RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

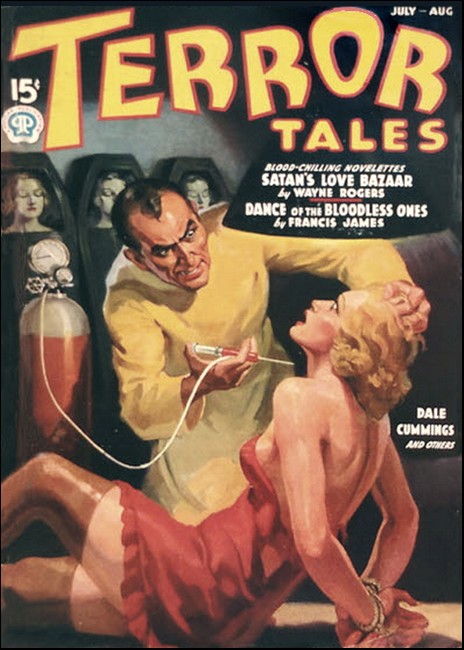

Terror Tales, Jul-Aug 1937, with "I Am a Mad Artist!"

I knew that when the girl I loved insisted upon posing nude for me I would again become the killer-beast that slumbered in my family's blood...

IT was not only that I was facing professional and financial ruin—I could have stood that almost with equanimity. The thing that was driving me slowly mad—that was making a surly, anti-social hermit of me—was the knowledge that I was no longer fit for human society. Nor, indeed, was I fit to associate even with animals—whose bestiality was less bestial than mine because with them it had, after all, at least a natural cause.

It was an unbearably hot summer. The stifling bodily anguish, added to the torture of my mind and spirit, made existence seem desperate and worthless. Yet I could do nothing to gain ease. My commissions had fallen off steadily for over a year. I was reduced to barely enough money for my food, was able to purchase materials only through the generosity of such few friends as had stuck by me. Naturally I lacked the money to leave the city in search of the mountain or ocean breezes which might, in a measure at least, have restored me to normal.

I had nearly given up hope. I was thinking more and more of taking one of the only two avenues of escape which seemed open to me: should I surrender to a hospital for psychopaths, or commit suicide? Then suddenly one day the director of the Wyhe Museum called on me and gave me a commission for a life-size figure.

When he described what he wanted I very nearly refused the commission. It was to be of a woman, a figure typifying slumber... A woman! That meant a model—a model posed in the nude! I dared not do it... And on the other hand I dared not refuse. It was my last chance to save myself, my sanity, my life... I accepted the commission...

But I did not engage a model. Somehow, I got enough money together to purchase clay and material for the armature and went to work. I assembled such photographs as I had, borrowed more, bought a few. I would, I said, turn out this job without a model. It had been done before...

Yes, it had been done before—but not by me.

Some painters, a lesser number of sculptors, are able to turn out successful work independent of models. I had never been able to do so. My hands would betray me unless my eyes were guided by living lines. The clay would refuse to throw off its heavy materialism and become something very near to life itself, unless the pattern was there before me every instant. In my case, at least, the hair-line division between gross matter and vibrant illusion of nature was too fine to admit of any groping in the dark...

And for over a year I had been trying to prove to myself that it wasn't so—with no success whatever!

It is true that, for a time, I produced some respectable male figures—in particular a group of old fishermen which gave me a fair monetary return, and which I was not ashamed to sign. But my talent had always been chiefly exemplified in the female form. Such reputation as I had sprang from my ability to imbue clay, stone and metal with the singing, rounded contours of girlish youth. If there is such a thing as inspiration, I was truly inspired only when engaged in such work.

So—commissions had fallen off; customers came to my studio no more; and the critics professed to mourn my death as an artist.

Of course, I had not given up without a struggle; had not dispensed with the models so necessary to my art without the frightful lesson, the appalling realization that, indeed, I dared not use them. And if I live for a thousand years I will never forget that lesson that I learned so bitterly and with such self-loathing...

MY father's brother, old Uncle Conrad, had died fourteen

months before this story opens. I came in answer to a wire

from his daughter, my cousin Lucy, and found him all but

beyond the portal of death. His old arteries had betrayed

him at last, and he was feebly struggling in the last

throes of arteriosclerosis. But in spite of his pain, his

knowledge that he had only a few moments more on this

earth, he insisted in talking to me alone. He ordered out

Lucy and the doctor, though the latter went protesting that

the patient must not talk. Uncle Conrad beckoned me close

to his side. In faltering syllables he whispered a tale

of horror into my ear; told me what I must do to avert a

terrible tragedy from entering my own life; gave me certain

instructions and made me give him my solemn word that I

would carry them out.

Then he died in horrible agony, and looking into the death mask that had been his face, I saw an exemplification of the horror he had described to me—saw, in short, what awaited me in the end, because I was of his blood and had sprung from his line...

I left his house, and later carried out part of his instructions by searching his city residence until I found his diary. And then it was that I learned of the doom which lay in wait for me, in all its ghastly detail...

Yet so resilient is the mind of youth, so over-weeningly self-confident are young men of good health and active lives, that, shocked as I had been, I soon shook off its effects. After a few days of brooding I roused myself, told myself that this thing could not happen to me. It might be true of everyone else of my blood—but it would not be true of me...

Nevertheless, I took certain precautions. I procured a model who had no connection with any agency. Fortunately, one appeared at my door at the very moment I was about to go out searching. Many girls dispense with agents in this way, and make regular rounds, calling personally on artists and sculptors until they have built up a clientele. So I engaged Marietta.

She was not a particularly attractive girl, so far as her face was concerned; but she had a perfect "sculptor's figure"—full-blown, deep bosomed, with a wide pelvis and full-fleshed hips. I was well pleased to have obtained such an excellent model independently of an agency.

Work began auspiciously. I was inclined to smile inwardly at the forebodings and fears arising from the things my uncle had told me—but not for long. By imperceptible degrees those fears began creeping back into my brain. And finally the horror burst upon me in its full force. I know now that it was not until that moment that I actually realized the full ghastliness of what I had learned. The human mind is constructed in such a way that it will not permit a psychic shock of too great force to gain immediate entrance. To preserve itself, it must needs make the too dreadful, the excessively terrible, unreal for a time—until the mind has had time to readjust itself and absorb the shock of the awful knowledge.

Thus, it was only now that I truly realized that my uncle had slain his wife in the throes of a terrible sexual mania. It was only when I, myself, began to feel an ominous stirring within my veins that I truly absorbed the frightful knowledge that my father had killed my own mother in the same manner...

But that realization, that absorption of horror, passed in the flashing of a moment. It was as though a crevice had opened in my mind, admitted the horrid facts, and immediately sealed it up again. There was left a slow burning in my brain, a fiery pulsing of the blood in my veins—and I dropped the spatula which had been in my hand and advanced toward the dais upon which the model reclined.

The girl looked up at me as I stood over her with something quickening in her eyes. It was not fear—not at first. Most models are exemplary enough young creatures. Their morals are as good or better than most girls'—and the ones who take their profession seriously will permit no undue familiarity on the part of the artists they work for. But naturally there are exceptions. Marietta was such an exception...

What followed was a nightmare of bestial passion and, God help me, of brutal cruelty. When sanity returned I was confronted with the full realization of the sort of animal I had become—was confronted, also, with the nude, blood-spattered body of my first victim...

HOW I obtained medical aid for the model, how I nearly

impoverished myself at one stroke in paying her off and

sealing her lips, has no bearing on this story. But I knew

from that moment that I would never again dare to use a

living model. I had escaped becoming the foulest sort of

murderer known to the human race by the most perilously

narrow of margins.

When I could permit myself to think of it afterward, I wondered dully why this mania had not stricken me before. I had seen literally hundreds of girls in the nude, had worked from models all my artistic life, including my school days. Naturally I had had a few amatory experiences, yet nothing remotely like this had ever happened before. Had the suggestive influence of what my uncle had told me done the work? Or had the curse just descended suddenly, independent of the knowledge I had gained? Uncle Conrad had warned me, indeed, that it would strike in this manner.

Not that it mattered. I had had sufficient proof of the fact that my blood was poisoned with the same taint which had been in the blood of my progenitors. There was one way and only one way for me to avoid the horror which had cursed the men of my line. I must avoid woman as I would the plague, even if it meant lifelong hermitry or entrance into a monastery. There was no middle course for me, and I knew it.

Yet, to my eternal shame, I must confess that I could not bring myself thus to renounce all that made my life worth living. I still had a few remnants of self-respect, even of self-confidence, left. I resolved that I would go on as best I could, working without models, and at the first sign of a recurrence of my horrible mania I would either voluntarily enter a hospital for psychopaths, in the forlorn hope that modern psychiatry could cure me—or I would take my own life.

But, of course, when the horror recurred I did neither. Does a rabid dog confine himself to a kennel? I shall never live long enough to expiate the contemptible weakness which I displayed in not following the dictates of such manhood as was left to me. Nor can I ever truly hold up my head among my fellowmen—because, even now, I lack the determination and courage to take my own life...

The summer, I have said, had been cruelly hot. The city had become an inferno whence all who had the means had fled. I lingered because of my poverty—and because I would not resign myself to my fate.

For awhile I took some encouragement from the progress I was making with the new figure. I constructed the armature, blocked the clay into it. With mallet and knife I shaped it roughly to the form I had designed.

It was hot work. I was sweating like a draught horse, even though every door and window in my studio was wide open. Only occasionally would a faint breeze percolate in from the hall and give me a moment's respite. I worked far into the night; dropped, at last, onto a cot against one wall of the room, without disrobing. After a shower and coffee the next morning I was back at work.

Throughout the day I toiled, pausing only once for food which I threw together hurriedly in the kitchenette—and late that afternoon I reached the point beyond which, I knew with sickening certainty, I could not go.

I have always been a tremendously fast worker in the preliminary stages of a clay figure—and excessively slow in the final ones. After the form has taken its final shape, then begins the real work. Then it is that I throw aside my tools and begin working with my hands alone. And then it is that such genius as I may have begins to appear. But that touch—that vivid and life-like reality which I am capable of evoking—can not be drawn from my fingers unless the living flesh is there to awaken it.

For hours I struggled hopelessly, and finally black despair crept irresistibly into my soul. At last I threw myself upon the cot and buried my face with a groan in my clay-stained hands. I had been deliberately deceiving myself all along—I was beaten and I knew it.

Then, in that moment of retreat, temptation slipped insidiously into my brain. After all, it had been over a year since the grisly incident of the model, Marietta. How did I know that, having once come through an attack of the madness without having actually killed anyone—how did I know that I was not cured? Perhaps the curse struck but once. There was some basis for believing this might be the case, since my uncle's records recited no instance wherein a man of my line had killed more than once.

Ah, but I knew the reason for that. Some of them had had no opportunity—because they had been hanged for their crime. Others had secluded themselves in sparsely inhabited communities. Others, like my uncle and father, having successfully concealed the fact of their crime, had not remarried, and had sedulously avoided the company of all women save those of their immediate families.

Besides, it was not a curse in the sense that it was something of a supernatural nature, invoked by some ancient spell, or suchlike metaphysical nonsense; it was a definite taint in the blood of my line. A thing thoroughly understood and acknowledged by psychologists, sociologists, and ethnologists the world over...

I groaned again and lowered my hands from my sweat-damp face.

I HAD lain there on the cot for perhaps ten minutes,

agonizedly wrestling with my soul—struggling against

the temptation to go out and hire a model even though it

might mean her death, my own execution, and the eternal

damnation of my immortal soul. I had heard no sound, sensed

the presence of no other person in the room—and yet,

as I opened my eyes and let my apathetic gaze wander over

to the model's dais, I saw that I was no longer alone. A

model was lying on the dais, nude, in the precise pose to

which I had shaped the figure I had been working upon!

I leaped to my feet with a choked cry, and involuntarily brushed my hand across my eyes. It was not an illusion; there was actually a naked girl lying up on the dais. She had entered, disrobed, and assumed the pose indicated by my figure without my having heard a sound.

And then, as my vision cleared, an even more astounding fact smote my consciousness with an almost physical impact. The model was my cousin Lucy—Uncle Conrad's daughter!

MY figure, as I have said, portrayed slumber. It was the

form of a young girl lying supine, her face turned to the

right, eyes closed, arms raised so that the hands pillowed

the head, the left leg drawn up slightly and resting

against the right.

Lucy's form was perfect for the pose. Through the terror and stupefaction which seethed in my mind, I believe I realized in that very moment that subconsciously I had been visualizing her body as I worked. Indeed, throughout the whole of that terrible year I had mentally used Lucy's body as a model many times. In the past I had been tempted to ask her to pose for me; but naturally thinking she would be unwilling to do so, had refrained. And now, astoundingly, she was here in my studio, as self-possessed and expertly posed as any professional model!

I staggered over to the dais. "Lucy," I muttered. "What in the world—"

The girl did not even open her eyes. "Never mind, Jack," she murmured. "Go to work—and don't ask questions. Don't you see I'm embarrassed to death?"

"But—but you don't understand," I groaned. "I—can't, Lucy... I—I dare not—"

"Don't be silly," she said firmly, and opened her eyes just a trifle. "Go to work and stop talking!"

A moment longer I struggled with myself—then a sort of furious joy raced over my nerves. A year of arid struggle was behind me. The hunger which only an artist can know—the consuming craving to create in the image of his imaginings—clutched me with the accumulated power of all those sterile, frustrated months. With a choked gasp I whirled to the clay, began working with the fever of a fanatic who glimpses the goal of his dreams...

In the first few minutes there was room in my brain for nothing save a savage sort of exultation. My hands flew over the smooth surface of the wet clay, molding the insensate matter into the semblance of life, glorying in the sureness and confidence with which they worked, after the endless time of blind stumbling... And then the moment came when I knew that I must touch the living form of the model. My fingers must learn a contour from warm flesh before they could transfer it to the cold clay. As I straightened and looked at Lucy's white body a shiver of apprehension ran through my frame. Dared I tempt fate to that degree? Was I strong enough to withstand...?

Then it was that I noticed some thing which until that moment had escaped me. My attention had been directed principally about the torso of the figure, and consequently, the corresponding sections of the model's anatomy. I hadn't seen that Lucy was wearing a necklace.

To anyone unacquainted with the curious moves and psychological conventions of the world of artists it will seem strange—but it is nevertheless a fact—that an artist never thinks of his model as a woman unless she has on stockings, a necklace, or some bit of feminine apparel. Psychologists have long since proved that sexual stimulants are largely matters of convention and the conditioning of the individual. Thus Hindu women of the past veiled their faces, but exposed their breasts with perfect propriety—because, through some ancient twist of mass conditioning, Hindu men had come to regard the face as a sexual stimulant, and completely lost interest in female breasts as such. Only a few decades ago in all civilized countries the exposure of an ankle by a woman with any pretensions to the status of a "lady" was a matter of deep embarrassment to her—and of ribald delight to such males as witnessed the distressing accident. But what modern man can be seriously stirred by the sight of a mere ankle? So it is that artists, as they learn to accept the undraped female figure as nothing more than a tool of their trade, lose all interest in it as the body of a sexually attractive woman. But of course, the stimulus has been subdued rather than completely robbed of its power. As slight a thing as a casually worn wristlet may prove to be the catalyst which restores her seductive power to the model.

Lucy, in her innocence and ignorance, could not know that. She had probably forgotten that she even wore the necklace. But it was the thing which completely changed me in an instant from a reasoning human being into a ravening beast.

WITHOUT realizing that I had moved, I suddenly

found myself standing over Lucy's nude, white figure.

I glared down at her with burning, devouring eyes. I

feasted upon her nakedness, my body trembling with a

desire that was like liquid fire in my blood. My fingers

worked spasmodically, restrained from clutching her

soft form in a grip of remorseless savagery only by the

vestiges of control—of panicked and retreating

manhood—which were left to me. Then Lucy opened her

eyes.

I had expected to find terror there—and there was fear, lurking far back in their clear, blue depths. But there was something else in Lucy's eyes; something which I could not analyze, and yet which aided me for the moment to keep a grip on my reeling senses...

"Jack," said Lucy softly, "I love you—I have always loved you. If I must die now, I want you to know that. I came to you because I would rather die at your hands than live without you..."

For a long time, it seemed, the words meant nothing to me. It was as though they had come from Lucy's mouth and been printed on my brain—but I couldn't read them at first. Then, at last, their significance percolated through to my consciousness.

"Love?" I echoed hoarsely. "You—love me, Lucy?"

"Yes," she murmured, "I love you, Jack. Perhaps—" and a pitiable light of hope was in her blue eyes—"perhaps we can conquer this madness together... Maybe you can escape the curse of the Lawrences, with me to help—"

Then her voice trailed off and died in a whisper. Insanity was fastening its talons in my soul, and the beast was emerging in my face. The girl's eyes widened with a momentary access of fear; then assumed a calmness as a courageous resignation took its place.

"Very well, darling," she whispered, "if it is to be that way—"

But if she said anything else I did not hear her. A red tide had risen in back of my eyes, blinding me, robbing me of the last vestige of sanity. I heard a bestial snarl, and my retreating consciousness recorded the fact that it was from my own lips. Then I had swept Lucy's white, unresisting body into a savage embrace—and conscious thought deserted me...

IT was a waking nightmare which took the place of sanity

and consciousness. It seemed to me that I held in my arms,

not Lucy's little form, but a savage and fearful caricature

of my own. It was a body larger than mine, clothed in a

matted coat of rough fur, with the visage of an ape in

which a semblance of my own features were distinguishable

as in a cheap, distorting mirror. This beast bared fangs

like those of a hyena, gripped me in a suffocating embrace,

and lunged at my jugular.

I knew that to survive I must kill this other me—and my fingers fastened about the throat of the thing, tore at it with a viciousness equaling that of my antagonist...

It was then that I had a momentary flash of consciousness—of veridical sensation. Enough, at any rate, so that I wondered at the softness, the hairlessness, of that shaggy-seeming throat. It was like, my bemused senses told me, the throat of a young girl.

Then the moment of comparative lucidity passed, and I was again grappling with the beast that was I—and a savage joy was permeating my being. This being which I could fight with, which I could kill—why, it was the bestial half of me which was wrecking my life, ruining my career, making of me a thing unfit to associate with human beings! I would kill it, at once—stamp out every vestige of its foul life. Then I would be free. I could work again. I could marry Lucy who loved me—and whom I loved, I realized now. Why, I had always loved her! But I had been so bound up in my career that I had never realized it until, in her unashamed innocence and courage, she had come to me and avowed her love for me. It was because of her, too, that I would be able to subdue the monster who had been dominating my life. She had precipitated the struggle which I had been avoiding. It would be decisive—and I would be the winner. I never doubted that...

The beast, for all its ferocious appearance, was not such a powerful antagonist, after all. Its struggles were weakening already—and as they lessened, my own ferocity increased. Ah, there would be no smouldering spark of life in that savage carcass when I was through with it! My fingers searched for the jugular, fastened upon it with all the strength at my command, ripped...

It was as though the death of the beast had restored me to life—not the phantasmal, nightmarish life I had been living during my struggles with it, but real life, sanity, consciousness. Even before I opened my eyes I was suffused with such a sense of well-being and peace as I had not known since before I had listened to the horrible death-bed mutterings of my old uncle. Then I opened my eyes—and looked up into the tear-stained but smiling face of Lucy.

"Darling," she cried. "You've come back to me. You've won! Oh, thank God!"

My eyes fastened on her slender throat—on bluish, bruised welts which showed there against the velvety whiteness.

"Perhaps," I murmured. "Perhaps I have won—but at what cost to you, Lucy?... Are—are you all right, Lucy...?"

"Yes—yes!" she exclaimed. "It was bad, at first. I thought surely I was going to die, Jack. And then—then a look came over your face, a strange, triumphant look, Jack—and—and you released me. You fell to the floor, clutching your hands together as thought you were throttling something. And then, for a few minutes you lost consciousness, I guess."

I drew a deep breath and sat up. "What prompted you to come here?" I asked. "How did you find out about—me? Did your father tell you?"

"No," she said, "I moved into the town house shortly after he died—and one day I found that diary of his. I knew that he had told you something the night he died, and there was something in the diary about his fears for you—being constantly thrown in the way of temptation through your work. He was afraid to warn you, because it would involve the confession of his own guilt. His—his murder of—"

She paused with a hysterical sob, then continued bravely. "I knew what you were going through, and I found out that you had given up using models. Of course, I realized why. At last I could stand it no longer. I decided to come to you and—if necessary..."

But I stopped the rest with my lips. I pressed her sweet, slender body against mine and breathed a silent prayer of thankfulness for the supreme courage that God gives to some women—a courage far higher than that ever displayed by any man...

AND I, who am an arrant coward, can best appreciate such courage. If I had a modicum of it I would put this body of mine beyond the safe confining gates of death. For after a few weeks of living in a fool's paradise, I came to realize that my illusion of conquering the beast which dwells in my soul was, indeed, an illusion and nothing more...

In the meantime Lucy and I were married, and I went back to work with a joyous energy which promised greater things than I had ever done before, But not for long. One day, as she stood nude upon the dais, the madness came back to me—and I awoke to find her crushed in my arms, her senses having fled before the pain my savagery had inflicted upon her.

When she had revived she calmed my raging despair, tried to talk the matter over with me in a sane, sensible manner. She pointed out that the last two attacks I had sustained had each shown a decrease in magnitude compared to the first one—that on Marietta. It was obvious, she insisted, that I was gradually returning to normal. It was only a question of time until I would be completely cured...

But how can we be sure? I have consulted psychiatrists without number. They assure me that I probably have little to fear—that, indeed, I am on the road to recovery. But they seem puzzled about the beast. A dynamic illusion, they call it—and let it go at that. And at times, in the dead of night, I awaken in a cold sweat with the knowledge that the beast is not dead and will never die. That some day, he may return with renewed strength and conquer me utterly. And in that conquering will perish horribly the person whose life and happiness means more than anything else in the whole world to me...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.