RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

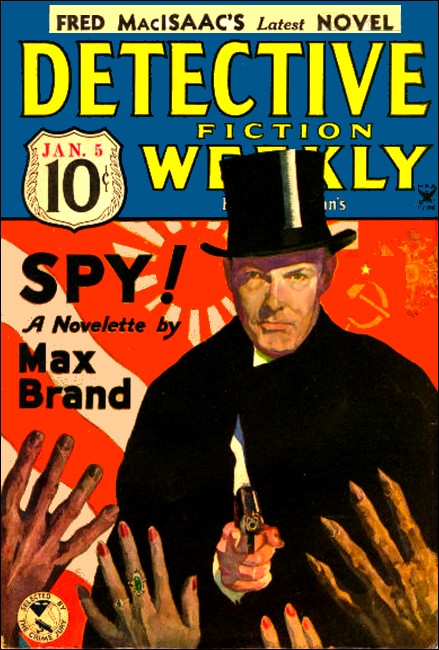

Detective Fiction Weekly, 5 Jan 1935,

with

"The Case of the Strange Villa"

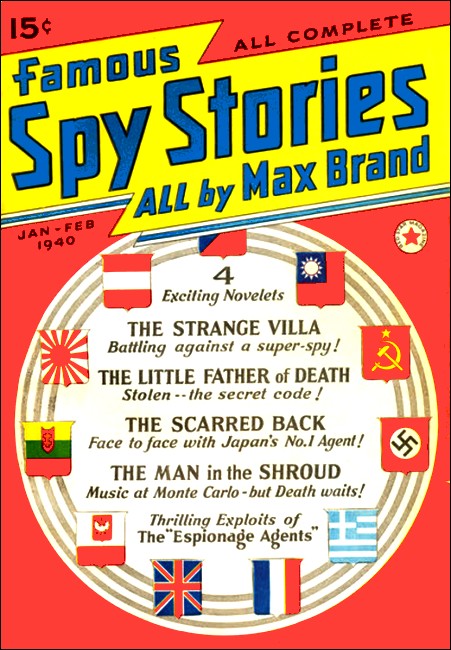

Famous Spy Stories, Jan-Feb 1940, with

"The Strange Villa"

He watched her put the little volume into her handbag.

Out of the Clouds Dropped Anthony Hamilton to

Match Wits With That Dread Man of Mystery Who Was

Plotting to Strew the Earth with Ten Million Corpses.

UP there at seventeen thousand feet the moon shone and the stars were scattered, with the plane of Anthony Hamilton flung across them like a flat stone skidding over a pool. But he had to sink out of that clear beauty to the earth, and all the warmth of his electrically heated clothing could not comfort him. Two miles beneath him lay a smooth white sea of clouds, which meant a low ceiling out of which he must land.

Or perhaps clouds and fog continued all the way to the ground, and in that case he was probably a dead man. Usually he looked to every detail of preparation himself before stepping into a plane, but on this occasion he had left arrangements in the hands of a subordinate. A parachute was missing. To get one meant delay and in the counter-espionage service of the United States delay is not permitted. Lives must be run to a schedule like a train-service. So he had taken the chance. The little monoplane had shot him through the chill of the upper spaces at four miles a minute and here he was over his goal, with the tank empty and the gasoline fading out of the reserve. There again he had been a fool to trust another man's word about the rate of fuel consumption in this new type of engine.

In spite of the fog, he knew almost to a hair's-breadth the exact scene which was clouded over. Just south lay Mont Agel with Monte Carlo at its feet, and just about under him, in the rough of the hills, lay that flat valley where he was expected.

If the head of a single mountain had lifted above the white floor, he would have been able to place himself perfectly, but perhaps not perfectly enough, to locate that narrow strip of valley. At four miles a minute there is not time for deliberate calculation. He remembered, suddenly, the last time he had teed up a bail on the golf course of flat-topped Mont Agel, with a feeling that he could drive off right into the blue of the Mediterranean, Now all that beauty was stifled in deadly white. This great, liquid bowl of the sky had at the bottom a dirty sediment into which he had to sink.

He banked and turned, with a slight giddiness, a sense of losing balance, a pressure in his ears; then he dived. It was as though he stood still with the stars flying upwards, turning from-dots into dashes of brightness. The air screamed on the struts, whistling a tune as loud as the hurrying drum-beat of the motor. The clouds lifted at him, not the smooth white floor they had appeared from above, but high-surging waves, a sea struck to ice in the middle of a storm by one touch of interstellar cold. The waves grew into hills of volcanic crystal; they exploded upwards, and now he dropped like a stone through the upper translucence, through a brief margin of gray in which cloud-forms appeared, abortive and shapeless, and down into the blind hollow of darkness.

The altimeter showed him a thousand feet, and still the wet darkness blew about him. He had the inevitable feeling that the instrument was wrong and that he was about to strike that instant, on earth which would be turned hard as steel by the force of the impact. But the altimeter must be trusted. That is the first lesson in blind flying. He set his teeth, smiling a little.

Five hundred feet—three hundred—.

The bottom of the well was just beneath, and still there was not a gleam, not a glimmer of light. The curtain of cloud dropped its thick fringes right down to the earth. On such a night, even automobiles would be crawling in second along the winding mountain roads.

Something appeared on his left, vague as the first loom of land to a ship at sea. He turned right and felt, rather than saw, the ragged side of a mountain. He was flying level, using that sheer instinct which was one of his greatest gifts in the air. He had readjusted the angle of his propeller-blades so that they would take a smaller bite of the thick sea-level atmosphere, but he wished for more power when he felt again that presence of a solid mass on the left.

He turned right, and again from another crag to the right once more. He realized, now, that he was swirling about blindly inside the cup of a mountain valley which was very narrow but perhaps three or four miles long. It must be that he had dropped down on the very goal of his journey. He dropped his one landing-flare. The gleaming line of it flashed, went put. It had struck water.

He sank lower, to two hundred feet, to one hundred—the very sword-edge of danger was at his throat, now, when he saw three dim eyes beneath.

He circled at fifty feet. Hands blacker than the darkness struck up at him. He had slid just over the tops of some trees, but he could make out a cone of radiance extending from those three eyes—a cone that flattened on the lower side. That flatness must be the ground. He shut off the motor and flattened out. Wings beat at him, left and right—more trees. The wheels struck, staggered the plane into a crazy wobbling which he righted with a delicate touch, and then the little monoplane was whispering lightly over grass, slowing, stopping.

WELL, the thing was over and in the service men must not allow themselves to ponder over many strange phases which they add, from time to time, to the history of their past. Anthony Hamilton pulled at a few buckles, shed his heavy flying suit, and stepped out of the plane into the creamy verge of the illumination shed by the three headlights. At this moment one of them went out ; the other pair swerved forward and an automobile stopped just before him. The full glare fell on Hamilton and showed him a little older, for the moment, than his twenty-seven years. He had that sight stoop of the shoulders which comes from much bending over books—or tennis-rackets. He seemed a bit grim—for this instant only—but a moment later he was smiling. He was always smiling, and this gave him an air of inexhaustible, boyish good nature.

A big man got out of the automobile and came up to him. The headlights" were dimmed at the same moment, leaving only a dusty glow in the fog.

The waxed ends of the big fellow's mustaches were gleaming as he came up to Hamilton.

"This is not a landing field for airplanes, monsieur," said he.

"It is not a highway for automobiles, either," said Hamilton.

"Monsieur, I am an agent of the Sûreté. May I ask for your paper of identity?"

"Certainly," said Hamilton. "Will you take a cigarette from me, at the same time?"

"You are very kind," said the big man. He took a cigarette from the case which Hamilton offered and himself supplied the light, holding it just a part of a second longer than necessary close to the rather unhandsome face of Hamilton. And Hamilton turned, as a man will, a little to the side as he reached into a inner pocket. He took out a pigskin wallet among whose contents he began to fumble slowly. In the meantime the eye of the big man was occupied by certain characters which became visible along the cigarette, little luminous marks that showed, one by one just before the paper curled and charred. The first portion of a signature became visible, letter by letter, before the agent of the Sûreté cried out:

"But you can't be the man! You're twenty years too young! I beg your pardon, Mr, Hamilton."

"I suppose I ought to thank you for a compliment," said Hamilton. "You're Harrison Victor, of course?"

"I am Louis Desaix, of the Sûreté," said the other, "and only Harrison Victor in Ohio and a few points east."

He shook hands, then called:

"Jack! Come here, will you?"

A second man came from the automobile.

"John Carney—Anthony Hamilton. This is the new chief, Jack. Carney's the man to take care of the plane, Mr. Hamilton."

"How you dropped it down the middle of this well I can't understand," said Carney. "We saw the landing flare hit the pool yonder and then we waited for the machine to smash and you to bail out and come floating down in the parachute."

"I should have bailed out instead of feeling my way around this room in the dark," said Hamilton," but a fellow at the other end of the line forgot all about the parachute."

"You came anyway?" asked Harrison Victor. "You must have known that there was fog down here before you started."

"I couldn't tell that there was fog all the way to the ground. Did you bring out gasoline for the plane?"

They had plenty of it and the two helped Carney carry the tins to the monoplane,

"How is she?" asked Carney. "I'll have to wait here alone until daybreak and I'd like to have something to think about."

"She's fast as a bullet and nervous as a two-year-old filly," said Hamilton. "She takes the air like a bird, but watch her when you make a landing."

They said good-by to Carney, who knew where to take the plane, and got into the car. Harrison Victor trundled it over the field, gained the road, and slid through the white smother with increasing speed. He seemed to feel the road by instinct.

"Will you paint the picture for me?" asked Hamilton,

"Show me the part you know, first of all."

Hamilton leaned a little closer. "That letter was a beauty. I can recite it.

"'Number 1815'—my number is the same as the date of Waterloo, so it will be easy for you to remember—'Number 1815, you will go at once to Monte Carlo, abandoning all other work. At the Pension Mon Sourir there now resides, or frequently visits, the Number One secret service man of Japan. His nationality and name are unknown. Discover both, together with his present purpose in Europe. Our source of information cannot be drawn upon further. It is dead.' That was the main portion of the letter. The rest was a sketch of how I should proceed down here and where you would pick me up. They might hare picked out an easier spot, I suppose."

"SOMETIMES," said Harrison Victor,

"Washington is a little more than three thousand miles away from good sense. But at any rate you're here, and that's a comfort. Officially I heard that you were coming; unofficially, I learned that you were the man who did the big job in Okhotsk. That was why I was surprised when I saw you."

"You know in a Russian winter it's easy to grow a beard," said Hamilton.

"How old are you, really? Twenty-four?"

"Twenty-seven."

"I was wrong again. It must come from living a lot and not giving a damn."

"Victor, what have you fellows turned up, down here? What's the Villa Mon Sourir?"

"You know Les Roches?"

"That point which runs out to sea?"

"Yes. Mon Sourir is down there in a huddle of pines. An old Italian villa. It's owned now, or rather rented, on a long lease by a Californian, a bearded fellow called George Michelson. He has his daughter with him. She runs the place as a pension."

"What sort of boarders?" Hamilton asked.

"Usual Riviera run. Polish girl—invalid. A German. A Czechoslovak. An American called Harbor. John Harbor. Vicomte Henri de Graulchier. Just the usual Riviera hodge-podge. No, nicer than usual, most of them. We've looked the place over as well as we could."

"Have you put an agent in the house?"

"We tried to. We sent out Louise Curran. Know her?"

"No."

"Ah, you don't know her? Louise is a card and she's turned up some good tricks in her time, for the service. She went out and tried to get a room, but the place was full up. No vacancies in sight. So I had Bill West go out to lake a look at things. You know him?"

"He worked for me in Ireland, one summer."

"Great Scott, are you the man who—?"

"Ah, never mind that."

"I mind, but I'll shut up. You're the whalebone and rubber man who did all the fox-hunting, are you? Ah, well—I sent Bill West out, as I say, and he got into the place all right."

"Find out anything?"

"Yes, he found the Vicomte de Graulchier looking down a revolver at him. Hardy fellow, that vicomte. Fat-looking little chunk, but hardy. Of course Bill had to go to jail as a burglar. He's in for five years, and nothing that any of us can do about it. That's all the forwarder we are about the Villa Mon Sourir. As far as we can make out, the place is innocent, all right. All except John Harbor. And I think that he's the Japanese Number One. You never would expect it, either. Sleek, lazy, good-natured blighter. Likes his afternoon vermouth. But we've caught him cold taking code messages."

Drifts of blinding light poured towards them, like bright-blowing squalls of rain. A succession of automobiles wound by, each screeching a horn in sudden alarm, all of them groaning in low gears; but Harrison Victor shot his own big car along with a sort of random ease, as though he were not aware that his fenders had clinked once or twice like small bells against the passing mudguards.

"Got the code?" asked Hamilton.

"No, it's a hard one to work."

"Where does he got the messages?"

"In the Casino at Monte Carlo; but we don't know the source. We've tried, but we can't tell where he gets them. However, we have copies of a lot of them. A whole book of them. Once we decipher the code, the job will be finished."

"That sounds too easy."

"Everything is easy in this game—unless you die while you're winning."

"Japan wants the entire east for herself," Hamilton said. "If she has sent her Number One man to the Villa Mon Sourir, hell is going to pop. And I don't think it will be simple to get to the bottom of that hell."

"We've thought of that in a good deal of detail?"

"Do you know who Japan's Number One is?"

"Not even his complexion."

"No one does," answered Hamilton. "We only know one bit of information. Japan's Number One is the fellow who induced Theodore Roosevelt to intervene in the Russo-Japanese War. Honestly, you know—to prevent bloodshed, bring world peace nearer, and all that. But his intervention probably saved the skin of Japan. She'd spent her last yen on the job when Roosevelt started persuading Russia towards peace. Wherever Japan's Number One is now, you can depend upon it the entire interest of Japan is invested. She wouldn't send him five minutes away from Tokio unless there were some new stars in the sky. This job is vital, Victor."

"I guessed at most of that."

"Going back to Mon Sourir. You don't find anything extraordinary about the place?"

"Not a thing. Not a single thing except George Michelson's daughter."

"Well, what about her?"

"The loveliest thing I've ever seen."

"Ah, I see," said Hamilton.

"No, you don't see," said Harrison Victor. "When I said 'loveliest' I mean just that. Perfect."

"Greek goddess, eh?"

"She's what the Greeks might have produced if they'd kept maturing for another twenty-five centuries. Phidias a little lighter in the bone. I've looked into her because I've looked into everyone in the Villa Mon Sourir. I've found out that she swims the American crawl, went around the rocks and bumps of Mont Agel in seventy-eight honest strokes, flies an airplane, drives an automobile like an Italian devil, speaks French, German, Italian, Spanish and—God help me—Russian, also."

"Describe her, will you?"

"She's going to he with her father at the Casino, tonight. And that's where I'm taking you. You'll see her for yourself. Luminous as a blonde, mysterious as a brunette. Most damned, exquisite smile."

"And she runs a little pension on the Riviera?" asked Hamilton.

"You know. Her father isn't so young or so welL"

"What an equipment she has to be the world's Number One secret service agent," said Hamilton.

THE architect of the Casino at Monte Carlo is the man who erected the Opera House in Paris, a fellow with an instinct for overloading everything. His attempts at ornateness merely gave a puffed and stuffed effect to his exteriors, and his interiors are as overwhelming as an assemblage of fat dowagers. Besides, gilding and regilding cannot brighten Monte Carlo, and all the lights cannot penetrate the grave shadow which enters the mind. The flush and sparkle of after-dinner parties who come in for a dash of play soon passes. Women assume Spartan manners. They never cry out with joy; they never groan or exclaim. They win with austerity and lose with contempt. Besides these casual visitors there are the serious players, who sit about the tables equipped with paper and pencil, making rapid notes, busy as bank clerks with their systems. These are the real devotees, and their pale, stern faces tell us that Chance is a dark goddess.

Anthony Hamilton, entering in a dinner jacket in the middle of the evening, looked so young, so rich, so American, so flushed with wine and good nature, that it was astonishing to see such a man without company. His presence was felt at a roulette table at once. Even the serious players looked up at him with a faint gleam of contempt and prophesy as he began to play single numbers.

He laid hundred-franc bets, three of diem, always on the nine, and watched his money whisk away. In the meantime he was spotting the characters from the Villa Mon Sourir who, as Harrison Victor had promised, were gathered at this table. By Victor's descriptions he could identify them easily- The big fellow with the rigidly straight back and the sour face who kept consulting his "system" and jotting down numbers was John Harbor, the American from Mon Sourir. The fellow with the short legs and large head, he whose swarthy skin was pricked full of small holes like needle-scars, was the Vicomte Henri de Graulchier. He had the stiff upper lip of a drinker, and his black eyes were continually empty.

Yet his dignity was interesting, and so was the purity of his English, which retained only a slight oil of the French "r's." The very blonde girl was the Pole, Maria Blachavenski, too thin to be pretty except when she smiled. George Michelson of California wore a beard and mustache, so trimmed that he had a Continental look, but a certain bigness of body and of voice betrayed his Western origin from time to time. He stood behind the chair of his daughter, Mary Michelson, watching her lay her small bets with careful precision.

She was beautiful, yet her beauty seemed to Hamilton to be a very dull affair. He was about to decide that Harrison Victor's paean of praise was a worthless enthusiasm, when she looked up to her father with a smile. Then Hamilton saw the light; a great deal of it. It was true that she could have been lost in a crowd, but everyone who looked at her twice would be stopped.

These were the representatives from the Villa Mon Sourir. As for the agents who worked under Harrison Victor, there was only one present.

That was Louise Curran, exquisitely dainty and fresh and good to see. Apparently her "system" could not occupy all her attention, for every now and then she would lift her hand-bag to powder her nose.

In reality, as Hamilton knew, she was catching in the glass, and memorizing, with lightning adeptness, whole columns of the figures which John Harbor continually scribbled on a small pad, jerking off the sheets one by one and putting them under the pad. It was in this manner, and with other simple methods, that Harrison Victor had collected quantities of the notations of Harbor. The instant the code was known, a flood of information would pour into the hands of the American counter-espionage service.

Well, all codes can be solved. That is the old saying, but Hamilton did not believe it. In the meantime, what was the source of the information which Harbor was noting down? It might have been almost anything; one of the horns which sounded dimly from the street, the almost imperceptible tremors and fluctuations of one of the lights in the room, the hand movements of some other person, writing at the table, the finger-work of the croupier as he wielded his rake. There were a thousand ways of conveying steady messages such as Harbor was writing down; and that he was scribbling a code there could be no doubt to anyone who considered the sort of numbers he employed. At roulette there is nothing higher than thirty-five, but a typical page of Harbor's notes had read:

15 — 331

245— 86

90 — 191

Under this column of figures appeared a line for addition, but the sum which appeared in the result had, apparently, nothing to do with the column of figures itself.

STUDYING the calm, still face of Harbor, Hamilton decided instantly that the man himself did not know what he was taking down. The figures were not his shorthand report. They made an unintelligible jargon until they were decoded.

Hamilton, laying his fourth bet on the nine, was surprised by a win. Thirty-five hundred francs was not a great haul, but it was something; eyes lifted to him again from around the table and he permitted himself to laugh with a vacuous joy.

It was one of the major triumphs of his art, the production of that laughter, whether it were silent or noisy. He had worked for months perfecting it until, at his will, it could sweep every semblance of intelligence out of his face and sponge all record of thought from his brain. John Harbor seemed overwhelmed by disgust as he stared at the laughing face, so overwhelmed that he suddenly rose from the table, dropped his writing pad into his coat pocket, and left the room.

Hamilton drifted behind him through the room. The size of the stake he had won furnished him with an excellent excuse for leaving the table at that particular moment. He watched John Harbor go out into the garden and slipped after him.

The fog still covered the night, so that the garden lamps shone through enormous halos. The pavement was wet. The palm trees glistened dimly. John Harbor, walking impatiently up and down, tipped one of those gracefully arching branches and cursed the chilly shower of drops that fell on him. He began to brush his coat dry with a handkerchief but still he looked about him, until it was apparent that he was waiting to fill an appointment.

Hamilton slipped quietly up behind the palm tree nearest to his quarry and then—he had eyes in his feet like any jungle tracker and the thing should never have happened—he stepped into a hole left where a small paving block had been removed, no doubt for replacement the next day, and pitched forward on his knees.

He had trusted to the tree and the fog so entirely that he fell almost in touching distance of Harbor, and that big fellow whirled about with a grunt of fear. He must have been keyed to an electric tension because, as he turned, he snatched a gun and fired point-blank.

The thing was incredible; it could not have happened; but while the brain of Hamilton was disclaiming the possibility of the entire affair his hand was jerking an automatic from the spring holster which supported it under the pit of his left arm. The first bullet had missed him; the second would not. Still down on both knees and one hand, he shot John Harbor through the head and saw the body fall face down. The impact was like the whack of a fist against bare flesh.

Hamilton, rising, waited for half a second. No footfalls came towards him; from the streets of the town roared and whined the noise of the automobile traffic. At any moment attendants might pour out around him, and in that case, he was a dead man. The first rule of the counter-espionage service is that its agents receive no government support when they operate abroad. So, for half a second, he contemplated instant flight.

The next moment he was leaning over the dead man with swift hands at work. Fountain pen, wallet, watch he recognized by the first sweeping touch. A hard, flat box in the left coat pocket he drew out and found it to be a book, a little volume of Everyman's Library bound in dull green cloth—" The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile," by J. H. Speke, that strange fellow whom the great Burton had hated and envied so. He slid the book back into the same pocket, located the little writing pad with its rustling loose pages beside it, and decided to leave all in place.

Tie looked once more down at the loose body, the hands which grasped inertly at the stones; then he drew back into covert behind the palms. No doubt it was still dangerous for him to linger near, but it was very important to discover the persons with whom Harbor had appointed this trysting place.

Another long, long minute drew out; then he heard the quick, light tapping of heels and saw coming straight towards the dead man Harrison Victor's angel of beauty and of grace, Mary Michelson.

SHE was tall, and she moved with the crisp step of one who is enjoying a walk. From brightness to brightness, she moved across the cloudy dazzle of the tall lamps.

He waited to see her take heed of the falling body but there was no pausing in her approach. She walked straight up to the dead man and leaned over him. Her hands were busy. As she straightened he saw that she was putting into her handbag the little Everyman volume; and with it went the notations which John Harbor had been making that evening.

That seemed cold-blooded enough, but that was not all. With her handkerchief—to prevent finger-marks, of course—she picked up the automatic, which had slithered away to a little distance, and put it inside the grasp of the dead fingers of Harbor. Then with that swift, light step which seemed a special attribute of virtue, she went back into the Casino.

He followed; after making sure that there was no mark on the knees of his trousers to indicate the place where he had fallen. He was just coming in from the garden when he saw Harrison Victor pass out through the doorway. He hailed Victor with a murmur and drew him aside.

"Your beautiful angel is one of them," said Hamilton. "John Harbor is dead, and I've seen her plunder him of his notes of this evening as well as a book. What the book could have to do with the business I can't tell. She was as cool over the dead man as a bird over a fallen seed."

"Is she one of them?" said the agent of the Sûreté, sadly. "Well, I've never fallen in love without having it shaken right out of me again. What killed Harbor?"

"I did," said Hamilton. "A damned clumsy, stupid business. But at one time I was on my knees, and he was putting bullets past my ears. He was just a little nervous. But the girl, Victor—she's the one for study. If she were honest, she'd be an angel; since she's a crook, she's probably a devil. I have to be introduced to her."

"You killed Harbor?" murmured Victor, but he added, calm at once: "I don't know Mary Michelson."

"Send one of your men to the table where she plays and have him try to nail her stakes; I'll interfere; that will be introduction enough."

"If you want to go about it—if you don't think that's too much college farce?"

I believe in college farce," said Hamilton.

"Farce in the house and dead men in the garden, eh? I'll arrange it as you say, of course."

Well, it was not strange if Harrison Victor were distinctly cool. Who could tell what disastrous effects the killing of Harbor might have? Before he went in, Victor said:

"I've just had a report from Jack Carney. The fog lifted back there in the valley and as soon as he saw a star he jumped the plane at it. He says that little amphibian swam across the sky just like a goldfish across a bowl. In three wriggles it was over the sea and through a lucky rift he was able to get down to the water. He says he still feels as though he had been riding in a thunderbolt; he's bumped a shower of sparks out of the sky."

Hamilton went back into the game rooms, but stopped a moment on the way to have a pony of brandy. There is nothing that loads the air with alcohol fumes as cognac docs. If he gave the impression of having had a drop too much it would be as well.

The girl, as he had expected, was back in her place with her father now at her side. If she were a part of an international spy ring, it seemed certain that her father was implicated also. The great forehead, the noble openness of eye in this man denied such a thing as much as did the beauty of the girl; and Hamilton remembered with a leap of the heart that men and women can give their lives to espionage because they are capable of loving danger and their country.

He drifted idly about the table, making his bets two hundred francs now, and merely laughing in his foolish, silent way when the croupier raked in his money. The girl had just won on the black when a long arm reached from behind and collected her entire bet.

"The lady's money, my friend," said Hamilton, and gripped that arm at the wrist. He looked up into the face of a tall man who was breathing whisky-fumes.

"Hello! Hello!" said a very English accent. "Isn't that money mine?"

"I'm afraid it is not," said George Michelson.

"Oh, I laid my bet over there," said the stranger. "Frightfully sorry."

He moved off.

"THAT was nice of you," said the girl, smiling up at Hamilton. He favored her with his witless laugh.

"I was watching your system," he said," and I can't make a thing out of it. Deep, isn't it? I've tried systems, but can't keep on any of them for a whole evening. Some idea of my own comes buzzing along and there I go again, chasing butterflies. May I sit down here?"

"Of course," she said.

He took the chair beside her, luckily vacant. She was giving him only a partial attention, the rest going to a consideration of the lists of figures which composed her system. Now she was placing a new bet. The lack of makeup, he saw, was one thing that made her beauty a little dim, but the absence of artificial color set off the intense blueness of her eyes. He never had seen anything quite like that blue.

"You're English, aren't you?" asked he, babbling along.

"No, American."

"Ah, are you? So am I. Came a had cropper down in Virginia a while back—schooling a green idiot of a five-year-old over ditch and timber—and the doctor said I'd better have a change of air and no horses. So over I came to take the old spin around."

He pointed to a small lump at the side of his forehead. It was quite true that he had had a bad fall from a horse, but not in Virginia. A bullet from an old-fashioned Persian musket had killed the gray Arab mare he was riding as he got out of Teheran towards healthier and less romantic names on the map. Well, that was simply another sentence that belonged to the dead book of the past.

"I know some Virginia people," the girl was saying. "Sally Keith, for one."

"Do you, really?" He flicked like lightning the complicated card index of his memory. "Why, this is like an introduction! Sally taught me my manners cub-hunting, ten years ago. Perhaps you've heard her mention me, because she still makes table-talk out of the silly things I did that day? My name is Anthony Hamilton."

"Perhaps I have heard her speak of you. I'm Mary Michelson. Father, ibis is Anthony Hamilton, who knows Sally Keith in Virginia."

The big, bearded man stood up and shook hands with a good, strong grip. "That was a quick eye and hand you used on that sharper, a moment ago," he said.

WHEN he left the table he signed to Victor and met him outside the building.

"Have the Michelsons a car?" he asked.

"I have it spotted," said Victor. "Any luck?"

"No, I've registered myself as a feather-brain, a poor, harmless blighter. That's all. They're charming, but they won't be drawn. We've been introduced, and that's all."

"What do you make of her?"

"Absolutely nothing. She might be a saint, except that I've seen her pick the pockets of a dead man. Put a good man on Michelson's car. Have him fix it so that the machine will break down hopelessly a few miles out of Monte Carlo. And not too near to Les Roches. The moment they start off, send a man to my car and wake me up."

"Wake you up?"

"I'll be asleep."

He went to his parked machine. It had a compact body and one of those all-weather tops that go up and down as easily as an umbrella. The seat beside the driver's could be flattened out until it gave almost the comfort of a couch. Hamilton stretched himself on it, closed his eyes, and resolutely toppled himself off the edge of consciousness into the fathomless oblivion of sleep.

A voice at his ear brought him at a step back to full possession of his wits. A shadowy arm was pointing and the voice saying;

"There they go—Michelson and his daughter alone in the car."

He had his own swift machine instantly on the way. It had the long, low hang that he liked and it took corners as though it were running on tracks; so he snaked through the crooked streets of Monte Carlo without ever losing sight of his goal. He was not really out of the city at any time, but merely away from the thickest heart of it. Michelson drove fast, but it was child's play for Hamilton's racer to keep in touch.

He wondered whether or not he should have spoken to Harrison Victor about the singular importance which seemed to attach to the copy of Speke's "Journal." However, that importance would no doubt be a few mysterious annotations which John Harbor might have made on a fly-leaf. Perhaps it was chiefly to receive this book that the girl had the appointment with Harbor; and yet they lived in the same house, where she must have the leisure to meet him as she chose.

These questions were so small that they were only worth registering, not long consideration.

They were well out from the city when the tail lights of Michelson's car wavered, then stopped at the side of the road.

Anthony Hamilton halted immediately behind them.

Big Michelson had the hood open and was leaning over the engine, but it was the girl whose hands were busied. "Ah, Mr. Hamilton! What a chance to meet you here!" said Michelson.

The girl, however, did not lift her head at once from the engine she was examining.

"Not a chance at all," answered Hamilton. "You see, there's not much around here for me except weather and wine and roulette, and I wanted to find out where you live. You don't mind, Mr. Michelson? Let me try to be useful."

"The carburetor's gone," said the girl, straightening at last. "Hello, Mr. Hamilton. Will you give us a lift home? We'll have to send garage people to bring in the car."

"But how could the carburetor go, my dear?" asked the father.

"I don't know," she answered. "It's a bit weird, altogether."

"I'll get your things out," said Hamilton. He was already at work as he spoke, lifting an overcoat and a wrap out of the little automobile. But first his hand had touched the evening bag of the girl—and found it empty! She had disposed of Speke's "Journal" as quickly as this. The book became, suddenly, of a vast importance It was instantly the entire goal of Hamilton's search.

He got them comfortably into his car and drove, turning in the seat so that he could keep on chattering. But the way to Les Roches was all too short. The car was quickly among the boulders and pines of the little peninsula and now they directed him to stop at a great gate of wrought iron in the middle of a pink wall.

The yellow mimosas of the garden within showed vaguely through the mist in the glow of the headlights. The same light, passing down the length of the wall, found the rocks of a beach and the thin hint of waves under the fog. Over the gate appeared the name: Mon Sourir.

"We should ask you in," said the girl, "but we're responsible for the pension, Mr. Hamilton, and one of our guests is slightly ill and is a frightfully light sleeper."

"You know," said Hamilton, "if you have an extra room I'd like to come here. I'd move in tomorrow morning."

He stood so that the light would fully illumine the vacuous smile with which he admired her. She showed not the least amusement or contempt.

"What a pity that every room is full, just now," she said.

"But may I call?"

"Ah, of course you may. Good-night, Mr. Hamilton. How kind you've been!"

Michelson gave him that hearty handshake again.

"Drop in any time," he said. "We both want to see you."

That was all. Hamilton, watching them through the gate, studied the coat of Michelson with care. There was a slight bulge of the left coat pocket—about such an enlargement as one of the Everyman volumes might make.

HARRISON VICTOR came to his room in the hotel the next morning and sat in a corner smoking a foul black twist of an Italian cigar, turning his mustaches to more delicate points. He looked perfectly the part of Louis Desaix of the Sûreté.

"There's no note in the papers about the death of John Harbor," said Hamilton, in the midst of dressing.

"The body's been found, the Villa Men Sourir consulted, and John Harbor is at the morgue. The papers will carry no articles about the suicide."

"Suicide?"

"Of course. The gun was found gripped in his right hand."

"The girl put it there, and his gun was not of the right calibre to make the wound."

"My dear Hamilton, this is Monaco, where the skies are so blue and the sunshine so golden that people don't want to examine into every ugly little death. The authorities help to smooth things over. Suicides in the Monte Carlo gardens don't help the flowers to bloom. And then it seems that John Harbor was a very obscure fellow. No connections to bother about him. He'll be quietly buried and forgotten. This has happened before." .

A boy brought up a long white cardboard box. Hamilton gave the tip and opened the box when the messenger had left. Inside was a long sheaf of pink roses, freshened with a sprinkling of dew.

"Who's sending you flowers?" asked Victor.

"Old fellow, I'm in love. I'm taking these flowers for a morning call. Yes, a morning call. Because, last night I was swept off my feet, overwhelmed, devastated by meeting the beautiful Mary Michelson."

"You're a cold devil," commented Victor, without smiling.

"On the contrary, I'm burning with passion," said Hamilton, yawning. He was in his morning coat now, and he turned this way and that to examine his appearance. He was, in fact, a very trim figure, except for that slight stoop and forward thrusting of the shoulders. More than ever he looked, from behind, like a student, and from in front like an athlete.

"You know people don't go in for that sort of thing own here?" asked Victor.

"I'm an outstanding type," said Hamilton. "I'm one of those genial young asses who, having been raised in a certain way, never varies a trifle in any habit of his way of life. My mindlessness is so complete that I could never manage to vary my clothes according to my climate. And, this being the morning of the day, morning clothes are required. Also this stick."

He drew the beautiful, mottled Malacca through his fingertips, admiring its delicate luster.

"And these gloves of yellow chamois cleaned just enough times to fade them white. And the monocle, too. That's a real convenience. It can drop out of my fool face at an embarrassing moment and give me another second to compose my answers. Besides, I have an extra glass in my pocket that turns it into a good magnifying piece."

"You're an extraordinary smooth article," grinned Victor. "Do you never lose your face? I mean, do you always remember which face you're wearing?"

"No," said Hamilton. "Years and years ago when I was just a youngster—it must have been four years altogether—I forgot myself completely while I was sitting cross-legged opposite one of those black Sahara Arab sheiks. He showed me my error by reaching for me with a knife."

"He didn't harvest you?"

"You know, if you sit cross-legged in just the right way, your feet are always free. I kicked the sheik in the stomach and managed to get to his best camel. She was milk white, and she did all my thinking for me for three days."

"Are you off now?"

"Not until you approve of me?"

"You'll get a glance from every eye. You'll be well-known to half the people in Monte Carlo before the day's over."

"If I can keep attention fixed on my left hand, Victor, I can do wonders with the right. By the way, which was the room of John Harbor, over at the Villa Mon Sourir;"

"On the ground floor, the third door on the left down the main hall."

"And the girl's?"

"Mary Michelson's? She has the room opening on the second story loggia and looking out to sea. Hamilton, I know that you're a clever workman, but I want to remind you that already we have a man in jail for snooping about the Villa Mon Sourir. And Bill West is a clever fellow, too. Awfully clever."

"Of course he is. But he wasn't in love. You forget, Victor, that all the world loves a lover."

RIVIERA climate is as unreal as a colored postcard. Beyond the mountains lies the land of the cold mistral, but along the Ligurian coast a fringe of summer remains when all the rest of Europe is overcast with white winter. That golden warmth seemed to Hamilton, on this morning, more like a pictorial effect than ever before, a bit of expensive staging put on by the Casino to content its guests.

But the fragrance of the mimosa was real. It carried an honest touch of spring into the air. So he was breathing deep as he drove with the blue sparkle of the sea on his left and that delicate fragrance in his face. Coming down the Avenue de Monte Carlo, he took the Boulevard Albert Premier past the great bowl of La Condamine, and so on by the gardens and palace of the prince until he came out on the road to Beaulieu.

He was taking his ease in the car, with the top down and this warmth of the miraculous summer flowing about him. Okhotsk had been a different affair; and in a few days a new order from Washington might fling him half-way around the world on a new mission. Even that uncertainty was a delight to him, for it was part of the joy of the chase, whether he were the hunter or the hunted.

He turned left, now, into the road which wound among the glimmering boulders of Les Roches, and when he looked out through the trunks of the pine trees the ocean rose as a steep blue wall on either hand, about to flow inwards and close over him. The pink walls of Mon Sourir appeared, and he drove through the open gate with an odd feeling that the panels were closing automatically behind him. The drive circled around a tall cluster of mimosa trees. He stopped his car at the side and rang the bell of the house. The dark fingering around that bell seemed to tell him that the Villa Mon Sourir had abandoned the dignity of a private residence and become a public place.

A butler in gray-striped working jacket and apron opened the door to him. Hamilton gave his card.

"I am calling on Miss Michelson," he said.

"She is not in, monsieur."

"Not in? But I'll wait for her. I'm sure she expects me."

It seemed to him that the square, solemn face of the man forbade his entrance still, but he stepped forward with his witless smile and the butler gave back.

"This way," he said, and ushered Hamilton into a little waiting room. The open window of it let him see in a group all the inhabitants of Mon Sourir except Mary Michelson. They were seated in the spicy shade under a pair of stone pines, the gigantic Czech. Karol Menzel, Hans Friedberg with no back to his German head, Ivan Petrolich, the Russian invalid in his wheelchair, the beautiful young Rumanian, Matthias Radu, sleek and soft as a Levantine, or a woman. The Polish girl, Maria Blachavenski, was there, at the side of the huge George Michelson. and the Vicomte Henri de Graulchier was not seated but sauntered slowly about. He wore a loose tweed coat in spite of the weather and kept his hands in the pockets of it. He spoke with authority that had a caress in it, like one speaking to children, explaining difficult things with a restrained impatience.

George Michelson was saying, at this moment:

"The great southern valley of the Volga is the storehouse, the granary of the country, and if that were held securely—"

But here the butler, crossing the room to the window, said rather loudly:

"Is the light too glaring? Shall I lower the shade. Monsieur Hamilton?"

"It's very pleasant that way, with the sea breeze blowing in," he answered. "Will you put these flowers for Miss Michelson in water?"

The man carried the long box away, and Hamilton, taking a chair and lighting a cigarette, observed that he still could command a view of the interesting group beyond the window. They had altered a little. The hand of George Michelson was no longer raised as though about to emphasize an important point. Pale Maria Blachavenski no longer sat so eagerly erect. It was as though a stress were removed and the people were relaxing after the strain of effort. The talk was still about Russia, with the vicomte now holding forth in the lead.

"Come, Ivan Petrolich! You are a Russian. Maria, you are almost a Russian—"

"Henri, no Polish woman is a Russian. I beg your pardon, Ivan Petrolich, but a Polish woman is removed by thousands of light-years from a Russian."

"Ah, I understand," said the invalid. His head sank into the cushion at the back of his chair and his pale face was smiling a little. He had almost closed his eyes.

"You are both Slavs," said Henri de Graulchier. "And when we talk of race instinct, there is something more important than national boundaries, little national prejudices and blindnesses."

"Unless one is French, Henri, and then of course it is understandable, it is necessary," said Friedberg, the German.

"WE should argue peacefully," declared the vicomte. "And the point that I wish to make is that the Russians are not a melancholy people."

"Ah, come, come!" murmured Matthias Radu, the beautiful young Rumanian.

"I mean it, and I ask for unprejudiced witness. The Russian is not melancholy. He is simply Asiatic. Because he rubs elbows with the Occident and is different from it, he is erected into a mystery by the Western nations. His music, which contains some of the natural wail and minor quality of the Asiatic, strikes the Occidental ear as an expression of sadness. The contrary is the truth. The Russian is gay."

"These are simply statements, de Graulchier," said huge Karol Menzel, the Czech. "I know a good many Russians."

"You don't!" said de Graulchier. "Not at all!'

"Ah, I don't?" murmured Menzel.

"Certainly not. All you know are the educated upper tenth of one percent. And those are the people who speak French and English, drink more Burgundy than vodka, and have been expected by their European friends to be mysterious, day-dreaming, melancholy; expected so long that soon they are willing to play the part that is desired. Half Hamlet, half Gargantua. That is your educated Russian—again I beg your pardon, Ivan Petrolich."

"You always delight me with your aphorisms, Henri," said the Russian.

"Not aphorisms. I am telling you the truth. Open your eyes to see it. The real Russian, the peasant with his bit of land, is always happy unless he is starving to death. On half a franc, he knows how to make fiesta. There is nothing mysterious about him except the depth of his beard. Admit that I am right."

"There's no use disputing with him," declared Karol Menzel. "Since the days of Napoleon, every Frenchman has argued by Imperial edict."

They talked on, but there was to Hamilton only one thing of interest in this conversation, and that was the quickness with which it had been changed in temper. When he first located the group, it had been tense with attention to the words of George Michelson, who had been declaring that the Volga valley was the granary of Russia, and that if this district were held....

Well, held by whom?

It would have meant a great deal to Hamilton to have heard even ten seconds more of the speech of George Michelson. But suddenly—as if at a signal—the talk had altered, still flowing smoothly along about Russia, but totally diverted in significance, and devoid of any importance.

In fact, the signal had been given, either by the voice of the butler at the window or by his gesture as he lifted his hand to the shade. It was very significant. It meant that even the servants in this house were deep in the affairs of the masters; it meant that the master, the guests, the menials, every living soul in the Villa Mon Sourir was engaged in working towards a single purpose!

What was that purpose? Something which was the will of Japan, no doubt To he sure, exactly such a hodge-podge of nationalities might be discovered in a dozen pensions or hotels along the Riviera, where the world comes to recapture spring; yet it was noticeable that in this group there were representatives of Rumania, Czechoslovakia, Roland, Germany, France—all nations which bordered on Russia or had some vital interests in its future and the fate of its government.

Perhaps there were still other representatives—in the kitchen or the garage! Perhaps Estonia, Latvia, Finland and Sweden had sent men to this conference with Japan's Number One secret service agent.

Was he one of those men who sat there talking outside the window? A fellow who had been alive—though only in his early twenties—at the time of the Russo-Japanese War, would now be in his middle fifties at the least. Friedberg was old enough; so was George Michelson. They were the only ones. No, perhaps the smooth face of Henri de Graulchier made him seem a full ten years younger than the fact.

However, the great probability was that Japan's ace was well hidden from view. He was more apt to be an occasional visitor to Villa Mon Sourir than one who dwelt in it.

A TINGLING passed through the nerves of Hamilton. He knew perfectly that dramatic situation in the Far East caused by the swift expansion of Japanese population, Japanese ambitions, Japanese trade. They had a great floodgate opening for them in Manchuria; and even that bitter land would be a Paradise of opportunity to many of them. But they were not likely to rest content. They needed more and more soil. Their population would be a hundred million, before long—a hundred millions of intelligent, strong, active people, all welded into a single purpose.

Who could deny them? The Philippines were close to them, an ideal extension of their empire; Hawaii was not very far away. And if the fringes of China were already crowded with inhabitants—well, the inhabitants could be swept out and place made for the conquering Jap. But while these great schemes were in progress, the wisest course for Japan was to keep the Russian bear well occupied with domestic problems west of the Urals. With war, or revolt.

The picture grew in the fertile imagination of Anthony Hamilton. Villa Mon Sourir might be the nerve-center of the entire brain of Japan, at the present moment. And one wasp-sting, planted on the vital spot, might paralyze the will of a nation of ninety millions.

He rose, walked to the door, and glanced down the hall. The third door down—that was the room of the dead John Harbor. Hamilton, bending his head a little, tried to listen around the corners, since he could not look around them, and when he made out no sound near him, he walked down the hall. He realized that he might be making his last steps if he were discovered prying into the rooms of Mon Sourir—that is, if his first vague conjectures about the people in it were proved to be correct.

When he reached the door, he paused for another instant, then quickly opened it and glanced inside.

It was no longer a bed-chamber. It had been changed overnight into a living room.

THERE was no trace that the room ever had been equipped with a bed. A pair of comfortable sofas flanked the fireplace. A very good Persian rug with the famous pine-tree pattern on it occupied the center of the floor. On the window there was a pair of curtains of heavy linen, with peacocks embroidered on it in blues and in rich greens. A rather silly little bronze group of Zeus and Europa crowned the mantlepiece.

Hamilton closed the door and went back down the hall. There were reasons, of course, which the owners of the pension could give. They would declare that they did not wish to continue in the intimate role of a bedroom a chamber which had been rented only so short a time before by a man now dead. But what was really important was that, in this way, they were enabled to wipe out every identification mark of the man who had lived in that place. Not a footstep remained behind him—and the work had been done quickly.

An almost running footfall came up behind Hamilton.

He turned, and saw the butler bearing down. There could have been many ways to interpret the expression of the fellow's face, but to Hamilton there was only one: it was physical threat

"What's the way out into the garden?" he asked. "Awful lot of people out there, but I don't seem to find the way."

The butler paused. He was breathing a bit hard, and he looked down at the floor as though to disguise the expression which was glowing in his eyes.

"Mademoiselle Michelson, she is coming to see you," he said.

Hamilton returned to the waiting room and was not surprised to see the group outside the window had disappeared. He lighted another cigarette, because he needed to think. But before thought, in came Mary Michelson, carrying in the scoop of her arm a bowl that held the great spray of roses.

"Did you bring these?" she asked.

"They made me think of you," said he. "No blue in them, so they're all wrong. But somehow I thought about you when I saw them. So lovely and fresh, you know. Never can think of anything when I see a florist shop. But today I thought about you. Glad you like them."

She looked at the flowers and then transferred her smile to Hamilton. "I do like them a lot," she said. There was a certain gentleness in her voice that Hamilton had heard before, and he thought he recognized the intonation of a girl addressing a man who was patently a weak-wit.

Consequently he smiled more radiantly than ever.

"You know what I was thinking, Miss Michelson?"

"I'm afraid that I don't."

"Down at the Métropole they have a new orchestra. All-American like a football team. All champions. There's a fellow there on the slide trombone—you know how a trombone blasts the cotton out of the ears? But this chap makes it sing. Actually sing. You know, I thought we might trot down there and have a dance or two, one evening. Spot of dinner—and they have some fine old Pol Roget. Absolutely the stuff! Then we could dance a couple of turns. What do you say?"

"How sorry I am that I haven't this evening free!" said the girl. "You've been in England a good deal, haven't you, Mr. Hamilton?"

"Now, how did you notice that?" asked Hamilton, beaming. "Went to a school down in Sussex. You know the sort of place. Headmaster all full of algebra and Greek and gardening. Nothing heated except the entrance hall. Boiled in that and froze every other place. Chilblains. Great place for chilblains. Never saw so many chilblains. Hands absolutely purple with them. Good old England! You know—history and all that. Forbears, and that sort of thing. But I'd rather think about it and let the other fellow live in it."

"Would you?" she said. "Well—"

She kept on smiling, quietly, thoughtfully. She was seeing all the way through him. Or was it quite all the way? She was in very crisp white and the reflected light shone on the brown of her throat. Her smiling, he thought, was like an added color to the picture. In her hair there was a special radiance.

"Or, you know," said Hamilton, there's Ciro's, if you like that sort of thing. Wonderful cellar, there. Good music, too. We might trot around Ciro's for a while.

"There's so much to do here at the pension," said the girl," that I never have my work finished. So I never know."

"Ah, don't you?"

"No, I really don't."

"AH, but look here. You'll come out with me one evening, won't you? Never know what to say when I have to sit and talk. That's the reason they have music. A few fox trots in the air—they give a fellow like me a chance to entertain. You will come out with me one evening, won't you?"

"Oh course," said the girl.

"But soon, I mean?"

"I hope so."

"I know what it is—being busy," said Hamilton. "Used to travel with a valet and it wakened me early in the morning to think out something for the fellow to do, all day. Can't give a valet nothing to do. Corrupts them. Ruins them for their next master."

"Mr. Hamilton, I lead a very simple life here and—"

"A simple life can be the devil, can't it?" interrupted Hamilton, with his smile. "My Aunt Hester leads the simple life. In a barn. It used to be a barn, at least. At Worcester, Mass. Gets along with three servants. I know all about that. But all I mean is a simple party. Listen to some music. Trot around a little. Enough music to wipe out the silences. I never know what to talk about very well."

"I think you do—amazingly," said the girl.

"Ah, do you? That's nice of you. The fact is that I think we could get on. The moment I saw you, I thought we could get on pretty well. If you can put up with a silly ass like me. My Aunt Hester always says that I'm a silly ass."

He laughed his most vacuous laugh.

"Not at all," said the girl. "And of course we could get on. I want to see you very soon."

"The butler has my card, and I scribbled the telephone number of the hotel on it. You wouldn't give me a buzz, would you, when there's time on your hands?"

"Oh course I would. I'm so sorry that I have to look after things in the kitchen."

"Oh do you? Well, I'll trot along, then. Won't forget me, will you?"

"Of course not."

"Really, though? That's a promise?"

"Of course it's a promise."

"That's fine," said Hamilton. "It warms me up a lot. It's good to hear. This Riviera—you know—a lot of climate—blue and gold—all that—Casino—only silly girls. You know, the ones that won't listen to the music. Just chatter. I'll wait to hear from you, Miss. Michelson. Tell you what—I can whang a guitar. Quite a bit. And sing a little. Nothing to write home about. Untrained. But I'd like to sing to you, if you can stand it?"

"I want to hear you," she said.

Her smile had almost worn away before he got out. He could nearly hear her comments behind the closed door, as he stepped into his long, low-hung racer, and shot away towards Monte Carlo.

From the hotel, he sent for the agent of the Sûreté, Louis Desaix, alias Harrison Victor, who found him lounging beside a window in the westering, sir, drinking wine and eating Roquefort with crusts of French bread.

"I had to have you, Victor," said Hamilton. "When I found out that they had Château Lafitte, 1906—glorious year, eh? I knew that if I didn't have company, I'd finish off the bottle all by myself. Château Lafitte! 1906! My God, Victor, when you think of the fellows who spend their money for brandy and soda—"

"How long have you lived in Europe?" asked Victor, touching his, mustache-ends tenderly.

"That doesn't matter. I only need to tell hat I was raised on a farm. So things go deep. Things like 1906 Château Lafitte."

"Tell me a dash about yourself."

"Sometime, I'd like to."

"Sometime, eh?"

"Nothing personal,old fellow."

"Hell, no," said Harrison Victor.

He poured some of the wine into a glass, looked towards the. sunlight through the glass, and sniffed at the brim.

"Ah, God!" he said. "Why is it that France is so full of the French?"

"Otherwise," said Hamilton, "all the world would want to live here. It's one of the acts of the Almighty. I hope you have a religious nature, Victor?"

"If I didn't, how could I be in the service?"

"Exactly. I, for one, have a religious nature. In France, I take the French wine and leave the French."

Harrison Victor tasted the Bordeaux and closed his eyes.

Hamilton covered a bit of crust with a green bit of Roquefort and handed it to his assistant.

Said Victor, presently:

"They call Roquefort the drunkard's bread. Now I understand for the first time."

"There's the pity of it," murmured Hamilton. "We never can get drunk."

Victor sighed. "What did you find out?" he asked.

"The thing has to do with Russia. Japan's agent Number One is probably George Michelson, Friedberg, or Vicomte de Graulchier."

"De Graulchier is not old enough."

^Perhaps not. I though of that, too. But on the other hand, he's the only one of the lot who might be a Jap."

"Jap? He's perfect French!"

"You may not know all about the Japs. Perhaps you haven't lived in Okhotsk. Anyway, tonight I'm going to try to find out."

"How?" Victor Harrison asked incredulously.

"By entering Mon Sourir."

"Hamilton," said Victor," don't do it. Something tells me that those fellows would shoot anyone at night."

"Not a dog who's in love," said Hamilton. "And how in love I am! I've even asked her to spend an evening at Ciro's, and you know that costs like the devil."

THERE is hardly a thing in the world so clumsy, so malformed, so apt to speak with a voice of its own at the wrong moment, as a guitar. Anthony Hamilton decided that before he had scaled the pink wall of the garden of Villa Mon Sourir. A light tap brought from the instrument a groaning sound which would not die quickly. The felt in which it was wrapped seemed to retain the sound like moisture and cherish it whole seconds after it should have died.

In addition, the night was clear. Even frost could not have made the stars glitter more brightly, and in addition there was a half moon sailing like an ancient ship across the sky and throwing its golden shadow down the sea. From the top of the wall Anthony Hamilton contemplated that beauty without pleasure, partly because light was the last thing he wanted for his excursion, and partly because the top of the wall was guarded with fragments of broken glass, imbedded in the cement. Moreover, he saw a shadowy form approaching him through the little orange trees. He should, of course, have dropped back outside the wall into safety. Instead, being Anthony Hamilton, he dropped down inside the wall and scuttled to the shelter of a black shadow beneath a shrub.

Crunching footfalls came near him from one side; footfalls which were not echoes drew close from the opposite direction. The first man paused not three strides away. The second halted facing him. Hamilton, through the black openwork of the leaves, could see them both against the stars.

"All quiet?" said the first man.

"Too quiet," said the second.

They spoke in the Czech tongue, which was just a little odd for night-watchmen on the Riviera, and which strained the brain of Hamilton to the utmost. He had hardly more than a book knowledge of that strange language.

"What was that which came over the wall?"

"Nothing. What did you see?"

"A shadow dropped over. I only saw it out of the corner of my eye."

"A cat, perhaps."

"Or a man, perhaps."

"A burglar, you mean?"

"There are better things than money to be stolen here."

"No one m the world suspects this house."

"So we think, but the Head, the Master, does not think so."

"He calls 'fire, fire' so often that no one will believe him even when the flames begin to rise."

"It's better to talk about fire than it is to be burned."

"Well, what do you want to do?"

"Keep the eyes open and look about."

"For a man?"

"Yes."

"Begin here, then."

They separated. One of them walked straight towards the bush which sheltered Hamilton. He put a hand on the gun under his coat. The fellow halted with the leaves of the shrub brushing against his trousers.

"Nobody would try on a night as bright as this," he said.

"Nobody but a fool."

"Fools don't matter."

"Aye, and that's true. Come on, then, but keep your eyes wide open."

"Do you think I'd sleep on the job when I'm working for him?"

"No, because you'd never wake up, perhaps."

They continued their rounds in opposite directions. It was very odd indeed. Even the French police might like to learn of a quiet little pension which employed two private watchmen to walk the rounds ceaselessly every night, watchmen who talked such good Czech!

Hamilton waited until the footfalls were soundless, and then he walked straight across the garden. He avoided the gravel paths, leaping over them, because the most cunning step in the world, even the velvet paw of a cat, cannot help but make a slight rustling noise when it passes across gravel. The rest of the soil was dug up about the roses and the iris, of which there was an abundance, but Hamilton knew the cunning art of sinking his feet into soft ground without allowing so much as a whisper to sound on the air. In this way, taking long, slow, dipping steps, he crossed the garden and stood in the shadow under the wall of the house.

Voices were speaking inside the place. He could not dissolve them into words and he could not identify the speakers except when a booming laughter, resonant as a note struck on a great gong, came sounding out to him. Only the throat of huge Karol Menzel could have produced the sound. He had made on the mind of Hamilton an impression that grew with the passing of time. He was a sort of smooth-shaven Richard Lion-Heart, big in body and bigger still in savage potentiality. Among the voices of the men he could distinguish.. slightly. the higher pitch of women speaking.

That should mean that the loggia above him would be unoccupied—unless burly Czech watchers made the rounds of the house as well as of the grounds. He looked upwards to estimate the best way of approach.

AS convenient as a ladder, the bars of a window climbed in a great, half-decorative scroll towards the loggia above. He gripped the felt covering of the guitar in his teeth, and climbed. He would have been wiser, perhaps, to have left the guitar on the ground below, but in case of a crisis such as might happen, the guitar was really his passport, his proof and voucher of idiocy.

He climbed very slowly, though even so the infernal guitar gave out certain murmurings and moanings as though ghostly hands were thrumming it. Now he stepped over the low wall of the loggia and entered the shadow cast down from the moon. The cold of danger was in that darkness.

A glance over his shoulder showed him the dusky sea, flowing with a quicksilver brightness down the path of the moon. A sail blew out of nothingness, stood black against that path and slid away into dimness again; far out a thin line of lights marked the passing of some big passenger steamer.

The loggia was full of chilly little whisperings from the sea breeze in the vines. Some pots of large, strange-shaped flowers stood along the foot of the wall. There was a mat of woven grass and a long bamboo chair for bathing in the southern sun. Beyond appeared a double door. The glass panes of it winked at him like a dozen black eyes. He tried the handle. It was not locked, and he pulled half the door open, slowly, slowly.

In spite of all that care the door made a little trembling jingle of sound; and out of the darkness laughing voices were suddenly loud. To his sharpened senses, tongues seemed to be speaking in the very room before him, mocking the stealth of his entrance; but of course that was illusion. By degrees he placed the noise at its proper distance down the stairs. For the inner door of the room was open.

That was tenfold unfortunate. If he closed the door, a passing servant might notice the change. If he did not close it, he was apt to be seen at any instant as he began his search. One of those queer, senseless panics which he had known before swept over him. As the years went on, his nerves did not grow better. They became distinctly worse and the time might come when he would betray himself by a shuddering palsy of fear in a crisis.

He moistened his lips and took hold of himself with a firm grasp, frowning a little. Then a ray from his pocket torch—it was hardly larger than a fountain pen—cut the blackness like a knife. If by chance he were seized and searched, he would be damned by the possession of that clever little light, perhaps.

The ray glanced over the rough yellow satin of a bedcover, over the blue wall-hanging at its head; it glimmered across the mahogany top of a table, flashed like a startled eye in the triple mirror on the dressing table, touched the chairs right and left. In a moment the plan of the room was mapped faultlessly in his memory. He could switch out his light and walk as though by daylight from place to place, secure of not touching any obstacle. In Okhotsk he had learned that art of moving in darkness with the surety of the blind.

Under the mattress of the bed, in the drawers of the dressing table, under an edge of the rug, somewhere in the closet, in the adjoining bathroom—through the half-open door he had caught the sheen of porcelain—in any of a dozen places he might be able to discover what he wanted—that little Everyman volume of Speke's famous "Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile." It was so important that a dead man's pocket had been picked to obtain it. Now Hamilton was determined to find the true reason for its significance.

He was about to start towards a small hanging shelf of books near the fireplace when he heard a soft pulsation—a rhythm rather than a sound, which passed down the hall. He shrank back towards the door to the loggia. But it was too late to escape that way. He was still long steps from it when a thin silhouette appeared against the obscure gloom of the hallway; then the electric lights flashed on.

A gray-headed man with towels over his arm went with a soft whisper of slippers straight into the bathroom. His head was bowed a trifle, thoughtfully. Hamilton, as he disappeared, sank on his knees behind the back of a chair.

The light in the bathroom, clicked off; the whispering step recrossed the room. Once more it was snapped into darkness; but still Hamilton remained for a moment on his knees, taking breath.

When he rose, making sure that nothing stirred outside the vague gloom of the inner doorway, he took an instant for thought. It might have been that the servant, going on the routine of his work, had seen nothing living in the room. Again, if it were true that every member of the household staff was a trained secret service worker, as Hamilton suspected, the man might have been aware of Hamilton instantly, but have gone on his way with an automatic calm, retreating to cut off the stranger's way of escape. The alarm even now might have sounded. Downstairs, not a voice was heard—then a subdued murmur of laughter.

Perhaps they were laughing as they received word that a stranger had dared come into the lion's mouth.

Still, Hamilton went straight forward to the hanging shelf of books because there was a decided understratum of the bulldog in his nature. The torch light he ran across the books in that case found them all volumes of Everyman, all of them dull green. And one, just to the right of the middle section, bore the title of Speke's "Journal!"

HE had it out instantly. He was by no means sure that this was the identical volume which he had seen in the possession of dead John Harbor, until he noticed a deep wrinkle at one corner which might have been caused by a fall. He would not have been able to mention that peculiarity if he had been asked to describe the book, but now he remembered it by touch. This was the very volume which he had taken from the coat pocket of Harbor!

He opened it swiftly, not to the text but to the fly-leaves, playing the slight radiance of his torch upon the paper, but there was not a mark either in pen or pencil, however faint!

Sighing, he shook his head with a frown and fluttered the pages of the book. A small white slip disengaged itself and fluttered away like an awkward moth. He caught it out of the air. It was a bit similar to those on which Harbor had made his notations. On it appeared the swiftly scrawled column of figures, except that there was no line for addition at the bottom of the sheet, like the following:

336 — 211

469 — 172

436 — 64

The answer struck him suddenly, with a shock like that of remembered guilt. It was simply a book code and the interpretation of the mysterious numbers which John Harbor had written down in the Casino was, simply, numbers of pages and of words on pages.

He turned to page 336 and, counting from "we hoped would soon cease to exist " at the top of the page, he got down to word 211.

"Tolerably."

That word would probably make sense in a message. It was a beautiful start, but of course he had to check the result. Very swiftly, because his trained eye had learned to calculate with a smooth speed, he reached word after word and found himself writing out a sentence:

"Tolerably Burial To To The—" No, there was no sense in that at all.

He went back and added, to his counting, the title words at the top of the page, on the left, always, "Source of the Nile," and on the right the sectional topics.

In this way he reached the following word group:

"Indifferent Chiefs The Villagers Fact Men Arrive Customs."

It seemed to have a vague sense. If it was a collapse telegraphic form of expression it might mean that "indifferent chiefs" had some sort of relationship to "the villagers." But "men arrive customs" was a stumbling block.

He lowered the book and closed his eyes. Down the stairs the voices were carrying on merrily. A very thin fragrance of tobacco smoke ascended to his nostrils.

Then he started his work all over again. He included this time, not only the titles at the tops of the pages but also the page numbers, including the numbers as words to be counted. In this manner he got at the following message:

"Opportunity In England Killed Rely On New Diplomacy."

A fine sweat burst out on his face. He set his teeth over an exclamation of triumph.

An opportunity in England had been destroyed. They must rely on a new diplomacy!

That made sense, perfect sense. It meant that in a single night's work the mass of copied messages which Harrison Victor had accumulated could be turned from naked figures into speaking words. It meant that Tokio had been stung to the quick—if indeed Tokio were at the bottom of all this. It meant that he, Anthony Hamilton, had scored another tremendous success—if only the brilliance of his work would be appreciated in Washington. And at least one of the brains there was not asleep! The suddenness of his triumph would be a convincing thing, after Victor and the rest had worked so long!

He felt an imminence of something—a danger coming—and then through the trance of exultation, he heard light footfalls coming very rapidly up the stairs.

He replaced the slip inside the pages of the book, slid it back into its place on the shelf, and glided to the door. The footfalls were very near, now, but he used a precious second or so of extra time to push the door open silently, and then, catching up the infernal burden of the guitar, he stepped out onto the loggia and shrank back against the wall.

AT the same time the lights went on inside the room. He could see beautiful Mary Michelson in a dress of clouds of smoke-colored lace, with a red silk wrap thrown over her arm. She was singing softly, smiling as she sang.

Well, however exquisite, she was one of them. She would have to be involved in their ruin, when he managed to compass that. And it would go very hard if out of the mass of notes in the hands of Harrison Victor, he did not manage to build up a charge of espionage against this whole crew. The French system of justice worked with wonderful precision in dealing with such cases. Sentences were dealt out quickly, and no sentence was short.

Mary Michelson, her father, the pale Russian invalid, thin-faced Maria Blachavenski, overbearing Henri de Graulchier—they would all be erased from the scene at a single stroke!

He retreated to the side of the loggia and was about to swing himself down onto the window bars beneath when he heard a voice saying:

"Well, he could have gone up this way?"

"Where?"

"Along the bars of the window, fool!"

"That's true."

The two Czechs were murmuring quietly together.

"And then through the door of Mary's room. It's never locked, day or night."

Very odd that two hired night watchmen should refer to their mistress by her first name!

The thing was as perfect as a blossoming flower. It was rounded and beautiful and complete. Every man and woman at Villa Mon Sourir belonged to the group of international plotters.

The fly in the ointment was that the retreat of the spy was cut off neatly and hopelessly. If he stirred from the loggia, he would be seen by the two men. If he attempted to withdraw into the room—why, there was smiling Mary Michelson, who, with one outcry, could bring a swarm of hornets about him.

There was one device left. The childishness of it set his teeth on edge, but stripping the felt from the guitar, he reclined in the bamboo chair and began to sing, softly, gently touching the strings of the guitar, that popular song about "the wavering ocean" and the "flood of his emotion," with "eyes" and "rise" and "skies" all neatly rhymed in the middle of the chorus.

He had about reached that spot when the door of the bedroom was thrust open and Mary Michelson appeared, with one hand behind her. He could guess what that hand was holding. But at the sight of her, he closed his eyes, bent back his head, and gave his whole soul and his whole vocal strength to the silly words of the song.