RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

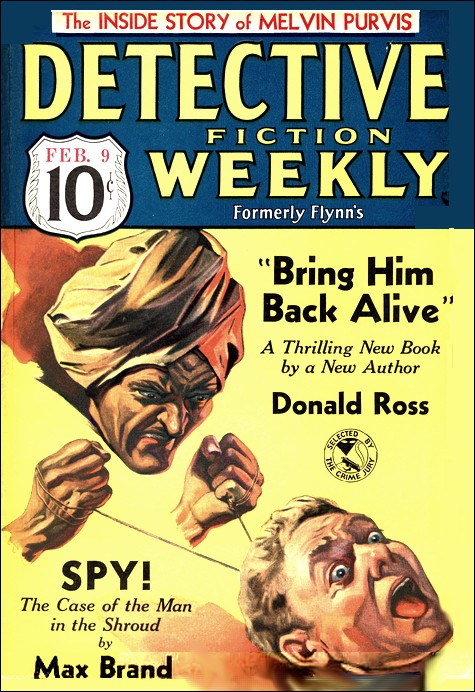

Detective Fiction Weekly, 9 Feb 1935,

with

"The Case of the Man in the Shroud"

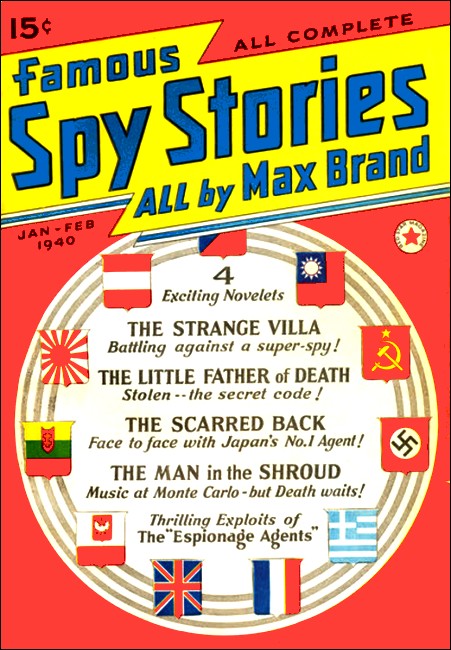

Famous Spy Stories, Jan-Feb 1940, with

"The Man in the Shroud"

"If he should come to, you have your two hands, Karol," de Gaulchier instructed.

In a Sinister Cabaret the Dancing Feet of Anthony Hamilton

Tap Out a Message of Life or Death for an Uncrowned Czar.

ANTHONY HAMILTON, head of the U.S. counter-espionage service, flew to Monte Carlo when it was rumored that the Number One secret service agent of Japan, Henri de Graulchier, was planning a coup that would bring on another World War.

At the Villa Mon Sourir, de Graulchier sheltered the Czarevitch [1] of All the Russias, who had miraculously survived the massacre of his family by the Soviets. A hetman of the Cossacks was being brought to Monte Carlo to convince himself that his Czarevitch was still alive. He would go back and start a revolt in Russia. That would give Japan a free hand in the Far East.

Hamilton could enter Mon Sourir by pretending to be a playboy and fool, hopelessly in love with Mary Michelson, the beautiful agent of de Graulchier. Thus the American agent managed to kidnap the Cossack hetman, and to turn the Czarevitch himself over to the grim agents of the "Gay Pay Oo"[2], the Soviet secret police. He had saved Russia from revolution and Europe from another World War.

But he is determined that neither the hetman nor the Czarevitch shall pay for his success with their lives. He releases the hetman, and shows him how to win a pardon from the Russians. And Hamilton is now trying to rescue the Czarevitch.

[1. Modern English transliteration: Tsarévich. Obsolete transliterations and incorrect Russian names used in this novelette have been left unchanged. —R.G.]

[2. GPU. Gosudárstvennoye Politícheskoye Upravléniye (State Political Administration). . —R.G.]

HARRISON VICTOR, besides his name of Louis

Desaix in the French

"Harrison," said Anthony Hamilton, "why do you keep yourself sweating in an outfit three times too heavy for the Riviera climate?"

"All good Frenchmen always dress till they're in a sweat," answered Harrison Victor. "The great thing to do about a chill is to prevent it. But never mind that. There's something for you to sweat about. I've trailed Koledinski, the Cossack hetman the Japanese secret service brought here to meet the Czarevitch, and who was to go back and start a revolt against the Soviets. He's left Monte Carlo, and taken the Blue Train for Paris."

"I'm glad he's gone. He wasn't alone, though, was he?"

"Do you think the Gay Pay Oo would let the old Cossack travel around entirely alone? The Soviet secret service is not so stupid. No, there was a handsome young Greek along with the Russian. That Greek is an agent of the Gay Pay Oo, of course."

Hamilton closed his eyes while he counted results.

"That means Koledinski has been to the Russian, consulate with his faked-up story, and the consulate has handed him over to the Gay Pay Oo. They swallowed his story. He told it exactly as I suggested, and the Russians are convinced that he is, the devoted patriot, ready to die for the Soviet Union."

"I had him tailed to the Russian consulate," agreed Harrison Victor. "Go on. Tell me what else happened."

"When he told them that he had seen the son and heir of Nicholas II alive—that Ivan Petrolich was really the Czarevitch—they were not quite as shocked as he expected them to be. Because, of course, they knew it already. But if they've taken Koledinski into their midst it means that the Czarevitch is still alive, Harrison. It means that instead of cutting his throat, the Gay Pay Oo reserved him for some other purpose. And they want near him just such devoted Bolos as Koledinski."

"It means all of those things," agreed Harrison Victor. "What else does it mean?"

"It means that while the Czarevitch lives, Japan still has a chance of carrying out her plan of putting him back on the throne of the Russias... That would mean a revolt in Russia, and while Europe was burning up with war, the Japanese could gobble up China."

"It means that, all right," agreed Victor. He polished and pulled his mustaches with delicate finger tips.

"Then the Japanese—I mean, that devil de Graulchier, Japan's Number One secret service agent—must not know that the Czarevitch is alive, and that Koledinski is heading straight for him."

"Unfortunately," said Harrison Victor, "as the train pulled out I saw in the crowd that pretty-faced snake of a Rumanian—that Matthias Radu. He was watching Koledinski. Which means that de Graulchier will know at once that the old hetman is on his way to Paris to join the Czarevitch. Which means that de Graulchier will certainly be in Paris himself before long. Which means you have reason to sweat."

Hamilton lay back in his chair and began to sing softly.

He kept on smiling, though smiles were not what he felt like.

"I thought of that," he said at last. "I knew there was some danger, but I couldn't imagine that de Graulchier would be so omniscient."

"He probably has a spy in the office of the Russian consulate."

"He may. And now the whole dance starts all over again."

"There's one good point," said Harrison Victor. "De Graulchier himself can't mix into the investigation too deeply. He can't show himself too much, I mean, because by this time the Gay Pay Oo knows what he is. Most of the other men at Villa Mon Sourir are known, too. If they come too close to the Gay Pay Oo they'll be spotted."

"De Graulchier has a thousand agents," said Hamilton.

"But his best men are at Mon Sourir."

"That's perfectly true, and the Russians have spotted the lot. Disguises are not a great deal of good in these days with agents trained to remember the look of the back of a head, or the angle of the neck, or even the contours inside an ear. A disguised man is usually just uncomfortable, not useful."

Harrison Victor nodded. "It looks as though de Graulchier will have to work with second-hand brains on this job," he said. "His first-class outfit is no use to him. But what do we do?"

"Get to Paris ahead of the Blue Train and trace Koledinski to whatever place the Gay Pay Oo takes him. My bet is that the Czarevitch is already safely hidden away at the same destination."

"That poor devil of a Romanoff!" murmured Harrison Victor. "I pity him, Anthony."

"If we can get him free from this danger," said Hamilton, "he'll probably be thoroughly shot in every nerve and willing to drop back into oblivion, like a stone into dark water."

THE telephone rang. He answered, made a sign to Harrison

Victor. Then was saying: "Certainly, de Graulchier. My dear

vicomte, why not come right up to my room with

Mary?"

A moment later he hung up the instrument.

"Not de Graulchier and Mary Michelson! Not coming up to your room, here?" exclaimed Victor.

"A little unconventional," said Hamilton, "but why not? I wish to God that I played the game as de Graulchier plays it. He'd never walk out of this room again alive, and Japan's secret service would be crippled for years, at least."

"Listen!" exclaimed Victor. "Why not play the game along de Graulchier's lines? Murder is his trump card. I've got May and Drew at hand. They can be ready in two minutes, There are twenty other ways of working the trick. Something in de Graulchier's drink that will drop him in his tracks an hour later—"

"Steady, old fellow!"

"After the torture he gave Bessel? After the murder of poor young Carney that he ordered? I'd kill him like a rat! Anthony, be reasonable!"

"Be reasonable, even if I hang for it, eh? I feel as you do, Harrison. But not murder! He's coming here freely, and he's going to leave freely."

"I know," sighed Harrison Victor. "You won't play it the other way. But one of these days being honorable among thieves is going to do you in. I'll get out of here, and let you handle them. But—"

He went towards the door, but Hamilton halted him.

"They won't be here for another minute. Look me over." He had been throwing off his sack coat and donning a very costly Japanese kimono of black silk figured over with an exquisite arabesquing of gold. Now, sleeking his hair back and fitting a monocle into his eye, he did a dance step, and faced Victor. "How do I look?"

"Like a rich young jackass of almost any nation, with an empty head and educated feet," said Harrison Victor. "Anthony, how do you do it? Even your face is new!"

HE went out of the room hastily. Hamilton tossed a polo

magazine onto the couch, opened a detective story and laid it

face down on the desk, and then heard the rap on the door. He

opened it for them, and saw Mary Michelson against the dimness of

the hall, like a jewel against velvet.

She came in with her best smile, and not an assumed one, he was sure. The chiefest of all mysteries to him was: how she could be genuinely fond of him, when he had showed her nothing but the feather-brains of a witless young spendthrift.

De Graulchier's swarthy face was at its most, amiable, but even at the best there was always a hint of a sneer in his expression. He had a way of striking straight into the heart of an idea. He struck now, before there was even a chance to sit down.

"Anthony," he said, "here's Mary in an agony because a tenth cousin of hers has been made to disappear by some sort of a conjuring trick. Every man at Mon Sourir is at her service, but she stops crying long enough to say that there is only one man who really can do the work: Anthony Hamilton! So here we are."

"Did you say that, Mary? Did you mean it?" exclaimed Hamilton, "Why, of course you're right! Anything—I'd do anything for you. But who is it? Disappeared, did you say? A cousin?"

"Ivan Petrolich," said the girl. She looked wistfully at Hamilton. "Right out of our garden the other day. You know, when we found that poor fellow out of his head in the cellar room at Mon Sourir? When we came up stairs Ivan was gone—vanished—and the big fellow with him was gone, too. And there isn't a trace! Not a trace!"

"I'll go out and look about," said Hamilton. "You know, I've read about such things. You look for finger-marks on doorknobs and things. You hunt everywhere for foot-prints —always find something—"

"Yes, in books," said de Graulchier. "But this is not quite a story. In a word, Hamilton, the Gay Pay Oo has snaked Ivan Petrolich away!"

"Hello! That's the Russian outfit that cuts your throat while you're laughing at their last joke? What jolly rotten luck for poor Ivan Petrolich! Look here, Mary. I'm hideously sorry. Do let me come out and take a look around—"

She said with a queer abruptness:

"Anthony, doesn't it turn your blood cold to think of working against the Gay Pay Oo?"

"Blood cold? Of course, of course! But I'd rather face the Gay Pay Oo than an audience all settled back in its seats ready to sneer at you before you sing your first song. I remember once I had a really hot number; brand new dance and a song called—"

"You're going to work with Mary?" demanded de Graulchier. "Even if the trail goes as far as the moon?"

"Ah, a trail?" said Hamilton. "Of course! Regular hunt I hope it'll! be."

"Anthony," said the girl, "I think the first step is from here to Paris. The vicomte has managed, to get hold of a plane for us. Will you make the trip in the air?"

"Why, that's where I live!" cried Hamilton. "When do we start? I mean—it'll be the two of us only?"

"Yes. I'll be ready to go inside an hour."

"I'll be there, then! Give the directions. I'll be there, flying suit and all. And wrap up' warm. It's going to be cold above the mountains. I'm sorry Petrolich disappeared, but this means more to me than a trip to the moon!"

THEY were hardly gone before he had Harrison Victor back in

the room.

"De Graulchier was tied in a knot, exactly as we thought," said Hamilton. "And the result is that he's turning me loose on the trail of Ivan Petrolich, so-called. Turning me loose with a brain to go along and tell me what to do. And that brain is to be Mary Michelson!"

He laughed, but Harrison Victor said:

"He thinks you're a fool, but a cool-headed fool. But how long will you be cool-headed if you have Mary Michelson along with you? You'll step out of the song-and-dance into your own character, one day; you won't be able to keep it up, Anthony."

Hamilton merely said:

"Think of the calculation of that fellow de Graulchier. What a brain, Harrison! What a beautiful brain! But if I can act my part, we're going to tie the hands of the vicomte behind his back, before long; and then I think that the Gay Pay Oo will do the throat-cutting."

"What do I do while you're gone?"

"Watch Mon Sourir. See how many of them leave. De Graulchier will go to Paris, of course, and lie low. Some of the others may follow him. Send me word. You know where to address me there. Tell May and Drew to fly up today. I may have use for them."

"Old son, how do you feel about trailing the Russian bear with a girl to slow up your steps?" said Harrison Victor with anxiety.

"Slow it up?" Hamilton laughed, "Harrison, Mary and I are going to dance through this whole number!"

IT was a fast little monoplane with a little too much engine for its spread, so that there was a good deal of vibration and a lot of roar from the motor, but the speed was the thing that Hamilton knew and loved in the air. Mary and he rose out of the golden warmth of the Riviera, shot over the mountains, and then slid up the valley of the Rhone into the twilight of January and the cold. The electrically warmed suits kept them comfortable enough, but a low ceiling formed overhead and he had to fly in a narrowing wedge of clear air, coming closer and closer to the ground as they neared Paris. Snow began to fall, throwing dangerous shadows down from the clouds, but the girl paid no heed to trouble.

She herself was an aviator, he knew, and every bit of the danger must have been apparent to her. But she lay back in the padded seat with a perfect indifference, and such a smile as she might have worn while sunning herself on a beach.

He was beginning to understand her better with every mile he flew. She liked him. That was one small part of her pleasure. She was assigned a task great enough to shake the political world of Europe, and that was another part of her enjoyment. But most of all she was basking in the delight of all adventurers—danger itself, and for its own sake.

Their conversation was limited chiefly to smiles and gestures until they shot down onto the field of Le Bourget. A little later they were in a taxicab bound for Paris. She was as quiet as when the roar of the motor had stifled talk, but now it was thought that kept her silent. Hamilton watched her, smiling, but taciturn for once, despite his role of playboy.

"Where will you stay?" she asked.

"The Crillon, I suppose," said he.

"I'll go there too, then. We ought to keep fairly close."

"Ought we? I'm so happy, Mary, that I'm apt to break. It's exploding in me."

"Do you know that we may both be dead before we're a day older?"

But she kept smiling a little, watching him; and then smiling more and more.

"But what a lot of killing we'll take!" said Hamilton. "And what a day it's going to be! If we're not called back for an encore—well, anyway we'll enjoy the parts we play."

Then the dullness of Paris suburbs finished flowing about them. The lights increased; the people thickened in numbers. Snow was slanting down in a brisk wind. It whirled in brilliant circles about the street lights and made the pedestrians walk with their heads awry. But that strange quickening of the blood which always means Paris was beginning in Hamilton. Only the girl remained withdrawn a little from the moment, as though there were a glass pane between them.

When they got to the hotel she said: "There's going to be a bit of time before the Blue Train gets in. Can you meet me half an hour earlier than we arranged?"

"At the station?"

"No. Just two blocks down the Rue St. Honoré you'll find a taxi pulled up at a corner, waiting. A green car. I'll be inside it."

HE got a room and living room in the hotel and went up. Then

through the snow-streaked windows he looked out on the great

circling lights of the Place de la Concorde and watched the rush

of traffic which pours day and night into the throat of the

Champs Elysées. History was rushing about him in the same way,

new and vital history in the current of which he was being

carried ahead. The past is always so clear, he thought, but every

new moment is dark—and may be the last. Mary's moves were

planned in detail. His must depend on inspiration.

He had a sandwich, rested flat on his back for an hour, then got into a fur-lined overcoat, slipped an automatic into an inside pocket, and went out to keep his appointment with Mary Michelson. He had a queer certainty that she would not be there, and the thought filled him with a hollow panic. He found himself hurrying, straining his eyes.

Then he sighted a car at the right corner. Yes, it was green. He began to walk more slowly, breathing deep. Now the driver was opening the door for him—a typical pirate of a French taxi driver. They have driven cabs to the Battle of the Marne, and they all look the part. And they still drive through the crowded streets of Paris as though on the way to another battle.

He had to look twice before he recognized Mary. It seemed to be nothing but the make of the black hat she was wearing that made the difference —that and the angle at which the hat was worn. But she was made up in such a way, he saw as he settled down beside her, that her mouth and eyes were much altered. She looked older; she looked keener and gayer; she looked like Paris. Perfect Paris. The kind that never stops wearing an air. The kind that flashes a new facet at every moment.

The driver, without waiting for an order, started the car.

"What have you done to yourself, Mary?" asked Hamilton. .

"Just made myself a little more at home in the strange city," she answered. "Do you hate it?"

"I hate it," he admitted.

"We have to be with the crowd," she said.

"I know it," said Hamilton. "But you know how it is. The old familiar faces, what?"

THEY reached a small, winding street. The car stopped by the

curb. The driver, getting out, tossed off his overcoat and cap

and put them through the door into the back of the cab—in

Hamilton's very lap. With a soft hat on his head, wearing a

raincoat, the fellow walked away. He had not spoken.

"You put on the overcoat and cap," explained the girl. "And then you become taxicab driver number—well, I've forgotten the number. It's rather a queer little taxi, Anthony. It has a quiet motor, you notice—hardly makes a whisper unless you let it out. And when you let it out, it will do just an even hundred miles an hour."

He felt as though the ghost of de Graulchier were leering in at them through the glass of the car's windows. Obediently, he made the change. "You know Paris, or shall I tell you the way?" she asked.

"I know spots of it. You've been here a lot, Mary?"

"I've learned it by heart," she answered.

She was folding his cast-off coat as he stepped out. He felt the cold of the air soaking through his clothes like icy water. The overcoat he was in now was too big, and the material was hard as canvas. It would keep out the snow, but not the gale.

"Have you a gun?" asked this new Mary Michelson.

"Forty-five caliber," he said, turning and speaking over his shoulder,"and seven slugs that don't know how to miss. Nobody asks that old gun for an encore."

"Good!" she said. "Shall we start along, Anthony?"

As she had said, the car was unlike the usual taxi. Under the hood lay a flood of power. He took the cab delicately through the traffic. A touch on the accelerator made it leap like a horse under the spur. He went like the wind to the Gare de Lyon, turning in from the Quai Henri IV towards the sooty, pretentious building. Other taxis were speeding towards the station.

"Slowly! Slowly!" called the girl. "We're a little too early. Up the Avenue Ledru and then around by the station again."

He did that, and came past the Gare de Lyon just as a river of travelers poured out. Mary Michelson told him to pull over to the curb, but he had hardly reached it when a man on the sidewalk drew a handkerchief and mopped his face with it. Very strange that he should be perspiring at such a rate in the cold of the night; strange, also, that the movements of the handkerchief were regularly irregular, so that it might have served as a wig-wag message.

Mary Michelson called out at once:

"Ahead, Anthony! A red cab! There—you see the number? Get up beside it at the first traffic stop, if you can! Hurry! Hurry!"

He was beside that red cab almost at once. And seated in the back of it he saw a straight-backed young fellow, and the unforgettable face of the Cossack, Koledinski. The white eyebrows gleamed in the light of a street lamp like two streaks of silver.

De Graulchier, then, was following Koledinski in the hope of being led to the Czarevitch? It must definitely be for this reason. He and de Graulchier, therefore, became for the moment allies. The winner would be he who could trick the other at the last moment. The brains of the chief of the United States' counter-espionage matched against the wits of the Number One of Japan's secret service.

The traffic went on, with a rush.

"Follow the red cab—not too closely —but don't lose sight of it!" called Mary Michelson. "It means everything!"

UP to the Place de la Bastille. Snow kept slanting down, turning to slush that denned the tracks of the whirling tires. Of the great column, only the lower part was easily visible and the statue above walked like a shadow through twilight. Then the Place de la République and along the Boulevard Magenta. They were in Montmartre with the misty towers of the great church rising far above; they passed into the whirling round of the Place de Clichy. The red cab turned left, slowed in a jam of many other cars, went on.

An instinct made Hamilton bring up his machine close to his leader. And •the other cab he found empty!

"The two have gone!" cried Mary Michelson in despair. "What shall we do, Anthony? How could they have gotten out in that jam of machines?" Then she added:

"We'll stop over there at the right. The two of them might be in that last block. They might be in this one. I'll take this and walk around it. You take the one back there. Be at the cab in ten minutes, five minutes. Look, look, look for either of the two faces. But don't seem to be looking. Anthony, can you do that?"

He was standing on the curb beside her, now.

"Why, si, course I can do it!" he said. He sang:

"It isn't your size,

But the use of your eyes—"

"Please, Anthony!" And he was still, as she laid a hand on his arm and looked earnestly at him. "If anything happens to you—Anthony will you be careful?"

He sang:

"My dear, whenever you take the air,

Handle yourself with a great deal of care—"

She laughed, and left him suddenly. He, glancing after her, saw men stop and lift their hats—and then turn to watch her as she went past them while they were sill speaking. A slight nausea pulled at the face of Hamilton as he went back to the next block. A flare of lights spelled the name of a large cabaret: "Le Moskovite." Beside it he found a telephone booth and rang Drew, one of his agents.

"Any news?" he asked.

"Harrison Victor and Louise Curran have just blown in," said Drew. "Nearly everybody in the villa of Mon Sourir vanished—and they disappeared in the direction of Paris. So Victor came along with Louise. He thought you might need him."

"I do, and now. Take May and Harrison Victor. Leave Louise at headquarters to gather the reports. Come down here to Montmartre. Find 'Le Moulin Noir.' In front of that dive Koledinski and his Gay Pay Oo escort disappeared. Not inside it. They wouldn't do anything as patent as that. They're somewhere in the neighborhood, I imagine. That means that Ivan Petrolich is somewhere around here, also. De Graulchier's system is functioning. I think he has men all over Paris. Search everywhere for Koledinski or his companion a straight-backed young fellow with pale hair that has a shine to it, and his head carried a little to the right. About six feet; a hundred and seventy; age twenty-five; smile crooked on the left side. I'm here with Mary Michelson, searching the streets, but we may not cut deep enough. That's all."

He got around the block on the double-quick, watching faces; and returned to the cab just as Mary reached it.

"No luck!" said he.

"Quick!" she answered. "Jump in and start. There's a man in the next block—no, not the ones we've been following—"

She was inside the cab and he started away at once.

"There on the left. You see the big man with the fur collar?" called Mary Michelson. "Follow him—watch him, Anthony!"

He drove very slowly. The fellow in the furred overcoat was stepping with a long stride. Something about his shoulders and the carriage of his head was familiar to Hamilton. And now, as he drew level, he recognized the features of the Grand Duke Boris, who had come so far in order to serve the last Romanoff and who had fallen under the terror of the Gay Pay Oo. He was their man, now.

"Watch him!" murmured the girl from the darkness of the cab. "There —you see him taking the taxi at the corner? Follow that!"

"Did everybody in Paris have a hand in snaking your cousin away, Mary?" Hamilton asked.

"Follow! Follow! Follow!" she pleaded. "Watch carefully, Anthony. Please be careful."

It was harder to follow the trail of that cab than it was to keep at the tail of a flying snipe. A every corner there was a turn, until the car drew up in a narrow lane full of windings.

It was stopped by the time Hamilton came in sight, and he had come around the corner so quickly and with such an impetus that he could not stop behind the other car without a great noise of brakes. Therefore he drove slowly past and saw, inside the other machine, no driver at all—but only Boris himself, his massive head fallen as if in sleep.

"Having a sleep for himself," said Hamilton over his shoulder. But it was not sleep; he knew that.

"STOP here," she commanded. "Now go back and ask the man in

that car for a match. Speak to him in some

way—look at him, Anthony."

He went down the pavement, his feet slipping at every step in the newly-fallen snow. And when he came to the halted cab, he tapped on the window glass.

The Grand Duke Boris did not stir.

Hamilton opened the door and leaned inside.

"Pardon, monsieur!" he said.

Boris of Russia did not move. Hamilton heard a very light sound of dripping. He flashed his electric torch on the floor of the car and saw the slow drops falling into a pool of red. One gloved hand, fallen from Boris's lap, seemed reaching down towards the blood; but he would never complete the gesture.

"Gay Pay Oo!" murmured Hamilton to himself, and closed the door as he stepped back.

He returned to the girl and told her:

"That trail's finished, I'm afraid."

"Anthony, is he dead?"

"Yes. Stabbed in the throat and breast."

She lay back against the seat. "The Grillon!" she directed, breathlessly.

He had plenty to think about as he made the return journey.

"No, the Rue St. Honoré first," she said. "Stop at the corner where we took the car."

The Gay Pay Oo, Hamilton decided, had accomplished some very definite and important step. Their need of Boris was less, now, than their fear of his knowledge; and Hamilton wondered if that knowledge concerned the death of the Czarevitch.

At the appointed corner he stopped. A man stepped out from a doorway at once.

"I take the driver's place, monsieur," he said. It was the same fellow who had turned over the car to Hamilton. He resumed his cap and overcoat while Hamilton, in the back of the taxi, donned his own things.

"It's a little thick for you, Mary," said Hamilton. "You know what you ought to do. Tell the police and let them work for you. Let me get that gendarme—"

"No, Anthony. For heaven's sake, don't think of the police!"

"I won't, then. But let me go ahead with the thing for you, please."

"Alone? No, not alone." She added, in a murmur, "They've killed him!"

"Did you know him?" asked Hamilton.

"Just a little," she said. "He was a man," she added, "who should have been rich and one who should have lived like a king with thousand's of people to serve him. And instead, they've murdered him—"

"Look, Mary, I don't understand. But aren't you afraid that they may serve your friend Petrolich out of the same dish?"

"They may. Perhaps they have already!"

"Well, I'll stop trying to think. You do my thinking for me, Mary, and then tell me what to try for you. Is that a go?"

She shook his hand.

"Your heart is as steady as a metronome. If you had lived in a time of war, what a hero you would have been, Anthony!"

"No wars, I hope," he answered. "Too much mud, Mary. And I hate canned food, don't you? You know that song:

"Julia, isn't it rather thin

To seal yourself like beef in a tin?

Julia, Julia, please be nice:

Flowers aren't preserved in ice."

"Can you sing even now?" she murmured.

They reached the hotel and he took her up to her room. She had recovered her liveliness of manner by a sudden effort, but she was already drooping when she passed through her door. She clung to the knob as she tried to smile back at him.

"You were wonderful, Anthony," she said "I never saw such good driving. I never saw anyone so perfectly without fear of anything!"

BACK in his room, he rang his headquarters. "Hello!" called

the voice of Louise Curran. "This is 1815," said he. "As if I

couldn't spot your Voice!" she said.

"Is anyone there?"

"Slocum has just come in."

"Tell him to watch the telephone and take messages. I need you."

"That's good news," Louise said.

"There's a vacancy among the chambermaids at the Crillon. Or a vacancy is going to be arranged. Get yourself up in the right sort of clothes. Come over here. Ask for Monsieur Giverny. Tell him that you're applying from an agency. He won't ask you what agency. He'll put you on the job and assign you to the floor where you'll find the rooms of Mary Michelson. After that, you turn into a shadow."

"To watch her?"

"Yes, and everybody who comes near her. Disguises are thin stuff when a man is working against the eyes of the Gay Pay Oo, but I've an idea that de Graulchier will put on a new face and call on Mary before long. You be on hand to report."

ROOMS and furnishings didn't usually make a great deal of difference to Stenka Koledinski. But he disliked this room for two reasons. First because it gave on a court so narrow that the adjoining wall was not ten feet away; and second because a distinct and stale odor of perfume hung in the air. Every sign indicated that this room had once been occupied by a woman.

The little Russian who was interviewing Koledinski had reclaimed for himself, so far, only a table in a corner, on which there were cigarettes, some writing paper, a heavy fountain pen, and some books. He clasped his thin, dry hands together and smiled above them at Koledinski.

Koledinski disliked that smile. War never had frightened him so much, because he knew that opposite him sat Dmitri Berezov, who was, almost beyond a doubt, the keenest intelligence in the Gay Pay Oo. He possessed the impulses of a hungry wolf and the manners of a hunting cat. Men on whom Berezov smiled were usually very close to death, no matter how well they were feeling at the moment.

"Speaking of those old days, Stenka Koledinski," Dmitri Berezov was saying. "You were with the Romanoff family just before they were executed at Ekaterinburg?"

"I was with them until just before. That was the pity," said Koledinski. It was hard to face the eyes and the smile of Berezov, but Koledinski had faced cannon.

"Pity?" echoed Berezov.

"I played my part too well," said Koledinski. "The Romanoffs believed in me. The trouble was that other people believed in me, also."

He lighted a cigarette.

"What did the people think?" asked Berezov.

"That I was the good, faithful slave, the dog that served the Romanoffs. A true Cossack of the old sort."

"And yet you were not?"

"Not? Why, I had waited for thirty years to find my day!"

"What day, Stenka Koledinski?"

Koledinski wrenched the collar of his shirt open.

"You see," he asked.

Berezov leaned and looked closely at a series of white marks, some of them very ragged, along the base of the Cossack's neck.

"Those are old scars," said Berezov.

"I was eight years old," said the hetman. "And I was playing by myself with my pony; and the Prince Alexis and his sons came by, with their wolfhounds."

"Alexis was a Romanoff."

"They had found no wolves. So they started to chase me. My pony ran like a devil. I was frightened. My legs were short. At the first jump I sailed off into the air. Prince Alexis and his boys were laughing too much to call off the dogs right away. One of them got me by the throat."

"And you were eight years old?"

"Yes, but I always carried a knife and I ripped up the belly of the hound."

"Ah!" said Berezov.

"It was a valuable dog. The prince screamed when he saw the beast run in a circle with its entrails falling out. His boys held me, each by an arm. They beat me with their whips. And the blood was running down from my torn throat."

"Ah, good!" said Berezov. "So you had a chance to think, while they held you?"

"I had time enough to think. Enough thoughts to fill a long life. Afterwards I waited. Alexis died. The war stole his two sons from me. There was nothing left for me but the Little Father!"

He paused, and then added, "Afterwards I made them love me. There was no one like that faithful old fool, that Stenka Koledinski. But I did a little too much. I was not trusted to be near at Ekaterinburg. That was how I overplayed my part."

He was buttoning up his shirt again at the throat.

"Why did you never tell that story before?" asked Berezov.

"After I grew older, I was ashamed to tell it. Men would say, 'And you let the three of them live?' Because of the shame I never spoke."

"And now?"

"If there is a Romanoff that should be worried by the throat, or to have his tongue torn out so that he can only bubble blood—like a good friend of mine as I once saw him—"

"Stenka Koledinski, what a pity that we have not known you better, and for a long time!" Berezov murmured.

"Well, I shall not mind the waiting, if there is a chance to do what I wish to do."

"Perhaps you may have your chance before the day ends," said Berezov. "Georg!" he called.

Here a fat, comfortable-looking blond fellow appeared.

"Talk to our friend Stenka Koledinski," said Berezov, and left the room. At the door across the hall he rapped in a certain odd rhythm.

"Who is there?" asked a voice inside.

"Berezov," said he.

The door opened, but the man behind it held a sub-machine gun under his arm. "All right," he said, and stepped aside.

ON the bed at the farther end lay a tall man with a face that

looked green-gray under the electric light, which hung by a cord

from the center of the ceiling. It was a bare, horrible room with

two iron beds. The white paint had turned gray or was chipped

down to the black of the metal. Pictures of lechery on the walls

mocked this squalor. Berezov kicked the rumpled and worn rug from

his way as he crossed the room. The man on the bed had his hands

folded across his breast and a pair of bright little steel

manacles held the wrists together. He opened his eyes and looked

up without interest at Berezov.

"Sit up," commanded the agent. "Sit up, Ivan Petrolich."

The tall figure raised, hunching with a painful effort.

"Do you hear me?" said Berezov. "I have finished arguing. You will give me your final answer now. Do you return of your own free will to Russia with us, to live there by choice the life of a simple villager, admitting the beauty and the glory of the Soviet; ideal, or do you die here and now?"

The head of Petrolich rolled back on his shoulders. He looked not at Berezov, but above him, at the glare of the light.

"I die here and now," he said.

"Swine!" said Berezov. He raised his hand, resisted the temptation, and then struck. Petrolich, with perfect indifference, watched the blow coming. The flat of his hand spatted against his cheek and knocked his head against his shoulder, tipped his whole body aslant.

Then Berezov went to Koledinski.

"There was a hope that the man could be frightened into accepting the life of a peasant in the country his father ruled," he said. "What a tribute that would have been in the eyes of the country, in the eyes of the entire world, to the truth and power of the Soviet plan! That hope is gone. Stenka Koledinski, perhaps you are to be luckier than you think. You may be the executioner of the last of the Romanoffs. Their dogs pulled you down; now you may pull down the last of their blood. Come!"

He took Koledinski across the hall, saying briefly to the guard:

"You may go, now. This man will take your place. You, Petrolich—here is the Cossack who fought for your damned father. This is Koledinski, the hetman, who will show you how well he can guard you! Koledinski, I leave you in charge."

He went from the room, and Koledinski went slowly towards the slender, awkward figure which sat on the edge of the bed. Ivan Petrolich stood up.

"I am ready!" he said. But Koledinski sank to his knees, saying:

"Little Father, I come to die with you or save you."

"You cannot save me, Stenka," said the Czarevitch. "You are a kind fellow and very brave, but you cannot save me. Stand up, my friend."

The Cossack rose.

"I thought they had sent me an executioner, and they have sent me a friend. Stenka, I know that you are a frightful danger here. There is nothing you can do for me, and therefore you must slip away. Listen to me—I am no longer afraid. For sixteen years I have been breathing the taint of death. I am already nearly dead; half a step and I complete the journey. Believe what I say. I am not hungry for life. I don't like the taste of it. Now go quickly, Stenka, before they have learned to suspect you."

"It is the first command you have given me," the Cossack answered. "God witness that it is the only one I shall disobey."

"You can see," said Ivan Petrolich, "that there, is no way of escaping. The windows open on nothing. . The courtyard below is watched day and night. There is no way of leaving this room except through the door, and who could pass through the guards who are placed below."

"It would be very hard," agreed Koledinski.

"It is the headquarters of the Gay Pay Oo in France. A dancing, singing, drinking place! Who would imagine that such cruel people could be so very clever and gay, Stenka? But unless you escape at once, you will be lost, my dear friend."

"Look at me!" said Koledinski, suddenly. "Do you see what happiness is in me?"

"Ah?" said Ivan Petrolich. "Yes, I see it. And now I understand. It makes me proud."

He began to smile, then he added:

"My father had all the Russias. Well, I am no less an emperor. I have Koledinski!"

The hetman began to tremble.

"You have more than me. You have faith, Little Father!" he said.

"Have I faith? Yes—that it will all end."

"There is God who watches you," said Koledinski. "You will be saved!"

"Do you believe it? Then I shall believe it also," said Ivan Petrolich.

He glanced away from the hetman. The wind now leaped out of the distance with a howl and began to shake the entire building in which "Le Moskovite" was lodged.

AT the Hotel Crillon, there was a tap at the door of Hamilton's room. When he called out, a chambermaid appeared, in crisp white, with a supply of face towels draped over her arm. The fluff of cap on her hair blew in the sudden draught as she closed the door behind her. And Hamilton cried:

"Ah, Louise! You've brought news?"

He took the towels and laid them aside. "You always ought to be dressed like this," he said. "Except that it makes you too young to be true. How old are you, Louise?"

"I'm old enough to listen behind a closed door," Louise Curran said. "Particularly if there's a Mary Michelson and de Graulchier on the other side of it. Are you wild with happiness—after a whole day with Mary?"

"I've been treated like a whitling. We've seen Koledinski and trailed him; we've spotted Boris after we lost the Cossack; we found Boris stabbed to death in his taxicab."

She closed her eyes. "That's Gay Pay Oo," she said.

"Now we're waiting," he went on. "What did de Graulchier and Mary talk about?"

"Everything. I saw something, too. De Graulchier has turned himself into a gray-headed professional man of some sort. Lawyer, advocate, doctor, I don't know which. He's changed his voice, too, and his walk. He steps bigger on those short legs. His head is canted a little to the right. He has shoes that give him an extra inch or so of leg-stretch. He makes plenty of gestures, and uses a flashing smile through his mustaches."

"Is he very good?"

"Anthony, he's marvelous."

"He's a great agent," said Hamilton. "He's a very great secret service man. I'd rather have him on my side than any man in the world."

"You have him on your side—for today and tonight."

"We're fighting for the same thing, and I think we'll win," said Hamilton. "Somehow, between us, we'll get the Czarevitch away from the Gay Pay Oo. Afterwards will come the tug-of-war, to see which of us two walks off with the prize."

"Anthony, wouldn't it be better for you if the Gay Pay Oo actually murdered poor Ivan Petrolich?"

"Better for me as a counter-espionage agent; a lot worse for me as a human being."

"Do you try to mix both things into your work?"

"I have to."

"That's why you're killing yourself," said the girl.

"Tell me about de Graulchier's talk."

He walked about, pausing as she made important points.

"Mary made her report. I learned about Boris from her. De Graulchier cried out something about the Gay Pay Oo being ready for anything if they were willing to murder Boris. He said that if he could ever find such agents and such a spirit in them as the Gay Pay Oo found in its men, he'd be able to change the mind of the entire world in twenty-four hours. He said that the only man he'd ever had of that perfect type was Pierre, and that the Americans had killed that perfect man for him."

"Well, go on."

"Mary said that you had been as cool as steel—and as silly as an idiot all day long. She said that you flew an airplane and drove a car like a wizard; she told how steady you were about finding Boris."

"All right," murmured Hamilton.

"De Graulchier asked her if she thought you suspected anything. She said that she thought you had not. She said that you were blind with love, Anthony."

She made this bit of her report with a slight lift of her head, challenging him, but Hamilton gave no sign. "She's perfectly sure of you," added Louise Curran, to pour salt in the wound. "De Graulchier said that your character was clear to him. Your nerves were steel and your hand always steady simply because you never used your brain—you had no brain to use. Of course it's amazing that he could have missed you so completely. He was paying you the greatest compliment that you'll ever receive."

"What's next on the program?"

"De Graulchier is wild with anxiety. He's scattered his agents through Montmartre. Mary Michelson was almost crying when she talked about Ivan Petrolich. She declares that if anything happens to him it will be her fault, because it was she who persuaded him to try to win back Russia as Czar, after de Graulchier had located him. She's willing to do anything in the world to undo that mischief."

"Is that all?"

"Yes. They're simply waiting."

"I'm doing the same thing," said Hamilton. "If de Graulchier has sent a number of his men into the district, I'll not be surprised if the Gay Pay Oo spots one or two of them. If that happens, we may find the Czarevitch, but we'll find him dead."

He threw himself down on a couch and stared at the ceiling.

"De Graulchier ought not to use numbers. There's bad tactics in that. The Russians have eyes and they can—"

HERE the telephone rang. Over the wire came the familiar voice

of Harrison Victor. "We've spotted Dmitri Berezov entering 'Le

Moskovite'," he said.

"Thank God!" cried Hamilton. "It means that we've located the spot. Do you know anything more about the place?"

"A good deal. The lower part, the big cellar room and all that, are for the drinking and dancing. But upstairs are some rooms let out to lodgers. The rooms seem to be full most of the time. I sent around two men, but they couldn't manage to get in. No vacancies. No vacancies in prospect. The idea is this: it is a Russian hangout where the emigres collect. You understand? Gay Pay Oo men, nearly all of them."

"I understand," agreed Hamilton. "The Russians always believe in numbers."

"What shall I do?"

"I don't know. Keep at hand, but don't show yourself too much. What one of our men are the Gay Pay Oo least likely to have seen?"

"Slocum, I suppose."

"He speaks perfect French, doesn't he?"

"Yes. Plus Paris slang."

"Have Slocum change and dress in his best dinner jacket. Louise Curran will show up in a short time. Slocum will take her down to 'Le Moskovite.' The Russians have never seen Louise, except for a flash."

"Is that all?"

"Keep in touch with headquarters. I may leave messages for you there. I'm going to try to get down to 'Le Moskovite' myself tonight. Good-by."

He rang off.

"I heard the orders," said the girl. "What's my part?"

"You won't have to make up. Be the wide-eyed little American girl who is seeing the deeps of Parisian night life, a good deal shocked by it all, and almost afraid of the big Frenchman who's taking you around. But whatever you do, keep out of sight. Don't let Mary Michelson see you. Because she remembers people pretty exactly, I'm afraid."

"I won't let her see me. I'm going, now. But tell me one thing: does the old heart still ache a good deal?"

"So-so," said he.

"Do you know that she's already half in love with you? Do you know that if you showed yourself as you really are she'd be mad about you, Anthony?"

"What a silly girl she'd be, then," said Hamilton.

"Well," said Louise, slowly, "I hope that the Gay Pay Oo get her. Listen to me, Anthony. She's not a right sort. She's the bait they held in front of Ivan Petrolich to make him come out of retirement and fight for his father's throne. She's tried—"

"It's no good talking to me," said Hamilton.

"Do you mean that she's right when she laughs and tells de Graulchier that you're blind with love of her?"

"Yes," said Hamilton. "She's right. So blind that nobody but Mary can open my eyes."

Louise Curran went out of the room without a word. She seemed in a fury. Not a moment later, Mary Michelson had him on the wire.

"Anthony, I'm going back to Montmartre this night," she said.

"Oh, hold on!" he called, "What part of the mountain?"

"Where Koledinski disappeared."

"You can't go, Mary. There's a lot of red-handed trouble down there, I'm afraid. You know. The sort of game where a fellow that's tagged stays 'it' forever. You didn't see that fellow in the cab. I did."

"I have to go down there. Anthony, will you take me?" she answered.

IT was bitterly cold. The wind came with a screaming edge and cut deep. The snow flurries flew as high as the housetops.

"Which one?" asked Mary Michelson, waving towards the many electric names.

"Why not that one? It looks warmer than the rest," said Hamilton. "'Le Moskovite.' Why not that one?"

"It's as good as any, I suppose," she murmured. She ducked her head against the wind, and they ran in a swift stagger across the street. Steps led them down well underground to a dingy window where Hamilton bought two entrance tickets. A hollow-checked fellow with his chin lost in a muffler looked them over with the truly shameless eye of the French, and then they went into the main room.

It was amazingly large, with tables arranged closely around a dance floor and little curtained recesses giving back at the sides. They were led to a place luckily vacant in a corner. On the way to it, half the audience began to shout:

"Guillaume and Nicolette! Guillaume and Nicolette!"

Up on the stage at the end of the room a dancer vainly attempted for a moment to continue his routine, but the orchestra was drowned by the uproar. The dancer faltered, stopped, fled from the stage. A yell of triumph rang through the room. Men stamped and shouted with a vicious pleasure.

It was in the midst of this tumult that Hamilton, as he led Mary to their table, felt her start suddenly. He was able to catch only the direction of her glance, but it showed him the unmistakable narrow back of Berezov, moving away through the crowd.

"Do you know what I've done?" she said as they came to their table. "I've forgotten my compact! How could I be so perfectly silly? Will you find a telephone for me? I can talk to the maid on my floor and have her send what I need in a taxi."

Of course it would be Berezov's name that she would send over the wire to de Graulchier. Hamilton took her at once to the telephone and, from a distance, listened to the obscure sweetness of her voice. She came back to him, smiling. Her perfect ease and poise sickened his heart. She would, he felt, be able to face any situation, accomplish any treachery, and smile through it.

Well, the clans had gathered, now. The best brains in the espionage services of Russia, Japan and America were assembling in and around "Le Moskovite."

When the girl had slipped off her fur cloak he could not help exclaiming:

"Why, you're real Paris, Mary! Absolutely real Paris! Nobody but a French girl would have worn a high-necked dress like that. And only the French know how to make up the eyes that way. How did you manage it so easily and quickly? And out of the one case you brought from Monte Carlo? And that little soft silk hat on your head—and by Jove, Mary your evening bag is made of exactly the same stuff, isn't it?"

She listened to the babble of his admiration with rather far- distant eyes. But in fact he felt that the turnout was perfect for such an evening. French women are apt to appear publicly in black, and therefore the color note was right. There was some brightness, too. A big square-headed emerald in the pin at the side of her collar, and the twin brother of that jewel in the single ring she wore— why, the value of those two gems might make anyone's evening in Montmartre a little dangerous.

She had made herself at home. She was no more like the girl he had known in Monte Carlo than night is like day. She seemed a lady, but a lady of Paris; the sort of flower that blooms by night. The men stared at her beauty with small, evil eyes.

His heart sickened a little. If this were acting, it was too well done to suit him.

They had a bottle of dry champagne. She used the little wooden spoon to stir the bubbles out of hers, while he told her that it was a sacrilege.

They danced. The modesty of high neck and hat and long sleeves were quite outbalanced by the extremely French subtlety and close molding of the dress.

She was perfect on the floor, he thought, because she kept that balance which enabled h e r to move without weight or effort at his will.

Something rustled. Not with his eye, but with an extra sense he knew that she had gathered into her hand, as they walked through the dancers, a little wisp of paper. Already de Graulchier was in communication with her. Very quick work indeed, thought Hamilton.

They went back to their table.

Things would begin to happen, now, and very rapidly. How much information would be given to him?

A pair of singers appeared on the stage, but they had hardly commenced their song when babel rose once more, and the cry:

"Guillaume and Nicolette! Guillaume and Nicolette!"

The shouting swept the unlucky two from the stage. A big, fat man ran out from the wings and raised his arms for silence.

He got it, and a few groaning curses as well.

"My dear friends, permit me," he said. "You ask for Guillaume and Nicolette. I am desolate that I cannot offer them to you. It is a grief to me that of their own will they left me, though I implored—"

"Liar!" shouted a voice from a corner.

"Liar! Liar! Liar!" shouted a great part of the audience.

Of course there were people of most sorts in the cabaret, from the top almost to the bottom, but even the gentry, in France, give way to their enthusiasms. A good many of them were giving way now, shouting, "Liar!" at the proprietor of the place.

He stood before them calling down the witness of the gods with both hands and inviting with his gestures a heavenly inspection of the truth that was in his heart. But the crowd roared him down. He fled in an agony from the stage. A derisive applause followed his exit.

Hamilton asked the waiter the reason for the excitement.

"In this Monsieur Raoul was a fool," said the waiter, with the Gallic candor which the world cannot match. "Guillaume and Nicolette were dancers who cost him very little; but he thought that he could get them still more cheaply. She was pretty—with the footlights in front of her face. She had quite good legs, except for the knees.

"But you know how it is> monsieur, French girls are not blessed in the matter of legs. In other ways, yes. In other ways, yes, indeed! But in legs, no. The knees will not be right. It is a pity, but it is true. Why should sensible men close their eyes to the truth? And now Monsieur Raoul, in other things intelligent, has sent away Guillaume and Nicolette. Guillaume had a light manner. His feet were like a whirl of feathers when you blow at a torn pillow. Besides, he could sing American songs, and you know that they are popular."

"Hello! American songs?"

"It is truth, monsieur. Not in all places, but at 'Le Moskovite,' yes; the American songs are popular. Now Monsieur Raoul offends his patrons every time he offers them another bit of entertainment. He loses trade. Soon there may be a riot. He sees money dripping away. He has begged Guillaume and Nicolette to return to him. But they have found another place—far away, in Bordeaux. About these things I have informed myself, because I happen to be the brother of Nicolette."

More dance music.

"Will you dance, Mary?"

She had; read her note, he had observed, while the waiter was talking.

Now she sipped her, champagne, and shook, her head;

"Do you mind sitting?" she asked.

"Mind it? No, love it," said he.

He noted that when she smiled at him, he could not help; having faith in her smile. It was true that he was blind. Doubt could not live in him when she was near.

A fellow with a lumbering step and a girl in a flash of pink satin came in and found a place in one of the curtained recesses. Hamilton decided that Louise Curran had rather overdone the girlishness he had asked for by that pink dress, with her gold slippers and her hair braided in a coronet. The curtains of the recess were drawn wide, so that from Hamilton's table the swarthy face and heavy profile of Slocum were visible. But Louise was out of sight. That was the right sort of planning. A good fighting, sort of a man was Slocum, and this was the night and the place where he might be more useful than his weight in gold.

"Stand up—get in front of me— pretend to be pulling my cloak about my shoulders," Mary said. "That's it, Anthony—stay right there in front of me—all right, now."

He sat down as she said:

"That was one of them, Anthony."

"But one of what?" he asked.

"The Gay Pay Oo."

"The jolly old Russian murderers?" he asked.

"Hush. Don't whisper it, even. They may be all about us. The men at the next table—or the women—the waiters—anyone or everyone! Anthony, listen to me!"

He leaned across the table a little.

"I love you, Mary!"

"Poor Ivan Petrolich I've just had word that he's in this place, almost certainly. You're not listening!"

"Mary, I can't listen. You're so beautiful that there's a hole knocked in my old brain. When you picked me out to be of use—you thought that I might be quick on my feet, or something—but tell me, didn't you care a small spot about me, also?"

A woman's voice began to rise in shrill, unmusical laughter that wavered up and down the scale.

"I couldn't have asked you to come if I hadn't cared a great deal for you," said the girl. "I couldn't have asked any one to go into such a danger unless he had been very close to me. Does that sound frightfully selfish and strange?"

"Wait a minute," answered Hamilton. He tossed back his head so that the light would flash on his monocle. He could not help telling her that he loved her; but he dared not show her his real self. He had to remain the perfect ass throughout. "Now have I got it, Mary? A thing we like a lot —we have a right to chuck it in the fire?"

"Not truly a right. But—I can't let myself think about it. I have to ask you to listen to me, Anthony."

"I shall," he said. "It's just a kind of a craziness to sit here across the table from you; and some of the craziness bubbles up—bubbles into my throat and I can't talk, into my eyes and I can't see a blinking thing, Mary. But I'm better, now. I can listen, all right."

Even after he had assured her of that, she kept watching him for a moment, seriously, so seriously that the make-up seemed to be rubbed from her face. He could see the truth of her. A great soul was behind her eyes.

"Ivan Petrolich is surely here," she said. "There are others on the lookout for—well, for any of Ivan's friends. If they see me—steadily, I mean, and enough to recognize the girl who runs the villa of Mon Sourir—why, Anthony, they're such people that they would do to me—and you—just what they did to that other man, tonight. I've—well, I've seen another friend in this place. He'll sit with me here. Anthony, I want you to go home."

HE could feel his face turn cold and his shoulders stiffen

against the back of his chair. "If you wish me to, certainly," he

said.

"I wish you would go," she answered, but she looked suddenly down at his glass of champagne.

"Is it because the other fellow would do better?" he asked. "Or you think that I'll let you walk out sort of onto the edge of things?"

He found her scaring suddenly at him.

"You can be serious," she said. "With all your heart and soul! Well —I'd rather be with you through what's to come than with any other person in the world. But if anything happens to you—"

"Hush," said Hamilton. "I don't think we need to talk any more about it, do we?"

"No," he heard her breathe. "Not when you're this way. No—we understand without having to talk."

IT was in the moment when Hamilton was feeling that he might have made incalculable progress in the esteem of Mary Michelson, and also that he might have opened her eyes, fatally, to an appreciation of his true quality, that a voice groaned loudly from the dance floor. Two or three women screamed out in fear or cried in disgust, and then there was the sound of a heavy fall.

The crowd of dancers separated. Hamilton saw a tall, thin fellow stretched on his back in the middle of the empty space. In spite of his slenderness, he had quite a paunch, for time and good living had managed to create a beard on his chin and a swelling about his midriff. A pair of bouncers strode immediately for the spot, but Monsieur Raoul was already bending over the fallen man. Next his panic-stricken voice was calling for a doctor.

At once there arose and strode across the floor a man that Hamilton had not noticed before. He had a brisk walk, with something odd in the way his heels hit the floor. His head and shoulders were a shade too big for the rest of him, and the long tails of his coat exaggerated this aspect. He wore a bristling pair of mustaches and a stiff little beard to match.

It was the description given by Louise Curran that enabled Hamilton to recognize de Graulchier. And his heart suddenly went out to the courage and the brains of the Number One agent of Japan. It was as though a king had ventured into the heart of the enemy's camp. That was what de Graulchier was to the Gay Pay Oo. The king of all their dangers. If they could snuff him out, they had obliterated the greater part of their troubles. How great a part, perhaps even they did not realize. It would be a simple thing to betray de Graulchier to them now. But Hamilton could not do it. He wanted the liberty of poor Ivan Petrolich. He wanted, above all, to give de Graulchier a fighting chance worthy of his valor.

He watched the Japanese-Frenchman kneel by the limp body. He saw de Graulchier make reassuring signs, suddenly jump up and call in a loud voice:

"Don't disturb yourselves, gentlemen, ladies! A simple affair. Very simple. Too much brandy, perhaps."

A moment later, de Graulchier was giving orders to the waiters who picked up the fallen man and carried him from the floor. It was noticeable that no female partner of the sick man appeared. Perhaps she was already scurrying out of the place and hunting for a refuge.

For this was no "very simple affair." The very fact that de Graulchier had been on hand so suddenly proved that he must have had something to do with the fall of the man who had been overcome. De Graulchier was at work. There was this to be observed: that de Graulchier would now, for some time, be behind the scenes of "Le Moskovite," working over the body of the victim. If he had poisoned the man, of course he would know the proper antidotes. Already, by his little speech of assurance to the audience, he had stopped a sudden exodus from the place; and that would put him in a good accord with Monsieur Raoul.

The customers of "Le Moskovite," in fact, soon checked their first impulse. There was a bit of high pitched gabbling. Then people resumed their seats. Instead of freezing conversation, the audience began to look and smile at neighbors. Everyone seemed to feel more chummy and at ease because, perhaps, a man had just fallen dead, or dying, in the cabaret.

The orchestra struck up a lively jazz tune.

"Rum lot of beggars," said Hamilton. "They rather like this sort of thing."

"Animals!" said Mary Michelson, in appropriate French.

Here a heavily built man who reminded Hamilton more than vaguely of Hans Friedberg from Mon Sourir, went by the table and quite openly dropped on it a little pill of paper. Mary Michelson unraveled the thing at once. She leaned to read aloud to Hamilton:

Make a disturbance. Anything that will give me ten or fifteen minutes of uninterrupted quiet back of the stage. All goes well but I need your help!

"Who needs it?" asked Hamilton, naturally enough.

But he recognized de Graulchier in that note. A disturbance had to be made that would occupy all eyes and ears while de Graulchier carried on his plans. What plans could they be?

"I could start a fight with somebody," said Hamilton, hopefully.

She was not shocked. She simply measured and weighed him with a glance.

"They have men here who understand how to take care of such interruptions," she said. "You couldn't make a ten or fifteen minute disturbance, Anthony."

THAT was all. No care for the security of his skin. He began to recover rapidly from the rosy haze into which he had passed the few moments before. If this were romantic love, it bore a strange face indeed.

"What else could we do? You want to make the disturbance, Mary?"

"Oh, of course."

"Your friend, whoever he is, couldn't be wrong?"

"Wrong? He's never wrong!"

Hamilton thought of de Graulchier, and could have nodded agreement. That fellow would seldom be in error. And, at the same time, his respect for Mary Michelson rose. She could be trusted to make enough of a disturbance to occupy a tough Parisian cabaret for a quarter of an hour. How?

She was beckoning to Monsieur Raoul, who was walking through his hall placating his guests, smiling and beaming from side to side. The fat man came at once.

"Monsieur Raoul," said the girl, "my friend is a very famous dancer and singer. I dance and sing a little, also. Shall we go on the stage and try to amuse the people?"

Monsieur Raoul stared; it seemed that the green light of the two emeralds alone filled his eyes.

"Madame— pardon, mademoiselle—if you take pity on me—your beauty on my stage, mademoiselle—the undoubted talents of monsieur—come in the name of heaven—there is no other entertainment—nothing but fools falling dead—or almost dead—

"Go back stage," said the girl. "Tell the orchestra that something is going to happen. We will be there immediately."

"God bless you!" groaned Monsieur Raoul, watching with an eye of agony a pair of obviously rich and obviously American people about to walk from his place. He rushed away.

"Mary, what have you been saying?" murmured Hamilton.

"Do you remember?" asked the girl. "Once you said that we might be able to try a turn on the stage? Well, there's the stage, Anthony! Will you try with me?"

"Mary, if I have any brains at all, they are in my feet. What can you do?"

"I can sing a bit," she answered.

"Anything new?"

"Everything new!" she said.

"My howling word!" said Hamilton. "Shall we go?"

They found their way out through the side door. They were in the desired place, the interior of "Le Moskovite," where perhaps the Czarevitch of all the Russias was held by the secret police of his country. Where both de Graulchier and Hamilton sought the solution of their problem—in opposite ways.

A back stairway climbed in a dingy arc. The inevitable draught and chill of the back stage whistled in the air. From the wings, the sweating face of Monsieur Raoul turned to the girl.

"Mademoiselle, if you can see with your own eyes—the rich man, the great man from Pittsburgh who owns all the steel in the world—he has honored me by coming and now he leaves— in the name of God, dear mademoiselle, do something! Let them see your face and the green of your emeralds—"

"What can you do?" she asked Hamilton quietly.

"Anything you say," he answered.

"'In a Ship on the Way to Paris,'" she suggested. "You are what? I sing off stage, and you are what?"

"Seasick on the stage," he answered at once.

"Give them that," she replied.

He stood straight, trying to think what his feet would have to do. Monsieur Raoul was groaning to a lad at his side, a boy in a brilliant uniform: "Tell Pierre—quickly, quickly—that we must have, 'A Ship on the Way to Paris.' First a roll of the drums, very loud. Then a shout from all the orchestra—and then the tune."

The vamp came before Hamilton had finished thinking out his steps. He had used dancing to fill out his role of the fool. He would have to use it in earnest, now.

"Mademoiselle, mademoiselle!" moaned Monsieur Raoul.

"Now do something! They are waiting!"

And out of the throat of the girl suddenly streamed a light voice, exquisitely pure and clear, which seemed to fight against and spread through the noise in the outer room, carrying those harum-scarum words:

"When you and I were on the sea

And hand in hand with liberty,

When you were making me at home

How far was home away from

me?"

SOMEWHERE behind Hamilton, off the stage, he heard a voice say, "The doctor is calling an ambulance to take away—"

To take away that fellow who had fallen on the dance floor? Well, perhaps; but also there would be in the ambulance one Ivan Petrolich, who by some scores of millions was considered the true ruler of Russia. The beauty, the daring of the scheme of de Graulchier filled the mind of Hamilton.

Then he was out on the stage, dancing, with his collar turned up and his opera hat on the back of his head. He seemed to be proceeding straight across the stage; but his progress was slow, although his feet were working hard. As though he were caught by a rising incline which he had to climb, he sometimes leaned forward, and again he was staggering with his body bent back until it seemed as though the stage were the heeling, swaying deck of a liner.

The crowd was not appeased. It began yelling in fury:

"Guillaume and Nicolette! Guillaume and Nicolette!"

But the feet of Hamilton were beating out, as he danced, the code for "L.C." over and over again.

Louise Curran was back in the audience. If only she could hear the sound through the tumult!

And then Hamilton saw her, a flash of radiant pink at the entrance to the recess; the big, dark form of Slocum behind her. She was applauding vigorously, her hands well-raised. She even waved applause — and in the movement of her arm he read that she had heard his call!

It was much easier for everyone in the place to hear, by this time, for though there were still a number of rebellious ones who bawled out for "Guillaume and Nicolette," those in front were beginning to turn and glower at those in the rear who still rebelled.

As far as the sweet influence of the voice of Mary Michelson extended, the silence reached, and increased, until suddenly the rebels saw that the big majority of the audience was against them. After that, instantly, the cabaret was perfectly still and absolutely orderly.

A little whisper went up; Hamilton knew that Mary had appeared at last from the wings. At his next gyration he could see her standing there, singing with few gestures, smiling only barely enough, rushing not a step or a whirl closer to her audience, but commanding its approval very haughtily.

Such an air is not to be seen in Montmartre, and the crowd was enchanted. They could hear better voices, but they could not find such a manner, or a Mary Michelson smiling as she confided to her audience the follies of those silly songs.

They gave her a roar of applause as she came to the chorus. Hamilton sang it through with her. They wanted the second verse, too, and roared and thundered for it when the pair of them slipped off the stage.

Monsieur Raoul, in the wings, had tears of joy in his eyes. He hovered about them. He peered out, exulting in the expectant enthusiasm of his clients. "It is to me a year of happiness, a year of happy life!" he cried.

They went out to do the second stanza. Hamilton's dancing feet rapped a message in plain Morse code. There was no other way. He could not leave Mary Michelson while all of this was going on. So he spelled out the words:

Watch for arriving ambulance and inform me when it comes.

He had to repeat the sentence three times before he got the "received" signal from Louise Curran. At once she disappeared, and Slocum with her.

In the meantime, the attention of everyone was being held to the perfect satisfaction of even a de Graulchier. The ticket men from the front of the place were now leaning at the door to watch and to listen; the mechanics, the very waiters were agape, drinking in the delight of all Parisians—a new sensation. A fat man with a greasy face appeared in a distance. Hamilton was satisfied.

If even the cook appeared, it meant that the mind of "Le Moskovite" was occupied thoroughly.

He was ready to leave—but there was little prospect of the crowd giving them up.

Hamilton was panting from the work of the dance as he stood with the girl in the wings.

"'Nancy.' Do you know 'Nancy'?" she asked.

"I know it, but it hasn't the spice they want out there," said Hamilton. "Mary, we're going to do this stuff on the Big Time, one of these days. You're wonderful. Give them something better than 'Nancy', though."

"I think they'll like it," said the girl.

Monsieur Raoul was entreating with extended hands, with sagging knees. "They will go mad if you leave them after one song!" he declared.

"Play 'Nancy,'" said the girl.

And a moment later the silly strains of the song were in the air.

"You sing it and I dance it," she ordered, firmly, so Hamilton went out on the stage and sang:

"Nancy has eyes that can't go right;

Nancy has feet that can't go wrong.

They climb the ladder of the song

And then run into your heart so light.

But if you seven times denied her,

Like Robert Bruce she learned from the spider.

He could see Mary Michelson dancing, quite slowly, around him;

they did the chorus dancing together and she came into his arms

just before the last note.

There was pandemonium all through the house; and as they went out to take their bow, in the back of the big room Hamilton saw tall Slocum applauding with all his might—and slapping out the signal repeatedly, "Arrived!"

THE ambulance had come. And, upstairs, leaning over the

drugged victim, what was excellent Doctor de Graulchier

contriving? It was time to be gone, but how could he leave Mary

Michelson abruptly? She was holding him there, now, while de

Graulchier completed his part of the strange division of work.

She was a perfect agent.

"Is it fun, Anthony?" laughed the girl.

"How did you learn all those little drifting steps?" he asked her.

She kept on laughing. "Oh, I've had one of those all-around educations," she said.

The uproar in the audience was filling the house; they had to go out a third time before a crowd which now had enthroned them as favorites, so that they could not do wrong.

They sang that prime bit of idiocy:

"He's always the same and he couldn't be samer;

He's not a lion, but then I'm no tamer..."

They were almost at the end when Hamilton heard a sound both

short and muffled, like the slamming of a door. And yet there was

a difference which his expert ear detected—a little

unexpected depth and resonance to the noise. And he knew that a

gun had been fired, somewhere, in a closed room.

The song and dance ended. The applause roared and re-echoed through the cabaret. Hamilton, looking carefully into the wings, made sure that no one else seemed to have detected what his ear had caught.

Monsieur Raoul was pressing them to sing again. One more song... another dance...

"Monsieur," said the girl, "we sang to please your people, not to become professionals. Forgive us if we stop now?"

Monsieur Raoul was overwhelmed. If they would come again, if they would come regularly, he would put their names outside his place in the largest electric lights he could find—

She murmured to Hamilton:

"Will you do a great thing for me, Anthony?"

"Anything in the world that I can do," said he.

"Leave me, take a taxi, go straight back to the Crillon. Will you do that, please?"

"And leave you here alone?" he exclaimed.

Her anxious glance went past him into the shadows of the wings. He knew what was in her mind.

"I won't be alone," she answered. "I know ways of taking care of myself. And besides, Anthony, I've told you already that I've seen an old friend here. Will you go? Quickly? And forgive me? I'll try to explain another time—"

He could not rush his departure, but he was himself on tiptoe with eagerness to be off. "Later tonight? Tomorrow, Mary?" he pleaded.

"Yes—yes! I'll ring your room, Anthony!"

He left her, and as he went he could hear the loud voice of Monsieur Raoul shouting against the protests of the crowd, who wanted more of the two new singers.

THERE had remained with "Doctor" de Graulchier a chambermaid and a porter of the cabaret whom he would as soon have done without. Particularly after he telephoned for the ambulance, and returning, found the drugged man on the verge of regaining his senses. De Graulchier had been in touch with Friedberg and he knew that the German would appear with an ambulance perfect in outward appointments, manned besides with agents who could be trusted to the finish.

But the poor drugged fellow who was stretched on the bed was now beginning to part his lips and groan.

"Now he'll soon be well," said the maid. "As soon as a man begins to groan it is a sign; as soon as he swears, he's certain to be on his feet in another moment."

"We'll have him perfectly fit in a moment," said de Graulchier. Taking a little phial from his pocket he poured on the hemmed edge of a handkerchief a few drops of a colorless, almost odorless liquid. As soon as he had pressed the wet cloth under the nostrils of the senseless man, the fellow took a breath, an audibly deeper one, and then became perfectly quiet.

"You've given him the wrong thing!" cried the maid.

"Don't be a fool," the porter corrected her. "The doctor knows his own business. Yours is to hold your tongue."

"The slow way is the sure way," said de Graulchier. "The doctors who drag their patients out of bed today drop them into the grave tomorrow."

Here a steady vibration and a distant humming noise began. A door opened and let noise flood through the building; shut and closed the sound out once more.