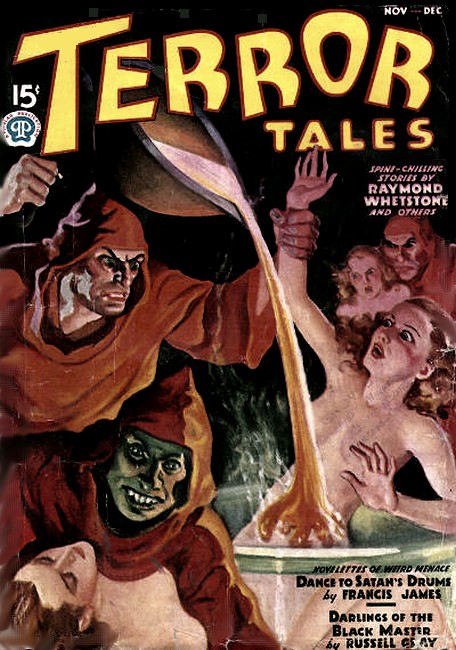

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Terror Tales, Nov-Dec 1937, with "The Child and the Corpse"

My child came running to me out of the depths of that dismal forest, bringing—for my inspection—a bloody human finger!

I TURNED the horses around when we reached the south end of the field and then let them rest for a few minutes before I started to cut the last swath of alfalfa. That finished, I would be up near the barns, and I resolved I would then call it a day. I was as tired as my horses. I had fired Hans Bridjhoff, my man-of-all-work the day before, and I was just beginning to realize how much of a load he had taken off my hands. But he had become unreliable, peculiar...

I sat in the cast-steel seat of the mower, the reins lax in my hands, and gazed off at the red sun just sinking below the tops of the trees to the west. And of a sudden my eyes fastened on a moving object emerging from the shadows at the base of the trees. The object was soon in the open, where the slanting rays of the sun could hit it, and I recognized the form of Bob, my five-year-old son. He was coming as fast as his short legs could carry him, and for some reason I began to feel a vague alarm.

My eyes flicked to the forest from which he had fled so precipitately, and I saw a strange thing. The somber shadows behind the boy—at the exact spot from which he had emerged—seemed to writhe and twist for a moment, before steadying down to motionlessness once more. It was exactly as though the shadows had been tangible, glutinous masses which his movement had disturbed.

With a muttered exclamation I began to descend from my perch atop the mower—and then I suddenly relaxed and resumed my seat. My eyes had played me a trick, and anyhow, Bob was perfectly safe. In a few seconds more he reached my side, stood there panting and grinning up at me, too blown to speak.

"Come on up, Bob," I said extending a hand toward him "I'll give you a ride back to the house."

But Bob shook his curly head. "No—wait," he panted. "Got som'p'n... wanna show you... A finger!"

"Finger? What's the matter with it—did you cut yourself again?"

"Not—not my finger," he wheezed. "It's somebody—else's finger..."

"What the—?"

I jumped down from my seat, knelt in front of him. One grimy paw was doubled in a tight little knot. I grasped it and uncoiled the pudgy fingers. In the small palm lay a grey, shriveled thing with clotted blood at one end. A human finger...

BOB had never met fear, so far in his life. The grisly

object was incapable of arousing any emotion in him

excepting curiosity. It was different with me.

"Where did you get it, Bob?" I asked, trying very hard to speak to him normally.

"Over there... Come on—I'll show you."

"No, I'll—"

But Bob had snatched his hand out of mine and was racing back toward the trees. I remembered those swirling black mists which had followed him out of the forest, and I was on the verge of recalling him. But I let him guide me to the edge of the woods.

"Come on," he said again, "I'll show you..."

He grabbed a couple of my fingers in his fist and tugged me after him into the gloom of the forest. He stopped after a few yards and pointed down at the leaf-strewn ground.

"There, Daddy," he said. "There's where I found it!" Then he looked up into my face speculatively, as though he wondered what I was going to do with the information, now that I had it.

I looked at the spot and felt my body grow tense. A few of the leaves were stained, and adjacent to them was a mound of leaves, heaped in a sort of ordered confusion which no wind could quite have achieved. Tentatively I thrust the toe of my boot into the pile—felt something solid...

I straightened and turned to my son. "Bob," I said, "go home."

"No, Daddy. I wanna—"

"Bob, go home—now!"

Bob gulped, hesitated a moment longer while his eyes searched mine for some sign of relenting; then he turned and started slowly back the way we had come.

I watched him until he reached the edge of the forest; then I turned my attention back to that mound. I took out my handkerchief, placed the severed finger in it and put the handkerchief on the ground. Then with both hands I clawed away the leaves.

If a human body were put through an ensilage grinder it would probably be in a condition similar to that of the cadaver I found beneath those leaves. It was a human hash, with hardly more than two cubic inches of bone or flesh in one piece. Yet there was one piece which told me to whom that body had belonged.

The skull had resisted the terrible chopping best—although even it had been severed cleanly through the major maxillaries, just below the temples. But the jaw—or rather the absence of the jaw—identified this ragout of a cadaver.

Old Juba Sneed, hermit, eccentric, reputed wizard and magician, had lived for as long as I had been in this country—ten or eleven years—in his little hut on the side of the hill back of the forest. His only companion was his daughter, a girl of sixteen or seventeen, who was supposed to be simple-minded. There had been talk at one time of remanding both of them to an asylum; but they lived so quietly and inconspicuously, never even coming into the village for supplies, since Juba trapped and shot all their food—and they apparently got along without bread or other staples—that the movement died from sheer lack of impetus. One never saw them from one year's end to the next, and we knew they were still there only because we occasionally caught sight of smoke coming from the chimney of their isolated cabin up there on the hillside.

I was one of the few people remaining in the country who had even seen Sneed. That had happened shortly after I bought the farm. The woods and the eastern slope of the hill went with it, and I was naturally curious concerning the identity of the person who was squatting on it. I went up there, one day, and Sneed came to the door, after I had pounded on it for fully three minutes.

I had never seen such a human ruin in my life. He was clothed in black rags from head to foot. It looked like the remains of what had been an old Inverness cape with a hood. And the face that peered out of that hood was only half a face: there was no lower jaw. The skin which had covered the lower maxillaries was puckered and shrunken, scarred and flabby like an old grey purse. He snarled something unintelligible at me and slammed the door in my face. I saw no sign of his daughter.

Later, down in the village, they told me that the old man had suffered an infection of the bone which had necessitated the removal of his entire lower jaw. That had occurred in his early manhood. Bitterly conscious that he had become a monstrosity, he had built himself this cabin on the mountainside and shut himself away from the world. But as they say, there is no man in the world so repulsive that some woman will not tolerate him, and Juba Sneed had finally married. A widow, who formerly lived on a small homestead adjoining my farm, suddenly appeared in the village one day, demanded a license and the services of the justice of the peace; and took the latter to Sneed's hermitage where the official joined her in marriage to the exile. A year or so later the daughter had been born, and a few years after that Mrs. Sneed had died.

The portion of the skull which I now held in my hand, blood-smeared though it was, could have belonged only to Juba Sneed. It was a puckered, cicatrice-seamed bag of skin beneath a set of broken and discolored teeth, supported by the remnants of the upper jaw and sinus processes.

I PUT the gruesome thing in my handkerchief with the

finger, and turned to leave the forest—only to come

to a sudden halt. A sound had come from the depths of the

woods behind me.

For some reason I suddenly felt a strong disinclination to turn back and investigate that noise. My face was turned toward home, the open spaces of my clean fields. There was peace and security there—and behind me the forest was gathering in clots of blackness, in moving coils of shapeless shadows, hiding I knew not what. I remembered the whorls of writhing masses which had seemed to follow Bob a short distance out of the woods. The skin puckered on the back of my neck, and I felt something looming out of the tall dark trees behind me, sweeping toward me...

With a curse of impatience at my superstitions I whirled about. The woods were silent, motionless, cloaked in the fast thickening shades of twilight. And again the sound reached my ears: a dull clang as of a heavy, muted bell.

I deposited the grisly remnants of Sneed on the ground, and made my way as silently as I could toward that sound. It was being repeated at regular intervals, now, and soon increased in tempo until it had achieved a sort of tom-tom dance measure. In spite of myself, fantastic visions of gnarled, twisted gnomes dancing to the beat of a demon's drum arose in my mind.

Gradually, as I moved forward, I became aware of darting flickers of light on the leaves and the boles of the trees, and soon I could see the wavering glow of a fire ahead of me. The dull throbbing of the bell grew louder.

I circled to the right where the cover was better and crept on—and presently I parted the last of the bushes between me and the little clearing whence the light and the sounds emanated, and looked up on a sight which might have been lifted bodily from the Dark Ages.

It was no bell which I had heard. Propped above a small fire was a huge iron kettle from which coils of yellowish steam were arising. Beating on the edge of the kettle with a blood-spattered cleaver was a hunched figure in a tattered ruin of a hooded coat. Kneeling at the side of this apparition was a young, vacant-faced but beautiful girl, gazing with rapt and fearful fixity at the kettle.

Premonitory prickles of eerie terror raced over my skin as I watched the hooded figure. Then its head raised, and the fearful auguring of my nerves was fulfilled: the fitful gleam of the fire lit the repulsive, chinless face of Juba Sneed!

THIS was insanity, I told myself. I could not be seeing

what I seemed to see. A hard day's work, and the effect of

the glaring sun in my eyes for long hours...

But then the apparition spoke, and I knew I could not be deceived, could not be dreaming. This was Juba Sneed.

"We shall see the power of Ahriman, daughter," he croaked. "We shall see his gratitude for a life-time of devotion."

Juba Sneed—and his daughter.

"Beelzebub and Astaris, hear my plea: the body and face of youth; the loins and sinews of a strong man. Hear me, Sheitan and all your saints!"

The drumming of the blood-splotched cleaver on the side of the kettle rose to a deafening clatter—then suddenly subsided as Sneed flung the cleaver to the ground and fumbled feverishly in the pocket of his ruinous coat, alternately muttering and shrieking prayers to his infernal gods. His hand emerged from his pocket, darted at the cauldron—and immediately the scene was blotted out in an immense eruption of yellow steam from the pot.

From that biliously luminous fog Sneed's voice, continuing its chanting, only strangely muffled and chocked-sounding, now, rose and fell. There was one small, bewildered scream from the girl, and after that no further sound from her.

Finally the steam began to drain away, and a looming shape became visible in the midst—a tall, broad-shouldered shape which had no resemblance to the twisted hulk which had been Sneed's body.

Its back was turned toward me, so I could not see the face, but the voice was still Sneed's voice:

"It is finished! No longer am I your father. I have been given the body and the soul of a young man—a man of great strength, wise in the ways of love... I am no longer your father. I am—your lover!"

The steam had cleared almost entirely away, now, and I could see the girl. Her poor, imbecile's face held a look of blank horror as she shrank back, hands extended in front of her, from the advancing figure of the man who had been Juba Sneed.

"No—" she wailed in her child's voice—"no..."

But with a savage lunge the man was upon her, grappling with her, tearing the dress from her writhing body with avid fingers, while an unintelligible muttering came from his lips.

His movements had brought him about so that his profile was toward me, now, and I gasped audibly with unbelieving amazement. This was indeed the face of a young, virile man, black-haired, deeply tanned—except for the lower portion of the face. His jowls and jaws were a livid, ghastly white—as though the skin had been newly grafted there!

But stricken to a paralysis of horrified amazement though I was, the next thing that happened jarred me from my trance like a bucket of cold water thrown in my face. The man had clutched the shoulder of the girl's dress, and with one terrific jerk ripped it from her body, so that she stood there nude, excepting for her garter-less stockings and shoes. At the same instant a childish voice raised in indignant challenge came to my ears from the other side of the clearing:

"You leave that lady alone!"

And the next instant Bob rushed out of the bushes and charged toward the towering figure of the man, his small fists raised and his face flushed with anger!

I was out of my covert and half-way across the clearing when Bob reached the man. The fellow raised a fist and let drive, even as I roared a profane warning at him. Bob was literally lifted from his feet by the blow and collapsed in a limp heap three yards away. That turned me into a murder-bent madman in an instant—and was therefore responsible for my undoing. I charged the fellow like the veriest amateur, wide-open, with my fingers clawed for a grip on his throat to strangle him.

I WAS met with a competent straight left, which was made

all the more effective by the reckless speed of my rush.

I felt my jaw crack, and my neck snap back like a flicked

whip. Blackness rushed up at me as I plunged to the ground

like a felled tree.

But my rage—and the consuming fear of what might happen to my boy—kept me going for a few moments longer. Unable to see anything but a crazy pattern of burning, dancing lights, I tried groggily to raise myself to my feet. I managed to get to my knees, and the lights began to take shape before my eyes. I could see the form of my assailant looming above me. Something gleamed above his head, then flashed down. I thought of the cleaver—and then everything was swallowed in blackness which would stay back no longer...

But he had hit me with the flat of the cleaver, as I realized when consciousness came painfully back to me. I was lying, bound hand and foot on the ground near the fire which was still burning beneath the black cauldron. I turned my aching head, and my bleared eyes took in a sight which turned me cold with horror. Lying a few feet from me, sprawled on the ground in the laxity of unconsciousness, was the naked body of Juba Sneed's daughter. But it was the tableau beyond that motionless figure which drove back the breath into my lungs and started the cold sweat beading out over my whole body.

Standing just beyond the girl's form was the figure of the man who had been Juba Sneed. In one muscular hand he held Bob's limp body by the scruff of the boy's jacket, extended almost at arm's length. He looked at the boy with head cocked to one side, his eyes gleaming with a blood-lust and his mouth curled in a dreadful smile of anticipation. In his other hand he gripped the cleaver...

The sounds which came from my throat were not human, but they served to attract his attention, to turn his terrible eyes from my son to myself.

With a chuckle the fellow shambled toward me, still holding Bob's small unconscious body aloft with his left hand.

"So you've come out of it, have you?" he growled as he stood above me. "I'm almost sorry. Now you may cheat me out of the fun of making mince-meat of the kid's body. You may do it, because I'm a good business man—and my rule is, business before pleasure, every time."

The voice was no longer Sneed's voice. It was a heavy, virile voice which belonged to the young body—a voice which sounded oddly familiar.

"You let that boy alone or I'll tear you apart if I have to follow you all over the earth to catch you," I muttered thickly.

The fellow's lips curled contemptuously. "You're scaring me to death," he sneered. "But I'll tell you what I'll do. You've got a nice little farm over there. Suppose you just make out a deed of sale to me—for value received, of course—then get out of this country and stay out. If you do that I'll send your kid along after you, pretty soon..."

"You damn fool, you could never get away with that. You're not known here; people would get suspicious immediately. Besides, I don't carry deed forms around with me in my pockets."

"A simple transfer of title will do, in this state," said the man. "And it would be worth while becoming Sneed again to get that land of yours."

My eyes narrowed. My vision had cleared, now, and I could see the fellow's face plainly by the soft glow of the firelight. The lower part of his face was not the dead white of newly-grafted skin, as I had thought at first. It showed the faint blue stubble of a beard—a beard which had been recently shaved. Suddenly I knew where I had heard that voice before—where I had seen that familiar and yet strangely unfamiliar face.

"By God!" I whispered. "Hans Bridjhoff—my hired hand. You've shaved off your beard since I fired you the other day..."

BRIDJHOFF stared down at me, and that somber, feral

gleam which could originate only in a madman's brain

glittered in his eyes.

"All right," he said. "That fixes you. You've recognized me, so I've got to kill you and your kid. I've got to stick around here a little longer until I wrangle the hiding-place of her old man's jack out of the gal, yonder."

He turned and directed a lecherous grin toward the prone figure of Sneed's daughter.

"I'm figuring to have a little more fun with her, too. She can't take my kind of love-making, yet—but she'll get used to it in time..."

He turned his maniac's face back to me.

"I've heard about this Sneed for a long time, and I got a job with you just to be nearby where I could case the layout. I was about ready to quit when you fired me—and the next day I caught old Sneed in the woods. He wouldn't come across with the information about his gold, and I sort of accidentally cut him up a little too much while I was arguing with him. Then I got the idea of impersonating him to his daughter, and maybe getting the dope out of her. I knew she was light in the head, and probably wouldn't be too hard to fool. Also, if she didn't find anything was wrong with her old man she wouldn't be raising a row about it down in the village. It was easy enough to make up like the old fool, with a little flour and lampblack.

"Then I got another idea. The old boy was supposed to be a wizard. Why not pull off a stunt for the gal which would make her think her old man had regained his youth—become somebody else? Somebody who could be her lover? Then she'd never get suspicious if anything slipped.

"Then you and the kid had to come along and gum up the works, somewhat. I figured at first I might do myself some good if I could force you to turn your farm over to me, and then chase you out of the state. But I see, now, that'd be a little too risky. I'll just have my fun with you instead; get the dope out of the gal about the treasure, and then scram."

In a leisurely manner the fiend raised Bob's body a trifle higher, drew back the arm whose hand gripped the cleaver. "Watch me lop off a foot with one stroke," he said conversationally. "I've gotten good with this thing."

"Wait!" I croaked, terror choking my voice down almost to inaudibility. "I'll give you anything—everything I've got. I'll leave the state. I swear I won't tell."

"Nope—too risky. Here goes!"

The cleaver swung high, swooped down straight at the little ankle with its dusty, bunched-up sock. I screamed a curse that seared my throat, and closed my eyes in an agony of horror that almost robbed me of consciousness. But the next instant my eyes flew open.

Bob, apparently, had been feigning unconsciousness—at least for a time. As the cleaver swept down at his foot, he suddenly swung up on Bridjhoff's arm as though it had been a horizontal bar, and kicked the fellow full in the face.

Bridjhoff dropped both boy and cleaver with a howl of anguish, his hands flying to his smashed and bloody nose.

Agile and swift as a squirrel, Bob snatched up the cleaver and leaped over to me. Using the blade of the big knife like a saw, he had broken through the strands that held my wrists.

The murderer flung himself upon my supine body, his fingers fastening upon my throat like talons, his mad, blood-spattered face contorted into an insane mask.

But he could not see my feet and I could feel my ankles coming free under Bob's cleaver.

Then, suddenly I was as free as my adversary. I raised my legs beneath Bridjhoff's body and let drive.

It was all over, presently, and Bridjhoff was lying on the ground, unconscious, his arms securely tied behind his back, ready to be marched into the village and turned over to the sheriff. The girl was beginning to stir. I went over and placed her clothes beside her.

Bob, a black-and-blue lump swelling the side of his jaw where Bridjhoff had hit him, looked up at me and grinned. He stuck out a grimy paw. We shook hands.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.