RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

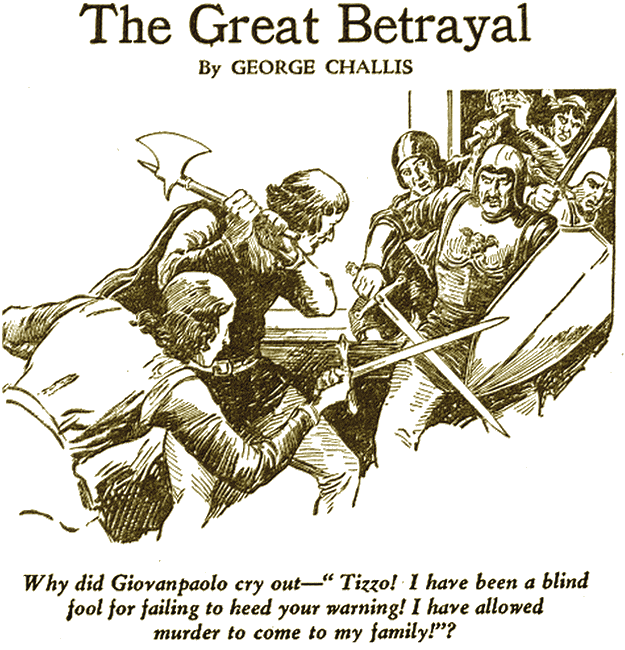

Argosy, February 2, 1935, with first part of "The Great Betrayal"

Tizzo, young adventurer and expert swordsman,

slashes his was through plot and intrigue in old Perugia.

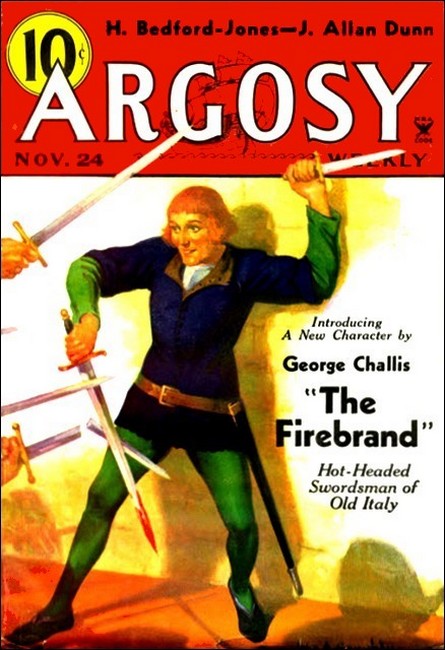

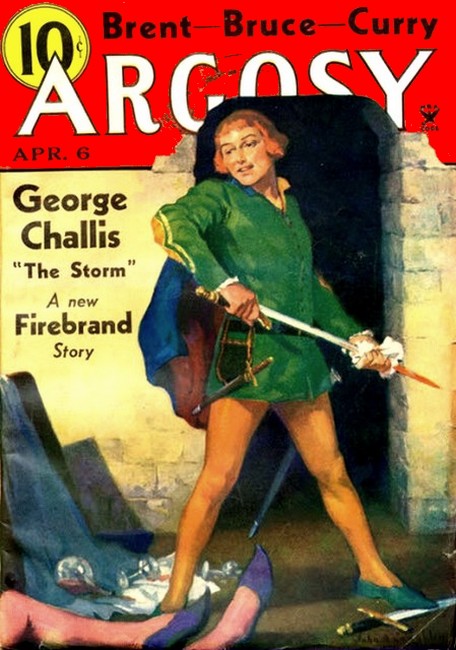

In 1934-1935 Max Brand, writing under the name of "George Challis" penned a series of seven swashbuckling historical romances set in 16th-century Italy. These tales all featured a character, Tizzo, a master swordsman, nicknamed "Firebrand" because of his flaming red hair and flame-blue eyes, and were first published in Argosy.

The original titles and publication dates of the romances are:

1. The Firebrand, Nov 24 and Dec 1 (2 part serial)

2. The Great Betrayal, Feb 2-16, 1935 (3 part serial)

3. The Storm, Apr 6-20, 1935 (3 part serial)

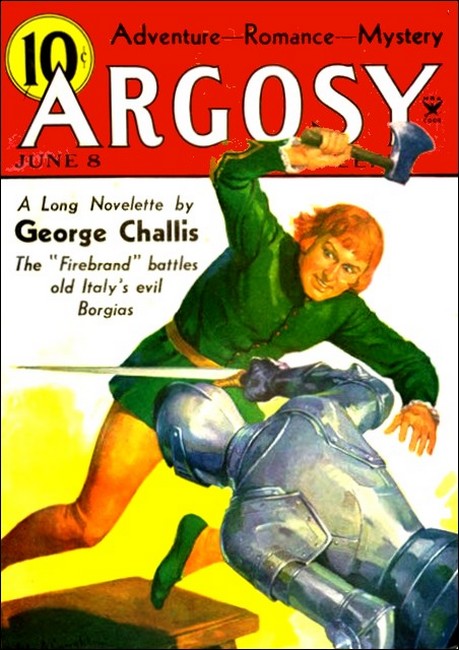

4. The Cat and the Perfume Jun 8, 1935 (novelette)

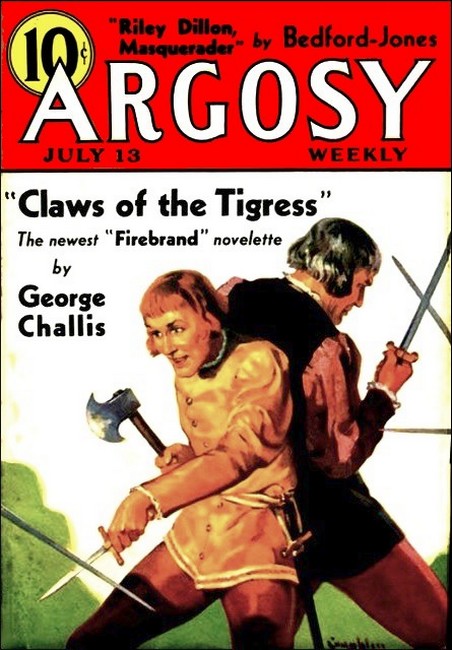

5. Claws of the Tigress, Jul 13, 1935 (novelette)

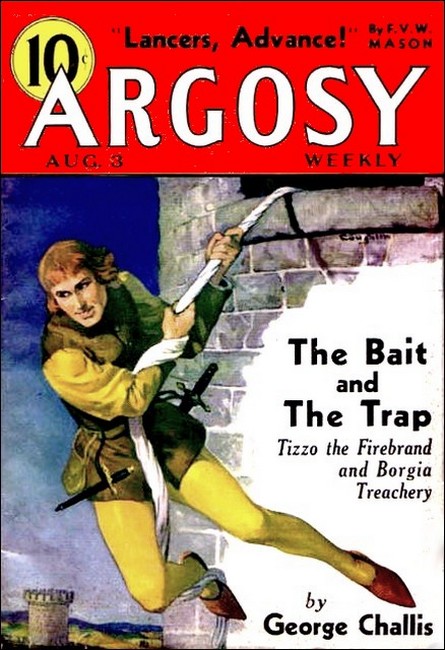

6. The Bait and the Trap, Aug 3, 1935 novelette

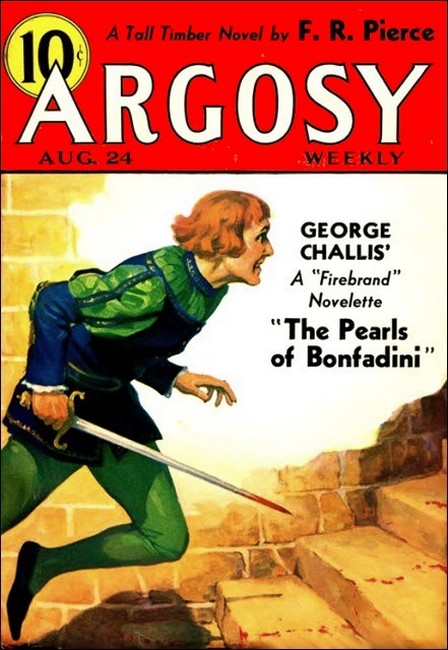

7. The Pearls of Bonfadini, Aug 24, 1935 (novelette)

The digital edition of The Great Betrayal offered here includes a bonus section with a gallery of the covers of the issues of Argosy in which the seven romances first appeared. —Roy Glashan, December 2019.

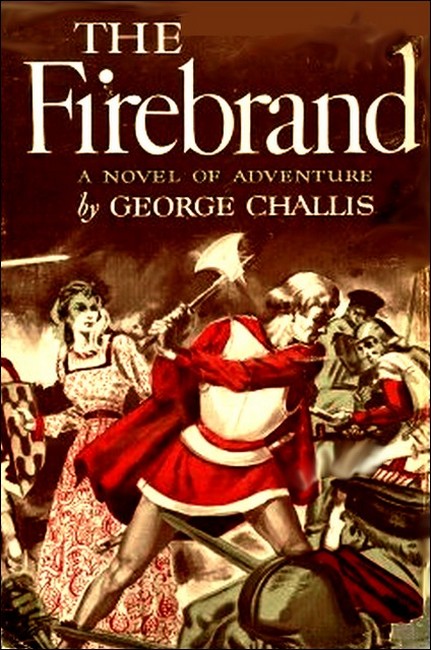

"The Firebrand," Harper & Brothers, New York, 1950

Tizzo turned quickly after striking the man down with his

sword. Infuriated, they charged all the more fiercely.

TO the credit of Tizzo there stood a number of things for a man who was not much past twenty and who had no more family than a rabbit in the fields.

Item: Five duels with the best blades of the town of Perugia, in all of which he was the conqueror, through luck and a certain nameless cunning of the hand none had resulted fatally.

Item: The great favor of Messers Astorre and Giovanpaolo, war lords and battle-leaders of the powerful and ruling house of the Baglioni.

Item: A purse filled either by his patrons, the Baglioni, or by clearheaded gambling, or by the wealth of his foster-father, Luigi Falcone; a purse worn out by these emptyings and fillings.

Item: Handsome lodgings in the inn.

Item: A one-eyed cut-throat with a patch on his face, a leering smile, and the cunning of the devil, named Elia and devoted to the service of Master Tizzo.

Item: A head of hair which, being cut short to accommodate a helmet; looked a little less burning red than in younger days when it had gained him the name of Tizzo, the Spark.

Item: Eyes the color of the blue of flame.

Item: An engagement to meet this night, under the moon, in the summer house of the country estate of Astorre Baglioni outside the city, the beautiful sister of Messer Astorre, the Lady Beatrice.

Of all of these articles in his favor, young Tizzo was

most burningly aware. For the blue flame of his eyes showed him

one who was enjoying the full savor of life to the very roots of

his palate. He was this evening dressing with care, helped busily

by Elia Bigi. He had drawn on long purple hose, a green doublet

heavily embroidered with crimson, green shoes of soft leather

that came half way up the calf of his leg; he had belted on his

sword which was balanced at the right hip by a dagger. Scabbard

of both sword and dagger were enhanced by rich golden chasings.

Over his neck he hung a chain of massive gold, each link

variously and curiously worked by a Florentine goldsmith, and

supporting an intaglio which showed the noble profile of the

famous Giovanpaolo, that Achilles of the condottieri of

Italy. He was now swinging over his shoulders a black cloak which

shone with an elaborate arabesqueing in silver when a messenger

came to the door with a letter.

When Elia gave him the letter, he was about to throw it aside, but his eye saw the arms of the Bardi stamped into the seal and therefore he knew that it was a missive from his dearest friend in the entire city. So he opened the letter and read:

To my brother Tizzo, given in haste from my house; greetings, life, happiness, honor.

Tizzo, go not where you have willed to go on this night. Let your heart sleep. Do not follow it.

Ask me no more for my meaning or for the source of my information.

If I were free to come to you, I would be with you now and beg you on my bended knees to stay at home.

If ever you entered my house like a brave angel from heaven; if ever you saved me from a foul death beyond the holy hand of the church, alone, desperate, hateful to men; if ever I have sworn to you the eternal love of a brother for a brother, believe me now, ask me nothing, and lie quietly in your chamber tonight. It is your time of danger. If it passes, tomorrow will dawn brightly and the rest of your life may be spent in peace.

Farewell. My heart burns with anxiety. Be wise. Be prudent.

With all the blood of my body, thine,—

Antonio.

When Tizzo had finished the reading, he was so

overwhelmed that he threw himself into a chair and bowed his

head.

Elia, that hardy brigand, muttered: "You have lost a good legacy, at least. But take a glass of wine and lift your head again. There are still throats to be cut and purses to be taken in this jolly old world."

As he spoke, he poured from a silvered pitcher a goblet of the rich, thick red wine of Tuscany and held out the glass to Tizzo, who took it, tasted it, and pushed it back into the hand of his servant.

"Or if it is merely a woman," said Elia, "I can swear that there are others who—"

"Be silent!" commanded Tizzo.

He rose and paced the room, thinking aloud.

"He begs me as he loves me.—True, Antonio loves me. 'Go not where you have willed to go on this night.'—How should he know where I am to go this night? Beatrice, my beautiful, noble, glorious, generous, brave, gracious, most perfect Beatrice!—Let my heart sleep? How can I let it sleep when it strides like a lion through my body?—Ask not for his source of information, which means that he has it from a high and dangerous authority.—This is my time of danger? No, by God, it is my time of love!—If this night passes in safety—by the Lord, poor Antonio has been visiting an astrologer. Elia!"

"Messer Tizzo?"

"Do you believe in astrology?"

"Well," said Elia, "the sky is a large, clean page, and it would be a pity if God had not put some good writing on it, for wise men to read."

"True!" said Tizzo.

HE went to the window and thrust it open to look up past the

nearest battlemented heights and into the brightness of the

heavens. A wind which never touched the earth made the stars

tremble like leaves. Awe fell upon the irreverent soul of

Tizzo.

He murmured: "But how could God waste his time to arrange symbols in the high heavens concerning the life of Tizzo?"

"Sparks in heaven to speak of a spark on earth," said Elia. "How could the stars be better employed than to speak to you, master?"

"I shall remain at home."

"The will of God be done," said Elia, grinning behind his master's back, because he was sure that this safe impulse would not be followed.

It happened that, at this moment, a sound of music turned a distant corner, the tremor of strings, singing, and the mingled laughter of women. Tizzo threw up his hands.

"I am called!" he said. "And I must go. 'Is my horse ready?"

"It is, Messer Tizzo."

"Not the mule-headed bay for carrying an armored man, but the chestnut Barb that flies?"

"The Barb is saddled. The silver bridle is on him and the yellow housings with the bells."

"Bells?" said Tizzo. "Well, if they are waiting for me, let them hear me come! But give me that hat with the steel lining."

"And the breastplate of Spanish mail?" queried Elia.

"Yes. Let me have it.—No, I shall not take it.—What manner of man would I be, Elia, if I feared to die? Love of her is my armor. Arrows will turn from me tonight."

"I would put my money on a good cross-bow bolt," said Elia, "or more still on a knife-thrust aimed at the back, or perhaps a little in a few dozen tiles, dropped from an overhanging roof."

Tizzo, staring for a moment at his servant, suddenly broke out of the room and ran hastily down the stairs. In the courtyard he found the slender chestnut Barb standing, a gift from the richest of all the Baglioni, that Gridone who was the most fortunate of men, married to the loveliest of ladies, with the whole world of happiness already in his hands, as it seemed. The occasion of the gift hung now beside the saddle in a case of embossed leather, a common woodsman's axe. The deceptively slender frame of Tizzo had seemed incapable of great efforts and yet with that axe he had cloven the massive jousting helmet, the finest product of the Milanese armorers. It had been put on a horse-post and he had split it from top to bottom with that deft, quick swing which he had learned from Falcone's foresters in his boyhood. The reward had been a loud exclamation that ran all the rounds of Perugia—and this beautiful Barb mare which now put out her lovely head and whinnied for her new master.

Once in the saddle, he flew the mare down the crooked, winding, paved streets of Perugia until the dark and massive arch of a city gate appeared before him.

"Open! Open!" he shouted, as he came up.

The captain of the gate stepped into his path, a tall man in complete armor except for the head, which was shaven close and gray with premature age.

"Are you drunk or a fool?" he asked bluntly, for the soldiers of the Baglioni were at ease in their manners to the townsfolk. "It is my duty to open the gate to every young hot-head who wishes to take the country air at night?"

"Does this help you, captain?" asked Tizzo, thrusting out a hand on which appeared a ring with a large incised emerald on it.

The captain, regarding the design with a bowed head, stepped back and frowned.

"The ring may be stolen, for all I know," he said.

Tizzo snatched off his hat.

"Do you know me better now?" he exclaimed.

The captain saluted instantly. "Messer Tizzo!" he said. "The light is dim; I could not see your face; forgive me!"

He ordered the small portal to be unlocked and it was done at once.

"Give me fortune, my captain," said Tizzo.

The captain of the gate laughed. "If I don't give it to you, you'll take it anyway. I give you fortune, Messer Tizzo. May she be the daughter of the richest merchant in Perugia!"

THE last exclamation came as Tizzo leaped the Barb through the

barely opened portal and let the mare speed away down the slope.

He crossed the hollow at the same wild gallop, but let the mare

draw down to a trot as he climbed into the hills again. To the

right he saw the misty lights of the city of Assissi, the sacred

place of pilgrimage, but those lights meant no more to Tizzo, on

this night, than the distant stars of the sky. It was the face of

Beatrice Baglioni that filled his mind, it was her remembered

voice that silenced the hoofbeats of the mare as he drew near the

high, dark shoulders of a great villa.

He did not go directly to the big house, but tethering the mare at a short distance from the corner of the stone wall, he climbed that wall like a cat, and dropped lightly down inside it.

Already he was well inside a realm of danger. It was true that he was a chosen friend and supporter of both Astorre and Giovanpaolo Baglioni, but the armed guards they maintained were apt to strike an intruder dead before they looked into his face or asked for his name. Besides, no matter how they valued him, they could not be expected to smile on a romance between him and their own sister, a lady rich enough and famous enough in name and in beauty to marry a prince of a great estate. The Baglioni were, he knew, generous, brave and true to their friends; but they were also ruthless in matters of important policy.

These things softened his step as he stole from place to place through the garden, dropping flat on the grass when he heard the jingling of steel and staying under the shadowed lee of a hedge until three men went by, the moonlight glinting on their armor.

But he went on again until he saw, in the midst of a silver sheen of lawn covered by the moonlight as with dew, the little summer-house which was the jewel of the garden. About it, statues stood at the corners of the hedges, dancing figures that seemed to move in this light.

And the fragrances of the garden flowers came as intimately as voices to the heart of Tizzo.

There was almost infinite peril about him, but to him it was the spice in the wine, the savor in the breath of life. He would not have altered anything.

When he looked up, he took note of the position of the moon and saw that it still lacked perhaps half of an hour of the position in the sky on which he had agreed with Beatrice. But now she was filling her heart with expectancy in the great villa. That was her room, there at the upper corner of the building—that one with the two lighted windows.

Yes, she was there, preparing to steal from the house.

And now she must be coming down the little winding steps which were cut into the wall. She would wear a dark cloak to hide her beauty and defy the moon. Slipping over the lawns like a shadow, she would enter the summer-house and then he would see, from his place of covert at the hedge above, the signal which they had agreed upon: the triple passing of a light across the face of a window.

He had to sit down on the grass and bow his head in his hands and tell himself stories of his past to make the time pass. When he looked up, the moon was already at the proper place in the sky. The moment had come!

But no signal flashed for him! He waited with a sudden coldness of the heart.

Strange things are done by the great to the humble. What if she had been playing with him? What if she had named the hour for him and, afterwards, had told the story to her maids, laughing pleasantly, wondering how long in the chill of the night the poor red-headed fool would wait in vain?

The window of the summer-house which faced him was, to be sure, unshuttered; but perhaps it was habitually left open to the cool of the night.

Impatience suddenly overwhelmed him, swept him away. He ran swiftly as the shadow of a stooping hawk across the lawn and peered in through the window. The moonlight made a slant path before him, and in the midst of it he saw nothing except a chair which lay on its side.

He was through the window instantly.

The air within was warmer, softer, and a perfume breathed in it that sent an ecstasy through his brain, for it was that fragrance which his lady preferred, he knew. That one chair overturned—that sparkling eye—he leaned and picked from the floor a small ring set with diamonds and knew it for one of the jewels of the Lady Beatrice. At the same time shadows moved softly from the dark corners of the room; he saw them by instinct rather than with his eyes.

AS full awareness leaped into the mind of Tizzo, he heard a voice more hateful to his ears than any other in the world, the young Mateo Marozzo crying: "Now! Keep him from the window! Now! Now!"

And those shadows were lunging from the corners of the room with a sudden thundering of feet.

This was the danger of which Antonio Bardi had warned him, faithfully. He heard the peculiar grating, clanging noise of the steel plates of armor; he saw the sheen of naked weapons already sweeping past the open window behind him.

There was no refuge in that direction. And since he could see no means of flight he followed the first impulse of a very brave man: with his sword swinging he leaped straight into the face of danger and charged the men immediately before him.

Their own numbers clogged their efforts. Two blades struck at him almost in the same instant. He caught one with the sword, one with the dagger, and burst straight through the fighting men. There was a door before him, barely ajar. Through it he leaped as a hand grappled his cloak and a sword smote the ledge of the doorway above his head. That assailant he heard crying out in the voice of Marozzo, once more.

He turned and struck the man to the floor with the pommel of his sword. Those others, recovering from their confusion, had turned to follow at his heels but he slammed the door and shot home the bolt. By the moonlight he saw a point of steel struck straight through the heavy wood and heard the impact of armored shoulders against the barrier.

It held firm and he turned to the senseless form on the floor. By the hair of the head he raised Marozzo and laid the back of the man's neck across his knee.

"Take the rear way; cut him off; a thousand florins for him!" he could hear voices shouting.

But with the point of his dagger, with cruel deliberation, he cut a cross in the forehead of Marozzo. The point of the keen weapon shuddered against the bone, so strong was the pressure. And the blood looked black as it flowed down the face of Marozzo.

He, wakening with a groan, heard the voice of Tizzo saying: "Where is the lady? Marozzo, here is your death waiting in my hand if you lie; but you live if you tell the truth."

"The convent of the Clares!" groaned Marozzo.

Tizzo flung the helpless body from him and sprang up. A fellow with an axe was smashing in the outer door to this room and there was a clamor of many voices near him. So Tizzo drew back again the bolt which he had just shot and leaped back into the first room.

Two soldiers were still in the place, but totally unprepared for this sally, and Tizzo leaped through the window and raced over the gentle slope of the lawn.

They were hopelessly lost behind him, in a moment, those fellows in the anchoring weight of their armor. He leaped the first hedge, gained the wall, and was over it and in the saddle of the Barb, while the clamor still poured aimlessly towards him from the distance.

The swift mare carried him from all danger, now, like a leaf in a strong wind.

And still, as he looked up, he saw the same moon which had promised him happiness sliding over the wide arch of the night and tossing a meager drift of clouds into shining spray.

But in an hour the entire prospect of his life had changed. He had been the friend of the Baglioni; what was he to them now? The red hair which had been his passport through the city gate might be his death-warrant now. And Lady Beatrice was closed inside the icy walls of a convent until it pleased her lordly brothers to set her free!

HE could not cast forward to any conclusion; the speed of the

mare had brought him back to the same gate of the city before

anything was settled in his mind; he was knocking again at the

portal with an instinctive hand, and he heard a voice calling

through the shot-window: "Who is there?"

"I've come through this way once before, tonight," said Tizzo.

"Ah, it is-he!" Tizzo heard a quieter voice mutter before the hole in the gate.

The middle door was opened at once, and he saw that same tall captain approaching, now with a naked sword in his hand and a helmet on his head.

"Messer Tizzo," said the captain, with a certain happy unction, "I arrest you in the name—"

"Of my foot!" cried Tizzo, and driving a spur into the side of the Barb, he made her bound like a deer while he drove the heel of his other foot straight into the face of the captain.

"Cross-bows! Cross-bows!" shouted the captain in a muffled voice as he staggered and fell.

The cross-bows were quickly at the shoulder, but before a single quarrel could fly, the Barb had rounded the corner of the first building and was raising loud echoes down the narrows of the street.

So Tizzo came back into Perugia easily enough, but would he find it such a simple matter to get out again? If he were wanted, he probably would be caught, because the Baglioni knew how to turn their city into a bird net which was capable of catching even the swiftest hawk in the highest sky.

But here he was riding on the street which contained the convent of the gentle order of the Clares, that sisterhood which followed the mind of St. Francis. But however good their lives and sweet their ways, the gray of their habits was not so gloomy as the bitterness in the mind of Tizzo. The gray gowns seemed to Tizzo to have claimed his lady, and she was shut away from him already as though by the veil of twenty years.

And now he sat the Barb under the lofty wall of the convent, staring hopelessly up at the barred casements. Somewhere inside the building a bell was striking, as though to hurry penitents to their prayers. The knees of Tizzo weakened, also. He would have been glad to throw himself down on the pavement of the street and to ask God for mercy in the midst of his wretchedness.

It was now that a figure detached itself from the arched shadows near the door of the building and came slowly across the street towards him, a ragged beggar, walking with a staff. When he came closer, he lifted his tattered hat.

"Messer Tizzo?" he asked, humbly. "Well?" demanded Tizzo.

"This is for your hand, signore." And he handed to Tizzo a letter from which there came the slightest scent of perfume, a fragrance more grateful to Tizzo than all the music of the spheres.

He ripped open the letter and read the writing by the dim moonlight.

Tizzo, we are betrayed. Astorre is wild with rage. Even Giovanpaolo has struck his hand on his sword and sworn an oath.

A wretched woman of my own household has told everything. I shall spend my days kneeling, praying for your life. Fly, Tizzo, fly! My love follows you.

Beatrice.

THE gift of a florin made the beggar begin to bless Tizzo and all his ancestors.

"I don't know their names," said Tizzo harshly, interrupting the long benediction, "so keep your prayers for your own spindleshanks."

Out of the letter came two great facts: that his lady loved him, which lifted earth to heaven and spread blue fields of eternal happiness before him; and that Giovanpaolo had struck his sword hilt with rage—which swept all of this happiness out of existence again.

He could see them together, the Lady Beatrice and the noble face of Giovanpaolo. Only long continued wars had taught him the vice of cruelty, but his heart was as glorious as his face. Of that Tizzo was sure.

He could wish, now, to have the council of the boldest man he had ever known, that famous English warrior, Henry, the Baron of Melrose. What would the baron have advised in a time like this? Why, his counsel would have been to strike at the root of the fire in order to put out the flames. And Giovanpaolo was the root of the danger, of course. Astorre mattered less because one word from his famous brother would rule him.

Tizzo sat his saddle musing through a long moment until he heard the clanking of armor down the street and saw the dim swinging light of a lantern approaching. Then he turned the head of the Barb mare and rode on the wildest errand he had ever attempts in all his wild life.

Danger came to him from the Baglioni. The innermost brain as well a the strongest striking hand of the Baglioni was Giovanpaolo. Therefore he intended to go straight to that man o; many devices.

Giovanpaolo, he knew, was spending the night at the house of his cousin Grifone, in order to discuss with him late and early, the plans for the reception of Astorre's wife, who was to arrive the next day from Naples. The whole city was to be given over to a great fiesta in honor of the newly married pair and already the preparations were making the town hum day and night.

Towards the house of Grifone he went, therefore, and rode his horse slowly past the great façade. At all the corners of it were posted small groups of men-at-arms to keep watch, for the Baglioni were masters of the city, though Perugia was full of danger to them. The exiled house of the Oddi still retained a great number of adherents within the walls and these were likely to strike whenever the opportunity was good. What bait more tempting than to find within the walls of one house both the richest and the wisest of the Baglioni?

Since it was obvious that he would not be able to enter the house through one of the lower windows, he determined to take the place in the rear. So he went to the next lane, left the good mare tethered in it, and looked up the gloomy height of the side wall of that house which adjoined Grifone's.

He took off his hat to have the weight of the steel lining from his head. He put away the heavy cloak, also. In doublet, hose, and the soft green leather shoes he prepared to climb, but first he hung his sword by its shortened belt from around his neck. So lightened he went up the side of the house with ease. As a cat climbs, at home in the branches, swift-footed and confident, so he ran up the window bars which were like ladders, clawed his way over the great projecting ledges, and came at last to the high cornice, which thrust well out from the wall of the building. Balanced on a mere edging of stonework that girdled the house, he looked up to study this hazard, and made sure that he could hardly hope to surmount the barrier. Then he saw a projecting coping stone on which he might be able to fasten, but it was well beyond his reach.

He slipped off his sword and stretching out his arm, hooked the belt over the stone. As well as he was able, he tested the strength of this anchorage; he looked to the fastening which, except in time of action, held the sword blade to the sheath.

However, he was a fellow who usually found the first thought better than the second. In another moment, setting his teeth, he grasped the sword blade and allowed himself to swing out from the wall of the building. Above him, he felt the belt slide on the stone and made sure that he would drop the next instant into thin air.

That was why he looked down and saw in the street, made narrow by the height at which he hung, two lanterns and a dozen men gathered about his mare.

Would they glance up and find that dim, small object dangling under the great eaves of the house?

THE belt no longer slipped. It had stuck precariously, at the

very end of the projecting stone, and Tizzo pulled himself up

gingerly, hand over hand, until he could grasp the stone itself.

Then, in a moment, he had swung himself onto the steep slant of

the roof, gathering the sword up after him.

Lying flat, he peered down and made out the mare being led away, while one lantern went swaying down the street and another was hurried up its length. For all he knew, they might well have seen him above their heads and they were now going to spread the alarm. Nevertheless he went forward.

That moon which had appeared to him like a bright face of promise earlier in the night was now sloping into the west and the stars were wheeling slowly after it. He gave them one glance and then crossed the roof to its farther side. The roof of the great house of Grifone Baglioni began here, with hardly a ten foot gap between the two cornices.

He bounded across that chasm quickly and nimbly.

A flat roof-garden stood in the center of the space with a door leading downwards. The door was locked, but the bolt was so flimsy that it gave at once to the pressure of his shoulder, and so he passed down into the house of Grifone. Past the upper corridor, he went down to the second hall and through this to the end because he knew perfectly where Giovanpaolo would be lodged. It was not the first time that Tizzo had been in this palace and he knew that the suite of honor adjoined a fine open loggia which overlooked the piazza. Here he expected to find Giovanpaolo.

It was said that the house of Grifone was painted from top to bottom and, except for the servants' quarters above, this was entirely true. A night-lamp, hanging from the ceiling of the hall showed him the walls moving with a great procession of figures and even the ceiling itself, of coffered wood, was painted and gilded so that it shone over his head like a bright autumn forest.

In a niche at the end of the hall crouched a white Venus, shrinking from his approach.

He turned to the loggia. The door was not locked and he stepped into the open, peering down from between the columns into the width of the piazza.

No one stirred across that great pavement; he could hear the sound of the fountain waters in the middle of the place like the soft rushing of a wind.

From the loggia he turned through the next door and found himself in a large anteroom lighted clearly enough by two lamps which no doubt had been supplied with oil to burn all the night through. There lay the hat of Giovanpaolo, shining with an incrustation of pearls all over the crown. On a chair were piled the cuirass, the leg armor of finest steel; a two-handed sword leaned in its sheath against the chair. On the table were a pair of golden spurs with immensely long rowels. And beside the spurs lay an open book, beautifully printed according to the new art which had been introduced through Italy from Germany, that distant nation of northern barbarians. It was strange, thought Tizzo, that any art could come from that misty, northern region!

Through a doorway adjoining he passed into a chamber far more dimly lighted by a single small lamp from whose wick a mere tremor of flame rose, so that the shadows washed up and down the walls ceaselessly and the entire apartment became a ghostly thing.

The paintings along the walls seemed more real than the figure of the man who lay on the great bed. It stood huge as a house at the side of the chamber.

The sleeper must have had restless dreams, for even now he was stirring uneasily, gripping a hand above his head, and muttering. Half of the covers had slipped from him and spilled towards the floor.

Over him leaned Tizzo and recognized the strong, handsome face of Giovanpaolo.

He had come to the end of his short quest!

His sword was naked in his hand, now. He placed the point of it close to the throat of the sleeper and, leaning still closer, heard Giovanpaolo muttering: "Once more, men of Florence, brave fellows! If you are hungry, remember that there is bread and wine in their tents. The fat, red wine of Siena, comrades! Charge once more with me and we shall have it!"

The warrior was fighting again some battle in his sleep as Tizzo murmured; "Waken, my lord! There is a sword at your throat."

THE rousing of such a warrior as Giovanpaolo was like the rousing of a lion, Tizzo knew, and he watched with apprehension and curiosity. Giovanpaolo, opening his eyes, looked without a start along the steady gleam of the sword and up into the eyes of the youth.

"So, Tizzo?" he said. "Murder?"

"If I'd wanted to murder you," said Tizzo, "as much as you've wanted to murder me, I could have drawn the edge of this sword across your throat or dipped the point of the dagger into your heart. I have come to talk to you."

"Let me reach the sword in that chair and I can answer all your questions," said Giovanpaolo.

He sat up in the bed, looking earnestly at Tizzo.

"Why have you wished to murder me?" asked Tizzo.

"I've had no such wish," said Giovanpaolo.

"You knew that armed men were posted at the summer house of Messer Astorre, waiting for me," said Tizzo.

"I knew that a trap was baited. I could not believe that such a clever cat as Tizzo would play the mouse and walk into the danger."

"But if I were fool enough to go—there was the end of me, so far as you are concerned?" asked Tizzo.

"My dear Tizzo," said the warrior, "what use have I for fools in my life? I knew you were a brave man and a good fighter, so I valued you; but if you were fool enough to throw your eyes on Lady Beatrice with hope, you are no more to me than a dog that bays the moon."

Tizzo regarded the Baglioni with a curious eye. There was no fear in this man, and there was a ruthless frankness of truth in his remarks, as though the long, keen blade of the sword were no more than a pointing finger.

"Sir Giovanpaolo," said Tizzo, "if I have looked at the lady it is because I love her as other men love angels in heaven."

"My friend," answered the Baglioni, "every pretty girl is as bright as a star—while she is at a distance. I want to keep you from Lady Beatrice."

"Who means to you," agreed Tizzo, gloomily, "a strong marriage with some powerful house."

"She means that to us," answered Giovanpaolo. "Men who rule cities, Tizzo, cannot be governed by ordinary motives. Beatrice is a pretty thing, and moreover she is a Baglioni, therefore she has to be of use to the house. And what are you? A fellow with a fine flame on his head and a fine spark in his eye—but no more."

"My lord," said Tizzo, straightening, "the reason I came to you was to ask for an explanation."

"I have given you one," said Giovanpaolo, looking both at the sword and the man without fear.

"I was sworn to your service," said Tizzo, "and yet you were willing to throw me to the dogs of Marozzo."

"It was he who had the forethought and the information," answered the other, shrugging his shoulders.

"The Lady Beatrice was to be the bait, and I was to be the rat for the trap!"

"If you play the rat's part, you must die the rat's death."

"And you, my patron, for whom I have fought with my sword—you let me go to my death?"

"No. I gave you a fighting chance but a good one. To a man who loves you like a brother, to that same Bardi who owes his life to you, I let a hint be given that you should keep at home to- night."

Tizzo started. "And if I had done as he advised me to do?"

"Then, when Marozzo's trap had closed on nothing, I should have seized his house and his possessions, given a moiety of them to you, and had him beaten from Perugia with whips; as a man who dared to conspire against and falsely accuse my nearest followers."

TIZZO was staring, now. There was a queer, crooked, cruel morality in this attitude of mind that he could not fathom. He could see the fact, but he could not feel any understanding of it.

"Instead," he said, bitterly, "the lady is closed inside a convent until you choose to bring her out for a political wedding, and I am an enemy of your house forever."

"Not unless you wish to be one," said Giovanpaolo. "All the qualities that I saw in you before are in you still. I have removed the temptation of Lady Beatrice from your way and I have flashed a sword in your eyes. There is no reason why we should not carry on as we have done before."

"There is a reason," said Tizzo, his heart beating high.

"Name it to me, then," answered Giovanpaolo.

"You have set a trap for me and therefore you are a traitor to me, my lord. What keeps me from driving this sword through your heart, then?"

"A certain foolish set of scruple prevents you," said Giovanpaolo. "Am the light in your eyes, Tizzo, is the love of battle, not of murder. You cannot strike an unarmed man."

"It is true," said Tizzo. "But then is plenty of light in the next room You have a sword there and another on this chair. These apartments are set off from the rest of the house so that the clashing of swords will bring no interruption to us. Your highness, we will fight hand to hand and wash our stained honors clean with our blood."

"That," said Giovanpaolo, "is as childish and mad an idea as I have ever heard, but I like it."

He rose from the bed and picked up from the chair beside it a sheathed sword. The scabbard fell away with a hissing sound and left in the hand of the Baglioni a blade as like that of Tizzo's as a twin brother. Giovanpaolo led the way straight into the next room and from the scattered clothes selected hose, doublet, and slippers. Now that he was dressed, he took his position and weighted the balance of his weapon. His sleeve, thrust back to the elbow, showed a forearm alive with snaky muscles. The wrist was perfectly rounded by the distention of the big tendons. Stories of the terrible cunning and strength of this man rushed back upon the brain of Tizzo; for in Giovanpaolo there was the brain to plan great battles and then the courage of a hero to lead his soldiers through the fight.

"Now, Tizzo," said Giovanpaolo, "I'm to thank you for this pretty little occasion. How often do we have a chance to fence with honest, edged weapons? How often does blood follow the touch?"

He began to advance, slowly.

"I shall have to let the world know that you burst in on me like an assassin," he said, "but I shall have you honorably buried. Tizzo, I salute your courage, I smile at your folly. Defend yourself!"

On the heel of these words, he rushed suddenly to the attack. Tizzo, having marked everything in the big room, gave back before the assault, and at the first ringing touch of steel against steel, he knew that he had met a great master.

Let the teachers, the schoolmasters of fencing, talk as they pleased; the important matter was not the clumsy swaying of the edge of the sword but the snakelike dartings of the point, which gave a more dangerous wound without exposing the assailant so widely. In that understanding, Tizzo had fenced many a long hour with Luigi Falcone; it was the point, also, which the wild daredevil of an Englishman, the Baron of Melrose, had used against him. And now it was with the point that Giovanpaolo pressed home the attack. He attacked hungrily, and yet with a smooth beauty of movement. For a moment, Tizzo was bewildered, his heart in his throat. Then he thought of the shadowy murderers who had waited for him in the summer house of Messer Astorre, and he met the attack with a savage countering.

THE lightning feet of Tizzo were his defense and his attack.

The sleights of a magician's hands were no more subtle than the

flying of his feet, the intricate dancing measures through which

they passed.

Twice, in as many minutes, Giovanpaolo cornered his man and set his teeth with a grim, furious purpose to drive the sword through the body of the enemy; and twice, with hardly a parry, Tizzo swayed from the darting point and was away.

Giovanpaolo began to sweat. He drew back to take breath, measuring his man and the work before him.

"By God, Tizzo," he said, "you are such an exquisite master that my heart bleeds to think that I must lose you through my own handiwork. Defend yourself!"

He leaped again to the attack. The man was as cunning as a fox, leaving apparently wide openings to invite the point of Tizzo's blade and flashing a murderous counter attack the moment Tizzo lunged at the opening. But Tizzo, holding back, with a carelessly hanging guard, met the assaults, moving his sword arm little, his feet much. There seemed to be an intricate pattern on the floor, in every one of whose divisions he had to step. Death darted past his face, his throat, his body, but it always missed him by a hair's breadth.

And then Tizzo began to attack in earnest. He had fathomed the consummate science of his man, by this time. Now he pressed steadily in, until Giovanpaolo began to groan faintly in his breathing. His face turned pale; it was polished with sweat.

Here a heavy beating came against the door.

"Who is there?" called Giovanpaolo.

"In the name of God, your highness, we have heard swords clashing in your rooms!"

Giovanpaolo looked at Tizzo for an instant. A faint, cruel smile dawned on his face.

But he answered: "I am fencing with a friend. Be gone and leave us in peace."

"There is one other thing, your highness. The noble Mateo Marozzo is now in your house, his face horribly wounded. Tizzo, men say, has escaped from a dozen men, branded the face of Mateo Marozzo forever, and escaped. But he is still in Perugia. Shall all the gates be guarded for him?"

"No!" called Giovanpaolo. "He is already gone! Let me be in peace!"

Footfalls obediently withdrew.

Tizzo said: "Your highness, I have always known that you must be such a man as this. You could have let your servants in to kill me like a blind puppy. I thank you. Your highness is troubled; your breath is short and you arm is tired. Shall we end this fighting?"

"End it?" exclaimed Giovanpaolo. "Do you think that I shall ever give over a battle I have entered upon?"

He came in with a desperate, last strength. Twice the leap of his sword blinded the very eyes of Tizzo. And he, half down upon one knee, used suddenly the secret stroke which the Baron of Melrose had given to him as a treasure.

The sword of Giovanpaolo, knocked from his hand, wheeled brightly in the air and then descending, thrust straight through the cushioned bottom of a chair.

Giovanpaolo himself, unabashed, hurled himself straightforward at Tizzo, in spite of the level gleam of the weapon that pointed at his breast.

And Tizzo could not strike the final blow! His arm turned weak and senseless to make the stroke. Giovanpaolo, brushing past the bright point of danger, grasped the doublet of Tizzo at the neck and thrust him back against the wall. The other hand caught Tizzo's sword hand at the wrist.

So for a moment they stood, with the glare of savage beast in the eyes of Giovanpaolo.

But this fire died out. His hands left their holds. His head dropped forward wearily on his breast. He turned from Tizzo and, slipping into a chair, rested his forehead on the heels of his hands.

Tizzo sheathed his sword and felt gingerly the bruised muscles about his throat.

"To be beaten—and then spared—like a dog!" groaned Giovanpaolo.

Tizzo went to the loggia door and paused there.

"Your highness," he said, "I cannot fight under you any longer; and it is seen that God will not let me strike against you. Therefore I leave Perugia forever. Farewell. To the Lady Beatrice, say that I send my prayers—"

"Be silent!" commanded Giovanpaolo. "Pour wine for us at that table, and bring it at once."

TIZZO, with his brain quite adrift, unfathoming the purpose of the Baglioni, obediently poured two silver goblets full of pale, golden wine and brought the drink. Giovanpaolo raised himself suddenly from his chair. He picked up one of the beakers in his left hand and motioned Tizzo to do the same.

"Now, Tizzo," he said, "you have taken service under me before. In the meantime, you have dared to look past your height to the Lady Beatrice. In reward for that, I have allowed you to be trapped. You were a step from death in the summer house of Astorre tonight. I have been half an inch from death in this room. Tizzo, for the evil I have done you, forgive me."

"Forgive you?" said Tizzo, overcome by the humility of this fierce master of Perugia. "Highness, I have forgotten all offense!"

"You have beaten me," said Giovanpaolo. "It could be in my heart to hate you, Tizzo; it is also in my heart to love you. I cast the hate away"—here he spilled a little of the wine purposely on the floor—"and I take the love, instead. This cup, Tizzo, is filled with immortal friendship. Beware before you taste the wine. If it passes your lips it is as though you drank my blood. Do you hear me?"

"I hear you, highness," said Tizzo, beginning to tremble with a great emotion.

"Are you prepared to be with me two hands, two hearts, two souls of friendship?"

"I am!" said Tizzo.

"Then give me your hand!" said Giovanpaolo, grasping that of Tizzo at the same moment. "I drink to you, Tizzo, in token that so long as blood runs in my body, it is your blood and ready to flow for you."

They drank, and setting down the silver goblets stared at one another for a moment, as men who already saw a strange future stretching before them.

"Giovanpaolo," said Tizzo, "this is a beginning. Whether it be a dry death or a wet one, by steel, or fire, or bullets, or starvation, may we come to the same ending together."

Giovanpaolo, picking up from the table a heavy ring of gold, laid it on the floor and stamped on it. He lifted it, snapped it in two parts.

"Take this," he said to Tizzo. "Whatever message comes with it, night or day, if the half of the ring fits with my half, I shall go at once to answer you."

"If your portion comes to me in the same manner," answered Tizzo, "by the blood of God I shall come to you in spite of ten thousand."

"So, so!" said Giovanpaolo. "We have spoken in a very high strain for a few moments. Sit down, my friend. But—sacred heaven! When I think that a moment ago I stood with a naked breast in front of the point of your sword, I am still amazed. Where did you learn that last trick of the blade, Tizzo? Or did some devil of an enchanter teach you the thing? Will you teach it to me?"

"Whatever I know I shall teach you—and that same stroke as soon as I have the permission of the man who taught it to me."

"Who was that?"

"Henry, Baron of Melrose."

"That wild-headed Englishman loves you, I know, Tizzo. He put his head in jeopardy to keep you from death when he rode into this city and gave himself into the hands of Astorre to have you set free. Do you give medicine to make them love you, Tizzo? What is Henry of Melrose to you—except that he is the chief leader of the forces of the Oddi and plots daily against the lives of the Baglioni?"

"He is," said Tizzo, "a friend of the Oddi, for what he chiefly serves is chance and the bright face of danger. To follow danger, he has left his country and ridden around the world. At last he came seeking for me; and for what mysterious reason I still cannot tell. He values me, I know, and again I cannot tell why. And that not in modesty, but because the strange love of this man amazes me! I only know that he came one day into my life, dashed me away from all the future I had come to accept, and swept me away at his side in the pursuit of adventure. There the Lady Beatrice crossed my way. You know how I set her free from the Oddi and followed her here. You know how that pursuit of her almost won me my death at the hands of Marozzo. And now it has led me to the rooms of your highness—and made us pledge our hands together."

"ALL spoken like a prophet," said Giovanpaolo. "It is true that you are a wild-headed lover of the Lady Beatrice. Now tell me what you would have me do? Marry you to her?"

"Five minutes ago," said Tizzo, "I would have stolen her with poison or swords. Now I would not lift a finger to come near her without your special permission."

"So?" said Giovanpaolo. "If men were like you, I should have to give up war and my old way of living; I should have to take to frankness, honesty, truth and mercy. Let me tell you this—if the time comes when I can persuade old Messer Guido, the head of our house, you shall marry Beatrice on that day. And I'll carry you to see her this moment."

"You will?" exclaimed Tizzo.

"This moment," said Giovanpaolo, "she shall be set free from the house of the Clares and permitted to see you."

"Wait!" said Tizzo. "Before I take so much from you, tell me in what way I shall be able to serve you? Tell me, quickly, before my heart bursts, that service of which you are most in need."

"I should have to drop you like a plummet into the sea, deeply into the heart of a man who smiles in my face but who is, I fear, my greatest enemy," said the Baglioni.

"Let me go to him then," cried Tizzo, "and I shall read his mind and you shall know his present attitude."

"Tizzo, if you could do that, the weight of the world would be remove from me!"

"What is his name?"

"Jeronimo della Penna."

"But he is one of the chief friends of the Baglioni."

"So he seems," said Giovanpaolo, "but as a matter of fact he is known to have been kind to our enemies, of late."

"Would he then have been kind to me if the world did not know that you and I have been reconciled to-night?" asked Tizzo.

"How?" asked Giovanpaolo sharply.

"For all that is known to others," said Tizzo, "I have been pursued through the city by your riders—"

"There I was at fault," said Giovanpaolo.

"It is forgotten," answered Tizzo. "But suppose that tomorrow you put a price on my head and proclaim me an enemy? I return to the house of my foster-father. There is an estate of this della Penna close by. If he truly hates you, and learns that I also am your enemy, will he not try at once to make me his friend?"

Giovanpaolo laughed, suddenly and loudly.

"Our friends are the eyes that look into the hearts of the world; the ears that listen to its mind. With two more like you, Tizzo, I should be able to conquer Italy in six months.—But wait—there is a frightful peril. You and I alone will know the truth. All of my family will hunt you down like a wild beast the moment I put the price on your head; and you know already that the Baglioni can be cruel enemies."

"You, and I, and the Lady Beatrice will know the truth," said Tizzo. "That is enough for me. Nothing is gained without danger. If della Penna is your enemy, within two days I shall know the degree of his hatred. You may depend on that."

"It is done!" said Giovanpaolo. "Here, cloak yourself with this and pull the hood down over your head. Already it is dawn. We shall go to Beatrice now!"

Wrapped in a length of blue velvet that muffled his body and his sword, with the hood pulled down over his face, Tizzo a moment later was passing down the halls, down the great stairs, through the tremor of life which the night lights revealed along the painted walls of the house of Grifone and so out onto the street, where he walked eastwards with Giovanpaolo towards a great, golden Venus which blazed in the green forehead of the morning sky. But the lesser stars already were withdrawing to their distances like the lights of a retreating army.

So they came to the high, bald front of the convent of the Clares, where the porter saw the face of Giovanpaolo and bowed very lowly as though he would strike his forehead against the floor.

Tizzo, smiling, was always ready for a encounter.

WHEN young Tizzo, daring adventurer and master swordsman, rode through the streets of old Perugia to keep a rendezvous with his beautiful lady, Beatrice Baglioni, after having been warned that he was heading straight for danger, little did he realize that his secret visit to the house of the powerful Baglioni would end the way it did. He learned that his attention to Beatrice had incurred the enmity of her brother, Giovanpaolo, and that a price had been set on his head. Learning that Beatrice had been taken to the Convent of Poor Clares, Tizzo made his way to her brother's room, and after a fierce struggle, vanquishes him in a duel. Giovanpaolo pledges eternal friendship with him, and asks Tizzo to help the House of Baglioni rid itself of its insidious enemies—particularly the treacherous Jeronimo della Penna.

Tizzo agrees to undertake the mission, realizing that if he is successful he will have the hand of his beloved Beatrice who means so much to him.

Elia Bigi, Tizzo's faithful minion; Luigi Falcone, Tizzo's foster-father, and his old friend, Henry, Baron of Melrose, all help him toward the accomplishment of his task.

TIZZO, striding anxiously up and down in the reception room, looked again and again towards the shimmering bars of iron which set off the room from the little cell in which the sisters of the order might appear to converse with their friends. He had waited, he was sure, for hours, before hinges moved with a dull, grating sound, and then a candle was carried into the cell by a veiled girl with a beautiful face.

Tizzo leaped to the bars and grasped them.

"Beatrice!" he said.

"Hello!" exclaimed Giovanpaolo. "Can you see her face through that veil, Tizzo?"

The girl tossed back the hood and came to the bars.

"This is a strange summer house for our meeting, Tizzo," she said without emotion.

He took one of her cool, slender hands and stared, entranced, into her brown eyes.

She was above all a Baglioni in the immensity of calm with which she faced every crisis.

And now, looking past Tizzo, she exclaimed, "Is that the traitor? Is that Giovanpaolo? O that I ever thought I loved you!"

"Beatrice," said Giovanpaolo, "Tizzo is now my sworn brother. He has forgiven my sins; will you do the same?"

"How did you buy him, Giovanpaolo?" asked the girl.

"With my love," said the warrior.

"It is something that turns as quickly as a page," said the girl.

"With my faith," said Giovanpaolo.

"I could blow away a thousand faiths like yours on one breath," she declared.

"With my right hand," said Giovanpaolo.

"Has he given you his hand?" she asked suddenly of Tizzo.

"And have given him mine," said Tizzo.

Her face softened suddenly.

She said to Giovanpaolo:—"You are as dangerous as a poisoned knife, or treachery by night; but I can still love you a little for the sake of Tizzo. Tell me what it means, though, when you bring Tizzo to see me here? Am I to suspect anything?"

"It means that when Messer Guido gives his consent, you two will be married, if you still love this red-headed fellow.

"But mind you, Beatrice—his brain is really on fire."

"I know it," said the girl. She looked earnestly at Tizzo "Do I love you, my dear?" she asked.

"Somewhere in your wicked heart there is something that cares for this worthless self of mine," said Tizzo.

"Yes," she answered. "But last night when I walked into the trap for your sake—when I went down over the lawns trembling like a silly fool and whispering your name—I hated you for the thing that I found! Yes, how I hated you!"

"Did you hate me, Beatrice? I came to the place honestly, as I told you I would, and before the time. And there I was!"

"Do you know what I found there?" she asked.

"Marozzo?"

"Yes. My wretched maid had sold my secrets to him; and Giovanpaolo let him use what he had learned."

"I was to blame," said Giovanpaolo.

"Some day," she said fiercely, "I shall pay you home for that, my handsome cousin!"

"Hush!" said Tizzo. "I have put my mark on Marozzo."

"Have you?" she asked, eagerly.

"With the point of my dagger I have drawn a cross on his forehead, that will make him a crusader the rest of his life. No doctor will ever rub that mark away."

"Tizzo, I love you!" said the girl.

She threw out her arms to him through the bars, but he only took her hands and kissed them.

"Why not my lips, Tizzo?" she cried.

"Never," he answered, "till I am sure that you love me—not for the shame I have done to Marozzo but for myself."

"Do you see?" said the girl to Giovanpaolo. "He makes bargains and draws up definitions. This comes from his study of Greek. God forgive me if I ever marry a scholar. Tizzo, when will you be sure that I love you for yourself?"

"Only," he answered, "when you and I have faced the devil together and plucked a few hairs from his iron beard."

THE Mulberry, orange and lemon trees flavored the airs that blew over the house of Luigi Falcone, and through the lawns of his garden great-headed plane trees gave shade and spear-headed cypresses marked the walks and circled the fountains. There was an artificial lake expensively produced by diverting the water from a creek among the hills and leading it here to fill an excavated hollow in the midst of the garden. The soil of the excavation had been used to create raised, flowering banks around the pool, and in the center of the lake there was a little island on which stood a summer house. Its form was that of a little Greek temple with graceful Ionic columns that threw a white glimmering reflection across the water, and the principal use of the water was that it acted as a 'barrier across which the world could not step in order to invade the privacy of Luigi Falcone when he chose to sit here alone with his thoughts. A Venetian gondola with a gondolier lolling under its canopy, waited on the convenience of the master.

This fellow now started up, for his name was called.

"Olimpio! Fat-witted, lazy Olimpio!"

"Mother of heaven!" said Olimpio. "It is my master!"

And he leaped up to the deck and to the handle of his oar. As soon as he saw the flaming head of Tizzo under the shadows of the trees that crowned the bank, Olimpio began to lean his weight on the long oar and drive the little bark furiously forward.

"Wait here," said Tizzo to Elia Bigi. Before he left the town of Perugia he had said to the one-eyed servant: "Elia, I am about to leave Perugia as a proscribed man with a price on my head. You can sit here and keep my rooms, or you can ride with me and risk your neck." And the grotesque answered: "Well, if I stay here I shall lose my appetite and the only eye that's left to me will grow dull as an unused knife. But if I go with you, every day will have a salt and savor of its own." So he had ridden with Tizzo, each with a shirt of the finest Spanish mail, and a steel- lined bonnet, and the pair of them got hastily from the town.

The gondolier, bringing his boat swiftly and gracefully along the side of the little pier at the edge of the lake, held out both hands with a shout, but Tizzo leaped from the pier exactly into the center of the gondola.

"Tizzo!" cried Olimpio. "Ah, two-footed cat. You could drop from a tree-top and never break the leaves that you landed on. Welcome home! Welcome, welcome! You have been dancing with the devil in Perugia and still he has not turned your hair gray!" Tizzo shook the greeting hands warmly and laughed: "The best day is the day of the returning. Is your master on the island?"

"He is there with a Greek manuscript, and I hear him chanting the words and striking the lyre," said Olimpio. "He will make it a fiesta when he knows you have come!"

In fact, as the long, narrow gondola went swaying across the smooth water of the lake, Tizzo heard strings of music sound from the little temple, and when he stepped ashore, he recognized a chorus of Aristophanes, sung with a fine gusto to that improvised accompaniment.

A great cry greeted this singing, and from the columns of the temple, as the gondola touched the shore, there ran out a tall, bald-headed man who threw up his hands with a shout when he saw Tizzo.

FOR a moment it seemed to Tizzo that he was again the nameless

waif of the village streets, standing agape as the "lord of the

castle" went past him. And then, like the blurred flicker of many

pictures, his memory touched the years when he had entered this

house as the humblest of pages and grown at last to the position

of foster son and heir.

Now he had fallen into the arms of Luigi Falcone. Now he was being swept into the little summer house where the harp stood aslant against a chair and, on a table, were scattered the yellow parchments of old manuscripts.

"What have you been doing with your Greek, Tizzo?" demanded Falcone.

"I've been using it to sharpen my sword," said Tizzo.

"I've heard that you and Giovanpaolo Baglioni are like two brothers together; and a man must have a sharp sword to be a brother to Giovanpaolo. But Perugia is a city of murder."

"I'm a proscribed man with a price on my head," said Tizzo. "Haven't you heard that?"

"Proscribed? By the Baglioni? Tizzo, what are you doing lingering here so close to Perugia? Wait! I'll call for horses! We'll send you as fast as hoofs can gallop—"

"I've fled all this distance from Perugia and I'm tired of flight," said Tizzo. "I'm going to stay here."

"They'll come in a drove and slaughter you, lad!"

"Perhaps they will. But the fact is that a man has to die some time, and it's better to be struck down from in front than shot through the back. I'll run no farther. It's as easy to die young as it is to die old."

"Of course it is," said Falcone.

"But are you really resolved to run no more from the Baglioni?"

"Not another step—today," said Tizzo, and laughed.

Falcone laughed in turn. "The same blue devil is in your eyes and the same red devil is in your hair," he said with a smile.

"We'll go into the villa. I have some French wine for you. You shall tell me everything; and I'll give orders that every man on my place shall take weapons and be prepared to fight for you!"

"Not a stroke! Not a stroke!" said Tizzo. "I've made my own fortune and whatever is in the cup I'll be ready to drink it, alone."

They went back in the gondola, and as he left the boat Tizzo gave some golden florins to Olimpio. "Turn them into silver," he said, "and scatter them among all the servants. Tell them that the Baglioni want my life and that if it is known that I am here in the Villa Falcone, I'm not better than a dead man."

"Ah, signore," said Olimpio, his eyes still startled by the sight of the gold, "we all are ready to die for you; not a whisper will come from one of us."

But as they went on towards the large house, Falcone said: "Tizzo, that is the act of a child, really! You tell them that the Baglioni are hunting you, and you ask the servants to say not a word. But how can they cease from talking? They have heard no gossip like this for many years! You have come back from Perugia with the atmosphere of a hundred duels about you.

"So how can they keep from talking about you?"

"Let them talk, then," said Tizzo. "Even mute swans have to sing when they die. Let them talk."

"In fact," said Falcone, suddenly stopping, "it is a part of your plan to have them talk?"

"Perhaps it is," agreed Tizzo. "But don't ask me what the plan may be."

"I SHALL ask nothing," said Falcone. "Even when the wasps

begin to hum, I'll try to brush them away and merely go on

rejoicing myself in you, Tizzo. Tell me everything! What have you

learned in new sword-play? Are you content in Perugia? Why don't

you decide to travel across the world? There are great new things

to see, in these days. But you hear everything in Perugia,

because it is on a main road to Rome. Tell me all the news of the

world, Tizzo! I hunger to learn it!"

They sat in an open loggia near the top of the large house, looking over the green rolling of the Umbrian hills; the sun- flare shimmered over all. They drank white wine of Bordeaux, cooled with packings of snow.

"I strike out at random and tell you whatever I've heard," said Tizzo. "The traitor Warbeck has been executed in England."

"I knew that," said Falcone.

"The Emperor rages because the Swiss are at last free from him. But at Dornach they beat him so thoroughly that they have a right to rule their own lives. In Spain, the great Ferdinand has broken his promise and begins to burn the Moriscoes like firewood. A certain great sailor of Portugal, one Vasco da Gama, has returned after finding a way around Africa to the Indies. The Venetians groan because the Turks beat them last year at Sapienza; they swear to have their revenge soon. But Kemal-Reis is a fighting demon by sea. The Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon, is betrothed to Prince Arthur, of England, the son of that sour-faced money-changer, Henry Tudor. Louis XII is annexing Milan and bargaining with the Spaniards. That's an unhappy day for Italy! The Diet of Augsburg is stealing some of the Emperor's powers from him, they say. Pedro Cabral has touched the shore of a great land in the Western ocean; he has called the thing Brazil. It is south of the islands which Columbus discovered for Spain, and people begin to say that it is not the Indies which Columbus discovered. It is new land, with a new, red-skinned people living on it. There, my father, I have burst open all the latest news in one packet. I suppose you've heard most of it before."

"Not as I hear it now," said Falcone. "The world is wakening, Tizzo, and great things will come to pass. The new printing press with its moveable types will multiply books throughout the world. Gun-powder knocks down castle walls. A common man with a harquebus may stand at ease and kill with a single shot the knight in complete armor. God alone can tell where the world is tending. But you—Tizzo—how have you ever tended except to mischief?"

So they sat talking and laughing together while the day ran on towards the evening. The dusk was descending blue and soft after the hot summer day when a whistle sounded from the trees near the villa and Tizzo bounded to his feet.

"Is it danger? Wait for me, Tizzo?" exclaimed Falcone. "I catch up my sword and follow you instantly—"

But Tizzo was gone, flashing through the bright, painted rooms, leaping down the stairways and then out the door into the garden.

There he found a big, gray-headed man whose eyes shone even through the dimness of the twilight. He wore heavy riding boots; his doublet was wide open at the base of his great throat. A small round hat, plumed at one side, sat jauntily on his head, and at his side a heavy sword made a light shivering sound of steel against the scabbard as he moved to greet Tizzo. Even Luigi Falcone, even Giovanpaolo Baglioni were no greater in the eyes of Tizzo than this man who had made him the gift of one consummate trick of sword-play.

THEY greeted each other as men who have owed their lives to one another. Then, as Baron Melrose pushed himself back to arm's length, he surveyed the younger man with care.

"You are no bigger in the bones than when I last saw you," he said. "But neither is the wasp as big as an eagle, and yet it can trouble a man more. Still, I could wish that there were twenty English pounds of extra beef on you. Then you could spend more muscle and less spirit in your wars."

"My lord," said Tizzo, "I am what I am—a starved thing compared with you, but ready to guard your back in any battle. Tell me, how do you dare to show yourself so near to Perugia? Are the Oddi rising to try to re-take the town? How did you know so quickly that I was at the Villa Falcone? Where have you been since I last saw you?"

"If I had four tongues and four separate sets of brains, I would begin to answer all those questions at once," said the big Englishman, laughing. "But as the matter stands, I have to speak them one by one. As for the Oddi, their secrets are their own. I am no nearer Perugia than I have been for a month. And I knew you were here because a whisper ran through the kills and came to my ears. Now for one question in my turn: Have you broken with Giovanpaolo, Astorre, and all the Baglioni?"

"I've crossed swords with Giovanpaolo," said Tizzo. "I've had my life attempted in the garden of Messer Astorre. And a price has been put on my head."

"Have all of these things happened?" asked Henry of Melrose. "You can pick up trouble faster than a pigeon can pick up wheat. But if the Baglioni have closed one door in your face, another opens of its own weight behind you. Tizzo, Jeronimo della Penna wishes to speak to you."

"About what?"

"He will open the subject to you himself."

"Tizzo!" called the anxious voice of Falcone.

"Say farewell to Falcone," said Melrose, "and meet me again here. That is, if you wish to face della Penna tonight."

There was nothing that Tizzo wished to see less than the long, dark face of Jeronimo della Penna, but it was for the very purpose of sounding the depths and the intentions of this man that Giovanpaolo had schemed with him. Therefore:—"I return in one moment!" said Tizzo, and hurried to meet Falcone.

"I'm called away," said Tizzo.

"Into what?" demanded Falcone. "Tizzo, you shall stay this night, at least, in my house."

"I have to go. I am compelled," said Tizzo. "As surely as a swallow ever followed summer, so I have to follow the whistle that sounded for me tonight."

"It's a thing that I don't like," said Falcone. "But the devil befriends young men. Good-by again. Wait—here is a purse you may need—no, take it. God bless you; come to me again when you can!"

And Tizzo was away again to the side of Melrose.

They walked on through the gardens until they heard the ringing strokes of an axe in a hollow, followed by the crashing of a great tree. The fall of the heavy trunk seemed to shake the ground under them.

"There are friends of mine, yonder, working by lantern light," said Tizzo. "And I must speak a word with them. Wait here—or at least keep out of their sight."

Tizzo, hurrying on, came on three foresters who worked by a dim, shaking light which had been hung from the branch of a small sapling. Unshaven of face, ragged in their clothes, the three were preparing to attack another huge pine tree with axes.

"My friends!" called Tizzo, stepping into the faint circle of the light. "Taddeo—Riccardo—Adolfo—well met again!"

The three turned slowly towards him. Old Taddeo began to nod his bearded head.

"Here comes the Firebrand again. What forests have you been burning down, Tizzo? Is it true that the Baglioni are leaning their weight and ready to fall on your head?"

Tizzo grasped their hands. "I've had my hands filled with something besides axe shafts," he admitted. "But I'm happy enough to see you all again."

"Your hand has turned soft," said Taddeo.

"It is harder than my head, however," laughed Tizzo. "Why are you working so late?"

"Because the overseer drives us like dogs."

"I'll speak to my father. You shall not be enslaved like this!"

"NO man is a slave who has mastered an art," said Taddeo.

He waved his great axe with one hand. "And we are masters of ours!" he added. "But have you touched the haft of an axe since we last saw you?"

"An axe has helped me more than a sword," said Tizzo. "Give me a mark and let me show you that my eye is still clear."

Old Taddeo struck the trunk of the tree a slashing blow and left a broad, white face, large as the disk of the moon and shining brightly.

"There is the target. Make a mark for him, my sons," said Taddeo.

Big Riccardo, chuckling half in malice, drew out a knife, picked up a straight stick to make a ruler, and calmly drew a five-pointed star with the sharp steel edge. Where the knife cut the white of the pine wood it left a thin, glistening streak, hardly visible except to a very fine eye.

Old Taddeo ran the tips of his hard fingers over the design and laughed loudly.

"Let me see it done, then!" he said. "It has never been managed before even by the oldest woodsman in the forest. Strike at that target freely, Tizzo. There are ten strokes to make and with the tenth the star should leap out from the tree. And then see that every one of your strokes has hit exactly the ruled line. Ten strokes without a single failure—here is my own axe to use, and if you succeed—why, the axe is yours!"

Tizzo accepted the axe and looked down on it with attention. Of old, from his boyhood, he had heard about that axe, and he had seen it swung, more than once, in the hands of Taddeo. The steel had a curious look. It was blue, with a strangely intermingling pattern of lines of gray. And the story was that once a fine Damascus blade had been brought back from the Orient, and being broken it had been re-welded by the father of Taddeo, not into a new sword, but into an axe-head. That matchless steel, supple as thought, hard as crystal, had been transformed into a common woodsman's axe. The blue shining of it seemed to be reflected, at that moment, in the flame-blue of the eyes of Tizzo as he swayed the cunningly poised weight of the axe.

For two life times that axe had been in use, the handle altered, refined, reshaped, so as to give it a gently sweeping curve. The balance was perfect. It grew to the hand like an extension of the body.

Tizzo threw down on the ground the purse which he had just received from Falcone.

"I take the challenge, and if I fail, that purse is yours, my friends. Watch me now, Taddeo. Watch, Riccardo, Adolfo! There are ten enemies; if I miss one of them, the gold in that purse is your gold, and you will all be rich for ten years!"

So, measuring his distance, swinging the axe lightly once or twice to free his muscles, he suddenly attacked the dim target with no calm deliberation, but with a shower of strokes, as though he stood foot to foot with fighting antagonists. With each stroke the axe bit in deeply; and with the tenth a block of solid wood leaped out from the blazed surface of the tree and fell upon the ground—a perfect star with five points!

And in the wood of the tree, softly etched by shadow, there was another star incised.

The three foresters raised a single deep-throated shout and actually fell on their knees to examine the work that had been done. But neither on the fallen star nor on the edges of the blazed surface appeared a single one of the lines which Riccardo had drawn with his knife. True to a hair's breadth, the axe had sunk into the wood.

Old Taddeo, standing up, pulled the cap from his head and scratched the scalp in meditation.

"Wise men should teach only the wise," he stated. "I have wasted my time teaching these two louts. But when I taught you the art of the axe, I taught two hands and a brain. Take my axe, Tizzo. Take my blue axe, and God give you grace with it. If it will not shear through the heaviest helmet as though it were leather and not hard armorer's steel, call me a fool and a liar! Keep the edge keen; let it bite; and the battle will always be yours."

Tizzo picked up the purse and tossed it to the old man.

"A gift is always better than a bargain," he said. "Turn this money into happiness, and remember Tizzo when you drink wine."

So he was gone, quickly, and found Henry of Melrose chuckling in the woods not far away.

"I followed closely enough to see what you did," said the Englishman. "You understand one of the great secrets; coin is made round so that it may keep rolling. And the best of buying is a giving away!"

JERONIMO DELLA PENNA had a dark, yellow skin, and a mouth which the earnest gloom of his speculations pulled down at the corners. He had large properties, but he was both penurious and absent-minded. His hose was threadbare over the knees, on this evening, but his brocaded cloak was fit for a king.

He kept striding up and down, and when he greeted Tizzo it was with a stare that strove to penetrate to his soul.

"Do you vouch for this man, my lord of Melrose?" he asked.

"I vouch for nothing," said Melrose, "except for the state of my appetite and the cleanness of my sword. Here is the man I told you about. I found him willing to come. I know he has been driven out of Perugia. Perhaps that makes him fit for your purposes. For my part, I withdraw and leave you to find out about him as much as you please. Come to me later, Tizzo. I have a room in the south tower. We can have a glass of wine together, before you sleep."

He went away in this abrupt fashion, leaving della Penna still at a gaze.

He said: "My friend, it is said that there is a price on your head?"

"That is true," said Tizzo.

"It is said that you have been wronged by Giovanpaolo. But he has a way of winding himself into the hearts of men so that they serve him more for love than for money. If he has dropped you today, can he pick you up tomorrow?"

"Perhaps," said Tizzo.

Della Penna started. "Do you think that he can take you again when he chooses?"

"How can I tell?" asked Tizzo, calmly. "I am not a man who knows the mind he will have tomorrow. The days as they come one by one are hard enough for me to decipher. Every morning, I hope to find a pot of gold before night; and how can I tell what will be in the pot? The hate of Giovanpaolo, or his friendship? It is all one to-me."

"And yet Melrose brought you to me!" pondered Jeronimo della Penna. "Tell me, Tizzo—because I have heard some rare tales of your courage and strength and wild heart—are you a man to pocket an insult?"

"I am not," said Tizzo.

"Are you a man to return wrong for wrong?"

"I am," said Tizzo.

"Are you a man I could trust?" pursued della Penna.

"I've never betrayed a friend," said Tizzo.

"Ah! You won't answer me outright?" exclaimed della Penna.

"Signore, you are a stranger to me," said Tizzo. "Why should I boast about my faith and truth? You must do as I do—take you as I find you. If you can use me for things I wish to do, I hope to shine with a very good opinion. If you try to ride me up hill against my wishes, you can be sure you'll be sooner weary of spurring than I of following the road."

Della Penna scowled.

"You are one of these fellows," he said, "who have been praised for speaking your mind right out, like an honest man."

"Sir," said Tizzo. "I think that only a fool trusts the man who is out of his sight."

"Do you know why I have sent for you?"

"I guess that you plan something against Giovanpaolo or some others of your own family who have the control of Perugia."

"If that were the case, what do I know of you?"

"Nothing except that you think I have a grievance against the same people. I make no promises; I ask none from you. If there is mischief abroad, perhaps each of us will make his own profit."

Della Penna smiled, faintly. He had found something in the last speech that appealed to him very much. Now he said: "There is one man in the world who can tell me the truth about you. But before he is through searching you, you may wish that you had let your soul be roasted on a spit in hell. Come with me, Mr. Honest Man."

THEY went down a corridor which communicated with winding stairs and came up these to an open tower from which Tizzo could look across the dark heads of the hills to a little group of lights which, he knew, shone from the village of Falcone. On this top story of the tower there was a fat old white-headed man with a red nose and a very cheerful smile, who greeted della Penna warmly, turning from an iron kettle in which he was stewing some sort of a brew over a little corner hearth.