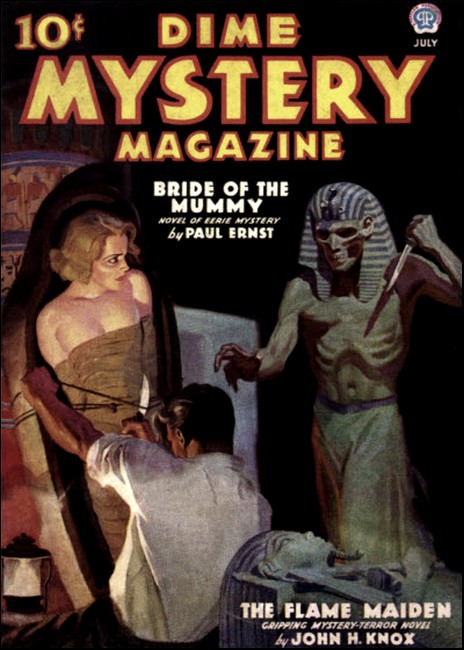

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Dime Mystery Magazine, July 1936, with "Circe's Lover"

One after another they went, those lovers of Corliss—leaving her arms to enter those of the Last Mistress—Death. And no physician could say by what means they had died!

THE act of getting out of bed and slipping into my lounging robe was a gesture of surrender. I was licked—I had permitted the phantasms and ghosts that haunted this place to chase me out of bed. At last I had tacitly acknowledged that whatever was wrong with The Beeches was powerful enough to rob me of my sleep and give the lie to my repeated assertions, that whatever mysterious menace was accredited to the old place was all a myth and a delusion.

But maybe it was something else. Perhaps I had not been driven from my bed—perhaps I had been lured! It may have been that I was responding not to aroused nerves, but to a subtle, inaudible call. Yes, that may have been it—for upon the veranda, just outside the French windows of my bedroom, I met Corliss...

She was as beautiful as the dark spirit of the night, itself, and as warmly seductive as the soft May night wind. She stood there, bathed in the moonlight, its shafts turning her gossamer nightdress into an aureole of spun gold, that clung to the delicious curves of her body like a shimmering cocoon.

My throat caught. The sight of her standing there aroused an emotion that shut off my breath like a hand on my windpipe. It was an instant, overmastering spate of passion such as I had never known before—and with it there was an accompanying emotion. And that emotion I could name also—it was a rip-tide of terror that flashed along my nerves like a bolt of lightning through high-tension wires.

I could name them both, for I had felt them both—and always together—many times before. But never had sight of the girl struck my senses with such impact as tonight—but then, never before had she appeared outside my windows with the moonlight denuding her glorious body of veiling draperies.

"Come," she said, and an ivory-white arm reached toward me, "I am glad that you, too, cannot sleep. We shall take a walk down to the summer-house and when we have returned—we will be able to sleep."

And though three of this woman's lovers had died mysteriously, and though I knew I knew she was as dangerous as a cobra—and though I loved not her, but her blonde and innocent sister—yet I took her hand and walked with her across the close-cropped, dew-hung grass toward the summer-house that nestled in a far corner of the wall...

THREE men had died... And I loved not Corliss, but

Pandora, her radiantly beautiful little sister...

I was yielding to an urge as irresistible as it was sinister. What was left of my reasoning power switched to the task of rationalizing my action to myself. I was not being lured, I told myself, I was going with this girl in order to verify the arguments I had many times before put forward in her behalf.

She was not responsible for the death of those three young men, I had said. Belief in vampirism in the twentieth century, I had insisted, is nonsensical—anachronistic. Besides, these supposed victims had not acted as the victims of vampires are popularly supposed to act. They had not died as the prey of the succubi are supposed to die. They had come to Corliss, they had loved her—everybody knew that. But they had not been near her when they died. There were no marks upon their bodies... At least, no discernable marks...

The summer-house was a vine-hung, enchanted bower in the moonlight. Corliss entered and sank languidly upon the upholstered bench that ran across the back of it. I stood at the arched entrance and watched her.

The moonlight filtered through the leaves that shrouded the summer-house. Shafts of the pale light played upon the lissom, vibrant form of the reclining girl, and as that body moved, stirring restlessly under its draperies of transparent silk, a cold breeze fanned softly and eerily across the back of my neck. Like a snake, that body was—dappled and sinuous—and deadly. The fitful moonbeams clothed it with the irridescent spots that mark the scaly hide of the cobra. I shuddered, and in that moment I might have had the strength to turn and flee. But her voice whispered to me—whispered with a sound like a serpent's hiss. Her arms, white and gleaming like a pair of milky snakes reached out of the gloom toward me. A stronger shudder shook me—then I turned back to her. I entered the summer-house...

IS there a man living, capable of great love for one

woman, to whom all other women are as so much unattractive

clay? Did the passion I felt for this darkly seductive girl

give the lie to the love I bore Pandora? Was I nothing but

a whilom lecher—or was I battling with forces which

men are not, in ordinary life, called upon to wrestle

with?

I had plenty of time, on the following day, in which to ponder questions which long before baffled far abler philosophers than I—for as though she sensed that a dark and unclean shadow had fallen between us, Pandora left me strictly alone.

When I came down to breakfast I found that she had arisen early, taken her roadster and driven down to Beresford. Corliss invariably had breakfast in her room, and the butler had only Colonel Treppham and myself to serve.

I had no appetite, and I could feel the Colonel watching me from under his black, bushy eyebrows. At last I pushed back from the table and would have arisen, but the Colonel suddenly raised his head and fixed me with his burning, hypnotic eyes. I could feel the blood mounting in my face under that searching, analytical gaze—and inexplicably, terror—the concomittant of every emotion one felt at The Beeches—flooded into my heart.

"Be careful!" he said, at last, and no words of mine will ever convey the malevolent, harsh stridence of his tone. "Three men have died, Ralph Carey... There may be a fourth!"

His withered, shrunken cheeks hung lank as a corpse's jowls, and the high, thin beak of his nose made him look like an obscene old cormorant, hulking there in his chair, croaking predictions of doom. I arose from the table and walked out of the house into the sunlight of the May morning.

Yet, despite the glory of the late spring day, old Colonel Treppham's words burned in my brain as I walked through the woods at the south end of the estate: "Three men have died... There may be a fourth!"

Never before had Colonel Treppham or any member of his family acknowledged by the slightest hint that there could be such a thing at The Beeches as foreknowledge of the three deaths that had taken place in the county during the past six months. It was true then—the scandalous gossip that was being whispered in Beresford and throughout the entire county—there was some connection between the deaths of those three young men and the fact that they were known lovers of Corliss's!

But the thing was impossible, I told myself. Absurd! I had talked to the coroner, the undertaker, the two physicians who had been called on in those deaths. There was absolutely no evidence to show that the three men had been murdered—that they had died from anything other than natural causes. No poison, no marks upon their bodies, no abnormalities of blood, bone or tissue. Nothing. And yet, in every case it was known that all three of those men had visited The Beeches within six hours of their end! And in each case the death certificate had shown cardiac thrombosis as the cause—the easy, natural death that is the reward of a long, temperate and healthy life. The usual pathological cause of what is called, "death from old age!" Yet they were men as young as I was!

And I was to believe that Corliss could kill—and had killed—men so that their bodies were found in such condition? Nonsense! Colonel Treppham had taken a sudden dislike for me. He wanted to scare me from the house. His senile brain had become unbalanced from the effects of the scandal which he knew was being whispered about his elder daughter. That was all...

And yet he had never opposed my suit for Pandora's hand—had even encouraged it. He had always been warmly friendly and cordial, had consented to our marriage with the appearance of great satisfaction. That marriage which was to take place one week from today—I fervently hoped...

I was, indeed, overwrought and thinking incoherently or I would have sensed the true answer, then. But my mind and emotions were in a helpless state of confusion as I stumbled on through the forest. And all I knew was that the shadow which for so long had hovered over the love of Pandora and me had descended, at last, and had enveloped us in its gloomy, weirdly mysterious folds.

WHEN I returned in the early afternoon from my

long hike in the woods, I had decided that there was

but one reasonable course of conduct left—to

persuade Pandora to leave this place with me

immediately—today—get married, and return to my

home in the city.

I felt better when, as I neared the house, coming over the broad lawn from the south, I sighted Pandora's little roadster resting under the porte-cochere. I speeded up my pace—and then suddenly slowed down, again, as I saw Pandora run from the front door of the house and come quickly toward me. There was something about her manner, the jerky, half-restrained hysteria in her pace, that filled my heart with dreadful forebodings; and I did not need to wait until I could see the expression on her face, and the tears in her blue eyes, to know that something terrible had happened...

She reached my side and wordlessly grasped my arm, turning me so that we were walking back toward the woods. To my anxious questions she returned no answer until we were beneath the trees. Then she turned and faced me, leaning back against the bole of a tree as though she lacked the strength to stand alone.

"You must go away, Ralph," she said. "You must go away and never come back—never see me again. I know, now, that I don't love you—that I never did... I've been fooling myself. Please go away..."

For a stricken moment I believed her. I knew, only too well, that she had cause to be disillusioned in me. I knew, only too well, that a heart which could give room to the emotions which her sister had aroused there, was no fit receptacle for the love which Pandora deserved. But, unworthy though I deemed myself, I would not give up without a fight. And in the end I got the truth from her.

Corliss had had a visitor last night, before I had encountered her on the veranda. Pandora had heard him leave and had deliberately followed him. Waiting until he was out of the house, she had arisen, dressed, and followed him in her roadster back to Beresford. Stricken with terrified forebodings she had spied upon his house until long after dawn, sitting in her car a half-block away.

"Shortly after ten o'clock," she told me tensely, "a car drew up in front of the house. I knew it was Dr. Rumsley's. Fifteen minutes later the coroner arrived—and I knew that the worst had happened. I came home then, and I have been trying to decide what to do ever since. I thought that, perhaps you had gone away—I hoped you had, Ralph... It would have solved so many problems. We can never be happy, together, dear. God knows what is wrong with the Treppham blood—but it flows in my veins as well as—as Corliss's..."

THE sky grew steadily blacker as I packed my bags;

distant rumbles presaged the storm that was sweeping down

the valley. The air was humid, stifling—but it was

the weight of dread and sorrow that lay on my heart, more

than the sudden change in the weather, that made it hard

for me to breathe.

I was leaving—parting with Pandora forever. Not because she had told me to. Not because I feared that the poison of the succubus flowed in her veins. But because, at last, I had become convinced of my own fate. I was doomed—a living dead man!

Within six hours after I had left this house I would be a corpse—the fifth to succumb to the terrible curse meted out to the lovers of Corliss...

A small sound at the door of my bedroom caused me to whirl, a grisly fear clutching my heart even before I saw what caused it.

Corliss stood there, leaning against the jamb of the door indolently. Her sloe-black eyes gazed at me from beneath half-closed lids with an expression half lustful, half taunting. The single garment she wore, a scarlet negligee, was swung across her alabaster breast, held in place on her left hip by her hand. She was the embodiment of seduction and—my hair stirred as I realized it—of death.

For, as though all that lovely flesh had suddenly melted away, I saw her then as the skeleton personification of mortality. I looked into those black eyes—and they widened and deepened into the empty caverns of an eyeless skull. My shuddering glance fell to the svelte, silk-clad leg thrusting carelessly out of the folds of her robe—and I saw the grisly whiteness of tibia and fibula, the gauntness of femur above.

I closed my eyes, knowing that they were playing tricks upon me. I trembled with the ghastly fear of insanity, and knew that I was doomed as hopelessly as though I stood even at the gates of hell itself.

I opened them—and she was moving toward me. Her hand dropped the gathered folds of her robe at her hip, and the negligee swung open, revealing the luminous whiteness of her body, tinted rose by reflection of the garment she wore. Her arms reached toward me in the gesture she had used last night, and my whole body shook with the overpowering desire to rush upon her and crush her in my embrace.

But I knew, now, that this woman's lure was the lure neither of love nor of lust—but the lure of the grave. It was death's arms opening to me. It was the red-clad body of an angel of hell who was inviting me into her embrace. I was already damned. Soon I would join those others who had gone before me—but I would not be doubly-damned.

With a curse I thrust her abruptly aside, threw her roughly upon the bed. And, although it was as if her arms were already about me, pulling me irresistibly down upon the softness of her body, I whirled about savagely and, like a spent swimmer who knows not what stroke will be his last, staggered to the door and out of the room...

OLD Colonel Treppham glared at me sardonically from

under the bushy black eyebrows that, together with his

glittering black eyes, furnished such a startling contrast

with his mane of white hair. He seemed to be deriving

a vast amount of secret amusement from my impassioned

pleading—and that, as much as the veiled menace

that lay beneath his amusement, finally drove away my

self-control.

"By God, I'll force you to tell me!" I shouted at him. "You know something about this—or you would not have given me that warning this morning. Why, that alone, if I told the police, would be enough to cause your arrest. And, Pan's father or not, I'll have you arrested if you don't..."

"Fool!" he snarled. "Run to the police, if you want to—and much good it will do you! It's your word against mine in any event; and I'm quite accustomed to talking with the constabulary, hereabout. They come running up here every time one of those ninnies dies—and what kind of a case have they got? Why—that they were known to have visited my daughter Corliss at one time or another!"

He broke off with a cackling chuckle, and then leered like an old satyr.

"As if there was a single young fool in the county that hasn't visited Corliss at one time or another!" He cackled again, then suddenly broke off—and his pasty, age-drooped face fell into lines of evil and malice beyond describing. "Go to the police if you want to—or any place else," he snarled. "But you had better do it quickly. Time for you grows short!"

I stared at him, suddenly rigid with the coldness that flashed along my spine at his last words. God in heaven—might I not be dying even then? How much time did I have left? My throat went dry; a cold numbness pinched my finger-tips.

Then, through the French windows of the library where we were, that opened onto the same verandah my bedroom fronted on, my eyes caught a movement out on the lawn. I turned my head, and saw Pandora running toward the house. Whirling back to Treppham, I snapped, "Very well. Perhaps, as you say, I haven't long—but I intend to use what time I have left in getting to the bottom of this. And if it means the eternal damnation of yourself and Corliss—so much the better!"

I whirled to the French windows, but I had taken no more than three swift paces when a shriek stopped me.

The shriek was from Colonel Treppham. He had sprung to his feet and was standing behind his desk, his shrunken frame trembling as with the ague, glaring at me with a strange expression of baffled rage and terror.

"Stop!" he croaked hoarsely as I turned. "Where are you going? Why are you going that way?"

I looked at him in puzzled amazement for a moment, then answered:

"I told you where I'm going—to the police. I am going through the French doors because Pandora is outside and I want to talk to her."

"No—no!" he said, his voice suddenly changing to an oddly wheedling note. "Don't go that way. Go out the hall, through the main door. You will meet her on the way in..."

Had the man gone starkly insane? He wasn't concerned about what my mission out-of-doors might be—he only wanted to be sure that my route lay along a certain path...

And then, as though a faint voice had spoken in my brain, I began to feel that I was beginning to understand something. A far, quiet bell was ringing its muted tocsin as I stood there and watched him. Then, suddenly I swung about again and headed for the French doors.

Three more steps I had taken when his voice stopped me once more.

"Stop—stop, or I'll shoot!"

There was no longer any terror or rage in his voice. Only quiet deadly command. I knew that if I wanted to live two seconds longer I must obey. Slowly I turned about and faced him. From somewhere—most probably his top desk drawer—he had procured a pistol. He held it on me unwaveringly, his face tight and drawn with tense self-possession. He stood looking at me for a moment, a cold, black fire burning deep in his eyes. Then, still holding the gun upon me steadily, he bent over and fumbled with the other hand out of sight beneath the desk. As he straightened, my ears caught a distant, faint humming noise—as though a thousand bees were swarming out of a hive.

"No," he said, "I think you will follow my suggestion. Allow me to escort you out of the house as a host should—through the front door!"

The bell in my brain was clamoring stridently now. And I knew that as surely as I followed his directions I would be walking to my death. I sensed that there was a mysterious and deadly reason for his wanting me to leave his house by the front door—as innocent and harmless a procedure as that seemed to be. But to disobey meant death, also—that was very clear. So, with the cold sweat beading my forehead, I turned and walked slowly from the room, he falling in my wake and following me with steady, measured paces.

AS I turned into the hallway the humming sound grew

louder. Somehow, I felt that I had never heard such a

terror-inspiring sound in my life. I could not determine

from what direction it came—it seemed to be all about

me—and I had no idea what it signified. But I knew

that in some manner it signified the end of my life.

Mentally I measured off the steps between myself and the door. When I should have reached that door I would open it into the country where four men had preceded me. Would I know, then, how I had died? Would I know—

I was still some paces distant when the door swung suddenly open—and Pandora swept into the hall. I came to a sudden halt; unreasoning but over-mastering fear for the sake of my sweetheart drowning concern for myself. And then, behind me, there was a terrific scream.

"Pandora!" shrieked Treppham. "Pandora! For God's sake, stop where you are!"

"Why—what...?"

Affrighted amazement flew into Pandora's face as she stopped and gazed at us. I saw her eyes sweep past me, saw her start as they fell on the gun in Treppham's hand. Then her small mouth stiffened, her blue eyes narrowed.

"What in the world does this mean, father?" she said, and started walking toward us determinedly.

"No—no—Oh, God!" Suddenly Treppham sprang forward. He swept past me, darted at his daughter and grabbed her by the shoulders, thrusting her back until her shoulders were against the door. It was my first impulse to follow, to make sure that Treppham meant her no harm. But I sensed that he did not—that he was saving her from a fate he had intended for me. I stayed where I was.

Treppham swung about, still holding Pandora against the door.

"Carey—" he called to me—"beneath the top drawer of my desk—there is a tumbler-switch. Go and throw it over—quick!"

I leaped to obey him, sensing that some diabolical engine of death was causing that humming, and that it was controlled by the switch he mentioned. I found it within seconds, and as I flipped it over the faint humming sound ceased.

There was the sound of a falling body, and I rushed back into the hall to find Pandora bending over the motionless, prone body of her father.

BUT Colonel Treppham had only temporarily succumbed to

excess of emotion and old age. He still had six hours of

life left to him, and before that six hours expired he

had told his story to Pandora and me as we stood at his

bedside.

"I never knew of the taint in our blood until after Corliss was born," began Colonel Treppham. "It is true that I had strange, unnatural yearnings when I was a youth. I got into a serious scrape in Bangalore, when I was only a subaltern in the British Army, because of a native girl whom I nearly killed. A friendly senior officer got me out of that with considerable trouble, but it taught me a lesson that I never forgot. I was able to control my unnatural appetites for human blood and sadistic violence, and finally to subdue them completely. I never realized, really, that the experience I had gone through was different from what all young men have to endure with the onset of puberty—until Corliss showed me the demon that slept in Treppham blood.

"I was stationed at Karachi when the first incident occurred. Corliss was five years old. She had a little white puppy which had been given her by the commandant of the post, and to which she seemed tenderly attached. But one day I returned to find my quarters a shambles. The puppy, bleeding profusely at the neck, was running about the place, whimpering and wailing. Corliss sat in the middle of the floor watching its pitiful antics with eyes that glowed with the fires of hell. Baby that she was, she seemed possessed of the very spirit of Satan in that moment—and like a black tide realization flooded over me. For her face was smeared with blood...

"Her mother was away. Hastily I washed her and changed her clothes. I caught the puppy and bound up his neck, explaining to my wife, when she got home that he had been bitten by a bush-rat. Since that moment my life has been a constant and unrelenting task of keeping the beast in my daughter under control. There were other incidents. I managed to hide all of them from my wife save one;—and the shock of discovering that was what caused her death.

"But the thing I knew must ultimately betray Corliss—and me—was the change that came over her victims after she had attacked them. Those, that is, that survived.

"The puppy, after it got well, one day, went suddenly mad. It raged about the house snarling and yapping hideously. Before it could be caught and killed, it had bitten our native maid-servant in the ankle. She was inoculated immediately with an anti-rabies injection, but she went mad, anyhow. However, although it was considered such by the authorities, it was not rabid madness that attacked her. She was found dead in the jungle of snakebite, but in her arms, his throat lacerated and torn by her teeth, was a young native whom she had lured to that place.

"When I was retired on a Colonel's pay I came to the United States, bought this estate, and hoped that here, in this secluded place, I could defeat the curse that was upon my house. Years passed without incident, and I thought that I had succeeded. Then I found that Corliss was having clandestine meetings with young men—and the terrible shadow swept back over my heart. I knew it was worse than useless to remonstrate with her, and at last I hit upon a desperate and criminal scheme that, I hoped, would divert suspicion from us long enough for me to settle my affairs here and move to some even more remote spot.

"I had recently purchased a short-wave electrical therapeutic outfit for the treatment of a nervous complaint, and being thoroughly schooled in electrical science, I knew that the waves of this machine could be adjusted to a length and frequency that would have a lethal effect on human tissue. I arranged the machine with opposite poles on either side of the hallway, constructed and installed an intricate system of selenium cell detectors on all the windows and doors. But I could not remain awake twenty-four hours a day—and there was no one to whom I could entrust my horrible secret. Finally, I was driven to the last recourse. I lay in wait for the young men whom I knew Corliss was seeing most frequently—who, presently, would fall completely under her spell and relinquish their blood to her, thereby becoming beasts who would spread their curse like a contagion through the world. I gave them a cleaner and a painless death. They were doomed, anyway—and the ghastly taint that would, if they lived much longer, poison their blood would not be visited upon them. I feared that you, Ralph—that you, too—"

His eyes, already glazing, turned toward Pandora, and my eyes followed his. Instinctively I reached out my arms toward her, thinking she was fainting. But she stood there, white as the sheets on the bed, merely looking at her father with an expression of unutterable horror and fear on her delicate features.

And I knew, then, what she feared. She too, as she had said, had Treppham blood in her veins. She, too, was under the curse. That she would never consent to a union which might result in... the terrible curse of the Treppham's being perpetuated...

NEVERTHELESS, I persuaded Pandora to go with me, two

days later when I left The Beeches, never to return. I

saw no need to explain matters to the police. It would

not bring back to life four bodies now in their graves.

What they questioned me most closely about was Corliss's

disappearance—for we found, shortly after father

died, that she was missing. There was nothing I could tell

them that would have been of any aid, however, for of

course, I did not know where she had gone.

And, in time, I argued Pandora out of the belief that her blood was tainted—won over her fears and made her my wife. But though I love her with a tender passion, I sometimes feel a strange quality in her response to my love-making, and I feel an eerie dread that, eventually, the curse that is upon the house of her father may become horribly active once more...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.