RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

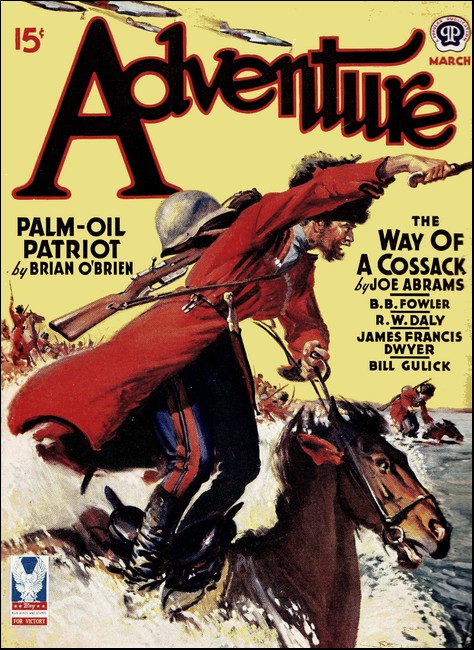

Adventure, March 1943, with "The Dutchman, The Dyak And The Jap"

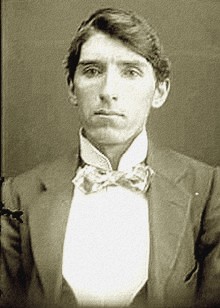

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

"THIS will not be a nice war," said Jan Kromhout, the big Dutch naturalist, after listening to the radio report of the attack on Pearl Harbor. "I mean it will not be pretty. Neen! Those Japs are bad. I could tell you some things about them that you might find it hard to believe."

Kromhout filled his meerschaum and lay back in his chair on the veranda of the Hôtel des Indes. The Dutchman had a curious habit. He would make a remark that suggested a story and then wait to see if the curiosity of the listener was stirred. If the person addressed had a desire to hear the tale he had to express that desire by complete silence. If he spoke of other matters the story never came.

Five minutes passed, ten. The city of Batavia was silent. The only sound that came to us was the slur of bare feet on the Molenvliet. Kromhout took a pull at a glass of schnapps that rested in the arm-support of the big teakwood chair, wiped his lips and accepted my unuttered invitation.

"I WAS trapping on the Samarahan River in Borneo in the

spring of 1938," he began. "It is a lost country. Seven

miles from my camp was the bungalow of a Jap named Matsui.

He called himself an anthropologist. He was from the

University of Tokyo and he thought he knew a lot.

"He was a queer fellow. He was small, very small, but his hands were strong and hairy. They were much like the hands of the mias, the big orangutan of Borneo. And his ears were funny. There is a lot of knowledge to be got from a man's ears. Our ears tell most everything about us.

"Do you feel cold when you come suddenly on a snake? Ja? Well, every time I met that Jap I was cold like that. It was strange. If I met him on a jungle path on the hottest day I would be suddenly cold.

"I asked myself why but I could not get an answer. Yet I knew there was an answer. There was something about that Jap that made me pretty sure my ancestors had a grudge against him in the years gone by. A very big grudge. It is the wisdom of our ancestors that breeds love or hate. They look through our eyes and see the fellows that we meet and they whisper Ja or Neen as the case may be.

"My mind could not find the reason why that Jap made me feel cold. It was a reason that was too far back in the memory list. I mean the list that had been handed down to me by my father and grandfather and great-grandfather and which they had collected for years. I had played tricks with that list. I had piled on it all the fool stuff that we call civilization. The stuff that smothers our fine animal instincts. Art and history and politics and literature. Ja, those things that are worthless.

"I was very good at history when I was a boy. I won prizes because I knew by heart the lives of the Dukes of Guelder and the Counts of Holland and all the stories of Tromp and De Ruyter. I did not know when I was learning that stuff that I was injuring my brain by covering over the fine animal traits that had come down to me through the centuries. I did not.

"In the hot nights on the Samarahan when the only noise was the roar of a mugger in the river I would catch a glimpse of that answer as it flashed for an instant through the heap of nonsense I had laid upon it. Just for an instant it seemed plain, then it fled before I could clutch it. And I thought it laughed at me. Ja, I did. Do you know why? Because it was the Old Wisdom that I had thrown aside for the New.

"This Jap, Matsui, spoke very little. He told me that he had come to Borneo to study animals, not to trap them. My business and his were altogether different. I was trapping the mias, the big orang-utan, which he was studying. He did not like me for that.

"I had three Dyak hunters helping me. Those Dyaks did not like the Jap. They would chatter like parrakeets when he came near. They were afraid. Do you know why? Because, although he was as much of an animal as the Dyaks, he had gathered up all the tricks of this thing we call Civilization without losing his animal knowledge. Do you understand? He was the Dyaks and me combined. He was the Past and the Present.

"To the Dyaks I was just a silly Dutchman collecting animals to send to Amsterdam for fools to stare at in zoological gardens on Sundays and holidays. That was a business that was brought about by civilization and I was a civilized person. But this Jap, Matsui, knew all that I knew and with that he had the cunning and deviltry of a black panther. That is why I say that this will not be a nice war.

"That Jap had come out of the husk of barbarism so lately that he remembered everything that he had left behind. He was the thing called a civilized savage, and there is great danger in those civilized savages. This civilization is a medicine that must be taken drop by drop. The Japanese have swallowed the bottle.

"ONE evening the youngest of my Dyak hunters came to my

hut and squatted outside the door. I was busy and I did not

take any notice of him. He sat without moving till a big

yellow moon came up out of the jungle, then he made noises

in his throat that made me look at him. I asked him what he

wanted and he made signs that I should go with him into the

jungle.

"I was tired and I asked the reason. He would say nothing. A Dyak can be very stubborn and sometimes he cannot express himself. He stood looking at me, and from his nearly naked body there came fear. A great fear. Not of me, neen, but fear of something that he wished to show me in the jungle.

"This young Dyak had once worked for Matsui. He had run away from the Jap because Matsui had got mad with him and had burned his back with a hot poker while the Dyak was asleep. You will hear of things like that as this war goes on.

"I picked up my rifle and motioned to the hunter to go ahead of me and he trotted off like a pleased child. He thought that I, being civilized, could solve the thing that was puzzling him. It is funny how we believe in those fool tricks that civilization brings to us. And our arrogance makes the savages believe that we are wiser.

"We followed a track that led into the heart of the jungle. The tree masses blocked out the light of the moon, but that Dyak could walk through the darkest night without stumbling. There are eyes in our toes, bit we cover our toes with shoes—so that our feet are blind.

"We came to a clearing in that great stretch of trees. The Dyak dropped on his hunkers and motioned me to sit near him. The clearing was not more than forty feet across, and now that the moon had climbed a little its beams struck into the center of it. There was no grass because the trees kept out the sunlight. There is seldom any grass in a thick jungle. We were sitting on a bed of rotting leaves that might have been ten feet deep.

"I was trying to guess why the Dyak had brought me to this place but I could not think of a good reason. Twice I pushed him with my hand because I was a little tired of crouching there on the damp mold, but each time he made a sign that I should keep quiet. And that fear I spoke of was still on him. It came out from him and made me forget the cramp in my legs.

"We were there for an hour or more when I heard the sound of something big coming through the tree-tops. I knew before I saw the animal that it was a mias crashing along in a hurry, then the moon gave me a glimpse. It was a big female mias and I knew her! She had been wounded by a Dyak spear when she was young and she dragged her left hind leg. She was a very cunning animal. She had sprung my traps and made me mad.

"The Dyak thought that I might shoot her so he grabbed my hand and held it while he hissed words into my ear. I knew then that I had been brought to that clearing to see something pretty wonderful. I knew that. The fear that came out from the native struck into me. Into my blood and bones. It was a force that spoke to me, telling me to keep quiet and watch. All the power of my senses was in my eyes.

"The mias heaved herself from limb to limb till she was quite close to the clearing. At times we could not see her on account of the creeper masses, but, suddenly, she broke through the branches directly opposite to the spot where we were sitting. Broke through and peered at the clearing. The Dyak was leaning forward, his naked body tense. He was sifting the whispers of the night.

The great bulging night that roamed around us. And the way in which he listened made me believe that something fearful was going to happen with the coming of the mias. Something that would not be nice to God or man. I think that the night tore some of that silly stuff about the Dukes of Guelder from my mind to let me see scraps of the Old Wisdom. Things that I had never learned at school were streaming out of the back of my head where they had been stored in the subconscious.

"Then, silently, slipping forward like a phantom, a man appeared on the clearing! A man naked except for the chawat around his loins. You have guessed? Ja, it was the Jap, Matsui!

"HE had come noiselessly up a side trail and had

sprung out of the bushes onto the cleared space. He had

no weapons. Neen! There was but the loin-cloth on his

muscular body. And he stripped well did that Jap. When he

moved into the moonbeams I was surprised. He looked tough.

Small but tough.

"Now I did not see that Jap glance at the spot where the mias was crouching in the tree, but he must have known that she was there. Yes. he must have.

"You wonder what that Jap did? I will tell you. He walked to the center of that open spot in the middle of the jungle and he commenced to dance. He commenced to dance.

"You will ask me what kind of a dance? I wish I could describe it as I saw it. It had no exact measure, no rhythm, but there was in it the very essence of primitive life. It was the base of all dances. It was the first swagger of the male that had ever come into the world!

"We say that a thing is barbaric. We say that something is not nice. We are throwing bricks at our forefathers when we say that. The barbaric things are what our ancestors did. We think we are clever because we have taken the punch out of many things and made them what we think is nice. We are foolish to think so. The animals and the birds have not made their business 'nice.' The cock pheasant struts in the manner that has come down to him through a thousand years and so do all the other living things, all except man. Man has made his dances clean! It makes me laugh.

"Sometimes that Jap would just walk. But it wasn't a walk. Do you understand what I mean? He would move softly and slowly across the clearing in what you might call a walk but in that jungle in the moonlight that walk had meanings. A million meanings.

"Once, years and years ago, I went home to Amsterdam on a visit. There was a Russian dancer at the theater. His name was Nijinsky. I had heard much of him. so I bought tickets for my sister and her husband and myself.

"It was a piece called L'Après-Midi d'un Faune. This Nijinsky, who took the part of a faun, sees some nymnhs and he came close to look at them. The nymnhs saw him and ran away, but one of them who was curious came back. Nijinsky danced with her, but she became afraid, and bolted, leaving her scarf behind.

"Nijinsky danced with that scarf. He made big business with it, fondling and pressing it to him as he danced. The audience sat and stared at him because he had switched them back into the past. When he finished they were gasping because his dance told them a little of what they had been once.

"That dance turned my sister sick. Her husband who was a cheese merchant was sick also. He was a fool. He called the dance barbaric.

"Well, I was a little sick watching that Jap dance. It was tougher than Niiinsky's. It was a little unclean. Why? Because that brown man was dancing for an animal! He had not looked up at that mias but I knew that he was dancing for her. For her and no one else.

"I dragged my eyes from the Jap and looked up at the orang-utan. She was watching the dancer with the same intentness as the Dyak and myself. Her round eyes glittered in the moonlight. And when she moved, to get a better view of him, her movements were stiff and unnatural because her mias brain was occupied solely in watching that fellow prance around the clearing. Her short neck was thrust out and she struck savagely at swaying branches that got in the way of her view.

"I had a desire to pray and that was unusual for me. Just a little prayer asking the Almighty to blast the pair of them from the earth. Ja, but in the back of my head was a hope that He would not do so till I had seen everything that was to be seen.

"THERE was a great silence as that Jap danced. There

were no animal noises and that was curious. Very curious.

No howls from the wah-wahs and no yelps from the lemurs

and the other monkeys. I have wondered much about that

silence. Did the things of the jungle know what was going

to happen? Did they think the business of that prancing Jap

was not right from their point of view? I would like to

know.

"Always when there is a great silence in the jungle I think that something has happened or is going to happen. If a snake kills a bird every feathered thing for a mile around knows it and is silent till the fear wears off. They sense the tragedy, they smell it, they feel it with every feather of their bodies.

"For fifteen minutes or more that dance went on. I have seen all kinds of native dances in the Orient but I have never seen one like that which Matsui danced. Never. Have you ever heard a tune that you could translate into words? Well, that dance was translatable into words. Words that ran through my head and which I thought I understood, but I didn't. They were dead words. They had been buried too long under the fool stuff that I had sucked in through my ears and eyes and piled on top of them. They were the words of the Old Wisdom.

"I had drowned them with the history of the Netherlands and other places. With lying literature and the study of the silly pictures in the Rijksmuseum. Gott im Himmel! What fools we are! I spent hours as a boy staring at those stupid pictures! My mother thought that I would be an artist. Me!

"Matsui stopped dancing and stood in the center of the clearing. Now his eyes were on the mias. She came slowly down the tree, moving stiff-armed and stiff-legged, till she reached the lowest limb. I could see her quite plainly. She looked startled, puzzled, much distressed. The orang-utan shows emotions in a very human way.

"She sat and looked at Matsui. I had never seen a mias come so close to a man. Never, and I have trapped animals for more than thirty years. In captivity the orang will make friends with his keeper because the keeper brings him his food and he knows he will starve if he does not get it, but in his wild state he can live off the durians and the mangosteens and thumb his nose to mankind. Yet here was a female mias squatting within three yards of that Jap and staring at him as if she was hypnotized!

"It was the mias who first commenced to chatter. She made funny little throaty noises, leaning toward Matsui as she made them. And that Jap chattered back to her. Not in his own tongue or in any other that I knew. It was not the speech of the Klings or the Dyaks or any of the Malay dialects. It was a queer hissing speech that was disturbing. Just as disturbing as the dance. For it was old, so very old. It awakened memories that were not nice. Not nice at all.

"The mias dropped from the limb to the ground. She was crouching near the butt of the tree. Matsui commenced to dance again. Now he moved toward her, then he retreated, his hands weaving out toward her as if challenging her to join with him in his prancing.

"Faster and faster he moved. I do not think I will ever see a dance like that Jap danced. It had something that I cannot describe. It lifted me out of myself. It sent me back through the centuries. I was not Jan Kromhout. I was something without a name. Something like the mias. I was so mad with that man that I reached for my rifle but the Dyak grabbed my hand and held it tight. That Dyak wished to see the end of that business.

"Matsui stopped with a suddenness that took my breath. It was like the wild jerk of a horse thrown on his haunches. And with the silence and the veiled moon his trick was a little frightening. He was a statue. A statue of something not nice. Not what you would want to look at for a long time.

"That mias was his victim then. She was hypnotized. She made funny noises to show him that she was conquered. She crept toward him. She put out a hairy paw. Matsui took it. They disappeared down the path up which the Jap had come!

"It was minutes before I recovered myself. At last I stumbled to my feet. I looked at the Dyak. His mouth was open, his eyes wide with fear.

"We went back through the jungle without speaking. And the silence was greater than ever. No bird or animal made a noise. They had seen something or sensed something in the night that terrified them.

"IT was daylight when that young Dyak beat on the door

of my bungalow. He was excited. He wished me to come quick

and see what he had seen. I could not make sense from his

shouts.

"I pulled on my clothes and went out to him. He started to run, screaming out to me to follow him. I was angry, but I knew that something was wrong, so I followed.

"He ran through a stretch of swampy ground where the leeches were so thick that they clung to you in hundreds as you passed. I cursed that Dyak. I called out to him to stop but he would not stop.

"He was heading up-river in the direction of the Jap's bungalow.

"We crossed a swinging bridge of rattan and ran along a trail, the Dyak leading me by twenty yards. In the darkest part of that trail we found the Jap, Matsui.

"He was dead and he had been killed in a way that did not make him look pretty. The killer must have been angry with him. Very angry.

"'Who did it?' I asked the Dyak.

"'The husband of the mias,' he whispered. 'He was watching her last night from one of the trees. That is why the jungle was silent. All the birds and animals knew there would be a killing.'"

JAN KROMHOUT refilled his meerschaum, lit it, then

spoke softly. "I said that this civilization is a medicine

that should be taken in drops," he said. "The vanity of

the Jap has made him try to swallow a thousand-year dose

in half a century. It has upset him. He does crazy things

...Ja, this will not be a nice war. I mean it will not be pretty."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.