RGL e-Book Cover©

Based of a painting by Robert Delaunay (1885-1941)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based of a painting by Robert Delaunay (1885-1941)

Jacques Futrelle

FROM the mottled front of the Gare du Nord in the gathering gloom of dusk, Mr. John Smith took his first look at Paris; and so far as he could see, it didn't have a thing on Passaic, New Jersey. No fine frenzy of imagination was kindled by this initial glimpse of the wonder city of the world; he merely pondered how, in the absence of trolley cars, he could get down to the Rue de Main Street, or whatever they called it, where the hotels were. No unspeakable emotion, born of a long cherished dream come true, struggled within his soul; the thing uppermost in his mind was a deep seated craving for a fifteen minute séance with a beef stew that had lots of potatoes in it. It would require many beef stews, he figured, to fill the aching void caused by his eight-day ocean trip.

So, meditatively, for a time Mr. John Smith stood looking upon Paris with comparative eye. And the longer he looked the worse it was for Paris. The time-stained, weather beaten buildings across the street were not one-two-nine with the new brick block back home; the rain drenched square before him was neither wider, nor grander, nor in any way more calculated to arouse his enthusiasm than was the square in front of the church at Passaic-ave. and Grove-st. Trim lines of trees edged the curbs straight away ahead of him; but they would be dwarfs if set down beside the trees back home. Awnings were flapping in the wind which drove the mist before it; but the awnings back home always flapped when the wind blew. The restless throng on the sidewalk was neither more restless nor more dense than the Saturday night crowd on Main-ave. And trolley cars! In the absence of these, Mr. Smith was surprised that Paris had even electric lights.

Back home in Passaic, New Jersey, Mr. John Smith was assistant paying teller of a bank. In person he looked precisely like the assistant paying teller of a bank in Passaic, New Jersey. His hair was wiry, straight, and of a dingy black; his face the rugged, strongly limned countenance of one who shaves often and scrupulously; and he had the direct, straight-staring, unerring eyes of a man who lives for, by, and with figures, accustomed to seeing all that is writ and no more. He had never seen Niagara Falls, had Mr. Smith; but he knew to an ounce their capacity in horsepower if properly harnessed, and wondered why some one had not harnessed them. He had never crossed the placid bosom of the majestic Hudson River without wondering why it had not been filled in and cut up into city lots. Of course the ocean was all right; they caught fish in that.

There were faint lines of weariness in Mr. Smith's face now, and the straight-staring eyes were somber; not because of any disillusionment at his first sight of Paris, but because he was tired and sleepy and hungry He wanted to stretch his long legs in a real bed again after his eight nights of fitful slumber on a folding shelf in a stateroom. It was good to stand on something that didn't wabble, and it would be better to draw up to a table, beyond the sound of the heaving ocean, and eat. Heaving! Mr. Smith shuddered at the word.

These physical comforts provided, Mr. Smith would be prepared to rise and shake Paris in his teeth, as a terrier shakes a rat; for he had a purpose in Paris, did Mr. Smith, a purpose fixed, immutable, as was every purpose that ever laid hold of him. Nothing short of a purpose would ever have dragged him so far away from dear old Passaic. The somberness passed from the straight-staring eyes and there came a glint of steel into them as that purpose recurred to him. It made him impatient to eat, to sleep, and to be at it. So the first thing was to find a hotel. He reentered the great railway station and approached a porter.

"Say, son," he began affably, "I want a hack."

The porter stared at him and shrugged his shoulders. "Non compren' pas," he said.

"A hack, a cab, a buggy," Mr. Smith explained.

The porter shook his head.

"A vehicle, a wagon, a truck."

The porter appeared to be suffering intensely in his efforts to understand. His shoulders were squirming, his arms writhing, the agony was depicted upon every line of his face.

"Something with wheels on it, you know, that turn round and round," Mr. Smith elucidated patiently. "An oxcart, a herdic, a bicycle, a wheelbarrow—something to ride in."

"Non compren' pas!" the porter wailed helplessly. Oh, the pain and sorrow in his face!

"Well, don't take it to heart so," Mr. Smith advised kindly. "I want to ride, do you understand? In a—a dray, or an omnibus, or a taxicab, or—"

"Taxi! Oui!"

The fuse had burned to the powder, and the explosion came; the serenity of a summer's day settled upon the porter's face. He seized upon Mr. Smith's suitcase and gently but firmly led him around to his right, where he ceremoniously bowed him into an automobile.

The chauffeur appeared at the door for instructions.

"Now, son, we're getting somewhere," Mr. Smith remarked pleasantly. "I want to go to a quiet little hotel where no one will think I'm a Standard Oil magnate. How about it?"

The chauffeur looked at the porter, and the porter looked at the chauffeur, They both seemed to be suffering.

"Non compren' pas!" the chauffeur complained.

Mr. Smith sighed deeply and prepared to go into details. "A hotel," he said distinctly, "a place where you eat and sleep. A hash house, a beanery?"

The chauffeur stared at him helplessly, then turned to the porter, and they rattled unanimously. Mr. Smith sat patiently waiting.

"A boarding house, a soup kitchen?" he told them. "A hotel? Why, dam it! isn't there such a thing as a hotel in Paris? Hotel! H-o-t-e-l!"

"Non compren' pas!" the porter and chauffeur bleated in unison.

Mr. Smith drew pencil and paper from his pocket and printed a word on it in large letters. "Hotel!" he bellowed at them suddenly.

They took the paper and read it. "Hôtel!" They burst into song triumphantly. The storm had passed; peace had come.

"Sure, a hotel," Mr. Smith agreed. "Now, son, that you're hep, understand me that I want a cheap little place where I can get a room and bath and something to eat at about two dollars and a half per, on the American plan?"

"Oui, oui—Américain!"

They seized upon the word they understood and bore it aloft. Mr. Smith was satisfied, and when the porter's palm was outstretched thrust his hand into his pocket. He had been doing that steadily ever since he left Passaic—good old Passaic! He dropped a coin into the waiting hand, then lounged back in the automobile.

"And bang went ten cents!" he quoted. The taxicab wriggled out into the Rue de la Fayette and went scudding along toward the Place de l'Opéra. Mr. Smith looked out the window with growing interest and wonder. 'Twas a biggish sort of place, after all, was Paris. Passaic would have to look to her laurels! He was whirled past the Opera House and into the Rue de la Paix.

THE car stopped in the Place Vendôme. Mr. Smith glanced up at the sign above the door of a hotel and felt a cold chill start at the base of his brain and run down his spinal column, after which it ran up again. It was one word, "Ritz!" That was no place for a young man with a hundred and seventy-three dollars, who might have to stay in Paris for five or six weeks. He leaned out and spoke to the chauffeur.

"Drive on!" he directed.

"Hotel Ritz," the chauffeur informed him complacently.

"I know it," said Mr. Smith. "Drive on! Giddap! Cluck-cluck!"

The chauffeur came around to the door to make it clear to Monsieur. This was a hotel, the Hotel Ritz.

"On your way!" Mr. Smith expostulated. "Sick him! Vamose!"

Three or four pedestrians paused to listen. Monsieur did not understand. They undertook to assist him. It was the Hotel Ritz! They assured Monsieur upon their words as gentlemen and upon the sacred honor of France that it was the Hotel Ritz. The three or four grew to a dozen, and they assured Monsieur it was the Hotel Ritz. Oh, là là! Mr. Smith sat patiently waiting for the hubbub to stop; and it only grew.

"I said a cheap hotel!" he roared suddenly, and that mighty voice from Passaic extinguished the jabber about him as the windstorm extinguishes a candle. "This is no place for me! Giddap! Skiddoo!"

Whereupon the chivalry of France bowed low and begged Monsieur to believe them when they assured him it was the Hotel Ritz. A sergeant de ville nosed his way through, and Monsieur could take it from him that these gentlemen were telling the truth. He gave way to an imposing individual who came out of the hotel, wearing more uniform than Napoleon ever saw. Mr. Smith thought he was the Chief of Police; but he was only the head porter, and he added his voice to the hubbub. Mr. Smith looked out upon the growing mob with amazement in his straight-staring eyes.

AND then came to him faintly the voice of an angel, an angel from the United States, who seemed to be slightly amused. The crowd fell back respectfully, and a young woman stood before him, a tailor made young woman, trig and trim and charming. Her blue eyes were alight with understanding, and a smile tugged at the corners of her rosy mouth.

"Can't I assist you, Mr. Smith?" she queried, and the sound of his own language stirred a responsive chord deep in Mr. Smith's heart. "There has been some mistake, I am sure. Perhaps I can right it for you?"

"Thank you, ma'am," said Mr. Smith humbly, and it didn't occur to him to wonder that she knew his name. "I told the driver to take me to some cheap American plan hotel, and he didn't seem to understand. If you'll tell him, please, ma'am, I'll be much obliged."

"Certainly." With perfect gravity the girl turned and spoke to the chauffeur. After a moment he touched his cap and climbed back into the seat. The machine whirred and started to move.

"Thank you, ma'am." Mr. Smith said simply.

The girl smiled, nodded brightly, and entered another automobile which stood at the curb. Looking back, Mr. Smith saw her car swing about the Colonne Vendôme, and then his own car turned into the Rue de Castiglione and she was lost.

"Why, Edna, how could you thrust yourself into a crowd like that?" a middle-aged woman inquired of the girl reprovingly. "It was not—"

"Why shouldn't I have done it, Aunty?" the girl interrupted. "Mr. Smith was a passenger on the steamer with us, and shipboard acquaintances are privileged to help one another when one is in trouble. And he was in trouble, wasn't he?"

She laughed a little, and then the mood passed and she sat for a long time staring out the window with sad, thoughtful eyes.

HERE and there across the Seine some prodigal giant has flung a handful of glittering stars in parallel arches; and these are bridges. As Mr. Smith's taxicab spun through the Garden of the Tuileries, and over one of these, where looking out he caught the reflection of ten thousand lights in the rippling waters, he was reminded of the bridge down near the orphan asylum back home in Passaic. It gave him a comforting sense of nearness to things he knew, and he found it good. Paris was looking up; there was nothing to it.

Then he was whipped round a corner, and as he struggled to steady himself he caught the words "Rue Bonaparte" on a street sign under the full glare of an electric light, and sat up straight in his seat, aroused by some swift recollection. Rue Bonaparte! Here was a thing that he had momentarily forgotten, perhaps a tangible starting point of a search that might take weeks, given over into his hands by sheer luck. There had been a time a few years previously when, in his capacity of private secretary, he had been called upon to write that phrase at least once a week for many months. And now here was the place, the street itself, rolling away under his feet!

There was a quick, tense tightening of his lips, and a narrowing of his straight-staring eyes as the thought the words had aroused grew in his mind, and he was just about to stop the taxicab, when he felt it slowing, and it came to a standstill half a block farther on. He stepped out and glanced up curiously at the six-story building towering above him. Yes, it was precisely as he expected, as he knew it ought to be, the Maison de Treville, which happens to be a quiet, eminently respectable place in the Latin Quarter, opposite the Beaux Arts. It was something more than a pension and not quite a hotel; but anyway a respectable place to live. Mr. Smith had known this for years; but it had slipped his memory.

He turned to the chauffeur with a mouthful of questions; then, suddenly remembering the disaster that had befallen his previous attempts at conversation with this individual, restrained himself and turned into the entrance. From behind the desk in the lobby a young man with delicately waxed mustache superimposed upon an ingratiating smile, greeted him. Mr. Smith, wholly absorbed in the things he was remembering, glared at the young man with a cold glint of steel in his eyes.

"Something tells me, son, that you don't speak English either?" he remarked questioningly.

"Something tells me, son, that you don't

speak English either," remarked Mr. Smith.

The amiable young man's eyebrows disappeared into his hair, and the smile widened. "Pardonnez-moi?" he queried.

"I'd have bet eight dollars you didn't," Mr. Smith continued in calm resignation. "Well, anyhow, I want a room—a room. Are you next? And a bath—a washee-washee place. And meals—food, eats. Do you get it?"

The clerk shrugged his shoulders and bowed and scraped and smiled. These Americans! Oh, là là! They are that droll! The smile wavered a little under the steady scrutiny of Mr. Smith's straight-staring eyes; for he was thinking of other things, things that came to him afresh with the words "Rue Bonaparte."

"By the way, do you happen to know the name W. Mandeville Clarke?" Mr. Smith continued. "W. Mandeville Clarke? He isn't stopping here?"

"Qu'est-ce que c'est!" queried the clerk.

"W. Mandeville Clarke?" Mr. Smith repeated distinctly. He picked up a slip of paper and wrote the name on it, then passed it to the clerk. "W. Mandeville Clarke!"

"Oui! M. Clarke!" the clerk burst forth rapturously. Here was something he could lay his tongue to! "M. Clarke! Américain!"

"You don't know any more what I'm talking about than a jaybird," Mr. Smith declared unemotionally. "My name isn't Clarke; my name is John Smith. I'm looking for a man named Clarke."

"M. Clarke! Oui, oui!" The clerk clung tenaciously to the thing he understood.

Mr. Smith leaned over, pulled the slip of paper from the clerk's reluctant fingers, tore it into four pieces, and dropped them to the floor. "Forget it!" he advised. "I wanted to know if Clarke was stopping here, and I stand a fine young chance of ever finding out from you, son. And, understand, my name isn't Clarke; my name is John Smith. Gimme that book!"

He jerked the register from beneath the hand of the astonished clerk and signed his name in it with a large flourish—just like the assistant paying teller of a bank in Passaic, New Jersey.

"Now, never mind Mr. Clarke," he told the clerk. "We'll fight that out to-morrow. The thing I most want in the world is a room—a room with four walls and a bed in it—a bed—sleep." Mr. Smith made a pillow of his two hands, laid his weary head on it, closed his eyes, and snored.

The clerk beamed his delight. "Sommeil! Oui!" he exclaimed.

"If that means sleep, you're on," Mr. Smith agreed with a sigh of satisfaction. "Now, eats!"

He dexterously applied an imaginary knife and fork and rubbed his stomach with feigned delight.

"Manger! Oui! Oui!" There was the light of perfect understanding in the clerk's eyes.

"Now, son, you're showing symptoms of human intelligence," Mr. Smith remarked admiringly. "And now a bath—a swim—the Big Splash. Are you hep?"

Whereupon Mr. Smith laved his face and hands in the ambient air and splashed it all over the shop, after which he dried himself. The little clerk was delighted. Monsieur was an artist! There was nothing better in the Folies-Bergère! In other words the great Coquelin himself wasn't deuce high!

"Baigner!" he elucidated. "Oui, oui!"

And so, five minutes later, Mr. Smith found himself safely bestowed in a clean, sweet room five flights up, surrounded by his suitcase. Then came a small waiter with a large tray of food, and, sans collar, sans coat, Mr. Smith set himself to fill a long felt want. He did well.

WHETHER Paris has the most perfect police system in existence because it is the wickedest city in the world, or whether it is the wickedest city in the world because it has the most perfect—well, anyway, they do it differently in Passaic. In Paris the police have succeeded in establishing a cycle of tattletales, an endless chain which makes every man a spy upon his fellows, and the effect is a marvelous, albeit an unpleasant, system of espionage. That is, it is unpleasant when one comes to think of the manner of its existence; for its operation is noiseless, unostentatious. It would not be possible in any other part of the world.

Being blessed with such extraordinary facilities, Paris keeps close watch on the casual stranger, if for no other reason than that it keeps the intricate machinery in motion. Paris is not only always willing, but glad, to lend assistance to the police of any sister city of the earth.

So, when a cable despatch came from a private detective agency in New York asking the Paris police to locate one W. Mandeville Clarke, Paris doffed her hat and went to work. It was not surprising, therefore, that while Mr. John Smith of Passaic was peacefully snoring five flights up in the Maison de Treville, an agent of the police, M. Rémi, not without fame in his own calling, should appear in the office down stairs and make certain inquiries of the clerk.

Dark insinuations underlay his manner of questioning, and the beady black eyes of him scared the amiable smile out from under the little clerk's waxen mustache.

"M. Clarke—W. Mandeville Clarke?" the sleuth questioned.

Yes, the clerk remembered the name; he had heard it earlier in the evening; indeed, it had been written upon a slip of paper and handed to him, then snatched out of his hand—so—and destroyed.

"Ah!" It was a long aspirated expression of relief from M. Rémi; the Rémi reputation threatened to be crowned with new glory. "Ah! You will be so kind as to go on?"

The little clerk leaned forward dramatically. "I have reason to believe M. Clarke is here in the hotel even now," he declared. "I will go further, Monsieur. I will say I am positive he is here!"

"Ah!" The cunning black eyes were alive as flames. "Your reasons. Monsieur?"

"He came here, an American, early in the evening, and his conduct was suspicious in the extreme," the little clerk ran on volubly. "He used strange American words, and a great many of them, although he must have known that I could not understand—I, who speak only the language of my beloved France."

"I am awaiting details, Monsieur," remarked M. Rémi.

"When first he came he repeated the name W. Mandeville Clarke many times, and finally. Monsieur, I came to know that he was introducing himself. Ah! You must give me credit for the great acumen! I did not fully comprehend this, Monsieur, until finally he wrote the name upon a slip of paper; then, apparently realizing that he had committed a blunder and betrayed himself, he snatched the paper from my hand—so—,tore it into bits, and cast it away. It must be here even now."

Together they pounced on the four bits of paper which had been knocking about the floor all night, and patched them together again. It was perfect! W. Mandeville Clarke! Little cries of satisfaction escaped them as the name grew beneath their deft fingers, and when all was done they shook hands mutely, admiringly.

"Then, when he had torn up and cast away this so precious bit of paper," the clerk went on breathlessly, "he seemed not himself, and again he said many strange words. Then he seized the register—so—and wrote upon it another name."

"What name?" demanded the sleuth keenly.

"See for yourself, Monsieur."

He spun the book round on the desk, and M. Rémi read therein the large written:

John Smith, Passaic, N.J.

FOR a time M. Rémi looked, then there came into his beady black eyes a supercilious light, and finally he permitted a sneering smile to curl the corners of his mouth. "It is a strange thing, Monsieur," he told the little clerk easily, from the depths of his infinite wisdom, "that whenever and wherever an American is arrested or is threatened with arrest he gives his name as John Smith. If there had been any doubt as to this—er—M. Smith's attempt to hide his true identity, the mere fact that he signed the name John Smith would have tended to dissipate that doubt. A clumsy thing to do, Monsieur! He is a tyro, a bungler!"

"Oh, là là—là là là!" the clerk exclaimed. " A child in the hands of so distinguished a man as M. Rémi!"

The sleuth permitted the compliment to pass unheeded and produced from the depths of his cavernous pocket a large notebook. Fascinated, the clerk watched him as he deliberately turned the pages. Then:

"This, M.—er—er—Smith," the detective inquired with deep meaning,—"this M. Smith—he wears the full, square-cut beard?"

The eager anticipation of the clerk's face was wiped out as by the brush of a painter—a house painter.

"No, Monsieur!" he exclaimed, and all hope had fled. "I must tell you the truth. He is of the clean shave."

M. Rémi did not seem to be particularly cast down at this chilling bit of information; on the contrary the sneering smile came again to his lips, and there was something akin to pity in the depths of his black eyes. "There are razors in the world, eh, Monsieur?" he queried quietly.

"Out, oui, oui! Magnificent!"

M. Rémi took his time about the next question. "His hair is gray? Almost white?"

"His head is like the raven. Monsieur; but," and the little clerk poked the detective in his distinguished ribs, "there are hair dyes, eh. Monsieur?"

M. Rémi admitted it with the strange feeling of having lost something. His voice grew stern, accusing. "He is tall?"

"He is tall. Monsieur—so great tall."

"Weighing about one hundred and eighty pounds?"

"Oui, Monsieur."

"Powerful of physique?"

"Of the grand physique."

M. Rémi closed the book and replaced it in his cavernous pocket with an air of finality. "That is all, Monsieur," he said simply.

"You will arouse him and take him away with you now?" the clerk queried eagerly.

"I have no orders to arrest him, Monsieur." M. Rémi explained. "My orders were only to locate him and keep him under close surveillance."

Oh, là là! Here was disappointment indeed. The little clerk's waxen mustache began to droop. "But what has he done. Monsieur?" he demanded excitedly after a moment. "Is he the robber, the murderer? Is it safe to let him remain in the house? You must tell me, Monsieur!"

"He will remain here undisturbed," M. Rémi declared positively. "Who he is and what he is I may not tell you."

There were four reasons why M. Rémi could not tell. The first was he didn't know, and the other three are of no consequence.

Meanwhile, Mr. John Smith of Passaic, New Jersey, wrapped in the utter innocence of slumber, dreamed lightly of the voice of an angel—an angel from the United States—which came to him vaguely through a babble.

IN the midst of his shaving, Mr. John Smith paused and from the high-up windows of his room looked down meditatively on the sea of mist that veiled Paris. Far away, a snow-white island in the murk of morning, glistening spotlessly under the rays of a pale sun, was Sacred Heart; to his left was Eiffel Tower, that thin, spidery structure that thrust its flagpole straight toward the stars. What a fine young shot tower that would make back in Jersey! As the mists began to lift he could trace the serpentine sweep of the River Seine, winding from a point almost at his feet away, away, and disappearing like a silver ribbon in the distance—just like the dear old Passaic River! In front of him, at the far end of a trio of arched bridges, was the vast roof of the Louvre; it reminded him of the roof of the rubber works back home. And the Garden of the Tuileries! It made him almost homesick for another glimpse of First Ward Park.

Homesick! He shook off the shadowy suggestion; for there was work to be done in Paris, tedious work, the work of finding a man named Clarke, W. Mandeville Clarke, and his reward was to be the exquisite delight of pounding Mr. Clarke to a pulp. After which they would sit down calmly and discuss two or three matters of moment to both of them. He had come all the way to Paris to do this, and this he would do! It had never occurred to him that Clarke might be hopelessly lost in the labyrinthine wildernesses of the city, or that he might not be in Paris. He would find him, because it was meet and proper that he should find him, and Mr. Smith was blessed with a firm belief in the eternal justice of things.

He bared his great right arm and, looking down on it complacently, fell to imagining how Clarke would look when be had quite finished with him. The mental picture he conjured up pleased him so he smiled, and smilingly he finished shaving. After which came breakfast. Not a puny little thing of coffee and rolls, but breakfast with a couple of chops and three or four eggs, and innumerable rashers of bacon. The waiter, who spoke eating-English, allowed his eyes to grow round and rounder as Mr. Smith ordered, and he stood by in a sort of trance as Mr. Smith ate. These Americans! What gormands they were! No wonder zey aire zo beeg and zo husky!

THESE preliminaries disposed of, Mr. Smith planted his hat upon his head and started out to get a toothhold upon Paris. It was of no particular moment to him that, as he passed through the office, the new clerk on duty glanced at him suspiciously and greeted him with a servility that was wholly out of keeping with his station. It was of no particular moment that the clerk didn't speak English,—Mr. Smith looked at him once, and knew that,—because, when he had exhausted the hotels where he could make himself understood, he would hire an interpreter and do the others.

It was of no particular moment to him that the cunning black eyes of a loiterer in the lobby swept his rugged face in one comprehensive glance and took particular note of the color of his hair, after which the owner of the eyes leisurely strolled out.

Maison de Treville, Rue Bonaparte! The combination of words had aroused a cameo-cut recollection in his mind, because once, half a dozen years ago, that had been the home in Paris of Miss Edna Clarke, the daughter of the man he sought. It was odd that he should be stopping at the same place, odd; but upon reflection overnight Mr. Smith could find nothing in it, save its oddity. Miss Clarke had lived there for nearly two years with a chaperon while she was completing her education; but there seemed to be no reason why either she or her father should be known at the Maison de Treville now. He had been convinced by the night clerk's manner that Clarke was not living in the hotel, and, anyway, if he found it necessary, he could go into the matter further with the aid of an interpreter.

Edna Clarke! She must be twenty-four or twenty-five years old now, and for no reason he found himself wondering what she might look like. Once upon a time he had seen a little picture of her, one of a group of laughing girls on a terrace at Versailles, and he had wondered how anybody that far away from Passaic could laugh. The picture had lain for a day or so on Clarke's desk; that same desk where Clarke had practised his knavery and—His teeth closed with a snap and there came an unpleasant glare into his straight-staring eyes as he strode into the street and turned toward the river. From his cursory view of Paris at his windows it had seemed that all the big buildings were across the river, and where all the big buildings were the big hotels should be, and skulking in one of the big hotels somewhere, under some name, was W. Mandeville Clarke.

SMITH was halfway across the Pont du Carrousel, which so reminded him of the bridge down near the orphan asylum back home, deep in his own thoughts, when he was brought to an abrupt halt by a man who met him face to face, a shrewd-eyed individual who planted himself directly in his path.

"What is your name?" the stranger demanded suddenly in English.

Mr. Smith paused and regarded him questioningly for a moment. "Smith—John Smith," he replied at last, curiously. "Why?"

"Where do you live?" The second question came in the same curt, businesslike tone.

"Passaic, New Jersey," replied Mr. Smith. "What's the answer?"

Without another word, with not even a word of thanks, the stranger passed on and was lost in the throng on the bridge. The incident struck Mr. Smith as curious, nothing more, and a minute later, in thoughts of more importance, he had forgotten it.

Then began for him a systematic, wearying round. He didn't know, and it probably wouldn't have disturbed him if he had known, that M. Rémi was trailing him tirelessly, accurately, into and out of every hotel he entered. His questions at each place took the same form: "Do you speak English?" In the event of an answer in the affirmative, the conversation prospered, and there came other questions: "Is W. Mandeville Clarke stopping here? Has he been here? Do you expect him? Is there any American or Englishman with a full gray beard and white hair stopping here, anyone about my size?" In the event of a negative answer to the first question, the conversation ended abruptly, and Mr. Smith put the hotel on his blacklist, to be probed later on by an interpreter.

AT the Hotel Continental there came a pleasant break in the weary monotony of his search. He put the usual questions to the clerk. Yes, he spoke English, and he spoke it with an intonation that made Mr. Smith's heart go out to him. No, Mr. W. Mandeville Clarke was not there; he had not been there; they didn't expect him. There was no full bearded, white haired American or Englishman stopping in the hotel, no one about Mr. Smith's size. Mr. Smith was turning away.

"From the United States?" the clerk queried affably.

"Passaic, New Jersey," Mr. Smith boasted.

"Waterbury, Connecticut," said the clerk.

The kindred of country brought Passaic and Waterbury hand to hand in a long, hearty clasp, and Mr. Smith didn't understand why, but there seemed to be a slight lump in his throat.

"Funny thing," the clerk went on after a moment. "There was a young woman in here just a moment ago inquiring for Mr. Clarke. She was from the States too, I imagine—a slender girl dressed in black, rather tall."

Mr. Smith studied the clerk's face with questioning, interested eyes. "You don't happen to know what she wanted with him, do you?"

"No, she didn't say. She seemed to be much distressed about something."

"She didn't leave her name, or her card, did she?"

"No." There was a moment's pause. "If you'll let me have your name and address, and Clarke comes along. I'll let you know," the clerk went on obligingly.

"Bully!" Mr. Smith exclaimed heartily. "My name is John Smith. I'll write my address, because I can't pronounce it."

So a slip of paper passed, and with a word of thanks Mr. Smith went his way.

He had hardly vanished through the courtyard into the Rue de Castiglione when M. Rémi appeared before the clerk with an eager glitter in his beady black eyes.

"You will give me at once, Monsieur," he commanded, "the slip of paper which the American handed to you just a moment ago."

The clerk needed no introduction to this man; the type was common. He passed over the slip of paper without a word, and M. Rémi devoured it with his eyes. It bore the simple words:

John Smith,

Maison de Treville,

Rue Bonaparte.

IT was mysterious—most mysterious! M. Rémi puzzled over it for a minute or more, then with keen, accusing glance turned to the clerk. "You will inform me, Monsieur," he commanded, "of the exact conversation you had with this—this M. Smith."

The clerk laid the whole matter before him. The while spidery wrinkles grew in M. Rémi's brow. At its end M. Rémi hastened away, leaving the clerk to imagine strange things of this big countryman of his, things that were not wholly complimentary. Mr.

Smith would have been amazed if he had even an inkling of what Waterbury, Connecticut, was thinking of Passaic, New Jersey.

MR. SMITH had just turned into the Place de l'Opéra when, for the second time, he was halted by the abrupt appearance before him of a man who blocked his way. Mr. Smith stopped, thrust his hands into his pockets, and looked him over. He was the same type of man, precisely, as the one who had stopped him on the Pont du Carrousel,—who, in a general sort of way, was a twin of M. Rémi,—and something told Mr. Smith he was going to ask the same questions.

"What eez your name?" demanded the stranger curtly. Yes, the same question—in worse English.

"What's it to you?" Mr. Smith queried belligerently.

Aha! He was not M. John Smith any more; he was M. Watts Ittooyu! It must be a Japanese name! Ze huge Américain must take ze police of la belle France for ze grand stupid! Oho!

"Where do you leeve?" came the question.

"At the corner of the United States and two o'clock," Mr. Smith declared hotly. "Now, look here, son, I don't know why you people in Paris stop a fellow and ask his name; but it's none of your business, and the next one who does it will get a good swift poke in the jaw."

Mr. Smith stalked into the lobby of the Grand Hotel with a grim expression on his face, which softened instantly into mild interest as he came face to face with a tall, slender young woman gowned in black and heavily veiled, coming out. She started a little at sight of him, hesitated a scant instant,—he thought she was going to speak,—then passed on hurriedly. There was something vaguely familiar in the trim figure, the walk, the tilt of the head, and he paused to look after her a moment. Whatever he thought of her was lost in the throes of his verbal wrestlings with a clerk who boasted that he spoke English and understood United States.

THE first day's search ended fruitlessly for Mr. Smith, but rich beyond the most optimistic dreams to the sleuths of Paris who were seeking W. Mandeville Clarke. M. Rémi listened to the reports of the men who were assisting him, and his mental convolutions were weird in the extreme. He sent them away and sat down to try to adjust all the odd facts in his possession.

John Smith, alias Watts Ittooyu, was W. Mandevilie Clarke. He was big enough, the rugged lines on his face made him look old enough, he kept clean shaven with the most scrupulous care, and his dingy black hair bore every indication of having been newly dyed—badly dyed. But why should W. Mandevilie Clarke set himself to search the hotels of Paris for W. Mandevilie Clarke? Why, when confronted the second time by one of M. Rémi's assistants, did he give that strange name, Watts Ittooyu? And that strange address—the corner of the United States and two o'clock? Who was the mysterious veiled woman in black who was also searching for M. Clarke? Was she a confederate? There was some deep laid plot somewhere, and seeking it the French sleuth acquired a headache, which he treated with many oversweetened Martinis. Result, more headache!

ON the second day Mr. Smith planned to take the Arc de Triomphe as a center and revolve around it. At his first point of inquiry, the Hotel Carleton in the Champs Élysées, he encountered for the second time the veiled woman in black. She was standing at the desk with her back toward him as he entered, talking in French with the clerk in charge. She finished and started away.

"Do you speak English?" Mr. Smith began monotonously.

"Yes, Monsieur, I speak him quite well," replied the clerk.

"Do you happen to have with you a man known as W. Mandevilie Clarke?"

The clerk glanced involuntarily at the veiled woman, who turned quickly, inquiringly. At sight of Mr. Smith she became rigid where she stood, listening, listening!

"No, Monsieur. He is not here."

"Has he been here? Do you expect him?"

"He is not here. We do not expect him."

"There's no American or Englishman with a full beard and white hair here? No man about my size?"

Again the clerk glanced at the young woman, who, with fingers writhing within themselves, stood motionless half a dozen feet away.

"No, Monsieur," replied the clerk at last. "We have them wider and shorter, and longer and thinner; but none of your size."

Following the clerk's glance, Mr. Smith turned and recognized the veiled, woman with a sort of start. Her eyes met his squarely for a fraction of a second; then she turned and went out. A minute later he went out in the same direction. She was standing beside a taxicab at the curb waiting. He knew she would be. She faced him flatly, almost defiantly.

"I am not mistaken?" she asked in a tone so low he could just hear her. "This is Mr. Smith?"

"Yes, ma'am." Mr. Smith thought at first he knew the voice, knew it as one he had heard before; but there was some note in it that made it seem strange. He wondered if she was going to ask where he lived.

"You don't—don't happen to know who I am?" she went on, apparently with an effort.

"No, ma'am."

She sighed a little; it might have been relief. "You are looking for Mr. Clarke, I believe?" There was a tense, eager note in the girl's question, a suggestion of fear. Her face was perfectly pallid behind the kindly veil, and her small fingers gripped her palms mercilessly.

"Yes, ma'am," Mr. Smith replied frankly. "You don't happen to know where he is, do you?"

"May I ask—pardon me if my question seems impertinent—may I ask why you are looking for Mr. Clarke?"

Mr. Smith thoughtfully stroked his chin. "It's a little personal matter, ma'am," and his voice hardened, "a little matter between us. If it's just the same to you, I'd rather not tell you."

The girl caught her breath sharply, and when she spoke again there was abject terror in her manner. "I should not have asked, of course," she apologized quickly, falteringly. "You—you come from the United States to find Mr. Clarke?"

"Passaic, New Jersey; yes, ma'am."

"And when you find him?"

Mr. Smith's straight-staring eyes grew steely, and there was a glint of danger in them; his powerful hands worked spasmodically, his white teeth were locked together. "When I find him!" he repeated grimly. Then quietly, "I'd rather not tell you, ma'am."

For an instant she stood staring at him, and twice she made as if to speak; then suddenly, silently, she turned and entered the taxicab. The car jerked and went speeding away up the Champs Èlysées. For a long time Mr. Smith stood gazing after it blankly, wonderingly.

SOME one has said that the corner table of the Café de la Paix, that table on the sidewalk, precisely at the intersection of the Boulevard des Capucines with the Place de l'Opéra, is the exact center of the earth. When he dropped into a chair at that particular spot. Mr. John Smith didn't happen to know that he occupied so important a geographical position: he only knew that this famous outdoor place, with its thin-legged tables and unsubstantial chairs, was something like Terry Maloney's Winter Garden back in Passaic, and that was enough. He was aweary of limb, battered by disappointment, and there was creeping over him resistlessly that longing for home which at some time is the heritage of every man who travels.

For just a week Mr. John Smith had been tramping up and down Paris, cut off as effectively from home and countrymen as if he was in a dungeon, asking questions, always the same questions, listening to the meaningless, volatile babblings about him, and pondering moodily upon the hundreds of unused handshakes in Main-ave. back home. Not once had he met an American, save the clerk in the Hotel Continental. He had not seen the mysterious veiled woman again. There came a time at last when he felt he couldn't stand it any longer, and he dropped into the Continental to shake hands with Waterbury. Connecticut. But some change had come there. The clerk regarded him with frigid eyes, in which lay a shadow of suspicion.

"You haven't come across Clarke yet?" Mr. Smith inquired.

"Don't know a thing about him," replied the clerk tersely. That was all.

And once, in his great loneliness, he had paused to watch a child at play in the Garden of the Tuileries, a rosy-cheeked little chap who was whipping a top.

And he had spoken to the child. The answer was an incomprehensible jumble of sounds—just sounds.

Even the children in Paris spoke French! He had moved on wearily, and as he went a shrewd-faced man with beady black eyes—M. Rémi had come up and inquired of the child what the strange American had said and what had been the answer.

By noon of the seventh day Mr. Smith had exhausted those hotels where he could make himself understood, and now he had dropped down into a seat in the Café de la Paix to plan a continuance of his search, with the aid of an interpreter. Disappointment had been added to disappointment as he had gone on with not one clue; but the bulldog determination was in no way dulled, his purpose had not wavered. It had never occurred to him to give in—to quit. It never would occur to him while W. Mandeville Clarke remained to be found.

ACROSS the Place de l'Opéra from the Café de la Paix is a large sign in bold United States sort of letters, the sign of a great Chicago newspaper. Mr. Smith discovered it now for the first time, and the severe lines in his rugged face softened a little. It looked so homey and comfortable and United Statesy that it made him feel hungry all over, a hunger that took the form of an insane desire to see a United States flag, and to shake a United States hand, and to eat a United States pie—all of it, from upper crust to indigestion. Pie! Paris wouldn't be so bad if there was pie to be had. Chestnut fed Jersey pork and pumpkin pie! And perhaps just a smack of applejack, real, undiluted Jersey lightning!

He wondered if it was to be had.

A waiter came and inquired what Monsieur would be so pleased as to have, inquired in the lisping English that nearly every waiter in Paris speaks. How could he be so honored as to serve Monsieur?

"Say, son," queried Mr. Smith. "I wonder if by any chance you know what applejack is? Jersey lightning?"

"Applejack?" the waiter repeated painfully. "Jairsey lightning?"

"Applejack—it's a drink." Mr. Smith elucidated. "If you can find me a small glass of it—"

"Apple?" the waiter pondered. "Zat eez ze pointin'. Jack—zat eez ze Jacques in French, and Jacques eez ze James in English. Did it? Zerefore vat you want eez ze apple of ze James to drink? Eez it not so?"

Mr. Smith looked at him in amazement. "Oh, rats! If it's that much trouble, bring me beer," he directed.

Perched there in the center of the world, Mr. Smith meditated upon many things over his déjeuner,—dinner back in Passaic, regaling his drooping soul ever and anon by another glance at that wonderful sign across the way, the sign of a Chicago newspaper. He had never been to Chicago; but he loved it now.

He would go over to that office when he had finished, and perhaps some one there an American, oh, joy!—could give him some information as to where he might get an interpreter.

And, as he considered it all with rising spirits, there came to him indistinctly from a table a dozen feet away a few words in English—good United States English. The sound of that voice brought a quick, tense expression to his face and a spasmodic gripping movement to his hands. He knew it, knew it despite a certain whining quaver that had never been there before. He brushed the crumbs from his knees, folded his napkin carefully, à-la Passaic, paid the waiter, and rose. He had found Clarke!

He turned in the direction whence the voice had come, and, as yet unnoticed himself, stared, stared with frank surprise in his face. It was Clarke, all right—he knew the commanding, gleaming eyes of him—but a different Clarke, a Clarke minus the square-cut beard he had always worn, a Clarke whose head had been stripped of its glory of white hair, a Clarke who had shrunk from the robust, ruddy man he had known to a mere skeleton of himself, a Clarke with thin, yellow face and colorless lips; but Clarke it was—the man he had been seeking!

Mr. Smith strode straight toward him through the web of spidery tables and chairs, heedless of all else in the world, heedless even of the sudden appearance at his side of a strange man who said something to him in English. The slight commotion attracted Clarke's attention, and there, while still half a dozen feet separated them, the eyes of the two men met. Clarke's thin face went white beneath its sallowness and, leaning heavily on the table in front of him, he struggled to rise. It was an effort for him, a desperate effort; but he came to his feet at last and his burning gaze fastened itself upon Mr. Smith.

Some one laid hands on Mr. Smith's arm. He shook them off and took another step forward. Then, and not until then, he became conscious of the fact that Clarke was not alone. There was a young woman with him, a girl he knew, the girl who had directed his cab to the Maison de Treville on his first day in Paris, a girl in poise and in figure and in carriage strangely like the mysterious veiled woman in black. There was abject terror in her blue, wide opened eyes, a blanching of the rosy face, an involuntary movement of appeal in the slim, white hands appeal to him!

"Keep your seat. Edna." Clarke commanded in the thin, whining voice of a man who is ill, desperately ill. "There will be no scene."

For a second time Mr. Smith attempted to shake off the restraining grip on his right arm; but this time the encircling fingers closed like steel, and again he was conscious of some one mumbling in his ear—something that seemed to be of no consequence in the blinding anger that suddenly possessed him. He wanted to sink his fingers into the throat of this man, he wanted to smash that sickly yellow face, he wanted to scream the bitter rage that gripped his heart. And yet, looking into the troubled, pleading blue eyes of this girl, eyes that commanded with unspoken urgency, he stood silent, rigid.

Finally, after a great while, it seemed, reason came back to him, and vaguely he made out something that was being said in his ear:

"M. Clarke, you are my prisoner!"

CLARKE! Yet it was to him. John Smith, that the words were addressed! He turned to face the man who had spoken, the man who clung to him now with a grip of iron. It was the inquisitive stranger who hail asked his name that day on the Pont du Carrousel.

"Come along with the quietness, Monsieur!"

"What for? Mr. Smith demanded curiously.

"By order of the Prefect of Police."

"But my name isn't Clarke," Mr. Smith protested. "My name is—"

"W. Mandeville Clarke," interrupted his captor, "alias John Smith, alias Watts Ittooyu. You are my prisoner. You will come along with the great quietness."

"W. Mandeville Clarke, alias John Smith,

alias Watts Ittooyu. You are my prisoner.

Mr. Smith riveted his gaze upon the face of the real Clarke, and his mind, usually slow moving, whirled with the flood of things to be considered. He wasn't Clarke, of course, but if he exposed the real Clarke, and the real Clarke should be taken prisoner, it would bring chaos. Clarke must remain free, even at the temporary cost of his own freedom! It would he easy, once Clarke had opportunity to escape, to prove himself to be the John Smith he claimed to be, and he would he released. Then would come his reckoning!

His eyes shifted for an instant to the face of the girl, and some strange, subtle message passed between them. She had not spoken; yet she too seemed to understand, and the pleading, wistful eyes commanded him to do the right thing which happened to be at the moment submission to arrest!

"Oh, very well, Cap," Mr. Smith remarked at last, quietly, slowly, "as long as you know I'm Clarke, I don't suppose it will do any good to deny it. You fly cops in Paris are wonders, aren't you?"

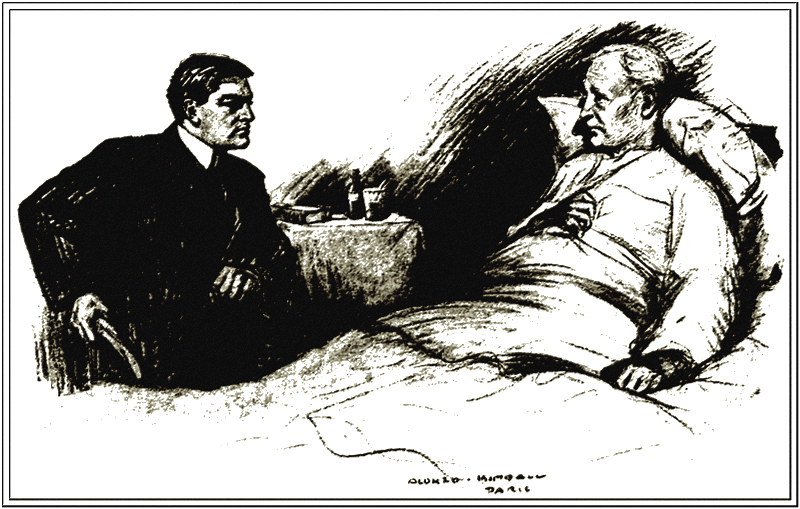

WITH one of his wasted hands clasped in the cool, caressing fingers of his daughter, and with her plump, rosy cheek pressed tenderly against his own, withered and yellowed by a long, dragging siege of typhoid. W. Mandeville Clarke slept. It was a sleep of utter exhaustion, an exhaustion following closely upon the maelstrom of speculation and apprehension aroused by that unexpected encounter with Mr. John Smith in the Café de la Paix. Smith, of all men! What was he doing in Paris, so far away from his wicketed window? Why had he been arrested? And why had he submitted to arrest under the name of Clarke, with hardly a protest?

There was only one answer, of course, and that answered only part of the question: The disappearance of the United States bonds from the bank vault had been discovered. An order had been issued for his, Clarke's, arrest on a charge of having made away with those bonds. That order had been turned over to the police of Paris for execution, and they had blunderer! But how had they blundered? How was it possible to mistake Smith for Clarke? And why had Smith not delivered over to the arresting officer the real W. Mandeville Clarke, who was there under his very hands? It couldn't have been that Smith hadn't recognized him; the blazing, straight-staring eyes left no room for doubt on that score. Then why—why?

Pondering these things, aghast at the hideous possibilities that paraded before his distorter! vision in garish disorder, certain of nothing and fearful of all, Clarke had been lulled into uneasy slumber by the softly musical voice of his daughter, who talked of all things in the world save the strange meeting in the Café de la Paix.

Mr. Smith had been led away a submissive prisoner, and immediately he had gone Edna had hurried her father into a taxicab and they had been driven here—here to this shabby little apartment in the Rue St. Honoré where she had found him. where he had been quartered for weeks, and where by force of indomitable will and splendid physique he had conquered his illness.

FOR an hour or more after he had dropped asleep the girl sat beside him, motionless, vigilant, sensitive to his least movement, her clear blue eyes clouded by terror of some incomprehensible danger which threatened to overwhelm them. She had asked no questions; but a thousand were hammering insistently for answer. Why was her father, W. Mandeville Clarke, president of a bank and a financial power at home, skulking here in a pitiful little apartment under the name of Charles Roebling? Had there been some crime? She shuddered at the thought. If there had been no crime, why the necessity of this concealment? And who was this huge, hulking American, this so called John Smith, who, knowing Clarke, had submitted to arrest with scarcely a word of defense?

Her father—perhaps he was a thief! He had left home suddenly with the bare, bald statement that he was going to Paris, and once there he had utterly disappeared. Weeks and weeks had passed; then, tormented by an unnamed fear of some ghastly thing like this, she had come to find him. She had found him through a clue furnished by a friend of the family, found him just recovering from typhoid fever. If her father was a thief, then John Smith—John Smith—he was probably a detective! That was the only inference she had been able to draw from his answers to her questions that day in the Champs Èlysées. But, on the other hand, if he was a detective, why had he permitted himself to be arrested as W. Mandeville Clarke?

After awhile she detached her slim fingers from her father's feeble grip and rose noiselessly. For a minute or more she stood staring down on the emaciated frame of this man who was so much to her, who was so dependent upon her now in his helplessness, who was so near to her and yet so isolated by the pall of mystery which seemed impenetrable. Then suddenly there came a blinding, blurring rush of tears and she crept silently from the room.

The door squeaked faintly as she closed it; but, as slight as it was, the noise aroused Clarke. His feverish eyes opened wide and he sat up straight in bed. The bonds! He had dreamed of them, and fear for their safety had been born in that dream.—a strange, vivid vision of a desperate struggle with some straight-staring, rugged faced, hulking man, some man who seemed to be—to be John Smith! In the dream he had lost the bonds! For a long time he sat listening, listening, then started to rise from the bed. It was an effort. Illness had sapped his strength, he was weak as a child, but the will of him came to his rescue, that merciless, all compelling will against which no man or thing had ever stood.

Made giddy by the effort, with the world swimming about him hazily, he rested for a minute beside the bed, steadying himself by the support it gave; then, his eyes aglitter, his heart pounding, he went staggering, reeling, across the room. From a shelf high up in the rickety wardrobe he took down a little leather bag and opened it with fumbling fingers. Inside, folded separately, and placed one upon another, were many papers, bound into a package by a rubber band; he thrust his fingers into the bag. The papers crackled at his touch and he laughed senselessly. They were safe!

With trembling hands he slid one of the sheets out and opened it. It was a United States bond, printed in the golden yellow that one instinctively associates with things of great value. On its face it bore the figures $10,000. There were one hundred and fifty of those bonds in the bag one million five hundred thousand dollars! Here was not his fortune, but the means to a fortune that was to become millions and millions under his deft manipulations! Again he laughed, a mirth that was cracked, hollow.

After awhile he folded the bond, slipped it back under the rubber band, locked the little bag again, and stood swaying in the center of the room as if seeking a place to hide it. For weeks, during all the weary illness when he had lain unconscious, helpless, the little bag had remained safe and undisturbed. But now he had dreamed, and fear had been born in that dream. The bag must be hidden in some better, safer place safe from Smith, safe from chance discovery by his daughter!

An idea came! He could place the bag beside him, under the covers! There it would always be at hand, and with a revolver under his pillow—

IT was an hour later, perhaps, that the door opened with the slight squeak that had aroused him, and his daughter entered softly. The mist of tears was gone now, the lingering, doubtful fear had passed from the blue eyes, and the scarlet lips were smiling bravely.

"Edna," he said, and for a moment there was a return to the terse, masterful tone she had always known, "does it happen you have seen any account in the Paris edition of The Herald of trouble in one of the banks back home? An embezzlement, perhaps?"

"No. Daddy. Why?"

So, whether or not there had been an order sent to the Paris police for his arrest, nothing had come out back home! There was yet a chance, in spite of Smith! A chance? No, an absolute certainty! Clarke closed his eyes and lay back smiling.

DUSK had drawn a veil over Paris when Clarke awoke, and the only thing he was conscious of for a time, in the darkness of the shabby little room, was a vague white splotch, elusively outlined against the shadows. With an effort he focused it with his eyes, and after a long, long time he came to know it was the face of his daughter.

"Edna!" he said feebly.

"You are awake, father?" and a white hand, chilling as ice, rested for a moment on his brow. "Do you feel better?"

"I'm all right, girly," he assured her. "I was a little upset, that's all."

There was silence. He moved slightly, and something under the covers bumped against his side. One hand, exploring, came in contact with the little leather bag. The bonds! He smiled. They were safe yet! Smith hadn't been able to get them!

"I'm quite well." he continued, and there was a steadier note in the quavering voice. "In another week I'll be good as new. It takes more than a little typhoid to knock out your daddy, girly."

Edna didn't stir. After one quick glance she didn't even look at him. Instead she sat motionless, with pallid face, staring out the mottled window for a minute or more. The clear blue eyes had become somber and tense in the rigidity of their gaze.

"A gentleman called to see you while you were asleep," she said irrelevantly at last. "I told him, of course, that he couldn't see you; that you were ill."

"Who was he?" Clarke asked quickly.

"He said he was the Marquis d'Aubigny," the girl told him with deadly listlessness in her tone, "and he inquired for Mr. Charles Roebling."

"But I should have seen him—I must see him!" Clarke blazed with a note of excitement in his voice. "You shouldn't have sent him away! You should have—"

"He will return this evening; he said he would," the girl interrupted. Then, after a pause, "Father, why Charles Roebling instead of Clarke?"

"For reasons you wouldn't understand—business reasons." he explained tersely. "Did he set an hour?"

"Eight o'clock," she replied. "And why this dreadful little place instead of one of the hotels? We have always stopped at a hotel before, and—"

"Girly, you are asking about things now that I couldn't explain—to you. Some day you'll know; until then you wouldn't understand."

"And why that strange scene at the Café de la Paix?" Edna rushed on with sudden, dogged violence. "Why should Mr. Smith, or whatever his name is, be arrested under the name of Clarke—under your name? He seemed to know you, and you knew him. Why didn't one of you explain that there had been a mistake? And why should W. Mandeville Clarke—you—be arrested at all?"

She stopped with an odd, cold feeling of numbness and, leaning forward with her elbows on her knees, stared moodily at the floor. The scarlet had gone from her lips; her teeth were clenched desperately.

"Edna, don't disturb yourself with things you don't understand." Clarke reproved tartly. "Don't ask silly questions."

"I must know what it all means. Daddy—I must know!" The tenacity of purpose that characterized the father was born anew in the daughter. "I suppose Mr. Smith is locked up somewhere now under your name. How long is he to stay there? What has he done? What have you done?"

This was a new mood in his daughter. Clarke stared at her in sheer amazement, mingled with uneasiness. She had missed nothing of the meeting at the café! When he spoke again it was in the old voice of command she knew, the merciless, abrupt, triumphant business tone.

"If Smith remains locked up for a week, it means a fortune for me—a fortune of millions," he said. "If by any chance he is released and finds me the second time, it means—it means ruin, absolute ruin!"

"But why?" the girl insisted.

He didn't answer the question, and for some reason she didn't press it. Instead:

"You are not a rich man, are you, Daddy?" she asked curiously. "I mean rich in the sense of the great rich men of New York?"

"I'm a pauper, compared to the Wall Street crowd." Clarke replied steadily. "I am worth perhaps three hundred thousand dollars, perhaps less. However, if Smith stays in jail for a week, just a week. I'll be worth millions! Millions, girly! Do you understand?"

There was some inarticulate noise in the girl's throat, a sort of gasp, and he rose. Her slim hands closed tightly behind her back; she stood rigid.

"I shall not ask you. Daddy, why it is to your advantage for Mr. Smith to remain in jail: nor shall I ask you why he should have submitted to arrest under your name. But there is one thing I will ask, and I have a right to an answer! Why should anyone by your name be arrested? What have you done?"

Clarke picked nervously at the sheets with one hand, while the other gripped the little leather bag. "There's nothing I can say to that question now," he remarked slowly.

"I was afraid you wouldn't answer it. Will you answer this: Has there been any act of dishonesty?"

The words came hollowly, with an effort.

Clarke stared at her for a long time. Finally, "It is useless to continue such a conversation. I will see the Marquis d'Aubigny when he calls."

"Is it possible for a man in your position, a banker, to raise a large sum of money, a very large sum of money, or to have it intrusted to him for—well, say, for investment?"

"Why, girly, that is my business."

His fingers dosed more tightly on the little leather bag as his eves searched her face for the meaning of that singular question. And as he looked she seemed to be overcome suddenly by a violent revulsion of feeling and he found her on her knees beside the bed, her wet face buried in the sheets, sobbing.

"Forgive me. Daddy!" she pleaded. "Forgive me! It's all so strange, so unreal! I can't understand. I don't suppose I ever shall. I think I am not—not quite myself."

CLARKE rested his hand on her radiant hair until the storm of sobs had passed and fiercely fought back some powerful emotion that halted his words. "Do you know what you need more than anything else in the world?" he queried gently at last, and this was the father speaking. She looked up expectantly.

"You need a good cry. Run along now, and don't disturb yourself about horrid things you don't understand."

THAT night Marquis d'Aubigny, a little man of indeterminate age, immaculate, foppish even in dress, with that singularly loathsome expression of the eyes that one grows accustomed to seeing in the cafés of the Champs Élyseés, called and remained with Clarke for an hour. Edna, in person, admitted him to the poor little apartment, and under his stare flushed crimson with intangible anger, a helpless rebellion against the thing she saw there. With hot cheeks she turned away into the little cubbyhole of a room adjoining that in which her father lay and flung herself across the bed.

It was no fault of hers that she heard the conversation in that room, separated from that of her father by only a flimsy door which would not close perfectly; but when the Marquis had gone she stood for a time staring after him, then entered the room where her father lay. He was sitting straight up in bed in the act of opening the little leather bag. He tried to conceal it.

"What do you want?" he demanded harshly.

She stood silent an instant, swaying a little. "Nothing, Daddy," she said falteringly. "I don't want anything. I don't think I am quite well."

As he glared she stretched out her hands to him imploringly, her lips moved silently, and she fell prone.

MEANWHILE, Mr. John Smith was having troubles of his own, and rather enjoying them. He was sitting in a small office of the prefecture of police—police headquarters in Passaic—on the Île de la Cité, facing M. Baudet, a grim-visaged man of middle age who perfumed his whiskers and smoked vile cigarettes. Mr. Smith wondered if he perfumed his whiskers to kill the odor of the cigarettes, or if he smoked the cigarettes to kill the odor of his whiskers. M. Rémi was there, along with two or three other French sleuths, who glowered at Mr. Smith individually and collectively and babbled incomprehensible asides. Mr. Smith stood it for a long time: then, to M. Baudet, who seemed to be the chief:

"Well, Cap, you got me," he remarked pleasantly. "Now would you mind telling me what it's all about?"

Evidently this was what they had been waiting for, the prisoner to break the silence. M. Baudet stabbed him with a glance of his piercing eyes and remained silent. It was a highly effective method of his own, this silence, to reduce a man to fear and awe in the beginning. It sapped his courage and left him weak and flabby.

"If you're going to ask any questions, begin," Mr. Smith requested.

"I shall ask the questions, Monsieur, at the proper time." M. Baudet's tone was cold, incisive, steely.

"And all I have to do is to answer 'em?"

"That is all, Monsieur."

"Well, son, we'd better understand each other in the beginning," Mr. Smith remarked easily. "If you don't answer some of my questions right now. I don't answer any of yours. In other words, it you hold me here without telling me why, I'll get a man down here from the American Embassy and let out a scream they'll hear all the way to Washington. In the first place, I want to know why I was pinched."

There was a note of calm assurance in Mr. Smith's voice, utter composure in the powerful hand which lay idly on the arm of his chair. His straight-staring eyes were fixed squarely upon those of M. Baudet.

"Understand me, I'm not going to start any roughhouse or anything; but you've got to tell me why I'm here," he concluded.

"You shall answer my questions, Monsieur!" A slender, manicured hand, delicate as a woman's, tugged complacently at the perfumed beard; there was a merciless glitter in the eyes above it. "You are W. Mandeville Clarke!"

"Well, suppose I am?" queried Mr. Smith. "What has he done? Is there an order for his arrest from the United States?"

"Ah! You do not deny it! So you are Mandeville Clarke, alias John Smith, alias Watts Ittooyu!"

"I'm not denying anything." Mr. Smith returned placidly. "If I'm Clarke, what have I done? Have I murdered someone, or wrecked a train, or burned a barn, or robbed a safe?"

"You admit that you are Clarke?"

"I'm not denying it, am I? I want to know why I'm here. What's Clarke done?"

It was most disconcerting, really, quite unprisoner-like! M. Baudet had anticipated denial. This man denied nothing—merely wanted to know. That precipitated an embarrassing situation. Why had Clarke been arrested? Why was he being held?

"Your arrest was necessary, Monsieur."

And he hoped Mr. Smith would read, some deep, underlying threat in the words.

"Why?" Mr. Smith bellowed at him suddenly, belligerently. "Who ordered it? Have I committed a crime in Paris? If not, then the order for an arrest came from the United States. Who ordered it?"

M. Baudet blinked a little, and a long silence tell. These burly Americans! What monstrous voices they had, to be sure! And how evil they could look about the eyes! Alter a little M. Baudet glanced at M. Rémi blankly.

"Tell it to me now: I want to know," Mr. Smith insisted in a voice as if he was rooting for the home team. "You can't hold me here forever without telling me why, and if you don't tell me you've got to tell the American Ambassador!"

There was a little nervous twitch in M. Baudet's delicate hand as lie tugged at the perfumed whiskers again. Here was a situation unprecedented, an American, a pig of an American, without hope or honor in his soul, bawling at him. M. Baudet, as if he was a stevedore! When he spoke his own voice was like velvet.

"We knew you to be M. Clarke almost from the first." He said, and as he went on the velvety purr merged into frigid dramatics. "For instance, in introducing yourself at the Maison de Treville, you wrote your name, W. Mandeville Clarke, on a slip of paper: then, realizing your error, destroyed it. Here are those hits of paper, Monsieur."

He produced them. Mr. Smith stared.

"When one of my men met you on the Pont du Carrousel the following morning and asked your name, you hesitated before you answered. The assumed name of John Smith did not spring into your mind as readily as would have your own. It is an infallible test! Again, when another of my men accosted you in the Place de l'Opéra and asked the same questions, you gave a different name. In other words, Monsieur, when taken unawares you forgot the name you had assumed, and, realising only the necessity of giving some name other than your own, you gave the name Watts Ittooyu, and your address as the corner of the United States and two o'clock. I have the direct information, Monsieur, that there is no such address; therefore you are Clarke!"

THERE it was, all of it, as clear as mud! Mr. Smith didn't smile, because the one question to which he had been seeking an answer was not answered. He returned to it unwaveringly.

"Was there an order from the United States to arrest Clarke?"

"Well, Monsieur, the fact is—" and M. Baudet hesitated a little, "the fact is our instructions from the United States were not so complete as we should have wished: so—"

"Was there an order from the United States to arrest Clarke?"

"Well, there was no direct order; but—"

Mr. Smith drew a long breath, a very long breath. "But you did have a request from some one, possibly a private detective agency, to keep a lookout for Clarke?" he continued. "And a description of Clarke?"

"That is true. Monsieur: but you must understand—"

"Now." Mr. Smith interrupted abruptly, "you yourself say you had no order to arrest Clarke. Your men had evidently been watching me pretty closely since I have been in Paris. Have I committed a crime then?"

"You went on and on endlessly in the farce of searching for yourself. Monsieur. We knew you were Clarke, and it was necessary to bring the matter to a conclusion. So you were arrested. I shall notify the agency in New York immediately, and—"

"No charge against me in the United States, not even a charge against me in Paris, and still you pinched me!"

M. Rémi leaned forward suddenly and mysteriously whispered into the pearl-like ear of his chief, whereupon a glad smile split the perfumed whiskers, and the piercing eyes grew cunning.

"If you are thinking you are to be freed immediately. Monsieur, you are mistaken." M. Baudet remarked suavely. "There is a charge against you in Paris, and even your American Ambassador cannot aid you until that charge is disposed of. That is that you have violated our laws by living here under an assumed name and in disguise!"

THEN Mr. Smith smiled. He leaned back in his chair, crossed his sturdy American legs, and continued to smile. Away back of that smile was the consciousness that Clarke's perfidy had not been discovered in the bank; that it had not been reported to the police; that the supposed package of United States bonds in the vault was still unbroken; and that so long as those things were true, he, Mr. John Smith, was not only in no danger himself, but was at liberty to pursue the task he had set himself, of finding and returning those bonds. If their loss was discovered, it meant the collapse of the bank, inevitably.

"Well, Cap," and Mr. Smith was purring like a tickled kitten. "I'll just bet you ten dollars to the hole in a pretzel that I am not in Paris under an assumed name, nor am I disguised! Sad as it may seem, this is my own face."

"Not disguised!" exclaimed M. Baudet. "Not under an assumed name! But you are M. Clarke!"

"Who told you so?"

"You did. Monsieur."

"Wrong, Cap. I merely didn't say I wasn't Clarke. You must have a pretty accurate description of Clarke. He's a man about my size?"

"Just your size. Monsieur."

"With gray hair?"

"You have dyed it. Monsieur. It has that dingy look of dyed hair."

"Thanks! If you know of anything that will take the dye off. get busy. Your description probably said too that Mr. Clarke has a full, square-cut beard?"

"A razor, Monsieur." M. Baudet smiled.

"But your description did say a gray beard?"

"Yes, gray, almost white."

"Well, take it from me. I'm not Clarke. All you've got to do to convince yourself is to sit right still then for the next ten hours and watch my whiskers grow. They'll come out black."

There was silence, dead silence, a silence fraught with tragedy. After a long time M. Baudet turned upon M. Rémi with a sinister glare in his eye.

"If that is true, M. Rémi," he said reassuredly, "it is evident that you have made the mistake."

M. Rémi bowed his head in shame and sorrow; then another idea came. He spoke aside to his chief, who in turn addressed Mr. Smith.

"Your name is John Smith, then?"

"John Smith, of Passaic, New Jersey."

"You have been looking for M. Clarke, too. Who are you? Why have you been searching?"

"Because I wanted to find him," replied Mr. Smith. "Now you fly cops in Paris are pretty nifty, Cap. Can't you imagine why I came all the way from the United States to find Clarke, the same man you are after? Doesn't it suggest anything to you?"

Gradually a light of understanding grew in M. Baudet's eyes, and for a second time the perfumed whiskers parted in a smile. "Perhaps," it came in a thrilling whisper, "perhaps you too are a detective!"

"Ah!" It was most noncommittal. Mr. Smith rose and stretched his long legs. "There is the native shrewdness of France, Monsieur!"

They shook hands.

Late that night Mr. Smith returned to his room in the Maison de Treville with an odd smile of satisfaction on his face.

ON the following afternoon five men met with W. Mandeville Clarke in the shabby little apartment in the Rue St. Honoré, and important business papers, involving millions, were signed. By the terms of the deal Clarke was temporarily to hypothecate United States funds valued at one and a half million dollars. Smiling triumphantly, he opened the little leather bag.

It was empty!

FOR the major part of the day and all the evening following the mysterious disappearance of one million five hundred thousand dollars' worth of United States bonds from the shabby little room in the Rue St. Honoré Mr. John Smith hovered about the lobby of the Maison de Treville like an uneasy bill collector. He had been expecting something, he didn't know what. A letter? Perhaps. A telegram? Maybe. A call in person? Not at all unlikely. Whatever form it might take, it was something coming from the void, an illuminating, star-like light to lead him through the maze. He was perfectly convinced of it, albeit the conviction was based upon nothing more substantial than a well developed Passaic hunch.

Shortly after nine o'clock he strolled around the corner into the Rue de Seine to invest fifty centimes of hard earned American cash in a bad cigar, all cigars being bad in Paris. As he re-entered the lobby, the night clerk, that astute young man with the smile and the delicately waxed mustache, ingratiatingly picked up a letter and held it aloft.

"Billet pneumatique, Monsieur," he announced.

"Who?" asked Mr. Smith.

"Billet pneumatique."

"You can search me, son; I don't know him."

The clerk shrugged his shoulders hopelessly, walked round the desk, and placed the letter in Mr. Smith's hand. Mr. Smith glanced at the superscription.

"Oh. For me. I thought you said it was for Billy somebody."

The handwriting was a woman's. Now that it had had come, Mr. Smith knew that it was precisely what he had been expecting.

Of course it was from a woman! He had known all along that it would be! He dropped into a settle in a corner and opened the letter.

It was like this:

To-night at 10:30 taxicab will pick you up at the north side of obelisk in Place de la Concorde. Matter of greatest importance to you.

There was no signature. Mr. Smith had expected none. He glanced at his watch—it was nine-twenty-seven—after which he sat for a long time with utter blankness in his straight-staring eyes. His meditations were not unpleasant, if one might judge from a certain softness about his mouth, almost a smile. Perhaps he was dreaming of Passaic.

Whatever it was, he was brought back to cold, sordid earth by the approach of a stranger who had entered, a small man of indeterminate age, immaculate, even foppish, in dress, with a pair of evil eyes in the head of him.

"Pardon me," said the stranger in English, "this is M. John Smith?"

"Of Passaic, New Jersey. Yes, sir."

"Permit me to introduce myself. Monsieur. I am the Marquis d'Aubigny."

He bowed low and presented his card. Mr. Smith read the name and bowed lower. There was a certain uneasy air of surprise in his manner. To his broad, democratic mind, Kings and Queens and Dukes and Marquises were persons who walked the face of the earth with exalted crowns on their heads. This chap had on a silk hat.

"It is the great pleasure. Monsieur, to meet you."

"Same to you, sir." Mr. Smith was holding up one foot awkwardly with a crushing sense of having failed in the formalities. "Have a seat, Mr... er—er—er—Sit down."

M. le Marquis disposed himself gracefully, on the settle. He reminded Mr. Smith, languidly, of some one, strangely. Suddenly he knew who it was. It was Richard Mansfield as Baron Chevrial. That was it, that disgusting, loathsome, marvelous creation of an actor's art! Verily, here was Bill Roue in person; so, to Mr. Smith's unembroidered Passaic mind. Mr. Smith sat down gingerly.

"I have come to you on a little matter of business. Monsieur," the Marquis said slowly, impressively. "I come from M. Clarke."

"Oh!" Mr. Smith stared at him for an instant, then rose and paced the length of the lobby twice with his fingers gripped behind him. When he paused in front of the Marquis, his eyes had grown steely, his powerful jaws were set. "What business?" he demanded abruptly.

Marquis d'Aubigny permitted his wicked little eyes to wander about the lobby. There was no one in sight except the night clerk.

"He doesn't speak English," said Mr. Smith shortly. "Go on!"