RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Blue Book, July 1935, with "The Blue-Nosed Vampire"

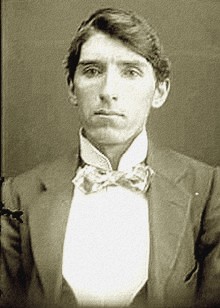

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

THE night, heavy, thick, and strangely personal, shouldered the lonely bungalow of Jan Kromhout, the big Dutch naturalist. Far off, beyond the thirty-mile stretch of jungle, sheet-lightning played over the Sawah Mountains, suggesting the attempts of astral photographers to take flashlights of celebrities on the low-swinging planets.

There was no wind. It was the last week of October; the east monsoon had died down, and the west monsoon that ushers in the rainy season was overdue. In this transitional period—known locally as the "canting" of the monsoons—there are strange irregularities in Javanese weather.

From the bungalow there filtered out into the listening night the protesting litany of imprisoned things: The weird cry of the wou-wou, the dry cough of the lutung, the teeth-grating swish of restless lizards and snakes that were compulsory guests of the big naturalist. And with the low chorus of the captives came a pathetic undernote: A little maroon-tinted hanuman monkey had lost her baby that afternoon, and now she cried pitifully in the darkness.

Jan Kromhout sprawled in his big chair on the veranda, a bottle of schnapps and a tumbler resting in the circular openings specially cut in the arm-rests. The night, by its rather aggressive and eavesdropping quality, forced him to be unusually talkative.

"There are countries that look nice and beautiful and friendly, but they feed on men who are not born to them," he said slowly. "They are eaters of flesh. Ja! They are eaters of souls. They are cannibals that consume the flesh and the spirit. This country, Java, is one of them."

Jan Kromhout had a peculiar manner of expressing himself. He thrust an assertion into the conversational ring, so to speak; then, after waiting for a few minutes, as if hoping for contradictions, he proceeded to back up the introductory statement by an amazing narrative. If the slightest doubt was hurled at the affirmation, one never heard the story.

"There are many clean countries in this world," he began. "There is North America from the Bering Sea down to the Rio Grande. And there is Europe, and the southern part of Australia. A little bit of Africa around the Cape, perhaps. The rest is not too clean; but it is the East, and particularly the Malay, that is bad. Ja, particularly the Malay.

"You have seen those plants that botanists call Drosera, but which ordinary folk call sundew? They are flesh-eaters. They are short of hydrogen, so they catch flies and small insects. They put nice syrup on their tentacles, and when a fool fly takes a sip, he goes on the menu. It is the same with the Malay. Just the same. But often in this place the human fly does not know that he is being consumed. Very often.

"I will tell you a strange story. It is one that you cannot tell on Broadway or Fifth Avenue, because you must have the atmosphere. It would be unbelievable without the things that are around us tonight—the odors and the heaviness and the mystery. The air of your United States is too thin, too clean, too— What is that word that you say about everything American? Ja, that is it. It is too hygienic. Everything is so hygienic in your country. That is good, very good. Here the filth of the centuries is sitting on the doorstep. The place has the quality of the Drosera. It is flesh-eating.

"Belief is a matter of finding things to act as mental digestives. When you see water that is supposed to run uphill, because Krishna wanted a drink and was too lazy to go down to the stream, it helps a little in this business of believing. When you see a tiger that was turned into bronze as he was springing upon Buddha, it helps a little. And when you see native women taking offerings to the Sacred Cannon at the Penang Gateway because they think it will bring them children, you are getting ready to swallow a lot. You are cultivating the digestion of the East....

"Five years ago I was trapping at a place beyond Papandagen. It was a lonely place. Sometimes in the hush of noon I would think that all the peoples of the world had died suddenly, and that I was alone. It was frightening. The loneliness was a thing that walked with you. Ja, it did. It breathed; it whispered; it touched you with fingers that were the fingers of the dead.

"While I was trapping in that place, there came up the valley an American. He was from Richmond, Virginia, and his name was Kenyon: Jefferson Lee Kenyon. He was a rich sportsman, and he had been all over the world with his guns and his rifles. He had shot everything that walked or flew, from the white rhinoceros to the big bats of Java that we call Kalongs.

"This Kenyon was the finest-looking man I have ever seen. Six feet and a bit, with broad shoulders and the waist of a woman; and he was so hard and so tough that he did not know fatigue. Neen. He would tramp fifty miles through the jungle in a day; then, after he had his supper he would say: 'I must have a little exercise before I go to sleep. It is bad, Kromhout, for a man to go to bed without a little exercise.'

"'But you have walked fifty miles!' I would snap.

"'Oh, that is nothing,' he would laugh. 'I feel funny unless I stretch my legs.'

"Kenyon had a white servant who waited on him. And he had a Chinese cook, and he had five native servants. Three of those natives were Sundanese, and the two others Madoerese.

"Those five natives did nothing but talk about the strength of that American. They would argue about it amongst themselves. They thought it was not right, that it was queer. To them, it was the strength of a god. When they were so fatigued that they could hardly pull their legs along, that American would say: 'Let's walk a little faster. We are moving like sore-footed lemurs.'

"Those five looked for an explanation for Kenyon. Ja, and they found it. In a ruined temple, about a mile from the camp of that American, the five found a stone statue that was the statue of a hunting god. A terrible fellow, nine feet high, a big spear in his right hand, and the left hand raised and turned outward in what is called the abhaya mudra pose, which means: Fear not, all is well.

"The five thought that Kenyon was the god born again. They were certain that he was. It was a simple way of explaining his strength; it also made excuses for their laziness. How were they to keep up with a god who would not get tired if he walked a thousand miles?

"I heard of that belief. One day I went into that ruined temple to get out of the heat of the sun, and I took a look at that stone god. I was surprised. Ja, I was much surprised. No one had taken any notice of that god for hundreds of years; but now, suddenly, he was what you call popular. Mighty popular! There were little heaps of rice-powder and tapioca, and packets of cinchona, around his stone toes; and there were blossoms of the Rafflesia and the ylang-ylang hanging on his arms. I knew what they were. They were offerings of the native women to the god whom they believed had come to life in the person of that American—possibly from childless women who were in disgrace because they had no children.

"At times I thought I would tell Kenyon about that business, but I stopped myself with the words on my lips. I thought he might be worried if he knew of the offerings, and so I kept quiet. Three times I went into the temple and hid behind the stone pillars. In the gloom I saw half a dozen native women slip in, one after the other, lay their little offerings at the feet of the god, and glide away noiselessly. Some of the women I recognized ; others I had never seen before.

"It was three weeks after I had first seen the offerings that Kenyon came over to my little bungalow. He sat around for a while without speaking, but I knew that he had come to tell me something. He had the look of a man who is ashamed to confess. He looked like a little boy who has stolen some plums.

"'Kromhout,' he began at last, 'you have been out here a long time, haven't you?'

"'Ja,' I said. 'I have been out here so long that sometimes it is hard work to make myself believe that I am a Dutch cheese-head born in the shadow of the Oude Kerk at Amsterdam.'

"He did not speak for some minutes; then, with his face turned away from me, he said: 'I have come to ask your advice.'

"'You can have it,' I said. 'Have some of the boys been stealing food?'

"He swung round on me and snapped out his answer. 'Some one is stealing the food, all right,' he cried; 'but the food is me!'

"I did not understand what he meant by that, so I waited. 'Listen,' he said, 'some one—who the devil it is I don't know—is feeding on me! Feeding on me! Oh, damn! It seems silly to tell you, but I've got to. You are the only white man except my fool valet, and I've got to speak about it. Some one is feeding on me while I sleep! Taking the strength out of me!'

"'It is a touch of malaria,' I said.

"'Rot!' he cried. 'Do you think that I don't know what malaria is like? This —this is human! Something—something of the vampire order!'

"I looked at him as he sat in the sunshine: A big man in shorts and khaki shirt, sun-helmet, and boots of porpoise hide. He was a fine man, that Kenyon.

There is a painting of one of De Ruyter's captains in the Rijksmuseum at Amsterdam. A big fearless man. Always when I looked at Kenyon, I thought of that fellow that had sailed with De Ruyter. They were much alike. They were men who spat in the eye of the world, and laughed as they did it.

"'Tell me,' I said to him.

"He started to speak quietly to me. His temper had passed. He was facing that business as he would face a tiger. He had nerves of steel, and although he was puzzled, he was not scared. No, he was not scared.

"HIS story was very strange. For seven nights he had been wakened just after midnight with a sharp pain in the left shoulder. When he grabbed his torch, there was nothing in his tent; but he had a feeling that some one or some thing had been sucking the strength out of him while he slept. Sucking the force out of him—the vigor that puzzled those natives.

"'It is the most terrible feeling in the world,' he said. 'The most damnable feeling. It is like a creeping death. I have to crawl back to life when I wake—crawl back like something newborn.'

"'Do you hear anything?' I asked.

"'It's funny,' he said. 'Each time as I'm crawling back to life, I have heard the tinkling of a little bell—faint, very faint. It is gone before I am fully awake.'

"'Let me see your shoulder,' I said.

"Kenyon stripped back his shirt. Just beneath his left shoulder-blade were seven marks of a faint scarlet color. They were in a straight line, about one inch apart, and it was easy to tell the new ones, because they were of a more brilliant color.

"I got a magnifying-glass and examined those spots. I was interested. Ja, I was very much interested. Each one of those marks was the size of a man's thumbnail, scarlet, as I said, with the center a deeper tint. And that central spot looked like the thrust of a single tooth. A single tooth! That was funny—damned funny.

"Now, I did not believe in human vampires. I knew much about the bloodsucking bats. Desmodus rufus and Diphylla ecaudata, that we call vampire bats. Darwin has written of that fellow Diphylla ecaudata. He is bad, very bad. His teeth are built so that he can pare off a piece of skin the way you do when you shave too close, and then he sucks at the small capillary vessels that are exposed. He is clever. He has to have blood, that fellow. His gullet is so small that nothing solid can pass through it, and he has no money to buy milk or schnapps to keep him alive. So he must get blood, or starve to death. But those marks on Kenyon's back were not made by bats. Neen.

"'You have been bitten by something,' I said, 'but I do not know what that something is.'

"'It is human,' said Kenyon, looking me squarely in the face.

"I shrugged my shoulders. What could I say? I had no explanation to offer. There were seven marks where something had bitten him seven nights running; and if he thought they were made by a human being, why should I contradict him? Around us were leagues and leagues of country in which funny things were happening every day. Very funny things! This Malay is the mortar in which the devil mixes his drugs. Ja, I know.

"We sat there in the hush of noonday, and my mind went over all the tricks of the Malay pawangs. Those medicinemen, after tney have doped themselves with drugs, become possessed of the tiger spirit. I have seen them do things that I could not explain, but those marks on Kenyon's shoulder did not look like the work of a pawang. Not much. The thing that was biting the American wanted strength; it wanted force. It wanted the vitality that allowed that fellow to walk fifty miles without tiring.

"I thought of the stone statue in the ruined temple—of the childless native women slipping into the gloomy place with their little offerings. I thought of all that, as I looked at Kenyon, so big, so strong, so splendid. And I was a little afraid—just a little afraid.

"'Why don't you sleep here tonight?' I said.

"'I'd like to, if you have room,' he answered.

"'I'll make room,' I told him. 'But don't let any of your boys know that you are sleeping here. Slip out quietly after you have had your dinner.'

"He came over to my bungalow about nine o'clock. He was just a little solemn when he arrived. He did not like those bites. They made him mad. It is not nice for something to nip you like that when you are asleep.

"I fixed him up a cot in a small room where I kept my specimens. The window was screened, and there was a bolt on the door. 'Nothing will bite you here,' I told him. 'You will sleep well.'"

JAN KROMHOUT paused in his recital, lifted himself from his chair and entered the bungalow. He spoke softly to the little hanuman monkey that had lost her baby, and when her moanings died down, he returned to the veranda.

"I must have been asleep for two hours or more," said Kromhout, again taking up the tale. "It was noises in Kenyon's room that roused me. He was moving about, and I saw the flash of his torch beneath the door. I jumped up quick and called out to him. He flung back the bolt, and I stepped inside the room.

"'I've been found, Kromhout,' he said quietly. 'Got nipped again. Look at the window.'

"He held up the torch, and I saw the window. The wire screen had been torn away at one corner, so that there was a hole big enough for a good-sized dog to get through. The tacks had not been pulled out. The wire had been torn.

"'Didn't you hear the tearing of the screen?' I asked.

"'No,' said Kenyon. 'I heard nothing but the faint tinkling of a bell as I tried to wake. I found then that I had been bitten. Look at my shoulder, will you?'

"I swore softly as I looked at his shoulder. Ja, he had been bitten. There was a fresh mark exactly in line with the others. Exactly in line.

"IT was a queer business, very queer. We Dutch have a proverb that says: 'Geen ding met der haast dan vlooijen te vangen.' It means that you should not do anything in a hurry except catching fleas; but there was something bigger than a flea biting Kenyon, so he would not listen to me when I told him to move slowly. Ach, he was raging!

"He grabbed his revolver and charged out into the dark night. He was so angry that he would have fought all the devils in the Malay. Devils and tigers and vampires! Never have I seen a man as angry as that American.

"I chased him as he ran around the bungalow. I was a little scared. I could not understand that torn screen. It was in my mind as I followed that fellow through the darkness. The darkness that had a laugh in it! Do you understand? The Malay was laughing at Kenyon and myself—laughing like the flesh-eating plants when they are eating up the fool flies that are clutched by their tentacles.

"Kenyon circled the bungalow twice; then he started for his own camp. I followed him through the black night. Lawyer-vines tripped me up a dozen times, but I was close to him when we got to his tents.

"Those servants of his were asleep, but he dragged them out so that he could feel the bedding to see if it was warm. It would have been bad for one of those boys if that American had found cold blankets. He was insane with temper. He wanted to kill some one to cool himself off. He just hoped one of those natives would give him an excuse to strangle him....

"When it was daylight, I brought him back to my bungalow. I was afraid to leave him alone. His pride was hurt. I thought to tell him about the stone statue in the temple, and the little offerings that the women brought to it because they thought the god had come alive again in the person of Kenyon, but I was afraid to tell him. I think he would have gone to the temple and smashed that god into a million pieces if I had told him.

"He could not eat; he could not drink; and he would not sit five minutes in the same place. And around us was the Malay, breathing quietly as it is breathing tonight, watching the human flies that are tricked by the nice syrup it spreads for them. It is a giant Drosera, this Malay. It is the cannibal land.

"I begged Kenyon to stay with me. I was afraid that he would do something silly, if he went back to his camp. 'The thing knows that you are staying with me,' I told him, 'so you can shoot it as easily here as you could at your camp. And it is just as well to have a white witness. It is silly to kill without having a friend to swear that you did it in self-defense.'

'"Listen, Kromhout,' he cried: 'I'll never close my eyes again till I fill that thing with lead. No more sleep for me till I get it, whatever it is, man or beast.'

"I had a madman on my hands. Ja, a fine madman. The best specimen of an angry man I have ever met. For five days and five nights he did not sleep one wink. He would lie in the dark on his cot, waiting for that something that wanted some of his fine strength. In the dark, but with his eyes open and his gun in his fist.

"Twenty times in those five nights I crept to the door of his room, but he heard me. 'All right, Kromhout,' he would say. 'I'm awake. Nothing doing yet.'

"His pride and his anger kept sleep away. I wanted him to sleep during the day while I stood guard, but he wouldn't. He was pig-headed. He wanted to be the one who would catch that bloodsucker when he made another call.

"I went to that ruined temple three times. I thought I might find out something. I crouched in the gloom and watched those soft-footed women sneak in with their little offerings. They were like ghosts in the half-darkness of that place. Ja, like brown ghosts. They made no noise. They slipped up to the statue that they thought was Kenyon in his godlike state, placed their rice powder, cinchona, or flowers, at his feet—and then padded away.

"There was one woman, slim and supple and beautiful. I saw her in the temple twice. She made little prayers when she brought presents—little whispered prayers to the stone god. I thought she was complaining about something.

"THE afternoon of the sixth day of Kenyon's watch I was in the temple when that slim woman came in. I was hiding behind a big stone pillar—quite close to her when she knelt. I heard her prayers: She wanted a child, a man child. She wanted one that was strong and beautiful. She told all this to the god. In the silence of the place you could hear her faintest whisper.

"She was rising from her knees when she said something that startled me—startled me a lot. She looked at the god with her big black eyes, and she said in the softest whisper: 'But you do not sleep! O Holy One, you do not sleep!'""

AGAIN Jan Kromhout heaved himself out of his chair and entered the bungalow. The whimpering of the little hanuman monkey that had lost her baby disturbed him. In a few minutes he returned with the small mother in his arms. He stroked her and talked to her, and when he seated himself, the monkey curled up on his lap and fell asleep.

Kromhout took up his tale.

"When she left that temple, I followed her," he said, his voice lowered as if a little afraid lest the listening night might not approve of his conduct. "Followed her through the jungle! She did not know that I was on her trail. Neen. I am good at that work. She slipped through little paths that were not paths at all. Twice I lost her, but I picked her up again. I was excited, much excited. Those words about sleep had stirred me. I would not have lost ner for a million gulden. Curiosity made my throat dry.

"I must have followed her six miles, perhaps more. We came to a clearing in the jungle, and in the middle of that clearing was a hut fenced around with split bamboos. She slipped through the fence and into the hut.

"I crept up to the bamboos and waited. There was something that was not nice about that hut, not nice at all. It was very silent in that patch in the jungle. It had the weird expectancy that dries up your mouth and makes your throat like a lime-kiln. It cannot be explained. It is the reaction of nature against matters that are not normal. Ja, that is it. The hut or the persons in the hut were a little over the edge. They were queer, and the jungle that watched them knew that they were queer.

"I kept my eye to a hole in that bamboo fence. The words the woman had whispered to the stone god were running round in my brain like little red beetles. Those words, 'Holy One, you do not sleep!' were startling.

"An hour went by—two hours. The silence was choking. Not a sound came from the hut. It was then about two o'clock in the afternoon. For the first time in many years I was scared—scared of nothing! I was scared because it was too quiet in that little clearing—too damned quiet.

"It was nearly three o'clock when that place woke up—suddenly. The woman came out of the hut at a trot, carrying a dishful of red coals. She placed the coals in a circle on a piece of ground that had been beaten flat—in a circle that was about six feet in diameter. She was in a great hurry. She was acting as if they had suddenly got news of great importance.

"Then I saw the man. He was her husband. He came out of the hut on all Jours; he was crippled so that he could not stand upright, and as he crawled, he pulled benind him a blue-nosed ape. An ape with a little tinkling bell on his neck!

"That ape was not in a hurry. Not much! When he saw the smoke rising from the hot coals, he hung back, and the man cursed him. Cursed him a lot. They were in a great hurry to do something. The woman kicked the ape to make him move, and I did not blink my eyes as I watched. I knew that I was going to see some business that was out of the ordinary. My skin told me that—my skin and the watching, listening jungle. Bad stuff was in the making, in that place.

"When they got the ape close to the circle of coals, they lifted him up and tossed him into the ring. He was pretty mad, was that ape. He spat some ape curses at that pair as he sat in the circle with the saliva running from his mouth. He did not like that business.

"The crippled man tossed something on the hot coals. A blue smoke went up, like the incense smoke that the pawangs use. It was so thick that I could not see the ape. The man lowered his head so that his forehead touched the ground, and he commenced to chant in a dialect that I did not know. The woman covered her eyes with a corner of her sarong.

"After about five minutes the smoke cleared away, and I looked at the circle within the coals.... Now, you must have that belief I spoke of, the belief that is necessary in the East. That circle was empty! The ape had disappeared!"

KROMHOUT paused and leaned forward, listening to the chorus of imprisoned things. A new note had come into the protests of the captives, a note that suggested fear on the part of the monkeys.

Kromhout, holding the sleeping hanuman in his arms, entered the bungalow, swung a torch over the cages, listened to the chattering for a few minutes, then returned to his chair.

"They think they smell something," he said. "Something that is prowling around. A panther, perhaps. They know so much, and they are sure that I know very little. And they may be right....

"I told you that the ape had gone. Ja. I tried to figure out how he had gone, but I could not. The loop of green-hide that had been around his neck was in the circle, but he was not there. I wet my Hps and waited. The silence hurt my head. The man had his face on the ground; the woman stood like a statue, her eyes covered.

"An hour went by; then the man made a quick clucking noise to the woman. She dashed into the hut and brought fresh coals. They were in a hurry now, the way they were before. She spread the coals in a circle, and the man sprinkled the powder on them. Up went the smoke, and the man chanted.

"I was watching close then, watching the smoke drift away. I expected something. Ja, ja. I expected that ape to come back, and I was right in thinking that he would. When the smoke cleared away, he was there in the center of the ring—lying down in the center of the ring.

"He was a mighty tired-looking ape. He was wet with sweat, and he was gasping for breath. He looked as if he had run all the way to Batavia and back during the hour that he was absent. He was all in, was that ape.

"The man and the woman lifted him out of the circle and carried him into the hut. They shut the door, and I knew that the business was over. I squatted at the fence for a while; then I felt that I should hurry back to the bungalow. Do you know why? Those words that the woman had whispered to the stone god were pricking me. Those funny words: 'But you do not steep! O Holy One, you do not sleep!'

"Those words were whips that flogged my legs as I ran back along that jungle path. Whips that hurt me! I knew that I had been a fool. I cursed my stupid Dutch brain as I ran through the trees, the creepers clawing at my face and hands. I had heard, and I had not understood. 'O Holy One, you do not sleep!' And I knew that the natives thought Kenyon was that stone god who had come to life. The French call us Dutchmen, tÍtes-de-fromage. Just then I thought the French were right in giving us that name. Ja, I did.

"I came in sight of my bungalow, and I ran faster. What had that ape been doing while he was away? I was sweating with fear.

"Kenyon was sitting on the veranda of the bungalow. As I ran. I saw that he was asleep. Asleep! His chin was on his chest, and his revolver had dropped from his hand to the ground.

"'Kenyon!'I cried. 'Kenyon! Wake up!'

"I shook him by the shoulder. That was the first doze that he had had for six days, and it was a hard business to rouse him. He came out of his sleep as a man would come back after being knocked unconscious.

"He opened his eyes and looked at me —looked at me as if he did not know me; then with a little yelp of terror, he flung his right hand around to his left shoulder-blade. His face was not nice to see at that moment, not nice to see at all.

"I knew before he spoke, before he unloosed the curses that he flung at himself for being so foolish as to go to sleep.

"'He got me again, Kromhout!' he cried. 'The swine has bitten me again!'"

THE mother monkey whimpered in her sleep as memories of her little one came into her dreams. The big hands of the naturalist stroked her gently. The ceaseless thresh of the lizards and snakes suggested emery paper applied to a rough surface.

"That afternoon I was in charge of a madman," continued Kromhout. "I had to do something. Toward dusk I gave Kenyon a sleeping-draft. Neen, he did not know. I slipped it into a peg of whisky. It was strong enough to make him sleep twelve hours.

"When he had dropped on his cot, I pulled down his shirt so that the bites showed. I made a paste of strychnine crystals. Because strychnine is bitter, I put in some sugar—a lot of sugar. Then I put that paste on Kenyon's shoulder, in line with the other bites. That is what I did. And I said a little prayer for myself, asking the Almighty to forgive me for what I was doing. After that I went to bed....

"Ja, he was bitten. I looked at him before daylight while he was still asleep. And before the effects of that sleeping-draft had worn off, I washed his shoulder and put some iodide of potassium on the new bite. Then I waited, wondering what I would hear.

"About eight o'clock I heard the news. A native running by my bungalow called out to me: The crippled fellow in the hut who played tricks with the blue-nosed ape was dead. He had eaten something, so they thought; and he had died in great pain. The blue-nosed ape was dead too. The native thought the ape had died of grief.

"Kenyon woke up an hour later. He was mad when he found he had been bitten again, but I quieted him. 'It is the last time,' I said. 'Nothing will touch you again.'

"'Why do you say that?' he snapped.

"'Just because I know,' I answered.

"And I was right. He stayed around there for five months, but he was not troubled again. Not once!

"The wife of that cripple married again—married a big strong man. She had lots of babies; and when I saw her with them, I did not worry so much about that strychnine paste that I had put on Kenyon's shoulder. I thought I had done something that the Almighty approved of. I had that feeling in my heart...."

Kromhout gathered up the sleeping hanuman and rose from his chair. At the door of the bungalow he paused and looked at the thick darkness. "That is a small matter when compared to the things that have happened here," he said quietly. "The Malay is bad. Always when I think of it, I remember the Drosera that eats the little flies. We who live here are the little flies too. Now I go to bed."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.