RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

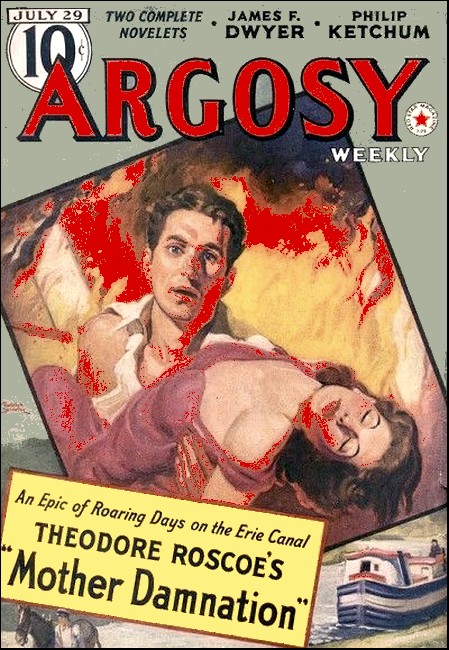

Argosy, 29 July 1939, with "When The Dyaks Dance"

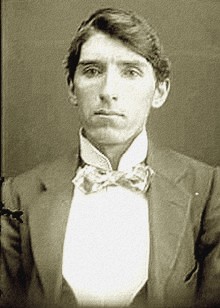

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

Again and again the native women circled

the hut, lifting their great song.

In that Borneo jungle reigned the silence of death; and then slowly the lullaby lifted—the song of the world—and its magic gave one man new life.

JAN KROMHOUT, the big Dutch naturalist, told me this story one evening in Bandjermasin. A cyclone was in the making near the Karimata Strait. The atmosphere resembled aerified india-rubber with a seasoning of sulphur. The beer spurted like an oil well when uncapped; my ears heard in fancy the tinkle of ice cubes on faraway Broadway.

Kromhout had found an old copy of the Strait Times, the front page of which carried a thrilling story and a photograph. The story concerned a fire on the small steamer, Krung Kao, plying between Bangkok and Saigon. The blaze was discovered after the vessel passed Poulo Condore Island in heading for the mouth of the Saigon River. The captain, a Malay half-breed, lost his head, launched a boat, jumped into it with four of the crew and pulled away from the steamer. The rest of the crew started to follow his example.

There were seven passengers on the steamer. Three women missionaries, two French sisters of charily, and an American named John Creston who was accompanied by his wife. This man Creston was asleep when the fire was discovered, and when he got on deck the captain had decamped and the crew were hurriedly lowering the remaining boats. It looked as if the seven passenger would be left as baked offerings to the gods of the China Sea.

Creston was annoyed. He had no firearms, but he got hold of a fire-slice dropped by one of the stokers who had rushed up on deck, and with this fire-slice he did wonders. He beat the crazed Chinese sailors back from the boats and forced them to attack the blaze. They conquered it at last, then Creston assumed command of the crippled Krung Kao, headed for the coast and beached her at the mouth of the Mekong. The photograph showed a tall, well-built man in the thirties with a sweet-faced woman at his side.

"I am not surprised," said Jan Kromhout. "I knew Creston. One season I trapped with him at the headwaters of the Kapuas River. He came from Baltimore, and he was the finest looking man I have ever met. Ja, he was so.

"Always he reminded me of a picture by Dirck Hals in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. It is the picture of a swordsman who has the grace of a black panther. When I was a little boy I would go and stare at the picture, hoping and praying that I would grow up like the original. You can see that I did not. I did not pray enough to control the lines of my stomach.

"But this American, John Creston, was that swordsman of Dirck Hals and some more.

"Those fellows that make the cinema pictures in America would have been glad to get him. You bet they would. But he kept out of their way. He liked the jungle and the things of the jungle. He knew every wild thing in the Malay. Every monkey from the big mias down to the little lemurs and he had ways with them that puzzled me.

"He had been to lots of out-of-the-way places, but it was funny that when speaking of his travels he never mentioned a woman. Never. One day I talked to him about this. I said: 'It is funny that you do not mention girls. Don't you like girls?'

"He flushed when I put that question. 'Why, yes,' he said. 'Of course I like girls.'

"'Then why don't you speak of them?'

"He did not answer me. If you saw him you would think that he was the sort of fellow that would have had lots of affairs with women. He looked a man that women would bother.

"There was a young Dutchman who lived on the Stadhouderskade when I was a boy. He was not half as good-looking as Creston but he was always in trouble with women. One night a burgomaster who was on his way to the Hague found that he had forgotten some papers and he went back to get them. That young Dutchman heard him coming up the stairs and he stepped through the window, thinking there was a balcony outside. There was no balcony. He had mixed up the house with another house he visited on Kalver Straat. He fell three stories and was killed.

"All the women were sorry but the old men were pleased. When they buried him they put an iron cross on his grave, and folk said that the ends of that cross caught the petticoats of any woman who came near it."

BUT I am speaking of this man Creston (Jan Kromhout

continued). One day I said to him: "If one of these snakes

gives you an extra hot shot of poison who will I write

to?"

"No one," he snapped. "I had only one friend in the world and now she is not here."

That was his secret. He was living down the memory of a mother. For some men it is a difficult business. Ja, a very difficult business. Those memories of their mothers are like thick glass in the windows of their souls. They stop them from seeing other women. It is sad. This Creston had a photograph of his mother that stood on a box alongside his bed, and he would not let the Dyak boy touch that painting. He would not let anyone touch it. Once I moved it a little because I wished to sit down on that box and I thought he would hit me.

One night that Kapuas River started to make trouble. It washed away some huts of the Dyaks, and in one of those huts were two women. One was an old woman, and the other was a woman who was going to have a baby. It was dark. You could not see the women, you could only hear them yelling in the middle of the stream.

I tried to stop Creston, but he pushed me aside. This paper says that he does not know fear. That is one of the truest statements that I have seen in a paper for a long time. He was frightened of nothing. I would not jump into that river for a million dollars because the flood had brought down all kinds of snakes and spiders and scorpions from the hills, but Creston jumped in.

The pawang had told him that one of those women screaming in the darkness of the flood was going to have a baby and nothing could stop him.

He brought those two women to the bank, and he brought with them a fine attack of fever. Ja, ja. A bad attack. Fever is funny. Sometimes it hits a little weak man and leaves him in a day or two so that you would think it had taken pity on his weakness, then again it will jump on a big strong man and fight him to death's door. It did that with Creston.

It jumped on him like those fellows that wrestle in what you call "all-in," and it gave him all the kicks and blows that it carried. He was a very sick man. He was in great pain and he could not sleep. Not a wink.

The natives were interested in Creston's illness. They loved him. They would bring all sorts of things to the hut. herbs and roots and potions that they thought would make him sleep, and the old pawang brought a packet of secret powder that he said would bring a dead man to life. He wished to give it to Creston but I would not let him. It was hard to stop those natives.

I had to watch Creston day and night to stop those fellows from slipping something into his drink. Those powders might have done him good. Many times when the quinine gave out I thought I should try them, but I didn't. We Dutch are square-headed folk and we do not believe in charms. When Creston's temperature was the highest I would say to myself Na hooge vloeden diepe ebben—After high floods low ebbs.

But that fever didn't believe there would be any ebb. It had Creston by the throat and it wouldn't let go. It was one devil of a fever. I was scared. The November rains were coming, and if Creston didn't shake it off before the wet season set in he would never come down to the coast. He was skin and bone. He could not eat and he lay without speaking. It looked as if he had given up the fight and was anxious to pass on. The boy who was attending to me saw signs. Ja, he saw plenty signs. Three vultures flew in if circle over Creston's hut, the wahwahs were howling in a way that they never howled unless death was close.

The old pawang, who liked Creston, came and spoke to me. Very inquisitive was that old man. He wanted to know if Creston had any women that loved him. I said he had not, and that puzzled the pawang. The men of that tribe found women to look after them when they were very young. They were clever fellows. It was very nice to own a strong wench who would make fires and trap game and cook and take a crack on the head when her lord and master was in a temper.

The pawang went and told the tribe that Creston hadn't a woman friend in the world. Those natives were startled quite a bit. They held a pow-wow amongst themselves, and they decided they would do something to help that American who was so very ill. They came and explained it to me. They would have a special ceremony that would put Creston under the protection of the Great Mother of the gods and men.

THE Dyaks think that men are babies given into the care

of all women. A man is, to their minds, not the particular

worry of one woman. Neen. He is the worry of all the

women in the world. There is watching over him the maternal

eye that the Romans called the Bona Dea, the Great

Mother. She was Cybele, Maia, Mater Phrygia, Rhea, Ceres,

and other names. She was the goddess that had the qualities

of universal motherhood. It was a nice belief, was it

not?

("It was," I agreed. "A very pleasant belief. At this particular moment if she has any love for me she should materialize on this table a dozen iced lager. I've never asked her for much."

Jan Kromhout ignored my flippant remark. He was busy with his tale. The Dutchman was a storyteller on whose slow sentences rode God-given Belief. He bristled with anger if Doubt showed on the face of a listener.)

People say now that the world is small. It has always been a small world. In the days when Maia was worshiped on the Aventino on the first day of May, and when Damia was worshiped at Tarentum, and Ammas in Galatia—the three being the same goddess under different names—news of those happenings were carried by caravans to places that were quite some distance away. It was carried to Persia, to India, and up over the Road of Silk to China, and from China it dripped down into the Malay. The human tongue is the best medium for spreading news. It was then, and it is today.

Those caravan men told of the Great Mother of the gods and men. A goddess as beautiful as the dawn who mothered all the foolish men of the world. It was a nice belief. She was around when they were sick on caravan routes or on jungle trails. They had only to breathe her name and she would put a soft arm under their aching heads and whisper nice things in their ears. It was a belief that found easy converts.

Creston was shuffling along the last lap to eternity, so I did not think it would hurt to let those natives stage that show. I asked some question; and they told me what it was to be. Just as the women of ancient Rome conducted the ceremonies to the goddess those women of the tribe at the foot of the Kapuas Mountains conducted it. No men were allowed to take part in that business. Not much. It was a purely feminine matter.

Creston was lying in a small hut made out of split bamboo and thatched with nipa-palm. It was alongside the hut that I slept in. It had a small window opening that was about six inches square, and it had a strong door of plaited bamboo. No one could get into that hut through the little opening, and before that ceremony started I put a chain and a lock on the door. I did not want any of those women troubling that poor devil who was so near death.

The pawang asked me to go into my own hut and shut the door. He begged me not to look out of the little opening in my hut and I promised him I would not. I did not believe in that mumbo-jumbo, but those natives were crazy to do something for that American and it didn't seem right to stop them.

In Greece and Italy and Phrygia that business of worshiping the goddess was quite an affair. There were queer goings on. Ja. There was a fellow in Rome named Claudius who disguised himself as a woman and got into one of those shows and he also got into a lot of trouble when they found him out. You should read about that fellow.

But I had no curiosity about that business. Neen. I locked up Creston's hut then I went into my own, shut the door, and sat down to wait. It was getting dusk, so I lit a lamp and started to read Furbringers book on the Spina Occipital Nerven of reptiles. It is a good book and I wanted to keep my mind off that poor devil who was dying.

Up till that evening I had thought that silence was just the absence of sound. That it was nothing in itself. Just a sort of vacuum caused by the stopping of all noise-making activities. That is the general opinion; I think you would find that those foolish dictionaries would say the same. They are wrong. Silence is as much an active thing as sound. Ja.

I found it out that evening. It came and stood at my shoulder and told me to close that book about the nervous system of snakes. Close it and put it down gently, which I did. Then it told me to open my ears as wide as I could. There was not one little bit of noise in the whole of that jungle. There was not one bit in the whole of Borneo. It was a devil of a silence.

I thought Creston must have died. I stood up to go to him, then I sat back again in the chair. Those women in the dusk outside had begun that business of putting Creston under the protection of the Great Mother of the gods and men.

THOSE women sang the lullaby of the world. The lullaby

of all women of all time. Sang it into the hot silence. It

swept over me. It stunned me. It held me with clamps of

iron in that chair with only my ears working....

The Dyaks have a legend that tells about the first baby that was born in the jungle. It cried so much that it disturbed all the animals. The animals could not sleep and they could not sneak on tiptoes on other animals that they wanted to catch. They were very mad with that baby.

One day they got up a committee to call on the mother of the baby and speak hard to her about the child. There was on that committee a big female orang-utan that the natives call mias, there was a honey-bear, a big pig that is called the babirusa, there was a seladang and a small Bornean panther, a clouded tiger, the little mouse-deer, a boa-constrictor, and a lot of flying squirrels, porcupines, civet-cats, lizards, and frogs.

The big female mias did the talking. She asked the woman why the baby cried, and the Dyak mother said she could not keep the child quiet. She was sorry but she had done everything she could. When she finished speaking the big mias stepped forward and took the crying baby out of the woman's arms. The ape started to sing a lullaby, and in ten seconds the child was asleep.

It was that lullaby multiplied a million times that the women sang around the hut of that American. It was a protective chant. It was a song of strength to men. It brought memories of firesides, of warmth, of broad bosoms softer than the down on the wild goose, memories of sleep deeper than the Tuscarora Trough. It was the mother of all lullabies.

The big things of the world have foundations that are way back in the past. Thousands of years back. I mean the big things of life. Honor, and national pride, and love of country and of offspring, and cleanliness and truth. They started in people when the world was young.

So did that lullaby that the Dyak women sang to Creston who was at death's door. The basic notes of that lullaby were sung to the Neanderthal man in a rock cave in Germany when he was a baby. And I bet his mother thought he had a nice head while we think he had the retreating head of an ape. Ja, she crooned over him and thought him pretty. And the long-headed palaeolithic babies heard that soft chant that grew better and sweeter for the round-headed neolithic babies that followed them.

It spread out over the world. From the Black Forest to the Khasi Hills, from the Nile Valley to the Pocky Mountains. It was the song of life. It was more than the whispers of love: it had in it the joy notes of life, of procreation, of reproduction.

Those women wen marching around the hut of Creston as they sang. Marching round and round in the soft dusk. And their bare feet on the grass made a soft undernote. A primitive undernote. I thought of our wandering ancestors who had to be always moving; their women carrying their fat babies on their hips and singing to them as they swished down the dry slopes of the Caucasus to the sea. Lullabies and bare feet on the grass. It is in our blood. Ja, ja, ja.

We are a little mad just now in the matter of music. Sone crazy men who make jazz are fooling us. It will pass.

There are things that are in our souls that we cannot get away from, things like the lullaby of women. The berceuse of the French, the Wiegenlied of the Germans, the lullen of the Dutch, the lulla of the Swedes, the cradle-song of the Anglo-Saxon. You cannot turn those into foolish jazz. For that I am glad. Ja, I am glad.

IT finished at last, and when it finished I felt that

my soul had been washed in nice warm oil and dried with

the fleecy towels that my mother used when I was a little

boy. I do not see those towels now. I do not think they

are made. There is too much hate in the world to make

things that are nice and soft. We have grown as hard as the

cannons of hell that fill all our thoughts.

For a minute I was so happy that I forgot Creston. Then, when I was sure that the women had slipped away into the jungle, I ran to his hut. The lock and the chain were just as I left them. They had not been touched. I put the key into the lock, turned it, slipped off the chain and entered. There was no light in the hut; the little lamp had gone out while the women were singing. I took a step towards the table on which the lamp stood, then I stopped and my heart went up ten or fifteen beats.

Would you think I was crazy if I told you that something went by me to the door? Something. I do not know what. A wraith, a phantom, I couldn't tell. It was not flesh and blood although I felt its presence. And it had a perfume. A most delicious perfume. In that jungle there were heavy, wet scents that were bad for the brain, but this was a clean dry perfume that was good to breathe.

I struck a match and lit the lamp. Creston lay on his back, his eyes closed. I looked around the hut, and I saw that the leather frame that held the photograph of his mother had been folded shut, and it was now lying on the box instead of standing up as it had been.

Creston opened his eyes and looked at me inquiringly. His lips moved, and I stooped to listen. "What has happened?" he whispered.

"It was the women singing," I said.

"But—but who came into the hut?" he asked.

"No one," I answered. "I locked the door and kept the key in my pocket."

He was quiet for a minute, then he said: "Something—I do not know what—came in and talked to me."

"About what?" I asked.

"About life," he murmured.

"That is good," I said. "It is nice to talk about life. Life is good."

He glanced at the photograph on the box. He seemed puzzled because it was lying flat. He stared at it for a long time, but he asked no questions. I was puzzled too. I thought, and that was silly of me, that Creston had not closed that folder and laid it down on the box. I thought someone else had done it, but how the devil did anyone get into that hut when I had the key?

Both of us looked at that small window. A child could not climb through that opening. Creston spoke to me again. "Yes, I will get well now," he said. "I am very thankful to you, Kromhout, for nursing me."

"Of course you will get well," I said.

He dropped off to sleep then, and I knew that he had got a strangle-hold on that old fever. The singing of those women had got into his brain and strength was coming back to him.

IN the morning the old pawang came and asked about

Creston. He was cunning, that old man. He knew a lot. He

looked in at that sick American from the door of the hut

and he sniffed die air. I did not say anything about the

whiff of perfume or about that photograph being folded

up.

"He will get better now," said the pawang. "The gods have found for him a woman who will love him."

"Where is she?" I asked.

He waved his hand to the leagues of jungle that stretched between us and the coast. "She is somewhere," he said. "Somewhere out there. The gods looked for a woman who was free and they found one."

He left me some green limes and he waddled away across the clearing, turning every few yards to see if I was looking at him. Ja, he knew much that old man. Those limes had little figures made with women's fingernails on their skins. I did not give them to Creston. I buried them. I do not know why. The marks of the fingernails on their skins made them strange to me.

Creston got better with each clay that passed. Never have I seen a man climb back from the edge of the grave like that American. He absorbed strength through his nostrils each time he took a breath. In three weeks he was well enough to travel. He went down the Kapuas on the first high water. Just as we were climbing into the boat the old pawang handed me four green limes. I looked at the skins. They had the same marks of fingernails that I had seen before.

"Give them to him," said the pawang. "They will bring good luck. You forgot them. Those marks are prayers made by the nails of the women who sang."

I took the limes and gave them to Creston. I knew they were the same limes that I had buried three weeks before, but they did not look as if they had been buried. They were fresh-looking and clean. Creston sniffed them and looked pleased. A lime has a nice smell, and the natives think they bring good luck.

We came down to the coast, and Creston thought he would go across to the mainland and rest for a while. He thought to go to Penang, then go on to Taiping and up to Maxwell's Hill where there are bungalows four thousand feet high. He believed that a month or two on a mountain peak would set him up. I said goodbye to him at Pontianak. He was still carrying those four limes that had the markings of women's fingernails on their skins.

"Why?" I asked him.

"I don't know," he said. "They say that they bring good luck."

He laughed, we had a goodbye drink and he sailed away.

YOU do not write much out here. Letters between men are

a nuisance. The post office was started for lovers. A year

went by and I forgot Creston. I forgot those women that had

sung around his hut at the headwaters of the Kapuas. There

had been other things to trouble my brain. I had sent off

shipments of animals to New York and Amsterdam, and that

is a business that makes you forget all other businesses.

Ja, if you have to ship monkeys it will make you forget

lots of things. You will forget rheumatism, and gout,

and toothache. Monkeys are like that. If I was a doctor

I would recommend that monkey-shipping business for all

sicknesses.

I crossed to Singapore from Bandjermasin with a shipment for the big zoo in the Bronx at New York. Small monkeys and some snakes, On the second day in Singapore I was sitting in the bar of Raffles Hotel when someone slapped me bard on the back. It was John Creston.

He was excited. Much excited. "You old Squarehead!" he cried. "You are just the man I wanted to meet! I have work for you! Nice work!"

"I do not want work!" I said. "I am having a rest after shipping some monkeys to New York."

"This is different," he said. "I want you to ship me to Paradise. I am to be married next week and you, Kromhout, are to be best man at the wedding."

He bought some drinks and then he insisted on taking me up to the Hotel Van Wijk on Stamford Road where the lady was staying. All the way he talked about her. Talked excitedly. She was French, she was a divorcee, and he had met her in one of those mountain bungalows where there is not much lo do but fall in love. Her name was Adele, he said.

I did not like that woman. I did not like her one little bit. She was like a small fat bird and she was one of those women that giggle at everything that is said before they find out whether it is serious or funny.

Everything was funny to her. I was funny, so was John Creston. She called him "Jacky," and when she called him that I could see that he didn't like it much. He was not the Jacky type of man.

Naturally any woman of ordinary intelligence would have understood that soon enough—particularly about the man to whom she was engaged: but I am afraid that Adele was gifted with less than ordinary intelligence. She merely giggled, and understood nothing—John Creston least of all.

The more I saw of that woman in the days that followed the more I disliked her. She made me nervous, and I thought that Creston was nervous too. Ja, I am sure he was. That fellow that had the courage of a tiger was all jumpy and sweaty when that woman was around. She said things about men that annoyed me. She thought them fools. There are lots of women who think that quiet men of the Creston type are fools.

Creston gave a dinner two nights before the day of the wedding. There were a lot of people. Some friends of this Adele woman. There was one fellow that knew her before she divorced her husband. He was a big man, a rubber planter from Kelantan. He spoke to Adele like an old friend, and each time he lifted his glass be looked at her and grinned. Creston was pretty silent, but he saw a lot.

That rubber planter got noisy when he had drunk about twenty whiskies. He said things that were not nice. Creston kept his temper for a long while, but at last he took that big brute by the arm and started him for the door.

It was what you or I would have done in the same situation; all that can be done, in fact, when a party is being ruined by a noisy drunk. This planter was just such a tiresome man.

Creston was polite with him, but the fellow got mad. He lashed out with his fist, and Creston had no time to dodge. It was quite a wallop. It knocked Creston backward, but he recovered quickly. He jumped on that big fool and put a ju-jitsu grip on him that made him howl. Straight for the door they went, the fellow howling like a wahwaw.

That howl brought Adele to her feet. She made a rush across the floor and screamed at Creston. She told him that he was a brute to hurt her friend. She was a fury. I have never seen a woman as angry as she was then.

Creston was so astonished that he let go of that rubber planter. They were at the door of the dining room. There was a porcelain vase on a stand. That drunken brute grabbed it and brought it down on Creston's head. He dropped as if he was shot and the planter ran.

NOW I am going to tell you something. Something big.

I got Creston into the cloakroom. I was helped by other

people. I do not know who they were. Some were the people

who were at Creston's dinner, some were folk who were in

the hotel. There was one woman who seemed to know what she

was doing. She looked at Creston's head and she asked for

water and she bathed it. She was one of those cool women

who do things.

"Does he live in the hotel?" she said.

"Ja," I answered.

"You should get him to his room," she said. "I will help you. He can walk."

Now I think that I sniffed that perfume before we reached Creston's room. I think so. But Creston did not. That whack on the head might have put his nose out of order.

In his room he sat on a big chair and he looked at that woman. Then he forgot the wallop on his head; he forgot that rubber planter; he forgot Adele. On the mantel above his head was that picture of his mother, and when the woman caught sight of it she jumped back and clutched at her breast with her hands.

"What is it?" asked Creston, and his voice was tense.

"I—I—" stammered the woman. "I—I met her in a dream! Not her, that picture of her!"

There was mystery in that room. Fine, fat mystery. You bet. It dried my throat. I could not say one word. And there was a great silence as if the world had suddenly died. All the little sounds from outside were throttled.

It was a strange story that was whispered to Creston and me by that lady. She was an American, and she had been keeping house for her brother at Kuala Lumpur. Just one year before she had an illness, and during that illness she had a dream. A strange dream. She thought that she had entered a bamboo hut in a jungle and had knocked over a photograph. A photograph of a woman who was the image of the woman whose picture was on the mantel.

That was all. The dream clung to her. She could not forget it. And while she was whispering that story the room was filled with that dry clean perfume that I had sniffed in Creston's hut at the headwaters of the Kapuas.

JAN KROMHOUT paused. He reached for the copy of the

Strait Times and studied the photograph. "She has not

grown one day older since the morning when I was best man

at her wedding," he said slowly. "She is a nice lady. One

of those motherly women who know all men are babies who are

given into the care of the women of the world."

"But—but what do you think?" I stammered, after the big Dutchman had finished speaking.

Kromhout laid the paper aside and frowned. He looked at me gravely for a moment, appearing to give his answer the utmost consideration, before he spoke.

"What I think is that this damn beer will boil if we don't drink it," he said quietly. "When I finish this bottle I am going to bed."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.