RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"A Crime of the Under-Seas,"

Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1905

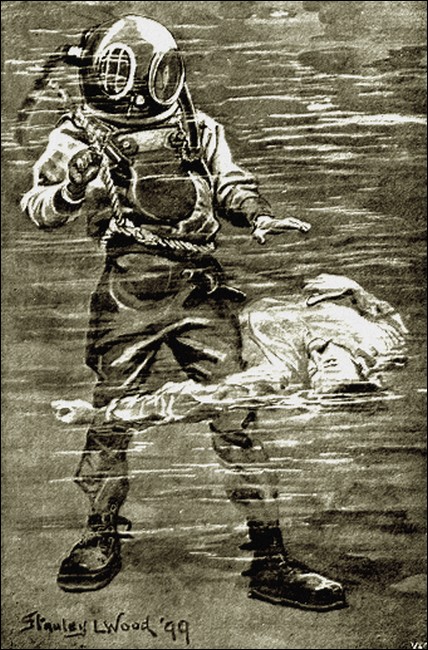

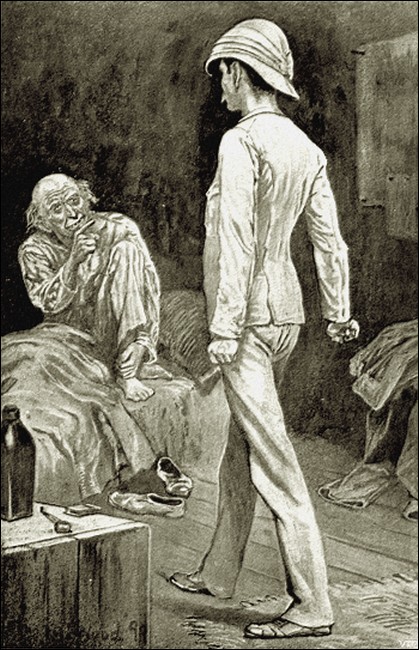

Dropped him again with a cry that echoed in my helmet.

THERE is an old saying that "one half of the world does not know how the other half lives," but how true this is very few of us really understand. In the East, indeed, it amounts almost to the marvellous. There are men engaged in trades there, some of them highly lucrative, of which the world in general has never heard, and which the ordinary stay-at-home Englishman would in all probability refuse to believe, even if the most trustworthy evidence were placed before him.

For instance, on the evening from which I date the story I am now about to tell you, three of us were seated chatting together in the verandah of the Grand Oriental Hotel at Colombo. We were all old friends, and we had each of us arrived but recently in Ceylon. McDougall, the big red-haired Scotchman, who was sitting on my right, had put in an appearance from Tuticorin by a British India boat only that morning, and was due to leave again for Burmah the following night. As far as I could gather he earned his living mainly by smuggling dutiable articles into other countries, where the penalty, if one is caught, is a fine of at least one thousand pounds, or the chance of receiving upwards of five years' imprisonment.

The man in the big chair next to him was Callingway, a Londoner, who had hailed the day before from South America, travelling in a P. and O. steamer from Australia. He was tracking an absconding Argentine Bank Manager, and, as it afterwards transpired, was, when we came in contact with him, on the point of getting possession of the money with which the other had left the country. Needless to say he was not a Government servant, nor were the Banking Company in question aware of his endeavours.

Lastly there was myself, Christopher Collon, aged thirty-six, whose walk in life was even stranger, if such a thing were possible, than those of the two men I have just described. One thing at any rate is certain, and that is that if I had been called upon to give an accurate description of myself and my profession at that time, I should have found it extremely difficult to do so. Had I been the possessor of a smart London office, a private secretary, and half a dozen corresponding clerks, I should probably have called myself a private detective on a large scale, or, as they put it in the advertisement columns of our daily papers, a Private Enquiry Agent. Yet that description would scarcely have suited me; I was that and something more. At any rate it was a pretty hard life, and by the same token a fairly hazardous one.

This will be the better understood when I say that one day I might receive a commission by cablegram from some London firm, who, we will suppose, had advanced goods to an Indian Rajah, and were unable to obtain payment for them. It was my business to make my way to his headquarters as soon as possible, and to get the money out of him by the best means in my power, eating nothing but what was cooked for me by my own servant meanwhile. As soon as I had done with him I might be sent on very much the same sort of errand to a Chinese Mandarin in Hankow or Canton, or possibly to worry a gold mining concession, or something of the sort, out of one of the innumerable Sultans of the protected Malayan States, those charming places where the head of the State asks you to dinner at six and you are found at midnight with six inches of cold kris in your abdomen.

On one occasion I remember being sent from Singapore to Kimberley at three hours' notice to meet and escort a Parsee diamond merchant from that town to Calcutta. And what was funnier still, though we travelled to Cape Town together, and even shared the same cabin on board the steamer afterwards, he never for an instant suspected that I was spying upon him. Oftentimes I used to wonder what he would have thought, had he only guessed that I knew he was carrying upwards of a million pounds worth of diamonds in the simple leather belt he wore next to his skin, and that every night I used, when he was asleep, to convince myself that everything was right and that the stones were still there. His was a precious life that voyage, at least so his friends in Calcutta thought, and if I could only tell you all that happened during our intercourse, you would not wonder that I was glad when we reached India, and I had handed him over to the chief partners of his firm.

But there, if I were to go on telling you my adventures, I should be talking from now to Christmas. Rather let me get to the matter in hand, beside which everything I had ever attempted hitherto ranks as nothing. When I have done I think you will admit that the familiar saying, embodied in my first sentence, should be altered from "one half the world does not know how the other half lives" to "one half the world does not know how the other half gets its living." There is a distinction with a good deal of difference.

I have often thought that there is no pleasanter spot in this strange old world of ours than the Grand Oriental Hotel, Colombo. Certainly there is not a more interesting place. There the student of character will have sufficient examples before him to keep him continually at work. Day and night vessels of all sorts and descriptions are entering the harbour, hailing from at least three of the four known quarters of the globe. At all hours men and women from Europe, from India, from Malaysia, from the further East, from Australia, and also from the Southern Seas and America via Australia, troop in and out of that hospitable caravanserai.

On this particular occasion, having talked of many things and half a hundred times as many places, we had come back to the consideration of our lives and the lack of home comforts they contained.

"If I could only see my way clear I'd throw it up, marry, and settle down," said Callingway; "not in England, or Scotland, or America, for that matter; but, to my thinking, in the loveliest island in the world."

"And where may that be?" I inquired, for I had my own ideas on the subject.

"Tasmania," he answered promptly. "The land of the red-faced apple. I know a little place on the Derwent that would suit me down to the ground."

"I'd na gae ye a pinch of snuff for it," said McDougall, with conviction. "What's life worth to a man in them hole-and-corner places? When I've done wi' roamin' it's in my mind that I'll set myself down at a little place I ken the name of, fifty miles north of the Clyde, where there's a bit of fishing, and shootin', and, if ye want it, well, just a drappie of the finest whuskey that was ever brewed in old Scotie. It's ma thinkin' I've ruined ma digestion wi' all these outlandish liquors that I've been swallowin' these twenty years gone. Don't talk o' your Tasmanias to me. I'm nae fond o' them. What have you to say, Mr. Collon?"

"You needn't be afraid. I'll not settle down as long as I can get about," I answered. "If you fellows are tired of your lives I'm not, and I'm certain of this much, Callingway, by the time you've been installed in your Tasmanian home twelve months, and you, McDougall, have been on your Scotch estate the same length of time, you'll both be heartily sick of them and wishing yourselves back once more in the old life out here."

"Try me, that's all," replied Callingway fervently. "Think what our present life is. We are here to-day and gone to-morrow. We've not a foot of earth in the whole wide world that we can call our own. The only home we know is a numbered room in a hotel or a cabin aboard a ship. We never know when we get up in the morning whether by nightfall we shall not be lying stark and cold shot through the heart, or with six inches of cold steel through our lungs. Our nerves from year's end to year's end are strained to breaking pitch, and there's not a single decent woman to be found amongst the whole circle of our acquaintances. After all, a wife's——"

"The lasses, the lasses, I agree with ye," interrupted McDougall without ceremony. "After all 'tis the lasses who make the joy o' livin'. Hear what Robbie says:—

"'Health to the sex! ilk guid chiel says,

Wi' merry dance in winter days,

An' we to share in common:

The gust o' joy, the balm o' woe,

The soul o' life, the Heav'n below,

Is rapture-giving woman.'"

"If you're going to get on that strain you're hopeless," I said. "When Callingway begins to think it is time for him to settle down, and you, McDougall, start quoting Burns, then I come to the conclusion that I'd better bid you good-night."

As I spoke a "ricksha" drew up at the steps, and, when the coolie had set down his shafts, an elderly gentleman alighted. Having paid the man his fare he entered the verandah, and so made his way into the house. I had got so accustomed to new arrivals by this time that, beyond thinking what a good picture of the substantial old English merchant this one would have made, I did not pay much attention to him.

"Well," said Callingway, after the few minutes' pause which followed up my last remark, "I think I will ask you gentlemen to drink another whiskey and soda to my success, and then I will leave you and retire to my virtuous couch. My confounded boat sails at six o'clock to-morrow morning, and if I don't sail in her I shall lose the society of a most estimable gentleman whom I am accompanying as far as Hong Kong. As it looks like being a profitable transaction I've no desire he should give me the slip."

He touched the bell on the table at his side, and when the boy arrived to answer it, ordered the refreshment in question. We drank to his success in the business he was about to undertake, and then both he and McDougall bade me good-night and retired, leaving me alone in the verandah. It was a lovely evening, and as I was not at all in the humour for sleep I lit another cheroot and remained on where I was, watching the glimmering lights in the harbour beyond, and listening to the jabbering of the "ricksha" boys on the stand across the road.

As I sat there I could not help thinking of the curious life I was leading, of the many strange adventures I had had, and also of my miraculous escapes from what had seemed at the time to be almost certain death. Only that very day I had received an offer by telegram from a well-known and highly respected firm in Bombay inviting me to undertake a somewhat delicate piece of business in the Philippine Islands. The price offered me was, in every sense of the word, a good one; but I detested Spanish countries so much that if anything better turned up I was prepared to let the other fall through without a second thought. But one has to live, even in the East, and for this reason I did not feel justified in throwing dirty water away before I had got clean.

As these thoughts were passing through my mind I distinctly heard some one step into the verandah from the door on my right, and a moment later, to my surprise, the stout old gentleman who, half an hour or so before, I had thought so typical of an English merchant, came round the chairs towards me. Having reached the place where I was sitting he stopped, and, taking a cheroot from his pocket, proceeded to light it. During the operation I noticed that he took careful stock of me, and, when he had finished, said quietly:—

"Mr. Collon, I believe?"

"That is my name," I answered, looking up at him through the cloud of smoke. "Pray how do you come to be acquainted with it?"

"I have heard of you repeatedly," he replied.

"Indeed," I said. "And pray is there any way in which I can be of service to you?"

"I think so," he replied, with a smile. "As a matter of fact, I have just arrived from Madras, where, hearing in an indirect way that you were supposed to be in Ceylon, I undertook this journey on purpose to see you."

"Indeed!" I answered, with considerable surprise. "And pray what is it you desire me to do for you?"

"I want you to take charge of what I think promises to be one of the most extraordinary and complicated cases even in your extensive repertoire," he said.

"If it is as you say, it must indeed be a singular one," I answered. "Perhaps it would not give you too much trouble to furnish me with the details."

"I will do so with the greatest pleasure," he replied. "If you will permit me to take my seat beside you, you shall hear the story from beginning to end. I think, then, that you will agree with me that, provided you undertake it, it will, as I insinuated just now, in all probability prove the most sensational, as well as the most lucrative, case in which even you have hitherto been engaged."

Thereupon he seated himself beside me, and told the following remarkable story.

"IN the first place, Mr. Collon," said the old gentleman, who had shown himself so anxious to obtain my services, "I must introduce myself to you. My name is Leversidge, John Leversidge, and I am the junior partner of the firm of Wilson, Burke & Leversidge, of Hatton Garden, Paris, Calcutta, and Melbourne. We are, as you will have gathered from our first address, diamond and precious stone merchants, and we do a very large business in the East generally; also among the Pacific Islands and in Australia. With the two last named our trade is confined principally to pearls and gold, neither of them having very much in the way of gems to offer. Still their connection is worth so much to us as to warrant us in keeping two buyers almost continuously employed; a fact, I think, which speaks for itself. Now it so turned out that some six months or so ago we received a cablegram in London announcing the fact that an enormous black pearl, in all probability the finest yet brought to light, had been discovered near one of the islands to the southward of New Guinea. It had been conveyed first to Thursday Island, which, as perhaps you are aware, is the head and centre of this particular industry in Australian waters, and later on, with a considerable amount of secrecy, to Sydney, where our agent, a man in whom we had the greatest trust, made it his business to see it on our behalf. The result was a cypher cablegram to our firm in London, to say that the jewel was, as far as his knowledge went, absolutely unique, and that in his opinion it behoved us to purchase it, even at the exorbitant price asked for it by the rascally individual into whose hands it had now fallen. This was a person by the name of Bollinson, a half-bred Swede I should say by the description we received of him; though, for my part, from the way he treated us, I should think Jew would be somewhat nearer the mark. Whatever his nationality may have been, however, the fact remains that he knew his business so well, that when we obtained possession of the pearl, which we were determined to have at any price, we had paid a sum for it nearly double what we had originally intended to give. But that mattered little to us, for we had the most perfect confidence in our servant, who had had to do with pearls all his life, and who since he had been in our employ had been fortunate enough to secure several splendid bargains for us. So, to make a long story short, when he cabled the price—though I must confess we whistled a little at the figure—we wired back: 'Buy, and bring it home yourself by next boat,' feeling convinced that we had done the right thing and should not regret it. Now, as you know, there is to be an Imperial wedding in Europe in six months' time, and as we had received instructions to submit for his inspection anything we might have worthy of the honour, we felt morally certain that the sovereign in question would take the jewel off our hands, and thus enable us to get our money back and a fair percentage of interest, besides repaying us for our outlay and our trouble. Sure enough next day a message came in to us to say that our agent had completed the sale and was leaving for England that day, not via Melbourne and Adelaide, as we had supposed, or via Vancouver, which would have been the next best route; but by way of Queensland, the Barrier Reef, and the Arifura Sea, which was longer, and, as we very well knew, by no means so safe. Then he added the very significant information that since he had had the pearl in his keeping no less than three separate and distinct attempts had been made by other people to obtain possession of it. All that, you must understand, happened eight weeks ago. I was in London at the time, and can therefore give you the information first hand."

"Eight weeks exactly?" I asked, for I always like to be certain of my dates. Many a good case that I have taken in hand has collapsed for the simple reason that the parties instructing me had been a little slipshod in the matter of their dates.

"Eight weeks to-morrow," he answered. "Or rather, since it is now past midnight, I think I might say eight weeks to-day. However, in this particular instance the date does not happen to be of much importance."

"In that case I must beg your pardon for interrupting you," I said. "You were saying, I think, that your agent reported that, before he left Sydney, no less than three attempts were made by certain parties to obtain possession of the pearl in question."

"That was so. But it is evident that he managed to elude them, otherwise he would have cabled again to us on the subject."

"Did you then receive no further message from him?"

"Only one from Brisbane to say that he had joined the mail- boat, Monarch of Macedonia, at that port, and would sail for England in her that day."

On hearing the name of the vessel I gave a start of surprise, and I might almost say of horror. "Good heavens!" I cried; "do you mean to say he was on board the Monarch of Macedonia? Why, as all the world knows by this time, she struck a rock somewhere off the New Guinea Coast and went to the bottom with all hands but two."

The old gentleman nodded his head. "Your information is quite correct, my dear sir," he said. "In a fog one night between eleven and twelve o'clock, she got in closer to the New Guinea Coast than she ought to have done, and struck on what was evidently an uncharted rock, and sank in between fifteen and twenty fathoms of water. Of her ship's company only two were saved, a foremast hand and a first saloon passenger, the Rev. W. Colway-Brown, a clergyman from Sydney. These two managed, by some extraordinary means, to secure a boat, and in her they made their way to the shore, which was between thirty and forty miles distant. Here they dwelt for a few days in peril of their lives from the natives, and were ultimately picked up by a trading schooner called The Kissing Cup, whose skipper carried them on to Thursday Island, where they were taken in and most kindly cared for."

"And your agent? Did you learn anything of his fate?"

"Nothing that was likely to be of any comfort to us," said the old fellow sadly. "We telegraphed as soon as we heard the news, of course, first to the agents in Brisbane, who, to prove that he sailed on board the vessel, wired us the number of his cabin, and then to the Rev. Colway-Brown, who was still in Thursday Island. The latter replied immediately to the effect that he remembered quite well seeing the gentleman in question on deck earlier in the evening, but that he saw nothing of him after the vessel struck, and could only suppose he must have been in bed when the accident happened. It was a most unhappy affair altogether, and, as you may suppose, we were not a little cut up at the loss of our old servant and trusted friend."

"I can quite believe that," I answered. "And now what is it you want me to do to help you?"

Mr. Leversidge was silent for a few seconds, and thinking he might be wondering how he should put the matter to me I did not interrupt him.

"Well, Mr. Collon," he said, after a few moments' thought, "what we want you to do for us, is to proceed with me to the scene of the wreck as soon as possible, and to endeavour to obtain from her the pearl which our agent was bringing home to us. Your reputation as a diver is well known to us, and I might tell you that directly the news of the wreck reached us we said to each other, 'That pearl must be recovered at any cost, and Christopher Collon is the man for the work.' We will, of course, pay all expenses connected with the expedition. Will you therefore be good enough to tell me if you will undertake the work, and if so, what your charge will be?"

Many and strange as my adventures had hitherto been, and curious (for that is the most charitable term, I think) as were some of the applications I had had made to me in my time, I don't think I had ever been made such an extraordinary offer as that brought under my notice by the old gentleman who had so unexpectedly come in search of me. He had not been far from the mark when he had said that this was likely to be one of the strangest cases that had ever come under my observation. Of one thing I was firmly convinced, and that was that I was not going to give him a decided answer at once. I did not know how my ground lay, and nothing was to be gained by giving my promise and being compelled to withdraw it afterwards. Besides, before I pledged myself, I wanted to find out how I stood with the law in the matter of the ship herself. I had no sort of desire to board her and bring off the jewel, and then find it advertised in all the papers of the world and myself called into court on a charge of wrecking or piracy, or whatever the particular term might be that covers that sort of crime.

"You must give me time to think it over," I said, turning to the old gentleman beside me. "I want to discover my position. For all I know to the contrary I may be lending myself to a felony, and that would never do at all. Everybody is aware that the more adventures a jewel goes through the more valuable it becomes. On the other hand the arm of the law reaches a long way, and I am not going to be the cat that pulls your chestnuts out of the fire and burns her paws in so doing. That would scarcely suit Christopher Collon, however nice it might be for other people."

"My dear sir," replied Mr. Leversidge, "you need have no fear at all on that score. We have no desire to incriminate you or to hurt your interests in any possible way. I shall take charge of the affair myself, and that should be sufficient guarantee that we are not going to run any undue risk. I have both my public and my private reputation at stake, and for my own sake you may be sure I shall take very good care that we do not come into collision with the law. The good name of my firm is also in the balance, and that should count for something. No, my dear sir, the most rigid and absolute secrecy will be maintained, and the arrangements will be as follows: If you are agreeable, and we can come to terms, we shall charter a vessel, if possible, in Batavia, fit her out with the necessary appliances, and sail in her with all speed to the spot where the catastrophe happened. Then you will descend to the vessel, discover our agent's luggage, which is certain to be in his cabin, we shall draw it up to the surface, examine it, obtain the pearl, and having done so sail again for Batavia, where the amount upon which we shall have agreed will be paid to you. After that we must separate; you will go your way, I shall go mine, and not a living soul will be the wiser."

"That's all very well, but what about the officers and crew of the vessel we charter? Do you think they will not suspect; and how do you propose to square them?"

"We will do that, never fear. They will be certain to believe, from the confident way in which we act, that we have the right to visit the vessel. Besides, when we have once parted from them, we shall never see them again. No, I do not think you need be afraid of them. Come, what do you say?"

"I don't know what to say," I answered. "I'm not sure whether it would be worth my while to touch it. The risk is so great, and I've got another offer on hand just now that looks as if it might turn out well. All these things have to be considered before I can give you an answer."

"Naturally," he replied. "But still I trust you will see your way to helping us. Your skill as a diver is well known, and I pay you the compliment of believing that you have one of the rarest of all gifts, the knowledge of how to hold your tongue when it is necessary. Just think it over and acquaint me with your decision in the morning."

"Very good," I answered. "I will do so. You shall have my answer after breakfast, without fail."

"I am glad to hear it, and I thank you. Now, good-night."

"Good-night," I answered, and after that we separated to go to our respective rooms.

By five o'clock next morning, after a troubled night, I had made up my mind. If the old gentleman would give the terms I wanted, I would do what he asked. Half of the amount was to be paid before we left Colombo, and the balance on our return to Batavia, or on the completion of our work, provided it did not last more than six months. All expenses were to be defrayed by his firm, and a document was to be given me, exonerating me from all blame should the law think fit to come down upon us for what we were doing. All this I embodied in a letter which I copied and sent to Mr. Leversidge's room while he was dressing.

After breakfast he found me in the verandah.

"Many thanks for your note," he said promptly. "I shall be most happy to agree to your terms. We will settle them at once, if you have no objection."

"That is very kind of you," I answered; "but why this great hurry?"

"Because we must leave in the mail-boat this afternoon for Batavia, via Singapore," he replied. "As you will see for yourself, there is no time to be lost."

IN every life there are certain to be incidents, often of the most trivial nature possible, which, little as we may think so at the time, are destined to remain with us, indelibly stamped upon our memories, until we shuffle off this mortal coil. As far as my own existence is concerned, I shall always remember the first view we obtained of Tanjong Priok, as the seaport of Batavia is called, on the day we arrived there from Singapore, engaged on the most extraordinary quest in which I had ever taken part. It was towards evening, and the sky, not merely the western, but indeed the whole length and breadth of the heavens, was suffused with the glorious tints of sunset. Such another I do not remember ever to have seen. In these later days, whenever I look back on that strange adventure, the first thing I see pictured in my mind's eye is that Dutch harbour with its shiny green wharves on one hand, its desolate, wind-tossed cocoa- nut trees upon the shore on the other, and that marvellously beautiful sky enveloping all like a blood-red mantle.

The voyage from Ceylon to Singapore, and thence to Java, calls for no special comment, save that it was accomplished at the maximum of speed and the minimum of convenience. So great, however, was Mr. Leversidge's desire to get to the scene of the disaster, that he could scarcely wait even for the most necessary preparations to be made. The whole way from Colombo to Singapore he grumbled at the speed of the vessel, and when we broke down later on off the coast of Sumatra, I really thought he would have had a fit. However, as I have said before, we reached it at last, and despite the catastrophe, in fairly good time. Having done so, we went ashore, and, acting on my advice, installed ourselves at the Hotel de Nederlander. There are few more beautiful places in the world than Java, and few where I would less care to spend my life. It was Leversidge's first visit to the island, however, and, as is usual in such cases, its beauty exercised a powerful effect upon him. Java is like itself and nothing else in the whole scope of the Immemorial East.

Once we were settled we began to think about our preparations for accomplishing the last part of our singular journey, namely, our voyage to the wreck. It was a delicate bit of business, and one that had to be undertaken in a careful manner in order that no suspicions might be aroused. The Dutch Government is as suspicious as a rat, and a great deal more watchful than most people give it the credit of being. If space permitted, which it does not, I could furnish you with tangible evidence on this head.

"What do you intend doing first?" I had inquired of Mr. Leversidge, on the evening of our landing, when we sat together after dinner in the verandah outside our bedrooms.

"To-morrow morning I shall commence my inquiries for a vessel to carry us on," he answered. "I do not, of course, in accordance with the promise I gave you, desire to compromise you in any way, but if you would give me a few hints as to the way in which I should proceed, I should be very grateful to you. This is the first time I have been in Java, and naturally I am not familiar with the ropes."

"I'll do all I can for you, with great pleasure," I replied; "on the understanding, of course, that I take none of the responsibility. In the first place, you will want a smart little vessel that will get us down to the spot as quickly as possible. Then you will have to hire your diving gear, pumps, dress, etc., and these, as my life and the entire success of the business will depend upon them, must be of the very first quality. Having secured your boat, you must find a trustworthy skipper and crew. She must be provisioned, and when all that has been done, you must arrange to get away from Tanjong Priok without a soul here being the wiser as to what occasions your hurry. I take it that that is a fair summary of the case?"

"You have hit it exactly," he answered; "but I'm afraid it's rather more difficult than you suppose. In the first place, I want to be certain of my man before I go to him. I don't want to make a false step and find myself confronted with a person who will not only refuse to entertain my request point-blank, but will inform the Government as soon as my back is turned of my intentions. That would ruin everything."

"Well, if you want a man from whom you can make inquiries," I answered, "and at the same time feel safe in so doing, I think I can put you on the track of one. I've got his card in my bag now, and to-morrow morning I'll give it to you. One thing is very certain: if there is any one on this island who can help you, he is that man. But don't let him get an inkling that you're after pearls, whatever you do, or he'll want to stand in with you, as sure as you're born, or sell you to the Government if you don't let him have his own way. I know for a fact that he owns a fleet of schooners, all built for speed, though I expect when you ask him he will deny knowing anything at all about them. They're fitted up with the latest appliances in the way of pumps and gear, but I know nothing of the crews they carry. You must look after them yourself, only be very careful and keep your eyes open. Remember that every man about here is a sailor, or pretends to be. Oftener, however, he is as big a rascal as can be found in the East, and would not only play you false as soon as look at you, but would slit your throat on the first convenient opportunity, if for no other reward than to see how pretty you look while he is doing it. I've had to do with them for more years than I like to count, and I speak from experience. Now, with your permission, I'll be off to bed. I'll give you the fellow's address to-morrow morning."

"Many thanks," he said. "I am sincerely grateful to you for the help you have rendered me."

"Don't mention it. I only hope it may prove of real service to you. Good-night."

"Good-night, my dear sir," he answered. "Good-night. I trust that we have now definitely started on our work, and that we are on the threshold of great events."

Early next morning, that is to say after the early breakfast, which is served either in the bedrooms or in the verandahs, as visitors may prefer, I handed the old gentleman the card of the individual to whom I had referred on the previous evening, and he immediately set off in search of him. While he was gone I thought I would take a stroll down town and find out what was doing, so, donning my solar topee, I lit a cigar and set off. I had an old friend, who could tell me all I wanted to know—a man I had often found useful—and, what was better still, one whom I had impressed some time since with the belief that it would be by no means advisable to attempt to play fast and loose with me. He was a curious old fellow, of the name of Maalthaas, and claimed to be a Dutchman. But I happened to be aware that this was not his name; he was a native of Southern Germany, and had originally run away to escape military service. He dwelt at the top of a curious building in the main thoroughfare of the native town, the lower portion of which was inhabited by Chinamen, and it was his boast that he knew more of what was going on in the further East than even Li Chung Tang himself.

I found him in the act of getting out of bed, and he looked as if he were suffering a recovery from a heavy opium bout, to which little excesses he was very partial. When I opened the door, he greeted me without showing the least surprise. A funnier little dried-up skin-and-bone creature no one could have desired to see.

"Mynheer Collon?" he said, or rather gasped, for he was always asthmatical. "I somehow expected I should see you this morning."

"Then your expectation is realized," I answered. "I happened to be in Batavia, so I thought I would look you up. It is months since I last set eyes on you."

"But why did you leave Colombo so suddenly, Mynheer?" he asked inquisitively, disregarding the latter portion of my speech. "And how does it come about that you did not accept that offer to squeeze the dollars out of that tobacco firm in the Philippines?"

"How the deuce do you know anything about that?" I asked in surprise, for it must be borne in mind that that business had been negotiated in the strictest secrecy, and I had no idea that any one else, save the parties mostly concerned, had any inkling of it, much less this withered-up old mummy in Java, who sat on his bed screwing his nutcracker face up into what he thought was a pleasant smile.

"I am old, and deaf, and blind as a bat," he answered; "but I am young enough to have my wits about me. My ears are always open for a bit of gossip, and blind as I am I can see as far into the world as my neighbours."

"You've got wonderfully sharp eyes, Daddy," I replied. "Everybody knows that. And what's more, you never make a mistake, do you? If I were as clever as you are I'd start opium smuggling in Formosa to-morrow, and make a fortune out of it."

Now it so happened that this very industry was the only real failure the old man had had in his life, or, to be more exact, it was the only failure which had ever come to light. In consequence he was the more sensitive about it.

"You think yourself very clever, don't you?" he asked, "but you're not quite as clever as old Maalthaas yet. For all he's so old he still has his wits about him. Supposing he could tell you your errand here, and why that white-haired old English merchant, Leversidge, is with you, eh?"

"What do you know about Leversidge, you old wizard?" I cried; not, however, without a little feeling of nervousness, as I thought of what the consequences might be if this old rascal became aware of the game we were playing and of the necessity that existed for secrecy.

"A good deal more than you think," he answered, with a sly chuckle. "When Hatton Garden takes Christopher Collon in tow, their little game is worth watching, it seems to me. At any rate, it's worth seeing if you can discover the reason of it all."

"It is just possible it might gratify your curiosity," I said, "but for my own part I don't see exactly where the benefit would come in. They pay me fairly well; still ——"

"Still not the full value of the pearl?" he cried. "That's what you were going to say, I suppose?"

The start I could not prevent myself from giving must have shown him that he had scored a bull's-eye. But I recovered myself almost instantly, and by that time had made up my mind as to the course I should pursue. "No, I don't suppose it is the full value of the pearl," I answered. "It's hardly likely it would be. Still, we must live, and, as perhaps you know, business has not been very brisk of late. How have you been doing yourself?"

"Nothing at all," he answered; and then added significantly, "I'm looking out for something now. 'Make hay while the sun shines,' is my motto, and I've always found it a good one."

"I'm sorry, then, that I can't help you to anything," I said. "If I could you know I'd go out of my way to do so, don't you?"

Once more he glanced at me and chuckled. From what I knew of his ways, I could see that there was some mischief still to come.

"You were always grateful for a little help, my boy, weren't you? We've had many a good bit of business together at one time or another, if my poor old memory serves me. It is just possible now that I can do you a good turn, but I'm a poor man, and I want something for my trouble."

"What can you do for me?" I asked, as I searched his crafty old face with my eyes, in the hopes of getting some inkling of what he had in his mind.

"I can give you a warning about this present bit of work of yours," he said. "It may save you a lot of trouble, and not only trouble but a bit of danger, too, if what I hear is correct."

"The deuce you can!" I said; "and pray, what may that warning be?"

"Not too fast, my friend," he answered. "Before I tell you I want my return. Give me the information I ask, and you shall know all I've got to tell. It's worth hearing, I give you my word."

"Well, what is it you want to know? I've trusted you before, and I don't mind doing so again. Ask your question and I'll answer it. But if you get up to any larks, or play me false, why just you look out for yourself, that's all."

"I'm not going to play you false," he answered, with another contortion of his face. "What I want to know is, when you induced the Sultan of Pela-Pelu to hand you over that Portugee chap, for whom the Tsungli-Yamen in Pekin offered that reward, what was the threat you used? I've got a little game to play there, and I want to be able to pinch him so as to make him squeal in case he refuses me. Tell me how you managed it, and I'll give you the information you need."

Before I answered him I took a minute or so to consider my position. I did not want to betray my secret unless I was absolutely compelled to do so, and yet I had good reason for believing that the old fellow would not have hinted that there was something I ought to know, unless his news were worth the telling. However, at last I made up my mind, took out my pocket- book and turned up a certain entry.

"There it is," I said, as I handed it to him to read. "I got that information first hand, so I know it can be relied upon. I threatened him with exposure, and though he was very high up the tree before, he soon climbed down."

Maalthaas read what was written on the page twice over, and then scribbled a few notes on a piece of paper, which he took from under his pillow. Having done so, he handed me back the book, which I pocketed.

"Now what have you got to tell me?" I inquired.

"First answer me one question," he said. "You're off to the wreck of the Monarch of Macedonia, are you not?"

"I'm not going to say whether we are, or are not," I answered; "but suppose, for the sake of argument, we are. What then?"

He leaned a little closer towards me, and his crafty old eyes twinkled in his head like two brilliant stars.

"In that case," he said, "my advice is, make haste, for you may be sure of one thing, and that is that you're not the first."

"What the deuce do you mean? Why are we not the first?"

"I sprang to my feet on hearing this. 'Not the first!' I cried." "Because a schooner started yesterday for the wreck, with a full diving plant aboard. Jim Peach is running the show, and he has Yokohama Joe with him."

I sprang to my feet on hearing this. "Not the first!" I cried.

I did not wait to hear any more, but picking up my hat made for the door, and before you could have counted fifty was flying up the street at my best speed. Jim Peach had beaten me once before, he was not going to do so again if I could help it.

AS I reached the hotel again after my interview with that crafty old rascal, Maalthaas, I saw Mr. Leversidge entering it by another gate. I hurried after him and just managed to catch him as he was crossing the verandah to pass into his own sitting-room. He turned sharply round on hearing my step behind him, and one glance at my face must have told him that there was something the matter. His face turned pale, and I noticed that his mouth twitched nervously.

"What is it?" he asked breathlessly. "What is it you have to tell me? I can see there is something wrong by your face."

"There is indeed something wrong," I answered. "Come inside and let me tell you. I hurried back on purpose to let you know at once."

"I am obliged to you," he said. "Now come inside. Your face frightens me. I fear bad news."

"It is not good news I have to tell you, I'm afraid," I replied. "But still, if we're sharp, we may be able to remedy the mischief before it's too late. First and foremost you must understand that this morning I called upon an old friend who lives here, one of the sharpest men in the East, if not the very sharpest. He's a man who knows everything; who would in all probability be able to tell you why that Russian cruiser, which was due in Hong Kong last Friday, at the last moment put back to Vladivostok, though she did not require coal, and had nothing whatever the matter with her. Or he will tell you, as he did me, the reasons which induced a certain English jewel merchant to hasten to Colombo from Madras, and then come on to Java in company with a man named Christopher Collon."

"Do you mean to say that our business here is known to people?" he cried in alarm. "In that case we are ruined."

"Not quite, I think," I answered; and then with a little boastfulness which I could not help displaying, I added, "In the first place it is not known to people. Only to one person. In the second, Maalthaas may play fast and loose with a good many folk, but he dares not do so with me. I carry too many guns for him, and we are too useful to each other to endeavour in any way to spoil each other's games. But for him I should never have known what has happened now until it would have been too late to remedy it."

"But you have not yet told me what has happened," said Mr. Leversidge in an aggrieved tone.

"Well, the fact of the matter is," I said, "while we have been congratulating ourselves on our sharpness, we have very nearly been forestalled in what we intended doing. In other words, we are not so early in the field as we thought we were."

"What do you mean? Not so early in the field. Do you mean to tell me there is some one else trying to do what we are going to do? That some one else is setting off for the wreck?"

"I do," I answered, with a nod of the head. "You have just hit it. A schooner left Tanjong Priok yesterday with a diver aboard, and as far as I can gather—and there seems to be no doubt about the matter—she was bound for the wreck."

"Do you mean a Government vessel? Surely she must have been sent by the authorities?"

"I don't mean anything of the sort," I said. "The only authority she is sent by is Jim Peach, one of the sharpest men in these waters. And when I tell you that he is aboard her, and that he has Yokohama Joe, the diver, with him, I guess you'll see there's real cause for alarm. At any rate, Mr. Leversidge, it's my opinion that if we're not there first we may as well give up all thought of the pearls, for they'll get them as sure as you're born—don't you make any mistake about that. I've never known Jimmy Peach fail in what he undertook but once. He's a bad 'un to beat is Jimmy. He knows these waters as well as you know Oxford Street, and if, as I expect, it's his own schooner he's gone in, then we shall have all our time taken up trying to catch her."

As I said this the old gentleman's face was a study. Expressions of bewilderment, anxiety, greed, and vindictiveness seemed to struggle in it for the mastery. It was evident that, brought up as he had been with a profound respect for the sacred rights of property, it was impossible for him to believe that the man could live who would have the audacity to behave towards him, John Leversidge, of Hatton Garden, as Peach and his gang were now said to be doing. He clenched his fists as he realized that the success of the enterprise depended entirely upon our being able to beat the others at their own game, and from the gleam I saw in his eye I guessed that there was not much the old boy would not do and dare to get possession of what had been bought and paid for by his firm, and what he therefore considered to be his own lawful property.

"If it is as you say, Mr. Collon," he said, at length, "there can be no possible doubt as to what sort of action we should take. Come what may we must be on the spot first. I believe I am doing as my firm would wish when I say that those other rascals must be outwitted at all costs. If this man you speak of, this Peach, is a bad one to beat, let me tell you so am I. We'll make a match of it and see who comes out best. I can assure you I have no fear for the result."

"Bravely spoken," I said. "I like your spirit, Mr. Leversidge, and I'm with you hand and glove. I've beaten Jimmy before, and on this occasion I'll do so again."

"I only hope and trust you may," he answered. "And now what do you advise? What steps should we take first? Give me your assistance, I beg, for you must of necessity be better versed in these sort of matters than I. It seems to me, however, that one thing is very certain: if these men sailed yesterday in their schooner, and they have a day's start of us, we shall find it difficult to catch them. We might do so, of course; but it would be safer to act as if we think we might not. For my own part I do not feel inclined to run the risk. I want to make it certain that we do get there before them."

"The only way to do that is, of course, to charter a steamer," I replied, "and that will run into a lot of money. But it will make it certain that we get the better of them."

"In such a case money is no object. We must keep our word to the Emperor, and to do that my firm would spend twice the sum this is likely to cost. But the question is, where are we to find the steamer we want? I found it difficult, nay, almost impossible, to get even a schooner this morning. And for the only one I could hear of the owner asked such a preposterous price that I did not feel disposed to give in to his demands until I had consulted you upon the subject, and made certain that we could not find another. What do you recommend?"

I considered the matter for a moment. I had had experience of Java ship-owners before, and I knew something of their pleasant little ways. Then an idea occurred to me.

"I think if you will let me negotiate the matter, Mr. Leversidge," I said, "I may be able to obtain what you want. The man of whom I spoke to you just now, the same who gave me the information regarding Peach and his party, is the person to apply to. For a consideration I have no doubt he would find us a vessel, and though we may have to pay him for his trouble, he will take very good care that we are not swindled by any other party. There is one more suggestion I should like to make, and that is that you should let me telegraph to a person of my acquaintance in Thursday Island to send a schooner down to a certain part of the New Guinea coast, in charge of men he can trust. We could then on arrival tranship to her, and send the steamer back without letting those on board know anything of our errand. What do you think of that arrangement? In my opinion it would be the best course to pursue."

"And I agree with you," he answered. "It is an admirable idea, and I am obliged to you for it. We will put it into execution without loss of time. As soon as you have seen this man Maalthaas we will send the message you speak of to Thursday Island."

"I will see him at once," I replied. "There is no time to be lost. While we are talking here that schooner is making her way to the scene of the catastrophe as fast as she can go."

I accordingly departed, and in something less than a quarter of an hour was once more seated in the venerable Maalthaas' room. It did not take long to let him know the favour we wanted of him, nor did it take long for him to let me understand upon what terms he was prepared to grant it. "You won't come down in your price at all, I suppose?" I said, when he had finished. "What you ask is a trifle stiff for such a simple service."

"Not a guelder," he answered briefly.

"Provided we agree, when can we sail?"

"To-morrow morning at daylight, if you like. There will be no difficulty about that."

"And you guarantee that the men you send with her can be trusted?"

"Nobody in this world is to be trusted," he answered grimly. "I've never yet met the man who could not be bought at a price. And what's more if I did meet him I would be the last to trust him. What I will say is that the men who work the boat are as nearly trustworthy as I can get them. That's all."

"All right. That will do. I will go back to my principal now and let him know what you say. If I don't return here within an hour you can reckon we agree to your terms, and you can go ahead."

"No, thank you, Mynheer," said Maalthaas; "that won't do at all. If I receive the money within an hour, I shall take it that you agree, not otherwise. Half the money down and the remainder to be paid to the captain when you reach your destination. If you want him to wait for you and bring you back, you must pay half the return fare when you get aboard, and the balance when you return here. Do you understand?"

"Perfectly. I will let you have an answer within an hour."

Fifteen hours later the money had been paid, the cablegram to Thursday Island despatched, and we were standing on the deck of the Dutch steamer König Ludwig, making our way along the Java coast at the rate of a good fifteen knots an hour.

"If Master Peach doesn't take care we shall be in a position to throw him a towline by this time on Saturday morning," I said to Mr. Leversidge, who was standing beside me.

"I devoutly hope so," he answered. "At any rate, you may be sure we'll make a good race of it. What shall we call the stakes?"

"The Race for a Dead Man's Pearls," said I. "How would that do?"

TO my surprise before we had been twenty-four hours at sea every one on board the König Ludwig seemed to have imbibed a measure of our eagerness, and to be aware that we were not in reality engaged in a pleasure trip, as had been given out, but in a race against a schooner which had sailed from the same port nearly forty-eight hours before. As a matter of fact it was Mr. Leversidge who was responsible for thus letting the cat out of the bag. Imperative as it was that the strictest reticence should be observed regarding our errand, his excitement was so great that he could not help confiding his hopes and fears, under the pledge of secrecy, of course, to half the ship's company. Fortunately, however, he had the presence of mind not to reveal the object of our voyage, though I fear many of them must have suspected it.

It was on the seventh day after leaving Batavia that we reached that portion of the New Guinea coast where it had been arranged that the schooner, for which I had telegraphed to Thursday Island, should meet us. So far we had seen nothing of Peach's boat, and in our own hearts we felt justified in believing that we had beaten her. Now, if we could only change vessels, and get to the scene of action without loss of time, it looked as if we should stand an excellent chance of completing our business and getting away again before she could put in an appearance. After careful consideration we had agreed to allow the steamer to return without us to Java, and when we had done our work to continue our journey on board the schooner to Thursday Island. Here we would separate, Leversidge returning with his treasure to England via Brisbane and Sydney, and I making my way by the next China boat to Hong-Kong, where I intended to lay by for a while on the strength of the money I was to receive from him. But, as you will shortly see, we were bargaining without our hosts. Events were destined to turn out in a very different way from what we expected.

It was early morning—indeed, it still wanted an hour to sunrise —when the captain knocked at our respective cabins and informed us that we had reached the place to which it had been arranged in the contract he should carry us. We accordingly dressed with all possible speed, and having done so made our way on deck. When we reached it we found an unusually still morning, a heavy mist lying upon the face of the sea. The latter, as far as we could judge by the water alongside, was as smooth and pulseless as a millpond. Not a sound could be heard save the steady dripping of the moisture from the awning on the deck. Owing to the fog it was impossible to tell whether or not the schooner from Thursday Island had arrived at the rendezvous. She might have been near us, or she might be fifty miles away for all we could tell to the contrary.

Once we thought we heard the sound of a block creaking a short distance away to port, but though we hailed at least a dozen times, and blew our whistles for some minutes, we were not rewarded with an answer.

"This delay is really very annoying," said Mr. Leversidge testily, after we had tramped the deck together for upwards of an hour. "Every minute is of the utmost importance to us, for every hour we waste in inaction here is bringing the other schooner closer. As soon as this fog lifts we shall have to make up for lost time with a vengeance."

How we got through the remainder of that morning I have only a very confused recollection. For my own part I believe I put in most of it with a book lying on the chartroom locker. Mr. Leversidge, on the other hand, was scarcely still for a minute at a time, but spent most of the morning running from place to place about the vessel, peering over the side to see if the fog were lifting, and consulting his watch and groaning audibly every time he returned it to his pocket. I don't know that I ever remember seeing a man more impatient.

As soon as lunch was finished we returned to the deck, only to find the fog as thick as ever. The quiet that was over everything was most uncanny, and when one of us spoke his voice seemed to travel for miles. Still, however, we could hear nothing, much less see anything, of the schooner which was to have taken us on to our destination.

"If this fog doesn't lift soon I believe I shall go mad," said Leversidge at last, bringing his hand down as he spoke with a smack upon the bulwarks. "For all we know to the contrary it may be fine where the wreck is, and all the time we are lying here inactive that rascal Peach's schooner, the Nautch Girl, is coming along hand over fist to spoil our work for us. I never knew anything so aggravating in my life."

As if nature were regretting having given him so much anxiety, the words had scarcely left his mouth before there was a break in the fog away to port, and then with a quickness that seemed almost magical, seeing how thick it had been a moment before, the great curtain drew off the face of the deep, enabling us to see the low outline of the cape ten miles or so away to starboard, and, as if the better to please us, a small vessel heading towards us from the south-eastward. As soon as I brought the glass to bear upon her I knew her for the schooner I had cabled to Thursday Island about. An hour later she was hove-to within a cable's length of us, and we were moving our traps aboard as expeditiously as possible. Then sail was got on her once more, the König Ludwig whistled us a shrill farewell, and presently we were bowling across the blue seas toward our destination at as fine a rate of speed as any man could wish to see.

For the remainder of that day we sailed on, making such good running of it that at sunrise on the morning following we found ourselves at the place for which we had been travelling—namely, the scene of the wreck of the unfortunate steamship Monarch of Macedonia. We were all on deck when we reached it, and never shall I forget the look of astonishment that came into Leversidge's face when the skipper sang out some orders, hove her to, and joined us at the taffrail, saying abruptly as he did so, "Gentlemen, here we are; I reckon this is the place to which you told me to bring you."

"This the place!" he cried, as he looked round him at the smooth and smiling sea. "You surely don't mean to tell me that it was just here that the Monarch of Macedonia met her cruel fate? I cannot believe it."

"It's true, all the same," answered the skipper. "That's to say, as near as I can reckon it by observations. Just take a look at the chart and see for yourself."

So saying he spread the roll of paper he carried in his hand upon the deck, and we all knelt down to examine it. In order to prove his position the skipper ran a dirty thumb-nail along his course, and made a mark with it about the approximate spot where he had hove the schooner to.

"Do you mean to say that the unfortunate vessel lies beneath us now?" asked Mr. Leversidge, with a certain amount of awe in his voice.

"As near as I can reckon it she ought to be somewhere about here," returned the skipper, waving his hand casually around the neighbourhood. And then, taking a slip of paper from the pocket of his coat, he continued: "Here are the Admiralty Survey vessel's bearings of the rock upon which she struck, so we can't be very far out."

Following Mr. Leversidge's example we went to the port side and looked over.

"It seems a ghastly thing to think that down there lies that great vessel, the outcome of so much human thought and ingenuity, with the bodies of the men and women who perished in her still on board. I don't know that I envy you in your task of visiting her, Collon. By the way, what are the Government soundings?"

"Seventeen fathoms," answered the skipper.

"And you think she is lying some distance out from the rock on which she struck?"

"I do. The survivors say that as soon as she struck, the officer of the watch reversed his engines and pulled her off, but before he could get more than a cable's length astern she sank like a stone."

"I understand. And now, Mr. Collon, your part of the business commences. When do you propose to get to work? We must not delay any more than we can help, for the other schooner may be here at any moment."

"I shall commence getting my things together immediately," I answered, "and, if all goes well, the first thing to-morrow morning I shall make my descent. It would not be worth while doing so this afternoon."

Accordingly, as soon as our mid-day meal was finished, I had the pumps and diving gear brought on deck and spent the afternoon testing them and getting them ready for the work that lay before me on the morrow. By nightfall I was fully prepared to descend in search of the pearl.

"Let us hope that by this time to-morrow we shall be on our way to Thursday Island with our work completed," said Leversidge to me as we leant against the taffrail later in the evening. "I don't know that I altogether care about thinking that all those poor dead folk are lying only a hundred feet or so beneath our keel. As soon as we have got what we want out of her we'll lose no time in packing up and being off."

I was about to answer him, when something caused me to look across the sea to the westward. As I did so I gave a little cry of astonishment, for not more than five miles distant I could see the lights of a vessel coming towards us.

"Look!" I cried, "what boat can that be?"

Mr. Leversidge followed the direction of my hand. "If I'm not mistaken," the skipper said, "that is the Nautch Girl—Peach's schooner."

"Then there's trouble ahead. What on earth is to be done?"

"I have no notion. We cannot compel him to turn back, and if he finds us diving here he will be certain to suspect our motive and to give information against us."

We both turned and looked in the direction we had last seen the vessel, but to our amazement she was no longer there.

"What does it mean?" cried Leversidge. "What can have become of her?"

"I think I can tell you," said the skipper, "We're in for another fog."

"A fog again," replied the old gentleman. "If that is so we're done for."

"On the contrary," I said, "I think we're saved. Given a decent opportunity and I fancy I can see my way out of this scrape."

OF all the thousand and one strange phenomena of the mighty deep, to my thinking there is none more extraordinary than the fogs which so suddenly spring up in Eastern waters. At one moment the entire expanse of sea lies plain and open before the eye; then a tiny cloud makes its appearance, like a little flaw in the perfect blue, far down on the horizon. It comes closer, and as it does so, spreads itself out in curling wreaths of vapour. Finally, the mariner finds himself cut off from everything, standing alone in a little world of his own, so tiny that it is even impossible for him to see a boat's length before his face. At night the effect is even more strange, for then it is impossible to see anything at all.

On this particular occasion the fog came up quicker than I ever remember to have seen one do. We had hardly caught sight of the lights of the schooner, which we were convinced was none other than the Nautch Girl, than they disappeared again. But, as I had told Mr. Leversidge, that circumstance, instead of injuring us, was likely to prove our salvation. Had she come upon us in broad daylight while we were engaged upon our work on the wreck below, it would have been a case of diamond cut diamond, and the strongest would have won. Now, however, if she would only walk into the trap I was about to set for her, I felt confident in my own mind that we should come out of the scrape with flying colours.

"We must not attempt to conceal our position," I said, turning to the skipper, whom I could now barely see. "If I were you I should keep that bell of yours ringing, it will serve to let Peach know that there is somebody already on the spot, and it will help to prepare his mind for what is to come."

The skipper groped his way forward to give the necessary order, and presently the bell commenced to sound its note of warning. Thereupon we sat ourselves down on the skylight to await the arrival of the schooner with what composure we could command. Our patience, however, was destined to be sorely tried, for upwards of two hours elapsed before any sound reached us to inform us that she was in our neighbourhood. Then with an abruptness which was almost startling, a voice came to us across the silent sea.

"If I have to visit you niggers in that boat," the speaker was saying, "I'll give you as good a booting as ever you had in your lives. Bend your backs to it and pull or I'll be amongst you before you can look round and put some ginger into you."

There was no occasion to tell me whose voice it was. "That's Jimmy Peach," I said, turning to Mr. Leversidge, who was standing beside me at the bulwarks. "I know his pleasant way of talking to his crew. He's a sweet skipper is Jimmy, and the man he has with him, Yokohama Joe, is his equal in every respect."

"But how have they managed to get here?" asked the old gentleman. "Theirs is not a steam vessel, and besides being pitch dark in this fog there's not a breath of wind."

"They've got a boat out towing her," I answered. "If you listen for a moment you'll hear the creaking of the oars in the rowlocks. That's just what I reckoned they would do. Now I am going to give Master Jimmy one of the prettiest scares he has ever had in his life, and one that I think he will remember to his dying day. If he ever finds it out, and we meet ashore, I reckon things will hum a bit."

So saying, I funnelled my mouth with my hands and shouted in the direction whence the voice had proceeded a few minutes before. "Ship ahoy! Is that the Nautch Girl, of Cooktown?"

There was complete silence while a man could have counted a hundred. Then a voice hailed me in reply: "What vessel are you?"

I was prepared for this question. "Her Majesty's gunboat Panther, anchored above the wreck of the Monarch of Macedonia," I answered. "Are you the Nautch Girl?"

There was another long pause, then a different voice answered, "Nautch Girl be hanged! We're the bęche-de-mer schooner Caroline Smithers, of Cairns, from Macassar to Port Moresby."

Once more I funnelled my hands and answered them. "All right," I replied, "just heave to a minute and I'll send a boat to make certain. I'm looking for the Nautch Girl, and, as she left Batavia ten days or so ago, she's just about due here now."

Turning to Mr. Leversidge, who was standing beside me, I whispered, "If I'm not mistaken he'll clear out now as quickly as he knows how."

"But why should he do so?" he inquired. "As long as he doesn't interfere with the wreck he has a perfect right to be here."

"As you say, he has a perfect right," I answered; "but you may bet your bottom dollar he'll be off as soon as possible. There is what the lawyers call a combination of circumstances against him. In the first place, I happen to know that he has been wanted very badly for some considerable time by the skipper of the Panther for a little bit of business down in the Kingsmill Group. They have been trying to nab him everywhere, but so far he has been too smart for them. In addition, he is certain to think his mission to the wreck has been wired to Thursday Island, and between the two I fancy he will come to the conclusion that discretion is the better part of valour and will run for it. Hark! there he goes."

We both listened, and a moment later could plainly distinguish the regular "cheep-cheep" of the oars as they towed the schooner away from us.

"He has got out two boats now," I said, "and that shows he means to be off as fast as he can go. Somehow I don't think we shall be troubled by Master Peach again for a day or two. But won't he just be mad if he ever finds out how we've fooled him. The world won't be big enough to hold the pair of us. Now all we want is the fog to hold up till he's out of sight. I don't feel any wind."

I wetted my finger and held it up above my head, but could feel nothing. The night was as still as it was foggy. Seeing, therefore, that it was no use our waiting about in the hope of the weather improving, I bade them good night, and, having been congratulated on my ruse for getting rid of Peach, and the success which had attended it, went below to my berth.

Sure enough when we came on deck next morning the fog had disappeared, and with it the schooner Nautch Girl. A brisk breeze was blowing. Overhead the sky was sapphire blue, brilliant sunshine streamed upon our decks, while the sea around us was as green and transparent as an emerald. Little waves splashed alongside, and the schooner danced gaily at her anchor. After the fog of the previous night, it was like a new world, and when we had satisfied ourselves that our enemy was really out of sight it was a merry party that sat down to breakfast.

As soon as the meal was finished we returned to the deck. The same glorious morning continued, with the difference, however, that by this time the sea had moderated somewhat. The crew were already at work preparing the diving apparatus for my descent. After the anxiety of the Nautch Girl's arrival, the trick we had played upon her captain, and the excitement consequent upon it, it came upon me almost as a shock to see the main, or to be more exact, the only, object of my voyage brought so unmistakably and callously before me. I glanced over the side at the smiling sea, and as I did so thought of the visit I was about to pay to the unfortunate vessel which was lying so still and quiet beneath those treacherous waves. And for what? For a jewel that would ultimately decorate a mere earthly sovereign's person. It seemed like an act of the grossest sacrilege to disturb that domain of Death for such a vulgar purpose.

"I see you are commencing your preparations," said Mr. Leversidge, who had come on deck while I was giving my instructions to the man in charge of the diving gear. "Before you do so had we not better study the cabin plan of the vessel herself, in order that you may have a good idea as to where the berth you are about to visit is situated?"

"Perhaps it would be as well," I answered. "Where is the plan?"

"I have it in my portmanteau," replied the old gentleman, and a moment later, bidding me remain where I was, he dived below in search of the article in question. Presently he returned, bringing with him a sheet of paper, which, when he spread it out upon the deck, I recognised as one of those printed forms supplied by steamship companies to intending passengers at the time of booking.

"There," he said, as he smoothed it out and placed his finger on a tiny red cross, "that is the cabin our agent occupied. You enter by the companion on the promenade deck, and, having descended to the saloon, turn sharp to your left hand and pass down the port side till you reach the alleyway alongside the steward's pantry. Nineteen is the number, and our agent's berth was number one hundred and sixty-three, which, as you will observe from this plan, is the higher one on your left as you enter. The next cabin was that occupied by the Reverend Colway- Brown, who, as you are aware, was one of the persons who escaped. I think we may consider ourselves fortunate that he was a parson, otherwise we don't know what might have happened."

Taking up the plan he had brought and examining it carefully, I tried to impress it upon my memory as far as possible. "Now," I said, "I think I know my ground; so let us get to work. The sooner the business is finished and the pearl is in your keeping the better I shall be pleased."

"I shall have no objection to be done with it either, I can assure you," he answered. "It has been a most tiresome and unpleasant affair for everybody concerned."

I then strolled forward to the main hatch, beside which my dress had been placed. Everything was in readiness, and I thereupon commenced my toilet. To draw on the costume itself was the matter of only a few seconds. My feet were then placed in the great boots with their enormous leaden soles; the helmet, without the glass, was slipped over my head and rivetted to the collar plate around my neck, the leaden weights, each of twenty-eight pounds, were fastened to my chest and back, the life-line was tied round my waist, and the other end made fast to the bulwark beside which my tender would take his place during such time as I should remain below.

"Now give me the lamp and the axe," I said, as I fumbled my way to the gangway where the ladder had been placed, and took up my position upon it. "After that you can screw in the glass and begin to pump as soon as you like. It won't be very long now, Mr. Leversidge, before you know your fate."

"I wish you luck," he answered, and then my tender, who had been careful to dip the front glass in the water, screwed it in, and almost simultaneously the hands at the machine commenced to pump. I was in their world and yet standing in a world of my own, a sort of amphibious creature, half of land and half of sea.

According to custom, I gave a last glance round to see that all was working properly, and then with a final wave of my hand to those upon the deck began to descend the ladder into the green water, little dreaming of the terrible surprise that was awaiting me at the bottom of the ocean.

THE novice when making his first descent beneath the waves in a diving dress is apt to find himself confronted with numerous surprises. In the first place he discovers that the dress itself, which, when he stood upon the deck, had appeared such a cumbersome and altogether unwieldy affair, becomes as light as any feather as soon as he is below the surface. To his amazement he is able to move about with as much freedom as he was accustomed to do on land. And despite the fact that his supply of air is being transmitted to him through many yards of piping from a pump on the deck above, and in consequence smells a little of india-rubber, he is relieved to find, when he has overcome his first nervousness, that he can breathe as comfortably and easily as when seated in the cabin of the vessel he has so lately quitted.

As stated in the previous chapter, as soon as the glass had been screwed into the front of my helmet I waved a farewell to my friends on the schooner's deck and began to descend the ladder on my adventurous journey. Men may take from me what they please, but they can never destroy my reputation as a diver. And, indeed, the task I was about to attempt was one that any man might be proud of accomplishing successfully.

The bottom on which I had landed was of white sand, covered here and there with short weeds and lumps of coral, the latter being of every conceivable shape and colour. Looking up I could distinguish through the green water the hull of the schooner, and could trace her cable running down to the anchor, which had dropped fifty feet or so from the spot where I now stood. Before me the bottom ascended almost precipitously, and, remembering what I had been told, I gathered that on the top of this was the rock upon which the unfortunate vessel had come to grief. Having noted these things, I turned myself about until I could see the boat herself. It was a strange and forlorn picture she presented. Her masts had gone by the board, and as I made my way towards her I could plainly distinguish the gaping rent in her bows which had wrought her ruin.

Clambering over the mass of coral upon which she was lying, I walked round her examining her carefully, and, when I had done so, began to cast about me for a means of getting on board. This, however, proved a rather more difficult task than one would have at first imagined, for she had not heeled over as might have been supposed, but had settled down in her natural position in a sort of coral gully, and in consequence her sides were almost as steep as the walls of a house. However, I was not going to be beaten, so, taking my life-line in my hand, I signalled to my tender above, by a code I had previously arranged with him, to lower me the short iron ladder which had been brought in case its services should be required. Having obtained this I placed it against the vessel's side, but not before I had taken the precaution to attach one end of a line to it and the other to my waist, so that we should not part company and I be left without a means of getting out of the vessel again when once I was inside. Mounting by it, I clambered over the broken bulwarks and was soon at the entrance to the saloon companion ladder on the promenade deck. Already a terrible and significant change was to be noticed in her appearance: a thick green weed was growing on the once snow- white planks, and the brilliant brasses, which had been the pride and delight of her officers in bygone days, were now black and discoloured almost beyond recognition. Remembering what she had once been, the money she had cost, the grandeur of her launch and christening, and the pride with which she had once navigated the oceans of the world, it was enough to bring the tears into one's eyes now to see her lying so dead and helpless below the waves of which she had once been so bright an ornament. I thought of the men and women, the fathers and mothers, the handsome youths and pretty girls who had once walked those decks so confidently; of the friendships which had been begun upon them, and the farewells which had there been said, and then of that last dread scene at midnight when she had crashed into the unknown danger, and a few moments later had sunk down and down until she lay an inert and helpless mass upon the rocky bed where I now found her.

Feeling that, if I wished to get my work done expeditiously, I had better not waste my time looking about me, I attempted to open the door of the saloon companion ladder, but the wood had swollen, and, in spite of my efforts, defied me. However, a few blows from my axe smashed it in and enabled me to enter. Inside the hatch it was too dark for me to see very clearly, but with the assistance of my electric lamp this difficulty was soon overcome, and, holding the latter above my head, I continued my descent.

On the landing, half-way down, jammed into a corner, I encountered the first bodies, those of a man and woman. My movement through the water caused them to drop me a mocking curtsey as I passed, and I noticed that the man held the woman in his arms very tight, as though he were resolved that they should not be parted, even by King Death himself.

Reaching the bottom of the ladder, I passed into the saloon, not without a shudder, however, as I thought of the work that lay before me. God help the poor dead folk I saw there! They were scattered about everywhere in the most grotesque attitudes. Some were floating against the roof, and some were entangled in the cleated chairs. I have entered many wrecks in my time, and have seen many curious and terrible sights, but what I saw in this ill-fated vessel surpassed anything I have ever met with in my experience. Any attempt to give a true description of it would be impossible. I must get on with my story and leave that to your imagination.