RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

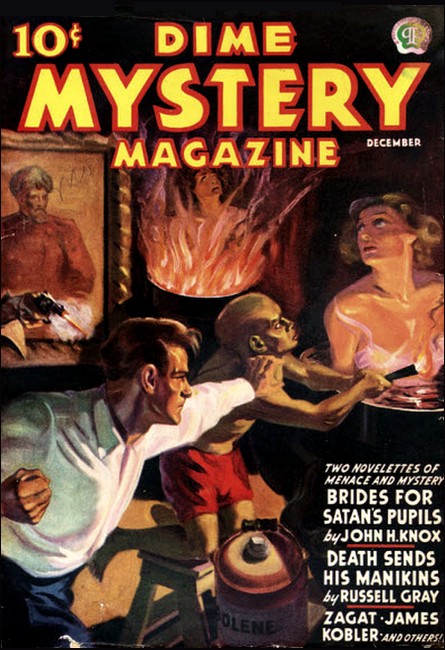

Dime Mystery Magazine, December 1937, with "The Cat and the Corpse"

What was the horrible power that caused the cat and the tramp to die—at my mere wish? And were these two strange deaths to presage a third, more ghastly tragedy...?

TO MANY people New York's Greenwich Village may be little more than a slum partially disguised in a few garlands of Bohemian tinsel; but to Muriel and me, during the first few weeks of our married life, it seemed a heaven on earth. But then, any place in the world would have been a paradise to us. We were in our early twenties, very much in love, and I was beginning to win recognition as a painter. There was really very little left for us to wish for.

Little to wish for, did I say? Oh, God—if only there were no such word as "wish" in the language. If only there were no such function of the brain as that of wishing. I don't know who said it—I can't even remember the quotation correctly—but some ancient philosopher warned young people against wishing for anything. "For," he said, "it will be your fate eventually to get your wish!"

No one can testify to the validity of that warning better than I... But to get on with my story...

We took a couple of furnished rooms—dignified by the landlord's imagination into an "apartment"—on Barrow Street. It was in a half-basement, but the rear room opened out into a small garden, and large leaded windows admitted a northwest light which was good enough for painting from about ten o'clock on. We couldn't have been happier in a duplex studio on Park Avenue.

We worked hard those first few weeks. I'd help Muriel get breakfast, and then wash the dishes while she dried them, because I couldn't get on with my work until she was through with hers. She was my model, you see. Muriel used to say that the only reason I married her was to save models' fees—which was one of the many silly little private jokes we had between us. The truth is, that aside from the fact that she was the only girl in the world I could possibly have lived with for any length of time, she was likewise the best model I ever saw. Tireless, imaginative, perfectly formed and with a face half nymph and half goddess, she was the answer to an artist's as well as a lover's prayer. When she came in answer to my call to an agency, that first time, and stood before me in the nude, I completely lost every shred of my artist's detachment and—But that's another story...

Yes, we were happy—almost foolishly so—for a time. And then we met the Count.

THE village always has had, and always will have,

a number of quaint inhabitants whose main function in

life seems to be to give it a tinge of slightly whacky

color. I remember one individual who went about, year-in

and year-out, in a shabby grey flannel suit, bareheaded,

and with a long white beard which was neatly divided into

two braids, and dangled to his waist. His specialty was

one-line poems. Then there was the old woman who painted

mountain landscapes using a weird combination of oils on a

background of tempera wash. She said this technique gave

her pictures a third dimension. She went barefooted the

year around and dressed exclusively in gowns made from

sewing together a number of bandanna handkerchiefs.

I had always regarded the Count as being one of these "characters." But he was more dignified than most of them, and his only eccentricity in dress consisted of a taste for "claw-hammer" coats, high-standing collars and Ascot ties. But his clothes were always freshly pressed, his shoes shined and his linen spotless. He wore a black Homburg hat, a waxed kaiserlich mustache and a small imperial. Muriel doted on him and openly flirted with him—just to tease me. He lived on the floor above ours. He had no visible profession or other means of supporting himself, but for a time we thought he must have an independent income.

We were disabused of that idea one evening when we came home and found him standing forlornly in the midst of his furniture on the sidewalk in front of the house. He had been dispossessed, he explained to us in a tone of dignified resignation.

I went in to talk with Jeffers, the landlord, leaving Muriel on the walk with the Count. I gave Jeffers a little money, got him to extend the Count some time on the balance, and then all four of us moved the Count's belongings back into his room. After that Muriel asked him down for a cocktail—and that's when the time of terror began.

IT was soon apparent that the Count was far more

eccentric than we had thought. In fact, he hadn't been in

the apartment ten minutes when I became convinced that he

was hopelessly mad. He dispatched the cocktail with a speed

that suggested he would be happy to have another, and while

I was pouring it for him, he began to talk.

"It is these little annoyances that take the joy out of living," he said. "Big troubles—great tragedies—occur infrequently. Perhaps they leave terrible, incurable scars behind them, but they happen to us rarely more than once in a lifetime. Meanwhile, life is made bitter, unbearable, by a multitude of minor irritants."

He got to his feet, and carrying his glass in his hand, walked around to a position from which he could see the canvas that was mounted on my easel. As he did so, he remarked carelessly, "Well—unfortunately I do not have it in my power to insulate my own life against these myriad pests, these carping landlords, insolent waiters, viciously selfish employers. But I promise you that when I leave your house, you need never fear such things again. You need only wish that they be removed from your path—and it shall be accomplished.

"Ah...! What have we here?"

He was gazing intently at the half-finished picture on my easel, and his question obviously referred to it—but it was the strange statement which preceded his question that held my attention.

"Pardon me," I said, "would you mind saying that again? I mean what was it you promised us regarding landlords and—er—other pests?"

The Count turned his deep-set but curiously luminous eyes upon me. "I prefer not to talk about these things," he said. "People of the western world are either cowardly—or genuinely skeptics. I've never been able to decide which. At any rate, they steadfastly refuse to believe in many things of which they frequently have visual, circumstantial and empirical proof. In my country—I was born in Bohemia—many things were taken for granted which are here regarded with derisive disbelief and scorn. You have doubtless heard of the 'evil eye'. Probably you have also read of warlocks, mandrakes, deeves, ogres and ouves. It goes without saying that you believe in the actual existence of none of these things."

The Count paused and turned his eyes back to the painting, but he didn't seem to be expecting me to answer him, and after a moment he continued.

"My father was a warlock," he said calmly. "He was hanged in the little town of Budweis in 1898, charged with seditious activities directed against the Austrian government. Actually, it was a modern example of witch-burning. He was believed to have caused the death of a number of government officials through exercise of his magical powers; but such a charge could no longer be brought publicly—even in Bohemia. After his death, the sexton of the graveyard was secretly given a large sum of money to exhume the body, burn it, sprinkle the ashes with holy water and re-inter the remains in a coffin containing a Holy Bible. But the sexton left the country soon afterward with double the sum he had been given by the city—and I came to America bringing with me the body of my father which I had reduced to ashes according to a method quite different from that which would have been employed by the sexton. The ashes of the body of a warlock—a true adept—are, you understand, capable of being put to many valuable uses by a neophyte of magic, such as I was at that time..."

I could see that Muriel was thrilled by this fantastic tale. She leaned forward, breathless with excitement. "Oh—h," she breathed. "Then what happened?"

The Count turned to her, his eyes lighting with obvious gratification at her enthusiasm. Gratification—and something else.

"My dear," he said, "I would not stretch your credulity too far. You see, you Americans have a very practical, but equally mistaken, habit of judging all power of whatever kind by the monetary results it produces. If I told you that I am capable of transcendent acts of magic you would not believe me—because, only today, you saw me ejected from my room for nonpayment of rent. Let us pass over the whole matter. As I said, I do not like to talk about it—especially when there are such far more intriguing things to discuss. Such as this picture—which, I believe, you posed for?"

The painting was a simple study of a nude reclining on a studio couch. Muriel had posed for it, of course.

I was beginning to be seriously annoyed without quite realizing why. And then, I did. The Count's eyes kept traveling back and forth between the picture and Muriel. There was a definite libidinous gleam in them, now, and he appeared as though he were trying to force his imagination to see her naked flesh through her clothing, as it was in the picture.

Rage boiled up in me. I went to the easel and deliberately drew the covering across it with a gesture which was little short of an insult. But the Count only smiled a trifle sardonically. He tossed off the rest of his drink, and then put his hand on my right shoulder in a gesture that seemed placating—as though he were wordlessly apologizing for his rudeness.

"I have been trying your patience with my boring tale," he said. "Believe me, I would not have spoken, had you not expressed curiosity concerning the death wish. I must be going, now. Thank you, again, for your kindness."

"The death wish!" I exclaimed. "Who said anything about—"

"I had not named it, before," interrupted the Count. "I have bestowed it upon you as a slight token of appreciation for the aid you have given me."

His hand slid down the length of my arm, and then released me. He bowed deeply to Muriel and went to the door. He turned, then, with his hand on the knob and said something else, but I can't reproduce it, even phonetically. It was in some foreign tongue, and even the sound of the words seemed to disappear from my memory as soon as they were spoken. Then he made a strange sign with his fore-finger, his little finger, and his thumb. He bowed again. The door opened and closed—and he was gone...

As soon as he had disappeared my hand rose, half-unconsciously, and began brushing at my right sleeve. I looked down at it and saw that the sleeve was covered from shoulder to cuff—on the portion the Count had touched—with very fine, light-grey ashes...

DURING the rest of the evening I was in a curiously

irritable mood. I confess to a disposition which is not of

the best, but usually I have good cause for being disturbed

to the point of giving outward evidence of temper. It was

not so that night. I felt rage, inchoate, unreasoning, and

boiling within me. I told myself that I was vexed with

Muriel for having encouraged the Count. She had made eyes

at him. He wouldn't dare to have looked at her in the

manner he had, if he didn't think she would welcome his

advances.

And I knew that was all nonsense. I wasn't angry with Muriel—or even the Count. I was—just angry.

Sounds silly, doesn't it? It was something more than that—it was dreadful. I felt that I must be going mad, that I was being possessed by some fiend from hell whose only emotion was senseless, blind rage against all things. I wanted to stand on my feet and yell, curse, storm about the apartment and break things.

But I held onto myself until that cat squalled outside the window in the garden.

The good Lord knows there was nothing unusual about that. The Village must harbor at least one cat to every human being—and if a night passes without a regular chorus of yowling in one's backyard, it is little short of a miracle. I never paid any attention to it before. This time I jumped to my feet with a curse. "Damn that cat!" I yelled. "I wish it were in hell!" I picked up a heavy cloisonné vase and hurled it straight through the closed window, shattering the leaded panes into a thousand fragments. The yowling ceased.

Muriel gave a little scream and stood there looking at me as though she thought I had gone suddenly mad. No one could blame her for that. I felt ashamed of myself, but I still felt rage burning within me—and I felt a nameless terror gripping my heart. I snarled something at Muriel and threw off my clothes and got into bed. When Muriel crawled quietly in beside me, later, and timidly asked me what was the matter, I turned my back to her and refused to answer. I went to sleep and had indescribably horrible nightmares.

The next morning the spasm of senseless, causeless rage had passed—but another emotion had come to take its place. The terror I had felt the day before, caused by the rage I couldn't account for, remained—magnified a hundredfold. There was no more reason for this than there had been for my anger, at first. Then there was.

There was a dead body of a cat on the floor by the broken window. Its head had been horribly crushed in. Outside, in the garden, laid the cloisonné vase. It was unbroken, but its bottom was smeared with blood. My random wild throw had hit the animal square on the head! That was remarkable enough—but how had the beast gotten inside the house? That I had not killed it immediately, and that it had crawled over the window ledge and fallen on the floor before dying seemed the only possible explanation. An explanation which was given weight by a stream of blood which ran in an unbroken thread from the vase to the spot where the cat lay. But how it could have traveled that distance with its head crushed in was more than I could figure out.

I didn't try. I called up the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and they sent a man around to get the carcass of the cat. The next morning the dead cat lay in the place where I had first seen it—under the window.

In a kind of daze of horror I called up the S.P.C.A. again. The woman I talked to sounded incredulous when I said there was another dead cat in my apartment, and that I wanted it taken away. I didn't dare tell her that it was the same cat—but I did ask her what had been done with the first. She said, "Why, it was disposed of, of course—buried." And she added, "By the way, Mr. Benton, we have means for disposing of all unwanted animals. And we do it humanely and painlessly." She emphasized the last words significantly. I mumbled that I hadn't killed the cats—that someone was playing a horrible joke on me. She sounded mollified and advised me to notify the police. The same man came around and got the cat. He looked at me queerly as he took the carcass and stowed it away in his burlap bag. I watched him through the front windows after he had gone out the door. He put the bag in the back end of his little truck and drove away. Muriel stood at my side, her cold white hand clutching my equally frigid one. "What does it mean, Robert?" she whispered. "How could such a strange thing happen—and why should it happen to us?"

There wasn't any answer to that, but I tried to put the thing in an amusing light, for her sake. "The cat came back, you know," I laughed. "The cat always comes back, they say." My laugh was a strange sound, more than half hysterical. Muriel looked at me oddly, lines of worry marring her white forehead. "I don't understand," she said. "Something has happened to us... I don't understand it."

JUST before daylight the next morning I awakened

with a foul stench in my nostrils. I didn't have to look.

I lay there in bed and it seemed that my whole body was

immersed in that horrible smell of death. I knew that

the rotting body of the cat I had killed lay under the

window.

Muriel was still asleep. After awhile I got up and took the carcass of the cat out into the garden. I dug a hole under the acacia tree and buried it. Then I came back and started boiling a pot of coffee on the stove in the kitchenette in the hope that its odor would drive out that other odor before Muriel awakened. I don't know whether it did or not, but Muriel said nothing. She was very quiet during breakfast, and immediately afterward I told her to pack a few things in a suitcase. "Let's go up and live at the Central for a few days," I said. "This—this place is getting on our nerves, I think. It will do us good to get away for awhile."

She assented quietly. It was obvious that she knew what had happened.

The Central is on Fifty-Ninth Street, on the south boundary of the park. I went over and tried to sketch the animals in the zoo, the people who sat on the benches. It was no good—I couldn't work. I kept seeing a vision of that horrible dead cat lying on the floor under the window in our Village apartment, kept smelling the dreadful stench of its slowly decomposing carcass. Then a strange thought came to haunt me, and to add a weight of eerie dread to what was already grotesquely inexplicable and unreal: I remembered that before I had thrown at the cat, I had wished its death. I remembered, too, the fantastic words of the Count—the "gift" he had given me: the death wish!

Was it because I had verbally consigned the cat to limbo that it had died—or had it been my miraculously accurate shot with the vase?

Then, irritably, I tried to banish such notions from my head. I was being a weakling, I told myself, to let my nerves get the better of me in this fashion. I resolved that I would get to work and forget all the nonsense that was making havoc in my brain.

Nevertheless, the second day at the Central I began to feel a recurrence of that causeless rage which had led to my killing of the cat. I became irritable, venomously disagreeable. Muriel grew quieter in proportion. Her attitude rasped on my nerves more than if she had upbraided me for my senseless ill humor. One day, as we were walking down the Mall, she made some innocent remark—I've even forgotten what it was, now—that threw me into a paroxysm of rage. I turned on her savagely, half raising my hand as though to slap her—and at that moment a drunken bum lurched across the broad plaza and collided with us.

Instantly all my anger against Muriel was turned toward the helpless drunk. I seized him by the slack of his coat and smashed him mercilessly in the face with my left fist. He crashed over backward onto the hard concrete, his head making a dull, sickening thump as it hit, and lay still.

"There, damn you!" I snarled. "I hope that split your skull wide open!"

Then I stood there for a moment, gazing down at that pitiful, bedraggled body, while terror swooped down into my heart like a black vulture. I turned to Muriel and grasped her wrist.

"We—we've got to get away from here," I mumbled thickly, and began dragging her toward the south entrance of the park.

Muriel was sobbing, by this time. "Oh, no, Robert—we must take care of that poor man. We should call an ambulance..."

"The police," I muttered, "they'll pick him up. He's all right. Come on!" And I jerked at her wrist with savage insistence. Weeping, she was forced to acquiesce. It was about six-thirty and few people were in the park—none at the scene of our encounter. Rapidly I towed Muriel out of the park and back to the hotel.

With feverish haste I packed our belongings while terror writhed in my brain like a hissing serpent. I hustled Muriel downstairs and paid the bill. The doorman summoned a taxi for us and we headed toward the Village and home.

I suppose it was the blind, instinctive impulse that turns all terror-beleaguered human beings homeward. It was only as I was paying off the taxi driver that I realized what I had done. But now that I was there, a fascination more powerful than any terror was driving me through the door.

"Muriel," I said, turning to the white-faced, trembling girl, "we're all out of cigarettes. Will you go down to the corner and get a few packs? I'll go in and—"

"No, Robert." Muriel grasped my arm. "I'm going in with you, dear. I won't let you face it alone."

I wrenched my arm out of her trembling grasp.

"Did you hear me?" I snarled. "Go get some cigarettes. Hurry!"

The girl stared at me for a moment with tear-filmed eyes. Then, with a broken sob she turned and started walking slowly toward the corner. I picked up the bags and entered the house.

Even as I stood there in the hall fumbling with my keys the horrible stench was carried to my nostrils. Yet something drove me on, forced my unwilling hand to thrust the key into the lock, drove me to throw open the door and enter that accursed room.

For a moment I stood there in the darkness, swimming in a sea of sickening stench. Then, almost without volition my hand reached out and threw over the tumbler switch...

Perhaps the reason I did not become a raving maniac in that instant was that I was partially prepared for what I saw. Some black and fateful foresight had whispered the truth in my unreasoning subconscious brain before that merciless light revealed the thing that lay in my apartment.

Over near the window lay the foul, vermin-infested carcass of the cat. In the middle of the floor, his head lying in a pool of clotting blood, lay the bedraggled, soiled body of the drunken tramp I had knocked down in the Mall not an hour ago. He lay in precisely the position he had fallen, there on the walk. Already the miasma of death arose from his body and mingled with the unendurable fetor of the rotting cat.

I staggered backward and out of the door. I flung it shut behind me and leaned against the wall of the foyer, my senses whirling in a sick maelstrom at the bottom of which my soul was drowning in inexpressible horror. At last I summoned strength to lurch out of the hall onto the sidewalk and signal a taxi. I had the driver wait until Muriel emerged from the corner drugstore. Then we drove down and picked her up. She entered the cab without comment. She asked no questions. She knew what had happened. Once more the death wish had been fulfilled...

I OWN a little summer cottage far out on the

Atlantic side of Long Island. It was hardly the place for

me to seek sanctuary from the police, for many people in

New York knew that I owned it. But somehow I knew that I

was not fleeing the police. Somehow I sensed that I must

face something far worse than a homicide charge—and

that it mattered little where I went. I would have to face

it anyway, eventually.

We got out of the taxi at the garage where I kept my car in dead storage during the fall and winter. It took some time to have the tires inflated, fill the machine with gasoline and oil and have it greased, but at last we were ready. Still Muriel asked no questions. We got in and drove down Fourth Avenue to the Lower East Side. We crossed East River at Manhattan Bridge and turned north through Long Island. We passed through Patchogue about two in the morning, and a half-hour later I drove the car into the little garage behind our cottage.

The first thing I did when we got into the house was to snatch a half-empty bottle of Scotch from the buffet in the dining-room and down a tremendous drink. Carrying the bottle I went into the living-room and sat down in front of the cold fireplace. Muriel snuggled up beside me and I put my arm around her and closed my eyes.

As the raw liquor burned in my vitals the infernal kaleidoscope of the past few days whirled in my consciousness like a living nightmare. What, in God's name was the meaning of it all? Had it really happened—or was I the victim of some unimaginably drawn-out dynamic illusion? Had I gone mad, and were these horrible events only the visions of a crazed, tortured brain?

But I knew I was here, in my little cottage by the sea. What could have brought me here but the grisly sequence of scenes which burned in my memory like biting acid? How else could we have gotten here...?

Muriel disrupted the chaos of my thoughts by gently disengaging herself from my arm. She stood up as I opened my eyes and looked down at me with a small pathetic smile.

"You're tired, darling," she said, "and so am I. Let's go to bed..."

She unbuttoned the front of her little sports dress, stepped out of it, and stood there in her brief panties, brassiere, and dusty-tan hose. She reached out her arms toward me in a tenderly coaxing gesture.

For a long moment I sat there glaring at her, locked in a rigid paralysis while a volcano seemed to be exploding in my brain. For the tide of savage, primal lust which flooded over my senses at sight of Muriel's provocative near-nakedness was like nothing so much as an explosion in the suddenness of its onslaught. Then the bottle, which up to that moment I had still been grasping in my right hand, fell from my grip and thudded to the floor. I surged to my feet with an animal-like growl arising in my throat.

As I sprang toward her, Muriel shrank back before the beast that glared out of my eyes at her—and the spectacle of her sudden fear lashed my lust to a hotter flame. The rage boiled in my brain and mingled with the lust, so that they were one, and I wanted to beat and torture that slenderly rounded white body as I forced it to my will. I grabbed Muriel roughly by her arm, ripped the brassiere savagely from her breasts. I crushed her in my arms with a vicious strength which must have half suffocated her, and then I was clawing brutally at the brief covering about her loins, ripping it from her hips as my fingernails gouged deep scratches in her silken skin.

Then I flung her from me with all the furious strength of my frenzy, and she crashed to the floor half way across the room and lay there, stark naked, save for her stockings, moaning softly and half unconscious.

What happened after that is partially veiled in the merciful mists of drunken oblivion—but only partially so. The scalding memory of Muriel's tortured face, of her pain-wracked, writhing body beneath me, returns at times to sear my brain with its undying fire. There is the memory, too, of a brutal, criminally heavy blow, as I growled a curse: "I wish you were a lifeless corpse...!" And then the dreadful, final stillness of that tender white body. There is that terrible, ineradicable memory—and after that, nothing...

NOTHING—until my eyes slowly opened and the

knowledge slowly infiltrated into my consciousness that day

had broken. I was lying on the floor of the living room. I

was cold and stiff in every joint. My head felt as though

someone had been using it for an anvil.

I thought, for a moment, that I was back in the studio on Barrow Street, and a slow shudder shook my numb body. Then I knew that I was in the beach cottage on Long Island—but the impression of identity with the Barrow Street place remained in my mind.

After awhile I realized the reason for this, and with that realization black terror gripped my heart with icy talons. There was a horrible, indescribably penetrating stench in my nostrils—the fetor of decayed, maggot-riddled flesh.

I lurched to my feet, and there was but one thought in my mind: to put this place as far behind me as the limits of the earth would permit. And then, even as I staggered toward the door, the knowledge that Muriel wasn't in the room—and a vague, half-formed memory of some of the events of the preceding evening—lanced into my consciousness. Deliberately I closed my mind to the rest. I could not think of it, yet, without plunging headlong into the depths of shrieking madness. I turned about and made my way up the stairs toward the studio on feet which seemed to sink deep into clinging mire at every step.

As I neared the room the horrible stench grew stronger. I was sick with the horror of it; weak with dread of what I should see when I had tracked that foul odor to its source. And it was not the unearthly fear of finding the putrescent body of the cat I had killed—that revenant, rotting corpse which would stick with me all the days of my life, like the Ancient Mariner's albatross. It was something far, far worse than that. A something, I knew, which would drive me into permanent madness the moment I found it. And I knew, also, with a dreadful, hopeless finality that I would find it...

Everything I had raised a hand against for the past week had died. And last night I had struck Muriel...

As my lagging footsteps drew me nearer that dreadful room, I became aware of something besides the awful odor that emanated from it. It was a sound, hardly human, yet more human than anything else—a sort of liquid mumbling, a muffled crooning, like that which might come from the lips of an idiot child with a new toy...

Unconsciously I rose on my toes, crept silently forward, while the stench and the mumbling drove blazing spikes of horror into my heart. Then, suddenly, I stood under the lintel of the studio door.

At the sight which greeted my burning, distended eyes something snapped in my brain, and for a second I swayed in blank unconsciousness. But it lasted no more than that one instant—and then a crystal clarity surged into my brain, and it seemed to me that for the first time in a week I was in full possession of my faculties, once more.

The ever-present corpse of the cat was lying under the studio windows—but I caught sight of that only out of the tail of my eye—realized its presence with only a fraction of my brain. It was the ghastly tableau in the center of the floor which drew my eyes like a horrible lodestone, and held me rooted there with the paralysis of numbing shock.

Muriel's nude, limp body lay half on the floor, supported in the arms of the tattered, unshaven tramp I had struck down in the Mall of Central Park the day before. The vagabond, hatless, the back of his head smeared with clotted crimson, bent over my wife's white, still body, mumbling disjointed, half-inarticulate phrases of lust while his dirty fingers pawed her unresisting, helpless body with rabid passion.

At that sight all madness was swept from my brain, and a cold, murderous rage—very different from the causeless, blinding impulses of wrath which had periodically submerged my intellect during the past several days—swept over my nerves like a dash of cold water. This might be a dead man making unspeakable love to the dead woman who had been my wife, but that made no difference to me. It was enough that Muriel, whether alive or dead, was being violated. I sprang to action with a roar which sounded, even in my own ears, like that of a charging tiger.

THE tramp dropped Muriel's body precipitately and sprang

to his feet. In his eyes, as I dove at him, I saw first an

inarticulate terror—then, quickly supplanting it, a

calculating cunning. Before I reached him, he croaked:

"Don't touch me, murderer. We are dead. You killed us with your death wish—and we shall haunt you forever—"

But he had time for no more. I was upon him like a rabid puma, and he went down beneath my onslaught like a nine-pin. As he hit the floor, his hair seemed to leap from his head; but as I dragged him to his feet and sent another blow crashing full into his mouth, I saw that he had worn a wig, and that beneath it was a full head of coal-black hair.

Then, as he lay senseless on the floor, I went to work on him with a handkerchief.

As soon as I had wiped the greasepaint from his upper lip I found a strip of surgeon's plaster covering it. I removed this and found a wax-tipped kaiserlich mustache beneath it. Under a larger strip covering his chin there was a wilted, matted imperial. In five seconds I had removed the balance of the greasepaint—and the features of the man whom we had known as the Count were revealed.

For several seconds I stared down at the fellow as he lay there, still unconscious, on the floor; and I tried with little success to fit this key piece into the puzzle of the last week. Then I went over to Muriel.

Her pulse was strong and regular, her respiration just slightly abnormal. Obviously, she had only fainted. On her cheek there was an ugly bruise which I looked at with more self-loathing than I had believed anyone capable of feeling. I gently raised her lovely body in my arms, carried it to the couch in the corner and covered it with a Spanish mantilla which had been draped across it.

Then I went to the wash-basin in the corner, drew a glass of water, went back to the body of the Count and threw the water in his face.

After a moment the Count stirred, blinked open his eyes, and raised himself groggily to a sitting position. Finally he looked up at me, and after an interval of blankness, his eyes showed the birth of a slowly growing terror.

"What—what are you going to do?" he croaked at last.

"I'm not sure yet," I said grimly, "but whatever it is, you won't like it. In the meantime, if you have any regard for your present state of health, you will explain your motives in trying to persuade me that I had first killed a cat, then a man—and then my wife."

For a moment he stalled, tried to claim innocence in the whole matter—but that didn't last long. As soon as he had spat out the two teeth it cost him he made a clean breast of the whole thing.

It was simple enough. He had wanted Muriel since he had first set eyes on her, and he had evolved a bizarre, but really quite elemental and easily executed plan of getting her.

The act of being ousted by the landlord was just a gag. The Count had plenty of money. He had bribed the landlord to act his part, and had, with further bribes, elicited all the information that individual possessed concerning Muriel and me—which was enough for the Count's plans.

That first afternoon the Count had slipped a drug into my drink, as he walked behind me to go look at the painting on my easel. It was a tincture of adrenin, the product of the outer cortex of the suprarenal glands—those little hood-like affairs which are perched above each kidney in all vertebrates. This fluid is produced by the suprarenals at a great rate when there is any need for the body to go into quick action—such as danger, or any exterior stimulus to violent activity. It is the chemical which is produced by nearly, any of the strong emotions—fear, lust, anger. But when introduced into the system of a person in normal emotional equilibrium, it is itself, capable of producing almost any sort of emotion, without apparent psychic cause.

The dose administered, the Count told the fantastic story of his supernatural powers. He had hoped that we would prove to be hyper-imaginative, perhaps slightly superstitious folk who might swallow his tale of having bestowed upon me the weird gift which would remove all annoying people from my path, merely by my wishing for it. But he placed his chief hope on his adrenin and his terror buildup, in the hope of either driving me mad—or out of the country, he didn't care which.

He was at some pains to find three different alley cats enough alike so that I would think them the same one, three nights running. On the second and third nights he steeped their fur in hydro-sulphuric acid, which passed very well for the odor of decaying flesh. Of course, playing the part of the tramp in the park, taking a clout on the jaw from me, then hurrying downtown and disposing his body on the floor of our apartment before we got there, was comparatively easy.

After that, following us to the garage, discovering where we were headed by my remarks to Muriel as we stood near the door where the Count was eavesdropping, and following us out there by train, were likewise easy. The Count had already learned the location of the cottage from our landlord, and foreseeing the possibility that we might flee to it, had thoughtfully visited it several days before and dosed all open bottles of whiskey with adrenin.

For the rest, he had only to sit back and wait. Maddened by the drug and the liquor, I came near killing Muriel—and then passed out, myself. The Count was setting the stage for me when his lust for Muriel got the better of him—and thus I caught him fondling her, instead of coming on the tableau he had wanted me to find, and which, I have not the slightest doubt in the world, would have driven me incurably insane...

BY the time the Count had finished his weird

recital, Muriel had begun to show signs of life. Instantly

I went to her side—and as I leaned above her,

the Count made a dive for the doorway. I sprang after

him—then came to a halt. Caring for Muriel was far

more important than giving chase to that fantastic lunatic.

I went back to her side and gently nursed her back to

consciousness.

As we drove back to town, that evening, I told her what had happened. I explained the Count's motives, and the insane means he had employed to bring about the ends he sought. In fact, I told her everything I knew about the Count—save one thing.

A few miles after we left Patchogue we had come upon a police ambulance parked at the side of the road. Nearby was an automobile with a radiator which was smashed and covered with blood. Plainly an automobilist had hit a pedestrian. Then, as we passed the ambulance, I got a glimpse of the features of the raggedly dressed individual they were lifting into it on a stretcher. Fortunately Muriel, on the other side of the car, couldn't see the horror of his mangled body—nor could she see the man's face. But I saw it. It was the face of the Count.

I realized, then, that there was only one being in the whole world whose death I had ever really wished for—and that person was the man who was called the Count. The man who wanted me to believe he had granted me the devastating power of the Death Wish.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.