RGL e-Book©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book©

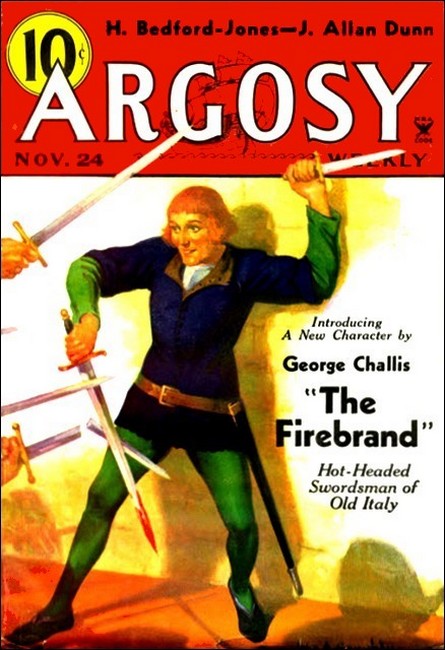

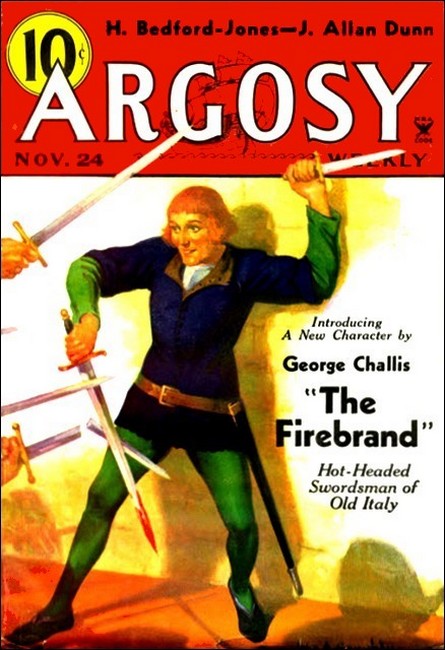

Argosy, November 24, 1934, with first part of "The Firebrand"

In 1934-1935 Max Brand, writing under the name of "George Challis" penned a series of seven swashbuckling historical romances set in 16th-century Italy. These tales all featured a character, Tizzo, a master swordsman, nicknamed "Firebrand" because of his flaming red hair and flame-blue eyes, and were first published in Argosy.

The original titles and publication dates of the romances are:

1. The Firebrand, Nov 24 and Dec 1 (2 part serial)

2. The Great Betrayal, Feb 2-16, 1935 (3 part serial)

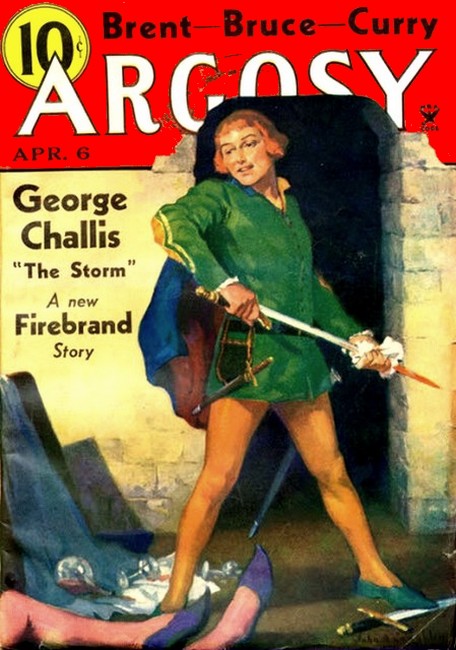

3. The Storm, Apr 6-20, 1935 (3 part serial)

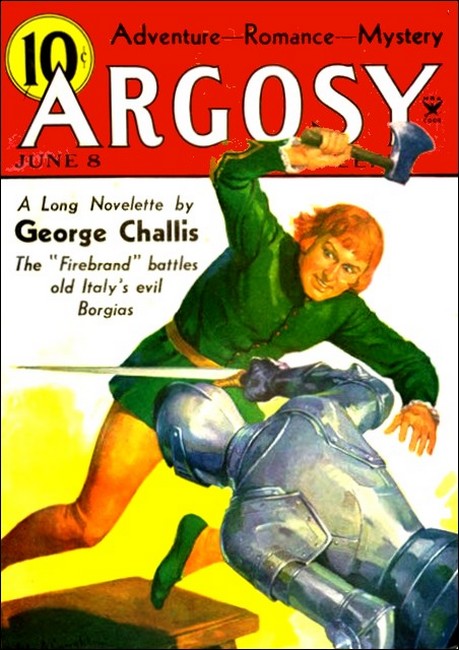

4. The Cat and the Perfume Jun 8, 1935 (novelette)

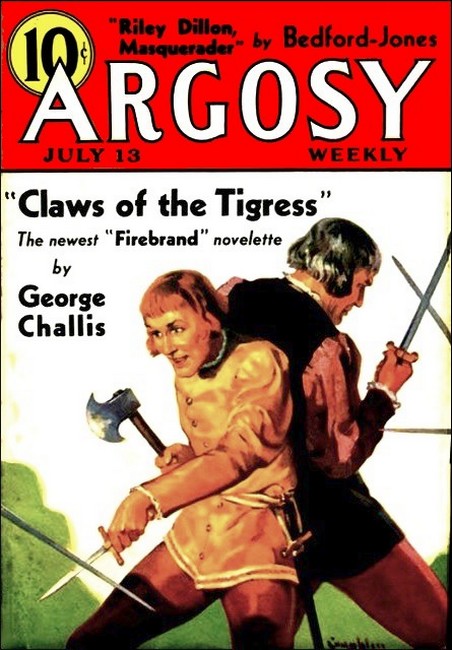

5. Claws of the Tigress, Jul 13, 1935 (novelette)

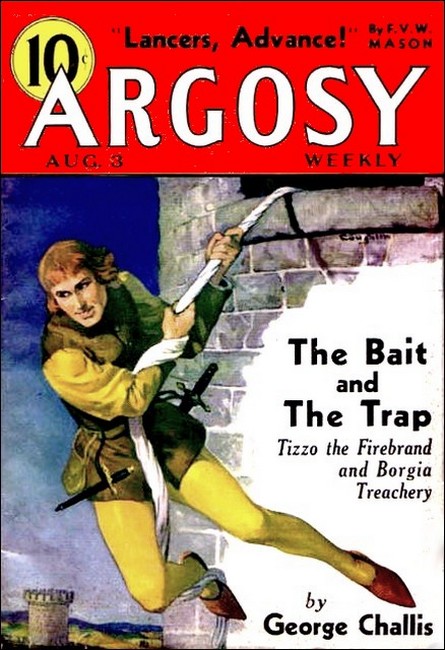

6. The Bait and the Trap, Aug 3, 1935 novelette

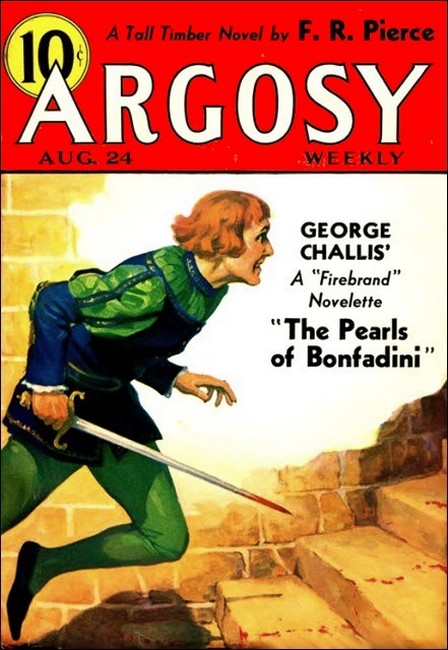

7. The Pearls of Bonfadini, Aug 24, 1935 (novelette)

The digital edition of The Firebrand offered here includes the original magazine illustrations and a bonus section with a gallery of the covers of the issues of Argosy in which the seven romances first appeared.

—Roy Glashan, December 2019.

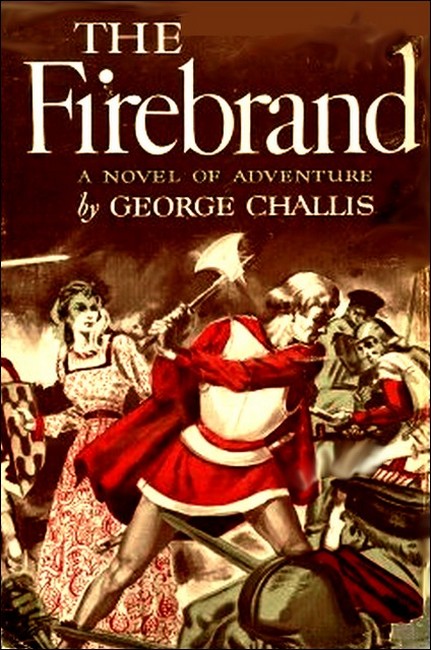

"The Firebrand," Harper & Brothers, New York, 1950

LUIGI FALCONE at fifty-five had lost some hair from his head and some speed from his foot, but his shoulders were as strong and his hands almost as quick as in those days when he had been famous with spear and sword. Now, stepping back with a wide gesture of both sword and small target, he cried out, "Tizzo, you are asleep! Wake up! Wake up!"

Tizzo, given the name of Firebrand because his hair was flame red and his eyes were flame blue, looked up at the blue Italian sky and then through the vista of the trees toward Perugia which in the far distance threw up its towers like thin arms.

"Well, the day is warm," said Tizzo, and yawned.

But Tizzo himself was not warm. All the exercise of wielding the target and the long, heavy sword had hardly brought a moisture to his forehead or caused him to take a single deep breath, partly because he had been stepping through the fencing practice so carelessly and partly because—though he was neither tall nor heavy—he was muscled as supple and smooth as a cat.

"The day is warm but you are not warm, Tizzo!" exclaimed Falcone. "God has given you nothing but a pleasant sort of laughter. You lack two inches of six feet. I could button you almost twice inside of one of my jackets. Nothing but skill can make up for the lack of weight in your hand; and here I am giving you my time, teaching you my finest strokes, and yet you sleep through the work! If you could touch me twice with the point or once with the edge, I'd give you whatever you ask."

Tizzo stopped yawning and laughed that pleasant laughter which had commended him to the eye of rich Falcone fifteen years before when Luigi rode through the street of the little village. Through a swirl of fighting, scrambling lads he had heard screaming and laughter. The screaming came from a lad who had been cornered against a wall. The laughter came from a redheaded youngster who was pommeling the bigger boy.

So Falcone, stopping the fight, asked questions. The sound of that laughter had reminded him of his own childless years and empty, great house on the hill. To most Italians red hair and blue eyes would not have been attractive, but Falcone was one who always chose the unusual. That was why he had taken Tizzo home with him. The boy had no other name. Mother and father were unknown. He had simply grown up in the streets like a young wolf running along with many others of the same unmothered kind; they were the brood of war which was scattered up and down Italy.

He had been a page, a valet, and then like the rightful son of the house of Falcone he had been educated with all care. Falcone, turning from war to the adventures of the study and the golden mines of Greek literature which were dazzling the wits of the learned throughout the Western world, had Tizzo trained in the same tongues which he himself had mastered. He was very fond of the slender youth, but that fire which had flamed in the lad when he ran wild through the streets of the village had grown dim. What he did was done well, without effort, without enthusiasm. And the big, headlong nature of Falcone was disgusted by that casual response, that ceaseless indifference.

Now, however, that old shimmer of flame blue glanced in the eyes of Tizzo as it had not shone for years.

"Shall I have the rest of the day to go where I wish and do what I please?" he asked. "If I touch you twice with the point or once with the edge, shall I have that gift?"

Falcone stared.

"What would you do with so many hours?" he asked. "You could not travel as far as Perugia in that time. What would you do?"

Tizzo shrugged his shoulders.

"But you have what you please and a horse to take you on the way," said Falcone, "if you touch me—edge or point—a single time!"

Tizzo laughed and threw the target from his arm. "What? Are you giving up before you begin?" demanded Falcone.

"Why should I have that weight in my hand?" asked Tizzo. "Now—on your guard—"

And he came gliding at Falcone.

In that day of fencing, when men were set to ward off or deliver tremendous thrusts or sweeping cuts that might cleave through plate armor, there was generally a forward posture of the body, both arms thrust a little out. This caused stiffness and slowness, but it braced a man against every shock. It was in this manner that Falcone stood, scowling out of his years of long experience, at that flame-headed lad who came in erect and swift and delicately poised, like a dancer.

Falcone feinted with the point and then made a long sweeping cut which if it had landed, in spite of the blunted edge of the sword, certainly might have broken bones.

But the sword whirred through the empty air. Tizzo had vanished from its path. No, he was there again in flesh and laughter on the right. Falcone, growling deeply in his throat, made a sudden attack. Strokes downright and sidewise, dangerous little upcuts, darting thrusts he showered at Tizzo.

Sometimes a mere touch of steel against steel made the ponderous stroke of Falcone glance past its target, a hair's breadth from head or body. Sometimes a twist of the body, a short, lightning pass of the feet deceived the sword. Falcone, sweat streaming down his face, attacked that laughing shadow with redoubled might and in the midst of his attack felt a suddenly light pressure against his breast. He could hardly be sure for an instant. Then he realized that Tizzo had stepped in and out, moving his whole body more swiftly than most men could move the hand.

It was a touch, to be sure—with the point and exactly above the heart!

Luigi Falcone drew back a little and leaned on his blade.

"Quick! Neat! A pretty stroke! And worth not a straw against a man in armor."

"In every armor there are joints, crevices," said Tizzo. "Where is there armor through which a wasp cannot sting, somewhere? And where a wasp can sting the point of a sword can follow!"

"So?" said Falcone, through his teeth. He was very angry. He had a dim suspicion that for years, perhaps, this pupil of his had been playing idly through their fencing bouts. "Now, try again—"

He fell on guard. There would be no rash carelessness, now. His skill, his honor, almost his good name were involved in keeping that shadow dancer from touching him with the sword again. Well and warily, with buckler and ready sword, he watched the attack of Tizzo.

It was a simple thing. There was no apparent device as Tizzo walked straight in toward danger. But just as he stepped into reaching distance his sword—and his body behind it—flickered to this side and to that. A ray of sunlight flashed into the eyes of Falcone. Something cold touched him lightly in the center of the forehead. And Tizzo stood laughing at a little distance again.

Falcone wiped his forehead and looked at his hand as though the touch of the sword point must have left a stain of blood. His hand was clean, but his heart was more enraged.

"Have you been making a fool of me?" he shouted. "Have you been able to do this for years—and yet you have let me sweat and labor and scold? Have you been playing with me like a child? Take your horse and go. And stay as long as you please! Do you hear? As long as you please! I shall not miss you while you are away. Cold blood never yet made a gentle knight!"

He had a glimpse of Tizzo standing stiff and straight with the look of one who has been wounded deeply, near to the life.

But the anger of Falcone endured for a long time. It made him stride up and down through his room, glowering out the window, stamping as he turned in the corner. Now and again he knit his great hands together and groaned out with a wordless voice.

And every moment his rage increased.

He had rescued a nameless child from the streets. He had poured out upon the rearing of the youngster all that a man could give to his own son. And in return the indolent rascal had chosen to laugh up his sleeve at his foster father!

Falcone shouted aloud. A servant, panting with fear and haste, jumped through the doorway.

"Tizzo! Bring him to me! On the run!" cried Falcone.

The broad face of the servant squinted with a malicious satisfaction. He was gone at once, and Falcone continued his striding with his rage hardening, growing colder, more deadly, every moment.

It was some time before the servant returned again, this time sweating with more than fear. He had been running far.

"He is not in his room," reported the man. "He is not at the stables or practicing in the field at the ring with his lance. He has not even been near his favorite hawk all day. He was not with the woodmen, learning to swing their heavy axes—a strange amusement for a gentleman! I ran to the stream but he was not there fishing. I asked everywhere. He has not been seen since he was fencing in the garden—"

Falcone, raising his hand, silenced this speech, and the fellow disappeared. Then he went to the room of Tizzo to see for himself.

The big hound rose from the casement where it was lying, snarled at the intruder, and crossed to the high-built bed as though it chose to guard this point most of all. Falcone, even in his anger, could not help remembering that Tizzo could make all things love him, men or beasts, when he chose. But how seldom he chose! The old master huntsman loved Tizzo like a son; so did one or two of the peasants, particularly those woodsmen who had taught him the mastery of their own craft in wielding the ax; but the majority of the servants and the dependents hated his indifference and his jests, so often cruel.

Falcone saw on the table in the center of the room—piled at either end with the books of Tizzo's study—a scroll of cheap parchment on which beautiful fresh writing appeared.

In the swift, easy, beautiful smooth writing of Tizzo, he read,

Messer Luigi, my more than father, benefactor, kindest of protectors, it is true that I have no name except the one that I found in the street. And yet I feel that my blood is not cold—

Falcone, lifting his head, remembered that he had used this phrase. He drew a breath and continued.

—and I have determined to take the permission which you gave me in your anger today. I am going out into the world. I think this afternoon I may be close to an opportunity which will take me away—in a very humble service. I shall stay in that service and try to find a chance to prove that my blood is as high as that of an honest man. If my birth is not gentle, at least I hope to show that my blood is not cold.

The wine and the meat of your charity are in themselves enough to make me more than a cold clod. If I cannot show that gentle fare has made me gentle, may I die in a ditch and be buried in the bellies of dogs.

Kind Messer Luigi, noble Messer Luigi, my heart is yearning, as I write this, to come and fling myself at your feet and beg you to forgive me. If I laughed as I fenced with you, it was not that I was sure of beating you but only because that laughter will come sometimes out of my throat even against my will.

Is there a laughing devil in me that is my master?

But if I came to beg your forgiveness, you would permit me to stay because of your gentleness. And I must not stay. I must go out to prove that I am a man.

Perhaps I shall even find a name.

I shall return with honor or I shall die not worthy of your remembering. But every day you will be in my thoughts.

Farewell. May God make my prayers strong to send you happiness. Prayers are all I can give.

From a heart that weeps with pain, farewell!

Tizzo

There were, in fact, a number of small blots on the parchment. Falcone examined them until his eyes grew dim and the spots blurred. Then he lifted his head.

It seemed to him that silence was flowing upon him through the chambers of his house.

AT the village wineshop, which was also the tavern, a number of ragged fellows were gathered, talking softly. They turned when they saw one in the doublet and hose and the long, pointed shoes of a gentleman enter the door; and they rose to show a decent respect to a superior. He waved them to sit again and came down the steps to the low room with his sword jingling faintly beside him.

Now that he was well inside the room and the sunlight did not dazzle the eyes of the others, they recognized Tizzo.

They remembered him from the old days, as keen as a knife for every mischief. They remembered that he had been one of them—less than one of them—a nameless urchin on the street, a nothing. Chance had lifted him up into the hall of the great, the rich Luigi Falcone. And therefore the villagers hated him willingly and he looked on them, always, with that flame-blue eye which no man could read, or with that laughter which made both men and women uneasy, because they could never understand what it might mean.

Now he walked up to the shopkeeper, saying: "Giovanni, has that stranger, the Englishman, found a manservant that pleases him? One that is good enough with a sword?"

Giovanni shook his head.

"He put them to fight one another. There were some bad cuts and bruises and Mateo, the son of Grifone, is cut through the arm almost to the bone. But the Englishman sits there in the back room and laughs and calls them fools!"

"Give me a cup of wine, Giovanni."

"The red?"

"No. The Orvieto. Red wine in the middle of a hot day like this would boil a man's brains."

He picked up the wine cup which Giovanni filled and was about to empty it when he remembered himself, felt in the small purse attached to his belt, and then replaced the wine on the counter.

"I have no money with me," he said. "I cannot take the wine."

"Mother of Heaven!" exclaimed Giovanni. "Take the wine! Take the shop along with it, if you wish! Do you think I am such a fool that I cannot trust you and my master, Signore Falcone?"

"I have left his house," said Tizzo, lifting his head suddenly. "And you may as well know that I'm not returning to it. The noble Messer Luigi now has nothing to do with my comings and goings—or the state of my purse!"

He flushed a little as he said this, and saw his words strike a silence through the room. Some of the men began to leer with a wide, open-mouthed joy. Others seemed turned to stone with astonishment. But on the whole it was plain that they were pleased. Even Giovanni grinned suddenly but tried to cover his smile by thrusting out the cup of wine.

"Here! Take this!" he said. "You have been a good patron. This is a small gift but it comes from my heart."

"Thank you, Giovanni," said Tizzo. "But charity would poison that wine for me. Go tell the Englishman that I have come to try for the place."

"You?" cried Giovanni. "To become a servant?"

"I've been a master," said Tizzo, "and therefore I ought to make a good servant. Tell the Englishman that I am here."

"There is no use in that," said Giovanni. "The truth is that he rails at lads with red hair. You know that Marco, the son of the charcoal burner? He threw a stool at the head of Marco and drove him out of the room; and he began a tremendous cursing when he saw that fine fellow, Guido, simply because his hair was red, also."

"Is the Englishman this way?" asked Tizzo. "I'll go in and announce myself!"

Before he could be stopped, he had stepped straight back into the rear room which was the kitchen, and by far the largest chamber in the tavern. At the fire, the cook was turning a spit loaded with small birds and larding them anxiously. A steam of cookery mingled with smoke through the rafters of the room; and at a table near the window sat the Englishman.

Tizzo, looking at him, felt as though he had crossed swords with a master in the mere exchange of glances. He saw a tall man, dressed gaily enough to make a court figure. His short jacket was so belted around the waist that the skirts of the blue stuff flared out; his hose was plum colored, his shirtsleeves—those of the jacket stopped at the elbow—were red, and his jacket was laced with yellow. But this young and violent clashing of colors was of no importance. What mattered were the powerful shoulders, the deep chest, and the iron-gray hair of the stranger. In spite of the gray he could not have been much past forty; his look was half cruel, half carelessly wild. Just now he was pointing with the half consumed leg of a roast chicken toward the spit and warning the cook not to let the tidbits come too close to the flame. He broke off these orders to glance at Tizzo.

"Sir," said Tizzo, "are you Henry, baron of Melrose?"

"I am," answered the baron. "And who are you, my friend?"

"You have sent out word," said Tizzo, "that you want to find in this village a servant twenty-two years old and able to use a sword. I have come to ask for the place."

"You?" murmured the baron, surveying the fine clothes of Tizzo with a quick glance.

"I have come to ask for the place," said Tizzo.

"Well, you have asked," said the baron.

He began to eat the roast chicken again as though he had finished the interview.

"And what is my answer?" asked Tizzo.

"Redheads are all fools," said the baron. "In a time of trouble they run the wrong way. They have their brains in their feet. Get out!"

Tizzo began to laugh. He was helpless to keep back the musical flowing of his mirth, and yet he was far from being amused. The Englishman stared at him.

"I came to serve you for pay," said Tizzo. "But I'll remain to slice off your ears for no reward at all. Just for the pleasure, my lord."

My lord, still staring, pushed back the bench on which he was sitting and started up. He caught a three-legged stool in a powerful hand.

"Get out!" shouted the baron. "Get out or I'll brain you—if there are any brains in a redheaded fool."

The sword of Tizzo came out of its sheath. It made a sound like the spitting of a cat.

"If you throw the stool," he said, "I'll cut your throat as well as your ears."

And he began to laugh once more. The sound of this laughter seemed to enchant the Englishman.

"Can it be?" he said. "Is this the truth?"

He cast the stool suddenly to one side and, leaning, drew his own sword from the belt and scabbard that lay nearby.

"My lords—my masters—" stammered the cook.

"Look, Tonio," said Tizzo. "You have carved a good deal for other people. Why don't you stand quietly and watch them carving for themselves?"

"And why not?" asked Tonio, blinking and nodding suddenly. He opened his mouth and swallowed not air but a delightful idea. "I suppose the blood of gentlemen will scrub off the floor as easily as the blood of chickens or red beef. So lay on and I'll cheer you."

"What is your name?" asked the baron.

"Tizzo."

"They call you the Firebrand, do they? But what is your real name?"

"If you get any more answers from me, you'll have to earn them," said Tizzo. "Tonio, bolt the doors!"

The cook, his eyes gleaming, ran in haste to bar the doors leading to the guest room and also to the rear yard of the tavern. Then he climbed up and sat on a stool which he placed on a table. He clapped his hands together and called out: "Begin, masters! Begin, gentlemen! Begin, my lords! My God, what a happiness it is! I have sweated to entertain the gentry and now they sweat to entertain me!"

"Now the gentry sweat to entertain me!" shouted the happy cook.

"It will end as soon as it begins," said the Englishman, grinning suddenly at the joy of the cook. "But—I haven't any real pleasure in drawing your blood, Tizzo. I have a pair of blunted swords; and I'd as soon beat you with the dull edge of one of them."

"My lord," said Tizzo, "I am not a miser. I'll give my blood as freely as any tapster ever gave wine—if you are man enough to draw it!"

The Englishman, narrowing his eyes, drew a dagger to fill his left hand. "Ready, then," he said. "Where is your buckler or dagger or whatever you will in your left hand?"

"My sword is enough," said Tizzo. "Come on!"

"My sword is enough," said Tizzo. "Come on!"

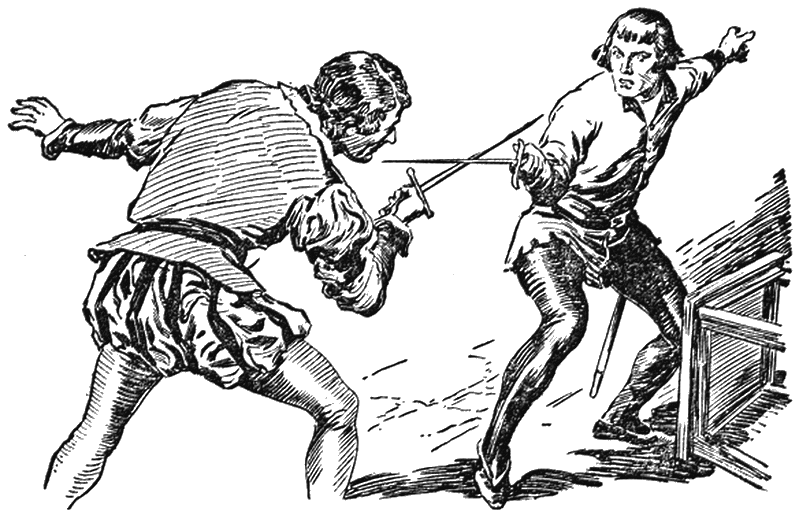

And he fairly ran at the baron. The other, unwilling to have an advantage, instantly threw the dagger away; the sword blades clashed together, and by the first touch Tizzo knew he was engaged with a master.

He was accustomed to the beautifully precise, finished swordsmanship of Luigi Falcone, formed in the finest schools of Italy and Spain; he knew the rigid guards and heavy counters and strong attacks of Falcone; but in the Englishman he seemed to be confronting all the schools of fencing in the world. His own fencing was a marvel of delicacy of touch and he counted inches of safety where other men wanted to have feet; but the Englishman had almost as fine a hand and eye as his own, with that same subtlety in the engagement of the sword blade, as though the steel were possessed of the nerves and wisdom of the naked hand.

Moreover, the Baron Melrose was swift in all his movements, with a stride like the leap of a panther; and yet he seemed slow and clumsy compared with the lightning craft of Tizzo. The whole room was aflash and aglitter with the swordplay. The noise of the stamping and the crashing of steel caused Giovanni and others to beat on the door; but the cook bellowed out that there was a game here staged for his own entertainment, only. The cook, in an ecstasy, stood up on his table and shouted applause. With his fat hand he carved and thrust at the empty air. He grunted and puffed in sympathy with the failing strength of the Englishman—who now was coming to a stand, turning warily to meet the constant attacks of Tizzo; and again the cook was pretending to laugh like Tizzo himself as that youth like a dance of wildfire flashed here and there.

And then, feinting for the head but changing for the body suddenly, Tizzo drove the point of his sword fairly home against the target. The keen blade should have riven right through the body of Melrose. Instead, by the grace of the finest chance, it lodged against the broad, heavy buckle of his belt. Even so, the force of the lunge was enough to make the big man grunt and bend over.

But instead of retreating after this terrible instant of danger, he rushed out in a furious attack.

"Now! Now! Now!" he kept crying.

With edge and point he showered death at Tizzo, but all those bright flashes were touched away and seemed to glide like rain from a rock around the head and body of Tizzo. And still he was laughing, breathlessly, joyfully, as though he loved this danger more than wine.

"Protect yourself, Tizzo!" cried the cook. "Well done! Well moved, cat; well charged, lion! But now, now—"

For Tizzo was meeting the furious attack with an even more furious countermovement; and the Englishman gave slowly back before it.

"Now, Englishman—now, Tizzo!" shouted the cook. "Well struck! Well done! Oh, God, I am the happiest cook in the world! Ha—"

He shouted at this moment because the combat had ended suddenly. The Englishman, hard-pressed, with a desperate blue gleam in his eyes—very like the same flame-blue which was in the eyes of Tizzo—made at last a strange upward stroke which looked clumsy because it was unorthodox; but it was delivered with the speed of a cat's paw and it was, at the same instant, a parry, and a counterthrust. It knocked the weapon of Tizzo away and, for a hundredth part of a second, the point of the baron was directly in front of Tizzo's breast.

But the thrust did not drive home.

Tizzo, leaping away on guard, was ready to continue the fight; but then, by degrees, he realized what had happened.

"You could have cut my throat!" he said.

And he lowered his weapon and stood panting, leaning on the hilt of his sword.

"I would give," said Tizzo, "ten years of my life to learn that stroke."

The baron tossed his own blade away. It fell with a crash on the table. And now he held out his right hand.

"That stroke," said he, "is worth ten years of any life—but I was almost a dead man half a dozen times before I had a chance to use it! Give me your hand, Tizzo. You are not my servant, but if you choose to ride with me, you are my friend!"

Tizzo gripped the hand. The grasp that clutched his fingers was like hard iron.

"But," said the baron, "you have only come here as a jest—you are the son of a gentleman. Not my service—not even my friendship is what you desire. It was only to measure my sword that you came, and by the Lord, you've done it. Except for the trick, I was a beaten man. And—listen to me—I have faced Turkish scimitars and the wild Hungarian sabers. I have met the stamping, prancing Spaniards who make fencing a philosophy, and the quick little Frenchmen, and cursing Teutons—but I've never faced your master. In what school did you learn? Sit down! Take wine with me! Cook, unbolt the door and give wine to everyone in the shop. Broach a keg. Set it out in the street. Let the village drink itself red and drunk. Do you hear?

"Put all your sausages and bread and cheese on the tables in the taproom. If there is any music to be found in this place, let it play. I shall pay for everything with a glad heart and a happy hand, because today I have found a man!"

The cook, unbarring the door, began to shout orders; uproar commenced to spread through the little town; presently all the air was sour with the smell of the good red wine of the last vintage. But young Tizzo sat at the table with the baron hearing nothing, tasting nothing, for all his soul was staring into the future as he heard the big man speak.

THEY had not been long at the table when a strange little path of silence cut through the increasing uproar of the taproom, and tall Luigi Falcone came striding into the kitchen. When he saw his protégé, he threw up a hand in happy salutation.

"Now I have found you, Tizzo!" he said. "My dear son, come home with me. Yes, and bring your friend with you. I read your message, and I've been the unhappiest man in Italy."

Tizzo introduced the two; they bowed to one another gravely. There was a great contrast between the immense dignity, the thoughtful and cultured face of Falcone, and the half handsome, half wild look of this man out of the savage North.

"It would be a happiness," said the Englishman, "to go anywhere with my new friend, Tizzo. But this moment I am leaving the village. I must continue a journey. And we have been agreeing to make the trip together."

Falcone sighed and shook his head.

"Tizzo cannot go," he said. "All that his heart desires waits for him here—Tizzo, you cannot turn your back on it."

Tizzo stood buried in silence which seemed to alarm Falcone, for he begged Melrose to excuse him and stepped aside for a moment with the younger man.

"It is always true," said Falcone. "We never know our happiness until it is endangered. When I found that you had gone, the house was empty. I read your letter and thought I found your honest heart in it. Tizzo, you came to me as a servant; you became my protégé; now go back with me and be my son. I mean it. There are no blood relations who stand close to me. I have far more wealth than I have ever showed to you. It is not with money that I wish to tempt you, Tizzo. If I thought you could be bought, I would despise and disown you. But I have kept you too closely to your books. Even Greek should be a servant and not a master when a youth has reached a certain age. And now when you return—I have been painting this picture while I hunted for you—you will enter a new life. Yonder is Perugia. I have friends in that city who will welcome you. You shall have your journeys to Rome to see the great life there. You shall enter the world as a gentleman should do."

Tizzo had started to break out into grateful speech, when the Englishman said, calmly but loudly, "My friends, I have heard what Messer Luigi has to say. It is my right to be heard also."

"My lord," said Falcone, "I have a right of many years over this young gentleman."

"Messer Luigi," said the Englishman, "I have a still greater right."

"A greater right?" exclaimed Falcone.

"We have pledged our right hands together," said the baron.

"A handshake—" began Falcone.

"In my country," answered the Englishman, "it is as binding as a holy oath sworn on a fragment of the true cross. We have pledged ourselves to one another; and he owes me ten years of his life."

"In the name of God," said Falcone, "how could this be? What have you seen in such a complete stranger, Tizzo?"

"I have seen—" said Tizzo. He paused and added: "I have seen the way down a beautiful road—by the light of his sword."

"But this means nothing," said Falcone. "These are only words. Have you given a solemn promise?"

"I have given a solemn promise," said Tizzo, glancing down at his right hand.

"I shall release you from it," said the baron suddenly.

"Ha!" said Falcone. "That is a very gentle offer. Do you hear, Tizzo?"

"I release him from it," said the Englishman, "but still I have something to offer him. Messer Luigi, it happens that I also am a man without a son who bears my name. Like you, I understand certain things about loneliness. We do not need to talk about this any more.

"But I should like to match what I have to offer against what you propose to give him."

"Ah?" said Falcone. "Let us hear."

"You offer him," said the Englishman, "an old affection, wealth, an excellent name, a great house, many powerful friends. Am I right?"

"I offer him all of those things," agreed the Italian.

"As for me," said the baron, "the home of my fathers is a blackened heap of stones; my kin and my friends are dead at the hands of our enemies in my country; my wealth is the gold that I carry in this purse and the sword in my scabbard."

"Well?" asked Falcone.

"In spite of that," said the Englishman, "I have something to offer—to a redheaded man."

Tizzo started a little and glanced sharply at the baron.

Melrose went on: "I offer you, Tizzo, danger, battle, suspicion, confusion, wild riding, uneasy nights—and a certain trick with the sword. I offer that. Is it enough?"

Falcone smiled. "Well said!" he answered. "You have a great heart, my lord, and you know something of the matters that make the blood of a young man warmer. But—what is your answer, Tizzo?"

Tizzo, turning slowly from the Englishman to Falcone, looked him fairly in the eye.

He said: "Signore, I shall keep you in my heart as a father. But this man is my master, and I must follow him!"

THEY had a day, said the baron, to get to a certain crossroads and they spent much of the next morning finding an excellent horse and some armor for Tizzo. Speed, said the baron, rather than hard fighting was apt to be the greatest requisite in the work that lay before them, therefore he had fitted Tizzo only with a good steel breastplate and a cap of the finest steel also which fitted on under the flow of his big hat. He carried, furthermore, a short, straight dagger which could be of value in hand to hand encounters and whose thin blade could be driven home through the bars of a visor or the eyeholes. He had taken, also, of his own choice, a short-handled woodsman's ax. This amazed the Englishman. He tried it himself, but the broad blade unbalanced his grasp.

"How can you handle a weight like that, Tizzo?" he asked. "You lack the shoulder and the hand to manage it."

Tizzo, with his careless laughter, loosened the ax from its place at his saddle bow and swung it about his head, cleaving this way and that. The thing became a feather. It whirled and danced. It swayed to this side and that as though parrying showers of blows—and all of this while in the grasp of a single hand.

"Practice will make even a bear dance!" said Tizzo. And then gripping the handle of the ax in both hands, he struck a thick branch from a tree under which the road passed at that moment. The big bough fell with a rustling sound to the highway, and Tizzo rode on, still laughing; but the baron paused a moment to examine the depth and the cleanness of the wound and to try the hardness of the wood with his dagger point.

"God help the head that trusts its helmet against your ax, Tizzo," he said. "A battle ax is a thing I have used, but a woodsman's ax never."

"If a battle ax were swung for half a day to fell trees," said Tizzo, "the strongest knight would begin to curse it. But a woodsman will know the balance of his ax as you know the balance of your sword, and the hours he works teaches him to manage it like nothing. I've seen them fighting with axes too, and using them to ward as well as to strike. So I spent some time with them every day for years."

They came in sight now of a fork in the road, and as they drew closer a carriage drawn by four horses swung out of a small wood and waited for them.

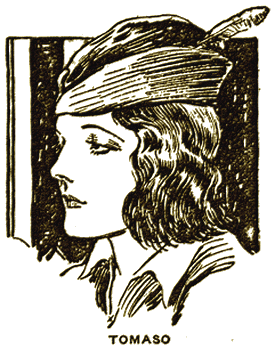

"There are our friends," said the baron. "Inside that coach is the lad we're taking to a safer home than the one he's been in. His name is Tomaso, and that's enough for you to know about him. Except that to take him safely and deliver him will bring us a good, handsome sum of money for our purses."

"I shall ask no questions," agreed Tizzo, delighted by this touch of mystery.

About the coach, which was heavy enough to need the stronger of the four horses to pull it over the rutted, unsurfaced roads, there were grouped a number of armed men, two on the driver's seat and two as postillions, while another pair stood at the heads of their horses. And each one of the six, it seemed to Tizzo, looked a more complete villain than the other. They were half fine and half in tatters, with a good weight of armor and weapons on every man of the lot.

A slender lad in a very plain black doublet and hose with a red cap on his head was another matter.

"Tomaso, I've told you to keep inside the carriage," said the baron angrily, as he rode up.

"What does it matter where there's nothing but blue sky and winds to see me?" asked Tomaso, in a voice surprisingly light, so that Tizzo put down the age of the lad at two or three years younger than the sixteen or seventeen which had been his first guess.

"Whatever you may be in other places," said Melrose, sternly, "when you ride with me, I am the master. Get into the carriage!"

Tomaso, in spite of this sternness, moved in the most leisurely manner to re-enter the carriage, with a shrug of his shoulders and a glance of contempt from his brown eyes.

After he was out of sight, one of the guards refastened the curtains that shut Tomaso from view.

"Why," said Tizzo, "he's only a child."

The baron pointed a finger at him. "Let me tell you," he said, "that you're apt to find more danger in Tomaso than in any man you'll meet in the whole course of your life. To horse, my lads. I'm glad to see you all safely here; and I've been true to my promise and found a good man to add to our party. My friends, this is Tizzo. They call him Firebrand because his hair is red; but his nature is as quiet as that of a pet dog. Value him as I do—which is highly. He will help us to get to the end of our journey."

There were only a few muttered greetings. One fellow with a long face and a patch over one eye protested: "It's a bad business stirring up hornets and then waiting for them to sting; or making these long halts in the middle of enemy country. Already we've been noted."

"By whom, Enrico?" asked the baron. "Who would think of searching this place? And you covered the marks of the wheels when you drove the carriage into hiding?"

"I covered the marks well enough. But a dog uses its nose, not its eyes, and it was a dog that led the man into the wood."

"Did you catch the fellow?" asked the baron, anxiously.

"How could we? There was not a single horse saddled. He came on us suddenly, whirled about, and was off. I caught up a crossbow and tried for him but missed," answered Enrico. "He rode away between those hills, and ever since, I've been watching to see trouble come through the pass at us. I was never for making the halt."

"Tush," said Melrose. "Everything will be well. Did that stranger who spied on you—did he see Tomaso?"

"He did—clearly—and Tomaso shouted to him."

"By God, Enrico, do you mean that Tomaso recognized him?"

"I don't know. It seemed that way. Very likely, too, because a thousand men are hunting for—Tomaso."

The baron groaned and ordered an instant start. He left Enrico and Tizzo as a rear guard to follow at a little distance, out of the dust raised by the clumsy wheels of the carriage; for his own part, the baron of Melrose went forward to spy out the way.

As they started forward, their horses at a trot, Enrico turned his ugly face to Tizzo and said: "So my lord found his redhead, eh? You're the prize, are you?"

Tizzo had felt himself on the verge of a mystery. Now he was sure that he was involved in the mystery itself. For some definite and singular purpose, the baron certainly wanted him. It was above all strange that in Italy he should be looking for redheaded young men. Might it be that he intended to use Tizzo to impersonate another character? In any event, it was certain that the baron was not a man to bother over small scruples. And Tizzo determined to be more wakeful than a hungry cat. He had a liking for the baron; he respected his strength and his courage; he hoped that through him the golden door of adventure might be opened; but he half expected that the big man was using him as the slightest of pawns in some great game.

The carriage horses dragged their burden through the hills, where the road wound blazing white among the vineyards and the dusty gray of the olive trees, often silvered by a touch of wind. The day was hot, the work was hard, and presently the team had to be rested.

As they halted to take breath, the baron rode apart with Tizzo, and dismounting behind a tall stone wall, he pulled out his sword. "For the first lesson!" he said, and as Tizzo drew his own blade, Melrose showed him, with the slowest movement of the hand, the details of that maneuver which had opened the guard of Tizzo like a handstroke. For several minutes he studied and practiced that strange combination of ward and counterstroke. He had not mastered it with his hand but he understood it with his mind before they went back to the others.

Tizzo asked him, on the way, why he had not used the irresistible force of that ward and counter earlier during their encounter in the kitchen. At this the baron chuckled. "Because I'm a fool," he said. "I was enjoying the sight of your good swordsmanship too much to want the thing to end."

"Yes," agreed Tizzo, smiling. "And besides, you were wearing a lucky buckle."

"Luck is the best friend that any soldier ever had," answered the baron. "When you learn to trust it, you have learned how to be happy. But, Tizzo, trust me, also!"

He said this with a certain gravity that impressed his companion. But when the journey through the late afternoon commenced again, there was still a pregnant doubt in the mind of Tizzo. That matter of the search for the redheaded young man—that unknown role for which he had been selected weighed much on his mind.

He kept his concerns to himself, however, as they drew on into the cooler evening. A wind had begun in the upper sky, whirling the clouds into thin, twisted streamers, but it had not yet reached the surface of the ground.

The carriage was being dragged up a fairly easy slope when the baron halted it by raising his hand. He reined his horse back at the same time, calling: "Enrico, do you see anything in those trees?"

Enrico, staring fixedly at the small grove of willows—thick, pollarded stumps, exclaimed: "I can't see into the trees, but I can see a dust over them that the wind never put there."

Now that it was pointed out, Tizzo could see the same thing—a few drifting wisps of dust high above the tops of the trees. If the baron paid heed to such small tokens as these, it proved the intensity of his care.

"If we go on, the road takes us straight past that place," he said, "Cesare, ride into those trees and see what sort of birds you can stir up."

But before Cesare could stir to execute the order, something whirred in a streak through the air and Tizzo received a heavy blow against his breastplate. A broken quarrel dropped to the ground, the steel point of it fixed deeply in the armor; and Tizzo heard at the same time the humming clang of the crossbow string, which sounded from the edge of the wood. As though this were the signal, a shout burst out from many throats and the brush at the edge of the willows appeared alive with men.

THE baron shouted to get the horses turned. The team was swinging around when a full volley of half a dozen of crossbow bolts darted from the brush and stopped the maneuver. One of the team dropped dead. Two others, badly wounded, began to squeal and plunge, dragging the carriage to the side of the road and smashing a wheel against a rock.

"Charge before they reload!" shouted the baron. "Tizzo! Enrico! With me, friends!"

He set the example, yelling over his shoulder: "Andrea, hold Tomaso; the rest, follow me!"

The other fellows of the baron's troop left the carriage and ran on foot to help their master, four of them sword in hand. But Tizzo rushed at the side of Enrico toward the brush. Crossbowmen, usually lightly armored, would make easy game; but there were enemies of a different quality to deal with in the woods. For out of them rode no fewer than five men-at-arms in complete armor, lances at rest. Those on either side were equipped in the most complete fashion, but he in the center wore flowing plumes from his helmet and the evening light brightened on the rich inlay of his armor.

With closed visors, like five death's-heads, the horsemen charged, shouting: "Marozzo! Marozzo!"

It was a name that Tizzo knew very well. No man in Perugia, not even among the family of the high and mighty Baglioni, was richer than gallant young Mateo Marozzo, the last heir of his family name.

Anxiously, Tizzo glanced toward the baron, because it seemed a madness to engage, half armed as they were, with five fully equipped riders like these. Their long spears threatened quick death and an ending to the fight before sword or ax or dagger ever could come into play.

But Baron Melrose did not slacken his pace for all the odds against him. As the men-at-arms appeared, he merely stood up in his stirrups and shouted in a thundering voice: "Ah, ha! Melrose! Melrose! Strike in! Strike in!" And with this battle cry he rushed first of the three against his enemy, swinging his sword for a stroke. Enrico did not hang back; and Tizzo was last of the trio to come to action.

The spears were not so dangerous as they looked. Tizzo could see that at once. On smooth ground that charge of the five ponderous warriors would have overwhelmed the baron's men at once; but the brush, the uneven ground staggered the galloping horses and made the lances waver from a true aim. Tizzo, hurling himself toward that brilliant plumed figure in the center, grasped his woodsman's ax, rode seated high in his saddle, and at the last moment dipped low. The lance of his enemy drove over his shoulder; the backstroke of the ax, in passing, glanced off the polished shoulder armor, and descending on the mailed arm of the rider, knocked the spear from his grasp.

As he turned his horse, Tizzo could see the crossbowmen in the shrubbery struggling energetically to reload their weapons, but they were armed with those powerful arbalests whose cords were pulled back by the use of a complicated tackle of pulleys and rope. The fastest of them still did not have a second quarrel in place as Tizzo reined in his horse and flung himself again at the knight.

He saw, as he swerved, that Enrico's horse was falling; injured by a misdirected thrust of a spear; and big Baron Melrose had engaged with his sword two of the men-at-arms. As for the three fellows on foot, they had paused. They saw their master overmatched, one of his best fighters already dismounted, and the battle definitely lost, it seemed.

Those two glances were enough to discourage Tizzo. But, if he were to die, he was determined to die fighting. The plumed knight, wheeling toward him, had unsheathed a long sword and now drove in his horse at a trot, wielding the sword with both hands.

"Marozzo!" he was shouting. "Marozzo! Marozzo!"

And Tizzo answered with a yell of: "Melrose! Long live Melrose!"

Then he swung up the axhead to meet the terrible downward sway of the sword. A sure eye and a swift hand made that parry true. The sword blade shattered with a tinkling sound, splintering and breaking at the point of impact.

But Marozzo—if this were in fact he—was still full of fight. He could see his fourth companion whirling and running his horse at a gallop to come to the rescue, so the knight of the plumed helmet snatched a mace from his saddlebow and drove at Tizzo.

The first ax-stroke had glanced. The second would not, Tizzo swore—not if he had truly learned from the woodsmen how to strike to a line. He aimed at the central one of the three plumes and then struck like a whirling flash of light.

The blow was true and deep and good. As the blade bit in, a savage hope came up in Tizzo that he had cloven the skull of the leader of the ambuscade. But it was only the crest that he shore away, while from the heavier, conical steel of the helmet itself the ax glanced a second time.

The weight of that blow made the helmet ring like a bell; and Marozzo fell helplessly forward on the pommel of his saddle and the neck of his horse.

The course of the battle was instantly changed.

The trotting horse of Marozzo moved him from the next stroke of that flashing ax, which certainly would have been a death blow. And as Tizzo swung his own horse about, with his cry of "Melrose! Melrose!" the four men-at-arms left off their individual battles and rushed to the rescue of their leader, who was sliding helplessly out of the saddle, stunned.

"Away!" shouted one of the ambushers. "Rescue the signore! Away, away! If he's dead, our necks will be stretched for it! Crossbowmen, cover us! The signore is hurt!"

In a moment the men-at-arms were withdrawing, one of them supporting their hurt master and the other three reining back their horses in the rear to keep a steady front against a new attack. The crossbowmen—there were eight of them in all—issued from the woods and fell in behind the riders, keeping their quarrels ready for discharge but making no offer to loose them at the baron's men. Quickly the entire troop was lost among the trees.

From the melee, two horses were left dead and one dying, but, what seemed a miracle, not a single man had received so much as a scratch. Luck had been with the baron and the plate armor of the men-at-arms had saved them. Only the leader had been injured to an unknown degree.

It was dusk before the dying horse was put out of pain; the carriage was abandoned; and with Tomaso mounted behind Melrose the party started on through the hills. The twilight gradually grew more and more dim and yet there had been light enough for Tomaso to look long and fixedly at Tizzo with a curious expression of admiration and hate in his brown eyes.

Baron Henry of Melrose was in high spirits in spite of the loss of the carriage. He said to Enrico: "You see what a redheaded man is worth, Enrico? And that was the famous knight Mateo Marozzo, you understand? Tell me, Tomaso! Was it not young Mateo? You ought to know his voice and he was shouting loudly enough until Tizzo tapped on his headpiece."

"I don't know," answered Tomaso.

He kept his one hand on the shoulder of the baron and the other gripped the high back of the saddle while Tomaso looked dreamily off across the hills.

"Answer me, Tomaso!" commanded the baron.

"My lord," said Tomaso, in his musical and quiet voice, "you could not get an answer from me with whips. Let me be quiet with my thoughts."

This calm insolence seemed very strange to Tizzo; it was still stranger that the rough baron made no retort; but perhaps that was because the spirits of Melrose were naturally very high since their lucky escape.

Luck was the theme of his talk—luck and the swift hand and the courage of Tizzo—until the falling of night left them all in silence except for the steady creaking of the saddle leather. Finally Tomaso began to sing in a pleasant but oddly small voice, to which Tizzo listened with such a singular pleasure that he paid no attention to the words; the voice and the music fed in him a hunger which he had never felt before.

Presently on a hilltop vague towers loomed against the sky and toward these they made their way, entering the streets of a ruined village such as one could find frequently throughout Italy. Fire had ravished the place and all of the smaller houses were tumbled this way and that while grass had begun to grow in the streets. The castle which topped the height was only partially destroyed during the sacking of the place ten years before, and it was here that the baron intended to spend the night. In the courtyard they built a fire and roasted meat on small spits, like soldiers. Some skins of wine, warm and muddy from the jostling of the day's riding, were opened. And while they ate, Tizzo kept looking from the pale, handsome face of the silent Tomaso to the upper casements of the castle which stared down at the firelight with dark and empty eyes.

Melrose said briefly: "One more good night of watching, my friends, and we shall be far away from the grip of the Baglioni with our treasure. This night—and afterwards we shall be at ease. Keep a good ward. Tizzo will be here in the court until midnight, and Enrico at the door of Tomaso's room. At midnight I'll take the watch here. Tizzo, be wary and alive. If you hear so much as a nightingale's song, call me. Up, Tomaso, and follow me. You sleep in one of the rooms above."

"Why not here in the open, where it's cool?" demanded Tomaso.

"Because the night air might steal you, my lad," said the baron. And he led Tomaso from the court and through the narrow black mouth of a postern door. Tizzo listened until the footfalls and the muffled chiming of steel had ceased.

But in his heart he had companionship enough. He had memories of this day which seemed to outweigh all the rest of his life. Two things stood out above the rest—the sword of the Englishman arrested in midthrust at his throat and that instant of incredible delight when the plumes had floated away from the crest of Marozzo and the steel helmet had rung with the stroke.

It must have been close to midnight when, as he turned the corner of the wall of the keep, he saw a slender shadow that trailed like a snake from an upper casement. He looked again, startled, and made sure that it was a rope of some sort which had just been lowered from the room of Tomaso!

HE found what the rope was by a touch—blankets cut into strips and twisted. And this fragile, uneven rope-end began to twitch and jerk suddenly. When he looked up, he saw a form sliding down the rope from the casement above.

Tizzo pulled the dagger from his belt and waited. He had that insane desire to laugh but he repressed it by grinding his teeth. Overhead, he heard a voice call out, dimly: "Tomaso! Hello—Tomaso!"

That call would not be answered, he knew, for poor Tomaso was sliding, as he thought, toward a new chance for liberty. There was courage, after all, in the pale, brown-eyed boy. There was an unexpected force in the creature in spite of the undue softness of voice, whether in speaking or singing.

He kept his teeth gripped and grasped the dagger a little more firmly, also. He would not use the point; a tap on the head with the hilt of the dagger would be enough to settle this case.

Above him, the calling became that not of Enrico but of the baron himself, who shouted: "Tomaso! Where are you?"

Then Baron Melrose was bawling out the window above: "Hai! He is there! He is almost to the ground. Enrico, waken every one! Down to the court or the prize will be gone. Run! Run! Our bird is on the wing!"

The descending form, casting itself loose from the rope as it heard this cry, dropped the short distance to the ground that remained—and the arm of Tizzo was instantly pinioning the figure.

Tomaso, with the silence of despair, writhed fiercely and vainly; the head went back and the wild eyes stared up into the face of Tizzo.

And suddenly Tizzo breathed out: "Lord!" and recoiled a step as though he had been stabbed. Tomaso for an instant leaned a hand against the wall—the other was pressed to his breast. That hand against the wall carried a glimmer of light in the form of a little needle-pointed poniard.

"Listen, Tizzo!" stammered the voice of Tomaso. "You're only with them by chance. You're not one of them. Save me—and my people will make you rich! Rich!"

"Damn the wealth!" groaned Tizzo. "Madam—how could I keep from guessing what you are?—madam, I am your servant—trust me—and run in the name of God!"

Overhead, there were rapid feet rushing on the stairs; and "Tomaso" ran like a deer beside Tizzo around the corner of the keep and toward the horses, which had been left in a corner of the yard to graze on the long grass which grew through the interstices of the pavement. Some of them were lying down, others still tore at the grass.

"Can you ride—without a saddle?" gasped Tizzo.

"Yes—yes!" cried the girl.

He was hardly before her at the horses. Two bridles he found, tossed one to her, and jerked the other over the head of the best of the animals, a good gray horse which the baron himself had ridden that day. When that was on, with the throatlatch unsecured, he saw the girl struggling to get the bit of the second bridle through the teeth of another horse. He took that work from her hands, finished it with a gesture, and then helped that lithe body to leap onto the back of the gray.

VOICES had burst out into the court, that of Enrico first of all. And he saw the forms running, shadowy in the starlight.

"Ride!" he called to the girl. "Ride! Ride!"

And as the gray horse began to gallop, Tizzo was on the back of the second bridled charger. The moment his knees pressed the rounded sides, he recognized one of the wheelhorses, the slowest of them all; and he groaned.

"What's there?" big Enrico was calling. "Who's there?"

"I!" he cried in answer. "Tizzo—and fighting for the lady."

It was too late for him to drive the horse through the gateway of the ruined courtyard; they were already on him, Enrico running first.

"The redheaded brat—cut him to pieces!" yelled Enrico. "The horses—get to horse and after her!"

And he aimed a long stroke at Tizzo, who caught it on his naked blade and returned a thrust that ran through the shoulder of the man. Enrico fell back, with a yell and a curse. Two more were coming; but in spite of its clumsy feet and bulky size, Tizzo had his horse in motion, now. He could hear the loud voice of the baron shouting orders as the heavy brute cantered through the gateway and then slithered and slid down the steep way outside, theatening to fall with a crash at every instant.

The girl was there—she was waiting just beyond the threshold of the first danger, crying out: "Are you hurt, Tizzo?"

She had heard the clashing of the swords, no doubt.

"Not touched!" he answered.

And they swept down the dangerous, bending way together. The huddled ruins of the town poured past them, like crouching figures ready to spring. They issued into the open country; and already the roar of pursuing hoofs sounded through the street of the village behind them.

Tizzo began to laugh. He sheathed his sword and waved his arm above his head. "We have won!" he shouted.

It seemed to him in the wildness of his happiness that he could pluck the brightness of the stars from the sky. But under him he felt the gallop of the carriage-horse already growing heavy. It would not endure. The poor brute was as sluggish as though running in mud fetlock-deep.

The girl had to rein in her light-footed gray to keep level with Tizzo.

"Go on!" he called to her. "This brute is as slow as an ox and they'll overtake it. But you're free. You've won. Ride for safety—go on!"

"If they find you, they'll kill you," cried the girl. "I won't leave you. If they catch you, Tizzo, I'll let them catch me, also!"

"They'd never spare me for your sake!" he shouted in answer. "Ride on!"

"I shall not!" came that clear voice in reply.

He drew the blundering horse closer to hers and leaned above her.

"I have started the work. Let me hope that it will be finished!" he exclaimed. "For God's sake and for mine, save yourself!"

As though to reinforce his words, the uproar of hoofs left the dull, echoing street of the village and poured more loudly across the open country.

"If they find you—" she protested.

But he laughed in that wild and happy voice. "They'll never find me. I have a lucky star—do you see there?—the golden one—it is favoring me now. Farewell! Tell me where to find you—and ride on!"

"Perugia!" she cried in answer. "You shall find me in Perugia. My name is—"

But here their horses thundered over the hollow of a bridge and the name was quite lost to him.

As they reached the roadway beyond, with loosed rein she was already flying before him, farther and farther in the lead; every stride that the fine gray gave carried her distinctly away from him. At the next bend of the road she was gone; and the flying hoofs from the village poured closer and closer behind Tizzo.

There was no use continuing on the back of that sluggard. He drew rein enough to make it safe to leap to the ground and then let the heavy blunderer canter on, diminishing speed at every jump, while the liquid jounced and squeaked audibly in its belly. Tizzo jumped behind a broken stone wall and lay still.

When the flight had passed him, he ran up to the top of the nearest hill, but the light was too dim for him to see anything. Only the noise of the galloping poured up to him from the darkness of the hollow, rang more loudly off the face of the opposite hill, and then dipped away and disappeared beyond.

Tizzo folded his arms and shook his head.

Ah, what a fool he had been not to see the truth before! Of course all of the others had known what she was. That was why their eyes had dwelt upon her in a certain way, following her hungrily. But he, Tizzo, had not known. And yet no matter what a fool he had been there remained in him an abiding resentment against the baron.

Neither was it all resentment, either. The heart of Tizzo poured out in admiration of that rash and valiant man who had set his single hand against such powers as those of the house of Marozzo. For with the name of Marozzo went that of Baglioni; the whole of Perugia was dominated by that noble family.

From Falcone, from Melrose, he had cut himself off. And if he went to Perugia—well, was it not likely that he would encounter the eyes of any one of the dozen men who had seen him with unvisored face in the battle of that day?

That did not matter. He knew that it was folly, but he also knew that nothing under a thunderstroke could keep him possibly from the town of Perugia.

She had made a handsome boy; she would be a gloriously beautiful woman. It seemed to Tizzo that there was nothing in the world he wanted so much as to hear, once more, her singing of that song which he had heard in the evening.

He walked down the hill, took the first road, and stepped along it at a brave pace toward distant Perugia.

IT was a day of heat and of showers; and the old beggar at last drew in under a projecting cornice which kept him dry. His withered face was full of both malice and patience, and his throat was sore from the whining pitch at which he had been singing out his appeals for mercy since that morning. He had in his purse enough to buy him a good cloak, and wine and meat and bread for half a month, but he was disappointed because he had not picked up enough for an entire month. Old Ugo, secure under the cornice, leaning on his staff, was about to step out into the street again in spite of a slight continuing of the rain, but here a sprightly young man with a sword at his side and his hat cocked jauntily at an angle paused suddenly beside him and said: "Father, have you lived a long time in Perugia?"

"I have existed here for a little course of years, some fifty or sixty," said Ugo.

"If I describe a lady to you, shall you be able to tell me her name?"

"Try me," said Ugo. "But first why not advertise your name?"

"Because she has never heard it."

"She has not heard your name—but she will be glad to see you?"

"I hope so—I pray so—I earnestly believe so," sighed the young Tizzo.

"Well," said the beggar, "this is like something out of an old story. Perhaps love at first sight, love in passing, a look between you—and now you are hunting for her around the world. Describe her to me."

"I describe to you," said Tizzo, "a girl of about nineteen or twenty. She has eyes that are brown and big—gold in the brown like sunlight through forest shadows—and a sweet, pretty, perfect, delightful face—about so wide across the brow and with a smile that dimples, do you hear—"

"I hear," said Ugo, smiling steeply down at the ground.

"A smile that dimples in the left cheek only. The left cheek, you understand?"

"Perfectly, signore."

"Are you laughing at me?"

"I? By no means, signore. I was simply remembering certain things. Old men cannot help remembering, you know. Tell me more about her."

"The top of her head comes to the bridge of my nose. Her nose, by the way, is not exactly a straight, ruled, stupid line. It is altered from that just a trifle. It is tipped up a shade at the end. Just at that slight angle which makes smiling most charming. Do you understand me?"

"Perfectly, signore."

"Her complexion," said Tizzo, frowning as he searched for the proper words, "is neither too pale nor too dark. A trifle pale now, because of a little trouble, but with radiance shining through. She is slightly made. Not thin, do you hear; slenderly made but rounded. In her step there is the lightness of a cat, the pride of a deer, the grace of a dancer."

"Ah?" said the beggar.

"Do you recognize her?" asked Tizzo.

"Almost!" said the beggar. "Tell me a little more."

And he kept on smiling down at the ground.

"Her voice," said Tizzo, "is singular. Of a million ladies, or of a million angels, there is not one who can speak like her. And when she sings, the heart of a man grows big with joy and floats like a bubble. Do you hear? Like a golden bubble!"

"I hear you," said the beggar.

"Her hands," said Tizzo, "are small but not weak. They are hands which could rein a horse as well as use a needle."

"Ah?" said the beggar.

"And—I forgot—on her face, below the right eye, there is a little mark—not a blemish, you see—but a small spot of black; as though God would not give to the world absolute perfection or, rather, as though He would place a signature upon her; or as though through one fault he would make the rest of her beauty to shine more brightly. Am I clear?"

Ugo, the beggar, looked suddenly into the distance, squinting his eyes.

"Ah ha! You know her!" said Tizzo.

"I am trying to think. I shall go to see, signore. I shall go to a certain house and make sure. And then where shall I find you?"

"At that inn down the street. The one which carries the sign of the stag. I shall be there."

"Within a little while, I shall be with you, signore, and tell you yes or no."

"What is your name?"

"I am called Ugo, signore."

"Look, Ugo. You see this emerald which is set into the hilt of my dagger?"

"I see it very clearly. It is a beautiful stone."

"I swear to God that if you bring me to the lady, you shall have this stone for your own."

A faint groan of hungry desire burst from the lips of Ugo. In fact, he seemed about to speak more words but controlled himself with an effort.

"At the Sign of the Golden Stag—within an hour, I hope, signore."

And Ugo turned and strode up the street like a young man, because it seemed to him that, when he saw the emerald, he had looked into a green deeper than the blue peace of Heaven.

He continued on his way until he came to a great house where many horses were tethered and where there was a huge bustling from the court. Into this he made his way and said to the tall porter at the door: "My friend, carry word that Ugo, the beggar, has important word for Messer Astorre. It is a thing that I dare not speak in the streets or to any ear except to that of Messer Astorre himself."

Then he added, "Or to my lord, Giovanpaolo."

At this second name the porter stopped his smiling.

"Messer Astorre," he said, "is engaged in talk with an important man. If I break in upon him, I must give some excuse."

"It shall be this," said Ugo. "Tell him that there is a beggar who is not a fool or crazy, but who dares to demand immediately to speak to him."

The porter hesitated, but the eye of the old man was burning with such a light that after a moment he was told to wait at the door while the porter went to announce him.

This was the way in which Ugo, after a time, passed through a door of inlaid wood and came into a room lighted by two deep windows, in one of which sat the famous warrior whose name at that time was celebrated throughout Italy—the great Astorre Baglioni. First the beggar glanced hesitantly and covetously all about him at the rich hangings which covered the walls of the room and then toward a pair of magnificent paintings done in the gay Venetian style. Afterwards he approached the noble Astorre, bowing profoundly and repeatedly.

"Your name is Ugo," said Messer Astorre, "and you have something to say to me?"

The second man in the room, a tall, darkly handsome fellow who had been striding around in an excited manner, shrugged his shoulders and looked out the window as though he could hardly endure the interruption.

"What I have to say is for the ear of my lord alone," said Ugo.

"Whatever is fit for me is proper for my friend, Mateo Marozzo, to hear," said the warrior.

"Messer Astorre," said Ugo, "it is a thing that concerns your sister, the Lady Beatrice, I believe."

Mateo Marozzo whirled about suddenly, with an exclamation and Ugo shrank a little.

"Be quiet, Mateo," said Astorre. "Don't frighten the man."

"The word was," said Ugo, "that the noble lady your sister was gone from the town, stolen away from it by thieves hired by some of the cursed house of the Oddi. But this very day a young man spoke to me in the street, described her, and offered me a jewel if I could find her for him."

"So?" said Astorre, smiling. Then he added: "My sister has been returned safely to the town. Who is this man who asked for her?"

"I do not know his name, my lord. He is a young man with red hair and eyes of a blue that shines like the blade of a fine sword, or like the blue underpart of a flame."

"Astorre!" Mateo called. "It is the man! It is the man! Give him to me!"

"Well, no doubt you shall have him if you want," said Astorre. "But who is he?"

"He is called Tizzo. I heard his name called out in the fight. He is the Firebrand. And it was he who knocked the wits out of my head with a lucky stroke of his battle-ax."

"Ah?" exclaimed Astorre. "Have the Oddi become so bold as this? Are they sending their agents like this into the middle of Perugia? Are they searching for Beatrice to steal her from us again? By God, Mateo, if we can catch this fellow, you shall have him. And if you don't tear out of him some information about the Oddi plans, call me a fool and a liar! My friend, where is this fellow?"

"At the Sign of the Golden Stag," said Ugo, beginning to tremble in body and voice as he realized that he had struck upon great news indeed.

"He is yours," said Astorre to Marozzo. "Go take him and do what you will with him."

AT the Sign of the Golden Stag a man whose face was roughed over with beard to the eyes was talking loudly in the big taproom. He had on a long yellow coat and pointed shoes of red; and he walked back and forth a little through the room, while all eyes followed him. The afternoon had grown so dark with rain that lamps had been lighted in the room and these cast an uncertain and wavering light. Tizzo followed the movements of the tall stranger with interest because he found the voice vaguely familiar, but not the face. He was wondering where he could have seen before that shaggy front; and in the meantime he sipped some of the cool white wine of Orvieto and listened to the stranger's talk. The beggar, Ugo, surely would soon return.

The man of the yellow coat was a doctor, it appeared, and he was peddling in the taproom some of his cures; for instance—"A powder made of the wing cases of the golden rose chafer, an excellent thing for cases of rheumatism. Let the sick man put four large pinches of this powder into a glass of wine and swallow off the draught when he goes to bed at night. The taste will not be good but what is bad for the belly is good for the bones." Or again the doctor was saying: "When old men find themselves feeble, their eyes watering, their joints creaking, their breathing short, their sleep long, I have here an excellent remedy. In this packet there is a brown powder and it is no less than the dried gall of an Indian elephant, which carried six generations of the family of a Maharajah on its back for two hundred years. And then it died not of old age but fighting bravely in battle. Now the merit, relish, and the source of an elephant's long life lies in its gall; and in this powder there is strength to make the old young again, and to make the middle-aged laugh, and to make the young dance on the tips of their toes."

Continuing his walk and his narration of wonders, the doctor happened to drop one of his many little packages on the floor beside the chair where Tizzo was sitting. And as he leaned to pick up the fallen thing he muttered words which reached Tizzo's ears only.

"Up, you madman! Away with me. Your face is known in Perugia and every moment you remain here is at the peril of your life."

The doctor, saying this, straightened again and allowed Tizzo to have a glimpse of flame-blue eyes which he remembered even better than he had remembered the voice.

It was the baron of Melrose who had come into the city of his enemies in this effective disguise. Was he risking his life only for the sake of plucking Tizzo out of the danger? The heart of Tizzo leaped with surprise and a strange pleasure. A moment later he stepped into a small adjoining room which had not yet been lighted. He had been there hardly a moment before the doctor entered behind him. He gripped Tizzo by the arm, exclaiming in a quick, muffled voice: "Go before me through the court and down the street toward the northern gate of the town. There I shall join you."

"I cannot go, my lord," said Tizzo. "I must wait here to learn—"

"You must do as I command you," exclaimed Melrose. "You have given me the pledge of your honor to serve me; we have made a compact and have shaken hands on it."

"I shall serve out the terms of the contract," said Tizzo. "I swear that I shall hunt you out tomorrow, but today I have to find the lady."

"What lady?" asked Melrose.

"That same Tomaso.'"

"You betrayed me, Tizzo," said the baron, angrily.

"It is true," answered Tizzo, "and I shall betray you again if you give me the work of harrying poor girls across the country, robbing them from their homes, leaving their people—"

"Hush!" said Melrose. "Tell me—when did you know that Tomaso was a woman?"

"When I grappled with her at the moment she dropped to the ground."

"Not until then?"

"No."

"I understand," said the baron, "and any lad of a good, high spirit might have done exactly as you did, Tomaso turned into a lady in distress and the gallant Tizzo sprang to her rescue—but if I had overtaken you that night—well, let it go. She told you her name?"

"No," said Tizzo.

"But you came here into Perugia because she herself invited you!"

"I was to find her in Perugia, but I could not hear the name she called to me. The horses drowned it, thundering over a bridge."

"You came into this big city to hunt for her face? Are you mad, Tizzo?"

"I think I am about to see her," answered Tizzo. "I was able to describe her—"

"My lad," said Melrose, "if you try to reach her, you'll be caught and thrown to wild beasts. She is the Lady—"

But here a voice called from the lighted taproom, loudly: "He was in here. He was seen to enter in here. A young man with blue eyes and red hair. A treacherous murderer; a hired sword of the Oddi. Find him living or find him dead, I have gold in my purse for the lucky man who will oblige me!"

Tizzo, springing to the door, glanced out into the taproom and saw a tall, dark, handsome young man in complete body armor with a steel hat on his head and a sword naked in his hand. Behind him moved a troop of a full dozen armed men. They came clanking through the taproom, looking into every face.

"That's Mateo Marozzo," said Melrose, "the same fellow you bumped on the head yesterday. Run for your life, Tizzo. Try from that window which opens on the street; I'll make an outcry to pretend that you've escaped into the court on the other side."

"My lord," said Tizzo, "for risking your life to search for me—"

"Be still—away! At the northern gate as fast as you can get there—hurry, Tizzo!"

Tizzo jumped into the casement of the window at the right and looked down into the rainy dimness of the street. One or two people were in sight; and the drop to the ground was a good fifteen feet. He slipped out, and he was hanging by his hands when he heard the loud voice of Melrose shouting inside the room: "This way! A thief! A redheaded thief! He has jumped down into the court—"

There came a trampling rush of armed heels, a muttering of eager voices. And Tizzo loosed his hold and fell. He landed lightly on his feet, pitched forward upon his hands, and then sprang up, unhurt. But from the entrance gate that led into the court of the tavern he heard a voice bawl: "There! That is he Messer Mateo wants. Quick! Quick! There is a golden price on his head!"

It was the old beggar, Ugo, who fairly danced with excited eagerness as he pointed out Tizzo to a number of loiterers about the gate.

The whole process of betrayal was evident now. One glance Tizzo cast up toward the high towers of Perugia, now melting into the blowing, rainy sky, and in his heart he cursed the pride of the town. But they were coming at him from the direction of the gate; and other yelling voices of the hunt issued from the tavern into the open of its court. They would be on the trail in another moment. He turned and ran with all his might, blindly.

It was clumsy work. He had to hold up the scabbard and sword in his left hand to keep it from tripping him; the steel breastplate which he wore under his doublet was a weight to impede him; but he held fairly even with the foremost of the pursuit until he heard the clangor of hoofs on the pavement, and he looked back to see mounted men behind, and one of them in the lead with three flowing plumes in his hat.

That would be Mateo Marozzo, of course!

He could not outrun horses, but he might dodge them for a moment, so he turned sharply to the left down a dark and narrow lane.

It was a winding way, as empty of people as it was of light, and when he turned the first corner he saw that he was trapped, for the foot of the lane was blocked straight across by a great building.

All other doors were blocked except to the right, where two figures in black hoods stood as if on guard, one of them constantly ringing a little bell. They made an ominous picture, and inside the open door of the house there was a yawning, a cavernous darkness. But Tizzo sprang straight toward this added moment of safety. In front of him, he saw the dark forms lift and stretch out their arms.

"Halt!" cried one deep voice. "Better to die in the open under a clean sky; death itself is waiting inside this house."

But Tizzo already had brushed past the restraining hands. He entered the dimness of a long hall with the ringing hoofbeats coming to a pause in front of the entrance to the place. And he heard a long cry from the street that might be triumph, horror—he could not tell what.