RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

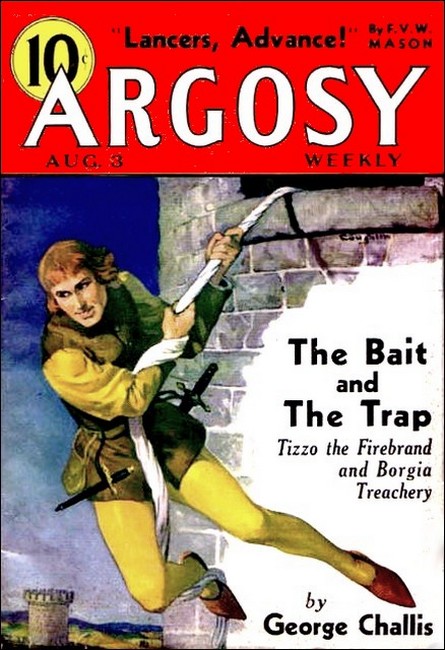

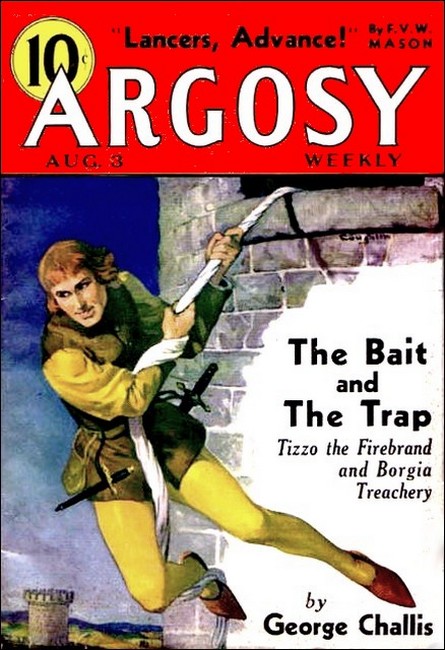

Argosy, August 3, 1935, with "The Bait and the Trap"

In 1934-1935 Max Brand, writing under the name of "George Challis" penned a series of seven swashbuckling historical romances set in 16th-century Italy. These tales all featured a character, Tizzo, a master swordsman, nicknamed "Firebrand" because of his flaming red hair and flame-blue eyes, and were first published in Argosy.

The original titles and publication dates of the romances are:

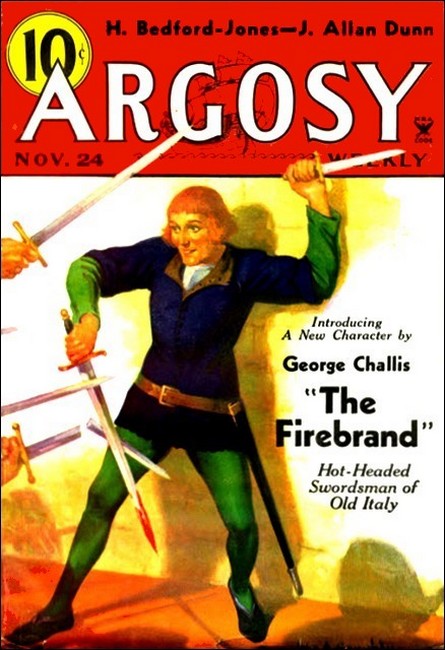

1. The Firebrand, Nov 24 and Dec 1 (2 part serial)

2. The Great Betrayal, Feb 2-16, 1935 (3 part serial)

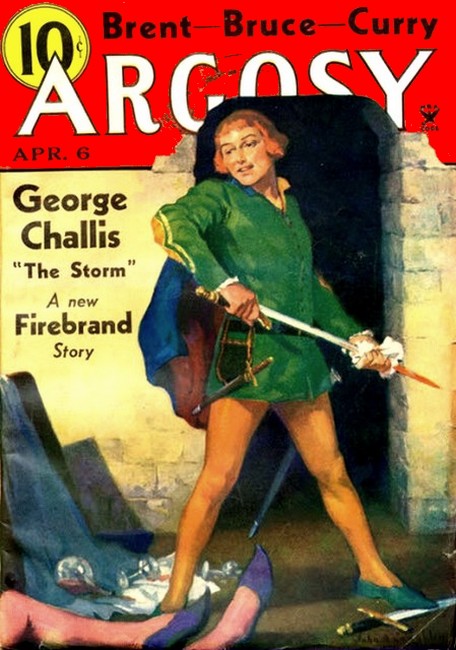

3. The Storm, Apr 6-20, 1935 (3 part serial)

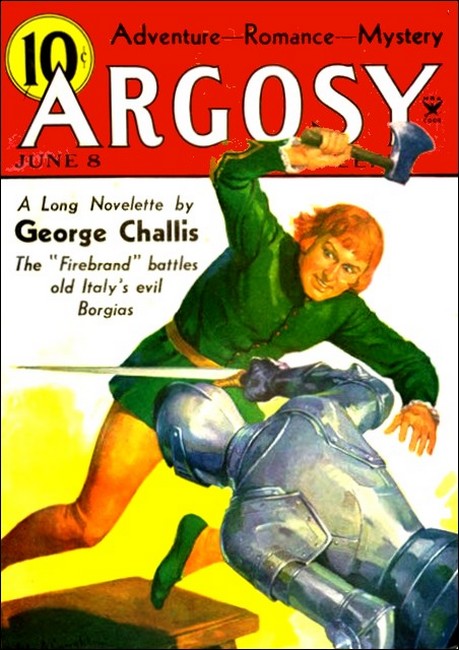

4. The Cat and the Perfume Jun 8, 1935 (novelette)

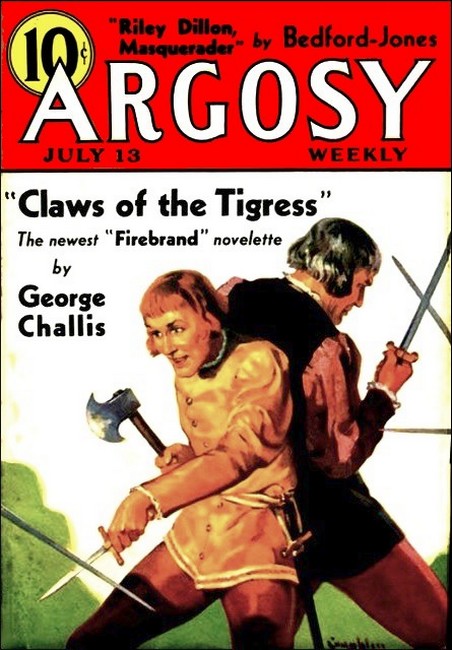

5. Claws of the Tigress, Jul 13, 1935 (novelette)

6. The Bait and the Trap, Aug 3, 1935 novelette

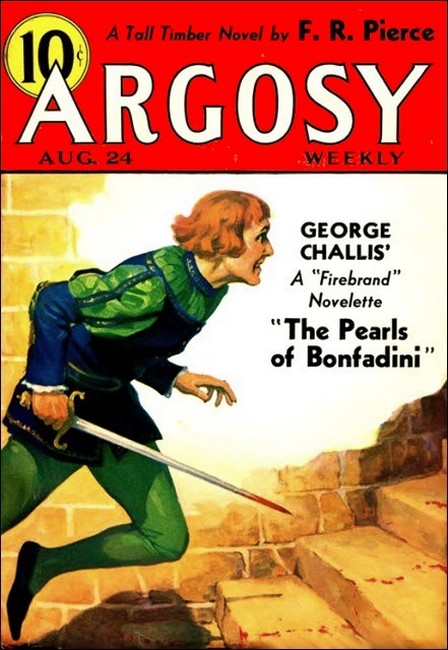

7. The Pearls of Bonfadini, Aug 24, 1935 (novelette)

The digital edition of The Bait and the Trap offered here includes a bonus section with a gallery of the covers of the issues of Argosy in which the seven romances first appeared. —Roy Glashan, December 2019

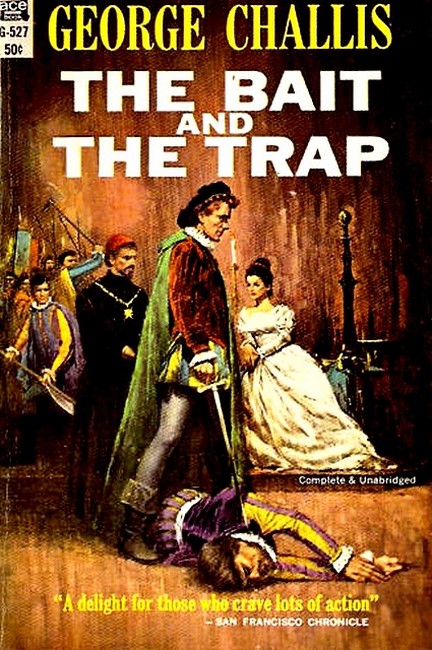

"The Bait and the Trap," Ace paperback edition, 1963

THE Borgia lay on his bed on his back, with a cloth soaked in cooling lotion covering his face down to the bearded chin and lips, because the upper portion was troubled by a hot eruption. Now and then white-faced Alessandro Bonfadini, soft-stepping, thin-fingered, changed the cloth for a fresh one. Except during those moments when the change was made, the duke of the Romagna remained blinded.

He was saying: "Niccolò, look on the map that's spread out on the table and tell me what you see on it; tell me where my next step should take me."

The young Florentine, stepping to the table, looked at the big map which was spread on it.

"I see all your conquests are tinted red, my lord," said Machiavelli. "You want to know in what direction your next step should take you."

"Yes. In what direction should the red begin to flow now."

Into some adjoining territory so that it will make a solid mass of territory under your rule."

"Well, name the direction."

"It should be into a territory where the people hate their present rulers," said Machiavelli, "and would be glad to turn to you. It should be a place where the least effort would have to be made. Above all, the present ruler should be induced to make the first hostile steps. If you make any further unprovoked attacks all of Italy will be up in arms against you."

"Think of Urbino," said Cesare Borgia. "It is vastly rich, furnished with a great stronghold on an impregnable rock, and the people hate their present duke with all their hearts."

"Urbino is impossible," answered Machiavelli. "The great stronghold you speak of is too strong to be stormed. And while the people hate their duke, they would be afraid to rise against him unless they were furnished with a good leader. Besides, Guidobaldo da Montefeltro is a coward and never would give you provocation to make war."

"All good reasons, but they could be undone by better ones. Duke Guidobaldo has a weakness for women, particularly for rich ones. Suppose that I make a rich woman fall into his hands."

"She would have to be both rich and desperate if she wasted herself on that spendthrift of a Montefeltro," said Machiavelli.

"REMEMBER Caterina Sforza," said the Borgia.

"Ah?" said the Florentine. "You have deprived her of Forli, here. You have turned her out of her inheritance. She is a prisoner in your hands, and your wise course is to send her to Rome."

"I have deprived her of Forli, but still she is rich in jewels and in other lands. I should send her to Rome, and in fact it will be on the way to Rome that my envoy in charge of her will stop at Urbino to pay my respects to Guidobaldo."

"You never will find an envoy foolhardy enough to enter Urbino, knowing how the duke hates you," declared Machiavelli.

"But suppose that I can do it. Suppose that I can find the right man. What happens after the Countess Sforza finds herself inside the walls of Urbino?"

"Then," said Machiavelli, "she will use all her beauty, all her persuasion, all her wealth of promises to make Guidobaldo snatch her out of the hands of your envoy, and set her free."

"Naturally," said the Borgia, "and the moment that happens, you see that I shall have a good pretext for war?"

"It all would follow, perhaps," said Machiavelli, and that would be guessed by any man. The envoy who guides the countess into Urbino knows instantly that his throat will be cut and the countess snatched from his hands within twenty-four hours."

"I tell you, however, that I know of such a man."

"A fool?"

"Very far from a fool. You know him yourself. A fellow who is all aflame, without fear, never still, and who fills his days with so much action that he'll hardly take time to sleep in between for fear of missing another adventure."

"This man you speak of—has he red hair?" asked the Florentine

"Of course! It's Tizzo, the firebrand, the key that unlocked Forli for us, the wedge that burst into the citadel of the Rocca. Tizzo is the man."

"He may have the courage to do it, if you dare him to it," said the Florentine, "but he's not stupid enough to venture his neck in such a way."

"I shall give him a reason," said the Borgia. "Now that I think of the thing, I'm determined on it. Bonfadini, instantly send orders to the countess to prepare to travel; despatch a relay of riders toward Perugia together with a very secret message to Giovanpaolo Baglione to gather his force at once and let them drift a little toward the boundary of Urbino. Do these things, but first of all fetch me Tizzo, instantly."

BONFADINI left the room and went into the waiting chamber

where a few halberdiers were waiting in the half-armor of the

foot soldiery. Also, there were half a dozen men-at-arms

completely protected in heavy steel plate. Bonfadini clapped his

hands to draw attention.

He said: "Half a dozen of you go out to find Tizzo."

"Half a dozen are not enough," said one of the men-at- arms.

"There are not so many quarters of the town; and Tizzo is known to everyone," said Bonfadini.

"Not when he pulls a black wig over the red of his hair," said the soldier, "and he does that, usually. Who can tell where to look for him? He may be with a hawking party outside of Forli, or he may be following the greyhounds, or simply riding his white horse through the hills, or inside the walls he may be flirting with a girl, or at the studio of one of the painters, or watching that new sculptor at work, or teaching his company of peasant soldiers how to fence and shoot, or in a blacksmith shop learning the tricks of the trade, or drinking with a traveler in a wineshop, or learning a dance from one of the Gascons, or picking a fight with some huge Switzer. Or he may be running a race, or throwing dice, or sitting beside that scholar from Pisa reading out the Greek as gravely as any old man."

"If you know that he does all these things," said Bonfadini, "you ought to be the man to find him. But if I were you, I'd go toward the place where there's the most noise. Off with you, and have him here quickly, or you'll hear of it."

They hurried out, and Bonfadini went at once to the rooms where Caterina Sforza was kept under guard. He found her seated with a grim face at a casement overlooking the town that once had belonged to her. When she saw Bonfadini she exclaimed in her strong, resonant voice: "Tell your master to send a different messenger to me. The look of your white face is like a poison to me."

"Madame," said Bonfadini, "I came by command. The duke asks that you prepare yourself to travel at once."

"Where?" said she.

"To Rome, madame."

"With what escort?"

"Tizzo of Melrose," said Bonfadini, and smiled.

"With him?" she cried. "Go under the escort of the very man who stole my city and gave it to the Borgia? It would stifle me. I would die of rage before I had ridden a mile."

"Madame," said the poisoner, "I hope that you'll die of something more than anger."

And he bowed, himself from the room while she remained standing by her chair, having sprung up in a passion that flushed her handsome face.

ARMED men and their horses were gathered in the court; a

mule litter and two horses were prepared for the countess and her

maid; an hour or more had gone by and still there was no word of

Tizzo. At last a messenger came with word. He was a halberdier

with a pair of big dents in his helmet, a scared look in his

eyes, and a heavy limp in one leg. Bonfadini brought him straight

in to the duke and Machiavelli.

"If you saw Tizzo of Melrose, why didn't you bring him with you?" asked the duke.

"Highness," said the soldier, "when I saw him, he was fighting a huge Swiss who handled a five-foot sword as though it were a lath and a man stood with six ducats rattling in his hands; Tizzo had given the money as a wager that he could beat the swordsman and use nothing but a plain stick of wood in the fight. Highness, I thought it was murder and I ran in to stop the fight. Every moment I was sure that a sweep of that sword would murder Captain Tizzo and cut him in two the way a child cuts down a flower. But when I tried to interfere, the Swiss roared out that they would see the battle to a finish; they beat me down and rushed me away. I came back to tell what I have seen, my lord; when you see Captain Tizzo again, he'll be a dead man."

The duke pressed the coolness of the wet cloth closer across his eyes.

"What do you say, Niccolò?" he asked. "Is Tizzo a dead man now?"

"A stick against the sweep of a Swiss sword in the hands of a picked man—"

"Why a picked man?" asked the duke.

"Because Tizzo would only fight against the best."

"Well, that's true," agreed the Borgia. "The devil that's in him will only show its teeth at giants... I suppose that we'll have to find another officer to ride with the countess."

But at this moment a knock at the door caused Bonfadini to open it a crack, and then fling it wide, letting in a small uproar from the waiting room. And over the threshold stepped Tizzo, looking as lithe and sleek as a greyhound. He twirled in his hand a slender stick less than a yard in length, and rested a hand on this as he bowed to the Borgia.

"I hear that I'm called for."

The Borgia pulled the cloth from his face and suddenly stood, a lofty, massive figure, with a weight in the shoulders that made it possible to believe that he had decapitated a fighting bull with a single sword-stroke.

"I've searched the town for you, Tizzo," said the Borgia. "Where have you been?"

"I was wandering about enjoying the sights of the town," said Tizzo.

"Was one of the sights a butcher-shop?" asked the duke. "There's blood on that stick!"

"Ah, is there?" murmured Tizzo. He lifted the stick and examined it. "Why, so there is. Six ducats' worth of blood, in fact."

"If you had lost the wager, you would not be here alive, man."

"Ah, you've heard about it? The fact is that the Switzer kept me leaping about like a dancer. At last he made sure that he had me and swung himself off balance; so I managed to step in and flick him between the eyes with the tip of my stick. Afterwards I had to leave him the ducats to heal the wound."

"How long do you expect to live?" asked the duke, curiously.

"As long as there's a good dash of excitement in the air," said Tizzo.

"Let us be alone," said the Borgia. "Except for you, Niccolò."

The room, accordingly, was cleared at once.

"IT means mischief, Niccolò," Tizzo was saying to the

Florentine. "It means mischief when you're here."

The eyes of Machiavelli narrowed a little and gave him for the moment a look more like a cat than usual.

"Why does it mean mischief?"" he asked.

"When two cats are together and both of 'em hungry," said Tizzo, "it usually means that there's an unlucky mouse somewhere at hand for dinner. Am I to be the meat for you both, my lord?"

He addressed the last words to the duke; and his air, half laughing and half indifferent, took the sting out of the frankness of his talk.

"Shall I tell you the truth, Tizzo?" asked the duke.

"No, my lord," said Tizzo, "the truth from so great a man would be more than I could stomach. Tell me only what you wish me to believe and I'll swallow as much of it as I can at one good, long draught."

The Borgia merely laughed.

"Tizzo, you're honest. And I have honest work to do. That's why I've sent for you."

"Honest work?" said Tizzo, lifting his eyebrows a little.

"I want the Countess Sforza-Riario taken to Rome."

"I'd be glad to ride anywhere with Caterina," said Tizzo.

"Do you call her by her name?" asked Machiavelli

"She hates me so well that we've become intimates," said Tizzo.

The Florentine and the Borgia looked at one another and laughed a little.

"And on the way to Rome with the beautiful countess," said Borgia, "you will take the first step towards making peace between me and Guidobaldo da Montefeltro.

"You'll carry a letter from me to Urbino—and there—"

"Ah!" said Tizzo. "It's tomorrow that I'm to be eaten, and not today. Go to Urbino—did you say go into Urbino?"

"I understand you perfectly," answered the Borgia. "You're afraid that the old enmity between Guidobaldo and me might make it a dangerous trip?"

"Afraid?" murmured Tizzo, thoughtfully, as though he did not like tile taste of the word in his mouth. Then he broke out: "My lord, there's some damned dark bit of policy behind all this, I suppose. But I won't try to fathom it. I've sworn to serve you with mind and hand and heart for three months... Give me the countess and I'll take her as far toward Rome as God will let me... Give me the letter and I'll put it in the hands of Guidobaldo if I fall dead the next moment... I'll go now to prepare for the ride, and come back for your final orders."

He was gone from the room in another moment, as the duke waved his assent

CESARE BORGIA went to the casement and leaned there,

looking with troubled eyes over the roofs of the town.

"A sword against a walking stick—a five-foot Swiss two- handed man-slayer, against a little trick of a cane," murmured Machiavelli.

"Tell me how this Tizzo has managed to live so long. He'll certainly die tomorrow."

The Borgia said nothing in answer to this comment, and Machiavelli began to look at him, studying him with a curious attention.

"You're troubled, my lord," he said at last.

"I am, Niccolò," said the duke. "I'm troubled."

"But everything goes according to your plan."

"Did you notice how he spoke?"

"With a fine, free swing to his words, my lord. A fellow like that would sooner use his sword than his brain."

"Do you think so? He has a quick wit, though. But there was something about his way of talking—something from the heart—a certain noble carelessness, Niccolò."

"Ah, is that what you are thinking of?"

"Yes—a certain air with which he spoke."

"Then perhaps I know what troubles my lord."

"Tell me, Niccolò."

"Is it shame, my lord?"

"Ah? Shame?" said the Borgia. "I wonder!"

FROM Lady Beatrice Baglione to her brother, Giovanpaolo, lord of Perugia.

Dear Giovanpaolo:

Tizzo is away again like a wild hawk—or like a wild duck that some hawk will plume and eat presently. The Borgia has sent him with a handful of men to Urbino with a letter to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, the duke, and with Caterina Sforza. What is in the Borgia brain? I am sick and dizzy. I begged Tizzo on my knees to reconsider, but he has bound himself to be a slave to the Borgia for some months—eternities they will prove and end with his wretched death.

You cannot know what it means to me to be in love with such a wild-headed fellow. I try to tear the thought of him out of my heart. But the memory of his red hair burns in my mind. And all that he has done for you, for me, for our house. He should be kept under lock and key and only allowed liberty when there is some great danger threatening. There is too much English blood in him to permit him to fathom or suspect the depths of the cunning people of our race.

Before you get this he will be in Urbino. Perhaps he will be dead and Caterina Sforza will be in the hands of the Duke of Urbino. What can you do to help him? Try to think. I know you will because you love him almost as much as I do. I have only one comfort. His father, Baron Melrose, has ridden with him.

And you know as I know that the two of them are a double-edged sword that cuts faster in all directions than sneaking traitors and murderers ever can suspect.

My sleep has gone from me. My heart is breaking. I wish to God that I were a man so that I could stay at the side of Tizzo wherever he rides.

Farewell. Beatrice.

Letter from Cesare, Duke of Valentinois and Romagna, to

Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino.

My dear Lord and Brother:

I send this to you by the hand of Tizzo of Melrose, one of my most distinguished captains whose reputation will have come to your ears long before this. He is escorting on the way to Rome the Countess Sforza-Riario, whom you will be glad to receive and shelter for the night for my sake and her own.

I have asked Tizzo to open my heart to you. The purpose of his speech will be my heartfelt intent to enter into a lasting alliance with you. If I could join myself to your known greatness of mind and position, where would there be a limit to our ambitions?

Consider what I have suggested and which he will repeat more at large. There are many things that we could do together. These are times of stir and change.

My confidence in you I need not express. The coming of Tizzo and of the countess are eloquent of it.

Let me hear happy news from you soon.

Your affectionate friend, Cesare.

This letter the duke of Urbino read once and again,

moving a candle closer so that he could be sure of some of the

words. In the meantime he rubbed his nose, which, like that of

his distinguished ancestor, Federigo, was so big that it seemed

like the single handle of a cup.

He looked up and across the room, toward the chair in which the Countess Sforza-Riario was sitting. It was a famous chair of carved wood having as one support a horned stag and as the other an angry dragon with lifted wings. The countess lost so many years, by this dim light, that to her beauty was added the perfume of youth. The duke shaded his eyes and looked at her again, but the illusion persisted. He began to smile a little.

"This Tizzo," he said, "is a man high in the confidence of Cesare Borgia?"

"Yes," she said.

"And a friend to you?"

"So much a friend," she answered, that he cut the Rocca of Forli out of my hand and gave it to the Borgia!"

"Ah!" said Guidobaldo, and fell into thought again, stroking that long, hooked nose.

He was not conscious of his ugliness. His position was so great that he did not have to think of his face.

Then he read the letter aloud. As he finished, he asked: "Did you know what was written here?"

"No," said the countess.

"Does it bring any thought into your mind?"

"One thought," she said.

"What is it?"

"That Cesare Borgia has gone mad. If he lets me come into your hands, what prevents you from making an agreement with me by which you receive my claim to Forli and all the territory around it?

"And by the same agreement I receive my freedom—and certain funds in ready cash, perhaps, or some pleasant, small estate m Urbino?"

"Yes," said the duke. "It would be a simple matter for us to come to this agreement... Tell me: Do you fear this Tizzo will have you put out of the way long before Rome is reached?"

"No," she answered. "He is a man for battle, desperate chances, and be loves danger more than he ever can love a woman...

"There is beautiful Beatrice Baglione, and yet he cannot find time between his wild undertakings to marry her... He is not an agent for murder, my lord."

"He is a man of great value to Cesare Borgia," murmured the duke, "and yet he, together with you, has been placed in my hands, and his father along with him. Has the Borgia lost his wits, or has he some deep scheme in view?"

"He is always deep, but what scheme can he have in mind now?" she asked.

"War?"

"You have the strongest castle in Italy. If he had an army of birds he still would hardly be able to scale your walls."

"True," murmured the duke. "Very true!... But I wish that I could look into that mind of his."

He began to walk the floor, pausing at last behind the chair of Caterina and leaning on it.

"You and I could come to an understanding, my dear, could we not?" asked the duke.

For answer, she reached up her hand, quietly, and took soft hold on one of his.

FROM the casement of the room in which Tizzo was quartered with his father, the eyes skipped briefly over the crowded, tiled roofs of the town of Urbino and danced away over a ragged sea of mountains.

Tizzo's eyes skipped away in that fashion, watched the last green and gold of the sunset die out, and then he turned his glance down toward the town. The lights were beginning to shine along the streets.

"A town like this," he said, "who could take it with all the armies in the world?"

"All the armies in the world never could take it if it were honestly garrisoned," said the baron. "But where can you find an honest garrison in Italy?"

Tizzo leaned far out until he was flat on his stomach, peering down the steep of the great wall beneath. It seemed an incredible work, this heap on heap of masonry, like the work of an army continued through centuries. Somewhere in the dark tangle of the streets below he could hear a man's voice that was singing, lustily, a rare old song of the countryside

"Her hand is gone from the loom,

Her step no longer hurries toward me,

Her voice no more sings from the pasture,

She has left me the empty night."

Tizzo waited, but when the next verse did not follow, he

trolled it out with a ringing voice:

"Search for her not so far as heaven;

Look up, but not to the stars;

The castle of my lord held many treasures;

Then why did he steal my happiness?"

From the street below a voice began to shout; Tizzo,

laughing, turned back into the room and began to tease a green

and golden parrot which was climbing head down around the wire

walls of its cage.

"How can you tell, Tizzo?" asked the baron. "It may be that it is treason to sing that song in the castle of Urbino."

"If a song can be treason, I'm glad to die for it," said Tizzo, and from a silver bowl of fruit he began to pick out the little white, dry, sugar-covered figs and eat them, together with morsels of bread which he broke from a loaf, cramming his mouth too full for talk.

His father watched him and smiled at him.

"I'll tell you one thing," he said. "A man can sing himself into more trouble than he can talk his way out of afterwards. When I was serving under Piccinino, there was a big Milanese who had a throat like a bull and a voice that could fill it, and one day he sang a serenade that had the name of Giulia in it. Well, it happened that Piccinino was fond of a girl with that name, and when he heard the song he didn't stop to ask questions. He sent down a pair of his men and they slipped a dagger under the fifth rib of the singer before he had finished emptying the song from his throat. When you're around these great people, it's best to speak in a small voice and not sing at all."

"Well," said Tizzo, "I need room for my elbows and a chance to make a noise, now and then. Room—room to swing an ax, say, or a sword—"

HE washed down the bread and figs with a mouthful of red

wine, and picked up that blue-headed steel ax which was dearer to

him than all his possessions except Falcone, his white horse.

Swinging the ax, he did an improvised dance about the room,

striking swift blows to right and left, and making the edge of

the ax whistle just past carved and gilded furniture, and then

all around the head of a little marble faun that occupied a niche

in the wall.

The baron began to laugh with pleasure, and here there was a knock at the door. When the baron called out, the door was pushed open by one page who allowed a second lad, all brilliant in sleek velvet, to enter carrying a beautiful silver charger that had on it a pair of goblets.

Rosy crystal composed the bowls of the cups, which were held in a net of gold and supported on pedestals of silver.

"His highness sends his compliments and his good wishes for an excellent night's sleep to my lord and to Captain Tizzo," said the page, and straightaway presented the cups to the two guests. After that, he backed out of the room and closed the door after him with a reverent softness.

The baron lifted the cover of his goblet, and sniffed.

"Good spiced wine," he said. "This Guidobaldo has good manners even if he is a duke with a castle built in the middle of the sky. To your health, Tizzo!"

"Wait!" said Tizzo, who was inhaling the bouquet of the wine. "This is probably the best wine and the safest in the world—but I have been living in the shadow of Cesare Borgia, remember, and I've been learning some new ways in the world. The parrot can be our tester."

He dipped a bit of bread in his wine and carried it to the cage. The parrot rolled his eyes, put out his head, twisted it to the side, and nipped the bread neatly out of the fingers of Tizzo.

"You see?" said the baron. "There's nothing wrong. A parrot's too wise a bird to eat poison. It shows that you've been too long in the wrong company, Tizzo. How much longer do you have to serve the Borgia?"

"I'm sworn to him for another ten weeks," said Tizzo.

"I'd feel safer if you were serving any other man in the world for ten years," said the baron. "I drink to you, Tizzo!"

He was lifting the cup to his lips when they both heard a soft fall, and they saw that the parrot had fallen to the bottom of his cage, where he was stretching his wings and kicking out with his feet, and ruffing out the brilliant feathers about his neck. In a moment he was still. The wings remained half-spread, and the feathers if the ruff slowly collapsed.

The baron rubbed his lips dry.

"Tizzo," he exclaimed, "did you taste the damnable stuff?"

"Not a drop," said Tizzo, putting the cup slowly back on the table beside him. A quick, powerful shudder ran through him.

The two stared with blank eyes at one another.

"Why?" asked the baron.

"Either for hate or for gain," said Tizzo. "And my lady the countess hates me since Forli. Perhaps—why, perhaps the gain would be in having me out of the way, and you out of the way, also, if the duke intends to keep the countess here in the castle instead of sending her on to Rome."

HE ran to the door with silent-falling feet and leaned

there, to listen.

Turning, he whispered as he tiptoed across the floor: "There are armed men waiting outside the door. I heard a sword stir in a sheath."

"Lock the door," said the baron, "They'll wait for a moment for us to drop dead, and then they will come in to look at the bodies and cart them away."

"If I turn the lock, they'll hear the bolt sliding and then they will know that something has gone wrong with the plan."

Tizzo reached for a jacket of mail. But his father raised a hand to stop him.

Hurrying to the casement, Melrose leaned out far and glanced down the face of the wall. The drop of it was sheer to the street, far below; even the first roof was a terrible fall beneath them. And for the first fifty feet there was no embrasure of any kind to break the smooth surface of the wall. To the left, perhaps two stories below and twenty feet away, there was a projecting roof-line.

"Take the sheets from the bed," directed Melrose. "So—"

He tore away the covers and with the edge of his dagger began to slash the sheets into long, thin strips. The edge of the knife was so razor-keen that the cloth divided almost without a sound.

"If they mean murder," said the baron, "at least we'll make them take a long step to catch us. The Borgia—the Borgia, Tizzo—was it part of his policy to send you into a murder trap?"

Tizzo, asking no questions, was imitating his father implicitly. When the sheets were cut, they began to twist the sections so as to make strong rope, and then the ends were tied together.

And Tizzo was saying: "If Cesare Borgia loves a friend, he never will betray him. But he loves few friends. I am merely a new acquaintance. I have a value to him, but he would give me up in a moment if he dreamed that he could get a handsome return for my life."

"Do you ever think of putting a knife into the hollow of his throat and so ending your bargain with him?" asked the baron.

"Between you and me," said Tizzo, "I rather like him. There is a devil in him, but that devil may do a great work for Italy. Sing, father. We'll need a little noise... And let them think that we're enjoying the first effect of the wine, before we have a second taste, of death."

As they talked, quietly, calmly, their hands moved rapidly, and a long rope of the white, twisted sheets was now prepared.

Tizzo ran to the window with it.

"The roof there on the left. Can you swing yourself onto it?" murmured the baron. And he began to sing one of the old marching songs.

TIZZO, having estimated the distance from the casement to

the roof with a careful glance, measured out a length of the

white rope and tied the rest of the rope around a couch which he

dragged with the baron's help beneath the casement.

"You first!" he murmured to the baron.

But the older man, with a frown and a headshake, pointed toward the door and then toward his own throat as though to indicate that his voice, which had begun the song, must be permitted to continue it. And Tizzo peered up into the older face for a long half-second, realizing perfectly the calm abnegation which underlay his gesture. But there was no time for argument. He was instantly through the window and slithered down to the end of the rope.

Running with his feet along the wall, he started the pendulous swing of the rope. When it had once begun, with the swing of his lithe body he made the rope sway out in wider and in wider arcs. Above him, dimly, he could hear his father's voice still singing the "Song of the Plough." The wall rushed back and forth beside him with greater and with greater speed.

Now his head rose so that he could look into a window that broke the surface of that projecting wall whose roof was his goal. A girl was inside it—a servant, perhaps, ogling herself in a hand mirror while she turned her head from side to side, and lifted or bent it in order to view herself from the most favorable angle. She was an ugly wench and the task was hard, but she kept at it with wonderful patience and seemed to enjoy the work.

The next swing of the rope brought him to the level of the roof, almost, but he saw that he was much too low on the rope, since it was bringing him in under the projecting eaves. He hauled himself up several arm-lengths and on the next return of the rope, with one hand he was able to reach out and grip the roof-gutter under the tiles.

His weight recoiled with a violent wrench that almost broke his grasp on the gutter; a moment later he was on the roof.

His father, older and heavier, never could succeed in that athletic effort, he was sure But the baron would be able to hand himself down the slant of the rope and so come to the roof. Yonder was a trap door set into the slant of the tiles. To one of the projecting beam-ends inside of which the door was set, Tizzo made the linen rope fast. Then he turned and waved.

At the dimly lighted casement he saw the head and shoulders of his father. A strong strain was put on the rope and set it trembling. A moment later the body of the baron dropped over the casement's edge and he began to swing himself along the downslant with long arm-hauls.

He came out of the lamplight into dimness, then closer and closer, until even by starlight Tizzo could see his face and the knotted effort in it.

Here a great shout struck across the night. At the casement to which the rope pointed like a long finger appeared a leaning figure; steel flashed bright; the rope was cut across.

THE baron dropped instantly on the loose rope. Tizzo heard and felt in his own flesh the shock of tile impact as that heavy body struck the wall beneath the eaves.

Was he gone? No, the weight still strained down on the rope. Tizzo, groaning with hope and fear, reached back and fingered the haft of the ax which he had hung by its noose from about his neck.

Now a woman's voice began to screech just below. It was the servant girl, no doubt, who had been called to her window by the noise to see a dark figure struggling in the empty air above her casement.

Would the baron drop down and try to enter that window, or would he climb?

The answer was in the appearance of a hand that gripped the edge of the eaves. Another hand joined it. The big man heaved himself up with power, grunting. Tizzo caught the collar of his jacket and pulled with all his might to lighten the work.

Yonder at the lighted casement, two figures remained, yelling out the alarm. Other shadowy heads appeared at other windows. There was a dim but distinct sound of running feet along corridors.

"Are you hurt?" breathed Tizzo.

The baron stood up and pulled out the sheathed sword which he had stuffed inside his clothes.

"It was a bit of a slap—but it was nothing," he said. "Here, Tizzo. Do we run along the roof, or do we go down into the wolf-den?"

"Down into the den," said Tizzo. "They'll have twenty men on the roofs before a minute has gone. Here's the way!"

He found the lock of the trapdoor, smashed it with a blow of the ax-head, and lifted the door open. Beneath him he saw darkness which seemed to be churning like dusky water. But with hand and foot he found the ladder.

Down he went into the pitchy blackness with the weight of his father making the ladder creak as the baron followed after. The floor was quickly reached.

Rough boarding was underfoot. He reached a wall of unfinished stone and fumbled along it.

The tumult was redoubling through the castle. The pounding sound with the metal clash that accompanied was made by the armored feet of soldiers, of course. But the most terrible noise was the dreadful screeching of the women.

To his left, he was aware, now, of a silver rectangle drawn on the wall, etched in with broken strokes. That must be the leakage of light round the edges of a door. And now, in fact, his hand was on the knob.

The lock had not been turned. He pushed the door open and looked out onto a long, narrow corridor.

AS he stepped out into the hallway, a whole bevy of the

female servants not five paces from him threw up their arms and

fled, screeching with terror.

They were crying for help, they were shouting that the two were there—there in the hall—murdering the women.

And the answering shouts of men came in quick response, from close at hand.

"Which way?" muttered the baron.

"The first way!" said Tizzo, and running round the first elbow turn of the hall, he leaped across a faintly lighted threshold the larger size of whose doorway seemed to indicate that it might be the entrance to another corridor.

And as he entered with his father behind him, he heard the armored uproar of the men-at-arms come pouring into the hallway which he had just left.

But it was not another hall. It was a narrow little room with a table across one end of it. On the table were piled old clothes and near it sat a crone bent over her work of patching with much care a pair of hose, frayed about the knees.

She did not look up, but pursed her lips tighter as she made the next stitch. Tizzo and the baron backed into the thick shadows of the corner and waited. The sword was unsheathed in the baron's hand, now. And Tizzo's ax was ready. It was the last fight, perhaps, but at least they could make it together.

"Deaf!" whispered the baron at Tizzo's ear. "She's deaf!"

The noise of the manhunt thundered in the hall. Two steel-clad figures lurched a step into the room, saw the seamstress, and recoiled again.

A false alarm drew the flood of searchers off to the left. To the right there were the babbling, squealing women, their voices growing dimmer as they retreated.

"Now?" asked Tizzo.

"Hush!" said his father.

The flight of figures down the hall seemed to have caught the eye of the old woman at last.

And as the thunder of the mailed feet surged back again, she left her chair and went to the threshold of the room, standing there with her hands on her hips, shaking her white old head at the mad confusion.

There seemed to be no fear in her.

A crowd of soldiery poured past her. Half a dozen times she was hailed: "Have you seen them?"

But she answered with the continued wagging of her head.

The manhunt left that portion of the palace and ebbed down to a lower level. Through the casement, Tizzo could hear more sounds of war rising from a court or open street. Voices were shouting commands.

And as the tumult grew less, the seamstress returned to her chair again.

SOME brazen-throated fellow was bawling out beneath the

window: "Five hundred ducats—for the Englishman, Melrose!

Five hundred ducats for him and his son! A hundred for the baron;

a hundred ducats for the baron! Four hundred for the red head of

Captain Tizzo! Money and the duke's favor! Money and the duke's

favor! Five hundred ducats!"

It was like the crowing of a rooster, a sound that cut through the increasing tumult. It was as though an auctioneer were asking for bids.

"Dead or alive, five hundred ducats! Five hundred ducats!"

The old woman went to the casement and seemed to be listening to that proclamation, but since she was deaf, no doubt she merely was watching the dimly lighted figures in the street or the court below.

She turned from the window and faced straight towards the corner in which the two fugitives remained, pressed close together. Did her old eyes pierce the shadows? Could she indeed see them?

"Five hundred ducats is a world of money," she said.

Tizzo shuddered.

After all, she had good ears. How had she failed, then, to hear them when they first bounded into the room?

"Four hundred ducats for a red-headed lad!"

She went to the door, and shut and locked it.

"Well," she said, turning, "I think I shooed the hawks away from a pair of helpless chickens that time. Come out here and let an old woman bless her eyes with the sight of two men saved from the grave."

They moved slowly forward, neither of them glancing at the other. The brain of Tizzo had stopped.

"Mother," he said, "except for you, our blood and brains would be smeared on the floor long ago."

"I hate a screaming fool of a girl," said the crone, "and so I learned to hold my tongue when I was a youngster... Five hundred ducats!... A great deal of money... a great purse of money... a farm, and a peaceful life."

"You shall have it, friend," said the baron, "if you can show us the way out of the palace—any secret stairs—any back, unregarded way—do you see this gold chain? A thousand, ducats would never buy it. And you shall have it. Here it is in your hand, now."

She took the chain and weighed it, grinning.

"Suppose that I took it," she said. "For every bead of it how many times do you think they'd make me scream on the rack?"

SHE gave back the chain into the big hand of the baron and

shook her head.

"Besides, what would I do with a farm and quiet?" she asked. "I've had the city and the palace all the days of my life. I've had the processions, and the smell of incense in the churches, and the music, and the pretty girls, and the slim lads, and the babies in silk and the old men in brocades, and the marriages and the murders, and the civil wars, and the stabbings in the dark, and the night-cries where some poor devil found his end in a dark alley... how could I change all of this for a farm, and the smell of the wet ground or the dust instead of the perfumes and the stenches of the palace? No, no—I don't need five hundred ducats to end my days on. A prayer would be a greater help to me, my friend."

"You shall have our prayers, mother," said Tizzo.

She looked at him with a smile that made her withered old face more horrible than ever.

"The first lover I had in all my life, he had a head of red hair, like yours. When I saw the flash of that flaming head of yours, I thought for a moment that it was a ghost coming out of the past to me, and that I was a pretty young thing again; and the thought took the breath out of me and made me miss a stitch. That poor Adolfo—he was a beautiful lad, except that he talked all one side of his mouth. But he stole one of my lady's rings, and they cut his soft throat for him. That was a day I cried my eyes red! And my heart ached for a week. Ah well, I never see red hair that my heart doesn't jump up stairs like a wild ragamuffin. What shall I do with the pair of you?"

The noise of the search that had sunk away now boiled up higher inside the walls of the castle and flowed suddenly once more down the corridor beside them. And here a hand tried the door, then beat against it.

"Open!" called a voice.

"Ah?" murmured the woman. "Five hundred ducats?"

She weighed the key in her hands, and in her eye she weighed the lives of the two. Then she opened the door.

TIZZO, drawing his father by the arm, drew him down behind the table which was heaped high with clothes that needed repair. They were not perfectly concealed from the man who stood in the doorway, now. Tizzo, from beneath the table, could see the armored legs of the man as high as the hips. They made him think of the legs of a great beetle, such as those he had watched crawling when he was a lad—sleek, glossy metal, He used to turn those beetles over and then watch them flopping helplessly on their backs, kicking their legs. He had an insane desire to try to steal out and trip up this splendid soldier.

And yet, behind the man and up and down the hallway, moved an armed number of other fighting men.

"Ah, mother," said the man-at-arms, "what are you doing up so late?"

"Mending your worn-out clothes," she answered.

"Have you seen a pair of men—one old, one young?"

"Certainly," she answered. "Look yonder, under the table."

Tizzo heard his father catch breath, and gripped his arm with a sudden pressure, to seek to restrain the sound.

The soldier broke into laughter.

"What's your name?"

"Agnes."

"Agnes, I don't suppose that the two we're hunting are here in the room with you. But I wondered—"

"Why don't you suppose so?" asked Agnes.

"Because they'd twist your old windpipe before they'd let you open the door. But I thought—"

"Not if they were real men. Real men don't murder old women," said the hag.

"Agnes, I wanted to know if you'd seen any glimpse of them. That's all."

"Certainly. I saw them come into my room and stand in the corner. When I went to the window, they sneaked under the table."

The soldier laughed again.

"You're an old one, and all the old ones are hard," he said. "Well, God be good to you."

"God give you better sense to understand women," said Agnes.

He laughed again, and walked from the room. Agnes closed the door after him, and locked it again.

And down the stairs at the end of the corridor, Tizzo heard the noise of the manhunt passing, dwindling, descending. He stood up with the baron beside him.

"Well, you see what truth is worth in Urbino," said the hag, grinning at them.

She had only one tooth in the middle of her mouth, and. when she grinned it showed as yellow as old ivory, and her eyes disappeared in nests of wrinkles.

"YOU could have pointed, instead of speaking," said the

baron. "A motion of your hand would have started him, like a

hunting dog. And he would have found us. You would have had your

share in the ducats."

"I'd hate to show a man to a hunting dog," said Agnes. "But if I had, there would have been a pretty thing to see. Would that sword of yours have found a way through his armor? Would that ax of Captain Tizzo have cut through his helmet? Yes, I think it would. Red-headed men are better than all the rest. I remember when a red-headed man fought for me in the street, yonder. I was not what I am now. I had feet under me as quick as a cat. And I was as sleek as a fish, all over. Hand or eye could not touch me without pleasure. But now what am I to do with you?"

"You've given us a chance to draw breath and turned the hunt another way," said the baron. "We'll find our own way out, now."

"You talk like a fool," said Agnes. "Do you think that every inch of the castle won't be hunted over again, now? You don't know the noble duke. There's a patient man for you. There's a fellow who'll wait longer than a fisherman or a cat at a rat- hole... Well, let me think a little."

She propped her chin on one hand and frowned. The frown swallowed her eyes in black shadows. At last she said: "Old clothes. I've nothing to work with but old clothes."

In fact, on shelves at either end of the room appeared big bundles.

"Those are for the hospitals. But why shouldn't they be carried to the hospital now?" muttered Agnes. "Listen to me, Captain Tizzo—are you the man who rode through Perugia at the side of the Baglioni and cut through the chains of the streets with your ax?"

"That's true," said Tizzo. "There's a gift in this ax. It laughs at all other steel."

"Red-headed men laugh at everything," said Agnes. "But who would see Tizzo of Perugia in the form of a porter carrying bundles of old clothes on the top of his shoulders... Wait!... Now see yourself!"

She pulled out a ragged mantle, which she threw over the shoulders of Tizzo.

Upon his head she drew down an even more ragged hat that covered his face to the eyes.

"Now, now!" she exclaimed, inviting the attention of the baron, "would you know your son, my lord?"

"Never!" said Melrose, smiling. "And then?"

"Then I take you down the little winding stairs at the back of the palace. I let you out at the small door. There will be guards, of course, but there is my tongue, also, and two simple, honest poor men carrying old clothes."

She began to outfit the baron and then to throw down from the shelves bundle after bundle of the old clothes which had been cast off by members of the ducal household.

FROM beneath the window, the bawling voice of another

crier began to sound out: "Five hundred ducats for the English

baron and Captain Tizzo. Five hundred ducats, dead or alive!"

"Hai!" grunted Agnes. "Do they have to maunder on about ducats? I was tempted once by ducats and I'll never be tempted again. Five wretched years—five years—where did they fly to, Lord God? Five mortal years. They found me a girl and they left me a woman with age pointing my chin and misting my eyes... Oh, God, how quickly the pollen is shaken from the flower and the bloom wiped from the petal and the fragrance gone, gone, gone!

"Well, I've been young. That's all there is to it. I've been young. I had the lightest pair of heels in Urbino and the prettiest pair of legs and I didn't care who knew it... Lord, Lord, the withered old shanks that carry me around today... But if a girl wants a lover she should find a man with red hair... You'll make some lass happy, Captain Tizzo, for a week or two—before you smell flowers of a new sort behind some high garden wall... Walls are made to be climbed; women are made to be hunted... To run away and laugh over their shoulders. And only the swiftest foot shall catch 'em. Oh, I know about it! Are you ready?... Look at my heels and never higher. Walk slowly. Trust the talking to me..."

She opened the door and they followed her into the hall, each of them bending under a clumsy, great bulk of clothing that loomed vast above their shoulders.

They passed down the upper corridor, and then they went down a stairway that wound constantly. The stairs were so steep and so many that the knees of Tizzo grew a little weak.

They reached another hall beneath them, more filled with clamor of voices, tramplings, loud commands, and always the clashing footfall of armored men. The Urbino palace was buzzing like a hive, and there were no drones—every human was armed with a sting. Halberd, sword, boar-spear, dagger, club were all about the two inclining figures of the baron and his son.

"Who's that, and what's here, and who the devil are these?" demanded a loud voice.

And old Agnes shrilled back in her wavering voice, "And who are you and what is that and who gave you power to ask?... If I'm tumbled out of my bed at this hour to pile charity on the backs of two sinners from the hospital, who has the right to—"

"Ah, be still," said the soldier. "I'd rather talk to a barking dog than to you, old Agnes."

"Aye, but the young Agnes was for your betters. I've seen the time when the lifting of my finger would sweep ten better heads than yours off the shoulders that wore them."

"Damn you and your better men and your better times, you hag," said the soldier. "Get out of my sight!"

She led on down more stairs and came to a passage that ended at a door guarded on either side by a man-at-arms.

ONE of these stood up and lowered his halberd to a

striking position.

"Who's there?" he asked.

"Agnes," she replied.

"What's with you, Agnes?"

"A pair of weak-kneed beggars from the hospital," she answered.

"What are their names?"

"Beggars have no names."

"They can't pass at this time. Have you not heard the uproar? Captain Tizzo and the Englishman who arrived today are wanted for the hangman tonight."

"D'you mean that these two can't get out of the palace?"

"They cannot."

"Ah right," said Agnes. "If you care nothing for fleas—and for worse things—I'll turn this pair over to you."

"Turn them over to me? Damn the dirty rats, what would I do with them?"

"I don't care what you do with them," said Agnes. "They were sent to me to get the clothes for the hospital. I've given them the clothes. That's all I can do."

"I won't have 'em. Take them back to where you found them."

"And tell his highness that I was stopped at the door?"

"Well—I can't do this, and you know it very well."

"I know nothing about you; I don't want to know. Shall I leave these two with you and go back?"

"Wait a moment."

"Suppose it's Tizzo and his father. I half think that those are the right names," said Agnes.

The soldier chuckled.

"You have a sting in the end of your tongue," he said. "But now listen to me. Are you sure that the duke ordered these two to be allowed to carry away the old clothes for the hospital?"

"Yes," said Agnes, ''because he recruits from hospitals and old men as nigh as any."

"It may be true," decided the guard. "Well, shall we let them through?"

"Who are you, fellow?" asked the other guard. And he rapped Tizzo in the ribs with the butt of his halberd.

Tizzo grunted, half the breath driven from his body.

"God forgive your worship," he whined. "You've struck me on the place where the doctor cut me for stones, and I doubt you've opened the old wound. Oh, ah, I feel the heat of the blood running down my side—but God knows that I'll never cast blame on you. I'm one of the unfortunates of the world, and the quickest way out of it will be the greatest mercy for me."

The soldier broke in: "That's enough. That's the true hospital chatter, and I've heard it before. Get them out, and quickly. Otherwise, we'll be catching a thousand foul diseases from them. A sick man is worse than a sick dog. Did you hear the whine of him?"

The other man shrugged his shoulders, shoved the key into the lock, and pulled the door wide.

"Out with you! Out with you!" he commanded, and kicked the baron to help him more rapidly through the doorway.

"Farewell!" called Agnes after them. "Mind you that you get one of the beggars to say a prayer for Agnes. For any Agnes. There's not one in the world that needs praying for as much as I do!"

Then the door slammed with a metal jangling of the lock and key.

And Tizzo found himself in a narrow street that pitched sharply down the hill on one side and climbed steeply up it on the other.

"Which way, father?"

"Either way—I don't care which," muttered the Englishman. "A dog of a common soldier has put his foot to me. I'll have blood for it! By God, I'll have a river of blood!"

THEY climbed the hill, and took the first way to the right still bending under their loads. A pair of young cavaliers, galloping past scattered mud and water over them and laughed over their shoulders at the two weighted-down pedestrians.

A rabble of young drunkards streamed around a corner and suddenly beset them.

"Way for the Lazar House! Way for the hospital!" called Tizzo, in a dreary singsong.

The lads scattered with yells. If it were not actual disease to touch or speak with one from the hospital, it was bad luck of the worst sort, at the least.

And now they came out into a wider street and saw a cart with two men in half-armor riding behind it. To the tail of the cart was tied a man stripped to the waist, and after him strode a huge Negro who swung a whip and used it at every tenth step. And in the cart sat a fellow who bawled out:

"This is Luigi, the son of Elia the smith, for speaking ill of his glorious highness, the Duke of Urbino! This is Luigi, flogged through the streets of Urbino for a day and a night..."

A little crowd followed after the cart. They were curious, but they never came too near. They kept to either side of the street and not a sound, not a word came out of their throats. The only reason the flogging could be seen so well was that a lantern was carried high from the cart at the end of a projecting pole, and this showed the entire picture—the carter half asleep behind his two mules, the crier of the punishment, the criminal, the Negro, the two soldiers who jogged behind the rest to see that the course of the law was undisturbed.

Tizzo paused and stared at the unhappy man.

"On, on!" said his father, shouldering past him.

"Aye," said Tizzo, "and yet I could drink hot blood when I see such a thing—"

"Come, come!" exclaimed the baron. "We can't right all the wrongs in the world—"

"But for speaking evil of the damned Guidobaldo, the poisoner and traitor, the destroyer of good knights, the dog-faced Duke of Urbino!" gasped Tizzo.

He kept on staring at the procession, unable to start on again. The face of the prisoner must have been young, the day before. It was old, now. It was old, and long drawn. The eyes were buried in holes.

The cart lurched over a bump in the way, the sudden pull on the cord jerked the poor Luigi forward on his face and he dragged in the mud. His back could be seen more clearly, now. The lantern light streamed down over it and showed it painted with stripes of red, as with crimson paint, sticky and wet, and in the middle of the back the stripes all gathered together in one huge, solid red patch on which the blood was flowing.

The Negro, laughing, called out: "Look, my masters! I'll put more speed in his feet."

He whirled his whip and brought it down with a loud crack that made the blood fly; and Luigi was lifted to his feet by the agony. "Christ... mercy..." he gasped.

AND Tizzo heard him. He hurled the bundle from his back

and caught out of the rags he had been bearing the ax with the

head of good, blue steel. The edge of it gleamed like silver.

"A rescue! A rescue!" shouted Tizzo. "All good men behind me!"

The two halves of the following crowd halted. The cart driver, amazed, pulled at the heads of his mules and brought them to a stand. The two soldiers, bewildered, halted their horses also. The nearest of them, seeing a man spring in at him with an ax, leveled his spear and took a shrewd thrust at the breast of Tizzo.

He might as well have thrust at a dancing flame. The spear head went wide of the mark and Tizzo, leaping up, planted one foot on the stirrup of the soldier and brought down his ax.

If he had used the edge, the man never would have spoken again. But he used only the hammer-head at the back of the ax; the blow hurled the man-at-arms out of the saddle and senseless into the mud.

"Treason!" shouted the other soldier. "All true men—"

But the crowd stood in frozen silence as Tizzo ducked under the belly of the first horse and leaped at the other soldier. He had one help, now. The baron, tossing aside his bundles in turn, had snatched out his sword from the mass of cloth and was running in with the weapon raised.

That sight was too much for the man of war. He put spurs to his horse and went plunging away, still screeching: "Treason! Rebellion! The people are up!"

That sight was too much for the man of war. He put spurs to his horse and went plunging away, still screeching: "Treason! Rebellion! The people are up!"

And only then did the people who looked on suddenly give voice with such a sound as Tizzo never had heard before from men or from beasts, a low, groaning, mournful, growling noise; and the two halves of the crowd began to flow suddenly into the street.

"We're lost!" cried the baron. "To your heels, Tizzo!"

The Negro who carried the whip had turned and started to flee. One wing of the closing crowd met him. There was a scream, a sound of blows. It was the Negro who had yelled out.

But Tizzo, running forward, slashed the rope that tethered Luigi to the cart's tail. The carter, in the meantime, began to flog his mules; they broke into a gallop. And Tizzo found himself with one arm around the reeling body of Luigi, his other hand free to handle his ax.

His father came and stood beside him, the sword raised and ready at a balance for the first stroke.

"This is the end, Tizzo!" he exclaimed. "Poison from high hands would have been better than death from the mob. Guard my back truly as I'll guard yours, and still we'll make a fight of it."

"Wait!" exclaimed Tizzo. "I think that they mean no harm at all."

After the first growling noise, the crowd made no sound. But they came straight in. They were almost on Tizzo and his father before two or three of men muttered: "Friends! Friends! Put down your weapons. Every man here would die for you, brothers!"

"They mean it," muttered Tizzo over his shoulder. "Let them be!"

THE baron, undecided, nevertheless kept his sword raised

and did not strike until he saw the many reaching hands go out to

Luigi, take him up, lift him shoulder-high, and begin to bear him

away.

A tall old man, still strong and swift stepping, caught Tizzo and the baron by the arms.

"This is the first day of my life!" he said. "Now I am born. Now I have seen a common man lift hand against the duke's own officers. I thank God! I'm ready to die! Come with us, friends! There is no safety in Urbino for you, now, but you are safer with us than with any others!"

AND they went with the flow of the crowd, under the dim

starlight, hurried along blindly as though the run of a river had

picked them up and were carrying them along.

They entered alleys filled with a foul, sour savor. They twisted around dingy corners. And at last a door opened, and they poured into a dairy barn where the cows were tethered in rows, and a single dim lantern gave them a flickering light as unclean as the streets through which they had been passing.

Hay was piled in an empty manger and Luigi was laid on this bed, face down.

A young woman, big with child, haggard, came swiftly into the throng.

"His wife! The wife of Luigi!" said voices, and a way was made for her suddenly.

She climbed into the manger and took the head of her husband in her lap. And every now and then she would jerk up her head and look over the crowd with startled eyes, only to bow again, a moment later, and stare at the bleeding flesh of Luigi.

The old man who had taken the baron and Tizzo by the arms now officiated with an air of authority. At his direction warm water was brought.

With his own hands he washed the blood away, and then plastered over the back of Luigi a good layer of lard.

Said a voice near Tizzo: "There goes enough lard to give a savor to ten pounds of black bread."

And another answered: "Aye, but the bread he eats is pain! I won't grudge him the lard tonight!"

IT seemed to Tizzo that he had never seen such men before.

He had had to do with foresters, on the place of his foster

father, and here and there he had mingled briefly with the common

people. But now it seemed to him that he was beholding them for

the first time, and he was amazed.

They were in rags; they were dirty, ill-smelling; but now that he looked at them by the lantern-light, it seemed to him that he never had seen better brows, keener eyes, more resolute faces. Now and again his eye fell on some brutal face, but for the most part, in good clothes and with a bath between them and the past, they would have seemed as noble a lot as ever stood in a court.

And a great strange thought burst in upon Tizzo—that perhaps men, after all, are very much alike. The born prince might have his royalty by accident rather than merit. And the cobbler, the peasant, the household drudge, the serf, perhaps were all of them as kingly as any who sat on thrones, except that their feet had been forced into lower ways.

It was a thought that discomforted, Tizzo. He knew that it was great blasphemy, and he put it away from him as quickly as possible. For, of course, kingship comes from God and from God only, and common people are born to serve their superiors. Nevertheless, he was so troubled that he began to breathe a little faster. There was a giddy lightness in his breast. He found that his teeth were hard-set.

At his shoulder he heard the voice of his father saying: "We had better be out of this. This is no place for people of our bearing, Tizzo. Quickly, lad—and come with me."

Tizzo pulled off his cloak and stepped forward.

"Here, friend," he said to Luigi's wife, "wrap your husband in this."

Her hand caught at the cloak and then dropped it. Her eyes remained staring aghast. She pointed with a trembling hand.

"Look! Look!" she cried.

And a sudden snarl came out of the throats of the crowd,

"One of the gentry! A spy! A spy S... Let me come at him... Let me have my hands in his throat!"

SUCH hands as Tizzo never had felt before gripped him. He saw the cloak and hat torn off his father at the same moment. The baron, huge and weighty with trained muscle, struggled desperately. Knives gleamed.

And Tizzo shouted: "Father, we're helpless. Stand still and let the fools remember what we've done for Luigi!"

This sudden outcry stilled the fight for a moment. But the people had become animals, with burning eyes and flaring nostrils. They kept inching nearer and nearer to their prisoners. The tall old man who had been spreading the lard over Luigi's back began to exclaim: "What are you thinking of, friends? Do you forget that these are the men that knocked one soldier into the mud and made the other run? If you wanted fighting, why didn't you use your hands when poor Luigi was being flogged at the tail of the cart? What reason have spies for fighting the duke's own men?"

A hunchback, deformed but not crippled by the great bunch behind his shoulders, thrust his long head still farther forward. He had a pale face, slit with a vast mouth, that formed itself strangely around the words he spoke.

"What reason?" he said. "A very good reason. To seem to strike a blow for a friend of the people, and so be brought in among them and see them, and count the faces of the men who hate the duke."

"Aye, aye!" muttered the rest. "That's the point of it"

Those newly opened eyes of Tizzo scanned the others again. To be sure, these ragamuffins could not afford plate armor and fight on horseback against the gentlemen, but the arquebus was becoming cheaper, more manageable year by year. Suppose that the mob ever were disciplined and armed with such weapons—what would their millions do to the scant thousands of the gentry? The tremendous picture rolled darkly across the eyes of Tizzo. He shuddered a little.

The old man—a blessing on him!—was continuing the argument.

"What fools the pair of them would be to disguise themselves in nothing but old hats and cloaks? Do you think that they're half-wits my friends?"

"All the gentry are more than half fools," said the hunchback.

There was an instant muttering of assent.

And the hunch-backed man went on, "Now that we have a pair of spies, let's close their eyes and ears for them forever."

"Luigi," said the old fellow, "here are the two men who saved you from the tail of the cart. Turn your head and see them. Speak a word for them."

THE head of Luigi was turned by the hands of his wife, but

he looked with red-stained, senseless eyes at the faces around

him. When his lips parted, a feverish, incoherent babbling

issued, and nothing more. His wife began to weep softly,

unwilling to obtrude her grief upon the attention of men.

"If they're not of the duke's gentry," said the hunchback, "let them say what they are. Let us hear what sort of common men they may be."

"There's no other way but to tell them," said the baron. "Shall I do it?"

"Speak out. It's as well to be hanged by the duke's hangman as to be stabbed in the back by these fellows," said Tizzo.

The baron looked calmly around him. His clothes had been pulled half off his back, but he bore himself always with a good deal of dignity, and yet there was a cheerfulness about his bulldog face and the wine-red of it that could not help appealing to ordinary men.

He said: "To be short—you've heard the duke's criers proclaiming a reward of five hundred ducats through the streets for the capture of Baron Melrose and Captain Tizzo. We are they!"

There was not a whisper in answer, for a moment. Through the silence, Tizzo heard the grinding of the fodder which the cows were consuming, tossing their heads from time to time to tear out long streamers of the hay and then lick it easily into their mouths. They observed this human scene with bland, indifferent eyes.

The hunchback was the first to speak, and he sneered: "The baron? I know little about him. But Captain Tizzo is the man who cut through the street chains in Perugia. Everybody in Italy knows that story. Now I ask you, all my masters, if this spindling fellow has the arms or the shoulders to strike such strokes? Could he sway the ax that might deal such blows? Answer me, any man who dares to say so?"

The growl was a convincing reply. They meant business, now, and quick business.

Tizzo said: "There are some of you who never saw a small cat scratch the nose of a big dog and make him run off, howling. I say that I am he who cut the chains at Perugia. And in my hand is the ax that dealt the strokes."

This statement made a very obvious impression. But the hunchback took the ax suddenly from the grasp of Tizzo and held it high over his head. The lantern-light sent a blue flickering over the fine steel of the ax-head.

"You hear what he says?" declared the hunchback. "Now look with your own eyes on the ax that he carries! Are any of you fools enough to believe him? Why, here's an ax so light that it hardly fills half my hand!"

The old man put in: "Neighbor Berte, you still have the old Austrian helmet with the dents that the Swiss swords knocked into it; but none of their swords would carve through it. Bring it here and let the young man try the edge of his ax on it, if he thinks he can manage the trick."

Berte laughed and showed a mouth in which there was not a single tooth, though he was a young man. The bread he ate constantly lacerated his gums, and therefore his lips were continually edged with drying blood.

He said: "I'll bring the helmet in two minutes. Wait for me here!"

HE was gone at once. The hunchback, with a grin, leaned

back against a stanchion and stared into the face of Tizzo.

"You have a couple of minutes to live, brother," he said. "Tie the hands of the fellow who calls himself Baron Melrose, some of you. We'll leave this lying captain the use of his hands until he's proved the lie with the ax in his grip... Here, stand back a little. Give me that club... I take my place behind this man who calls himself Tizzo of Perugia... When he deals the blow to the helmet, if his ax fails to cut a good gash in the steel, that moment I bring down my club on his head and see how far his brains will spatter. Is that a fair judgment?"

They laughed, all those wolfish men, and nodded at one another.

"A fairer judgment man Luigi had!" they said.

Tall Berte now returned, and put on the stump of a post an old conical, open helmet of great weight and thickness of metal, no matter how old its workmanship might be.

"There!" said Berte, stepping back, "That old headpiece has saved lives in its day. It may be the losing of another life now that it's grown so old-fashioned. Step up, signore! Step up and try your luck! The five-foot Swiss swords could do no more than knock those dents into it. See if your ax can slash through it. What? Never hang back! Those were greater strokes than you claim to have struck in Perugia!"

Tizzo, freed, stepped forward with his ax and took the helmet in his hand.

It was even more massive to the touch than it was to the eye. The solid weight of it surprised him, and he saw that the entire top of the headpiece was doubly reinforced.

He glanced up with a smile at the faces around him.

"This is a good, tough nut to crack," said Tizzo. "But give me elbow room, friends, and I'll try my hand at it. Keep out of the swing of my ax, though."

He weighted the ax first in his left hand and then his right, as though he intended to strike it with a single arm. But now he took the well-balanced weapon in a double grasp and swung it to the right and to the left in sweeping circles. Suddenly he reversed the sway. The ax swept up on high. His body, not more than middle height at the most, seemed to stretch whole inches taller. It curved backward with a swift and sudden tension and then, like a full-drawn bow when the string is released, all that accumulated tension of muscle and nerve released.

The ax flashed too swiftly for the eye to follow. It was a blue glint in the lantern-light. Right in the center of the helmet the blow struck with a clang, followed by a splintering noise.

Tizzo straightened slowly from that great effort. And a groan of profound wonder came from the men around him. The hunchback, grunting with awe that was almost terror, had fallen on his knees. He picked up one half of the cloven helmet. With the other hand he traced the crack which the ax had cut through the post beneath.

BY day Cesare Borgia preferred to sleep; by night he usually was up and about, but on this night he sat gloomily in front of his casement with his chin dropped on his big hands. No one would have dared to keep him company or even speak to him at such a time, except that same young Florentine envoy, Niccolò Machiavelli.

He, with a soft step, paced up and down the room, speaking from time to time, sometimes humming a phrase of music, and paying no heed to the continual silence with which Cesare Borgia received his remarks. Here the door was opened a crack and the voice of the master poisoner, Bonfadini, murmured: "A letter from Captain Tizzo!"

"That is what I've been waiting for," said the Borgia, in a sudden, loud voice. "Bring it in. Read it, Alessandro! From what place does it come?"

"A place where men have red blood in them," said Bonfadini. "There's enough of that color on the letter. And the messenger dropped dead from his horse when he reached Forli."

"Ah? Ah?" muttered the duke. "How does it come that I can spend fortunes on men, and yet I never have people ready to die for me as they're ready to die for that penniless adventurer of a Tizzo?"

"Money only buys the time of men," said Machiavelli.

"What buys their hearts' blood, Niccolò?"

"Love," said the Florentine, and laughed a little.

"The letter! The letter!" said the Borgia. "I'm a new man before I hear even a word of it. Tizzo would never send a letter unless there were something worth while inside it."

Bonfadini, breaking open the writing, now read aloud, holding the page close to the small flame of the single lamp in the room.

"'My dear lord: A parrot died for me the other day, and that's why I'm alive to write this letter.

"'Duke Guidobaldo received me with every courtesy and listened like a scholar while I made my speech about your deep-seated affection for his excellency and your desire to join hands with him in public and in private war. Once I thought he was about to smile; but he swallowed it. He took the care of the countess out of my hands at once, and in such a way that I could not protest without doubting his intention to hold her as a safe prisoner at your disposal—'"

"D'you see, Niccolò?" said the duke. "I told you how it would work. Guidobaldo took the countess into his own hands, and it will need fighting to get her away from him again... I have a perfect cause for war..."

"You will have more causes before that letter is ended," said Machiavelli.

BONFADINI read on: "'Presently two cups of spiced wine

were sent to our room in the night for sleeping draughts; and if

we had drunk them we would still be asleep, my father and I,

without ever a dream. But we gave a taste to a parrot in the room

and he dropped asleep in time to warn us. The same sleep that we

all come to at the end of living. There were soldiers at the

door; we got out the window, onto the roof, and found an old

crone who liked red hair and let us down to the street. There we

fell in with a mob who wanted to knife us as members of the

gentry, because the gutter-sweepings and riff-raff of this town

seem to hold grudges against the blue-bloods and even feel that

one man is as good as another.

"'They were about to cut our throats when I managed to cut the Gordian knot, literally, with a stroke of my ax. And now we are accepted as good fellows—a title which seems to be incomparably above that of kings or emperors in the opinion of these queer people. They swear to die rather than give us up to the duke, though he has raised the price on our heads from five hundred to a thousand ducats. His idea seems to be that we are to drop forever out of sight in Urbino, after which he will be able to send you word that your envoys got drunk and were killed in a stupid brawl, leaving the poor countess in his hands, and he remains your humble servant, as ever.

"'We have tried to get out of the town, but every inch of the walls is watched; this letter coming to your hands will be proof that some one of my new friends in Urbino has risked his life to carry word to you.

"'Now that you have read this far, sound the trumpets and orders to horse, and away, because—'"

HERE Cesare Borgia shouted suddenly, with a lion's roar:

"Sound horns! Sound to horse! To horse!"

He added? "I'll take Tizzo at his word!"

A distant voice called out, faintly heard through the walls, and a moment later strong trumpets were blowing, followed by a rushing of feet through the court below.

Cesare Borgia began to laugh as he listened to the rest of the letter.

"'...Because at the end of the fourth day from this writing, which is on Monday, I intend, if a single Romagnol spear shines in the passes about Urbino, to gather about me as many of the rabble as can bear arms of one sort or another and rush the Porta del Monte. If I can capture that one gate and let in a few companies of my lord's best fighting men, trust me that they will be enough to stab Urbino to the heart. If I cannot capture and hold the gate until your troops are inside the walls, don't try the attack because the town is invulnerable, and there are plenty of good soldiers inside it.

"'However, those good soldiers will only fight so long as they have the advantages. One and all, they hate everything about Duke Guidobaldo except his money. Once you can break into the town, they will run tike rats; unless perhaps a garrison remains in the palace, which is a fort within a fort.

"'My lord, everything depends on haste and speed.

"'I see that I have been dropped as a bait into the mouth of the shark. I have managed to jump out of his mouth again, but his teeth are on all sides of me, sharper than swords.

"'For these reasons, I cannot send you my affection, but I can send you my duty. My hair is not yet gray.— Tizzo.'"

The Borgia already was up and striding for the door.

"You've heard!" he called. "What do you say to this, Niccolò?"

"I say," said Machiavelli, "that either you will bruise and break your hands on those great walls and heights of Urbino, or else you will have a dukedom for the mere gesture of taking. With three more men like Tizzo, you would have half the towns of Italy in your hands inside a year."