RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

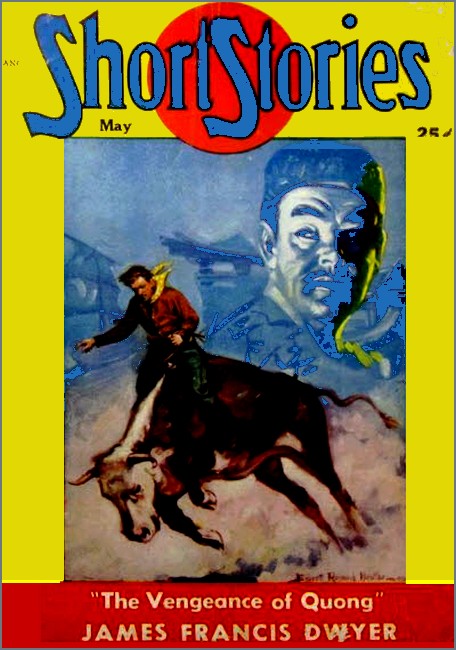

Short Stories, May 1951, with "The Vengeance of Quong"

James Francis Dwyer

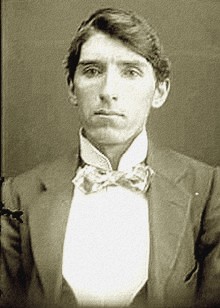

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER (1874-1952) was an Australian writer. Born in Camden Park, New South Wales, Dwyer worked as a postal assistant until he was convicted in a scheme to make fraudulent postal orders and sentenced to seven years imprisonment in 1899. In prison, Dwyer began writing, and with the help of another inmate and a prison guard, had his work published in The Bulletin. After completing his sentence, he relocated to London and then New York, where he established a successful career as a writer of short stories and novels. Dwyer later moved to France, where he wrote his autobiography, Leg-Irons on Wings, in 1949. Dwyer wrote over 1,000 short stories during his career, and was the first Australian-born person to become a millionaire from writing. —Wikipedia

Buck Bigthumb and Dan'l Boone Meet China

WHEN Buck led the Chinaman, Quong-li, into the large courtyard of his home their arrival created much excitement. Coolies working in the yard, took one glance at their rich master, noted the disarray of his clothing and emitted yells of alarm. Women came running from the private quarters. The Number One wife of Quong and three other females holding secondary positions in the household, burst from their rooms and with twittering cries surrounded their lord. A large chair was dragged into the shade of the willow tree and Quong sank into it. A boy rushed forward with a bowl of rice-wine.

Quong, after drinking, explained to the women who smothered him with questions. He had been attacked by footpads in the neighboring village of Hu-san, but his companion had saved him. He placed an arm around the neck of Buck and interrupted the flow of Chinese to murmur: "Ma fine Melliken flend. Heem cowboy." Quong-li had lived for some years in San Francisco and he loved to trample on the American language at every opportunity.

The women wished details, and Quong, after a second bowl of wine, gave them. The gangsters had asked for money, but he had bravely resisted their demands. They had knocked him down and kicked him. They had snatched his money-belt and were running away with it when his American friend arrived. His friend had thrown a rope which caught one of the fleeing thieves by his bare leg and brought him to the ground. Luckily he was the bearer of Quong's money-belt. The police came up, the money was returned to Quong and the thief was locked up.

The four women bowed to Buck, who seemed slightly amused by the account of the incident. They murmured their thanks for the assistance he had given to their master. They had flat, yellow faces and were middle- aged. Their clothing, although rich and colorful, did not add to their appearance and Buck wondered as he studied them. The Chinaman, immediately after the rescue, had engaged the cowboy as a bodyguard and he had boasted of the beauty of his womenfolk,

He had affirmed their good looks in his own tongue and also in what he considered the American language. "Velly booful!" he had cried. "Velly fine womens!"

Of course the Chinaman was a dreadful bounder. A fat, drunken brute who loved to adopt a patronizing attitude towards his betters. He was also a liar. He had not told the women the truth of the affair. He had stumbled out of an opium joint and had lain stupidly by the roadside when the thieves had started to roll him. He had put up no fight against the attackers.

Buck wondered now if the Chinaman had spoken of four women or of five in his household, and, as he puzzled over the matter, a fifth female swept into the courtyard.

She came with a sudden rush that pulled Buck from his seat. She was unusually tall and as supple as a branch of the willow tree. She was dressed in pajamas of green silk. Silk that seemed to show a kittenish delight in clinging to her graceful limbs. Her black hair was loose, and while the other women walked in a clumsy fashion, forced on them by their footgear, she seemed to swim through the hot air as she approached the group.

Bowing low before Quong-li she listened to a repetition of his story, then Quong introduced Buck. "Ma Melliken flend," he said to her, and to Buck he uttered two words. "Manchu gal," he grunted, and he laughed loudly.

The girl—she seemed to be under twenty—showed evident astonishment at hearing Quong's pronunciation of the word "American." She bowed gracefully and then cried out a question. "Is it true?" she gasped, "True what the Honorable Quong-li says? Are you—are you an American?"

Buck, upset by the question and the faultless manner in which it was put, stammered out an answer. "I—I was born in Texas."

The girl regarded his face with her large eyes. "But—but you are not—not— Oh, what will I say? You are not—not a "real American?"

BUCK swallowed uneasily. He felt that the question had destroyed the fine feeling of superiority that had been his before her arrival. The four stupid women and their fat patron had made him think that he was something above them, but this graceful girl, although tinted, had thrown him off his pedestal with the words, "You are not—not a real American?"

"My father was an Indian," he said, "A Chief in the Tangan tribe, and my mother was Mexican." He raised his voice as he continued, "But I was born in Texas and I fought with Americans in the late war."

"Pardon," murmured the girl. "I didn't mean to be offensive. Please tell me your name?"

"I was christened John Bigthumb, but I am known as Buck."

"And may I call you Buck?" she asked, smiling.

"Why, yes," he cried. "You can tell me anything you like." Then, smiling at her, he asked, "How come you speak the American language so perfectly?"

"I was educated in a convent at Canton. Two of the Sisters were Americans."

Quong-li, who was all ears as Buck and the girl were exchanging remarks, now butted into the conversation.

"Fodder beeg mans," he said, pointing to the girl. "Muchee money. Losem eblythink." He drew a forefinger across his throat, suggesting a suicide.

A red flush appeared on the cheeks of the girl. "Father was unlucky in speculating." she murmured. "It was the war that ruined him."

The Number One wife wished to take Quong into the house, but he objected. He was in a contrary mood. He called for another bowl of wine, and after swilling it down he thought the moment favorable to speak of the ability of his new employee. "Ma flend," he began, speaking in his pigeon-American to the Manchu girl, "showem you funny bizness wiv lope." He spoke to the four Chinese women, bringing a look of life to their dull faces. The four watched the girl, and to Buck it was plain that they held a joint hatred for her.

Quong grinned as he made a motion of his hand to Buck, then he cried a command to a coolie who was crossing the courtyard. The servant approached, and Quong with great volubility, instructed him to stand still till he, Quong, gave him an order and then to run swiftly towards the big gate opening on the road.

Grinning with delight he turned to Buck. "Lope heem," he commanded, "'bout ten yards."

Buck started to make objections, but Quong showed temper. "Queeck!" he cried impatiently, so the cowboy took from his pocket a rope that he had stolen from a Buddhist Monastery at Tung-chow on his way up the Yangtze and uncoiled it. He had accepted service with Quong-li and had to do his bidding.

The waiting coolie looked suspiciously at the rope. Other coolies stopped their work and watched. There was silence in the courtyard.

Quong-li gulped down another basin of rice-wine, then made a gesture with his fat hand to Buck and at the same time he shouted a command to the coolie.

The poor half-naked devil started for the gate at full speed. Buck had a moment of hesitation, fearful that he might hurt the fellow, then he tossed the rope.

It fell around the bare, chest of the runner, threw him off his stride and flung him backward with a curious display of legs and arms. He created a cloud of dust when he fell.

Quong yelled with glee. Number one wife and the three concubines standing beside her followed the example of their lord by mildly showing their amusement, but the Manchu girl expressed her indignation.

"That was cruel!" she cried, addressing Buck. "You hurt him."

"Not much," muttered Buck.

"But you did," she asserted.

"I'm sorry," he murmured. "I have been hired, and at the present moment I am broke."

The Manchu girl turned and walked swiftly through an evening in the wall that led to a smaller yard. The coolie picked himself up and limped back to his companions.

Quong recovered from his laughing fit and waved the four women away. He called for more wine.

Turning to Buck he said: "You tink Fa'hey Lily nice?"

Buck reasoned that Fairy Lily was the name of the Manchu girl, the word Fairy troubling the tongue of the Chinaman. "She is very pretty," he said.

"Peoples one time beeg peoples," hiccuped Quong. "I buy Lily. How much you tink?"

"I couldn't guess."

'Two thousand Mex," said the Chinaman proudly. "Velly much money. You like talkee her?"

"Why, yes," admitted Buck.

"Alli. She eat you an' me."

BUCK BIGTHUMB, in the quarters to which Quong-li took him, came to the conclusion that he had taken service with a rich and dissolute person. But Buck's finances at the moment made him seize the position with avidity. He was at the end of his rope.

Stretched on the many-quilted bed he reviewed his movements since the end of the war. He had served in Papua, helping to stop the wild rush of the Japanese upon Australia. There he had heard much from Australian soldiers of the wealth of their big island, and when demobilized at San Francisco he had hurried back to Sydney thinking to get a part of it. Buck couldn't find it. He went northward, through Banjermassin and Singapore and finally landed at Shanghai. There he had paused for nine months.

It was a strange move of fate that sent him up the Yangtze. In a bar oh the Ningpo Road he had been questioned by a cunning Englishman as to his birthplace. Buck was annoyed. He answered snappily. "I was born in the biggest hunk of land that is left in one piece," he said.

"What's its name?" questioned the cunning one.

"Texas," snapped Buck.

"Huh," said the questioner. "You don't know you're alive, boy. This China could pack some fifteen cow paddocks like Texas into her belly and have room left over."

Buck had never studied geography and the statement annoyed him. He had always heard that Texas was a mighty large piece of ground and the jeering stranger taunted him. He put up his last ten dollar bill to back his belief, the American Consulate on Whang-poo Road to decide.

The counter clerk gave a decision against Buck which made him angry. He used rude words and a Chinese doorman was told to put him outside. The fellow caught Buck by the arm and proceeded to take him roughly to the street, but he got a surprise. The cowboy tossed him across the room, and in transit the fellow broke a globe of the world and smashed a chair.

Buck fled. Some time later he came to a wharf where a boat was just moving away. He sprang aboard without ticket or money.

A uniformed official was immediately beside him. "Ticket, please?" he said.

Buck parleyed. "Where are we going?"

"Up the Yangtze," said the other. "Jardine, Matheson boat. First stop, Tung-chow."

"Sorry," said Buck. "I forgot my pocket-book."

THEY flung him off at Tung-chow. The police had no desire to interest themselves in the matter, so Buck strolled around. He found a Buddhist Monastery and offered to amuse them. He borrowed their clothesline and did some fine rope work which delighted them. When the boss of the monastery handed Buck a handful of copper cash he, Buck, slipped the clothesline into his pocket for future adventures on the big river.

He went on to Chin-kiang in the same careless fashion as he had boarded the first boat. Was tossed off, humbugged the police called upon to arrest him and did a little performance with the rope on a vacant piece of ground. He took a certain joy in his travel methods. He listened to stories concerning the three terrible rapids on the river and they excited his curiosity.

The I-chang gorge thrilled him. He decided to go through the two others and then return to Shanghai. He did so, and then, tired of the river, he looked around for the means of getting back.

It was then that he saw a fat Chinaman being kicked by a trio of ruffians. He tossed the rope at the last of them, dragged him to the ground, received the thanks of Quong-li and the offer of a job.

"And a damned rotten one," he soliloquized, as a boy announced that Quong awaited him at the table.

THE Manchu girl had changed her costume for the meal. Now she was dressed in a kimono of soft blue silk and her hair was banded with a blue ribbon. She had recovered from her fit of temper and she saluted Buck gracefully. Quong-li was evidently an autocrat in his house. The Number One wife came into the room, thinking to take part in the meal, but he roughly ordered her to leave. Only himself, Buck and Fairy Lily sat at the table.

Quong-li had consumed more wine since the incident of the morning. He was nearly intoxicated, quarrelsome with the servants and boastful in his talk to Buck and the girl. He ate in a greedy fashion, using his chopsticks wildly and talking with his mouth crammed with food. He was the salvation of China, according to his own belief. He had been to the United States and he was introducing American ideas into the country. American ideas were extraordinary. "Wunnerful! Wunnerful!" he shouted, after describing every labor-saving device he had seen. "Mellikens big blains! Velly big blains!" He gripped his head with his two hands to show Buck where the thinking processes lay. He was, he asserted, going to bring a thousand American ideas into China.

Near the very end of the meal he mentioned the longhorn bull. That very year he had thought of turning his huge property into an American ranch, breeding cattle instead of wheat, millet, soy and rice. He had heard through the Chinese paper, Sung-poa, that an American cargo boat had come into the Woosung with a load of cattle. It excited him; he had dashed down to Shanghai and boarded the steamer. A shrewd New England captain had sold him a longhorn bull.

"A bull!" cried the astonished Buck.

"Shih, shih!" cried Quong. "One bully bull! Heem horns so long!" He stretched out his arms to show the length of the animal's horns. 'You wantem look see?"

Buck was startled by a soft kick that he received in the right ankle at the moment, but he answered promptly to the proffered invitation. "Why yes," he said, "It would be right in my line."

He decided in the moments that followed that the kick had been delivered by the soft slipper of Fairy Lily, but why he couldn't tell. He sat back and listened to the Chinaman telling of the trouble that he had in getting the bull up the Yangtze.

It appeared that the animal didn't like China. The frightening odors troubled his bull brain. Instead of the perfumed winds of the western prairies his nostrils encountered the stench of rotting vegetation, stuffed drains, sweat, excrement, and all the other odors of an old world. At Tien-hsing-chiau he broke out of the junk and injured two coolies, and at Kiu-kiang, famous for its pottery, the bull escaped a second time and wrecked a dozen stalls before he could be secured. The town kept Quong as a semi-prisoner until he made good the damage.

"One bully Melliken bull," grunted Quong, then exhausted by the telling and the amount of rice-wine that he had consumed, he fell asleep.

The girl, Fairy Lily, waited patiently till Quong was snoring loudly before she spoke. Leaning across the table she whispered to the startled cowboy. "You mustn't go near the brute," she hissed.

"Why?" asked Buck.

"Because he is dangerous," she gasped. "He—he might kill you!" Alarm showed on her face. Buck was thrilled.

"I know bulls," he said softly. "I was reared with them."

"Not with beasts like him," she murmured fiercely. "And I—and I want your help. Want it badly."

Quong-li made a queer rumbling sound with his throat and woke up with a wild start. Immediately he remembered what he had been talking about when he fell asleep. "Me showem bull tomolly," he said, then he rose and staggered away. Fairy Lily gave the cowboy a searching glance and followed Quong. Buck went to the quarters that had been assigned him. He felt a little uneasy.

THE visit to the longhorn was postponed on account of the indisposition of Quong-li. The effects of the kicks and blows of the gangsters kept him to his bed. He sent a message to Buck telling him to amuse himself by looking round the property.

Fairy Lily was not on view during the morning, but in the afternoon Buck exchanged a few words with her. She was hurried and excited and tossed quick answers to his questions.

"What did you mean yesterday?" he asked. "I mean when you spoke of my help?"

"To get me away from here!" she cried.

"But—but ain't you married to him?" demanded the cowboy.

"No, no, no!" she shrieked. "I have been bought to be—to be his—his—" One of the other women appeared at this moment and Buck missed the last word as the girl ran. For hours he tried to think what it was. He came to the conclusion that it was "concubine."

Buck Bigthumb had had little education. Very little. In the night he lay awake thinking of the word. He was ignorant of its meaning.

He had a vague idea that he had heard it before. A soldier at Port Darwin had used it in the company of Buck, but he had never explained what it meant. Yet it had left a queer feeling in the mind of the cowboy. He had thought of it as a "bad word." A word that should not be uttered in public. A word that should not be spoken before females. Then why the devil did the fat and dissolute Quong-li apply it to the girl, Fairy Lily? Buck made comparisons between China and the United States. They were unfavorable to the former. His stay in Shanghai had proved to him that many happenings in the Chinese city would have not been permitted in any American town. He expressed himself aloud in the hot darkness. "No, they darned well wouldn't," he growled. "I guess we're a whole lot cleaner than these yeller dogs." The word "we" comforted him. He was an American. An Indian, yes, "but an American Indian with American manners. He would stay around and see what he could do to help Fairy Lily. She had been educated by American nuns so she had ideas of American life.

QUONG-LI was ready for the journey the next morning. The pen where the bull was confined was at the extreme end of the Chinaman's property. Quong rode in a sedan chair while Buck straddled a donkey. Number One wife, the three Chinese women and Fairy Lily farewelled them. Buck thought that the Manchu girl looked tearful.

At the end of an hour's ride Buck sighted a circular building With walls some fifteen feet in height. Quong pointed excitedly. "Heem locked up!" he screamed.

Buck was amazed. When they reached the huge corral the Chinaman explained. Under pressure from the local police he had been forced to erect the walled building and enclose the bull within it. Two coolies, acting as guards, were sitting on top of the wall when the visitors arrived. Two others, who had been on night duty, were asleep in a nearby hut The police had ordered a guard night and day on the American animal.

Filled with wonder Buck wished to see the bull at once. He climbed by a bamboo ladder to the top of the wall, Quong, on the ground, screaming warnings about the danger. Quong had no desire to see the animal. He remained in his sedan chair.

Buck reached the top of the wall, straddled it and stared at the lone prisoner. A big longhorn standing quietly in the middle of the filthy yard. A yard that had never been cleaned since the unfortunate animal had been thrust into it.

For fifteen minutes he stared, oblivious of the yells of Quong-li. He felt strangely upset. He had a feeling that he was not in China. The sight of the beast in the filth of the corral had suddenly swept him across oceans. He was in America! He was in Texas! He was on a ranch where he had spent happy days before the war.

Suddenly a thrill of delight passed through his frame. The body of the bull was caked with dirt, but the brand showed! Buck recognized it. He gave a cry of joy. He recognized the bull!

The coolies on guard thought that the strange visitor had become suddenly insane. With fierce energy he dragged the bamboo ladder from outside the wall and dropped one end of it into the pen. The guards screamed of danger, but Buck ignored their yells. He was scrambling down the rickety construction into the dreadful filth of the yard! While they stared he had dropped from the lower rungs and stepped towards the bull!

The longhorn turned his head at hearing Buck's approach, He wheeled, tossed his head and gave every indication that he objected to intruders on his solitary life.

He was on the point of charging when Buck cried out a single word in a voice of thunder. "Boone!" he shouted, and his cry could have been heard a mile away. Then, as he moved slowly, forward, he added, "Dan'l Boone! Don't you know me?"

The angry longhorn had paused at the cry of "Boone." It had an effect upon him. He stood in the center of the pen and stared at the man who was slowly approaching.

The words seemed to have stirred his bull brain. He tossed his head as if making an effort to remember, and Buck spoke softly now as he walked towards him. "Boone," he said soothingly, "it's Buck. Buck who fed you when you were a little fellow. Buck Bigthumb who christened you. Gave you the name of a great American, Dan'l Boone."

The watching coolies had ceased their screams. Now (hey were jabbering answers to Quong-li. They were speaking of magic: extraordinary magic that the visitor was making within the pen. They shouted unbelievable news. The American was reaching out his hands to the bull, the bull who remembered.

Buck touched the animal. He scratched his right ear and whispered to him. "You remember, Dan'l Boone? Remember me at the ranch in Texas? Dear old Texas. Of course you remember? These dirty dogs have locked you up in filth, but I'll get you out, Wait a few minutes and I'll have you free, Dan'l. Wait!"

Buck screamed orders to the coolies on the wall. He cursed them for their slowness. Slowness caused by the paralyzing quality of the scene they had been witness to. He exited them kui-eul-ze—children of turtles—and threatened to beat them senseless if they didn't show speed. He had taken a quick glance at the inside of the bull prison. There was no opening. The animal had evidently been thrust within and then the opening hurriedly bricked up. Dan'l Boone had been immured like a prisoner in the Middle Ages.

ANGRILY Buck screamed for picks and sledges to break down a portion of the wall. The wild chatter from without told him that Quong-li had been informed of his doings. The ladder by which he had descended was hurriedly drawn up and used to bring the boss Chinaman to the top of the wall.

There, as he nervously peeped at Buck and the bull, he unloosed all the curses of the Chinese tongue. They foamed from his lips. He had sent two coolies for the police. It was murder to unloose the bull. A hundred persons would be killed by the animal. No, a thousand! I-chien! Possibly ten thousand! I-wan!

Buck waved him away. He wouldn't listen to the threats of the angry yellow man. All his thoughts were directed to the work of rescuing Dan'l Boone from his prison. His patriotism was aroused. An American bull that he had nursed when a small calf was locked up in a filthy yard, and the bull looked to him for help.

Quong disappeared from the wall. A coolie shouted the information that the sedan chair had gone off at a gallop to bring a policeman. The coolie, won over by a promised bribe, tossed a pick into the corral.

Buck attacked the wall. It was Chinese masonry and it crumbled before his vigorous blows. The bull seemed interested. He stood quite close to the cowboy and now and then he gave a low bellow as if to show his appreciation of the effort being made to release him.

Inside an hour Buck had made a hole sufficiently large for the animal to pass. through. He took from his pocket the clothesline he had stolen from the Buddhist Monastery, tied it round the horns of the beast and led him through The longhorn unloosed a great bellow of delight.

"Now" said Buck, "we must beat that Chinaman to his home. There's a lady there, Dan'l, who wants our help," and saying that he sprang upon the back of the bull and jabbed him with his heels.

Men and women working in the rice fields shrieked with fear as the galloping bull appeared on the country road. Some stood petrified with fear, while others threw down their implements and fled. Pedestrians on the road leapt over fences, calling on their gods to protect them. A startled countryside saw the parade.

The bull caught up with the sedan chair carrying Quong. The coolies dropped the handles when they heard the noise made by the hoofs of Dan'l. They took to the rice fields, leaving Quong in the center of the road. Buck waved to him as he passed at a gallop and the Chinaman hurled curses in return. A sharecropper fired a gun at Buck, but the missiles of old nails and bits of iron whistled over his head.

THE house of Quong-li occupied a commanding position in the walled town. A watching coolie saw the approach of Buck when the bull was half a mile away. He shouted the news to the Number One wife and she ordered the gates of the courtyard closed. Swiftly the news was conveyed to the town gatekeeper. As Buck rode towards the gate the fellow tried to close it, but the cowboy called on Dan'l Boone for an effort; The beast charged and the gatekeeper fled for his life.

Up the narrow winding street Buck steered the bull to the house of Quong. Now he was thrilled by the sight that met his eyes. The gateman was struggling to close the heavy gate but his efforts were made futile by the opposition of a slim girl who fought him with her fingernails and her feet. It was Fairy Lily, a Manchu wildcat as she struggled to keep a passage for the cowboy.

Buck didn't know it at the moment, but he heard the story later. In the history of the Manchu Dynasty there is a thrilling tale concerning a great Manchu general who, after the conquest of China, became the Emperor Chien-Lung. During the invasion the general's horse fell with an arrow in his heart, but the rider was unhurt. Picking himself up he jumped upon the back of a blue-skinned buffalo in a nearby field and continued the pursuit of the fleeing Chinese. This story was known to Fairy Lily, and the sight of Buck galloping towards the gate on the back of Dan'l Boone stirred all her Manchu blood. She fought the orders of the Number One wife and did it with such vigor that Buck rode in in triumph.

The girl, being the only receptionist—the others having fled to their quarters and barred the doors—the gallant cowboy did what seemed to be expected of him. He leaned down from the back of the longhorn and took Fairy Lily in his arms. She made no objection, and while they were still embracing joyously the sedan chair of Quong came through the untended gate and made the Chinaman a witness to the affectionate greeting.

The coolies carrying the chair, finding themselves so close to the bull, dropped the handles and fled, leaving Quong stranded in the courtyard. An insane Chinaman now. He cursed Buck and Fairy Lily. He ordered the cowboy to take the bull from the yard so that he could climb out of the chair, but Buck, instead of complying, moved Dan'l Boone closer to the gaudy conveyance and Quong screamed as the bull sniffed at the door, blowing foam over the occupant.

Fairy Lily whispered to Buck and retired, then the cowboy spoke to the imprisoned Chinaman. His words were quiet and carried a dash of humor: "When I rescued you from the toughs that had robbed you," he began, "you promised me one tenth of the boodle that the footpads had to give back. When I mentioned the matter to you yesterday you dodged away. Listen. If you give me this longhorn I'll call it square. What say?"

"Take heem!" screamed Quong. "Take heem queeck! Get out! You one bad mans!"

"Careful boy," said Buck. "Watch your tongue. This bull has a lot of hate packed up against you for your cruelty."

Dan'l Boone tossed his head, flinging nostrils of foam over Quong. The terrified Chinaman tried to crawl under the seat.

Buck laughed loudly, mounted the bull and rode out of the courtyard.

The whispered words of Fairy Lily directed his steps. He turned towards the gate of the town. The terror inspired by the bull gave him free passage. Scared Chinamen peeped at him from tiny windows. A policeman and three soldiers came around an angle of the crooked streets, fell over each other at the sight of Dan'l and fled at top speed. The gatekeeper was absent.

Fairly Lily had whispered of a meeting place. She had named a grove of tamarind trees immediately outside the town. Buck halted there. He gathered a bundle of green stuff for Boone, washed the dirt off the animal as he waited and kept a close eye on the house of Quong. Now he rebuked himself for leaving without the girl, but her instructions had been implicit. She had wished to collect some Manchu treasures that were in her quarters and she had ordered him forward alone. She would join him in the grove.

Sitting in the lengthening shadows of the trees he considered his actions. Were they correct? He recalled the conversation of Quong and that of the girl. Quong's purchase of Fairy Lily had taken place only a few days before Buck's arrival at the homestead. Quong had been on an opium bout in a neighboring village, so the chances were that he had not interfered with the girl during the time she had been in his house.

FAIRY LILY came when the night crept over the countryside. Breathless and excited. She had slipped from the house

without being seen. The occupants were ail upset by the happening of the afternoon. Quong had collapsed. He had been carried to his bedroom and the whole female section of the settlement was endeavoring to soothe him.

"We must get away at once!" cried the girl. "The soldiers will be after us!"

Buck was amused. "Not the ones I saw," he said. "But we'll move if you wish it."

It was dark now, but Buck lifted Fairy Lily onto the back of Dan'l Boone. He took the rope in his hand and stepped out beside them. The girl.whispered of robbers, but the cowboy laughed. "None will attack us," he said. "This bull has earned a reputation in this part of the country. You should have seen them hopping over fences and galloping through rice fields when I was riding by."

The road followed the river, and before dawn they approached a walled village. They waited till the gate was opened, then they rode in. They stopped at a small Chinese hotel and Buck demanded two rooms.

"One," whispered Fairy Lily.

"Two," said Buck. "That is for today at least. We might find a missionary around here who will marry us."

They put Dan'l Boone in a stall with a bundle of greenstuff and ate their breakfast on the bamboo-shaded terrace. Buck was delighted; Fairy Lily's joy, was immense.

After breakfast Buck hunted through the village and found an aged American missionary. He had been in China for thirty years. Yes, he should have gone home, but he bad stayed till the desire had grown so weak that the stinks around him did not trouble him. The country held him.

He listened to Buck's story. He questioned Fairy Lily. He had heard of Quong-li as a dissolute person with frightful scandals connected with his name. Had the girl any voice in the sale by which she had become the property of the Chinaman? Fairy Lily shrieked a negative. She had been sold by creditors of her father after his failure. She wept before the aged missionary. She would commit suicide if she were forced to return to the house of Quong.

The gentle old man considered the matter for a long while, then with a sigh he consented to perform the service. He blessed the pair after the ceremony. Fairy Lily, much excited, kissed his worn cheek.

"Now," said Buck, smiling down at his wife, "we can cut expenses by getting rid of the extra room. Married life is cheaper."

That afternoon they moved on. Fairy Lily had a fear of the vengeance of Quong.

IT was in a walled town some thirty li from the place where they were married that Buck started his exhibition of fancy rope throwing. It was a solution of the money problem. China was cheap, but one had to nave a little money to meet the expenses of the day.

Buck, in himself, was a curio to the country folk. He dressed in a manner that made him noticeable. He was traveling with a great horned beast the like of which they had never seen, and he did wonders with a rope. Besides, his lady was a vision of beauty that made the local women stare.

Fairy Lily, came into the show as a self-appointed treasurer. She took a great delight in passing round Buck's big hat for the coins after the performance. She coaxed and bullied the spectators. When a fat Chinaman grunted a fu shih as she held the hat under his nose she clung to him till he handed out a contribution. Buck was thrilled with her activities. Even Dan'l Boone showed an interest in the business. Washed and wearing several colored ribbons around his wide neck he walked with pride around the ring and his deep bellow had the quality of a siren in dragging the folk from the narrow streets.

Buck and Fairy Lily counted the returns in their bedroom. The mass of small cash didn't amount to a dollar in American money, but the sum thrilled them. It was sufficient to keep them for a day, and they went to sleep thinking of improvements to their show.

When morning came they moved on to the next village. It was springtime and the country looked beautiful. The annoying odors were in a way squelched by the new blossoms that tried their best to put them to rout. Passersby saluted the newly married couple. They stared at Dan'l Boone with the gay ribbons around his neck.

They ate a meal by the roadside. They were very happy. Buck assured Fairy Lily that such a day had never come into his life and she agreed it was the same with her. She whispered of her fears. The day was so glorious that she thought some terrible happening would suddenly disrupt their life.

"Nothing can, darling," cried Buck, and forgetful of the promenaders they embraced to the great joy of the simple folk who seemed to enjoy their evident happiness. A blind minstrel, led by a tiny child, stopped before the lovers and played a little tinkling tune on a wooden pipe. Fairy Lily asked him to play another, and this time she sang to it. She bought the child a cake from a traveling merchant and she gave the blind man some coins for which he blessed her.

"I am still afraid," she whispered to Buck. "It is written in the Book of Rites that one should be afraid of great happiness because the gods are jealous."

Buck laughed loudly. "Let them be jealous," he cried. "Nothing can hurt us."

That evening they gave an extraordinary performance. A very rich Chinaman begged them to give a display in his grounds, and he invited all his neighbors. He paid Buck highly for the performance and he gave an amethyst brooch as a souvenir to Fairy Lily. They returned to the small Chinese hotel drunk with joy.

THE disaster that Fairy Lily feared struck them on the following morning. The two were seated on the terrace of the hotel eating their breakfast of small rice-cakes with basins of tea, and watching the stream of hurrying folk in the narrow street. Buck had turned his head for a moment to look at a curious figure of a man dressed out in rags of different colors. When he turned back to his cakes he found beside his bowl a black marble about the size of a large walnut that was still trembling as if it had just been placed there. There was no one on the terrace but himself and Fairy Lily, and the. presence of the black object gave him a strange feeling.

Fairy Lily had not seen the marble, but Buck drew her attention to it with a gesture of his hand.

The effect upon her startled him. She dropped the basin that she was carrying to her lips and unloosed a scream of fear. She sprang from her chair and stumbled back from the table as if she thought the black marble would suddenly open and produce a cobra. Buck was thunderstruck by her actions.

"What is it?" he cried. "What is wrong?"

Terror showed on the face of the woman. Her actions suggested that she was on the verge of fainting. Buck hurriedly grasped her and carried her to a bamboo settee.

"Tell me!" he cried. "Why has it frightened you?"

Her whispered words had a coating of horror. "He, Quong, has put the Black Dragons on our track!"

Buck, leaning over his bride, cried out questions. Who were the Black Dragons and why did Fairy Lily fear them?

With terror-dried lips she stammered out words. "They drive people mad," she gasped. "Persons that they are paid to torment! They never escape them!'

Buck was puzzled. His ears drank in her choked words, words that were hobbled by dread. He lowered his head and listened to sentences that were moulded by despair. The Black Dragons, according to Fairy Lily, was an organization of torturers. When hired by a wealthy man they followed the person who had incurred the enmity of the payer and made his life a little hell by placing black marbles near him day and night in such a mysterious manner that the tortured one became insane by their unexplainable tricks,

"I'll break their necks if I catch them!" growled Buck.

"But—but you'll never see them!" panted Fairy Lily. "They have never been seen! Never!"

The boy who had served their breakfast came onto the terrace at that moment and Buck hailed him. Angrily he demanded if the youngster knew anything of the black, marble that had been put upon the breakfast table.

The boy approached fearfully. He took one glance at the marble, unloosed a yell of great terror and fled. The puzzled cowboy heard shouts and cries in the service department as the find was reported. Then came the slippered rush of the proprietor and half a dozen employees.

At a trot the fat boss of the outfit approached the table, stared for an instant at the marble, then cried out an order. An order to Buck. It was a howl of dread, lacking all the politeness that he had shown up to that moment. It was backed up with abuse and threats. From the stream of insulting words Buck understood that he and Fairy Lily were to get off the hotel premises in the quickest possible time and never return.

Buck attempted to argue with the fellow, but the man had become crazed. They were to leave within the minute. The cowboy, standing a yard over the insane yellow man, made a motion as if he would wipe the floor with the landlord, but Fairy Lily intervened. "No, no, no!" she cried. "He is right! He is in danger if he lets us stay! Let us go!"

They left, Buck leading Dan'l Boone, the proprietor and his help urging them forward, the street crowd listening open-mouthed to the denunciations.

ON the highway Buck questioned Fairy lily. She knew little, and what she did know was told with quivering lips and a voice that was unsteady. Buck heard of a society of devils that only China, the home of trickery, could produce. For a heavy fee they undertook to torment a person cunningly and continuously. Tirelessly they followed their victim, and by the mysterious arrival of a marble or a coin they played on his nerves till he was distracted. Their power was so great that no one wished to have the tormented one in their house or even to be seen in his company lest they incur the wrath of the society, and in many cases the only escape was suicide.

Buck listened to her words. It seemed un-American to his mind, yet his imagination could conceive the torment brought about by the deviltry of the Black Dragons. Fairy Lily knew nothing of their whereabouts. From somewhere or other a secret agent would come from the society to a rich man who had a grievance against another. This agent collected the money and the torture began.

"And you think that Quong-li is responsible for this?" asked Buck.

"Who else?" demanded Fairy Lily.

"That's all," said Buck. "Don't worry any more. Let's forget it for the moment."

The bright sunshine and the amusing scenes of the road put the incident of the breakfast table out of their minds. By midday they had forgotten it completely. They were young and in love.

They had traveled some eight li, about three and a half miles from the hotel out of which they had been evicted when they came to a nice fruit shop on the road. Fairy Lily suggested that they should eat their lunch in the open like the previous day, and Buck decided to purchase an early melon as a dessert. They put it in a bag strapped to the back of Dan'l Boone, and they went on, gathering other commodities for their picnic. They had money from the performance of the previous evening and they bought candied fruit, tiny cakes and noodles from the barrows of wandering cooks.

About two li from the fruit stall where they had purchased the melon they found a stunted oak that acted as guard to a poppy, field and there they halted for their meal. Buck was gay and he tried his best to lift the sadness from the mind of Fairy Lily. He joked about the different packages of food that they had collected and he forced her to eat when she showed a poor appetite.

"Now we come to the treasure," he said, picking up the early melon.

He sliced it in two with a quick stroke, then he dropped the two halves with a muttered curse. From the interior of ripe pulp there rolled a black marble similar to the one that had appeared mysteriously on their breakfast table!

For a full ten minutes they stared at the thing in silence. Fairy Lily was too terrified to speak, Buck was too angry. At last the cowboy got to his feet. "We are going back to that fruit stall," he said. "We must get to the bottom of this business."

He turned Dan'l Boone and lifted Fairy Lily to the animal's back. He led the beast, silent, his jaw set. The trickery maddened him. He longed for something or somebody upon whom he could put his strong hands.

He wondered if such a game could be played in the United States. He thought not. The country was young and clean in comparison with China. It required an old diseased country to hatch out the devilish scheme which was tormenting him and Fairy Lily. Filled with a great anger they reached the stall where they had purchased the melon.

Quietly Buck talked. Did the melon man remember him? He had bought a melon there some hours ago? The Chinaman said he remembered the honorable stranger perfectly. Was there anything wrong with the purchase?

Buck took the black marble from his pocket and thrust it before the face of the fellow.

The man gave a yell that stopped all the pedestrians on the road for a full mile. He endeavored to run, but Buck caught his loose jacket and held him. He wished to know from whom he had bought the melon and when.

The poor stuttering wretch was so terrified by the sight of the marble that he couldn't answer. His wife came to his aid. She explained that they had bought the piece from a traveling hawker an hour before they had sold it to Buck. She didn't know the man. Neither she nor her husband had touched the fruit. They had simply placed it on the stand and it had rested there till the honorable stranger had purchased it.

Buck let the fellow go. He was greatly puzzled. He had found no sign that the melon had been "tapped," and if it had been monkeyed with by the itinerant hawker how did the man know that he, Buck, would be the purchaser?

Fairy Lily took him by the arm. "Let us go on," she whispered. "We will get out of their reach."

"I am thinking of returning to Quong's house," growled the cowboy. "I have an inclination to break, his neck!"

"No, no!" cried Fairy Lily. "He is rich. He. would have you put in prison. No, we must get far away from him!"

A beggar who looked as if he might be a hundred years of age hobbled along with Buck and Fairy Lily, his claw outstretched, his whining voice demanding alms. Buck, who could think of nothing but the demons who were tormenting him, looked at the wrinkled face of the beggar and put a soft question; Did the old one know anything concerning a crowd of bad people who were known as the Black Dragons?

The effect of the question on the ancient was extraordinary. Up to that moment he had great difficulty in dragging his legs through the dust at a pace that kept up with the easy walk of Buck, but the query electrified him. He bolted forward at a speed that would do credit to a youth of twenty. His begging pouch fell from his shoulders but he disregarded it, although other travelers, with loud shouts, drew his attention to his loss. He burst through a fence of osier bushes by the roadside, threshed through the water in a rice field and disappeared in a tree clump on the far side. The people on the road, who had watched the flight, glanced queerly at the bull and Buck and Fairy Lily, then with much strange jabbering they went on their way.

THEY gave no performance that evening in the village they entered at sundown. They were too upset. They stayed at a Chinese inn, a Ko-chan of the lowest type, indescribably filthy and uncomfortable. They ate a dreadful meal of pork and bean curds and went to their room.

Before retiring Buck locked the door and also the small window, then he made a minute search of the room. There was little furniture—the bed, a rickety chair and a strip of matting on the floor. The latter the cowboy took up and shook till Fairy Lily protested against the dust that he raised.

"I'm in a temper," he said. "If I catch one of those devils there's going to be a murder."

Fairy Lily tried to soothe her angry husband, but the events of the day had roused his Indian blood. He longed for a tangible enemy that he could throttle.

He lay awake through long hours of darkness, listening to the clamor of gamblers in the lower rooms of the inn, and it was near dawn when he fell asleep.

He woke with a start. It was plain daylight. Fairy Lily was sleeping peacefully. Buck lay for a few minutes trying to puzzle out what had roused him. Failing to find an answer he rose and, without disturbing his wife, he started to dress. He glanced at the door and the window as he sat on the rickety chair. They seemed to be in the state he had left them on the previous evening, their old-fashioned locks, plain to his eyes, were seemingly untouched.

He put on his shirt and trousers, then his socks. It was then that he noticed that a decorated headstall he had bought for Dan'l Boone on the route had slipped from a peg to the floor. Wondering, but finally dismissing the thought that it had been touched by an intruder, he reached down and picked up a shoe. He tilted it to place it on his right foot when, to his great amazement and sudden fury, _a black marble rolled from the shoe, dropped to the floor and raced across the room!^

Buck's cry of anger awakened Fairy Lily. She sat up in bed and watched the marble with frightened eyes till it had stopped rolling.

Neither spoke. Buck put on his shoes, laced them, walked across the room and picked up the marble. It was identical with the two others that had been mysteriously thrust under his notice. He sat down on the bed beside the woman.

Fairy Lily started to speak. "The only way to stop the persecution is by my death," she said quietly. "Then you will be free. I have brought trouble on you. Great trouble. I asked your assistance and you gave it, never thinking of the torture that would come to you. Now I must go to the place of my gods and leave you free."

Her words infuriated Buck. Angrily he, told her that she was talking nonsense, then, wishing to find someone on whom he could vent his temper, he dashed from the room and found the landlord of the inn. Buck asserted that his room had been entered during the night, but the fat owner was indignant. Such a thing was impossible he cried. Rumors had been circulated regarding the presence of robbers in the town, and he, the landlord, had hired a special guard who had been promenading around the inn all that night. What had been stolen from the honorable stranger?

Buck forgot at that moment his unfortunate dealings with a former landlord. In his anger he took the marble from his pocket and thrust it at the fat man. He shouted his reply. Nothing had been stolen, but the thief had left him a little present in the shape of a black marble.

The owner of the inn took one glance at the object, staggered against the flimsy wall, slipped to his knees and lay gurgling on the mat.

Buck tried to pick the fellow up, but the Chinaman shrieked protests. He didn't wish his lodger to touch him. The cowboy, to him, was unclean. He must get out of the inn at once or he would contaminate the establishment.

The words did not please Buck. To think that he would soil the filthy hovel made him furious. He stooped and slapped the fat greasy cheeks of the hotel man and then the smelly warren became alive. The shouts of the fellow brought his servants and a score of boarders. They fell upon Buck, burying him under their sweaty bodies, screeching like a million fiends.

FAIRY LILY heard the riot and came out of the room to inquire. The hotel man had been dragged out of the mass of bodies and was sitting up on the landing. He saw Fairy Lily and shrieked an order. His wolves sprang upon her, carried her bodily through the narrow passages and tossed her carelessly into the roadway.

Buck, fighting a dozen or more, did not see her removal, but when he finally fought himself free and found that his wife had been thrown out he gave a very good impersonation of the taking of a Japanese island. He tore part of a handrail from the stairs and using it as a club he swung it at the heads of his assailants. They fled before him. Up and down the passages he pursued them and he paused only when Fairy Lily cried out to him from the road. Gallantly she had run to the rear of the inn and had brought Dan'l Boone out of the stable so that they could retreat when the opportunity occurred.

"Quick! Quick!" she cried. "They will bring the police!"

Buck took her advice. He lifted her onto the back of Dan'l Boone and started the bull at a lively trot towards the open country.

They were certain that the innkeeper would make charges against them, charges that would be upheld by the court and which would bring heavy penalties. A dense wood covered a stretch of ground between them and the river. They found their way to the darkest spot in the century-old trees and waited. Fairy Lily was unhurt, but Buck had a thousand scratches on face and hands, and bruises innumerable. When Fairy Lily wept, he laughed and tried to cheer her up,

"It's nothing," [ he said. "Just little scratches. I've had digs from bayonets, hundreds of them."

But her tears flowed without ceasing. She made accusations against herself. She had brought Buck into troubles unending, troubles from which they would never escape.

"Yes, we will," growled Buck. "I've decided on a way."

"What is it?" asked the woman.

"How far do you think we are from the house of Quong?" he asked.

"About four days' march," whispered Fairy Lily.

"Well, we will stay here till night comes down then we will start for his place. I'm finished with retreating. Now I'm going to attack."

"What—what will you do?"

"I'm going to kill him," said Buck joyously. "I'm going to choke the life out of his yellow carcass and sling it out on the road."

Fairy Lily became hysterical. She was against the proposition. Buck would have his head chopped off if he lifted a hand against Quong-li. The Chinaman was a power in the land and Buck had no right to touch him.

"I have a thousand rights!" cried Buck. "What right has that old ruffian to buy you and bring you into his house for—for immoral purposes?"

"The law—the law thinks he has," sobbed Fairy Lily. "It is done all over China.

"Well, Quong won't do it again after I finish with him!" cried the angry Buck. I'll teach him that one wife is all he has a right to."

Fairy Lily's excitement and tears brought sleep to her. Buck stood on guard. The wood had a haunted appearance which he bought might keep his enemies at bay, and when the night came no Chinaman would be abroad. He felt happy as he considered the plan he had formed.

BUCK must have dozed when the dusk fell. He woke with a start. He looked around for his wife. Fairy Lily had disappeared from the spot where she had been resting.

A wild fear gripped him. He stood up and softly called her name. There was no answer. He felt his way to the spot where Dan'l Boone was standing. The bull greeted him with a friendly bellow, and Buck, seized with terror, touched the ear of the animal in answer. A feeling of horror gripped him as he did so. His hand had touched the little net bag of Fairy Lily—the bag in which she carried a few Manchu treasures. It was tied to the horn of the bull.

The icy hand of terror gripped the heart of Buck. While he stood transfixed one sound alone came to his ears. The noise of the night wind in the trees was stilled, the chatter of night birds and the whine of insects were wiped out. He heard only one terrifying sound—the far-off whisper of the Yangtze as it fought its way down to the sea.

Buck knew. A blessed omniscience came to him. A wisdom that was like a searing flame. Fairy Lily had gone to the river. Gone to the river to wipe out her life, lest the preservation of it would bring the head of Buck under the axe of the executioner!

Of the hours that followed Buck remembered nothing. An insanity possessed him and when it passed all the agony of the moment was sponged from his mind.

But the moments—the absolute moments after the roar of the river came to him, bred happenings that couldn't be recorded. No tracing of them could be stencilled on a human brain. Not as Buck saw them. Snaky lianas clutched at his throat and tried to strangle him. Great trees, a hundred times bigger than the old trees of the wood, were flung up in his path to block his running feet. But hope came to him. A great hope. The roar of the river became louder. Louder. It was deafening. It filled his ears with a sound that put a force into his legs. He marveled at it. He never knew that sound could be turned into force in a way that made him leap over great obstacles as if they didn't exist.

A Chinese moon came out for an instant and flashed the river bank before him. On a rocky point he saw her. Silver white and shapely. Face to the river. Bowing to it. Making sweet obeisance to her executioner that would save Buck from the prosaic axe.

Buck screamed out to her but the river swamped his voice. The river wanted her. Wanted her beauty and the spirit of love hidden in her heart.

Now Buck was close. Running along the strip of rock that bored into the stream. She was plain to him. Naked. She was making her last bow to the water. She was moving towards it.

Buck hurled himself forward, arms flung out to reach her slim ankles. Blinded with tears he waited for the strong fingers to tell him the news, but it was the touch of her flesh that cried the joyful intelligence to him. He had pulled her down on the rock when she was a foot from the angry stream!

Not leaving go of her he crept up beside her. "Why? Why?" he gasped.

"Let me go!" she breathed. "A body given to the gods will save you."

"I'll give the one the old gods want," growled Buck. "I'll give them Quong's. It's fatter and less beautiful than yours and no sweetheart wants it."

Leaning on each other they fought their way back to Dan'l Boone. He received them with a soft bellow of joy.

BUCK and Fairy Lily were four days on the march to the village of Quong-li. They avoided the places where they had trouble, but they had a joyous reunion at the village where they were married. The old missionary was delighted to see them, but he grew sad when Buck told him of the damnable persecution they had suffered.

"And why, my son, are you going back to the place where this bad man lives?" he asked.

Fairy Lily was for the moment in the mission garden and out of hearing. "I am going to kill him," said Buck softly. "Yes, with my hands."

The missionary implored him to consider his action, but it was no use. The Indian blood was hot for revenge. They left in the afternoon, heading for the village of Quong-li, Buck's face set and drawn, Fairy Lily weeping and praying to her particular gods.

Near the big gate of the village they found an unusual excitement. A stream of persons passed in and out of the cluster. Buck, who had thought of leaving Fairy Lily at the tamarind grove where he had waited for her on the night of her elopement* asked a coolie for the reason of the flurry and the wild jabbering.

The coolie wiped tears from his eyes before he answered. Didn't the honorable stranger know the sad news? The Honorable Quong-li, the richest and most distinguished man in the village was dying!

Buck unloosed a roar of laughter, a mad wild roar that astonished the crowd. He ran to inform Fairy Lily. Quong was on his death bed. Her prayers to her little gods had been answered.

Fairy Lily dropped on her knees, her slim body shaken with joy. Buck cried out to her to await his coming and he joined the crowd that swept up the narrow street towards the gate of Quong's house. All kinds of persons who were interested in the death. Relatives, friends, Chinese priests, silk merchants, flower sellers, and weeping beggars, hoping their faked tears would bring a few coins from the throng.

There was no control. No guard at the gate. Buck was unnoticed. He was carried by the compact mob across the big courtyard where he had lassoed the coolie only seven days before. Jammed between two Buddhist priests he was swept into the very bedroom of Quong.

He was close to the bed. To the huge bed covered with eiderdown quilts on which the dying man rested. It was uncanny. The man to whose side he had been traveling fast for four days with the idea of murder in his mind, was there before him, slipping quietly into another world. He felt a little stunned.

Close to the bed, hedged in by a protective barrier of flowers, stood the Number One wife and the three concubines, all looking as if they too were passing from the world. They wept in a blind automatic manner and their sobs blended with the mutterings of the priests and the noise of gongs that were pounding slowly. The odors of incense were overpowering. Buck thought that Quong must possess a strong constitution to stand up to the stench.

PRESENTLY there was a disturbing interruption. A tall vigorous Chinaman, possessed of the manner of a man of affairs, fought his way to the bedside. He upset the strange atmosphere of the big chamber. In a loud voice he made a demand of the dying man. A demand for money.

The room listened. The muttering priests were silent, the gong-beaters' hands were paralyzed. All wished to hear what the interrupter was saying.

Buck caught a word. Another. He thrilled. He pushed a mourner roughly out of his: way. The big man was demanding money for a debt Quong-li had contracted. He asserted loudly that it wouldn't be paid by Quong's heirs. Why? Because it was an illegal debt and the courts wouldn't recognize it.

Quong-li opened his eyes. The big man was continuing his loud demands. Payment must be made before Quong passed. He stated the law. It was a secret debt with no papers to warrant a demand.

Quong's eyes fell on Buck. A look of low cunning passed-over his face. He lifted a finger and drew the attention of the big debt collector to Buck, then he spoke clearly. "Heem payee you," he said. "Payee you velly well." He closed his eyes. They w:ere his last words.

A great joy came to Buck as he met the questioning eyes of the debt collector. A happiness that he had seldom known rushed through his body. He knew the nature of the debt that Quong had contracted! It concerned himself! Concerned his wife, the slim and beautiful Fairy Lily! The money had been spent on them both! Spent for torture!

Buck nodded to the collector. He made a motion to the fellow to follow him and he fought his way roughly through the packed crowd. The debt collector followed eagerly. He looked immensely pleased. Quong was dead, but a new man that he had never seen, was willing to pay the debt.

Buck remembered the path to the room he had occupied during his short stay in the house. He led the way, the big man on his heels. They entered, and Buck shut the door.

He asked the collector a question. He wished to make sure of the debt before he paid it. Was he right in assuming that it concerned a society called the Black Dragons? If it was so, the payment would be immediate.

The other choked in his hurry to get out his words. Yes, yes. It was a debt to the Black Dragons. They had acted for Quong in the matter of plaguing a runaway concubine and the man she had run away with. Quong had promised immediate payment but his illness had prevented it.

"Then," said Buck, "you'll get it now!" And with the words he drove his right fist into the big mouth of the other. "In full," he added, bringing up his left in an upper-cut that sent the big man reeling across the room.

The Chinaman was not a pugilist but he was a judo expert. And he had courage. Lots of it.

He picked himself up and rushed. Buck slipped slightly on a rug as the fellow came in. The Chinaman got a grip on his right leg and paralyzed it. The pain was maddening. It ran like a red-hot wire through the cowboy's body, and for the moment he was at the attacker's mercy.

WITH a tremendous effort he broke the grip that the man had on a muscle of his leg. He slammed his two fists into the yellow face, brought up his left knee when the fellow again felt for his leg-grip and drove it into his stomach. Words dashed through his mind. Who was he fighting for? Who had been tortured by the unclean devils who received money for their dirty-work. "Fairy Lily!" he shouted, as one of his straight body punches knocked the wind out of the collector. "Fairy Lily!" he cried and rocked him with a right swing that would have stopped a charging elephant.

Now he had the debt collector at his mercy. He was too groggy to use the tricks that he was a master of. He staggered around the room, and Buck hit him at will. He fell, picked himself up, rushed and was stopped with a punch in the eyes that blinded him. Down again, but up once more to receive a knockout punch that laid him flat on the floor.

He didn't move, and looked as if he had no intention of taking any exercise for a long while. Buck, standing over him, searched in his own pocket till he found one of the black marbles that had tortured him and Fairy Lily. He placed it in the Chinaman's open hand and closed his fingers around it. "A gift from a very sweet lady," he murmured, but the debt collector didn't hear him. He was in the land of dreams.

Buck went out and closed the door. He walked down the narrow street to the town gate and out to the spot where he had left Fairy Lily. He was happy, intensely so.

He had definite plans which he explained to his girl wife. They left immediately for the village where the old missionary lived, and to the great delight of the holy man they made him a present of Dan'l Boone.

"A fellow American who will make you think of home," said Buck. "His name is Daniel Boone."

"The Mighty Hunter!" cried the missionary. "I know he will make me think of America. I came from Reading, Pennsylvania, where Boone saw the light of day. I thank you for the gift."

They said good-bye to the old man, who gave them his blessing; then the pair walked towards the river. Buck spoke. "Now," he said, "we will get a cheap junk passage to Shanghai and then we will try to find a steamer that will take us to a country where there are no stenches."

"Oh, Buck!" cried Fairy Lily. "Is there—is there such a place?"

"Well, there might be a teeny-weeny odor on a very hot day," he admitted, "but any Chinese smell could whip a thousand of America's strongest odors and think it child's play."

"And—and will they let me in?" murmured the girl.

"We'll try," he said. "My old general will speak for me. I've got a bunch of medals I won in this war and he won't forget me. They're great people, sweetheart! Come on for Texas!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.