RGL Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Edition, 2025

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

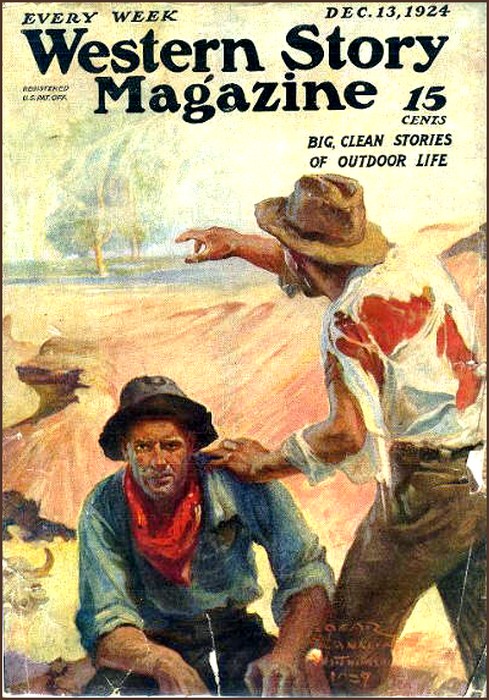

Western Story Magazine, 13 December 1924,

with "The Third Bullet"

IT was already the afterglow of the sunset time before Christopher Ballantine topped the hill that gave him a view of the house. He had no more than time to ride in, unsaddle, and wash, before supper would be on the table, but when he looked into the next hollow, in the muddy margin of the sun-shrunk "tank," he saw the head and horns of a badly bogged cow. This work should not have fallen to him. His brother, Will, back from college for the summer or for as great a part of it as he could endure, had been directed to ride the range near the house, and if he had acted according to his duty, he must have seen this bogged cow. But Will, as usual, had been playing truant.

A little flush of anger appeared in the face of Christopher. But it disappeared at once. He was too accustomed to doing his share of the work, and another share besides. He merely turned the head of his horse and rode down to the tank, making excuses for Will on the way. For, after all, when a boy comes back from college full of his athletic deeds on track and football field, full of tales of college eminence, clean-handed, high-headed, it is hard to put him on the range riding at the heels of stupid "doggies." No wonder that he had broken off work early.

Christopher Ballantine was used to making such excuses, both for his younger brother and his still younger sister. For, when his father died ten years before, Chris at the age of Sigh-teen had naturally stepped into the vacant place as the head of the family. Sylvia was only nine. Will was barely eleven. To those motherless and fatherless children, it seemed that the world owed special care to make up for their orphaned lives. And Chris Ballantine had taken that duty on himself, gladly, with a heart swelling with high determinations. He had put them both into schools. Now, with Sylvia at nineteen and Will at twenty-one, the elder brother could say with pride that they had been educated as well as any millionaire's children in the country.

If both of them had been pampered into pride and laziness, he dared not open his eyes to that fault, for the education of the two was the only result of the ten years of slavery which Chris Ballantine had just passed through. A series of disasters had swept over the ranch. At first they were caused by his inexperience, both in raising cattle and in marketing them. Afterward, when he learned the hard lessons which he needed to know, bad luck dogged him. Whatever he did went wrong. Three years before, blackleg had come like a curse on the place. The ranch had never recovered, and, left without a cent of incumbrance at the death of the father, the place was now heavily mortgaged. However, this was the price which had been paid for the education of the youngsters, and the elder brother felt more than repaid. It was therefore that he dared not open his eyes to their faults. For it simply meant opening his eyes to his own failure.

He rode down to the tank and set to work on the cow. First he unslipped his rope and shot the noose skillfully over the horns of the steer. But when the pony pulled the rope taut, it was plain that the steer was so deeply worked into the mud that its neck would break before it was drawn clear.

He had to ride right to the edge of the firm land. First he pulled at the horns of the bogged animal until its fore quarters were drawn up a little. Then he passed the tail over the pommel of the saddle and made the snorting cow pony heave up the hind quarters. When that was accomplished, he took another pull on the rope. This time the steer drew clear, slowly, with infinite tugging. For it let its exhausted body lie as a dead weight, hopeless, until it was in a half-leg depth of the mud. Then, discovering that it had a chance for life, it recovered its strength in a rush, plunged out of the tank, and made at Chris with lowered horns. There was barely enough agility left in the legs of the weary pony to avoid that rush.

And while the rescued steer galloped clumsily away, the rancher turned back toward the house, littered with mud, but profoundly thankful. So sadly had the herd diminished that the loss of a single steer was a heavy blow.

All of this made him late for supper, and when he had finished washing up and scraping mud, the cook met him with a significant shrug of the shoulders as he passed through the kitchen.

"They couldn't wait," said she, jerking a thumb over her shoulder toward the dining room.

Ballantine flushed again. It was very hard that they could not delay their supper half an hour on his account! He had to pause at the door of the dining room, for an instant, before he went in. But, when he appeared, he managed to be wearing a cheerful smile. They were down to coffee and cake. But as for an apology, it did not occur to them that one was needed. Sylvia merely nodded wearily toward him, and then looked at the mud stains with which he was covered.

"Well," said Will, "been day dreaming again? You're an hour late!"

He was too tired to be angry. His plate was brought in from the kitchen, covered with cold, soggy food. And he started eating with no appetite.

"There was a cow in the tank just over the hill," said Ballantine. "Me and the hoss had a tussle pullin' it out."

"You and the which?" asked Sylvia.

"Me and the hoss, of course."

"'Hoss?'" said Sylvia, arching her brows. "'Hoss?'"

"What's the matter?"

Will and Sylvia exchanged glances.

"It's no use," said Will. "The habits are fixed on him by this time."

"But good heavens, Christopher," said his sister, "I should think that you could make some effort."

"To do what?" asked Ballantine blankly.

"To talk as if the English language were something more than a cow-puncher's lingo, Christopher."

He stared at her for a moment. She looked very pretty with this flush of indignation in her cheeks, and with her eyes bright with anger and scorn. He felt a little stab of wonder then, as he had often felt it before, that this lovely-girl could actually be his sister. She was like dew touching his dusty life. And again he swallowed the faint beginnings of anger at her rebuke.

"Well, sis," he said, "maybe I don't talk the way Shakespeare, wrote. I ain't got the time to think about such things."

"Why?" she asked insistently.

"Why? Because it takes work to run a ranch like this, sis."

"Does it? Yes, I suppose so—to run such a ranch properly."

He winced again; then he looked straight down at his plate, hoping that they would not see his rising color. But, from the corner of his eye, he could make out the malicious little smile and nod with which Will egged on his sister to the work of torment. That, surely, was hardly fair.

"I ain't gunna pretend to be the best rancher in the world, Sylvia," he said at last, mildly.

She said: "I was talking to Mr. Bannock this afternoon."

"You was? What did old Si have to say?"

"Old Si," she snapped out, "is a very successful operator in cattle, I believe."

"He's a lucky dog," admitted Christopher Ballantine. "Lucky, lucky dog!"

He was thinking of all the calamities which had dropped upon the ranch and upon his life. He did not see the small, dark dining room, only half lighted by the flame which quivered in the throat of the smoky lamp. He did not see the very table itself, with its oilcloth covering, and the heavy, chipped crockery with which it was covered. He was watching the years, the dead years behind him. As for the future, it would all be like this—work, weariness, despair, until Will Ballantine, with his well-schooled brain, made some brilliant business stroke and was able to set him up on a larger scale.

"Lucky?" Sylvia was saying. "Lucky, Christopher? Then I suppose that you've been only—unlucky?"

He started out of his dream. "What's that, sis?" he asked hurriedly. "What's that?"

And he leaned anxiously toward her, his elbows resting on the edge of the table, which threw back his wide shoulders and made the great, smooth-swelling muscles stand out across his back.

She did not answer him, She had turned a little pale; she was sitting stiffly in her chair; now, instead of regarding Christopher, she was staring straight at Will as one who would say: "I have started it; now come in and finish it. I can't go any further."

"Chris," said Will suddenly, pushing back his chair and turning a little upon his brother, "it was from Mr. Bannock that we heard some very important news to-day."

"I hope it ain't as bad as the way you look, Will."

"Maybe not bad to you. You seem to be accustomed to such things. But it seemed very bad to Sylvia and me. What he had to say was simply that there is another mortgage on the ranch!"

Christopher Ballantine twisted a little in his chair, with the stinging pain of that accusation. He shoved away his plate, for food had turned repulsive to him.

"Well, Sylvia," he murmured, "I guess that there ain't any other way out of it than to tell you about it all."

"I hope not," said the girl dryly. "I hope that we have a sufficient interest in the ranch to make it our right!"

In that cold remark there were so; many implications, so many connotations, that Christopher simply dared not', consider them. There was such a blank and brutal accusation that he could not face it. His courage failed him utterly.

It was not from Sylvia alone. Another blow to match it came from the other side.

"After all," said Will, brought to the point by his sister's speeches, "one need not dodge the truth. Our share in the ranch is just as great as yours is, Chris. We're each a third owner."

"Did Bannock put that into your heads?" asked Ballantine.

"We'd had it in mind long ago. Even we could see how things were going on the ranch—though heaven knows you've never told us much!"

This was from Will again.

IT had come pouring down upon the head of Ballantine so swiftly and so without warning that he could not comprehend. All he knew was that he was in a great trouble, the greatest of his life. But still he refused to examine the truth as it was presented to him. To do that meant to see that he had thrown away ten years of his life, and no man can do such a thing as that lightly.

"I've told you all I thought that you needed to know." said Ballantine.

"I understand," broke in Will coldly, swelling with his suppressed anger, "that the ranch is now mortgaged for more than it would bring for cash in a quick sale."

"Bannock told you that?"

"Never mind who told me. Is it true?"

"I dunno," said Ballantine sadly. "Maybe it is. Maybe it is!"

"Oh, Chris!" cried the girl. "What have you done with the money? What have you done with it?"

His eyes widened as he looked back at her. What had he done with the money? And this from her?

"Why not make a clean breast of it all?" asked Will in his newfound, sharp-edged voice. "You've been playing the market or something like that, Chris. Come out and let's know the whole truth!"

Speech was impossible, and the head of Ballantine sank on his breast.

"You see?" said the girl with an eager savageness that made her older brother wince again. "He practically confesses. It's exactly as I thought. For where could it have gone? Heaven knows that we haven't cost the estate a great deal—just a little every year for our schooling. And while you had us out of the way, Christopher—while you were here as the absolute master of our ranch, what have you been doing?"

Ballantine rose from his chair and turned blindly toward the door.

"That won't do!" snapped out Will. "You mustn't sneak out like that. Stand up like a man and tell us the worst of it, Chris. Confession is good for the soul."

The light he was forced to face was a torture to him, but it was nothing compared with the savage intentness in the faces of the two before him.

"It's been just bad luck," he muttered.

"Not stupidity? Nothing wrong about anything? Just bad luck?" asked Sylvia through stiff lips.

"So that Sylvia, poor girl, and I—are to be beggared? In the very beginning of life—beggared!"

"I've done my best with the place," said Ballantine, hardly recognizing his own voice. "I swear I've done my best. But things have turned out bad!"

"Look here, Chris," said his brother, smashing his fist into the palm of his other hand, "these generalizations won't do! We have to know the truth and the whole truth."

"Will, when father died, somebody had to take charge. Who was there except me?"

"Who asked you to do it? Why couldn't a competent man have been given the work? Heaven knows it would have paid us in the end!"

"Hush!" cried Sylvia. "There are tears in his eyes! There's no use talking to him now, Will."

So Ballantine was allowed to escape. He staggered through the kitchen, and in the withered, twisted, cunning face of the cook he could see that she had been listening and had overheard everything. And this, in turn, meant that the entire range would know about the scene in a week, at the most. For her busy tongue could never be still when it had such a theme as this to contend with.

He went out into the dark, breathing—deeply, and he rested one hand against the corner of the house. Still, through the open window, their raised voices came shamelessly forth to him.

"By heavens, Sylvia, there were tears in his eyes!"

"Like a whipped puppy."

"He would have been blubbering in another moment."

"My heavens, is there no backbone in him? What a shameful thing to have in the family—to call brother!"

"Hush, Will!"

"What do I care if he hears? He's ruined my life—or come close to it. Can I enter a law firm this fall in New York and hold up my end socially without a penny to live on except the paltry two thousand a year that he sends me?"

"What about me, Will?"

"It's the devil of a situation for both of us, but a girl doesn't have to have so—"

"Will, you talk like a wild man! Doesn't have to have so much? Go into any decent shop on Fifth Avenue and see what clothes for a girl cost. I don't mean extravagant ones, but just plain frocks—"

"And fur coats like the one you bought last winter? Not extravagant?"

"Well, any one can tell you that a fur coat is a necessity in the East. They outwear simply dozens of cloth ones, and—you have a fur coat yourself!"

"I had to get it when Van Dyck Thompson asked me on that motor trip. That was a social opportunity I couldn't give up. You know that as well as I do! It's this soft-headed idiot who's been ruining the affairs of the family—"

But Ballantine could endure no more. He sneaked out to the haystack which stood behind the long cattle shed. Beside it he threw himself down on his back in the spill of chaff and hay which had dropped from the stack. There he lay, fighting the agony of grief and of shame which stormed through his heart, and watching the stars, and seeing them swirl into tangled lines of fire.

At length his vision cleared. The stars burned singly above him; his pulses stirred again with a regular beat. He arose and went into the house. He was perfectly calm when he came before the pair again.

"Now," he said, as they stared scowling at him, "I guess I got to put the cards on the table."

They looked at one another.

"It is only about ten years late, Christopher," said Sylvia. "But let's see what we have, by all means!"

"The Reddick bank has the mortgages. They'll tell you about them. But I want to tell you that I think Bannock was wrong. He wanted to buy that southeast half section last spring, and I wouldn't sell, because I wanted to keep father's place intact. Bannock has hated me ever since."

"The same size?" cried Sylvia. "A rotten shell with nothing in it! An oyster shell with the oyster gone. What good is that?"

"What good is that?" echoed Will.

The elder brother looked gloomily from face to face. There was no use trying to close his eyes to it now. The facts were thrust into his mind against his will or with it. Their own voices were proclaiming them. They were equally vain, senseless. And this was the result of his ten years of work!

"Looks to me," said he, "that you both got some main line in mind. You got the law in mind, Will."

"I even have the firm lined up. Crazy to get me, so they say—I don't know why, of course. But they want me. One of the finest firms in New York. Ready for me this fall. But Heaven knows how I can do it on two thousand a year. Can you raise that to three thousand, Chris?"

"One minute, if you please!" put in the girl. "I suppose that I have some rights, or are the men in the family to have everything?"

"I want to know what you want, sis?" asked the older brother.

"I want six months," said Sylvia with a toss of her head. "I want six months to do my piece of work, and do it well. I'm not one of the old-fashioned, sentimental, milk-and-water girls. I'm twentieth century, thank the heavens! And I have wits enough to realize that there is only one thing that's worth while. It's the thing that the men are after—money! I can't earn it. But I can marry it! Christopher, I have the social footing established. I can meet money. And in six months I'll marry it and bring it home sewed up in a bag! But I need living expenses—five hundred a month is all I need for six months. If I don't win by that time, I give up all claims on the ranch!"

Ballantine could not look into her face. He could not look into his own soul, hearing such words from his own sister. But he thought of the ten years of his wasted young life, and an agony rose in him.

"I think," he said huskily, "that I can raise five thousand with a last mortgage. That would give twenty-five hundred to each of you. Is that a bargain?"

"A bargain!" cried Will. "If I don't make good in a year, I'll call myself a fool!"

"It's not enough," said Sylvia critically. "But I suppose that I could make it do! When do I get the money?"

"To-morrow, if the bank will close the deal with me."

"Good boy, Chris. Then we won't have to spend the rest of the summer on this damnable ranch! Go in the morning!"

Ballantine went out again into the dark. He sat on the chopping block and there rested his chin on his fist and tried to think, but could not. Sylvia came out to him and dropped a hand on his shoulder.

"Maybe we talked pretty straight, Christopher," she said. "But words don't draw blood!"

"Don't they?" murmured Ballantine.

"Of course not. You'll forget about all this in a month. But now I want to tell you, Christopher, that if you could give me three thousand and Will only two, it will really be worth while. Of course, when I marry, I don't intend to get some small fish out of the pond. I intend millions, Christopher. And after I have it, the purse will be open to you. You understand?"

In five minutes after she left, Will was with him.

"Of course I couldn't say anything while she was there without hurting her feelings. But really, Chris, you understand that twenty-five hundred for a girl is ridiculous. They're invited places. They don't have to pay for two, the way a man does. Fifteen hundred would be oceans for Sylvia. And besides, she won't have any tuition to pay this fall!"

HE dared not consult the evidence of his senses—of his ears which had drunk in the vain, cruel, selfish words of his brother and sister—of his eyes, which had witnessed their sneering-looks, their open contempt for him.

Through that night Ballantine sat in a deep dream, half sleeping, half waking, and, before the morning, he had crucified himself on the cross of self-abnegation.

For, he said to himself, what they declared was the truth. If he had been a clever rancher from the first, he could have made such a profit from the ranch that there would never have been any financial worries. And yet, during the past years, he had poured such a quantity of money upon the two, that he could not but doubt. They were a desert upon which a golden tide was visible only a moment before it sank from sight. They remembered now and spoke to him only of the actual cash allowance which he had made to them. But there were always e xtras. There were always bits which must be provided for. There were such things as the fur coat for Will before he made the automobile trip, and the fur coat for Sylvia on a similar occasion. Always they were pressing ahead, eager, insatiable, with their eyes bent upon a higher social position. And, after all, even with the best of times and the best of good management, it had never been a very great thing, this ranch.

It had kept Ballantine, his wife, and their three children, very comfortably, but the elder Ballantine had never contemplated anything so dashing as this project of sending the two younger offspring away to expensive private schools and then to great Eastern universities. A homely public school, a high school course, and then he would have sent them into the world. Too much education, he was fond of saying, was a poison for the mind.

Perhaps he was right. 'Perhaps, after all, in his desire to help them, Ballantine had simply ruined them. If they had received only what their own father thought best for them, they would have turned into very gentle, generous, open-hearted persons, but he, a boy of eighteen, had presumed to know better what they were fitted for. This was the result.

He had thrown away ten years of labor; he had poured forth all the efforts of his body and his brain for them; he had educated them perfectly; he had prepared them-for advanced positions in the world; but at the same time he had ruined the ranch in so doing, and he had won hot even their gratitude!

To be sinned against is infuriating; but to have the sinner fail to recognize his guilt is maddening. But Ballantine was not maddened. Going patiently over the affair, he decided that, after all, he was so deeply in the wrong that he must not strike back. He must never strike back, indeed! His hands were tied. The world was his creditor.

He went to bed, at last, in the early morning, and by that time, in his exhausted brain, there remained only a dim wonder—a wonder that God could permit a man to struggle so desperately, so honestly, and with so little effective gain!

He was soundly asleep only two hours when he was wakened, without the need of an alarm clock, by the flood of the earliest morning light. He got up at once, bathed, and dressed. Then he went down to the kitchen where the cook had not yet arrived, ate a slice of bread and butter, drank a glass of milk, and was ready to work until noon!

He took a mild comfort in that knowledge of his own peerless physical resources. He could do the work, of two or three men and he could keep it up from dawn to dark. Exertion did not weary him, apparently, and by the immense labors of these last ten years, his tremendous natural strength had been turned into flexible steel. He was clad with the powers of a giant. And-now, in the beginning of this day, as he hurried forth to the corrals, he thought of his strength with a faint glow of satisfaction.

Presently he had saddled and mounted a horse. Only when he was forced to ride to town did the pinch of penury really torment him, but when the pinch came, it was a bitter thing. He had only one passion, and that was the love of horseflesh. To have controlled some dancing, high-headed, fire-eyed stallion, trembling with speed and with deviltry, would have been a perfect delight to him. But he could not afford such a luxury as this. He must content himself with a string of common nags, greatly overworked, grudging the pitiful amount of work which they were forced to drag through, and always ungrateful to the eye. He picked out a tough roan on this morning. It was the ugliest of all his string, but it was also the strongest, and therefore it had endured the labors of the spring and summer better than the rest of the horses. At the present moment, taking condition into consideration, it was much the most pleasing to the eye.

On this he trotted away toward the town. He would have liked to have his horse bounding away at full speed, rushing hard against the bit. But he was forced to content himself with this plebeian dog trot. It covered the ground slowly. The sun rose higher. The withering heat began. The sweat began to start out of the body of the roan. The stench of his perspiration was ever in the nostrils of his rider. And still he worked patiently on.

He paused at mid-morning, fighting a fierce temptation in his blood. Then he swerved irresolutely to the side and entered a by-lane off the main road. It carried him to a pasture behind a big house on a hillside, a house pleasantly shrouded with trees, with huge barns and sheds with painted roofs, spread over the lower hollow. The Holbrook place was famous over the entire range for its beauty and for its comforts.

And here, by lucky chance, were the two people whom he loved more than he loved any others in the world. Old Tom Holbrook, in spite of his wealth, had never held him away at arm's length, and Peggy Holbrook was to Ballantine all that is delightful, all that is serenely sweet in womanhood. He did not love her; he worshiped her.

They were standing under the poplars by the edge of the pasture, watching the big stallion, "Overland." It was Ballantine himself who had named the horse when Mr. Holbrook bought the animal as a two-year old, for the sake of ultimately improving the breed of his saddle horses. Because, as Ballantine had said when he first saw the horse run through the fields, he went 'like the overland itself, with an eye of fire, a rush of thundering hoofs, and blinding speed that made the fluid miles pour behind him.

They were sufficiently gloomy. When Ballantine came up, they greeted him with a sigh and a nod.

"What's wrong?" he asked. "Has something happened to Overland?"

The stallion heard that voice uttering his name and wheeled suddenly in the pasture with a snort, tossing up his shining black head, and then along the sleekness of his side, Ballantine saw the dark impress where a saddle had recently rested and where the sweat had gathered under the blanket.

"You see, dad?" said the girl.

"See what?" snapped out Mr. Holbrook in a very evil temper.

"The way he answers when Chris speaks. Chris can even call, and he'll come! I've seen it!"

The rancher grunted. "How the devil have you managed that?" he asked.

"Oh, I have the time," said Christopher Ballantine. "Time ain't much to me, you know. I only use up about twenty-four hours a day. The rest of the time I'm over here with Overland."

"It's not the time he spends with Overland. It's his way. You know, dad, that there's only one man really, for every girl; and there's only one master, really, for every horse."

"Bosh!" said the rancher. "Infernal bosh! But tell me, Chris, can you actually make that high-headed fool come to you?"

For answer, Ballantine stepped to the fence and whistled. The stallion hesitated. Then he came with a mincing step, uncertain but eager, toward Ballantine.

"This is strange'" exclaimed Holbrook. "Mind yourself, man, or he'll take your head off!"

Ballantine grinned, and, turning his back on the approaching horse, faced Holbrook as he answered.

"There's no danger. He won't harm me."

The horse, in fact, coming up behind Ballantine, offered him no harm whatever, but reaching over the fence began to nose at his coat pockets, and finding nothing there to his liking, he put one ear back in anger and one forward with a glint of coltish mischief in his eye. Then he twitched off the hat of Ballantine with a touch of his long, prehensile upper lip.

"You see, dad! Just what I told you!" cried Peggy Holbrook.

"A remarkable thing!" repeated he. "What have you done to the brute in this month while I was away?"

"I've come over near every night. That's all. And he's used to me. Patience is all it takes."

"Patience? Patience?" shouted Mr. Holbrook. "Bah! I've wasted two years on that idiot. No, sir, there's something odd in this! I suppose you'll be riding him one of these days?"

"Whenever you please," said Ballantine.

"Ha?"

"Chris!" cried the girl. "You don't mean—"

He was already through the fence.

"Don't, Chris!" she warned him. "You' re mad. Why, Charlie Pickett was here only an hour ago, and he lasted just a minute and a half on Overland!"

"Look at what he did!" answered Ballantine, shaking his head.

He pointed to welts along the flank of the stallion.

"The fool was fighting Overland; I'd as soon fight a nest full of tigers!"

"How would you manage to ride him, then?" asked Holbrook, scowling. "Let me see what you'd do. There's a saddle and bridle in the shed, yonder. Don't let that hold you back!"

"Chris!"

This from the girl in an accent of very real alarm.

"There's not a bit of danger," he said. "Not a bit. You see?"

He was still speaking when he laid hold on the mane of the big horse, made a short step beside him, and then swung onto his back. Upon the face of Mr. Holbrook appeared mingled horror and bewilderment. And the girl turned pale and doubled up her fists like a frightened child.

"Oh, Overland, good boy!" she whispered. "Don't hurt him!"

Overland tossed up his head, and by that gesture turned himself into a giant. He was a full sixteen hands and two inches, fitly limbed and fitly muscled for that height. He could have pulled a plow and looked fit for that work, from the bulging might of his quarters, except that the bone of the lower part of his legs was hampered by any coating of flesh, looking like finest hammered iron. And only the blood of the desert could have fathered that head of his, with the mystery of the far horizon still reflected from his great brave eyes.

For an instant he stood in this fashion—at attention, so to speak—then he flung himself into the air, his ears flattened, his head stretched forth, his back arched. In the very midst of his leap he seemed to recall that this was not a matter to be fought out. He landed as lightly as a feather, in full galloping stride and swung away through the pasture. And there sat Christopher Ballantine leaning over his neck, guiding him, indeed, with merely the light pressure of his hand, and with the wind of the galloping blowing the mane straight back into his face. Like a thrown spear from a giant's hand, a flung javelin of polished ebony, Overland sped to the farther end of the pasture. There he swerved and came racing back. He heard the voice of his rider; he pricked his ears, lifted his head. He seemed to be considering the words with a man's intelligence. And so he slowed to a stop where he had begun, and Ballantine slipped to the ground.

"TEN thousand devils!" cried Mr. Holbrook. "That horse has been enchanted! I'll swear it!"

"Dear dad, you've sworn already!"

He brushed her objection aside. Without his oaths he felt like a naked man, or a dumb one.

"The old rascal has had his wits stolen from him, and you've done it, Ballantine. I have five hundred dollars for you, son, if you will do that with a saddle on him, too."

"Five hundred? For me?" said Ballantine.

The blood flooded into his face.

"I hope," said he, "that you're jokin', Mr. Holbrook."

"Is five hundred dollars a joke?" blurted out the rancher. "Since when, Chris?"

"Hush, dad, hush!" cried Peggy Holbrook, even stamping her foot in impatience that her father should not have perceived the root of Ballantine's embarrassment. "One can't pay a friend, I suppose?"

"A friend? Oh, I see what you're after. But, I tell you, I've had that offer standing for a year. Five hundred to any man who could ride him."

"It's worth five million in pleasure!" said Ballantine. "It is, sir!"

The rancher, studying the flushed, joyous face of the younger man, smiled and nodded.

"I believe you," he said. And he added slowly: "Ballantine, you love that brute, eh?"

"Like a man. More than a man!"

"I'll tell you what. For half of what I paid for him when he was a colt, I'll sell him to you. I paid two thousand for that horse, Ballantine. He's yours for a thousand!"

The eyes of Ballantine shone with a savage hunger. Then he shook his head.

"I can't afford it," he said.

A little embarrassed silence followed on this.

"Chris," broke out the girl, "how can you be so self-contained? Isn't there any impulse in you? Oh, if I wanted a horse as you want that one, I'd mortgage my soul for it!"

She was so pretty as she spoke, with her head in the air, and her hands clenched, that Ballantine looked on her with a dumb worship.

"Suppose that your soul wasn't your own?" he asked her.

"I don't know what you mean."

"Nobody would, I guess," sighed Ballantine.

The rancher turned away. "Think it over, my friend," said he. "A one-man horse like that ought to belong to the man who can ride him." And he went off whistling.

Christ turned to the girl and found that she was resting her elbows on the top of the fence, her abstracted gaze following the horse.

"I've never seen dad talk like that' before," she said.

"Like what?" he answered, quite at sea.

"He's not open-handed. Not a bit! But after all, it is impressive—what you've done with Overland. Chris, how did you manage to do it?"

"I don't know. Just bit by bit. Taking him gradual." r

"But you had to get in the corral with him, to begin with."

"Yes!"

"Weren't you afraid?"

He could see that she was conducting a little cross-examination of him for the sake of some hidden purpose. And her voice was so gentle, and all her air so intimate, so quietly kind, that a great vague hope rose up in Ballantine. It made him quiver through all those massive muscles which clad his body with power.

"I was afraid—sure!" he admitted.

"But you fought the fear down, Chris? Was it hard to do?"

"Mighty hard. It was like walking in to a tiger, at first."

"When did you do it?"

"There was a bright moonshine one night. I came over after supper and went into the corral."

"What did he do?"

"He rushed at me."

"And you jumped through the bars?"

"No, I stood quiet and waited for him."

"Chris!"

"I was too scared to move—I guess!"

"Oh!" she murmured, and there was just a shade of disappointment in her voice. "But it was a brave thing to do," she added, "just the same. You love him, Chris?"

"There's only one thing in the world that I love more."

"Oh, of course. Your brother and sister. But that's different."

"Not them," he said huskily.

She looked sharply over her shoulder at him.

"What else, then?"

"Peggy—" he began.

She whirled around on him. "Heavens, Chris, what's the matter?"

But he knew that she guessed what was to come; knew that he would have no success, and yet he could not help going on with it.

"It's you, Peggy."

A shade rippled over her face; then she broke into laughter. "Chris, Chris, what are you saying?"

"That I love you, Peggy. And you don't care a snap for me. I can see that. But I had to bust out with it and tell you."

He had turned limp with despair. But, all the while, her face was a study composed of mirth and sympathy and surprise.

"I don't mean to be harsh, Chris. But how could I ever have guessed it?"

"I dunno," said he slowly. "I guess you couldn't. Except that I been coming over here pretty near every week, for the last year."

"Were you coming to see me?"

"Yes."

"I thought if was dad—and the horses. Oh, Chris, I'm terribly complimented that you could care for me, but don't you see—somehow—it just couldn't be! I'm mighty sorry!"

"Will you do one thing for me?"

"Anything, almost, except that."

"Then forget what I've said to-day!"

"I shall, Chris. Do you have to go?"

"I'll be going along. So long, Peggy."

His last glimpse of her showed him a face still struggling with the same mirth, the same compassion, the same astonishment and scorn. And it seemed to Ballantine that he hardly had the strength to climb into the saddle on his horse. For in the past few minutes a mirror had been held up before him, and in that glass he beheld the image of himself which the rest of the world saw. To them he was a great hulking fool, a coward, a flabby piece of ineffectiveness. He could have endured everything he had seen in the girl's eyes except her scorn. But that stabbed him to the heart.

He was so tortured that he cried aloud: "Maybe they're right! Maybe I ain't no more'n worth that!"

The ears of his horse pricked at the sound of his voice. There was no other answer. Indeed, there was only a single rock of strength which supported him, and this was the sense that one creature understood him and loved him. That was Overland. The horse, at least, had found in him more to trust and to honor than in any other man. He took that strange comfort to his heart and went on, sick to the soul.

And he was bitterly shamed, also, that he should have exposed the state of his heart to the girl and been so casually rejected—and yet with such an effort at kindness! He could have wished for destruction at once! Anything to swallow him up in oblivion.

For this was the second terrible blow in the course of a few short hours. He had found that the brother and sister who were the very cause of his existence, cared no more for him than to use him. Now the woman he loved was snatched from him to the illimitable distance of contempt!

And he wondered to himself what there was that made him continue this wretched existence. It was for one purpose only—to strive to get this last thing that his brother and his sister wanted. It might complete his miserable labors. It would leave him—what? At least, having completed his work, he would be ready to die!

And he was only twenty-eight. But he had never been young. He had passed from childhood to old age at a step. Fifteen years of careless boyhood and young manhood had been tossed away and exchanged for the bitter duties of mature life. The pity of it was that he did not know the value of the thing 'which he had lost.

He let his mustang plod on to town.

He had intended to go at once to Patrick Reddick and talk to him about the additional loan. But he felt that he did not have energy enough in his heart to speak now. He tethered his horse near the watering trough in front of the hotel and safe down on the veranda to rest, and while he rested, he dared not give his thoughts rein. He had to keep them in check with a bitter vigilance, for fear lest they should run away with him.

There were a dozen other men on the veranda of the hotel. Their faces were all a blank to him. He did not heed their voices, except for the heavy, rolling tones of big Jeff Partridge at the farther end of the porch. Partridge was the strong man from the North. He was reported to have lifted thirteen hundred pounds of dead weight and put it on a scale in the blacksmith shop. But the rest were nothing to Ballantine until the door of the hotel slammed and some one, lurching out, stumbled against his chair. He looked hastily up into the handsome, flushed face of young Harry Reddick, the banker's son. Obviously Harry had been drinking again, and even a little more than usual. Where he found the moonshine it was hard to tell, and it always drove him half mad. He was more than half mad on this day. It needed no more than the merest touch to quite unbalance his temper, and this touch was supplied, it seemed, by his lurch against the chair. He flew into a passion at once. The veins in his forehead seemed to stand out horribly.

"Hey!" he cried. "Did you try to trip me, you hound?"

The other voices on the veranda were struck into instant silence. Two or three in the distance rose, to watch the scene the more easily. And Ballantine felt the touch of expectancy. There must be a fight. No man could endure such language in silence and afterward hold up his head in the West. But he, Ballantine, must endure. For this was the banker's son, and in five minutes he would be talking to that man!

"I didn't bother you, Reddick," he said quietly.

"You lie!" shouted Reddick.

A great wave of something rose in Ballantine. He could not say what it was, but it took him by the throat and made him shiver and shake, and cleared his eyes and made his mind as keen as an edged tool. Yet he did not stir. He dared not stir, though there was an instinctive life twitching through all his muscles.

Yet he said to himself: "Reddick is a known gunman. Am I his next victim?"

"Get up!" shouted Reddick, snarling like a mad dog as he saw the other submitting. "Get up and let 'em look a liar in the face and see what you're like!"

Ballantine rose. He hesitated, but it was only for a fraction of a second. Then he turned and walked down the steps toward his horse. He could feel the flesh drawing on his face. He could feel a chill as though a cold wind were blowing over him. He knew that he was white as a sheet.

And, behind him, he heard something like a groan from many throats, a subdued and angry sound. For it is an ugly thing to see a human being so utterly shamed. That sick, dreary voice gave way to a chuckle here, and a loud laugh there. But he did not look up at them. He twitched the head of the roan around and rode off down the street for the office of Patrick Reddick.

PATRICK REDDICK was one of those men who, having raised themselves from nothing, cannot forget the oblivion out of which they have come. If there were richer men in the world than he, he felt that none had come up from such humble beginnings. Consequently he always made a point of his original poverty, which is usually a point with your true self-made man. His vanity rules him.

He insisted, also, in keeping the bank in its old quarters.

"Fine clothes don't make the man and stone columns don't make a bank," he was fond of saying.

So he kept the bank looking like the fašade of a general merchandise store. Into the bank went Ballantine. He had to wait half an hour to see the president, but finally he was admitted. Mr. Reddick sat with his chair tilted back into the window, and puffed on a cigar.

"Sit down, Ballantine," he said. "What's wrong now?"

Ballantine sat down and told his story. It began with a recital of recent disappointments, including the price for which he had had to let that year's sale of cattle go. It continued through other things. And, finally, he made his proposal for a loan.

The banker waited till he was quite done. All the time his bright little eyes, half encased in fat, thick wrinkles, never left the face of his visitor.

"How long have you been running the ranch?" he asked at last.

"Ten years."

"What was that ranch worth when you got it?"

"I don't know, exactly."

"Well, Ballantine, I'll tell you what it's worth now—just exactly the total of the mortgages that are slathered all over it. Young man, I wouldn't give you another five hundred dollars—let alone another five thousand!"

"Why," began Ballantine, "the land and the cows—"

The other broke in. His conversational habits were not the most polished in the world. He made a rule of saying what he thought when he thought it.

"The land and the cows are all right," he said. "It's the owner that I object to. It's you, Ballantine. I'll be frank with you. I'll tell you the truth and the whole truth right out. What I'm gunna say to you now ought to be worth a whole lot to you, I say! Take it the way it's gunna be handed out. No malice—but facts! Ballantine, you begun with a big thing on your hands. To-day, you've got nothing!"

"Bad luck—"

"Bad luck the devil! There ain't such a thing as bad luck. Ballantine, I tell you that when I was only the owner of that little place there, I was better off than you are to-day!"

He pointed, as he spoke, to a photograph which hung upon his wall and showed a little shack on the side of a mountain surrounded by worthless second-growth timber.

It was the boyhood home of the banker. Ballantine had heard the story of his rise from those surroundings at least a hundred times.

"I was better off," continued the banker, '"because though I didn't have nothin' else, I had hope. And hope is a great thing—hope and determination and self-confidence and self-respect. I say that all of them are great things for a man to have!"

As he enumerated these qualities, he shoved a stubby forefinger at the face of Ballantine. Behind that finger so stiffly extended, Mr. Reddick squinted as though he were looking down the barrel of his revolver at an enemy. And Ballantine watched him, fascinated. The nail of that right forefinger had been split by a saw edge in a mill in one of Reddick's early business ventures. Now the whole end of the finger was twisted and gnarled, but it looked stronger than ever—a hardy and brawny finger. Such was the whole man, the whole soul of Patrick Reddick, thought Ballantine—twisted, deformed, but wonderfully effective, wonderfully 'strong.

"Them are the things that a man needs, Ballantine. For a young gent just starting out in life, each of them qualities is better'n a thousand dollars of capital put out to good interest. A sight better. What d'you think that I had when I started out? Nothing but them qualities. And that was what growed into this here bank!"

He gestured around him to the four ugly, barren walls of the room, as if each wall gave onto a vista of immense beauty, immense wealth. Then he turned to Ballantine, and his benignant smile of self-satisfaction turned to one of a sort of sad sternness.

"Ballantine," he said, "you ain't hopeful, you ain't got determination, you ain't got self-confidence, you ain't got self-respect!"

Years have a vast weight, in conversation. And Ballantine felt himself borne down by the authority of Mr. Reddick's position, and of his age. He could not differ from this man. But, turning his own eye inward, he found nothing but proofs that the other was right—hopelessly, horribly right! He could only sigh and bow his head.

"Look how you should of come in here!" exclaimed the banker. "You should of come in wearin' a smile, with your head in the air, and full of your schemes. What are your schemes, Ballantine?"

"Why, sir, hard work—"

"Hard nonsense!" exclaimed the banker. "If a young man under thirty—think of it—a boy under thirty—ain't got a dozen different plans for pulling the earth up to the moon or hoisting the moon back to the earth, he ain't worth his salt, hardly. Ballantine, I'm talkin' free and hard to you, for your own sake. You're too old. You ain't nacheral. You ain't normal. You ain't never been foolish—and that's why you're a great fool!"

He paused, smashing his fist down upon his desk as he made this point, and letting his voice ring so loud that Ballantine could feel it shivering through the walls and reaching, beyond the office, the ears of sundry clerks seated upon sundry high stools. He could see their heads raised; he could see the grins of mute intelligence which they flashed to one another. And the soul of Ballantine shrank small and smaller in him.

Mr. Reddick had gathered force as he went on; now he had become a resistless avalanche.

"Lend money to you?" he exclaimed, coming to his point at last. "No, Ballantine, I wouldn't lend a copper on that ranch. Not till there's some one else running it. You got about a thousand dollars in this bank—and that's all you have. You got that much cash, but you ain't got a cent of credit. 'Go back and think about what I've told you, young man. You could go around the world, but you'd never find no more valuable advice. Go along and turn what I've said over in your head. Let it work and grow into something worth while. Good-by, Ballantine, and remember that they's only one thing in the world that folks look for in a man, young or old—strength! Strength! Strength!"

He beat out the words upon the wall of his office until a faint, thundering echo rolled throughout the old building.

Ballantine went out into the anteroom. There he stood for a moment with his head bowed, his hat twitching in his fingers.

"You've had a hard time, I suppose," said a girl's voice.

He looked into the face of Reddick's stenographer.

"He's grouchy this morning—he's like a bear," she said. "I'm sorry!"

"You're sorry?" said Ballantine. "Well, ma'am, I'm not. Because this is the right way to start the day!"

What amazed him most was to find that he meant what he said. All the words that the banker had spoken had sunk into his soul like the truth out of the gospel. They could not be avoided.

He could not argue down such bald and imperatively certain facts. Everything that the older man had said had been said with authority. And Mr. Reddick stood like a prophet of wrath above the soul of Ballantine, foreseeing his destruction in the very near future.

So that Ballantine,' suddenly, cast aside a weight from his mind, and that weight was responsibility.

"I'm bankrupt," he said. "I'm smashed!"

No, there was still a thousand dollars between him and ruin. He went to the cashier's window.

"What's in my account?" he asked.

Presently the answer came back: "A thousand and twenty-four dollars, Mr. Ballantine."

"That'll be just enough," said Ballantine.

He called for a blank check, scratched out the sum hastily, and signed his name. Perhaps it was the last time in his life that his signature would mean money. He passed that check back through the window. He would have this money in fifties. Twenty fifties came back to him, all new bills, compressed into a solid little sheaf that he could pinch between thumb and forefinger.

But what he was holding between thumb and forefinger was not paper money, but a mighty black stallion, with a coat like water under the stars, an eye of fire, a soul of pride. Overland was his! Overland was his!

He leaned for a moment against the wall and took the full glory of that thought home in him.

He had lost his brother and sister; he had lost the woman he loved; he had learned that he was a worthless ruin as a business man; he had been disgraced in the eyes of the entire world as a weakling and a coward; but now he was to take in exchange for all of these injuries—a horse!

It was enough, he told himself. Rather be mounted on the smoothly winged speed of Overland, rather be served by the stanch heart of the stallion than to have the mockery and the half-scornful affection of men and women around him. Rather be free with Overland than a slave with human company!

And he was free, free as a cloud in the sky. For there was nothing on earth which could make a demand upon him. He was of no service to his brother or to his sister. Rather, he was a heavy encumbrance to them. He would go away, and let them have the ranch.

He looked up from his dream. There were half a dozen people writing checks or waiting for money; he found that the eyes of them all were fixed upon him in a startled fashion. He must have spoken aloud, and what had he said?

It made no difference. He was nothing to them; they were nothing to him!

HE went out to his horse, mounted the weary roan, and turned it up the street.

Suddenly he found himself looking at the town with new eyes. It had always seemed to him, in the past, like a great center of power, a mysterious dwelling place of strength. Now he beheld it as a little sunburned village, huddled at the foot of a mountain. A pleasant scene, but not an important one!

He let the roan go slowly. There was no cause for hurry. He had nothing left to do except to pay the money down for Overland, and there was no chance that Overland would be taken by another man, for the simple reason that no other man could ride the great stallion.

He came, again, to the hotel, and as he passed, he heard laughter—he heard a great bass voice booming something in his direction. That was Jeff Partridge. He checked the roan and looked across the street. Yes, there was Partridge with his head bent back on his great brown throat, laughing heartily. And all of those around him were laughing, also.

Once more that wave of emotion swelled in Ballantine as it had once before, on this day; but now he recognized it. The thing which made him tremble through all his bulk was anger; the thing which made his eyes clear, his brain cold, was anger. Yonder was Jeff Partridge, a big man and a strong one. But was not he, also, big? Was not he, also, strong? Moreover, he was free, and the sense of freedom like an intoxicating wine mounted to his head and swayed him with consuming joy. He dismounted, threw the reins, and stepped up on to the veranda. Here was Jeff Partridge just before him, lolling in his chair and insolently pointing with his finger. Ballantine leaned above him, and as he leaned, he felt his power tingling in his heart, in his hands.

"Partridge," he said, "are you laugh-in' at me?"

Wonder struck the laughter from the face of the other.

"Laughin' at you? Why, the devil, man; why shouldn't I laugh at you?"

"Here's a good reason to stop laugh-in'," said Ballantine, and he struck Partridge across the cheek—lightly—a mere flick of the fingers, but it made a deep white imprint—a white print that turned instantly to crimson.

His first astonishment still kept Partridge motionless, but only for an instant. Then he leaped to his feet and struck as he leaped.

There was no confusion in the eye or in the mind of Ballantine. With the very first movement of Partridge, he knew that he was the master. For how absurdly clumsy, how absurdly slow were the motions of the huge cow-puncher and miner! He could have struck twice while the other was swinging once!

He put aside that roundabout blow with a raised hand. Then he struck home, to the point of the jaw, and saw the face of Partridge sag into a stupid lifelessness—saw him drop heavily to the floor of the veranda. He turned on the others.

"There might be somebody else," said Ballantine quietly. "There might be somebody else that feels like laughin' and wants to know reasons why he shouldn't. Let him step up. Let me hear him!"

He looked up and down the line. There was not a man who moved. Ballantine walked slowly before them. He let his eyes rest insolently, freely, on each face in turn. What was the strength and the mystery of these men? Once looked into, they proved themselves hollow, empty cups. But when he had been a slave to necessity, they had all seemed mighty men!

"I've heard tell," said Ballantine, "of gents that was so dog-gone strong-handed and so easy-goin', that they wouldn't take nothin' from nobody. But I see that you ain't that kind. You're a bunch of rats! A bunch of yaller-hearted rats. You sit back and snicker and giggle like fools when you think that there ain't no danger. But when danger comes around the corner, you sit fast, you sit tight! Lemme hear you peep! Lemme hear you talk some! Lemme listen to your ideas! You was laughin' large and loud a minute ago! What's come of all the laughin', partners? Fist or knife or gun, I'm ready and waitin' to hear you!"

There was not a sound from them.

"Now tell me where Harry Reddick is hangin' out," said Ballantine. "I'm a free man, now, and he'll hear something that I have to say to him. Where's Harry Reddick?"

Still there was not an answer. Immediately before him sat Lester Jackson, a wide-built man with the strength of an ox. He stooped and took Lester Jackson by the neck and heaved him to his feet. And Jackson was limp and light in his grip.

"Where's Reddick?" he snarled out.

"He's gone—inside!" gasped out Lester Jackson.

He tossed the informant to one side; and Jackson staggered against the wall of the hotel. How strange it was. They were all turned into mere shadows of men—mere paper images. They crumbled at his touch!

He entered the hotel. The proprietor, having sensed some strange occurrences outside on the veranda, was hurrying out from behind his desk.

"Where's Harry Reddick?" asked Ballantine.

"Ah, Ballantine. You'd better not see him. He's just sobered up, and he's as ugly as a devil—particularly after—"

"Where's Reddick, you fool!" snapped out Ballantine. "I don't want your advice!"

Now there was no more inoffensive man in the world than the good proprietor of the hotel. And he stared at Ballantine as at a man suddenly gone mad. He hesitated only a second, however.

"Reddick is over yonder," he said, and pointed.

In a stride Ballantine was at the door of the room. He saw Reddick sitting by the window; and Reddick leaped to his feet as he glimpsed the other from the side. Instantly the hand of Reddick went for his gun.

But he changed his mind. A devilish expression appeared in the face of Ballantine. It could not be that any man had changed heart in so few moments!

"Well, Ballantine," he said, "what'll you have to-day? Are you back here for a little explanation?"

"The boys are waitin' out on the veranda," said Ballantine. "They are waitin' to see you get down on your knees. They're waitin' to hear you ask my pardon."

"You're turned mad, Ballantine!" cried the other. "Why, you fool, I'd break you in two!"

He glanced over the arched breast and the thick-muscled body of Ballantine and changed his mind.

"Or blow your head off!" he said.

"Ah," said Ballantine, smiling and speaking with a voice which trembled with the joy of vengeance, "I was hopin' that it would be the guns. Are you ready, Reddick? Then make your draw!"

A shadow crossed the eyes of Red-click, a faint shadow of doubt, even though he had conquered so many times in hand-to-hand battles. And Ballantine, seeing that shadow, knew that he had won already.

He stepped slowly forward. "If you pull that gun I'll kill you, Reddick. Better trust to your hands—"

Twice Reddick wavered; then he determined on the gun, and jerked it out. It was much too late. For Ballantine was near enough to close with a single leap. With his left hand he caught the right wrist of the other. And he felt the hard tendons turn to mush beneath his fingers. He heard the dropped gun clang on the floor as the power of his grip turned that deadly hand of Reddick to a numbed, useless thing. \

All this he did with his left hand, in a single grip. Then he smote up with his right, sharp and short, and tapped Reddick under the jaw. It snapped his head back on his broad shoulders. He turned limp, and slid out of the arms of Ballantine to the floor and lay there on his face.

Oh, to say that compassion and that shame for so easy a victory touched the heart of Ballantine then! But it would not be true. He felt in himself, as he looked down at that helpless body, a root of the most devilish impulses, only. Then he leaned, took the senseless body by the long, blond hair, and dragged Harry Reddick out to the veranda.

Before he reached that porch the pain had brought back the sleeping senses of Reddick. He was kicking and groaning and struggling half blindly by the time they arrived. The ten or a dozen who had been there before had been trebled in the interim. The news was abroad that there was trouble and fighting at the hotel, and that was enough to bring the crowd. For humanity has for calamity an extra sense, as buzzards have for new carrion, standing a hundred miles across the misty desert air to find the dead. So the people of the town had gathered in a brief, hurrying rush to find out what was happening at the hotel. These had arrived; others were coming. The blacksmith stood in his leathern apron three or four doors away, holding his sledge still in one hairy arm and shading his eyes against the sun as he stared to the hotel veranda. Every one was out.

And Ballantine, surveying all of these, was content. He wished to have every stroke of his ork noted; and this was an audience after his own heart.

He flung his prisoner down on the porch. Reddick sprang up and lurched in with a moan of shame and of rage. But the right fist of Ballantine was turned to a ragged lump of steel. It smote Reddick down again and bespread his face with crimson.

"Reddick," said the conqueror, "some of the boys, heard you talkin' big and broad about me a while back. I didn't have time to tend to you then. But I got the time now to stand by and let the boys hear you tell me that you're sorry that a skunk like you should talk to a man!"

"I'll see you—" began Reddick, groaning with rage and shame.

His voice was cut short, for Ballantine caught his arm and twisted it until the other yelled with agony.

"Help!" he shouted. "He's broken my arm."

"They stand still," said Ballantine grimly. "They're a lot of coyotes after your own pattern, Reddick. They'll stand still and watch a wolf eat you, and then they'll come sneakin' in and mumble your bones. Reddick, lemme hear you say it, or I'll tear you to bits!"

The agony made the eyes of Reddick start from his head, but he shouted suddenly: "I'm sorry that a skunk like me should have talked about you, Ballantine."

That was all. Ballantine tossed the other from him and turned his back and strode away to get his horse.

BUT those who looked on—and well they understood it—had seen not the physical beating of a man but the crushing of his very soul, and the horror of it turned them sick. If the sheriff himself had started out on the scene, and shouted for their help, they could not have raised a hand to stop big Ballantine. He walked slowly among them, and his back was turned in deep contempt upon the fallen man, as if he knew that the very heart of his victim had been so crushed that Reddick would not dare to try to shoot even at his turned back!

And the crowd saw Reddick stagger to his feet, saw him fumble among his clothes, saw him find and draw a gun! He stood with it poised in his left hand for a moment, a thousand emotions of fury and of shame fighting in his face. Then he burst into tears like a whipped child, dropped the weapon, and fled to hide his face from them!

Yes, fled like a beaten boy, not like a man, and a giant among men! He fled, and, seated in the saddle on the roan, Ballantine watched him go—and smiled!

He turned the roan up the street. He rode slowly. He rode whistling as he went. He was free! He was free! Nothing under heaven had any claim upon him! Only Overland had a call for him, heart to heart, fierce power to power!

He rolled a cigarette. He lighted it and snapped the burning match into a cactus. What matter if it caught fire? Still he went on, his head high. He was not turning over in his brain the events through which he had just passed. They were in the past and almost forgotten, but what filled his attention now was that world which lay around him.

All the plain, all the hills, and yonder his namesake, Mount Christopher, climbing high into the blue of the sky—and all shining in the sun which blazed from the bald, polished faces of cliffs—how beautiful were all of these, how strong, how new, as though created in another form this moment and striking his eye for the first time. The fact that there was a little ranch somewhere in this wilderness of big things was of no importance. The fact that he was a part owner of it was nothing to take into his mind. All that he had been was dead!

Hoofbeats sounded behind him. Out of a cloud of dust, Sheriff Joe Durfee drew rein beside him.

"Pull up, Ballantine," he commanded. "I got something to say to you."

But Ballantine did not halt the roan. He let it wander slowly on while he studied the sheriff. Always before, Durfee had seemed to him the very incarnation of the spirit of combat, dry, lean, keen. Now he was less than a common man. He was nothing! A gesture could crush that frail body.

"I'm on my way and I'm busy, Durfee," he said. "If you want to talk to me, ride along with me!"

He half expected a storm, but the sheriff merely colored a little and then nodded.

"I see how it is," he said, as much to himself as to his companion. "This here job you've done of Partridge and on Harry Reddick has got to your head, like red eye. Is that it?"

"I dunno," said Ballantine. "I'm not botherin' with thinking. I don't have to!"

"Son," said the older man, "I maybe see more of what's inside of you than you think. A pile more! You've held in for a mighty long time. Now you've busted loose. Partner, what I come after you to say, is this: I've figgered out what's wrong with you. I don't aim to have no trouble with you if I can help it. But, Ballantine, don't aim to think that you can ever come into town again and do what you done to-day and get away with it. The boys wouldn't stand for it twice. I couldn't stand for it twice. This day you picked on a couple that needed a fall, and you give it to 'em. To-morrow, you'd be turned into a bully. Mind you, Ballantine, I ain't threatening. I'm telling you to watch what you do from this time on!"

"Sheriff," said Ballantine, "what you want' and what you think ain't of no importance to me. I'll tell you this: You and the rest have treated me like a mangy cur. Now I'm through sneak-in' and crawlin'. From now on, I'm a man. And if there's ever any trouble that makes you come for me, come with both of your guns out and don't waste no time talkin'. Because words won't do no good!"

He turned his shoulder on the sheriff and sent the roan into a canter, and the sheriff did not follow. Where the trail turned sharply, a quarter of a mile ahead, Ballantine looked back from the corner of his eye and saw that the sheriff still sat in his saddle where Ballantine had left him.

And Ballantine smiled to himself. It was all very well. It was all exactly as he would have had it!

The big house of Mr. Holbrook loomed in the distance to the left, above the trees. He made for it at a round gallop, with the roan grunting as its tired forelegs pounded the trail. Then, under the shadow of the thin poplars, he dismounted, stripped the saddle from the back of the tired little mustang, and went to the house.

Peggy and Mr. Holbrook came together to the door; and he saw the start of surprise and the faint flush on her face as she saw him. He regarded her gravely, judicially, in turn. She, to his surprise, had not changed in his eyes as the others had changed. She seemed as delicate and as pretty as ever, as frank and as charming.

"Well, son?" said Holbrook. "Here you are back again! What's wrong now? Will you come in?"

Ballantine shrugged his shoulders. "She's told you, I guess," he said, watching the girl.

A guilty flush mounted her cheek.

"Told me what?" asked Holbrook.

"That I wanted to marry her?"

"Why, Ballantine," said Holbrook gently, "there's nothing to prevent a man wanting to marry any girl he sees."

"Well," said Ballantine, "she'll never have to trouble about that ag'in. I won't bother her. But what I've come back for is the hoss. I want the stallion, Mr. Holbrook."

"Ah? I wondered if that wouldn't tempt you, Ballantine! I wondered!"

He added: "That price I named is really a bit too much, considering the fact that no one can ride the brute, except yourself, and therefore—"

"I was never strong on bargaining," said Ballantine calmly.

He held forth the money. "Here's a thousand dollars. Do I get Overland?"

The other took the money with a somewhat reluctant hand. "A thousand dollars is a good deal," he said, "for a man who isn't particularly flush with money. And in fact, Ballantine-—"

"Let it go at that! I'm satisfied. I'll take Overland."

"By all means. He ought to belong to you. By the way, Ballantine, have you had some good news?"

"Why d'you ask?"

"You seem changed—happier—bolder, I might say!"

"I've had the best news," said Ballantine, "that any man ever had!"

"Ah, that will be a legacy, I suppose?"

"Ay. Freedom!" said Ballantine. "It was given to me sort of unexpected. Like stumbling onto a gold mine in your back yard, you might say."

"Freedom?" echoed the rich rancher.

"That's it!"

Holbrook rubbed his knuckles across his chin. "Well," said he, "you're talking around the corner from me. I hardly understand. But let that go. Are you coming out, Peggy, to see Overland go?"

"I'm coming," said she, in a very subdued voice.

Ballantine led the way to the corral, dropped saddle and bridle on the fence, and entered the enclosure of that pleasant little pasture where Overland ruled like a solitary king on a throne. It was nothing to saddle and bridle him. The big horse stood like a lamb throughout that ceremony. But when Ballantine swung into the saddle, and felt the great powerful body quivering under him, a new and hot temptation ran through his veins. It was easy to rule Overland by love; but how wild and fierce a pleasure it would be to rule him by sheer strength of will and hand!

THE rancher was all admiration. He kept nodding and smiling and calling to his daughter: "Look at that, Peggy! Remarkable, I call it, for a man to rule that horse as Ballantine does. Look at that! Obeys him like a high-school horse, I say!"

Peggy answered not a word. But her intent eyes were fastened upon the rider, not the horse, as Overland went back and forth happily, lightly, under his rider.

"There's something wrong, dad," she said in a low voice, not meant for the ear of Ballantine. And, indeed, it would never have reached the hearing of that other. Ballantine who had first spoken to her and told her of his love for her that morning. But this new creature was all of nerves and impulse, a very thing of fire. And he heard—heard while he reined Overland back and forth. "There's something wrong, dad!"

"Wrong with what, Peggy?"

"Hush!"

"Wrong with what? With Overland-I never saw him better, and he's transformed—'transformed with kindness, Peggy. Ah, there's the greatest power in the world if we were all not too proud to use it. Too proud! We'd rather break hearts!"

"I don't mean Overland, but Chris. He's different."

"Different nonsense!"

"Something has happened to him. Look at his face and his eyes."

"Rot! And yet there is something changed in him. A bit terser—a bit abrupt, I'd say. Like a man in pain."

"Or in pleasure!"

"What d'you mean by that, Peggy?"

"Dad—oh!"

This last was caused by a sudden change in the manner of Overland. For from a gentle trot he had come to a sharp halt and stood, now, with his head tossed high, one ear flattened along his neck, and one ear keenly pricked, the very picture of a horse asking a question, and as though he said to himself: "Is this possible?"

For Ballantine had drawn in hard on the curb. It was the jerk of the bit that had stopped Overland, but it was not a thing of the flesh that made him stop so short. Rather, he was saying to himself: "This was all persuasion before. What is it now?"

If he had any doubts, they were removed at once. The soft voice of Ballantine had turned harsh and stern: "Move on!" he commanded. "Get some life into you, Overland!" And he accompanied that word with a touch of the spur. That was enough. Reason fled from the brain of the stallion. For this was the very manner of those other men who came to tear at him with whips and with sharp steel and strive to break his heart and his spirit. He had beaten them all. He would beat this man, also. Bring fire to powder, and there is an explosion. Bring force to Overland, and there was sure to be an explosion also.

He shot up into the air, driven from four powerful springs. He landed again on four stiff posts of steel that jarred the rider to his teeth.

"Chris!" cried the girl. "What have you done to him?"

"Ballantine, what's wrong!"

This from the father. But Ballantine had no care for-their exclamations. His hands were full. First he put on the jaw of the stallion a pressure such as that outlaw had never felt before, a pull that might have broken the bones of another horse. And even Overland had to struggle to thrust forth his head. His sides, meantime,' were crushed by the gripping thighs and knees of Ballantine. And, at the same time, his flanks were raked with the spurs. . "Not the spurs, Chris! You'll drive him mad! He'll kill you!"

"This hoss? I'd eat three like him for breakfast," snarled out Ballantine.

And then speech was impossible. He was caught into the heart of a hurricane. For Overland broke forth at once with all the tricks which he had ever used in all his struggles with a hundred expert riders. He broke forth with fury, but not with cunning. He was too startled for that. There was fear in his heart, a great, cold fear, for the transformation of the man upon his back was a thing bewildering—not to be understood. This was he whose voice had ever been softer than running water, whose touch had been nothing but a caress. Now he was transfigured to a wild cat whose raking claws were in the flanks of Overland.

So he fought in a reckless ecstasy, blindly, wildly, without brains. He hurled himself into the air and smote the earth on stiffened legs. Then up again, down again. He tried to tie himself into a knot in the mid-air, and landing with a thump, he cast all of his weight upon one hardened foreleg. Even that whip-snap shock, though it made the rider reel, did not dislodge him, and still the raucous voice into which the gentle speech of Ballantine had been translated, cursed and raved and mocked at him, and the spurs bit deeper.

The girl fell into an ecstasy of terror. She ran to her father and caught him.

"Dad, dad, for heaven's sake, stop it!"

"Keep still, Peggy," he answered, pushing her away. "Don't bother me. You'll never see such riding as that if you live to be a hundred. What devil is cased inside of Ballantine to-day?"

Overland had burst into a wilder frenzy of bucking than ever. His hoofs beat through the dust and tore up solid chunks of the ground and tossed them high above his head. Twice the rider swayed out of his saddle. Twice he saved himself by nothing short of a miracle and was back in his place. He was a weakened Ballantine, now, his head reeling on his shoulders, and his eyes turning wildly in his head. But still the incarnate fiend in him lived and stirred and made him yell a challenge at maddened Overland.

Two cow-punchers, passing toward the bunk house, saw, and with their shouting drew the cook from the house as well as the rest of the house servants. Other men came up. There was a well-ringed group of spectators, now, to watch that historic battle in which Overland fought for his self-respect, and Ballantine fought to make him a slave.

And, when it ended, it was a white-faced rider who sat in the saddle, with two thin streams of blood trickling down from his nostrils, and his eyes staring huge from his head. He shouted hoarsely. Overland broke into a stumbling trot, head down. He jerked on the reins, and the big stallion came to a halt on reeling legs. He was beaten, exhausted, helpless. A child could have ridden him then.

There was not a murmur of applause from those onlookers, much as they worshiped good horsemanship, every one of them. It reminded Ballantine of the silence which had greeted the flooring of big Jeff Partridge and the humiliation of Harry Reddick. He looked calmly about him, wiping the blood from his face with his handkerchief. All those men were staring intently, not at the horse which had just been beaten, but at him, not with admiration, either, but with a sort of frightened awe. And yonder was Peggy, still shrinking at the side of her father. Even that wise man, Holbrook himself, was frowning in a bewildered fashion.

"Why did you do it, Ballantine?" he asked in wonder. "He was like a lamb for you. Maybe you've broken his heart, now!"

Ballantine scowled down at him. "D'you want me to treat a hoss like an equal?" he asked. "I'll have a hoss that walks when I say walk! And trots when I say trot. I'll have a hoss that lets me do his thinkin' for him. That's gunna be my way with hosses—maybe that's gunna be my way with men! If a gent can't get on with peace, lemme see how he can get on with war! One of you over there, open that gate!"

No one stirred.

"You with the red hair and the fool look," snarled out Ballantine. "Open that gate, will you?"

There was not an instant of hesitation. The man jumped as though a leveled revolver covered him. He opened the gate, and through it rode Ballantine. Then there appeared before him Peggy Holbrook, her face flushed, her eyes shining with indignation. She held out to him that sheaf of bills which he had recently handed to her father. "We won't sell him!" she exclaimed. "We won't sell him. Dad thought he was going to a man who loved him—not to a—a tyrant—like you, Chris Ballantine!"

She stamped her foot. "Get out of that saddle and let Overland go back!"

He grinned broadly down at her. For his stunned brain had recuperated already, and the ache was gone from the back of his head, and once more he could see clearly, see and think. And what he knew was the delirious truth that he had fought and won again. Oh, power of mighty hand and arm, how he could have looked up and thanked God for those gifts. But power of mind and soul, also, how far greater! To be able to crush a strong man with a word, with a look. So, feeling all his strength upon him, he looked down to the girl and smiled.

"You got a lot of men here," he said. "Lemme see 'em do the thing that you want done. Lemme see 'em take me out of this here saddle, honey!"

"Chris Ballantine!"

"Women can talk," said the rider slowly. "And that's the end of 'em. Lemme see the gents act. Which one of you starts? Which one of you begins the party?"

He swept their faces with a calm delight. But not a man stirred. That hungry eye ate the power out of their souls.