RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

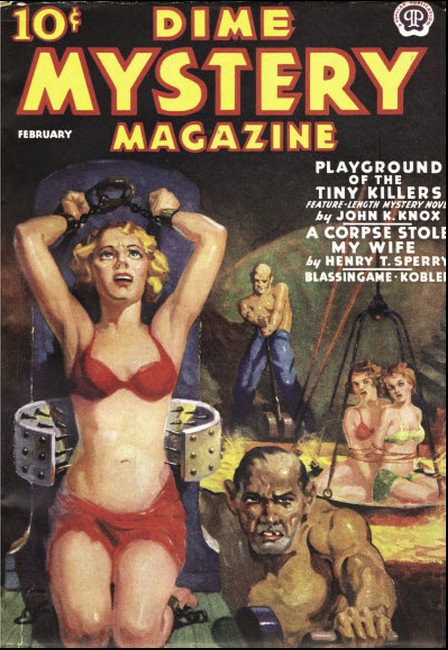

Dime Mystery Magazine, February 1938, with "A Corpse Stole My Wife"

I laughed at the legend of the one-legged specter who walked the desolate shore searching for his lost bride and his lost leg. But when my lovely wife vanished, and my best friend lay dead, his throat slashed and one leg crudely chopped off above the knee—stark terror seized me in its relentless grip!

JOEL THOMAS ran a finger around the inside of his collar and glanced uneasily about the room as if he expected something to jump out of a corner at him. Sixty feet beyond the door the surf pounded in its endless rhythm—a long, hissing roll, and then silence for a moment, another roll and a thud, as of some gigantic body being hurled upon the sandy beach. Joel clenched his hands together and leaned toward me.

"All right, I'll stay, Barry," he said in a tense voice, "but for God's sake hurry back. Something's gone wrong with this place—something..."

I nodded and stood up. "Perhaps it's the place—more likely it's something worse. Thanks, Joel. I'll be back pretty soon. There's plenty to eat in the place. All the groceries Betty brought—"

I couldn't go on—something caught me by the throat as I mentioned my wife's name. Yes, Betty had written that she had stopped at Fenwick, the nearest town—twenty-five miles away—and bought supplies. I had gotten that letter five days ago. Since then I had had no word of Betty. She had not been here to greet Joel and me when we arrived at this little seaside cottage of ours. She had not been seen by any living person since posting that last letter to me. The postmaster in Fenwick had seen and recognized her—and apparently his were the last pair of human eyes to mirror the image of my wife.

I slipped on my topcoat, put on my hat. "I'm going to look up the sheriff, again," I said. "He's the only person around here to whom we can look for help, since the state police have given up. We've searched the country for a distance of fifty miles in every direction—"

"Barry—" Joel interjected—"I hate to mention it, but there's one direction we couldn't search in... East—"

I felt my body chill as I looked out the window at the night-black, foam-crested billows. East... Yes, I had looked there, too. For a whole day and a night I had searched along the beach, while Joel went with the police, dreading every moment that I would find what I sought. Seeing in every spar and log tossing in the surf, the drowned, lost body of the girl I loved...

"The Coast Guard—" I said—"I notified them while you were gone. There is a station every five miles along the ocean front. They are keeping a patrol—"

Again Joel interrupted me. "I'm—I'm not thinking of quite the same thing you are, Barry," he said. "I—I know it's crazy—but to save my soul I can't get the idea out of my head that it—it's something not quite as simple as drowning." He paused for a moment and looked up at me with an expression of unveiled dread in his eyes. "Maybe it's childish, superstitious—but I can't get that old yarn about Captain Home out of my head. Ever since we found that Betty had disappeared..."

I wanted to laugh, but something prevented. And I was fast approaching a state where I felt I would never laugh again—even at such silly nonsense as Joel Thomas was suggesting. I patted him on the shoulder, went out the door, got in my car and set out for Fenwick. Once I looked behind me and saw Joel standing in the lighted doorway, watching me. At the same moment, off to the left and behind the house, seeming to arise from the sea, itself, I thought I glimpsed a huge black shape, roughly human-formed, and seemingly wading toward the shore. Then a turn in the road forced my eyes' attention, and when the turn was completed the house and the sea were blocked from my view.

I slowed down, with the half-formed intention of turning back to investigate. But my common-sense—that attribute we are all so proud of with so little reason—told me that my eyes had played a familiar trick on me: dazzled with the lighted image of Joel, when shifted for a second toward the sea, they retained his outline and superimposed it against the background of the water. Just as, after staring directly into the sun, one may see a black disc wherever else one looks for seconds afterward.

Just an illusion, I told myself—and pressed down on the accelerator. I have wondered since how many horrible deaths have been caused by this idiotic faith human beings repose in "common-sense"...

I HAD to drive half-way across the state to get Sheriff Travis, losing six full hours in the process. He was a florid, paunchy individual with a composed expression and mild blue eyes. He had been addressing a class on psychology at the State University and was as far from the conventional picture of the "hick cop" as one could imagine. On his former visit to my cottage, he had quickly decided it was a matter for the state police, and departed, having made it clear that there was little he could do, himself. I supposed that there was still little reason for dragging him down there, but somehow, I had far more faith in him than in a whole army of state troopers. He consented to come with gracious willingness.

We had had little time to talk, the time before, but as we drove back, now, I told him everything I could. With his tactful, gently-spoken questions he took me back over Betty's and my whole life together, back to the very day I met her. I told him about every friend and acquaintance and relative either of us had. I even mentioned the old legend about my privateering ancestor, Captain Home—told him how our beach house was supposed to be made with beams from the old seafarer's ship; related the story of his shipwreck on Fenwick Shoal, a point just opposite where our house stood, and of his death and his young wife's death in that wreck.

But I didn't tell Travis the legend which has been told for a hundred and fifty years along that coast about Captain Home and his nightly search for his missing leg and his young wife. Somehow, Travis wasn't the sort of person to whom you told that type of yarn.

Still, it was that part of the story which was uppermost in my mind as we sped along the little-used road between Fenwick and the sea. I remembered that a fisherman had beached his dory in front of the house the summer before, requested water, and then told us of seeing the one-legged old mariner stumping along the beach two miles below on the preceding night.

"'Twas him, right enough," the old fellow insisted. "Had on one o' them old-fashioned kinda hats they wore 'way back yonder when this-yere country was jest part o' Great Britain. He was kinda shadder-like, but I could see him plain enough. Funniest thing about him was thet he was walkin' jest like he had two legs—but I c'd see his left leg was off at the knee. Still an' all he didn't favor thet leg none—jest walked along as ca'm an' reg'lar as you 'r me. Didn't have ary crutch 'r stick, neither..."

Captain Home looking for his lost leg and his lost bride—a legend a century and a half old. No, Travis would find that interesting, but hardly impressive.

The house was dark when we arrived, and since there was no moon the whole scene was drowned in a blackness that was almost palpable. As I braked the car to a stop I felt a resurgence of the terror which had possessed me on that first night when I had come down here—and found the house as dark as it was now. For a few seconds I couldn't move to get out of the car. Travis's voice aroused me:

"Is there anything wrong, Mr. Larch?"

"Eh? Oh—" I essayed a short laugh. "No—no, of course not. Joel is probably taking a walk along the beach..."

But it was strange he was not waiting for us...

My feet were like lead as I guided our way toward the house with my flashlight. Then one of those febrile, baseless hopes which visit us in times of trouble came to me, quickened my dragging feet. Perhaps he had found Betty! Perhaps, even now, he was bringing her home to me...

I literally burst through the door, rushed precipitately through the kitchen, dining room and into the living room. I was frantic with eagerness to get out on the beach, to follow Joel's footprints in the sand...

I got no farther than the living room. The rays of my lamp caught and revealed a sight which will still be burned in my brain at the hour of my death. Joel was seated on the divan in front of the fireplace, his head thrown back, his body relaxed and motionless.

But no—I must amend that statement. It was not Joel who sat there—it was only Joel's dead body—and not all of that. His throat had been torn out as though a huge beast had fastened his fangs there—and ripped. And his left leg was only a bloody stump. It had been hacked off at the knee...

JOEL THOMAS was my cousin. I had asked him to stay there in the cottage while I went to Fenwick for the sheriff—stay there in the hope that some clue to Betty's whereabouts might come to him.

Something had come to him—something so inhumanly horrible that even Richard Travis, an experienced viewer of dead bodies, of mangled, murdered corpses, turned pale when he saw what that something had done to Joel.

I had condemned my cousin to his death. But there was no room in the maelstrom of horror that was my mind for self-accusation. There was only the blasting knowledge that whatever had done this to Joel was also responsible for Betty's disappearance.

I sank into a chair with a groan, buried my face in my hands. After a few moments I felt a touch on my shoulder, looked up to see Travis standing over me.

"Let's get busy, Mr. Larch," he said in a matter-of-fact voice. "We've got work to do here."

His calmness and self-possession restored a portion of my courage. I saw that he had stretched Joel's body out prone on the divan, thrown a beach robe over it. I took a large electric lantern from the mantel, and, giving Travis my flash, led the way out onto the front porch.

A few stars were out, but they gave little light. The beams of my lantern showed the board walk extending from the front stoop for a distance of twenty feet down to the edge of the sand and a drop of a couple of feet where high water was gradually undermining the slight eminence on which my house stood. As we traversed the walk I noted splotches of water on the boards. We reached the point where the sand began, and came to a sudden halt.

Travis, at my side, uttered a sudden, wordless exclamation and jumped down onto the sand, held his flash above the distinct imprint of a large shoe, the toe of which was pointed toward the house. Then his light flicked down the beach a few feet, discovered another imprint.

"Come on," he said in a strangely tight voice, "and be careful not to disturb these prints."

I followed him toward the water, and I had seen a half-dozen of the footprints, all pointed toward the house from the direction of the sea, before I realized that there was something unbelievable about them. I came to a sudden halt with a startled exclamation on my lips.

"Travis! What in God's name is this? There are no left prints—only rights. And yet they're the normal distance apart—as if—"

But I didn't dare put the rest into words. The story of that old fisherman of the summer before came back to me: Funniest thing about him was thet he was walkin' jest like he had two legs—but I c'd see his left leg was off at the knee. Still an' all he didn't favor thet leg none—jest walked along...'

"I had noticed that—" Travis's voice was still oddly tight. His flash swung slowly back and forth, covering every inch of the beach on both sides of the print for a distance of a half-dozen feet in each direction. Then he went on slowly until we came to the end of the trail—one last print—and after that, nothing but smooth sand.

I cleared my throat noisily. "This trail was made at high tide," I said. "The water has receded, after filling up the rest of the prints with sand."

Travis nodded. "Six—perhaps seven hours ago," he muttered. His flash raised for a moment, played along the black, cream-crested waves. I felt a shiver of dread, a cold spasm of fear of the unknown, creep along my spine. Abruptly he whirled around. "Let's go back. Maybe—"

He left his thought unspoken, and we retraced our steps to the foot of the walk. I swung my lantern about in a great arc—then brought it to a sudden focus on another set of prints which had escaped our notice before.

But this set was different from the first. For one thing, the toes pointed toward the sea instead of away from it. For another, there were two prints—a left as well as a right.

"Come on!" Travis was following this new trail down the beach, I in his wake. And like the first, this trail ended at high-water mark.

Travis bent above the last pair of prints for a long time. I stood above him and shivered uncontrollably. Reason told me that the marauder, whoever he was, could easily have waded through the surf for miles, if he had wished to, in order to create this effect of having come from and escaped into the depths of the sea, itself. But reason had no explanation for that set of single prints over there to our left—nor could it throw any light on a fact which, as I bent with Travis over that last pair, suddenly burst on my consciousness like an exploding bomb.

This pair of prints, although they represented a left and a right foot, were not mates! One print—the right—was of the same foot that had made that other, single trail. But the left print was a couple of sizes smaller, and of a different shape. The right bespoke a clumsily made, worn shoe. The other clearly indicated a fine, modern last. A print such as would be left by an expensive hand-turned sole—a sole, I slowly realized, such as had shod the foot of Joel's left leg...

WITHIN the next fifteen minutes Travis had gone into the house, returned with his bag, made moulage facsimiles of the two prints with materials contained in it, and returned to the house to discover that the left print was a perfect mate to that made by Joel's remaining shoe. I could have told him from the first that it would be. I did tell him, then, of the Captain Home legend—and of Captain Home's nightly search for his lost leg and his lost bride up and down this long, lonely coast.

He looked at me queerly when I was done. I forced a laugh. "Of course it's all nonsense. Still, it all fits in nicely, doesn't it? As if the old captain had found a leg at last—"

Perhaps I was a little hysterical. A silence fell between us, and the eternally drumming surf pounded back into my consciousness. Hiss—rumble... Hiss—rumble—thud... as if a heavy body had been thrown upon the beach.

Travis cleared his throat. "Have you a telephone, Mr. Larch?"

"No." This had been our refuge—Betty's and mine—from all contacts with the outside world.

"In that case, I'm afraid we shall have to drive back to Fenwick at once. This—latest development should be reported to the State authorities. The troopers must intensify their search, and tighten up their patrol of the highways. Also, I intend to notify Washington of your wife's disappearance. I believe that the Federal Bureau of Investigation will be interested."

I looked up at him. "Suppose you take my car and drive into Fenwick. I'll wait here."

Travis's eyes shifted to the divan. "Perhaps we had better both go, Mr. Larch—"

"No." There was a deadly rage growing in me. My hands ached to dig into the throat of the monster, be he living—or a century and a half dead—who had done this. "No—I'll wait here," I said.

Travis put on his hat. "I should be back in an hour and a half." Then he paused as he started for the door, and turned back. "Have you a gun?"

"A shotgun. I don't know whether there are any shells."

Travis reached under his left arm and withdrew a heavy Colt's .45 automatic and handed it to me. "I hope you get a chance to use it," he said. "I'll probably bring the county medical examiner back with me."

I COULD not stay in the room with the thing that had been Joel Thomas. I went out on the beach—without a flash, so that I would not see those footprints. For a long time—I don't know how long—I stood there watching the surf, listening to its roar. The night was dark, yet not so dark that I could not see the billows forming out there, fifty feet from shore, making a long black line.

I stood and watched and listened, and I felt the unreality of the sea—felt its unimaginable vastness and depth and mystery. And I felt a horror and a dreadful fear of it, so that I shuddered each time the hissing, glittering foam slid over the smooth sand, scampering with white, hurrying fingers toward my feet.

Yet I stood there for two hours, and it was only when I realized that I had become numb and chilled with the damp cold of the night that I turned to go... Turned—and came to a paralyzed, breathless halt.

Not two dozen yards down the beach from me walked a figure out of a nightmare. It seemed to glow with a luminosity of its own—with the blue and purple darkling fires of putrescence. And it was garbed in the tricorne hat, the long coat and knee-breeches of the Eighteenth Century. It was going away from me—and as it walked I saw that the left leg was off at the knee; that nevertheless the figure strode along as though two sound legs supported it...

I moved fast, then, with the electric surge of my rage and hatred and despair lashing my muscles into a frenzy of action, so that I sped toward that macabre figure like a stone shot from a catapult.

And, seemingly with my first leap toward it, the figure sank from sight in a flash—as though the earth had literally opened and swallowed it up. And by the time I had reached the spot where I had first seen it, there was not the slightest sign of it anywhere.

Cursing and raging, I stormed about for a time in the dark. Then I raced to the house, snatched up my lantern, and returned. And now I saw the thing on the beach which the darkness had veiled from my eyes before: lying at the highest point reached by the surf, at a spot six or seven yards below where I had been standing, a human leg, still clad in sock and shoe, lay there. Beginning at the leg, a series of single prints—of a large right shoe—led down the beach, to turn abruptly, as I found a few seconds later, at the point where the apparition had disappeared, and head back into the sea.

And that was all. There were no returning prints, no sign of anything in the surf, although I spent another hour pacing up and down the beach, playing my powerful light on the billows, keeping vigilant watch in every direction. There was nothing more to be seen...

At length, half stupefied with the stress of the emotions of the night, I went back to the house, climbed upstairs and threw myself on my bed. There was no more I could do—not that I had been able to do anything. I would have to wait until Travis returned...

Travis... My numbed brain suddenly was jarred to clarity. Enough time had elapsed for him to have accomplished his mission twice—and he had not yet returned...

And then all thoughts of the sheriff vanished from my mind to return no more that night. My ears, suddenly acute, had detected a sound—faint and far away—but nevertheless distinct from the muted roaring of the surf. It was repeated, a little louder, a little clearer in one of those rare moments of absolute silence in the lashing of the surf...

MY heart grew tight in my breast as it swelled with an overpowering emotion I could not name. It was the sound of a voice, seeming to come from a great distance—a voice which called to me, and spoke my name: "... Barry... Barry... Oh, God..."

Betty's voice!

What I did during the minutes immediately following will never be clear in my mind. I know that I rushed about the house like a man demented, searching insanely, desperately to locate the source of that voice—for it had seemed to me that, far away though it sounded, it yet emanated from within the four walls of the cottage. I called, and paused, trembling, to wait for a repetition of Betty's call—but it did not come. I yelled and shouted until the place rang with sound—then paused again, cold sweat standing out on every portion of my body. No answer.

At last I went out-of-doors, circled the house frantically, calling out with all the power of my lungs to the girl I loved. No response.

Finally, sick with disappointment, plunged into blackest despair, I went inside again, sank exhausted into a chair on the other side of the room from Joel's corpse.

The conviction came to me, then, that it had been an hallucination. It simply could not have happened the way it had—seeming to come from inside the house, and yet far away.

And then, as I sat there, strange thoughts began to drift through my brain. Perhaps there really were such things as spirits. Perhaps Betty had been calling to me from the depths of the sea. Captain Home had taken her—in lieu of the young bride he had lost... He was holding her prisoner in some weird dwelling of the drowned, far out and countless fathoms deep in the ocean... And from there, her voice had reached me—calling to me—begging me to come to her and bring her back from the dead...

My eyes went to the front door. It was slightly ajar. Clear and compelling, the eternal sound of the sea came through it. It, too, was calling... calling...

I reached the door with a rush, flung it open—and came to a rigid, taut-nerved halt. Once more Betty's voice had reached my ears. Louder, this time, and clearer:

"No—no! Oh, please don't do that... Oh, dear God! Barry... Barry!"

I whirled, and in a rush I was through the dining room and in the kitchen. There was no question about it now: it was really Betty's voice—and it was coming from the rear of the house!

I slid to a stop in the kitchen, and again I heard her voice call my name, clearly, but still as though from a great distance—and with a peculiar resonant quality, as though it were distorted by subterranean echoes.

I slammed open the back door, snatched up a shovel and a pick from the back porch, and went to work.

THAT last call had definitely placed the source of Betty's voice. Unbelievable as it seemed, it had come from a point mid-way in the back wall of the kitchen. It was unreasonable, impossible—but I attacked the panels of the wall with my pick, pried back one board and wedged the shovel between it and the wall while I got a longer purchase with the pick and ripped it out. And I found two vertical pipes, capped by short elbows staring at me like two black, blind eyes.

Suddenly I remembered the original builders of the house had had a different water system from ours—and that it had gone dry. These were the old pipes which had come from their gasoline pump.

I pressed my ear against one of the pipes, and a faint sound of scuffling, of muffled cries, came to me. Bitterly, then, I regretted the fact that I had merely told the agent to change the water system and had not overseen the job, myself. I did not know where these pipes led.

But there was a way of finding out. I grabbed up my shovel, pick and lantern and rushed out the back door and went around to the rear of the house. I could see, now, the two old pipes descending from the floor of the kitchen, in the open space between the house and the ground, to disappear into the earth. I had noticed them before, but had never thought to question where they led, knowing, in an incurious sort of way, that they were part of the old water system.

But within five minutes I had dug down through five feet of sand, and discovered the direction they pointed after leaving the elbows joining them with the vertical lengths. And in that instant I identified the source of the old system.

A hundred feet back of the house there was a little hillock, not more than three feet in height, but completely overgrown with a dense mass of bushes. It lay in the precise direction to which these pipes pointed.

The next minute I was slashing at that undergrowth with the blade of my shovel—and a matter of seconds after I had cleared an area ten feet square I found freshly turned earth, and was digging into the sandy soil with frenzied energy.

At length my shovel hit upon wood. I flung it away, got down on my knees, then, and swept the sand away with flying hands. A four-foot square of wood was revealed. I snatched up my pick, sank the sharper end into the wood and pried up with all my strength. The square of wood came up. I flung it back and shot the rays of my lantern into the depths revealed.

I saw the hazy outlines of a figure far below me. I heard a woman scream—and then I leaped straight for that shadowy, evil form there below. I forgot about the gun in my pocket—forgot everything save the hunger of my hands to fasten about the throat of that macabre apparition at the bottom of the well...

It seemed to me that I fell for many minutes—and that all the time the figure of the ghostly mariner stood there, looking up at me with a leering grin on his scarred, evil face. Yet when I hit, it was not upon his body, but upon the hard clay of the cistern's bottom. It was as though he had disappeared in the split-second before I struck him.

I lay there for a moment, stunned, and that moment of hesitation was all that was needed to complete my undoing. I heard a swift step behind me. A flash of blinding fire burst before my eyes. Then blackness swept over me like a stifling shroud...

WHEN I recovered consciousness it was to the realization that I was bound hand and foot and was lying in a sort of shallow tunnel. Light glared into my face from a kerosene lantern hung near my feet. The light hurt my eyes, and my head was throbbing as though it were about to split open. I closed my eyes and tried to remember what had happened.

"Barry—darling!"

I jerked my head about and saw—Betty. She was lying on the floor of what, at first sight, I took to be a small circular room which opened at the head of the cell-like chamber I was in. Then I realized that she was in the cistern proper, and that I lay in a sort of alcove which had been excavated in its side. She was lying, as I was, bound hand and foot. Her dress had been so ripped and torn that she was half-naked.

Then, in spite of myself, a shudder shook me as my gaze focused on the apparition who stood and glared down at the two of us. He was the living embodiment of an Eighteenth Century privateer as to clothing, and on his face was a maniacal snarl which might have sat on the features of Morgan, himself, as that celebrated butcher prepared to dismember a captive. And, I now saw, two legs supported him.

He grinned at me like an insane satyr—and turned toward Betty.

I heard the hissing intake of his breath as his eyes gloated on the lovely contours of my wife's body. Then he threw his huge bulk upon her fragile form and crushed her in an embrace that drew a shriek of pain from her lips.

I had been straining at my bonds with the inhuman strength of a madman, lashing my whole body about furiously in the hope of loosening even one strand. It was hopeless. The ropes of new hemp could have held an elephant.

I cursed the fiend with every breath, but he paid no more attention to me than if I had been miles away. Then, suddenly, he raised himself, got back on his feet. He came over and stood above me.

"I'm ready to go through with it," he croaked in a harsh growl. "By God, I'd like to. But there's something I want more."

He fumbled in one of his capacious pockets, produced a sheet of paper which I recognized as some sort of legal form already filled out, and a very modern-looking fountain pen.

"Sign this," he rasped, "or what you just saw will be only a sample of what I'll do to your wife."

I looked from the paper to his bloated, blood-suffused face. "What the devil is that?"

"A deed," he growled. "Never mind the questions. Sign it—"

I nodded. I would have signed away my life to gain a moment's respite for Betty—and I knew in my heart that, whatever it was, it would give her no more than that. I moved my shoulders to indicate my bound arms. "I'm no magician, even if you are. I can't sign anything this way."

He grunted, lay down the paper and pen, and stooped over me to loosen my bonds.

In that instant my eyes caught a dull gleam coming from the shadows at his back. I knew immediately what it was—the automatic Travis had given me. It had been in my hip pocket when I hurled myself into the cistern. Apparently it had fallen out and, as yet, had escaped my captor's notice.

But the weapon was a good six feet from me—and the fellow, before he loosened the rope holding my right wrist, himself produced a pistol and held it to my head.

"If you have any ideas about trying anything, just forget them now, Larch," he said harshly. "I've already killed one man—and they can't hang me more than once."

I knew that he was going to kill me, too—and Betty, after he had done with her. He didn't dare let either of us live, now. And the mad fires that lit his eyes when he looked at Betty spoke eloquently of what he intended to do to her before he granted her the release of death.

He loosened my arm and handed the pen to me, holding the gun steadily to my forehead with his right hand.

I acted instantly, the second my hand was free... The fact that he held the gun so close to my head was in my favor. I swept it aside just as he pulled the trigger, and the bullet missed me by inches. Then I caught him around the neck. Overbalanced, he crashed down on top of me. I thrust my body forward, and managed to get his rolling. Then I was able to surge erect for an instant.

But only for an instant. My tied feet tripped me, and I fell forward, flat on my face. At the same moment a gun crashed behind me, and I felt a terrific blow in my right thigh.

As I hit the ground I thrust my hand upward, and even as his bullet crashed into my flesh, my fingers closed upon the butt of the pistol I had lost—and had seen gleaming dully in the shadows of the cistern. I rolled over on my back and pulled the trigger.

A black hole, which quickly spurted red, appeared in the man's forehead. His mouth opened slackly and his eyes rolled upward. Then he crashed to the ground. At the same moment a voice came from above our heads.

"Stop firing in the name of the law!"

"All right, Travis," I yelled. "It's safe for the law to come down, now."

WHILE Travis applied a tourniquet and bandage to my leg in the bedroom of our cottage, Betty told her story. She was white and shaken with her experience, but grimly determined to reveal the satanic plot.

"His name is Copely," began Betty. "He heads a syndicate that is trying to get possession of this property. You remember that extraordinarily insistent real estate agent who tried to buy this place from us last spring—the one who finally offered us triple what it was worth?"

I did remember—and I suspected at the time the offer was made that there must be some value attached to the property which we did not know of. But we wouldn't have parted with it for ten times its assessed value.

"There is a gold-bearing quartz deposit on this land," went on Betty. "The vein runs through this old cistern. The man who dug it found lumps of what he thought was merely unusual-looking rock. He took them home with him and kept them as curios. Copely, who owns land near Fenwick, saw them one day and found out where they came from. He came here secretly and dug the test hole you were lying in, and found a rich vein. Ever since, he's been trying to get the property. Finally, in desperation, he hit on the notion of trying to scare us off. He tried to enact the old legend of Captain Home's ghost. He got a costume, daubed it with luminous paint, strapped up one leg and managed to counterfeit the old ghost's celebrated one-legged walk by means of a thin steel tube painted black, which had a broad, flat plate on the lower end. The plate made no mark on the sand, and on a fairly dark night the tube could not be seen. It looked exactly as though he were walking along without any support at all for that leg.

"But he got in deeper than he planned. When he first put on his show for me, I refused to be frightened. He appeared on the beach the second night after I got down here. But instead of screaming and fainting, I ran out to him before he could get away and began questioning him. He attacked me, then, bound me up and brought me down here. He said that you would come down, think me drowned, and immediately want to sell the property. I think, from the first, he had come to the conclusion that he would have to kill me, because he told me everything without any reservation at all. But you didn't react properly, either. You went to Fenwick and left poor Joel here. Joel attacked him on sight, before Copely had a chance to escape, and Copely killed him."

Betty shuddered, and I saw her eyes were fixed on something on the floor near the bed which I had not noticed before—a grisly looking object which Travis had brought up from the cistern. It was one of the small crescent-shaped plows from a cultivator. It would make a horrible, ghastly wound—like the wound in Joel's neck...

"But after he had killed Joel, Copely tossed all caution overboard. The die was cast—and if he got caught, any further crimes he might commit could not increase the penalty he would have to pay. He chopped off poor Joel's leg, and used it in an attempt to add color to the ghost story he was enacting. He paraded in his luminous costume, and then dove into the sea when you chased him, swam far down the shore—mostly under water—before coming out. He would come back and boast to me of what he had done—"

Betty suddenly gave way to the emotional strain which had kept her going up to now. She burst into tears and threw her arms around me as I lay there on the bed.

Travis stood up, nodded at me. "It will do her good," he murmured softly. "When you're ready, come downstairs and I'll drive you both into Fenwick. A doctor should look at that wound. Perhaps your car will be ready by the time you get there. I think you had both better go back to New York for awhile—before you start turning this place into a gold mine."

Travis had taken so long getting back because he had blown a bearing in my car, and had had to walk half of the distance to Fenwick. He had left instructions there for a crew to come out and get it, make the necessary repairs, and had driven back out in his own car.

I nodded to him and he turned and went out, closing the door softly behind him. I held Betty closer and pressed my cheek against her hair. I wondered at the courage that can repose in a fragile, defenseless body like hers. Then, for a time, I stopped thinking. Betty raised her head and pressed her lips to mine. I didn't care if the ground below us was solid gold. It couldn't have made me any happier...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.