RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage Arizona travel poster (ca. 1920)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage Arizona travel poster (ca. 1920)

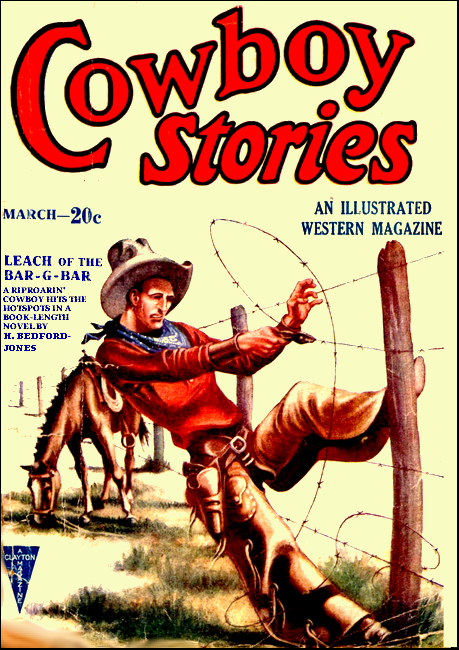

Cowboy Stories, March 1960, with "Leach of the Bar G Bar"

Joe Leach waltzed into Sunrise County and took charge of the Bar G Bar in the interest of its legal owner. But Aunt Hennie Billings, the sharp- tongued old maid who also claimed the ranch and was its actual possessor, thought the "young feller" was working for her. Joe felt right mean about the way he was fooling Aunt Hennie, but felt plumb ornery in that set-to with the gang which was rustling Bar G Bar stock. And because he had aimed only to see justice carried out, things squared up even all around in a way that came as a complete surprise to him.

SOME two miles outside Las Vegas, a young man lolled in the saddle and rolled a smoke, and whistled thoughtfully as he eyed the Sangre de Cristo peaks off to the west. His saddle was highly uncomfortable, having been rented with the horse at a Las Vegas stable early that morning. The stretch of level road where he waited was a lonely one.

Purring out of town was the big automobile of Tom Crocker, whose Lazy C brand was known all over New Mexico. Tom Crocker himself was known even farther. He was a small, spry, spare man approaching fifty, gray under his Stetson, with a wrinkled and sun-tanned face studded with twinkling gray eyes. Beside him sat another cattle magnate, Moran. A rousing poker session had just broken up in town.

"Then you'll not do anything with that Indian Valley place?" asked Moran, as Crocker made himself comfortable for the forty-mile drive home.

"Nope," said Crocker. "I'm getting old, Bill, and sort of hanker after peace. I can afford to let that there outfit alone, I reckon. Williams was the wrong man anyhow. I got enough worldly goods without going up against a posse of wildcats in the hills to grab more. The thing belongs to me now, but I'll let her lay."

"Ain't like you," commented Bill Moran.

"Neither is the rheumatism," and Crocker grimaced. "I got to go up to the Springs and boil out. Besides, I'm sort of taking care of myself in my old age, with that girl of mine to look out for. She sure was hell-set on not going East to school last week. I had a regular fight on my hands."

"How-come? She liked it all right last year."

"Yep, but she had a notion of running an outfit of her own. Naturally, I wouldn't hear to that." Crocker chuckled. "I packed up her duds unbeknownst to her, took her for a drive, landed her at the depot, and chucked her aboard the eastbound limited with a thousand cash in her handbag—just like that. She like to threw a fit over it, but she went."

Moran grinned, and shifted the cigar in his mouth.

"If I know her," he said, "she's liable to drop off that train and come back, or worse. She's got all your stubborn fighting foolishness, Tom. I'd hate to stack up against that girl when her dander's up!"

"Huh! So would I," admitted the fond parent. "That's why I got her off that-a-way. She's got her head full of old-timers' yarns about fighting and so forth. She heard about the lawsuit and me getting Indian Valley adjudged to me, and she was plumb set on going there and fighting it out. Doggone it, she's got spirit! But I aim to have peace."

"Get her married off."

"Huh! She'll do her own picking, don't worry—hell's bells! What's this?"

The brakes screamed. "This" proved to be a young man sitting his horse in the center of the road, horse and man apparently sound asleep. Crocker shouted angrily, and brought his car to a halt. The indolent rider woke up, straightened himself, and brought into view a large pistol covering the two in the car.

"Put 'em up and climb out," he ordered, and grinned. "Don't try to run over me—the trigger's quicker'n the engine. If you want to prove it, go ahead."

Both men took the holdup in silence, knowing they had too much cash about their persons to resist and trying to think of some circumventing method. Crocker sniffed in disgust and got out of the car, while Moran followed suit on the other side.

"Circle front and join," ordered the bandit cheerfully.

They did so, keeping their arms well up. The holdup man dismounted, with befitting caution, and threw his horse's reins over its head. He was a long-jawed young man, with a most infectious smile and twinkle in his eyes; those eyes were dark blue, and were wrinkled at the corners, while his shoved-back hat showed crisp light hair, bleached by sun and wind. Not a desperate character by any means—and not one to take any chances with.

"I'm not right used to these automatic pistols," he observed, "but the safety catch is off and I reckon she'll shoot easy enough. Now let's see what you got."

He shoved the pistol against the body of Crocker, and removed from the latter's coat pocket an old-fashioned forty-five revolver. Then he turned his attention to Bill Moran, who proved unarmed.

"I reckon you gents might sit down on that bumper without bending it," he said, and examined Crocker's weapon. Then he held out his own to the astonished cattleman. "Here you are, for a souvenir."

Crocker took the weapon from the grinning bandit, and examined it.

"Durn your eyes!" he said. "Unloaded!"

"Sure," said the other. "Yours is loaded, though."

And he carelessly drew back the hammer of the revolver. Moran chuckled.

"That's a good one on you, Tom Crocker! A good one. How much will you take to let us go, feller?"

"I ain't a feller," said the bandit in his cheerful fashion. "My name's Joe Leach."

"And you're a hell of a bandit," said Crocker promptly. "Holding up two gents without even a mask, and then telling your name! Huh I How much you Want?"

"Ten minutes," said Leach. The two men sitting on the bumper stared at him.

"Ten—what?" exclaimed Moran, puzzled.

"Minutes." Leach assumed an air of patience, "I see I got to speak in words of one syllabic. Well, I was trying yesterday to see a hombre named Tom Crocker, and he was too durned busy with a poker session. I wanted to see him last night—nothing doing. I done heard that when the session was over he'd blow out home in his car, and then maybe would be a hundred miles away when I got there. So I aimed to see him here and now, and I done it."

Moran opened his mouth and gaped. Crocker's eyes bit out like steel.

"Mean to say this holdup was a joke?"

"Not by a durned sight," said Leach earnestly. "It ain't a joke, believe me! I aimed to get your personal attention, and I need it bad."

"Well, you sure got it," said Crocker, his lips twitching. "What you want of me?"

"A job."

Crocker swallowed hard. Moran broke into a rumbling chuckle that became a full-bellied laugh.

"Hurray!" he chortled. "This is pretty rich. Held up for a job! I'll give you a job. Leach—you bet! I can use you."

"I'm talkin' to Tom Crocker right now, thanks," said Leach, and put up the gun in his hand to roll a smoke. "I'm sort of interested in working for you, Crocker."

"How come?" snapped the cattle magnate.

"I've heard you ain't got no use for any but a top-hand— I'm that. I've heard you can dispose of big jobs, more than just herding or even running a ranch. That's the kind I want. I've heard you're hard as nails, back up a man to the limit if he makes good, kick him out if he doesn't, and are just. You suit me right down to the ground, Crocker. How about it?"

Tom Crocker laughed, and it was hard o say whether this laugh held more anger or amusement.

"Want to run a ranch for me, do you?"

"No," said Leach. "I want a man's job, if you've got one."

"Huh!" Crocker surveyed him up and down, and reached for a plug of tobacco. He bit at it jerkily. "Huh! Think you can run a blazer on me like this, do you—think I'll fall for it? You don't know me, feller. What do you know about my business?"

"Everything except local conditions," said Leach promptly. "And—"

"Know how to use a gun?"

"No. I can't hit a barn at fifty feet."

Moran chuckled at this. Crocker grunted again.

"Know everything about my business, do you? Prove up, hombre! You don't look like any cattleman to me. Where you from?"

"Born in the short-grass country. My folks moved to Montana. I been all kinds of things on a ranch. Been back East for a year tackling business, and failed at it. I'm broke."

"Huh! When you're broke, you ain't particular how you land a job."

"Naturally not," admitted Leach. "But I'm particular about what job I land."

Crocker turned and looked at Moran. "Ain't he a bird. Bill—ain't he, now? Me, I think he's plumb crazy."

"Me too," said Moran. The cheerful Mr. Leach grinned amiably.

"I'm tempted to agree with you gents at times. Do I drift back to town without a job or with one?"

"I'll give you a job, if you'll take it," said Crocker, with grim intonation.

"I'll take it," said Leach.

"You'll wish to thunder you hadn't!" growled Bill Moran, grinning to himself.

"Huh! I reckon you will," added Crocker.

"Probably so," said Leach. "Name the card."

"Ever hear of Indian Valley? No? Well, it's quite a ways from here in the wrong direction and you can get there quicker with an automobile than on a train," said Crocker. "Got any money?"

"Nine dollars and thirty cents."

Crocker reached into his pocket and produced a roll of bills, stripping off ten.

"Here's a hundred. I got an old flivver laying in the Stone Garage, in town, and you go get it—you can have it. Go to Indian Valley, over in Sunrise County. At Sunrise City, you'll find an agent of mine, if he ain't dead or lynched or run out. He's quit on the job. His name is Williams, Ernie Williams. He'll tell you what the job is, and durned glad to do it so's he can quit. Want it?"

"It's my job," said Leach. "What's in it if I win?"

"Five thousand bonus and five thousand a year running things there for me."

"You're on." Leach held out the revolver. "You might want this if you meet a real holdup, and I might want my pistol—that's right. Thanks. An empty gun is a whole lot more good to me than a full one. Keeps me out of jail."

"Huh!" said Crocker, standing up. "If I was you, I wouldn't go around using my name. It ain't healthy over in that section."

"Oh!" said Leach thoughtfully. "So that's it, huh? Suits me fine. Much obliged. I'll report when the job's finished."

"If it ain't finished, don't report," said Crocker, climbing into the car. "So long!"

THE big car went rolling away. Leach stared after it

thoughtfully, then a grin came into his face.

"Huh!" he exclaimed in mimicry of his employer's grunt. "Huh! If you knew that Sally Crocker had put me up to this way of introducing myself, and that she and I aimed to get married, you'd of said 'So long!' in a different tone of voice, I reckon. If I hadn't met her back East last year, I'd still be there. Well—get along, you mangy cayuse!"

And Mr. Leach rode back to town, whistling cheerfully.

SOME days thereafter, Joe Leach came thumping into Sunrise City in a wheezy, battered old bunch of junk that had once been a good car. It was still a car—that was all.

He knew nothing more of his job than when he had taken it, but he had learned a little about Indian Valley. It was a small, rich valley up in the hills, off from everywhere, settled two generations back by a wagon-train of Missourians, and their descendants were known as hard customers, with accent on the hard.

Until the past few years they had run Indian Valley to suit themselves, keeping all strangers out, inter-marrying and in general ruling everything from courts to jobs.

After the war all barriers were down and outsiders got in, but not all of them stayed. It was a tough country on foreigners, as those from the outside world were locally-termed.

Leach faced the prospect cheerfully. He rolled over a steep divide, came down a twelve-mile, winding, twisting grade, and pounded along the valley floor on three cylinders for several miles, until he came into the one and only town of Sunrise City. All around loomed mountain peaks, while the main valley and its branches were a rich and fertile green, watered by a. perpetual seepage. Beside the town was a good-sized stream of water. The farms were prosperous, the outlying ranches thick with fat cattle; most of the ranching part of the valley lay in the upper end beyond town, and in the branch valleys.

Rattling over a bridge, Leach drew up before a garage. Automobiles were few here, as the old-fashioned pump testified. Leach opened up his tank and watched as the gas was pumped in one gallon at a time, called the halt, and screwed down the cap. Then he smiled at the dour-faced proprietor as he reached for his money.

"Great place, this! Know a gent here by the name of Williams? Ernie Williams?"

"Heard of him," said the other, with an appraising, unfriendly look. "Friend, huh?"

"Friend?" said Leach, and his smile vanished. "Listen here \ That hombre done me out of fifty dollars, see? I've run him down to here. I aim to collect, or bust his face. If you know him, where is he?"

The garage man grinned and loosened up, as he made change.

"Reckon you'll find him up to the hotel, stranger. He's been fixing to leave town, but I ain't seen him go out this morning. Done you out of money, huh?"

"He sure did—him and the man he works for," said Mr. Leach. "If there's two low-down coyotes on the face of the earth, it's them!"

"Well, I dunno you're far wrong there." said the other. "Hotel's along up the street on the right. Reckon you won't find Williams there till noon, though."

"If he's there then, that's all I ask," said Leach. "Much obliged, partner!"

He drove off up the street as directed.

SUNRISE CITY was a rambling place, sprawling beside the river

and over two low hills, with no crowding. The one business street

was several blocks long. Hitch-racks lined the walk, and the dust

was considerably allayed by gentlemen whose chief occupations lay

in sunning themselves and masticating tobacco. The courthouse was

a large building of brick and adobe, and its wide square was

shaded by stately trees. Beyond it lay the hotel.

As he slowly drove along, Leach was aware of eyes following him; he was being critically appraised. The garage man, he knew, would lose no time in spreading abroad that this "foreigner" was looking for Williams—all well and good.

Before the shabby frame hotel Leach halted his flivver, alighted, and stretched himself. No one was in sight on the hotel verandah, the chairs were unoccupied. He strode in, and found a one-eyed gentleman behind a counter.

"Howdy," he greeted genially. "I'm looking for a feller by the name of Williams, and I heard he's stopping here. Where can I find him?"

The one eye appraised him critically.

"Take a chair on the porch and he'll be along for dinner, I reckon. From down below?"

"Uh-huh. And going higher up. Reckon I'll eat dinner instead of Williams—he won't cat much when I get done with him."

"Oh!" said One-Eye, with interest.

"So friendly I'll put him in the hospital if he don't give up what he stole off me!" said Leach.

With this to amuse the gentleman, Leach went back to the porch. He picked out an unbroken chair, adjusted it to suit himself, leaned back comfortably, reposed his feet on the rail, and settled down to wait, with the help of a cigarette.

"I'll bet this town will sure be hanging on what happens here when Williams gets back!" he reflected, and chuckled softly. "Well, I reckon they'll get a show for their money—holy poker! Holy horntoads! Is it real?"

Suddenly, Mr. Leach took his heels from the rail, lowered his chair, shoved back his hat, and stared—hard. Coming across the street toward the hotel, with packages in both hands, was a girl; more correctly, was Sally Crocker. He had thought her several thousand miles away, and for a moment was stunned by sight of her. She wore khaki and leggings, and beneath her Stetson was a smiling, merry face whose dark blue eyes held all the energy of her father.

She mounted the steps to the verandah before seeing the staring Joe Leach. Then, catching sight of him, she halted and the packages escaped from her arms to fall unheeded.

"Joe! You—then you made it!"

Leach rose, swept the packages into a pile with one foot, and reached for her hand.

"Are you real?" he demanded, with such blinking incredibility that she burst into a laugh. "My gosh, Sally! And I was just figuring on writing you a letter—"

Next instant she was in his arms—only to escape with a swift wrench.

"Stop it, Joe! Don't you dare breathe my name—come and sit down. If you want to play post office, take a better time and place—"

Leach accompanied her to the chairs and dropped into one. He was all at sea, and looked it. Sally Crocker surveyed him with twinkling eyes.

"What's the matter? You seem struck by lightning."

"I am," said Leach. "What on earth you doing here? How come you don't love me any more?"

"I do, silly," exclaimed the girl. "But I don't want all Sunrise City to know it, do I? I'm supposed to be a lunger, here for my health, and I'm going out in the hills on that pretext—"

"You look it," said Leach gloomily, regarding her vigorous face and wide-shouldered figure. "Yes, you look like a lunger. Going—where? Alone?"

"Yes. My name's Sally Jones right now, and I'm from Kansas City."

"Does your dad know it?"

"Not much." Her eyes darkened. "Daddy put up a game on me—got me aboard the eastbound limited before I knew it, bound for school. So I hopped off the first stop and came here."

"Gosh!" said Leach in consternation. The girl laughed.

"Williams said the same thing, just the same way." A troubled look came to Leach's face.

"He'll tell your dad you're here, then there'll be hades to pay!"

"He won't tell," asserted the girl confidently. "Ernie Williams knows better."

"Hm!" said Leach, with an inquiring glance. "Got something on him?"

She nodded brightly. "Several things. By the way, did Dad tell you what the job here was—did he go into details?"

"Nope." Leach shook his head. "Said Williams would inform me. What are you grinning about? Is it so tough as all that?"

"Worse." Her amused look vanished, and her blue eyes rested on him seriously. "It's a bad mess, Joe. I didn't know it was so bad when we framed things up. I've learned more since then. I'm mighty sorry now that you've taken it on, but maybe we can pull it off together."

"Well, just what is it?" She rose.

"Williams can tell you that, but don't be seen talking with him. If these natives suspect you're on Dad's business, they'll act up. They're bad, too!" Leach grunted. "Where you going?"

"To work. In a couple of hours. I'm off. We'll meet soon enough—mustn't be seen talking any more together. So long!"

"So long, then—and next time we meet, you'd better be more friendly!"

"Wait and see," she flung back laughingly and was gone.

LEACH resumed his easy posture, and collected himself. He was

amazed, to put it mildly, by this meeting; yet he might have

expected something of the sort. Sally-Crocker never did what she

was supposed to do, was always loaded with dynamite, and life in

her company was never dull. However, this business was a bit too

strong.

In it was more than dynamite—the situation was full of T.N.T. and then some, thought Leach uneasily. When Crocker found his daughter was parading around these hills in khaki, he would raise Cain; and if anybody else discovered it first, trouble would ensue. For some reason the old cattleman was not loved in these parts.

Tiring of his unrewarded vigil, Leach ambled inside and engaged the one-eyed proprietor in conversation. The native was curious, very curious, and Leach satisfied his curiosity in a wide-eyed and innocent fashion, with a string of alleged facts which would have made Sally Crocker stare her hardest. Most people believed Joe Leach—he had an engaging, ingenuous air which marked him as a simple-hearted young man with no intent to deceive. He was not so harmless as he looked, however, having rubbed up against the world long enough to get the corners smoothed off.

His account of himself, therefore, was circumstantial and plausible, well calculated to banish any local suspicion. The proprietor wanned to his guest and took him to a room. Finding that this young puncher had come up from Utah, from a valley removed from the world and much like Indian Valley itself, and was seeking a homestead place, he volunteered a word or two of advice.

"Don't you be in no hurry to find you a place, Leach. They's lots of good land here, but you'd better get acquainted first and take up a quarter-section later on."

Leach nodded, fully comprehending the warning to let himself be sized up by the natives.

"Is any gun-toting barred here?" he asked. "I've chased this here Williams a long ways, and if he pulls on me I don't aim to let him shoot first."

"Go as far as you like," said the one-eyed gentleman, cordially. "There won't be no mourning if you shoot this here coyote, or the man he's working for, either! So long."

Leach grinned to himself. Cheerful prospects for anyone employed by Tom Crocker!

A LITTLE later, washed and fresh-shaved, with Sally in mind,

Joe Leach stood near the cigar counter in the dingy lobby and

smoked thoughtfully. He was not blind to the remarkable

assemblage of gentlemen who now thronged in and about the hotel;

one would have imagined a loafer's convention in progress, and

the spittoons were liberally patronized. Most of Sunrise City

seemed to be hanging around and waiting for something to

happen.

There was a stir outside. A car drove up and halted. From the car alighted a rangy man with a harsh hatchet-face—Leach knew this was Williams from the comments of those around. Williams looked at the crowd, narrow-eyed, as though expecting trouble, then made his way up the steps and to the desk.

"Got any mail for me?" he snapped to the proprietor.

"No," snapped the latter with equal acerbity.

Leach quietly drew his unloaded pistol and touched Williams on the arm. Williams whirled, to look into the weapon.

"Put 'em up," said Leach, loudly. "Up, durn you! I got you now, and I aim to settle up with you. You and that no-account Tom Crocker done me out of fifty dollars, and you're going to pay or suffer! Now turn around and lead the way to your room. No talk, you lowdown skunk! You let out one peep and I'll sure as hell perforate you. Lead the way!"

Without a word, Williams turned, his hands in the air, and started for his room.

LEACH turned with a triumphant wink to the crowd, but he saw at once that they were not a bit pleased. They had anticipated a rumpus, and felt cheated. Then he was following Ernie Williams up the stairs.

"Your name Leach?" demanded Williams, low-voiced, over his shoulder. "Uh-huh."

"The Old Man wrote me you'd show up—"

"Well, we got to stage a battle royal," said Leach promptly, relieved that the other had understood this amazing reception. "That bunch downstairs are trailing along. Get up to your room and wreck it—hustle!"

Williams quickened his pace. In a loud voice, he began to accuse Leach by name.

"Dog-gone you, needn't think you can get away with this robbery!" he rolled out thunderously. "I'll have the law on you for this—"

"Shut up!" bellowed Leach. "For two cents I'd put up this gun and do to you what I'd like to do to Crocker, the varmint. You and him are both skunks."

"And you're too durned brash," snapped Williams. They were in the upper corridor by this time. Glancing down the stairway, Leach saw that the crowd was indeed trailing.

"Let her go," he said softly.

Williams, in full sight of those below, struck at him. Leach grappled. The two men clinched, smashed against the banisters, rolled back against the door of Williams' room and smashed it in. They knocked over tables, chairs, charged back and forth, staged a spectacular battle, while about the doorway crowded the natives with whoops of delight. At length Williams went down, and a moment later Leach bestrode the recumbent figure and flourished his fists.

"I got him!" he panted to those at the entrance. "Shut the door, folks, and leave him to me—I'll do the rest."

"Lemme up!" bleated Williams. "I'll pay, durn you!"

Satisfied, the crowd ebbed. The door was slammed shut. The two men rose, grinning at each other, and replaced the overturned chairs.

"Better tie a bandage around your head when you go down to dinner," exclaimed Leach. "I reckon I'll need all the prestige I can scrape up before I get through."

"You sure will," said Williams grimly. He sat down and produced the makings. "Crocker said you were a wild one, and he was right. You know what this job is?"

"No."

"It ain't a job—it's an impossibility," said the other, grimly. On the wall hung a map of Sunrise County, containing Indian Valley and overlapping it in wild ranges of hills. To this Williams jerked his thumb.

"There y'are—you can have it. Put your eye on the Bar G Bar range, in the north end." Obeying Williams' mandate, Leach there saw a compact rectangle comprising two valleys that came together at a small lake. "That there property come on the market a while back," pursued Williams, "and Crocker done bought her in. That is, he done bought most of it in. The old settler who had owned that and a lot more property, had incorporated it to save paying inheritance taxes. After he died, most of it went to his heirs in Denver, so Crocker come to buy it. There was a little block of shares, about ten per cent, went to an old maid relative. She wouldn't sell, and she's on the place now. It was her fought Crocker in the courts."

Leach rolled a smoke and listened, without comment. A dark frown on his harsh features, Williams went on with his story.

"The orders to me were simple enough. The ranch is badly disorganized; I was to take hold and get her in shape. The old lady there has no money and has let the place go to rack and ruin. I was to put in a crew of men and build it up; I've got ten thousand in cash, for payroll money and other expenses. Crocker didn't want to run out the old dame—he says to give her the house for life—but gosh! She's hell on wheels, feller! She done took a shotgun to me first time I was there, and warned me off'n the place. The whole durned county is behind her and against anybody representing Crocker, and believe me, this here county don't hesitate to fire a gun or two! I'm getting out while I got a whole hide."

Leach could see that Williams might be a good man in his way, but was hardly the right man to handle any such negotiations.

"The funny part of it is," said Williams, with a hard laugh, "the old hag has neighbors—see 'em there on the map? The Bull's-Eye—dot in a circle. Two young devils run it—the Ball boys, usually called Red Ball and Black Ball. They're bad, feller! Especially the black one. They're rustling the Bar G Bar cattle right and left, so naturally it's to their interest to help keep Crocker out until they finish looting the place. They're the ones leading all the trouble."

"Been trouble, has there?" queried Leach.

"Nothing but," affirmed Williams gloomily. "If Tom Crocker'd let me do what I want, I guarantee I'd have this district gentled in no time! I'd like to run in a crowd of real punchers and give these devils of natives all the cussedness they want—but, no, sir. The Old Man won't hear to it. Do it gentle, he says—gentle! Age has weakened him, I guess."

"These here Ball boys are well located," observed Leach, eyeing the map. "I see the Bull's-Eye lies half around the Bar G Bar. What are those fellers like?"

"Bad," said Williams with emphasis. "Red ain't so ornery, but Black Ball—honest, that gent will be hung some of these days! He's got a hard crowd riding for him, too. I done had a run-in or two with 'em, and it's got to where bullets come next. Tom Crocker won't back up that play, so I'm quitting. Either he's got to change his tactics, or else wait for the old hag to die off. I s'pose you ain't going to fight 'em?"

"I got the same orders you had," and Leach grinned. "No, you're right in supposing I'm not the fool I look. I don't know what I will do, for a fact, except brace the old lady."

"She'll send you packing, quick enough, and telephone the Ball boys to mob you. Well, you want me to turn over the ten thousand cash, and my letter of authority, huh? I got the money on me—couldn't trust the bank here. All these natives work in together."

Thought Leach to himself, Tom Crocker! made one big mistake when he sent this type of man on such an errand. He said nothing, but signed a receipt for the money, which was in big bills, and pocketed it with the letter from Crocker.

"You've got a right good car out there," he said. "Is it yours or Crocker's?"

"His," said Williams.

"Then hand it over. You can take my flivver to go home in, with my compliments to Tom Crocker—she runs well enough, if you ain't particular. We'll make it look like I forced the car out of you on the settlement; meet me after dinner. When you leaving?"

"Soon's I eat."

"All right. My flivver's full of gas and oiled up for fifty miles or so. What's Crocker going to say when you tell him Sally's here?"

"Seen her, huh?" Williams gave him 3 sharp look. "I ain't going to tell him. I got some sense left."

"All right. You think she is safe here?"

"I reckon so—it's mighty safe for women here, if nobody learns their name."

"See you after dinner, then. Don't forget to tie up your head like you're hurt."

Leach departed.

DOWNSTAIRS, he had to run a gauntlet of queries before

reaching the dining room. He assured all and sundry he had

effected a satisfactory settlement with Crocker's agent, and

intimated that the gentleman was leaving town in a hurry with a

damaged anatomy. Then he went in to dinner. Sally Crocker was

alone at a table, and beyond a furtive grin. Leach left her

strictly alone.

Now that he knew the situation, he could see its difficulties—could see, too, why the harshly vigorous Williams had fallen down hard. He gained further insight from talking with the men at his table; their tongues had been loosened by word of what Leach was about, and they voiced the general opinion of the valley. Crocker's hired man was trying to turn a poor old woman out of her home, and the county would not stand for it. If Crocker sent another man to take the place of Williams, he'd probably meet hot lead or hot tar. Old Miss Billings had got to be left in peace, or Sunrise would know why!

PONDERING these things, Joe Leach sauntered across the street,

after dinner, and down to the first and only National Bank of

Sunrise. He found a sleepy cashier in charge, and shoved his wad

of bills across the counter.

"Deposit on checking account. Name, Joe Leach."

The cashier nearly had heart failure, to judge from his appearance.

"Hey! We got to have references—"

"So do I, which is why I have them," said Leach cheerfully, and gave two excellent if distant references. "I may settle down hereabouts, if the place likes me as much as I like it, savvy? Anyhow, the cash is safer with you than with me, partner, so I'll swap it for a check book."

While Leach was filling out his card and giving his signature, the local banker came in. He had been at the hotel, and shook hands impressively with his new depositor.

"Do you know where I might land a job?" said Leach. "I ain't particular about wages, but want to get acquainted in the valley. I know a lot about cows and such."

The banker grinned. "If you're not particular about wages, why not go and see Miss Billings, over at the Bar G Bar? Go tell her about you and Williams."

Leach looked astonished. "Huh! Tell her? Why in time would I tell her that?"

"Because Williams has been trying to turn her out of house and home. She ain't got much cash, but she's got a ranch that needs attention."

"And I got some money," said Leach thoughtfully. "Would you mind giving me a note to her? I don't much like the notion of asking for a job because I beat up a feller—"

"Sure, sure," agreed the banker heartily. As he owned a large share of the valley and was related to fully two-thirds of the intermarried inhabitants thereof, his signature would be highly valuable. "And if you want any advice from time to time, drop in and let me know. I'll be right glad to oblige, Leach!"

LEACH went back to the hotel, the letter in his pocket. He was

just in time to meet Williams, emerging with a grip, a bandage

about one ear, and a crowd of loafers hurling various remarks.

Leach hailed him.

"Hey! Gimme the bill of sale for that there car, and we'll let a couple of these gents witness it. Folks, Mr. Williams has swapped cars with me. He says he ain't got no use for a high-powered car; what he wants is a nice little tin lizzie. So I'm obliging him."

One glance from the excellent car of Williams to the rattletrap of Leach was enough to raise a guffaw. Williams turned red, but played his part despite anger. He wrote out a supposed bill of sale, Leach had it witnessed by two bystanders, then turned over the flivver to him with many flourishes. After some instruction, Williams meshed his gears and drove away.

With a grin at thought of what Crocker would say. Leach inspected his new car—a medium-priced, high-powered machine. The crowd helped him inspect it, and from their comments, Joe Leach knew he had gone a long way toward getting into the good graces of Indian Valley in general, and Sunrise City in particular.

While he was still looking over his car, he saw Sally Crocker come out of the hotel and cross the street, a grip in her hand. She climbed into a buck-board waiting there, being helped up by a man with whom she shared the seat. Next minute she was driven away, while Joe Leach blinked after her—stupefied. The worst of it was, he dared not even ask about her, or whither she had gone!

EARLY next morning Joe Leach was off and away in his new car, armed with Williams' map of the county and general optimism. He had only vague notions of any plan of campaign, preferring to let this hang on conditions and circumstances. The tremendously bitter antagonism which Williams had stirred up in the county seemed to make his task a hopeless one, but Leach faced ahead with cheerful faith in destiny and stepped on the gas. The Bar G Bar lay eleven miles from town, according to the map, but when Leach's speedometer showed thirteen, there was still no sign of the ranch. The road was rough, and wound in hilly, well-wooded ground. A saw-mill would do well in these parts, reflected Leach.

He came down into a glade, crossed a wooden bridge, turned sharply—and put on all his brakes in a hurry. Directly ahead of him, three horses were in the road, their riders talking and laughing over some joke. One glance showed Leach they were punchers—not dressed for the part, since their clothes were rough woodsgear—but one judges not so much by clothes as by equipment. And punching cattle in these hills probably included a lot of work in wooded country.

To the astonishment of Leach, the three men separated and whipped out pistols.

"Put 'em up!" yelled one, bringing his horse up to the car. Then a ludicrous expression of bewilderment swept over his face. "Look out, boys—don't shoot! He ain't our man!"

"Put 'em up!" yelled one.

"Thanks." Leach climbed out and reached for the makings. He surveyed the three with a grin, and caught answering amusement in the face of the one who was red-haired and blue-eyed. Another, also blue-eyed, was very black of hair, insolent and domineering of face, high-boned and obviously given to passion. In these two. Leach knew at once with whom he dealt. No other pair could be just like them, even had not the horse-brands shown him.

"I ain't anybody's man, for that matter," he added whimsically. "Maybe I will be, a little later, if I have any luck getting a job. I see you boys are from the Bull's-Eye. Maybe you can direct me to the Bar G Bar? According to the map, it ain't far from your outfit."

The black-visaged one inspected Leach scowlingly, narrow-eyed.

"I ain't a sheriff, if that's what you're scared of," and Leach chuckled. "I won't tell. If you boys are working holdups right along, it's all right with me—"

"I'm Hank Ball, this is my brother Red, and Perkins, a rider," snapped Black Ball, taking the hint thus administered. "We ain't holdups—we thought you were somebody else. Who are ye?"

"Me?" said Leach, licking his cigarette and looking up wide-eyed. "I'm a poor lonely puncher, that's what I am. Mister Ball. I was raised by poor but proud parents, and all they left me was good manners—sometimes. Not always."

The face of Black Ball flushed and darkened with rage. Then Red Ball urged his horse up, and intervened with a laugh.

"Never mind him, feller—he's always Hike that with everybody! Let's have no fuss."

"Suits me," said Leach, with a nod. He rather liked Red Ball. The face was vigorous, even passionate, but held a whimsical good-humor. "Name's Leach—I'm new in these parts. Came up here on the trail of a mean hombre, found him, and may stick around. That banker in town gave me a letter to Miss Billings."

This news produced an instant impression.

"What about this car?" said Red Ball. "That's howcome Black got his dander up—it's the only one of this make ever was in the valley."

"Oh, that!" Leach grinned. "I done took it away from the hombre I spoke of. He give me a bill of sale, right enough. I reckon you'll hear about it in town, if you're going there."

"You mean Williams?" snapped Black Ball.

"Uh-huh. Friend of yours?"

Black Ball stated profanely that Williams was nobody's friend, in which Leach cheerfully agreed. Despite their questions, he evaded any account of his business with Williams, and this angered Black Ball anew. He shoved his brother aside and glared at Leach.

"You're too brash, stranger," he snapped. "I don't like you a bit."

"I'm right sorry, but I got no mourning to waste over it," said Leach amiably. "I don't like you even a little bit, so we're even. Red, for gosh sake drag him off before he starts a fuss! All I want is peace."

This appeal over his head infuriated Black Ball the more, but his brother, with a grin, jerked him aside and conferred, quieting his wrath, and flinging Leach a wink as though to imply Black Ball was not so bad if you took him right. Meantime, Perkins sat his horse and stared, and stared, and Leach glanced him over.

He did not like Perkins—liked nothing about him from his dingy Stetson to the Winchester booted at his stirrup. The man's thin lips suggested craftiness and cruelty—the sort of man, thought Leach, who would rowel his horse's mouth with a barbed-wire bit.

Abruptly, without a word or gesture, Black Ball separated from his brother and started for town. Perkins followed. Red Ball eased his horse over to the car, and his eves twinkled down at Leach.

"Quarter mile ahead is a turnout—don't take it," he said. "Half a mile beyond is the one for the Bar G Bar. For a foreigner, you ain't so bad—good luck to you! That is, if Williams didn't give you a job here."

Leach chuckled. "You can ask in town what Williams gave me—and what I gave him," he rejoined. "I aim to get me a job at the Bar G Bar, if I can—that's all."

"Luck," said Red Ball, and was gone with a wave of the hand.

LEACH drove on, thoughtfully. This meeting had shown him that

trouble lay ahead, beyond any shadow of doubt—trouble with

this Black Ball. From the first look, instinctive enmity lay

between them. On the contrary, Leach sensed friendliness in the

manner of the red brother—rather, a warmth lacking in the

other. The rider Perkins was a bad egg, and a most remarkably bad

one.

"If Williams told the truth," reflected Leach, "I'm going to be up against brother Perk and Black Ball. If anybody's doing any rustling, Perk is in on it. However, we'll see! No use worrying about the future, as the old feller said when they hung him."

He drove on, whistling. The road wound out of the hills by the time he reached the first turn, beside which was a sign bearing the Bull's-Eye brand burned into the wood. Then it went into a wide valley floor, with little timber in sight, and the second turnout was a broad track, wheel-marked. A little rise, and Leach found himself with a view of half the Bar G Bar ranch. He halted the car, surveying the scene.

Ahead of him, nestled beside a hill, was a tiny lake, and beside the lake a ranch house and other buildings. Timber was plentiful in spots, and so were cows; the terrain seemed more like a bit of Illinois or Ohio landscape than an almost unknown corner of New Mexico. No wonder the "natives" had kept out everybody with a view to retaining this fragment of wonderland themselves!

Thirty seconds later, as Leach was rolling down the little declivity, a bullet droned by within a foot of his shoulders and plunked through the cushions of the car.

The sharp crack of a rifle came from a clump of brush on the right.

Acting half by instinct, half by necessity, Leach jammed on his brakes and then slumped forward, leaning over the wheel and holding the clutch out with his foot. The car came to a halt, purring quietly. Leach, apparently motionless, slid his hand to his pocket and gripped the pistol there, and waited.

The morning sunlight beat down. An inquisitive steer stood and stared solemnly at the halted car. After a moment the brush moved, and a man slowly appeared, cautiously peering at the car as he camel forward. He was a bent little man, walking painfully, holding his rifle ready; unkempt gray whiskers streaked his face. Foot by foot he came hobbling to the road.

"By gum!" he said to himself. "I didn't mean to more'n scare him, and I done hit the skunk! Well, it don't matter much—"

"It matters a whole lot to me," said Leach, whipping up his pistol. "Drop that gun!"

Startled, taken unawares, the little old man obeyed the order and then stood, staring, his mouth wide open. Leach understood the well-nigh fatal error, and chuckled at the look of unmixed bewilderment on the whiskered face.

"Partner, you sort of got your rope dragging, ain't you?" he demanded. "Took me for that cuss Williams, huh?"

"I sure did," said the other. "Howcome you ain't him? This here is his car, ain't it?"

"Sure is, but I ain't him. Who are you?"

"Cook, up to the house, foreman of the ranch, and all the riders there is left. Jim Tolliver is me."

"Oh, I see! My name's Leach. You thought you'd be doing Miss Billings a good turn, huh? Well, get your gun and climb in. Is she up to the house?"

"Yep. You a friend of Williams?"

"Not me," said Leach. "I beat him up and shooed him out of town yesterday. I got a letter here for Miss Billings."

Tolliver picked up his rifle and climbed into the car, and let out a grunt when Leach started the machine.

"First time I was ever in one of these here things," he said. "I done held one up, once, over in Carson's gap."

"Held one up?" queried Leach. He was amused by the little old chap. "How come?"

"Well, sir, I was a bad actor in my time, sure was!" returned the other boastfully. "I done held up a couple o' prairie schooners in the old days, and I was in the Jimson gang that held up two mail trains in Montana. And never caught—not me! I'm too slick fer 'em. Well, I was drunk up to Carson's gap once, and done held up an automobile just to show the boys how it was done. Then I come down here and I got crippled up riding, and been here ever since. All I want before I pass out is to bold up one of them airyplanes."

Leach grinned. "An airplane, huh? What for?"

"Jest to do it. I don't hanker for nothin' else but that, and I'll die happy. I done held up ever'thing else in my time, and I want to make a good job of it."

"Well, you'd have a job holding up an airplane," and Leach laughed. "Look here, I don't want Miss Billings loosing off a scatter-gun at me—you take this letter and give it to her, savvy? Then I'll come on in."

"Sure," said Tolliver. "And I'm right glad I didn't hit ye, Leach. It gave me a bad turn, it sure fed! To think I hit a feller when I didn't go to do it, would be a sure sign I'm gettin' old and losing my grip."

Leach chuckled.

Ahead of them now loomed the house, and on closer approach it was evident that the whole place was in a run-down condition. The corral, off to one side, was a ruin. The barn and bunkhouse and house itself were unpainted, but the house looked neat as a pin. Halting the car a hundred feet from the verandah, Leach handed the banker's letter to Tolliver, who took it and climbed out, then winked.

"I'll leave this, gun set in the car—the bid lady didn't know what I was up to," he said, and hobbled away.

A QUEER little old man—a queer business all through,

thought Joe Leach, as he rolled a smoke and awaited results. The

place was poverty-stricken, and if Tolliver was the only

ranch-hand, he certainly could do little range work. When

Tolliver appeared, beckoning, he tossed away his cigarette, left

the car, and came to the verandah steps.

"Come on in," said the little man, then winked and added, low-voiced: "She's got a gun under her skirt, but don't worry. Her bite ain't as bad as her bark."

LEACH followed into a parlor painfully adorned with such objects as he had not seen since childhood—horsehair furniture, a huge chromo showing a cowboy in fullest movie costume and sporting sideburns to boot, and other such antiques. Sitting primly on a sofa and facing him was Miss Billings. At sight of her Leach swallowed hard.

His worst forebodings were realized. She was gray-haired and wore spectacles; behind them her eyes snapped frostily, and her mouth was an uncompromising, thin, down-curved line of red. Her black satin dress looked thirty years old, and probably was, and her bony contours were carried out by large-knuckled hands. She was not frail or feeble by a long shot, and looked fully capable of knocking down a visitor as well as shooting him.

"I read your letter," she snapped, in a hard voice. "What you want with me?"

Leach summoned up all his courage. He knew at a glance this old lady was accustomed to being treated with fear and respect; she was prim, neat as a pin, suspicious. Leach turned and waved his hand at Tolliver, still in the doorway.

"Get out of here, and shut the door!" he said. Then, turning: "I'd like to ask, ma'am, if you're quite comfortable?"

"I am," said Miss Billings, frowning at him. Leach sank into a chair and grinned.

"Then you'll be glad to have me get likewise, ma'am, that being only hospitable. I don't aim to get a thing on your floor, now—a whiff of real puncher tobacco might feel right good to you for a change, while I make my proposition. You see, ma'am, I've been down below, as the natives call the outside country...."

He rattled on, meantime putting his hat in his lap and carefully constructing a cigarette above it, while the old lady looked on with a face of stony astonishment. She seemed too stupefied to speak, but Leach did the talking for two until he touched a match to his cigarette. Then he started in afresh, giving her a sketch of his own life, until finally she laid down the knitting, folded her hands, and broke into his flow of speech.

"I ain't interested in your family history, young man," she said. "And you're the first person has smoked in this room since my brother died."

"Thank you, ma'am," said Leach. "That's a real compliment! Now—"

"Now," intervened the old lady firmly, "you get off your chest what you're here for, and do it quick!"

"I'm here with a proposition to unload," said Leach promptly. "If I do say it, I'm a top cow-hand, ma'am. I got five thousand dollars in the bank at Sunrise. This here ranch is the prettiest and likeliest spot I've seen in a coon's age—and there we are! You say the word, and I'll buy an interest in this place and start building it up. Five thousand will go a long ways besides painting the house!"

He leaned back, dragged at his cigarette, and waited.

Miss Billings stared at him for a long moment. She took off her steel-rimmed specs, looked at them, put them on again, and once more stared at Leach. A tiny color was coming into her face, tokening her inward excitement, and for an instant Leach found himself regretting the deception he was practicing.

"Why—why—I don't hardly know what to say!" exclaimed Miss Billings, her bony fingers twisting and untwisting in her lap. "After what that letter said, you'd ought to be straight—and your face looks straight to me. Goodness knows, the place needs something done to it, and I ain't had the money to spare, what with lawsuits and all—"

She broke off. Evidently, she was afire with the prospect, and as her stony features warmed, Leach suddenly found that she was not nearly so repellent as he had first thought her. At his whimsical smile, her lips twitched a little.

"You ain't a bad sort—I believe you know how to do things!" she exclaimed. "It's the truth this place has gone to rack and ruin, and to have a spry young chap like you to work it, would be a godsend. Still and all—I reckon not. How much do you know about the place?"

"Not much, except a lot of talk I picked up in town," said Leach truthfully. "I picked up right smart of it, too."

"Hm!" She gave him a shrewd look. "I'll bet you did. Maybe you know a man named Tom Crocker, down below, has lawed me out o' this property."

"So I heard, only he don't seem likely to get it in a hurry," and Leach chuckled.

"Well, he's got the law with him, anyhow, so I reckon I can't sell you an interest, And 111 say flat out I ain't got the money; to hire you."

"Money ain't all in this life," observed Leach. "If you were to raise cows, where'd you sell 'em? Here in the valley?"

"If it wasn't for this lawsuit, yes. We've got a fine breed here. But now I can't sell a head—folks will back me up, but they won't pay out money for doubtful property."

"That's only human nature," commented Leach.

"Anyhow, I can't take you up. It wouldn't be fair to you, savvy?" she pursued, with a sigh of regret. "I got a chance to take in a boarder, and that's how; bad off I am, young man. Takin' in boarders! Meantime, Bar G Bar cows are getting lost."

"So I suspicioned, from what I picked up." said Leach.

The old lady's eyes bit out. "Oh, ye did! Some folks around here think I'm a fool female, but I ain't. I bet I know where a lot of my mavericks are going."

"So do I," drawled Leach, "after meeting up with a gent named Perkins. A dog's hind leg would look like a ruler alongside that human corkscrew."

"Hm!" commented the old lady. "Yoit and me see things the same way, young man! I wish to thunder I could sign up with you, but it can't be done."

"It might," said Leach thoughtfully. "My idea would be to pick up a few riders! and go right to work—quick and quiet.

"We'd maybe be lucky enough to catch one or two gents in the act of branding your calves. Anyhow, we'd get the place in shape by summer, which same ain't so far away. As far's you selling me an interest goes—Hm! Might get around that."

"Howcome you're driving Williams' car?" demanded the old lady suddenly.

Leach produced his bill of sale and handed it over.

"We had an argument. He done swapped cars with me to even up."

"And according to that letter, you paid him out pretty good. Well—"

"Look here," said Leach earnestly. "Suppose, ma'am, I was to put in my money and take a one-fourth interest in the place—"

"Let me tell you the situation," interrupted Miss Billings with some animation. "I own ten per cent of this place. My brother had willed me the whole thing, but he died suddenly and his will couldn't be found—never has been found. The ninety percent went to two children by his first wife. They live in Denver. They sold out to Crocker. I fought it, and Crocker beat me. That's the law. As a matter of fact, this here county is right back of me and Crocker or his men can't get a foothold to grab the place, while I live. With you, it's another matter. The folks here wouldn't back up a foreigner."

"All right," came the prompt response from Leach. "I'll chip in my five thousand, for which you'll deed me your ten per cent, share of the place. Then we'll make an agreement to share and share alike in all that the ranch earns, as long as you live. It'll be mighty queer if I can't sell Bar G Bar stock in this valley—branded or unbranded! Then I've got a little more money I can reach, if we need it. In case Crocker gets possession, we'll make him pay for the improvements, anyhow; meantime, you'll be secure as to any income we roll in, and my money will be protected by the ten per cent. How does that suit you?"

The old lady's eyes glistened. "Fine! Only, it ain't right fair to you—"

"Fair enough to me, never worry," said Leach. "If you say the word, I'll drive you to town and we'll let your lawyer: frame up the agreements."

Miss Billings put out her hand. "It's a bargain!" she said. "Young man, I like you. You're square as a die—a body can see that in your eye. We'll go to town right after dinner, for I've done promised my boarder real flapjacks—my land! I forgot the boarder. Set still, now, until I get back. You'll want to live here, of course? The bunkhouse ain't hardly fit—"

"If you can give me a room until we get the bunkhouse fit, then it'll be fine," said Leach. "I'll get your man Tolliver to raise a few riders—he probably knows everyone."

The old lady nodded eagerly and rustled out of the room—leaving behind her a young man who was exceedingly miserable.

LEACH had won the game for his employer, but the victory was

tainted. He bad won it by lies and deceit, to put the thing

badly, and it left an evil taste in his mouth. The more he saw of

grim old Miss Billings, the more he liked her—and the less

he liked himself.

"Still and all, it's not so bad," reflected Leach. "I'll be using Crocker's ten thousand as he wanted it used, to put this place in first class order. This agreement will put the full place in his hands, but it will also bind him to pay the old lady fifty per cent of the profits—no, it's not so bad! She's darned well protected. But I hate to think of the showdown that's bound to come some day. I hate to think of her trusting me, and then finding I've deceived her—whether in her own interest or not."

The sound of steps in the hall brought him out of his gloomy mood. Miss Billings came in, and held open the door.

"This here's my boarder, Mr. Leach—meet Miss Jones. City girl, out here for her health. She ain't bad, though, for a city girl—rides right well, too. I hope you all will get on and be friends."

"I know we will," said Sally Crocker, holding out a hand. "Glad to meet you."

Leach swallowed hard, and became red. Sally Crocker, of all people—here!

"Yes'm," he returned, as he shook hands. "I sure hope we'll be friends—"

"I'm going to see to dinner," said Miss Billings. "Sally, show him around the place, will you? He's going to run the ranch for me. Make yourself to home, Leach—see you later."

She disappeared. Sally Crocker regarded Leach, her eyes dancing.

"How on earth have you managed it?"

"By lies," said Leach gloomily. "Honest to gosh, Sally, I could kick myself! I'm a liar. It makes me sick to think how I'm deceiving that old lady—even if I am binding your dad to make her comfortable for life!"

The girl regarded him critically.

"There are different kinds of lies, Joe," she said slowly. "Man's lies and coward's lies. I don't ever figure you as telling the wrong kind."

Leach flushed. "Me neither, until now. But I'm not so sure—I hate to lie to that old lady. I like her fine, and she trusts me. The only good thing about it is that her interests won't suffer. It's what shell think of me, later, that makes me squirm."

"Maybe she won't think so hardly of you," and the girl smiled suddenly. "So you didn't know I was here? Well, I am. And I'm going to stay. I met a fine young man yesterday, and he's coming over to see me pretty soon. Ball is his name."

Leach started. "Huh? Which one? Black or Red?"

"Black—"

"All right." Leach grinned. "You can have him if you want, after I get through with him. Meantime, Sally Crocker, you're going to marry me, and I reckon we're private enough right here to make up for lost time—"

"I reckon we are," said Sally demurely. "Only, you'd better shut the door—"

Leach shut it.

AS Tolliver had said, the bark of Miss Billings was worse than her bite—but the old lady could bite. Only rheumatism had kept her from maintaining her fences single-handed. She had energy plus, and no lack of fighting spirit. Beneath her forbidding exterior she was shrewd but kindly.

Old Tolliver, the only soul about the place, welcomed the news and instructions given him with a whoop of joy, and voted to accompany them to town, where he said he could pick up at least three riders at once. Sally decided to stay on the ranch. So, dinner over and the dishes washed, Leach got under the wheel of his car and all three set forth.

Once in town and settled with Miss Billings in the office of her lawyer, Leach gave his attention strictly to business. The deed made out which was to make him actual owner of her legal share in the ranch, he was careful to see the ensuing agreement so worded that the old lady would receive for life half the ranch profits; and, since Leach was acting in reality as agent for Crocker, the latter would be bound to respect this agreement. Leach's half share of profits would of course go to Crocker.

This all took time. His check handed over to the lady, Leach took the deed to have it recorded, then sought the hotel. He was to meet Miss Billings at the car in half an hour, after she had done some shopping, and needed this time to write Crocker. He did so, setting forth what had been done and enclosing his copy of the agreement.

"I don't know whether this will suit you," he went on, "and if it doesn't, you can fire me. If it does, you'll owe me the bonus of five thousand promised for reaching a settlement. What will happen when it comes out that I'm your agent, remains to be seen. Miss Billings is a fine old sport, needs every cent she can get, and probably will put most of it back in the ranch anyhow. You can afford to be generous. If you don't think so, then I'd quit work for you. The real trouble on this place hasn't started yet, but starts quick. Make up your mind whether you back my play or not, and let me know."

His letter sent at the post office, Leach returned to the car and there found Miss Billings standing in talk with Red Ball. The old lady turned.

"Leach, this is Red Ball, one of your neighbors. This here is my new range foreman, Red. He's going to try and work up the ranch a bit."

Red shook hands solemnly, a twinkle in his eye.

"Glad to meet you," he said. "I was just askin' Miss Billings if she wanted to send over anybody to represent her—our spring round-up starts in Monday."

"I reckon I'll get over in the course of the week, thanks," said Leach carelessly. "We'll be mighty slow getting started, I guess. There's the buildings to paint and hands to hire and fences to build and so forth. You won't mind looking out for Miss Billings' interest if we don't get over right off?"

"Sure not!" said Red Ball cordially. He shoved back his hat and laughed. "Black handles most of the details, and Perk—our foreman. They don't let me run things, much."

Leach caught a hint of irritation here.

"Well," he drawled, "I don't mind saying, Red, that Black and me will sure tangle one of these days. We strike each other just that-a-way. Now, I don't want to come into this county and start fighting. I don't want a fuss, as much for Miss Billings' sake as my own. So I won't come over to your round-up at all, I guess. I'll send old Tolliver over, maybe. The longer me and Black can keep apart, the better all around."

Red Ball grinned. "Feller, you're all right!" he said. "So far as Black goes, you and him can go to the mat any time, and I hope you lick the tar out of him. After what you done to that gent Williams, maybe you can stand up to Black. I'll say he feels the same way towards you, so it's all square. Well, luck to you! So long, Aunt Hennie."

Miss Billings, it seemed, was known as "Aunt Hennie" to a large part of the valley's population.

Leach helped stow her purchases in the car, and Tolliver showed up a few minutes later. The old crippled puncher was jubilant.

"I got three fellers showin' up in the morning," he announced mysteriously. "And not a word hinted around, neither!"

"Who are they?" demanded Miss Billings suspiciously.

"Ollie Poe and the two Smith boys. Suit ye?"

"Hm! I reckon they'll do," she said grudgingly. "If Ollie Poe can leave licker alone he may be all right, and the Smith boys are good hands. They'll do to start with. I got a load of paint coming out tomorrow. Leach can stop at Saunder's place on the way home, and we'll get him and his two boys over to do the painting. I judged you all would have your hands full for a spell with fences, cows, branding, hosses and rustlers."

"I reckon so," assented Leach. "First thing is to get your corral patched up so's it'll hold a couple of head of stock. Got any hosses?"

"Two broke to harness, and the rest are running wild, what's left. We got a lot of old posts and lumber in the barn, so the corral won't amount to much as a job."

WITH Tolliver perched in back, on top of the small mountain of

parcels, Leach drove out of town and started up the valley. Then

he asked the question on his mind.

"What about these three new hands of ours, ma'am? If what we suspect is so, can we depend on 'em to buck up against the Bull's-Eye outfit?"

"Shucks! That outfit ain't loved much," and the old lady sniffed. "Them boys ain't liable to scare, if that's what you mean. You're a foreigner and they'll shy at you for a while, but since they'll be working for me, they'll be all right. How do you like my boarder?"

"She's a peach," said Leach with enthusiasm.

"Well, mind your step," admonished Miss Billings severely. "She's a right nice girl and I'm going to watch out for her—poor motherless thing. I don't want no lovesick punchers mooning around, neither. So don't you get too durned ambitious all to once, young man."

Leach chuckled. To himself, he wondered what Miss Billings would say did she know the truth!

En route home, they stopped at a small ranch where Saunders and his sons were engaged for the painting job. Then home, late in the afternoon, where Sally Crocker welcomed them beamingly.

"Supper's about ready," she declared, "and if you'll look at that corral, Mr. Leach, you may observe some changes. I didn't set any new posts, but I've got half of it repaired so she'll hold a. small remuda if you don't act too rough."

"Bully for you!" said Leach. "If you'll come along and show me that corral—"

"Do your own looking," and she laughed. "I'm busy with supper."

Inspecting the corral, Tolliver scratched his head. "By gum," he observed, "that there gal is all right! I wouldn't mind marry in' her, if she can cook!"

Leach chuckled anew.

WITH daylight, Leach was at work on the corral, and his three

riders blew in by breakfast time, with a horse each. The two

Smith boys were capable, silent men; Ollie foe was a sawed-off

little chap, with a gallegher rimming his face and bright,

twinkling eyes. Leach kept Poe to help him finish the corral and

sent the other two out to round up two or three of the half-wild

cayuses. He instructed them to keep well to the west and not to

show themselves on the other side of the range—whereat they

grinned and departed.

Poe said almost nothing until the morning was half gone. Then, as he and Leach rested after setting the last post, he regarded the foreman shrewdly.

"I see you got a saddle and outfit laid ready. Figger on breakin' a hoss to-day?"

"I figure on using one," said Leach. "You and the other boys too."

"East or west?"

Leach met his shrewd gaze, and grinned. "Well, I reckon we might scatter along the east side of the range and sort of see how the fence lays between us and the Bull's-Eye. Object?"

Poe bit at a plug of tobacco. "I don't object to nothin'," he said. "I got a gun in my roll, too."

"Then let's get finished here and put the bunkhouse in shape before dinner," said Leach.

The Smith boys came in with four ponies before noon and pitched in to the work, so that dinner saw alt hands ready for the afternoon. No class distinctions obtained at the Bar G Bar. Miss Billings presided over the dining table, Sally sat at the other end, and, on a side, the foreman and riders filled up the intervening space.

"Corral looks pretty good," observed Miss Billings. "What you planning this afternoon?"

"Why," said Leach, with a negligent air, "first thing is to see how the fence stands and get some wire from town. The four of us will sort of look over die east line and up above the east valley to-day. I want to get the lay of the land in my head, too."

The old lady regarded him over her spectacles. Then Sally broke in.

"I'll go with you, if I may—"

"Nope," said Leach. "Not to-day, I guess. If you want to help, I'd like to get a report on the west line fence up to the hills."

Sally nodded. Miss Billings, however, caught the look that Ollie Poe shot at the Smith boys, and her eyes twinkled.

"I got two Winchesters," she announced. "Coyotes been pretty bad up in them hills, Leach. You and Ollie might take along a gun each and shoot one or two."

"We might," said Leach soberly. "That's a right good notion, ma'am."

DINNER over, Leach wasted no time gentling a wild cayuse, but saddled one of the harness broke nags and set forth with his three men. Once away from the house, he halted them.

"Boys, you all know the ground here and I don't, so Poe had better slay with me. You other two can circle around and join us later. I'm open to suggestions."

The two Smiths looked at each other, then one spoke.

"Depends on what you're lookin' for."

"Trouble," said Leach. "If you want it straight, with the Bull's-Eye. Miss Billings thinks somebody has been rustling around here, and I think it was Perkins and Black Ball, if anyone. They know I've started here. They might figure on getting to work quick, branding all the calves they can find and maybe shooting the mothers, so there'd be no suspicion at their round-up next week. Or they might be up to anything. I'd like to scout around and see."

"In that case," said one Smith, "me and Eddie can circulate around the upper end of the east valley and work back. Poe can bring you along the same way to meet us. S'pose we find anybody at work?"

"Take Poe's rifle. Shoot first and ask questions afterward if anybody's using a branding iron on Bar G Bar land."

"Suits me."

The two Smiths went their way.

Poe followed with Leach, but leisurely, and after a time struck from the open into the brush until they gained the hill beside the lake. From here, Poe pointed out the two valleys coming in V-shaped fashion to the lake, with the rough hilly stretch between. That to the east rose gently in rolling uplands, studded with brush, rolling on and on for miles.

"On that mesa yonder is the fence-line, somewheres," declared Poe, then indicated the rougher territory between the two valleys. "The Smith boys have gone up yonder—if anyone's rampagin' around there, they'll flush 'em. You and me might separate and make up the east valley, and meet yonder by the big patch of scrub-oak—see it?"

Leach nodded, got his bearing, and urged his horse away.

He had no definite expectations, but knew if he could come upon any crooked work and strike a sharp, sudden blow, it would be huge gain. Who hits first hits hardest, sometimes. He could only figure on what he himself would do were he in the shoes of Perkins—and really rustling Bar G Bar cattle. The logical thing to do would be to grab all the mavericks in sight and do it without a moment's delay, then sit tight and see what happened.

FOR a long while he rode along without incident. At length he

located the fence line, now nothing but bare posts, and some of

these down completely. Leach eyed the dotted line grimly and was

not astonished at the complete disappearance of the wire. It

would be found, probably, neatly rolled and stored away in some

Bull's-Eye shed.

He circled out into Bull's-Eye territory and came around back to the fence line again, following this. He could make out no sign of Poe. From the looks of the cattle he encountered, his own stock must be well worth rustling, but the two herds apparently drifted in company along this part of the range.

Leach pulled up suddenly at the clear, sharp report of a rifle-shot.

Somewhere on his right—his horse's pricked-up ears directed him to a heavy thicket of brush. He searched in vain for any sign of a fire, and anger rose in him hotly. He had scarcely believed in his own conjectures—only the cruel lines of Perkins' face had caused them. Were they indeed shooting the mothers and driving along the mavericks and calves, to be branded at the coming round-up? That would be the safest game to play, of a surety, but it was even more despicable than a mere theft of calves. Destruction added to robbery.

Another shot. Leach headed for the thicket, a large patch where the bodies of cattle might well lie undiscovered. Farther along he saw a buzzard circling, and another, lifting as though disturbed from work. Poe had probably flushed these—other bodies lay there.

Leach headed for the thicket, where the

bodies of cattle might well lie undiscovered.

It looked like a clear enough case. Whoever was in that thicket was too busy to keep watch, and Leach loaded his pistol as he approached. Then, slipping from his saddle, he left his horse with reins hanging and worked his way into the tangle, pistol in hand. After a bit he heard a shout, and was guided by it.

"Any more?" called a voice, and the response came at once.

"Nope. Done wasted a lot o' time in this chaparral."

"Drive them calves out, then, and I'll work off towards Black Ball."

Leach hastened along, cursing the undergrowth—then came abruptly out into an open space. Whether he or the prior occupants were the more surprised was uncertain.

Two men were here—Perkins and another, ponies to one side, a pair of frightened calves shoving off into the brush. To the right lay two dead cows.

Both rustlers, belonging to the Bull's-Eye as they did, were too utterly astonished by sight of the intruder to move or speak—too uncertain what his presence meant. Perkins was in the act of mounting; he remained with one hand on the pommel, staring over his shoulder at Leach. The other man was on the far side of his horse, about to replace his rifle in its boot. He, too, stood staring.

When it came to shooting first, Leach hung fire. Undoubtedly the proper thing to do, such ice was hard to break. To shoot down a fellow-man is no light task.

"Well, you boys seem to be having a good time," he observed lamely.

"What's it to you?" snapped Perkins.

"Depends on whether those cows over there are yours or mine." Leach shifted gaze, at a movement from the puncher. "Careful, you! Drop that rifle—

"You vamose, and do it quick," commanded Perkins.

"You two gents put 'em up," said Leach, his pistol lifting. "Way up, boys! You with the Winchester, drop her—"

Perkins promptly obeyed, but not so the Bull's-Eye puncher. His rifle whipped from sight, and so did he, behind the shelter of his horse. Leach fired promptly—sent two bullets tearing through the poor beast. The pony screamed shrilly and reared, while the puncher quietly toppled over, and the two fell side by side.

The pony screamed shrilly and reared,

while the puncher quietly toppled over.

From Perkins burst an oath of fury, and his hands went down. Leach swung on him, and fired. Perkins jerked backward, fell, and then sat up, clutching his right leg.

"Quit it!" Perkins cried sharply. "You don't need to murder me!"

"Wouldn't be much loss if I did," said Leach. "Get yourself tied up. Where's Black Ball working? Which direction?"

"Up the fence line a ways." Perkins swore heartily as he felt his leg. "Durn you, how d'you expect I'm going to ride with a bullet through my leg?"

"That ain't my funeral," said Leach.

White-faced, he advanced to the feebly kicking horse and put the poor brute out of its misery. A glance at the puncher was enough—those two bullets had gone through horse and man alike. Leach grimly crossed to the dead cows, saw their brand, and nodded.

"You double-danged outfit of thieves!" he exclaimed savagely at the Bull's-Eye foreman, now at work over his stripped and bleeding leg. "Now see what you've gone and done, for the sake of stealing some blamed calves!"

"You'd ought to be real pleased with yourself," said Perkins glumly. "What you've done seems to be a plenty. Bone ain't broke—that's lucky. Bullet clear through—"

"Black Ball does the branding, I suppose?"

Perkins flung a scowl at mm. "Branding what?"

"Forget it," said Leach in disgust. "You're caught with the goods, feller. Want to go, do you? Then get yourself bandaged."

Perkins obeyed. "I said this was a fool play," he grumbled. "Black had to be a durned hog, and I knew it'd make trouble. But you'll pay for this killing, I can tell you—"

He fell silent, cursed the quirt attached to his wrist as it got in his way, and then finished his temporary bandage. He squinted up at Leach.

"How d'you reckon I'll get into the saddle, huh?"

"I'll give you a hand up."

Perkins made an attempt to rise. Leach went after his horse, which had jumped to a little distance, and brought the animal back, then helped Perkins rise on his good leg. The foreman was anxious to be gone, and showed it. With many curses he expended every energy to get into the saddle, and finally managed it by aid of Leach.

"Now, if you'll gimme them reins," he said, white-lipped with pain, "I'll be on my way."

"Why, sure!" Leach grinned. "But I didn't say anything about you being on your way, did I? You'll go my way. You don't want any reins. You just sit tight and hang on. Maybe you figured on riding home, but you got another guess coming."

"Huh?" demanded Perkins. "You'd make a wounded man—"

"Shut up," snapped Leach with sudden anger.

He picked up the hanging reins and led the cayuse from the opening. He knew exactly on what Perkins was figuring. Those pistol shots, entirely different from the clean, sharp cracks of a rifle, would certainly have been heard by Black Ball, and the latter was probably now on his way to investigate their cause.

Forcing a way through the brush, Leach was in sight of the open when a branch slapped the horse, which reared back. Leach turned—and without warning Perkins, slashed down with his quirt. Struck full across the face, Leach staggered back. Next instant, horse and man were plunging off headlong. A pistol cracked, and again, the bullets flying close.

Leach jerked out his own weapon, then paused, and stood feeling the red weal across his face. He shook his head and replaced the pistol.

"No, I reckon I've done enough—and I couldn't hit him anyhow," he muttered. "Don't want any more killings right now—"

PERKINS had quite vanished from sight by the time Leach

regained his own mount. He climbed into the saddle and sat

inspecting the country. No one was in sight—there was no

sign of Black Ball or other riders. Rolling a smoke, Leach sent

his horse forward, and presently discerned a horse and rider

approaching at a gallop. He recognized Poe, and drew rein.

"That you shootin' over this way?" called Poe, as he approached.

Leach nodded. Pointing back to the big clump of brush, he explained what had taken place. Poe, it proved, had seen nobody, but had made out the faint smoke of a fire off to the right, and had been heading for this when he heard the shots.

"Black Ball is doing some branding there," said Leach. "Hm! You go and look over this place, Poe, then ride home and telephone the sheriff. Get him out here right away, before Perkins can bring any men back to remove the evidence."

"Huh?" Poe stared at him. "And let you meet up with Black Ball? Not much. I'll stick right here with you until—"

"Either you take orders from me," said Leach ominously, "or else you quit."

"Well, doggone, I don't aim to quit," returned Poe. "But—"

"No buts," cut in Leach. "I'll meet the Smith boys and look up Black Ball."

Poe disconsolately moved away, and Leach rode on along the former fence line. He was not at all elated by having just killed a man.

POE disappeared in the scrubby brush. Perhaps five minutes afterward, Leach descried two figures breaking cover from a deep swale off to the left. At sight of him they halted, then came toward him rapidly. Both riders were strangers to him. On closer approach he saw that their horses had been going heavily, and one of the two men seemed to have an injured arm, as it was hung in a rude sling. Leach drew up, disappointed and yet relieved that neither of these was Black Ball.

"Howdy, gents," he greeted amiably, when they drew rein. They were not prepossessing in appearance and inspected him scowlingly.

"Who are you, feller?" demanded one abruptly. Leach chuckled.

"You tell me and I'll tell you. Suit you?"