RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

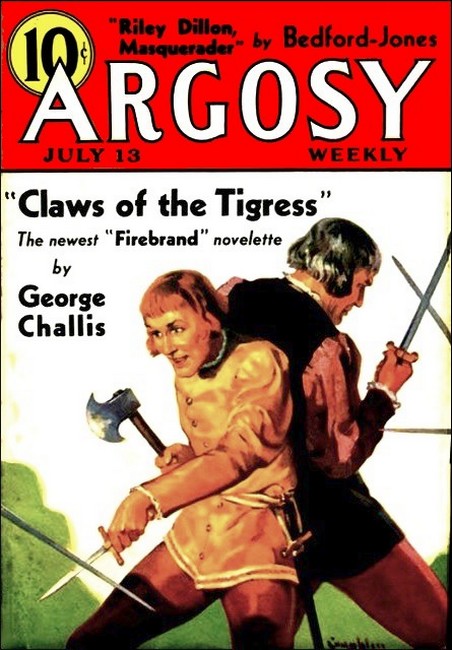

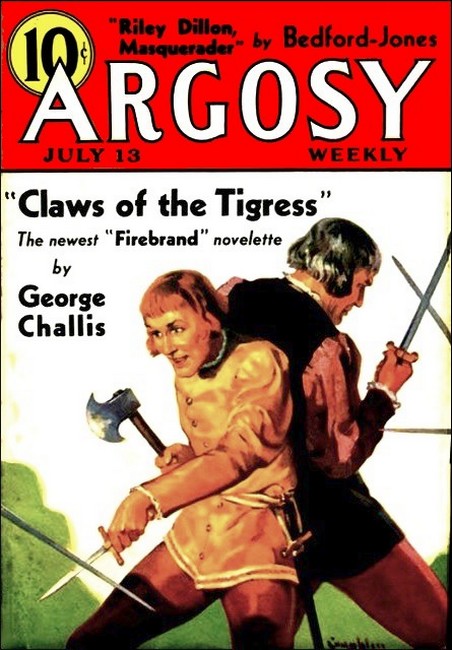

Argosy, Jul 13, 1935, with "Claws of the Tigress"

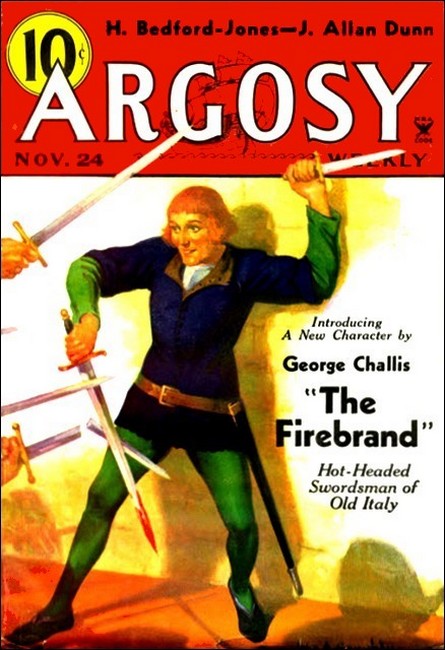

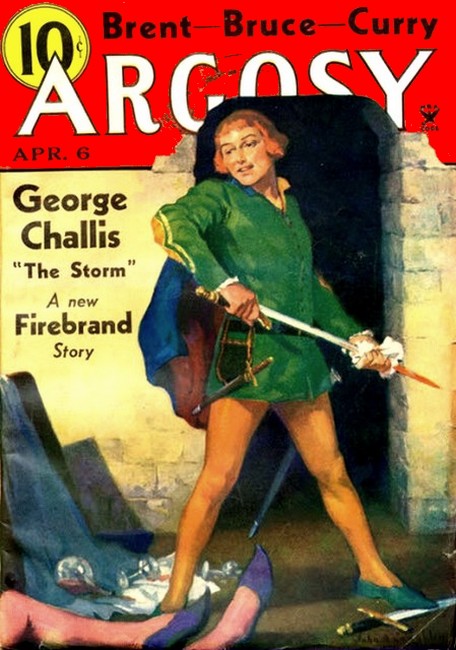

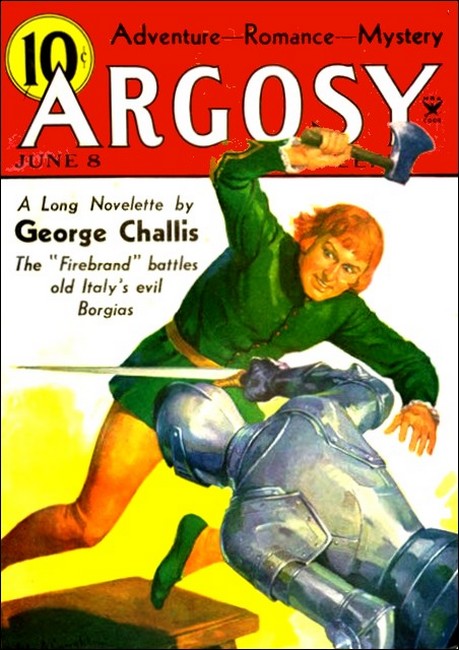

In 1934-1935 Max Brand, writing under the name of "George Challis" penned a series of seven swashbuckling historical romances set in 16th-century Italy. These tales all featured a character, Tizzo, a master swordsman, nicknamed "Firebrand" because of his flaming red hair and flame-blue eyes, and were first published in Argosy.

The original titles and publication dates of the romances are:

1. The Firebrand, Nov 24 and Dec 1 (2 part serial)

2. The Great Betrayal, Feb 2-16, 1935 (3 part serial)

3. The Storm, Apr 6-20, 1935 (3 part serial)

4. The Cat and the Perfume Jun 8, 1935 (novelette)

5. Claws of the Tigress, Jul 13, 1935 (novelette)

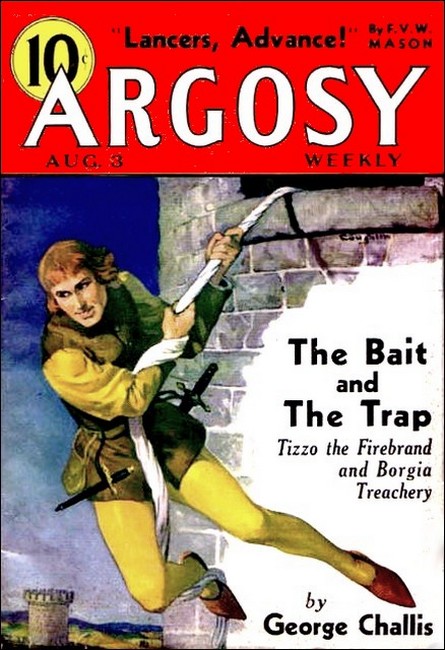

6. The Bait and the Trap, Aug 3, 1935 novelette

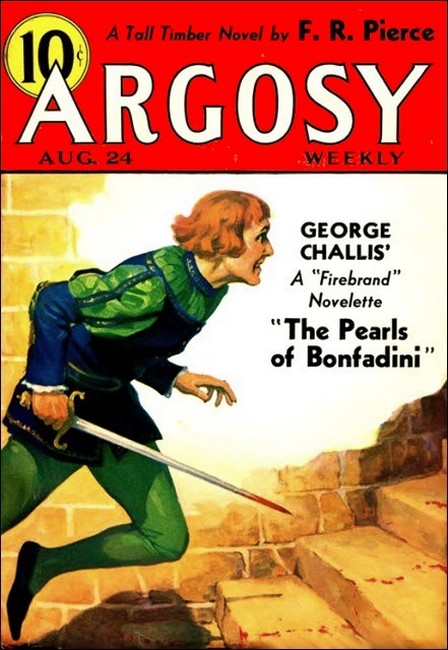

7. The Pearls of Bonfadini, Aug 24, 1935 (novelette)

The digital edition of Claws of the Tigress offered here includes a bonus section with a gallery of the covers of the issues of Argosy in which the seven romances first appeared.

—Roy Glashan, December 2019.

"The Bait and the Trap," Ace paperback edition, 1963

CATARINA, Countess Sforza-Riario, high lady and mistress of the rich, strong town of Forli, was tall, well made, slenderly strong, and as beautiful as she was wise. She used to say that there was only one gift that God had specially denied her, and that was a pair of hands that had the strength of a man in them. But if she had not a man's strength, she had a man's will to power, and more than a man's headlong courage.

She was not quite as cruel as Cesare Borgia, her neighbor to the north who now was overrunning the Romagna with his troops of Swiss and French and trained peasants, but she was cruel enough to be famous for her outbursts of rage and vengeance. That sternness showed in the strength of her jaw and in the imperial arch of her nose, but usually she covered the iron in her nature with a smiling pleasantry.

Three husbands had not been able to age her; she looked ten years younger than the truth. And this morning she looked younger than ever because her peregrine falcon had three times outfooted the birds of the rest of the hawking party and swooped to victory from the dizzy height of the blue sky. The entire troop had been galloping hard over hill and dale, sweeping through the soft soil of vineyards and orchards; crashing over the golden stand of ripe wheat; soaring again over the rolling pasture lands until the horses were half exhausted and the riders nearly spent. Even the troop of two-score men-at-arms who followed the hunt, always pursuing short cuts, taking straight lines to save distance, were fairly well tired, though their life was in the saddle.

They kept now at a little distance—picked men, every one, all covered with the finest steel plate armor that could be manufactured in Milan. Most of them were armed with sword and spear, but there were a few who carried the heavy arquebuses which were becoming more fashionable in war since the matchlock was invented, with the little swiveled arm which turned the flame over the touch-hole of the gun, with its priming.

Forty strong men-at-arms—to guard a hawking party. But at any moment danger might pour out at them through a gap in the hills. Danger might thrust down at them from the ravaging bands of the Borgia's conquering troops; or danger might lift at them from Imola; or danger might come across the mountains from the treacherous Florentines, insatiable of business and territory. Therefore even a hawking party must be guarded, for the countess would prove a rich prize.

The danger was real, and that was why she enjoyed her outing with such a vital pleasure. And now, as she sat on her horse and stroked the hooded peregrine that was perched on her wrist, she looked down the steep pitch of the cliff at whose edge she was halting and surveyed the long, rich sweep of territory which was hers, and still hers until the brown mountains of the Apennines began, and rolled back into blueness and distance.

Her glance lowered. Two men and a woman were riding along the road which climbed and sank, and curved, and rose again through the broken country at the base of the cliff. They were so far away that she could take all three into the palm of her hand. Yet her eyes were good enough to see the wind snatch the hat from the lady's head and float it away across a hedge.

Before that cap had ever landed, the rider of the white horse flashed with his mount over the hedge, caught the hat out of the air, and returned it to the lady.

The countess laughed with high pleasure.

"A gentleman and a gentle man," she said. "Here, Gregorio! Do you see those three riding down there? Bring them up to me. Send two of the men-at-arms to invite them, and if they won't come, bring them by force. I want to see that white horse; I want to see the man who rides it."

Gregorio bowed to cover his smile. He admired his lady only less than he feared her. And it was a month or two since any man had caught her eye. He picked out two of the best men-at- arms—Emilio, a sergeant in the troop, and Elia, an old and tried veteran of the wars which never ended in Italy as the sixteenth century commenced. This pair, dispatched down a short cut, were quickly in the road ahead of the three travelers, who had stopped to admire a view across the valley.

The lady countess and her companions, gathered along the edge of the cliff, could see everything and yet remain screened from view by the heavy fringe of shrubbery that grew about them.

What they saw was a pretty little picture in action. The two men-at-arms, their lances raised, the bright pennons fluttering near the needle-gleam of the spearheads, accosted the three, talked briefly, turned their horses, took a little distance, and suddenly couched their spears in the rests, leaned far forward, and rushed straight down the road at the strangers.

"Rough—a little rough," said the Countess Sforza-Riario. "Those two fellows are unarmed, it seems to me. That Emilio must be told that there is something more courteous in the use of strangers than a leveled lance."

But here something extremely odd happened, almost in the midst of the calm remark of the lady. For the two men who were assaulted, unarmored as they were, instead of fleeing for their lives or attempting to flee, rode right in at the spearmen.

One drew a long sword, the other a mere glitter of a blade. Each parried or swerved from the lance thrust. He of the long sword banged his weapon down so hard on the helmet of Emilio that the man-at-arms toppled from the saddle, rolled headlong on the ground, and reached to the feet of the horse of the lady.

She was on the ground instantly, with a little flash of a knife held at the visor of the fallen soldier.

"Good!" said the countess. "Oh, excellently good!"

She began to clap her hands softly.

The second rider—he on the white horse—had grappled with hardy Elia. Both of them were whirled from the saddle, but the man-at-arms fell prone, helpless with the weight of his plates of steel, and the other perched like a cat on top of him. His hat had fallen. The gleam of his hair in the bright sunlight was flame-red.

"And all in a moment!" said the countess, laughing. "Two good lances gone in a trice. Roderigo, you should have better men than that in your command."

The captain, scowling, and biting an end of his short mustache, swore that there had been witchcraft in it.

"Aye," said the countess. "The witchcraft of sure eyes and quick, strong hands… Did you see the lady leap from her horse like a tigress and hold her poniard above the helmet of your friend? Look, now! They are stripping the two of their armor. The big fellow is putting on that of Emilio; the redhead takes that of Elia. Roderigo, take three of your best lances. Down to them again, and let me see them fight against odds, now that they are armed like knights… Ah, what a glorious day—to go hawking for birds and end by stooping out of the sky at men!"

The four men-at-arms were quickly in the saddle and sweeping down the short, steep road; but here the countess found herself too far from the crash and dust of the battle. To gain a nearer view, she galloped after the four leaders, and the armed men, the courtiers, followed in a stream.

Those loud tramplings hardly could fail to be heard by the men in the roadway beneath; in fact, when her ladyship turned the shoulder of the cliff and could look at the scene, she found her four warriors already charging, heads down, lances well in rest, straight in on the pair. And these, in their borrowed armor, with their borrowed lances, galloped to meet the fresh shock.

Six metal monsters, flaming in the sun, they crashed together. The big fellow had lifted one of the men-at-arms right out of the saddle, but the counter-shock knocked his own horse to its knees; and at that instant the rearmost of the four men-at-arms caught the stranger with a well-centered spear that bowled him in his turn out of the saddle and into the dust.

He whose red head was now covered by steel had a different fortune. Riding straight, confident, at the last instant he dropped suddenly to the side, which caused one spear to miss him utterly, while the second glanced off his shoulder. But his own spear caught fairly on a man-at-arms, knocking him over like a ninepin.

"This is jousting!" cried the countess. "Glorious God, these are men."

He of the white horse, his spear shattered to the butt by the shock of the encounter, whirled his white horse about and went hurling against the only one of the men-at-arms who remained mounted. In his hand he swung not a sword but the old battle-ax which the veteran Elia had kept at the bow of his saddle.

In the hand of the rider of the white horse it became both a sword to parry with and a club to strike; a side sweep turned the driving spear of the soldier away, and a shortened hammer-blow delivered with the back of the ax rolled the other fellow on the road. All was a flying mist of dust, through which the countess heard the voice of a girl crying:

"Well done, Tizzo! Oh, bravely done!"

She had ridden to the spot where the larger of the two strangers had fallen, and leaning far down, she helped him, stunned as he was, to his feet. And now, springing instantly into an empty saddle, he unsheathed his sword and prepared for whatever might be before them.

There was plenty of work ahead.

The men-at-arms of the countess, swiftly surrounding the cyclone of dust, were now ranged on every side in a dense semicircle which could not be broken through. And as Tizzo saw this, he began to rein his white horse back and forth, whirling the ax in a dexterous hand as he shouted in a passion of enthusiasm:

"Ah, gentlemen! We only begin the dance. Before the blood gets cold, take my hand again. Step forward. Join me, gallants!"

One of the men-at-arms, infuriated by these taunts, rushed horse and spear suddenly on Tizzo; but a side twist of the ax turned the thrust of the spear aside, and a terrible downstroke shore straight through the conical crest of the helmet, through the coil of strong mail beneath, and stopped just short of the skull. The stricken fighter toppled from the saddle and seemed to break his neck in his fall.

Tizzo, still reining his horse back and forth, continued to shout his invitation, but a calm voice said: "Bring up an arquebus and knock this bird out of the air."

Not until this point did the lady call out: "Stay from him. My friend, you have fought very well… Pick up the fallen, lads… Will you let me see your face?"

Tizzo instantly raised his visor.

"Madame," he said, "I should have saluted you before, but the thick weather prevented me."

The countess looked at his red hair and the flame-blue of his eyes.

"What are you?" she asked.

Some of her men-at-arms were lifting the fallen to their feet and opening their helmets to give them air; by good fortune, not a one of them was very seriously hurt. The huge, heavy rounds of the plate armor had secured them from hurt as, oftentimes, it would do during the course of an entire day's fighting.

Defensive armor had outdistanced aggressive weapons. Gunpowder was still in its infancy. The greatest danger that a knight ordinarily endured was from the weight of his armor, which might stifle him when he was thrown from his horse in the midst of a hot battle.

And Tizzo was answering the countess, with the utmost courtesy: "I am under the command of an older and more important man, my lady."

He turned to his companion, who pushed up his visor and showed a battered, grizzled face in which the strength of youth was a little softened into folds, but with greater knowledge in his brow to make him more dangerous.

"I am going to take the short cut, Tizzo," said the other. "The trust is a two-edged knife that hurts the fellow who uses it, very often, I know, but here's for it. Madame, I am the Baron Henry of Melrose; this is the noble Lady Beatrice Baglione, sister of Giovanpaolo Baglione; this is my son Tizzo. We are on the road from near Faenza, where we've just escaped from the hands of Cesare Borgia, after a breath of poisoned air almost killed me. We are bound back towards Perugia. There is our story."

The countess rode straight to Beatrice and took her by the hands. "My dear," she said, "I'm happy that you escaped from that gross beast of a Borgia. How could I guess that such distinguished strangers were passing through my territory? Come with me into Forli. You shall rest there, and then go forward under a safe-conduct. My Lord of Melrose—those were tremendous blows you gave with that sword; Sir Tizzo, you made the ax gleam in your hand like your name. I thought it was a firebrand flashing! Will you come on with me? Some of the rest of you ride forward to the castle. Have them prepare a welcome… Ah, that Borgia! The black dog has put his teeth in the heart of the Romagna, but he'll fight for my blood before he has it!"

The countess, talking cheerfully in this manner, put the little procession under way again, and they streamed up the winding road toward the top of the cliff. But all her courtesy was not enough to cover the eyes of Beatrice.

Caterina of Sforza-Riario headed the riders, naturally, and Tizzo was at her right hand, more or less by seeming accident. A little back of the two came Beatrice at the side of Henry of Melrose. And the girl was saying: "Do you see how she eyes Tizzo? She is making herself sweet as honey, but I know her. She's a famous virago… How can Tizzo be such a fool as to be taken in by her? I don't think she's so very handsome, do you?"

The baron looked at her with a rather grim smile for her jealousy. "She is not worth one glance of your eyes, Beatrice," he declared. "But Tizzo would be a greater fool still if he failed to give her smile for smile. She has three birds in her claws, and if she's angered, she's likely to swallow all of us. She never was so deeply in love that could not wash her hands and her memory of the lover clean in blood. Be cheerful, Beatrice, or you may spoil everything. Smile and seem to enjoy the good weather. Because I have an idea that after the gates of Forli Castle close behind us it will be a long day before we come out again."

They passed over the green uplands and sank down into the road toward the walled town of Forli. The city itself was a place of considerable strength, but within it uprose the "Rocca"—or castle on the rock—which was the citadel and the stronghold of the town. No one could be real master of Forli until he had mastered the castle on the rock as well. And young Tizzo, riding beside the countess, making his compliments, smiling on the world, took quiet note of the mouths of the cannons in the embrasures of the walls.

The drawbridge had already been lowered. They crossed it, with the hollow echoes booming beneath them along the moat. They passed under the leaning forehead of the towers of the defense; they passed through the narrows of the crooked entrance way; they climbed up into the enclosed court of the powerful fortress.

Tizzo was the first on the ground to offer his hand to hold the stirrup of the countess. But she, laughing, avoided him, and sprang like a man to the ground. Like a man she was tall—almost the very inches of Tizzo; like a man her eye was bold and clear; and like a man she had power in her hand and speed in her foot. She looked to Tizzo like an Amazon; he could not help glancing past her to the more slender beauty of Beatrice and wondering what the outcome of this strange adventure would be.

THE courtesy of the countess might be perfect, but it was noticeable that she assigned to the three strangers three rooms in quite different parts of the castle.

The Countess Riario, stepping up and down in her room, said to her maid: "You, Alicia—you have seen him—what do you think?"

"Of whom, madame?" asked the maid.

"Of the man, you fool," said the countess.

"Of which man, madame?" asked the maid.

"Blockhead, there was only one."

There was a beautiful Venetian stand near by, of jet inlaid with ivory; and the capable hand of the countess gripped the stand now. The maid had saved herself from a fractured skull more than once before this by the speed of her foot in dodging. But she knew a danger when she saw it, and her brain was stimulated.

"There was the noble young gentleman who rode with you into the court, madame. There was he, of course. And when he took off his helmet and I saw the gold of his hair—"

"Red—silly chattering idiot—red hair. Would I waste my time looking at golden hair? Insipid nonsense—gold—in the purse and flame in the head—that's what I prefer!"

"When I saw the flame of his hair, madame, and the blue of his eyes, I understood that he was a very proper man, though not exactly a giant—"

"Judge a dog by the depth of his bite, not by the length of his muzzle," said the countess. "I saw that slenderly made fellow carve the helmet of that Giulio almost down to the skull—the helmet and the coif of mail beneath it!"

"Jesu!" cried the maid.

"And with a stroke as light and easy as the flick of a hand, the white hand of an empty girl. He is a man, Alicia. I want to send him a gift of some sort. What shall it be?... Wait—there is a belt of gold with amethyst studs—have that carried to him at once, and give him my wish that he may rest comfortably after his hard journey and the work of the fighting—ah ha—if you had seen him battling, Alicia! If you had seen him rushing among my men and tumbling them over as though they were so many dummies that had not been tied in place. The ring of the ax strokes is still in my ears. He tossed the spears aside as though they had been headless straws. It was a picture to fill the heart, Alicia… Why are you standing there like a lackbrain? Why don't you take the belt to him instantly?"

"I beg the pardon of madame… You forget that you already have given it to Giovanni degli Azurri."

"Ah—ah—that Giovanni? Is he still in the castle? Is he still in the Rocco?"

"Madame, you had supper with him last night; and dinner before it; and breakfast in the morning—"

"Did I? That was yesterday. He has a dark skin. I hate a man with a greasy skin. Besides, he talks too much! Here! Take this lute to the noble Tizzo. Tell him it is from my hand, and then we'll see if he has wit enough to sing a song with it; and through the singing, he may be able to discover that his room is not very far from mine—not very far—hurry, Alicia! Wait—give something to the others. To the baron—let me see—there was a man, Alicia. Ten years younger, and I would not have changed a dozen Tizzos for one such big-shouldered fighter. He jousts like a champion and handles a sword like a Frenchman. Have a good warm cloak of English wool carried to him. And then the girl—I hate silly faces, Alicia. I hate silly, young, witless, thoughtless faces. Do you think that young Tizzo has an eye for her?"

"One would call her pretty enough to take a young man's eye," said the girl.

"Pretty enough? Silly enough, you mean to say. Take her a dish of sweet meats with my compliments. Pretty enough? Look at me, Alicia. Tell me how I appear, now that I'm no longer a girl, in the eyes of a man."

Alicia, directly challenged in this manner, fell into a trembling so that her knees hardly would bear her up. Her glance wandered wildly out the window toward the brown and blue Apennines. If she did not tell the truth, she would be beaten; if she did not convey some sort of a compliment, she would be cast out of her sinecure which brought her a better income than any two knights in Forli possessed. The Apennines brought no suggestions into the mind of Alicia. She looked out the opposite window over the plains as far as the distant blue stream of the Adriatic.

"Madame," she said, "the truth is a thing that ought to be told."

The countess, at her mirror, viewed herself from a different angle.

"Go on, Alicia, tell me the truth," she commanded.

"The fact is, madame, that when men see you in the morning they are filled with delight; in the full light of the noonday—a time for which madame the countess doesn't care a whit anyway—a man would think you a very handsome good friend; and in the evening light, madame is always adored."

"At noon the wrinkles show, eh?" asked the countess.

"No, madame, but—"

The countess turned her head slowly, like a lioness, so that the strength of her chin and the powerful arch of her nose stood in relief against those same blue Apennines beyond the window.

"Well—" she said. "Well, run about your business. And don't forget to take the lute."

It was ten minutes later when Alicia, out of breath, tapped at a door in a certain way; and it was opened almost at once by a tall, powerfully built man in early middle age, his beard and mustaches close-cropped to permit the wearing of a helmet, his complexion swarthy, his eye easily lighted, like a coal of fire when a draught of air blows upon it.

He glanced down the hall above the head of the girl to make sure that she was alone, took her by the elbows, kissed her, and drew her into the room.

"Now, Alicia, what's the news?" he asked.

She paused for a moment to recover her breath and begin her smiling. She was a pretty girl, with pale tawny hair and only a touch of shrewish sharpness about the tip of the nose and the forward thrust of the chin. By twenty-five or so she already would begin to look like a hag.

"Trouble for you, Giovanni," she said. "In that lot of people whom the countess picked up while she was hawking, there was a red-headed and blue-eyed young fellow who has caught her eye. She sent me to him with that enameled lute as a present."

"The one which I gave to her"? exclaimed Giovanni.

"The very same one. She never can remember who has given her things," the girl said.

"I had better find a way to call the man into a quarrel," said Giovanni. "The countess will always forgive what a sword-stroke accomplishes honestly."

"Yes, of course," said Alicia. "And if the stranger should happen to cut your throat, she would bury you today and forget you tomorrow. This Tizzo of Melrose—have you heard about him?"

"No."

"Well, there is a rumor running about the castle now. One of the men-at-arms was at the taking of Perugia, when Giovanpaolo Baglione returned to the town, and this is the Tizzo who rode beside him. He does strange things with an ax. There is a story that he shore through the chains that blocked the streets of Perugia against the horsemen of the Baglioni."

"Cut through the street-chains? With an ax? Impossible!" said Giovanni.

"Just now, when the fighting men of the countess attacked him, he knocked them about, and whacked them off their horses. He is not big, but he strikes terribly close to the life every time he swings his ax; and a sword is like a magic flame in his hands. It burns through armor like the sting of a wasp through the skin of the hand."

"Ah?" said Giovanni. "That sounds like enchantment."

"It does. And the countess saw the fighting and is enchanted. Giovanni, have a good care—"

"Hush!" said he. "Listen!"

He held up his hand and began to make soft steps toward the single casement that opened out of his room upon one of the castle courts. Alicia followed him, nodding, for the trembling music of a lute had commenced, and then a man's voice began to sing, not overloudly, one of those old Italian songs which have originated no one knows when or where. Roughly translated, it runs something like this:

"What shall I do with this weariness of

light?

The day is like the eye of a prying fool

And the

thought of a lover is burdened by it.

Only the stars and the

moon have wisdom.

Of all the birds there is only a single

one,

Of all the birds one who knows that night is the time

for song.

And I of all men understand how to wait for

darkness.

Oh, my beloved, are you, also, patient?"

From the casement, leaning into the deep of it, Giovanni saw a crimson scarf of silk, with a knot tied into the center of it, drop from a window, and as it passed a casement immediately below, a swift hand darted out and caught it. There was only a glimpse of a young fellow with flame-red hair, and gleaming eyes, and laughter. Then he and the scarf he had caught disappeared.

"Did you see?" said Giovanni, drawing back darkly.

"I saw. And I had warned you, Giovanni. Something ought to be done."

"Yes, and before night. But if the devil is so apt with weapons—well, there is wine and poison for it, Alicia."

"There is," agreed the girl simply. But still she was held in thought.

"What was in that scarf?" asked Giovanni.

"A ring—or an unset jewel, with the fragrance of her favorite perfume drenching it. Giovanni, you must send him away."

"Aye, but how?"

"Well, you have a brain and I have a brain. Between the two of us we must devise something. Sit there—sit there still as a stone, and I'll sit here without moving until we've devised something. The air of Italy cannot be breathed without bringing thoughts."

TIZZO OF MELROSE, as the day turned into the night, whistled through his teeth and did a dance along a crack in the timber floor of his room. His feet fell with no noise, and always, as he bounded forward and backward, they alighted exactly on the line. It was a mere jongleur's trick, but Tizzo, when the humor seized upon him, was merely a jongleur. And one day he wanted to do that same dance high in the air on a tightly stretched rope.

A soft tap at the door stopped the dance. He stood with his balancing arms outstretched for a moment, listening, and heard a soft rustle go whispering down the outer hall and vanish from hearing. After that he opened the door and found on the threshold a little folded missive.

He opened it, and inside found the writing which most quickly made his heart leap. It was the hand of Beatrice—a little more roughly and largely flowing than the writing of that high lady, perhaps, but still so exactly like it that Tizzo did not pause to consider the differences. He kissed the letter twice before he closed the door and then read it. It said:

Tizzo:

There is frightful danger for all of us in the Rocca. But we have found an unexpected friend. Your father and I already have been smuggled out of the castle. We are waiting for you outside the town.

When you receive this letter, go straight down to the eastern court. There you will see a horse covered by a large blanket. It will be your own Falcone. The man leading it will unlock the postern for you. Go quietly through the town, keeping your face covered with your mantle and the blanket on the horse so that you will not be known. On the main road to Imola, beyond Forli, you will reach a farmhouse with a ruined stable beside it. The house will seem to be unoccupied, but go straight in through the front door and call. Your father and I are waiting.

God bless you and keep you. The countess is a devil incarnate. Come quickly.

Beatrice

Tizzo went quickly.

He clapped on his head his hat with the strong steel lining, belted his sword about him, and was instantly in the corridor. He walked with a free and careless swing. There was nothing about him to indicate that he moved with fear of danger in his mind except the silence of his step, graceful, and padding like the footfall of a cat.

He passed through a great lower hall with the hood of his cloak pulled forward so that his face was shadowed. A door opened. Somewhere music was beginning, the musicians scraping at their instruments as they tuned them. In a very few minutes the countess would be expecting to receive her guests for the great banquet.

But Beatrice was no rattle-brained girl. And if Henry of Melrose had consented to flee from the castle like a thief, then it was certain that the Countess Riario was a mortal danger to them, all three.

That was the thought of Tizzo as he passed out into the eastern court, where he saw not a living soul. He looked up at the windows, most of them dark, a few faintly illumined by the steady glow of lamps in the lower rooms, and of flickering torches above. Then, in a farther corner, something stirred. A man leading a draped horse stepped out into the pallid starlight and Tizzo went straight to him. When he was closer, the blanketed horse lifted head and whinnied, a mere whisper of sound. But it told Tizzo louder than trumpets that this was Falcone.

The fellow who led the stallion gave the strap instantly into Tizzo's hand. Not a word was spoken. The man, who was a tall figure wrapped up to the brightness of his eyes in a great mantle, fitted a key into the small postern gate. The lock turned with a dull, rusty grating; the door opened; over the narrow of the causeway Tizzo led the horse.

"Whom do I thank?" he murmured as he went through the gate.

But the postern was shut quickly, silently behind him.

An odd touch of suspicion came up in the heart of Tizzo; and at this moment he heard the whining music of strings come from a distant casement with such a sense of warmth and hospitality and brightness about it that he could not help doubting the truth of the letter of Beatrice.

This hesitation did not endure a second. He was on the back of Falcone again, his sword was at his side, his dagger was in his belt, and if only he could have in his grasp, once more, that woodsman's ax with its head of the blue Damascus steel, he would have felt himself once more a man free and armed against the perils of the world. However, the thought of Beatrice and of his father expanded before him pleasantly.

He jogged the stallion through by-streets. They were dark. Once a door opened and a tumult of voices, a flare of torches poured out into the street, brawling and laughter together; but Falcone galloped softly away from this scene and carried his master safely out of the town onto the broad surface of the famous road which slants across the entire north of Italy.

A moon came up and helped him to see, presently, a ruined farmhouse fifty steps from the edge of the pavement; the roof of the stable beside the house had fallen in through two-thirds of its length. The house itself had settled crookedly toward the ground. The windows were unshuttered. The door lay on the ground, rotted almost to dust.

Tizzo dismounted at this point and walked forward a little gingerly. The long black of his shadow wavered before him with each step he made over the grass-grown path; and that shadow like a ghost lay on the broken floor of the old house, slanting into it as Tizzo stood at the threshold.

"Beatrice!" he called.

The sound of his voice traveled swiftly through the place, came emptily back to him in an echo.

He stepped a few strides forward. Through the door, through two windows, the moon streamed into the interior. He could make out a pile of rubbish that had fallen from the wreck of half the ceiling; a huge oil jar stood in a corner; he could make out, dimly, the outlines of the fireplace.

"Beatrice!" he called again.

"Here!" shouted a man behind him. And at once: "At him, lads, before his sword's out—in on him from every side—"

Three men were rushing through the doorway full upon him, the moon flashed on their morions, on their breastplates and the rest of their half-armor such as foot soldiers usually were equipped with. They came in eagerly with shields and swords, the sort of equipment which the Spanish infantry were making famous again in Europe.

Tizzo whipped out his sword so that it whistled from the sheath. If he could get through them to the door, Falcone was outside, but only a ruse would take him that far. He ran at them with his sword held above his head, shouting a desperate cry, as though with his unarmored body he would strive to crush straight through them. And they, all as anxious to drive their weapons into him, thrust out with one accord.

He was under the flash of their swords, hurling himself headlong at their feet. Once before he had saved his life by that device. Now he was kicked with terrible force in the stomach and ribs.

The fellow who had tripped over him fell headlong, crashing. Another had been staggered and Tizzo, as he gained his knees, thrust upward at the back of the man's body. A scream answered that stroke. A scream that had no ending as the man leaped about the room in a frightful agony.

And Tizzo, gasping, breathless, rose to face the attack of the third soldier.

The strokes of the short sword might be parried; but the shield gave the man a terrible advantage and he used it well, keeping himself faultlessly covered as he drove in, calling at the same time: "Up, Tomaso! Up! Up! Alfredo, stop screeching and strike one blow, you dog. Take him behind! Have you forgot the money that's waiting for us? Are fifty ducats thrown into our laps every day?"

Alfredo had stopped his dance, but now he lay writhing on the floor; and still that horrible screeching cut through the ears, through the brain of Tizzo.

He saw Tomaso lurching up from the floor. His sword and shield would put a quick end to this battle of moonlight and shadow, this obscure murder.

Tizzo with his light blade feinted for the head of the third soldier; the shield jerked up to catch the stroke which turned suddenly down and the point drove into the leg of the fellow above the knee. He cursed; but instinct made him lower his shield toward the wound and in that moment the sword of Tizzo was in the hollow of his throat.

He fell heavily forward, not dead, fighting death away with one hand and striving to hold the life inside his torn throat with the other. Tizzo snatched up the fallen shield and faced Tomaso, who had been maneuvering toward the rear of the enemy to make a decisive attack.

"Mother of Heaven!" groaned Tomaso. "What? Both down?"

The screeching of Alfredo turned into frightful, long-drawn groaning, sounds that came with every long, indrawn breath. Tomaso fell on his knees. "Noble master! Mercy!" he said.

He held up sword and shield.

"By the blood of God," said Tizzo, "I should put you with the other two. But I was born a weak-hearted fool. Drop your sword and shield and I may give you your life if you tell the truth."

The sword and buckler instantly clattered on the floor.

"I swear—the pure truth—purer than the honor of—"

"Keep good names out of your swine's mouth," said Tizzo. "Stand up."

The soldier arose and Tizzo, stepping back, leaned on his sword to take breath. He saw the man who had been stabbed in the throat now rise from the floor, make a staggering stride, and fall headlong. He who lay groaning turned, lay on his face, and began to make bubbling noises.

"Do you hear me, Tomaso?" asked Tizzo.

"With my soul—with my heart!" said Tomaso.

"Who was to pay you the fifty ducats?"

"Giovanni degli Azurri."

"Ah?" said Tizzo. He looked back in his mind to the dark face and the bright eyes of the man who had appeared at the table of the countess for the midday meal. In what manner had he offended Giovanni degli Azurri? Undoubtedly the fellow was acting on the orders of the countess.

"Tell me, Tomaso," he asked, "what is the position of Giovanni degli Azurri in the castle of the countess?"

"How can I tell, lord? He is one of the great ones. That is all that I know, and he showed us fifty ducats of new money."

"Fifty ducats is a large price for the cutting of a throat."

"Highness, if I had known what a great heart and a noble—"

"Be silent," said Tizzo, freshening his grip on the handle of his sword.

He had to pause a moment, breathing hard, to get the disgust and the anger from his heart.

"This Giovanni degli Azurri," he said, "is one of the great ones of the castle, and a close adviser of the countess?"

"He is, signore."

The thing grew clear in the mind of Tizzo. The countess already knew that he and his father had parted from the Borgia with sword in hand. Would it not be a part of her policy to conciliate the terrible Cesare Borgia, therefore, by wiping an enemy out of his path? But she would do it secretly, away from the castle. Otherwise, the thing might come to the ears of the High and Mighty Baglioni of Perugia, who would be apt to avenge with terrible thoroughness the murder of their friend.

And Henry of Melrose? Beatrice Baglione? What would come to them?

It was a far, far cry to Perugia. Help nearer at hand must be found to split open the Rocca and bring out the captives alive.

He began to remember how, to please the fair countess, he had accepted the lute from her and sung her the love song. And a black bitterness swelled in his heart; a taste of gall was in his throat.

HIS name was Luigi Costabili; his height was six feet two; his weight was two hundred; the horse that carried him was proud of the burden. Luigi Costabili wore a jacket quartered with the yellow and red colors of Cesare Borgia, with "Cesare" written across the front and across the back. His belt was formed like a snake. He wore a helmet on his head and a stout shirt of mail.

His weapons were his sword, his dagger, and the pike which infantry used to defy cavalry charges. It was not quite the weight or the balance to serve as the lance of a knight, but still it could offer a formidable stroke or two in practiced hands—and the hands of Luigi Costabili were very practiced. Among the enrolled bands of the Romagnol peasantry who followed the Borgia there was not a finer specimen than Costabili. He knew his own worth even better than he knew his master's. Therefore he paid little heed to a slender man who rode out onto the Faenza highway on a white stallion. But when the stranger came straight on toward him, Luigi Costabili lifted his pike from his foot and stared, then lowered the weapon to the ready.

The stranger had red hair and bright, pale blue eyes, like the blue one sees in a flame. When he was close to Luigi, he called out, in the most cheerful and calm voice imaginable: "Defend yourself!" and drew a sword.

"Defend myself? I'll split you like a partridge!" said Luigi.

And he let drive with his pike. He had practised a maneuver which the master of arms said was infallible. It consisted of a double feint for the head, followed with a hard drive straight for the body. Luigi used that double feint and thrust with perfect adroitness and facility, but the sword did a magic dance in the hand of the other; the pike was slipped aside, and the white horse, as though it was thinking on behalf of its master, sprang right in to the attack. He was far lighter than the charger Luigi bestrode, but he drove his shoulder against the side of Luigi's big brown gelding with such force that man and rider were staggered.

Luigi dropped the pike, caught for the reins, snatched out his dagger, and then had his right arm numbed by a hard stroke that fell on it below the shoulder.

If that blow had been delivered with the edge, Luigi would have been a man without a right arm and hand during the rest of his days; but the whack was delivered with the flat of the blade only and the result was merely that the dagger dropped from the benumbed fingers of the big soldier.

He looked down the leveled blade of the red-headed man and felt that he was blinded. Helplessness rushed over him. Bewilderment paralyzed him as effectively as though he had been stung by a great wasp. So he sat without attempting resistance and allowed a noosed cord to be tossed over him and his arms cinched up close against his sides.

A turn of the cord about the pommel of the saddle secured him as efficiently as though he were a truss of hay.

"What is you name?" asked the stranger.

"Luigi Costabili," said the peasant, "—and God forgive me!"

"God will forgive you for being Luigi," said the other. "Do you know me?"

"I know the trick you have with your sword," said Costabili.

"I am Tizzo of Melrose," said the stranger.

Costabili closed his eyes. "Then I am a dead man," he groaned.

"Luigi, how do you come to ride such an excellent horse?"

"It was given to me by the Duke of Valentinois himself, because I won the prize at the pike drill of the whole army."

"He is going to give you a greater gift than that," said Tizzo, "if you will carry safely and quickly to him a letter that I'll put in your hands."

"I shall carry it as safely as a pigeon, highness," said poor Luigi. "But you—pardon me—you are not Tizzo. He is half a foot taller than you."

"I am Tizzo," was the answer, accompanied by a singular little smile and a glint of the eye that made Luigi stare.

"Yes, highness," he said. "You are whatever you say, and I am your faithful messenger."

"Luigi, if I set you honorably free and let you have your weapons, will you do as you promise and ride straight to the duke?"

"Straight, my lord! Straight as an arrow flies or as a horse can run... Tizzo... the captain himself!"

The last words were murmured.

In the Rocca of the town of Forli, Caterina Sforza strode up and down a tower room with the step of a man. Anger made her eyes glorious, her color was high. She looked what she was—the most formidable woman that ever gripped a knife or handled thoughts of a sword. Her passion had risen high but still it was rising.

Most of the time she glared out the casements toward the sea on one side and toward the mountains on the other; only occasionally did she sweep her eyes over the figures of the two who were before her, their hands and their feet weighted down with irons. Henry of Melrose carried his gray head high and serenely. But his jaw was set hard and his eyes followed the sweeping steps of the virago. The Lady Beatrice, on the other hand, looked calmly out the window toward the mountains and seemed unconscious of the weight of the manacles that bound her. She maintained a slight smile.

"Treachery," said the Lady of Forli, panting out the words. "Treachery and treason!"

The men-at-arms who remained in a solid cluster just inside the door of the room stirred as they listened, and their armor clashed softly. Giovanni delgi Azurri, their leader, actually gripped his sword and looked at the big Englishman as though he were ready to rush at him with a naked weapon.

"One of you or both of you know where the sneaking, hypocritical, lying thief has gone and how he managed to get out of the castle," cried Caterina Sforza.

"If my son is a thief," said the Baron of Melrose, "will you tell us what he stole?"

"My smallest jewel case with my finest jewels in it!" declared the countess.

Here the eyes of Giovanni degli Azurri glanced down and aside suddenly. And the corners of his mouth twitched slightly.

"A great emerald, two rubies, and a handful of diamonds!" said the countess. "Gone—robbed from me—stolen—by a half-breed dog! A half-breed dog!"

She stopped and stamped, and glared at the Englishman. His color did not alter as he answered without heat: "You have tied up my hands with iron, madame. But even if you had not, in my country a man cannot resent a woman's insult."

"A scoundrel!" cried the countess. "I could see it in his face. A sneaking, light-footed, quick-handed thief! Ah, God, when I remember the red heart of fire in the biggest of my rubies... and gone... gone to an adventuring, smiling, singing, damned mongrel. But I'll tear it out of you! The executioner knows how to tear conversation out of the flesh of men. Stronger men than Henry of Melrose have howled out their confessions, and I've stood by and listened with my own ears—and laughed—and listened—and laughed. Do you hear me?"

"I hear you, madame," said the big Englishman.

He looked steadily, gravely, toward the sinister grin on the face of Giovanni degli Azurri.

"Will you tell me now," demanded the countess, "where Tizzo has gone? Or must the rack stretch you first? Will you tell me what poisonous treason enabled him to get out of my castle without permission?"

"Could no one else have let him go?" asked Melrose.

"Giovanni degli Azurri," said the countess. She turned and fixed a blazing eye on the face of her favorite.

But Giovanni smiled and shook his head. "Is it likely that I'd steal the jewels of your highness and give them to that redhead?" he asked. "Had I any special reason for loving him?"

"No," declared the countess, convinced suddenly and entirely. "No, you had no reason. But treachery was somewhere in this castle. Treachery is still here, so complete that it is trusted in. So complete that one of them sneaks away with his theft and two of the others remain behind—confident that they can flee away when they please—God—I stifle when I think of it! I am made a child—a child—"

She strode across the room and buried her grip in the bright hair of Beatrice. A jerk of her hand forced the head of the girl back, but it did not alter her expression, which remained calm, half-smiling.

"If the Englishman has the strength to hold out in the torture-room," said the countess, "how long will your courage last, eh? How long before you will be squealing and squawking and yelping out everything you know?"

"Try me, then," said the Lady Beatrice. "Take me down, quickly. Heat the pincers. Oil the wheels of your rack."

The countess relaxed her grip and stepped back. She began to stare with narrowed eyes into the face of the girl.

"There's as much as this in you, is there?" she asked.

"I am the sister of Giovanpaolo Baglione," said the girl. "And I shall be the wife of Tizzo. And what can you rats of the Romagna do to the old Perugian blood?"

The countess struck with a powerful hand, twice. The blows knocked the head of Beatrice from side to side. Her hair loosened and rushed down, streaming over her shoulders; but her eye was undimmed.

"What a fool you are!" she said to Caterina Sforza. "Do you think that you can break me with your own hands? Take me to the wheel. Stand by and watch the rack stretch me. Then use the bar and break me, while I laugh in your face—and sing—and laugh!"

"Take her! Now! Take her! Giovanni, drag her by the hair of the head down to the dungeon rooms."

Giovanni degli Azurri made two or three eager steps across the room before the sudden thunder of the voice of Melrose shocked him to a pause.

"Do you forget the Baglioni?" Melrose shouted. "Do you know that Perugian banners will be flying all around your town of Forli within a month? Do you know that when the walls of the Rocca are breached a river of blood will run out of the gap? I say, for the two blows that have struck her face, two hundred of your men will die, madame!"

The countess stared curiously at Melrose, half her passion almost instantly gone.

"Take the girl—but not by the hair of the head," she said to Giovanni degli Azurri. "And now away with you. Let me stay here a moment with the baron, alone."

The girl walked uncompelled toward the stairs. From the head of them she smiled back over her shoulder toward Melrose.

"We'll find each other again," she said.

"We shall, by the grace of God," said the Baron.

"I'd put a quicker trust in Tizzo," said Beatrice, and then the crowd of mailed fighting men formed about her and their descending steps passed down the stairs. Giovanni degli Azurri, going down last, called out: "Are you safe with him, alone?"

The countess pulled from her girdle a dagger with a seven-inch blade, the light dripping from its keenness like water from a melting icicle. "This is enough company for me," she said. "See the girl safely locked up before you come back."

When Giovanni was gone, she turned to Melrose again. The last of her passion was falling away from her, though she still breathed deep.

"My lord," she said to Melrose, "what was the mother of Tizzo?"

"An angel out of the bluest part of heaven," he answered.

"Is the thief's blood in you, then?"

"He would no more steal from a woman than he would lie to the face of the Almighty."

"But the jewels are gone, and he has gone with them—and behind him he leaves in my grip his father and his lady. You, my lord, are a brave man; but your son is a dog. I prove it to you by the things he has done. Can you make an answer?"

The face of the baron grew very pale. He said: "Madame, what you say seems to be true. He was here—and now he is gone. I tell you my answer. You see my right hand. Well, this hand is not such a true servant to me, or so close to my blood, as my son is. That is all I can say."

"So? Well—perhaps you are right. Perhaps you are right. But your face is a little too white, my lord. I think that strange things are happening in the Rocca and that you know something about them. And the executioner will ask you questions on the rack. I am sorry to say it. You have an old head and a young eye. I am very sorry for you. But—your blood in your own son condemns you... If I could put hands on him, I would eat his heart—raw! And I shall have my hands on him. You've heard me shouting and raging like a fool. But I can be quiet, also. You will see that I keep to my promise, letter by letter."

"Madame," said Melrose, "I am young enough to be afraid of you; but I am old enough not to be afraid of death."

She looked at him with a smile that was almost pleasant.

"I like that. There's something neat in what you say. Will you speak as well when you're on the rack?"

"I hope so."

"Go before me down the stairs, then," said the lady. "For once be discourteous to a lady and walk before her. Thank you. I'm sorry that the irons make your step so short... Take care, my lord, and don't let yourself fall on the stairway. What a pity if such a wise and elderly gentleman should be hurt by a fall, in my house!"

She began to laugh, and the sweet echoes of her laughter ran before them down the steep stairs and came softly back from below.

CESARE BORGIA lay on his back in the sun with a mask over the slightly swollen deformity of his upper face, his eyes closed, his attention fixed on nothing but the stir of the wind in the grass about him, and the clean fragrance of moist earth and flowers, and the weight of the sun's heat pressing down upon him, soaking through his clothes, through his body.

Beside him, always standing erect, was Alessandro Bonfadini, the pallor of whose face would never be altered by all the sunshine that pours out oceans of gold over Italy every summer. Men said that his body was so filled with the poisons which he took as preventatives in the service of his dangerous master that neither sun nor air could work upon him as it worked upon other men. It was even said that, when he sat in a perfectly dark room, a dim halo was visible creeping out of his skin—a thin, phosphorescent glimmering which could be just noted. So that he seemed, in the darkness, like a ghost of a ghost.

And even in the broad daylight, one could not look at his cadaverous face without thinking of death.

The door to the walled garden of the tavern opened. An armored soldier called: "Bonfadini! Bonfadini!"

Bonfadini turned and waved a hand to command silence. But the soldier persisted: "A message from Captain Tizzo..."

The Borgia leaped suddenly to his feet.

"From Captain Tizzo?" he exclaimed. "Bring the man to me instantly."

He went striding off with great steps, a huge man, startlingly powerful the moment he was in motion. Through the silk of his hose, the big calf muscle slipped or bulged like a fist being flexed and relaxed.

Before him, voices called orders that were repeated far away. And Bonfadini ran to keep close to his master.

They were halfway through the garden before Luigi Costabili appeared, with the dust of his hurried ride still white on his uniform. He was busily trying to dust off that white when he saw the duke and fell on his knees.

"Get up and don't be a fool," said the Borgia. "Soldiers kneel to their king or their God; but in the Romagna my men in armor kneel to nothing but a bullet or a sword stroke. Stand up, and remember that you are a man. Have you seen Captain Tizzo?"

"I have here a letter from him. I met him on the high road."

"Why didn't you arrest the traitor and bring him here?" asked the Borgia.

His voice was not angry, but the peasant turned a greenish white.

"My lord, I tried to arrest him—but I was prevented—"

"You had bad luck with him and his sword," said the Borgia. "Well, other people have had bad luck with that will-o'-the-wisp. Bonfadini, read the letter to me. Was Captain Tizzo alone? On the white horse, Falcone? Was he well?"

"Alone, my lord—there was no one with him—he seemed—I don't know, my lord. He doesn't seem like other men."

"He is not like other men," agreed the Borgia. "Because you brought me a letter from him, here is five ducats…"

"My lord, I thank you from my heart; you are very kind."

"…and because you failed to bring the man himself—holla! Lieutenant! Catch this fellow and give him a sound flogging!"

Luigi was led off.

"Read! Read!" said the Borgia, and began to walk up and down in a great excitement.

The white face of Bonfadini, unalterable as stone, slowly pronounced the words of the letter:

"'My noble lord: I left you the other night in such a hurry that I hardly had time to tell you why I was going. And certainly I did not know where. The only thing that was obvious was that my father was fighting for his life, and then running for his life. Since then, I've heard something about a moonlight night, a dead cat, and poison in the air. It seems that my father, not knowing as I do the excellent heart of your highness, grew a little excited…'"

"Good!" said the Borgia. "Not knowing as he does, eh? Ah, Bonfadini, there is a red devil on the head and in the heart of that Tizzo that pleases me. I wish I might have him back with me again."

"Would it be wise, my lord, since he knows that his own father was almost poisoned in your house?"

"But not by my orders, perhaps. Who can tell?"

"Yes," said Alessandro Bonfadini, "who can tell?"

"Continue the reading."

Bonfadini went on:

"'First he warned Lady Beatrice to leave the tavern. His mind was half bewildered by the effects of the poison. He looked for me, failed to find me, and then went on with the next part of his program, blindly. You, my lord, were to die. He went straight to your room, broke into it, and, at the moment when I heard you call out for help, was about to cut the head of your serene highness from your noble neck. You may recall the moment when I got to the spot. It was one thing to realize it…'"

"True!" said the duke. "Very true, Alessandro. When he ran in, I was on one knee, desperate. The big Englishman fenced like a fiend. But then Tizzo flashed in between us, and took up the fight. Even Tizzo could not win quickly, however. Have I showed you how they leaped at one another? Until by the flashing of their own swords, I suppose, they recognized one another—otherwise it would have been a sweet bit of family murder in my room that night."

The duke began to laugh.

"Shall I continue, my lord?" asked the cold voice of the poisoner.

"Get on! Get on!" said the Borgia. "It warms my heart even to think of that cat-footed, wild-headed, fire-brained Tizzo. Was there ever a name so apt? The spark—the spark of fire—the spark that sets a world on fire—that's what he is!"

The poisoner read:

"'However, the three of us managed, as you know, to escape from the hands of your men; we rode like the devil across country and found ourselves in the morning of the next day surrounded by the men-at-arms of the Lady of Forli. You know her, of course. She's a big creature, handsome, with a good, swinging step, and a hearty laugh and an eye that brightens wherever it touches. But a twist of strange circumstances made her decide that I would be better under ground than above it. Unlike your tactful self, she used three murderers instead of a whiff of poisoned fragrance on a moonlight night. However, the moon helped me. I danced with the three of them till two fell down and the third was willing to talk. He told me a story that leaves my blood cold and my skin crawling.

"'My lord, I am safely out of Forli. But inside of it remain the two people I love—my father and my lady. To ride to Perugia is a long journey; and it would take them a long time to attack Forli from that distance.

"'But your highness is within arm's stretch of Forli. You easily can find the will to attack the place. It is just the sort of a morsel that would slip most easily down your throat. The Rocca, if you haven't seen it, is an excellently fortified place, but your cannon will breach its walls. However, what I hope is that a night march, a night attack might sweep all clean. And God will give me the claws of a cat to climb those walls and come to the help of my lady.

"'Do you need to be persuaded further? Is not my lord's heart already twice its usual size? Is not your mouth watering and your brain on fire?

"'Well, I can offer nothing of great value, because I have spent my fortune as fast as it was showered on me. I hate to use pockets or hang purses around my neck, and therefore I have no place to carry money.

"'However, my lord, I have one thing remaining, and it shall be yours. Will you have it? Two hands, two feet, and a heart that will never weaken in your service.

"'For how long shall I serve you? That, my lord, is a bargaining point. The devil might demand my service for life. But the Borgia, perhaps, will let me off with three months. For three months, my lord, I am at your beck and call, but there are certain slight conditions that I would like to make and certain little Borgian duties which I would avoid as, for instance,

item... stabbing in the

back

item... poison in wine or elsewhere

item... midnight

murder in the dark

but otherwise, I am completely yours.

"'If my lord chooses me and my service on these terms, he may ride out of the tavern and take the road toward Forli. I shall be waiting to meet him if he is accompanied by not more than two men-at-arms.

"'Ever my lord's faithful servant and obedient friend—Tizzo.'"

The Borgia began to laugh again. "Where is the Florentine secretary?" he asked. "Where is Machiavelli? Call him down to me here and let me have his advice on this letter and its writer. This Machiavelli has a young brain but a good one."

Accordingly, a young man dressed all in black entered the garden a moment later. He was of a middle size, and when he took off his hat to the duke, he showed a head of rather small dimensions, covered with glistening black hair. His lips were thin and secret. Perhaps it was they that gave a slight touch of the cat to his face. His eyes were very restless, very bright.

"Niccolo," said the duke, "here is a letter. Read it and tell me what to think of the writer."

Machiavelli read the letter half through, raised his head to give one bright, grave look to the duke, and then continued to the end.

After that he said, without hesitation: "If this is an elderly adventurer, I'd have him put out of the way as soon as possible; if it is a low-born man, have him thoroughly flogged where ten thousand men may hear him howl; but if he is young and well-born, I would attach him to me at any price."

"Good," said the Borgia. "Machiavelli, you have a brain that the world will hear from one day. There is something about you that pleases me beyond expression. Do you notice that he is willing to meet me if I don't bring with me more than two men-at- arms? That's characteristic of this Tizzo. If the odds are only three to one, he feels at home... Horses! Horses! Machiavelli, you and Bonfadini alone shall ride out with me to meet this red- headed fellow."

THEY rode straightaway from the tavern, the duke giving orders for the company of Tizzo's Romagnol infantry to be gathered at once. And with that word, behind, the Borgia rode on between Machiavelli and Alessandro Bonfadini. In his hand, Cesare Borgia carried a naked ax that looked like the common ax of a woodsman, except that the color of the steel was a delicate blue. They had not gone down the road for a mile when something white flashed behind them from a tuft of willows and a rider on a white stallion was in the way to their rear.

The Borgia called out and waved the ax over his head.

"That's Tizzo," he said. "As wary as a cat, and as dangerous as a hungry tiger. I tell you, Machiavelli, that if he thought any great purpose would be served by it, he would ride at us and put his single hand against the three of us."

"He may be a very sharp tool," said Machiavelli, "but he will be in the hand of a very great artisan."

At this, the Borgia smiled. He rode out ahead of the other pair, and Tizzo came to meet him, doffing his hat, then closing to take the hand of the Duke of Valentinois. The duke kept that hand in a great grasp.

"Now, Tizzo," he said, "I have you. I accept your own terms. Three months of service. And this evening I start with my army for Forli. It is, as you suggest, a morsel of exactly the right size to fit my throat. But what if that hardhearted devil of a Caterina Sforza murders her prisoners before we can storm the walls of the castle?"

"Aye," said Tizzo, "I had thought about that, too. What other chance can I take, though?"

"Here is Bonfadini whom you remember well," said the duke.

"My father remembers him better, however," said Tizzo, looking grimly at the stone-white face of the poisoner.

"And here is my friend and adviser, good Niccolo Machiavelli. He has come from Florence to look into our ways."

"He will find many wonderful things," said Tizzo dryly.

But the Borgia merely laughed; for his spirits seemed high from the moment he had read the letter of Tizzo. "Ride on ahead of us," he said to Tizzo. "There are your Romagnol peasants that you were forming into good soldiers. They haven't forgotten you. Go on to them. They're good fellows and they love you."

A swarm of the peasants, bright in the red and yellow quarterings of the Borgia, had poured across the road from the tavern. Tizzo galloped his white horse toward them and was greeted by a loud shouting of: "Duca! Duca!" in honor of the duke, followed by a thundering roar for Tizzo, the captain.

"Now that you've seen him," said the duke to Machiavelli, "what do you think of him?"

The young statesman said: "That is the sort of a sword that I would leave in the scabbard until there was straightforward work to do."

"Perhaps. His men love him. Do you see them swarming and throwing up their hands in his honor? Now they have him off his horse and carry him on their shoulders... He has taught them to shoot straight, fence, and obey orders. They love him because he has made them stronger men. I tell you, Niccolo, the day may come when every Italian will love me because I have made Italy a strong nation."

"The virtues of age," said Machiavelli, "outweigh the sins of youth, always. Today is greater than all the yesterdays."

"They still shout themselves hoarse. I knew they were fond of him, but this is devotion. Such a man could be a dangerous force in an army, Niccolo."

"When a tool has accomplished its purpose," said Machiavelli, "it should be broken before it is thrown away."

The Borgia glanced aside at him, and then, slowly, smiled. Bonfadini was smiling also.

That blue-headed ax of steel which the Borgia had carried to the meeting on the road by Faenza was once more in the hands of Tizzo. His sword was at his side. The white horse stepped lightly beneath him. He was not cased from head to foot in complete steel, as most mounted soldiers were, but wore merely an open helmet, or steel cap, with a breastplate and shoulder-pieces. Equipped in this light manner, he was a lighter burden for his horse when he rode and, on the ground, those quick-thinking feet of his would be able to dance more swiftly.

The dance itself would not be long in starting.

The dawn had not yet commenced but it would not be long delayed; and Tizzo's peasant soldiery, armed with arquebuses and pikes and short swords, moved behind him with a steady thrumming of feet.

He had been given the vanguard; a mile back of him came the French soldiers with the famous Swiss pike-men behind them; and last of all, at such a distance that the rumbling of its wheels could not be heard, moved the clumsy artillery which might have to batter down the gates of the town if Tizzo could not take them with the first rush.

Another rumbling, a growing thunder, was beginning to come down the road at a walking pace toward Forli, and Tizzo reined back his horse to ask what the noise might be.

"The carts of the farmers bringing in produce for the markets," said one of the peasant soldiers. "They load their carts in the evening, and they start in the darkness so as to get to Forli just before daybreak. The market must be opened at sunrise, you see."

"Carts—sunrise—produce... Perhaps those carts will carry something more than vegetables when they get through the gates of Forli. Down in that ditch, every man of you. Do you hear? If one of you stirs, if one of you coughs or sneezes, if one of you allows the head of a single pike to shine in the moonlight, I'll have that man's head on the ground at my feet."

He saw his column sink down out of sight into the ditch. And suddenly he was alone in the road with the brilliant moonlight flooding about him and Forli lifting its gilded shoulders in the distance.

He could see the fort of the Rocca looming above the city.

With a hundred men to surprise such a place? He felt as though he had empty hands.

He passed on a short distance toward the town, then turned his horse and let it jog softly back up the road. The carts were in view, now, a whole score of them trudging along, the owners walking at the heads of the horses, the carts piled high with all sorts of country produce; the squealing of pigs sounded, and now and then the drowsy cackling and cawing of disturbed chickens as the carts rolled over a deeper rut or struck a bump with creaking axles.

Tizzo held up his hand when he came to the first cart.

"Halt there, friend!" he commanded.

"Halt yourself and be hanged," said the Romagnol. "We're already late for Forli. What puts you on the road so far from a warm bed at this time of the morning?"

Two or three of the other peasants ran up with clubs in their hands to join in any altercation that might follow, but Tizzo knew these hardy Romagnols too well to interfere with them in this fashion. He reined the white horse aside and called out: "Up, lads, and at them!"

The thing was ended in one rush, Tizzo's voice calling: "Hands only! No daggers or swords! Don't hurt them, boys!"

So it was done, in a moment; the tough Romagnols, overwhelmed by numbers, were quickly helpless, and over the brief babbling noises could be heard only the voices of several of the farmers' wives, crowing out their laments as they sat up on the tops of the loaded carts.

Tizzo brought quiet.

He rode up and down the line, saying cheerfully: "Friends, you have been robbed and cheated and taxed by the Countess Sforza- Riario for a good many years.

"Here I am with some of the men of the Duca. If I open the gates of the town with your help, it will belong to Cesare Borgia before midday. Do you hear me?"

A man growled out the short answer: "Why change one robber for another?"

"The Duke of Valentinois and the Romagna does not rob peasants," said Tizzo.

"All dukes are robbers."

"Of course they are," answered Tizzo, chuckling, "but this one only robs the lords and ladies and lets the peasant alone. For the food that his troops need, he pays hard cash."

The readiness of this reply and the apparent frankness of it brought a laugh from the peasants.

"I leave you your cartloads unharmed," said Tizzo. "I put a ducat in the hand of every man of you. I leave your women behind you on the road, here. I throw a few of my men into each cart, and we roll on through the gates. Do you hear? If we pass the gates unchallenged, all is well. If one of you betrays us, we cut your throats. Is that a bargain?"

And one of the peasants answered with a sudden laugh: "That's a soldier's true bargain. Come on, friends! I'd as soon shout 'Ducal' as yell 'Riario!' Let's take the bargain; because we can't refuse it!"

CATERINA, Countess Sforza-Riario, gathered a big woolen peasant's cloak more closely about her and raised the lantern so that she could see better the picture before her. It was the Baron of Melrose, naked except for a cincture, and lashed up by the hands so that his toes barely rested on the floor. In this posture he could support his entire weight only for a few moments on the tips of his toes, after which the burden of his body depended from his wrists.

He had been lashed there long enough to be close to exhaustion and now a continual tremor ran through his body, and the big muscles of his legs twitched up and down, and shudderings pulled at the tendons about his shoulders. But still his gray head was carried straight.

The countess broke off a bit of bread and ate it, and then swallowed a bit of wine which a page offered her on one knee, holding the silver salver high.

"How long before the strength goes out of his legs?" she asked. "How long before he hangs from the wrists like a heavy sack tied up by the two ears?"

A tall, powerful man stepped out of the shadows a little and looked more closely at the prisoner. He reached up and felt the shoulder muscles of Melrose, then the trembling, great muscles of the thighs.

"He'll endure until not long after dawn," said the executioner.

"And how long after that, Adolfo, before the tendons begin to pull and break in his shoulders?"

"He is a heavy man," said the executioner, "but he is well muscled. You see that right arm, particularly?"

"That's the arm of a swordsman," said the countess. "And I hear that he's a famous fellow with a sword."

"After the middle of this morning, he never will be famous again," said Adolfo.

"Will his arms be ruined?"

"Forever," said Adolfo. "Until he dies, he will have to be fed, like a baby."

"Do you hear that, my lord?" asked the countess.

Melrose looked at her, with the sweat of the long agony running down his face. He said nothing.

"There is something Christian in the sight of suffering like this," said the countess. "After watching you, my lord, I'll be able to say my prayers with more feeling, for a long time."

"Of course you will," said the executioner. "I always go to church after I've killed a man in here."

He looked without a smile over his domain, the gibbet-like beams that projected from the wall, here and there, and the iron machines with projecting spokes, the iron boots, also, together with the little wedges which are driven between the metal and the knee, gradually crushing the bone as wedge after wedge is added. And there were other devices such as strong gloves which pulled on easily but were fitted with fishhooks inside; in fact, there were a thousand little devices that helped Adolfo to play on human flesh and nerves like a great musician.

But best of all, the foundation of all the most perfect torments, was the great rack, whose sliding beams could be extended through the pressure exerted by a big wheel which worked against a screw. Here the body could be drawn out to the breaking point—or literally torn in two. But, when the flesh was all taut, the accepted practice was to strike the limbs and the joints one by one with a small iron bar, so breaking the tensed bone with ease. Sometimes the leg and arm on one side would be wrecked forever before the prisoner "confessed." Sometimes both legs went. Sometimes a single stroke of the bar made the screaming victim begin to shriek out whatever he could remember, whatever he could invent—anything to end the torture.

Adolfo, looking over his possessions, had good reason to smile. He felt like a miser in the midst of his hoard.

"How long will it be before dawn?" asked the countess. "Very often they go to pieces when the gray of the morning commences to strike their faces."

"Another half-running of the hour glass, highness."

"Very well."

"No, it is beginning even now," said the jailer.

"The day is about to commence," said the countess to Melrose. "Will you tell me now, my friend, where I'll be able to find Tizzo, and who it was in my castle that let him go free from it?"

Melrose, staring at her, parted his lips as though to speak, but he merely moistened them and set his jaws hard again. His eyes were commencing to thrust out from his head under the long- continued pressure of the torment.

Here a confusion of tumult broke out in the town.

"What's that?" asked the countess. "Are my silly people starting a fiesta before sunrise?"

Adolfo, running to the casement, leaned into it and listened. He started to cry out: "This is no fiesta, highness, but a trouble of some—"

But here the countess herself cried out: "Do you hear it? They have passed the wall—they have broken into Forli. Oh, the careless, treacherous, hired dogs that are in my army! Do you hear?... Ring the alarm bells. Call for—"

The uproar was washing rapidly across the lower level of the town, and the voice of the crowd streamed like a flag across the mind of Melrose. He could hear the shouting grow from confusion into syllables that were understandable: "Duca! Duca! Tizzo! Tizzo! Tizzo!"

It seemed to him that the voices were pouring from his own throat in an ecstasy. And in fact they were. He was shouting involuntarily: "Tizzo! Tizzo! Tizzo!" and he began to laugh.

The countess had jerked a door open and was crying orders to the men-at-arms who waited outside it; Aldolfo leaned, fascinated, at the casement and still was there when the countess slammed the door and hurried back into the torture chamber.

"The red-headed wildcat has come into Forli to claw us all to death!" cried the countess. "Set his father free—quickly, Adolfo! Suppose Tizzo dreamed what had been happening here—he would make the stones of the Rocca melt away and come in at us with all his devils behind him."

Melrose, released from the ropes that held him, leaned feebly against the wall, breathing hard, his head for the first time bowed.

"Have him taken to the Lady Beatrice," said Caterina Sforza. "Guard them both as you would guard the balls of your eyes. Hai! How they yell in the streets! Are the Borgia and Tizzo saints and deliverers to my own people? Ah, if I were only a man—but today I shall be a man!"

The day had in fact begun, the green gray of the dawn glowing on the edge of the sky as she ran from the room and down the stairs.

Adolfo was saying: "Noble Signor Melrose, you will never forget that I have done nothing for my own pleasure, but all by command? Lean on me, highness. Step slowly. So! So!"

IT would not be many minutes now, Tizzo knew, before the rioting soldiery of the duca had penetrated into every part of the castle; and somewhere in the Rocca were his father and Beatrice. They must be reached at once.

It was true that the Borgia controlled his men carefully during nearly every emergency, but when a stronghold had been taken by open assault, there was only one sort of a reward that could be offered to the victors—the sacking of the place. And when the wild-headed victors found women—

Tizzo looked grimly over his little group of prisoners. There was one elderly fighting man with a grizzled head, his face now as gray as his hair. Tizzo took him by the arm with a strong hand.

"In the Rocca," he said, "there are two prisoners. One is the Englishman—the big Englishman with gray hair and a red face—the Baron Melrose. And there is a girl—Beatrice of the Baglioni. Do you know where they may be kept, now?"

A dull eye rolled toward the face of Tizzo in utter lack of comprehension. Fear had benumbed the brain of the prisoner. Tizzo used the most powerful stimulant known to the Italian mind. He snatched a handful of silver out of his purse and jangled the ducats in front of the man.

"This money goes to you, if you can tell me where they're apt to be found. If you can lead me to them before some of the raiders reach them—you get this money today and a whole purse of it tomorrow."

The man opened his mouth and eyes as though he were receiving both spiritual and mental food.

"I think I know where they could be found," he said. "Follow me, highness. Quickly, because they may be on the opposite side of the Rocca."