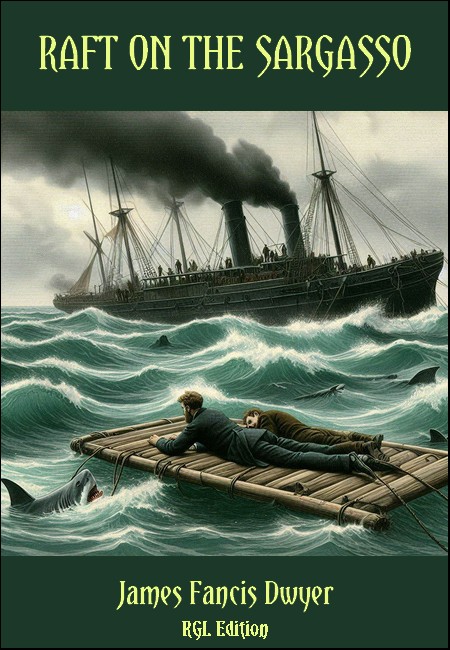

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

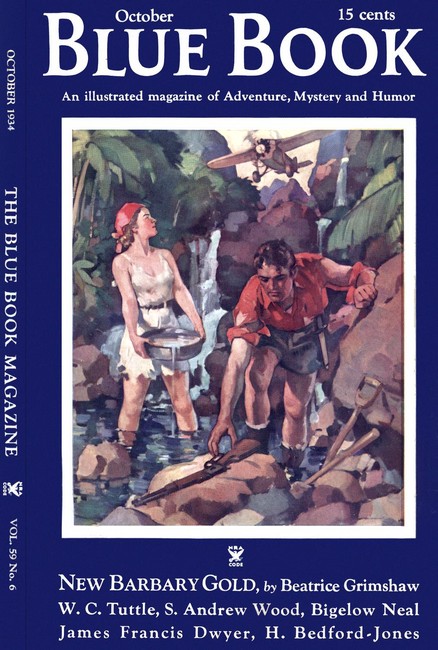

Blue Book, October 1934, with "Raft on the Sargasso"

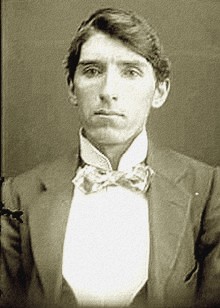

James Francis Dwyer

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

A vivid story of sea and shore by the noted

author of "Jungle House" and "The Splendid Thieves."

NOW with ghastly suddenness, the Law and the prey of the Law were placed on an equal footing. The vast hiatus that separated the detective from his prisoner had been closed swiftly by the conduct of the oil-tanker. The old petrol-carrier decided to quit, and the nearest land—five hundred miles away—was the Virgin Islands. The name, to the two men, stressed the remoteness of the haven.

Clinging, one at each end of the pontoon raft, the thick night made them invisible to each other. The detective, by the occasional clink of the loose steel cuff when it struck the zinc floats, sensed the position of his prisoner. The prisoner had the same directional knowledge through a malady of his guard. The Law was slightly asthmatic, and made whistling noises under the influence of fear and the night air.

The detective, one John Manolescu, had shown a certain amount of bravery. Or it may have been the dreadful professional adhesiveness born of his métier.

Anyhow, when the captain had shouted: "Over the side!" the detective had fought his way below-deck to get his prisoner.

The lock on the cabin door and his own nervousness had delayed him. When he and his prisoner stumbled out upon the nearly perpendicular deck the boats carrying captain and crew had dived into the night.

A pontoon raft, torn from its lashings forward, had rushed by them as the Coomassie dived. Manolescu and his prisoner had sprung for it. They were sucked down; the raft, longing for sea freedom, fighting the suicidal tendencies of the mother ship that had held it for years to her bosom. They were spewed up again, and rode a wild maelstrom for what seemed hours. Then quiet fell upon them. A tremendous quiet! The only sounds were the slopping of the inquisitive waves through the slats of the raft and the air-tight zinc cylinders gurgling joyfully over their first victory with the sea.

Perhaps the dark gods of the big waters were amused. Perhaps they knew of the extradition papers in the inside coat pocket of Detective Manolescu—papers signed and sealed by a judge of the state of Louisiana, who, after a preliminary examination, conducted under the Revised Statutes of the United States in relation to extradition, had surrendered Peter Slavnos, of Chartres Street, New Orleans, and formerly of Jaczkovezdo, Hungary, to the judicial powers of the Supreme Court of Budapest. The charge preferred against Peter Slavnos was murder in the first degree.

The Supreme Court of Budapest would not have bothered about Peter under ordinary circumstances. Hungary was not in a position to send detectives around the world hunting for escaped criminals. But this Manolescu had come to the United States as a sort of bodyguard to a high Hungarian official, and as this official did not require his further services, he was ordered to find Peter Slavnos and bring him home. The simple gesture of demanding a refugee murderer from the powerful United States was in itself fine advertising for Hungary.

Detective Manolescu had been ordered by his superiors to make the cheapest possible return with his prey. The Coomassie was bound for the Black Sea, calling at Trieste. Consular entreaties made the oil-company stretch a point, and Manolescu and Peter Slavnos shared a cabin, And now the dark little gods of the Great Waters had played a trick on the old judge and the Royal Supreme Court of Budapest.

"LISTEN!" cried Peter Slavnos. "Some one is speaking!"

A voice, megaphone-fattened, came out of the darkness. It gave steering directions to the boats. 'West, sou'west!" came the command. "Captain speaking! Keep together! West sou'west!"

The scream of the detective went up from the raft. Threaded with hysteria. "Detective Manolescu with prisoner!" he shouted. "Slavnos, murderer! On raft! No compass! No food! No water! Help!"

Again came the calm advice of the captain, the toneless repetition suggesting a reproof. "West, sou'-west! Keep together! Rescue certain!" Of course he had not heard the scream of the detective Manolescu.

Something that might have been a derisive laugh got mixed with the clink of the steel handcuff. The detective cursed his prisoner with Magyar curse words that have a fine corrosive capacity.

Again he screamed of his unenviable position. "Detective Manolescu! Wait! Wait!"

From a thousand miles away—at least it seemed—came the near-Greeley advice of the captain. "West sou'-west! West sou'-west." The small waves struck up through the slats of the raft with a noise like belly-laughter.

The prisoner made an observation. "Once," he said, and his voice was quite calm, "I caught a fish that had just caught another fish. A cod. Had it in his mouth when I pulled him in."

"Shut up!" snapped the detective. "Listen, swine!"

But there were no sounds except the thick-lipped chatter of the raft with the sea. The plop-ploppety jargon of the waves as they swirled the raft in a stately saraband, two-stepped it in a wild rush forward, or banged it down with a spine-shaking wallop into a suddenly formed valley, between waves.

The prisoner had a vision of the Fair Grounds at New Orleans. There, on a spring day, he had ridden with Kolya on a contraption that acted in the manner of the raft. The thing had frightened Kolya. He recalled her sweet, pointed face as she clung to him when the devilish whirling jigger tried to hurl her into space. It was nice to hold her slim body close and listen to her little cries of fear.

Kolya was terrified of many things. Of lightning, of snakes, of the sea. She had a curious fear that the Mississippi would one day lift itself over the levees and come rolling inland to join Lake Pontchartrain. When that fear came upon her he had to hold her till her little heaving breasts became tranquil.... He swore softly to himself. Kolya was alone now! Alone in the little two-room apartment on Chartres Street! And he—"Slavnos, murderer!" the terrified detective had called him. Screamed the words to the listening waters.

He tried to forget Kolya by baiting the Law. That fish simile was good. The fool detective was so frightened that he didn't see the analogy. Slavnos decided to try again. It was painful to think of Kolya.

"That fish that caught the little fish and was then caught by me," he began, "was one—"

Again came the stream of green Magyar curse words. A great fear gave a whining note to the voice of the detective. The sinking of the Coomassie had brought terror.

SLAVNOS was not afraid of the dark sea. Afraid to think of Kolya, but not timid of the waters. He listened to the snaky waves running breathless from the Pole, and he tingled. This sea around him had murdered thousands, millions, but no one could put handcuffs on the sea. No orders from a silly old judge could take it somewhere to be tried for a murder it had committed years before. And the winds that ran with it were its accessories in crime.

Was it crime? He wondered. The sea murdered those who got in its way. Those who mixed themselves up with its wild passionate storms, or those insolent ones who sailed over it in rotten ships like the Coomassie. The sea might find some justification for his own crime. It would understand.

Suddenly he felt curiously kin to it. He tore off his coat and impulsively gave it as an offering to the playful waves. The little geysers spouting from the slats that laced the zinc cylinders together, ducked him again and again. And the warm winds dried him with fingers that made him tingle. This sea that was playing with him was the Sargasso! Dear God! A mighty thing that permitted him to ride on its back. He, Peter Slavnos, on his way to Europe to be tried for murder.... In the dark hours of silence that followed the last whisper of the megaphoned directions he felt strangely humble, and, yet at the same time, exalted.

The light of dawn came slowly, resembling that strange cloudy whiteness of absinthe dropped in water. Peter Slavnos made out the form of the crouching detective; the detective peered at Peter.

Manolescu was suddenly aware of the strength of his prisoner. There was a leopard-like quality about him; muscles moved, like serpents under silk cloths. The detective regretted that he had not snapped the loose handcuff to one of the bars that held the cylinders in place.

When the sun washed away the light fog there were no boats in sight. The raft had the whole floor of the ocean to dance upon. It sloshed and spun and pirouetted like a drunkard. It seemed to be having a fine time.

Manolescu spoke. He attempted to fight the fear that was on him. The fear of the sea, the fear of Slavnos. Slavnos was strong enough to throw him off the raft. The rippling muscles made dumb threats each time his prisoner moved.

"They'll hunt for us," said Manolescu. "Ships that heard the wireless call will be about soon." His words had no body to them. Terror had gnawed the guts out of them.

Peter Slavnos grinned. "Just for the moment I rather like it," he said. "Of course if we get so weak that we cannot hang on to this buck-jumping thing it will be different. Lucky I have the loose handcuff I can snap it to this iron rod."

Manolescu blundered then. "That's a good idea," he said hurriedly. "Why—why don't you do it?"

"Because you have the key," said Slavnos quietly. "If I hooked myself up, it would make me your prisoner."

"You are—you are my prisoner!" cried Manolescu.

"Nonsense!" said Slavnos. "Those porpoises out there are your prisoners also?"

"I'm not talking of porpoises snapped the detective. "I'm speaking of you. I'm going to take you back! Understand?"

Peter Slavnos laughed. He had read of some body of police—Canadian, he thought—who brought back their man, no matter what happened. Manolescu must have read about those chaps. But the "Get-your-man" fellows were tough. Peter's eyes ran over the body of his companion. Manolescu wasn't tough.

Manolescu noted the appraising glance. Slavnos, he thought, was already plotting to kill him. He told himself that he must not doze. And he should make an effort to keep on friendly terms with his prisoner. He remembered with regret that he had used the word "swine" when silencing Slavnos in the night. Undiplomatic, surely.

"You—you might get out of it," he stammered, "The corroboration is lacking. A clever lawyer, y'know. There's always a chance. That's what I told your wife, The last words I said to her—"

"When was that?" interrupted Slavnos, "When did you see her last?"

"Night before we sailed."

"Where?"

"Your place. Chartres Street."

Peter Slavnos stirred. The serpents beneath the silk cloths moved this way and that. "Did she invite you to call?" he demanded.

"No," said Manolescu. "I thought—I thought that I being a countryman of hers—you see we could speak in our own tongue and all that. I thought she would be comforted."

Manolescu fought the blue eyes that settled on his face. Pair of eagles, those eyes! Trying to pick at a secret within his brain. The gaze fastened on his chin. Peter Slavnos recalled a scratch that Manolescu had on his chin the day they left New Orleans. A vivid red scratch. On the left side.

The eyes forced Manolescu to lift his hand and touch the spot where the scratch had been. He knew that it had disappeared, but the blue eyes were staring at the spot. He knew he was a fool, before he could snatch the fingers away.

"Then," said Slavnos, slowly,—oh, so slowly—"it was not the first time you called?"

The spirit of murder climbed onto the raft. Out of the hot blue sunshine it came and squatted between the two men. The raft raced up the face of a slippery comber and dropped into an abyss dug by the wave's passage. Manolescu was thrown forward on his hands and knees.

"How many times?" asked Slavnos.

"Four," said Manolescu. He hadn't the power to lie. And fear made him defiant. Fear of expressed fear.

Slavnos turned his head and watched a school of porpoises plowing toward the sun, welcoming it with fine porpoise artistry. And the silence—the silence that fell upon them—was busy. Fearfully busy. The tense questions and answers, the thoughts, the somber fears and the suspicions, quick-breeding like asps, had created a phantom woman. They had brought her into the white sunshine. A slim gypsy woman with Magyar grace. A woman with great dark eyes in which were stored all the joys and sufferings of her race. Long of limb, with little pointed breasts and hands like flowers. Hands with supple fingers that were never still.

Slavnos saw her in the flashes of sunshine that struck slantwise at the rising waves. Manolescu also, although he was fearful that his prisoner would detect what he was staring at.

After a long silence Peter Slavnos spoke. "You thought you would comfort her?" he said, silkily,

The question was a trap. It was a feint to be followed by a blow. Manolescu was wary now. This Slavnos was a killer.

"Let's forget it," he said. "Why argue about something that is—that is neither here nor there. The matter that concerns us is whether we will be rescued."

He thought himself clever. Rather worldly. What were women when one was facing death? Still the vision of Kolya was there in the great sheets of flashing sunlight that struck the wave flanks.

THEY remained silent like two dogs after a snarl. Mentally regurgitating, dragging back question and answer. Manolescu thought the steel cuff on the wrist of Slavnos increased the strength of his prisoner's arm. Of course it didn't, but it brought an impression of force. A downward chop with that cuff would hurt. He winced.

Slavnos had that long red scratch under the mental microscope. Had the detective gone down to the little apartment in Chartres Street to bargain with Kolya? To bargain? He swallowed with a strange lapping sound. Doglike. Somewhere he had read that the wives and sweethearts of the wretches on Devil's Island sell themselves to the guards to obtain better treatment for their convict husbands and lovers.... Did Manolescu bargain?... The thought was a cold iron gauntlet that clutched his intestines, producing a terrible nausea....

The waves wrestled with the raft. The sun beat down upon the two men. In the reflected light danced the phantom Manolescu took a bold step. He told himself that he had to fight the fear of Slavnos. Fight it with nonchalance. He must show the fellow that he was not afraid.

Manolescu's tongue tricked him. When his ears registered his remark he was startled. Had he really put such queries? He must have. This is what he had said: "How did you come to meet your wife? She is not of your village. I know Jaczkovezdo very well."

Slavnos grinned. Manolescu didn't like the grin. To him there was a devilish humor about it. It said: "You wish to talk about Kolya? Very well, I will oblige you. Later I will bash your brains out with this handcuff and toss you off the raft."

But Slavnos answered the question. Slowly. "She is not of Jaczkovezdo. She is from the Bakony Forest."

Slavnos wished to speak about Kolya. When he spoke of her he saw her more plainly. When he said "Bakony Forest" she rose on a wave some twenty feet from the raft and smiled at him. She had told him many stories of the great green stretches running up from Lake Balaton.

And this hound Manolescu wished to hear about her? Well, he would hear everything. Everything. Later Slavnos would think out a plan. He wondered why the authorities had picked a rat like Manolescu to bring a supposed murderer back from foreign parts. A small, mean rat who made secret visits to the wife of his prisoner,

Slowly, hesitantly, he commenced to speak. "She came to our village on a morning, in spring," he said. "She followed a man who was playing a violin. Followed at his heels like a slave. She was a slave."

HE paused, his head thrust forward.

There she was on the water, close to the raft! Just as he had seen her on that wonderful morning in May. Her strange flexible body that he always said he "could fold up like a ribbon of steel and put in his pocket." Quite plain she was. Her long graceful legs, so different to the legs of the women of the village. So very different. Her pointed face. "Fox-face" he called her playfully. Her long brown fingers that were so very much alive.

"What is it?" asked Manolescu. "What do you see?"

"I thought," said Slavnos, and his voice was lowered as if he thought sound: might dissipate the apparition. "I thought I saw Kolya as she was that morning. Walking behind that—that dog who owned her. No, she wasn't walking! She was—she was swimming! Swimming through the hot air of the valley!"

Manolescu gurgled. Swimming was the word. That was how she moved in the little apartment on Chartres Street. Swimming!

Momentarily off guard, the detective touched his chin where the red scratch had been. The eyes of Slavnos fell upon the point of contact. Those fine fingers of Kolya! Their beautiful pointed nails. Again the iron gauntlet seemed to twist his intestines.

MANOLESCU was startled by the light in the blue eyes. This fellow was a murderer. He must watch himself.

With simulated calm he prompted: "Yes, yes. She came into the village with a fellow who played a violin."

Slavnos, still staring at the water, continued. It was strange, this appearance of Kolya on the waters. He wondered if the sun had affected his brain. The sun and the absence of food and drink. "They stayed in the village," he said. "I thought it was—I thought it was because I prayed that they would stay. Prayed all that May night after I had seen her." Again there flashed the vision of her. That confession of how he preyed pleased her. She was smiling at him.

"I was nineteen," he murmured. "She—she was the same age. The man with the violin was fifty. More, perhaps."

The Law, punctilious, offered a correction. "Only forty-nine when he was—when he died," said Manolescu.

Slavnos started, glared at the detective for a full minute, then continued. "He beat her!" he cried. "Beat her every day! Beat her cruelly!" He struck the zinc cylinder with loose handcuff. The muscles bulged as if they heard a cry for help.

Manolescu crouched as the prisoner swung upon him. "He was small like you!" cried Slavnos. "A rat! His head came up to my shoulder! I—I stood beside him on the day that he came to the village so that I could measure his strength."

The detective tried to muzzle the fear that was upon him. Slavnos was going to confess everything! He was going to tell how the germ of murder had sprung into his mind after he had seen the woman. The pointed face, the long graceful legs, and that strange swimming movement of the slim body had implanted the germ. Manolescu's ears were wide. Corroboration. The fine watchword of detectives. He saw in fancy a red-gowned judge paying him compliments after sentencing Slavnos to death. ("And I must compliment the intelligent detective who, in a position of dire danger, did not forget, etcetera, etcetera.")

"Each day at dusk he beat her!" said Slavnos. "He would drink through the afternoon, and then he would beat her. She would run out of the house with that brute staggering after her. She would hide in the woods, and when he slept off his temper she would creep back. I waited—"

Slavnos broke off, got upon his knees, and then sprang upright. Manolescu tried to follow his example, but the surge of the raft threw him back on his haunches. Leagues and leagues away to the south a feather of smoke appeared on the burnished blue, It wavered like the tail of an invisible cat, now erect, now undulating. The raft seemed anxious to see it. It rushed to the tops of waves and hung there while Slavnos and Manolescu, eyes shaded, stared at it. At times the detective whimpered like a small dog kept from its food.

FOR a half hour the cat's tail showed, then it drifted away. Tramp steamer beating down to Rio. The raft flung itself into a watery valley and geysers came up between the slats, The raft was pleased it hadn't been sighted.

Slavnos took up his recital. "I waited in the wood one afternoon," he said, "Waited till he would chase her into the trees. I thought of killing him then." He paused for a moment, then spoke in a voice that showed a faint surprise. "There were girls in that village. Nine cottages had a flower painted on the outside to tell young men that there was a marriageable girl within, but I didn't want those girls. And I had never spoken to Kolya. We had only glanced at each other when we met on the little street. Yet she knew—she knew that I would be there on that hot afternoon ready to kill. She knew!

"She caught hold of me as I rushed out of hiding; she flung her arms around my neck. and dragged me back into the bushes before that drunken dog had seen me. She was strong. Her arms were around my neck! Around my neck."

Manolescu sighed softly. He forgot the taunting feather of smoke. He licked his thin lips, Beard of Christ! The fox woman with her arms around the neck of Slavnos in a shady wood on an afternoon in summer! A blood-vessel within his head started to imitate a metronome, Tick, tick, tick!

"He was hunting for her, but we lay quiet," said Slavnos, "It was sweet there in the wood. She still clung to me, afraid that I would rush out at him. Her breath was on my cheek. My heart was leaping like a salmon,"

SLAVNOS halted and considered the listening detective. It was nice to talk about Kolya. His confession to Manolescu wouldn't matter, He knew that. Kolya smiled at him from the sun-licked waves.

"After that drunken dog went back to his cottage I showed her how to catch the big spiders," said Slavnos. The memory softened his voice. He smiled in a dreamy way. "Did you ever catch them?" he asked. 'No? It is simple. You warm a little lump of pitch and stick it on the end of a string, You drop the string down the hole in which the tarantula lives. At first he will not touch it because he knows by the smell that it is not good to eat, but if you keep on jangling it up and down he gets mad and then he makes a smack at it with his foot. His foot sticks to it, and when he tries to wrestle with the pitch he gets all stuck up. Then you pull him out of the hole and kill him."

Slavnos looked at Manolescu. There was surely some relationship between the spider and the detective, He tried to find the exact connection, failed, then went on with his story.

"Kolya didn't like that game. She had sympathy with the spiders. She would not let me squash them. She was like that. Always like that."

Again he smiled. He was watching the waves. It was nice to think of that quiet wood, Kolya's body close to him, their faces touching, their eyes upon the hole of a tarantula. Silly of the spiders to hit at the pitch. Again came that thought of a possible relationship between Manolescu and the spiders, When the next apparition of Kolya appeared he would surely understand. The strong sunshine muddled his brain, but when she smiled at him he became suddenly wise.

His dreams were interrupted by a loud cry from the detective. There came a gasped-out question that had upon it the fine fur of vocal terror. "What's that?" screamed Manolescu. "Behind us! Look! Look!" Spears of horror were those words: "Look! Look!"

PETER SLAVNOS turned. A black plowshare drove up through the glittering water. Tore through it like a broad German halberd—a stout glaive cutting through silver-tinted silk.

Another and another! Four! Five! In line formation. Black axes from the depths. Unclean! Fear-breeding! Suggestive. They spoke of lost seas! Heat. Thirst. Green waters beckoning to the unbalanced brain.

"They think we're all washed up," said Peter Slavnos. "Don't put your legs overboard or Hungary will have to give you a pension. You wouldn't listen to that little story I told you about the fish that caught another fish and was caught by me. Looks as if you're doing something like that."

The black plowshares held the eyes of Manolescu. There was a magnetic quality about the dorsal fins as they sliced the water. A dreadful suggestion of murderous force. Their very gathering seemed to kill all thoughts of rescue. Here were the executioners. There was no reprieve.

Peter Slavnos, watching the swirling fins of the escort, was not depressed. He was startled at his own indifference. This company of sharks knew the waters. They had probably calculated the chances of rescue before they attached themselves to the raft. They understood the resistance of the occupants lacking food and water. Cunning devils. They, with their own shark cunning, knew perhaps the distance between the raft and the nearest ship. They knew of ugly weather ahead that would shake the two weakened men from the buck-jumping raft. Yet Peter was amazed to find that, instead of experiencing a fear that would have been natural under the circumstances, he felt a certain exhilaration. A startling exhilaration.

He would speak of Kolya. He would tell this terror-stricken detective more about Kolya. To the devil with the sharks. This confession of his that the detective longed for was something that took his thoughts from the fate that seemed inevitable. And when he thought of Kolya, he was flooded with a belief that he would see her again. A belief that he would comfort her when the fear of serpents, lightning, and the rolling Mississippi came upon her. The good Lord would not leave Kolya alone with her nightmares. The Lord was kind.

Manolescu was watching the black fins, but Peter Slavnos moistened his lips and continued his confession. If Manolescu didn't hear everything the sea would hear. The sea that was also a murderer. The sea might understand and help.

"There was a man in the village who knew more than most," said Peter. "A queer devil of a man. He lived by himself and he sold charms for cattle. And charms for women, so they said. For childless women. Folk were frightened of him. He had a way of looking at you, a way of laughing—so shrill and so high, and no man in the village would contradict him. He knew the history of the Magyars from the days when Zsolt and Taksony led the galloping Magyar horsemen across Europe. He could tell of them so that on wild nights when the wind blew up the valley the listening children saw them. Saw them riding in the black clouds. A devil of a man."

MANOLESCU was trying to listen. For the sharks might not know everything. Now and then the vision of the courtroom in Budapest came into the detective's mind. The congratulations of the judge. Manolescu knew that Peter Slavnos was working up to the murder. The fins were disturbing, but duty told him he should listen to the confession. "He had glass tubes and pots with crooked necks," said Slavnos. "And in them he made mixtures. Folk bought them for this and that. And, if the mixture didn't cure, the sick persons were afraid to say so. For he looked at them with his fierce eyes and they were terrified.

"Now I'll tell you what he did. Look at me! Never mind the sharks! Listen to this! Get it in your ears and carry it to the court of Budapest. Tell it to the old judges who will sentence me to death! This fellow, this devil of Jaczkovezdo, gave out that he had made a mixture that would make men live for a hundred, two hundred, three hundred years. More! You just ate a handful of it and you were immortal. Or damned near immortal.

"Up and down the village he screamed of it. And no one had the courage to call him liar. No, no! They were thrilled. There was nothing in that village worth living for. Nothing, I tell you! They were all poor, horribly poor. They were frozen in winter and baked in summer. They were drunken, shiftless, and immoral. But they had a desire to live. To live for a hundred, two hundred, three hundred years. Tell that to the judges. Justice ought to know the depths of ignorance! Isn't that so? These sharks they don't know that you—you are the representative of the Supreme Court of Budapest! They don't know that you have papers in your pocket giving you power to take me there and have me tried for murder. The sharks don't know. They're ignorant. Ignorant! And God won't tell them that you're a big detective in charge of Slavnos, a murderer! Sing it out to them like you called it to the captain of the Coomassie! 'Detective Manolescu with prisoner! Slavnos, murderer!'"

The Law was listening now. The voice of the prisoner thundered out over the waters. The Law thought that Slavnos had become insane. But it was a confession. A frank confession. The Law was forced to listen. For a moment the sharks were thrust out of a mind trained to absorb every item that would lead to a conviction.

"That hound who—who owned Kolya wished to live three hundred years!" cried Slavnos. "He had no money! Not a single kronen! But he had Kolya! Kolya! And the devil who made the mixture wanted Kolya! Tell that to the judges! Bow before them and tell how this frightening devil at Jaczkovezdo was going to get a soul in payment for making a thieving brutal dog immortal!"

Peter Slavnos paused. The detective turned his back on the swimming escort. He had to hear the end of this. The mood was on his prisoner. If it passed it might never come again.

"And you?" he stammered. "And you?"

"I listened while they bargained!" answered Slavnos. "They didn't know I was there! I listened, I tell you. Then when the stuff was poured out—the stuff that would make one live three hundred years I rushed out at them. Tell it to the judges! Take it all in! I knocked down the fellow who made that mush; and then I caught that other—who would sell Kolya—caught him and poured that stuff down his throat. Poured cup after cup of it. I would give him a thousand years of life! Three thousand! Ten!.... I was liberal. I poured that stuff down his throat with him biting and kicking. Poured it down till he choked and dropped to the floor.... I didn't know that it killed him. Not till you came after me. I just locked the door on them and left them. I met Kolya and we fled. I had heard of America. I had dreamed of it."

A GREAT silence followed the murder story. The sea was glassy. Black clouds shouldered up from over the Caribbean. Manolescu stared at the escort; Peter Slavnos sprawled on the raft and watched for those fleeting glimpses of Kolya that appeared from time to time on the shimmering water. The vision comforted him. Kolya was smiling. Smiling at him.

He pondered over the apparition. Did Kolya think that he would pull through? Could this spirit see the sharks and the black clouds? Or was the whole thing a sort of mirage brought about by the action of the fiery sun on his brain? Perhaps, yet at times he saw her so clearly that he cried out to her. Cried out in a manner that startled Manolescu.

The afternoon dragged on. Manolescu expressed his fear of the night. A storm was coming. And although the sight of the black fins was unnerving, the thought of their being there and yet invisible was more frightening still. And now that he had the confession of Slavnos it would be unjust for death to rob him of the chance to tell it with fine trimmings in the great hall of the Supreme Court of Budapest. Frightfully unjust....

The raft too was afraid. As the dark closed in it made curious movements. At times it spun in circles at tremendous speed. Slavnos had a belief that some giant of the waters had thrust up a mighty digit on which the raft spun like a plate on the finger of an equilibrist. The movement terrified Manolescu. He squealed as the thing revolved.

Then, stopping suddenly, the raft would plunge forward along a greasy stretch where the waves had been curiously flattened as if by fear of the approaching storm. Lightning slashed the darkness at intervals. It showed the escort, the black fins in the silvered water, quite plainly to the two men....

Manolescu began to call upon his saints. His words seemed to whip the raft. As his shrieks became louder the thing turned into a buck-jumping horror. The storm lashed it in the manner of a boy with a top.

The detective was thrown across the raft. He would have gone overboard if the strong arm of Peter Slavnos had not clutched him. The fellow's muscles were loosened with fear. He screamed entreaties to his prisoner.

Peter Slavnos rose to the occasion. He twisted the loose handcuff behind a bar joining the cylinders, then snapped the spare bracelet on the left wrist of the detective. The raft could buck over the moon, but it couldn't unship them. He yelled the news to Manolescu, but Manolescu was crazed with fear. He could not understand.

Peter Slavnos was filled with a wild exhilaration, The sea was angry, but not with him. It knew him. "Slavnos, murderer!" That was what Manolescu had shouted. He, Peter, was kin to the sea. Unintentionally he had committed murder. Perhaps the sea had no real intention to kill. It might, like him, have only intended to frighten, but its strength, like Peter's, brought about fatal results....

At moments when the lightning flashed he saw that vision of Kolya. Still smiling. Comforting indeed as the waves sloshed over the raft. Choking, blinding waves. At times they lifted both himself and Manolescu from the slats so that their safety depended solely on the steel handcuffs. When the waves rushed from beneath them the two were thumped down with tremendous force upon the slats. Again and again the racing waves lifted them, to be foiled in the attack by the handcuffs twisted round the bar.

IN the early morning Slavnos, in a lull in the storm, addressed a question to Manolescu. The detective did not answer. The prisoner shook him. With his free hand he opened the jacket of the other and placed his hand on his heart. Manolescu was dead. The tremendous buffeting had been too much for him.

Peter Slavnos searched the pockets of the dead man. He found the key of the handcuffs. He released his own wrist and sat upright. The sea had gone down. The raft rode easier.

Slavnos was chilled. Something—later he thought it a suggestion that came from the vision of Kolya—prompted him to strip the jacket from the detective. It was quite a task. Then he handcuffed the body to the bar, crawled as far away from it as possible and laid himself down.

He felt very tired and very cold. He thought that death was near. He had no sorrow for Manolescu. In the very height of the storm the detective, fear-maddened, had shouted words at him. He had cried out the name of Kolya. Begged the pardon of Slavnos. Dimly Peter had understood. He was speaking of his visits to the little apartment on Chartres Street. His offers to Kolya had been rejected. Peter, half conscious, recalled the angry red scratch on Manolescu's chin. Kolya's long nails had written an answer for Peter to read. Dear Kolya. Murmuring her name, he slipped into a coma.

The sun came up. The black fins reappeared. Their owners wondered why Detective Manolescu remained on the raft. They knew he was dead. According to all shark experience he should roll off when the raft plunged.

PETER came to his senses in a cozy berth. A dark-faced ship's officer was standing near. He smiled when he saw Slavnos had returned to consciousness.

"That's better," he said, speaking with a foreign accent. "Bad time you have, eh? No bueno. No agua, no comidor! Mucho malo! Better now?"

Peter nodded his head slightly. He was too tired to speak.

"This ship," said the officer, "she is Rocamora. Barcelone, La Habana. We find you sick, your prisoner dead. Captain read papers in your pocket. Understand? You are oficial de policia. Good. Your prisoner he has—what you call them? Brazalete, eh? Steel brazalete tying him to raft. He kill, eh? No matter much when dead. Madre de Dios! Everything finished when man dead. Captain make sailors cut off brazalete, bury him in good style. Old Santo Pedro no know him killer. Joke on old Santo Pedro. Captain make damn' fine talk. Say all men equal when dead man. I go now get you food."

The sea had arranged it! The sea and Kolya! The killing of that wretch in the village of Jaczkovezdo had been unintentional, and the sea understood. All the killings of the Great Waters were accidental. The waves thought that the little ships that were built by man were so much stronger than they really were. The waves played roughly with them, and they fell to pieces.

THE talkative officer was the only person on the tramp steamer who could communicate with Peter. The officer explained that they would reach Havana within three days, and that Peter, if he was wise, should rest in his berth and think of all the evil-doers he would catch in the days to come.

"Mucho malo hombres!" he said, in an effort to comfort the supposed detective for the loss of his prisoner. "Thousands! Millions! Catch 'em all! Si, si! Put de nice brazalete on de wrists."

So Peter Slavnos lay in the berth and dreamed of Kolya. He felt that she knew he was safe now, because she did not appear to him as she did when he was on the raft. Dear Kolya....

The Rocamora rolled in by the Morro light and nosed into her wharf. A shipping reporter from the Diario de la Marina boarded the vessel, and was rushed by the talkative officer to Peter Slavnos. Peter could not speak Spanish, so the officer gave his account of the rescue, stressing his own share in the happening. Peter remained silent. He was thinking out a way of escape. He wished to get to New Orleans with all possible speed. Kolya might be worried about lightning, or there might come to her that strange belief concerning the attachment between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain.

The excited reporter desired a photograph. He beckoned Peter to follow him. Together they went down the ladder to the pier. The reporter placed Peter in the sunlight while he rushed around looking for the photographer connected with his journal.

Peter Slavnos, blinking in the fierce sunshine, suddenly roused himself. For an instant he saw Kolya! Kolya, urging him to move. Quite plainly he saw her in the white glare of the sun upon the sheds! Without hesitation he turned on his heel and hurried along the wharves....

Hours later he came to Machina Wharf where all was bustle and hurry. he finishing touches were being given to a steamer about to move out from the wharf.

Peter inquired her destination, from one of the negroes busy in the loading.

"N'Awlyins," answered the stevedore.

New Orleans! Dear Lord in heaven! Peter Slavnos grabbed one of the boxes and carried it aboard. Dropping it, he walked aft and found a hiding-place. Kolya had surely directed his footsteps to the boat. He was praying as the steamer threshed out to sea....

IT was dark when Peter Slavnos passed Jackson Square. He clung to the shadows of the French Market. He had to be careful. Many persons in New Orleans knew that the long arm of the Law had reached out and grabbed Peter.

The air was hot and heavy. A storm was sweeping up from the Gulf. The wind rattled the signs and whipped the branches of the trees. Drops of rain commenced to fall.

Peter Slavnos turned into Lafayette Avenue, then swung into Chartres. Here was the house. A flash of lightning illuminated the building. He hurried up the uncarpeted stairs to the third floor.

The door was ajar. Softly, on tiptoe, Peter entered. There was a light in the bedroom. He crossed the little sitting-room and peeped.

Kolya was on her knees. She was praying. Her sweet pleading voice came to his ears; thrilled, he listened. "Dear Lord, send back Peter to me! He is a good man. I am so lonely. Send him back, dear Lord, for I am afraid. Afraid in the storms and the long nights."

Peter Slavnos stumbled forward and dropped on his knees beside her. For a moment surprise paralyzed the tongue and limbs of the woman; then with a strange piercing cry she fell into the outstretched arms of her husband....

Minutes later Peter Slavnos spoke. "I am supposed to be dead," he said quietly. "The sea arranged it. I have come back to a new life, but we must go away from here where I am known. Pack up what you want and—"

"No, no, I want nothing!" cried Kolya. "Let us go at once! At once, Peter!"

She took his arm and pulled him to the door. Hurriedly they went down the stairs and out into the night. The storm had fallen upon the city, but Kolya was not afraid. Peter was at her side, Peter—whom the dear Lord had sent back to comfort her.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.