RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

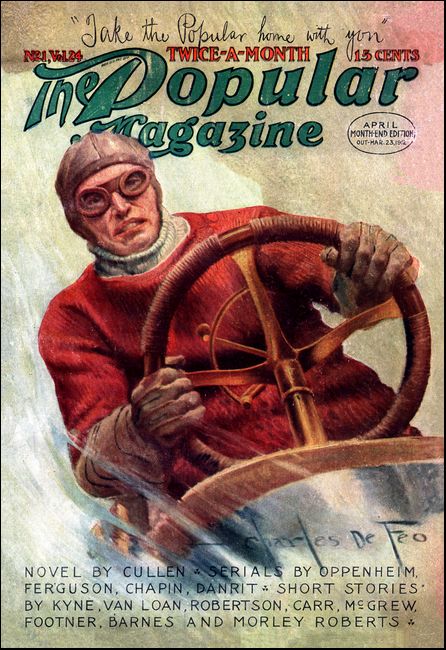

The Popular Magazine, 15 April 1912, with "The Way of the North"

Told by a freighter on the Pea-vine Prairie. The way of a woman in the untamed North. The freighter's philosophy—and it applies to every daughter of Eve, without distinction of race or color—was: "Take women as they come, and treat 'em right, and the proportion of good and bad is about the same." His yarn will interest you.

ON a breathless night in October, with every star, great and small, hanging out a separate signal aloft, three men were reclining by a fire on Pea-vine Prairie. The fuel was dry poplar, burning swiftly and softly, the flames mounting straight, and flinging up a geyser of sparks. Off to the northwest, where a silvery light lingered in the sky, the smoke of hours past could be seen still haunting the neighborhood, floating motionless in diaphanous veils a sapling's height above the grass. On the other side of the fire, a laden box wagon and a buckboard stood tongue to tongue in the grass; the horses had finished their first feed, and an occasional drowsy tap of a bell out of the void of darkness beyond was the only reminder of their proximity.

Two of the men had arrived from the West in the buckboard. Meeting the freighter at this point, with the easy fellowship of the trail they had camped in company. The two had been "looking over the land" with a view to immigrating; and the freighter, who had the nonchalant air of long familiarity with these trails, was good-naturedly letting the strangers tell him about his own country.

The principal speaker was a young man with a luxuriant, aggressive mustache, and a hot, brown eye. He was abusing the "niggers." He had no especial grievance against the natives, but it seemed to bolster him in his own esteem to rail. In particular, the mixed marriages he had observed excited his scorn. This is a delicate subject in the North, and the freighter became a little restive as he listened, though his expression remained polite.

"None of them brown girls'll ever get her hooks into me, sir," the traveler was saying. "Beaver or Cree, full blood or breed, they're all alike, and the damnation of a man! Every one of 'em plays for a white husband, 'cause she thinks they' don't like to wield a stick on a woman. But that's what they need.

"There's Mert Heywood," he went on. "We spelled at his place for a week to help with the threshing. Mert has fifteen good cows, and there was condensed milk on the table 'cause the squaw won't milk. And, by gad, sir, when we come in from the field at noon, we had to turn in and cook the dinner 'cause the woman was off in the tepees somewhere!

"Then there's that fellow down at the foot of the lake—Dick Foster I think they call him. It's took him a different way. He's as furtive-like and walleyed as a redskin himself. He won't have nothin' to do with his own race no more!"

The freighter was shaving his plug ruminatively. He was a tall, rawboned young man, with a shock of intractable red hair. As he bent over to start his pipe with a coal, the fire illuminated an instantly likable face, informed by good sense and good humor. He had the eyes of a friendly soul, whom no fool would yet be likely to presume upon.

"I know the Heywood and the Foster outfits well," he at length interrupted. His voice was mild, but it silenced the other. "I've also seen plenty of outfits outside with a white woman runnin' them and no better off. Why blame the women at-all? Mert Heywood's a good fellow, but everybody knows he's as slack as punkwood—I have told him to his face. As for Dick Foster, he always had a strain of the savage in him. He took to tepees as natural as a duck to the sloughs."

"Then you're all for these mixed marriages?" suggested the stranger sarcastically.

"Not at all," said the freighter quietly. "I wouldn't lay down no rule either way. It's a question for every man to put to himself when his time comes. My point is just this: Take women as they come and treat 'em right, and the proportion of good and bad is about the same."

"I've yet to meet a good one that had any red in her," said the stranger.

"So?" said the young freighter. "Well, I knew a fellow met with a good one once. Like to hear the yarn?"

"Sure!" they said.

The freighter flung his sheepskin coat over his shoulders to keep his back warm. He braced himself against his roll of blankets and extended his stockinged toes to the warmth. The inexhaustible fountain of bright sparks held his reminiscent eyes, and he told his story to the fire.

"His name was Jim Rennick," he began. "He come into the country about five years ago, expectin', like many another young sprig, to pick gold pieces off the bushes like berries, I guess. And he found, like the rest of them, that it required good hard scratchin' instead. And after grousin' around a while, like they mostly do, and cursin' all and sundry, he went to it like everybody else, and found it weren't such a bad life, after all.

"The girl's name was Beulah. She was the daughter of old Dave Kidd, the white man who kept the first little trading store at the foot of the lake years ago. He was a square old head, they say, and aimed to bring up his children white; but when Beulah was eight years old he up and took the pneumonia, and snuffed out in three days. His squaw brought the kids back to the tepees of her own folks across the river.

"In two years, the widow had married Ancose Mackay, a breed from down the river. She went out to the Landing to live, and left her kids behind to be kicked from one tepee to another, and fed the last when grub was scarce. Especially Beulah, because she couldn't forget all the white ways she was brought up in.

"Beulah happened to be pretty. Already, when she was fourteen years old, the fellows up and down the lake were talking about it. I may say she was damn pretty; and a man didn't have to exercise his imagination to see it. Her skin wasn't no darker than rich cream, with pink checks and brown eyes that always had something surprised and painful like in them, though she didn't mean it that way. But I ain't no hand at a description. Say, she was prettier than that. Why, when Jim Rennick first took notice of her, she was as delicate and ladylike as one of them crocus flowers that comes up through the snow. She was sixteen at the time.

"It happened this way: Jim was walkin' around the south side of the lake, and he made Wall-eye Macgregor's tepee for the noon spell. Walleye was her uncle. There was nothin' white about the old blackguard but the name he claimed. The girl was in the tepee, and there was another white man there. I won't name him to you. He's well known in the country, but this story ain't never got about on him. Great, big man. The girl was cryin' quiet like, and it come out that this other fellow had offered old Wall-eye a sum down in cash for her, which Wall-eye had accepted, and the fellow was goin' to carry her up the lake afterward in his Peterboro.* There are funny things happens in an unsettled country; but I never run into such a raw deal as this before.

* A wicker basket. R.G.

"You understand, this ain't no love story. Jim didn't feel no particular call to the girl then; she was too young. But it made him feel like hell to see the big tears chasin' down the kid's face, and her not sayin' a word; and that big, fat—Well, he invited the other fellow outside, and, without gettin' excited at all, he told him what he thought of the deal. When the other fellow laughed sneery like, Jim, he stretched him flat before all the natives, and carried him down to the water and threw him in in his own Peterboro.

"When Jim was gettin' in himself, the girl caught holt of him. Say, her eyes were bright and her cheeks all red—but Jim couldn't face her. She wanted to thank him and didn't know how; and he didn't want to be thanked, and didn't know how to get away. It was an embarrassin' moment. At last she said:

"'You ver' good man. I never, never forget!'

"Just about then Jim was wishin' the ground would open up and swallow him.

"Jim paddled that fellow clown to the foot of the lake, and he never troubled Beulah again.

"I can just skim over a lot that happened after that. It has mostly to do with Jim Rennick's luck. Up to this time, Jim had been anybody's man; freightin' a little, prospectin' a little, trappin' a little, pickin' up a meal here and there. But now he begun to feel it was time he made a stake of his own. And say, everything he touched went to the bad. It got to be a saying up here for the worst that could happen to a man: 'Jim Rennick's luck.'

"First he was for keepin' a stoppin' house for freighters on the winter road. He hired Jacques Tremblay's shack and stable at Nine-mile Point, and borrowed Dick Foster's mower to put up hay at the foot of the lake. Forty ton of blue joint he stacked there by the little river, and when he went back up the lake one night it all went up in smoke! It was said around that Dick Foster himself set it because he didn't want no competition so near; but there was no proof. Jim had the satisfaction of knockin' a couple of Foster's teeth down his throat, but that didn't give him his hay back. And it was too late to put up more that season.

"Then he took to tradin'. He got a small line of goods on credit from the French outfit, and opened up at the foot of the lake in the same place where Dave Kidd had traded years before. But the devil was in it. Just before the river closed, a fellow come up with a barge load of stuff, and opened up in opposition. He could sell at Prince George prices plus the freight, while Jim was bound by contract to keep up the French outfit's figures. So the freetrader got all the fur there was, and Jim's stuff still decorated his shelves in the spring. If that weren't enough, that year didn't the lake rise higher than ever was known before, flooded Jim's store, and spoiled the layout! He come out of it with a debt of eight hundred to the French outfit.

"Now, up here in this country a man has to be careful not to get any particular idea fixed too tight in his head. He's got so much time by himself to think about it that it grows and grows until it crowds all sense out, and he goes plumb loony. Jim begun to think there was a kind of blight in him that withered everything he put his hand to. It got to be a fixed idea at last; a shape of fear as real to him as might be a black wolf that followed him along the trails, squattin' by his fire at night, and waitin' there in the morning to mock him when he opened his eyes.

"But he worked—oh, yes. That was all he could do to forget it. He got to be considered such a worker that when the ice road formed again, even with all he owed them, the French outfit staked him for a team, a right good team, costin' five hundred in Prince George.

"He spared neither himself nor his horses, and he got in three round trips to any of the other freighters' two. Prince George to Caribou Lake Settlement was his route; a hundred miles overland, seventy-five up the ice of the Miwasa, sixty on the little river, endin' up with a seventy-five-mile stretch up the lake in the teeth of the blizzards. He soon got a reputation for makin' the best time, and worked up a good express business on the side, gettin' three times the regular freight rate for small packages. On the return trips, he bought whitefish from the Indians, carried them out frozen, and sold them for good prices in town. Out of this and that he cleared off his old debt, and come March had almost paid for the horses as well.

"When I say he didn't spare his horses, I mean he worked them to the limit, but not so hard as to dull their shiny coats any, or make their round flanks to fall away. Seems like a man is healthier-minded if he's got something to get foolish over. Jim fussed over them horses like they was babies, rubbin' them, and blanketin' them, and feedin' them choice. And he almost forgot the black beast on his trail.

"They was a comical pair, and many's the laugh Jim had at their wise ways. He called 'em Mary and Jane. Mary was a bright bay, with a willin', sweet-tempered disposition, while Jane was a true buckskin, with a black stripe down her back and as independent as a pig. Mary followed at her tail wherever she led; and she had a rovin' tendency that furnished Jim a lot of exercise. A word was enough for Mary; but Jane was the better for a flick of the whip. But ain't it curious? It was Jane with her independent ways that he liked the best; and he was as proud as a lord when he could make her hang her stubborn old head, and come whinnyin' and nosin' after him for apples.

"But this ain't no part of the story. Jim left Prince George on his last trip—March twelfth—with a load of rush groceries for the lake. It was mostly fancy stuff and a lot of express packages; and the load was worth, as it stood, near fifteen hundred dollars. The freight on it, Jim figured, would just about square him with-the French outfit and make the horses his own.

"The day after he left it turned warm, and it was thawin' all the way. When he got to the lake, he found five gyppos* who had started before him hung up on the shore. The ice was full of soft spots and dark with standin' water. But Jim he knew ice, and his reputation was at stake besides. So he started, and he was right to start; there was no particular danger then. But it kept gettin' warmer.

* Loggers. R.G.

"The winter road cuts straight across to Nine-mile Point from the river, and then follows the south shore of the lake for twenty miles or so to Fisher Creek and Cardinal's Point. Then she makes a bee line across the narrowest part of the lake, and keeps to the north shore as far as Grier's Point. All this was good enough going, Jim made Cardinal's Point the first night, and Grier's Creek the second.

"There was a little frost the second night, and the next morning broke clear. Roundin' Grier's Point, the ice road heads across a deep bay to the mouth of the Elbow River, and up the river a piece to the French outfit's warehouse. From the Point, Jim could see the buildings five miles away in the clear air, and his heart swelled big in his breast. Reachin' it meant he would be a free man again, with a team of his own as a stake against the future. He was not thinkin' of the black beast then. The horses, they seemed to sense something of what he felt, too, and tossed up their heads and trotted with the load.

"Thinkin' about all this, Jim got careless of the dark spots half showin' through the snow. Halfway across to the river they went in. The horses got across all right, but the loaded sledge sank through the soft stuff with scarcely a crackle.

"Jim jumped off, and with his ax hacked at the traces like a crazy man. But he had no chance. A big piece broke off and sank under the weight of the sledge, and the black water welled up all around the edges. Jim and the horses were pulled in. Jim couldn't swim. He went under more than once, still pullin' at the traces. He was kicked almost senseless by the horses. It was soon over. She went down slow like. The water ran in between the cracks of the boxes, and then washed over the top, and the horses were pulled down like they had stones tied to their tails. At the last only their strainin' heads showed, and then their stretched and quiverin' nostrils.

"When Jim come to, he found himself lyin' on the ice at the edge of the hole. God knows he wished he'd gone down with the outfit. The only thing that remained of his fifteen-hundred-dollar load was two little wooden boxes that had fallen off the top when she first lurched over. They looked funny lyin' there by themselves on the ice three miles from shore, and nothin' to show how they come there. Macaroni it was, I mind, with them gaudy-colored Italian labels. But it wasn't the load he was thinkin' of. He could have taken the loss of that cheerful enough so he had his team—Mary and Jane—most human they were.

"When life begun to come back to his sore and drownded body, say, the pain was like ground glass runnin' through all his veins; and was nothin' to what was in his head. Because he knew he couldn't help but go loony now. There was a kind of regular, slow swing in his head that beat out: 'Mad! Mad! Mad!' with every stroke.

"The fellows at the French outfit store said he come walkin' in quiet like, with the face of the dead and all wild-lookin'. They couldn't get a word out of him; but they knew without askin' what had happened. There wasn't nothin' anybody could do. They believed, like himself, there was an evil fate in it, and the thought showed in their faces. Only Smitty, the trader, he dug up a little jug of rotgut they was savin' for the twenty-fourth of May, and give him a drink. It was a kind act.

"Say, the raw burn of that stuff runnin' down his throat felt good to Jim. It made a confusion in his head so's he couldn't hear the hammerin'. He drunk until he fell down on the floor. They let him sleep there by the stove. It was near mornin' when he woke, and he was alone in the store. He lay there for a while feelin' sick like, and slowly piecin' together what had happened. Then it all come to him, and he heard—a good ways off at first—that swingin' like a pendulum: 'Mad! Mad! Mad!'

"He ran out of the store, huggin' the jug under his coat. He ran daft like along by the shore to his own shack, which stood by the summer trail near Grier's Point, a matter of six mile from the store. He bust in the door, and tumbled in. It was cold and moldy inside; the floor had rotted into holes, and the mud chimney had fallen down in a heap, lettin' in a world of snow. It was a fit hole for a sick man to crawl into.

"He lay there for two days without eatin'. Every time the swingin' began in his head, he took a pull out of the jug. The third day she ran dry, and, as the noise in his head got louder and louder, and there was no escape from it, he got in a panic like, and ran out on the ice with his old ax to chop a hole. The water rose up in the hole black and shiny and cold, and he couldn't do it. He tried closin' his eyes and steppin' off the edge. He went back a ways and took it on the run—but he couldn't do it. He pictured himself risin' under the ice and knockin' his head on it, and scratch-in' underneath it with his nails.

"So he went back to the shack for his thirty-thirty. He cleaned it careful, like a man who knocks off work for a day to get a moose. Then he rested the butt against a tree and leaned against the muzzle. He couldn't reach the trigger good, and he got a little stick to push it with. But he couldn't do it. It wasn't his nerve, but his muscles that failed him. He could bring his arm up. He could rest the stick against the trigger; but he couldn't make himself bear so much as a thumb's weight on the stick.

"So he thought up a scheme to set off the gun automatically. His brain worked it all out so cool and true he knew he must be mad for sure. He took off his buckskin shirt and cut it into strips to tie with. He cut half a dozen poplar poles; then he chose his spot, and set up two tripods close together to hold the gun pointin' at the level of his chest. He put in a soft-nose bullet to make it surer; then he lashed the gun on the tripods. She was aimed at two fair-sized poplars that grew close together about twenty feet from the muzzle.

"Behind the tripods he planted a branch of willow in the earth. He put a long thong on it, and, bending the branch forward, staked it to the ground. Then he tied another string from the trigger to the top of the branch. Then he laid a fire very careful on the ground under the tight thong: dry shavings, then splinters, then small pieces of wood, then larger pieces. The idea was to make a fire that would catch slow and steady. When she got going good, the thong would burn through, and the willow branch spring back, dischargin' the gun.

"He twisted and knotted the rest of the buckskin strips into a lariat fifteen, eighteen feet long. When it was ready, he put a match to the shavin's, and ran for the two trees the gun was pointin' at. He figured on three or four minutes before the thong would burn through. He put his back against and between the two trees, passin' the rope under his arms and around behind the trees as often as it would go. Each time round he pulled it until his ribs squeezed in, and knotted it good. He had thrown his pocketknife on the ground, so's he couldn't cut himself out if his nerve failed him at the last.

"Then he looked at the fire. She was awful slow startin'. Away in the middle of the pyramid of sticks he could see a lazy little flame that rose up and went down again without gettin' any grip. Once he thought it had gone black out. Lord! but he was discouraged at havin' to do it all over. But a breath of wind come in off the lake, the little sticks caught, and at last a flame came snakin' through the top of the pile, and he knew it was a go. He couldn't move up or down. He couldn't squeeze around the two trees. He couldn't untie the knots in time. So there was no chance, and nothin' bothered him no more.

"The little fire begun to crackle. It charmed his eyes like a snake charms a bird. He saw the thong that was stretched above it blacken in the smoke, and then, as a flame licked at it, he saw it stretch and shrivel. He was sorry he had made it so thick. Then the willow branch began to tremble, and he knew that a second or two would end the game. He closed his eyes and tried to pray, I guess.

"He heard a kind of rushin' sound, and the gun exploded. But there he was still. He had to fetch back the idea of livin', as you might say. It was painful. He opened his eyes, and saw a woman standin' in front of him. Her face was a deathly yellow, like buckskin, and her eyes burned like two coals at the back of her head. It was Beulah Kidd.

"They stood lookin' at each other for a full minute, I guess. Jim was sore, and the girl was shakin' all over, so she could neither move nor speak. At last he told her to cut him loose; and she picked up his knife where it lay, and did it. Then she went sly like to the gun and cut the strings that held it. She emptied the magazine, with a scared look at him over her shoulder, and put the shells in her pocket.

"But Jim had a-plenty more in the shack, and he strolled in careless like and got them. When he come out again, at the first move he made to load the gun, she flew at him like a she animal with young. She tried to pull the gun from him, and he laughed, because he knew if anybody tried to stop him, that was all he needed to nerve him to pull the trigger on himself.

"She was no match for him. He pushed her away, and she fell on the ground. All this time she did not say anything or cry out at all. They have a wonderful gift of silence. Her face was like a dead woman's, only the eyes. But when he made to load the gun again, she half raised herself, and held out her arms to him.

"'Jim,' she said, all hoarse like, 'give me a bullet first.'

"Just that was what she said. And it made him look at her very different. 'What in hell do you want to kick out for?' he said roughly.

"'I love you,' she said.

"Say, that was a staggerer. He dropped the butt of the gun on the ground, and stared at her like he couldn't believe his own ears. 'Me!' says Jim. 'Me!' And he laughed.

"It was all mixed up after that. She cried and carried on as a woman will do when she lets herself go, swearin' he was not the poor loon he knew himself to be, who blighted everything he touched, but the finest fellow in the world, and so forth. He listened in a kind of stupor. It hadn't never occurred to him that any woman could value his ugly carcass, and it changed his outlook considerable. He couldn't doubt it, because it seemed, soon as she heard from a freighter what had happened to Jim's team, she started out to help him. Her folks were camped up Fisher Creek at the time, and she had walked until she came to Jim's place, near fifty mile.

"Jim forgot that he was supposed to be mad, and just looked at her and wondered at how pretty she was, all cryin' like and forgettin' herself, and what a mate for a man, what a fit mate!

"Put yourself in his place. There he was crazy to end it all, because he'd lost faith in himself, and nobody gave a damn, and now it seemed there was somebody who set a heap of store by him, and believed in him, too. Say, it warmed his heart better than whisky. All this time she was creepin' close to him afraid like; and at last she took the gun out of his hands, and he let her.

"'Would you marry a down-and-outer like me?' he said, very bitter.

"'Not go to church,' she said low. 'I didn't expect it. But just to work for you, Jim. You could send me away any time.'

"That finished him. He couldn't look her in the face for shame. After that he was like a great baby in her hands. She cooked and made him eat. She brought hay from the stable, and made him lie down and sleep.

"When he woke up, his manhood had come back to him, and he was ashamed of his past foolishness. He took that girl by the hand and marched her into the settlement and up to the parson's house, her hangin' back all the way.

"That's the end of the story. How it turned out is a matter of common knowledge in the country. If you don't believe she changed Jim Rennick's luck, ask the first man you meet on the trail how about it."

When the two partners turned out next morning, they found the young freighter had gone his ways before them. He of the aggressive mustache affected to be unconvinced by the story they had heard, and commented scornfully upon it during their morning's ride. They made Pierre Grobois' stopping house for the noon spell. The incredulous one referred to their meeting on the road.

"Who is the freighter we camped with last night?" he asked old Pierre. "Must have passed by here yesterday. Tall, lanky young feller, with a cool, blue eye."

"Jim Rennick," answered their host.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.