RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Short Stories, Jun 1917, with "By a Hair's Breadth"

"Paul Beck, The Rule of Thumb Detective,"

with "By a Hair's Breadth"

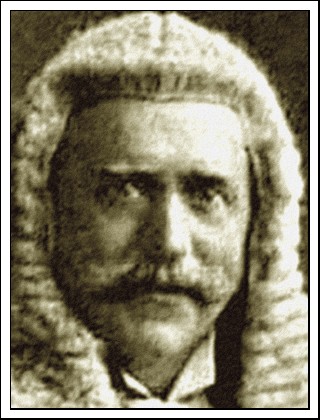

M. McDonnell Bodkin

Irish barrister and author of detective and mystery stories Bodkin was appointed a judge in County Clare and also served as a Nationalist member of Parliament. His native country and years in the courtroom are recalled in the autobiographical Recollections of an Irish Judge (1914).

Bodkin's witty stories, collected in Dora Myrl, the Lady Detective (1900) and Paul Beck, the Rule of Thumb Detective (1898), have been unjustly neglected.

Beck, his first detective (when he first appeared in print in Pearson's Magazine in 1897, he was named "Alfred Juggins"), claims to be not very bright, saying, "I just go by the rule of thumb, and muddle and puzzle out my cases as best I can."

...In The Capture of Paul Beck (1909) he and Dora begin on opposite sides in a case, but in the end they are married. They have a son who solves a crime at his university in Young Beck, a Chip Off the Old Block (1911).

Other Bodkin books are The Quests of Paul Beck (1908), Pigeon Blood Rubies (1915), and Guilty or Not Guilty? (1929).

— Encyclopedia of Mystery and Detection, Steinbrunner & Penzler, 1976.

AS Mr. Beck went up the broad stone steps of the front entrance of Holmhurst, the stately seat of the Duke of Southern, he passed two men going down rather hastily. One of the two was tall and lithe, with a long, clever face that somehow seemed familiar to Mr. Beck. His companion, who walked a little lame, was shorter, stouter, and duller looking. The tall man was talking vehemently, the short man was listening submissively. As they passed, Mr. Beck heard a fragment of a sentence—

"The conclusion I have come to is the only possible logical and scientific deduction if the Duke only——"

The electric bell tinkled. The gorgeous footman showed Mr. Beck straight through the great hall, crowded with trophies of many centuries, to the room, a small library or large study, whichever you please to call it, which was the Duke's own private sanctum.

His Grace was pacing the floor restlessly, like a particularly active sentinel, backwards and forwards on the same line of the carpet. A handsome, well-set-up man was the Duke, about forty years of age, with broad shoulders, and a kindly face pleasant to look at. But now the pleasant face was clouded by anxiety and anger. So self-absorbed was he that he did not hear the footman call the name; he did not see Mr. Beck softly enter the room, but kept on his restless pacing, muttering to himself as he walked.

Mr. Beck silently dropped into a roomy leather-covered chair, and waited, watching the restless figure narrowly as it passed and repassed within a yard of him.

At length the Duke's eyes lit on the detective suddenly, as he sat there patient and vigilant. He stopped short in the middle of his restless course, and stared at the strange, motionless figure with angry amazement.

At length the Duke's eyes lit on the detective.

"I beg your pardon, sir," he said, "I have not the honour of—may I ask who?"

"Oh! my name is Beck. You wired to town for me."

"Mr. Beck, the famous detective?" said the Duke, with a polite attempt to hide his surprise at the general appearance of Mr. Beck.

Mr. Beck put aside the compliment with a wave of his big hand. "I will do my best," he said modestly, "and the boys say I'm lucky. What can I do for you, Duke?"

"My dear sir, you can help me out of the biggest trouble of my life. Up to half an hour ago I hardly cared at all, except, of course, for her sake. But now? Did you meet two men as you came up the avenue?"

"I met two men on the steps."

"The same. You recognised the taller of the two?"

"I thought I knew his face."

"Of course you knew the face of the famous detective, Mr. Murdoch Rose. He doesn't object to be called 'famous.' I had hoped that you and he might work this case together. But he has gone off in a temper, and left me in a worse one."

"It could not have worked out any way, Duke," said Mr. Beck quietly. "He doesn't like me. He says—so I'm told—that I am the last of the slow coaches, that my brains are waterproofed against the teaching of science. But what sent him off now at such a tangent?"

The Duke blushed, actually blushed, and ground out a monosyllabic invective between his teeth like a commonplace plebeian.

"I'd rather not say, if you will allow me. It hurts me even to think of it."

Mr. Beck looked persistently inquisitive.

"Well," said the Duke, answering the look, "I am bound to tell you everything, I suppose, like a father confessor amongst the Catholics. But this is grotesque; you will hardly credit it. When Mr. Rose heard all the facts he asked to see me alone, and saw me. He was convinced—or he affected to be convinced for some purpose—that it was my wife herself stole the opal. I kept my temper all through wonderfully—wonderfully. 'But, Mr. Rose,' I said, 'this is idiotic nonsense.'

"'Nonsense,' he said, 'is often another name for quintessence of reason.'

"'But there is not a scrap of motive,' I said.

"'When we have facts we don't look for motive.'

"'The thing is ridiculous—impossible.'

"'Impossibility is no answer to truth.'

"Of course that ended it. I was as civil to him as I could be, but I'm afraid that was not overmuch, and he marched off with his head in the air. I cannot tell but he will air his opinions elsewhere. You will readily understand, then, how eager I am to get to the bottom of this business. So that——"

"May I come in?"

It was a woman's voice—a very pleasant woman's voice. Without waiting for an answer a girl, not more than twenty years of age, glided into the room, light and graceful as a young deer.

She was dressed in a dark blue silk that rippled and flashed with changing light, like the clear sea in sunshine and shadow. There were diamonds on her white throat and in her dark hair. Her Grace was American.

"Not a word before her," the Duke whispered hastily as she came towards them. Then aloud, "Mr. Beck, this is my wife."

She gave the detective her little hand frankly, flashing a welcoming smile from her dark eyes.

"Oh! I'm so glad you've come. I have heard of you from my friend, Lily Harcourt—the diamonds case, you know—and I got the Duke to telegraph you at once. I know you will find out who stole my opal. Such a beauty it was, Mr. Beck, you can't think. It was as big as a walnut; yes, as a small walnut, Reggie. There was not another like it in the whole world. The Queen herself could not have one like it if she wanted ever so much. Then it was real lovely to look at, all the glow and colour of the sunset hidden in it. It was my own fault it was lost, of course. I would wear it down here. But I know you will find it for me, Mr. Beck, as soon as ever you can. You found Lily's diamonds in one day after they were stolen—don't you remember? But I must warn you not to begin by suspecting the wrong person. Lucy, my maid, has nothing to say to stealing the opal, nor her sweetheart, either, though they have put him in gaol for it. He couldn't, you see, without her knowing it, and she wouldn't, I know. We were children together—Lucy and I—when I was at home, and she came here with me as my own maid—though she is more companion than maid—when I was married, and she's the very last person in the world who would think of—— But I forget, you cannot know in the least what I am talking about, indeed I hardly know myself, I'm so excited. I think I'd better go for Herbert, dear"—this to the Duke—"I left him in the billiard-room. He's so quick and clear, and will tell Mr. Beck the whole story straight out from the beginning."

With the rustle of silk and a flash of jewels, her volatile ladyship vanished.

With the rustle of silk and a flash of jewels, her volatile ladyship vanished.

Mr. Beck and the Duke stood for a few minutes together at the great bow windows looking silently out over the fair, wide prospect. The vivid green lawn sloped down to the edge of a bright lake where swans swam. Beyond, the great demesne stretched to the sky-line, luring the eye with long vistas dappled with light and shade, where deer flitted ghost-like through the aisles and arches of the summer trees.

The lord of all this sylvan loveliness turned suddenly to the detective with sore trouble in his eyes.

"No," said Mr. Beck, in answer to the unspoken appeal, "Ellen Terry or Sarah Bernhardt could not act like that. Your Grace was right—the notion is grotesque."

"Mr. Rose declared it wasn't my gamekeeper," said the Duke, "'because you can never trust a case,' he said, 'that looks too plain.' My wife says the same, because he's the sweetheart of the girl Lucy she's so fond of. But Markham is in prison for it, all the same, with a bullet-hole drilled through his leg by Herbert's revolver. Herbert is my brother, you know. But here they are, and Herbert will give you the facts at firsthand as far as we know them."

The Duchess had brought back with her a very striking-looking man; like the Duke, but taller and handsomer. He carried his height with soldierly ease, for he had been in the Life Guards. The face was frank and resolute; the broad forehead was framed with close, crisp curls of old gold just flicked with silver. He looked like one to win woman's love tenderly or dare man's hate resolutely—one whom danger could not shake nor cunning betray.

Mr. Beck was, in his own way, a believer in physiognomy, "taking stock of a man" he called it. From the first he seemed attracted by the Honourable Herbert Selwyn.

There was the twitching of a suppressed smile about Herbert's handsome mouth when the Duchess presented him to the stolid Mr. Beck, but it in no way marred the perfect courtesy of his manner to the detective.

"Now tell him the whole story," said her Grace impetuously.

Then with a laconic military precision he set the facts before the detective.

"You have heard of the great 'Southern Opal,' Mr. Beck?"

Mr. Beck nodded.

"It has been an heirloom in our family since the days of Queen Elizabeth, and is without match or rival in the world, they say. At the Queen's Jubilee the Rajah of Mangapore offered my brother a quarter of a million for it. Those fellows don't understand things—think that money will buy anything. But that will give you a fair idea of the value anyway. Before my brother's marriage the opal used to be kept locked up in the strong room of the bank. But Ethel—her Grace, I mean—naturally enough took a fancy to wear it. She got a safe let into the wall of her dressing-room under the hangings. There was but one key, which she kept about her night and day."

"This is the key," interposed her Grace, and she put into Mr. Beck's hand a small, slim, steel key with many wards, which he examined curiously.

"It happens," the Hon. Herbert went on, "that my dressing-room adjoins her Grace's. I have exceptionally quick ears. As I was dressing for dinner last evening, I thought I heard the whispering of voices in her Grace's room. I had just left her in the drawing-room only a moment before. My suspicions were naturally aroused. I took a revolver from a drawer, slipped off my boots, and crept quietly to her door. There was no mistake about the voices. One was a man's. I opened the door as softly as I could; the candles were lit. The man was standing with his back to me, close to the corner where, as I have learned, the safe is set. The girl was facing the door, and screamed out when she saw me. The man bolted for the open window, and leapt out twenty feet at least to the ground. I had a snap shot at him as he wheeled round a rhododendron bush. I fired low, and it seems I put a bullet through the calf of his leg. But while I had rushed to the window the woman had fled through the door. I followed to alarm the house, and I met Ethel on the stairs. She had been frightened by the pistol-shot.

"'You're not hurt?' she gasped out.

"'I'm afraid nobody is hurt,' I answered. 'The fellow has got clean away.' I didn't know then he was shot.

"'A burglar!' she cried. 'Oh! my opal!' I declare I hadn't even thought of the opal until that moment.

"We went straight back to the room together. The safe was open and the key in the lock. All the other jewels, some of great value, were untouched, but the opal was gone.

"There's the whole story for you so far as it is known."

"And this man?"

"Turns out to be the Duke's head gamekeeper, Markham—William Markham. He came and gave himself up. He was bleeding like a pig. But he protested his innocence. He had not got the opal, of course. His wound was dressed and then he was packed off to prison."

"And the girl?"

"Oh! the girl was Lucy—my own maid, Lucy," broke in her Grace. "She came crying to me and told me all about it. She is the best of good girls. You remember, Reggie, how she nursed baby Archie last year, when they thought he had diphtheria, and every one else was nervous, and I was not allowed to go near him? He loves her next to me in the world, I do believe. She was in my room, Mr. Beck, when I left yesterday after she had dressed me, and the lights were lit. It seems that Markham is her sweetheart, and he saw her at the window, and he climbed in. But she swears that neither of them even so much as thought of the opal, and I really do believe that——"

"Mr. Beck wants only the facts, Ethel," interposed her husband, smiling at her vehemence. "He can draw his own conclusions."

"Can I see the dressing-room?" asked Mr. Beck.

"Certainly."

"And the girl Lucy?"

"I will have her sent to you at once."

Mr. Beck had barely time to cast his eyes round the room, whose walls were hung with pale blue silk, when a timid knock came to the door.

"Come in," said Mr. Beck, and a pretty, pale-faced young girl came in. Her eyes were red with crying, and she was trembling all over so that she could scarcely stand. But all the same, she looked innocent and honest.

"Sit down, my dear," said Mr. Beck very kindly, "and tell me all about it."

"It was all my fault," she broke out incoherently. "Now Willie is shot, and they're going to try him at the 'Sizes, and maybe hang him for it, and he is as innocent of the like as a child unborn."

"It was all your fault! What was all your fault, my dear?" asked Mr. Beck soothingly.

The brown eyes flashed an indignant look at him through their tears.

"It wasn't the opal," she cried. "We never touched the opal if that's what you mean. Oh! I beg your pardon, sir. But I cannot bear to think of it. Indeed, it was not after the opal Willie came, it was after—— I bade him begone at once, but he wouldn't till I gave him—— he wasn't half a minute here altogether, and neither of us were thinking of the opal, when Mr. Herbert came bursting in with his pistol and shot him. You're a detective, sir, I hear"—this very timidly—"you'll do your best to save him?"

"To save him, my dear, if he is innocent, and to gaol if he isn't."

"I don't ask no better than that," said the girl gratefully. "I know he had neither hand, act, or part in this bad business."

"Now I want you to answer me one or two questions truthfully."

"Now I want you to answer me one or two questions truthfully."

"That I will, sir."

"You know where your mistress generally carried the key of the safe?"

"She wore it on a little gold chain round her neck and hidden in the bosom of her dress."

"Can you remember if she wore it yesterday evening?"

"Well. She dressed early for dinner. I saw the chain round her neck, and the key on the chain before she went down to the drawing-room."

"You knew all about the safe?"

"Of course I did."

"And knew that the opal was there?"

She paused for a moment and looked him straight in the face, with honest brown eyes.

"If you mean that I could have stolen the key and stolen the opal, that I could any hour of the day or night almost, without help from Willie either. But I didn't, and Willie didn't, though he's down for it, and if you find out the truth of it, that's all we ask. We'll both pray for you to our lives' end."

"I'll do my best, my dear," said Mr. Beck very pleasantly. "Truth is at the bottom of the well they say, and the water's sometimes a bit muddy, but I'll do my best to fish it up. Now, will you kindly tell your mistress—her Grace, I mean—that I would be glad to see her here for a moment or two, if she'd be so kind."

"I'll send to her, sir. I couldn't bear to face her myself with this disgrace on me."

"Well, Mr. Beck, what do you say now?" cried her Grace excitedly, as if the mystery was a conundrum to be guessed or given up instanter.

"Well, Mr. Beck, what do you say now?" cried her Grace.

"I say nothing," said Mr. Beck placidly.

"But you sent for me; you have something to tell me?"

"Something to ask, my lady, not to tell. Have you got the key of the safe you showed me just now?"

"Here it is."

"And the chain it was on?" he continued.

"Here it is."

Mr. Beck examined the chain minutely. It had been snipped across by sharp nippers.

"You don't know when this was done?"

"I cannot say at all. I did not miss the key until I found it in the lock of the open safe."

"Did you bring it down with you to the drawing-room yesterday evening?"

"I think I did, but I cannot be quite sure. I have no special recollection of it."

Then Mr. Beck, with the key in his hand, went straight to the corner of the room where the safe was.

"How did you know it was just there, Mr. Beck?"

"The wrinkles in the hangings. Besides, the eyes of your maid, when I spoke of the safe, told me where it was."

The heavy bars of the lock yielded like a hair trigger to the touch of the slim key, and the massive door opened on smooth hinges.

The safe was a masterpiece of construction; it went in deep and dark into the wall. Mr. Beck could see that it was divided into an upper and lower compartment by a horizontal shelf of fine, closely-woven steel wire. Both compartments were crowded with jewel-cases.

"There was nothing touched except the opal?" he asked.

"Absolutely nothing."

"Where was it kept—in the lower compartment?"

She nodded, wondering how he knew.

Mr. Beck took a small electric lamp from his pocket, opened the slide and touched the spring that lighted it. Then, thrusting his head into the lower compartment of the safe, he examined the sides and bottom minutely with a strong magnifying glass. As he drew out his head he felt something tickle the back of it. He turned up the light and found a little cluster of fine points projecting from the bottom of the wire-woven shelf.

He examined those with such care that her Grace noticed it.

"Oh! that's nothing," she said; "that little flaw in the shelf was there when the safe was first put up. The wires got broken a little. They used to tickle the back of my head too. At first I intended to have it fixed; the ends of the wires cut off or something. But I forgot, and after a while I didn't notice it. I suppose I learnt to keep my head out of the way."

Mr. Beck answered never a word. His head was back again in the safe, and he renewed his examination of bottom and sides with even more care than before.

"No one had any business to go to the safe but yourself?" he asked, after a long pause.

"No one," she answered, and he went on with his examination.

"Well, Mr. Beck?" her Grace demanded impatiently, when he finally drew out his head, and closed his lamp with a snap.

"Well, my lady, I have learned all the safe has to tell me. Its story is very interesting, but it is confidential for the present."

"If the safe has no more to say to you, nor you to the safe"—this with a little touch of petulance in her pleasant voice—"my husband will be glad if you will have lunch with him in the library. You will excuse me. My brother-in-law returns to London by the night mail, and I've got to look after him."

"May I ask, Mr. Beck, have you found any clue?" said the Duke a little anxiously, trifling with his plate while Mr. Beck made excellent play with his knife and fork.

Mr. Beck sipped his glass of ripe Madeira with keen appreciation as he replied—

"There are always too many clues, Duke, the trouble is to disentangle them."

"Would it be fair to ask at this stage what is your theory of the crime?"

"Never had such a thing in my life, your Grace. I go by facts. If you start with a theory you try to force the facts to fit it, and facts won't be forced. There is not any science in detective work. It's like playing blind man's buff—you grope about here and there, turn back when you knock your head against a stone wall, but keep on fumbling till you lay your hands on the man you want—or the woman."

"What would your friend, Mr. Rose, say to all that? He goes in for pure science, doesn't he?"

"I remember when I was a boy, your Grace, reading in a story-book—kind of fairy tale I think it was—of a country where they measured a man scientifically; took his altitude with a quadrant and calculated his length, breadth, and thickness by trigonometry. Well, the common tape measure is good enough for me."

"For a clever detective," said the Duke, "you have rather a poor opinion of your profession."

"Clever, your Grace? I'm not clever; perhaps I'm none the worse for that. A detective may easily be too clever by half. The performing dog in the show is very clever, and his tricks are pretty to look at, but he wouldn't do to catch a fox."

"Can you catch this fox, Mr. Beck?"

"I hope so. I think I am on the scent. I cannot say more at present."

"How long can you stay with us?"

"I must leave by the night mail for London. It is well to throw the thief off his—or her—guard; besides, I've got some business there that won't wait."

"By the night mail? Then you will be up with my brother."

"I knew that. Her Grace told me so. I hope I may be allowed to travel in the same carriage. If I may make so bold as to say so, I have taken a great fancy for your brother. He's clever, cool, and plucky, or I'm no judge. Just the man to help me through with this job."

"He'll be glad to help you if he can, for this wretched business has worried him as much as ourselves. He lives in a flat in London, close to St. James's, and his time is all his own since he dropped out of the army."

"I shan't trouble him more than I can help, but I should like to know he's there if he's wanted."

The Hon. Herbert Selwyn cordially renewed, on his own account, the promise of help made by his brother. "Treat me like an apprentice detective, Mr. Beck," he said pleasantly. "I'm willing to go anywhere and do anything to help you to lay your hands on the opal and the thief. Though for the thief I think myself you need not go beyond Markham in the county gaol."

The Hon. Herbert professed to be very delighted to have Mr. Beck's company to town. His sleeping compartment was abandoned for a first-class smoker. The guard was tipped handsomely to keep out intruders, and he and Mr. Beck smoked and chatted the whole way up to town. Mr. Beck had some curious stories in which his companion was much interested. But, of course, their talk ran chiefly on the opal robbery. They talked it round and over in all its bearings, and the detective frankly confessed he got some very useful hints from his companion. On the other hand Herbert was a little shaken in his certainty that Markham was the man by Mr. Beck's doubt on the point.

The Duke's brother shook the detective's hand cordially as they parted at the terminus.

The Duke's brother shook the detective's hand cordially.

"Here's my card," he said. "Remember I'm always ready and willing wherever you want my help."

"I won't forget," said Mr. Beck.

But it so happened that Mr. Beck had the first chance of helping.

Two nights later the Hon. Herbert dropped into the Empire Music Hall for the last hour of the performance. As he was passing out through the crowd he suddenly felt his right hand seized. He looked round, and saw a stout, middle-aged woman, dressed in black bombazine relieved by a big, gaudy bonnet on her big head, who at once began shouting: "Polis! Polis! Stop thief! Polis!" and making a furious demonstration with her umbrella.

He wrenched himself free in a moment, but the crowd closed in on him.

"What's your trouble, ma'am?" said a big fellow, who looked like a respectable mechanic.

"The villain has tuck my purse," she cried excitedly, "with nineteen shillings and fippence in it, not to speak of a lucky thruppenny I wouldn't part with for gold. I felt the pull at my pocket, and I grabbed his hand that instant minnit. P'lice! p'lice!"

"The villain has tuck my purse," she cried excitedly.

Two policemen lounged across the street with a dignity all their own, looming large in the gaslight. The crowd made way for them as the waves part before a ship's prow.

"What's all this row about?" said the stern voice of authority.

"I charge him, sergeant, I charge him. I caught him with his hand right in my pocket. It's a brown leather purse with a brass clasp to it, and I'd know it anywhere."

"What have you to say to that?" asked the sergeant of the accused.

"Don't be a fool," said the Hon. Herbert Selwyn incautiously.

The official dignity took fire.

"I'll let you see who's the fool at the station, my fine fellow. I know how to deal with chaps like you. You'd better keep a civil tongue in your head for your own sake. Do you charge this person, ma'am?"

"I charge him. I charge him. Hold him tight, sergeant, the villain of the world; if it was the last breath I had to draw I'd charge him."

Then the heavy hand of the Law fell upon the shoulder of the Hon. Herbert.

His fists clenched instinctively.

"Come, none of that!" said the sergeant, fingering the handle of his baton. "You may fancy yourself in for a row, but we're two to one and help near. Come quietly or come on the stretcher, just as you please, but come you must."

"Do you know who I am?"

"Nor don't care."

"My name is Herbert Selwyn, brother to the Duke of Southern."

There was a derisive howl from the crowd.

"Make it the Prince of Wales, guv'nor!" cried a voice.

"Here's my card."

The sergeant held out his hand, waiting incredulously. The Hon. Herbert fumbled in vain. His pocket had been picked, at any rate—his purse was left but his card-case was gone.

"We've had about enough of this gammon," broke out the sergeant roughly. "You can finish it up if you want to at the station. Come along!"

Herbert had got back his coolness by this time. "I suppose there is no help for this asinine performance," he said quietly, "the sooner it begins the sooner it will be over. I'm ready."

"That's more like it," said the sergeant; "I thought you would come to reason."

The crowd made a move to join in the procession to the police-station, but the sergeant hailed a four-wheeler.

At the station the old lady was voluble and vehement, while Herbert treated the whole performance with quiet contempt. The charge was duly entered on the sheet, and the accused was searched with the minutest care.

A half-sovereign that had slipped into the lining of his waistcoat was brought to light. But, in the language of the police reports, "nothing of an incriminating nature was discovered." The police began to look a little blank. A policeman, however, never confesses he's wrong if he can help it. The Hon. Herbert Selwyn seemed booked for a night in a police cell. But just as the search was completed and all his goods and chattels spread out on the thick deal table in the police-office, he heard a voice he knew speaking to the inspector in the outer room.

"Anything up to-night?" said the voice.

"Nothing of any consequence, Mr. Beck," was the deferential reply. "A swell mobsman caught at the Empire with his hand in an old lady's pocket. Plucky old lady; she collared him on the spot and held on. He's a cool card and no mistake; swears his name is—let me see" (he consulted the charge-sheet) "oh! 'The Hon. Herbert Ulick Selwyn, brother to the Duke of Southern.' Do you know any nobleman of that name, Mr. Beck?"

"I rather think you've put your foot in it up to the hip," observed Mr. Beck drily. Without another word he walked into the inner office.

"Hallo, Mr. Beck," cried the accused, "I'm particularly glad to see you," and he shook his hand cordially.

"You've done it," said Mr. Beck to the sergeant. "Do you know that this is the Duke of Southern's brother?"

"I didn't care if he was the Duke himself," said the sergeant, half sulky, half frightened, "when the old lady charged him I was bound to take him."

"You're a blockhead, sergeant," retorted Mr. Beck cheerfully. "What in God's name would tempt him to steal an old woman's halfpence? Where is your old woman, anyway?"

She had disappeared, unnoticed by the police, who were absorbed in the search.

"This looks bad for you, sergeant," said Mr. Beck.

"I only done my duty, sir," said the sergeant doggedly.

"You should have been more careful," broke in the inspector, taking sides with the Duke's brother and the famous detective.

"Oh! let the poor devil off," interposed Herbert goodnaturedly. "He thought he was doing his duty. Here's the half-sovereign, sergeant, for your trouble. Take it, man; you've the best right to it. It would never have been found only for you."

Midnight was pealing or clanging in a thousand tones from the clocks of London, when Mr. Beck and the Hon. Herbert Selwyn walked out of the police-station together into the cool night.

"I'm ever so much obliged to you," said Herbert frankly, "but for you I might have been locked up in that hole all night."

"You've nothing to thank me for," said Mr. Beck, "nothing whatever."

"Oh! I know better than that. Are you up to any little game to-night? Hunting any daring criminal to death?" He could hardly help smiling at the notion of the placid Mr. Beck hunting a criminal to death.

"No? Then come across to my place and have a B. and S. and a cigar. We'll walk if you don't mind. I want to get a little of the cool air into my blood after that hot hole you pulled me out of. No news of the opal, I suppose?"

"I think I've got a step closer to it to-day, or rather to-night."

"By Jove! I'm glad to hear that; mustn't ask any more, I suppose? For her sake I'm deuced anxious, you know."

"I promise you shall be among the first to know when I have got my hand on the thief."

"Thanks, awfully. Well, here we are; mind, there are four steps there." He turned the latchkey into one of the half-dozen doors of a great block of buildings as he spoke, and they passed into the hall. "The lift is done for the night; we keep decent hours, you see. But it is only the second floor. You won't mind the stairs?" Herbert said, leading the way up a broad, shallow, richly carpeted staircase.

He muttered a little petulant oath, with no real ill-temper in it, when he turned the handle of his own door, and found the room in utter darkness.

"I told my fellow to leave a glimmer of the gas turned on. I can never find the lighter or the matches."

Mr. Beck produced a box of matches from one pocket and a little electric lamp from the other.

"You're a miracle," laughed Herbert, as he lit half a dozen jets. The room was a large one, furnished with exquisite taste, old engravings—plain and coloured—were on the walls, and old massive mahogany furniture, polished and black, and upholstered in flowered damask, was on the thickly carpeted floor.

"There is nothing like electricity," said Herbert, as Mr. Beck turned off his little lamp, and slipped it back into his pocket. "There's a fellow coming to fit up my rooms with electric light to-morrow."

"From Voltage and Bright?" inquired Mr. Beck.

"The same—do you know them?"

"A little. They are said to be the best firm in London; all the most modern appliances. You see, in my trade we have to dabble a little in almost everything; the murderers and the burglars—the high-class ones at least—have begun to study electricity, and we cannot afford to be left behind."

"Will you have brandy? I've a rare brand of old Irish whisky, if you prefer it."

Mr. Beck took the old Irish whisky and a choice Havanna cigar, and sat back in a deep easy-chair, sipping and smoking, the very picture of genial simplicity. "The Duke is coming up to town," Herbert said when he had helped himself in turn. "He will be here the day after to-morrow, and the Duchess with him. She will be rejoiced to hear you have got on the track of the opal."

"Do they stay long in London?"

"Only one day. Business. They put up at the Victoria Hotel, but they have promised to come over to lunch with me. I hope to have the electric light fitted up in time. Her Grace has quite a craze for it. Wants the Duke to get it into Holmhurst. Voltage and Bright have promised to send a man over to show off. It may mean a big order for them. By the way, you might look in while they are here. I'm sure they would be both glad to have a word with you."

"If I can manage it I will, but I shall be very busy, so don't expect me."

"You'll be welcome if you come. Just one glass more; well, have a cigar to see you home. Will you be able to find your own way out? Good-night and thanks, or rather good morning, I should say."

All next day a man was at work installing the electric light in the rooms of the Hon. Herbert Selwyn. When he came home to dress for dinner at seven o'clock he found the man still there. A solid and stolid middle-aged man with a dull, commonplace face, ornamented with mutton-chop whiskers—the last person in the world to associate with the "tricksy spright" that is turning the world upside down and inside out.

"When will you be done here?" asked Herbert.

"Early to-morrow, sir, I expect."

"So soon? I want a man here in the afternoon at half-past four."

"That's all right, sir; they told me at our place. I'm to come back myself."

"You know your business, I expect?"

"Pretty well, sir."

"Have all the latest appliances. There will be a lady here—the Duchess of Southern—anxious to see the best that electricity can do."

"Thank you, sir. I hope to be able to satisfy her ladyship."

"Half-past four, sharp."

"Half-past four, sir. I won't fail."

It was a charming lunch, and the Duchess enjoyed it amazingly. The shutters had been closed and the room lit for the first time with electric light in honour of her visit. She quite bubbled over with admiration and enjoyment.

"It is the first time I heard her laugh since that confounded opal disappeared," the Duke confided to his brother. "She has been breaking her heart over the girl Lucy."

When the man from Voltage and Bright arrived, her Grace could not sit still any longer at the luncheon-table. She left her husband and brother-in-law in eager discussion of the chances of a Derby favourite in the Duke's stables, while she flitted like a swallow round the room, resting nowhere. The man from Voltage and Bright followed her like a slow-winged rook—dull, heavy, harmless.

"Oh, Herbert!" cried her Grace over her shoulder, "what a perfectly lovely writing-desk, so old and heavy and mysterious-looking. I'm sure there are lots of secret drawers in it."

"Don't be silly, Ethel," said her husband. But he said it pleasantly. "And don't bother Herbert; we are talking business."

"Just one word, Herbert; I'd love to have two brackets with shell lights on either side of this desk. They would set off the dainty, satiny wood splendidly."

"I leave it entirely to your taste, Ethel," he answered her carelessly. Then to the Duke: "You think it a ten to one chance?"

"I'd like two lights here and here," she said to the man from Voltage and Bright, "very pretty and new, you know."

"I'll show you the very newest thing, mum—I mean my lady," he answered stolidly. He had in his hand a pear-shaped, pear-sized lamp of thin, clear-glass. He held it by a handle, and from either side of the pear a wire ran to a large electric coil under the table. As the man made the connection a loud crackling sound was heard, and a faint, a very faint, vapour, as it were, of greenish yellow light showed in the glass pear.

"That's not what I want at all," said her Grace. "Why, I can hardly see the light."

The man handed her a kind of pasteboard cylinder, like one of the cases that music is carried in, but closed at one end.

"If you look through that, my lady, you will see it to more advantage."

Without noticing that one end was closed, the Duchess put the open end to her eyes and saw—nothing.

"This is absurd," she said; "it's quite dark."

"Wait one moment, my lady. Beg pardon, gentlemen." He turned the little ivory knob of the electric lights, and in an instant the room was pitch dark. The crackling sound still went on in the glass pear, the flickering glow was the one luminous point in the darkness. The man passed the light behind a solid carved pillar of the old desk. At the same time he moved the end of the music-case, through which her Grace still looked, till it pointed straight towards the hidden light.

Even while she looked the cardboard at the closed end grew strangely translucent, and on the luminous disc she saw a strange, dark shadow projected.

"Oh, oh!" she cried, "this is most wonderful. I see the gold setting of my opal. Quick, Reggie, come here!"

"I see the gold setting of my opal."

The crackling sound suddenly ceased, and the vision vanished. There was a muttered curse, the sound of a short struggle, ending in a sharp metallic snap. The next instant the electric lamps flashed up again, and the darkness was turned to bright light. The Hon. Herbert was lying in a heap as he had fallen back in his chair, with handcuffs on his wrists and the man from Voltage and Bright was standing over him. The Duke started furiously from his seat. "What's the meaning of this insolent foolery?" he shouted.

"It's all right, your Grace," answered a cheerful and familiar voice. "Here's the thief and there's the opal."

The Duke stared at the man in sudden amazement. The leg-of-mutton whiskers and the grey beard had disappeared. The whole face had changed its character—one might almost say its features. It was the placid, smiling face of Mr. Beck.

The detective pressed a little angle of the carved mahogany of the desk with his finger-tip. As he drew away his finger a section of the carving followed it, pushed forward at the top of a long steel needle, and showed a cavity in the thickness of the wood, tightly packed with jewellers' cotton, which he picked out and set in her Grace's white hand.

The Duchess seized and opened it with a cry of delight, for in the palm of her small, white hand her own peerless opal flickered and flamed with changing inocuous fires, rosy and violet.

But the Duke turned to his brother, who sat sulky and silent after the sharp struggle, when Mr. Beck's practised hands had slipped the handcuffs on his wrists in the dark.

"Well, Herbert," he said, with a sudden sternness of face and voice very strange to him, "what have you to say?"

"Well, Herbert," he said, "what have you to say?"

"Nothing; what's the use of saying. I came a cropper, threatened to be posted, and the quarter of a million packed tight in that opal tempted me. It was a chance those two fools were there at the time, a lucky chance for me, I thought, so I used it, if it were not for that—— But where's the use of blowing? the game is up. What are you going to do about it now? that's the question."

The Duke looked appealingly towards Mr. Beck.

"It is all right, your Grace," said Mr. Beck cheerfully; "thought you might like to keep it dark. No one knows except me."

"You will leave England at once, Herbert."

"Was going anyhow. Too hot to be pleasant now that I've missed the coin."

"I'll pay your debts."

"You can do that as you please when I've put the Atlantic between creditors and self; it's no affair of mine."

"And allow you five thousand to start straight in the New World."

"Thanks awfully."

"But if ever you show your face in England again," the Duke's voice grew stern again, "so help me God, you must settle with the law."

He turned on his heel without further word or greeting to the brother who had disgraced their blood. He drew his wife's arm within his. She was pale and bewildered, with tears shining in her wide-opened eyes.

The Duke patted the little hand that lay on his arm softly, and soothingly drew her from the room.

Mr. Beck dexterously slipped the handcuffs from the wrists of the Hon. Herbert, and followed them down the broad stairs.

There was a brougham and pair waiting at the door.

"Get in," said the Duchess excitedly to the detective. "I must hear all about it from the first. Please tell him to drive straight to the hotel, dear," she said to the Duke, as he handed her to her seat.

"You must dine with us. We have not had half time enough to thank you," said her impetuous Grace, almost pushing Mr. Beck down into one of the cosiest chairs in their private sitting-room at the Victoria Hotel. "What a cruel, cruel thing to do! I would not have minded so much except trying to put the guilt on poor Lucy and her sweetheart, and then shooting the poor young man—it was too mean. I sent her a wire the first thing after I got the opal. I should have gone on liking and trusting that awful man all my life but for you. How did you ever come to guess the truth! I could never have believed it."

"'Seeing is believing,' my lady, and you saw."

"But I want you to tell me the whole story. It was awfully clever, I know."

"There isn't any story. I was lucky, as usual, that's all."

"But how did you know the opal was hidden in the desk in Herbert's chambers?"

"But how did you know the opal was hidden in the desk in Herbert's chambers?"

"I didn't know it—at first. I thought perhaps he might keep it about him, so I laid a little plan to have him searched. I make up pretty well as an old woman, and—— But there's no use going into that. When I found he hadn't got the opal about him, I searched his chambers next, of course. But he might have beaten me even there if I hadn't called in Professor Roentgen and the X rays. I have seen many a secret drawer in my days, but nothing like that. It was not to be found by measuring or tapping, and the joining was smooth as satin even under a magnifying-glass. I had looked through the legs of tables and chairs before I came to the desk; but, of course, I was bound to see into every square inch of wood in the room before I gave out, so——"

"But how did you come to suspect Herbert at all?" interrupted her Grace.

Mr. Beck took out his pocket-book, dipped his big finger and thumb into one of the compartments, and held up something bright and shiny to the light. It was a single curly hair, auburn, flecked with white. "It was lucky, my lady, that you did not get those wires in the safe fixed. Do you know what that is?"

"One of Herbert's hairs? Where did you find it?"

"Where it had no business to be—at the bottom of your safe."

"Then you guessed?"

"Then I knew."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.