RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

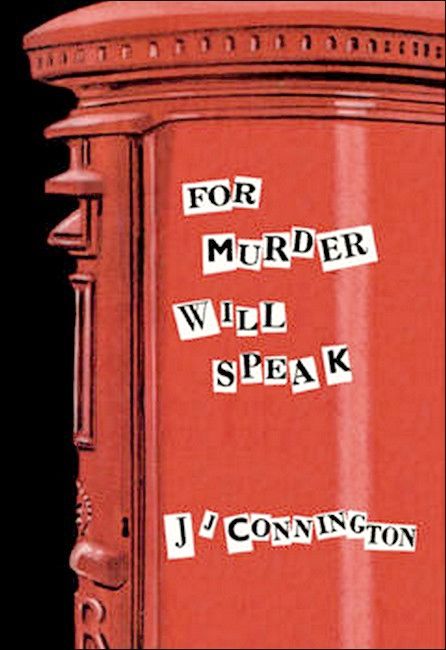

"For Murder Will Speak," Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1938

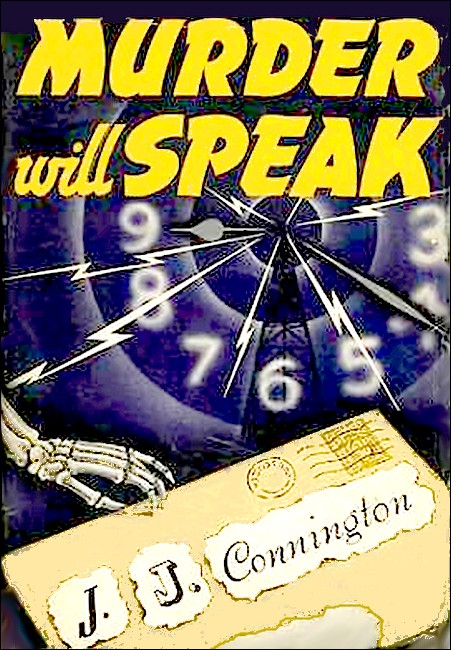

"Murder Will Speak," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1930

"For Murder Will Speak" is a classic Golden Age detective novel featuring Chief Constable Sir Clinton Driffield, who investigates the death of Hyson, a manipulative and self-serving man who seizes control of his office after his employer falls ill. His demise raises the question: Was it suicide or murder? The investigation is complicated by the recent suicide of Mrs. Telford and a rash of poison-pen letters circulating in the community, suggesting a deeper conspiracy.

SITTING at his absent employer's desk, the chief clerk brought the telephone nearer to hand and dialled a number.

"Mr. Hyson speaking," he explained. "Can I speak to the nurse for a moment, please? What's her name? Spencer? Thanks."

After a little delay, he heard a fresh voice.

"Mr. Hyson? This is Nurse Spencer speaking. I suppose you want to know how Mr. Lockhurst's going on?"

"Sorry to trouble you, Nurse. Naturally we're anxious about him."

"He's doing very well," Nurse Spencer assured him. "There's been no recurrence of pain since the first attack, not so much as a twinge. He can breathe quite easily. Did Dr. Willoughby tell you about the electrocardiogram? It's quite satisfactory."

"No likelihood of a second attack, is there?"

"Well..." Nurse Spencer's tone was cautious. "You can't predict definitely, in cases of this sort. But so far as one can see, there aren't any grounds for expecting further trouble at the moment. He seems to have stood the shock very well. His pulse is all right and his blood-pressure isn't much off normal."

"Suppose you're forbidding him to do much?"

"Oh, well, he can read if he wants to; and perhaps they'll let him smoke in moderation after a day or two if he goes on well. He's a very good patient: does exactly as he's told and doesn't get fretful."

"Before I forget," interrupted Hyson, "what's the trouble called? Clients have rung up to ask for him. As well to have the scientific name to give them. I said 'heart trouble' to one man, and he wanted to know 'What kind of heart trouble?' I didn't know one had assorted kinds of heart attacks."

"You can call it coronary thrombosis," said the nurse, taking pains to speak distinctly. "Shall I spell it for you?"

"Cor-on-ar-y throm-bos-is," repeated Hyson syllabically. "No, don't trouble to spell it, Nurse. Got it right, I think."

He made a jotting of the name on a piece of paper before him and then continued:

"What is it, in plainer English?"

"His coronary artery has got blocked, somehow, and that reduces the supply of oxygen to the heart muscle."

"Thanks. One lives and learns. What's the treatment?"

"Complete rest, to give the blood stream a chance of finding fresh channels to the heart."

"Complete rest for how long?" demanded Hyson, with a certain eagerness in his tone.

"Twelve weeks, probably, to be on the safe side," Nurse Spencer exclaimed. "Twelve weeks in bed, I mean. After that, he'll probably be allowed to get up and sit about. But he won't be fit for much, after lying up for three months. He'll have to go very cautiously once he gets out of bed again. Especially in the matter of going up and down stairs. That tries the heart more than you'd suppose."

Hyson reflected that the office was on the second floor and that there was no lift in the building. For some reason, the idea seemed to give him satisfaction.

"Three months, then, or perhaps four?" he commented. "Well, we shall carry on here. Any chance of seeing him, if I came up to the house?"

"You'd better ask Dr. Willoughby. But it would need to be only a friendly call, Mr. Hyson. He mustn't be worried by business affairs just now. You understand that, don't you? Rest and quiet, physically and mentally, are what he must have at present, if he's to get well quickly and have no set-backs."

"I'll ring up the doctor and get his permission."

"That would be the best thing," the nurse agreed.

"You don't mind my ringing up to ask for him once a day for the next few days?"

"Not at all. Is that all I can do for you? Then good-bye."

"Good-bye," echoed Hyson as he hung up his receiver.

He leaned back in his chair and reflected upon what he had heard. Three months in bed, then another month, say, to pull himself together and after that it might be a week or two anyway before he could face those long flights of stairs up to the office. That meant a free hand for the best part of five months. Well, it had just come in the nick of time, Hyson mused. A nervous man might have shivered at the thought of peril escaped, but Hyson was of tougher fibre. Pity for his employer never crossed his mind.

"A damned good thing he didn't peter out in that attack, though," he reflected. "That would have meant auditors rushing in...."

As things stood, he felt himself on velvet. The old bird couldn't discuss business at present. He'd leave everything to Hyson and Hyson resolved to see that business was postponed as long as possible. Old Lockhurst was a nervous beggar. He'd follow doctor's orders to the letter. If he showed any inquisitiveness at all—which was unlikely—a hint dropped to Willoughby would make sure of keeping him quiet. Four months sure, five possibly. Time to turn round in, at any rate.

Well, the first thing to do was to put that fellow Forbury in his place. Hyson had no definite instructions from his employer, but that did not trouble him. One assumed these things; and if anyone ventured to ask an awkward question, one simply stared at him in stony silence for half a minute and then gave him an order. Forbury was getting on in years; he had a wife and three kids depending on him. He'd never dare to make any real trouble. Still, he had to be dealt with, and the sooner the better, before he had time to think.

Three white studs were let into the surface of the desk, each flanked by its ivorine label. Lockhurst had a mania for system in minor office affairs, Hyson reflected. Apparently he mistook it for efficiency; and yet when Hyson had pressed him to install that Moon-Hopkins machine he had hemmed and hawed and put off a decision. Worse still, he had asked Forbury's opinion about it. And of course Forbury had scented trouble; for if Olive Lyndoch took over the bookkeeping machine, Forbury would cease to be necessary. He had seen the sack in the offing and had opposed the scheme, tooth and nail; and despite all the talk about system and efficiency, old Lockhurst had dropped the notion. Olive had lost the chance of a rise in her screw, and that hadn't made her love Forbury any better.

He examined the three little ivorine plates. HYSON. Well, Hyson was at the other end of the wire now, so that button would be out of use for a while. FORBURY. Forbury would have to jump as usual when his bell rang, a bit quicker than before, perhaps. TYPISTS. One short ring for Olive Lyndoch; two short rings for Effie Hinkley; and three short rings for this new girl—what was her name?—Kitty... Kitty Nevern, that was it. A pretty little piece, with neat hips and nice hands. No engagement ring. Might be worth asking her out to dinner shortly. She'd be glad enough to come, by the look of her. Not like Effie Hinkley. "Yes, Mr. Hyson, I like dinners, but I don't care for dessert. Eve lost an estate by her taste in fruit, they say." A cool little brat, Effie. She'd wait for a while before she got another invitation, he could promise her. And, finally, one long ring for the office-boy. That was the really sound bit in old Lockhurst's bell-system. That long ring always made young Cadbury jump; it sounded bad-tempered.

"And now for Forbury," Hyson decided, putting his finger on the bell-button.

Forbury seemed in no haste to answer the summons. A full three minutes and more passed before he had made his appearance. Hyson looked him over critically, taking in one by one the familiar points: the shabby office coat frayed at one sleeve, the old-fashioned collar which should have been replaced yesterday, the lined face with its loose mouth. The fellow didn't even know what to do with his hands when they were empty, he noted contemptuously. Efficiency! No wonder he opposed the introduction of labour-saving devices. Hadn't the brains to understand them, apart from everything else. All he was fit for was to jog along between well-known rails, like the extinct tramway horse. A uxorious fellow, too. Always spoke about "the wife" as if he possessed a unique specimen. Hyson had a wife of his own, but she was not the only woman in whom he was interested. He despised Forbury as he would have despised a man who dined invariably on chops.

On his side, Forbury was examining his superior covertly. He distrusted Hyson, and he had his private grievance against him. When the old head clerk had died, a few years back, Forbury had looked on the succession as a certainty. He and "the wife" had made all sorts of happy little plans based on the coming rise in salary. They had spent evening after evening building castles in the air. "And we'll be able to afford so-and-so," they had pointed out to each other, as fresh possibilities occurred to their simple minds. And then the blow had fallen. Old Lockhurst had a cousin who knew a man who knew young Hyson. Influence had carried the day, and Forbury had been passed over, with a ten-pound rise to sugar the pill. All the pretty visions vanished. It was "the wife's" disappointment that hurt Forbury most. He could still remember her face when he had gone home to blurt out the bad news.

And so this young brute—for thirty-seven seemed young to Forbury—this young brute had stepped over his head, right into the chief clerkship. A superior young sweep, he was, with his abrupt talk and his contemptuous airs, as if one wasn't good enough to work alongside of him in the same office. And, another bitter pill, he didn't need the money. He had a private income, Forbury had learned. Just an amateur, as one might say, taking the bread from the mouths of people who needed it. He lived in a nice big villa out in the best suburb, with a man coming once a week to look after the garden; while Forbury, who had a passion for flowers, had to make shift with a patch of ground ten yards by twenty, where nothing would grow.

The old chief clerk had been an approachable kind of man, drawn from the same social stratum as Forbury himself. But no one could get on good terms with this Hyson, with his freezing comments and his superior clothes. Time and again he'd passed Forbury in the street without so much as a look in his direction. Not good enough for him, outside the office, apparently. But he could be polite enough to the typists, Forbury had observed. He'd never noticed anything that one could take hold of between Hyson and Olive Lyndoch; but in the recesses of his respectable little soul he had a faint discomfort when he thought about those two. There was something, he felt, that "wasn't quite nice" in their relations, though he shrank from putting a name to it on the evidence he had.

"Ah, Forbury," Hyson said, as if he had at last realised that Forbury had appeared in the room. "Mr. Lockhurst won't be back at work for some months. I'm carrying on in his place. You'll keep to your own work. Miss Lyndoch and I between us will take over Mr. Lockhurst's share. I'll interview clients, when it's necessary."

Forbury, eager to see offence, read into this that clients would hardly care for his appearance and accent.

"If Mr. Lockhurst wishes it that way, of course..." he said hesitatingly.

"It's settled," Hyson stated in a tone of finality.

"I could take over the private ledger, if that would be any help," Forbury suggested.

But here he blundered in tact. The private ledger, by office tradition, was in the charge of the chief clerk alone. No one else had even access to it. There was no reason in the matter; it was purely a matter of office etiquette: but Hyson had no intention of allowing one of the symbols of his seniority to slip from his hands, even temporarily.

"No," he said, icily, "I won't trouble you to do that. You'll just go on as you've been doing. Is that clear? Very good."

Forbury heard the dismissal tone in the last phrase, but he braced himself to ignore it.

"How is Mr. Lockhurst keeping?" he asked, to show that he could stay there if he chose.

"Not in immediate danger," Hyson said curtly. "It's coronary thrombosis."

"What's that?" inquired Forbury, striving to assert himself by prolonging the interview.

"Artery in the heart's blocked. Ask a doctor if you want more," Hyson replied, picking up a document from the desk and becoming engrossed in it so as to give Forbury no further chance of delaying his exit. Then as an idea crossed his mind he added, "No use your calling at the house. He isn't allowed to talk business."

"Meaning that he wouldn't want to see me socially," Forbury interpreted to himself, as he turned to the door. "Well, likely he wouldn't. But sick-visiting's different."

Hyson put his finger on the TYPISTS button and pressed it thrice. It was getting near post-time and he had the day's letters to check. Kitty Nevern did not keep him waiting as long as Forbury had done. In a few seconds she came in, light-footed, with a sheaf of documents in her hand, which she laid on the desk before Hyson. She was a girl who smiled easily, and as she put the papers down she favoured him with a smile which brought out her dimples.

"I'm taking over Mr. Lockhurst's work while he's ill," Hyson explained with an answering smile and an appraising glance at the girl's figure.

He picked up the letters in turn, glanced through them, and signed "Allan Lockhurst, per pro. Oswald Hyson" to each before putting it aside. As he did so, it occurred to him that it might be as well to get a power of attorney from Lockhurst, if it could be managed. Not necessary for routine business, of course. Have to fake up some excuse about being able to act in emergency. It might be a handy thing to have. Best look up the point, before broaching it to the old man.

He signed two or three more letters, then something in the next one caught his eye and he glanced up sharply at the typist.

"What's this? When I dictated this letter about these American common shares, I couldn't remember the exact number of shares we held. How did you manage to fill in the figures?"

Kitty looked a little flurried as she replied:

"I asked Miss Lyndoch, Mr. Hyson. She gave me the number of those that are to be sent up to London for marking."

"Indeed?" commented Hyson with a frown.

His finger sought the TYPISTS button on the desk and pressed it once. This was the sort of thing he had no intention of passing over.

Olive Lyndoch was a tall handsome girl of twenty-five, with features tending to the aquiline type. Kitty Nevern was younger and prettier, but the elder girl's face had more character in it and she had a feline gracefulness of movement which Kitty lacked.

"Yes, Mr. Hyson?"

"Miss Nevern tells me you gave her the number of our holding in these American common shares. Where did you get it?"

"In the private ledger. You left it lying on the desk there when you went out, and I thought it would save time if I gave Miss Nevern the figure instead of waiting till you came back."

Hyson frowned at the explanation.

"You're not supposed to have access to the private ledger. You know that. I'm the only person to deal with it," he said sharply. "As a matter of fact, you've given Miss Nevern the wrong figure. These shares were bought in two lots, and you've given her the figure for one block only. Don't do that kind of thing again, please. You'll have to retype that letter, Miss Nevern."

He gave a nod of dismissal to Olive Lyndoch. For a moment she seemed inclined to argue the point further. Then, evidently recognising that she was definitely in the wrong, she made a non-committal gesture and left the room. Hyson caught her expression as she turned to go.

"She didn't like that," he reflected. "Be a lesson to her. She needn't think she can do as she likes with me. I'll make it square with her this evening. But she won't get away with it."

He turned back to Kitty; and, seeing her looking uncomfortable at her position, he reassured her with a smile which showed a gleam of white teeth.

"Might have been a bad slip, that," he explained. "Come to me always in cases of that kind, Miss Nevern. No harm done this time, but you see what might happen. I'm not blaming you in the matter."

He read and signed the remaining letters without comment. Then, as he handed them back to her, a thought seemed to strike him.

"By the way, Miss Nevern, I'd better make a note of your address. One never knows when one may need it."

Kitty Nevern gave him a curious glance as she replied:

"It's care of Yately, 144 Roan Street."

"You're not living with your people, then? In rooms, eh?"

Kitty nodded in reply, thinking how much alike her employers seemed to be.

"Don't you find it a bit dull in the evenings? What do you do with yourself?"

Kitty shrugged her shoulders, a movement she had copied from her favourite star.

"Oh, go to the pictures sometimes, or go for a walk if the weather isn't too bad, or fill in the time somehow."

She had sized up Hyson from the way he looked at her and she expected an immediate invitation from him. But here she was disappointed. Hyson had sized her up in his turn and decided that she would be more eager if he did not move at once.

"Must be a bit dull for you," he replied briefly, as though he had lost interest in her. "Well, retype that letter, please, and let me have it to sign before post-time."

He dismissed her with an impatient gesture and turned back to the documents on the desk; but he followed her with a sidelong glance as she moved towards the door. Might be amusing, he reflected. A complete change from Olive, at any rate. No brains, and a different brand of looks. Olive had been just what he wanted while the first flush of enthusiasm lasted; but Hyson was a man who needed variety, and he had only a limited number of tricks in his love-making. He was coming to the end of them with Olive Lyndoch, and he foresaw the probability of the tedium of monotony creeping into their relations before very long. Besides, she had taken to speculating in a small way and insisted on getting his advice about her deals. A visit to her flat nowadays was like working an hour's overtime at the office. One couldn't get free from share prices. No, it was quite time that he found a substitute for Olive, and perhaps Kitty would serve his turn till he could look round for something better.

His musings were interrupted by a knock at the door and the entrance of the office-boy. Cadbury was an undersized youth with a complexion partly concealed by freckles and pimples, for he was at the pimply age. His fingers were invariably ink-stained, for he used a cheap fountain pen which leaked; and his tie always had a inclination to the N.N.E. He avoided Hyson's eye by looking at the desk and announced in a high voice:

"There's a client outside, Mr. Hyson. She wants to see you. It's Miss Jessop."

Hyson lifted his eyes and examined Cadbury despitefully. Curious, that while the three typists always looked spick-and-span to the last hair, Forbury and the office-boy were a disgrace to the place by their untidiness. To a man so particular about his own appearance as Hyson, they were eyesores.

"Brush your hair," he ordered tersely. "And show her in here."

In a few seconds Cadbury ushered the client into the room. Miss Ruth Jessop was a plump little woman of about thirty-six, who had just missed prettiness by a very little. That slight deficiency, and one or two other characteristics, had so far prevented her from securing a husband, though she had tried hard. But her lack of success had not turned her into a misanthropist. She did her best to be pleasant to every man she met, with a certain effusiveness which would have better suited a girl in her teens than a woman in the thirties.

"Oh, good afternoon, Mr. Hyson," she began, as Hyson drew forward a chair for her, "I'm so sorry to hear about poor Mr. Lockhurst, so very sorry. He seemed so healthy, didn't he, Mr. Hyson? It was quite a shock when they told me outside that he couldn't come to business, Mr. Hyson. It's some trouble with his heart, isn't it, Mr. Hyson?"

"Coronary thrombosis," Hyson confirmed.

He despised Miss Jessop wholeheartedly; her "young" airs and her gushingness irritated him as a connoisseur. How was it that some females were so completely lacking in that indefinable quality "charm"?

"Coronary thrombosis," repeated Miss Jessop slowly, evidently memorising the word for future use. "It sounds dreadful, doesn't it, Mr. Hyson?"—she gave an irritating giggle—"I'm afraid it makes me no wiser, really. Is it dangerous, Mr. Hyson? I mean, there's no chance of his dying from it, is there? Surely not, Mr. Hyson?"

Hyson shrugged his shoulders.

"You must ask a doctor about it. I'm not an expert."

"Oh, well, I do hope he'll soon be well again, and able to come back to the office again, Mr. Hyson. It's such a nice office, isn't it?" she said, glancing round as she spoke, with a certain inquisitiveness. "That looks a very comfortable big settee over there, Mr. Hyson. I don't remember seeing a settee like that in other businessmen's offices."

Hyson kept an unmoved face, but inwardly he cursed his visitor. Easy enough to see what the damned gossip-monger was hinting at. She'd bring out the old joke about "pressing business at the office," if she dared. And most likely she'd go round her friends now, saying how strange it was to have a settee in a private room like this. Dear little innocent, of course, merely struck by a passing thought. That was her way. But she was getting a bit too near the truth over that settee. Luckily he had his explanation ready, and it was correct, so far as it went, though it might not be the whole story.

"Mr. Lockhurst got it, six months ago," he explained coolly. "He used to feel very tired, towards the end of the day's work, and he lay down on it to rest. Probably his heart trouble was coming on, though he didn't realise it. That would make him easily tired, I suppose."

"Oh, yes, of course, Mr. Hyson," Miss Jessop answered vaguely.

But apparently her mind was still following the same line, as her next remark betrayed.

"I saw your typists as I came in, Mr. Hyson. Such pretty girls they are."

"Are they?" said Hyson. "We're more concerned with their efficiency." He glanced rather ostentatiously at his watch. "You've come about some business, haven't you?"

"Oh, yes, of course," Miss Jessop admitted. "It's about those bearer bonds of mine that Mr. Lockhurst keeps for me, Mr. Hyson, in your safe. It's the time when I come to cut off the coupons for the dividends, now, you see?"

"I'll get them."

Hyson rose and went to the safe to obtain the bonds. Just like that woman, giving unnecessary trouble. Why couldn't she keep her bonds at her bank and let the bankers credit her account with the dividends when they fell due? Then it occurred to him that this would deprive Miss Jessop of a chance of talking to a man. She preferred to come here, making eyes and chattering about settees.

"These are your bonds, I think," he said, returning to the desk. "Better check them. And here's a pair of scissors," he added, taking them from the drawer.

Ruth Jessop seemed a shade chilled by this businesslike way of doing things. She picked up the bonds; fumbled with them for a moment as though seeking a fresh subject of conversation; then, finding no encouragement from Hyson, she reluctantly picked up the scissors and began to clip off the coupons.

"And how is Mrs. Hyson?" she demanded when she had finished her clipping. "Quite well, I hope? I haven't seen her for a few days."

"Quite well, thanks," Hyson replied. "You might check your coupons and make sure you have them all, please."

"Oh, yes, of course I should do that, Mr. Hyson. So good of you to remind me. Let me see: one, two, three... Yes, I've got them all, Mr. Hyson. And how is your sister-in-law? She's such a nice girl, isn't she? It's such a pity, I always feel, that she lives in that out-of-the-way suburb, Mr. Hyson. I see so little of her. It's really too far, except once in a while. Of course, if one had a car it would be easier, but when one has to go about in buses, it's really very tiring, Mr. Hyson."

"I suppose so," said Hyson unsympathetically.

Ruth Jessop gathered up her coupons reluctantly and began to stow them away in her bag.

"By the way, Mr. Hyson," she went on, evidently anxious to prolong the interview, "what's the name of that tall, dark-haired girl in the office outside? The one with the rather hooky nose, I mean. I've some faint recollection of having seen her somewhere or other. You know how one remembers people sometimes, even when one's only had a glimpse of them once, Mr. Hyson. I must have come across her sometime, and it always worries me when I can't remember things like that, you know. I often lie awake at nights puzzling and puzzling my head to remember."

"Miss Lyndoch, I expect. You must have seen her when you came to the office at other times. She's been here for a year or two."

Hyson knew perfectly well what Ruth Jessop was driving at. She wanted to pick up some scrap of information which she could retail in their circle. "Such a pretty girl, the typist in my broker's office. One really wonders what the men are thinking about. It's as well that Mr. Hyson is so devoted to his wife, for, really, that girl is almost too good-looking to be in an office. Her name's Lyndoch, by the way. Now I wonder if she can be any relation to that stout old woman who keeps the confectionery shop in Windmill Street. The name's the same." And, of course, the whole seasoned by little animated nods and meaning glances and silly gestures of the hands to emphasise the chief points.

Miss Jessop closed her bag and Hyson let out an inaudible sigh of relief. She would have to go now, surely. But at that moment Kitty Nevern came in with the retyped letter for him to sign. Miss Jessop waited till the girl had gone, and then started off again like a rewound alarm clock.

"What a pretty girl! Really, you seem to have a perfect harem of beauties, Mr. Hyson, a perfect harem," she declared with an arch nod to emphasise her opinion. "What is her name?"

"Miss Nevern."

"Nevern? A curious name. I don't think I ever heard it before. It doesn't sound like one of our local names, does it? Where does she live, do you know, Mr. Hyson?"

"Don't know, I'm sorry," Hyson lied blandly. "Outside office hours I've nothing to do with our typists. But if she's taken your fancy, I'll introduce you to her as you go out."

"Oh, no, no, Mr. Hyson. Don't be silly, Mr. Hyson," she protested with a giggle. "She's rather a common little thing, isn't she?"

"Not knowing her outside of office hours, I can't really say," Hyson answered with a slight frown. "Now, is there anything else I can do for you at the moment? We're rather pressed with business, you see, owing to Mr. Lockhurst's breakdown."

He made a gesture towards the papers on his desk, and to his relief she found the hint too plain to disregard.

"Oh, no, there's nothing more to-day," she admitted. "I really must go, now. Please tell Mr. Lockhurst that I was asking for him, and say I hope that he'll soon be well again, Mr. Hyson. It's such a pity that he's had this trouble, isn't it? You won't forget? Thanks so much."

She picked up her bag and gave a peculiar wriggle which ostensibly was meant to settle her clothes, but which she imagined was attractive to men.

"I suppose you'll be kept working late to-night, Mr. Hyson? And will these poor girls be kept here too? No? But what if you want something typed?"

"I'll manage it myself, probably," said Hyson, rather shortly.

He showed her out through the typists' room. Olive Lyndoch was apparently finishing up some work at her desk. Effie Hinkley was putting the cover on her typewriter. At the coat-rack, Kitty Nevern was carrying on a conversation with Cadbury about film stars.

Hyson returned to the private office, leaving the door ajar behind him. He heard Effie say good-night and leave the office. Then Kitty and Cadbury departed, arguing volubly as they went.

A FEW seconds after the rest of the staff had gone, Olive Lyndoch came into the private office, dressed for the street.

"I'm ready now," she said with a certain curtness.

"Very well. You go out first," Hyson suggested. "I'll pick you up in Arthur Street."

She agreed with a nod and left the room without adding another word. Hyson looked at the door through which she had vanished, with an unpleasant smile on his lips. He waited for five minutes, then switched off the lights, closed the outer door of the office and went downstairs. His car was garaged a few yards up the street and he got it out. He turned into Arthur Street and drove slowly, keeping a sharp look-out for Olive. Apparently she had walked more smartly than she usually did, for it was some distance beyond the customary spot that he came level with her. He pulled up the car and she slipped into the seat beside him.

Often, when she took her seat, she snuggled up to him for a moment once the car had started; but to-night she sat well over to her own side, almost obviously avoiding any contact. As if quite unconscious of her coldness, he let his free hand stray over till it rested on her knee. She shook it off with an impatient movement and drew if possible a little farther away from him. He withdrew his hand and his brows tightened in a frown; but he said nothing until he had driven some distance farther. When he did speak, it was only to utter a non-committal monosyllable.

"Well?"

But Olive nursed her grievance and repaid him in his own coin.

"Well?" she answered, but on her lips the word expressed a good deal more than his had done.

Hyson had thought out his line of defence long before, but he preferred to disclose it gradually.

"What's the trouble?" he asked, feigning complete ignorance.

Olive hesitated between two courses for a moment. Should she go on sulking for a little while yet, or should she have it out with him at once and be done with it? She decided on the second alternative.

"You know quite well what it is, Ossie. You needn't pretend you don't. Why did you speak to me like that before Kitty Nevern? I won't be treated like that, understand? A bit steep, hauling me over the coals in front of a young chit that's just come into the office. I won't have it!"

Hyson's lips tightened.

"You know quite well that you're not supposed to have access to the private ledger."

"Well, you could have spoken to me about that when we were alone. There was no need to rate me, the way you did, with that little fool standing by to hear it."

Hyson turned his head towards her for a moment and gave an understanding smile.

"I see what you mean," he admitted frankly. "But, look here, Olive, I had to do it. Forbury was with me just before that, and he wanted to take over the private ledger. I put him in his place over that, quick enough, and no kindness wasted in the telling. Now suppose he heard that you'd been going through that ledger. He'd be bound to hear of it, in our office. Well, you can guess what would happen. He doesn't love either of us. He'd begin to put two and two together. 'Miss Lyndoch, of course, has special privileges. H'm! H'm! That's funny, isn't it?' We can't afford any ideas of that sort. I might as well bring the car round and pick you up on the office door-step at night. So, naturally, I had to make sure of stifling the business at the very start. That bit of play-acting in front of the Nevern was the safest move. See that? It meant nothing. Camouflage."

There was sufficient truth in his explanation for it to carry weight with Olive. She had not known about Forbury's offer and it threw a slightly different light on the episode. And it was perfectly true that their relations in the office must be made to appear normal. A hint of the real state of affairs would make things awkward if it got about; for these things can't be kept within four walls when people begin to talk.

"I see," she admitted, but rather grudgingly. "If that was what you were after, perhaps it was the best you could do. Still, you might have been a shade politer. I saw that little beast Nevern grinning when she came out of your office afterwards. I suppose she took it as a good joke, seeing me told off before her."

Hyson's hand crept over to her knee again and this time she did not shrink from it.

"It was the best I could think of, on the spur of the moment," he declared. "I hadn't time to do better. I didn't mean to hurt your feelings, Olive. I thought you'd see the point. Of course I forgot you didn't know about Forbury's move. Stupid of me. You're all right now?"

"Oh, yes, all right," Olive said, though there was still a faint reluctance to abandon her grievance. "Only, don't do things like that again, Ossie. They're not... Well, we'll let it go at that."

She moved an inch or two nearer to him, and he could feel her knee quiver under the pressure of his hand. He knew how to handle her, he reflected with satisfaction. After all, she was keener on him now than he was on her, and that always gave a man a pull over a girl.

Very soon they reached the street in which Olive Lyndoch lived, a short, dingy, grey cul-de-sac lined with tall flats which had seen better days. The girl stepped out on the pavement and waited while Hyson locked his car. When he rejoined her, they had fifty yards still to go, for Hyson always took the precaution of drawing up his motor at some distance from the entrance to her flat. The chance of anyone noting his empty car was hardly worth considering, since most of his friends lived on the other side of the town; but he preferred to be on the safe side.

When they reached Olive's flat on the second floor, she made as if to open her bag, but Hyson took a key from his pocket and saved her the trouble of hunting for her own. He stood aside to let her enter the little hall. Then, with the door shut behind them, he put his arm round her waist and kissed her on the cheek. She suffered the caress rather passively, then, slipping out of his embrace, she walked into the sitting-room.

It was small, but comfortably furnished: a couple of deep arm-chairs by the hearth, a settee rather like the one in the office, a tiny dining-table with a cold meal set out ready and two chairs drawn up. The colour scheme of the room proved that Olive Lyndoch's taste in decoration was as sound as her taste in dress.

"Just wait a moment, Ossie, while I take some things off," she directed, as she passed into the adjoining room.

Hyson sat down in one of the arm-chairs, pulled out his cigarette case, then, thinking it hardly worth while to smoke since he knew Olive was quick in everything she did, replaced the case in his pocket. In a few minutes, she returned, and Hyson noted with a slight relief that she had changed into a silk thing which might have passed as either a boudoir gown or a dressing-gown. Knowing her moods, he inferred that this meant that she had got over her ill-temper. If she had intended to rake up her grievance, she would have sat down in her out-door dress. Since she was meeting him half-way, he looked up with a smile as she came in. She seemed to have forgotten their altercation on the way, for she made a gesture to show off her costume before she sat down at the table.

"You haven't seen this before. What do you think of it?"

"Very pretty," Hyson said, letting his eye run over the supple figure which the clinging silk revealed. "You always manage to get things just right, somehow. Goes with your eyes, doesn't it?"

"It wasn't cheap," Olive confessed, "but when I saw it, I just had to take it."

"This the first time you're wearing it? Must put a threepenny bit into the pocket as a surprise for you. A handsel, they call that in Scotland."

"Well, come along and sit down. It's a ghastly hour for a meal, but you always have to leave so early in the evening."

Hyson seated himself opposite her, and as he did so, a faint touch of boredom came upon him. Variety was the very spice of life to him in his relations with women. A fresh conquest meant a whole new series of episodes and sensations. And here he was, sitting down to look at a girl across the same table, once a week, week after week. He might as well be married to her and be done with it, he reflected sourly. Was it really worth it? Still, he didn't propose to break with her just yet.

"By the way, Ossie," Olive began after a few minutes silence, "what about these International Nickels you advised me to buy a while ago? They don't seem to be doing much. Should I sell out and try something else?"

"I'd hold on for a rise," he advised. "Sell out, if they go up at all, though."

"And those oil shares, what about them?"

"Market's very sluggish. Better stay put."

"Is there nothing better?"

"Plenty of wild-cats, if you want a gamble. Advise you not, though. Lose your money, as like as not. And I'm not going to offer tips in that line."

Internally he fumed, though he kept a smile on his face. Overtime at the office, really, this advising her about her miserable little specs. As if his own didn't give him enough worry, without taking other people's troubles on his back. And once or twice, when his advice had gone wrong, she hadn't shown an understanding spirit. A girl in a stockbroker's office ought to have sense enough to know that one can't predict with certainty in the matter of market movements.

Olive was quick to see that she was boring him. She dropped that subject at once and turned to a fresh one.

"You're in charge at the office so long as Lockhurst can't get back to business, aren't you, Ossie?"

Hyson nodded in reply.

"How long will he be away? Did they give you an idea?"

"Three months, at least. Four, probably, from what the nurse said. He'll not be fit to do any business for three, anyhow."

Olive hesitated for a moment before her next move.

"Do you think you could manage to put through that reorganisation while he's away? Getting in the Moon-Hopkins machine, I mean, and making me bookkeeper. I've been looking into the system, and I could easily take it up if the chance came my way. It would mean a rise in screw for me, of course, and then you wouldn't need to help me with the rent of this flat. I'd rather not take money from you, you know."

Hyson paused before answering. When Olive had first attracted him, she had been living in a boarding-house. The office, after hours, had served for their meetings; but soon Hyson had felt that it was too risky as a permanent arrangement. She had scrupled about taking money from him; but he had insisted on paying her the difference between the cost of the boarding-house and the expenses of this cheap flat. And he had not been altogether averse to paying. It put her to some extent into his debt, and that was always a point in the game. He could afford it well enough, and he was not sure that he wanted to see her standing entirely on her own feet financially. She might get a bit too independent, in that case.

"A bit difficult to put that through, Olive. At least, as things are. It would mean sacking Forbury—I want to get rid of him anyway."

"Push the table into a corner and bring the settee forward, please, Ossie, while I take these things into the kitchen," she directed. "I want to have a talk with you."

He did as she asked; and when she came back again she joined him on the settee, nestling up to him with a little sigh of content.

"There! That's comfy," she said, turning to kiss him as he put his arm around her. "Now, I've got a surprise for you, Ossie. I've seen your wife."

Hyson's arm relaxed suddenly and he looked at her with a glint of anger in his eyes.

"The devil you have! How did that happen? You haven't been doing anything silly, have you?"

She drew away a little in her turn and looked at him seriously.

"I'm not a fool, Ossie. You don't suppose I went to your house, rang the bell, and asked to see her, do you? Make your mind easy. I didn't even go pretending to be a charity collector, as I might have done for the fun of the thing. No, no. It's quite all right, so you needn't panic. Last Sunday afternoon, I had nothing to do except go for a walk somewhere, and I'd nowhere in particular to go to fill in the time. It came into my mind that I'd like to see what she's like. No harm in that, so far as I can see. I've heard something about her, enough to make me curious, you know. Why not take a bus over there, stroll down your avenue, and take my chance of getting a glimpse of her? It was a hundred to one against seeing her and I really did it because I'd nothing else to do."

Hyson seemed a shade relieved by this account.

"Well, so you did see her?"

"Yes, she was sitting out on the lawn in a camp-chair. She's got fair hair, hasn't she? And she was wearing grey, wasn't she? I was pretty sure it was she. I'm not jealous of her, Ossie, not a scrap, for I know she's nothing to you nowadays. It was mere curiosity that took me there. She's very pretty."

"Oh, I suppose so," Hyson agreed. "I've gone off that style in looks, though, long ago."

Olive gave him an uneasy glance. That careless confession of inconstancy carried its sting; for if he had grown indifferent to his wife, he might well grow weary of herself in turn and go off in search of fresher attractions. She tried to put that out of her mind; but at odd, uncomfortable moments it cropped up, insistent, terrifying.

In the early days of their association, he had been the one to seek opportunities to meet her alone. Now it was she who had to plan and cajole and persuade in order to get him to herself for even these few hours each week. And the less eager he grew, the more imperious became her need of him. Even this poor simulacrum of married life had become something which she could not afford to lose, and she cast about desperately for the means to make it permanent.

But here she had come up against the limitations of his temperament. As a complete human being, compact of flesh, brain, and emotion, she hardly counted with him. He simply was not interested in her inner nature. She had tried to attach him more firmly by the subtler fibres of thoughts and feelings, and she had failed completely. Externals were all he cared for. And, inevitably, sooner or later, externals grow so familiar that they cease to yield the old thrill. "I've gone off that style in looks, though, long ago." There it was, in a nutshell. And her turn would come next, unless she could force their relations into some fresh groove. Anything rather than be left as a discarded mistress, a failure who hadn't even managed to keep a hold on the man she had chosen.

"I've just been thinking, Ossie," she said, after a pause. "Suppose she found out about us. If you're not fond of her now, she can't be getting much out of marriage. She would take proceedings if she had the evidence, wouldn't she?"

And if she would, Olive reflected, it would be easy enough to put Linda Hyson on the scent. A single letter would do that.

"I wouldn't mind going through the court, if she did," she added.

She felt it safer not to speak of a subsequent marriage. Ossie was in an awkward mood this evening and there was nothing to gain by looking too far ahead. She and he had always avoided the subject of his wife, and Olive knew hardly more than Linda Hyson's name until that glimpse in the garden had given her something concrete to think about. But Hyson's answer brought her up suddenly against an undreamed-of obstacle.

"Divorce me, you mean?" he said abruptly. "Wish she would. No chance of it. She's a strict Catholic. Divorce doesn't go, with them. She'd never think of it."

In all her dreams and speculations, Olive had thought of Hyson as like all the other men she knew. He was married, of course; but marriage was not necessarily a permanency. At the back of her mind, from the very beginning, there had been the idea of a divorce as a final clearing-up of the situation. And now, at a single stroke, she saw this solution made impossible in the way she had never anticipated. She had heard of so-called mixed marriages, but it had never occurred to her that Ossie's marriage might be one of that kind.

"They don't believe that, do they?" she exclaimed, aghast.

"They do. She does, anyway, and that's all that matters, so far as I'm concerned."

Olive Lyndoch had a quick mind, and almost instantly a fresh solution presented itself.

"There's nothing against you divorcing her, is there?" she asked. "I mean, if you could prove anything against her, it wouldn't matter about her being a Catholic, would it? You could get your decree?"

"Oh, yes," Hyson admitted. "But you can put that out of your head. She's not that sort."

Olive reflected for a moment or two.

"How do you know?" she demanded. "If there were anything, you'd be the last to notice it. You've no interest in her now. You're at the office all day. What does she do with herself then? Or when you come here in the evenings? You don't know."

"No, I don't," Hyson replied, rather crossly, as though the idea gave him a shade of discomfort. "But Linda's not that sort."

"I wasn't 'that sort' either, until you persuaded me," Olive retorted with more than a trace of acid in her tone. "Isn't there any man in her circle, or does she meet nobody except women?"

Hyson did not answer for some moments. Apparently he was thinking over her question. Then he shook his head decidedly.

"No, you're on the wrong tack. There's nobody in her crew who'd have the backbone," he commented scornfully. "There is a fellow who comes about the house. Nice little gentleman. What you call a tame cat. But he'd be no use. 'I could not love thee, dear, so much, loved I not honour more.' And all that sort of thing, Barsett, his name is. But you can leave him out of the betting."

"What you really mean is that it couldn't happen to you," said Olive with a smile which seemed rather awry. "I used to think that myself, before I met you, Ossie. You never can tell."

Hyson was frankly amused.

"Trying to make me jealous of him?" he asked. "Waste of time."

"Well, you make other people jealous," Olive said incautiously. "It would be only fair if you suffered yourself."

Hyson looked at her with only half-concealed amusement.

"Who is it now?" he said, teasingly. "That new girl at the office, perhaps? What's her name... Severn... Oh, Nevern, that's it." Then, realising that this was likely to bring up Olive's grievance about the private ledger, he hurriedly continued, "Or Miss Jessop, maybe? You can make your mind easy. She gets on my nerves, that woman, with her continual 'Yes, Mr. Hyson,' 'No, Mr. Hyson.' "

The mention of Miss Jessop deflected Olive's thoughts.

"That woman might be dangerous," she said, soberly. "She's got a perfect itch for gossip. She was in the office lately when Lockhurst was busy and kept her waiting.

She spent the time trying to pick up all the information she could get out of me. It's not because she's interested. I could see that. It's just that she'll pick up any bit of news the way a jackdaw picks up anything bright. You be careful of her, Ossie."

"I'd rather have the Nevern, if it came to a choice."

Hardly were the words out than he cursed himself for his folly. That was the worst of thinking too much about Kitty; her name had slipped out before he knew what he was saying. And Olive was quick to read his mind. She drew herself free from his arm with a lithe movement and turned deliberately to look him fair in the face.

"That's twice you've mentioned her in the last couple of minutes, Ossie. She must be very much on your mind, surely, when you can't keep her off your tongue. Oh, I know you well enough! You think you can get round her, and it's likely enough that you could. But before you begin, just get this clear. You've dropped your wife, and she doesn't seem to mind that. But I'm not like her, understand that; I'm not the kind of girl you can pick up to amuse you and drop again when it suits you. Don't try to put her in my place...."

She stopped suddenly. When she began, she had no intention of saying as much as this; but her jealousy had carried her away and the words had slipped out before she could pull herself up. Now she looked at him, half-frightened, lest she should have done irreparable damage.

Hyson could think quickly also. With a certain roughness, he pulled her back to him.

"Don't be an ass, Olive. You're getting to the state where one can't say a girl's name without you flaring up. It's silly. I'm not bothering about Kitty Nevern. Engaged, for all I know, or care. What's the good of my coming up here at all if you're going to go on this way? I've known more amusing ways of passing an evening. Forget about it. I'm a bit worried, just now. Nerves on edge, rather. Don't know why. But that makes me tease people, without wanting to do it. Working it off on someone else, perhaps. I'm sorry it was you who got it."

Olive was only too eager to accept peace. And, looking at him earnestly, she did see signs of worry. Subconsciously she had noted them much earlier and she now recalled that to mind. Her voice was gentler when she spoke again.

"What's worrying you, Ossie? Let's hear about it."

But Hyson was not the man to take any woman into his full confidence.

"Don't let's waste time over it," he said, irritably. "It's nothing much. Give me a kiss, that's more to the point."

He drew her to him, and though she still resisted faintly, his attraction was too strong for her. She wanted him more than he wanted her, she recognised reluctantly. Anything to have his arms round her and forget things while she could.

When Hyson let himself out of the flat an hour or so later, his troubles attacked him again, bringing reinforcements to help them. He remembered Olive's face and the flash in her eyes when she had lost her self-control for a moment or two. She hadn't actually threatened him. Amounted to the same thing, though. And he knew her well enough to guess that the unspoken menace had been serious. She was past caring what happened if she once lost him. Dangerous, that, on top of his other troubles. And she had her weapon to hand, worse luck. If she blew the gaff to old Lockhurst, told him she'd been Hyson's mistress, then the old Puritan would boot him out into the street. The sack, with a month's salary. Suppose that happened to-morrow? Phew!

Further musings made the affair no brighter. Marriage was what she wanted. Just when he was growing bored with her, too. Well, thank heaven, that was out of the question, short of Linda going off the rails or dying. But to have a woman with a hold over you might be even worse than marriage in some ways. He wished he'd never set eyes on her! And now, of course, it wouldn't be safe to touch Kitty. Silly little fool, that girl, she'd never be able to keep the thing from Olive's eyes, in the office, if he once started. No, no good. Have to drop the idea. Another notch in the score against Olive. Why couldn't these women realise that a man wanted change? Curse them!

WHEN Linda Errington's engagement to Hyson was announced, her friends were incredulous. Then they shrugged their shoulders and said it amazed one to see the kind of man a nice girl could fall in love with. But love was like that, of course.... When she married, they tolerated Hyson rather than hurt Linda's feelings by showing their real estimate of her husband. And when she herself waked up to a clear vision of the man she had married, she thought all the more of her friends for their behaviour. After all, Ossie probably had some good in him, like everyone else in the world.

Once he grew tired of her, he left her very much to her own devices; and she made no complaint. She merely set about filling the time which he might have occupied had things turned out differently. She had plenty of friends to see; she liked the cinema; she served on the Ladies Committee of a local hospital; she played golf in summer and badminton in winter; and bridge filled in any spare evenings when time might have hung on her hands. In fact, she much preferred to have small bridge parties at her house on the nights when she knew he would be out. Oswald Hyson's card-sense was rudimentary and he spoiled the evening for good players if he was at home and took a hand. Also, oblivious of his deficiencies, he was always ready to argue in defence of his play, which made things unpleasant.

On the night that Hyson visited Olive Lyndoch's flat, Linda had arranged a table: herself, Norris Barsett, Jim and Nancy Telford. They all played to much about the same standard, and none of them wanted to go higher than threepence per hundred. A very pleasant little evening, it had been, for luck had been fairly evenly distributed during the early rubbers. While the cards were being shuffled, Linda rose and went to switch on the electric kettle.

"We'll have to fend for ourselves," she explained. "Thursday is Cissie's night out. We'll go on with the game. These kettles take such a time to boil."

She sat down again at the table and the game proceeded. Half-way through it, the door-bell rang. Linda made a faint grimace as she put down her cards.

"Who can that be? Just excuse me a moment while I go. That's the worst of keeping only one maid."

She left the room. The others heard the front door open, then the sound of voices, and, after a minute or two, Linda ushered Ruth Jessop in.

"I happened to be passing and saw the light here, Linda," she explained effusively, "and I thought I'd just drop in, in case you were all alone, needing company. And then, as I came up the path past the window, I saw you had friends in and I thought of going away. But I just made up my mind I'd come in. I won't break into your bridge unless you ask me to cut in. I'll just sit quiet and watch you play."

Jim Telford glanced at the window. The blind was down, but it hung slightly askew so that Ruth had obviously been able to see through the aperture and note what was going on in the room. He rose to his feet and moved across as though to set it straight, but Linda called him back.

"It's no use trying to make that blind right, Jim," she said. "It always comes down a-slant, like that. I've been meaning to get it rehung for long enough, but I never remember about it at the right moment, somehow. I've got a memory like a sieve for things like that."

She was too good a hostess to show any sign that Ruth's incursion had upset her arrangements; but inwardly she was making rapid calculations. Ruth, poor thing, lived on the tiniest income and half-starved herself, despite her plump appearance. As a result, when she joined any friend at a meal she seemed determined to make up for home deficiencies and displayed an enormous appetite. At afternoon tea, she ate as though she did not expect to see another meal before breakfast-time. Linda's preparations had been based on a very different scale, and she reckoned up the result of Ruth's arrival with some dismay.

"Well, it'll mean cutting more bread and butter," she concluded, ruefully. "These sandwiches and cakes aren't half enough for her, even if the others ate nothing. And I'd like her to get all she wants. If only she wouldn't drop in like this!"

She did not reflect, though she might have done so, that Ruth Jessop "dropped in" more often than not. People, somehow, had fallen out of the habit of asking her to bridge. She would insist on talking while the hand was being played. Linda was sorry for her and would have invited her oftener; but one had to think of the other guests' feelings.

Ruth, with some characteristic fussiness, finally got herself installed in an arm-chair, and the game continued. But she could not restrain herself and she at once began to talk.

"Are you going to Mollie Keston's wedding, Nancy?" she demanded, turning to Mrs. Telford. "They sent me an invitation, and I'd such difficulty in getting a nice present for her. I chose a tiny toast-rack, finally. Just the thing for a bed-tray."

Nancy Telford looked round with a slightly irritable air. She was an old friend of Linda's. They had grown up together. Then Nancy had married Jim Telford and he had taken her off to Scotland, so that the two girls saw each other only when Linda went North or when Nancy came on a visit to her widowed father. This time, it was hardly a pleasure visit. Linda had been taken aback by the change she noticed in Nancy. Something had gone wrong with her health. She looked different, somehow, with a disturbing look in her eyes—a kind of haunted expression, as Linda described it to herself. She had sympathised with Nancy, and evidently Nancy needed sympathy badly. But what the trouble was, Linda had no idea. Nancy volunteered nothing about it. There were some things—like cancer—that one didn't discuss. Linda hoped that it wasn't anything of that sort; and since Nancy maintained her reserve, Linda kept away from the subject. It was something serious, she guessed; for Jim Telford seemed worried also, and he was a man who generally kept his troubles under. Whatever it was, it hadn't made them less fond of each other. Nancy seemed, if anything, keener than ever on Jim. He had come down for a week; after that he'd have to go back home and look after his business, leaving Nancy in the care of Dr. Malwood, a local specialist in whom they seemed to have implicit trust.

Linda, watching them, could find it in her heart to envy them despite their present trouble. They had got all that she and Ossie had missed. An ideal love-affair, a rapturous engagement not too prolonged, and complete happiness in their married life. Very few people had been so lucky in the things that really mattered. They were not rich, but they had all the money that they seemed to want. And they had complete trust in one another, as Linda knew. What a contrast to her own life since she had married Ossie.

"Yes, I'm going," Nancy answered Ruth's question about the wedding, and then turned back to her game.

"Mollie's quite passable-looking now," Ruth commented. "One would hardly have expected it, seeing what a gawky child she was. I don't much care for these tall thin girls, though."

"I think Mollie's very pretty, Ruth," Linda declared. "And you needn't talk as if she were a bean-pole. She's slim, but she's got a nice figure."

"That's a matter of taste, dear," Ruth retorted, evidently nettled by the implied criticism, "so we needn't argue about it, need we? By the way, who's going to be her bridesmaid?"

"Nina Alderbrook and Dorothy Campdale," said Nancy, curtly.

"Nina Alderbrook? I don't know her. Is she the daughter of Alderbrook the coal man who made a lot of money in the war? Oh, now I know who you mean, of course. Her grandmother used to keep a tiny little grocer's shop after her husband died, I believe. It's wonderful how some people come up in the world, in these days. But of course it's just money."

Ruth's father had been a general practitioner; and she had a habit of looking down on anyone connected with trade, no matter how successful they had been. If they had been less successful, she looked down on them still more.

"The classes are getting very much mixed up, since the war," she went on. "Now, in the old days, the Kestons would never have looked at the Alderbrooks. They were in a different stratum altogether. Their friends were among the country gentry. They still have some of them. I remember the last time I happened to go up to their house, I met a Mr. Wendover. He has a big estate."

"Wendover? Is his place called Talgarth Grange?" asked Barsett.

"Yes," Linda confirmed. "He's a friend of the Chief Constable of the county, Sir Clinton Driffield. They're both coming to the wedding. Mr. Wendover's an old friend of Mr. Keston's. He used to have Mollie and a lot of other young folks to stay with him at the Grange. She looks on him as a kind of unofficial uncle."

"Who is Sir Clinton Driffield?" demanded Ruth. "Is he a baronet or just a knight?"

"He was abroad before he came here, in South Africa or Malaya or somewhere," Linda explained. "And he must have been pretty good, since they gave him a knighthood quite young, for something he did out there. Mollie thinks the world of him."

"The next three are mine," said Jim Telford, laying down his hand. He glanced at his wife with faint anxiety. "Feeling headachy, dear?"

"Not exactly. But I think tea would do me some good. That kettle's just come to the boil, Linda, if you don't mind my giving you a broad hint."

"So it is. Just a moment while I infuse the tea and bring in a tray."

Norris sprang to his feet.

"I'll get the tray, Mrs. Hyson. Where is it?"

"In the pantry, at the end of the passage. Thanks."

Ruth Jessop's mouth-corners turned down a little as she saw Barsett going for the tray. She could never get accustomed to Linda's easy naturalness with men. What an idea, letting a male guest bring in a loaded tray from the pantry! She ought to have gone out without saying anything, brought the tray into the room, and then let a man take it from her. Ruth Jessop had very definite ideas about what one ought or ought not to do.

Jim Telford cleared the cards and markers from the bridge-table. Ruth Jessop's eyes ran over the cakes and sandwiches appraisingly. She barely waited for them to be offered to her, but met the extended plate half-way. Linda always had nice things, she reflected, as she took her first bite.

"Isn't Mr. Hyson in to-night, Linda?" she inquired demurely.

Linda shook her head.

"No, he's gone to some meeting or other, I suppose."

Hyson, to account for his absences in the evening, had devised the convenient fiction that he belonged to a number of societies: Freemasons, Foresters, Oddfellows, political associations, and others. Linda had never troubled to discover whether he really did belong to anything of the kind. She found the story convenient when people like Ruth Jessop grew inquisitive.

"I saw him this afternoon, Linda," Ruth continued. "I had to go to the office to cut off some coupons. I always like to do that for myself, you know. What pretty girls the typists are. I saw them as I went through to the private office. There's one I hadn't seen before, a fair-haired one. Rather a forward little thing, I thought."

"I've never been in the office," Linda said, hoping to stem this flood of information.

"Never been there, Linda? I'm surprised, really. Aren't you interested in the place Mr. Hyson works in? Well, I can tell you the private office is beautifully furnished. There's a big settee in it that four people could sit on. It looks most comfortable. I wish I had one like it in my sitting-room, to lie on."

No one seemed interested in the settee, she noticed to her regret.

"I believe you're interested in wireless, Mr. Telford," Norris Barsett broke in after just the right interval of silence.

"I do a little on the short waves," Jim Telford admitted. "I've had a forty-metre licence for a while and lately they've allowed me to transmit on the ten-metre band. It's rather good fun."

"So I'd suppose, from what I hear occasionally on the forty-metre band with my receiver. You pick up a lot of—what does one call them?—correspondents, don't you?"

"A fair number. Sometimes it's rather funny. The other week I got in touch with a fellow in South America. He knew no English, and I know no Spanish, so we compromised on pidgin-French with wild hunts through the dictionary between sentences. I understood him, more or less, and I think he got about fifty per cent of my meaning, so we really did quite well between us."

"Have you got in touch with him again?"

"No, not yet. The fact is, I prefer to talk to British or American amateurs where one can understand the language. It's too much like work, haranguing foreigners when you don't understand what they mean by half their discourse. I've got a group of people who know the hours I'm on the air, and I can generally get hold of one or two of them when I want someone to talk to. That reminds me, Linda, I know two amateurs here. If we ever need to send you a message in a hurry, I can do it through them. It might be quicker than a wire."

"But not quicker than the phone, Jim," Linda reminded him. "At least, by the time your friend got the message and sent it along here the phone would have you beaten to a frazzle, even allowing for the wait for the trunk line."

"I'm not so sure of that," declared Jim. "This fellow Scarsdale, as it happens, lives just around the corner from here, in Vendale Road, so there wouldn't be much time lost in sending a message round to you. The other fellow's a bit off the track, I admit. He lives a couple of miles from here."

"Well, I'd rather you trusted to telegrams, Jim, if there's any special excitement."

"No use for wireless, evidently," said Jim, in a tone that showed he took the rebuff without offence. "But you don't know how useful it can be, Linda. I'm going to introduce Nancy to Scarsdale and his family. It's not supposed to be done, but he says he'll be glad to let her talk to me over his transmitter any time she wants to, once I go up to Scotland again."

"That will be nice," Linda admitted. "Much nicer than talking on the phone when you're always likely to be cut off because someone else wants the line. There's something to be said for the thing after all, it seems. But you can't ring up just when you want, can you?"

"No," Nancy answered for Jim, "but it's easy enough to fix a time beforehand and then Jim will be waiting for me to speak, you see."

Ruth Jessop paid little attention to this talk. She was busy making a hearty meal, and the sandwiches were disappearing rapidly. Luckily, she noticed, no one else seemed to want much to eat.

"Well, if I were in your shoes, the first thing I'd use the thing for would be to ask Jim to be careful in his boxing-class each time you ring up, or call up, or whatever the right word is," said Linda. "Do you really enjoy knocking these unfortunate newsboys about, Jim? Or, rather, do they enjoy it? I'm all for good works and that sort of thing, but making mites' noses bleed hardly fits in with my ideas of charity, somehow."

"But, dash it, Linda, the little cubs enjoy it. It's good for them. It makes them keen to get fit, you know. They do all sorts of exercises, just to improve their physique and make a better show. You should just see them; they're as keen as mustard. And if that isn't good works, what is? It knocks ideas of fair-play and sportsmanship into them, and it makes them fitter to look after themselves if they get into a scrap. There now, it improves them physically and morally; and after all, they don't get punched on the nose every round, at least not enough to make it bleed. You've got gruesome ideas, that's what's wrong."

"Something in what you say, perhaps, Jim," agreed Linda. "I hadn't looked at it in that way."

"It's better for them than playing pitch-and-toss at street corners or spending the evening over a shove-ha'-penny board," Nancy put in. "Jim's quite right, Linda. I've seen some of his protégés when he took them in hand and I've seen the finished article, and there's no denying the improvement he makes."

Inwardly she was reflecting that if Linda's husband spent his spare time as profitably as Jim, he would be of more use in the world.

"Don't you think there's far too much done for the working-class nowadays, Mr. Barsett?" Ruth Jessop intervened.

All the plates were empty now but for a solitary cake, and she had time for conversation.

"I can't say, really," Norris replied with the air of one weighing the question but unable to come to a conclusion.

"Well, I do, Mr. Barsett. Look at this thing of Mr. Telford's. Why should these ragamuffins get all this instruction for nothing, when people of our class would have to pay for it, Mr. Barsett?"

"They don't get it for nothing," Jim interrupted. "They pay a copper or two—it's as much as they can raise—towards the hire of the hall."

He was evidently put out by Ruth's criticism of his youngsters and though his tone was even, it was clear that he was annoyed.

"Oh, in that case, of course, Mr. Telford, it's all right, quite all right," Ruth hastened to assure him. "Still, I do think that the working-class are pampered nowadays. And we do have to pay for it. People don't value a thing when they get it for nothing, I always think, Mr. Telford."

She hurriedly took the last remaining cake from the plate.

"I shan't keep you a moment, Linda," she assured her hostess, "if you want to clear away the tray. I suppose you'll want to get back to your bridge, won't you? I mustn't ask to be allowed to cut in. I get so little bridge, nowadays, somehow, that I'm quite out of practice."

After this, it was impossible to avoid suggesting that she should cut in and overbearing her effusive protests.

"I'll take the tray, Linda, if you'll tell me where to put it," Jim Telford volunteered. "In the scullery? I know my way, don't you bother to come."

Again Ruth saw that Linda Hyson would never learn how things "ought" to be done. Fancy letting Jim Telford invade the scullery with a tray! Linda, however, never seemed to understand such matters. She allowed Telford to remove the tray without protest.

In a few moments he returned.

"Nothing smashed," he announced with a grin. "I thought it was a goner, though, when I lifted my elbow to switch on the light. By the way, Linda, I see you've still got the gas-cooker. I thought you were talking about putting in an electric one."

"So I did," Linda explained. "But Cissie knows the ways of the old cooker and didn't seem over-keen on learning about an electric one, so I dropped the notion. She'd have been peevish for weeks if I'd gone against her ideas. One has to humor these old family retainers, you know. They're not easy to replace, nowadays. I don't want to lose Cissie."

"I think it's dreadful," Ruth commented, "the way people are going and committing suicide with gas-ovens nowadays. One sees it in the papers almost every day. And motor-cars, too, Mr. Barsett. I'm sure half these accidents in closed garages are really suicides if one could only get the whole truth about them."

"Don't be so gruesome, Ruth," said Nancy, with a touch of irritation. "I hate people talking about death, and graves, and suicides. Think of something more amusing."

"Sit down, Jim," Linda broke in, anxious to smooth things over. "Suppose we cut, now? Oh, yes, of course you're coming in, Ruth. Don't be silly."

The cut excluded Barsett, and he rose to leave his chair free. He glanced round and selected a seat which allowed him a view of Linda's profile, so that he could look at her without attracting attention. At the end of the round, Ruth Jessop had thought of a fresh subject of conversation.

"Isn't it dreadful that they can't find out who's sending these awful anonymous letters?" she demanded. "It's a disgusting thing, Mr. Telford, isn't it?"

"I'm afraid I wasn't listening," Jim Telford apologised. "What did you say?"

"Oh, of course, you won't know about it since you've only been here a day or two, Mr. Telford. It's really dreadful. Somebody has been writing the most awful anonymous letters and posting them to people round about here. You've no idea what dreadful things are in them."

"Do people show them around, then, after they've got them?" asked Jim Telford in a tone of faint surprise. "If I got anything of that sort, I think I'd bum it and say nothing to anyone."

"But that would never do at all, Mr. Telford," Ruth protested. "If everybody did that, how would the authorities ever catch the creature that's doing it, Mr. Telford? I tell all my friends it's their plain duty to help the Post Office people to detect the person who's doing it. You don't know all the harm that's being done by these things. It's... it's dreadful, Mr. Telford."

She stuttered with emotion as she concluded, and Jim Telford wondered why she seemed to be so affected by a thing of that sort. She caught his glance and continued, with an expression of violated modesty on her face.

"It's easy enough to say you'd burn one if you got it, Mr. Telford," she said heatedly. "But if you saw the kind of thing that's in these letters, you'd want the writer caught and put in gaol, I know you would, no matter what you say. They're... they're obscene. I mean it. They're... Well, if you ask me, I think they must be written by a lunatic."

"You've seen some, then?" asked Jim.

"Yes, I have!" Ruth declared, pursing her lips. "I got the very first one, Mr. Telford. At least, I was the first person to take one to the Post Office people and complain. There may have been other people who got them before that and burned them," she said with an obvious sneer. "They say the most dreadful things, I can assure you. It's not just abuse. They take hold of something and twist it... . Oh, I can't tell you about it. Linda, you had one, hadn't you? Jennie Mason told me you'd said something to her about it."

"Yes, I had one," Linda admitted. "I handed it over to the Post Office. It wasn't pretty. Don't let's talk about it."

"And John Anderton had one," Ruth continued, disregarding the hint. "I believe that was what broke off his engagement, though perhaps that wasn't altogether a bad thing for they didn't really suit each other. And Mollie Keston got one, so I heard. A whole lot of people have had them."

"I had one myself," Norris Barsett confessed. "So had Sam Camplin and a man called Allardyce, I happen to know. There's certainly a perfect epidemic of them, Mr. Telford, and from what I've seen of them I'm inclined to agree with Miss Jessop. The only thing one can do is to give the authorities all the evidence one can, so as to get the writer run down before more damage is done. There's no saying how much harm might come of it if this sort of thing's let alone."

Linda Hyson tapped the table impatiently.

"They're your cards, Jim. Let's get on with our game."

In Linda's circle, by tacit consent, bridge was allowed to end about midnight; and on this evening they finished a rubber a quarter of an hour before twelve o'clock struck.

"Not worth beginning another?" Jim Telford suggested, with a glance at his watch. "We'd better be moving on, Nancy."

Linda made no effort to detain them. She had enjoyed her evening, but she wished that Ruth Jessop had not come in to make a fifth. Still, if it gave the poor thing any pleasure, one shouldn't grudge that.

"Well, it's been quite a nice game," she said, adding with a gesture to the two men, "Have some more whiskey? I don't know what the motor-equivalent of a stirrup-cup is. You won't? Then you might tot up the score, Jim, and let me pay my debts."

They squared their accounts and her guests rose to leave. Nancy Telford, after a moment's hesitation, turned to Ruth.

"It's a beastly wet night. Can we give you a lift?"

Ruth had seen two cars on the drive as she came in. In her turn she glanced at Norris Barsett, hoping for an invitation from him. It would be more exciting to go home with a man alone, instead of with the Telfords. Ruth, despite disappointments, had never given up hope of securing a husband. One never can tell, she reflected optimistically. Norris Barsett, however, ignored her glance and she had to accept Nancy's invitation.

"Oh, it's so good of you," she declared, effusively. "It's not taking you out of your way, that's one thing. Thanks so much."

The Telfords showed no inclination to linger, and before Ruth could start a fresh subject of conversation and thus delay her departure, she found Jim helping her into her coat in the hall. And almost immediately she was in the Telfords' car, passing out of the gate.

Linda closed the door and turned back into the room where Norris stood waiting for her. She had wanted him to stay behind, and yet, in a way, she was sorry she had let him do so. Things were very difficult, she reflected. Norris was a dear, but the whole affair was simply a blind alley. There was no solution ahead, according to the rules of her game.

As she re-entered the room, Norris stepped forward eagerly to meet her and, putting his arm around her, he drew her down beside him on the chesterfield. She submitted, but reluctantly as though under protest.

"It's really no good, Norris," she said, rather sadly as he bent over to kiss her. "I shouldn't let you do this kind of thing. If I didn't care for you so much, it would be safe enough; but it's just playing with fire, as things are. It can't come to anything, you know, dear."

He drew her closer and for a few moments she clung to him. Then with an effort she freed herself.

"No, that's enough," she panted. "We mustn't."

Norris made a gesture, half-angry, half-despairing.

"It makes me rage to think of your being tied to that fellow. Listen, Linda. Can't you divorce him and let us be happy? Why should we be kept like this, snatching kisses on the sly when we might be married? He's making you miserable, although you keep a stiff upper lip. And it's making me miserable to see you treated like that. Can't you change your ideas? You know I'd do everything to make it up to you. Can't you bring yourself to it? For me, if not for yourself."