RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

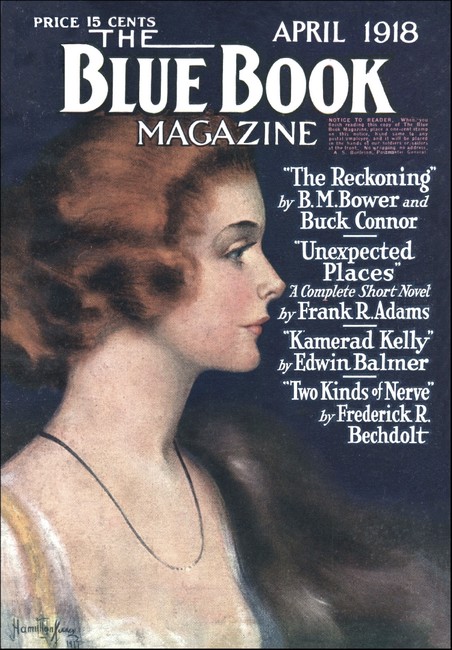

Blue Book, April 1918, with "The Rube and the Rubies"

James Francis Dwyer

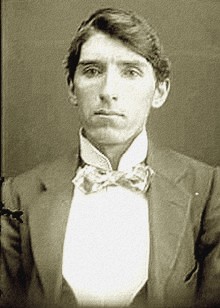

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

HE told it in the "Come-an'-get-it Restaurant," at the rear of the grandstand at Sheepshead Bay. It was "Stampede Week," and New York had been invaded by an army of cowboys and cowgirls who had come to show the Easterners how to "bulldog" a steer, throw a rope and cling to a broncho whose whole effort was bent on hurling his rider in the direction of the nearest planet.

He stood six feet four, was wide of shoulder and so tanned by the Oklahoma sun that his teeth showed dazzlingly white when he smiled.

Said he, in answer to my question concerning the opportunities of New York: "The only two Westerners I ever knew who made good in the East are Will Rogers an' Heck Allen."

I knew of Will Rogers, the cowboy comedian; but I had never heard of Heck Allen.

"Where is he appearing?" I asked.

"Appearin'!" he cried. "Why, Heck's not appearin' anywhere! He's holdin' down a job that puts fifty plunks a week inter his jeans, an' he sort o' roped that job down out o' the pale blue."

I showed interest and a desire to catch the waiter's eye, and so, after a few minutes' interval, the man from Oklahoma told me this story.

"THIS feller Heck Allen was a cow-punch on the Red Shingle Ranch, an' one day he saw an advertisement in a Noo York paper wantin' the whereabouts o' Hector Allen, who was in Kansas City in 1906,

"It's me!" says Heck, pokin' the piece o' paper in the faces of all the other punchers. "I was in Kansas City with a mob o' steers in December, 1906."

"There's more Heck Allens than you," says Long Bill Crowley. "I knew one down in Albykerky."

"Was he in Kansas City in 1906?" screamed Heck.

"Well, I couldn't say that he was," says Long Bill. "He wandered round some, but I couldn't swear that he was in Kansas City."

"That's the point!" yells Heck. "My name is Heck Allen, an' I was in Kansas City in 1906. It's money, that's what it is! Dad's brother went to Noo York an' made a lot o' money, an' I bet he's gone an' left it to me!"

"How d'yer know he made money?" says Long Bill.

"Well, he lived on a street called Grand Street," says Heck, "an' I guess only the swells live there."

Now, this Heck Allen had no more brains than a steer. We wanted him to write to the lawyers advertisin', their names being Kling, Kling an' Kling, but Heck wouldn't. He had six dollars an' seventeen cents when he saw that advertisement, an' the plumb fool started off for Noo York right away.

Heck's six plunks faded away before he was twenty miles from the Red Shingle; then he started to beat it. He was about my height an' a lot stronger; so when the brakemen an' conductors tried to put him off the train, they had to try awful hard. He stuck like a bur in a broncho's tail, an' most of 'em guessed that discussion was the better part o' valor an' said things to him at long range.

Heck rolled inter Noo York on a train that was bringin' a lot o' steers, an' he dropped off an' streaked for a place called Nassau Street, where the three Klings had their law foundry. He was hoisted up seventeen floors; then he hopped through a door that was branded Kling, Kling and Kling an' whooped inter the ear of a clerk who was takin' a little nap.

"I'm Heck Allen!" yelled Heck. "I'm Heck Allen who was in Kansas City in 1906!"

The clerk looked at Heck like as if he was a noo kind of bug, an' Heck got mad.

"What's wrong?" he yells.

"Why," says the clerk, "you're not our Heck Allen!"

"Ain't I?" screamed Heck. "Why, you little button-headed, wall-eyed cayuse, I'll twist yer neck so as you can count the knobs on yer spine! I'm Heck Allen who was in Kansas City in 1906, an' if you say I'm not I'll take yer dead carcass back to Oklahoma to poison prairie-dog with!"

JEST then the fattest one of the three Klings ambled out o' his private office an' wanted to know who had gone an' let Heck off the chain.

"I want me leggersee!" says Heck.

"Yer what?" says the fat Kling.

"Me leggersee!" yells Heck, meggerphonin' with his hands like as if Kling was the other side o' the Rockies. "An' if any bunch o' crooks try to do me out o' it, I'll make 'em look like a squirrel that's gone an' made faces at a cattymount!"

This guy Kling had never met a cow-punch in his life, an' he waltzed over to Heck Allen an' tried to push him out o' the office. Now Heck, on account o' beatin' it from Oklahoma, to Noo York, knew all there was to know about the evictin' business. When Kling made a grab at Heck's shoulder, Heck took the hobbles off a punch that went out an' flopped Kling in his private chuckwagon an' knocked him plumb across the room.

The racket brought two more Klings out o' their holes, but they were as lucky as Soapy Smith o' the Lost Cow outfit. Soapy was waitin' for his girl in a dark lane, an' hearin' somethin' movin', he reached out his arms, thinkin' it was her. It wasn't. It was a bear, an' that bear gave Soapy a hug that made him mighty cautious about matters like that afterward. These two Klings jumped at Heck Allen, an' Heck whooped like an Injun an' did some jumpin' in their direction to encourage 'em.

They say it was some fight in that office, I've seen Heck Allen fight jest for fun, an' I can imagine how he would rage around an' tear up things when he thought those lawyer guys were doin' him out o' his leggersee. He was a lace-edged cyclone, half a score o' mules an' a bunch o' cattymounts rolled inter one section o' amberlatin' manhood.

One o' the three Klings struck the floor, came back with a bounce an' remained standin' long enough ter yell "Police!" inter the telephone; so Heck Allen guessed he had better go away from that place.

Heck ran down the stairs, but the cops was comin' up; so he pushed open the door of an office on the next floor an' went in. A feller was sittin' there in front of a lot of glass bottles like perfessors have, an' he nods friendly-like to Heck an' asks him to take a seat.

"I'm tryin' to do some dellikit experimentin'," he says; "but the guys jest over me have been dancin' a war-dance, an' I couldn't work."

Heck grinned when he said that about the war-dance, an' he told him all about the fight, an' the feller laughed till he nearly fell off his chair.

"You'd better stay here till they get tired o' searchin'," he said. "If they caught yer, they might send yer up for five years."

HECK ALLEN waited in the feller's office, talkin' to him an' tellin' him yarns about Oklahoma. The feller said he might get Heck a job, an' when Heck said he wouldn't mind a job, the feller telephoned another chap, told him all about Heck, what he looked like an' how he would fight, an' the feller at the other end of the wire said that Heck was jest the feller he wanted.

"He says bring yer along this evenin'," said the guy with the bottles, whose name was Pritchard. "He'll meet us at the corner of Thirty-ninth Street an' Fifth Avenoo, an' I'll interdooce yer."

Well, Heck stayed in Pritchard's office till it was dark; then the two of 'em started to walk up to the place where they were goin' to meet the feller who'd give Heck a job. It took 'em some bit o' time to get there, an' it was 'long 'bout eight o'clock when they got to Thirty-ninth Street. The avenoo was nice an' quiet, all the people from the stores havin' gone home.

"He's not here yet," says Pritchard. "Let's walk up a block."

They started to walk up the avenoo, but they'd only gone a few yards when Pritchard stopped like as if he heard somethin'.

"What's that?" he said.

Heck pulled up to listen, an' he thought he heard a woman's moan come from behind a big packin'-case in the doorway of a store. He jumped for the case, an' as he did so, a feller hopped out from behind it an' streaked for a taxicab that looked as if it was waitin' for him. Heck was goin' to chase the guy, but as he turned, a beautiful woman staggered from behind the box an' dropped faintin' inter his arms.

"My jewels!" she screamed. "My jewels! Catch him! Catch him!"

Heck never knew how a taxi guy goin' down the avenoo guessed that he wanted a machine, but he did. The taxi feller pulled up at the curb, an' Heck pushed the lady inter the machine's insides while he hopped up on the saddle with the driver. He forgot Pritchard. The lady was the most wonderful thing that he had ever seen. She had eyes as big as mushrooms, lips redder'n all the poinsetyers yer ever saw bloomin', an' black hair that was so thick on her shoulders that Heck thought it was a shawl.

"Catch him!" she screamed. "He has robbed me of my treasure!"

"Don't worry, ma'am," says Heck. "We'll rope him if we have to chase him to Las Vegas."

Heck Allen was a chap that made everybody else's troubles his'n. He reminded me a lot of an old geek I read about once who went round the country huntin' fer maidens in distress. His name was Don Quick City an' he had a servant named Santy Pansy. If yer ever get hold of the book, jest read it.

Heck told the chap who was drivin' the machine to dig his spurs inter his old hearse, but the feller chatters back about speed laws an' traffic cops.

"Shucks!" yells Heck. "When a hoss-thief is loose in the West, no one talks about speed laws. Which is the little button which makes it go fast?" he says.

The taxi guy points to it, an' Heck put his big foot on it; an' that machine started to gobble up the furlongs like a jack-rabbit that's gone an' run inter a convention o' bulldogs.

FOUR cops tried to stop Heck in the first half-mile o' that run, but they had as much chance o'doin' it as a June bug has of sidetrackin' an elephant. The taxi feller was cryin', 'cause he guessed he'd lose his license, which all the cops was writin' down in their notebooks as he whizzed by, but Heck was beginnin' to enjoy himself. Jest behind him a motor-cycle cop was eatin' the dust the taxi flung in his face, an' police whistles were playin' "There'll be a hot time in the old town all up and down the avenoo.

The lady reached through the winder an' patted Heck on the arm an' looked'up at him with her big eyes, an' Heck trod harder on the speed button. He took part of the stairs off an avenoo-bus that was slow in movin' outer his way, an' the blamed old taxi carried a lump of that stairway half a block an' nearly brained a rheumaticky guy who changed from a turtle inter a mountain-goat when he saw Heck's airyplane comin'.

The thief's taxi was about a block ahead jest then, an' Heck was madder'n a bobtailed scorpion 'cause he didn't have his gun.

"Never mind," he yells out to the lady, "when I catch him, I'll break his neck or poison him or do somethin' else that's nice an' gentle to him."

The taxi feller tried to push Heck's foot off the button that was makin' the wheels go round; but Heck pinched him softly, an' the feller yelled like as if he was bit by a rattler.

"Full steam, skipper!" yells Heck. "Give her her head, or I'll fling yer out an' take the wheel myself."

The thief's bus swung inter the park, an' Heck's little ambylance takes the same trail, three motor-cycle cops, a police patrol an' five other autymobbils streakin' behind.

That park is all full of curly trails that don't go anywhere, an' the thief an' Heck an' the police 'an' all the other autymobbils that was attracted by the chase go merry-go-roundin', tootin' so loud that they woke up all the hobos that was sleepin' on the benches an' all the little monkeys an' ourang-outangs that was housed there jest to show people there is uglier forms of life than themselves. The whole place was a pandemonium, with Heck's little wagon the core of all the fuss.

The thief's taxi took a circ'lar trail an' Heck gave a yell yer could hear at Council Bluffs.

"I've got yer, yer low-down varmint!" he shouted. "I've got yer cornered!"

BUT Heck hadn't. That thief hopped from the taxi an' took to the timber, an' Heck went after him. He dived plumb from the seat an' nearly broke his neck over one of those "Keep off the grass" signs. But he was game. Every yard or so he tripped over a piece o' wire that some fool had put up to keep people from walkin' under the trees, but he always picked hisself up in time to hear Mr. Thief scootin' away in front o' him.

"I'll get yer!" yells Heck. "I'll get yer if I run yer out to Oklahoma!"

Heck struck a little clear patch in the middle of which was a statoo of a feller holdin' his hat in his hand, an' jest as he reached that clearin', he lost track of the thief. There was a moon, an' Heck could see clear across that patch; but the jewel-swiper had disappeared.

Heck stood close to the statoo an' looked around. He was awful mad to think the feller had got away from him, an' he thought how tough it'd be to go back to Miss Big Eyes in the wagon an' tell her that the thief had given him a pair o' clean heels.

"The durned sucker!" he says. "I'd give my noo spurs an' rope to get a clutch on him!"

Jest as Heck says that, somethin' dropped on the cement at the foot of the statoo, an' he stoops an' picks it up. What d'yer think it was? 'Say, yer couldn't guess in a year. It was a ruby, a big red ruby, most as big as Heek's thumb, an' Heck stared at it with his eyes bulgin' out.

There was another little tinkle on the cement, an' Heck stooped an' picked up another; then he jest stopped plumb still an' stared at one o' the legs of the statoo. That leg started to stream rubies, scores an' scores o' 'em, big red stones that glittered in the moonlight an' made a little pile that was like blood where they fell on the cement.

"Oh, gosh!" gurgled Heck. "Oh, gosh!" he says; an' as he said it, he made a jump an' grabbed the legs o' the statoo an' dragged him down onto the grass!

The thief guy who was maskyradin' as the statoo—him havin' found a block of marble doin' nothin' an' clawed hisself up on it—was some little bear-cat when he went to the mat with Heck Allen. Heck was used to bulldoggin' steers an' wrestlin' with guys who didn't care if they took the crease out o' their trousers while wrestlin', but he had one pesky parsnip in that ruby robber. The two of 'em rolled down the clearin' like a garden-roller an' rolled back ag'in so as to make sure that all the daisies had been murdered. He got Heck by the hair, an' Heck yelled, an' jest as the lady came through the timber along with the cops an' the bunch of hobos, Heck got a grip on him an' sat up on his chest.

"I've got him, ma'am," says Heck, "an' there's yer jewels on the ground,"—pointin' to the pile of rubies near the statoo.

The lady gave a little joy whoop an' flung herself at the stones, while the cops had to form a ring an' use their hick'ry sticks on the heads o' the hobos who tried to give her a hand at pickin' up the rubies.

"Oh, my jewels!" she cried, scoopin' 'em inter a little bag. "Oh, my beautiful jewels!"

Well, Heck Allen an' the cops an' the crowd watched her doin' that. The thief couldn't watch 'cause Heck had his nose driven inter the ground an' was sittin' on his back, but the others wouldn't so much as blink, for fear they'd lose sight of the jewels. Some o' that bunch o' fresh-air leaguers hadn't seen a five-spot since their dads flung one to the parson for christenin' 'em: so you can guess how they stared at the rubies.

WHEN the lady had gathered all the rubies up, the biggest cop got a clutch on Heck's prisoner an' lifted him to his feet.

"Lady," says the cop, "did this man try to rob yer?"

"Yes, yes," she says, "he was my sekkertary, an' he tried to steal my jewels."

"D'yer give him in charge?" says the cop.

"What is that?" she says.

"D'yer give him in charge?" chirrups the cop. "D'yer want me to arrest him?"

"No, no!" cried the lady. "I don't want him arrested. I'm goin' to India to-morrow, an' I can't wait to prosecute him."

One of the other cops opened a fat notebook an' says to Heck Allen, "What's her name?"

"Search me," says Heck. "I never saw her till this guy was gettin' away with her jew'lry."

"Ma'm, will yer tell me yer name an' address?" he says.

"I'm the Maharanee of Bahdpur," says she.

Those cops were ignorant guys. They looked at each other; then the silliest one o' the bunch says: "Yer say yer name is Mary Ryan an' yer came from Badport. Where's Badport? In Jersey?"

"No, no," says the lady. "I'm the Maharanee of Bahdpur. I'm a princess. Me husband is a roger."

Well, the cops scratched their heads an' looked at the lady an' Heck Allen.

"Where are yer stayin'?" says one o' the cops, speakin' to the lady.

"I'm stayin' at the Plaza," says the lady. "I've five rooms there."

Well, that little statement made the cops sit up an' take notice. An' Heck Allen opens his mouth too. Here was Heck, jest in outer the big grass-patches o' Oklahoma, an' he gets all mixed up in a thing that looks like the mainspring of a dime novel.

THREE newspaper reporters got there jest about that time, an' when they started to fire questions at the lady, she turns to Heck an' asks him to see her to her hotel. "But before I go," she says, "I must reward the p'licemen. If they hadn't been here, some o' my jewels might have been stolen."

She put a little hand that was whiter'n a clean tablecloth inter the bag, an' she forages round till she found eight stones that she thought were a nice size for scarf-pins for cops. She gave 'em one each an' knocked 'em so plumb silly that they couldn't thank her. When she did that, she turned an' looked at Heck Allen, who was pushin' the newspaper men away from her.

"You are a brave, brave man," she says. "Put yer hand inter this bag an' take what yer think is a fair reward."

Now no one had ever told Heck Allen to help hisself to rubies, but he was not a greedy guy. He jest stuck his big paw inter the bag an' took one good-sized stone.

"Take another," says the lady.

He stuck his paw out on another foragin' expedition an' fished up one that was bigger'n the first.

"Do it ag'in," says her ladyship.

"Oh, shucks," says Heck, who guessed he had about ten thousand dollars worth o' jew'lry in his hand, "I got two now."

"Three is lucky," says the Maharanee.

Well, Heck dived ag'in an' cops a stone that was near as big as a duck-egg.

"Oh, gee!" he says. "I've gone an' hooked the Jess Willard of yer collection!"

"Nonsense," she says. "Where that ruby came from there is hundreds of others, an'," says she, speakin' sort o' dreamy-like, "I own the Bahdpur mines, where they come from."

When she said that, those newspaper guys an' the crowd in general unloosed an "Oh°" that yer could hear over in Noo Jersey. The park hobos were lookin' hard at the bag, so Heck reminds her of her intention of gettin' back to her hotel. One o' the reporter idjuts unloosed a flash-light that half scared her to death, so Heck steered her back to the taxicab quick.

Well, the cops came along 'cause they thought she might give 'em another ruby, an' the crowd came 'cause they thought some one might knock the bag outer her hand. An' the newspaper guys hung to the percession like flies to a hairless pup, askin' a thousand questions o' Heck Allen an' the cops.

The Maharanee got afraid as the crowd got bigger, an' when she got to the hotel, she jest squeezed Heck Allen's hand, looked at him quick with her great big mushroom eyes an' ducked inter the elevator, the manager, the night-clerk an' six porters tryin' their durndest to keep the crowd from streamin' up the stairs. There were other newspaper guys there then, an' they were firin' questions at Heck Allen till Heck got plumb sick o' 'em.

"Yer can go straight to Jericho!" he says to one little rat who was that small that he didn't reach up to Hack's gun-belt. "If yer don't stop pullin' at me, I'll cut the top off yer empty head an' use it as an egg-cup!"

ONE o' the cops told Heck he oughter be careful o' hisself on account o' havin' the three big rubies in his pocket, so Heck slipped out a side door an' started down the street. It was gettin' late, an' Heck remembers that he had no money an' no place to sleep. So he jest thought he'd pawn one o those big rubies so as to get a bed for hisself an' somethin' to eat.

All the pawnshops were closed, every durn one of 'em, an' Heck Allen tramped up an' down the streets tryin' to think out how he could get some coin. The only guy he knew in Noo York was Pritchard, the feller who brought him up Fifth Avenoo to get him a job, but he had lost Pritchard when he started after the Maharanee's sekkertary. Heck was a bit skeery 'bout stoppin' strangers in the street an' tryin' to sell 'em rubies that was bigger'n walnuts. He was like ol' Sam Whitty who found the White Prince Mine. Sam had no water, but he had a chunk of gold that weighed a hundred an' eight ounces; an' he would have given that big chunk for one bottle o' beer.

"Well," says Heck, "I've got a fortune an' it'll keep. The only thing I can do is to keep walk in' till the pawnshops open. If I go to sleep on a park bench, I won't have any rubies in the mornin'."

So Heck Allen started to walk up one avenoo an' down another, an' every now an' then when there was no one about he would stop under a lamp an' take a peep at the three stones. "Wow," he would say, every time he brought 'em out to give 'em the once over, "I'll get inter some good clothes in the mornin', an' I'll go up to that big hotel where she's stayin', an' I'll put up there too."

You see, all the time Heck was hammerin' the avenoo he was thinkin' of the Maharanee, thinkin' of her big eyes an' her lips that was redder'n poin-setyers, an her black hair. He couldn't think of anythin' else. She had said she was married to a roger, but Heck had a fool idee that if she saw him dekkyrated in good clothes she might hire him to run the ruby mines out in India. As I told yer, this Heck Allen didn't have no more brains than a steer, but he was a powerful big dreamer.

When it came daylight. Heck was way uptown; so he turns an' steams back to the middle o' the city. There was pawnshops up in the part o' the town he was in, but Heck guessed that none of 'em had enough money to give him what he wanted on one of those rubies. He wanted an awful lot, enough to buy eleven suits of clothes an' a lot o' shoes an' hats an' shirts an' collars an' things like that.

Heck came down Fifth Avenoo lookin' for pawnshops, but there was none there. He asked a cop when he got to Thirty-fourth Street, an' the cop told him to go over to Sixth Avenoo; so Heck swings cross town, his big hand holdin' the three rubies.

HECK was passin' the Waldorf Hotel when he saw a crowd in front of a shop that had jest opened, it bein' then about eight o clock. People were millin' round like a bunch o' steers tryin' to get a look in that winder, so Heck thought he would take a squint to see what was there. He was taller than most of the people, an' he could see right over their heads.

What d'yer think Heck Allen saw? Yer wouldn't guess in a year. Bet yer a dollar yer wouldn't! That winder was chock-full of brooches an' bangles an' stickpins, all with rubies in 'em, great big shinin' rubies. There was a little pile o' rubies about two feet high right up near the front, an' on the pile was a sign readin': "Bahdpur Rubies! The greatest imitation ruby in the world! Cannot be detected by experts. Any one of these magnificent stones for sixty-nine cents!"

That wasn't all, either. All the front o' that store was pasted with the first pages o' the mornin' papers, an' what those papers didn't say about the Maharanee of Bahdpur an' the rubies that she grew an' watered in her own back yard could be written on the back of a postage stamp. There was a lot about Heck too, an' a photygraph o' him as the feller with the flash-light took him.

Heck stares at the show for about five minutes; then he tramps inter the store. A man behind a counter gave one look at Heck an' ducks down quick, but a woman with big mushroom eyes an' two lips the color of pointsetyers hops out of a little cage labeled cashier an' grabs Heck by the two hands.

"Oh, I knew yer'd find me!" she cried. "I knew yer would! I wanted to see yer an' ask yer pardon. I couldn't, last night, 'cause that would have put the show away, an' it was goin' so splendid with all the little reporters askin' questions!"

"An' you're not a Maharanee?" says Heck.

"No, no, no!" cried the girl, "I'm jest a plain American girl. My brother, Mr. Pritchard,—you met him yesterday,—invented these rubies, an' we planned to get some free advertisin'. Then you came along, an'—an'—an'—I'm sorry," she says, "hut you was jest perfectly splendid. Jack, come out an' speak to Mr. Allen. You're not angry, are yer, Mr. Allen?"

"Angry?" says Heck. "Why I couldn't be angry with you if yer took me for a sheep man an' fed me on mutton for seven years. Angry? Why, I'm tickled to death at bein' able to help yer out. An' you certainly kidded those little newspaper guys a treat."

WELL, the girl's brother came out an' spoke to Heck, an' it ended up that Heck stayed an' went out to lunch with the two of 'em. John Pritchard offered him a job in the store, an' Heck took it. Yesterday I met him, an' he told me he was gettin' fifty plunks a week. He took me inter the store an' interdooced me to Miss Pritchard.

"What d'yer think of her, Bill?" he says to me when we came out.

"Think o' her?" I says. "Why, Heck, she is a Maharanee!"

"Of course she is, Bill," he says. "She is a Maharanee for sure, an' next week, Bill, I'm goin' to be her roger, her durned ol' cow-punchin' roger from the Red Shingle Ranch in ol' Oklahoma!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.