RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

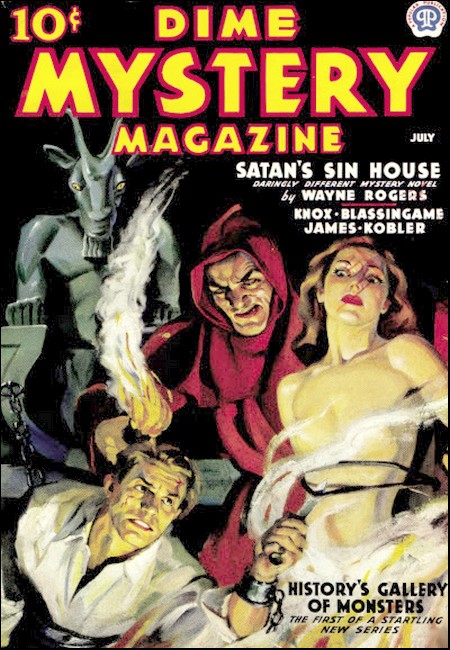

Dime Mystery Magazine, July 1937, with "The Hunger Without a Name"

Is it only that sometimes our imagination can trick us horribly—or is it indeed true that the sanest of us change, at times, into monsters of grisly lust?

MY COMPANION chuckled deep in his throat. It was the first sound he had made since I had picked him up, five miles back on the road. I looked at him, a little startled. "Ye mayn't believe it," he said, and gave that somehow obscene cackle again, "but human meat's the best meat there is—fer eatin'."

My throat constricted. I slammed my foot on the brake, full force. Rubber screamed and the car ground to a stop.

"Here's where you get out," I said. "Beat it!"

If I had been normal I might have acted differently—but I wasn't normal; I was sick, physically as well as mentally. Fever raged in my blood, and my mind had been in a pulsating, throbbing turmoil for two days. I was on my way home, having abandoned my trip to the middle-west and had picked up this old scarecrow because he had looked so forlorn, standing there at the side of the road with his thumb hooked back over his shoulder in that abjectly appealing gesture of the hitch-hiker.

The old man glared at me. I hadn't noticed before what a sinister looking being he really was. His eyes, gleaming ferally far back in their bony dark caverns, seemed to curse me soundlessly, even as his cracked voice was uttering meek apologies.

"Why, now—no offense meant, friend," he whined. "I was jest funnin' ye a leetle. It happened a long time ago—an' I served time fer it, I did. It was the shipwreck o' the Lady Bountiful, ye know."

Yes, I knew. I remembered the news-stories of the wreck of the Lady Bountiful, and how some of the survivors on one of her rafts were alleged to have eaten two of their number before the rest of them had been rescued. I remembered—but that didn't make me relish my companion's company any the more. As yet he hadn't made a move to get out.

"Did you hear what I said? Beat it—get going!"

The old man snarled wordlessly.

"Why, ye young!"

I wasn't justified in doing it, even though he had called me a foul name. He was old and infirm—but, as I have said, I was feverish and my nerves were wrought-up, overtaxed by two nights' sleeplessness. With one hand I gripped him by the shoulder. With the other hand I flung open the door of the car. Then I thrust him savagely out onto the road. I slammed the door and slipped in the clutch, meshed the gears and jerked the car into motion.

It wasn't until I came to the next turn that I even looked back. Then, fearful that I might have harmed the old fellow with my roughness—and because of another and much more disturbing feeling—I glanced back over my shoulder toward the spot where I had left him lying in a huddled heap by the roadside.

But I saw no one. The old man had disappeared as completely as though the earth had swallowed him...

THE thought of my late companion preyed on my mind all

the rest of the way home. It wasn't alone what he had

said—although in view of the nature of the things

which had been revolving in my febrile consciousness

for the past forty-eight hours, that was sufficiently

disturbing. But there was something about his person that

was incongruous, vaguely and mysteriously revolting. His

arm and shoulder, when I had grasped him to throw him out

of the car, had not felt like those of an old man. There

had been rounded sinew under that ragged coat—there

had been biceps like those of a youth in the fullness of

his vigor...

The house seemed quiet and deserted as I rolled into the yard. The garage door stood open, and I saw that Jessie's roadster was gone. The knowledge that my wife would not be home to greet me depressed and unreasonably irritated me—another evidence of my feverish state of mind. I entered the house and was met in the hall by Lula, the cook and maid-of-all work. Lula's smile of greeting faded to an expression of anxious solicitude as she gazed into my face.

"Oh, you look ill, Mr. Halprin," she murmured. "Can I do anything? Mrs. Halprin is visiting at Mrs. Bigelow's. She said she'd be home early, but she's having dinner with them. Shall I get you something to eat—or anything?"

The girl was an attractive youngster, sixteen or seventeen years old, but I had never been as tolerant of her general inefficiency and childish stupidity as my wife. God forgive me, I had often scolded her soundly for her mistakes, although the poor girl was probably doing the best she knew how, most of the time. I'm glad, on this last occasion that I ever saw her, that I spoke to her with kindness.

"You may bring a pot of tea to me up in the study, if you will, Lula," I said. "I don't want any food tonight."

"Yes, Mr. Halprin—and—and, Mr. Halprin?"

"Well?"

"Mrs. Halprin said I might have the evening off to go into town to a movie—so after I make your tea, if you don't mind...?"

"All right, Lula."

"Thank you, Mr. Halprin."

I went up to my study and threw myself down on the divan. My head throbbed, my temple veins pounded, my mouth and throat were dry, hot. I gulped dryly and hoped that Lula would not take too long about making the tea. I closed my eyes—and the ancient hitch-hiker was instantly in the room with me.

The illusion of his presence, standing there at my side was so perfect that I almost cried aloud; and I opened my eyes with the suddenness and desperation of a man jumping back from the crumbling edge of a precipice. The old man instantly vanished.

But that momentary vision crystallized something which had been plaguing the fringes of my consciousness ever since I had first laid eyes on him. I don't know how to convey it in comprehensible terms, but—I seemed to realize a strange, frightening sort of identity with this old man of the road.

You see, once before I had experienced an attack of fever such as I had now. During the semi-delirium which accompanied it I had dreamed of participating in some such horrible adventure as he had tried to describe to me. In that dream, I, too, had been among the ill-fated crew of the steamship Lady Bountiful. I, too, had been with that group on the raft—that handful of survivors whose lives had been sustained until they reached port by the bodies of their companions. And I had been, not myself, but a hard-bitten, glittering-eyed ancient mariner such as the one I had picked up that very afternoon on the road!

But the worst of it all came back to me now, after that terrifyingly realistic vision: I remembered the taste of the flesh I had eaten; I remembered its succulent fascinating flavor. And I knew, in that moment, that I craved with every nerve in my being to eat of such flesh again!...

SLEEP sometimes comes to sick people with the suddenness

of shock-induced unconsciousness. Maybe it wasn't

sleep—maybe it wasn't true unconsciousness that came

to me, then. My only memory of it, at any rate, is that of

a black, blank void in time, ending with my opening my eyes

to the realization that it had grown suddenly late, that

night had fallen and the room was in darkness.

But seemingly my fever had passed. I felt cool, refreshed, and curiously without that weakness which the abatement of fever usually leaves one with. I lay there in the darkness for awhile, marshalling my thoughts, at first with a little difficulty, then with perfect clarity and chronology. I remembered Lula had said she would make some tea for me and bring it up...

For some reason the thought of Lula caused me to feel uneasy—induced, without any apparent connection, the memory of the old man of the road...

I got to my feet with a feeling of unaccountable panic growing in my heart. I went to the top of the stairs.

"Lula," I called, "Lula—come here..."

There was no answer.

Without turning on the lights I felt my way downstairs, stumbled blindly through the dining room, pushed open the swinging door into the kitchen. I turned on the lights there. It was empty.

No Lula. Nor was she in the pantry.

Then I remembered what she had said about the movie. Jessie had said she could go. She would fix my tea first... Only she hadn't fixed my tea...

Then I saw something on the kitchen floor. Something splashed darkly over the surface of the clean linoleum. Lula had spilled something...

Yes, Lula had spilled something. She had carried something, spilling it as she walked, to the icebox. There was a trail from the kitchen table to the refrigerator in the corner. I advanced into the room and looked down at the stains. I felt myself growing cold as stone as I did so.

Then, falteringly, I walked slowly over to the refrigerator, following that trail. "She always was careless," I muttered. "She didn't—wipe it up..."

I reached out and touched the handle of the refrigerator door. It was no colder than my hand. I turned it and the door swung open. There was a large plate on the top shelf containing a piece of meat. The meat had been very roughly cut and it was very fresh. It was still dripping blood—dripping blood down to the plate on the shelf below it. On that plate was a small human hand which had been roughly hacked off at the wrist...

EXCESS of horror has the faculty of projecting the human

brain into a sort of trance-like state in which nothing

seems real. As I stood there, staring at the dreadful

contents of that refrigerator I felt that I was dreaming,

that what I saw could not be true. And mixed in with this

nightmare state a dreadful question was hammering at the

gates of my memory: Was it really horrified amazement

which had been in my heart when I opened that refrigerator

door—or had it been merely a sickening confirmation

of secret knowledge which my subconscious mind had harbored

all along? Was I sure that it was not I who had placed

that dreadful flesh there in the first place?

I was so weak that I could hardly stand. I closed the door and leaned sickly against the refrigerator while the soul-destroying questions beat at my reeling brain. What had my body been doing while my mind had been blank this evening?

Then abruptly my senses were shocked back to actualities by the perception of a sound. It was a faint sound, coming seemingly from beneath my feet. It was repeated, grew louder, changed direction. I located it as coming from the bottom of the cellar steps, then progressing slowly upward. A shuffling sound accompanied by the creaking of wood: footsteps coming up the cellar stairs—slow, laboring footsteps as of one who carried a heavy burden...

Panic gripped me, shook my helpless, paralyzed body. I must arm myself...

But I couldn't move an inch. Had I not clung to the refrigerator, I would have fallen to the floor. After the brief respite my fever had swept back over me, draining my body, already enervated with plethora of horror, of every ounce of strength. I could only stand there, swaying sickly, listening to those slow footsteps dragging onward, getting closer...

Down the hall they came, thudding softly over the rugs, scraping on the intervals of bare flooring. On they came—and halted just outside the kitchen door. The door swung open an inch, and paused...

There was a moment of silence.

I made a last effort to marshal my strength, to steel myself to encounter what was behind that door...

The door moved gently, opened a little more. Something bumped against it dully, and a dark mass showed through the crack. A streamer of something—long, dark... The door opened wider and a woman's head, face turned toward the ceiling, long brown hair streaming downward, appeared in the aperture... Jessie's head!

I could not move, I could not even scream. I stood there with splinters of icy horror pricking the skin of my entire body. And then I heard a chuckle, low, gloating, filled with the sort of mirth only the damned in bottomless hell can ever know...

Abruptly then the door swung wide open, and into the room lurched the bearded, feral-eyed old man whom I had picked up on the road. In his arms he held the naked, limp form of my wife. In the hand of the arm which passed under her thighs he clutched a huge, bloodstained butcher knife.

FOR a moment I was certain that I was living in the

midst of a nightmare—or had gone mad. I had left this

old man many hours ago, far out on the road. True, he could

have caught another ride—but how could he have known

where I lived, supposing he were deliberately searching

for me? And Jessie—she had been away visiting

friends...

But these thoughts went reeling through my brain only as froth on the black tide of horror which swamped my consciousness as the old man allowed Jessie's white body to slip to the floor, and then stood over her, his black-clotted knife in his hand, his beast's eyes glittering at me with evil glee.

"So ye don't crave the long pig, yerself," he cackled. "An' ye'd throw an old man out onto the road jest because he did! Well, me young bucko, once ye've et it ye wont be able to git along without it—an' ye're goin' to have yer first meal in a jiffy—"

But a degree of sanity and will power, if not strength, had returned to me. I uttered a wordless snarl and lurched toward him.

Instantly the old man sank to one knee, his right arm swept down, and the knife in his hand pricked the snowy skin of Jessie's breast.

The old man said nothing. He knelt there with his dreadful knife poised above Jessie's heart, and his animal's eyes glittering up at me in mad, gleeful triumph.

"No!" I gasped and fell back a step. "No—don't do that—"

The old man chuckled gloatingly. "All right, me bucko, then behave yerself. We got our meat, only I ain't dast try to cook it, so fur. But I reckon everything's set now. Go git that hunk outta the ice-box and fry 'er up fer us—er—I'll begin carvin' a steak outta yer missus, here!"

"Yes—yes—anything!" I muttered feverishly. "Only don't harm her—"

I retched, staggered with sick dizziness, but I got that dreadful plate and its contents from the top shelf of the refrigerator. I took a heavy iron skillet from the bottom of the butler's cabinet and put it on the stove. I lit the gas and put the pan and its bloody contents over the blaze.

All the time I had been watching the madman from the corner of my eye—noting that his position never changed, his vigilance never relaxed. His eyes followed every move I made like beady, baleful searchlights. The knife hovered over the rounded, rose-tipped breast of the girl I loved better than life...

But suddenly there was a startled cry, then a piercing shriek. I whirled, and saw that Jessie had regained consciousness—awakened to a living nightmare which, now, could result only in her dreadful death at the hands of a blood-maddened lunatic.

The old man had started back at the sound of her cries. He shrank backward in a momentary alarmed reflex—and that was all I wanted. With one sweep of my arm I hurled the heavy iron skillet and its horrible contents from the top of the stove full into the old man's face. And in the next instant my own body had followed it.

I had noted that afternoon that this man was not as old as he seemed, if a powerful, muscular build means anything. But of course he was a seaman, hardened and strengthened by the strenuous life aboard ship. I had my work cut out for me in subduing him.

We rolled all over the floor. Time after time I smashed my fist into his bearded face, and time after time I received his killing blows in return. Once or twice I could feel my senses leaving me—and only the knowledge that if they did, Jessie would be irrevocably doomed, brought them back. But at last my weakened condition began taking its irresistible toll, and my body lay helplessly beneath his as his blazing, maniac's eyes glared down in triumph at mine and his bony, lethally strong fingers dug into my throat. I closed my eyes in agonized desperation, striving to gather my waning forces for one final despairing effort—and suddenly he slumped over on top of me.

Over us stood the gleamingly nude, trembling body of Jessie, a freshly reddened knife in her hand...

THE old man didn't die of his wound. He lived to be

remanded to the state hospital for the criminally insane,

in which he had been confined ever since his rescue with

the survivors of the Lady Bountiful—until he had escaped two days before I encountered him. He told the sheriff,

who came to get him at my summons, that he had hopped onto

the tire rack of my car after I had thrown him out. He had

thus ridden home with me, sneaked into the house, hidden in

the basement. There he had heard poor Lula call Jessie at

Mrs. Bigelow's and tell her I was home. He waited until she

arrived, came upstairs to find me asleep, heard her tell

Lula that she was not going to disturb me but was going to

bed in her own room. Then, after an interval, he had stolen

upstairs, attacked and killed Lula, stifling her screams,

taken her body down in the basement and dismembered it. He

had brought up the portions he fancied most and put them in

the refrigerator, but fearing discovery while preparing it,

had gone up to my wife's room, stifled her with a pillow.

Jessie had fainted, and he had dragged her body down into

the basement, intending to bind and gag her.

But in the meantime I had come downstairs, and hatching the mad plan of forcing me to cook his grisly meal, he had dragged her upstairs, again.

So the whole ghastly episode was accounted for—save for one thing. It was some time before I could bring myself to tell old Doc Hough of my weird and terrible dream of being aboard that raft with the survivors of the Lady Bountiful—but when I did he had a ready explanation.

"Why, my boy," he said in his paternal manner, "the papers were full of it at the time. Your fever merely dug it up out of your subconscious—that's all. This fellow's picture was there with the rest of the survivors. There was nothing remarkable about your hallucinations."

Plausible—easily said. But residual horror lingers in my heart. The dream, the hallucinations, as Doc calls them, were strangely real and circumstantial. Who knows enough about the human soul to say it cannot travel outside the confines of its habitation? Who dares assert everything about the human mind can be explained in terms of physical laws?

And there is yet another dreadful piece of flotsam which the tide of horror has left behind—but that I cannot bring myself to define—even to myself. It haunts me every waking hour; it makes a ghastly horror of my nights... It is a hunger—a hunger without a name...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.