! My God! the third in two months. What will they say at headquarters?"

This was Boh Na-Ghee's message to the new Superintendent of Police.

O'NEIL spent the next few weeks in a whirl of activity, getting acquainted with his district and his thirty-five mounted troopers. These men had lived a life of easy inefficiency under their late chief, and had waxed fat on a system of petty extortions such as the Indian Police invariably establish throughout the villages which come under their grasp. O'Neil soon found that this was the chief reason why the Boh had so many friends ready to inform him of every move of his enemies.

"If we must be robbed," said the Burmans, "we had far rather be robbed by a countryman than by foreigners out of India."

He immediately embarked on a campaign against this zoolum or graft, assisted only by his orderly. This man was a sturdy, clean-cut mountaineer from the free kingdom of Nepal, and these scourings of Lower Bengal were his natural and hereditary enemies. Though the two had to contend against a hundred cunning wiles, the crafty troopers soon found that their "just perquisites" were one by one slipping from their grasp and were correspondingly indignant.

Not only were their incomes considerably reduced under the new regime, but they had to work harder into the bargain.

Though the Boh was the main problem, minor delinquencies were frequent, and O'Neil kept small squads of his men constantly in the saddle schooling his district, till the Burmans gave him the name of "Min Ta-Laing" which means "Man-who-never-sleeps."

This state of affairs produced many secret whisperings and murmurings of discontent among the thirty-five. At last they determined to send O'Neil a "death warning." One of their number was chosen to creep to his bungalow by night and there lay out on the veranda an intricate pattern of circles and triangles in colored rice. This is the Hindu version of a black-hand letter, and those skilled in its interpretation can read from the pattern exactly what the complaint is and what retribution is threatened.

But, stealthy as the designer was in his task, Man-who-never-sleeps in some way became aware of his presence. Leaping on him out of the darkness, O'Neil grabbed him by the neck in grim silence and forced him to eat every grain that he had laid down, to the irretrievable loss, not only of his honor among his fellows, but—what is infinitely worse to a Hindu — his caste. Then O'Neil kicked the malcontent down the veranda steps, still without saying a word or striking a light to see which of his men the offender was.

After that the troopers settled down with true Oriental fatalism to accept this curse that had been laid upon them.

All this while the Boh gave no sign; partly, as O'Neil rightly guessed, because he was taking stock of the new Superintendent, and partly because he was planning some peculiarly daring outrage.

Meanwhile O'Neil had his own troubles with his fellow officials. When he was asked to join the local club where they played bridge and billiards and drank large quantities of Scotch whisky, he politely refused, asserting as his reason that he could not afford to do so. His interlocutors went away fuming, with the firm conviction that he was stingy with his money. As a matter of fact, however, O'Neil had meant that he could not afford to let late hours and liquor interfere with his work.

His attitude was unprecedented. An official who refused to mix in with the effete social life of a district-station was not to be tolerated.

But O'Neil did worse even than this. When asked how much he would bet on Pretty Polly, the pride of Tuktoo, who was to be raced against Shwemyo next month, carrying all the available money in Tuktoo on her back, he committed the heresy of saying he would not bet because he was of the opinion that the Shwemyo horse would win. He knew that Shwemyo's jockey was an athletic Scotsman of the Post Office Department, and common sense told him that the other horse would be better trained and better ridden.

However, patriotic Tuktoo cried out against him. In fact, the Commissioner took occasion to draw him aside one day and speak to him about his attitude in general.

"See here, O'Neil," he began. "You ought to know better than to go on like this. You've been in the country long enough to know that in a small station like this you're expected to join in with the other fellows in everything."

"I understand you, sir," O'Neil had replied; "and I wish I could do as you say, for I am not a hermit by nature; but I know, and you know, that I can't play bridge all night and be up chasing crooks at two in the morning. I'm here on probation, and my promotion depends on my ability to keep things quiet in this district. I need that promotion," he went on quietly, with the first trace of expression the Commissioner had ever seen in his face, "and I'll tell you why. There's a girl at home in Limerick who's waited five years for it to come—five years, Mr. Raynor! And—I'm going to—get—it."

The Commissioner looked at O'Neil, standing there, keen and determined. In contrast to O'Neil's hard, trained efficiency there rose before his eyes the picture of the flabby incompetence which had marked his own life and was so apparent in the lives of his fellow officials of the club. A deep hatred for this young man who showed them all up in such unfavorable contrast took possession of his soul.

O'Neil was quick to see that his chief was not pleased, but in his innocence he consoled himself with the reflection that as long as he did his duty satisfactorily no harm could come to him. He little knew how great a part the Commissioner's report would play in his subsequent promotion.

Things were in this state when the Boh played his next stroke, in which daring insult was mingled with injury.

It was six in the evening, and all the men had come in to the club from their various offices, when a stable-boy was assisted in. They all rose to their feet with a feeling of excitement; they knew that something must be very much amiss for a wounded native to be brought into the sacred precincts of the club-house.

The feeling was justified. The man's faltering story was short and incisive. He had taken Pretty Polly out for exercise an hour ago, and had ridden but half a mile, when suddenly five men had sprung out on him with swords and clubs. That was all he knew.

The news fell like a thunderbolt. The doctor instinctively took the patient off to his little hospital, while the rest of the men stood about in a daze. Their first thought had been the race. Most of them had laid heavy odds on Pretty Polly, and they had no other horse which could stand any chance against Shwemyo. They began to calculate helplessly their certain losses. Many of them with the nervous impulse of long habit ordered drinks.

Suddenly "Let's go to O'Neil," somebody shouted. "If he's such a deuce of a good policeman, there's just a chance that he might catch him."

They sprang to their feet and raced to O'Neil's bungalow in a body, bursting unceremoniously into the dining-room, where they found a meal laid out from which the dish-covers had not yet been removed.

"O'Neil," they yelled in chorus. "Hello there, O'Neil! Where are you?"

There was no reply. Their hearts sank. What if he were absent somewhere on his duties and could not be found?

An indignant servant arrived from the rear of the house to inquire into the cause of the uproar. "The sahib? Oh, the sahib had suddenly run off fifteen minutes ago to pursue a man who had stolen somebody's horse."

THE news had been brought to O'Neil by his orderly. The quick-witted little Gurkha had met the party bringing in the wounded rider on the road, and while they, slowly and with much noise, had been conveying the boy to the club-house, he had run straight to his master with blazing eyes and a fierce exultation at the prospect of approaching conflict. "Shall I send a messenger to recall the men who have gone to Kyaukse for the new remounts?" he asked as he concluded his tale.

"No time for that, Jung Bir," replied O'Neil, hurriedly strapping his leggings. "Besides there is no need; I gave orders that five men should stay in barracks."

The Gurkha grunted scornfully. "Sahib, with these low country swine it is one thing to give orders and another to see how they are carried out. Five men have indeed stayed behind, but, of the five, four are sick and one is old Sher Ali, the barrack-master, who is too fat to take saddle for an expedition such as this."

O'Neil sat down thoughtfully and swore softly to himself, while his mind rapidly reviewed the situation. What confounded ill luck! Here was a chance indeed—the Boh, with only four men! When would be ever get such an opportunity again? The man's capture meant a big reward, and then— promotion.

His mind was made up. He would stake everything on the venture. He laughed aloud and buckled on his revolver-belt with a snap.

"It matters not," he said. "I go alone— unless of thy own free will thou wilt accompany me, Jung Bir; for in this matter of two against five I can not order thee."

The little hillman grinned cheerfully.

"Nay, sahib, how could I let my father and my mother go alone? As for the odds, what matter? We twain have played together with death many times."

"Good man, Jung Bir!" was all O'Neil's comment. Ten minutes later he was trotting through the silent jungle followed by the Gurkha, who cheerfully whistled through his teeth queer little tunes in minor keys that ended nowhere.

As they rode, O'Neil was thinking hard, searching for a plan of campaign. And here the knowledge of the country which his unfailing activity of the last few weeks had given him stood him in good stead. Piece by piece he mapped out the ground, and bit by bit he perfected his plan. Finally he turned to the Gurkha:

"Jung Bir," he began, "the men have had an hour's start. Therefore it seems to me that it is hopeless to catch up with them."

"So much I know, sahib. I was but waiting to hear what the sahib's wisdom had shown him."

"H'm!" grunted O'Neil. "You seem to be darned satisfied about it."

"Why not, sahib? Do I not know that the sahib always has a plan?"

O'Neil's only comment was another grunt.

"Well," he went on, "it is in my mind that to return to his own place from here, the Boh will surely first travel to the Yedaw Ford, and thence by the Paukte Road to the mountains. If, therefore, we swim the Yedaw here, thou and I, leaving our horses on this side, we may lie in wait by the Paukte Road, and when he comes we may follow till he camps for the night. While they sleep, an opportunity will occur."

"Ow!" admired the Gurkha. "That is a cunning plan; moreover there will surely be fighting."

Forthwith the bloodthirsty little fellow took out a little stone and his great kookerie and began whetting its already razor-edge with cheerful relish. This kookerie was a sort of heavy knife which his people are never seen without. Of boomerang shape, with a broad blade and exquisite balance, in experienced hands it forms a terrible weapon for close quarters.

Suddenly he held up his head and listened.

"Sahib," he whispered, "there is one who trails us."

"I know it," answered O'Neil quietly. "The Boh is a clever man and he has always a tracker waiting to take up the trail as soon as I go out anywhere. I do but wait for a favorable place, and then I will dismount and take him, for the Boh must have no knowledge of our plan."

"Nay, sahib," remonstrated the Gurkha. "This is no matter for a gun and noise; let me show how my people would do this thing."

Scarce waiting for O'Neil's approval, he slipped silently to the ground.

"Do thou lead my horse, Sahib," he whispered, "that he may suspect nothing. For the rest—"

He lovingly drew his kookerie again and melted into the jungle.

Ten minutes later he trotted up behind and climbed onto his horse with an expression of deep content,

"He had two rupees and some small change," he announced.

Shortly afterward they came to the banks of the Yedaw, which was a broad and swift-flowing stream.

"Wow! It will be cold," shivered the Gurkha. "Can the sahib do it? As for me, I am accustomed to these mountain streams."

"There is no other way; I must do it," answered O'Neil. "As for the cold, warmth will follow on the way to the Paukte Road; the traveling will be bad and there will be need for much haste."

They tied their horses carefully and waded in. Soon, in spite of their exertions to stem the current, their teeth were chattering with the chill of the melted snow from the mountains. Once O'Neil felt a gripping sensation in his leg suggestive of cramp, and for a moment a wave of unreasoning terror swept over his soul, bringing an almost irresistible temptation to turn back while he yet knew that he could reach the bank. But he set his teeth and went doggedly forward; "this was the only chance of coming up with the Boh. The feeling passed. A little later he scrambled ashore on the other side, where he found the Gurkha waiting for him.

Without exchanging a word they set off on a long jog-trot which was to bring them to the nearest point in the Paukte Road where they hoped to intercept the Boh and his party. As O'Neil had predicted, they were thoroughly dry and considerably warmer than was pleasant by the time they arrived.

THEY hid themselves and settled down to the weary task of waiting —waiting for the moon to rise and for the Boh to arrive. Noxious insects crawled over them and sickening doubts assailed them as to whether their quarry had not gone by already, for until the moon shed some light on the path they could see no telltale tracks.

The Gurkha was accustomed to the habitations of his own people, so ants and stinging things troubled him not. But O'Neil's less callous skin was tortured by all the varieties of malignant tropical vermin. Yet he lay still, without a turn or a twist to relieve himself, knowing that the least sound might betray them to a clever forerunner in case the Boh took the precaution to send one ahead.

At length the wait came to an end. A far-away hoof-beat rewarded their patience. The Gurkha listened with his ear to the ground.

"Sahib, there be two horses only," he breathed anxiously.

O'Neil shook his head.

"Not two. One. The other is a man running, with boots on, and I have heard that the Boh always wears English boots."

The Gurkha listened again, but it was not until the sound was much nearer that he could distinguish the difference. They stiffened themselves and lay like logs as the party came by; five men and Pretty Polly, all going at the same jog-trot, which the Burmans can keep up for hours.

The watchers stole silently out of their hiding-place and followed like shadows, bringing all their knowledge of woodcraft to play to avoid the least noise. But in spite of their care the Gurkha stepped on a dry branch lying in a dark shadow. In the night stillness the wood snapped like a pistol-shot.

Immediately the party ahead stopped suspiciously and the Boh sent a man back to investigate. O'Neil caught his orderly by the arm.

"Follow," he whispered. Uttering a series of grunts and squeaks in excellent imitation of a startled wild pig, he crashed off into the thicket.

The Burman laughed. "Thamin shi de" he called to the others, and hurried after them as they broke into their trot again; and the trailers stole out and followed like hunting wolves.

At length the chief held up his hand. They halted and struck off at right angles to the path, picking their way among the trees till the leader thought they were far enough from the road to light a fire without fear of detection by possible passers-by.

"Kaung de, it is well," he announced in a harsh voice. "Here do we camp. Do thou, Hla-Oo, hobble the horse and take the first watch in this open place while we retire under the trees over there to prepare food."

O'Neil and his orderly watched them busy themselves about the camp. It was then that they remembered that neither of them had eaten since the morning. The Gurkha edged closer. "When we have slain them, sahib," he chuckled, "we will eat their meal."

O'Neil frowned at him. "There is to be no unnecessary slaying here," he warned.

The Gurkha grinned back at him. "In the stress of battle who will say what is necessary and what is not? But behold, sahib, a plan comes to me. The others are afar off and the watcher sits in tall grass as high as his chin. It is in my mind that we may stalk him and fall upon him silently. Thus will there be only four left. And having taken him, I will bind his cloth about my head and sit in his place, and it shall happen that when his relief comes we may take him singly also, leaving only three to contend against."

"Good!" muttered O'Neil. "Good man!" The cunning little hillman was indeed an adept at jungle warfare and had been quick to see his advantage.

Together they began to creep forward, foot by foot, inch by inch, on their stomachs, feeling before them for dry twigs and leaves which might betray their approach. Closer they came and closer.

It seemed as if they would really accomplish their purpose without mishap, when some curious sixth sense apparently warned their victim. He rose to his feet with an uneasy shudder—a white man would have said that he felt like somebody walking over his grave. He looked around, and his eye immediately fell on the two dark indentations in the long grass within a few yards of him which he did not remember having noticed before. He stepped forward cautiously to investigate, wading waist-deep through the tall stems. There was evidently something in the shadow in front of him; he peered forward.

There was nothing for it; discovery was now certain. A crooked gleam shot over the grass tops and the man sunk down with a loud "A-ah!" clutching at his stomach with rigid fingers through which the bowels gushed.

THE group at the fire sprang to their feet, snatching for their weapons. An evil-visaged ruffian came running to his fallen companion and crashed over him all in a heap, hocked, with the tendons of both legs gashed through behind the knee. This was the cunning warfare of the Gurkhas.

The little man had tasted blood, and the lust came upon him. Giving the whistling war-cry of his people he rushed to meet the others in a blind rage of Berserk fury.

O'Neil saw the Boh leap at him, swinging a great two-handed dah, with another man just behind him. He tore out his sword, but realized as it left the scabbard that that light weapon would be useless to parry the sweep of the heavy dah. With the speed of light he dropped it, ducked under the blow and butted his shoulder into the Boh's chest like a football-player, sending his antagonist staggering into his follower. The three went rolling over together.

O'Neil's one endeavor was to keep on top of both men, but the Boh managed to roll away and spring to his feet like a cat. He swung up the long sword for another blow just as O'Neil snatched at his ankle and brought him down again sprawling. O'Neil instantly grabbed at the long handle of the weapon and fought for its possession. He was a powerful man and ordinarily would have experienced no difficulty in getting it, but he was very much occupied in keeping the other man from reaching his own weapon, which had been knocked from his grasp as he fell. In addition the Boh had the upper grip on the dah-handle and it was all he could do to prevent him from bringing the blade down on his. head.

There are two kinds of fighters; those who try to carry everything before them in a blind fury and are yet quick to take advantage of every little opportunity as it occurs, and those who go to it more quietly, acting on the defensive while they think out means to make their own opportunities, which are so much the more effective when they are brought into use. O'Neil was of the latter sort. While he defended himself from the Boh's sword he was thinking furiously how to rid himself of the other man.

It was then that he was thankful for the course of jiu-jitsu training which he had gone through in the police school, which had taught him the use of his legs in a fight. He allowed the surprised man to raise his body from the ground a little and then immediately caught his neck in the crook of his knee. Then he settled down to apply a process of strangulation, leaving both his arms free to attend to the Boh.

This small respite gave him an opportunity to look up and see Jung Bir in an evil case. Jung's opponent, a perfect giant, had in some way escaped the terrible kookerie and was now forcing his lighter antagonist back, waiting his opportunity to use a knife which he held between his teeth. O'Neil took in the situation in one hurried glance and instantly decided on a desperate move which depended on speed for its success.

He suddenly let go with his right hand and struck the Boh in the face with intent to daze him as much as possible. Then he snatched for his revolver. He got in one hurried shot at the giant and the next instant his fingers received a cruel gash as the weapon was knocked from his grasp.

For the next strenuous half-minute his attention was fully taken up with the Boh, and, hampered as he was in the use of his legs, he found himself weakening. It was with a feeling of heavenly relief that he finally heard his orderly's voice behind him saying: "Give him to me, sahib," and felt the other man dragged away from beneath him. It was now only a matter of seconds. Alone, the Boh was no match for him. Getting a good purchase with his knees, he slowly heaved the Boh over on to his face, when he secured him with an arm-and-leg hold.

"That was well done, sahib," said a cheerful voice, and he looked up to see Jung Bir, with his tunic half torn off his back, wiping his kookerie with a bunch of grass and smiling seraphically, "It was also a great shot of the sahib's, for which I will make offerings to the gods in his honor. Let me now assist in binding this dog. There! It now remains but to wash the sahib's wound and to eat the food of these robbers."

IT was daybreak when they arrived in Tuktoo with the prisoner and the recovered horse. O'Neil turned the former into the guard-room and quietly despatched the latter to the stable without waking any of the interested officials out of their downy beds. Then he called a bugler to him.

"Boot and saddle, for inspection of new remounts," he ordered.

Later in the day, when the station woke to the joyful news that Pretty Polly was even then getting a rubdown in the stable-yard, the whole community once again went to O'Neil's bungalow in a body, this time to make him an ovation. But a grave servant informed them that "the sahib had retired to his room, having previously expressed apprehension lest sundry other sahibs should come to see him with shoutings and outcry, and that his orders were in this event to say that he craved their indulgence and begged to be permitted to rest after his labors."

THAT evening a hot discussion, the subject of which was O'Neil, took place in the club. The majority argued that his recovery of Pretty Polly had raised him to the status of a public benefactor, and that the Commissioner could not now refuse to send in a glowing report. But a few of the older ones who knew the Commissioner better maintained that that official would not be carried away by temporary enthusiasm, and would come to the certain reflection that O'Neil, though perhaps the best policeman in Burma, was, and would ever remain, valueless to the social life of a district station, and that he would therefore inevitably condemn him. To this opinion the assistant agreed, adding, "It may be hard luck, and all that, but it's no use; the chief hates him on his own account."

On this discussion entered the Commissioner himself with a "service telegram" from the lieutenant-governor in reply to his earlier wire reporting the Boh's capture.

"I heard you were having an argument," he said condescendingly. "Well, this settles it."

The telegram read:

YOUR WIRE RE BOH NA-GHEE. O'NEIL TRANSFERRED MY PERSONAL STAFF. INFORM HIM JOIN DUTIES AT ONCE. L.-G.

At the same moment O'Neil was sending a cable to Limerick. The cable read:

COME!

That was all.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.