RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"A Prince of Swindlers," Ward, Locke & Co., London, 1900.

Headpiece from Pearson's Magazine.

IT was the day following that upon which Simon Carne, presented by the Earl of Amberley, had made his bow before the Heir Apparent at the second levée of the season, that Klimo entered upon one of the most interesting cases which had so far come into his experience. The clock in his consulting room had just struck one when his elderly housekeeper entered, and handed him a card, bearing the name of Mrs. George Jeffreys, 14, Bellamer Street, Bloomsbury. The detective immediately bade his servant admit the visitor, and, almost before he had given the order, the lady in question stood before him.

She was young, not more than twenty-four at most, a frail wisp of a girl, with light brown hair and eyes that spoke for her nationality as plain as any words. She was neatly, but by no means expensively dressed, and showed evident signs of being oppressed by a weight of trouble. Klimo looked at her, and in that glance took in everything. In spite of the fact, that he was reputed to possess a heart as hard as any flint, it was noticeable that his voice, when he spoke to her, was not as gruff as that in which he usually addressed his visitors.

"Pray sit down," he said, "and tell me in as few words as possible what it is you desire that I should do for you. Speak as clearly as you can, and, if you want my help, don't hesitate to tell me everything."

The girl sat down as ordered, and immediately commenced her tale.

"My name is Eileen Jeffreys," she said. "I am the wife of an English Bank Inspector, and the daughter of Septimus O'Grady, of Chicago, U.S.A."

"I shall remember," replied Klimo. "And how long have you been married?"

"Two years," answered the girl. "Two years next September. My husband and I met in America, and then came to England to settle."

"In saying good-bye to your old home, you left your father behind, I presume?"

"Yes, he preferred to remain in America."

"May I ask his profession?"

"That, I'm afraid, foolish as it may seem to say so, I cannot tell you," answered the girl, with a slightly heightened colour. "His means of earning a living were always kept a secret from me."

"That was rather strange, was it not?" said Klimo. "Had he private resources?"

"None that I ever heard of," replied the girl.

"Did no business men ever come to see him?"

"But very few people came to us at all. We had scarcely any friends."

"Of what nationality were the friends who did come?"

"Mostly Irish, like ourselves," answered Mrs. Jeffreys.

"Was there ever any quarrel between your father and your husband, prior to your leaving America?"

"Never any downright quarrel," said the girl. "But I am sorry to say they were not always the best of friends. In those days my father was a very difficult man to get on with."

"Indeed?" said Klimo. "Now, perhaps you had better proceed with your story."

"To do that, I must explain that at the end of January of this present year, my father, who was then in Chicago, sent us a cablegram to say he was leaving for England that very day, and, that upon his arrival in England, if we had no objection, he would like to take up his residence with us. He was to sail from New York on the Saturday following, and, as you know, the passage takes six days or thereabouts. Arriving in England he came to London and put up at our house in Bellamer Street, Bloomsbury. That was during the first week in February last, and off and on he has been living with us ever since."

"Have you any idea what brought him to England?"

"Not the least," she answered deliberately, after a few seconds' pause, which Klimo did not fail to notice.

"Did he do business with any one that you are aware of?"

"I cannot say. On several occasions he went away for a week at a time into the Midlands, but what took him there I have no possible idea. On the last occasion he left us on the fifteenth of last month, and returned on the ninth of this, the same day that my husband was called away to Marseilles on important banking business. It was easy to see that he was not well. He was feverish, and within a short time of my getting him to bed began to wander in his mind, declaring over and over again that he bitterly repented some action he had taken, and that if he could once consider himself safe again would be quit of the whole thing for ever.

"For close upon a fortnight I continued to nurse him, until he was so far recovered as to recognise me once more. The day that he did so I took in at the door this cablegram, from which I may perhaps date the business that has brought me to you."

She took a paper from her pocket and handed it to Klimo, who glanced at it, examined the post-mark and the date, and then placed it upon the desk before him. It was from Chicago, and ran as follows:—

O'GRADY,

13, BELLAMER STREET, LONDON, ENGLAND.

WHY NO ANSWER? REPLY CHANCES OF DOING BUSINESS.

NERO.

"Of course, it was impossible for me to tell what this meant. I was not in my father's confidence, and I had no notion who his mysterious correspondent might be. But as the doctor had distinctly stated that to allow him to consider any business at all would bring on a relapse and probably kill him, I placed the message in a drawer, and determined to let it remain there until he should be well enough to attend to it without danger to himself. The week following he was not quite so well, and fortunately there was complete silence on the part of his correspondents. Then this second message arrived. As you will see it is also from Chicago and from the same person.

REPLY IMMEDIATELY, OR REMEMBER CONSEQUENCES. TIME PRESSES, IF DO NOT REALISE AT PRESENT PRICE, MARKET WILL BE LOST. NERO.

"Following my previous line of action, I placed this communication also in the drawer, and determined to let Nero wait for a reply. By doing so, however, I was incurring greater trouble than I dreamt of. Within forty-eight hours I received the following message, and upon that I made up my mind and came off at once to you. What it means I do not know, but that it bodes some ill to my father I feel certain. I had heard of your fame, and as my husband is away from home, my father unable to protect himself, and I am without friends at all in England, I thought the wisest course I could pursue would be to consult you."

"Let me look at the last cablegram," said Klimo, putting his hand from the box, and taking the slip of paper.

The first and second messages were simplicity itself; this, however, was a complete enigma. It was worded as follows:—

UNEASY — ALPHA — OMEGA — NINETEEN — TWELVE — TO-DAY — FIVE — LACS — ARRANGE — SEVENTY — EIGHT — BRAZILS — ONE — TWENTY — NINE. NERO.

Klimo read it through, and the girl noticed that he shook his

head over it.

"My dear young lady," he said, "I am afraid that it would be safer for you not to tell me any further, for I fear it is not in my power to help you."

"You will not help me now that I have told you my miserable position? Then there is nothing before me but despair. Oh, sir, is your decision quite irrevocable? You cannot think how I have counted on your assistance."

"I regret exceedingly that I am compelled to disappoint you," he answered. "But my time is more than occupied as it is, and I could not give your case my attention, even if I would."

His decision had been too much for her fortitude, and before he could prevent it, her head was down upon her hands and she had begun to weep bitterly. He attempted to comfort her, but in vain; and when she left him, tears were still coursing down her cheeks. It was not until she had been gone about ten minutes, and he had informed his housekeeper that he would see no more clients that day, that he discovered that she had left her precious cablegrams behind her.

Actuated by a feeling of curiosity, he sat down again and spread the three cablegrams out upon his writing-table. The first two, as I have said, required no consideration, they spoke for themselves, but the third baffled him completely. Who was this Septimus O'Grady who lived in Chicago, and whose associates spent their time discussing the wrongs of Ireland? How was it that, being a man innocent of private means, he engaged in no business?

Then another question called for consideration. If he had no business, what brought him to London and took him so repeatedly into the Midlands? These riddles he set aside for the present, and began to pick the last cablegram to pieces. That its author was not easy in his mind when he wrote it was quite certain.

Then who and what were the Alpha and Omega mentioned? What connection had they with Nero; also what did nineteen and twelve mean when coupled with To-day? Further, why should five lacs arrange seventy-eight Brazils? And what possible sense could be made out of the numbers one — twenty — and nine? He read the message from beginning to end again, after that from the end to the beginning, and, like a good many other men in a similar position, because he could not understand it, found himself taking a greater interest in it. This feeling had not left him when he had put off disguise as Klimo and was Simon Carne once more.

While he was eating his lunch the thought of the lonely Irishman lying ill in a house, where he was without doubt an unwelcome guest, fascinated him strangely, and when he rose from the table he found he was not able to shake off the impression it had given him. That the girl had some notion of her father's business he felt as certain as of his own name, even though she had so strenuously denied the fact. Otherwise why should she have been so frightened by what might have been simply innocent business messages in cypher? That she was frightened was as plain as the sun then shining into his room. Despite the fact that he had resolved not to take up the case, he went into his study, and took the cablegrams from the drawer in which he had placed them. Then drawing a sheet of paper towards him, he set to work upon the puzzle.

"The first word requires no explanation," he said as he wrote it down. "For the two next, Alpha and Omega, we will, for the sake of argument, write The Beginning and The End, and as that tells us nothing, we will substitute for them The First and The Last. Now, who or what are The First and The Last? Are they the first and last words of a code, or of a word, or do they refer to two individuals who are the principal folk in some company or conspiracy? If the latter, it is just possible they are the people who are so desperately uneasy. The next two words, however, are too much for me altogether."

Uninteresting as the case had appeared at first sight, he soon discovered that he could think of nothing else. He found himself puzzling over it during an afternoon concert at the Queen's Hall, and he even thought of it while calling upon the wife of the Prime Minister afterwards. As he drove in the Park before dinner, the wheels of his carriage seemed to be saying "Alpha and Omega, nineteen, twelve" over and over again with pitiless reiteration, and by the time he reached home once more he would gladly have paid a ten-pound note for a feasible solution of the enigma, if only to get its weight off his mind.

While waiting for dinner he took pen and paper and wrote the message out again, this time in half a dozen different ways. But the effect was the same, none of them afforded him any clue. He then took the second letter of each word, after that the third, then the fourth, and so on until he had exhausted them. The result in each case was absolute gibberish, and he felt that he was no nearer understanding it than when Mrs. Jeffreys had handed it to him nearly eight hours before.

During the night he dreamt about it, and when he woke in the morning its weight was still upon his mind. "Nineteen — twelve," it is true had left him, but he was no better off for the reason that "Seventy-eight Brazils" had taken its place. When he got out of bed he tried it again. But at the end of half an hour his patience was exhausted.

"Confound the thing," he said, as he threw the paper from him, and seated himself in a chair before his looking-glass in order that his confidential valet, Belton, might shave him. "I'll think no more of it. Mrs. Jeffreys must solve the mystery for herself. It has worried me too much already."

He laid his head back upon the rest and allowed his valet to run the soap brush over his chin. But, however much he might desire it his Old Man of the Sea was not to be discarded so easily; the word "Brazils" seemed to be printed in letters of fire upon the ceiling. As the razor glided over his cheek he thought of the various constructions to be placed upon the word— The Country — Stocks — and even nuts — Brazil nuts, Spanish nuts, Barcelona nuts, walnuts, cob nuts — and then, as if to make the nightmare more complete, no less a thing than Nuttall's Dictionary. The smile the last suggestion caused him came within an ace of leaving its mark upon his cheek. He signed to the man to stay his hand.

"Egad!" he cried, "who knows but this may be the solution of the mystery? Go down to the study, Belton, and bring me Nuttall's Dictionary."

He waited with one side of his face still soaped until his valet returned, bringing with him the desired volume. Having received it he placed it upon the table and took up the telegram.

He placed it upon the table and took up the telegram.

"SEVENTY — EIGHT BRAZILS," it said, "ONE — TWENTY

— NINE."

Accordingly he chose the seventieth page, and ran his fingers down the first column. The letter was B, but the eighth word proved useless. He thereupon turned to the seventy-eighth page, and in the first column discovered the word Bomb. In a second the whole aspect of the case changed, and he became all eagerness and excitement. The last words on the telegram were "one-twenty- nine," yet it was plain that there were barely a hundred upon the page. The only explanation, therefore, was that the word "One "distinguished the column, and the "twenty-nine "referred to the number of the word in it.

Almost trembling with eagerness he began to count. Surely enough the twenty-ninth word was Bomb. The coincidence was, to say the least of it, extraordinary. But presuming that it was correct, the rest of the message was simplicity itself. He turned the telegram over, and upon the back transcribed the communication as he imagined it should be read. When he had finished, it ran as follows:

Owing to O'Grady's silence, the Society in Chicago is growing uneasy. Two men, who are the first and last, or, in other words, the principal members, are going to do something (Nineteen- twelve) to-day with fifty thousand somethings, so arrange about the bombs.

Having got so far, all that remained to be done was to find out to what "nineteen-twelve "referred. He turned to the dictionary again, and looked for the twelfth word upon the nineteenth page. This proved to be "Alkahest," which told him nothing. So he reversed the proceedings and looked for the nineteenth word upon the twelfth page; but this proved even less satisfactory than before. However much the dictionary might have helped him hitherto, it was plainly useless now. He thought and thought, but without success. He turned up the almanac, but the dates did not fit in.

He then wrote the letters of the alphabet upon a sheet of paper, and against each placed its equivalent number. The nineteenth letter was S, the twelfth L. Did they represent two words, or were they the first and the last letters of a word? In that case, what could it be. The only three he could think of were soil, sell, and sail. The two first were hopeless, but the last seemed better. But how would that fit in? He took up his pen and tried it.

Owing to O'Grady's silence, the Society in Chicago is growing uneasy. Two men, who are the first and last, or, in other words, the principal members, sail to-day with fifty thousand somethings, probably pounds or dollars, so prepare bombs.

Nero.

He felt convinced that he had hit it at last. Either it was a

very extraordinary coincidence, or he had discovered the answer

to the riddle. If his solution were correct, one thing was

certain, he had got in his hands, quite by chance, a clue to one

of the biggest Fenian conspiracies ever yet brought to light. He

remembered that at that moment London contained half the crowned

heads, or their representatives, of Europe. What better occasion

could the enemies of law and order desire for striking a blow at

the Government and society in general? What was he to do?

To communicate with the police and thus allow himself to be drawn into the affair, would be an act of the maddest folly; should he therefore drop the whole thing, as he had at first proposed, or should he take the matter into his own hands, help Mrs. Jeffreys in her trouble by shipping her father out of harm's way, outwit the Fenians, and appropriate the fifty thousand pounds mentioned in the cablegram himself?

The last idea was distinctly a good one. But, before it could be done, he felt he must be certain of his facts. Was the fifty thousand referred to money, or was it something else? If the former, was it pounds or was it dollars? There was a vast difference, but in either case, if only he could hit on a safe scheme, he would be well repaid for whatever risk he might run. He decided to see Mrs. Jeffreys without loss of time. Accordingly, after breakfast, he sent her a note asking her to call upon him, without fail, at twelve o'clock.

Punctuality is not generally considered a virtue possessed by the sex of which Mrs. Jeffreys was so unfortunate a member, but the clock upon Klimo's mantelpiece had scarcely struck the hour before she put in an appearance. He immediately bade her be seated.

"Mrs. Jeffreys," he began with a severely judicial air, "it is with much regret I find that while seeking my advice yesterday you were all the time deceiving me. How was it that you failed to tell me that your father was connected with a Fenian Society, whose one aim and object is to destroy law and order in this country?"

The question evidently took the girl by surprise. She became deathly pale, and for a moment Klimo thought she was going to faint. With a marvellous exhibition of will, however, she pulled herself together and faced her accuser.

"You have no right to say such a thing," she began. "My father is—"

"Pardon me," he answered quietly, "but I am in the possession of information which enables me to understand exactly what he is. If you answer me correctly it is probable that after all I will take your case up, and will help you to save your father's life, but if you decline to do so, ill as he is, he will be arrested within twenty-four hours, and then nothing on earth can save him from condign punishment. Which do you prefer?"

"I will tell you everything," she said quickly. "I ought to have done so at first, but you can understand why I shrank from it. My father has for a long time past been ashamed of the part he has been playing, but he could not help himself. He was too valuable to them, and they would not let him slip. They drove him on and on, and it was his remorse and anxiety that broke him down at last."

"I think you have chosen the better course in telling me this. I will ask my questions, and you can answer them. To begin with, where are the headquarters of the Society?"

"In Chicago."

"I thought as much. And is it possible for you to tell me the names of the two principal members?"

"There are many members, and I don't know that one is greater than another."

"But there must be some who are more important than others. For instance, the pair referred to in this telegram as Alpha and Omega?"

"I can only think," she answered, after a moment's thought, "that they must be the two men who came oftenest to our house, Messrs. Maguire and Rooney."

"Can you describe them, or, better still, have you their photographs?"

"I have a photograph of Mr. Rooney. It was taken last year."

"You must send it to me as soon as you get home," he said; "and now give me as close a description as possible of the other person to whom you refer, Mr. Maguire."

Mrs. Jeffreys considered for a few moments before she answered.

"He is tall, standing fully six feet, I should think," she said at last, "with red hair and watery blue eyes, in the left of which there is a slight cast. He is broad shouldered and, in spite of his long residence in America, speaks with a decided brogue. I know them for desperate men, and if they come over to England may God help us all. Mr. Klimo, you don't think the police will take my father?"

"Not if you implicitly obey my instructions," he answered.

Klimo thought for a few seconds, and then continued: "If you wish me to undertake this business, which I need hardly tell you is out of my usual line, you will now go home and send me the photograph you spoke of a few moments since. After that you will take no sort of action until you hear from me again. For certain reasons of my own I shall take this matter up, and will do my utmost to save your father. One word of advice first, say nothing to anybody, but pack your father's boxes and be prepared to get him out of England, if necessary, at a moment's notice."

The girl rose and made as if she would leave the room, but instead of doing so she stood irresolute. For a few moments she said nothing, but fumbled with the handle of her parasol and breathed heavily. Then the pluck which had so far sustained her gave way entirely, and she fell back on her chair crying as if her heart would break. Klimo instantly left his box and went round to her. He made a figure queer enough to please any one, in his old-fashioned clothes, his skull cap, his long grey hair reaching almost to his shoulders, and with his smoked glass spectacles perched upon his nose.

"Why cry, my dear young lady?" said Klimo. "Have I not promised to do my best for you? Let us, however, understand each other thoroughly. If there is anything you are keeping back you must tell me. By not speaking out you are imperilling your own and your father's safety."

"Why cry, my dear young lady?" said Klimo.

"I know that you must think that I am endeavouring to deceive you," she said; "but I am so terribly afraid of committing myself that I hardly know what to tell and what not to tell. I have come to you, having no friends in the whole world save my husband, who is in Marseilles, and my father, who, as I have said, is lying dangerously ill in our house.

"Of course I know what my father has been. Surely you cannot suppose that a grown up girl like myself could be so dense as not to guess why few save Irishmen visited our house, and why at times there were men staying with us for weeks at a time, who lived in the back rooms and never went outside our front door, and who, when they did take their departure, sneaked out in the dead of night.

"I remember a time in the fall of the last year that I was at home, when there were more meetings than ever, and when these men, Maguire and Rooney, almost lived with us. They and my father were occupied day and night in a room at the top of the house, and then, in the January following, Maguire came to England. Three weeks later the papers were full of a terrible dynamite explosion in London, in which forty innocent people lost their lives. Mr. Klimo, you must imagine for yourself the terror and shame that seized me, particularly when I remembered that my father was a companion of the men who had been concerned in it.

"Now my father repents, and they are edging him on to some fresh outrage. I cannot tell you what it is, but I know this, that if Maguire and Rooney are coming to England, something awful is about to happen, and if they distrust him, and there is any chance of any one getting into trouble, my father will be made the scapegoat.

"To run away from them would be to court certain death. They have agents in almost every European city, and, unless we could get right away to the other side of the world, they would be certain to catch us. Besides, my father is too ill to travel. The doctors say he must not be disturbed under any pretence whatever."

"Well, well!" said Klimo, "leave the matter to me, and I will see what can be done. Send me the photograph you spoke of, and let me know instantly if there are any further developments."

"Do you mean that after all I can rely upon you helping me?"

"If you are brave," he answered, "not without. Now, one last question, and then you must be off. I see in the last telegram, mention made of fifty lacs; I presume that means money?"

"A lac is their term for a thousand pounds," she answered without hesitation.

"That will do," said Klimo. "Now go home and don't worry yourself more than you can help. Above all, don't let any one suspect that I have any interest in the case. Upon your doing that will in a great measure depend your safety."

She promised to obey him in this particular as in the others, and then took her departure.

When Klimo had passed into the adjoining house, he bade his valet accompany him to his study.

"Belton," he said, as he seated himself in a comfortable chair before his writing table, "I have this morning agreed to undertake what promises to be one of the most dangerous, and at the same time most interesting, cases that has yet come under my notice. A young lady, the wife of a respectable Bank Inspector, has been twice to see me lately with a very sad story. Her father, it would appear, is an Irish American, with the usual prejudice against this country. He has been for some time a member of a Fenian Society, possibly one of their most active workers. In January last the executive sent him to this country to arrange for an exhibition of their powers.

"Since arriving here the father has been seized with remorse, and the mental strain and fear thus entailed have made him seriously ill. For weeks he has been lying at death's door in his daughter's house. Hearing nothing from him the Society has telegraphed again and again, but without result. In consequence, two of the chief and most dangerous members are coming over here with fifty thousand pounds at their disposal, to look after their erring brother, to take over the management of affairs, and to commence the slaughter as per arrangement.

"Now as a peaceable citizen of the City of London, and a humble servant of Her Majesty the Queen, it is manifestly my duty to deliver these rascals into the hands of the police. But to do that would be to implicate the girl's father, and to kill her husband's faith in her family; for it must be remembered he knows nothing of the father's Fenian tendencies. It would also mix me up in a most undesirable matter at a time when I have the best of reasons for desiring to keep quiet.

"Well, the long and the short of the matter is that I have been thinking the question out, and I have arrived at the following conclusion. If I can hit upon a workable scheme I shall play policeman and public benefactor, checkmate the dynamiters, save the girl and her father, and reimburse myself to the extent of fifty thousand pounds. Fifty thousand pounds, Belton, think of that. If it hadn't been for the money I should have had nothing at all to do with it."

"But how will you do it, sir?" asked Belton, who had learnt by experience never to be surprised at anything his master might say or do.

"Well, so far," he answered, "it seems a comparatively easy matter. I see that the last telegram was dispatched on Saturday, May 26th, and says, or purports to say, 'sail to-day' In that case, all being well, they should be in Liverpool some time to- morrow, Thursday. So we have a clear day at our disposal in which to prepare a reception for them. Tonight I am to have a photograph of one of the men in my possession, and to-morrow I shall send you to Liverpool to meet them. Once you have set eyes on them you must not lose sight of them until you have discovered where they are domiciled in London. After that I will take the matter in hand myself."

"At what hour do you wish me to start for Liverpool, sir?" asked Belton.

"First thing to-morrow morning," his master replied. "In the meantime you must, by hook or crook, obtain a police inspector's, a sergeant's, and two constable's, uniforms with belts and helmets complete. Also I shall require three men in whom I can place absolute and implicit confidence. They must be big fellows with plenty of pluck and intelligence, and the clothes you get must fit them so that they shall not look awkward in them. They must also bring plain clothes with them, for I shall want two of them to undertake a journey to Ireland. They will each be paid a hundred pounds for the job, and to ensure their silence afterwards. Do you think you can find me the men without disclosing my connection with the matter?"

"I know exactly where to put my hand upon them, sir," remarked Belton, "and for the sum you mention it's my belief they'd hold their tongues for ever, no matter what pressure was brought to bear upon them."

"Very good. You had better communicate with them at once, and tell them to hold themselves in readiness, for I may want them at any moment. On Friday night I shall probably attempt the job, and they can get back to town when and how they like."

"Very good, sir. I'll see about them this afternoon without fail."

Next morning, Belton left London for Liverpool, with the photograph of the mysterious Rooney in his pocket-book. Carne had spent the afternoon with a fashionable party at Hurlingham, and it was not until he returned to his house that he received the telegram he had instructed his valet to send him. It was short, and to the point.

Friends arrived. Reach Euston nine o'clock.

The station clocks wanted ten minutes of the hour when the hansom containing a certain ascetic looking curate drove into the yard. The clergyman paid his fare, and, having inquired the platform upon which the Liverpool express would arrive, strolled leisurely in that direction. He would have been a clever man who would have recognised in this unsophisticated individual either deformed Simon Carne, of Park Lane, or the famous detective of Belverton Street.

Punctual almost to the moment the train put in an appearance, and drew up beside the platform. A moment later the curate was engulfed in a sea of passengers. A bystander, had he been sufficiently observant to notice such a thing, would have been struck by the eager way in which he looked about him, and also by the way in which his manner changed directly he went forward to greet the person he was expecting.

To all appearances they were both curates, but their social positions must have been widely different if their behaviour to each other could have been taken as any criterion. The new arrival, having greeted his friend, turned to two gentlemen standing beside him, and after thanking them for their company during the journey, wished them a pleasant holiday in England, and bade them good-bye. Then, turning to his friend again, he led him along the platform towards the cab rank.

During the time Belton had been speaking to the two men just referred to, Carne had been studying their faces attentively. One, the taller of the pair, if his red hair and watery blue eyes went for anything, was evidently Maguire, the other was Rooney, the man of the photograph. Both were big, burly fellows, and Carne felt that if it ever came to a fight, they would be just the sort of men to offer a determined resistance.

Arm in arm the curates followed the Americans towards the cab rank. Reaching it, the latter called up a vehicle, placed the bags they carried upon the roof, and took their places inside. The driver had evidently received his instructions, for he drove off without delay. Carne at once called up another cab, into which Belton sprang without ceremony. Carne pointed to the cab just disappearing through the gates ahead.

"Keep that hansom in sight, cabby," he said; "but whatever you do don't pass it."

"Keep that hansom in sight, cabby."

"All right, sir," said the man, and immediately applied the whip to his horse.

When they turned into Seymour Street, scarcely twenty yards separated the two vehicles, and in this order they proceeded across the Euston Road, by way of Upper Woburn Place and Tavistock Square.

The cab passed through Bloomsbury Square, and turned down one of the thoroughfares leading therefrom, and made its way into a street flanked on either side by tall, gloomy-looking houses. Leaning over the apron, Carne gazed up at the corner house, on which he could just see the plate setting forth the name of the street. What he saw there told him all he wanted to know.

They were in Bellamer Street, and it was plain to him that the men had determined to thrust themselves upon the hapless Mrs. Jeffreys. He immediately poked his umbrella through the shutter, and bade the cabman drive on to the next corner, and then pull up. As soon as the horse came to a standstill, Carne jumped out, and, bidding his companion drive home, crossed the street, and made his way back until he arrived at a spot exactly opposite the house entered by the two men.

His supposition that they intended to domicile themselves there was borne out by the fact that they had taken their luggage inside, and had dismissed their cab. There had been lights in two of the windows when the cab had passed, now a third was added, and this he set down as emanating from the room allotted to the new arrivals.

For upwards of an hour and a half Carne remained standing in the shadow of the opposite houses, watching the Jeffreys' residence. The lights in the lower room had by this time disappeared, and within ten minutes that on the first floor followed suit. Being convinced, in his own mind, that the inmates were safely settled for the night, he left the scene of his vigil, and, walking to the corner of the street, hailed a hansom and was driven home. On reaching No. 1, Belverton Street, he found a letter lying on the hall table addressed to Klimo. It was in a woman's handwriting, and it did not take him long to guess that it was from Mrs. Jeffreys. He opened it and read as follows:

Bellamer Street,

Thursday Evening.

Dear Mr. Klimo—

I am sending this to you to tell you that my worst suspicions have been realised. The two men whose coming I so dreaded, have arrived, and have taken up their abode with us. For my father's sake I dare not turn them out, and to-night I have heard from my husband to say that he will be home on Saturday next. What is to be done? If something does not happen soon, they will commence their dastardly business in England, and then God help us all. My only hope is in Him and you.

Yours ever gratefully,

Eileen Jeffreys.

Carne folded up the letter with a grave face, and then let

himself into Porchester House and went to bed to think out his

plan of action. Next morning he was up betimes, and by the

breakfast hour had made up his mind as to what he was going to

do. He had also written and dispatched a note to the girl who was

depending so much upon him. In it he told her to come and see him

without fail that morning. His meal finished, he went to his

dressing-room and attired himself in Klimo's clothes, and shortly

after ten o'clock entered the detective's house. Half an hour

later Mrs. Jeffreys was ushered into his presence. As he greeted

her he noticed that she looked pale and wan. It was evident she

had spent a sleepless night.

"Sit down," he said, "and tell me what has happened since last I saw you."

"The most terrible thing of all has happened," she answered, "As I told you in my note, the men have reached England, and are now living in our house. You can imagine what a shock their arrival was to me. I did not know what to do. For my father's sake I could not refuse them admittance, and yet I knew that I had no right to take them in during my husband's absence. Be that as it may, they are there now, and to-morrow night George returns. If he discovers their identity, and suspects their errand, he will hand them over to the police without a second thought, and then we shall be disgraced for ever. Oh, Mr. Klimo, you promised to help me, can you not do so? Heaven knows how badly I need your aid."

"You shall have it. Now listen to my instructions. You will go home and watch these men. During the afternoon they will probably go out, and the instant they do so, you must admit three of my servants and place them in some room where their presence will not be suspected by our enemies. A friend, who will hand you my card, will call later on, and as he will take command, you must do your best to help him in every possible way."

"You need have no fear of my not doing that," she said. "And I will be grateful to you till my dying day."

"Well, we'll see. Now good-bye."

After she had left him, Klimo returned to Porchester House and sent for Belton. He was out, it appeared, but within half an hour he returned and entered his master's presence.

"Have you discovered the bank?" asked Carne.

"Yes, sir, I have," said Belton. "But not till I was walked off my legs. The men are as suspicious as wild rabbits, and they dodged and played about so, that I began to think they'd get away from me altogether. The bank is the 'United Kingdom,' Oxford Street branch."

"That's right. Now what about the uniforms?"

"They're quite ready, sir, helmets, tunics, belts and trousers complete."

"Well then have them packed as I told you yesterday, and ready to proceed to Bellamer Street with the men, the instant we get the information that the folk we are after have stepped outside the house door."

"Very good, sir. And as to yourself?"

"I shall join you at the house at ten o'clock, or thereabouts. We must, if possible, catch them at their supper."

London was half through its pleasures that night, when a tall, military-looking man, muffled in a large cloak, stepped into a hansom outside Porchester House, Park Lane, and drove off in the direction of Oxford Street . Though the business which was taking him out would have presented sufficient dangers to have deterred many men who consider themselves not wanting in pluck, it did not in the least oppress Simon Carne; on the contrary, it seemed to afford him no small amount of satisfaction. He whistled a tune to himself as he drove along the lamplit thoroughfares, and smiled as sweetly as a lover thinking of his mistress when he reviewed the plot he had so cunningly contrived.

He felt a glow of virtue as he remembered that he was undertaking the business in order to promote another's happiness, but at the same time reflected that, if fate were willing to pay him fifty thousand pounds for his generosity, well, it was so much the better for him. Reaching Mudie's Library, his coachman drove by way of Hart Street into Bloomsbury Square, and later on turned into Bellamer Street.

At the corner he stopped his driver and gave him some instructions in a low voice. Having done so, he walked along the pavement as far as No. 14, where he came to a standstill. As on the last occasion that he had surveyed the house, there were lights in three of the windows, and from this illumination he argued that his men were at home. Without hesitation he went up the steps and rang the bell. Before he could have counted fifty it was opened by Mrs. Jeffreys herself, who looked suspiciously at the person she saw before her. It was evident that in the tall, well-made man with iron-grey moustache and dark hair, she did not recognise her elderly acquaintance, Klimo, the detective.

"Are you Mrs. Jeffreys?" asked the newcomer, in a low voice.

"I am," she answered. "Pray, what can I do for you?"

"I was told by a friend to give you this card."

He thereupon handed to her a card on which was written the one word "Klimo." She glanced at it, and, as if that magic name were sufficient to settle every doubt, beckoned to him to follow her. Having softly closed the door she led him down the passage until she arrived at a door on her right hand. This she opened and signed to him to enter. It was a room that was half office half library.

"I am to understand that you come from Mr. Klimo?" she said, trembling under the intensity of her emotion. "What am I to do?"

"First be as calm as you can. Then tell me where the men are with whom I have to deal."

"They are having their supper in the dining-room. They went out soon after luncheon, and only returned an hour ago."

"Very good. Now, if you will conduct me upstairs, I shall be glad to see if your father is well enough to sign a document I have brought with me. Nothing can be done until I have arranged that."

"If you will come with me I will take you to him. But we must go quietly, for the men are so suspicious that they send for me to know the meaning of every sound. I was dreadfully afraid your ring would bring them out into the hall."

Leading the way up the stairs she conducted him to a room on the first floor, the door of which she opened carefully. On entering, Carne found himself in a well-furnished bedroom. A bed stood in the centre of the room, and on this lay a man. In the dim light, for the gas was turned down till it showed scarcely a glimmer, he looked more like a skeleton than a human being. A long white beard lay upon the coverlet, his hair was of the same colour, and the pallor of his skin more than matched both. That he was conscious was shown by the question he addressed to his daughter as they entered.

"What is it, Eileen?" he asked faintly. "Who is this gentleman, and why does he come to see me?"

"He is a friend, father," she answered. "One who has come to save us from these wicked men."

"God bless you, sir," said the invalid, and as he spoke he made as if he would shake him by the hand.

Carne, however, checked him.

"Do not move or speak," he said, "but try and pull yourself together sufficiently to sign this paper."

"What is the document?"

"It is something without which I can take no sort of action. My instructions are to do nothing until you have signed it. You need not be afraid; it will not hurt you. Come, sir, there is no time to be wasted. If these rascals are to be got out of England our scheme must be carried out to-night."

"To do that I will sign anything. I trust your honour for its contents. Give me a pen and ink."

His daughter supported him in her arms, while Carne dipped a pen in the bottle of ink he had brought with him and placed it in the tremulous fingers. Then, the paper being supported on a book, the old man laboriously traced his signature at the place indicated. When he had done so he fell back upon the pillow completely exhausted.

Carne blotted it carefully, then folded the paper up, placed it in his pocket and announced himself ready for work. The clock upon the mantelpiece showed him that it was a quarter to eleven, so that if he intended to act that night he knew he must do so quickly. Bidding the invalid rest happy in the knowledge that his safety was assured, he beckoned the daughter to him.

"Go downstairs," he said in a whisper, "and make sure that the men are still in the dining-room."

She did as he ordered her, and in a few moments returned with the information that they had finished their supper and had announced their intention of going to bed.

"In that case we must hurry," said Carne. "Where are my men concealed?"

"In the room at the end of that passage," was the girl's reply.

"I will go to them. In the meantime you must return to the study downstairs, where we will join you in five minutes' time. Just before we enter the room in which they are sitting, one of my men will ring the front door bell. You must endeavour to make the fellows inside believe that you are trying to prevent us from gaining admittance. We shall arrest you, and then deal with them. Do you understand?"

"Perfectly."

She slipped away, and Carne hastened to the room at the end of the passage. He scratched with his finger nail upon the door, and a second later it was opened by a sergeant of police. On stepping inside he found two constables and an inspector awaiting him.

"Is all prepared, Belton?" he inquired of the latter.

"Quite prepared, sir."

"Then come along, and step as softly as you can."

As he spoke he took from his pocket a couple of papers, and led the way along the corridor and down the stairs. With infinite care they made their way along the hall until they reached the dining-room door, where Mrs. Jeffreys joined them. Then the street bell rang loudly, and the man who had opened the front door a couple of inches shut it with a bang. Without further hesitation Carne called upon the woman to stand aside, while Belton threw open the dining-room door.

"I tell you, sir, you are mistaken," cried the terrified woman.

"I am the best judge of that," said Carne roughly, and then, turning to Belton, he added: "Let one of your men take charge of this woman."

On hearing them enter, the two men they were in search of had risen from the chairs they had been occupying on either side of the fire, and stood side by side upon the hearth rug, staring at the intruders as if they did not know what to do.

On hearing them enter, the two men had risen.

"James Maguire and Patrick Wake Rooney," said Carne, approaching the two men, and presenting the papers he held in his hand, "I have here warrants, and arrest you both on a charge of being concerned in a Fenian plot against the well being of Her Majesty's Government. I should advise you to submit quietly. The house is surrounded, constables are posted at all the doors, and there is not the slightest chance of escape."

The men seemed too thunderstruck to do anything, and submitted quietly to the process of handcuffing. When they had been secured, Carne turned to the inspector and said:

"With regard to the other man who is ill upstairs, Septimus O'Grady, you had better post a man at his door."

"Very good, sir."

Then turning to Messrs. Maguire and Rooney, he said: "I am authorised by Her Majesty's Government to offer you your choice between arrest and appearance at Bow Street, or immediate return to America. Which do you choose? I need not tell you that we have proof enough in our hands to hang the pair of you if necessary. You had better make up your minds as quickly as possible, for I have no time to waste."

The men stared at him in supreme astonishment.

"You will not prosecute us?"

"My instructions are, in the event of your choosing the latter alternative, to see that you leave the country at once. In fact, I shall conduct you to Kingstown myself to-night, and place you aboard the mail-boat there."

"Well, so far as I can see, it's Hobson's choice," said Maguire. "I'll pay you the compliment of saying that you're smarter than I thought you'd be. How did you come to know we were in England?"

"Because your departure from America was cabled to us more than a week ago. You have been shadowed ever since you set foot ashore. Now passages have been booked for you on board the outgoing boat, and you will sail in her. First, however, it will be necessary for you to sign this paper, pledging yourselves never to set foot in England again."

"And supposing we do not sign it?"

"In that case I shall take you both to Bow Street forthwith, and you will come before the magistrates in the morning. You know what that will mean. You had better make up your minds quickly, for there is no time to lose."

For some moments they remained silent. Then Maguire said sullenly: "Bedad, sir, since there's nothing else for it, I consent."

"And so do I," said Rooney. "Where's the paper?"

Carne handed them a formidable-looking document, and they read it in turn with ostentatious care. As soon as they had professed themselves willing to append their signatures to it, the sham detective took it to a writing-table at the other end of the room, and then ordered them to be unmanacled, so that they could come up in turn and sign. Had they been less agitated it is just possible they would have noticed that two sheets of blotting paper covered the context, and that only a small space on the paper, which was of a blueish grey tint, was left uncovered.

Then placing them in charge of the police officials, Carne left the room and went upstairs to examine their baggage. Evidently he discovered there what he wanted to know, for when he returned to the room his face was radiant.

Half an hour later they had left the house in separate cabs. Rooney was accompanied by Belton and one of his subordinates, now in plain clothes, while Carne and another took charge of Maguire. At Euston they found special carriages awaiting them, and the same procedure was adopted in Ireland. The journey to Queenstown proved entirely uneventful; not for one moment did the two men suspect the trick that was being played upon them; nevertheless, it was with ill-concealed feelings of satisfaction that Carne and Belton bade them farewell upon the deck of the outward-bound steamer.

"Good-bye," said Maguire, as their captors prepared to pass over the side again. "An' good luck to ye. I'll wish ye that, for ye've treated us well, though it's a scurvy trick ye've played us in turning us out of England like this. First, however, one question. What about O'Grady?"

"The same course will be pursued with him, as soon as he is able to move," answered the other. "I can't say more."

"A word in your ear first," said Rooney.

He leant towards Carne. "The girl's a good one" he said. "An' ye may do what ye can for her, for she knows nought of our business."

"I'll remember that if ever the chance arises," said Carne. "Now, good-bye."

"Good-bye."

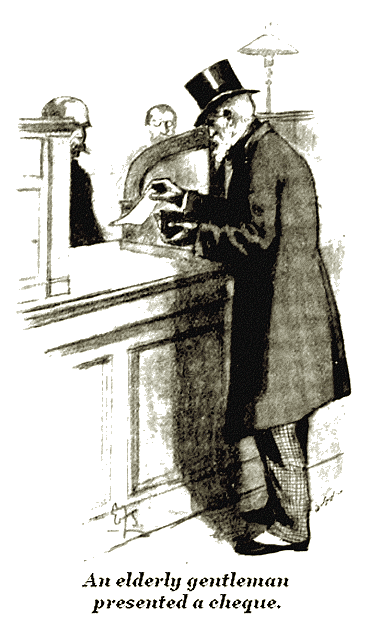

ON the Wednesday morning following, an elderly gentleman, dressed in rather an antiquated fashion, but boasting an appearance of great respectability, drove up in a brougham to the branch of the United Kingdom Bank in Oxford Street, and presented a cheque for no less a sum than forty-five thousand pounds, signed with the names of Septimus O'Grady, James Maguire, and Patrick Rooney, and bearing the date of the preceding Friday.

The cheque was in perfect order, and, in spite of the largeness of the amount, it was cashed without hesitation.

That afternoon Klimo received a visit from Mrs. Jeffreys. She came to express her gratitude for his help, and to ask the extent of her debt.

"You owe me nothing but your gratitude. I will not take a halfpenny. I am quite well enough rewarded now," said Klimo with a smile.

When she had gone he took out his pocket-book and consulted it.

"Forty-five thousand pounds," he said with a chuckle. "Yes, that is good. I did not take her money, but I have been rewarded in another way."

Then he went into Porchester House and dressed for the Garden Party at Marlborough House, to which he had been invited.