RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

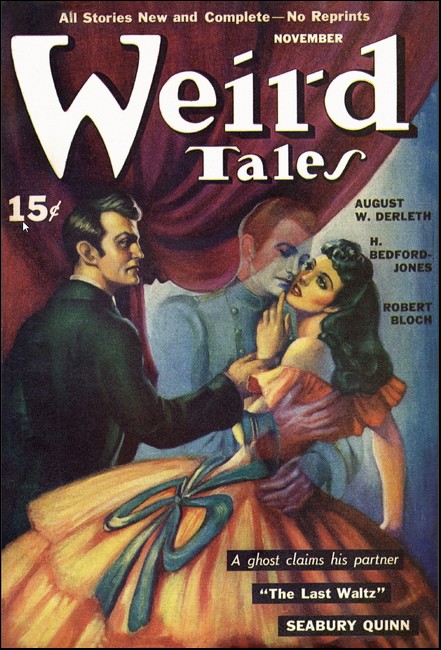

Weird Tales, November 1940, with "The Wife of the Humorous Gangster"

"Even while I was dancing, I could feel those

deadly eyes drilling into the back of my head."

THE ability to counterfeit death—

Yes, many's the handsome corpse I've made, but never under my real name. James F. Bronson is inscribed on no tombstone. Once I learned how to earn legitimate money, and big money, I went seriously to work at it. My physical abnormality, combined with the proper drugs, helped practice make perfect.

The element of chance, of adventure, of risk, so fascinated me that I would have traded professions with no one. And it is safe to say that no one would have traded professions with me. It is surprising how many people can make use of a dead man, however! This odd profession of mine had only one real drawback. I had to trust someone to bring me back to life after I was "dead."

For this little item, I very naturally needed a medico, and it was the curious adventure of the humorous gangster which provided me with a real find in this way. It was always a task to locate the right person. Although I was mixed up with nothing crooked, I could not employ any doctor imbued with high-faluting notions of professional ethics; such a man was too risky an equation.

Coming to a mid-western city I followed my usual procedure of inserting a blind advertisement in newspapers, and then scouting around for the right man to work with me. In this instance I found him in the person of one Dr. Roesche, a young fellow of German extraction.

Roesche had brains, he was conscientious, and he was hard up. I liked him from the start, because he refused point-blank to touch anything shady, and when he heard of my business he turned me down cold. He would only change his mind when I had convinced him that I was considering nothing of an illegal character, and wanted nothing from him that would conflict with professional ethics.

"I need you to administer a hypodermic; no more," I told him, and then frankly set my case before him, showing that my heart was on the right side instead of the left. "It has a very slow beat, too. More correctly, no beat at all. It flutters rather than beats, so there's no pulse to mention. They tell me it's nothing very rare."

"Atrial fibrillation," and he nodded. "And a barrel chest, I see. The heart isn't against the ribs—why, the stethoscope doesn't bring it up a bit!"

From a professional standpoint, he was keenly interested. Also, we got on well together. Once he consented to work with me, he was full of ideas. Instead of the chance drug I used to put me to sleep, he suggested an improvement on it. The upshot was that I got the idea of a permanent partnership, and he was not averse to it.

"You'll have to show me where there's any money in it, though," he said cautiously.

"Come on back to my hotel, then. Stop at the newspaper offices on the way, pick up the answers to my advertisement, and you'll see quick enough."

We did just this, and reached my hotel with a dozen replies to examine.

Half of them I weeded out as crank letters, others as involving something crooked. Then I picked up one and read it aloud:

"Dear Sir:

"Your advertisement may be a fake, but if not, I can use you. Believe it or not, my purpose is on the level and my money legitimate. If you want to talk business, give me a ring at this number.

"Yours for eternity,

"Dion Caffery."

When he heard the writer's name, Roesche uttered a grunt.

"You don't know of him? Then you'd better get acquainted with this town, Bronson. He runs a big flower shop on Seneca Avenue and lives in the apartment house overhead; in fact he owns it. His name used to be Cafferelli, but he changed it to Caffery."

I looked at him, puzzled. "Well? What's wrong with that?"

"Nothing, only he runs about half the rackets in the city, and he's in on the liquor game. In fact, the worst kind of a gangster."

This happened some years ago, during prohibition.

"Suppose we hear what he has to say?" I suggested. "The letter sounds interesting; even if the interview comes to nothing. I'd like to meet such a man."

Roesche assented with a shrug, and I called Caffery. To my surprise he had a very pleasant voice, and immediately agreed to drop in and see me.

I WAS more surprised when he showed up. He was heavily

built but well dressed, and had pleasant, intelligent

features with twinkling dark eyes. When I had introduced

my partner, he looked from one to the other of us,

whimsically.

"Just what kind of a gag is this?" he demanded. "Do I talk before witnesses?"

"You do if you want to talk," I said firmly. "If your proposition has anything crooked about it, then save it for somebody else. Dr. Roesche has to be in on the affair, as I can't work without him."

He broke into a hearty laugh, produced cigars, and dropped into a chair.

"You're all right, Bronson. Now, can you play dead enough so a doctor will pronounce you dead?"

"A good many have certified to it already."

"Just how is the trick worked? Loosen up with the details. They might not fit in with what I want."

I briefly indicated my abilities, and he nodded and leaned back in his chair, fully satisfied.

"Good. You'll do. What do you charge?"

"The fee depends entirely on the job," I said. "Frankly, I'm not sure I'd want to work for you, Caffery."

"And if you did, you'd make me pay big, eh?" He chuckled, displaying no resentment of my attitude. "Fair enough. I'll set the fee at ten thousand cash in advance. The work is to play a little joke on my wife and some of my friends. I want to pretend to kill you, and have some fun with the presence of a corpse."

I frowned at him. "Let's have straight talk, Caffery. In your business, which is no secret, why would you want an imitation corpse? I should think you could pick up a real one at a cheaper price."

He looked at me with a puzzled expression, and then smiled.

"Oh, I see! You have the conventional idea about what you call gangsters, eh? Well, Bronson, brush 'em all away. Give me credit for a little intelligence. I'm a pretty good business man, and I have average sense. I don't go around emptying a rod at anyone who looks cross-eyed at me; in fact, I've never killed anyone in my life. However, it's high time that I did, and that's where you come in. Forget your moving picture notions of bad men, will you? I'm not running a barrel house or a low den of iniquity. I'm running a business, and I'm at the top of it."

How much of his talk was blarney and how much was true, I'm not sure to this day, but it was impressive. His easy good humor, his intelligence, carried it over. I was inclined to believe his words, and felt ashamed of my own hazy notions about a gangster chief.

"Now, here's the proposition," he said, and sobered. In fact, he took on a look of worry; his eyes lost their humorous glimmer and became very earnest. "I'm too good-natured for my job, and that's no joke. My crowd is tough, sure. I've got to impress them. And chiefly, I've got to impress my wife. Nelly's a darling, but she just can't get out of the habit of flirting. Not that she means wrong by it, mind; just a habit. But it's got to stop."

I was startled.

"I don't like your idea," I said bluntly. "If you want to kill somebody, why should you, of all people, want to fake it?"

He made a helpless gesture. "D'you think I'm a fool? Murder is murder, Bronson. Can't you get it into your head that I'm no killer, that I don't want to spend my life in stir, that I've got enough brains to be something better than a gunman?"

Once more, contact with realities put to shame my vague conceptions of gangsters. This man was no crude, cold-hearted monster.

"Make your proposal, Caffery. I'll take it or leave it."

"Fair enough; here it is. Tomorrow night, I'm throwing a party at the Bon Ton Club. You come along there, wander in, and I'll greet you like an old friend. Play up to Nelly. She'll fall for you, strong; I'll say you're just in from New York, on a visit. I'll skip out with the boys, on business, and leave you to bring her home. When you get there, I'll be waiting. I'll rip into you for trying to play around with her and fire a blank, and you keel over. Her brother is a doctor and lives upstairs. If he finds you dead, I'll horse around and raise hell with everybody, and so forth. I'll have you carried into a back room. Dr. Roesch can be hidden there and fetch you around and sneak you out the back way, and everything's jake. The boys never will wise up to how I disposed of the body."

Joke? Maybe yes, and maybe not. He was too earnest about it.

I could see now that he had told the exact truth about himself. He was no killer, and his crowd probably knew it. He was clever enough to realize his shortcomings and conquer them by using his brains.

Behind this was the picture of a man trying to hold his wife—if she was his wife. As a matter of fact, she was nothing of the kind; I learned this, later on. But Caffery was dead in love with her all the same. He would have married her, except that she had a husband already and could not get rid of him. Caffery was simply crazy about her, but the people with whom they associated, the life they led, the way she acted, had him in torment on the anxious seat.

"Suppose the cartridge in your gun should turn out to have a bullet in it?" I suggested uneasily. He grunted.

"Oh, hell! Roesche can see to that himself. He'll be in the apartment at the time."

I looked at Roesche, questioningly. Ten thousand dollars was a lot of money. And there was nothing illegal about this. To my look, he shrugged and made answer.

"It's your funeral, Bronson; and literally, maybe. I think it's a risky business. But you're the one to decide. I'm willing to take it on if you are."

"Yes, you ought to be," I said unhappily. Then I looked at Caffery. "Two things about your scheme are bad. First, there'd be no bullet hole when my body was examined. That is, I hope there'd be none."

He chuckled, and his eyes twinkled again.

"The unpleasant possibility sticks in your craw, eh? But you're right. Besides, there's the noise. How's this, now! I'll use a big persuader, stuffed with cotton instead of lead. Give you one crack, and finish you, and proud of it. Suit you better?"

"Much better," I said with relief. "The second thing is that it wouldn't be logical to go off your head and kill a man, just because you let him bring your wife home. That is, a man you haven't seen for a long time, until that evening."

"Right," he agreed instantly, and plunged into the business with all the ardor of a small boy planning a parlor masquerade. He was amused and tickled by the whole thing. "I tell you, Bronson! Put off the party to Saturday night—see? On Friday night, I'll be at the Bon Ton for dinner, with Nelly and a couple of the boys. You drop in and meet us then, and play up a bit to Nelly—make it plenty strong. I'll invite you to the party the next night, which will be all jake. And on the way home I'll do enough talking about how you played up to Nelly, so things will look right when I blow you down. How's that? And is it yes or no?"

Under the circumstances, it could be nothing else than yes. Now that the blank cartridge business was out, the thing did not look so bad; in fact, I had already taken much riskier jobs than this.

So we buckled down to it then and there, settling all details and getting everything thoroughly understood, even to a floor plan of Caffery's apartment. And Caffery counted out five crisp thousand-dollar bills. The balance would be paid on Friday night.

"There's just one thing to guard against," I said in conclusion. "You mustn't let your doctor hold a mirror to my breath; that would give me away. Stop that at any cost, even if you have to call Roesche right in. That's one test I can't guard against."

"Right," said Caffery, and departed grinning.

The racketeer angle was not pleasant, but Roesche agreed with me that we now had the program foolproof. He had slightly changed the drug I used, so that any physical reflexes were more completely eliminated, and that same day he insisted on making a test with me. I submitted, and he was more than delighted by the results.

"It's marvelous, Bronson," he told me afterward. "With your eyes taken care of by the drops, and no mirror test, you'll get by with anything except a prolonged critical examination. Still, I'm uncertain about two things. First, the ultimate result on your health."

"Is that any worse than the ultimate result of a driving business life on any man?"

"Well, no," he agreed. "But what about the legal aspect of your stunt?"

I laughed at this, for I had long ago settled all such argument.

"Look it up; it's no crime, Roesche. That is, as I play the game. I might be arrested for attempting suicide, but I could beat out such a charge easily."

This was true. After he talked with a lawyer, his last doubt was settled.

WHEN I walked into the Bon Ton on Friday evening, I

was nervous enough. The place was a flashy one, the crowd

was large and well dressed, the orchestra banged heavily.

I heard a yell, and Caffery came rushing toward me. He

gripped me by both hands, hailed me lustily as "good old

Mike Leary," and dragged me to his table.

It was a big one in the center of the place. His wife and four other men sat there, and I was given a chair beside Nelly. I had little to do except follow the lead of Caffery, who asked no delicate questions, and was soon at my ease. That is, outwardly.

Nelly Caffery, as she was generally known, was a genuine blonde. She was vivacious, young, impudent and saucy, and ablaze with life. The homage of men was the very breath of existence to her, and it was no trouble at all to fall into my role of admiring male.

But those other four men—well, they were young too, young and sleek and gay enough. They made me think of something my uncle said after he got home from South America and was talking about his travels and adventures.

"A real bad man don't usually look bad, but if a man's living on a hair-trigger it always shows in one place. His eyes. They go into you."

That was the way with these young men. Their eyes drifted into me. Dark eyes, for they all had Italian names. Their eyes would question me, then shift to Nelly or to Caffery.

We danced, we drank, we laughed and joked and enjoyed ourselves. Had it not been for the deference paid Caffery on every side, the men who spoke to him, the curious glances cast at him, I could hardly have believed that I was sitting with racketeers. There was no rough talk of any kind. Even Nelly, except for her conspicuous diamonds, seemed no more than a carefree, light-hearted girl intent on pleasure; and so she was.

Caffery entered into his part with an impish glee. Under the spur of his delighted abandon, he showed himself a roaring boon companion; but there was iron in him just the same. He was no fool. When he urged me to go on and dance with Nelly, he gave her a hot shot under cover of a laugh.

"Look out for her, Mike! Remember that a woman never has any principles, or if she has any, she calls 'em something else."

This was over Nelly's head, however. She was not long on brains.

She was flattered by my obvious attention, by my swift interest in her, and tried hard to pump me about myself. She was one of those women who think themselves very deep, who have a "Why?" for everything as though in search of hidden motives, who set themselves to understand a man with their eyes and lips better than he understands himself; they are usually fools. Such vapid, doll-like beauties usually fancy themselves very subtle, and I suppose they find many a sap who falls for their pretty ways.

I could see that Caffery had Nelly sized up just right. She was not bad; she did not have enough sense to be bad. But flirtation was inborn within her. She simply could not help snuggling in my arms as we danced, and putting her face close to mine, and drinking in all my flattery until her eyes sparkled like stars.

So, from Caffery's viewpoint, the evening passed off most successfully, but the party broke up early.

"What are you doing tomorrow night, Mike?" exclaimed Caffery, before we left. "Come on and join us here about eight. We'll throw you a real party and run it into Sunday morning if you say the word!"

I hesitated and looked at Nelly. She begged me to accept, and I made it quite obvious that I accepted only because she wanted it. In fact, I was afraid I had overplayed my hand a bit.

But no. Caffery telephoned me half an hour later, and was positively chortling.

"Put it on thick tomorrow night, right from the start," he ordered. "I'll be called away early, then take the boys home. I'll be waiting when you get there."

"Don't wait too long, then," I said. "I have to put some stuff in my eyes, and it pretty near blinds me when it takes effect."

"I get you. Better wear a gun, for the looks of it."

"A gun? I haven't any."

"Then I'll slip you one at the table," and he rang off, chuckling.

I did not appreciate his humor at all. Even less did I appreciate it on Saturday morning, when Dr. Roesche walked in and got me out of bed to read a newspaper. He waved it at me.

"Open war threatens!" he declaimed, grandiloquently.

"War?" and I yawned. "Where?"

"Right here. Caffery and Rafello factions; gangster's war. Boy, I'm glad you got full pay in advance, last night! Here, read this."

It was not pleasant reading; I did not understand half of it, except that Caffery and some other racketeer had fallen out. However, it could not very well affect me, and I said so. Even if it did, I had taken Caffery's money and must go through with the play.

"Remember what he said about never having killed anybody?" said Roesche. "I bet he knew this was coming. He's pulling some rough stuff with you, to impress his own men; that was true enough. I'm glad tonight ends our connection with that outfit."

I was more than glad. I was delighted. The idea of lying dead to the world while warring gangsters pumped lead into me and made me an actual corpse, haunted me. Roesche was none too happy either as evening approached. Caffery had decided that upon leaving the Bon Ton with his friends, he would pick up Roesche and plant him in the back room, unknown to his henchmen. And poor Roesche, less accustomed to risks than I was, did not like the notion at all; still, he could not help himself.

At eight o'clock that evening I walked into the Bon Ton again and found the party assembled. Once more there was a big table, with Nelly the only woman at it. Caffery had six of his men here now, all of the same type, and he had done the thing up proud, with flowers galore and silver wine-buckets and all the trimmings.

I was the guest of honor, and he took a gleeful, chuckling pleasure in the irony of it. In the eyes of his companions, I fancied an ominous and sardonic suspense, as though they were watching and waiting; undoubtedly, Caffery had been talking about my attentions to his wife. He had not been talking to Nelly, however. She was bubbling over with high spirits, both kinds—the champagne flowed like water.

Even when I was dancing, I could feel those deadly eyes drilling into the back of my head; it took a real effort to play my part with Nelly, but I played it according to my instructions. And she did not make it a bit hard for me, either. Knowing that she would get a scare out of the whole thing, and nothing worse. I had small hesitation in making my admiration for her quite evident.

At the table, my seat was next to Caffery. Thus, under cover of the tablecloth, it was not difficult for him to slip a pistol into my lap. The touch of the thing startled me; I had for the moment forgotten our telephone conversation.

"Oh, it's not loaded," and he was evidently amused by my repugnance. He spoke under his breath. "Stick it away and pull it when I jump you. It'll look better."

"I hope you're getting your money's worth," I retorted. He laughed.

"I aim to get it, you bet!"

Getting the pistol into a hip pocket and cursing its weight, I led Nelly out on the floor again. She must have caught some warning from one of the other men, for now she gave me a sharp admonition, not unmixed with alarm.

"Watch your step, Mr. Leary! My husband doesn't like free and easy ways."

I smiled down into her eyes. "What's the harm, baby? I don't make you sore, do I?"

"You might, easy enough. Get wise; they're watching us."

"Let 'em watch," I said, and held her the more tightly. "You're a swell dancer; come on, forget your troubles!"

That was easy enough for her. When we came back to the table she was flushed and laughing, chattering away brightly; but under the watching, waiting eyes of those sleek men, I rather lost my confidence.

It was just nine o'clock, and the dinner was hardly well under way, when a waiter brought a note to Caffery. He read it, and then shot a muttered order at his men. Two of them rose and went out. Even though I knew he had arranged it all, I had to admire the manner in which he handled the affair.

"Sorry, folks," he said to us, with a shrug and a smile. "I've got to pull out. Business. Mike, you stick around and enjoy yourself, and bring Nelly home later on. I'll leave the car for you. Nelly, you see that Mike has a good time."

"No. I'll go with you," she said quickly. Caffery rose, laughing.

"Not much! I'm not going home. May not be back until late."

"Might as well have one more dance," I said to Nelly.

"Just one, then," she assented. "We'll finish dinner and go."

SO Caffery and his men said good-night, and Caffery

paid for the party as he went out. There was no longer any

point in my continuing with the act, so I did not try to

prolong matters at all. Nelly was nervous and uneasy, and

my lack of enthusiasm was not calculated to lift her sudden

depression.

"What's wrong with you, anyway?" I demanded, as we danced. "You seem to be out of humor with everything, all at once."

"I am. Just wrought up, I guess—" She broke off abruptly, staring over my shoulder. Her eyes dilated. Her face went white. "Let's get out of here, Mr. Leary. You don't mind, do you? I'm tired of dancing."

"Oh, it's all right with me," I replied, searching for the cause of her agitation and failing to find it.

We got off the crowded floor, came back to the table, and I persuaded her to take a swallow of wine before we left. She needed it, for some reason.

We delayed only a moment or two, but all of a sudden she straightened up and looked at a man who was approaching our table. Her eyes flickered, and then steadied, as she pulled herself together.

He was a short, heavy-set man in full evening dress. He was pale, with slick black hair, and there was an ugly twist to his lip. He paused at our table, gave me one swift and incurious glance, and then nodded amiably to Nelly.

"Hello," he said carelessly. "Where's Caffery?"

"I don't know," she replied. "He left a while ago."

"All right. Tell him I was looking for him, will you?"

With another careless nod, the man sauntered on. He joined two other men near the entrance, and they disappeared. Nelly was looking after him, and I saw that she was white once more, but her eyes were bright and eager and not in the least terrified.

"What's it all about?" I asked, as she rose. "Who was your friend?"

"My God, don't you read the papers?" she snapped at me. "That was Nick Rafello. I'll get my wraps and put in a phone call, and meet you at the door."

Rafello, eh? If he had come a few minutes earlier—well, I had missed something, and was heartily glad of it. A burning anxiety gripped me to finish this business and get rid of the whole mess.

And yet, even as I went to the men's room and made my own preparations, I thrilled to a glimmer of realization, of sharp suspicion. When Caffery left, the woman had been disconcerted and dismayed. When Rafello had shown up, she was agitated and alarmed; then, the look she had exchanged with Rafello—

How had Rafello known that Dion Caffery was going to be here? Had Nelly tipped him off?

Well, it was none of my business. In another hour I would be done with the whole racketeer crowd, and forever. Yet I could not forget the look those two had exchanged; eyes can speak more than tongues, at times. A look of understanding, of inquiry, of tacit comprehension. Anything further had been prevented by my presence at the table.

Was I really on the edge of underworld drama? Or was the whole business a product of my fevered imagination? Hardly likely, I thought; I could read faces. However, I had to get to work before rejoining Nelly.

It was a scant ten minutes ride from here to the Seneca Avenue apartment of Caffery, which was just the time margin I needed. In the privacy of the men's room, I measured out my dose of the drug mixture which would make me dead to the world, and swallowed it. Then, a much slower matter, I put the drops of homatropine and cocaine into my eyes—the drops which would deaden the cornea to any reflex test, and enlarge the pupils to simulate the look of death.

When I rejoined Nelly at the entrance, she was impatient.

"You certainly took your time," she snapped. "Look here, Mr. Leary. The car's outside and I don't need any escort—"

"Nonsense!" I exclaimed jovially. "Your husband told me to escort you home, and I mean to do it. Besides, it's only plain courtesy, Nelly. Come along."

We got into her limousine and were driven away, and a few minutes later halted before the apartment house.

As we went inside, I noted that the flower shop on the street level was open and was doing a good business; it was a Saturday night, so this was to be expected. Inside, Nelly tried to dismiss me again, but I insisted on going up to the apartment with her. As I was no longer paying her any devoted attention, she assented with a shrug.

We left the elevator and came to her apartment door. She inserted a key, threw open the door, and turned to me. The passage showed empty, and I wondered if Caffery were really here.

"Good-night, Mr. Leary," she said. "It's been—"

"Oh, let me come in for a minute anyhow," I exclaimed. "I'd like to put in a phone call, if you don't mind."

She hesitated. Just then a soft, hard laugh reached us, and she swung around. Caffery appeared in the passage.

"Yeah, come on in," he said. I was startled to see that his look of good humor had vanished; he was acting his part, I thought. "Come on, come on, and shut the door! I want to see you—the both of you."

There was an ugly note in his voice. I shoved Nelly inside, followed her, and pulled the door shut. Then, behind Caffery, appeared several of his henchmen, watching us. He drew back and ordered us into the parlor. I obeyed.

"What's the big idea, Caffery?" I demanded belligerently. His attention was fastened on Nelly rather than on me, and there was a blaze in his eyes.

"Oh, you!" He swung on me with a laugh—a harsh, grating laugh. If he was pretending, he was doing it ominously well. By this time, the drug was taking pretty full effect on me, while the stuff in my eyes left me nearly blind.

"I'll learn you to play around with my wife," he said viciously. "I'll learn her a few things, too, but you first. Why, damn you, d'ye think I'm blind and dumb? You blasted cheating bastard—"

I fumbled for the gun, could see nothing clearly, realized he was coming at me. Then something hit me over the head—something soft enough, but with a resounding thwack. I let the gun fall, and as I collapsed and lay quiet, heard Nelly scream. Then, before the drug blurred my brain, I heard something else.

"You!" It was Caffery's voice, hoarse now and filled with madness. "I've been too damned good to you, Nelly; you just took me for a sucker, eh? Well, I've got you dead to rights. Thought you'd bring Rafello in on me tonight and walk off with him after I was dead, eh? Shut up, damn you! I've got the proof of it—"

She screamed again, uttering wild protest. Caffery's voice reached me faintly. I could not stir; my brain was dulling out.

"There's your own letter to him, blast you! The woman I loved—why, good God! I'd have gone to hell for you, Nelly! And maybe I will, right now. Anyhow, you won't play and jockey with the love of any other man—"

There was the roaring explosion of a pistol above me, and everything was gone. I was out, and completely out.

LATER, Roesche told me what happened there in the front

room. Caffery stood as though paralyzed, staring down at

the woman he had just shot; the front of her evening gown

was blackened by powder. Then his men stirred and broke

into action. One of them knelt beside me. They conferred

briefly, Caffery standing the while and staring down like a

wooden image.

"Hey, Dion!" one of them exclaimed, and shook him by the shoulder. "Come out of it. What'll we do about this Leary guy? You biffed him too hard; he's croaked. Don't matter about Nelly. We can all swear that it was suicide. Here, give me the gun—"

He took the pistol from Caffery's hand, wiped it with his handkerchief, and then stooped. He pressed the dead fingers of the woman about it, and rose.

"Come on, Dion! Wake up! What about this guy?"

Caffery came out of his stupor. His face, aged and drawn and contorted, bore a stamp of horror. Then, meeting the intent gaze of the men around, he pulled himself together.

"Him? Leary?" A harsh cackle of mirthless laughter came from him. "Oh, to hell with him! Leave him to me; I'll handle the matter later. Carry him into the back bedroom, two of you, and shut the door."

"But Dion—"

"Do what I say, damn you!" he burst out, and they hastily obeyed. I was lifted and taken into the back room, where Roesche was hidden. And the minute we were alone together, he lost no time in fetching me back to life; not a quick job, unfortunately.

When two of his men would have touched Nelly's body, Caffery forbade them. Of course, his whole plan in regard to me was completely gone. There was no need of bringing in any doctor, or of bothering further with me.

"Somebody get out there," said Caffery, as a knock came at the door. "Some damned fools will be raising hell about the shot. Tell 'em it was an accident—anything at all. Tony! You go up and fetch Nelly's brother down here."

"Her brother?"

"Yeah," and Caffery's voice was grim. "He can certify to her death. She is dead, isn't she?"

"Yeah."

Caffery slumped, and he turned away. "All right," he said. "Go on and do what I say. I'll be back in no time. Keep her brother here, and keep him scared."

"Where you going?" one of the men asked.

Caffery looked down at the still, dead figure of the girl. "I'm going downstairs to get some flowers," he said gently, and his face changed and softened. "Roses. White roses. She always liked 'em best. Poor kid! She just got carried away; too much glitter. Yes, I'll get enough white roses to cover her out of sight."

He looked up, met the eyes of his men, and his voice barked out at them.

"Get busy. Round up everybody. As quick as I've attended to those roses, we go to work, understand? Tonight; here and now. Yes, Rafello's got a glitter to him, damn him! There won't be any glitter when I'm done with him. Get busy."

He went on out of the apartment.

Meanwhile, Roesche had been working like a madman over me. He gave me a dangerously strong injection, for he knew what had happened out front, and was scared stiff; however, he kept his head.

Caffery had shown him the way out. As soon as he had me half awake, he got me on my feet and rushed me out. I was dazed and groggy, of course; the descent of those back stairs of the apartment house was a nightmare. Roesche, with his arm around me, carried me part of the way, but the night air soon cleared my brain.

Then matters came easier. Once out of that accursed place, the feeling of relief was overwhelming. We went on down, and now the alley was before us, with only another short flight of steps to cover.

At this moment, a sound like a shot came from the street. Roesche laughed shakily.

"Backfire, eh? Gave me a start, though—"

Half a dozen more sounded, almost in a bunch.

"Backfire, hell!" I exclaimed. "That's shooting. Let's get away from here."

I was able to walk fairly well now. We drifted down the alley, came out on a street, and in another five minutes were in a taxi and on the way to the hotel.

"Well, we're out of it," and Roesche drew a long breath.

"Was it a dream?" I demanded. "Did he shoot her, or did I imagine it?"

"You imagined nothing," Roesche said grimly, and told me what had happened.

"Good lord!" I exclaimed. "Let's pack and clear out by the first train—anywhere." And we did it.

MORNING found us reaching a city three hundred miles

distant. We were breakfasting in the diner, before leaving

the train, when the morning papers were brought aboard.

Roesche got hold of one, glanced at the headlines, and

then, without a word, laid it in front of me. We read it

together.

As we descended those back stairs, the previous night, Caffery had been killed. We had heard the shots. He had been shot down as he stood in his flower shop, shot down by "parties unknown."

At the moment, he had been ordering white roses.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.