RGL e-Book©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book©

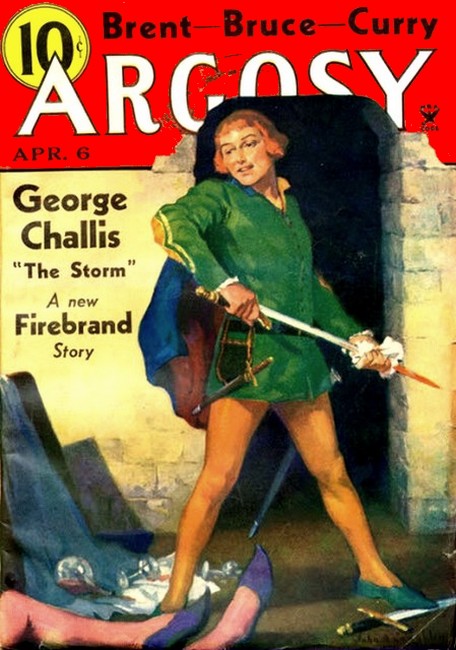

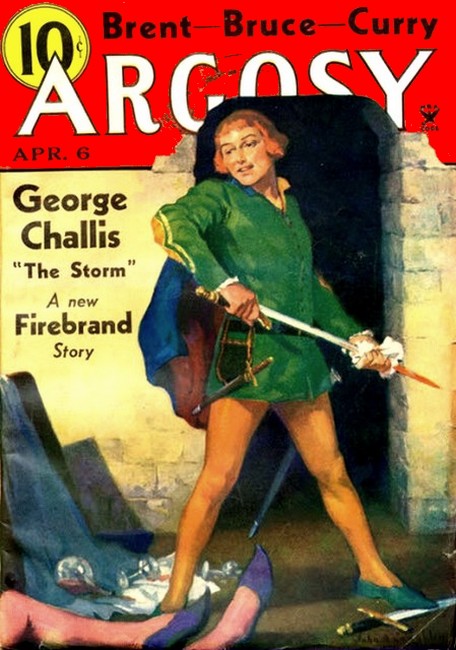

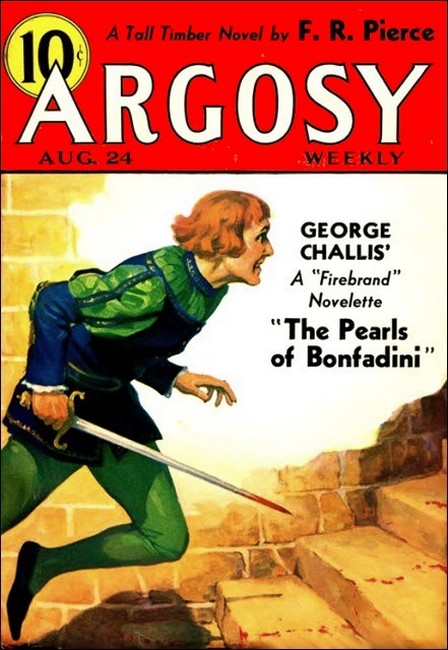

Argosy, Aprl 6, 1935, with first part of "The Storm"

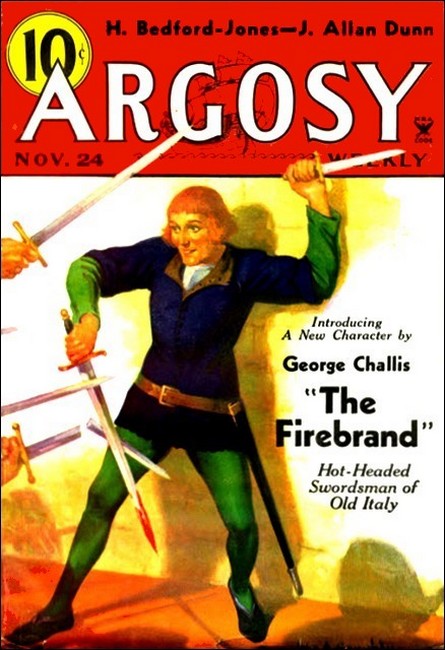

In 1934-1935 Max Brand, writing under the name of "George Challis" penned a series of seven swashbuckling historical romances set in 16th-century Italy. These tales all featured a character, Tizzo, a master swordsman, nicknamed "Firebrand" because of his flaming red hair and flame-blue eyes, and were first published in Argosy.

The original titles and publication dates of the romances are:

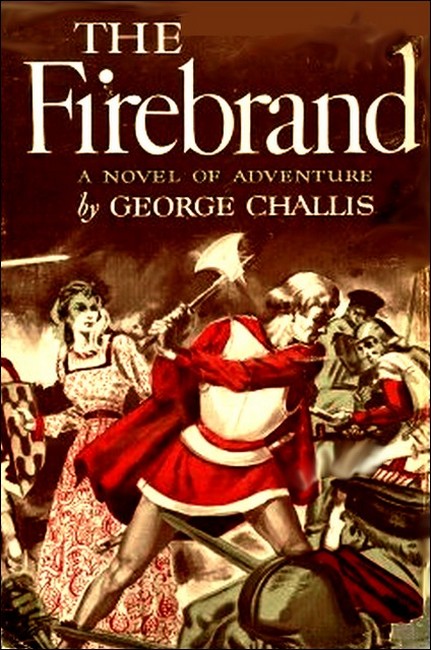

1. The Firebrand, Nov 24-Dec 1, 1934 (2 part serial)

2. The Great Betrayal, Feb 2-16, 1935 (3 part serial)

3. The Storm, Apr 6-20, 1935 (3 part serial)

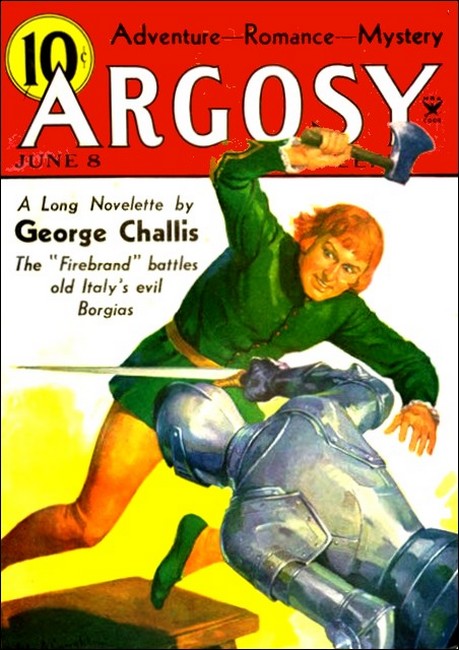

4. The Cat and the Perfume Jun 8, 1935 (novelette)

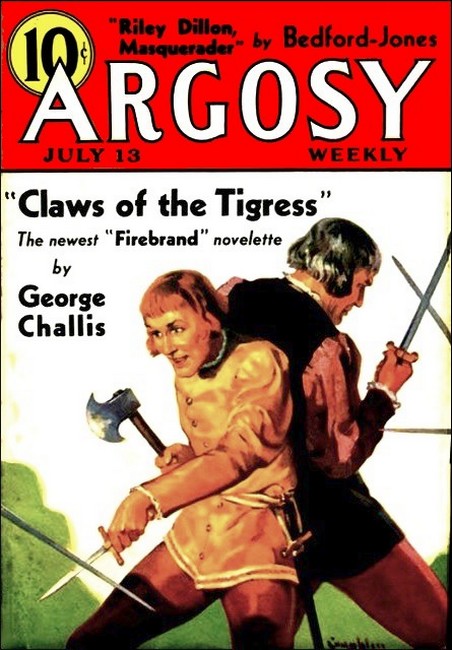

5. Claws of the Tigress, Jul 13, 1935 (novelette)

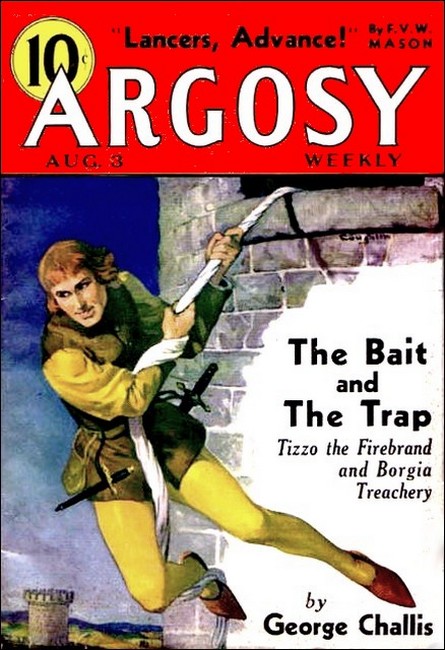

6. The Bait and the Trap, Aug 3, 1935 novelette

7. The Pearls of Bonfadini, Aug 24, 1935 (novelette)

The digital edition of The Storm offered here includes the original magazine illustrations and a bonus section with a gallery of the covers of the issues of Argosy in which the seven romances first appeared.

—Roy Glashan, December 2019.

"The Firebrand," Harper & Brothers, New York, 1950

THE hose on his right leg was orange; on his left leg it was green. His doublet was a puff of yellow and through the slashed sleeves of it appeared the crimson of an undertunic. He wore, not for warmth since the day was mid-summer, but merely from the excess of vanity and fashion, a short cloak which tumbled down from his shoulders and washed about from side to side behind them. And on his head, tilted a shade to an angle, there was a small round hat which was looped about by a fine golden chain.

As though this flare of colors were not enough to attract the eye, his hair was flame-red and glistened in the slant of the afternoon sun. He rode swiftly through the camp of Giovanpaolo and, coming to the tent of the commander, which was distinguished by the long pennon which flew from the peak, he slipped out of the saddle and threw the reins towards one of the men-at-arms who stood guard at the entrance.

The man was struck by the flying leather and allowed the strips to fall.

"Hold the horse, my friend," said the young fellow in the brilliant clothes. "Announce to Giovanpaolo that Tizzo is entering."

"Go ask the devil to announce you!" said the guard who had been flicked by the reins.

One of the gentry who lolled under the adjoining olive tree broke into a loud laughter and sat up to watch the brawl.

The guard added: "His Highness, Giovanpaolo, is not to be disturbed."

"Why not?" asked Tizzo, walking straight towards the two guards. Compared with their armor-sheathed bulks he seemed very slender and boyish. The sword at his side appeared to be a foolish vaunt. "Is Giovanpaolo sleeping because he's had too much to drink? If he is, I'll wake him up. Announce me!"

"Announce you?" said the guard who had spoken before. "Your name may be Firebrand, but you give me no warmth. I'm hot enough in the sun without having a fire at hand. Sit down on your heels and wait for the time of His Highness."

There was another loud laugh from the nobleman who lounged under the tree, and who now stood up as though expecting something further to happen.

He said, "Here's a check for Tizzo, at last."

One of his companions answered: "I wager three ducats to one that he gets into the tent."

"The guard will see him damned first," said the first man.

"The guard will be damned himself if he tries to bar the way," said the other. "I put money on Tizzo." Young Tizzo, at this moment, stepped straight to the angry guard and said: "Give me your name so that I can remember you."

"I give my name to my equals," said the guard, "not to wild- headed young forget-me-nots like you."

"Nevertheless, I'll shake hands with you," said Tizzo.

He caught the big, brown hand of the fighting man as he spoke. The latter tried to wrench his sword-arm free but the effort merely served to jerk Tizzo towards the entrance of the tent. Perhaps he tripped the guard as he passed. It was hard to tell exactly what happened, but the fact was that the man-at-arms tumbled flat on his back while Tizzo disappeared suddenly through the tent entrance. The guard, leaping to his feet, started to rush inside in pursuit, but his companion checked him.

"You've made a fool of yourself already," said the companion. "But if you break in on them now, you'll be damned for your folly."

"What do you mean?" asked the first man.

"Why, if you wore ears in your head you ought to have recognized the name. Tizzo is the brightness of which Giovanpaolo is the shadow; he is the warmth in Giovanpaolo's blood, the light in his eyes, the strength of his right hand. Tizzo, fool, is the man who saved the life of Giovanpaolo on the night of the Great Betrayal and got both him and the Lady Beatrice safely out of the city when men were running about like bloodhounds, lapping up the lives of the Baglioni."

"You could have told me what he was," growled the big guard.

"You asked no questions," said the other. "You brought some of your Swiss cheese with you from the Alps, but you left your wits behind you. And this is Italy, man, where brains are better than sword-blades."

"Tizzo? Tizzo?" said the man. "Now I think that I recall the name."

"Pick up the reins of his horse and hold them, then," said the other man-at-arms, "and the name may be willing to recall you."

INSIDE the tent, Tizzo saw Giovanpaolo striding up and down,

his head a little bent towards the depth of his thought. On the

table lay a map. Pieces of armor were stacked on a folding chair.

The whole tent was filled with confusion.

"Ah, Tizzo," said Giovanpaolo, hardly turning his fine head towards the interloper, "what is it now? More brawling? More tavern drinking? More duelling? You have put Gismondo of Urbino to bed for a month with one of your sword tricks; the Spaniard from Naples will never see out of both eyes again, they tell me; and Ugo of Camerino will be a lucky man if he ever recovers the use of his left arm."

"It was only the left arm," said Tizzo, seriously. "I knew that he was a fellow you put a value on, and that was why I did not teach his right arm the sort of manners it ought to know."

Giovanpaolo threw himself wearily back into a chair. He shook his head.

"Is the world always no more than a playground for you?" he asked, sadly. "Here we are shut out of Perugia, half of our friends killed, my own family slaughtered like sheep in the middle of the night, and the army which I am raising to retake the city already muttering and growling because I am slow in giving them pay. The men promised to me by the city of Florence have not appeared. All men begin to doubt my fortune. The sky turns black over me; and still you are dancing, drinking, laughing, fighting day and night without a care in the world."

"I could use some clouds in that same sky," said Tizzo. "Today is too hot for armor. The guards at your door are stewing under their cuirasses in their own sweat; they have turned as mad as hornets and try to sting your own friends."

"I heard them trying to keep you out," smiled Giovanpaolo, "but I knew that they might as well forbid a wild hawk to fly through the blue of heaven. What is it that you want?"

"Time to say farewell to you," said Tizzo.

"Farewell? You?" said Giovanpaolo.

He rose slowly from his chair. "The rest have fallen away from me," he said. "And now you? You are leaving?"

His handsome face darkened with sorrow. But he added, suddenly: "Very well. I can understand. You are too bright a butterfly for these dark days. Go where you please, Tizzo, and God go with you. Here—you will need funds for your journey. Help yourself from these—"

He jerked open the top of a small chest which appeared half filled with gold pieces. Then, stepping to the table, he unfastened a little casket awash inside with points of red and yellow and crystal flames. "Here are the last jewels which the Baglioni could collect," he said. "Fill a pocket with them. God knows you are welcome. If it were not for you, all of us would have died on that night of the Great Betrayal."

Tizzo lifted a handful of the jewels and let them sift slowly through his fingers, showering back into the casket.

"This stuff will do me no good where I am going," he said.

"Where are you going, then?" demanded the other, shortly.

"To hell," said Tizzo.

"Ha?" cried Giovanpaolo.

"To Perugia, I should say," added Tizzo.

"You? To Perugia? Yes, when we take the city by storm. Yes, then you will go to Perugia. But in the meantime even the stones in the streets would cry out 'Tizzo!' and 'Treason!' if they felt the falling of your feet."

"Look!" said Tizzo, and held out a rolled letter which Giovanpaolo pulled open and read aloud:

Friend and Fire-Eater, My Tizzo:

I send you this letter by sure hand. I have already rewarded him, but give him plenty of money when he arrives in honor of a dead man. That is myself.

The days went very well immediately after the Great Betrayal. The wine ran in the gutters, so to speak; the people cheered the murderers of the Baglioni; the traitors sat high in the saddle and they remembered Henry of Melrose with a good many favors and quite a bit of money. I began to feel that I might spend a happy time here except for the stench of murder which rises in my heart when I think of the midnight work which has been done in these streets.

However, when I was about to skim the cream off my cup of fortune and go away with it I was suddenly haled before the chiefs of the Great Betrayal—before Jeronimo della Penna, I mean, and Carlo Barciglia. For Grifone Baglioni is no longer accounted anything. Except for him they never would have taken the place, of course, but since the Great Betrayal conscience has been eating his heart; he has turned yellow and is growing old. Every day he goes to the castle of his lady mother and begs her to let him enter and give him her blessing, and every day the Lady Atlanta bars her doors against him and sends him a curse as a traitor instead of a blessing as a son.

So I was before Jeronimo and Carlo alone, and the information against me was dug up by that double-tongued snake of darkness, that hell-hound of a Mateo Marozzo, who hates you so sweetly and who wears on his forehead the cross which you put there with the point of your dagger. If he remains long out of hell, the chief devil will die of yearning.

It is this Marozzo who discovered that on the night of the Great Betrayal it was through my gate that there passed the Lady Beatrice Baglione, accompanied by the main head and brains of the Baglione family, the famous Giovanpaolo, and that firebrand, the hawk-brained wild man, Tizzo, who had snatched those two lives from the slaughter.

I damned and lied with a vengeance and offered to prove my innocence in single combat with Marozzo, but they have seen my swordwork and they shrank from that idea. In brief, out came two eye-witnesses and I was damned at once, and thrown into prison. Here Jeronimo della Penna is letting me lie while he revolves in his mind a punishment savage enough to be equal to my fault. After that, be sure, I shall die.

In dying, as I run my eyes down the years, I shall see no face more dear to me than that of my young companion who never showed his back to a friend. I shall think of you, Tizzo, as I die. Think of me also, a little, as you live.

Farewell,

Henry of Melrose.

####GIOVAN PAOLO, when he had finished reading the letter, his voice dropping with an honest reverence as he pronounced the last words, remained for a time with his head bent.

"I know the brave Englishman," said he, at last. "I know he has been a bulwark of the house of the Oddi. I have seen him in battle and anyone who has watched the work of his sword can remember him easily enough. I know that it was he who allowed us to pass out of the city on the night of the Betrayal. I would give all the jewels and the gold in this place and all I could send for in order to set him free. But that would not help him. Money will not buy a man out of the cruel hands of Jeronimo della Penna. And what can you do, or any other man? We can only pray that we may storm the city and set him free before Jeronimo makes up his mind what form of torment he will use on Melrose."

"I must go to him," answered Tizzo.

"Listen to me," urged Giovanpaolo. "How can one man help him?"

"The man who brought me the letter is an assistant jailer. I've bribed him with a fine sum of money. He is going to meet me in Perugia and admit me to the house of Jeronimo, where Melrose lies in one of the great cellars. He will furnish me with a file to cut through the manacles. After that, I must try to get Melrose away."

"How will you take him out of the city? Will you use wings?"

"Chance," said Tizzo. "I've worshipped her so long with dice, I've made so many sacrifices in her name, that she would not have the heart to refuse me a single request like this one."

"Tizzo—tell me in brief. What is Melrose to you? He is brave; he has an eye which is the same flame-blue as yours in a fight; he is true to his friends. I grant all that. But other men have the same qualities."

"Paolo," said Tizzo, "you and I have sworn to be true to one another. We have sworn to be blood brothers without the blood."

"That is right," nodded Giovanpaolo.

"Well, then," said Tizzo, "if I heard that you were lying in prison, expecting death, my heart would be stirred no more than when I hear that the Englishman is rotting in misery in the dungeon of della Penna."

Giovanpaolo, after this, merely made a mute gesture and argued no more.

"Beatrice is in the inner tent," he said. "You will want to say farewell to her?"

"No," answered Tizzo. "If I see her, I'll fall out of this resolution of mine and be in love with life again. Tell her so after I have gone."

"I shall tell her," said Giovanpaolo. "What is your plan?"

"Simply to enter the city and go to the house of a certain Alberto Marignello, in the little lane off the via dei Bardi. This Marignello is the fellow I have given the money to, the one with the keys to the cellars of della Penna. When I have the keys—why, you see that I'll not know the next step until I come to take it."

"Tizzo, you are a dead man!"

"I am," said Tizzo, cheerfully, "and that is why I have come to say farewell!"

He held out his hands, and Giovanpaolo, with a groan but with no further protest, held out his hands to make that silent farewell.

THE green, the orange, the yellow and the crimson no longer

flashed on the body of Tizzo when he came near Perugia in the

twilight of that day. His skin, rather fairer than that of most

Italians, had been darkened with the walnut stain which he had

used on the night of the Great Betrayal, and his red hair,

darkened also, tumbled unkempt about his face. His clothes were

ragged; his back was bowed under a great fagot of olive wood to

which was lashed a heavy woodsman's ax. In the full light of the

day a curious eye might have been interested in the blue sheen of

the blade of that ax, but in the half-light of the evening the

glimmer of the pure Damascus steel could not be noticed.

When he came to the gate, a pair of fine young riders were being questioned by the captain on duty there, but none of the guards paid the slightest attention to that bowed form under the heavy load of wood. A young lad inside the gate bawled: "Look! Look at the donkey walking on two legs!"

In fact, hardly the poorest man in Perugia would have carried such a crushing burden of wood on his back into the town, but Tizzo, with a hanging head and a slight sway from side to side of his entire body, strode gradually up the steep slope of the street. He turned right and left again before he came to the wide façade of the great house in which lived Atlanta Baglione, the mother of the traitor to his house. Grifone.

In the dusk, he came to the entrance of the courtyard, where the porter merely sang out: "What's this?"

"A broken back and a load of olive wood," said Tizzo. "Where shall I leave the stuff?"

He made as if to drop it to the pavement but the porter cursed him for a lout. "D'you wish to litter the street and give me extra work?" he demanded. "Get in through the court and I'll open the inner door."

He led the way, but stopped suddenly as he saw the form of a man kneeling on the farther side of the court under a shuttered window, crying out, not over-loud: "Mother, whatever I have done, I have repented. If I have sinned against God, he will have his own vengeance. If I have sinned against men, my heart is already broken. But if you turn a deaf ear to me, the devils in hell are laughing!"

"So!" muttered the porter. "Always the same! Always the same! But she is the sort of pale steel that will not bend. This way, woodcutter."

He led through a doorway, but as he was about to close the door, the man who cried out in the corner of the courtyard rose and rushed to enter behind the burden-bearer. A streak of light from a window flashed dimly across his face and Tizzo recognized the most handsome features of Perugia, the richest of her sons, the pride and the boast of all her youth, Grifone. He was a great deal altered. Even in that faint glimpse, Tizzo could see the pale, hollow face. Then the door slammed heavily and shut out the vision.

"So! So!" panted the porter. "God forgive him for his sins; God forgive my lady for shutting him away; and God forgive me that I have seen such things in my life!"

He showed Tizzo where to carry the wood into a storeroom, and locked the door behind him.

"And now for the payment," said Tizzo, standing straight with a groan. "I have brought twenty backloads of that wood, now, and I need the money for it, friend."

He leaned on the handle of the ax and wiped sweat from his face.

"You want money? There is not a penny ever paid out in this household except by my lady," said the porter. "Do you want me to break in on her now?"

"Brother," said Tizzo, "there is neither flour nor oil in my house, to say nothing of wine, and I have to walk a league to come to my place."

"Have you carried that backload three miles?" asked the porter.

"Yes," said Tizzo, truthfully.

"Well," murmured the porter, "I shall see what can be done. It is very late, but the lady is kind as milk to every man except to her poor son."

HE left Tizzo standing, leaning against the wall, and finally

ran down some stairs and told Tizzo to follow him. "She will see

you. But this is a strange thing—that she knows everything

and yet she does not know of any twenty backloads of wood of the

olive. Well, we shall see."

He took Tizzo up the stairs and brought him into a little square anteroom where a table was piled with neatly arranged papers of account.

A moment later the lady of the house entered. The Lady Atlanta wore the black of deep mourning with double bands of blackness as though for two deaths. To be sure, her husband had been dead ever since the infancy of her son; she had never married in the interval because she had kept one memory sacred although her great wealth had tempted a number of famous suitors; and now it was plain that she mourned for Grifone, her son, as though he were dead also.

This darkness of the clothes made her face marble. Her brow was as clear as stone, her eyes were unmarked by time, and she wore that faint smile which Greek sculptors knew and loved. At first glance she seemed still in her twenties. In fact, she was not yet forty years of age.

She took her place at once behind the table, sitting straight in a backless chair and resting on the edge of the table a hand of wonderful youth and delicacy of outline.

"Your name?" she said.

"Andrea," said Tizzo, bowing until his shaggy hair almost touched the floor. "Andrea the son of Andrea the son of Andrea, the son of Luigi of the millside near the village of La Pietra."

"Andrea," said she, "you claim the payment for twenty backloads of olive wood?"

"I do," said Tizzo, bowing again.

"I have no record of ordering this fuel, my poor friend," said the lady.

"I carry the order with me," said Tizzo.

"You carry it with you?"

"Yes, my lady."

"In writing?"

"In token," said Tizzo.

He shifted the ax which he still held and drew from his breast on a slender string something which he held in the hollow of his palm so that porter could not see it but the lady could. What she saw was a broken ring.

She saw, also, the sudden flash of meaning in eyes too bright, too flame-blue for the darkness of the skin and the hair.

She saw this, and instantly looked down at the floor.

"Go to Fortinacci the steward," she said to the porter, "and ask him what he knows about this affair of Andrea the son of Andrea the son of Andrea. I will talk to Andrea in the meantime."

The porter disappeared, and Lady Atlanta rose at once.

"What is the ring?" she asked.

Tizzo, with his grimy fingers, laid it at once in the white palm of her hand and she bent over it curiously. She started straight again, suddenly. There was a wide incredulity in her eyes as she said: "It is one half of a broken signet ring of Giovanpaolo Baglione!"

"The other half," said Tizzo, "is worn about his neck."

"In sign of what?" she asked.

"In sign that we are sworn brothers," said Tizzo.

THE Lady Atlanta, looking with her cold, steady eyes into the face of the stranger, said to him, suddenly: "You are the red-haired man, the firebrand; you are that Tizzo—and yet you cannot be he! Hair may be stained and skin darkened, but Tizzo is a man who can cleave a thick jousting helmet with one stroke of his ax—" Here her eye ran down along the arm and the hand of Tizzo to the blue, shimmering blade of his ax.

"Ah, it is true!" she murmured. She smiled with a radiance that made her young as a girl.

She hurried to the door and slid the bolt, whispering: "What is there that I may do? I know that you saved two sacred lives of my family. Now you are risking your head again by entering Perugia. Tizzo, you had better walk into a flaming furnace than into this town!"

"Withdraw the bolt, madame," said Tizzo. "If you honor me with a private interview, even that is enough to make men look at me, and if they look at me twice, I shall be discovered."

"True!" she said, and drew out the bolt again, instantly. "But what is there that I can do, Tizzo? Tell me how I can aid you? Whatever purpose brought you to Perugia, I shall make it my purpose!"

"My purpose," said he, "is to rescue a friend from his prison in the cellars of della Penna."

"With how many men are you to attack the house?"

"With my two hands and this ax," he said, smiling. "It is not force that will save my friend. The only thing that will unlock the bolts of della Penna's house is chance and a little bribery. I am using both."

"Tizzo, the chance is dreadfully slight. And if they capture you, your head will be on a pike before morning!"

"The chance is very small," he admitted. "There is a better and a surer way of saving my friend: beating open the gates of Perugia and restoring the city to its rightful rulers."

"Tell me what way!" she demanded, eagerly.

"You have the means in your own hands. The agent is now in your courtyard calling out on your name and begging you to let him speak to you. Your son Grifone is trusted with half the charge of the walls. He could open the gates easily, and allow the soldiers of Giovanpaolo to enter the town."

"Since Judas," she said, "there never has been such a traitor as Grifone Baglione!"

"He is your own son!" said Tizzo.

"I forswear my claim on him. He is a changeling. My true son was stolen out of my bed and a murderer's brat was placed on my breast."

"My lady, if ever the same blood showed in two faces, it is in you and his highness, Grifone."

"It cannot be," she said. "Or if I have had a share in the making of his body, I have had none in the forming of his heart. In his own house—at midnight—with his own hand he gave the signal for the butchery—and he led the way— Ah, God, when I gave him birth, what a curse I brought upon my poor Perugia!"

"My lady," said Tizzo, "he was very young; he was tempted by a great jealousy."

"Of whom?"

"He suspected Giovanpaolo with his wife."

"His wife is a sacred saint, and Giovanpaolo is the noblest of men! Tizzo, only curs hate the truly noble! And Grifone may whine like a dog in the courtyard. I never shall see him!"

"One word from you, and he would throw himself on the side of Giovanpaolo."

"Giovanpaolo would not have the traitor's aid—not for the price of two cities, each twice greater than Perugia."

"My lady, it is true that Giovanpaolo would never forgive him, but if Grifone will restore the Baglioni to their own, then a peace can be made between them. His Highness, Grifone, can withdraw with all his possessions to another place. And time may partly close the breach between them."

"Death alone can close it!" said the Lady Atlanta.

"Madame, I beg you to think—it is in your power to restore the Baglioni to Perugia."

"It is the dearest wish of my soul, but shame would keep Grifone from lifting a hand to help the men he has wronged."

"Be sure that his heart is suffering. There is torture in his face. A word from him will make him repent everything and strive to make amends to all the people of his blood."

"Tizzo, I have sworn a great and sacred oath never to look on his face, never to speak to him, never to listen to his voice. If I hear him crying out under my window, I run to another room and stop my ears."

"An oath which is wrong should not be maintained. Every priest will grant you absolution for breaking it."

"I did not swear it with thin breath; I swore it with my heart and soul."

TIZZO, for a moment, regarded the beauty, the terrible anger

in her face. And he knew that persuasion would be impossible.

"Then I kiss your hand and leave you, my lady," he said.

She retained his hand in both of hers, the fierce passion dying gradually out of her eyes.

"But you, Tizzo," she said. "I know what you have done. I know by words, and also, I saw that great jousting helmet cloven to the bottom by your ax-stroke. There is not strength in your hands for such a feat and therefore it must be a strength in your heart. Trust me, that if I know any manner in which I may aid you and help you, I am at your service. There is money here—or jewels which have a greater price—will you have them?" She actually stripped the rich rings from her fingers. But Tizzo shook his head.

"There are men in this house whom I could trust to support you in anything."

"No, my lady," said Tizzo. "I have had enough money for my purpose. More would only be a weight in my pocket. And as for men, the thing I have to do is better and more easily managed by one hand than by twenty. Secrecy has to be the point of the sword for me now."

"Must I feel that my hands are empty to help you?" she exclaimed.

"No, my lady. I shall remember you when I come to the time of need, and that will make me stronger."

"You will go on this wild enterprise, Tizzo?"

"I must go, at once."

"Tell me what service I can do, other than this, for Giovanpaolo and his men?"

"Send to my friend, Antonio Bardi, and tell him that Giovanpaolo forgives the part he played in the Great Betrayal. At least, Bardi did no murder on that night."

"How can Giovanpaolo forgive a single soul who took part in the Great Betrayal?"

"Because he is as wise as he is brave. My lady, send for Bardi. Tell him he is forgiven if he wishes to strike a blow on our side. Send, also, for my foster father, Luigi Falcone. He has taken no stand on either side. But he will ride and fight for me. Those two men inside the city, if they will meet in your house and lay their plans together, may be strong enough to open Perugia to the attack of Giovanpaolo. Farewell!"

"Farewell, noble Tizzo!" said the Lady Atlanta. "If I were a man, I would go at your side, tonight!"

IT was easy enough for Tizzo to get down the stairway and out

into the courtyard, unobserved.

The court was empty. A thunderstorm was rolling over the city, lighting up its towers and mountain-ranges of clouds with long ripplings of cataracting lightning. Brief, rattling showers raised a pungent odor of dust in the air, and scurried the people out of the streets, as Tizzo turned away from the great, unhappy house of the Lady Atlanta.

He had never seen, he was sure, a lady so beautiful. Not the young and lovely wife of Grifone, even, was so like an immortal. Compared with such majesty and purity of features, the Lady Beatrice was a mere tomboy.

She was a mere prettiness, in contrast. But then it was her spirit that set the hearts of men burning.

Thinking of her, Tizzo turned into the via dei Bardi and there forgot everything except his purpose. From the street of the Bardi, he turned into the alley that branched off from it, crooked and downhill as the course of a stream; and the lofty, irregular front of the houses might well have been a canyon which the running water had worked out of the living rock.

The house of Alberto Marignello had been well described to him. He found it almost at once and was about to cross the street towards it when a slender youth, wrapped in a cloak to defy the rain, said to him: "Tizzo, there have been many men there before you!"

He turned with a half groan of bewilderment and fear. "Beatrice," he whispered, "in the name of what god have you come to Perugia tonight?"

SHE stood back with one elbow leaning against the wall, her hat pulled half down across her forehead, her legs crossed, her whole attitude one of super-boyish impudence and mirth. He had seen her so often in man's clothes, she was so certain to slip into them whenever there was an emergency of importance, that his quickest memory of her was not in dresses at all. She was saying:— "I came to Perugia in the name of the great god of the fire, in the name of the firebrand; I came for Tizzo. Does that answer please you, my most noble lord?"

Beatrice

"Beatrice, listen to me—"

"If you talk so earnestly, people will notice you. If they look at you twice, they'll soon have you clapped into a fire to burn in good earnest, Messer Firebrand."

"They will find you in the town. They will surely recognize you, Beatrice. And if they get their hands on you—"

"They don't murder women," said Beatrice. "Not even in Perugia."

"They'll do worse. They'll marry you to one of their brutal selves for the sake of your estate."

"And then comes noble Sir Tizzo and runs my false husband through the gizzard and makes me a widow today and a new wife tomorrow. You see, I risk very little. No matter what road the story starts away on, it will wind up with Beatrice and Tizzo hand in hand at the close."

"My God, how wild, how foolish, and how charming you are," said Tizzo. "Giovanpaolo should not have told you where I had gone."

"I pulled the story out of him like so many teeth. Tizzo, you would sneak away and let yourself be killed? Sneak away without a word of farewell to me?"

"I had not the courage to face you."

"When I knew you were gone, I was empty," she said. "I felt, suddenly, as though you had never kissed me, as though you had never said you loved me. I felt as though danger were another woman, and you had gone to her. So I had to come here and meet you in the street."

"You must go instantly from the city."

"With you, Tizzo, I would go anywhere."

"I cannot go with you farther than the walls."

"Then I shall not leave Perugia."

"Beatrice, I beg you—if you love me—"

"I only love the man who lets me share his dangers," she said.

"I will take you to the walls and see you safely away."

"I shall not go unless you come with me."

He groaned.

And then he said: "The work which lies before me is something I cannot turn my back on."

"Your work is spoiled before it commenced," she said.

"Why?"

"I've lingered up and down this street, and I've seen half a dozen men enter that building."

"Why not? More than one family lives in it."

"Men in cloaks, with something under the cloaks."

"Bread from the baker, perhaps."

"Bread or steel ground sharp along two edges, more likely," she said.

"Marignello has been paid his price. He would not betray me."

"Perhaps he could get a greater price from della Penna."

"He would not dare to confess that he had been in touch with me."

"No? He would simply say that, from the first, he had been attempting to draw you into a trap."

"There is not that degree of guile in him."

"Tizzo, for all your cleverness—and I know you are not a fool—you continue to think that men are as honest as yourself. And that is a folly. Why, Tizzo, every man in Perugia knows that Mateo Marozzo, for instance, would pay all the gold in his treasury for the sake of one chance to drive a knife into your body!"

"Marozzo hates me. They all hate me, now. But I must count on Marignello. Without him, I have no hope. And that means that Melrose has to die without a hand lifted to save him."

"Henry of Melrose," she said, "has followed adventure all his life. He could never expect to die peacefully. Let him have the end that he has invited."

"I cannot, Beatrice."

"Will not, you should say."

"I love you, Beatrice; but even you hardly stir my blood and draw my soul from me so much as that wild Englishman."

"He taught you half a dozen tricks of fencing, and therefore you love him."

"There is something more than that," said Tizzo, frowning. "Long ago, when I saw him, suddenly I had to follow him. I left the inheritance of a great house and a huge fortune for the sake of tagging about the world at his heels."

"Perhaps he used a charm on you?"

Tizzo crossed himself and murmured: "God forbid! But I must go forward in this."

"You mean that you will surely enter that house?"

"Most surely I shall."

"Well, then, I shall show you one thing first," said the girl.

Before he could stop her, she was half way across the street, and he saw her pass straight through the door of the tall house. As she opened the door, he had a glimpse of a dull light and suddenly reaching hands. He saw a flash of naked steel here and there in the background.

He ran like a deer to the rescue but the door slammed heavily; he arrived at it only in time to hear the clank of the heavy iron bolt rammed home into a stone socket.

TO beat against the door with his ax would simply be a folly.

He ran to the left into a meager alley hardly the width of a

man's body and saw, high above his head, the glimmer of a light

through a barred window.

Springing up as high as possible, he was barely able to hook the lower edge of the ax over the sill of the window. Then he drew himself up into the casement and curled into the embrasure. Through the bars of the window he found himself looking down into a large room with a fire flickering on a deep hearth and a mist of woodsmoke in the air. And in the midst of the room stood a full dozen of men clustered about the Lady Beatrice, holding her fast by the arms.

Alberto Marignello stood before her, his rather handsome but heavy face darkened by a scowl.

"Now, my lad," he was saying, "explain why you open the door of a place where you have never been seen before?"

"I come here because I bring a message."

"What sort of a message?"

"A brief one," said the girl.

"From whom?"

"From a man I met outside the gate of San Ercolano."

"Well, what sort of a man?"

"A young man with red hair."

"Ah, ha!" said Marignello. "Young—with red hair, and blue eyes that never stop shining?"

"Yes, that is he."

"You see?" said Marignello. "She has seen that Tizzo—that blue-eyed devil of a Tizzo! Well, and what message did he give you?"

"To come here and find a man called Alberto Marignello."

"That is my name."

"Well, then I'm to tell you that he cannot come tonight."

"Ah, he cannot come?"

"No."

"Will he come tomorrow?"

"Tomorrow after dark, if you will come out to the camp of Giovanpaolo and arrange a second meeting place."

"I go again into the jaws of the lion?" said Marignello. "I am not such a fool."

"That was the message. And then I come here," said Beatrice, angrily, "and you all leap at me like dogs at a bone."

It seemed a miracle to the watcher at the window that they should not see, at once, that she was no boy at all. The beauty and the dignity of the Baglioni was in her face in spite of her rough clothes. And in her voice there was a strange sweetness that should have undeceived them at once, he thought. But in that voice there was also a huskiness, and it was true that she looked slender and small enough to have passed for a boy at the turning point towards youth.

A strangeness came into the mind of Tizzo. He half wanted to shout: "Fools! You have in your hands the greatest prize, bar one, that you could ask for. You have the sister of Giovanpaolo. With her in your hands, you are safe, and Giovanpaolo himself will not dare to attack the city—not if he had a million armed men behind him!" And again, with his bare hands, he wanted to tear at the iron bars and wrench them from their stone sockets and plunge into the room.

HERE a great booming of thunder began, one of those

cataracting sounds which pour over heaven like a cart over a

brazen bridge. Inserting the stout oaken haft of the ax between

the bars, he bore down with all his strength. Something gave. It

was not the stone socket, but the soft iron itself bent, and so

was pulled loose. With his hand he was able to draw it away from

the socket.

As the uproar of the thunder died down, one of the men said: "This story that the boy tells is all very smooth and well. But I wish to ask when he passed through the gate at San Ercolano?"

"Oh, half an hour ago," said the Lady Beatrice.

The fellow who had asked the question turned with a sudden grin on his companions. He threw out his hand to make an important gesture. Then he said: "It was less than a half hour ago that I passed near San Ercolano and found out that the gate had not been opened during the entire afternoon."

"The small portal in the gate was open, however," said Beatrice, and the heart of Tizzo stood still as he listened.

"The portal was not opened!" shouted the fellow who had last spoken. He had a broad, brutal face and Tizzo swore that he would never forget that countenance.

"The portal was not opened. The entire guard was taken from the gate at noon! At noon, mind you! And the boy lies!"

"Ah, ha," said Marignello. "Is that the way of it? Now, he looks capable of a good lie, when I look at him again. His face is a little too fine for those clothes. Give me your hand, boy!"

Beatrice held out her hand, and Marignello leaned over it. Suddenly he threw it to one side. He exclaimed: "It is soft as the hand of a woman! This fellow never has done a stroke of work! What has your labor been, eh?"

"I've been a tailor's apprentice," said Beatrice, instantly.

"Ha? So! Well that may be, too," said Marignello, half convinced by this remark.

"No tailor's apprentice ever stood so straight," said another. "From sitting cross-legged, their shoulders begin to stoop before they're twelve years old."

"Aye, and their chins stick out in front."

"Aye, and they squint!"

These remarks came in a general murmur. The thunder rolled heavily again, and Tizzo used that noise to cover the wrenching jerk with which he pried loose a second bar. Another pair, and he would have opened a sufficient space to admit his body. After that, if once he got down into that room with his ax—well, they would have something to think about other than this "boy" they were questioning.

"You are not a tailor's apprentice," said Marignello, pointing to her hand. "See, there is no enlargement of the thumb and the forefinger of the right hand, and the left forefinger is not stuck full of the little scars of the needle point. Confess that you have lied."

"I was ill for six months and the scars wore away from my skin," said Beatrice Baglione.

"I never saw a tailor," said Marignello, "who dared to look people straight in the eyes in the manner of this lad. He holds up his chin in the manner of one who has told servants to come and to go. Come—the signore will be here in a little while, and then we may learn something more about this lad."

It was only another moment, in fact, when a knock came distinctly at the street door.

"Shall I open?" asked one of the men.

"No, not till I have spoken," said Marignello.

He approached the door and called out: "Who is there?"

The answer was indistinguishable to Tizzo, but Marignello called again: "What word has passed between us?"

He paused for the answer and then said to the other: "This is right. He has named the word which he and I alone know. It is the signore."

He then unbarred the door and there entered a man in a scarlet cloak whose collar was wrapped up high about the head and face in order to shut off the rain.

He threw back this cloak and revealed himself in a fine doublet and costly hose that had a silken sheen. He had a colored handkerchief thrust inside his belt and carried a dagger as well as a sword. His soft hat was of blue velvet, and it was pulled low over his forehead. In spite of this, the silver gleam of a scar appeared just above the center of the forehead and looked like a streak of grease. Tizzo recognized his own handiwork. With the point of his dagger he had drawn a cross into the flesh of Mateo Marozzo, the point of the sharp steel shuddering against the bone. This man he had branded for life, and it was a deed which he looked back upon only with pleasure. He wished, now, that he had driven the dagger through the fellow's heart.

Marignello said: "We have caught a queer lad here, who says that he's a tailor's apprentice. But he hasn't that look. He says that he carries a message from Tizzo. Will your lordship look at him?"

Marozzo approached the Lady Beatrice and stared full in her face.

Then he said: "This is, in fact, a very queer—lad! Marignella, take yourself and your men away. Let me have plenty of time alone with this—lad. And I may make something of him!"

MARIGNELLO got quickly out of the room, the slamming of the door behind him and his companions being quite covered by an immense, crashing downpour of the rain. In that uproar, Tizzo managed to work the other bars from the sockets. He had plenty of room, now, to slip through the window, but his position was frightfully complicated. If he leaped down, the ten foot drop to the floor from that high casement probably would send him sprawling, and before he could rise the dagger of Marozzo would be in his back. He waited, the corners of his mouth jerking with eagerness.

He could hear Marozzo, now, saying: "Dangerous, beautiful—most beautiful, most dangerous, Lady Beatrice! Can I tell you how welcome you are to me?"

"My dear Mateo," said the girl, "I ought to be welcome to you. You can make a very neat sum of money out of me, I suppose."

"Money?" said Marozzo. "Do you think that we will sell you? No, sweetheart, you will never leave Perugia, and so long as you are inside the city the hands of Giovanpaolo are tied. He cannot strike at us for fear we may strike at you. You mean more than money to all of us. You mean life, Beatrice, life!"

He began to laugh, putting his face close to hers, jeering.

"And the handsome fellow with the red hair—the firebrand—Tizzo—I suppose it was he who drew you into this crazy adventure, my lady? Your reputation—what is that to a man whose brain is all in a flame? Such a bright flame that the pretty little moths, the charming, delicate Beatrices, are always flying into the fire!"

"Mateo," she answered, "Tizzo has nothing to do with this."

"Certainly not. You didn't even know that he was expected here this evening? You were merely walking up the street by chance? You merely happened to walk through this door? Certainly Tizzo could have nothing to do with it!"

She took a deep, quick breath and looked fixedly at Marozzo.

"Mateo, you can make a fortune, a great fortune, if you'll see me out of the city."

"If an angel came down and offered me a throne in heaven for returning you to your brother, I would never do it!" said Marozzo.

"No," she said, slowly, "I think you mean that!"

"I mean it with all my heart. We are leaving the house now, my lady!"

"To cheat your friend Marignello of his share in the reward? There is as much fox as dog in you, Mateo," she said.

And Marozzo, overwhelmed with a sudden frenzy of hate, flicked the tips of his fingers across her face.

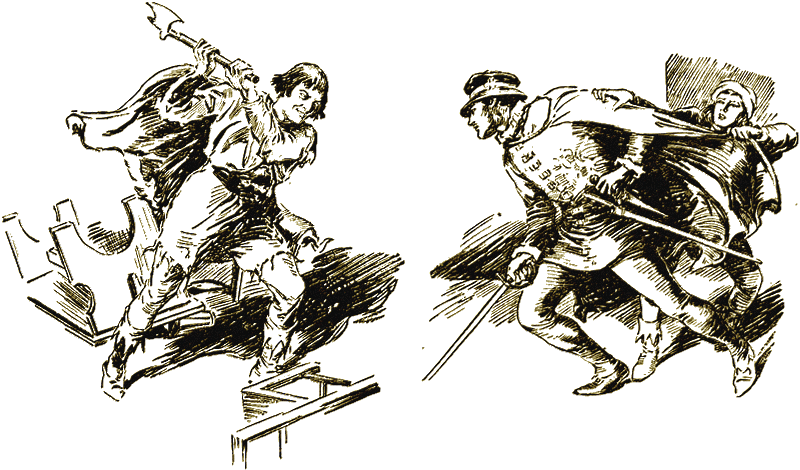

IT was not thought that governed Tizzo. Far better for him to

have slipped back down to the street and waited for Marozzo and

his prize in the darkness of the narrow way. But he could not

resist the lightning impulse which overcame him when he saw the

girl struck. He slid through the window and dropped to the floor,

and his foot, striking a wet spot on the tiles, shot him headlong

on the slippery pavement.

He was already half twisting to his feet when he saw Marozzo running in at him with a levelled sword. An agony of quick fear had turned the face of Mateo white and pulled his mouth into a horrible grin; an agony of joy at this golden opportunity set his eyes blazing. He might have brought a dozen men swarming by a single cry, but that conflict of his emotions seemed to have throttled him. Or perhaps he saw, in this gleaming instant, a chance to accomplish a double deed—the capture of Lady Beatrice and the death of Tizzo. Such a thing would make him a hero forever among the powers who then ruled the city of Perugia. He would be, at once, among the great ones.

So he sprang at Tizzo, the sword shooting out before him for the death stroke. It came with such speed that there was no avoiding it, but Beatrice caught at the backward flaring cloak of Marozzo with such strength that he was checked and jerked a little to the side. That gave Tizzo the fraction of a moment he needed for rising to his feet. The head of the ax, light as gilded paper in the practiced grasp of his hands, struck aside the next thrust. He was in no position to use the edge of the ax for a counterstroke. Instead, he drove the butt of the haft between the eyes of Marozzo and snatched the sword as it fell from the unnerved hand.

In that fraction of a second, Tizzo was on his feet.

Marozzo fell in a heap, not utterly unconscious but still struggling to recover himself. To Tizzo the miracle was that a yell of alarm had not roused the house before this.

"Quick! Quick, Tizzo!" gasped Lady Beatrice, already at the street door.

"Go in the name of God," he commanded. "Go to the house of Lady Atlanta and she will shield you. I have one more thing to attempt here."

With a twist of cloth he was tying the hands of Marozzo behind his back. Then he drew the little poniard from the side of Marozzo and flashed it before his eyes.

"If you mark me again like a branded beast—" groaned Marozzo. "Kill me outright, Tizzo. Ah, God, to think that I had you so close to the point of my sword!"

"A greater miracle is going to happen," said Tizzo. "You will have a chance for your life if you listen to me! Beatrice, will you go? Will you go? Are you staying here to drive me mad? Slip away! Swift, to the house of the lady, and she will help you from the city."

The girl stepped to the table and sat down on the edge of it, swinging one small foot.

"I stay here," she said. "I haven't had so many chances of seeing you at work, Tizzo."

He glared at her, baffled.

"There is still danger!" he insisted. "There is a frightful danger—I beg you with the blood of my heart—go at once!"

"While you stay here?" said the girl. "No, I stay where you stay. Save your breath. You can't persuade me to leave you."

He glared at her once more, half enraged, half desperate. Then he turned back to Marozzo.

"Stand up!" he commanded, and Marozzo rose. His eyes saw one thing only, the deadly splinter of steel, the almost invisible needle point of the poniard which was at his breast.

"Step to the door," said Tizzo, and led his captive there.

He pulled that door a trifle ajar and ordered: "Call to Marignello and tell him to send all his companions away. Tell him you have learned something that is only for his ears and yours. In a hearty, happy voice, Marozzo, or by St. Stephen you'll have something sharper than arrows in your heart!"

"I'll be no tool of yours!" panted Marozzo. "Stab me, then; but I'll not do your work for you! The day is cursed that first saw you!"

"Ah, Mateo, do you invite me?" asked Tizzo through his teeth. "Don't you see, Marozzo, that wild horses are drawing me forward to your slaughter, you jackal? But do as I tell you and I give back your dirty life. You hear?"

In that moment of shame and surrender, Marozzo glanced towards the girl and found her hard, cruel eyes fixed upon him. His head dropped.

"Make up your mind," said Tizzo. "Will you call to Marignello? Heartily?"

"Yes," said Marozzo.

His head jerked back. His eyes were half closed, and suddenly he shouted to the full of his lungs: "Marignello! Help! Hel—"

The point of Tizzo's dagger could have stifled the first word of that cry, but he could not strike it into a defenseless throat. His whole heart yearned to kill the traitor, and still he could not use the edge of the dagger. Instead, he jerked it about and struck with the pommel once, twice, and again into the midst of that still beautiful face.

A smashed red ruin took the place of a face. Marozzo slid through the arms of Tizzo like a figure of sand and lay helpless on the floor.

"Tizzo, they are coming!" panted the girl.

"They are," he admitted. "But I can't leave. There's still a chance. I must get from Marignello the keys that he holds—Beatrice, for the last time—will you run for your life?"

A tumult of many footfalls came hurrying, and Tizzo barred the inner door against that influx.

"Signore Marozzo? Your highness?" Marignello was calling out anxiously as he came.

And then a light and silver sound of laughter chimed in the room, making Tizzo jerk his head suddenly about. It was the Lady Beatrice, with her head tilted back, now crying out: "Your highness—Signore Marozzo—how can I help laughing—"

The inner door was shaken.

"Your highness—did you call to me?"

"Yes, for wine," said Lady Beatrice. "I'll unbar the door for you, Marignello—"

She looked fixedly at Tizzo and walked up to the door. He, understanding suddenly, dragged the fallen body of Marozzo aside and placed himself where the door would cover him as it swung open.

There he waited. A crack of light struck in on him as he stood there while the door swung wide under the hands of the girl.

"Only you, Marignello," she said, still laughing. "There is a secret, here, and you are the only man his highness will admit to it. Step in!"

"A secret? I thought I heard a yell for help—" began Marignello, as he stepped through the door.

The girl shut and barred it instantly behind him.

"But where is Signore Marozzo—" began Marignello. It was only then that he saw the gleam of the poised ax in the hand of Tizzo. He made no effort to leap back. There was not a man in Perugia who did not know the singular and deadly magic which Tizzo could work with that weapon.

"Tie his hands," said Tizzo softly, to the girl.

It was done instantly.

"Is there a rear door out of the house?" whispered Tizzo to the stricken Marignello.

The eyes of the man dropped to the still figure of Marozzo on the floor.

"You still have a chance for life," promised Tizzo, "but only if you lend us your help."

"May I live? Oh, God, is it possible that you give me my life?" breathed Marignello. "There is, my lord. There is a door at the back of the house."

"Then tell all those fellows of yours to leave the place by that door—to return here tomorrow at the same time. Sing out in a hearty voice. You hear me?"

Marignello nodded. His eyes blinked. Twice he moistened his lips and took deep breaths, before he called out in a ringing tone: "It's finished for tonight. Paolo—Guido—all of you out the back way; I have to confer here with his highness."

"This is all too damned strange," said a heavy, growling voice beyond the door.

Marignello looked down again at the limp figure, the blood- dripping face of Marozzo, and shuddered.

"Orders from his highness," he said. "We've found wonders in the boy—and tomorrow night, my lads! At the same hour. We'll have the trap and we'll have the Tizzo to catch in it, and double pay for all."

There was still a little murmuring, but presently the footfalls began to withdraw. The knees of Marignello were bending under his weight, and the cold burden of fear.

"Be brave, Marignello," said Tizzo. "I have made a promise. Fill your part of the bargain, and you shall live, I swear."

"God and your highness forgive me for treachery!" groaned Marignello. "But they offered me a fortune, a treasure of gold! They hate you so, and they fear you so, that they would buy your death with your own weight in gold. Yes, they would make a statue of you all in precious metals and set jewels in the head of it for eyes. They would give that away to make sure of your death!"

"I understand," said Tizzo.

The girl had gone to the street door and was listening, but the crashing of the rain muffled all other sounds outside the house. Small gusts of wind worked down the chimney and knocked puffs of smoke out into the room.

"But you have, somewhere in the house, keys that fit doors in the prison cellars of della Penna," said Tizzo. "You were not lying when you told me that you were a trusted man?"

"I was not, signore. No, no, I am a trusted man—and God forgive me for once betraying my trust! There are three sets of the keys, one in the hands of his highness, Jeronimo della Penna, and the head jailer keeps one—he never leaves the house; and I have a smaller set."

"What will your smaller set open? The outer door of the cellars?"

"Yes, signore."

"Marignello, you will still be a treasure to me!—Where are those keys?"

"They are at the key-maker's."

"Ha?"

"His Highness, Jeronimo della Penna, ordered me to have my set copied."

Tizzo groaned, but the girl, turning from the door, said: "He lies, Tizzo."

"Why do you think so?"

"Three sets of keys to one dungeon—that is more than enough. If Jeronimo used all the wits he possesses, he would never have so many. Besides, would he trust such keys into common hands? Into the hands of a keymaker, who might make ten sets as easily as one?"

"True!" exclaimed Tizzo. He turned sharply on Marignello, who cowered as though he expected death to strike him that instant.

"You have lied, Marignello?" he demanded.

"Ah, my lord, consider! For these years I never have broken my trust to my master! How can I break it now?"

"You were bribed by Henry of Melrose."

"No, signore. I took his money, but then I carried the letter to my master. He read it through and told me to deliver it—and keep the bribe. You see, I tried to be honest."

"I think you have," said Tizzo, with a queer turning of his heart. "As well as you could, you've tried. You've tried to betray me and trap me—but I suppose that money can buy outright a conscience like yours. But now, Marignello, make up your mind. Will you give me the keys or will you not? Will you give them to me, or will you die here?"

"They are in that closed cupboard at the corner of the room," sighed Marignello.

Beatrice was instantly at the place, and when she had pulled the door open she drew out from one of the inner shelves a bunch of keys which were dark with rust in places but polished with use in others.

"Are these the ones, Marignello?" she asked.

"They are," said Marignello, sinking his head. "And I am a ruined man forever!"

"You have made a fortune out of your treachery," said Tizzo. "Why not leave Perugia, then, and spend your money in another place?"

"Because wine in other cities has no taste, and bread in another place will not fill the belly. Except in Perugia there is no good air for breathing; in other places, the men are fools and the women are foul," said Marignello, mournfully.

A deep sigh from Marozzo, at this moment, called attention back to him, and Beatrice stooped above his body.

"Now for the keys," said Tizzo. "One by one—slowly—here, I draw a diagram on the floor as you name me the rooms and the passages, one by one. Now, begin!"

THEY left Marozzo and Marignello lashed hand and foot, converted into two lifeless hulks which were rendered silent with strong gags. The cloak and the hat of Marignello were taken by Tizzo. That of Marozzo would shelter Beatrice from the rain.

And now, with the ax under the folds of the cloak, Tizzo stood beside the girl in the street. The eaves above them shut away most of the rain, which rushed down just past their faces.

"You see that where I am going now, no one can go with me," said Tizzo. "I have to be as secret as a cat, as casual as a pack-mule. If I tried to take you with me, I would be lost at once."

"I know it," said Beatrice. "But if you go, Tizzo, I shall never see you again!"

"The keys give me a good chance. The clothes of Marignello may help me more than everything else."

"Suppose that you even get to the Englishman and then find that already he has been torn and ruined by torture so that he can't follow you?"

Tizzo groaned.

"I must not find him that way!" he said.

Then he added: "You can go to one of three houses—that of Lady Atlanta, or to my foster father, Luigi Falcone, or to the place of Antonio Bardi. Which one will you choose?"

"Lady Atlanta."

"Farewell, Beatrice."

"Tizzo, say something now for me to remember through the years when I think of you going into the rat-trap." He laughed a little. Soft-footed thunder ran down the farther sky. Lightning slid along a crack of brightness.

"You'll remember that I drank too much wine, loved dice and fighting. Remember, too, that I loved my friends and one exquisite lady—one that could be more troublesome than smoke in the eyes, more delightful than a warm fire in December."

He could see that her eyes were closed as she leaned back against the wall.

"Now go before I begin to weep," she said.

He turned and hurried up the street.

HE had with him the ax muffled under the cloak, the broad,

strong dagger of Marignello, and a file made of the most perfect

steel, three cornered, ready to eat through other metal like fire

through wood. Also, he had keys and a plan of the cellars of

della Penna. These items were all advantages. Against him he had

the hands of a strongly occupied house where one word of alarm

would bring a score of well-armed men.

Was that why he was singing under his breath when he looked up at the gloomy façade of the house of della Penna?

He passed the main entrance, with its lanterns lighted, the horses waiting saddled in the street; for now that Jeronimo della Penna was the chief lord of Perugia, he had to have horses in readiness night and day.

Around the corner he came on a small portal which was sunk into the wall, a little round-topped doorway. Into the lock of this he fitted the largest of his keys, and felt the wards moving instantly, silently under the pressure.

That success was to him prophetic of victory all the way through. It seemed a sufficient proof that Marignello had not lied. He pushed the door open, and found himself in a little semicircular guard-room where a man in breastplate and morion was rising and picking up an unsheathed sword. He gave one glance at the weapon and at the little gray pointed beard of the guard. Then he walked by, making his step longer, heavier, more lumbering to match the gait of Marignello.

"Well, Marignello," said the guard, "this is before your time, isn't it?"

Tizzo went silently on.

Behind him he heard a muttering voice say: "Surly, voiceless, low-hearted dog!"

But Tizzo, turning a bend of the corridor, left the thought of the guard behind him. He had passed through the second stage of success and now he could swear that all would go well. A great premonition of victory accompanied him.

The stairs, exactly as Marignello had charted them, opened to the right of the hall. In a niche in the wall were placed three or four small lanterns, and one of these he took with him to light his way. The dull illumination showed him the descending stages as the stairway passed over laid stone and then was cut into the living rock. A singular odor filled the air. Gray slime covered the damp corners.

Down for two stories he passed into the bowels of the earth before he came to another hall somewhat narrower than the ones above it.

The third door on the right was his destination. When he came to it he waited for an instant, his ear pressed to the iron-bound door, his heart beating wildly. It would be worth everything to shine his lantern into the blue eyes of the Englishman and see his face change when he recognized his friend. All danger was worth while in the light of that moment of recognition.

He tried the prescribed key. It worked, but not so easily, the rusted lock groaning a little under the weight of his effort. At last the door sagged inwards; he took a sudden, long step inside and pressed the door shut behind him. Then he raised the lantern high.

What he saw in the the waver and throw of the lantern was emptiness. There was not a soul in the cell. A flat bit of moldering straw in a corner might have served as a bed at one time. That was the only sign.

He looked up despairingly at the glimmer of sweat on the ceiling of the rock. He saw the innumerable chisel strokes with which the tomb had been carved in the rock. He would need a patience as great as that if he were to find the Englishman in another part of this underground world which generations had enlarged, patiently, to provide store rooms and prisons for the lordly family which lived in the upper regions of light and air.

He sat down, like a prisoner himself, on the pallet of straw, and tried to remember. As he had charted the plan of the underground rooms at the direction of Marignello, so now he re- drew the plan in his mind, bit by bit, carefully. This flight of chambers, all small, ran from side to side of the cellar. Above were slightly larger rooms. In the lowest level of all there was only the torture chamber, fittingly placed at the foot of the entire structure so that the frightful sounds from it might not rise to the upper levels, poisoning the souls of all who heard.

Had Marignello simply lied—speaking truth until he came to the last and most important step of all? Did the scoundrel really have in him one strong devotion—to his trust in the house of della Penna?

If so, it was a miracle; for one evil corrupts the entire soul.

With the lantern, Tizzo examined the heavy iron bracket and ring which were fastened at the foot of one side of the wall, opposite the door. The ring was completely covered with rust, but when he examined the inside of it, he found that the rust powdered and flaked away. He stared at the floor. There was already a very thin deposit of the same iron dust on the floor, enough to stain the tips of his fingers red.

No, Marignello had not lied entirely. Into that ring, very recently, fetters had been locked and by their chafing had loosened the rust.

Perhaps Henry of Melrose already was dead. Perhaps his body had been taken from the cell and buried. If not to a grave, to what place would he be removed?

Yes, living, they might take him to another room—the torture chamber underneath!

Tizzo was up, instantly, and in the corridor outside. Something gray and dim streaked across his feet. He heard the incredibly light scampering of a rat, saw the gleam of the long, naked tail, heard a faint squeak that made his flesh crawl.

There was no air for breathing. Fear like a vampire sucked the life from him. He would have given a year of life for the sake of ten deep breaths of the outer night.

He had done enough, he kept telling himself. He had made the venture, found failure, and now it was time for him to think of his own safety.

But while his mind was rehearsing these silent words, his feet were bearing him steadily down the corridor, and then down the last windings of the stairs. Only in the center were they worn a little by traffic. Green-gray slime grew on the wet of the steps to either side.

At the bottom of the steps there was no corridor, only a brief anteroom, so to speak, and then a very powerful door, crossed and recrossed with such iron bars that it could have endured the battering of a ram designed to tear down a wall.

The key for this door had not been named by Marignello, but there were only three that could possibly fit the yawning mouth of the lock. It was the third of these that, actually, turned the bolt and slid it with a slight rumbling noise. The hinges of the door did not creak, however. For whatever hellish purposes, this room was used and opened at not too infrequent intervals.

Gradually, he pushed the door open and stepped inside.

WHAT he saw was such a quantity of gear hanging from the

ceiling, such a litter dripping down the walls, such complicated

machines standing on the floor, that it looked like the interior

of some important manufacturer's shop—some place, say,

where iron is formed to make singular weapons or tools of trade.

But those machines were not designed for the working of wood or

of iron; they were framed to work torment into the human flesh,

and the ingenuity of a thousand devils could not have done

more.

Wherever the swift eye of Tizzo glanced, he saw monstrosities that sickened him. A pair of huge metal boots, he knew at once, were used to encase legs, while various turn-screws and wheels attached to the boots indicated the pressures which could be applied. On the wall, a great cross of iron was equipped with three terrible screws so that the victims could be crucified alive. The rack, with its double wheels at either end and all its strong tackle, looked like a carriage turned upside down, and of course it occupied the place of honor, being an instrument on which all sorts of tunes of agony could be improvised. Then there was the wheel which could turn a man head down or else spin him into a nausea. There was the hurdle for the water torture; there was tackle for hoisting men by the wrists or the thumbs into the air and leaving them suspended. There were iron weights, hammers, picks, saws with frightful teeth that reminded Tizzo of the story of the poor man who, in this prison, had a span sawed off his right arm every day until the arm was gone to the shoulder before he was willing to confess where he had buried his treasure.

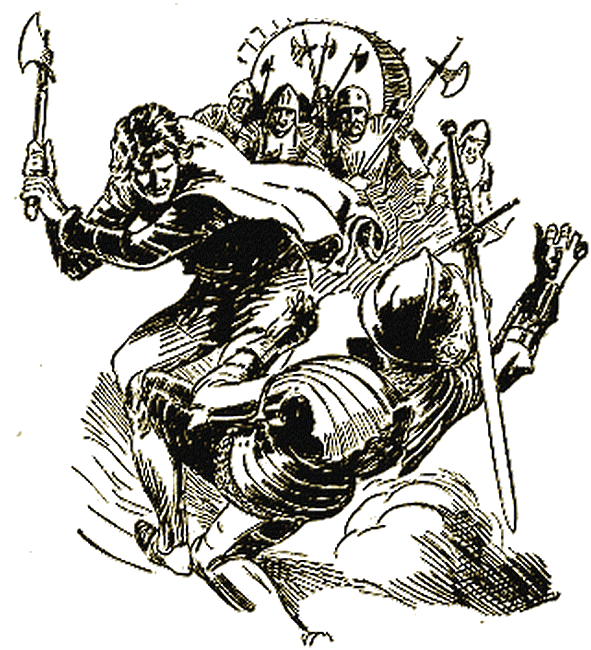

But the eyes of Tizzo fled from these horrors, and the light of his lantern now showed him, stretched on a heap of straw that was gray with time, a fine figure of a man who now lifted his head and allowed Tizzo to see the resolute face and the intensely blue eyes of Henry, Baron of Melrose.

TIZZO, with the door of the torture chamber closed, standing then above the Englishman, found the face of his friend in a sea of wavering light, because the lantern was being held in an uncertain hand.

Melrose, making a great effort, raised himself to a sitting posture. He was chained at the wrists, at the ankles, with a connecting chain which ran from the hands to the feet and thence to a great ring which was attached to a bolt that sank into the stone wall.

"Ah, Tizzo," said Melrose, "have you changed sides, made peace with your enemies, and made yourself snug in Perugia again?"

"I am here in Perugia again, my lord," said Tizzo. "But only to take you away with me."

The baron closed his eyes and nodded his head with a strange smile.

"Ah, is that it?" he said. "Here in Perugia? And to take me away?" Tizzo threw back the cloak. He leaned the great woodsman's ax against the wall and showed the file.

"This is the way to cut the Gordian knot." he said.

Melrose opened his eyes, looked at the file, and shook his grizzled head.

"It won't do, Tizzo," he said. "You're going to walk me out of the prison. Isn't that the thought?"

"And why not?" said Tizzo.

"Can you find a way back for yourself?"

"I think so."

"Then find it now, and use it."

"What?"

"I shall not go with you."

"My lord?"

"Damn my lord," said the Englishman. "What made you come here in the first place?"

"You taught me what to do when a friend is in trouble," said Tizzo.

"In what way?"

"I have not forgotten the day you entered Perugia and risked your head in order to set mine in freedom."

"Ah, I remember something about that," said Melrose. "And that good fellow, that Giovanpaolo, not only set you free but refused to take my life in payment for yours, though he knew that I was a lifelong servant of the Oddi, whom he has reason to hate."

"Giovanpaolo is my sworn brother," said Tizzo. "And chiefly because of what he did that day. If there were a way for him to break into Perugia suddenly, I should not have had to slip into the town by stealth. We should have bought you by our work in battle, my lord."

"Perhaps you would," said Melrose. "But I rather think that Jeronimo della Penna would have used an extra five minutes to run down into his cellar, when he saw the day—or the night—was lost. He would have used that time to come down and put a knife into me. The bottles of wine in his cellar, Tizzo, are not half so dear to him as all the revenge which he opens, like a sweet perfume, when he sees me.

"Why does he hate you, my lord? Because Giovanpaolo slipped through the gate you were guarding?"

"And the Lady Beatrice—and you. Mostly because of you, Tizzo. The fact is that he hates you a little more than he hates the rest of the world because, as he says, you cheated him. You pretended to be on his side."

Tizzo dropped to one knee and began to use the file on the heavy manacles that linked the wrists of the prisoner together.

"It is no use, Tizzo," said the prisoner.

"No use?" exclaimed Tizzo, looking up in astonishment.

"Not in the least. Do as I tell you. Leave the prison at once."

"Why is there no use in setting your hands free?"

"Because, my lad, even after they are free, I shall not be able to use them."

"I don't understand," said Tizzo, staring down at the deep, silver-shining trench which the file already had cut into the comparatively soft iron.

"Why, Tizzo, it means that I have paid a visit to the lady, yonder."

"What lady?"

"It has a good many names. Some people call it the engine of grace. Others call it the rack."

Tizzo, jerking his head about, stared at the double-wheeled length of the great rack, with the old, stiff cordage attached to it, and the terrible sliding beam in the center which could be moved by the wheel to any length. What fiendish brains ever had devised the rack, which pulls at the head and the feet of a man until from wrists to ankles the body is drawn taut and every tendon, every joint, contributes its note to the general symphony of exquisite agony. There was the pain to consider—there was also the deathless shame of the naked body which had to submit to the torments of the enemy.

He looked at that frightful instrument, whose name ran into all the nightmares of the age, and then back at the man who had suffered from it. He saw the seated figure hunched over, as though the backbone had no rigid strength. Part of the weight rested on the arms, and the arms shook under the burden. Those powerful arms in which a battle-mace ordinarily was a toy, were now bending under the elbows. A bed-ridden old man could not have been more feeble. The head of the baron thrust out on his thick neck. Pain devoured his eyes. But still he managed some sort of a smile.

And Tizzo, groaning aloud, said: "God, God! Why have I come a day too late?"

"The rascal Marignello required time as well as money," said the prisoner. "But a day ago you would not have found me here. I was in a cell on the tier above. This morning della Penna decided to begin spinning out my death in a long, thin thread. He stood over me during the torment. He kept feeling the hardness of my shoulders and thighs as the strain of the rack grew greater. He kept telling them to go more slowly, more tenderly. Tenderly was the word he used, laughing. He laughed, and told them to use me more tenderly. Stretch the beef today and cut it up tomorrow. He stood over me with the rod of iron, ready to tap some of my bones and break them, but that was a temptation he resisted. Tomorrow he will break an arm. The next day a leg. Then another arm. Then a few ribs. What, Tizzo? Would a connoisseur swallow off his wine? No, he would taste it slowly, rolling the drops over his tongue and up against his palate."

"God curse and strike him!" said Tizzo.

"Not God. You must strike him," said the baron. "I tell you, Tizzo, that I could not walk from the prison, even with all the doors thrown open. I could hardly crawl or writhe along like a snake. A snail would be faster than I. You are not a mule to carry me hence. Therefore, escape, yourself, as you may. And afterwards, if Giovanpaolo takes the city, strike no blow except at Jeronimo della Penna. Strike only for his head. Beat him down. And for every stroke that maims him, that slays him by degrees, cry my name. Cry 'Melrose!' while you enjoy the killing of him. That will be a comfort to my soul, no matter how deep in hell I am hidden away. I shall hear every word you utter. I shall taste every drop of his blood. I shall laugh at hell-fire as della Penna dies."

"I shall kill him afterwards," said Tizzo. "God knows that I shall kill him, but now there is only one task."

HE gripped the wrist irons and began to file at them,

furiously. And the noise was like that of the singing of a

mosquito in the torture chamber.

"Take care of what you do!" said Melrose. "If you throw yourself away, I am cheated of my revenge. Listen to me, Tizzo. If I even dream that revenge will fill its belly with the life of della Penna, I can endure everything. For every pang he gives me, I can laugh loud and long, because I shall promise myself that he will die by worse pains afterwards. And, axing a coward, he will taste every agony thrice over. My death will only enrich me, if I can hope that he will die afterwards, and by your hand, my noble friend."

Tizzo said nothing. He merely set his teeth, and the file turned the iron of the manacles hot as it bit into the metal.

"Tizzo!" exclaimed Melrose. "If ever we fought together, and if ever I taught you the innermost secrets of my sword-craft, I beseech you, leave me—save your life—do not cast yourself away in trying to help a hopeless wreck from the reef. I shall only sink, myself, and draw you down after me."

"The courtyard of Marozzo," said Tizzo, "and my own life bleeding away, and Marozzo ordering more of his men to fight with me, and then the entrance of Astorre and Giovanpaolo, with you—you who had given up your life in order to pay down a price that would ransom me. God! Do you think I have forgotten?"

"Ah, you remember that?" said 'Melrose.

"Aye. I remember."

"And another thing?"

"When I first saw you," said Tizzo, "I knew, suddenly, that I had met the man I wished to follow around the world."

"Like a young, impressionable, silly fool," said the Englishman. "I have received nothing from the world but blows and I have paid my reckoning in the same coin."

Then he added: "Tizzo, I ask one boon of you."

"I shall not grant it," said Tizzo.

He asked, in his turn: "But tell me what angel drew you on, my lord? What made you, in the first place, risk your life in order to save mine?"

"An imp of the perverse, it seems," said Melrose, "that must have told me that if I risked my life in the first place I then should have the privilege of drawing the two of us down into perdition, as I am drawing us now. Do you hear me?"

"Rather," said Tizzo, "an angel of heaven who told you that death is an easy thing, when there are two friends to endure it."

"Friends?" said the baron, loudly and suddenly. "Well, call it that—"

But as he said this, there was a dim sound of steps in the corridor outside, and then a wrangling of iron at the door to the torture chamber.

"They have come to take me to the finish," said Melrose. "Jeronimo could not wait any longer. His appetite was greater than his patience. But, ah, God, that he should find two morsels to swallow instead of one!"

TIZZO, fingering his ax, looked desperately towards the door. The quick, soft voice of Melrose stopped him.

"No, no! Tizzo, you may strike down one or two but the mob will kill you. They'll worry you to death. You are trapped. But no man is dead to hope while there is still breath in him. Do you hear? Out with the lantern. Roll in under the old straw, here. They shall not find you, if God is willing!"