RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

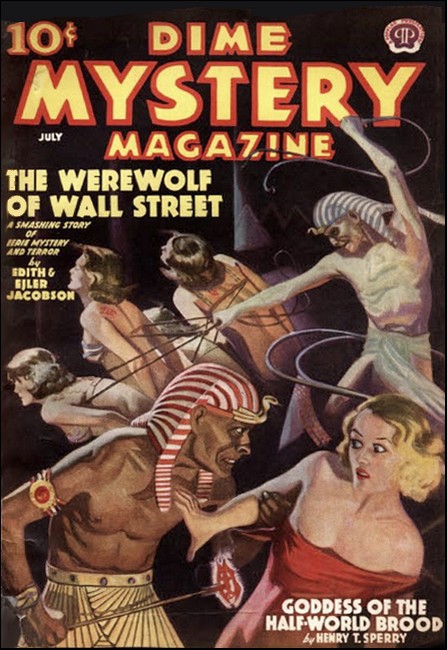

Dime Mystery Magazine, July 1938,

with "Goddess of the Half-World Brood"

This glorious woman I held in my arms: was she a dread arch-fiend, the mistress of those vicious, snarling beast-like things who now surrounded us with drooling fangs bared in dreadful anticipation of a coming feast—while I strove to fight off the spell of her weird allure?

I STILL don't know how we made it to the beach. There was a devilish undertow backing up against the coral reef, and we were swept back time after time before we suddenly found ourselves in the clear and riding a foam-edged comber into the shore.

I dragged Marion up on the sands and for awhile we stood there, while she clung to me, sobbing with exhaustion. Then we slowly started walking up the narrow strip of beach, my arm around her waist.

I kept glancing back over my shoulder at the somber wall of vegetation which loomed about us in the darkness like a huge, cupped hand. Flashes of lightning split the sky at about two-second intervals, and the ghastly white light made the tossing palm trees, the huge-leaved bananas, and hibiscus plants with their pallid, bell-like flowers seem like the hysterical inhabitants of a strange planet.

But it was the intervals between flashes which sent icy tremors vibrating up my spine; for as the blackness closed down I could see bright pinpoints of light down near the ground where the shadows were thickest—fiery sparks which occurred always in pairs, and seemed to my overwrought imagination to be pregnant with infernal, deadly significance.

The eyes of beasts, made phosphorescent by the inky darkness, undoubtedly. They would promptly retreat as we approached them. I knew that—but for some reason they aroused something like an instinctive terror in my heart.

I looked out to sea, and as the heavens cracked open with a tremendous sheet of vivid white fire, I saw the last of the gallant little yawl which had carried us almost half-way around the world. A giant comber lifted it free from the coral reef, tossed it high on its crest—and then brought it shatteringly down on its forward strakes, crushing it like an empty pecan shell, to be gulped into oblivion by the succeeding roller.

That was the last of the Marion T.

The hurricane had shipwrecked us on an island which the compilers of my admiralty charts had apparently never heard of. We'd sighted it just before the storm struck us, and, after figuring my bearings, I discovered the chart indicated a sounding of 115 fathoms in the precise spot occupied by this speck of land in the South Pacific!

The lightning showed a splintered section of the forward hatch tossing about in the surf. I waded out and secured it, broke off half of one of the split boards. It made a fairly serviceable weapon—in case those beasts in the bush were not quite as harmless as I hoped they were. Then, with an arm about Marion's slender, drenched shoulders, I started slowly toward the tropical jungle which hemmed us in.

I BATTERED a path for our stumbling feet through

dripping leaves, bushes and vines. Fortunately the

undergrowth was not as dense as it had seemed from the

beach, and soon we emerged into a practically open area

which I was surprised to see, as the lightning flamed

again, resembled a carefully cultivated park. We paused in

the middle of it, our shoulders hunched against the driving

rain, clutching each other like lost children—and

again I felt a tremor of weird foreboding race up my

spine.

We were completely encircled, now, by those eerily luminous eyes. As we stood there I counted twelve pairs of them ranged almost symmetrically about us. Marion squeezed against me.

"Don't be afraid of them," I howled above the clamor of the tempest. "They're harmless. Wild dogs, maybe—"

But I knew that was ridiculous. These oceanic islands are almost completely without animals, having been so long separated from the continents that all fauna except birds, bats, and sometimes reptiles, have long since become extinct. The animals that are found are descendents of imported beasts. It was unlikely that anyone had imported dogs to an uncharted isle in mid-Pacific.

Still—something was there; and my nerves got a shock as I suddenly realized that the only reason I had mentioned the possibility of their being dogs was because the eyes seemed to be about dog-distance above the ground. Actually they looked much more like human than canine eyes!

My imagination was beginning to take a dangerous turn. I cursed myself, and holding Marion closer, forged straight ahead across the clearing toward the pair of eyes opposite. They disappeared before we had come within ten feet of them—and the lightning showed a well-made gravel path where they had been!

"Oh look, Jim—a path!" Marion exclaimed. "The island's inhabited!"

But I couldn't share her joy. For some reason I felt mysteriously reluctant to meet the tenants of this lost, unknown islet; but I followed her as she slipped from under my arm, grasped my hand and began running ahead.

A minute or so later we saw the yellow gleam of a lamp through the foliage, and shortly after that we came to the end of the path and found a rambling but well-made two-story cottage of bamboo standing in a large clearing.

In what appeared to be the living room of the place a single lamp glowed; the rest of the house was in stygian darkness. We stumbled up the steps onto the verandah, and I pounded resoundingly on the door of solid oak paneling.

There was no response. I tried again, and still the silence of the place held, save for the steady drumming of rain on the roof. I glanced back into the darkness from which we had emerged. The twelve things which had stalked us through the forest were there, in a semicircle thirty feet from the porch steps, their human-appearing, luminous eyes glaring at us steadily as though in cold, emotionless curiosity. And now, as the lightning hissed again, I got a flashing impression of the bodies behind those eyes—humped, hairy masses without recognizable contour; but with the same sort of indefinable humanness as their eyes possessed.

I hurled my club at them and turned back to the door. I tried the latch and the door swung open.

"Come on," I said, and pulled her in.

"Jim, do you think we ought to do this—" she began. And then she screamed, horribly.

She clutched my arm in a frenzy of terror, and I saw it, too.

It was in the center of the floor—a thing which a short time ago had been a human body. Now it was an all but unrecognizable mass of bloody, torn flesh; exposed, mangled viscera, and gleaming bones.

QUICKLY I turned Marion about. Guiding her around two

sides of the room I forced her into a chair on the far

side, where a table blocked her view of the thing. Then I

yanked a batik covering from the table and threw it over

the mess. I saw the body was that of a native, probably

a Negrito, from what remained of the face. The covering

immediately became blotched with the blood which seeped

through it.

I looked around, weighing in my brain the advisability of searching the house in the hope of finding a key to this grisly mystery—and decided against it. Marion would be in danger of hysterics if I left her alone with that gruesome corpse. I went over and put an arm around her shaking shoulders.

"Brace up, sweetheart," I murmured, and she made an effort to control her sobbing. Poor girl, plucky as the devil most of the time, her nerves had given way under the tragedy of losing our gallant little boat. And now—this...

I heard the door open softly behind me, and whirled. I found myself staring into the barrel of a large-caliber pistol held unwaveringly on my midriff by a deeply tanned young man of about my own age.

"Put up your hands," he said.

I did so promptly, and then he saw Marion. His gun half-lowered, and his eyes came back to me. "What are you doing in my house—and how did you get here?" he asked.

"We got here by being shipwrecked on the coral reef at the north end of the island," I said. "We found a path which led to your house. We were unable to rouse anyone, so I tried the door, found it unlocked, and came in. There is a dead man lying there on the floor—"

He said, "Quite," and thrust his pistol back into its holster. He came toward us, skirting the corpse without giving it a glance, and stopped in front of us.

"Forgive my inhospitable gesture," he went on. "Since no one has landed here during the past ten years, I was naturally startled." He held out a tanned hand. "My name is Richard Wanderleigh."

I took his hand. "Mine is James Towne. This is my wife."

Wanderleigh stared at Marion an unnecessarily long time, it seemed to me, before he bowed and murmured some banal acknowledgement of the introduction. Only then did I realize that the girl might as well have been naked for all the protection her gown afforded her. A sheer silk one-piece dress, it was all she could stand aboard ship in those latitudes, and she wore nothing at all beneath it, the sandals on her feet being her only other articles of clothing. Now, drenched by the seas we had fought through, it clung to her deliriously rounded, slender body like a coat of paint.

"If you have any dry clothing for my wife—" I suggested—"a pair of ducks and a shirt, perhaps—"

Wanderleigh smiled. "I can do better than that. My sister would be delighted to loan Mrs. Towne a frock. Come with me, please."

He picked up a lamp from the table, lit it, and led the way into a corridor that opened off the living room. Wanderleigh, himself, was dressed in white shorts and shirt, and carried a pith helmet, all of which were dripping wet. What had he been doing out in this storm—while a mangled body, to which, as yet, he had made no reference, lay in his living room?

Apparently his sister was not at home. He entered her room without knocking, opened a closet door, revealing a number of dresses.

"You are welcome to any of these frocks, Mrs. Towne," he said, and again his brilliant black eyes clung to the contours of her figure in a manner that began to make me see red. "We will await you in the living room."

We went back to the front of the house and Wanderleigh, for the first time, looked down at the corpse on the floor.

"Poor Nara," he murmured. "They got him at last—just like the rest."

"A native of the island?" I asked. "I was wondering what frightful thing had happened to him."

Wanderleigh looked at me with a strangely calculating expression in his eyes. "This island has no natives," he said after a moment. "It's been in existence only about fifteen years. Volcanic, you know. We, too, were shipwrecked with a baker's dozen of a crew. I had chartered a junk to take us from Rapa Island to the Marquesas where we hoped to catch a liner for England. Judging from the size of the largest trees, the island had been in existence about five years at that time. The south end is riddled with lava pits, boiling soda pools, and is covered with pumice and volcanic ash. How there happened to be fertile soil on this end, God only knows. Probably the island has emerged above the surface of the ocean intermittently for millions of years."

I nodded. "It certainly didn't appear on my charts," I said. "That seems strange, too, since they are supposed to be revised every year."

Wanderleigh shrugged. "They're revised with respect to the main maritime routes. It would take the entire British fleet five years to make a complete geodetic survey of the two million square miles occupied by the South Pacific archipelagos... But here—lend me a hand with this fellow, will you? Too bad your wife had to see the mess..."

THE body was in a condition which made it difficult to pick up in one piece. In the end we gathered the grisly cadaver in the covering I had thrown over it and carried it outside.

It had stopped raining, and with that characteristic abruptness of tropical storms, the clouds were clearing away and the moon was beginning to edge out of the hurricane wrack. At Wanderleigh's direction we carried the body about half a mile below the house and left it on a small grass-tufted hummock.

"Burials are impossible here," he explained. "The earth is only eighteen inches deep. Below that there is soft rock which the tree roots grow into and somehow find nourishment. Anyway, the jackals would dig up anything you buried—and they dispose of it all the more quickly if you leave it top-side where they can get at it without any trouble."

I shuddered in spite of myself as we left our gruesome burden on the mound. I turned and looked back before we had gone more than a dozen yards—and already those twin, glowing beacons were beginning to appear in the undergrowth near the cadaver.

"But how did the jackals get here, if—"

Wanderleigh cleared his throat. "As a matter of fact," he said with queer hesitancy, "I don't know what they are. They look something like jackals—and also like something else. I have a theory that some zoological expedition was wrecked on this island before we were, and that these beasts, picked up God knows where, are the only survivors..."

It was obvious to me that Wanderleigh had no faith whatever in his alleged "theory"—but somehow I didn't feel like pressing the matter. Instead, I changed the subject.

"I hope I'm not being unduly inquisitive," I said, "but I was wondering where your sister is. Isn't it dangerous for her to be out—with these beasts on the prowl?"

"Oh, they never attack you—unless you're asleep or dead," Wanderleigh explained carelessly. "Apparently they caught Nara snoozing on the verandah. I dragged him inside and went gunning for the beggars. I still have a few bullets left, but ordinarily I hate to use them on the beasts. They're extraordinarily hard to hit, and as they become more numerous—"

He stopped suddenly, biting off the last of his sentence as if he had said too much. I looked at him and noticed how white and drawn his face looked. But perhaps that was only the effect of the moonlight.

"More numerous'?" I echoed. "Then they have been multiplying since they landed here?"

Wanderleigh laughed shortly. "Yes," he muttered, "I guess you would call it that... But you were asking about my sister. She went out, too—east, while I went west. She should be back soon..."

He hesitated a minute, and then went on. "And while we are on the subject, I may as well prepare you for Sicily—my sister. She is—well, rather a strange girl. Don't put too much faith in the things she may tell you. I'm afraid that our enforced isolation has had an unfortunate effect on her mind, and she is beginning to have strange fancies..."

"What a pity," I murmured. "But probably when you get her back to civilization again—"

I left the sentence unfinished, as we had reached the front door—and at my words Wanderleigh turned suddenly and looked at me for a moment in silence, while a faint smile curved the thin lips beneath his short, black mustache.

"Oh—quite!" he said at last, with unmistakable sarcasm in his tone. Then he opened the door and ushered me into the living room with a slight bow.

MARION had put on a plain blue dress and looked

fresh and relaxed. The recuperative powers of women are

marvelous—especially when they are given the chance

to don fresh clothing.

"Hello," she greeted us. "I'm—I'm glad you're back." I felt that she carefully avoided looking at the bloodstains on the carpet.

Wanderleigh smiled at her. "You look charming, Mrs. Towne."

"I hope your sister doesn't mind," she said.

Wanderleigh's smile became a bit twisted. "As a matter of fact, she has peculiar ideas regarding her costumes, nowadays," he murmured. "I have just been warning your husband, Mrs. Towne, that my sister has developed a few odd idiosyncrasies during the past few years. This utter isolation, you know—"

"Oh!" murmured Marion, "I'm so sorry—"

She was interrupted by an infernal clamor which suddenly arose apparently just outside the cottage. The next instant the front door burst open to admit the slender, sun-browned figure of a girl, clad solely in a sort of brassiere and girdle of what I took at first to be white fur—but which I subsequently learned was made of the breasts of small white birds, cured and cleverly stitched together. The girl carried a long leather whip in one hand. She whirled about and slammed the door shut, falling back against it as though to brace it against the attack of some pursuer—and an unearthly howl arose outside.

"Damn you, Dick," she began, "you fed them that—" and then she noticed Marion and me for the first time, and fell suddenly silent.

"We have visitors, my dear," purred Wanderleigh. "Mr. and Mrs. Towne. They have been making a world cruise on their yawl, which unfortunately came to grief on the coral this evening."

The girl had a wild, indescribable beauty. Taller than Marion, she was as exquisitely, if more voluptuously, formed. The outside corners of her dark eyes had an upward tilt which gave her a slightly Oriental appearance. The tips of her small ears, exposed by her tossed-back, raven hair, came almost to a point—like a faun's. Her full breasts, only half-covered by the downy bandeau, rose and fell with the violence of her breathing.

The girl's eyes widened as she stared at us for several moments in silence. Then, "Oh, my God!" she murmured in a low, husky voice. "Two more..."

"My dear!" put in Wanderleigh quickly. "Calm yourself. They're quite safe, as you see."

But somehow his remark seemed hardly appropriate to her exclamation. She turned on him suddenly.

"They're not safe!" she cried. "None of us is safe—not after the shrouds have eaten human flesh. I can't handle them any more. God only knows if I ever will be able to, now. Why did you do it? You knew I pulled Nara's body inside the house so they wouldn't scent him and come—you knew that. But the minute my back was turned you took him out where they could get at him. You've ruined them, Oh, damn you!"

The girl's voice broke on a sob. Then suddenly she wheeled, jerked the door open again. She sprang outside and slammed the door shut behind her.

Involuntarily I started forward and Marion jumped from her chair with a startled cry.

Wanderleigh calmly stepped in front of me with his hand uplifted. "See here," I protested, "we can't let her go out there with those beasts—"

"Heavens, no!" exclaimed Marion. "Do go out and get her—please—"

"It's quite all right," said Wanderleigh in a soothing voice. "Please don't worry about her for a moment. She always acts like this when one of the men has been attacked—or died and been eaten by the things. The poor child has formed a strange affection for the beasts and refuses to believe that they have ever attacked a human being. She would much prefer to believe that I had killed them all. And strangely enough, the things seem to reciprocate her feeling for them. Ordinarily they fawn upon her like big dogs, and obey her with an intelligence that is weirdly human—although they always become a bit intractable after they have—dined—as they have tonight."

"Good heavens!" breathed Marion, and sank back in her chair.

SOMETHING in Wanderleigh's attitude told me that he

would resist with physical force any persistence in my

attempt to get out to the girl. Not wanting to precipitate

a crisis unless it were really necessary, I went to a

window and looked out.

In the moonlight, in front of the house, a strange scene was being enacted. The girl stood in the center of a ring of cringing beasts—the animals she had called "shrouds." They had stopped their infernal howling, but now and then one of them would turn toward the house, as though about to slink off toward it. At that her whip would flick out, and the animal would jump back toward her, whining, with its tail between its legs. She seemed to be talking to them, and gradually they quieted down entirely, squatting or lying in a ring around her, as if listening intently to her words.

For the first time I had a good view of the beasts, and I could understand both Wanderleigh's reference to them as jackals, and his reluctance to insist on such a designation for them. Actually they were much larger than any jackal, and their bodies were thicker in proportion to: their length, especially across the shoulders. Their heads, although terminating in a typically pointed jackal snout, were wider across the cheek bones, and deeper from cranium to jaw. On the whole they resembled what might result if an ape were successfully crossed with a wolf.

As I watched the weird tableau, the term the girl had applied to them again crossed my mind. Shrouds. Shrouds are the clothing of dead men. Why did she call them that? I have often wished I had never learned...

The next morning Marion was too listless and drowsy to get up, but the heat drove me from bed early. As no one else seemed to be about, I made myself a cup of tea—which Wanderleigh, I learned, had succeeded in cultivating on the island—and went for a stroll, heading for the south where my host had said the volcanic formations were.

Naturally, the island looked entirely different than it had during the night and the storm. It was a riot of color and light—but somehow its air of other-worldliness, its mysterious faculty of seeming a bit of land from some strange planet, remained. This island harbored some dark secret, of which I had no hint, as yet. I knew that, and itched to get at the root of the puzzle as soon as possible. I swore to myself that I would.

It was one of those resolutions, cheerfully and easily made, with which we bolster our egos when confronted with an enigma. But a wiser, more intuitive part of my brain was whispering that I would be happier if I curbed my curiosity. Naturally, I disregarded that...

My mind was full of the weird spectacle I had witnessed last night in the moonlit dooryard of the house—Sicily Wanderleigh taming her fearsome shrouds—when suddenly I rounded a huge volcanic boulder and came upon the actors in that strange drama.

The same actors—but an entirely different scene, this time. Sicily lay stretched in the sun, lying on a little green hummock, while one of her ugly pets dozed with its shaggy head resting on her bronzed right thigh. The rest cavorted about like ungainly puppies at play, wrestling, rolling on the ground and chasing each other about. Sicily's dark head rested on her clasped hands and she would have appeared asleep, except that she was humming a strange, wild tune which rose and fell on the still morning air like the sound of a distant brook murmuring over pebbles and treet roots.

IT was only a moment before the nearest shroud saw me. He leaped to his feet and came stalking stiffly toward me, while a savage growl rose from deep in his throat. I thought of the condition in which we had found Nara's body, and tensed my muscles. But at the sound of the animal's growl, Sicily looked up, then got to her feet. She called out sharply to the beast which was making for me, and the thing slowed to a halt; then with seeming reluctance turned about and went back toward her.

"Come on," she said to me, "they won't bother you."

But I kept a vigilant eye on the beasts as I advanced. They had closed in around her in an attitude of protection, and there was a gleam of unmistakable venomousness in their eyes which did nothing to strengthen my faith in their harmlessness. I realized that just one of them could, if he wished, make mince-meat of an unarmed man in considerably less than a minute. Their paws were armed with claws as big as a grizzly's, and the huge canine fangs which showed beneath their lower jaws looked as though they could have ripped my throat with a single slash.

Apparently sensing my distrust of her pets, Sicily turned and spoke a few words to them in an authoritative tone, and as I drew nearer they slowly slunk off into the jungle of greenery at the foot of the hummock, casting baleful glances back at me over their shoulders.

Sicily resumed her former position on the ground and motioned for me to sit down beside her.

"Do you like our island?" she asked carelessly.

"It's very attractive," I said without a great deal of enthusiasm.

"I hope you will learn to like it very much—because you will probably be here for a long time. Unless, of course, the sea suddenly decides to swallow it up again."

"I suppose there is always a chance of that."

Sicily's slender, all but naked body rippled into action as she restlessly rose to a sitting posture and clasped her arms about her knees. She was silent for several moments, gazing abstractedly off into the bush where the shrouds had disappeared.

"There's a much worse danger than that," she said finally. "My brother. You must watch him."

I looked at her quickly. "Would you mind explaining?"

She turned the perfect oval of her face toward me, and I saw that her strange, tilted eyes held plumbless depths of tragedy.

"He has already killed thirteen men," she said in a low voice, "and for years has been trying to drive me insane. Sometimes I think he has succeeded."

"Good God'! Are you sure he murdered all those men?"

She nodded, and her eyes again sought the jungle. "We left England in Dick's schooner twelve years ago, when I was sixteen. We shipped with a crew of twelve men. You will be safer if I don't tell you the purpose of our voyage. Finally we got to Tuamotu and picked up Nara, the Negrito boy, as a general roustabout. Dick didn't kill him until yesterday because he has been useful about the place. We got caught in a hurricane, and a water-spout flung our ship on the reef. We all landed safely and managed to salvage practically all the ship's gear and stores, as well as the—the thing we had come down here for. Then it began—the killings, I mean.

"First Chips, the carpenter, died. That is, he disappeared. The next day, two of the seamen were missing. Then the cabin boy, the cook, and the quartermaster. All but Nara were gone inside of two months. And there was never a sign of what happened to them. But as they disappeared, the shrouds began to be noticed. It seemed that as the number of men decreased, the shrouds became more numerous. A terrible superstition grew out of that—and the last men to disappear were sure that some weird magic of the island was turning them into beasts. Then Anderson, the mate, died in horrible agony. He was poisoned, I think. The rest were probably thrown into the lava pits. He was the only one I saw actually die—and he was the last of the white men..."

She paused a long time, and when she spoke again her voice was so low as to be almost inaudible. "He said that all the men had been secretly in love with me, and that I had known it. He accused me of being a witch—of turning them into beasts. He cursed me and called me—Circe..."

CIRCE—the siren of ancient Greek mythology who

changed her lovers into wolves and lions; who transformed

the followers of Odysseus into swine... I wanted to smile

at this idea of a modern reincarnation of the ancient

fraud—but somehow I couldn't.

"Actually, you think it was your brother who killed these men? But what reason could he have had?"

"One of the best reasons in the world," she said, getting lithely to her feet. "But I don't intend to tell you what it was. Not yet, at any rate."

She started to walk off in the direction the shrouds had taken. Then she suddenly stopped and turned around.

"Was there anything salvaged from your ship?" she asked.

I shook my head. "Not a thing but ourselves."

"You had a sextant aboard, of course. It might have been washed over the reef and come ashore?"

"It's possible, naturally. I haven't been down to the beach yet."

"Dick has," she said. "I saw him wade out and get a box about a foot square and eight inches deep. Could that have been the sextant?"

"It's quite possible. I kept it in a walnut box about that size."

Sicily bit her lip and seemed on the point of saying something else. Then, apparently, she changed her mind, turned back toward the jungle and walked into it swiftly, disappearing without a backward glance. I heard a few muted, animal yelps and the sound of several bodies moving about in the undergrowth. Then the slight rustlings died away in the distance and I was left alone in the silence of the tropical morning...

The first tremors began as I was walking back to the house after my strange talk with Sicily. They brought me to a standstill with my heart in my mouth. It wouldn't take much of an earthquake to wipe an island of this size out of existence—and we were helplessly marooned on it, hundreds of miles from the next island and thousands of miles from civilization.

A muffled boom sounded faintly behind me, and I whirled about in time to see a column of black smoke ascend rapidly into the sky, and then mushroom out into a gigantic black flower over the southern end of the island.

I started for the house at a dead run—and hadn't taken a dozen strides when the world seemed to move sideways under my feet and I was thrown to the ground with stunning force. As I got to my feet, the sound of low rumblings came, apparently from deep in the earth, and another explosion boomed out behind me.

I knew, from past experience with volcanic earthquakes, that this was going to be a serious one. The shocks were coming at two—or three-second intervals and rapidly increasing in force. I fell a half-dozen times before I finally reached the house, which was still intact, and burst in at the front door. I shouted Marion's name at the top of my voice—and received no answer. I dashed upstairs to the bedroom we had occupied—and found it empty. I was about to leave, when I noticed a thing which brought me to a breathless halt on the doorsill.

Marion's clothes were still neatly piled on the back of a chair, as she had left them the night before. The bed was a riot of disordered blankets and sheets—and beside it, on the floor, lay the nightgown which she had borrowed from Sicily's supply. It was ripped from neck to hem!

The severest shock of all came, then, and I had to hold onto the jamb to keep from being thrown to the floor. The house swayed as though in a high wind, and joists cracked like fireworks. I staggered down the stairs, and suddenly the beams supporting the ceiling gave way. The walls swayed inward. The staircase behind me collapsed and I had just time to get out of the door when the house folded up like a paper bag and crashed to the ground.

It had not been more than five minutes since the first quake, but already the skies were becoming overcast, a wind was coming up, bending the palm trees and scattering a shower of ashes and pumice from the exploding volcano all over the island. I stood looking at the ruins of the house for a few stupefied moments, trying to decide what direction to take in my search for Marion, but I had not the faintest clue to work on. I shouted her name repeatedly, but the noise of the wind and the approaching cataclysm made my yells all but inaudible even to my own ringing ears.

I was frantic with indecision, but at last I decided on a plan. Having no idea of where to look for Marion, the best thing I could do would be to start a systematic search of the entire island. God only knew if it would remain above the surface of the ocean long enough for me to cover half of the territory which would have to be explored, but it was the only course of action that seemed to have the slightest chance of bringing success.

I plunged directly into the jungle, heading east from the house, intending to keep on until I reached the beach on that side of the island, then make a circuit of the north end and work back south, crisscrossing through the brush. It was clear enough that Wanderleigh had kidnapped Marion, and I cursed my negligence in leaving her unguarded in the house of a homicidal maniac—but of course, I hadn't any idea of what he really was when I left the place that morning.

AS I fought my way through the jungle the shocks continued with gradually increasing force, and the wind rose steadily. The thicket was in an uproar, with bats, stirred from their daylight slumbers, fluttering about blindly in the tree-tops. Time and again I was thrown to the ground, or forced to cling to a swaying tree trunk as terrific shocks shook the island. Already I could hear the accelerating beat of the surf, licking ferociously at the shoreline as if in eagerness to beat it into oblivion.

Then simultaneously I emerged into a small clearing, and the shocks subsided. This, I knew, would probably be no more than a brief intermission, and I could expect even more violent tremors to follow it. But it gave me a chance to get my bearings.

I was about to strike off through the other side of the clearing, when suddenly one of the shrouds appeared directly in my path. The beast came to a halt and sat back on its haunches, regarding me gravely for a moment. Then it turned to the right and began to walk off. I started on in my original direction—and instantly the shroud turned about and came running after me. I whirled to protect myself, expecting an attack, but the beast merely turned again and started off in the direction it had first taken, halting, after a few steps, to look back at me.

As plainly as though it had spoken, I saw that it wanted me to follow it. I played a hunch, then, and walked over to it. The animal immediately sprang into the bush, with me close behind it.

Straight to the south, the shroud led me, through jungle, across occasional open spaces and over rocky, black outcroppings. We skirted a small lake which had been formed within the past few minutes when a landslide had dammed off a creek, and presently reached the foot of a rugged, black escarpment at the foot of which stood Sicily and the rest of her ferocious looking pets.

"Hello," she greeted me calmly. "Do you think this is the end?"

"I'm not sure," I said, "but I'm afraid it is. We'll know—if we're still alive—within a half-hour or so. Have you seen Marion—my wife?"

She looked at me for a long time without speaking. Then at last, "You love her very much, don't you?" she asked quietly.

"Yes, of course."

"You would like to return with her to—the outside?"

I laughed shortly. "There's a fine chance of that! But naturally I would like to be near her when this speck of land begins to slide into the sea."

She fell silent again, gazing at me with her weirdly beautiful eyes—and there was something in her expression which began to make me feel vaguely uneasy. Then suddenly she came up to me and slipped her brown, rounded arms about my neck.

"Listen," she said, "I have never known what love is. I have always been afraid, of it. My brother—and the men who died—they have made it seem a horrible, nightmarish thing. My brother knew what those men thought—he knew of their belief that I was a witch, a Circe who changed men into beasts. He has pretended to believe that, himself, all these years. He wanted to convince me that it was true—to drive me mad. He doesn't dare kill me, as he killed those men, for he knows that the shrouds would tear him to pieces. He found a treasure, before we were shipwrecked, and he wants it all to himself. He has built a boat—he thought secretly, but I came upon him many times unsuspected, and saw him at work on it. He needed only a sextant to guide him over the ocean—and now he has that. The one that was on your ship. He is ready to sail—and he is taking your wife with him—"

I cursed aloud and grasped the girl's wrists. "Damn his soul! Where are they. Tell me!"

I took her by her slender shoulders and shook her violently. She looked up at me with a sad, slow smile, then she gently freed herself from my grip. The shrouds had growled menacingly as I shook her, and now they closed in about us, looking up at me with baleful lights in their eyes and showing their fangs in savage snarls.

"I'll tell you," she said. "You know I'll tell you."

<BUT she didn't, for a moment. She stood before me with her eyes upon the ground at her feet, her young breast rising and falling swiftly. Then suddenly she turned around, so that her smooth back was toward me, and said in a barely audible voice, "Come."

The pack of shrouds sprang ahead of her, leading the way up a narrow trail which ran along the escarpment, and I followed, silently raging at the slowness of the pace. Would we get to this boat of Wanderleigh's before he had time to weigh anchor?

The path ascended steeply for awhile, then suddenly broadened out into a wide ledge. In the side of the cliff a narrow cleft showed a faint yellow light. Our weird cavalcade came to a stop, and Sicily pointed into the cleft.

"In there," she said.

I brushed past her, abrupt in my eagerness, and entered the crevice—only to come to a startled halt as an eerily beautiful sight met my eyes. Beneath my feet, a narrow path fell steeply away to a little lagoon enclosed in a vaulted cavern at the far end of which daylight showed faintly. Tossing on the agitated surface of the lagoon was a tiny, queerly shaped boat bearing a single mast rigged with a small gaff-mainsail and jig, both of which had been sheeted home and hung flapping listlessly. Two lanterns stood on boulders near the water illuminating the scene—and now from behind the rock which supported them came a man, his arms loaded with objects which I could not distinguish clearly from that distance. I started to descend cautiously.

Wanderleigh deposited his burden on the cambered deck of his curiously constructed boat, and again disappeared behind the boulder. By the time he reappeared I had reached the bottom of the path and was waiting for him. His arms supported a large crate which he immediately dropped as he saw me.

"Where's my wife, damn you!" I said.

Instead of answering, he snatched the pistol which hung at his right side, snapped it up and fired. The bullet struck me in the right shoulder and flung me back against the boulder. He fired again, but missed, near as he was to me. He had time to pull the trigger once more, before I was on him, but the hammer clicked harmlessly on an empty chamber.

He slashed at me with the revolver butt as I closed with him, laying open the scalp over my right eye for several inches. We crashed to earth, with me on top. I had only my weight to hold him, as my right arm was useless. I swung at his jaw with my left, but missed as he dodged, and caught him in the right temple, instead.

Wanderleigh screamed like a woman. He tried to fling himself sideways, and struck at me again with the butt of his pistol, hitting me in my wounded shoulder. The pain made lights dance crazily in front of my eyes, and I knew that if I didn't get him within the next few seconds he would have me licked.

With an effort which nearly cost me consciousness, I managed to force my right arm into a position where I could clutch his hair with my hand, then once more I swung my left fist. This time I connected squarely with his jaw, and felt his body go limp beneath me.

I sprang up and staggered to the boat, which floated flush against the rocky ledge of the shore in deep water. I pulled myself aboard and descended a companionway leading down into the cabin. There, bound hand and foot, lay Marion on a bunk. She cried out joyfully as she recognized me, and I began fumbling with the ropes about her ankles.

"Darling—are you hurt badly? Let me—"

"No. He got me in the shoulder—missed the bones, I think. Cut my scalp a little."

I HAD her free in a couple of minutes, and she

insisted on bandaging me up with some gauze we found in a

foot-locker.

"You stay here," I said when she had finished. "I've got to go back and get that girl and Wanderleigh. We'll keep him tied up until we make a port—then I'm going to bring murder charges against him. Tell you about it later." I ran up the companion—and came to a shocked halt as I hit the deck.

Instead of the unconscious man I had left on the shore, there was now a gruesome, bloody corpse—such a corpse as Marion and I had found the night before lying in the middle of the Wanderleighs' living room. While I was below the shrouds had come down here and...

There was no sign of the beasts, now. They had done their bloody work and disappeared. I seized the cadaver by one ankle and hauled it behind the boulder where it would be out of sight when I brought Sicily down. Then I started back up the trail.

As I reached the opening to the grotto, the second series of tremors began. I hesitated for a moment. Was I justified in risking Marion's safety by not putting to sea immediately? Then I caught sight of Sicily down below in the ravine. I shouted to her, and began running down the path.

She stood in the midst of her beasts waiting for me, the animals milling restlessly about her.

"Come on, Sicily," I said. "We're really in for it, this time. This island may blow itself apart any minute—"

She shook her head and put her hands behind her back as I reached for a wrist. "No," she said. "I'm going to stay here."

"Damn it, you can't stay here. I tell you the island's going under. You'll be blown up or drowned—"

She shook her head again. The tremors began to come more rapidly and increase in strength. I decided there was no more time to waste on words. I grabbed her and swung her up in my arms, turned to start back up the trail.

Instantly the shrouds leaped for me. One grabbed the heel of my boot and nearly threw me. The rest blocked my path, growling savagely.

"Sicily, call off those brutes!" I demanded. "We've got to get out of here."

She smiled up at me faintly and shook her head again. "They won't let me go," she said. "You might as well put me down."

Another shock hit the island, and I fell to my knees, still holding Sicily. But she immediately struggled out of my grasp. I got to my feet and lifted her up.

"Good-bye," she murmured and slipped her arms about my neck. Her lips met mine and clung. I held her smooth, slender body close for a long moment. Then she broke away from me and fled down the ravine, followed by her beast pack. She stopped for a moment as she reached the entrance. She turned and waved briefly, then quickly disappeared around the wall of the escarpment. With a wild, bitter emotion I dared not name raging in my heart, I turned and made my way laboriously back up the path...

The little boat stood out to sea in a quartering, puffy wind. The waves were high and broken, as in a circling storm, and giant peaks of water would suddenly pile up without warning and threaten to swamp us. I pulled in as close to the wind as I dared, striving to pull directly away from the land—which was, of course, the chief source of danger.

Within the past five minutes a great cone had arisen at the extreme southern tip of the island, and from its mouth there belched a solid column of fire which lit the sea for miles with a weird, infernal glow. It was necessary to skirt that end on the first tack, and it brought us closer than was comfortable to the flaming cone. I kept a narrow watch on it—and that was how I happened to witness the ghastly drama which took place on the blackened hillock to the right of it.

FROM the glimpse I had caught of it while on the path

leading up the face of the escarpment I knew that it was

no true hillock, but the side of a small crater, in the

center of which raged and tossed a lake of boiling lava.

The molten rock cast an eerie green and yellow light

upwards, which illuminated several figures standing along

its western rim. I called Marion to take the wheel and

turned my whole attention to that group on the lip of the

crater.

The distance was great, but I knew that it was Sicily—and twelve other beings—who stood there, etched by the weird light into high relief against the smoke-curtained sky. But a curious change had taken place—so that I could not be sure that my eyes were not playing tricks.

As I watched I felt an icy hand closing about my heart, and unconsciously my arm rose in a gesture of protest against what I sensed was about to happen—what I sensed was inevitable.

The girl's arms raised slowly above her head, and she stood poised there for a minute, her nude, slender form painted in shimmering greens and yellows by the sulphurous flames below her. Then, suddenly, her body arced forward—and launched into space!

A small geyser of flaming lava sprang into view—and subsided. I covered my eyes with my hand for a moment, and when I looked again I saw Sicily's twelve weird companions plunge downward. And in that next instant, twelve small geysers leaped up...

It was many moments before I had the strength to go back to the wheel; and when I did, Marion, whose intense preoccupation with the handling of the ship had mercifully saved her from witnessing what I had just seen, looked at me with anxiety written on her face.

"What is it, Jim?" she said. "Don't you think we have a chance?"

"Go below, Marion," I muttered. "Make everything fast. We've got a chance—but things are going to happen. And damned soon, too!"

As if to verify that, a terrific rumbling arose, seemingly from the very bottom of the sea, and a huge wall of water rose off our port bow. Quickly I lashed the wheel and lowered the mainsail, furling it on the boom. Then I went forward and took in the jib. Next I freed all the stays and sheets, unstepped the small mast. Wanderleigh had built a couple of supports fitted with straps, and I hoisted the mast onto these, so that it lay along the deck on the port side. I buckled the heavy straps over the mast and went back to the wheel.

Wanderleigh had built his little boat well—for the purpose he had had in mind. It was completely turtle-decked, and with the hatch battened down, would be as streamlined as a submarine about to submerge. And that, as he had foreseen, was precisely what it was going to do, if the island sank.

The wind now appeared to be coming from every direction at once, and I couldn't tell whether we were bearing down on the island, or going away from it. But enough was occurring on the island, itself, to drive consideration of everything else out of my mind. For a moment I forgot about the boat.

Suddenly the crater-lake into which Sicily and her followers had disappeared, boiled over. At the same moment, the new cone next to it emitted a blast of fire, steam and smoke which seemed to cover the whole sky—and a tremendous, livid crack appeared in its side, out of which poured a torrent of flaming lava.

The air quivered with terrific detonations—and abruptly a portion of the island's surface, at least five acres in extent, leaped into the air, propelled by a torrential column of billowing steam and lava.

The end was approaching. I went below and battened down the hatch. I lay down on the bunk beside Marion and used the leather thongs attached to it to strap us in. If we were still living at the end of the next few minutes, we would be safe...

BUT it was nearly an hour before I dared venture above-decks. In that time the ship had tossed madly, gone on her beams' ends, and turned completely over more than once. But she had lived, never breaching a seam or shipping a pint of water. And the mast was still in its brackets when I came on deck. In fact, I could find no part of the little craft that had not withstood the fury of the tormented sea.

All signs of the island had disappeared, except, in the distance, some floating wreckage—perhaps up-rooted trees or other refuse of the cataclysm. The seas were still high, and faint rumblings came from deep beneath the boat at wide-spaced intervals. I stepped in the mast and sheeted home the jib. The wind had steadied, but it was still too strong to risk hoisting the mainsail. I sat at the wheel, and looked back over my shoulder at that floating stuff far astern.

I cannot tell you all the thoughts that came to me, then—but this I will tell you; and you may believe or not, just as you wish:

I said, before, that after Sicily had leaped to oblivion in that lake of boiling lava, her companions had cast themselves into it after her. There were twelve of them, as I have said, and they were there with her—but they were not shrouds. If some strange fantasy of my brain did not distort my vision, it was not a dozen beasts who leaped to death after their mistress...

It was twelve men...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.