RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

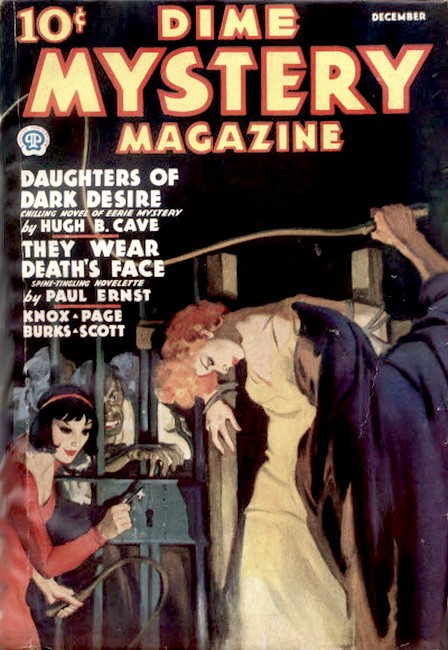

Dime Mystery Magazine, December 1936, with "Satan's Glassworks"

It was I, God help me, who sent my own beloved into the jaws of a lurid hell on Earth. And when I had done that, what else could I do but follow down the dark, dreadful path I had set her trusting feet upon—even though it meant only that I would be forced to be the helpless witness of her soul-destroying ordeal with the implacable forces of deathless terror?

IT was Tyson Vines, the firm's lawyer, who brought home to me the enormity of the mistake I had made. It was his voice, agitated and angry, that beat into my ears over the telephone with the effect of the drums of doom.

"My God, Johan!" he shouted furiously. "I can't understand you. I could hardly believe my ears when my wife told me you had allowed Jeanette to go up to the plant by herself. You know that no one is supposed to go into the plant during these close-down periods. I don't take any more stock in these superstitious yarns the workmen babble than you do—but we both know that terrible things have happened in the past. For God's sake, run up to Ladore immediately and get her—or I'll do it myself!"

When I hung up the receiver I was trembling. Now, no more than Vines, could I understand why I had let Jeanette go up to Ladore. Of course, I had been completely engrossed in the terrific job of unraveling the mess made by my uncle's sudden and inexplicable disappearance. Jeanette, bless her heart, wanted to help—and only succeeded in making a nuisance of herself. When she found that I needed someone to inspect the laboratories and factory at Ladore she volunteered immediately—and I, stupidly unmindful of any real possibility of danger to her, had let her go...

Now old memories that had laid dormant for years swept back over my mind—tales I had heard as a boy; stories that for years had circulated about the old glassworks at Ladore. I had scarcely given them a thought after I had reached my teens and realized that they were nothing more than the fabrications of the Norwegian workmen and their families who lived up there. True, they had vaguely returned to my mind—to be immediately and impatiently rejected—at intervals of ten years. The reason why a decade separated each such renascence of the old memories was that at these intervals there always sprang up a need to shut down the works temporarily.

During my father's life-time these periods of inactivity occurred with mysterious regularity. Whether they had done so when my grandfather, the founder of the works, was running it, I was never able to determine positively. Tradition said that they did, but my father—and after his death, my uncle, who then took charge—brusquely silenced me every time I tried to draw them out regarding the old yarns. I knew why, of course: the propagation of such stories might do the firm a great deal of harm.

However, it was a matter of record that the Ladore Glassworks was first established for the manufacture of the seventy-five-inch reflector—then the largest in the world—which went into the telescope at the Haldane Observatory. It is also history that the pouring, cooling, and grinding processes took exactly ten years—over twice as long as the same job would take nowadays. But there is no authentic record that the factory closed down at the end of that time. There is only the story—the strange, incredible, word-of-mouth story of its having done so...

HJALMAR STORM, my grandfather, was an eccentric genius and a world-famous manufacturer of scientific glass equipment and precision instruments. He perfected the Guinand method of making large disks of flint glass, and advanced the optical sciences immeasurably thereby. But he was an atrociously poor manager of men, and it is known that the early history of the Ladore Glassworks was spotted by recurrent labor troubles, all of which were directly traceable to his poor judgment in the handling of his personnel.

A Norwegian who claimed descent from the great Viking kings, he was even too patriotic, and insisted that no country in the world surpassed his own in the production of heroes and mental giants. Nevertheless, he found it necessary to import a few Swedish specialists when he set up his glassworks, in order to teach his more favored Norse workmen their trade.

The story runs that while the Swedes contributed their matchless skill in handling and working glass, the Norwegians gave nothing to the development of the factory save their industry—which was tremendous—and a fabric of superstitious lore which they wove about the beginnings and evolution of the plant. Perhaps to compensate for their inferior craft and knowledge, they had revived the legends of the Old Norse gods, and invested themselves with the grandeur and dignity of the giant artisans who, according to their native mythology, accomplished stupendous feats of craftsmanship under the guidance and supervision of the great god Loki.

One of the Swedes, who must have possessed a sense of humor as well as a knowledge of Norse mythology equaling that of the Norwegians themselves, is said to have thrown them into a panic before he left by pronouncing upon them the curse of Thor the Thunderer—the greatest of their own gods, but the traditional enemy of Loki. And everything that went amiss, after that, of course, was blamed by the workmen upon this curse.

I remembered all this, that afternoon, and I remembered what was reported to have happened after that first ten-year period had expired. I remembered that on the tenth anniversary of the opening of the works men had died terribly under spates of molten glass from pots suddenly and mysteriously dumped upon them.

I recollected the story of the chief engineer who had gone mad as he watched the machinery of the factory apparently being operated by unseen hands, so that limbs were torn from living men; and other workers were abruptly and unaccountably thrust between the great steel rollers to emerge as shapeless, bloody masses of pulped flesh and broken bone.

I recalled the tale of the inspector of microscopes who was found with the barrel of the last instrument he had looked at thrust half-way of its length into his right eye, so that it penetrated deeply into his brain...

Fiction—fantasy—myth—whatever it was, it came back to me with an insupportable recrudescence of horror. And behind it was the lurking, terrible realization that ten years ago had occurred the last but one of the mysterious shutdowns—that the very last was even now in existence. And that, at this moment, the girl I loved was being exposed to unimaginable perils which, superstition-born or not, I finally became convinced were only too realistically and ominously threatening...

OLD Fridtjof Krag had been in my father's and my uncle's employ before the date of my earliest memories. Ancient, wizened, gnarled as one of the little wind-tortured trees that grow high on the steep banks of his native fjords; he had always seemed to me to be scarcely human. A gnome, a kobold in mufti and thick glasses, he was as mysterious and vaguely sinister as the age-old legends of the dark, cold country that had been his birthplace. As a child I had been afraid of him. As a young man I had acknowledged that he was the most inscrutable, secretive man I had ever known—and dismissed him from my mind.

But he recalled himself forcibly to my consciousness on the fateful afternoon of which I am writing. Full of the nebulous terrors that had surged into my brain, I was dashing through the outer office, on my way to Jeanette's side by the fastest and shortest possible route, when he stopped me dead in my tracks.

In my haste I did not even see where he came from. For all I knew he might have jumped out of the floor or materialized suddenly from the air. But there, abruptly, he was, blocking my path and peering up at me with his pale, secretive eyes which were grotesquely magnified by his heavy spectacles. We stood there a moment, staring at each other. Then, impatiently, I made a movement to brush past him.

With strange insolence he again stepped in my path, and one of his greyish-white claws of a hand gripped my forearm with amazing strength.

"Pardon, Mister Johan," he murmured, "but you must not go!"

I gasped, and a superstitious shiver coursed up my spine. Could the man read my mind? Ten minutes before I had not known, myself, that I was going to follow Jeanette to Ladore—but Krag knew it, as his next words proved.

"It iss too late, Mister Johan," he went on in his weirdly monotonous voice. "Too late to safe de yong lady. Unt if you go too, you vill die yoost like her. No longer Loki de Red protects de factory. It iss Thor—"

Roughly I grasped his thin shoulders and shook him. "What in hell are you talking about?" I shouted. "What has happened to Miss Gravesend? How did you know that anything had happened to her?"

He seemed to be unperturbed by my manhandling, although I thought I caught a strange gleam in his eye as he answered calmly, "De watchman—he called yoost now. He say he try to keep de yong lady from going in, but she go. Den, the vatchman's voice choke. He say some-ting iss killing him—unt de phone go dead. I come to tell you—unt I know from de vay you look dot you know..."

But I waited to hear no more. A quarter of a minute later I was in the driver's seat of my car, roaring out of town at a rate of speed that would doubtless mean a ticket waiting for me when I got back—if I did get back...

THE town of Ladore is situated upon a craggy hilltop overlooking the valley in which lies the Ladore Glassworks. The town is populated chiefly by artisans and laborers in the factory, most of whom, in spite of their morbid superstitions, are normally cheerful and contented with their lot. As I drove into the village, however, I sensed that the usual spirit of optimism was absent. Large groups of the citizenry were gathered at the street corners, in front of the tiny post office, and the principal "general" store. The looks they turned upon me as I drove in and stopped were full of apprehension and gloom.

I called to one of them, Hans Linger, foreman of the plate glass division, and he slowly, with seeming reluctance, walked over to the side of the car.

"Have you heard of anything happening at the works?" I shouted at him as he strolled toward me. "For God's sake, man, hurry up! Did you see Miss Gravesend drive through?"

"Ya," he muttered as he slightly quickened his pace. "You yong lady, she drive t'rough—it might be vun hour ago... But nottings hass happen—yet—"

Suddenly his guttural voice was interrupted by a wild shout coming from the far end of the street: "Look—de factory! Iss smoke from de stacks!"

Immediately there was a stampede down the main street in the direction from which the shout had come. I slammed into second speed, and reached the brow of the hill from where the factory could be seen in a matter of seconds. Once there, I kept right on, diving down the steep road to the floor of the valley with my foot pressed hard on the accelerator. For the thing I had seen fanned the glowing embers of my terror for Jeanette into raging flames: From four of the stacks of the supposedly abandoned factory smoke was pouring forth in tall, ominously significant columns.

As I swept by the watcher on the hill, I heard him wailing hysterically, "Dot Loki—he brings fire from hell for his master, Thor..."

AS I skidded to a stop in front of the watchman's sentry-house, I felt an almost palpable weight of dread bearing down upon my heart. The fearful words of old Krag tolled in my ears like a requiem for the dead: "It iss too late... too late to safe de yong lady..." and I was so weak with terror and foreboding that I could scarcely lift myself from behind the wheel.

And then, even as I did so, horror smote me—transfixed my muscles with the paralysis of the doomed. For my eyes lit on the window of the watchman's house—and I saw what was behind that window...

I had known old Pete Sars well. Many times he had taken me, as a youngster, for tours about the factory. He was proud of his job as watchman, proud of the responsibility of watching over the great factory—and his pride shone in his kindly old face. But there was neither pride nor kindliness in that face now. There was only unthinkable terror and agony—terror in the wide-spread, bulging eyes; agony in the distended mouth and twisted features. And those eyes were fastened upon me, as though it were of me that their owner was afraid!

Old Pete's face was pressed hard against the glass, his nose flattened against the pane, his mouth fixed in a gaping "O" of inexpressible suffering and fear... And then I noticed something gruesomely strange about his whole appearance that I had missed at first: His lips and cheeks were strangely discolored, and his neck—as much of it as showed—had a raw, livid look that sickened me...

Shuddering, I slowly walked toward that dreadful window—and as I did so old Pete's eyes seemed to go out of focus, so that he appeared to be looking behind me. I knew the truth, then. Pete was dead, and had been propped up against the window so that—

No... Not propped! I was only six feet from the window when the grisly truth brought me to a trembling stop in my tracks. Something only a fiend could have conceived had been done to Pete: Molten glass had been poured down his throat; then, as the mass hardened, his face had been pressed against the window, so that the glass bulging from his mouth had annealed to the pane. Now he was held there—a corpse supported by a hideously cruel ingot that probably extended half-way down his gullet!

The work of a fiend—a devil from hell! And Jeanette had come this way—was even now, perhaps, the plaything of the infernal forces that had been loosed upon this factory...

With a cry that was half a sob of pure terror, I wrenched myself out of the spell of horror that gripped me, and dashed toward the main door of the factory—a door that was open with an invitation the ominous significance of which I missed at the time.

I leaped across the threshold and ran to the center of the great pouring room before I jerked to a sudden halt—at the sound of the door thundering closed behind me. I whirled in time to see a little eddy of dust arising from the floor, caught up by the swift passage of the door. But quick as I was, I saw no person. If human hands had closed that door, it had been done from the outside...

I was not concerned with that. Trapped I might be, but if so I was the captive of the same forces that held my sweetheart—which was what I wished. I ignored the door, and shouted Jeanette's name aloud, over and over.

There were no answers to my calls save eerie, mocking echoes...

FOR a time I stood, irresolute and panic-stricken in the middle of that vast pouring room. It seemed oddly changed since the last time I had seen it. Physically it was the same. Overhead were the travelers for the great pots. Near the far end of the room was the mold which eventually would hold the great 200-inch reflector for which the Ladore Corporation held a contract from the Wyandotte Observatory. Nearer were six of the thirty-foot plate tables with their rollers. On these were manufactured the finest silicate-of-soda plate—as pure and free from color as any in the world. And banked across the farthest wall were the electric and gas furnaces—and the four coke-burning hearths from the stacks of which had come the smoke which had amazed and terrified the villagers.

It was toward these that I now made my way. Reaching the first, I swung open the door and peered inside. No hot, glowing bed of coals met my eyes—no sign of fire of any sort. A wailing moan arose from the darkness within, like the cry of a tortured soul in hell. I slammed the door shut and looked out of the east windows. There on the ground outside the factory was the shadow of the first stack, etched by the westering sun. And from the top of that shadow was a nebulous, plume-like umbra—the shadow of smoke still arising from the stack!

I think I must have moaned then, like a child who has lost its way in the dark. The last defenses of my reason, my cool, twentieth-century culture was down—and I believed! Believed that there were such beings as demons. Believed that Thor the Thunderer—mythical god of the old Norsemen—had indeed invaded this place and made it his own. Believed that my sweetheart had fallen prey to forces against which my strength and courage were as nothing...

Thor the Thunderer...

As though my admission of his existence had summoned him, a great roaring suddenly burst against my eardrums. It was as though twenty cannons had been touched off simultaneously. The tremendous uproar seemed to fill the vast room from wall to wall. It shook the windows in their casements, vibrated against my quaking body with a physical shock. I clapped both hands over my ears to keep my eardrums from being burst, and frantically searched in vain with my eyes to find the source of this Gargantuan bellowing. I found none—the sound seemed to come from all quarters at once.

Gradually it diminished, began to die away—and changed, suddenly, to a stupendous, stentorian guffaw. It was the laugh of a giant—raucous, filled with Jovian mirth, but under laid with cruel irony. Such laughter as must have been heard on fabled Olympus, as the gods played their heartless games with poor, helpless mortals...

Then it, too, died away, and abruptly I became aware of a patch of light that had formed in the center of the floor, just beyond the last of the plate tables. Was the god about to appear in tangible mortal form? Was I to witness one of those fabulous appearances the ancient poets wrote of so often? At that moment I would not have been surprised if Thor had actually materialized in the flesh, so overwrought were my nerves and imagination. Yet what actually happened was, if possible, even stranger.

The light remained for a moment, then suddenly disappeared. It was replaced by rainbow-hued bands that flickered in the air above the spot where the light had been. These bands shimmered back and forth, seemed to run into and coalesce with each other in a manner impossible to describe—and then, suddenly, as though created out of their union, a human form began to take shape. The figure, for a moment, was hazy, nebulous—and then, abruptly, it was clear and concrete. A human being had, indeed, taken shape before my eyes.

But it was not the figure of a Norse nature-myth god. It was no fantastic, diabolical being from another world. It was the semi-nude form of the one person in all the world I had most desired in that moment to see—Jeanette Gravesend, my fiancée!

A CHOKED shout bursting from my lips, I sprang toward that white, almost nude body. But I was not quick enough. Even as I ran toward her, Jeanette swayed and collapsed, falling to the floor with an utter laxity of her muscles that swept a chill of ghastly dread through my body. Then I was kneeling at her side, supporting her limp, adorable body in my arms, and raining kisses on her up-turned, still face.

My frantic hand caught the faint pulse of life beating gently beneath the snowy mound of her left breast, and I sobbed aloud in relief. What horrors she had experienced, what inexplicable, fantastic thing had been done to her that she should appear to me out of the empty air, I did not know, or for the moment, care. It was enough that she was alive, and apparently unharmed. I gathered her in my arms and stood up, turning toward the door through which I had entered this place.

As I did so, that door swung slowly open until the tall, spare figure of a man was revealed standing on the threshold. The strong light of the afternoon sun was behind him, so that his face was in deep shadow. I did not need to see it to recognize him—it was Raold Storm, my uncle, who had been missing for three days.

I shouted a joyous greeting, and ran toward him with Jeanette in my arms. But with an abrupt movement, he stepped inside the doorway, and slammed the portal behind him. He stood there, arms folded across his spare, bony chest, until I had reached him. He did not answer my greeting, and his first words, as I came to a halt in front of him, nearly caused me to drop Jeanette in the extremity of my amazement.

"You scheming young pup," he snarled, and his face was suffused with what had every appearance of being a towering rage, "if you think you can force me to give up what is rightfully mine by any such fantastic monkeyshines as these, you're even crazier than I think you are. I don't know how you are doing it—I'll admit I don't understand a tenth of what I've seen and experienced these last three days—but I know, now, that you're behind it, somehow. You're trying to get my share of the holdings in this factory. You want the proceeds from that Wyandotte contract all for yourself. Well, let me tell you it won't work! I'll fight you to the last—"

"For the love of God!" I groaned. "Open that door so we can get out of here. I haven't had a thing to do with this—I don't know any more about it than you do. There's something unexplainable going on here, Raold, something we may never be able to understand—"

"Rubbish!" snapped Raold. He took a step toward me, and shoved me backward, so that I staggered under the burden of Jeanette's body. "That's exactly what you want me to believe! Why, you're even base enough to use that poor girl, there, to help make a dupe of me. I'm convinced she's innocent—she couldn't have put on the terror she showed when those—whatever they were—grabbed her. But you..."

I turned aside and gently lowered Jeanette to the floor. Then I straightened and again confronted my uncle.

"See here, Raold," I said, trying to make my voice calm and dispassionate, "I don't know what you've gone through, or what you have seen. If it's been anything like what I've experienced, I don't wonder that you're practically frantic—that you're willing even to believe that I am behind it, since that would allow you to account for it in something approaching normal terms. But I tell you there is something inexplicable loose in this factory—"

Just in time, I stepped backward, threw up my left arm and blocked my uncle's furious swing for my jaw. Then I grabbed him and shook him with a savagery that must have loosened every joint in his old body. I was mad with rage, myself, in that moment—crazy with a sudden flood-tide of emotion that had been accumulating for hours. Here we were within a few steps of safety, and this fool uncle of mine insisted on blocking our path—keeping us from easy escape while the evil, nightmare forces that had been tormenting us gathered, perhaps, for another attack!

"You fool!" I snarled. "You damned, leather-headed idiot—"

But in spite of the punishment I was giving him, Raold seemed suddenly utterly oblivious of me. His eyes were slowly widening as they gazed with an expression of growing terror at something apparently behind me on the floor. As I paused in my shaking of him, and slow icy fingers crept upwards between my shoulder-blades, his quivering mouth formed a single whispered word:

"Look!"

Slowly I turned about, glanced over my right shoulder and saw—nothing. There was nothing, no one behind me—and the floor was empty... Then a choked cry rang from my lips and I whirled completely around: There should have been some one behind me—for that was where I had left Jeanette. Now she was gone—had completely disappeared as mysteriously, as fearsomely as she had materialized before my eyes.

I had perhaps two seconds of the awful realization that again I had lost her. There was a low chuckle behind me. I heard a swishing sound—and something struck my head. I retained consciousness a second longer; I remember falling to the floor. Then things went blank.

WHEN I came to I was standing upright. That is, I was being supported in an erect position by a couple of iron bars which projected from the wall at my back and passed under my arms on either side. My arms were pulled down in front of me by some weight which imprisoned my hands. As my vision cleared I looked down and saw that my hands were rigidly incased in a heavy bulb of solid glass. My feet were similarly fettered.

My first thought was that while in an unconscious state, my hands and feet had been dipped in a vat of molten glass; but as my reason gradually cleared I saw that this could not have been the case, since neither my hands or feet showed the least signs of burns. They, of course, would have been seared to nothingness if this had happened. From their appearance I knew my strange bonds were of silica, which had been fused with an excessive amount of alkali to make them primarily fluid, and then mixed with ground chalk or dolomite to cause them gradually to harden. The hardening process was complete, and I was far more effectively bound than by any ropes.

The pain in my armpits, where the iron rods supported me, was intense. With a groan I straightened up, taking most of my weight off the rods. My hands and feet were numb and cold from the pressure of the silica, and the back of my head throbbed hotly.

I remembered, then, the weird things that had happened prior to my being knocked unconscious. There was no doubt in my mind as to who had struck me, It could have been only my uncle, who took advantage of my shock at Jeanette's disappearance to smash me on the head with some weapon he had concealed about him—or, perhaps, had picked up from the floor.

I supposed that his reason for doing this was to retaliate for the things he thought I had done to him—whatever they were—but it seemed very strange that he could have been so savage. I wondered dazedly what had given him cause to think that I was "behind it all," and that I wanted to cheat him out of his share of the Ladore company...

There were, of course, no answers to these riddles, any more than there were explanations for the other eerily terrible things that had happened. Why old Pete Sars had been killed in such a particularly atrocious fashion? How was it that smoke arose from furnaces in which there were no fires? How had Jeanette materialized from nothingness—and then as mysteriously disappeared? Where, in God's name, was she now? What unimaginable things were being done to her?

One thing gave me cause for hope on that score. Apparently she had not been seriously mistreated when she was first taken captive by the mysterious forces that held her; therefore, there was cause to believe that she might escape serious injury this time. But it was a slender hope, and I knew there was little chance that either of us would escape from this strange and fearsome predicament alive.

The sound of metal clanking against metal aroused me from my gloomy musings. Startled, I looked up—and saw the door of one of the big electric furnaces swing slowly open.

There was no visible presence in all that vast room but myself. I knew that great muscular power was needed to pull back one of those huge retort doors—and yet there it was, apparently opening of its own accord. On my left was a large switch panel on which were mounted the relays, meters, and switches which controlled the machinery of the entire plant. From the corner of my eye I now saw the lever of one of the big box safety switches snap suddenly down—but though I turned and looked squarely at it immediately, I saw no person who could have performed the operation.

IN RESPONSE to the closing of the switch a remote hum arose, and slowly one of the big pots rolled out of the furnace on its overhead traveler. Behind it the retort door swung shut—and a sharp clack from the switchboard announced that the big relay, which fed the heating units of the furnace, had snapped open.

The pot rolled slowly and majestically forward until it was poised above pit No. 3, whereupon the switch which controlled its locomotive power snapped open, and the smaller dump-motor switch clicked shut. The pot began to tilt on its lateral axis until the molten glass ran over its lip and fell into the pit below.

No words of mine can ever convey the eerie effect of this whole process. I had seen it done before many times—but I knew that, nearly automatic though the whole operation had been made, there was need for the presence of at least two men to accomplish what I had just seen. The furnace and retort door did not open automatically, and the switches—although they automatically sprang open in case of accident or current failure—always had to be closed by hand.

It was as though the plant had become imbued with a dark, sinister life of its own. As if the machines had taken that last step—and to me it had always seemed somehow a short one—between their own strange, uncanny semblance of life, and the actuality of reasoning existence!

Now the pot had dumped the last of the molten glass into the pit. Its mysteriously controlled motor carried it back about half-way to the furnace, where it came to a halt, and for a time there was silence, save for the strange, crackling sound of cooling glass that came from the pit.

But weird as all this had been, its strangeness was as nothing to what happened next.

There was a sudden commotion outside the building near one of the side doors, which presently swung violently open, disclosing, again, the lean form of my uncle.

He was comporting himself like a maniac, or a person in the grip of an attack of catalepsy. His gaunt figure lurched through the door, staggering from side to side, charging violently forward one second, and coming to an abrupt halt the next. His hands, which were bound together at the wrists with ropes, threshed madly at the empty air, and he was uttering a series of incoherent, hoarse cries mingled with curses and imprecations.

I watched his terrifying progress across the floor of the pouring room for several seconds, before I noticed another and even stranger thing about him. This had to do with the curious appearance of the upper portion of his right arm and, occasionally, his whole right side. At times these sections of his anatomy seemed to disappear from view as though they had suddenly been rendered transparent!

A sudden thought struck me then, and I felt a cold, sick churning in my stomach. There was another explanation for my uncle's behavior which would account for it more reasonably—if it were possible to use such a term in connection with it—than either catalepsy or mania: He was acting precisely like a person who was being forced along against his will by some one else—a person, in this case who was invisible—and who, occasionally interposing part of his body between me and my uncle, caused the latter to become partially invisible himself!

But if more reasonable in one way, that idea was completely mad in all others. I felt hysterical mirth bubbling inside of me. I wanted to shriek with insane laughter as my jangling nerves clamored for release from the terrific strain they had been under for hours.

I did not laugh. I saw now where my uncle was directing his steps—or having them directed for him. It was toward the freshly filled vat of molten glass!

MOLTEN glass is molten stone. It flows only at white-hot heat. It is as destructive to organic matter as melted steel. And I knew, now, that the body of Raold Storm, my father's brother, was destined to be immersed in the deadly stuff in pit No. 3.

I wanted to avert my eyes, turn away from the horrible spectacle that I knew was imminent—but I could not. A terrible fascination kept my eyes riveted to the struggling, pitiably fragile form of my uncle as he drew nearer and nearer to that fearsome pit. Not even when a pair of pot grapples were lowered from a near-by crane and cruelly clamped over his thin shoulders, could I tear my gaze away. And when his still struggling, grotesquely writhing form shot into the air and was whisked out until it dangled over that terrible pit, I cursed and raved helplessly—but still I had not the will to close my eyes.

The old man was given no respite, no opportunity to say his prayers, if he had cared to. The proceeding went forward with the unfaltering precision of unreasoning machines. Unreasoning? How did I know?

The sun had nearly set. As his body descended toward the yawning mouth of that lethal vat, old Raold suddenly ceased his struggling, and his thin form hung there like a grey rag in the fading light. Yet, at the last moment, he looked up and saw me. His eyes fixed on mine, I saw the old man smile a little. Then his voice reached me, faint but clear:

"Forgive me, Johan," he said. "I misunderstood. I know you are not to blame. It is—"

The rest was lost in the most frightful scream any mortal ever had to listen to. Raold's feet had touched the surface of the glass!

Now, at last, I could close my eyes. I squeezed them tight in the agony of listening to those terrible, soul-rending cries. They broke out again and again, ringing through that horrible, vaulted room with a sound that was inhuman, utterly unearthly. They made me feel the progress of his agony-wrung body down into the depths of that hellish stuff—now to the ankles, now the knees, now the thighs...

Raold's screams thinned to a high, piercing wail. There was a horrible gurgling sound—then blessed silence.

I was covered with the sweat of terror. I sank down on my torturing rods in a state of complete collapse, and my head fell forward on my chest.

"Why, O God—" I muttered—"why...?"

"Why?" echoed a deep, ironical voice at my side. "Need there be a reason, then, for the sport of gods?"

My head snapped up, my eyes fixed on the point in space from whence the voice had seemed to come, and from where there now rolled out the sound of deep laughter... but I saw—nothing!

"Who—" I gasped, "What...?" Eerie, overmastering terror had me by the throat. I could say no more. But the laughter died out, and I heard nothing further. Again my head sank forward until my chin was resting on my chest.

EITHER I slept or fainted from excess of emotional tension. When I awoke it was pitch dark, save for an area in the middle of the room which was lit by a single, overhead floodlight. One glance at what lay beneath that floodlight was enough to wipe the last fogs of unconsciousness from my brain and bring me quiveringly awake, my heart contracting with horror. And I knew in that moment that regardless of what was done to me—even though I eventually suffered the same awful fate as my uncle—it would not matter. The worst of my nightmare fears was about to be realized before my eyes.

One of the great lens tables lay under that floodlight. From one of the coke furnaces, already a pot was slowly swinging forward. And upon the table was the scantily-clad body of Jeanette!

I screamed so that the rafters rang with the voice of my terror, and lurched forward. My arms slid off the rods which had so painfully supported me, and my back cracked with the strain as my weighted feet pulled me back into balance. At the same instant I was conscious of a whispered voice at my side.

"Easy!" the voice said. "Keep quiet... Here, put your hands in dis..."

My frantic eyes beheld a black-robed figure at my side. It was holding a large pail in front of me, and I detected the characteristic odor of hydrofluoric acid. Instantly I plunged my glass-fettered hands into the pail.

"Easy—" again cautioned the voice—"look out for de wrists!"

But I did not care. Some of the acid was already biting into the flesh of my wrists. I hardly felt the pain. My eyes were agonizedly watching the progress of that pot. Would the acid work in time? Would I be cut free from my bonds soon enough to snatch Jeanette's helpless body from that ghastly table?

I could feel the glass slowly sloughing away, the weight on my hands growing less. In the meantime a second figure had appeared with another bucket, and had gone to work on my feet. I could feel the acid burning into my ankles—and I had never known that torture could be so sweet.

But the dreadful pot came onward. Now it was poised above the table on which reclined my beloved. I heard the clack of the opening relay; the click of the closing dump-switch. Slowly the pot began to tilt...

"Hurry—hurry!" I groaned. "For the love of God, man—"

"Yoost a minute," said the man who held the pail at my hands. "De acid iss slow."

Slow—yes, dreadfully slow. I knew it would be minutes before I was free. "Can't you get a hot iron?" I whispered huskily. "Or a diamond—?"

The pot was tilting... tilting...

"Nej! Ve do vell to get de acid. Ve get kilt, yet—"

I KNEW that voice, now. It was old Fridtjof Krag, the office manager. Why he should be there, garbed as he was in that black burlap gown like a Greek Orthodox monk, did not concern me at the moment. A trembling had seized my limbs so that every joint in my body went flaccid. I would not be in time!

My eyes, distended with helpless horror, saw that terrible pot dip past the level of its contents, saw the milky glitter of the liquid glass oozing at its lip—saw the first of the terrible stream spill over and splash with its peculiar crackling sound on the steel of the table!

Iron strips lined the edge of the table. When it had been filled to that depth, Jeanette's body would be flooded over, encased in rigid glass. Already the deadly fluid was spreading out, creeping upward toward her body as the stream from the tilting pot grew heavier...

My hands were burning as though I had thrust them into raging flames. Some of the acid had eaten its way through the opening at my wrists. Snatching them out of the pail, I brought them down with a crash on its edge—and the remaining glass shattered and fell away. My hands were free! They were raw, scarified by the acid—but they were free...

But my feet were not. The heavier glass which encased them still resisted the acid. I looked down at the black figure which crouched over them, still patiently and carefully—too carefully—splashing them with hydrofluoric. I snatched the pail from his hands, intending to dash its whole contents on the glass, when a heart-freezing scream turned my body to stone.

My eyes flew to the table upon which lay the body of my fiancée—and my own scream joined hers. The spreading tide of glass had reached her feet!

She was struggling to get off the table, but as I watched, with the ague of horror wracking my body, four black-cloaked figures suddenly appeared within the circle of light about the table, and grasped her limbs, holding her there while the glass flooded over her tender, white body.

"For God's sake, get her away from that table!" I shouted at the two men who were trying to free me. "Forget; about me—get her away before it's too late—"

But I knew that already it was too late. By now the glass had eaten into her flesh. By now the most merciful thing that could happen to my beloved would be a quick release from her suffering—sudden death. If I had had a gun in that; instant I would unhesitatingly have shot her through the head!

"Nej!" growled Krag. "Ve be kilt. Do not shout so loud."

But the roar of the spilling glass drowned out what noise I was making, and I was flooded with rage at his cowardice.

"Damn you!" I roared. "Damn you—"

In that instant I felt my feet come free. I kicked off the clinging particles of gummy, half-dissolved glass and dashed madly across the room toward that grisly, polished table beneath the glaring floodlight, catching up a stout steel smoothing-bar from the floor as I went.

SILICA fused with an excessive amount of alkali—water glass—has much the same appearance when in a liquid state as true glass at white-hot temperatures. Because of this, and because of the emotional state I was in at the time, it is not to be wondered at that I thought it was molten glass which was being poured upon that table. But when I was close enough to note the bare hands of Jeanette's captors, and the white, unburned appearance of her body, even where the glass had touched it, I knew the soul-restoring truth: It was water glass that was being poured upon her!

That knowledge swelled my heart to bursting with thankfulness, galvanized my aching body with the energy of half a dozen men. I fell upon the nearest of Jeanette's captors with a shout. He whirled about to meet my attack—but he was much too slow to save himself. I struck him with my crude weapon and he sank to the floor with a groan.

I was upon his companion in the next instant. We met with a crash, for he sprang at me at the same moment. The bar was jarred from my hand and fell clattering to the floor, but I quickly extricated myself from the bear-hug in which he tried to envelop me, and landed a killing punch on the point of his jaw with my right fist. He went down like a felled tree.

Then Jeanette was in my arms, her body coated with gummy water glass, but otherwise unharmed. I caught her up and whirled about, dashing off toward the far end of the building, with the two men who had been on the other side of the table close behind me.

My retreat to the main door was cut off. In order to reach the side doors I would have to leap over the cooling vats—which was impossible with Jeanette in my arms. My one chance for sanctuary lay behind the door of the precision instrument testing laboratory, and that was where I was heading.

As I reached it I lowered Jeanette to her feet and burst the door open. There was a crash and startled exclamations as I did so. I thrust Jeanette into the room, which was brightly lighted, slammed and bolted the door behind me—and found myself confronting two more of the black-robed and cowled figures!

They sprang at me instantly.

For a moment I was overwhelmed by their sheer weight, my movements hampered and made futile by the voluminous burlap of their robes. Then I smashed my fist, with all the weight of my body behind it, into the cowled face of my nearest antagonist. He went over backward.

Jeanette had snatched up a small spectroscope from one of the benches. As the man fell at her feet, she brought it crashing down on his head. It wasn't much of a weapon, but I knew he would be out of the fight for a long time.

But I caught Jeanette's little useful maneuver only from the corner of my eye. My attention was more fully occupied with my remaining antagonist. He was a brawny fellow, and I had my hands full. I landed a couple of blows on his hood-muffled face hard enough, I thought, to have felled a bull—but he kept boring in. One of his ham-like fists landed squarely on my mouth, and my back slammed against the door. I could feel the shattering reverberations of a heavy bludgeon being battered against its panels, and I knew it would be a very short time, indeed, before our enemies on the outside would be swarming in upon us. The thought gave me the strength of desperation.

I sprang back at my opponent, and this time he was powerless to ward off my blows. I slashed at him with the insensate fury of a primordial man defending his mate—and at last he went down.

Quickly I upended one of the benches with which the wall was lined, sending the valuable instruments and scientific glassware with which it was stacked crashing to the floor. I thrust it against the door and wedged it there with a heavy stool which Jeanette thrust into my hands. I stood for a moment watching it shake in response to the blows that were being rained on the door, and wondered how long it would last.

We were in a cul-de-sac from which that door was the only exit. There were no windows, the room being in the center of the plant and ventilated by forced draft. There was a skylight in the ceiling, thirty feet above our heads. It might as well had been three hundred feet.

I turned and looked at Jeanette. She was leaning against one of the benches, calmly peeling strips of drying water glass, which had reached about the consistency of celluloid, from her body. She looked up and smiled at me, completely unabashed by her almost nudity.

"It's a good thing this wasn't done to you," she said. "You're so hairy!"

THERE was nothing to do but wait and prepare ourselves as best we could for the inevitable battle when our besiegers had broken through the door. I didn't know whether I was fighting human or supernatural forces—but it had been very reassuring to feel ordinary flesh and bone crack under my fists. I was far from being without hope that we could emerge successfully from this mess.

Then the memory of those apparently invisible agencies that had been able to achieve such fantastic and terrible things swept back over me. I glared wildly about the room. How could I know that they were not, even now, creeping upon us?

I sprang to Jeanette's side and threw my arms about her in an instinctively protecting gesture.

"Darling," I whispered, "do you know that when I first saw you, you seemed to materialize out of thin air? Have you any idea how it was done?"

She shook her head.

"I don't know much of anything that happened after those—those monks, or whatever they are, grabbed me. I think they kept me doped. I—"

But as she talked my eyes suddenly lit upon a couple of curious instruments lying by the door. I remembered the crash that had accompanied our entrance into this room, and I divined that it was these instruments I had knocked over.

I sprang back to the violently vibrating door, and pulled the bench away from it long enough to discover that there were a couple of holes near the bottom of the door, about three feet apart.

Replacing the bench, and bracing it again with the stool, I went over and picked up the instruments I had knocked over. They were mounted on tripods which elevated them about the same distance from the floor as the holes were in the door. They looked like a couple of streamlined "bull's eye" lamps, and were connected with a base outlet in the wainscoting of the wall next the door. I began to understand something.

But before I had had a chance to try out my theory regarding these lamps, my eye suddenly fell upon what looked like a folded document lying on the floor by the side of the man I had knocked out. I sprang to it, snatched it up, opened it. It was my father's will.

I knew the contents of that will. It left the Ladore Glassworks to my Uncle Raold and myself as equal partners. In the event of the death of one, it was to go entirely to the remaining partner. In the event of the death of both partners, it was to go to the nearest remaining relative. In the event that no relatives were living, either blood or by marriage, the plant was to be turned over to the employees on a strictly mutual, profit-sharing basis.

A movement on the part of the larger of the two men on the floor caught my eye. I thrust the will into Jeanette's hands and went to his side. I jerked the hood from his head and gazed into the face of Tyson Vines, our company's lawyer.

Leaving him where he was, I walked over to the nearest bench and picked up a small graduated beaker which was filled with a dear, colorless fluid.

"Look at my wrists, Vines," I said. "Those burns were caused by a small amount of hydrofluoric acid. That's what's in this beaker, Vines..."

THE man's face paled. His eyes flew from my raw, scarified wrists to the beaker, and then back to my face.

"You—you aren't going to...?" he faltered.

"Yes," I said. "You're going to get this—all of it—square in the face in exactly five seconds if you don't tell me what is behind all the criminal nonsense that has been going on in this plant... Five seconds, Vines!" and I raised the beaker threateningly.

"All right—all right—I'll tell," he quavered, shrinking away from me. "It's—it's that will of your father's. If all the living members of the firm were out of the way—and their families—the workers would get the plant. I—I got several of your workers interested in my plan—Hans Unger, plate foreman, Nils Moe, Heinie Jorgensen, several others—"

"How about Fritdjof Krag and Sven Larsen?" I asked.

Vines threw me a quick glance. "So they spilled the works to you, did they? I never did trust that pair. They were in on part of it. Actually they knew very little. We didn't call them in on this, figured to wait until it was all over—and then they wouldn't dare talk because that would make them accessories."

I smiled to myself, and he went on.

"We figured to scare the majority of the workers out of their wits, so they would go away and never come back, leaving us a clear field. Together we worked out a way to do this and get rid of all of you at the same time. Jorgensen, here in the laboratory, had developed two new rays which he called the phi-upsilon rays. The two rays, focused on any object, will refract against the eye of the observer in such a way as to bend the light rays around the object. Actually, the person looking at the thing the rays are focused on, sees around it. In other words, he isn't able to look at the object at all—and hence it is invisible to him.

"We sent a man up the coke stacks on a bosun's-seat to build fires in the screens at the tops. We killed old Pete Sars in such a way as to frighten the wits out of anyone who saw him. Then we kidnapped old Raold. We held him until we could get you all together—and as luck would have it, the girl came up of her own accord. Then it was easy to scare you into following her. We were hoping she would come. We figured that her body, frozen into a cake of silica, would make quite an impression on the workers. We were going to give you the same kind of a bath that we gave old Raold, and leave your two charred corpses, both nicely glazed, hanging there in the pouring room..."

Vines broke off to laugh uproariously, and I saw that the man was stark mad. I recognized that laugh, too. It was the one which had followed the thunder I had heard in the pouring room. Thunder, I realized now, produced by no more supernatural means than, perhaps, the banging of a wooden mallet against the interior of one of the boilers on the floor below. Quite obviously the man's twisted brain had been carried away by the refined sadistic possibilities of his elaborate scheme, and he had been unable to resist the pleasure of torturing us mentally as well as physically before he had put us to death...

"Raold got a funny idea in his head," went on Vines after a moment. "I took care of him most of the time, and Jorgensen kept the rays on me, so that poor Raold could never see what was holding him. It nearly drove him out of his head. I sat and watched him for hours. It was great fun. After awhile he got to mumbling to himself—thinking aloud. I could tell from what he was muttering that he had begun to believe you were tied up in some scheme to rob him of the plant. I think he made himself believe that to keep from going nuts over that nonsense about Thor and his devils that we had been driving into the workers' heads for months. Anyhow, I thought it would be fun to see you together, so I let him come in and accuse you. After I had had my laugh I cooled off both of you, and the show went on—"

I HAD been conscious for some moments that the pounding on the door had ceased. Now the muffled sound of a voice percolated through to us.

"Please, Mister Johan, vill you let us in?"

It was Krag's voice. I replaced the beaker on the bench, went to the door, removed the obstruction I had placed against it, and opened it.

Krag and Larsen, both looking very sheepish, stepped over the bodies of two other black-cloaked figures which lay just beyond the threshold, and came in.

Krag cleared his throat nervously. "I got to apologize to you, Mister Johan. I got no idea vot dese devils plan to do. Dey say dey get de plant for the vorkers, unt I say I help dem. I'm communist, you know—I t'ink de vorkers, dey shood share de same as—"

"It's all right, Krag," I interrupted. "I know your views, and you're entitled to them, if they seem reasonable to you. I know, too, that you and Larsen were duped in this affair; but why did you try to keep me from coming down here? Why did you try to hand me all that boloney about Thor and Loki?"

Krag hung his head. "Vell—" he began—"now you t'ink me crazy, sure; but I really tought de old gods had come back. Yor fadder—vhy did he close oop de factory effry ten years—unt his fadder before him? I vas afraid..." Suddenly he raised his head. "But Larsen unt I, ve follow you. Ve see dese fellers putting on dere robes in de sand shed, unt ve steal a couple unt go inside to see vot goes on, unt—Look oudt!"

Krag's gaze had suddenly gone beyond me. At the same instant there was a terrified scream at my back. I whirled, and saw Vines, his face distorted by an expression of maniacal triumph, gripping Jeanette's arm with one hand, while with the other he held aloft the beaker with which I had forced his confession from him.

"All right, come and get me!" he shouted madly. "Just take one step—and see what becomes of the pretty face of this sweetheart of yours, Storm!"

He laughed insanely.

"Now," he said in a lower, gloating tone, "we're going out of here—this nicely built little female and I—and I wouldn't advise any of you to try and stop us. Mayhem, added to the other charges against me, will mean nothing, and—"

He had no opportunity to say anything more. I sprang toward him with all the power of my legs. Instantly he turned and dashed the contents of the beaker into Jeanette's face. She screamed. Larsen and Krag, behind me, shouted in horror—and then I was upon him.

He fought like a maddened cougar. We crashed to the floor. Vines kicked and bit like the animal he was, and I retaliated with all the force of my fists, but he seemed insensible to pain. Suddenly, with one terrific surge, he threw me off balance and rolled over on top of me, grabbing up a pair of test-pot forceps from the floor as he did so. He swung the forceps high over his head for a killing blow which I knew I would be unable to ward off—and then suddenly he crumpled to a senseless heap on top of me.

"Dere!" came Krag's voice from above me. "I guess dot fix his clock!"

He stood there, proudly brandishing the same much-abused spectroscope which Jeanette had used to render Vine's companion in crime hors de combat.

I glanced up at Jeanette and smiled.

"Phew!" she said, ineffectually trying to wipe her face with her palms. "Why didn't you tell me it was only water!"

"Sure," I said. "That's my private drinking glass. Nobody in the plant would dare use it for anything else."

IN SPITE of the disclosures which arose during the trial of Tyson Vines and his henchmen, very few of our Norwegian workmen would come back to us. Somehow they seemed to feel that no physical explanations could quite cover all the things that had happened in the Ladore Glassworks plant. But we accumulated a skilled staff among other, and less superstitious workers, and are carrying on famously.

Nevertheless, I have a feeling that when the decennial anniversary of the founding of the works rolls around, the plant will be closed for the customary two weeks. You see, I had to give my word of honor to two people that it would be: Krag, who threatened to leave my employ if I didn't—and Jeanette, who says she will desert my bed and board unless the same condition is fulfilled. I don't see how I could get along without either of these people—even if they are childishly superstitious—so I have complied...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.