RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

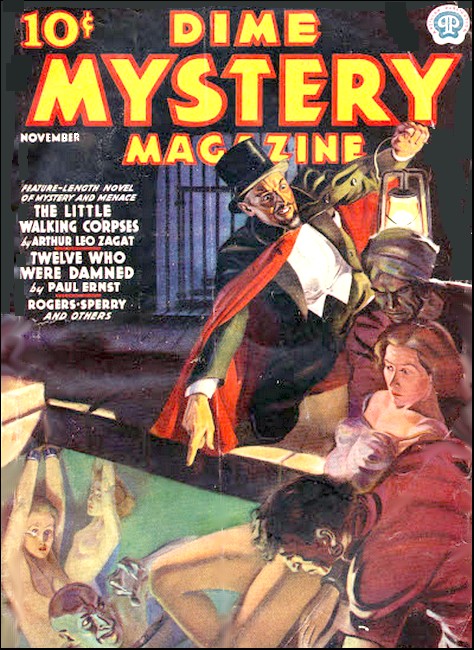

Dime Mystery Magazine, November 1937, with "The Woman From Hell"

Impelled by a force outside my will, I fought for and won a verdict of not guilty for the exotic Natacha Czernick, even though I knew that eventually I would submit to her fatal allure—and learn the true strength of the hideous powers of which she was accused...

THE jury leaned forward as I finished summing up for the defense. Their faces were intent, absorbed; but behind their concentration I sensed conflicting emotions, questions which they could not answer—questions which, I knew, they wanted me to answer for them.

But those riddles were in my own mind—and I had no answers for them. I had only an empty eloquence, a resounding peroration which contained the shadows of logic and reason—but not the substance of a solution.

"And so I must ask you gentlemen to remember that we are living in the twentieth century," I said. "You are no medieval Council of Ten weighing dark matters of superstition and black wizardry. The state has allowed witnesses to appear before you who hinted at things hardly heard in the courts of this country since the days of ancient Salem. Mention has been made of vampires, of warlocks and the 'evil eye'. Oh, there has been no direct imputation of these matters in relation to the prisoner—the state is far too subtle to introduce matter which could be so readily objected to. But the character and condition of the witnesses—their carefully extracted tales of Middle-European beliefs—all these, ladies and gentlemen, are designed to leave a residual impression which, I charge, the state has bent all its efforts toward creating..."

I cleared my throat and absently shuffled the papers on the table before me. I had been suddenly overcome by such a wave of feeling that my voice for the moment completely failed me. I had had the sudden premonition that my client was to be freed—and with that knowledge was born the conviction that her freedom was the last thing in the world I desired. Nevertheless, after a moment, as though impelled by a force outside my will, I continued.

"So we shall consider only the evidence—the tangible, legitimate evidence—which has been admitted in this case. We shall remember that the vampire legend has died with a stake in its heart, never to rise on this earth again. We shall hold firmly in mind the modern truth that the only ''evil eye' is the eye which looks upon innocence, and through the grey film of ignorance which covers it, sees only guilt. And on the basis of the admitted evidence we shall arrive at the only verdict possible in this case: Not guilty!"

It was while the judge was making his charge to the jury that my eyes stole to the beautiful, exotic face of my client, the prisoner at the bar, Natacha Czernick. The girl smiled alluringly as she sat there with her knees crossed, showing the rounded, silk-clad contours of her exquisitely molded legs. She smiled—and I shuddered in spite of myself. Her lips were as red as crushed pomegranates, and between them were flashing, tiny teeth—teeth that were pointed almost as though they had been filed...

I SAT in my library after dinner and tried to get the

case out of my mind. The woman is free, as she deserves to

be, I kept telling myself. There is absolutely no evidence

connecting her with Count Czernick's death—no

evidence which could be seriously considered for a moment.

The fact that his throat was slashed as though by a wild

animal, and that the state has been unable to present

a suspect who could or would have killed him in such a

manner, is no concern of mine. Natacha Czernick was asleep

in the bedroom of a friend's home at the time of the

killing, and the evidence of creditable witnesses has been

accepted verifying this. Now forget it!

Yet certain phrases kept running uncontrollably through my mind: "A vampire flits where she pleaseth and no human eye can watch her progress..." "The teeth of a vampire are as sharp as a lynx's, pointed for the rending of tough, living flesh..." "The lips of a vampire are red as the blood they feast upon; yea, as the poppy whose slumberous breath lulls its prey to the death of utter forgetfulness..."

Ridiculous that the words of an old rabble-rousing witch-finder like Makepeace Mather should be running through the head of a young, modern-day attorney. A young attorney, moreover, who was already over-due at the home of his fiancée, where his engagement to her was to be formally announced that very evening.

With an exclamation of impatience on my lips I jumped from my chair and started for the door of the library. I had taken but a single step, however, when I froze in my tracks, stunned motionless by the sound of a voice in the hall—a voice which I had heard only too often during the past two weeks.

"You are dismissed for the evening, Gregg," Natacha Czernick was saying to my butler. "Mr. Corrigan asked me to tell you. You may leave the house immediately."

The next instant she had opened the door to the library and closed it behind her—and again I caught my breath, even as I was about to demand an explanation for her unwarranted directions to Gregg. For Natacha Czernick at that moment was the most perfect vision of feminine allure any man ever beheld.

Her jet black hair was coifed high on her head and held in place with a diadem of diamonds. Wrapped closely about her exquisite form was a cloak of ermine, beneath which a gown of flame-colored chiffon flowed gracefully to the floor. The cloak, thrown open at her throat, displayed a décolletage breath-taking in its extremity. The girl's face was a white, perfect oval, framed by its black hair; and her smile, her luminous, slumberous eyes held an invitation no man on this earth could mistake.

"Donald," she murmured in her low, throaty voice, "Donald, I've come—to thank you..." She walked toward me with the undulant grace of a slowly swaying cobra.

With an effort I gained a measure of control over my faculties. "Yes, yes," I muttered. "You thanked me this after noon, Natacha. The obligation is fully discharged—think no more about it. I—I'm sorry, but I have an engagement this evening. I must beg you to excuse me."

"But just give me a moment, Donald!" She had reached my side and taken one of my hands in her cool, slender ones. "You must let me tell you how grateful I am. I couldn't—in that stuffy courtroom..."

As though hypnotized I allowed her to draw me around to the divan in front of the fireplace. She seated herself with an indescribably graceful movement and pulled on my hand until I sank down beside her. She nestled close to me and laid her cheek against my shoulder.

"Oh, it is too wonderful to be with you, Donald," she murmured. "You give me such a feeling of safety. You were so eloquent in the courtroom, so masterful. Like a knight jousting for the honor of his lady..."

Impossible to convey the weird misgivings these flattering, low-voiced phrases aroused in me. Yet I felt as though I were listening to the sardonic sophistries of a fury from hell's deepest pit. Natacha's tone held all sincerity, was warm with gratitude and affection—yet it sounded in my ears like the mockeries of demons. I sat there stupidly silent, and suddenly I felt a spot of cold on the back of my neck as though the door to some unimaginably frigid place had abruptly swung open...

"Donald, look at me!"

Natacha reached up, caught my chin in her palm and turned my head until I was looking down at her, into her lovely, dark-eyed face, and below at the ivory sheen of her palpitant breasts.

With a quick movement Natacha withdrew her hand, shrugged the ermine wrap from her smooth, naked shoulders. As she did so the right shoulder-strap of her gown slid down her upper arm, was followed by the bodice—and a perfect, rose-tipped breast was revealed.

As I gasped and made an awkward movement as though to replace the shoulder-strap, Natacha smiled languorously, revealing for an instant her white, pointed little teeth. Then with wanton abandonment she deliberately slid the other strap from its place and shrugged the gown down about her hips...

Whatever unnamable fears I had had before with regard to this woman, I forgot them all, now. Engulfed in a state of passion which tossed me like a rudderless ship on a storm-swept ocean, there was no room in me for anything but all-submerging lust. I grasped Natacha's white body in an embrace of wild passion such as I had never before known, and swept off the remnant of her single garment with-a fierce gesture which ripped its fragile fabric to the hem. With a sigh of rapturous triumph she leaned back on the divan...

I COULD not remember the nightmares that visited me

after I finally fell into the drugged stupor which passed

for my sleep that night. But when I awoke it was to fall

immediately prey to the most bitter, corrosive remorse. I

stood and looked down at the still sleeping, nude body of

Natacha Czernick on my divan, and it was all I could do to

refrain from picking her up bodily and throwing her out of

the house, naked as she was.

But healthy anger lasted only a moment, and was succeeded by the emotions I had always felt in the presence of this woman—only intensified, now, a thousand-fold. A small voice at the back of my brain was whispering sinister, soul-chilling things—was telling me that I had taken a step which could not be retracted. I had made an alliance, last night, with the unknown and unnamable things which had brought instinctive dread to my heart at mere sight of Natacha Czernick.

Yet I took a grip of my emotions and forced myself to decisive action. I leaned over, and although the contact chilled me as though she had been a corpse, I gripped Natacha's smooth shoulder and shook her—none too gently.

Her dark eyes opened, fixed on mine with an instant expression of lustful triumph—which as speedily was supplanted with a flash of anger as she saw the grim determination which must have been plain on my face.

"Get up," I said. "Get on your clothes—and get out!"

My rudeness was the gauge of the uncanny terror which was gripping my soul in a frigid vise. I felt that if I did not get rid of this woman immediately I would go mad.

She looked at me for long moments, the somber gleam of anger in her depth-less eyes glowing and flaring until they seemed two pits of venomous flame.

"You dare—" she whispered at last in a hiss of hate unimaginable—"you dare to say this to me!"

Her anger did something for me which any other reaction of hers would not have done—it stiffened my spirit, bolstered my determination.

"Yes," I said, "I dared say it. I repeat it: Get out!"

Natacha swung her feet to the floor, she stood erect, her perfect body rosy and alluring even in the harsh light of morning. Again she fixed my eyes with a long stare in which depthless hatred and rage writhed like blistered snakes. Then, suddenly, she threw back her dark head with its gleaming, disheveled curls and laughed—laughed with a note of unknown menace in her voice that sent a shudder through my frame from head to foot.

"Very well," she said at last. "I will go... but before I go I will tell you this—" all laughter had died out in her, now, and there was nothing left but loathing and bitter wrath—"you spoke—oh, so eloquently—in court yesterday about things of which you are abysmally ignorant. You admonished those twelve idiots in the jury not to let superstition sway their judgment, didn't you? You spoke so pride fully about modern science, twentieth-century intelligence...I could hardly keep from laughing aloud in court...

"Let me tell you, my friend, things exist which no fool of a judge or lawyer or jury would dare dream of—or admit could be, if they did dream of them. You spoke learnedly of the evil eye—a thing which has been acknowledged and dreaded and fought against in Central Europe for two thousand years. You do not believe in the evil eye, do you? Not today. But tomorrow you will believe in the evil eye, Donald Corrigan... Yes, tomorrow you will believe..."

Natacha laughed again, a full throaty cachinnation which sent icy shivers of dread down my spine. Then she snatched up her wrap and flung it about her body. She thrust her bare feet into her pumps and, disdaining the rest of her clothes, swept out of the room, slamming the door behind her. Through the window I saw her hail a surprised cabby, step into the taxi, and disappear down the tree-shaded street...

I DREW a sigh that was like an audible shudder, and

began to take thought of the situation in which I had

placed myself. How could I expiate the unforgiveable insult

I had offered Frances? What explanation had she offered her

mother's guests for my unaccountable absence last night?

How could I ever condone the fact of my failure to appear

on what was to have been one of the most important evenings

of our lives—the evening when our engagement was to

be announced?

Despairing of being able to contrive a decent lie I went over and sat down by the telephone, dialed her number.

No need to dwell on the painful conversation that followed—painful both to Frances Dunbar and to me. For I had never lied to her; couldn't do so with any degree of persuasiveness, now. Yet she forgave the unforgivable, accepted my paltry, incredible story of having been called suddenly upstate to the capital—so suddenly I had not had time even to send her word... She begged me to come to her immediately.

Fervent with contrition and remorse, I promised I would be there within an hour. I hung up, rang for Gregg, and went upstairs to bathe, knowing he would follow.

But when I had bathed and dressed Gregg still had not put in an appearance. I phoned the garage myself, and after a considerable wait succeeded in getting a response from Peterson, my chauffeur. Telling him to bring the cabriolet around immediately, I hung up and went downstairs.

Peterson was even slower about showing up with the car than he had been in answering his phone. I was fuming with impatience by the time he arrived, and snapped a few pointed remarks at him as he stood by the car door, waiting for me to get in. Peterson took my dressing-down without a word, looking straight in front of him with a strange, unfathomable expression on his normally composed, good-natured face. Suddenly I remembered an incident of a fortnight before, and I gripped his shoulder, swung him half about to face me.

"Peterson," I said, "are you drunk again? If you are, go back to your rooms and I'll take a taxi. I don't want to risk another accident—"

Peterson threw up an arm as though he actually expected me to strike him. There was an expression of stark, incredible terror on his face as his widened eyes stared for a moment into mine—then glanced quickly away as though the thing he feared was in my face.

"Please, sir," he said, and there was an unmistakable quaver in his voice, "don't—don't look at me... I mean—beg pardon, sir, I'm not drunk... I—I'm—quite all right, sir..."

I could see actual sweat beading on his forehead as he stood there, staring straight ahead as though his life depended on his not moving his eyes a fraction of an inch. I stood silent for a moment, dark thoughts, incoherent but freighted with cold terror, writhing in my brain. Finally I mumbled his directions to him and stumbled into the car. Peterson saluted jerkily, got under the wheel and we moved off down the street. I sat there, like him, staring straight ahead of me, trying to get the dread and terror in my soul out in the open forefront of my mind where I could look at it. But something, some weakness I hadn't known I possessed, prevented me from doing it. I could only sit there, my mind a vacuum save for an all-pervasive fear which would not be analyzed.

So submerged in my stupor had I become that I was paying no attention to our route; was not even conscious that we had entered the business part of the city—which it was necessary to cross in order to get to the Dunbar residence—until the van suddenly loomed ahead of us at the corner of Twelfth and Loomis. It had darted out of Loomis Street just as the lights switched, and cut in ahead of us all in a single instant. Peterson swerved the wheel violently to the right and slammed on the brakes with every ounce of strength he had. But it was too late... With a rending crash the cars collided, throwing me with stunning violence against the dash.

Lights blinked behind my eyes. I was aware of a ghastly quietness immediately following the uproar of the collision. The lights were slowly swallowed in a slow up-surge of blackness, but a low sound in that strange, ominous stillness caused me to wrench my eyes upward. The sound was a grisly gurgle—a sort of liquid moan. It came from Peterson who, hanging limp and blood-drenched over the steering wheel, seemed to be glaring at me with horrified accusation in his dulling eyes. His neck was half severed by a large slab of the windshield which had been dashed out by the force of our collision and thrown backward to imbed itself in his throat, from which it fell of its own weight, bloody and clattering, to the floor of the car.

My own eyes, sick with horror, slowly sank to the slab—then raised a few inches to Peterson's hand hanging above it. His hand, too, had been cut by another piece by flying glass. It was relaxing, now, the fingers half straightening in the limpness of death. But before the fingers had relaxed I had noticed a strange thing about their position: the forefinger and the little finger extending straight down; the middle two being held curled into the palm of the hand by the thumb.

With the gibbering of mad demons in my ears I lost consciousness...

WHEN I awoke I was in a cot in a hospital. For a long

time I lay staring at the white ceiling of my room, trying

to get my thoughts into line, trying to dislodge the

dreadful fear which had entered my heart to lodge there, as

it seemed, until death. For it had come out into the open,

now, and I recognized it for what it was...

It seemed to me that I had lain there for hours, too apathetic even to ring for the strangely absent nurses when, very slowly, the door opened and a white, starched figure appeared. I could see a small, frightened face framed in dark hair held in place by a nurse's coif. I heard a voice that was hesitant, oddly timid.

"There's—there's a lady to see you," the little nurse was murmuring.

"A lady...? Who is it?" Then suddenly I straightened, sat upright in my bed. Perhaps it was Frances—of course it was Frances. "No!" I began, "No—don't let her—"

But the door swung wider—and Natacha Czernick appeared behind the little nurse, who immediately turned and ran away down the hall.

Natacha's red mouth was wreathed in a smile of malicious triumph. She closed the door behind her, and I heard the grate of the key in the lock. Then she came toward me, her lissome, erotic figure swaying with brazen allure. She paused at my bedside while I glared at her speechless.

"It is tomorrow, Donald Corrigan," she said, "and now you believe..."

My eyes sank beneath the overpowering triumph in her glance. But I mustered what little determination remained in me.

"You're talking nonsense," I said. "I—I don't know what you're talking about."

Natacha laughed quietly. "Oh, yes, you do. You're too stubborn to admit it. Soon you'll be crawling to me, begging me to take you, to release you from your curse. And if you're wise, Donald Corrigan, you'll do it soon, before there are any more—accidents."

I raised my eyes to hers, stung by her taunts into taking a position I no longer believed in. "I still say you're talking nonsense," I snapped. "It was a perfectly explainable accident. It could have happened to anybody..."

But I couldn't believe it. I couldn't forget Peterson's inexplicable but very evident fear of me—the position of the fingers of his right hand as he lay there in the car, dying. The centuries-old gesture of the extended fore-and-little-finger—to ward off the deadly effects of the evil eye...

Natacha's attitude suddenly changed. She threw off her coat and seated herself on the side of the bed, leaned against me until I could feel the delicious, rounded contours of her body through the sheets.

"Would it be so hard, Donald," she breathed, "so hard to have me—to have my love—forever? I am wise, Donald Corrigan, wise in ways of love which these cold beauties of your country are too timid to imagine even in their most abandoned moments. We would know pleasures only the elect ever experience—a bliss too exquisite and dangerous for the common ruck of human beings..."

Brazenly Natacha Czernick had been unbuttoning the front of her gown as she talked, until her intoxicating body was revealed to the waist. Apparently she neither thought nor cared about the possibility of our being disturbed. I had the eerie feeling that, indeed, this room had passed into another dimension, and was invisible and non-existent to all mortals save ourselves. And once more the ineffable allure of this woman was sapping my will, robbing me of even the desire to resist her shameless blandishments...

As though of their own accord my arms reached out, my fingers thrilled to the contact with her satiny flesh. I slid my arms about her yielding form, beneath her open gown, and crushed her body against my own. Our lips met and clung in a kiss of rapturous, sin-steeped ecstasy...

Suddenly my nerves jerked taut to a ghastly sound which seemed to come from just outside my door. It was a high, unearthly scream, ending suddenly in a low moan of hopeless despair and horror, to be succeeded by a silence as grisly and ominous as that which had followed our terrible accident of the day before.

Flinging Natacha from me roughly, I sprang out of bed and dashed to the door, unlocked it, threw it open—and stood rigid in petrified terror. At my feet lay the little dark-haired nurse whose halting, timid voice had announced the arrival of my nemesis. In her white, slender throat was a horrible gash from which the red blood spilled out upon the porcelain tiling of the hallway.

I saw in an instant what had happened. Bearing a tray of retorts and glasses down the hall she had stumbled and fallen. One of the jagged pieces, which now lay in shattered profusion about her body, had stabbed her throat as she fell. She was dying as the blood welled from the horrid wound—dying with her eyes fixed upon mine, holding the same expression of horror-stricken accusation that Peterson's eyes had held the day before...

With a dreadful precision my gaze sought her right hand, then, knowing what I should see. And it was with a hideous sort of satisfaction that I noted the out-thrust position of the fore-finger and little-finger. There was no longer any room for doubt. I had become a menace to every living human being I encountered. I had no place in a world of strangely vulnerable, helpless mortals...

PERHAPS I might have been of some small aid to the dying

girl; but nurses and interns were running toward us down

the hall. I turned about and slammed the door. Ignoring

Natacha, who still lay on the bed propped up on one elbow

observing my movements with a wicked gleam deep in her

veiled eyes, I went to the closet and got out my clothes,

began throwing them on hastily.

"Now that you believe—and are even ready to admit it," she murmured,—"what are you going to do?"

I glared at her, and my eyes must have been those of a madman. "I don't understand what you have done to me," I said, "or how you managed to bring it about. But I do know that I never want to see you again—you or anybody else. I'm—I'm going away—far away where there aren't any people—"

I was raving, becoming incoherent with the confused images of terror and dread that flickered in my brain like a satanic kaleidoscope. Natacha laughed throatily—laughed as one might at the angry threats of a child one is confident of being able to calm in a minute.

"So you're going to leave us all—even the aristocratic Miss Dunbar—"

As though mention of the name of the girl I loved—and could never hope to see again—had conjured it, the telephone at my bedside suddenly buzzed softly. Flinging on my coat I strode to it just in time to snatch it out of Natacha's hands.

"Hello!" I barked into the transmitter.

"That you, Donald?" came the distraught, instantly recognized voice of the man I had hoped would be my father-in-law, Philip Dunbar. "I'm glad you've recovered consciousness—they told us your condition wasn't serious... It's terrible—our house is afire—and I'm afraid Frances is trapped. The upper floor is caved in—we can't get to her—"

I waited to hear no more. I dropped the phone and reached the door in a single leap. Down the hall was a little group of white-coated interns bearing a stretcher between them. I turned the other way, skirted a pool of blood on the gleaming floor with nausea tugging at my throat, and dashed down the hall in the direction opposite to that taken by the ministers to my latest victim.

I know not what sort of thoughts whirled in my brain as I raced through the streets toward Frances's home—I knew only that, cost what it might in more human lives, I must somehow make my way to the side of the girl I loved long enough to save her from the terrible death which was threatening her. It just couldn't be that I was bringing her perhaps an even worse death—God wouldn't permit such a ghastly travesty of justice as that...

While I was still blocks away from the Dunbar home I could see columns of smoke rising high in the air. Sirens still screamed all about me, as though every piece of equipment in the city were rushing to the scene. And as I drew nearer I could hear the roar of the flames above the excited shouting of the spectators. Oh, God, was it possible that Frances was in the midst of that inferno—and if she were, could she by any chance still be living?

I reached the edge of the throng, elbowed my way, head down, to the fire-line. There a brawny, red-faced fireman, and a smaller one—a man with a large mole on his left cheek—caught me by the arms, stayed my mad rush for just a moment. But I threw them off as though they were a couple of children and dashed on toward the fire.

There was no doubt about the center of the struggle. The south wall had collapsed, was a raging mass of flames, the heat of which met me like a palpable force as I rushed forward. Here a dozen hoses were pouring futile jets into the black smoke and flames—and here, I knew, must be the spot where my beloved Frances was trapped.

There was a confusion of yells and profane orders to get back as I hooded my coat over my head and dashed into that maelstrom. Then I felt the blessed shock of cold water against my back, and my body was forced through the barrier of flame by the powerful thrust of one of the jets. But my lungs were instantly seared by a draft of parching black smoke, and I sprawled on a wet but broiling hot floor, unable to see my hand in front of my face, and without the faintest idea of where I could find Frances.

Then a concentration of the jets tore a hole in the writhing blanket of smoke and fire, and I found I could see a little. I worked my way forward, stumbling over the smoking skeletons of chairs and tables toward the staircase which still stood, a prop for the ceiling of the first floor, which had collapsed against it.

Arrived at the foot of the stairs I glared about me, my eyes all but sightless from the acids and the heat. I knew I must hurry, must find Frances almost instantly—or no one would ever see either of us again.

Acting on a sudden inspiration, I made a dash for the rear of the staircase. There was a small coat-closet under there. Perhaps Frances had gone there for refuge...

But as though determined that I should not triumph, the flames suddenly leaped up about me with renewed energy, as the hoses were directed elsewhere. I felt a blast of fire in my face that I knew had removed my eyebrows as with a blowtorch. The searing agony of my scalp told me that my hair was aflame—and my eyes felt as though they had been gouged from their sockets with white-hot pokers, seared by hell's fire.

I threw off my flaming coat and made a last dash forward. Groping blindly along the stairwall my blistered fingers found a sizzling knob, turned it while the skin of my fingers slid as though greased on the metal. I fell forward as the door opened—fell on top of a prone, still body which I did not need eyes to recognize.

With a choked shout of triumph, I dragged down every wrap I could reach on the hooks of the closet, wound them around Frances's body, threw one over my head, and lifting her in my arms with a supreme effort, staggered back through the inferno of flames.

How I found the strength to do it I shall never know, but after what seemed countless ages of suffering and struggling I suddenly felt cold air on my charred and blistered face, felt strong arms seize my burden and my own collapsing body. I knew, then, that I had emerged from the fire, and that whatever else there was to be done for Frances others could now do far better than I. Then my strength left me—and with it, consciousness.

NO ONE has ever discovered what became of the woman

called Natacha Czernick. My butler had a strange

tale of having seen her on the very morning that

she left my home. The previous evening, following

her instructions—supposedly originating with

me—Gregg had gone to his apartment; and there, the

next morning, she had telephoned him, saying she had

orders from me that he was to meet her in the lobby of the

Drake House. But when he got there, he said, she had only

a fantastic story to tell him about my having the evil

eye—and that he would surety die if he continued in

my employ. So Gregg, the least superstitious of mortals,

had then gone to my home—only to find me gone.

But apparently two people, at least, had not been so immune to the suggestions of ancient peril which Natacha Czernick knew how to evoke so plausibly and convincingly. An humble, honest chauffeur, and a little nurse fresh from Yugoslavia, had been all too fearfully impressed by the warning. So impressed that, their nerves strung taut by superstitious terror, they had both lapsed momentarily in the performance of their duties—and suffered horrible death as a result...

Yes, it is all easily explainable, now that we know the methods Natacha Czernick used in her insane plot to capture my fortune through marrying me. Yet, when Philip Dunbar read me the accounts of the fire at his home, I felt an eerie chill run through me at one item. Two firemen had been killed in the collapse of the stairway just after I had escaped. At my instance Philip got a personal description of the two men from their respective companies. One was described as a tall, florid, heavy-set man—and the other was smaller, with a large mole on his left cheek. There could be no doubt about it: these were the only persons into whose eyes I had squarely looked from the time I left the hospital until I collapsed with Frances in my arms in front of the flaming ruins of the Dunbar home. And they had died...

So I find a certain measure of comfort in an affliction which many men would regard as a curse hardly preferable to death. I know that my beloved Frances is safe from whatever agency killed the last people I looked upon in this life—as safe, in a different way, as Natacha Czernick had seemingly been. And our love and wealth have transcended much of the dreadfulness and all of the loneliness which attaches to the state in which I was left by the fire—the state of total and incurable blindness...

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.